Abstract

A large number of genes encoding restriction-modification (R-M) systems are found in the genome of the human pathogen Helicobacter pylori. R-M genes comprise approximately 10% of the strain-specific genes, but the relevance of having such an abundance of these genes is not clear. The type II methyltransferase (MTase) M.HpyAIV, which recognizes GANTC sites, was present in 60% of the H. pylori strains analyzed, whereof 69% were resistant to restriction enzyme digestion, which indicated the presence of an active MTase. H. pylori strains with an inactive M.HpyAIV phenotype contained deletions in regions of homopolymers within the gene, which resulted in premature translational stops, suggesting that M.HpyAIV may be subjected to phase variation by a slipped-strand mechanism. An M.HpyAIV gene mutant was constructed by insertional mutagenesis, and this mutant showed the same viability and ability to induce interleukin-8 in epithelial cells as the wild type in vitro but had, as expected, lost the ability to protect its self-DNA from digestion by a cognate restriction enzyme. The M.HpyAIV from H. pylori strain 26695 was overexpressed in Escherichia coli, and the protein was purified and was able to bind to DNA and protect GANTC sites from digestion in vitro. A bioinformatic analysis of the number of GANTC sites located in predicted regulatory regions of H. pylori strains 26695 and J99 resulted in a number of candidate genes. katA, a selected candidate gene, was further analyzed by quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR and shown to be significantly down-regulated in the M.HpyAIV gene mutant compared to the wild-type strain. This demonstrates the influence of M.HpyAIV methylation in gene expression.

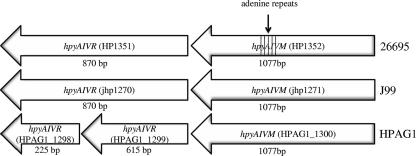

Helicobacter pylori, a gram-negative human pathogen which colonizes the acidic environment of the stomach, is associated with severe gastritis, peptic ulcers, and gastric cancers (28). H. pylori-associated diseases are of major significance, since it is estimated that half of the world's population is infected. However, the majority of individuals colonized by H. pylori are asymptomatic. H. pylori is a genetically diverse species due to its natural competence and high mutation and recombination frequencies (1, 2, 6, 39, 42). The presence or absence of specific genes or differences in gene expression may explain the variability of H. pylori strain virulence (5, 11, 25, 29, 44). Restriction-modification (R-M) systems in bacteria have two complementary functions: DNA modification and restriction. The modification event requires a methyltransferase (MTase) that transfers a methyl group to a specifically recognized DNA sequence and thereby protects this site from digestion by a corresponding restriction endonuclease (REase) (45, 46). Consequently, R-M systems can protect bacteria from the transformation of DNA from other bacteria or transduction from phages (40). Other functions of DNA methylation involve regulation of the replication process (22, 37), DNA mismatch repair (23), movement of transposons (31), involvement in virulence, and gene regulation (16, 21). H. pylori possesses an extraordinary large number of R-M system genes. Some of the R-M systems in H. pylori have complete restriction and modification activities, while others are incomplete, i.e., orphan MTases (18, 19, 43). The R.HpyAIV-M.HpyAIV genes of H. pylori encode two independent enzymes of a type II R-M system, an MTase and a REase that recognize GANTC sites (19). In the sequenced strains 26695, J99, and HPAG1 (2, 27, 42), the MTase is situated upstream of the corresponding REase (Fig. 1). The MTases of the three strains are closely homologous, and protein lengths of the MTase in all three strains are 359 amino acids. J99 and HPAG1 have 97% and 98% identities, respectively, to strain 26695. The protein lengths of the 26695 and J99 REases are 290 amino acids for both strains, and the proteins share an identity of 93%. In the HPAG1 genome, there are truncated variants of two open reading frames (ORFs) homologous to the R.HpyAIV gene, HPAG1_1298 and HPAG1_1299. The ORF adjacent to the M.HpyAIV gene, HPAG1_1299, has a protein sequence of 205 amino acids and is homologous to the 5′ end of the 26695 gene (96% protein identity), and the other R.HpyAIV gene homologue, HPAG1_1298, has a protein sequence of 75 amino acids and is homologous to the 3′ end of the corresponding R.HpyAIV gene in strain 26695 (91% protein identity). The H. pylori MTase M.HpyAIV (HP1352) methylates a nitrogen in adenine, producing N6-methyladenine (N6mA) (43). The presence of the M.HpyAIV gene in clinical H. pylori isolates has been associated with the induction of a more robust host response in gnotobiotic transgenic mice, suggesting that this enzyme could be directly or indirectly involved in gene regulation associated with a more virulent genotype (7). The R.HpyAIV-M.HpyAIV system is homologous to the HinfI R-M system of Haemophilus influenzae. Also, M.HpyAIV has the same GANTC specificity as CcrM (cell cycle-regulated MTase), which is involved in the regulation of the replication process and is essential for viability in Caulobacter crescentus (37).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the genetic organization of the R.HpyAIV-M.HpyAIV genes in strains 26695, J99, and HPAG1. The M.HpyAIV genes are closely homologous in the three strains. The R.HpyAIV gene in HPAG1, HPAG_1299, is truncated, and the adjacent gene, HPAG_1298, is homologous to the 3′ end of the genes in strains 26695 and J99. The lined area shows the nucleotide position where the adenine repeat was found to be variable in active and inactive strains (start at 601 bp).

