Abstract

Approximately 2 μmol of a novel prokaryotic pheromone, involved in starvation-induced aggregation and formation of fruiting bodies by the myxobacterium Stigmatella aurantiaca, were isolated by a large-scale elution procedure. The pheromone was purified by HPLC, and high-resolution MS, IR, 1H-NMR, and 13C-NMR were used to identify the active substance as the hydroxy ketone 2,5,8-trimethyl-8-hydroxy-nonan-4-one, which has been named stigmolone. The analysis was complicated by a solvent-dependent equilibrium between stigmolone and the cyclic enol-ether 3,4-dihydro-2,2,5-trimethyl-6-(2-methylpropyl)-2H-pyran formed by intramolecular nucleophilic attack of the 8-OH group at the ketone C4 followed by loss of H2O. Both compounds were synthesized chemically, and their structures were confirmed by NMR analysis. Natural and synthetic stigmolone have the same biological activity at ca. 1 nM concentration.

Keywords: myxobacteria/Stigmatella aurantiaca/microbial development/NMR

Pheromones are defined as substances that are used for communication between individuals of the same species (1). The structure elucidation of acrasin (2) and bombykol (3) are well-known landmarks in early pheromone research. Since then the exchange of chemical signals between individuals of a given species has been observed for many unicellular and multicellular organisms, e.g., for bacteria (4, 5), plants (6–8), and animals (9). It seems that only the archaebacteria have not yet been examined in this respect. It should be noted that some pheromones, such as (Z)-7-dodecen-1-yl acetate, are used by more than one species (9, 10). Because of their potential in pest control, the pheromones of insects have been studied most extensively and represent the largest known class. For bacteria, pheromones of the lactone type (4, 11) make up an important group, and further classes involve specific (modified) peptides (4).

Myxobacteria are on the borderline between unicellular and multicellular organisms. They live as single cells associated in swarms during the vegetative part of their life cycle to manage cooperative feeding (12, 13). In the developmental part of the life cycle the cells of a swarm form multicellular fruiting bodies containing the myxospores. Such a prokaryotic system can serve as a simple model for cell differentiation and cell positioning in multicellular organisms or tissues under the influence of pheromone-like or hormone-like chemical signals.

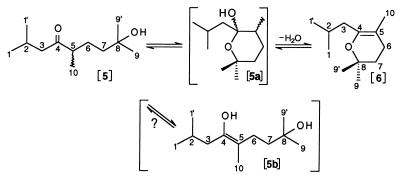

A pheromone activity of Stigmatella aurantiaca was previously described by Stephens et al. (14) as to be involved in the formation of fruiting bodies. In a companion paper (15) we have confirmed that diffusable signaling factor(s) are required for the aggregation of the myxobacterium S. aurantiaca and subsequent formation of fruiting bodies under conditions of starvation. Aggregation was abolished when factors of low molecular weight were removed from the cells by dialysis. This finding was interpreted as proof that a pheromone is required for aggregation. Here we describe the structure elucidation of the isolated Stigmatella pheromone, named stigmolone, which was found by NMR spectroscopy to be 2,5,8-trimethyl-8-hydroxy-nonan-4-one [5]. The investigation was complicated by the fact that, depending on the isolation and purification procedures used, the ketone underwent intramolecular cyclization with loss of H2O to form the six-membered heterocycle containing an enol-ether moiety, formally named 3,4-dihydro-2,2,5-trimethyl-6-(2-methylpropyl)-2H-pyran [6]. Both the ketone and dihydropyran compounds were synthesized chemically, and pheromone activity at concentrations of ca. 1 nM was unambiguously assigned to the ketone structure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culturing of S. aurantiaca DW4/3–1 (16) and the biological assay for the activity of the pheromone were carried out as described in ref. 15.

Preparation of Natural Pheromone for NMR Analysis.

The natural pheromone was collected by an elution procedure and purified as previously described (15). Briefly, for the 2-μmol NMR sample the volatile pheromone was isolated by steam distillation of many batches of eluate collected over 5-day periods from a total of 8 × 1013 starving cells, followed by fractionation on a reversed-phase C18 column (three runs). After transfer of the active material into cyclopentane (using two 100-mg solid-phase extraction columns) the active material was subjected to normal-phase HPLC (two runs). The active fraction was evaporated to dryness under a stream of dry nitrogen at room temperature and the solvent condensed at −78°C. The residue was dissolved in 0.5 ml of CD2Cl2, and the CD2Cl2 evaporated (see above); pheromone activity in the condensate was <1% of that for the whole active material.

Analytical Procedures.

The isolated natural pheromone was analyzed by (i) high-resolution MS in electron impact (EI) mode with a JMS-700 instrument (JEOL); (ii) electrospray ionization (ESI) MS with a TSQ 7000 (Finnigan-MAT, San Jose, CA); and (iii) GC-IR using a Digilab FTS-40 Fourier transform (FT) instrument equipped with a Digilab Tracer cryotrapping GC interface (Bio-Rad).

Synthetic compounds were analyzed as follows: (i) analytical TLC on precoated plates of silica gel 60 with a fluorescence indicator (Macherey & Nagel), spot detection by exposure to iodine vapor; (ii) FT-IR with an IFS 66 spectrometer (Bruker Analytik, Rheinstetten, Germany); and (iii) routine 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra at 24°C in CDCl3 at 300 and 75.5 MHz, respectively, using a Bruker AM-300 spectrometer [chemical shifts δ in ppm relative to internal tetramethylsilane, proton-proton coupling constants (J) in Hz].

