Abstract

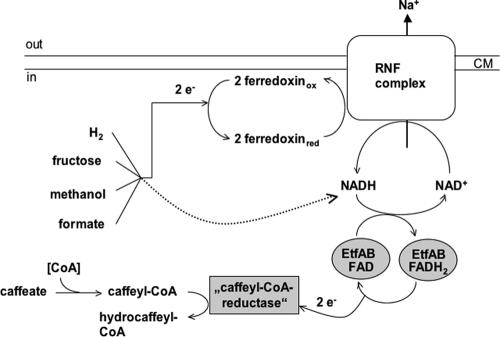

The anaerobic acetogenic bacterium Acetobacterium woodii couples caffeate reduction with electrons derived from hydrogen to the synthesis of ATP by a chemiosmotic mechanism with sodium ions as coupling ions, a process referred to as caffeate respiration. We addressed the nature of the hitherto unknown enzymatic activities involved in this process and their cellular localization. Cell extract of A. woodii catalyzes H2-dependent caffeate reduction. This reaction is strictly ATP dependent but can be activated also by acetyl coenzyme A (CoA), indicating that there is formation of caffeyl-CoA prior to reduction. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis revealed proteins present only in caffeate-grown cells. Two proteins were identified by electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry, and the encoding genes were cloned. These proteins are very similar to subunits α (EtfA) and β (EtfB) of electron transfer flavoproteins present in various anaerobic bacteria. Western blot analysis demonstrated that they are induced by caffeate and localized in the cytoplasm. Etf proteins are known electron carriers that shuttle electrons from NADH to different acceptors. Indeed, NADH was used as an electron donor for cytosolic caffeate reduction. Since the hydrogenase was soluble and used ferredoxin as an electron acceptor, the missing link was a ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase. This activity could be determined and, interestingly, was membrane bound. A search for genes that could encode this activity revealed DNA fragments encoding subunits C and D of a membrane-bound Rnf-type NADH dehydrogenase that is a potential Na+ pump. These data suggest the following electron transport chain: H2 → ferredoxin → NAD+ → Etf → caffeyl-CoA reductase. They also imply that the sodium motive step in the chain is the ferredoxin-dependent NAD+ reduction catalyzed by Rnf.

The acetogenic bacteria are a phylogenetically diverse group of strictly anaerobic bacteria that can oxidize a wide variety of different substrates, such as carbohydrates, C1 substrates (methyl groups, CO), molecular hydrogen, aromatic aldehydes, alcohols, and even dicarboxylic acids (13). Oxidation of carbohydrates, such as hexoses, proceeds via the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway to pyruvate, which is split by pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase to form acetyl coenzyme A (CoA), CO2, and reduced ferredoxin. Acetyl-CoA is further converted to acetate and CoA. The overall reaction is:

|

(1) |

The reducing equivalents are funneled to the CO2 produced, which is converted to acetate in the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway (32, 33, 40, 41) according to:

|

(2) |

The Wood-Ljungdahl pathway is also used by acetogens for chemolithoautotrophic growth according to:

|

(3) |

The Wood-Ljungdahl pathway is coupled to a chemiosmotic mechanism of ATP synthesis, but the ways in which the ion gradients are established are obscure.

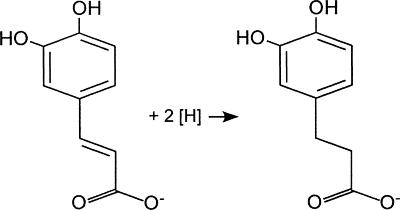

Acetogens can use not only CO2 but also alternative electron acceptors, including arylacrylates (2, 53), fumarate (11, 12, 35), dimethyl sulfoxide (3), and nitrate (17, 50). Acetobacterium woodii is known to reduce the carbon-carbon double bond of phenylacrylates, such as caffeate, as shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Reduction of the carbon-carbon double bond of phenylacrylates, such as caffeate, by A. woodii.

The electrons can be derived from various donors, such as fructose, methanol, or hydrogen. Cell yield measurements with cells grown on fructose or methyl group-containing substrates provided evidence that caffeate reduction is energy conserving (53). Very clear evidence for ATP synthesis coupled to caffeate reduction was obtained with resting cells of A. woodii in which hydrogen-dependent caffeate reduction was accompanied by synthesis of ATP (20). Later, it was shown that ATP synthesis during caffeate reduction with electrons derived from molecular hydrogen occurs by a chemiosmotic mechanism. Interestingly, the coupling ion is Na+ and not H+ (24). Again, the enzymes involved in reduction of caffeate and energy conservation remained unknown. We followed up these studies with the aim of identifying the components involved in caffeate respiration, with special emphasis on the Na+-translocating enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this work are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli cultures were grown under aerobic conditions in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C and 180 rpm. A. woodii was cultivated at 30°C in 100-ml hypovials (for Western blot analysis) or in 20-liter flasks (Glasgerätebau Ochs, Bovenden-Lenglern, Germany) for preparation of cell extracts (CFE). Stock cultures were grown in Hungate tubes. The medium was prepared using the anaerobic techniques described previously (8, 23). The medium contained under an N2-CO2 (80:20, vol/vol) atmosphere (per liter) 1.76 g of KH2PO4, 8.44 g of K2HPO4, 1.0 g of NH4Cl, 0.5 g of cysteine hydrochloride, 0.33 g of MgSO4·6H2O, 2.9 g of NaCl, 6.0 g of KHCO3, 2.0 g of yeast extract, 1.0 ml of trace element solution SL 9, 1.0 ml of a selenite-tungstate solution, and 2.0 ml of vitamin solution DSMZ 141. The pH was adjusted to 7.1 to 7.2 with HCl. Fructose, methanol, and formate were used as carbon sources at final concentrations of 20, 60, and 200 mM, respectively. For growth on H2-CO2 (80:20, vol/vol) 100-ml hypovials were constantly gassed (0.8 × 105 Pa) and shaken at 180 rpm in a water bath at 30°C. Caffeate, ferulate, and p-coumarate were added from 1 M stock solutions to a final concentration of 10 mM. Growth was followed by measuring the optical density at 600 nm.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study

| Bacterial strain, plasmid, or primer | Genotype or sequence (5′-3′)a | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | F−recA1 endA2 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) sup44 relA1 λ− (φ80 ΔlacZΔM15) Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 | 19 |

| A. woodii | Wild type | DSM 1030 (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR 2.1-TOPO | Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany | |

| pMal-c2 | NEB, Frankfurt/Main, Germany | |

| Oligonucleotide primers | ||

| etfAforward | TGGGTNTTYGCNGARCARMGN | |

| etfAreverse | RTCNCCNACRATNCCRTARTC | |

| etfBforward | ATGGGNGCNGAYGARGCNTAY | |

| etfBreverse | NACRTANGTNACNACNGGCAT | |

| etfAforward BamHI | GTATTTGCCGGATCCCGTGAAG | |

| etfAreverse SalI | GTCGCCTACGTCGACGTAATC | |

| etfBforward EcoRI | GGAATTCATGGGGGCGGACGAAG | |

| etfBreverse PstI | AACTGCAGCGGTGGTCC | |

| iPCR_rev | GACAACCTTTTCAGCTTGCG | |

| iPCR_for | CCGGTGGACTATTGATGGG | |

| C2_for | GAATGCGAACCTTACTTAACT | |

| C2_rev | TCCCATCATAGGTCCACC |

In the primer sequences restriction sites introduced by PCR are underlined. N = A, C, G, or T; M = A or C; R = A or G; Y = C or T.

