Abstract

Monocytes and macrophages play a central role in the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated dementia. They represent prominent targets for HIV infection and are thought to facilitate viral neuroinvasion and neuroinflammatory processes. However, many aspects regarding monocyte brain recruitment in HIV infection remain undefined. The nonhuman primate model of AIDS is uniquely suited for examination of the role of monocytes in the pathogenesis of AIDS-associated encephalitis. Nevertheless, an approach to monitor cell migration from peripheral blood into the central nervous system (CNS) in primates had been lacking. Here, upon autologous transfer of fluorescein dye-labeled leukocytes, we demonstrate the trafficking of dye-positive monocytes into the choroid plexus stromata and perivascular spaces in the cerebra of rhesus macaques acutely infected with simian immunodeficiency virus between days 12 and 14 postinfection (p.i.). Dye-positive cells that had migrated expressed the monocyte activation marker CD16 and the macrophage marker CD68. Monocyte neuroinvasion coincided with the presence of the virus in brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid and with the induction of the proinflammatory mediators CXCL9/MIG and CCL2/MCP-1 in the CNS. Prior to neuroinfiltration, plasma viral load levels peaked on day 11 p.i. Furthermore, the numbers of peripheral blood monocytes rapidly increased between days 4 and 8 p.i., and circulating monocytes exhibited increased functional capacity to produce CCL2/MCP-1. Our findings demonstrate acute monocyte brain infiltration in an animal model of AIDS. Such studies facilitate future examinations of the migratory profile of CNS-homing monocytes, the role of monocytes in virus import into the brain, and the disruption of blood-cerebrospinal fluid and blood-brain barrier functions in primates.

As key mediators of innate immunity, monocytes provide the first line of defense against invading pathogens while also representing infection targets for monocyte-tropic pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes, cytomegalovirus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (20). During infection with HIV and its simian counterpart SIV in the primate animal model for AIDS, monocytes constitute a principal virus reservoir (13, 16, 31) and are thought to disseminate the virus into the brain (25, 51, 60). HIV and SIV enter the central nervous system (CNS) early in acute infection (8, 17, 33, 62), often resulting in the development of neurological complications and viral encephalitis late in the disease course with progression to AIDS (62). Initial entry of monocytes into the brain is thought to be facilitated by induction of proinflammatory mediators and chemokines that disrupt the blood-brain barrier (BBB) (21, 42) and the blood-cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) barrier. CCL2/monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, CXCL10/interferon-inducible protein 10, and other proinflammatory chemokines and CXCR3 ligands have been implicated in leukocyte brain recruitment in HIV and SIV infections (22, 40, 49, 59, 63) and are detectable at high levels in the CSF and brain tissue in HIV dementia cases and in macaques with SIV encephalitis (3, 7, 10, 14, 52). CCL2 in particular is an important chemokine involved in CNS inflammation (35, 57) and may serve as a predictor of CNS disease in SIV infection (37). Monocytes/macrophages are a major source of CCL2 and other proinflammatory proteins that recruit T cells and additional monocytes into the CNS (24, 53), trigger neuroinflammation (41), and promote neuronal cell death in HIV and SIV infections (27, 30). Nevertheless, to date, the dynamics of monocyte brain infiltration in primates and the role of monocytes as a “Trojan horse” for HIV and SIV entry into the CNS have not been directly defined (13), because leukocyte brain trafficking studies in a primate animal model have not been feasible.

Here we utilized a novel adoptive transfer approach in primates (11) to track fluorescein dye-labeled blood monocytes from the peripheral circulation into the CNS in SIV-infected rhesus macaques. We observed brain trafficking of fluorescein-labeled monocytes within a 48-h in vivo migratory period in acute SIV infection, which coincided with the presence of the virus in the CNS. SIV-infected cells and infiltrating monocytes/macrophages colocalized to the choroid plexus stroma and perivascular regions in the cerebrum, supporting the role of monocytes as a “Trojan horse” for virus entry into the brain. Preceding monocyte neuroinvasion, the number of peripheral blood monocytes increased dramatically, and the viral load as well as proinflammatory mediators reached peak levels in plasma. Furthermore, circulating monocytes exhibited a high capacity for CCL2 chemokine secretion and likely contributed to increased CCL2 levels following CNS entry. These combined events are thought to facilitate monocyte CNS trafficking and virus entry into the brain in acute SIV infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

SIV infection and autologous adoptive transfer of dye-labeled PBMC.

Three rhesus macaques (animals 29677, 30019, and 32222) were infected intravenously with pathogenic SIVmac251 (1,000 50% tissue culture infective doses in 1 ml). A total of four uninfected animals were included as negative controls in the adoptive transfer studies for analysis of CSF, plasma, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (11) (animals 30892, 30893, and 30880) and for examination of cerebral tissue sections (animals 30892, 30893, and 32971). Complete blood cell counts were monitored throughout the acute infection phase. The sequential phlebotomy procedure was conducted for isolation of a large number of PBMC as previously described (11, 12). In brief, on day zero for uninfected macaques or on day 12 postinfection (p.i.) for SIV-infected macaques, animals were sequentially bled and PBMC were isolated and dye labeled with 5 μM carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE) prior to autologous transfer of CFSE dye-labeled cells via the intravenous route (11, 12). The numbers of transferred CFSE dye-labeled monocytes in both animal groups (three SIV-infected and four uninfected macaques) ranged from 0.8 × 107 to 10 × 107 cells based on transfer of 2.1 ×108 to 7.4 ×108 total PBMC. Monocyte numbers were determined by flow cytometry by gating on forward- and side-scatter parameters and CD14 expression. Within 40 to 42 h after cell isolation and transfer (day 2 posttransfer for uninfected macaques and day 14 p.i. for SIV-infected macaques), animals were euthanized. After whole-body perfusion with 6 to 8 liters of saline, complete tissue collections were conducted. All experimental procedures were performed with prior approval by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee.

Intracellular chemokine staining by flow cytometry.