In this study, we investigated the distribution and activity of the R.HpyAIV-M.HpyAIV system in clinical H. pylori isolates. A functional characterization of M.HpyAIV was performed using a purified recombinant M.HpyAIV protein and an M.HpyAIV gene knockout mutant. Also, the distributions of GANTC sites, which are recognized by the R.HpyAIV-M.HpyAIV system, were identified and mapped in the genome sequences of H. pylori strains 26695 and J99. Seven selected candidate genes containing GANTC sites upstream of ORFs were further investigated using quantitative real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (qPCR) of M.HpyAIV gene mutant and wild-type strains. By using this method, we revealed two genes whose transcription was down-regulated in the mutant strain: katA (HP0875) and HP0835.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Sixty clinical H. pylori isolates obtained from a Swedish gastric cancer case control study that included patients diagnosed with gastric cancer, duodenal ulcer, and nonulcer dyspepsia (12) were analyzed. For studies of intrastrain variation, single-cell colonies of H. pylori obtained from individuals in a random-population-based study at two different occasions within a 4-year interval were used (4, 38). The colonies were isolated from primary cultures of corpus biopsy samples from five individuals with different histological evaluations. All strains were grown on GC agar plates as previously described (6). Liquid cultures of H. pylori were grown in Brucella broth supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 1% IsovitaleX enrichment (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, MD).

DNA and RNA techniques.

DNA was prepared using a DNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Primers HP1352F, HP1352R, 1351RTF, and 1351RTR (Table 1) were used to detect the MTase and REase genes. PCR was performed using DyNAzyme Taq polymerase and the corresponding buffers (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland) and was carried out in 30-μl reaction mixtures using the following cycling conditions: 94°C for 5 min followed by 25 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension period of 5 min at 72°C. To determine the GANTC modification status of the different H. pylori strains, digestion by HinfI, an R.HpyAIV isoenzyme (10 U; New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), was performed overnight using 1 μg of isolated genomic DNA.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in the present study

| Primer | Sequence, starting from 5′ (reference) | Application |

|---|---|---|

| HP1352F | GCG TTT TGA AGG CAC AAA AT | Detection and RT-PCR |

| HP1352R | TGG CAG ATA TAA CGC AAT TCA | Detection and RT-PCR |

| HP1352SF1A | TTT GAT GCA TTT GAT GAG AAC A | Sequencing |

| HP1352SF1B | CGC TTG TGT TAA AAT GGC TAG A | Sequencing |

| HP1352SF2 | AAA AGA CGC GCA AGG TAA AA | Sequencing |

| HP1352SR2 | TTT TAC CTT GCG CGT CTT TT | Sequencing |

| HP1352SrepSF | CCC TAT TTG CAT GGG TAA CG | Sequencing |

| HP1352SrepR | ATT TAG CCA CAG CCC CTG GTT | Sequencing |

| HpyIAVF3 | TTC ACC ACC ATG CAA ACT CAC | Sequencing |

| HpyIAVR3 | TGC CTA ATC TCG CTC TCA TTT G | Sequencing |

| 1352EMSF | TGC GTG ATT TTT CGT TTT TG | Gel shift |

| 1352EMSF | GCG TGT AAG ATT GGT TGA GGA | Gel shift |

| 1351GANTCF | TCG TTT TGT CTT TGG AAC ATC T | Protection and RT-PCR |

| 1351GANTCR | TTG TCG TTT AAA ATG CTC TGC | Protection and RT-PCR |

| 1351RTF | AAT CCA TCG TTA TGG CGA AA | Detection |

| 1351RTR | GCC ATC GTG CTA AAT GGT TT | Detection |

| 16SF | TGG CAA TCA GCG TCA GGT AAT G | RT-PCR |

| 16SR | GCT AAG AGA TCA GCC | RT-PCR |

| katAf | GCG GCG TTT GAC AGA GAA (8) | qPCR |

| katAr | TTT GAT CGC ATC ACG GAT AA (8) | qPCR |

| 0835f | GCG ATC AGT GCC TTT ACT TTG G | qPCR |

| 0835r | CGA TCA ACT CCA CGC TTT CA | qPCR |

| 818 | GGA GTA CGG TCG CA AGAT TAA A (8) | qPCR |

| 909 | CTA GCG GAT TCT CTC AAT GTC AA (8) | qPCR |

For RNA isolation, liquid cultures of wild-type and mutant bacteria were harvested at exponential phase, treated with RNAprotect reagent (Qiagen), and processed for RNA isolation using an RNeasy Midi kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA was treated with DNase I (Ambion, Austin, TX) for 30 min and extracted using phenol-chloroform, followed by ethanol precipitation. A high-capacity cDNA RT kit (Applied Biosystems) was used in the RT-PCR, also according to the manufacturer's instructions. As a negative control, the RT-PCR was performed without the addition of the reverse transcriptase enzyme.

The qPCR reactions were performed with an ABI PRISM 7500 sequence detection system (ABI) using a SYBR green kit (Applied Biosystems). The primers for the reactions are listed in Table 1. Seven genes fulfilling the criteria of containing GANTC sites upstream of the ORFs and having GANTC sites present in both strain 26695 and strain J99 were chosen. The following genes were analyzed: cag13 (HP0534), cag16 (HP0537), cag21 (HP0542), katA, HP0835, HP0922, and HP1564. As an endogenous control, the 16S rRNA gene was used after verification that the expression of this gene was the same in the wild type as in the mutant strain. The amplification efficiencies for the primers were calculated from a standard curve using a 10-fold dilution series of cDNA. The qPCR reactions were performed according to standard protocols. Calculation of the relative gene expression was done using the Q-gene software (24) (Biotechniques software library, http://www.biotechniques.com).

Sequencing.

Primers used for sequencing are shown in Table 1. PCR products amplified with primers targeting the flanking sequences of the M.HpyAIV gene and purified using GFX DNA and a gel band purification kit (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) were used as templates in the sequencing reaction. Cycle sequencing was performed using BigDye Terminator v3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and the products were separated on an ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer. All sequences were analyzed and aligned using Vector NTI, suite 9.0.0 (Invitrogen).

Construction of M.HpyAIV gene insertion mutants.