Preparation of CFE and membranes.

Cells were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.3 to 0.4. Then caffeate was added to induce the ability of the cells to reduce this compound. Cultures were harvested anaerobically at the end of the exponential growth phase by centrifugation (16,800 × g at 4°C; Contifuge Strato; Heraeus, Osterode, Germany) and washed three times with imidazole-HCl buffer (50 mM imidazole-HCl, 20 mM MgSO4, 5 mM dithioerythritol, 1 mg/liter of resazurin; pH 7). The cells were resuspended in 50 mM imidazole-HCl buffer (pH 8) containing 420 mM sucrose and were incubated with lysozyme (5 mg/ml) at 37°C and 100 rpm for 1.5 h. Then the cells were sedimented by centrifugation (2,700 × g, 20 min, 4°C) and resuspended in 50 mM imidazole-HCl buffer (pH 7) containing 420 mM sucrose. Cells were disrupted by a single passage through a French press (42 kPa). Cell debris and whole cells were removed by two centrifugation steps (2,700 × g, 30 min, 4°C). The CFE was separated into cytoplasmic and the membrane fractions by ultracentrifugation (190,000 × g, 16 h, 4°C). The resulting sediment was washed twice with 50 mM imidazole-HCl buffer (pH 7) containing 420 mM sucrose and was resuspended in the same buffer. Using two additional centrifugation steps (190,000 × g, 1.5 h, 4°C), the cytoplasm was separated from the residual membranes. The fractions were stored on ice under an N2 atmosphere and were used immediately for the experiments. Protein concentrations were determined as described previously (34). All manipulations were done under strictly anaerobic conditions.

Cloning of Etf genes and generation of antibodies.

Fragments of the EtfAAw and EtfBAw genes were amplified from chromosomal DNA of A. woodii (Table 1 shows the oligonucleotides used), cleaved with appropriate restriction enzymes, and cloned into the overexpression vector pMal-c2 (New England Biolabs GmbH, Frankfurt/Main, Germany). The plasmid constructs were sequenced by using custom-made primers. Maltose binding protein (MalE) fusion proteins were overproduced in E.coli DH5α and purified by affinity chromatography performed on immobilized amylose as recommended by the manufacturer (New England Biolabs GmbH, Frankfurt/Main, Germany). Purified fusion proteins were used for immunization of rabbits.

Western blot analysis.

Cells were harvested in the exponential growth phase, resuspended in sample buffer (46), and boiled for 10 min to lyse them. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was performed in 12.5% (wt/vol) acrylamide gels (46), using the “Prestained Protein Ladder” (11 to 170 kDa; MBI Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany) as the mass reference. The proteins were electrotransferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were blocked by incubation for 12 h at room temperature in PBST (140 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 16 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, 0.05% Tween 20) containing 2% bovine serum albumin. Immunodetection of EtfAAw and EtfBAw in total cell lysates or in membrane fractions was performed with polyclonal antisera (diluted 1/10,000) obtained from Davids Biotechnologie (Regensburg, Germany). Protein A-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Bio-Rad, München, Germany) was used as a secondary antibody in combination with a Lumi-Lightplus Western blotting substrate kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) to develop the chemiluminescence for visualization on Kodak X-AR film (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Quentin Falavier, France).

H2-dependent caffeate reduction in CFE.

Experiments were performed in 2.5-ml Hungate tubes (Glasgerätebau Ochs, Bovenden-Lenglern, Germany) under anaerobic conditions in the presence of N2. The tubes were supplemented with 500 μl CFE, 10 mM NaCl, ATP, acetyl-CoA, or CoA plus ATP as indicated below, which was followed by 10 min of incubation in a shaking water bath (180 rpm) at 30°C. The gas atmosphere was changed to H2, and the reaction was started by addition of caffeate. Samples were withdrawn with a syringe, and the caffeate concentration was determined as described previously (24).

NADH-dependent caffeate reduction in CFE.

Experiments were performed as described above for H2-dependent caffeate reduction, except that the N2 atmosphere was not changed and the reaction was started by addition of NADH to a final concentration of 10 mM. N,N,N′,N′-tetraphenyldiamine, 1,5-diphenylcarbazid, reduced methylviologen, or p-phenylenediamine was added to CFE to a final concentration of 10 mM. After 10 min of incubation the reaction was started by adding 10 mM caffeate.

NADH dehydrogenase activity.

Membranes of A. woodii exhibited an NADH-oxidizing activity under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Measurements were obtained under anaerobic conditions by using an N2 atmosphere. The assay buffer contained 50 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS), 20 mM MgSO4, and 20 mM NaCl, and the pH was adjusted to 7. Potassium hexacyanoferrate was used as the electron acceptor at a final concentration of 1 mM, which resulted in an increase in absorption of 0.5 U. The baseline was measured at 420 nm without addition of protein. The reaction was started by addition of 1 mM NADH. The activities measured were corrected against the baseline. The assay buffer used for measuring NADH dehydrogenase activity with benzylviologen (final concentration, 1 mM) as the electron acceptor contained 50 mM imidazole (pH 7.0), 20 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 5 mM dithioerythritol, and 1 mg resazurin/liter. The baseline was measured at 600 nm, and the reaction was started by adding 1 mM NADH.

Purification of ferredoxin from Clostridium tetanomorphum.