To examine CCL2 production, previously frozen PBMC from acutely SIV infected (animals 29677, 30019, and 32222) and uninfected control (22967, 34164, and 33583) macaques were defrosted in serum-free RPMI, washed, resuspended at 2 × 106 PBMC/ml of RPMI, and stimulated for 24 h in the presence of 10% rhesus serum and recombinant rhesus gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (10 ng/ml) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Monensin was added at a concentration of 2 μM during the last 6 h of stimulation to prevent chemokine secretion. Cells were first stained with an antibody directed against the monocyte surface marker CD14 (fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-human CD14 antibody, clone M5E2) prior to fixation, permeabilization, and subsequent intracellular staining with an antibody directed against CCL2 (phycoerythrin [PE]-conjugated anti-human CCL2 antibody, clone 5D3-F7) (reagents from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Sample data were acquired on a FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and data files were analyzed utilizing FlowJo software (TreeStar, Inc., Ashland OR).

Detection of SIV RNA in CSF and plasma by TaqMan analysis.

Viral RNA levels in plasma and CSF were determined by SIV real-time TaqMan PCR analysis based on amplification of a SIV gag gene-containing plasmid with established primer and probe pairs, as previously described (12, 34). Data are presented as viral RNA copies per milliliter of CSF or EDTA plasma.

Relative quantitation of chemokine transcription.

CXCL9 transcript levels of brain tissue were assessed using the comparative cycle threshold (CT) method (User Bulletin 2; Applied Biosystems) on a 7900 HTA FAST SDS real-time platform (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with previously established probes and procedures (11, 12). In brief, a coisolation procedure was used to extract total RNA and genomic DNA from 30-μm-thick paraffin-embedded cerebral tissue sections using the DNeasy tissue kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). For transcript analysis, total RNA was transcribed into first-strand cDNA using random hexamers. To increase the abundance of the target cDNA, real-time TaqMan PCR primers were used for the multiplex preamplification reaction, following validation of the PCR amplification efficiency of the preamplification reaction (4, 19). A standard curve was generated by plotting the preamplification cycle number against the CT value obtained for CXCL9. From the slope of this standard curve, the CXCL9 amplification efficiency was calculated based on the formula E = 10(1/−s) − 1. Values are reported as the fold difference relative to the lowest expressed transcript in non-SIV-infected control animals.

Absolute quantitation of SIV RNA in tissues.

For quantitation of SIV RNA in tissues, cDNA was preamplified and analyzed by SIV TaqMan PCR. The CT values were corrected with the CT values used for preamplification, including the SIV preamplification efficiency as a correction factor, and the resulting CT values were extrapolated onto the SIV RNA standard curve for absolute quantitation (34). To quantify the number of genome equivalents present within each PCR, genomic DNA samples were analyzed for the single-copy interleukin 2 gene by using an amount of sample equal to that used in the SIV TaqMan PCR. From this CT value, the genome equivalent was calculated and the cell number extrapolated before normalization of the SIV RNA content in each sample to 1 × 106 cells.

Detection of virus and proinflammatory mediators by protein ELISA.

SIV p27 protein levels in CSF were determined by a SIV p27 core antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA). CSF samples were incubated overnight on precoated plates prior to further processing. CXCL9, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and CCL2 protein levels in plasma and CSF were measured by an anti-human protein ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in triplicate wells, unless otherwise noted.

SIV RNA ISH.

In situ hybridization (ISH) for SIV RNA using 35S-UTP-labeled antisense riboprobes (including gag, pol, and env sequences) was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded choroid plexus and cerebral tissue sections (6 μm thick) as previously described (23, 47). Autoradiographic exposure times were extended to 14 days to increase the sensitivity of the assay and reveal all productively infected cells. Tissues were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin and mounted in Permount mounting medium (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Parallel analysis of SIV-infected and uninfected lymphoid tissue and sense riboprobe configurations confirmed the specificity of SIV RNA detection in the CNS.

Detection of dye-labeled monocytes/macrophages by immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence experiments were conducted as described previously (11, 12). In brief, heat-induced antigen retrieval in citrate buffer was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded 6-μm-thick tissue sections (55). The Dako Envision Doublestain system was used to visualize CFSE dye-labeled macrophages with antibodies directed against the fluorescein epitope of the transfer dye CFSE (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and the macrophage marker CD68 (clone KP1, Dako, Carpenteria, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP)-nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) and Fast Red were utilized as final substrates (Dako, Carpenteria, CA). A total of five nonadjacent cerebral tissue sections per animal were stained in double-labeling experiments, spanning at least 90 μm for each tissue. Slides were examined under bright-field microscopy, and the number of CD68+ CFSE dye-labeled cells was manually counted. For immunofluorescence experiments, choroid plexus tissue sections were first labeled with a rabbit anti-fluorescein antibody for indirect CFSE detection (11, 12) and with a mouse anti-human CD16 (clone 2H7; Novacastra, Newcastle, United Kingdom) or mouse anti-human CD68 (clone KP1) antibody for staining of macrophages. Tissue sections were subsequently labeled with an Alexa 488-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody for CFSE detection and an Alexa 568-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody for CD16 and CD68 (IgG antibodies from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Nuclear staining was performed with 4′,6′-diamidino-2′-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Statistics.

Repeated-measures analyses were performed to compare chemokine levels across infection status and tissue types. For flow cytometry experiments and examination of chemokine-producing cells, a Student t test was performed. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Induction of monocytes, plasma viral load, and chemokines in acute SIV infection.