PCR products of the M.HpyAIV gene were amplified from 26695 DNA by use of primers HP1352F and HP1352R. The PCR amplicons were purified using GFX DNA and a gel band purification kit (Amersham) and cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). The M.HpyAIV gene insert was then cleaved out of the pGEM-T Easy vector with NotI and cloned into a new vector, pGEM-5zf(+), which was digested with NotI to generate one insertion site. To avoid self-ligation, the NotI-linearized pGEM-5zf(+) vector (Promega) was treated with alkaline phosphatase from calf intestinal mucosa (Promega). The new vector construction was transformed into competent Escherichia coli cells (DH5α) by heat shock, and the insertion of the correct fragment was confirmed by PCR. HindIII (New England Biolabs) was used to generate one restriction site in the M.HpyAIV gene situated in pGEM-5zf(+) and to cleave out the kanamycin cassette gene from pJMK30 (13). The marker gene was purified, cloned into the linearized vector, and transformed to competent E. coli cells (DH5α) by heat shock, and the transformants were selected on LB agar plates containing 30 μg/ml kanamycin. Plasmids were isolated with a Qiagen plasmid mini or Midi kit according to manufacturer's protocols. To obtain H. pylori insertion mutants, plasmids were electroporated to confluently grown bacteria by use of standard methods and selected on kanamycin-containing GC agar plates (30 μg/ml). PCR and sequencing were used to confirm that the M.HpyAIV::Km construct was inserted into the correct location.

Measurement of interleukin-8 induction in AGS cells.

AGS cells, from a gastric cancer cell line, were infected with either H. pylori 26695 wild-type or M.HpyAIV gene mutant strains. Measurement of interleukin-8 secretion in the supernatant of H. pylori-infected AGS cells was performed as described earlier (25).

DNA-binding assay.

The M.HpyAIV gene (HP1352) from strain 26695 was expressed and purified in E. coli as previously described (36). P32-labeled PCR fragments (0.32 pmol) containing one single GANTC site (109 bp, amplified from strain 26695 by use of primers EMSF and EMSR) (Table 1) were mixed with 1 μl NEB2 buffer (50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.9 [New England Biolabs], and 0, 10, 30, 80, 150, 200, or 500 nM purified M.HpyAIV protein). The reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The samples were analyzed using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (4% native polyacrylamide gel for 5 h, 200 V). The results were evaluated using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics Inc.).

Protection from restriction digestion by methylation.

To investigate methylation and protection by the recombinant protein, we incubated 1 μg of a PCR fragment containing one GANTC site (778 bp, amplified with 1351GANTCF and 1351GANTCR) (Table 1) with NEB2 buffer, S-adenosylmethionine (New England BioLabs), and different M.HpyAIV concentrations (0, 200, 400, 800, and 1,200 nM) and performed incubation for 1 h at room temperature followed by protein inactivation at 95°C for 10 min. Samples were digested with HinfI overnight at 37°C. The quantities of digested and undigested PCR products were determined on a Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA) in duplicate.

Heat shock stress response.

Bacteria were grown in liquid Brucella broth to an optical density at 600 nm of approximately 0.2. Aliquots of mutant and wild-type strains were transferred from cultures at 37 to 42°C. Viable counts were performed at different time points between 0 and 180 min after exposure. Samples from mutant and wild-type strains were analyzed in duplicate.

In silico genomic analysis.

Genome sequences and gene annotations of strains 26695 and J99 were downloaded from NCBI. In-house-developed PERL scripts were used to search the intragenic, including start and stop codons, and intergenic regions for GANTC occurrences. For the construction of randomized 26695 genomes, the nucleotide order within intergenic regions was shuffled by performing 10,000 random pair-wise exchanges of nucleotides within the same intergenic region, whereas intragenic regions were randomized by performing 10,000 random pair-wise exchanges of codons encoding the same amino acid within the same gene, excluding start and stop codons.

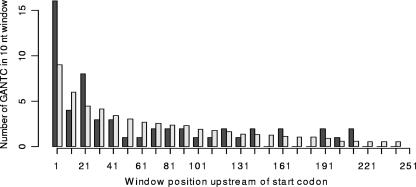

The intergenic distribution of GANTC sites was analyzed by dividing each intergenic region containing (exactly) one GANTC site into 10-nucleotide (nt) nonoverlapping windows {w1, w2, …, wn}, starting immediately upstream of the start codon. When a partial window remained, this was excluded, and if the GANTC was located within this, the intergenic region was excluded from the analysis. GANTC occurrences were then summarized for all windows {w1, w2, …, wn}, over all intergenic regions, where n is the number of windows in the longest intergenic region. This distribution was then compared to those obtained after randomly positioning the GANTC within the same intergenic regions. Ten thousand such randomized distributions were created, and for each window a P value of GANTC enrichment was calculated as the proportion of the randomized distributions containing at least as many GANTC sites as the original distribution in that window. Functional classifications of different genes were obtained from the Pasteur Institute (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/PyloriGene/index.html).

RESULTS

Presence and activity of the R.HpyAIV-M.HpyAIV gene system in clinical H. pylori isolates.

We investigated the presence of the M.HpyAIV gene in Swedish clinical H. pylori isolates by PCR. Assuming that the primer binding sites were present in these strains, we detected the M.HpyAIV gene in 60% (36/60) of the analyzed strains, and the cognate REase gene, the R.HpyAIV gene, was present in 53% (32/60) of the analyzed strains. A complete R-M system was found in 47% (28/60) of the strains.

To examine the methylation activity of M.HpyAIV, genomic DNA from the same strains mentioned above was digested with HinfI. Resistance or susceptibility to HinfI digestion indicates the presence or absence of an active MTase, respectively. The results showed that the M.HpyAIV gene was active in 42% (25/60) of the strains, while no activity was demonstrated for the remaining 58% (35/60). None of the strains lacking the M.HpyAIV gene as judged by the PCR test could be digested with HinfI, indicating a good correlation between the PCR test and the HinfI digestion test. The presence of the gene, however, did not directly correlate to activity, since 31% (11/35) of the strains had no M.HpyAIV activity, even though the M.HpyAIV gene was present. To identify possible genetic alterations that would explain the lack of methylation activity although the gene was present according to the PCR result, we sequenced the M.HpyAIV gene in 10 strains with inactive and 6 strains with active M.HpyAIV. In six of the inactive strains, one adenine residue was absent in a homopolymeric tract of adenine residues. In one of the inactive strains, an additional cytosine was present in a repeated poly(C) tract, as compared to the sequence of the gene in the strains with an active MTase. Both these genetic changes are predicted to result in the generation of premature translational stops, which in turn may result in truncated proteins. No genetic alterations which could explain the inactivity were found for 3 of the 10 analyzed strains.