All buffers, media, and solutions were prepared anoxically by boiling them for 5 min and cooling them under a vacuum. After flushing with N2 gas, the buffers were transferred in gas-tight bottles into an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratories, Ann Arbor, MI), whose atmosphere consisted of 5% H2 and 95% N2. Complete removal of molecular oxygen was achieved by intensive stirring overnight. Wet packed C. tetanomorphum DSM 528 cells (20 g), grown on the Acidaminococcus medium with 100 mM glutamate (21), were suspended in 20 ml of 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.4) and broken anoxically by three passages through a French press at 100 MPa. The cell debris and membranes were removed by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 60 min. Ferredoxin was purified under anaerobic conditions from the supernatant by anion-exchange chromatography on a DEAE Sepharose Fast Flow column (26 by 100 mm) equilibrated with 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.4). A linear gradient from 0 to 2.0 M NaCl was applied, and two brown peaks at around 0.3 to 0.4 M NaCl and around 0.5 to 0.6 M NaCl were obtained. The second peak, which contained active ferredoxin (see below), was purified further by gel filtration on a calibrated Superdex 75 column (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex) equilibrated with 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.4) and 150 mM NaCl. The third protein peak (ca. 6 kDa), which had a brown color, was ferredoxin, and the yield was 0.7 mg (ca. 100 nmol) from 20 g of wet packed cells. It was stored at −20°C.

Ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase activity.

The ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase activity was measured using washed membranes of A. woodii under an N2 atmosphere. The anaerobic assay buffer contained 50 mM MOPS, 20 mM MgSO4, and 20 mM NaCl, and the pH was adjusted to 7 or 7.5. One milliliter of assay buffer was supplemented with aliquots of the membrane fraction. The baseline was measured at 340 nm. Ferredoxin was added to the assay buffer, and it was kept in the reduced state by using 1 mM Ti(III) citrate (58). The reaction was started by addition of 2.5 mM NAD+. Control experiments were performed using assay mixtures without ferredoxin and without ferredoxin and membranes. The measured activity was corrected against the baseline of the control assay.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.

For identification of proteins produced in the presence of caffeate, cells of A. woodii were grown to the late exponential phase with 20 mM fructose in the absence or presence of 10 mM caffeate and were harvested by centrifugation (2,700 × g, 15 min, 4°C). Cells were washed twice with 50 mM imidazole-HCl buffer and resuspended in the same buffer. Aliquots of the suspensions corresponding to a protein concentration of 1 mg were centrifuged (10,000 × g, 5 min), and the cells were lysed by resuspension in 100 μl denaturing buffer (9 M urea, 0.5% Triton X-100, 65 mM dithiothreitol, 20 μl/ml Bio-Lyte 3/10 ampholyte solution [Bio-Rad, München, Germany]) and 1 h of incubation on ice. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 5 min). Proteins were precipitated from the resulting supernatant with ice-cold acetone (1 h, −20°C). The protein sediment was dissolved in rehydration buffer (8 M urea, 0.5% Triton X-100, 13 mM dithiothreitol, 20 μl/ml Bio-Lyte 3/10 ampholyte solution) and subjected to two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.

The general method used for two-dimensional gel electrophoresis was the method of O'Farrell (36). The crude protein extract was used for isoelectric focusing in 18-cm precast immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips with a linear pH gradient from 4.0 to 7.0 using an IPGphor isoelectric focusing unit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). The second-dimension analysis was performed using 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (46). The gels were subsequently stained with Coomassie brilliant blue G250 (54). Protein concentrations of cell suspensions were determined as described previously (49).

Amplification of rnf genes and sequence determination.

PCR amplifications were carried out using Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes Oy, Espoo, Finland). Chromosomal DNA of A. woodii was digested with EcoRI and NdeI and then circularized by ligation for use as a template for inverse PCR amplification. The primers used to amplify borders of the central part of the rnfC gene were iPCR_rev and iPCR_for (Table 1). Inverse PCR was carried out using 30 amplification cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 5 min at 72°C. The central part of rnfC was amplified using the heterologous primers designed for Clostridium tetani, C2_for and C2_rev (Table 1). The standard conditions used for direct PCR amplification were 30 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 45°C, and 1 min at 72°C, followed by an elongation step of 10 min at 72°C. Amplified products were extracted from agarose gels using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). DNA sequencing of purified PCR fragments was performed by SRD, Frankfurt, Germany.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

DNA sequences have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers DQ845290 (etfAB), EU019308 (rnfC), and EU019309 (rnfD).

RESULTS

Hydrogen-dependent caffeate reduction in CFE is activated by ATP.

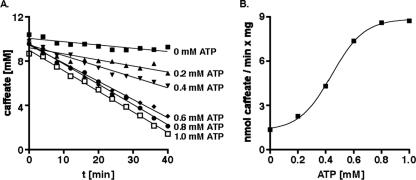

Previously, all experiments that addressed the mechanism of caffeate respiration were performed with whole cells. To obtain a more defined system, cells were grown on fructose plus caffeate, and CFE was prepared anaerobically from late-exponential-phase cells. Aliquots of the CFE were incubated under a hydrogen atmosphere in the presence of caffeate. Although hydrogenase is constitutive in A. woodii, we did not observe reduction of caffeate by the CFE. However, hydrogen-dependent caffeate reduction could be activated by addition of ATP (Fig. 2A). Maximal activation was observed with ∼1.0 mM ATP (Fig. 2B). The caffeate reduction rates were about 9 nmol/min/mg protein, which is about 20% of the rate observed with whole cells.

FIG. 2.

Activation of hydrogen-dependent caffeate reduction in CFE by ATP. (A) Aliquots (500 μl) of CFE (21.2 mg protein/ml) prepared from cells grown on fructose plus caffeate were incubated under an H2 atmosphere at 30°C in a shaking water bath. NaCl was added to a final concentration of 10 mM, and ATP was added at the concentrations indicated. At zero time caffeate was added to a final concentration of 10 mM. At the time points indicated samples were withdrawn and analyzed to determine the concentration of caffeate. (B) Caffeate reduction rate as a function of the ATP concentration.

Hydrogen-dependent caffeate reduction in CFE is stimulated by acetyl-CoA or CoA plus ATP.

Next, we tested the hypothesis that the activation of caffeate reduction by ATP is not due to the (re)activation of some enzyme involved in the process but, analogous to similar reductive reactions (1, 6, 14, 22, 37), is due to the activation of caffeate and subsequent formation of caffeyl-CoA prior to reduction. Addition of acetyl-CoA or CoA plus ATP resulted in an eightfold increase in the initial caffeate reduction rate, similar to ATP-dependent stimulation, indicating that there was formation of caffeyl-CoA. The increase with ATP alone was only 50%.

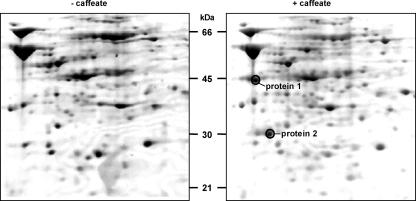

Identification of an electron transfer flavoprotein involved in caffeate reduction.