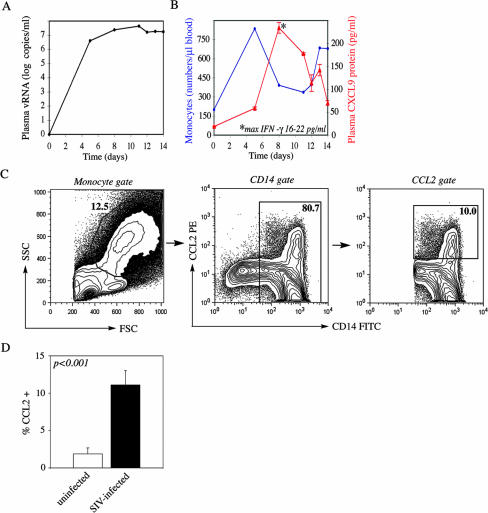

To examine innate monocyte responses in SIVmac251 infection with potential impact on monocyte neuroinvasion, we defined changes in peripheral blood monocyte numbers during the first 2 weeks p.i. We postulated that elevated numbers of monocytes and high plasma viral load levels between days 7 and 14 p.i. would heighten the chances for SIV-infected monocytes to invade the CNS, coinciding with the reported time frame of initial viral neuroinvasion (62). All three SIVmac251-infected macaques (animals 29677, 30019, and 32222) were productively infected. SIV RNA reached peak levels in plasma on day 11 p.i. in this animal group, with values ranging from 7.3 to 7.7 log10 viral RNA copies per ml (2.0 × 107 to 5.1 × 107 copies per ml), as shown here for representative animal 29677 (Fig. 1A). Importantly, blood monocyte levels increased rapidly in acute SIV infection, with the first monocyte peak occurring as early as day 4 or 5 p.i. in animals 29677 (Fig. 1B) and 30019 and day 8 in animal 32222. We expected the enhanced monocyte emigration into peripheral blood to be linked with monocyte activation and production of proinflammatory cytokines in the periphery. Indeed, the proinflammatory cytokine IFN-γ and the chemokine CXCL9 were rapidly induced in plasma in the SIV-infected group. Maximal secretion was reached on day 8 or 11 p.i., with average values ranging from 8 to 23 pg/ml and from 115 to 234 pg/ml for IFN-γ and CXCL9, respectively (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Induction of monocytes, plasma viral load, and chemokines in acute SIV infection. (A) Plasma viral loads in SIV-infected animals (animals 29677, 30019, and 32222) were measured by SIV RNA TaqMan analysis between days 0 and 14 p.i. Virus loads peaked on day 11 p.i. in all three animals (shown here for representative animal 29677). Data are expressed as log10 SIV RNA copies/ml. (B) Absolute peripheral blood monocyte numbers per microliter of blood were determined during the first 2 weeks p.i. (shown here for representative SIV-infected animal 29677). The production of the proinflammatory cytokine IFN-γ and the chemokine CXCL9 in plasma was measured by a protein ELISA in triplicate wells (blue, monocytes per microliter of blood; red, CXCL9; asterisks indicate the time point of maximal IFN-γ production and the concentration). (C) Peripheral blood monocytes derived from both animal groups (acutely SIV infected and uninfected macaques) were cultured for 24 h in the presence of rhesus IFN-γ and serum. Monensin was added during the last 6 h of stimulation prior to fixation, permeabilization, and cell staining. The gating strategy for flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood monocytes is illustrated for representative acutely SIV infected animal 29677. Monocytes were gated based on forward- and side-scatter parameters, excluding smaller lymphocytes and lymphocyte blasts. Monocytes were subsequently gated based on CD14 expression to determine the frequency of CCL2+ monocytes (right panel). (D) Bar graph represents a summary of CCL2 flow cytometry experiments and CCL2+ cell frequencies measured for all animals (in both the SIV-infected and uninfected groups; n = 3 for each group). Frequencies of CCL2+ monocytes are shown for monocytes gated based on size, granularity, and CD14 expression (as shown in panel C). A one-tailed, nonparametric Student t test was used to calculate the P value for differences between animal groups. (open bars, uninfected animals; solid bars; SIV-infected animals).

To examine the functional capacity of peripheral blood monocytes to produce the proinflammatory, IFN-inducible chemokine CCL2, which had previously been implicated in monocyte CNS trafficking (22, 35, 40, 63), CCL2 production was assayed in monocytes derived from acutely SIV infected macaques and uninfected control macaques following a 24-h stimulation in the presence of IFN-γ. Monensin was added during the last 6 h of activation to prevent chemokine secretion prior to staining and flow cytometry analysis. The gating strategy was based on forward- and side-scatter parameters and CD14 expression for determination of CCL2+ monocyte frequencies on day 14 p.i. (Fig. 1C). Upon stimulation, monocytes derived from SIV-infected animals had on average a >5-fold-higher capacity to produce the proinflammatory chemokine CCL2 than the uninfected group (Fig. 1D). Only 1.9% of CD14+ monocytes in the uninfected animals expressed CCL2, whereas this frequency reached on average 11.1% in SIV infection (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1D).

Production of proinflammatory mediators and monocyte chemoattractants in the CNS.

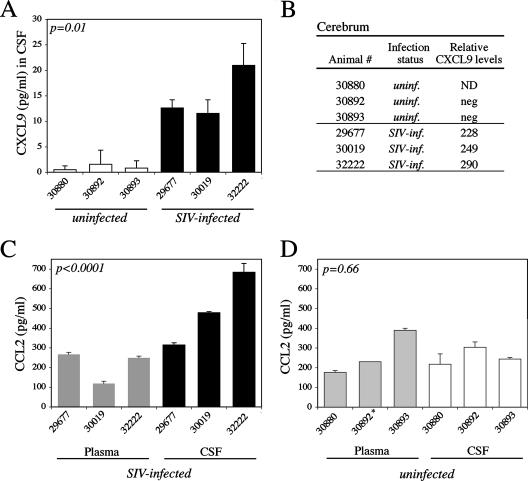

To examine if peripheral changes in acute SIV infection were associated with neuroinflammation and could contribute to monocyte as well as T-cell brain recruitment, we defined levels of representative proinflammatory protein and T-cell chemoattractant CXCL9 and of monocyte chemokine CCL2 in the CNS. CXCL9 levels were significantly higher in the CSF of SIV-infected macaques than in that of uninfected macaques (Fig. 2A), ranging from 12 to 21 pg/ml (compared to 0.5 to 1.6 pg/ml in SIV-uninfected macaques), although these levels were lower than those in plasma (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, CXCL9 was readily detected by TaqMan transcript analysis in the cerebra of SIV-infected macaques but was undetectable in the control group (Fig. 2B). CXCL9 induction in the CNS may promote cell activation and neuroinflammation in acute SIV infection.

FIG. 2.