The H. pylori strains used for PCR and activity tests originated from patients diagnosed with a range of gastroduodenal diseases (Table 2) . The presence of the active MTase could not with statistical significance be linked to a more severe disease development (Fisher's exact test; data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of R.HpyAIV-M.HpyAIV genesa

| Isolate clinical background | % (no./total no.) presence of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| hpyAIVM | hpyAIVR | Active MTase | |

| Gastric cancer and duodenal ulcer | 62 (21/34) | 53 (18/34) | 41 (14/29) |

| Nonulcer dyspepsia | 58 (15/26) | 54 (14/26) | 42 (11/26) |

| Total | 60 (36/60) | 53 (32/60) | 42 (25/60) |

Distribution of R.HpyAIV-M.HpyAIV genes in strains obtained from patients with differing clinical backgrounds, as assessed by PCR. M.HpyAIV activity was investigated by HinfI digestion of genomic DNA isolated from the different strains.

M.HpyAIV activity of single-cell colony isolates.

To further investigate the variation in the homopolymeric tracts of the M.HpyAIV gene, we investigated whether phenotypic and genotypic alterations of the gene occurred in vivo by analyzing populations of 10 single colonies obtained from five different individuals. DNA sequencing of these samples yielded no variation in the sequence of the M.HpyAIV gene locus. All single colonies from two individuals carried the gene and the genomic DNA was protected from GANTC digestion, while for two of the individuals no MTase activity was found and the MTase gene was absent. However, one of the individuals had two colonies with active and eight colonies with inactive MTase; that is, genomic DNA from 2 of 10 single-cell colonies was protected from HinfI digestion (data not shown). In these two isolates, both the M.HpyAIV and the R.HpyAIV genes were detected by PCR, in contrast to the eight other isolates obtained from the same patient, where both R-M genes were absent.

Characterization of the M.HpyAIV gene knockout mutant.

To investigate the function of M.HpyAIV, a knockout mutant was created from strain 26695. Isolated mRNA from wild-type and mutant bacteria grown to exponential phase was analyzed by RT-PCR. We were able to amplify M.HpyAIV and R.HpyAIV gene transcripts in the wild type but not in the M.HpyAIV gene mutant strain, which indicated a lack of transcription of both MTase and REase genes in the latter (data not shown). To determine the ability of M.HpyIVM to modify GANTC sites, HinfI was used for the digestion of genomic DNA isolated from the wild type and the M.HpyAIV gene mutant. As expected, HinfI was not able to cleave the genomic DNA of the wild type, but the M.HpyAIV gene mutant DNA was digested (data not shown). This showed that M.HpyAIV is active in H. pylori strain 26695 and is necessary for this site-specific methylation.

In vitro analysis of recombinant M.HpyAIV protein.

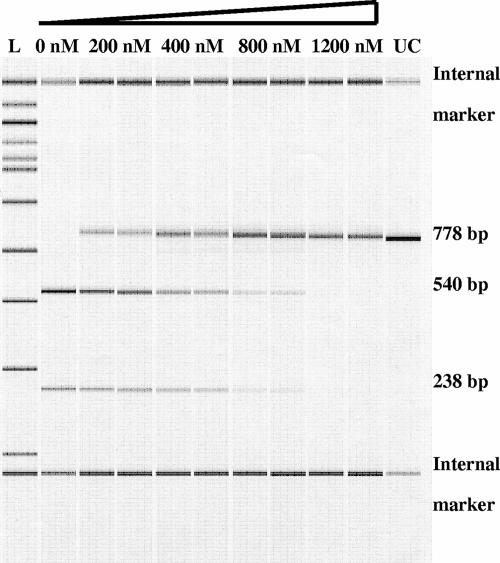

To investigate the enzymatic activity of M.HpyAIV, the protein was purified from 26695 and analyzed in vitro. First, the DNA-binding capacity of the purified M.HpyAIV protein was studied in a gel shift assay (data not shown). At protein concentrations of 30 nM and above, gel retardation was obtained, indicating that the purified enzyme was bound to the DNA sample. To further assess the capability of M.HpyAIV to methylate GANTC sites, we analyzed the ability of the purified protein to protect DNA from digestion by HinfI in vitro (Fig. 2). Various concentrations of M.HpyAIV protein were incubated with a PCR fragment (778 bp) containing one GANTC site for 1 h followed by inactivation of the MTase and digestion with HinfI. Capillary electrophoresis using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA) was used to analyze the results. The increased M.HpyAIV concentration resulted in increased amounts of undigested PCR products, illustrating the capability of M.HpyAIV to protect GANTC sites from being digested in a concentration-dependent manner.

FIG. 2.

Purified M.HpyAIV protects a GANTC-containing DNA fragment from HinfI digestion. Increasing concentrations of M.HpyAIV protein incubated with a 778-bp PCR fragment containing one GANTC site and S-adenosylmethionine. HinfI digestion of the GANTC-containing DNA fragment resulted in two fragments of 540 bp and 238 bp. The increased amount of undigested PCR products as a consequence of an increased M.HpyAIV concentration illustrates the in vitro capability of M.HpyAIV to protect GANTC sites from digestion in a concentration-dependent manner. L, ladder (samples in duplicate with increasing amounts of M.HpyAIV added [0, 200, 400, 800, and 1,200 nM]); UC, uncut control.

Bioinformatic analysis of GANTC sites in 26695 and J99.

The genome of H. pylori possess a notably higher number of active MTases compared with REases (18, 19, 43), and it has been suggested that H. pylori MTases may have other functions, e.g., in gene regulation. Transcriptional regulation by methylation pattern has been described for other species, where differential methylation in promoter regions alters the interaction of regulatory proteins with their target DNAs (21).