Structure Elucidation by NMR.

Samples of the natural pheromone and the synthetic 5 and 6 were investigated in detail by 1H- and 13C-NMR spectroscopy at 500.13 and 125.76 MHz, respectively, on an AM-500 NMR spectrometer (Bruker Analytik) using 5-mm sample tubes (Wilmad, Buena, NJ). A variety of conventional one-dimensional and two-dimensional (2D) FT NMR experiments (17) were performed at 10°C and 30°C using the solvents CD2Cl2 (99.9% D, Euriso-top, Saint Aubin, France), D2O (99.96% D, MSD Isotopes, Munich, Germany), and cyclohexane-d12 (99.8% D, Chemotrade, Leipzig, Germany).

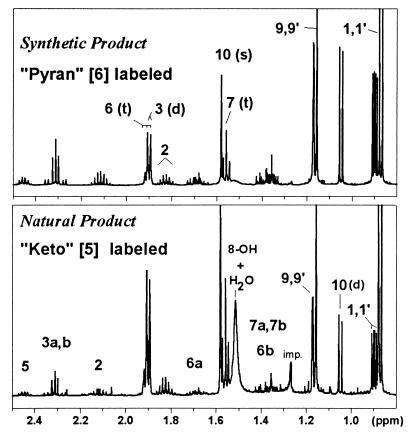

For Fig. 3 the 1H-NMR spectrum of a sample containing ca. 2 μmol purified pheromone in 0.4 ml CD2Cl2 was obtained at 30°C with 4,096 transients in 6.6 h (spectral width 3,424 Hz, time domain size 32K, repetition time 5.78 s, flip angle 77°). Detailed analysis of chemical shifts and coupling constants (Table 1) was performed with zero-filling to 64K data and resolution enhancement using Bruker’s win-nmr software. For comparison, a sample of synthetic ketone 5 (ca. 10 mg) was prepared and measured in a similar way (128 transients in 17 min, repetition time 7.78 s, flip angle 29°). A conventional magnitude-mode correlated spectroscopy (COSY) 2D H-H correlation experiment was performed with the natural pheromone sample: spectral width 1,033 Hz; F2 time domain: 2K points in 0.991 s; F1 domain: 512 increments, 32 transients per free induction decay, 60° read pulse, average repetition time 3.24 s, total time 17 h; 2D-FT with sine-bell window functions and zero-filling in F1 to give a 1K × 1K matrix with 1.01 Hz/point (pt) digital resolution. Long-range couplings for I were confirmed by COSY and homodecoupling.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the 500-MHz 1H-NMR spectra of the natural pheromone stigmolone (Lower, ca. 2 μmol in 0.4 ml CD2Cl2 at 30°C) and the synthetic ketone 5 (Upper, 50 μmol in 0.4 ml CD2Cl2 at 30°C). Both spectra show a mixture of species: I/II (6/5) ratio = 4.0 (natural product) or 1.15 (synthetic), as a result of a partial conversion of the ketone 5 (spin system II labeled in the lower spectrum) to the dihydropyran 6 (spin system I labeled in the upper spectrum) during purification (see Fig. 2).

Table 1.

1H-NMR data for the natural pheromone preparation (compounds I and II) and for synthetic 5 and 6 (see Fig. 3)

| Group | Position | δH, ppm

|

δH, ppm

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in CD2Cl2 | in D2O | in CD2Cl2 | in c-Hex. |

J couplings, Hze

|

||||||

| Nat. IIa | [5]b | [5]c | Nat. Ia | [6](mix.)b | [6]d | Nat. II | Nat. I | |||

| CH3 | 1 | 0.9025 | 0.9024 | 0.9184 | 0.8718 | 0.8716 | 0.8676 | 3J(1,2) | 6.58 | 6.52 |

| 1′ | 0.8949 | 0.8947 | 0.9135 | 6.69 | ||||||

| CH | 2 | 2.1125 | 2.1132 | 2.094 | 1.8225 | 1.8225 | 1.869f | 3J(2,3) | 7.13(3a); 6.63(3b) | 7.06 |

| CH2 | 3a | 2.3345 | 2.3352 | 2.52 | 1.9012 | 1.9000 | 1.901f | 1J(3a,b) | −16.54 | |

| 3b | 2.2888 | 2.2889 | 2.50 | 5J(3,6) | 1.11 | |||||

| 5J(3,10) | 0.48 | |||||||||

| CH | 5 | 2.4523 | 2.4531 | 2.704 | 3J(5,6) | 7.08; 5.72 | ||||

| CH2 | 6a | 1.67g | 1.67h | 1.67i | 1.9060 | 1.9052 | 1.882f | 3J(6,7) | n.d.g | 6.74 |

| 6b | 1.36g | 1.36h | 1.44i | 4J(6,10) | 0.98 | |||||

| CH2 | 7a | 1.38g | 1.38h | 1.48i | 1.5582 | 1.5577 | 1.5237 | 3J(6,7) | n.d.g | |

| 7b | 1.33g | 1.33h | 1.40i | |||||||

| −OH | 8 | 1.51j | 2.9; 4.15k | |||||||

| CH3 | 9 | 1.1735 | 1.1736 | 1.209 | 1.1590 | 1.1563 | 1.1325 | 4J(9,9′) | 0.21 | |

| 9′ | 1.1710 | 1.1700 | ||||||||

| CH3 | 10 | 1.0486 | 1.0488 | 1.0856 | 1.5807 | 1.5802 | 1.5647 | 3J(5,10) | 7.00 | |

| rms dev.l | 0.00046 | 0.114 | 0.0012 | 0.026 | ||||||

Natural pheromone preparation (mixture of I and II), shifts relative to CHDCl2 = 5.32 ppm (30°C).