Production of proinflammatory mediators in the CSF and cerebrum in acute SIV infection. (A) Proinflammatory chemokine CXCL9 levels were measured by an anti-human CXCL9 ELISA in the CSF of SIV-infected and uninfected animals at necropsy (day 14 p.i. for the SIV-infected group) in triplicate wells. CXCL9 levels were significantly higher in the CSF of acutely SIV infected animals (solid bars) than in the uninfected group (open bars) (P = 0.01 by unpaired repeated-measures analysis). (B) Relative transcript levels for proinflammatory CXCL9 were determined by RNA TaqMan PCR analysis in cerebral tissue sections of uninfected (animals 30892 and 30893) and acutely SIV infected (animals 29677, 30019, and 32222) macaques following RNA isolation from 30-μm-thick tissue sections and target gene-specific preamplification of cDNA. Transcript levels were normalized based on glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase transcription, and values were calibrated against the lowest expressed target gene in the uninfected group. ND, not determined; neg, negative (undetectable). (C) Monocyte chemoattractant CCL2 protein levels in plasma (shaded bars) and CSF (solid bars) were determined by an anti-human CCL2 ELISA on day 14 p.i. for the SIV-infected group. Values are expressed in picograms per milliliter and represent data from triplicate wells. CCL2 protein levels were significantly higher in CSF than in plasma for acutely SIV infected animals (P < 0.0001 by paired repeated-measures analysis). (D) Monocyte chemoattractant CCL2 protein levels were also measured in the plasma (shaded bars) and CSF (open bars) of uninfected animals by an anti-human CCL2 ELISA at necropsy. No significant differences in CCL2 levels between plasma and CSF were identified for the uninfected animal group (P = 0.66 by paired analysis). *, the CCL2 level in plasma for animal 30892 was measured from a single well only.

To examine if a CCL2 chemokine gradient from the periphery into the CNS was established to promote monocyte influx into the brain (36), CCL2 levels were determined in the CSF and plasma for both animal groups. We observed significantly higher levels of CCL2 in CSF than in plasma in SIV-infected animals (P < 0.0001 by paired analysis) (Fig. 2C), establishing a positive chemokine gradient toward the brain and a possible CNS recruitment signal for ligand-binding CCR2+ monocytes in acute SIV infection (36, 63). Average CCL2 levels for the SIV-infected group ranged from 314 to 684 pg/ml in CSF compared to 119 to 267 pg/ml in plasma on day 14 p.i. In contrast, no significant differences were detected between CCL2 levels in CSF and plasma for uninfected control macaques (P = 0.66 by paired analysis) (Fig. 2D). Average levels ranged from 217 to 304 pg/ml in CSF compared to 176 to 390 pg/ml in plasma. The difference in CCL2 levels in plasma between SIV-infected animals and uninfected control macaques was not statistically significant (Fig. 2C and D) (P = 0.55).

Presence of virus and infiltration of CFSE dye-labeled monocytes in the CNS in acute SIV infection.

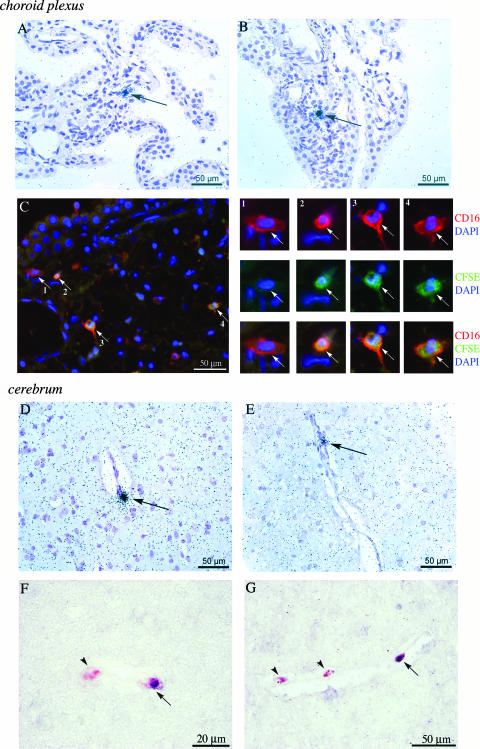

Based on maximal viral load levels in peripheral blood during the acute infection phase and previous reports of early viral entry into the brain (62), we anticipated that virus would be present in the CNS by day 14 post-SIVmac251 infection. Furthermore, the rise in levels of circulating, activated monocytes, together with high plasma viral load and induction of proinflammatory cytokines in the CNS, was expected to be linked with brain trafficking of activated and SIV-infected monocytes. Because the choroid plexus may represent a critical route for initial monocyte and virus entry into the CNS in HIV infection (9, 43), we first determined the presence of SIV RNA+ cells in this site. SIV RNA+ cells were readily detected by ISH and localized to the choroid plexus stroma (Fig. 3A and B). SIV was also present in the CSF, as determined by a SIV p27 protein ELISA and quantitative SIV RNA TaqMan analysis. SIV p27 levels in the CSF ranged from 93 to 226 pg/ml and SIV RNA copy numbers from 1.6 × 105 to 2.4 × 105 per ml CSF, levels similar to those previously reported in accelerated models of neuro-AIDS (6, 36, 37). The migration of adoptively transferred, CFSE dye-labeled monocytes from peripheral blood into the choroid plexus stroma was examined following a 2-day in vivo migratory period between days 12 and 14 p.i. (11, 12). Infiltration of dye-labeled cells into the choroid plexus stroma was observed in SIV-infected but not uninfected control macaques. In double-immunofluorescence experiments, CFSE dye-labeled cells costained with the monocyte activation marker CD16 (Fig. 3C [with enlarged view on the right]) or the macrophage marker CD68 (data not shown), which identified the infiltrating cells as activated monocytes/macrophages. Smaller CFSE dye-labeled cells, negative for both CD16 and CD68, were also identified; they likely represented infiltrating T lymphocytes (32, 38).

FIG. 3.

Detection of SIV RNA+ cells and infiltrating fluorescein dye-labeled monocytes in the choroid plexus and cerebrum. (A and B) SIV RNA+ cells (arrows) in SIV-infected animals were detected on day 14 p.i. by ISH of choroid plexus tissue sections using 35S-UTP-labeled riboprobes for SIV gag, pol, and env sequences (shown here for representative animals 29677 [A]and 30019 [B]). Tissue sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. (C) Infiltrating CFSE dye-labeled monocytes/macrophages in the choroid plexus were identified by double-immunofluorescence approaches with antibodies directed against CFSE (fluorescein epitope; indirect detection) and CD16. Secondary detection was performed with Alexa 488-conjugated (fluorescein; green) and Alexa 568-conjugated (CD16; red) antibodies, and sections were stained with the nuclear dye DAPI (blue). Enlarged views are shown on the right. A CD16 single-positive cell (enlarged view, panel 1, arrow) was observed along with several examples of CFSE dye-labeled CD16+ double-positive cells (enlarged view, panels 2 to 4, arrows) (shown here for animal 30019; top and center rows, single-color staining with DAPI; bottom row, triple-color overlay). (D and E) SIV RNA+ cells were identified in cerebral tissue sections by ISH utilizing methods identical to those for SIV detection in the choroid plexus (A and B). SIV RNA+ cells were observed near vessels in the gray matter of the cerebral cortex in representative SIV-infected animals 32222 (D) and 29677 (E). (F and G) Infiltrating CFSE dye-labeled monocytes/macrophages were identified in cerebral tissue sections from acutely SIV infected animals using double immunohistochemistry, shown here for representative SIV-infected animals 32222 (F) and 29677 (G). CFSE dye-labeled cells (dark purple) were visualized using BCIP-NBT substrate, and CD68 (red) was visualized with Fast Red substrate. To enhance the visibility of both substrates in double-positive cells, no counterstain was used on cerebral tissue sections. Arrowheads, CD68 single-positive cells; arrows, double-positive (CFSE dye-labeled, CD68+) cells.