We searched the distribution of GANTC sites, i.e., the potential regulatory sites in the two fully sequenced H. pylori genomes. In strain J99, 230 and 2,522 GANTC sites were located in inter- and intragenic regions, respectively. In strain 26995, the corresponding numbers were 231 and 2,508. This was compared with the numbers obtained in randomized 26695 genomes constructed by shuffling the nucleotide order within intergenic regions (thus preserving the nucleotide frequencies) and by performing pair-wise codon exchanges for randomly chosen codon pairs encoding the same amino acid within ORFs (thus preserving the protein sequences and codon frequencies). On average, 500 intergenic GANTC sites were found in each of the 100 randomized genomes (range, 446 to 558), and all of the genomes contained more sites than in the original 26695 strain (231 sites). The difference was less pronounced within genes, which showed 3,528 sites on average (range, 3,432 to 3,636), but also in this case, all genomes displayed more sites than the original (2,508).

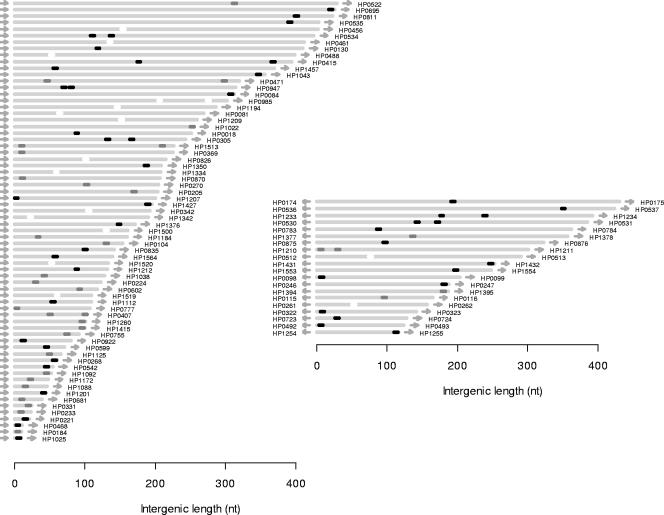

We then investigated how GANTC sites were distributed within intergenic regions. For GANTC-containing intergenic regions upstream of a single gene (located between adjacent genes on the same strand), we found that the region proximal to the start codon was significantly enriched in GANTC (P < 0.005) (Fig. 3 and 4). Thus, GANTC sites seem to be avoided in intergenic regions, but when they do occur, they are situated close to the translational start codon more often than expected by chance. We also examined how many of the intergenic GANTC sites located upstream of ORFs were common for both J99 and 26695 sequenced genomes. Sixty of these genes were common for both strains, distributed between different functional groups (Table 3). The functional group with the highest frequency of GANTC sites in potential promoter regions (6% out of the total number of genes) was the group containing genes involved in cellular processes. Interestingly, in this group, 9 of 13 genes belonged to the cag pathogenicity island.

FIG. 3.

Intergenic regions containing one or more GANTC sites in H. pylori strain 26695. Gray bars indicate region lengths. Black bars indicate that the J99 ortholog has upstream GANTC sites, while dark gray bars indicate the absence of upstream GANTC sites. White bars indicate that an ortholog in J99 is missing. Arrows indicate the direction of ORFs.

FIG. 4.

GANTC site distribution along intergenic regions of strain 26695 for true and randomized data. Intergenic regions containing one GANTC site were divided into 10-nt nonoverlapping windows, and the occurrences of GANTC sites (start positions) in each window were summarized over all intergenic regions (dark gray bars). Randomized data were obtained by randomly positioning the GANTC sites within each intergenic region and counting occurrences of GANTCs as before. The procedure was repeated 10,000 times, and average counts were calculated (light gray bars). *, P < 0.005; 38 of 10,000 randomizations displayed at least as many occurrences as observed. Intergenic regions extending 260 nt are not shown.

TABLE 3.

ORFs that contain GANTC sites upstream of translational start codons in strains 26695 and J99 and those common for both strainsa

| Functional group (total number of ORFs in each group) | No. of genes (% of total):

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| In 26695 | In J99 | Common for both 26695 and J99 | |

| Amino acid biosynthesis (89) | 5 (5.6) | 5 (5.6) | 2 (2.2) |

| Purines, pyrimidines, nucleosides, and nucleotides (104) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Fatty acid and phospholipid metabolism (55) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.8) |

| Biosynthesis of cofactors, prosthetic groups, and carriers (148) | 5 (3.4) | 4 (2.7) | 2 (1.4) |

| Central intermediary metabolism (30) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) |

| Energy metabolism (199) | 3 (1.5) | 4 (2.0) | 2 (1.0) |

| Transport and binding proteins (213) | 7 (3.3) | 7 (3.3) | 4 (1.9) |

| DNA metabolism (220) | 10 (4.5) | 7 (3.2) | 2 (0.9) |

| Transcription (36) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) |

| Protein synthesis (216) | 8 (3.7) | 7 (3.2) | 6 (2.8) |

| Protein fate (131) | 4 (3.1) | 3 (2.3) | 3 (2.3) |

| Regulatory functions (56) | 2 (3.6) | 4 (7.1) | 2 (3.6) |

| Cell envelope (309) | 13 (4.2) | 14 (4.5) | 6 (1.9) |

| Cellular processes (226) | 16 (7.1) | 16 (7.1) | 13 (5.8) |

| Other categories (19) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown (58) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) |

| Hypothetical (1,047) | 44 (4.2) | 40 (3.8) | 15 (1.4) |

| Total (3,156) | 123 (3.9) | 119 (3.8) | 60 (1.9) |

The percentages of genes with GANTC sites were compared with the total number of genes present in each functional group.

qPCR.

qPCR of cDNA was performed to compare transcriptional levels between the wild type and the M.HpyAIV gene mutant strain. Amplification was carried out in triplicate from three different cDNA preparations. A statistically significant decrease from the wild-type level (P < 0.05) could be detected for katA, the gene encoding the H. pylori catalase. The normalized gene expression in the mutant strain was 0.2-fold of that of the wild type (data not shown). A decrease in gene expression could also be seen for HP0835; however, this decrease was not statistically significant. No change in gene expression could be detected for any of the other genes analyzed.