Mixture of 5 and 6 derived from synthetic 5 (30°C).

Nearly pure 5 in D2O, HDO = 4.75 ppm (30°C).

Pure 6 in cyclohexane-d12 at 15°C (solvent = 1.38 ppm).

4J(1,3) for I and II, 4J(7,9) for I detected by COSY.

Determined from the coloc 2D CH correlation experiment.

Complex second-order spin systems; δH from COSY spectrum; n.d., not determined.

Multiplets superimposable with those of II.

Estimated shifts assigned by analogy to II.

Residual water.

For pure synthetic 5 as neat liquid.

rms deviation of all shifts (except 8-OH) relative to natural compound.

The above sample of natural pheromone was reduced in volume to ca. 0.3 ml and used to obtain a 1H-decoupled 13C-NMR spectrum at 10°C with 84,000 transients in 70 h: spectral width 29,411 Hz, time domain 64K zero-filled to 128K, power-gated WALTZ-16 1H decoupling, repetition time 3.014 s, flip angle 30°, exponential line-broadening of 1.4 Hz. These conditions were chosen to facilitate integration of the spectrum for assignment of Cq and CHn signals for compounds I and II shown in Table 2 (I/II ratio ca. 2.9). The signal-to-noise ratios ranged from ca. 2 for the ketone carbon of II to ca. 17 for CH3 carbons of I (dihydropyran). Multiplicity analysis (CH, CH2, CH3) was performed by using distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer (DEPT-90) (6 h) and DEPT-135 (23 h) experiments. Finally, a polarization-transfer CH correlation with 13C detection and bilinear rotation decoupling in the F1 domain was performed: 13C domain, 5319 Hz, 4K points; 1H domain, 1,033 Hz, 256 increments, zero-filled to 512; polarization transfer delays, 3.7 and 1.9 ms; repetition time 2.25 s, 128 transients per free induction decay, total time 21 h; magnitude-mode 2D-FT with cosine-bell window functions to give a 2K × 512 matrix with 2.6 Hz/pt in 13C and 2.02 Hz/pt in 1H.

Table 2.

13C-NMR data for the natural pheromone preparation and the synthetic compounds 5 and 6

| Position | δc, ppma

|

Predictionsb

|

δc, ppma

|

Predictionsb

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in CD2Cl2, 10°C | ketone [5] | in CD2Cl2 | in c-Hex. | Dihydropyran [6] | enol [5b] | ||||||

| Nat. II | [5](mix). | S. Tool | S. Edit | Nat. I | [6](mix.) | [6] | S. Tool | S. Edit | S. Tool | S. Edit | |

| 1 | 22.643 | 22.796 | 21.8 | 22.0 (4) | 22.382 | 22.554 | 22.880 | 22.7 | 23.0 (3) | 22.7 | 23.0 (3) |

| 1′ | 22.571 | 22.720 | |||||||||

| 2 | 24.350 | 24.426 | 22.4 | 25.0 (3) | 27.099 | 27.155 | 27.478 | 22.9 | 27.0 (2) | 22.6 | 27.0 (2) |

| 3 | 50.377 | 50.511 | 47.7 | 43.0 (2) | 39.655 | 39.775 | 40.299 | 41.6 | 26.0 (2) | 43.5 | 26.0 (2) |

| 4 | 214.404 | 214.795 | 211.3 | 213.0 (2) | 145.456 | 145.585 | 146.526 | 149.8 | 149.0 (2) | 149.4 | 162 (1) |

| 5 | 46.902 | 47.069 | 47.4 | 44.0 (2) | 100.677 | 100.599 | 99.719 | 100.8 | 137 (1) | 105.9 | 137 (1) |

| 6 | 27.531 | 27.682 | 21.8 | 27.0 (2) | 25.280 | 25.394 | 25.942 | 27.2 | 31.0 (2) | 21.0 | 31.0 (2) |

| 7 | 41.380 | 41.473 | 43.0 | 34.0 (2) | 33.612 | 33.733 | 34.320 | 43.5 | 34.0 (2) | 43.8 | 34.0 (2) |

| 8 | 70.677 | 70.544 | 68.7 | 71.0 (3) | 72.118 | 72.157 | 72.041 | 69.4 | 76.0 (2) | 69.1 | 71.0 (3) |

| 9 | 29.261 | 29.413 | 30.1 | 29.0 (4) | 26.501 | 26.651 | 26.970 | 28.0 | 28.0 (3) | 30.2 | 29.0 (4) |

| 9′ | 29.210 | 29.227 | |||||||||

| 10 | 16.480 | 16.657 | 13.7 | 15.0 (3) | 17.945 | 18.086 | 18.244 | 12.9 | 20.0 (2) | 12.9 | 20.0 (2) |

| rms dev.c | 0.172 | 2.43 | 3.20 | 0.118 | 0.642 | 4.21 | 4.98 | ||||

Comparing the natural isolated mixture I + II (ca. 5 mM) with a synthetic mixture derived from 5 (ca. 1 M) in CD2Cl2 at 10°C (CD2Cl2 = 53.80 ppm), and with pure 6 (ca. 1 M) in cyclohexane-d12 at 15°C (solvent = 26.40 ppm); assignments for natural material obtained by CH correlation, including discrimination of 1,1′ and 9,9′ for the ketone.