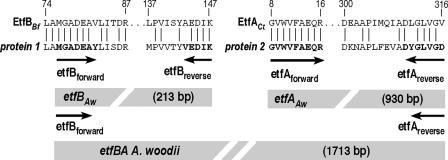

To identify proteins involved in caffeate reduction, cells were grown with fructose either in the absence or in the presence of caffeate, followed by comparison of the cellular protein contents by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. We focused on two proteins that were repeatedly found only in cells grown with fructose plus caffeate (Fig. 3). The proteins were excised from the gel and subjected to electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS), which yielded, among other sequences, the amino acid sequences GVWVFAEQR for peptide 1 and LAMGADEAYLISDR for peptide 2. BLAST searches revealed that peptide 1 is identical to a fragment of the α-subunit of an electron transfer flavoprotein (EtfA) of Clostridium tetani (amino acids 8 to 16), Clostridium beijerinckii, Clostridium saccharobutylicum, and Clostridium acetobutylicum, whereas peptide 2 is similar (with only two amino acid changes) to a fragment of the β-subunit of an electron transfer flavoprotein (EtfB) of Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens (amino acids 74 to 87), C. tetani, Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis, and Megasphera elsdenii. Therefore, proteins 1 and 2 were designated EtfA and EtfB. Two degenerate primers (etfAforward and etfBforward [Table 1]) were designed using the sequences for peptides 1 and 2, and the reverse primers were designed on the basis of additional sequence information obtained from the ESI-MS/MS analyses (Fig. 4). A PCR using these primers and chromosomal DNA of A. woodii gave DNA fragments that were 930 bp long for etfA and 213 bp long for etfB, sizes that were in the range one could expect from the peptide alignment shown in Fig. 4. The PCR fragments were cloned in the vector pCR 2.1-TOPO, and sequence analysis confirmed their identities.

FIG. 3.

Identification of proteins predominantly present in caffeate-grown cells by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Proteins were isolated from cells grown on fructose in the presence or absence of caffeate and were separated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis as described in Materials and Methods. Details from two representative Coomassie blue-stained gels are shown. Proteins 1 and 2 were excised from the gel and were analyzed by ESI-MS/MS.

FIG. 4.

Sequence alignment of peptides obtained from ESI-MS/MS analysis of caffeate-induced proteins 1 and 2 and cloning strategy for etfBA. Caffeate-induced proteins 1 and 2 were subjected to electrospray ionization-time of flight analysis. The peptides obtained were used for a BLAST search. Alignments of two peptides from protein 1 with EtfB from B. fibrisolvens (EtfBBf) and of two peptides from protein 2 with EtfA from C. tetani (EtfACt) are shown. Bold type indicates residues used to deduce the degenerate oligonucleotides etfBforward, etfBreverse, etfAforward, and etfAreverse.

In other organisms, etfA and etfB form a transcriptional unit, and etfB is the first gene in the cluster (4, 6, 9, 37). Southern blot analyses with etfA or etfB as the probe and chromosomal DNA of A. woodii as the target revealed one fragment that hybridized with both probes (data not shown). PCRs using primers etfBforward and etfAreverse (Table 1) yielded one 1,713-bp fragment, indicating that the genomic organization in A. woodii is 5′-etfB-etfA-3′. A comparison of the partial EtfAAw and EtfBAw proteins deduced from the 1,713-bp fragment with the corresponding proteins from various organisms suggested that about 75 N-terminal amino acids of EtfBAw are missing. etfB and etfA are separated by 15 bp. The EtfAAw gene starts with an ATG codon that is preceded by a well-placed (distance, 9 bp) Shine-Dalgarno sequence (AGGA). The sequence obtained for etfA encodes 379 amino acids, and multiple-sequence alignments revealed that only about 36 to 75 bp coding for C-terminal amino acids is missing in the fragment, depending on the species used for comparison (data not shown).

Properties of EtfA and EtfB of A. woodii deduced from the gene sequences.

Whereas EtfBs from different sources are similar to each other over the entire length of the proteins, EtfAs share similarities only in the C termini. EtfAAw is most similar to EtfA from Clostridium difficile (71% identity, 82% similarity), C. beijerinckii (58% identity, 75% similarity), and Geobacter metallireducens (49% identity, 64% similarity). EtfBAw is most similar to EtfB from C. difficile (60% identity, 76% similarity). Etf proteins are heterodimers of EtfA and EtfB and contain noncovalently bound flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD). The crystal structure of EtfA of Paracoccus denitrificans was solved, and the FAD binding site was identified in the structure in the conserved C terminus (44, 45). The Q240, V241, Q243, T244, Q263, and H264 residues that interact with the isoalloxazine ring of the FAD in P. denitrificans are fully conserved in EtfAAw. FAD's ribityl and ADP moiety is coordinated by 10 additional residues, 6 of which (S226, R227, S259, N278, K279, and D296) are also conserved in EtfAAw. EtfB contains the binding site for a second cofactor, AMP (44, 45). Two of the residues shown to be involved in AMP binding (G120 and A123 in P. denitrificans) are also conserved in EtfBAw. Two of the residues of EtfBPd are also involved in coordinating the isoalloxazine ring of the FAD (Y13 und F38). They are localized in the N terminus of EtfB that is missing in the fragment cloned. Taken together, these analyses clearly suggest that EtfAB of A. woodii is a flavoprotein.

EtfAw is induced by different phenylacrylates independent of the electron donor.