To determine if circulating monocytes had crossed the BBB and if viral neuroinvasion had occurred in acute SIV infection, cerebral tissue sections were examined for the presence of viral RNA and CFSE dye-labeled monocyte infiltrates on day 14 p.i. Viral brain entry in the cerebrum was determined by SIV RNA detection using both quantitative viral RNA TaqMan analysis and ISH techniques. The SIV RNA copy number in the cerebrum was low but detectable in the SIV-infected group, ranging from 118 to 686 copies per 106 cells, whereas no RNA was detected in the uninfected control macaques. Isolated SIV-infected cells were identified in cerebral tissue from all three animals. SIV+ cells localized to vessels in the gray matter of the cerebral cortex (Fig. 3D and E), with as many as 6 SIV RNA+ cells identified per cerebral tissue section. Concomitantly with detection of productively infected cells, we also identified CFSE dye-labeled monocytes/macrophages that had entered the cerebrum between days 12 and 14 p.i., following autologous intravenous transfer. These cells had crossed the tight junctions of the BBB and localized to the perivascular space in the gray matter of the cerebral cortex, a localization similar to that of SIV+ cells (Fig. 3F and G). Infiltrating CFSE dye-labeled cells expressed macrophage marker CD68 in colabeling experiments for CD68 and CFSE by immunohistochemistry (shown for representative SIV-infected animals 32222 and 29677 in Fig. 3F and G, respectively). Only rare CD68+ CFSE dye-labeled cells were identified during this 40- to 42-h in vivo migratory period between the time of transfer (day 12 p.i.) and the time of necropsy (day 14 p.i.). An average of 1 to 2 CFSE dye-labeled CD68+ cells were observed on each tissue section in acute SIV infection, based on examination of five nonadjacent slides from each SIV-infected macaque. None were detected in two uninfected control macaques (animals 30893 and 32971). Less than one CD68+ CFSE dye-labeled cell per slide was identified in cerebral tissue sections of uninfected macaque 30892. The SIV infection status of CFSE dye-labeled monocytes/macrophages in the CNS was not directly examined in this study, given the rarity of SIV RNA+ and CFSE dye-labeled cells along with limited tissue availability. Nevertheless, the SIV RNA+ cells and CFSE dye-labeled monocytes/macrophages localized to the same anatomical regions in the choroid plexus and cerebrum, consistent with the proposed role of monocytes as a “Trojan horse” for viral entry into the brain (25, 51, 60, 62).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate the trafficking of dye-labeled monocytes into the CNS in acute SIV infection by utilizing a novel in vivo leukocyte trafficking model in primates (11). Infiltrating, dye-labeled monocytes/macrophages were observed in distinct brain regions and expressed macrophage marker CD68 and surface receptor CD16. Monocyte differentiation or activation marker CD16 may be expressed on circulating monocytes prior to CNS recruitment or, alternatively, upregulated upon or after brain entry. An expansion of circulating CD14+ CD16+ monocytes had previously been reported in both HIV and SIV infections (5, 56, 61), and high numbers of CD14+ CD16+ monocytes in peripheral blood correlated with an increased incidence of HIV dementia (44). These data support the notion that CD16 is expressed on the surfaces of activated blood monocytes in the periphery prior to CNS infiltration. CD16+ CFSE dye-labeled monocytes/macrophages were also observed in the spleen and lymph nodes (data not shown), suggesting that CD16+ circulating monocytes are not exclusively neuroinvasive.

Monocytes and other leukocytes are thought to traffic into the CNS via two major routes: through the tight junctions of the BBB or across the choroid plexus epithelium at the blood-CSF barrier (57). In this study, both CFSE dye-labeled monocytes/macrophages and SIV RNA+ cells were identified in the choroid plexus stroma in acute infection. CFSE dye-labeled cells had entered into the choroid plexus stroma and crossed the fenestrated microvascular endothelium, which is more permeable to extravasating cells than the tight junctions of the blood-CSF barrier (46). However, this finding may be important, because the choroid plexus is considered a critical route for initial CNS invasion by activated or infected monocytes in HIV infection, both temporally and spatially (9, 43). Rare CFSE dye-labeled macrophages were also identified in the perivascular space of the cerebrum in acutely SIV infected animals, indicating that cells had migrated across the BBB. Cells crossed the tight junctions at the vessel epithelium and basal lamina and exclusively localized to the perivascular space. In this study, SIV-infected cells and infiltrating monocytes colocalized to the perivascular regions in the cerebral cortex, further supporting the proposed role of monocytes in virus import into the CNS (25, 51, 60, 62).

Prior to monocyte neuroinvasion, changes occurred in the peripheral blood of acutely SIV infected animals that may have contributed to monocyte and virus entry into the CNS. Absolute peripheral blood monocyte numbers increased rapidly between days 4 and 8 p.i. A rise in the relative frequency of monocytes in cynomolgus monkeys (39) and in absolute numbers of monocytes in pig-tailed macaques had been reported in acute SIV infection (29, 58). Elevated numbers of monocytes likely reflected enhanced emigration from bone marrow during acute viral infection, a process similarly observed in mice upon bacterial infection during the innate immune response to Listeria (54). In HIV-infected patients, defining changes in the monocyte pool early during infection is not readily feasible, although a greater role for bone marrow hematopoiesis and increased monocyte output with a possible effect on monocyte CNS trafficking has been proposed for humans as well (26, 27, 45).