Shift predictions made with spectool and with win-specedit based on (n) spheres of HOSE code; bold highlights data where spectool predictions favor dihydropyran 6.

rms deviation of all shifts relative to those for the natural material.

A sample of the synthetic ketone 5 was prepared at ca. 1 M concentration in CD2Cl2 and exhibited a mixture of the ketone and dihydropyran forms in a ratio of ca. 2.5:1. A conventional 1H-decoupled 13C spectrum (1,000 transients in 100 min) gave the results summarized in Table 2.

1H- and 13C-NMR data also were obtained from a nearly pure sample of synthetic dihydropyran 6 at 15°C in cyclohexane-d12 (ca. 1 M, Tables 1 and 2). A 2D incredible natural abundance double quantum (DQ) transfer experiment (INADEQUATE) was performed to establish long-range C-C connectivities (F2 domain: 17,857 Hz, 16K data points; F1 (DQ evolution) domain: ±14,706 Hz, 256 increments, 128 transients per free induction decay; spin-echo delay for DQ preparation 125 ms (optimal for JCC = 4.0 Hz), relaxation delay 4.5 s, 125° read-out pulse, total time 48 h; power-mode 2D-FT with cosine-bell window functions and zero-filling to give a 512 × 16K matrix with 1.1 Hz/pt in F2, 59.2 Hz/pt in F1). The expected one-bond C-C correlations were detected as pairs of doublets at the corresponding DQ frequencies in F1. Pairs of correlation signals for 21 long-range correlations over 2–4 bonds (nJCC < 4 Hz) also were detected at the correct DQ frequencies, but only in five cases could the coupling be resolved as a signal splitting.

Finally, two long-range CH correlation experiments, correlation spectroscopy for long-range couplings (COLOC), were performed for 6 with the following parameters: F2 domain, 17,857 Hz, 8K points; F1 domain, 680 Hz, 128 increments, (a) 64 or (b) 96 transients per free induction decay; polarization/rephasing delays of (a) 125/62.5 ms (optimal for JCH = 4.0 Hz) or (b) 300/150 ms (optimal for JCH = 1.7 Hz), repetition time (a) 4.92 or (b) 5.18 s, total time (a) 12 h or (b) 18 h; magnitude-mode 2D-FT with sine-bell window functions (shifted π/6) to give a 256 × 4K matrix and 4.26 Hz/pt in F2, 2.66 Hz/pt in F1.

1H and 13C chemical shift predictions for 5, 5b, and 6 were made using: (i) the spectool software (version 2.1, Chemical Concepts, Weinheim, Germany) based on empirical shift increment rules; (ii) the win-specedit software (version 961001, Bruker-Franzen, Bremen, Germany) based on data libraries for 1,000 (1H) or 10,000 (13C) compounds and using hierarchically ordered spherical description of environment (HOSE) codes to define atomic environments in spheres.

Molecular modeling of 5, 5b, and 6 was performed by using the MM2+SCF force field of chem3d (version 3.2, CambridgeSoft, Cambridge MA).

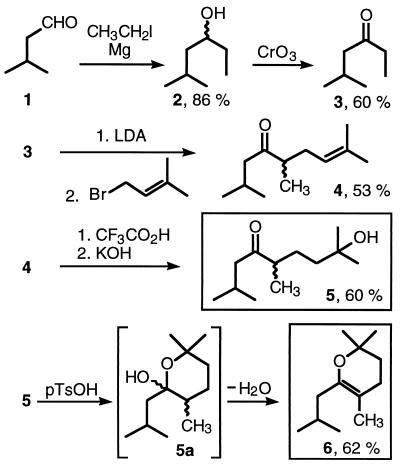

Syntheses.

5-Methyl-hexan-3-ol [2]. A standard Grignard reaction was performed by using magnesium turnings (12.2 g, 0.5 mol) and ethyl iodide (78.4 g, 0.5 mol) in diethyl ether (130 ml). After addition of isovaleric aldehyde 1 [34.6 g, 0.4 mol in diethylether (43 ml)], the reaction mixture was refluxed for 2 h and allowed to cool. Ice (50 g) was added, and the mixture was acidified using 6 M HCl until a clear, homogeneous solution was obtained. The organic layer was separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted twice with 50 ml of diethyl ether. The combined organic layers were washed once with a saturated Na2S2O5 solution, twice with a saturated NaHCO3 solution, and finally dried with MgSO4. Evaporation of the solvent afforded a residue, which was purified by distillation under reduced pressure (54°C/2.1 kPa) to yield 2 as a colorless liquid (40 g, 86%).

IR(film): ṽ (cm−1) = 3,345 (s, broad), 2,958 (vs.), 2,926 (vs.), 2,871 (s), 1,467, 966.

1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ = 0.78–0.90 (m; 9 H, CH3), 1.09–1.49, 1.62–1.78 [m; 5 H, CH2, (CH3)2CH], 2.01 (s; 1H, OH), 3.50 (mc; 1 H, CHOH).

13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ = 9.8, 22.1, 23.5 (all q, CH3), 24.7 [d, (CH3)2CH)], 30.8, 46.3 (both t, CH2), 71.3 (d, CHOH).

5-Methyl-hexan-3-one [3].

To a solution of the alcohol 2 (11.6 g, 0.1 mol) in diethyl ether (50 ml), a solution of Na2Cr2O7⋅2H2O (9.98 g) and H2SO4 (7.5 ml) in water (50 ml) was added at 25°C. After 2 h stirring at room temperature, the organic layer was separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted twice with 25 ml of diethyl ether. The combined organic layers were washed with a saturated NaHCO3 solution (50 ml), then with water (50 ml), and dried (MgSO4). The solvent was evaporated and the residue was purified by distillation under reduced pressure (48°C/4.0 kPa) to give the ketone 3 as a colorless liquid (6.8 g, 60%).