DISCUSSION

H. pylori colonization usually progresses to a lifelong chronic infection. Little is yet known about how H. pylori manages to cause a persistent infection and why only a subset of individuals develops clinical symptoms. Strain-specific genes and altered gene expression in H. pylori may contribute to success in adapting to different hosts and may also be involved in disease development (2, 3, 11, 25, 29). Ten percent of the strain-specific genes in H. pylori comprise R-M systems (33). In this study, we characterized the R.HpyAIV-M.HpyAIV gene system. We showed that purified M.HpyAIV protein bound DNA and could protect GANTC sites from digestion in a concentration-dependent manner. The R.HpyAIV-M.HpyAIV gene system is not present in all H. pylori strains; in our PCR analysis, a complete R-M system was found in 47% of the investigated isolates (28/60) and active GANTC site methylation was found in 42% of the tested H. pylori isolates (25/60). These results are similar to those obtained by Takata et al. (41), where 55% of their analyzed strains were resistant to digestion by HinfI.

Phase variation is described as a mechanism where simple repetitive DNA motifs lose or gain repeats during replication, which in turn may lead to premature translational stop codons and truncated proteins, and is proposed to help the bacteria to adapt to changes in environmental conditions and immune evasion (15, 34). In H. pylori, three major groups of genes with short sequence repeats that may serve as targets for phase variations have been identified: cell surface-associated genes, R-M systems, and genes involved in lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis (3, 9, 26, 35). We observed variability in intergenic homopolymeric tracts in strains that possessed the M.HpyAIV gene. A nucleotide insertion or deletion in these homopolymeric tracts results in an inactive M.HpyAIV, suggesting that this gene may phase vary by slipped-strand DNA mispairing.

From an in vivo-propagated population of H. pylori single-colony isolates, we found no evidence for frequent MTase inactivation due to the slipped-strand mispairing mechanism. It is likely that the number of repeated nucleotides present in a phase-variable region influences the rate of slipped-strand mispairing. In the investigated material, seven adenine residues were present in active strains, a rather short repetitive sequence. The region may therefore be too short for high-frequency slipped-strand mispairing. In single-cell colonies obtained from the same individual, we found that both the MTase and REase genes were either present or absent in these colonies, which may indicate reacquisition/deletion of the complete R-M system, as described by Takata et al. (41). In their study, 113-bp repeats flanking the R.HpyAIV-M.HpyAIV gene system upstream and downstream in strains 26695 and J99 are described. They showed that in related strains lacking the entire R-M system, a deletion PCR product using primers targeting flanking genes contained only one copy of the 113-bp repeat, which indicates that the R-M system is a mobile genetic element. For a type III R-M system, there is evidence of the coordinated transcription of the res and mod genes (restriction and modification subunits in type III R-M systems) (9). Coregulated transcription is probably common in R-M systems, since the lack of an active MTase in combination with a corresponding active REase could digest the self-DNA, which would be lethal for the strain. Usually, nonmethylated plasmid vectors are difficult to transform to H. pylori strains, due to the various numbers of R-M systems. It would be interesting in future studies to investigate if modifications of R-M systems increase the possibility of circumventing these problems in experimental strains.

According to RT-PCR results, both the MTase and the REase were transcribed in the wild type, but neither transcript was detected in the mutant strain. In the mutant strain, the lack of a transcript of the REase gene, situated downstream of the MTase, may indicate that a coregulatory mechanism inactivates the transcription of this gene, since R.HpyAIV in strain 26695 has been described as active elsewhere (19).

Although both R.HpyAIV-M.HpyAIV genes were present in most of our strains, the activity of the REase was not investigated, and other studies have shown that it is not unusual that strains have active MTases but inactive REases (18, 19, 43); this suggests that it might be beneficial for the bacteria to preserve specific MTase function or that there is no selective advantage to preserve the REase.

Previous studies have shown that R-M systems are associated with the outcome of H. pylori infection. Expression of the type II REase iceA1 was up-regulated upon contact with epithelial cells. Two iceA alleles have been found (iceA1 and iceA2); iceA1 strains are associated with peptic ulcer disease (30). The inactivation of the cognate MTase M.HpyI results in the alteration of dnaK operon transcript levels in stationary-phase cultures and following host cell contact in vitro (10). In another study, mutants with decreased adherence and elongated cell structure were identified. The change in phenotype was due to a knockout of a type II REase gene, the R.HpyC1I gene (20). The M.HpyAIV gene and other genes belonging to R-M systems (type I hsdS genes) were associated with a high host response in transgenic mouse models (7). These different studies indicate that some H. pylori R-M systems may be important when the gastric environment changes and in response to the host.

An MTase with the same GANTC specificity as M.HpyAIV, CcrM, has a regulatory role in C. crescentus, Brucella abortus, Rhizobium meliloti, and Agrobacterium tumefaciens. In these alphaproteobacteria, CcrM is essential for viability (17, 32, 37, 47). However, in the case of H. pylori, we showed that M.HpyAIV is not essential for viability and that the isogenic mutant does not have reduced growth compared to the wild-type strain in liquid culture; moreover, no difference in heat shock survival was observed.

The in silico analysis showed that there are fewer GANTC sites present in the sequenced genomes, especially in intergenic regions, than would be expected by chance. This might imply that the presence of GANTC sites is avoided and might affect gene expression if present at a higher frequency, possibly by the methylation of these sites. Sixty GANTC sites upstream of ORFs were conserved between strains 26695 and J99. These may represent candidates for genes that are regulated by GANTC methylation. Interestingly, the largest group of genes found consisted of genes that belonged to the cag pathogenicity island. However, in our qPCR assay, none of the cag genes tested were affected in the mutant strain. An explanation may be that the RNA in our assay was isolated in exponential phase, and other settings may have had different results. Nevertheless, katA transcription levels were found to be down-regulated in the mutant strain. Since M.HpyAIV is not present in all H. pylori strains, the effect of transcriptional regulation is not essential but may give rise to strain-specific alterations which could cause the strains to become more or less virulent.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Åke Wiberg Foundation, and the Magnus Bergwall Foundation.