In addition to monocyte expansion, peripheral immune activation is thought to play a prominent role in promoting CNS invasion in HIV infection (25, 27). Peripheral blood monocytes from acutely SIV infected animals exhibited a significantly higher capacity to produce CCL2 than uninfected controls, suggesting differences in the functionality of circulating monocytes in acute SIV infection. This is in agreement with a previous observation that CCL2 levels were considerably higher, on average >10- to 15-fold, in the supernatants of cultured CD16+ monocytes from HIV-positive patients with AIDS than in those derived from non-HIV-infected individuals (1), although CD16+ monocytes were thought to constitutively produce CCL2 based on a comparison with CD16-negative monocytes (1). Our data are also consistent with CCL2 secretion by cultured macrophages upon viral infection and activation in vitro (24, 28).

The intracellular CCL2 chemokine production upon stimulation and high CCL2 levels in CSF in SIV infection suggest that monocyte movement into tissues and further differentiation/activation maybe required for CCL2 production in vivo. This may occur at the BBB through interaction with CX3CL1 on endothelial cells (2), consistent with the observed CX3CL1 expression at the BBB in SIV infection (18) or following movement into brain tissue and exposure to inflammatory stimuli (15, 48, 52). CNS-infiltrating monocytes likely secrete CCL2 and contribute to a proinflammatory environment, which enhances monocyte recruitment in an autocrine fashion upon establishment of a CCL2 chemokine gradient across the blood-CSF barrier and BBB in acute SIV infection (24, 36, 62, 63). In addition, resident CNS cells, including astrocytes, microglia, and endothelial cells, secrete proinflammatory mediators and likely contributed to the observed chemokine induction (2, 3, 14, 50, 52, 59).

Here we unambiguously demonstrate monocyte migration from the peripheral cell pool into the CNS within a 48-h in vivo migratory period in acute SIV infection, thereby providing insight regarding kinetic measures of cell migration into the brain. Furthermore, only limited knowledge is available regarding the extent of normal or homeostatic cell trafficking to the noninflamed CNS, the permeability of the BBB, and the accessibility of the choroid plexus in healthy primates. This study provides new avenues to explore such questions and to further dissect the role of monocytes in neuroinflammation and viral neuroinvasion in the nonhuman primate model for AIDS.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Joseph Mankowski and Don Canfield for critical feedback and to Danielle Harvey for statistical analysis. We also thank the Animal and Clinical Laboratory Services at the California National Primate Research Center for dedicated support, Kamaljeet Badwal Singh for technical help, and Christian Leutenegger and the Lucy Whittier Molecular and Diagnostic Core Facility for TaqMan analysis.