IR(film): ṽ (cm−1) = 2,959 (vs.), 2,874 (s), 1,714 (vs.), 1,464 (s), 1,412, 1,368 (s), 1,105.

1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ = 0.90 (d, J = 6.6 Hz; 6 H, CH3), 1.03 (t, J = 7.3 Hz; 3 H, CH3), 2.13 (mc; 1 H, CH), 2.27 (d, J = 6.9 Hz; 2 H, CH2CH), 2.39 (q; J = 7.3 Hz; 2 H, CH2CH3).

13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ = 7.8, 22.6 (both q, CH3), 24.7 [d, (CH3)2 CH], 36.4, 51.5 (both t, CH2), 211.5 (s, CO).

2,5,8-Trimethyl-7-nonen-4-one [4].

A solution of diisopropylamine (1.95 g, 19.3 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (20 ml) was stirred under nitrogen at −5°C. A solution of butyllithium (13.15 ml, 1.6 M in hexane, 21 mmol) was added. A solution of the ketone 3 (2 g, 17.5 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (10 ml) was added dropwise at −70°C under nitrogen, and stirring was continued for 15 min. Then a solution of 3,3-dimethylallyl bromide (2.6 g, 17.5 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (5 ml) was added at −70°C, and the mixture was stirred for 40 min under nitrogen without further cooling. The resulting mixture was added to ice/water (50 ml) and acidified by addition of 2 M HCl. The organic layer was separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with 3 × 50 ml CH2Cl2. The combined organic layers were washed with a saturated NaHCO3 solution and dried (MgSO4). The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to afford the crude product, which was purified by flash chromatography in CH2Cl2 on silica gel 60 (230–400 mesh; Macherey & Nagel). The ketone 4 was obtained as a colorless oil (1.7 g, 53%).

TLC analysis: Rf value, CH2Cl2, 0.63.

1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ = 0.88 [d, J = 6.6 Hz; 6 H, (CH3)2CH], 1.02 (d, J = 6.9 Hz; 3 H, CH3CH), 1.39, 1.66 (br. s; 3 H each, allylic CH3), 1.95–2.60 (m; 6 H, CH, CH2), 5.02 (mc; 1 H, vinyl-H).

13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ = 15.9 (q, CH3), 17.7 (q, CH3), 22.58, 22.60 (q, CH3; d, CH), 24.2, 25.7 (q, CH3), 31.4 (t, CH2), 46.8 (d, CH), 50.5 (t, CH2), 121.6 (d, vinyl-CH), 133.4 (s, vinyl-C), 214.2 (s, CO).

2,5,8-Trimethyl-8-hydroxy-nonan-4-one [5].

Trifluoroacetic acid (95% vol/vol; 3.4 ml) was added to the olefin 4 (500 mg, 2.7 mmol) at 0°C. After stirring for 40 min at room temperature, 5 M KOH (17.5 ml) was added at 0°C. After stirring for 15 h at room temperature the resulting mixture was extracted with 3 × 15 ml CH2Cl2. The combined organic layers were washed twice with 20 ml of water, dried (Na2SO4), and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography [hexane/ethyl acetate 6:4 (vol/vol)]. The ketone 5 was obtained as a colorless oil (330 mg, 60%) and contained <2% of the dihydropyran 6 as assessed by NMR.

TLC analysis: Rf values, CH2Cl2, 0.06; hexane/ethyl acetate 6:4 (vol/vol), 0.32.

NMR data for 5 are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

In a pilot experiment, the following HPLC procedure was used instead of flash chromatography. Crude material (80 mg) was suspended in 0.3 ml of 70% methanol/water, filtered through a 100-mg Bakerbond spe* C18 solid-phase extraction column, and diluted to 60% methanol/water. Portions of 15-μl (corresponding to ca. 1.9 mg of crude material) were loaded onto a reversed-phase column (Ultropac TSK ODS-120T, 5 μm, 25 × 4.6 mm; LKB) and eluted with 60% methanol/water at 1 ml/min (retention time for 5 was 14–17 min). The material from several runs was extracted with 5 × 20 ml of cyclopentane, pooled, dried (Na2SO4), and evaporated to give 5. This procedure resulted in a lower yield and partial conversion of 5 to 6 (53%).

3,4-Dihydro-2,2,5-trimethyl-6-(2-methylpropyl)-2H-pyran [6].

To a stirred solution of the ketone 5 (250 mg, 1.25 mmol) in cyclohexane (2 ml), p-toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate (ca. 5 mg) and MgSO4 (220 mg) were added at room temperature. Stirring was continued for 45 min, and the resulting mixture was purified by flash chromatography [hexane/ethyl acetate 6:4 (vol/vol)] to give the dihydropyran 6 as a colorless oil (140 mg, 62%).

TLC analysis: Rf values, CH2Cl2, 0.62; hexane/ethyl acetate 6:4 (vol/vol), 0.74.

ESI-MS, in acetonitrile (positive-ion mode): m/z = 182.8 [M + H]+; high-resolution EI-MS, in cyclohexane-d12: m/z = 182.1678 [M+] corresponds to C12H22O with a measured minus exact mass difference of Δm = 0.73 mDa.

NMR data are presented in Tables 1–3.

Table 3.