Thanks to Lena Eriksson for help with RNA isolation and to Annelie Lundin for help with the heat shock assay.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akopyanz, N., N. O. Bukanov, T. U. Westblom, and D. E. Berg. 1992. PCR-based RFLP analysis of DNA sequence diversity in the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:6221-6225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alm, R. A., L. S. Ling, D. T. Moir, B. L. King, E. D. Brown, P. C. Doig, D. R. Smith, B. Noonan, B. C. Guild, B. L. deJonge, G. Carmel, P. J. Tummino, A. Caruso, M. Uria-Nickelsen, D. M. Mills, C. Ives, R. Gibson, D. Merberg, S. D. Mills, Q. Jiang, D. E. Taylor, G. F. Vovis, and T. J. Trust. 1999. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 397:176-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appelmelk, B. J., S. L. Martin, M. A. Monteiro, C. A. Clayton, A. A. McColm, P. Zheng, T. Verboom, J. J. Maaskant, D. H. van den Eijnden, C. H. Hokke, M. B. Perry, C. M. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, and J. G. Kusters. 1999. Phase variation in Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide due to changes in the lengths of poly(C) tracts in α3-fucosyltransferase genes. Infect. Immun. 67:5361-5366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aro, P., T. Storskrubb, J. Ronkainen, E. Bolling-Sternevald, L. Engstrand, M. Vieth, M. Stolte, N. J. Talley, and L. Agreus. 2006. Peptic ulcer disease in a general adult population: the Kalixanda study: a random population-based study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 163:1025-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atherton, J. C., P. Cao, R. M. J. Peek, M. K. Tummuru, M. J. Blaser, and T. L. Cover. 1995. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. Association of specific vacA types with cytotoxin production and peptic ulceration. J. Biol. Chem. 270:17771-17777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Björkholm, B., A. Lundin, A. Sillen, K. Guillemin, N. Salama, C. Rubio, J. I. Gordon, P. Falk, and L. Engstrand. 2001. Comparison of genetic divergence and fitness between two subclones of Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 69:7832-7838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Björkholm, B. M., J. L. Guruge, J. D. Oh, A. J. Syder, N. Salama, K. Guillemin, S. Falkow, C. Nilsson, P. G. Falk, L. Engstrand, and J. I. Gordon. 2002. Colonization of germ-free transgenic mice with genotyped Helicobacter pylori strains from a case-control study of gastric cancer reveals a correlation between host responses and HsdS components of type I restriction-modification systems. J. Biol. Chem. 277:34191-34197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boonjakuakul, J. K., D. R. Canfield, and J. V. Solnick. 2005. Comparison of Helicobacter pylori virulence gene expression in vitro and in the rhesus macaque. Infect. Immun. 73:4895-4904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vries, N., D. Duinsbergen, E. J. Kuipers, R. G. Pot, P. Wiesenekker, C. W. Penn, A. H. van Vliet, C. M. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, and J. G. Kusters. 2002. Transcriptional phase variation of a type III restriction-modification system in Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 184:6615-6623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donahue, J. P., D. A. Israel, V. J. Torres, A. S. Necheva, and G. G. Miller. 2002. Inactivation of a Helicobacter pylori DNA methyltransferase alters dnaK operon expression following host-cell adherence. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 208:295-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donahue, J. P., R. M. Peek, L. J. Van Doorn, S. A. Thompson, Q. Xu, M. J. Blaser, and G. G. Miller. 2000. Analysis of iceA1 transcription in Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 5(1):1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enroth, H., W. Kraaz, L. Engstrand, O. Nyrén, and T. Rohan. 2000. Helicobacter pylori strain types and risk of gastric cancer: a case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 9:981-985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrero, R. L., V. Cussac, P. Courcoux, and A. Labigne. 1992. Construction of isogenic urease-negative mutants of Helicobacter pylori by allelic exchange. J. Bacteriol. 174:4212-4217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reference deleted.