This work was supported in part by grants from the UC Davis Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine (to C.C.C. and U.E.), the Universitywide AIDS Research Program of the State of California (ID01-D-130 to U.E. and D05-D-406 to C.C.C.), NIH grant R21MH074383 (to U.E.), NIH grant F31NS055654 (to C.C.C.), and the NIH T32 Infectious Disease training program (T32AI060555). This project also used in part resources allocated to the California National Primate Research Center (NIH grant RR00169).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 August 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ancuta, P., P. Autissier, A. Wurcel, T. Zaman, D. Stone, and D. Gabuzda. 2006. CD16+ monocyte-derived macrophages activate resting T cells for HIV infection by producing CCR3 and CCR4 ligands. J. Immunol. 176:5760-5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ancuta, P., J. Wang, and D. Gabuzda. 2006. CD16+ monocytes produce IL-6, CCL2, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 upon interaction with CX3CL1-expressing endothelial cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 80:1156-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asensio, V. C., J. Maier, R. Milner, K. Boztug, C. Kincaid, M. Moulard, C. Phillipson, K. Lindsley, T. Krucker, H. S. Fox, and I. L. Campbell. 2001. Interferon-independent, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120-mediated induction of CXCL10/IP-10 gene expression by astrocytes in vivo and in vitro. J. Virol. 75:7067-7077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumgarth, N., R. Szubin, G. M. Dolganov, M. R. Watnik, D. Greenspan, M. Da Costa, J. M. Palefsky, R. Jordan, M. Roederer, and J. S. Greenspan. 2004. Highly tissue substructure-specific effects of human papilloma virus in mucosa of HIV-infected patients revealed by laser-dissection microscopy-assisted gene expression profiling. Am. J. Pathol. 165:707-718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bissel, S. J., G. Wang, A. M. Trichel, M. Murphey-Corb, and C. A. Wiley. 2006. Longitudinal analysis of activation markers on monocyte subsets during the development of simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. J. Neuroimmunol. 177:85-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bissel, S. J., G. Wang, A. M. Trichel, M. Murphey-Corb, and C. A. Wiley. 2006. Longitudinal analysis of monocyte/macrophage infection in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected, CD8+ T-cell-depleted macaques that develop lentiviral encephalitis. Am. J. Pathol. 168:1553-1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buch, S., Y. Sui, N. Dhillon, R. Potula, C. Zien, D. Pinson, S. Li, S. Dhillon, B. Nicolay, A. Sidelnik, C. Li, T. Villinger, K. Bisarriya, and O. Narayan. 2004. Investigations on four host response factors whose expression is enhanced in X4 SHIV encephalitis. J. Neuroimmunol. 157:71-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakrabarti, L., M. Hurtrel, M. A. Maire, R. Vazeux, D. Dormont, L. Montagnier, and B. Hurtrel. 1991. Early viral replication in the brain of SIV-infected rhesus monkeys. Am. J. Pathol. 139:1273-1280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, H., C. Wood, and C. K. Petito. 2000. Comparisons of HIV-1 viral sequences in brain, choroid plexus and spleen: potential role of choroid plexus in the pathogenesis of HIV encephalitis. J. Neurovirol. 6:498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cinque, P., A. Bestetti, R. Marenzi, S. Sala, M. Gisslen, L. Hagberg, and R. W. Price. 2005. Cerebrospinal fluid interferon-gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10, CXCL10) in HIV-1 infection. J. Neuroimmunol. 168:154-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clay, C. C., D. S. Rodrigues, L. L. Brignolo, A. Spinner, R. P. Tarara, C. G. Plopper, C. M. Leutenegger, and U. Esser. 2004. Chemokine networks and in vivo T-lymphocyte trafficking in nonhuman primates. J. Immunol. Methods 293:23-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clay, C. C., D. S. Rodrigues, D. J. Harvey, C. M. Leutenegger, and U. Esser. 2005. Distinct chemokine triggers and in vivo migratory paths of fluorescein dye-labeled T lymphocytes in acutely simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac251-infected and uninfected macaques. J. Virol. 79:13759-13768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collman, R. G., C. F. Perno, S. M. Crowe, M. Stevenson, and L. J. Montaner. 2003. HIV and cells of macrophage/dendritic lineage and other non-T cell reservoirs: new answers yield new questions. J. Leukoc. Biol. 74:631-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conant, K., A. Garzino-Demo, A. Nath, J. C. McArthur, W. Halliday, C. Power, R. C. Gallo, and E. O. Major. 1998. Induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in HIV-1 Tat-stimulated astrocytes and elevation in AIDS dementia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3117-3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cotter, R., C. Williams, L. Ryan, D. Erichsen, A. Lopez, H. Peng, and J. Zheng. 2002. Fractalkine (CX3CL1) and brain inflammation: implications for HIV-1-associated dementia. J. Neurovirol. 8:585-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crowe, S., T. Zhu, and W. A. Muller. 2003. The contribution of monocyte infection and trafficking to viral persistence, and maintenance of the viral reservoir in HIV infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 74:635-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis, L. E., B. L. Hjelle, V. E. Miller, D. L. Palmer, A. L. Llewellyn, T. L. Merlin, S. A. Young, R. G. Mills, W. Wachsman, and C. A. Wiley. 1992. Early viral brain invasion in iatrogenic human immunodeficiency virus infection. Neurology 42:1736-1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Depboylu, C., L. E. Eiden, M. K. Schafer, T. A. Reinhart, H. Mitsuya, T. J. Schall, and E. Weihe. 2006. Fractalkine expression in the rhesus monkey brain during lentivirus infection and its control by 6-chloro-2′,3′-dideoxyguanosine. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 65:1170-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolganov, G. M., P. G. Woodruff, A. A. Novikov, Y. Zhang, R. E. Ferrando, R. Szubin, and J. V. Fahy. 2001. A novel method of gene transcript profiling in airway biopsy homogenates reveals increased expression of a Na+-K+-Cl− cotransporter (NKCC1) in asthmatic subjects. Genome Res. 11:1473-1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drevets, D. A., and P. J. Leenen. 2000. Leukocyte-facilitated entry of intracellular pathogens into the central nervous system. Microbes Infect. 2:1609-1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eugenin, E. A., and J. W. Berman. 2003. Chemokine-dependent mechanisms of leukocyte trafficking across a model of the blood-brain barrier. Methods 29:351-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eugenin, E. A., K. Osiecki, L. Lopez, H. Goldstein, T. M. Calderon, and J. W. Berman. 2006. CCL2/monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 mediates enhanced transmigration of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected leukocytes across the blood-brain barrier: a potential mechanism of HIV-CNS invasion and NeuroAIDS. J. Neurosci. 26:1098-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fallert, B. A., and T. A. Reinhart. 2002. Improved detection of simian immunodeficiency virus RNA by in situ hybridization in fixed tissue sections: combined effects of temperatures for tissue fixation and probe hybridization. J. Virol. Methods 99:23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fantuzzi, L., F. Belardelli, and S. Gessani. 2003. Monocyte/macrophage-derived CC chemokines and their modulation by HIV-1 and cytokines: a complex network of interactions influencing viral replication and AIDS pathogenesis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 74:719-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischer-Smith, T., and J. Rappaport. 2005. Evolving paradigms in the pathogenesis of HIV-1-associated dementia. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 7:1-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gartner, S. 2000. HIV infection and dementia. Science 287:602-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gartner, S., and Y. Liu. 2002. Insights into the role of immune activation in HIV neuropathogenesis. J. Neurovirol. 8:69-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hicks, A., R. Potula, Y. J. Sui, F. Villinger, D. Pinson, I. Adany, Z. Li, C. Long, P. Cheney, J. Marcario, F. Novembre, N. Mueller, A. Kumar, E. Major, O. Narayan, and S. Buch. 2002. Neuropathogenesis of lentiviral infection in macaques: roles of CXCR4 and CCR5 viruses and interleukin-4 in enhancing monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 production in macrophages. Am. J. Pathol. 161:813-822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Israel, Z. R., G. A. Dean, D. H. Maul, S. P. O'Neil, M. J. Dreitz, J. I. Mullins, P. N. Fultz, and E. A. Hoover. 1993. Early pathogenesis of disease caused by SIVsmmPBj14 molecular clone 1.9 in macaques. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 9:277-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaul, M., G. A. Garden, and S. A. Lipton. 2001. Pathways to neuronal injury and apoptosis in HIV-associated dementia. Nature 410:988-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim, W. K., S. Corey, X. Alvarez, and K. Williams. 