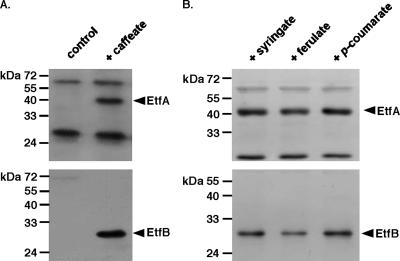

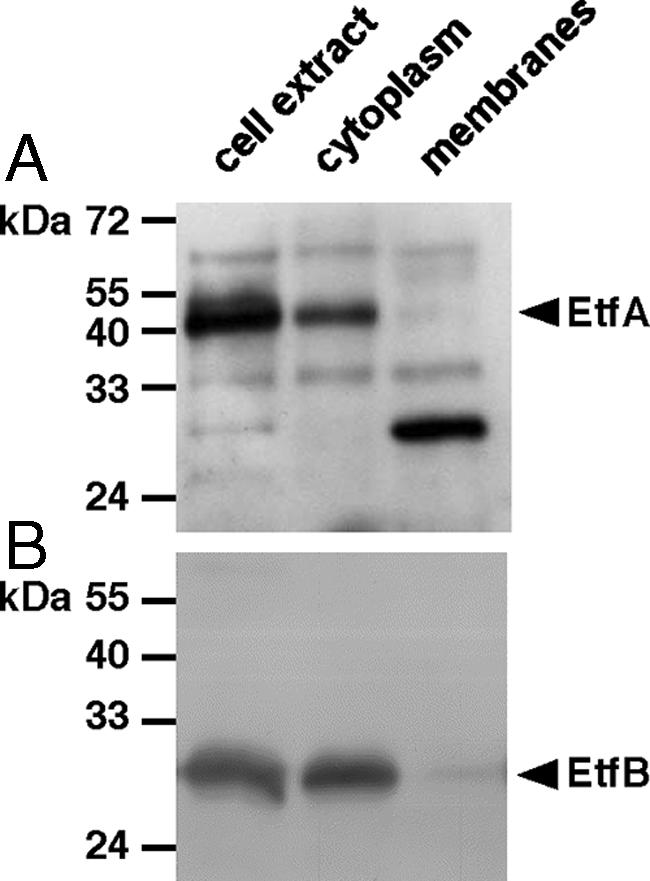

Antisera were raised against EtfA and EtfB heterologously produced in E. coli (see Materials and Methods), and Western blot analyses revealed that EtfAAw and EtfBAw were present only in cells that had been grown in the presence of caffeate, indicating that production of EtfAw is induced or derepressed by caffeate (Fig. 5). The apparent molecular masses of EtfAAw and EtfBAw were 45 and 29 kDa, respectively, which correspond to the masses of other Etf proteins. EtfAAw and EtfBAw were induced in the presence of ferulate (4-hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamate), p-coumarate (4-hydroxycinnamate), or syringate (4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzoate) but not by vanillate (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoate), hydrocaffeate, or fumarate (data not shown). Furthermore, EtfAAw and EtfBAw were present in cells grown in the presence of caffeate and fructose, H2-CO2, methanol, or formate as the electron donor, indicating that Etf has a central role in caffeate reduction (data not shown). Sequence analyses revealed no obvious membrane localization or membrane association of EtfAw, and Western blot analyses confirmed the exclusive localization of the proteins in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6).

FIG. 5.

Western blot analysis of EtfA and EtfB in A. woodii grown in the presence of various phenylacrylates. Lysates (25 μg protein) of cells grown on 20 mM fructose in the absence (control) or in the presence of 10 mM caffeate (A) or on 20 mM fructose and ferulate, syringate, or p-coumarate (10 mM each) (B) were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membranes, and probed with antisera against EtfA and EtfB.

FIG. 6.

EtfAAw (A) and EtfBAw (B) are localized in the cytoplasm. CFE was prepared and separated into membrane and cytoplasmic fractions as described in Material and Methods. Aliquots of each fraction (25 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membranes, and probed with antisera against EtfA and EtfB.

Caffeate reduction with NADH as the electron donor in the cytoplasmic fraction of A. woodii.

The presence and cytoplasmic localization of Etf suggest the possibility that caffeate reduction in A. woodii could be catalyzed by soluble proteins, including Etf as an electron mediator. NADH is used by some soluble, Etf-containing electron transport chains (22, 29, 37). To examine this possibility for caffeate reduction in A. woodii, CFE from cells of A. woodii grown on fructose plus caffeate was prepared. Upon addition of NADH to the CFE, caffeate reduction started immediately and proceeded at a rate of 24 nmol/min/mg protein. This rate was 60% of the rate observed for whole cells with hydrogen as the electron donor. As observed previously with H2 as the electron donor, caffeate reduction required activation by ATP. After separation of CFE into cytoplasmic and particulate fractions, the NADH:caffeate reductase activity was found exclusively in the cytoplasm. Alternative electron donors were assayed for the ability to reduce caffeate. N,N,N′,N′-tetraphenylendiamine, 1,5-diphenylcarbazid, and reduced methylviologen were not used as electron donors. In contrast, p-phenylenediamine reduced caffeate at a rate of 8 nmol/min/mg protein. Again, the activity was found exclusively in the cytoplasm (data not shown).

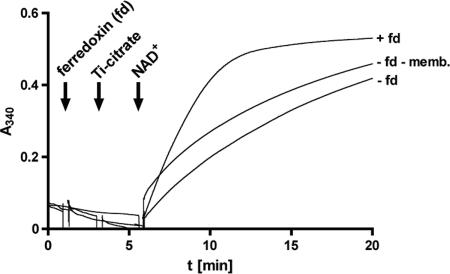

Membrane-bound ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase activity.

The remaining candidates for membrane localization and thus for the Na+-translocating enzyme were the enzymes involved in hydrogen-dependent NAD+ reduction. A. woodii was shown some time ago to have a ferredoxin-dependent, iron-only, oxygen-labile hydrogenase (42). We confirmed the cytosolic localization of the hydrogenase in A. woodii DSM 1030; 75 to 90% of the activity was found in the cytoplasm. Although the interpretation of these data is complicated since up to 80% of the activity was lost during fractionation of the CFE, the data argue against a role of hydrogenase in primary energy coupling. Therefore, we searched for an enzyme that could couple oxidation of reduced ferredoxin (generated by hydrogenase) with the reduction of NAD+. A potential candidate was an Rnf complex since this enzyme catalyzes the reduction of NAD+ by ferredoxin and, in addition, oxidation of NADH with artificial electron acceptors. In addition, oxidation of NADH with artificial electron acceptors is catalyzed (5, 28). Indeed, membranes of A. woodii catalyzed NADH oxidation with an activity of 86 or 74 U/mg using potassium hexacyanoferrate or benzylviologen as the acceptor. In the presence of O2, hydrogenase activity was completely inactivated, but NADH dehydrogenase was not affected. This rules out involvement of hydrogenase in the reaction observed. Next, we asked whether the membranes were able to catalyze ferredoxin-dependent NAD+ reduction. Therefore, we used ferredoxin from C. tetanomorphum that was reduced by Ti(III) citrate (58). Upon addition of reduced ferredoxin and NAD+, the latter was reduced by membranes of A. woodii at a rate of 91 nmol/min/mg protein. Ti(III) citrate also reduced NAD+ in the absence of ferredoxin and membranes, but at a much lower rate, 39 nmol/min/mg protein (Fig. 7). These data indicate that a ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase is present in membranes of A. woodii.

FIG. 7.

Ferredoxin-dependent NAD+ reduction. Aliquots (25 μl) of A. woodii membranes (27.5 mg protein/ml) were supplemented with 50 μl of ferredoxin (2 mg/ml). The ferredoxin was reduced with Ti(III) citrate before it was added to the membrane extract. The reaction was started by addition of 2.5 mM NAD+. Control reaction mixtures did not contain ferredoxin (fd) or lacked ferredoxin and membranes (memb.). The reduction was visualized at 340 nm using a photometer.