- 15.Hallet, B. 2001. Playing Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: combined mechanisms of phase variation in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:570-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heithoff, D. M., R. L. Sinsheimer, D. A. Low, and M. J. Mahan. 1999. An essential role for DNA adenine methylation in bacterial virulence. Science 284:967-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahng, L. S., and L. Shapiro. 2001. The CcrM DNA methyltransferase of Agrobacterium tumefaciens is essential, and its activity is cell cycle regulated. J. Bacteriol. 183:3065-3075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong, H., L. F. Lin, N. Porter, S. Stickel, D. Byrd, J. Posfai, and R. J. Roberts. 2000. Functional analysis of putative restriction-modification system genes in the Helicobacter pylori J99 genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:3216-3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin, L. F., J. Posfai, R. J. Roberts, and H. Kong. 2001. Comparative genomics of the restriction-modification systems in Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:2740-2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin, T. L., C. T. Shun, K. C. Chang, and J. T. Wang. 2004. Isolation and characterization of a HpyC1I restriction-modification system in Helicobacter pylori. J. Biol. Chem. 279:11156-11162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Low, D. A., N. J. Weyand, and M. J. Mahan. 2001. Roles of DNA adenine methylation in regulating bacterial gene expression and virulence. Infect. Immun. 69:7197-7204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Messer, W., and M. Noyer-Weidner. 1988. Timing and targeting: the biological functions of Dam methylation in E. coli. Cell 54:735-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Modrich, P. 1989. Methyl-directed DNA mismatch correction. J. Biol. Chem. 264:6597-6600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller, P. Y., H. Janovjak, A. R. Miserez, and Z. Dobbie. 2002. Processing of gene expression data generated by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. BioTechniques 32:1372-1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nilsson, C., A. Sillén, L. Eriksson, M. L. Strand, H. Enroth, S. Normark, P. Falk, and L. Engstrand. 2003. Correlation between cag pathogenicity island composition and Helicobacter pylori-associated gastroduodenal disease. Infect. Immun. 71:6573-6581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nilsson, C., A. Skoglund, A. P. Moran, H. Annuk, L. Engstrand, and S. Normark. 2006. An enzymatic ruler modulates Lewis antigen glycosylation of Helicobacter pylori LPS during persistent infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:2863-2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oh, J. D., H. Kling-Bäckhed, M. Giannakis, J. Xu, R. S. Fulton, L. A. Fulton, H. S. Cordum, C. Wang, G. Elliott, J. Edwards, E. R. Mardis, L. G. Engstrand, and J. I. Gordon. 2006. The complete genome sequence of a chronic atrophic gastritis Helicobacter pylori strain: evolution during disease development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:9999-10004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peek, R. M., Jr., and M. J. Blaser. 2002. Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2:28-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peek, R. M., Jr., G. G. Miller, K. T. Tham, G. I. Perez-Perez, X. Zhao, J. C. Atherton, and M. J. Blaser. 1995. Heightened inflammatory response and cytokine expression in vivo to cagA+ Helicobacter pylori strains. Lab. Investig. 73:760-770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peek, R. M., Jr., S. A. Thompson, J. P. Donahue, K. T. Tham, J. C. Atherton, M. J. Blaser, and G. G. Miller. 1998. Adherence to gastric epithelial cells induces expression of a Helicobacter pylori gene, iceA, that is associated with clinical outcome. Proc. Assoc. Am. Physicians 110:531-544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts, D., B. C. Hoopes, W. R. McClure, and N. Kleckner. 1985. IS10 transposition is regulated by DNA adenine methylation. Cell 43:117-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robertson, G. T., A. Reisenauer, R. Wright, R. B. Jensen, A. Jensen, L. Shapiro, and R. M. N. Roop. 2000. The Brucella abortus CcrM DNA methyltransferase is essential for viability, and its overexpression attenuates intracellular replication in murine macrophages. J. Bacteriol. 182:3482-3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salama, N., K. Guillemin, T. K. McDaniel, G. Sherlock, L. Tompkins, and S. Falkow. 2000. A whole-genome microarray reveals genetic diversity among Helicobacter pylori strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14668-14673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salaun, L., L. A. Snyder, and N. J. Saunders. 2003. Adaptation by phase variation in pathogenic bacteria. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 52:263-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saunders, N. J., J. F. Peden, D. W. Hood, and E. R. Moxon. 1998. Simple sequence repeats in the Helicobacter pylori genome. Mol. Microbiol. 27:1091-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schirwitz, K., A. Lundin, A. Skoglund, M. Krabbe, L. Engstrand, and C. Enroth. 2003. Cloning, expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of HP1352, a putative DNA methyltransferase in Helicobacter pylori. Acta Crystallogr. D 59:719-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephens, C., A. Reisenauer, R. Wright, and L. Shapiro. 1996. A cell cycle-regulated bacterial DNA methyltransferase is essential for viability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:1210-1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Storskrubb, T., P. Aro, J. Ronkainen, M. Vieth, M. Stolte, K. Wreiber, L. Engstrand, H. Nyhlin, E. Bolling-Sternevald, N. J. Talley, and L. Agreus. 2005. A negative Helicobacter pylori serology test is more reliable for exclusion of premalignant gastric conditions than a negative test for current H. pylori infection: a report on histology and H. pylori detection in the general adult population. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 40:302-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suerbaum, S., J. M. Smith, K. Bapumia, G. Morelli, N. H. Smith, E. Kunstmann, I. Dyrek, and M. Achtman. 1998. Free recombination within Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:12619-12624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takahashi, N., Y. Naito, N. Handa, and I. Kobayashi. 2002. A DNA methyltransferase can protect the genome from postdisturbance attack by a restriction-modification gene complex. J. Bacteriol. 184:6100-6108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takata, T., R. Aras, D. Tavakoli, T. Ando, A. Z. Olivares, and M. J. Blaser. 2002. Phenotypic and genotypic variation in methylases involved in type II restriction-modification systems in Helicobacter pylori. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:2444-2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomb, J. F., O. White, A. R. Kerlavage, R. A. Clayton, G. G. Sutton, R. D. Fleischmann, K. A. Ketchum, H. P. Klenk, S. Gill, B. A. Dougherty, K. Nelson, J. Quackenbush, L. Zhou, E. F. Kirkness, S. Peterson, B. Loftus, D. Richardson, R. Dodson, H. G. Khalak, A. Glodek, K. McKenney, L. M. Fitzegerald, N. Lee, M. D. Adams, E. K. Hickey, D. E. Berg, J. D. Gocayne, T. R. Utterback, J. D. Peterson, J. M. Kelley, M. D. Cotton, J. M. Weldman, C. Fujii, C. Bowman, L. Watthey, E. Wallin, W. S. Hayes, M. Boradovsky, P. D. Karp, H. O. Smith, C. M. Fraser, and J. C. Venter. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 388:539-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vitkute, J., K. Stankevicius, G. Tamulaitiene, Z. Maneliene, A. Timinskas, D. E. Berg, and A. Janulaitis. 2001. Specificities of eleven different DNA methyltransferases of Helicobacter pylori strain 26695. J. Bacteriol. 183:443-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weel, J. F., R. W. van der Hulst, Y. Gerrits, P. Roorda, M. Feller, J. Dankert, G. N. Tytgat, and A. van der Ende. 1996. The interrelationship between cytotoxin-associated gene A, vacuolating cytotoxin, and Helicobacter pylori-related diseases. J. Infect. Dis. 173:1171-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson, G. G. 1991. Organization of restriction-modification systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:2539-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson, G. G., and N. E. Murray. 1991. Restriction and modification systems. Annu. Rev. Gen. 25:585-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wright, R., C. Stephens, and L. Shapiro. 1997. The CcrM DNA methyltransferase is widespread in the alpha subdivision of proteobacteria, and its essential functions are conserved in Rhizobium meliloti and Caulobacter crescentus. J. Bacteriol. 179:5869-5877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]