2003. Monocyte/macrophage traffic in HIV and SIV encephalitis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 74:650-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lackner, A. A., M. O. Smith, R. J. Munn, D. J. Martfeld, M. B. Gardner, P. A. Marx, and S. Dandekar. 1991. Localization of simian immunodeficiency virus in the central nervous system of rhesus monkeys. Am. J. Pathol. 139:609-621. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lane, J. H., V. G. Sasseville, M. O. Smith, P. Vogel, D. R. Pauley, M. P. Heyes, and A. A. Lackner. 1996. Neuroinvasion by simian immunodeficiency virus coincides with increased numbers of perivascular macrophages/microglia and intrathecal immune activation. J. Neurovirol. 2:423-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leutenegger, C. M., J. Higgins, T. B. Matthews, A. F. Tarantal, P. A. Luciw, N. C. Pedersen, and T. W. North. 2001. Real-time TaqMan PCR as a specific and more sensitive alternative to the branched-chain DNA assay for quantitation of simian immunodeficiency virus RNA. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:243-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahad, D. J., and R. M. Ransohoff. 2003. The role of MCP-1 (CCL2) and CCR2 in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). Semin. Immunol. 15:23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mankowski, J. L., J. E. Clements, and M. C. Zink. 2002. Searching for clues: tracking the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus central nervous system disease by use of an accelerated, consistent simian immunodeficiency virus macaque model. J. Infect. Dis. 186(Suppl. 2):S199-S208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mankowski, J. L., S. E. Queen, J. E. Clements, and M. C. Zink. 2004. Cerebrospinal fluid markers that predict SIV CNS disease. J. Neuroimmunol. 157:66-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcondes, M. C., E. M. Burudi, S. Huitron-Resendiz, M. Sanchez-Alavez, D. Watry, M. Zandonatti, S. J. Henriksen, and H. S. Fox. 2001. Highly activated CD8+ T cells in the brain correlate with early central nervous system dysfunction in simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Immunol. 167:5429-5438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otani, I., H. Akari, K. H. Nam, K. Mori, E. Suzuki, H. Shibata, K. Doi, K. Terao, and Y. Yosikawa. 1998. Phenotypic changes in peripheral blood monocytes of cynomolgus monkeys acutely infected with simian immunodeficiency virus. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:1181-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Persidsky, Y. 1999. Model systems for studies of leukocyte migration across the blood-brain barrier. J. Neurovirol. 5:579-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Persidsky, Y., and H. E. Gendelman. 2003. Mononuclear phagocyte immunity and the neuropathogenesis of HIV-1 infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 74:691-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Persidsky, Y., J. Zheng, D. Miller, and H. E. Gendelman. 2000. Mononuclear phagocytes mediate blood-brain barrier compromise and neuronal injury during HIV-1-associated dementia. J. Leukoc. Biol. 68:413-422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petito, C. K., H. Chen, A. R. Mastri, J. Torres-Munoz, B. Roberts, and C. Wood. 1999. HIV infection of choroid plexus in AIDS and asymptomatic HIV-infected patients suggests that the choroid plexus may be a reservoir of productive infection. J. Neurovirol. 5:670-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pulliam, L., R. Gascon, M. Stubblebine, D. McGuire, and M. S. McGrath. 1997. Unique monocyte subset in patients with AIDS dementia. Lancet 349:692-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ragin, A. B., Y. Wu, P. Storey, B. A. Cohen, R. R. Edelman, L. G. Epstein, and S. Gartner. 2006. Bone marrow diffusion measures correlate with dementia severity in HIV patients. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 27:589-592. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ransohoff, R. M., P. Kivisakk, and G. Kidd. 2003. Three or more routes for leukocyte migration into the central nervous system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:569-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reinhart, T. A., B. A. Fallert, M. E. Pfeifer, S. Sanghavi, S. Capuano III, P. Rajakumar, M. Murphey-Corb, R. Day, C. L. Fuller, and T. M. Schaefer. 2002. Increased expression of the inflammatory chemokine CXC chemokine ligand 9/monokine induced by interferon-gamma in lymphoid tissues of rhesus macaques during simian immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Blood 99:3119-3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roberts, E. S., E. M. Burudi, C. Flynn, L. J. Madden, K. L. Roinick, D. D. Watry, M. A. Zandonatti, M. A. Taffe, and H. S. Fox. 2004. Acute SIV infection of the brain leads to upregulation of IL6 and interferon-regulated genes: expression patterns throughout disease progression and impact on neuroAIDS. J. Neuroimmunol. 157:81-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roberts, E. S., S. Huitron-Resendiz, M. A. Taffe, M. C. Marcondes, C. T. Flynn, C. M. Lanigan, J. A. Hammond, S. R. Head, S. J. Henriksen, and H. S. Fox. 2006. Host response and dysfunction in the CNS during chronic simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Neurosci. 26:4577-4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanders, V. J., C. A. Pittman, M. G. White, G. Wang, C. A. Wiley, and C. L. Achim. 1998. Chemokines and receptors in HIV encephalitis. AIDS 12:1021-1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sasseville, V. G., and A. A. Lackner. 1997. Neuropathogenesis of simian immunodeficiency virus infection in macaque monkeys. J. Neurovirol. 3:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sasseville, V. G., M. M. Smith, C. R. Mackay, D. R. Pauley, K. G. Mansfield, D. J. Ringler, and A. A. Lackner. 1996. Chemokine expression in simian immunodeficiency virus-induced AIDS encephalitis. Am. J. Pathol. 149:1459-1467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidtmayerova, H., H. S. Nottet, G. Nuovo, T. Raabe, C. R. Flanagan, L. Dubrovsky, H. E. Gendelman, A. Cerami, M. Bukrinsky, and B. Sherry. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection alters chemokine beta peptide expression in human monocytes: implications for recruitment of leukocytes into brain and lymph nodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:700-704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Serbina, N. V., and E. G. Pamer. 2006. Monocyte emigration from bone marrow during bacterial infection requires signals mediated by chemokine receptor CCR2. Nat. Immunol. 7:311-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tacha, D., and T. Chen. 1994. Modified antigen retrieval procedure: calibration techniques for microwave ovens. Histotechnology 17:365. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thieblemont, N., L. Weiss, H. M. Sadeghi, C. Estcourt, and N. Haeffner-Cavaillon. 1995. CD14low CD16high: a cytokine-producing monocyte subset which expands during human immunodeficiency virus infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 25:3418-3424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ubogu, E. E., M. B. Cossoy, and R. M. Ransohoff. 2006. The expression and function of chemokines involved in CNS inflammation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 27:48-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wachtman, L. M., P. M. Tarwater, S. E. Queen, R. J. Adams, and J. L. Mankowski. 2006. Platelet decline: an early predictive hematologic marker of simian immunodeficiency virus central nervous system disease. J. Neurovirol. 12:25-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weiss, J. M., S. A. Downie, W. D. Lyman, and J. W. Berman. 1998. Astrocyte-derived monocyte-chemoattractant protein-1 directs the transmigration of leukocytes across a model of the human blood-brain barrier. J. Immunol. 161:6896-6903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams, A. E., and W. F. Blakemore. 1990. Monocyte-mediated entry of pathogens into the central nervous system. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 16:377-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williams, K., S. Westmoreland, J. Greco, E. Ratai, M. Lentz, W. K. Kim, R. A. Fuller, J. P. Kim, P. Autissier, P. K. Sehgal, R. F. Schinazi, N. Bischofberger, M. Piatak, J. D. Lifson, E. Masliah, and R. G. Gonzalez. 2005. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy reveals that activated monocytes contribute to neuronal injury in SIV neuroAIDS. J. Clin. Investig. 115:2534-2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Williams, K. C., and W. F. Hickey. 2002. Central nervous system damage, monocytes and macrophages, and neurological disorders in AIDS. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 25:537-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zink, M. C., G. D. Coleman, J. L. Mankowski, R. J. Adams, P. M. Tarwater, K. Fox, and J. E. Clements. 2001. Increased macrophage chemoattractant protein-1 in cerebrospinal fluid precedes and predicts simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. J. Infect. Dis. 184:1015-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]