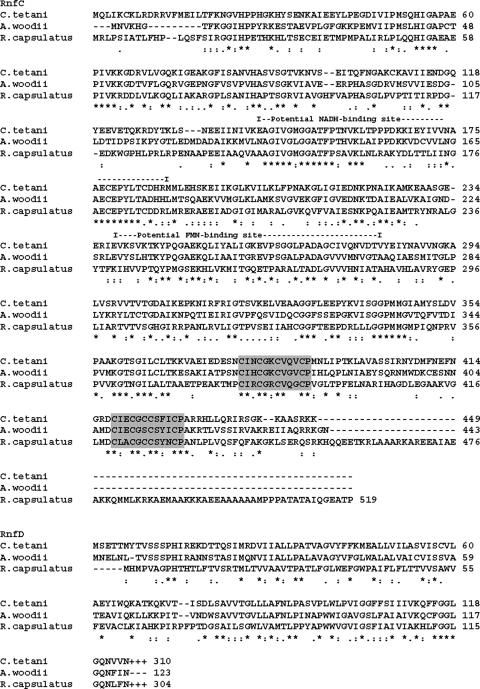

Amplification, sequence determination, and characterization of rnf genes from A. woodii.

Ferredoxin-dependent NAD+ reduction is, for example, catalyzed by the Rnf complex, a membrane-bound, presumably ion-translocating NADH dehydrogenase complex shown in recent years to be encoded by a number of genomes of prokaryotes. The Rnf complex first described in Rhodobacter capsulatus is encoded by six genes (48). Multiple-sequence analyses revealed conserved regions within rnfC.These regions were used to design heterologous primers with the aim of amplifying an rnfC homologue in A. woodii. Indeed, we were able to amplify a fragment of the expected size from chromosomal DNA of A. woodii with these primers. The sequence analyses revealed that the fragment indeed encodes part of an rnfC homologue. Inverse PCR was used to obtain further sequence information for the flanking regions of this fragment. Using this approach, we obtained sequence information for rnfC and rnfD from A. woodii.

The putative rnfC gene of A. woodii is 1,329 bp long and is preceded by a well-conserved Shine-Dalgarno sequence. Upstream of rnfC is a gene encoding a putative aminopeptidase. The derived amino acid sequence of rnfC is 57% identical to that of the corresponding protein of Clostridium sp. strain OhILAs and 50% identical to the corresponding protein of C. tetani. The deduced protein has a molecular mass of 47 kDa. Within the amino acid sequence of RnfC the consensus sequence C-XX-C-XX-C-XXX-C-P was found, indicating the presence of an Fe/S cluster binding site (Fig. 8) (18, 38). Furthermore, the amino acid sequence information indicates the presence of an NADH and FAD binding site (15, 56, 57). Three hundred ninety-seven base pairs downstream of rnfC were sequenced. This sequence codes for a peptide with similarity to the N terminus of RnfD. The derived amino acid sequence encoded by this partial rnfD gene is 61% identical to the sequence of the corresponding protein of Thermoanaerobacter ethanolicus and 55% identical to the sequence of the corresponding protein of C. tetani. Secondary structure predictions suggest that rnfD encodes a potential membrane protein, whereas rnfC is predicted to encode a soluble protein.

FIG. 8.

Sequence alignment of RnfC and RnfD: comparison of amino acid sequences of three RnfC homologs. An asterisk indicates complete conservation. The numbers on the right are amino acid positions. A minus sign indicates a gap introduced to increase similarity, and a plus sign indicates an additional sequence to follow. Consensus sequences for putative Fe/S binding sites are indicated by a gray background.

DISCUSSION

Here, we dissected the pathway of caffeate reduction in the Na+-dependent acetogen A. woodii. Electron transfer flavoproteins are widespread in nature and are found in archaea, bacteria, and eukarya (52). They are heterodimers consisting of a large α-subunit (EtfA) and a small β-subunit (EtfB) that contain noncovalently bound FAD. The general role of Etf proteins is to mediate electron flow between donor and acceptor pairs. Etf proteins are involved in fatty acid oxidation, where they funnel the electrons gained into the membrane-bound electron transport chain at the level of ubiquinone (16, 43). These proteins are found in eukarya and bacteria and are constitutively produced. In contrast, many bacteria, like A. woodii, induce Etfs only during special metabolic situations. Some examples are YaaQR, which is involved in the reduction of crotonobetainyl-CoA to γ-butyrobetainyl-CoA, a reaction involved in carnitine reduction in E. coli (14), and EtfAB of Methylophilus methylotrophus, in which EtfAB is produced along with a trimethylamine dehydrogenase (10, 51).

An interesting analog of the caffeate reduction catalyzed by A. woodii is found in some clostridia. In Clostridium propionicum the acryloyl-CoA reductase catalyzes the reduction of acryloyl-CoA to propionyl-CoA with electrons derived from NADH via Etf (22). The reductase and Etf constitute an enzyme complex. A very similar reaction is catalyzed by butyryl-CoA dehydrogenases involved in butyrate fermentation that also receive electrons from NADH via Etf (1, 6, 37). These enzymes belong to the class of acyl-CoA dehydrogenases. Based on the finding that there is ATP and acetyl-CoA stimulation of caffeate reduction, one may speculate that caffeate is also activated to caffeyl-CoA prior to its reduction.

From the data presented here it appears that the physiological electron donor of the still hypothetical caffeyl-CoA reductase of A. woodii is NADH. This can be assumed from the similarity of EtfAw to other Etfs, the known functions of Etfs, and the observed NADH:caffeate reductase activity. Etf could be the central electron input device for caffeate reduction with electrons derived from various donors (Fig. 9). A. woodii can couple the oxidation of various donors, such as hexoses, methyl group-containing compounds, or H2-CO2, with caffeate reduction. Oxidation of hexoses generates NADH as well as reduced ferredoxin, and methyl group oxidation yields reduced pyridine nucleotides and probably ferredoxin (47, 55). Therefore, oxidation of these substrates can easily be coupled to caffeate reduction directly via NADH.

FIG. 9.

Hypothetical electron flow from various donors to the terminal acceptor caffeate. For an explanation, see the text. CM, cell membrane; FADH2, reduced flavin adenine dinucleotide.