C-C connectivities in the dihydropyran 6

| Sequential | 1Jcc, Hz | Long-range | Bonds (n) | nJcc, Hz |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, 2 | 35.2 | 3, 5 | 2 | 3.5 |

| 2, 3 | 33.8 | 3, 6 | 3 | <3 |

| 3, 4 | 53.0 | 3, 8 | 3 | <2 |

| 4, 5 | 83.8 | 4, 6 | 2 | <3 |

| 5, 6 | 40.9 | 4, 7 | 3 | 2.5 |

| 6, 7 | 32.9 | 4, 8 | 2 | <2 |

| 7, 8 | 35.8 | 4, 9 | 3 | <2 |

| 8, 9 | 40.4 | 4, 10 | 2 | 3 |

| 5, 10 | 48* | 5, 8 | 3 | 3.7 |

Couplings determined from DQ-2D correlation matrix; digital resolution 1.1 Hz/pt; bold marks long-range connectivities that can only occur in a cyclic structure.

Echo time 15 ms, digital resolution 4.4 Hz/pt.

RESULTS

Structure Elucidation of the Natural Pheromone.

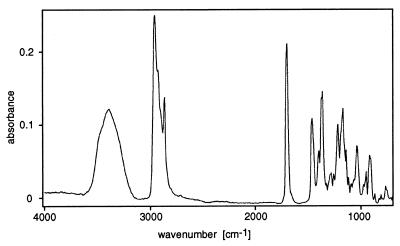

The purification procedure described in detail elsewhere (15) yielded an active pheromone preparation that gave a single peak upon GC analysis. The mass spectrum (EI) of this GC peak was identical with the mass spectrum obtained from the original preparation (before GC separation, data not shown), suggesting that the preparation was homogenous. The positive-ion ESI-MS spectrum of the purified pheromone in pentane/methyl acetate/isopropanol (4:1:5) showed a single predominant peak at m/z = 223.1, assigned to [M + Na]+ and confirmed by collision-induced dissociation with release of a daughter ion with m/z = 23.0 [Na+]. Thus, the nominal molecular mass was determined to be 200 Da. High-resolution mass analysis of the two largest fragments observed in the conventional EI-MS spectrum gave masses of 185.1558 ([M − CH3]+ = C11H21O2, Δm = 1.6 mDa) and 182.1647 ([M − H2O]+ = C12H22O, Δm = −2.4 mDa). The FT GC-IR spectrum (Fig. 1) exhibited a carbonyl band at 1,703 cm−1 and a hydroxyl group absorption at 3,380 cm−1. These data indicated that the pheromone is a hydroxy ketone with the molecular formula C12H24O2 (molecular mass = 200 Da).

Figure 1.

The FT GC-IR spectrum of the cryotrapped pheromone stigmolone isolated from S. aurantiaca.

Initial 1H-NMR studies were performed with a small quantity (ca. 0.2 μmol) of purified pheromone. The one-dimensional 1H-NMR spectrum showed signals only in the narrow range of 0.8–2.6 ppm, indicative of aliphatic CH protons without geminal oxygen neighbors. Integration of the spectrum revealed that, unexpectedly, two substances were present in a ratio of 3:1. The major component, called compound I, was found by COSY 2D NMR to be composed of the following two fragments or spin systems: -C-CH2-CH(CH3)2 with three unfilled valences and CH3-C-CH2-CH2-C-(CH3)2 with three unfilled valences. The sum of these fragments is C12H22, indicating that two -OH groups were not accounted for, but resonances for hydroxyl protons were not detected because of the relatively large amount of residual water present (δ = 1.505 ppm). All chemically equivalent protons were also magnetically equivalent, suggesting that compound I was an open-chain molecule. Thus, the enol 5b (Fig. 2) was our first hypothesis for I.

Figure 2.

Possible equilibria involving the ketone 5 (stigmolone), the hemiacetal 5a, the enol 5b, and the dihydropyran 6. The numbering scheme used for NMR assignments is shown, and wavy bonds indicate indeterminate stereochemistry (mixture of enantiomers).

The minor compound II exhibited a total of 23 nonexchangeable protons and several of the structural features found for I. However, the spin systems were complex with nonequivalence of methylene protons and isopropyl methyls. Because of the small sample quantity, the COSY data for II were inconclusive, and no detectable 13C-NMR spectrum could be obtained in a 24-h acquisition. After 3 months of storage at 4°C the ratio I/II had changed from initially 3.0 to 0.88, clearly indicating the interconvertability of the two forms.

Considerable effort was then made to obtain sufficient material from 8 × 1013 cells for 13C-NMR. The resulting NMR sample contained about 2 μmol with which it was possible to perform detailed 1H-NMR, COSY 2D, 13C-NMR, 13C-DEPT, and CH 2D correlation experiments (see Materials and Methods, Fig. 3 Lower, Tables 1 and 2). The analysis showed initially a 4:1 ratio for I/II and confirmed that I must be either the enol 5b or possibly the cyclic dihydropyran 6. Compound II was unequivocally identified as the open-chain ketone 5 with tertiary hydroxyl function. The magnetic nonequivalence observed at all methylene and methyl sites for this molecule is caused by the presence of the ketone function (diamagnetic susceptibility effects) at C4 next to the asymmetric center C5.