In addition, ferredoxin is also produced in the pathways outlined above. Moreover, the hydrogenase of A. woodii is a soluble iron-only hydrogenase and uses ferredoxin as an electron acceptor (42). The obvious question then is how the electrons from ferredoxin are funneled to Etf. First, reduced ferredoxin could be used to reduce NAD+ by a soluble ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase, an enzyme commonly found in anaerobes (26, 27, 39). Second and most important, a membrane-bound, energy-conserving ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase could be present. Indeed, our data support the latter possibility, which links electron transport to vectorial ion translocation across the membrane. Oxidation of reduced ferredoxin with concomitant reduction of NAD+ has a free energy change of −20 kJ/mol, and this energy could be used to drive the electrogenic transport of Na+ out of the cell. An enzyme that could potentially catalyze such a reaction is the Rnf-type NADH dehydrogenase found recently in bacteria and archaea (5, 31). The Rnf complex of R. capsulatus is thought to contain six subunits (48). RnfA, RnfD, and RnfE are predicted to be transmembrane proteins, whereas RnfC is a soluble protein and RnfB and RnfG are predicted to be associated with the membrane (25). In Rnf complexes indications of flavin mononucleotide and NADH binding sites were found, as were motifs typical of [4Fe-4S]-type ferredoxin-like domains (30). Bioinformatic analyses revealed that Rnf and Na+-pumping NADH:quinone oxidoreductase (Nqr) complexes are similar (25), which leads to the idea that Rnf complexes could function as Na+ pumps as well. For C. tetani and C. tetanomorphum it has been suggested that oxidation of reduced ferredoxin catalyzed by the Rnf-type NADH dehydrogenase is coupled to vectorial Na+ transport across the membrane (5, 7). A. woodii contains at least homologues of rnfC and rnfD, indicating that a Rnf complex is present. This enzyme may be involved not only in caffeate reduction but also in carbonate reduction and may be the long-sought Na+ pump in acetogens. Biochemical and molecular analyses of this complex are under way.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

We are grateful to Bernhard Granvogl (Department für Biologie I, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München, Germany) for the ESI-MS/MS analyses.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 September 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asanuma, N., M. Ishiwata, T. Yoshii, M. Kikuchi, Y. Nishina, and T. Hino. 2005. Characterization and transcription of the genes involved in butyrate production in Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens type I and II strains. Curr. Microbiol. 51:91-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bache, R., and N. Pfennig. 1981. Selective isolation of Acetobacterium woodii on methoxylated aromatic acids and determination of growth yields. Arch. Microbiol. 130:255-261. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaty, P. S., and L. G. Ljungdahl. 1991. Growth of Clostridium thermoaceticum on methanol, ethanol or dimethylsulfoxide, abstr. K-131, p. 236. Abstr. 91st Annu. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 1991. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 4.Bedzyk, L. A., K. W. Escudero, R. E. Gill, K. J. Griffin, and F. E. Frerman. 1993. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the genes encoding subunits of Paracoccus denitrificans electron transfer flavoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 268:20211-20217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boiangiu, C. D., E. Jayamani, D. Brügel, G. Herrmann, J. Kim, L. Forzi, R. Hedderich, I. Vgenopoulou, A. J. Pierik, J. Steuber, and W. Buckel. 2005. Sodium ion pumps and hydrogen production in glutamate fermenting anaerobic bacteria. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 10:105-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boynton, Z. L., G. N. Bennet, and F. B. Rudolph. 1996. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of clustered genes encoding beta-hydroxybutyryl-coenzyme A (CoA) dehydrogenase, crotonase, and butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase from Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. J. Bacteriol. 178:3015-3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brüggemann, H., S. Bäumer, W. F. Fricke, A. Wiezer, H. Liesegang, I. Decker, C. Herzberg, R. Martinez-Arias, R. Merkl, A. Henne, and G. Gottschalk. 2003. The genome sequence of Clostridium tetani, the causative agent of tetanus disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1316-1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryant, M. P. 1972. Commentary on the Hungate technique for culture of anaerobic bacteria. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 25:1324-1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, D., and R. P. Swenson. 1994. Cloning, sequence analysis, and expression of the genes encoding the two subunits of the methylotrophic bacterium W3A1 electron transfer flavoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 269:32120-32130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson, V. L., M. Husain, and J. W. Neher. 1986. Electron transfer flavoprotein from Methylophilus methylotrophus: properties, comparison with other electron transfer flavoproteins, and regulation of expression by carbon source. J. Bacteriol. 166:812-817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorn, M., J. R. Andreesen, and G. Gottschalk. 1978. Fermentation of fumarate and l-malate by Clostridium formicoaceticum. J. Bacteriol. 133:26-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorn, M., J. R. Andreesen, and G. Gottschalk. 1978. Fumarate reductase of Clostridium formicoaceticum. A peripheral membrane protein. Arch. Microbiol. 119:7-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake, H. L., K. Küsel, and C. Matthies. 2006. Acetogenic prokaryotes, p. 354-420. In M. Dworkin, S. Falkow, E. Rosenberg, K.-H. Schleifer, and E. Stackebrandt (ed.), The prokaryotes, 3rd ed. Springer-Verlag, New York, NY.

- 14.Eichler, K., A. Buchet, F. Bourgis, H. P. Kleber, and M. A. Mandrand-Berthelot. 1995. The fix Escherichia coli region contains four genes related to carnitine metabolism. J. Basic Microbiol. 35:217-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fearnley, I. M., and J. E. Walker. 1992. Conservation of sequences of subunits of mitochondrial complex I and their relationships with other proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1140:105-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frerman, F. E. 1987. Reaction of electron-transfer flavoprotein ubiquinone oxidoreductase with the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 893:161-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fröstl, J. M., C. Seifritz, and H. L. Drake. 1996. Effect of nitrate on the autotrophic metabolism of the acetogens Clostridium thermoautotrophicum and Clostridium thermoaceticum. J. Bacteriol. 178:4597-4603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.George, D. G., L. T. Hunt, L. S. Yeh, and W. C. Barker. 1985. New perspectives on bacterial ferredoxin evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 22:20-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansen, B., M. Bokranz, P. Schönheit, and A. Kröger. 1988. ATP formation coupled to caffeate reduction by H2 in Acetobacterium woodii NZva16. Arch. Microbiol. 150:447-451. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Härtel, U., and W. Buckel. 1996. Fermentation of trans-aconitate via citrate, oxaloacetate, and pyruvate by Acidaminococcus fermentans. Arch. Microbiol. 166:342-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hetzel, M., M. Brock, T. Selmer, A. J. Pierik, B. T. Golding, and W. Buckel. 2003. Acryloyl-CoA reductase from Clostridium propionicum. An enzyme complex of propionyl-CoA dehydrogenase and electron-transferring flavoprotein. Eur. J. Biochem. 270:902-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hungate, R. E. 1969. A roll tube method for cultivation of strict anaerobes. Methods Microbiol. 3b:117-132. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imkamp, F., and V. Müller. 2002. Chemiosmotic energy conservation with Na+ as the coupling ion during hydrogen-dependent caffeate reduction by Acetobacterium woodii. J. Bacteriol. 184:1947-1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jouanneau, Y., H. S. Jeong, N. Hugo, C. Meyer, and J. C. Willison. 1998. Overexpression in Escherichia coli of the rnf genes from Rhodobacter capsulatus—characterization of two membrane-bound iron-sulfur proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 251:54-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jungermann, K., G. Leimenstoll, E. Rupprecht, and R. K. Thauer. 1971. Demonstration of NADH-ferredoxin reductase in two saccharolytic clostridia. Arch. Microbiol. 80:370-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jungermann, K., E. Rupprecht, C. Ohrloff, R. K. Thauer, and K. Decker. 1971. Regulation of the reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-ferredoxin reductase system in Clostridium kluyveri. J. Biol. Chem. 246:960-963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim, J., M. Hetzel, C. D. Boiangiu, and W. Buckel. 2004. Dehydration of (R)-2-hydroxyacyl-CoA to enoyl-CoA in the fermentation of alpha-amino acids by anaerobic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28:455-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Komuniecki, R., J. McCrury, J. Thissen, and N. Rubin. 1989. Electron-transfer flavoprotein from anaerobic Ascaris suum mitochondria and its role in NADH-dependent 2-methyl branched-chain enoyl-CoA reduction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 975:127-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumagai, H., T. Fujiwara, H. Matsubara, and K. Saeki. 1997. Membrane localization, topology, and mutual stabilization of the rnfABC gene products in Rhodobacter capsulatus and implications for a new family of energy-coupling NADH oxidoreductases. Biochemistry 36:5509-5521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li, Q., L. Li, T. Rejtar, D. J. Lessner, B. L. Karger, and J. G. Ferry. 2006. Electron transport in the pathway of acetate conversion to methane in the marine archaeon Methanosarcina acetivorans. J. Bacteriol. 188:702-710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ljungdahl, L. G. 1994. The acetyl-CoA pathway and the chemiosmotic generation of ATP during acetogenesis, p. 63-87. In H. L. Drake (ed.), Acetogenesis. Chapman & Hall, New York, NY.

- 33.Ljungdahl, L. G. 1986. The autotrophic pathway of acetate synthesis in acetogenic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 40:415-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowry, O. H., N. J. Rosebrough, A. L. Farr, and R. J. Randall. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matthies, C., A. Freiberger, and H. L. Drake. 1993. Fumarate dissimilation and differential reductant flow by Clostridium formicoaceticum and Clostridium aceticum. Arch. Microbiol. 160:273-278. [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Farrell, P. H. 1975. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 250:4007-4021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Neill, H., S. G. Mayhew, and G. Butler. 1998. Cloning and analysis of the genes for a novel electron-transferring flavoprotein from Megasphaera elsdenii. Expression and characterization of the recombinant protein. J. Biol. Chem. 273:21015-21024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Otaka, E., and T. Ooi. 1987. Examination of protein sequence homologies. IV. Twenty-seven bacterial ferredoxins. J. Mol. Evol. 26:257-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petitdemange, H., C. Cherrier, R. Raval, and R. Gay. 1976. Regulation of the NADH and NADPH-ferredoxin oxidoreductases in clostridia of the butyric group. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 421:334-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ragsdale, S. W. 1997. The eastern and western branches of the Wood/Ljungdahl pathway: how the east and west were won. Biofactors 6:3-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ragsdale, S. W. 1992. Enzymology of the acetyl-CoA pathway of autotrophic CO2 fixation. Crit. Rev. Biochem. 26:261-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ragsdale, S. W., and L. G. Ljungdahl. 1984. Hydrogenase from Acetobacterium woodii. Arch. Microbiol. 139:361-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramsay, R. R., D. J. Steenkamp, and M. Husain. 1987. Reactions of electron-transfer flavoprotein and electron-transfer flavoprotein: ubiquinone oxidoreductase. Biochem. J. 241:883-892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberts, D. L., F. E. Frerman, and J. J. Kim. 1996. Three-dimensional structure of human electron transfer flavoprotein to 2.1-A resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:14355-14360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roberts, D. L., D. Salazar, J. P. Fulmer, F. E. Frerman, and J. J. Kim. 1999. Crystal structure of Paracoccus denitrificans electron transfer flavoprotein: structural and electrostatic analysis of a conserved flavin binding domain. Biochemistry 38:1977-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schägger, H., and G. von Jagow. 1987. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166:369-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scherer, P. A., and R. K. Thauer. 1978. Purification and properties of reduced ferredoxin: CO2 oxidoreductase from Clostridium pasteurianum, a molybdenum iron-sulfur-protein. Eur. J. Biochem. 85:125-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmehl, M., A. Jahn, A. Meyer zu Vilsendorf, S. Hennecke, B. Masepohl, M. Schuppler, M. Marxer, J. Oelze, and W. Klipp. 1993. Identification of a new class of nitrogen fixation genes in Rhodobacter capsulatus: a putative membrane complex involved in electron transport to nitrogenase. Mol. Gen. Genet. 241:602-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmidt, K., S. Liaanen-Jensen, and H. G. Schlegel. 1963. Die Carotinoide der Thiorodaceae. Arch. Mikrobiol. 46:117-126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seifritz, C., S. L. Daniel, A. Gossner, and H. L. Drake. 1993. Nitrate as a preferred electron sink for the acetogen Clostridium thermoaceticum. J. Bacteriol. 175:8008-8013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steenkamp, D. J., and J. Mallinson. 1976. Trimethylamine dehydrogenase from a methylotrophic bacterium. I. Isolation and steady-state kinetics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 429:705-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsai, M. H., and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1995. Phylogenetic characterization of the ubiquitous electron transfer flavoprotein families ETF-α and ETF-β. Res. Microbiol. 146:397-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tschech, A., and N. Pfennig. 1984. Growth yield increase linked to caffeate reduction in Acetobacterium woodii. Arch. Microbiol. 137:163-167. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weber, K., and M. Osborne. 1969. The reliability of the molecular weight determination by dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J. Biol. Chem. 244:4406-4412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wohlfarth, G., G. Geerligs, and G. Diekert. 1990. Purification and properties of a NADH-dependent 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase from Peptostreptococcus productus. Eur. J. Biochem. 192:411-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yagi, T. 1993. The bacterial energy-transducing NADH-quinone oxidoreductases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1141:1-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yagi, T., T. Yano, and A. Matsuno-Yagi. 1993. Characteristics of the energy-transducing NADH-quinone oxidoreductase of Paracoccus denitrificans as revealed by biochemical, biophysical, and molecular biological approaches. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 25:339-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zehnder, A. J., and K. Wuhrmann. 1976. Titanium(III) citrate as a nontoxic oxidation-reduction buffering system for the culture of obligate anaerobes. Science 194:1165-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]