The assignment of compound I to the enol 5b or the dihydropyran 6 could not be made with certainty because both substances feature the same basic spin systems for nonexchangeable 1H and 13C. The simplicity of the spectrum favored the open-chain form 5b, but chemically 6 made more sense, e.g., if the purification and drying procedures using organic solvents drives the equilibrium from 5 toward 6 (Fig. 2). 13C chemical shift predictions provided evidence favoring the dihydropyran 6, especially for C3, C5, C6, and C9 (Table 2), whereas 1H predictions were equivocal. Molecular modeling showed that the dihydropyran ring can adopt two conformations of equal energy with either the 9 or the 9′ methyl in a pseudo-axial position. Rapid interconversion of these conformers and the axial and equatorial positions at C6, C7, C8 would be necessary to create a pseudo plane of symmetry, resulting in the simple spectrum observed for compound I.

To clarify the structure of I and to determine unambiguously whether I or II is in fact the pheromone, authentic compounds 5 and 6 were prepared via organic synthesis.

Synthesis and NMR Analysis of 2,5,8-Trimethyl-8-hydroxy-nonan-4-one [5].

The ketone 5 was synthesized via the procedure outlined in Fig. 4 (see Materials and Methods). The Grignard addition of ethyl magnesium iodide to isovaleric aldehyde 1 gave the racemic alcohol 2, which then was oxidized to the ketone 3. Enolate formation under kinetic control at −70°C and subsequent reaction with 3,3-dimethylallyl bromide gave the desired olefin 4, with almost perfect regioselectivity of the alkylation. For the Markovnikov hydration of the olefin, 4 was treated with trifluoroacetic acid (yielding initially the corresponding trifluoroacetate), followed by alkaline hydrolysis to the tertiary alcohol 5.

Figure 4.

Chemical synthesis of the Stigmatella pheromone stigmolone 5 and the dihydropyran 6.

A 10-mg sample of synthetic 5, purified by RP-HPLC (pilot experiment, see Materials and Methods) and dissolved in 0.4 ml of CD2Cl2, gave the 1H-NMR spectrum shown in Fig. 3 (Upper). Again, compounds I (dihydropyran) and II (ketone) were observed, and their signals were essentially superimposable on those obtained from the natural product (see Tables 1 and 2). The only difference was that the ratio I/II (1.15) differed from that of the natural isolated product. Positive-ion ESI-MS analysis of the NMR sample diluted in chloroform/methanol (1:1) or acetonitrile gave major peaks at m/z = 423.3 [2MI + Na+], 223.1 [MI + Na+], and 183.0 [MII + H+] or [MI − OH]+.

The synthesis strategy chosen should have produced only the ketone 5, but we suspected that the work-up procedure was causing a partial conversion to 6 (Fig. 2). Therefore, a second, larger batch of synthetic 5 was purified by flash chromatography. A sample of the neat liquid gave a 1H-NMR spectrum (not shown), which clearly corresponded to the spectrum of compound II with <2% of 6 present. In addition, a one-proton signal from the 8-OH group was observed at 4.15 ppm. A ca. 130-mg sample of the synthetic material was dissolved in CD2Cl2 to a volume of 0.38 ml. The 1H-NMR spectrum (10°C) showed again the characteristic spectrum of 5 with the 8-OH signal appearing at 2.9 ppm. Initially, 6 was not detectable (<0.5%), but after 3 days reached a level of ca. 2.5%.

An aliquot of this NMR sample (ca. 50 μl) was extracted with 0.5 ml of D2O. The 1H-NMR spectrum of the D2O phase (not shown) corresponded to the ketone 5 (II) with some minor differences in chemical shifts (Table 1). At pH 5 I increased to ca. 7% after 7 days. The pH then was lowered to 1.9 (trifluoroacetic acid); the H5 signal for the ketone 5 decreased to 17% of its nominal intensity after 3.5 h (30°C) and 4% after 6 h (deuterium exchange); the H10 methyl group appeared as a singlet. The dihydropyran 6 was reduced to 1–2%, indicating that the acid-catalyzed equilibrium strongly favored 5 over 6.

Synthesis and NMR Analysis of 3,4-Dihydro-2,2,5-trimethyl-6-(2-methylpropyl)-2H-pyran [6].

To verify dihydropyran 6 as the structure of compound I a large quantity of this material was synthesized unambiguously by cyclization of 5, most likely via 5a, in the presence of catalytic amounts of acid plus a dehydrating agent. The purified dihydropyran 6 was found to be more stable in cyclohexane than in methylene chloride. A concentrated solution of 6 in cyclohexane-d12 (ca. 50 mg in 0.35 ml) gave a 1H-NMR spectrum characteristic for I with only minor differences in chemical shifts (solvent effects, Table 1, rms deviation = 0.026 ppm). The 13C-NMR spectrum of 6 agreed reasonably well with the data for I, despite differences in concentration, solvent, and temperature (Table 2); ketone 5 was not detected (<1%).

INADEQUATE DQ-2D experiments were performed for analyzing C-C connectivities over 1–4 bonds (Table 3) and COLOC 2D experiments examined long-range CH correlations. A total of 21 long-range C-C connectivities were detected with nJCC < 4 Hz. The two-bond connectivity between C4 and C8 and the three-bond connectivities C3,C8 and C4,C9 can occur only in the cyclic dihydropyran structure 6 and not in the alternative enol structure 5b. A total of 26 long-range CH connectivities were detected with COLOC, including the 4JHCCOC between H9 and C4, which is unique for structure 6. Finally, the solution used for NMR was submitted to ESI-MS and high-resolution EI-MS, confirming the molecular formula of C12H22O for 6.

Biological Activity of Compounds 4, 5, and 6.

The pheromone activity of 4, 5, and 6 was tested in our standard bioassay. Both the isolated natural pheromone and 5 were active at concentrations of about 1 nM (15). The enone 4 was inactive over the range 1 nM to 1 μM. The dihydropyran 6 was inactive at 10 nM but showed essentially full activity at 100 nM, most likely because of the presence of a small amount of ketone 5 formed in aqueous solution (Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

Synthetic 5 and 6 have been shown by NMR to be identical to compounds II and I, respectively, which were detected in CD2Cl2 solutions of concentrated, purified natural pheromone. The possibility that I was the enol 5b could be ruled out as follows: (i) no enol-OH signal was detected for I, (ii) the NMR properties of synthetic 6 closely matched those of I, and (iii) the dihydropyran ring for 6 was confirmed conclusively by long-range connectivities.

An unexpected aspect of this work was the discovery that the procedures used to purify the natural pheromone resulted in significant conversion of II (5) to I (6) in organic solvents. In fact, pure synthetic 5 could be prepared only when flash chromatography was used without a final drying step. The equilibrium of Fig. 2 is quite slow in organic solvents or neutral aqueous solution but has a half-life for exchange of H5 of only a few hours at pH 2. The acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of dihydropyran derivatives to the corresponding hydroxy ketones was described earlier (18). The predominance of 5 in dilute aqueous solution can be explained by a shift of the equilibrium from 6 toward 5 caused by the high concentration of water. It is reasonable that the hemiacetal 5a and/or the enol 5b serve as intermediates in this process, and they may be responsible for some of the impurities detected by NMR at a level of 1–3%.

The synthetic ketone 5 and the natural isolated pheromone exhibit the same specific activity in the bioassay, whereas 4 and 6 are inactive. This finding suggests that the ketone and hydroxyl functional groups of 5 may be important for its interactions with a putative receptor (specificity). We have named the hydroxy ketone 5 stigmolone, because of its biological origin and the functional groups present. Stigmolone is a new type of prokaryotic pheromone. Up to now, aliphatic (hydroxy) ketones and alcohols as signal substances have been found only in insects (19).

Note that stigmolone contains one asymmetric center at C5; however, the configuration of the natural material and the possible stereospecificity of a putative receptor are unknown. The synthetic material is racemic, and the extensive isolation and purification procedures for obtaining natural material most likely also lead to racemization via the equilibrium of Fig. 2. Rapid epimerization under mild conditions at an equivalent position in a similar hydroxy ketone, 4,6-dimethyl-7-hydroxy-nonan-3-one, has been studied (20, 21). Thus, it is not surprising that natural and synthetic materials have the same biological activity.

With the chemical synthesis presented here, large amounts of the highly active pheromone stigmolone now can be made available, even in isotopically labeled forms. Therefore, we hope to be able to identify the stigmolone receptor in the near future and are confident that other possible physiological effects of stigmolone can be investigated.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Irmela Stamm for her skillful and untiring assistance in stigmolone isolation. We thank Jürgen Gross for the high-resolution EI-MS data of stigmolone, Wolf-Dieter Lehmann and Gerhard Erben for ESI-MS experiments, Sabine Fiedler for high-resolution EI-MS of 6, Tom Visser for GC-IR measurements, and Dietlinde Krauβ for valuable discussions. W.P. is also especially grateful to Hans Ulrich Schairer for stimulating discussions and continuous support of this work.

ABBREVIATIONS

- EI

electron impact

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- FT

Fourier transform

- 2D

two-dimensional

- COSY

correlated spectroscopy

- DQ

double-quantum

- pt

point

- DEPT

distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer

- INADEQUATE

incredible natural abundance double quantum transfer experiment

- HOSE

hierarchically ordered spherical description of environment

- COLOC

correlation spectroscopy for long-range couplings

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

References

- 1.Karlson P, Lüscher M. Nature (London) 1959;183:55–56. doi: 10.1038/183055a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konijn T M, Van De Meene J G C, Bonner J T, Barkley D S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;58:1152–1154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.3.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butenandt A, Beckmann R, Stamm D. Hoppe-Seyler Z Physiolog Chemie. 1961;324:84–87. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1961.324.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wirth R, Muscholl A, Wanner G. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:96–103. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)81525-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunny G M, Leonard B A B. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:527–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaenicke L. In: Progress in Botany. Behnke H, Esser K, Kubitzki K, Runge M, Ziegler H, editors. Vol. 52. Berlin: Springer; 1991. pp. 138–189. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starr R C, Marner F J, Jaenicke L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:641–645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boland W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:37–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly D R. Chem Biol. 1996;3:595–602. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasmussen L E L, Lee T D, Roelofs W L, Zhang A, Daves G D. Nature (London) 1996;379:684. doi: 10.1038/379684a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swift S, Bainton N J, Winson M K. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:193–198. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90110-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimkets L J. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:473–501. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.4.473-501.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dworkin M. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:70–102. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.1.70-102.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stephens K, Hegeman G D, White D. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:739–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.2.739-747.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plaga W, Stamm I, Schairer H U. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11263–11267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qualls G T, Stephens K, White D. Dev Biol. 1978;66:270–274. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hull W E. In: Two-Dimensional NMR Spectroscopy. 2nd Ed. Croasmun W R, Carlson R M K, editors. New York: VCH; 1994. pp. 67–456. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boeckman R K, Bruza K J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977;48:4187–4190. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mori K. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 1996;60:1925–1932. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan P C-M, Chong J M, Kousha K. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:2703–2714. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mori K, Watanabe H. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:3423–3428. [Google Scholar]