Abstract

A series of multivalent peptides with the ability to simultaneously bind two separate PDZ domain proteins has been designed, synthesized and tested by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). The monomer sequences, linked with succinate, varied in length from five to nine residues. The thermodynamic binding parameters, in conjunction with results from mass spectrometry, indicate that a ternary complex is formed in which each peptide arm binds two equivalents of the third PDZ domain (PDZ3) of the neuronal protein PSD-95.

Multivalency is a recurring theme in biological molecular recognition, and has, like many concepts appropriated from Nature, availed itself to an array of chemical applications.1 Exploiting multivalent character in the pursuit of cellular probes and therapeutic agents has preoccupied the thinking of chemists for awhile now, and for familiar reasons: to generate binding compounds with high affinity and enhanced selectivity for a given biomolecular receptor.2 In this current study, our objective is to invoke this design sensibility as we develop a new class of minimally-sized ligands to target the PDZ domain family of signaling proteins.

PDZ domains are ripe for investigating multivalency. Many mammalian proteins, particularly those situated at neuronal synapses, possess this domain, which is frequently present in multiple, albeit non-identical, copies. The result is a single polypeptide that can serve as a cellular hub for a variety of endogenous protein binding partners. Canvassing the biological consequences of PDZ domain multivalency is still a nascent research activity, but studies are beginning to appear. Two notable examples are those of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS)3 and the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein.4

The potential exists, then, to apply multivalent ligand design principles to the PDZ domain to further both biophysical and biological understanding. Our prior efforts have yielded monovalent linear5 and cyclic6 peptides that have provided insight into the thermodynamic nature of protein-ligand interactions. These have led to validation of a PDZ domain-directed molecular probe that functions within human cells.7 The added dimension of multivalency enhances the prospects for fashioning cell-permeable ligands that can selectively inhibit or uncouple PDZ domain-based assemblies, or—perhaps more intriguingly—can promote complex formation by co-localizing separate signaling proteins in vivo (as in (2) of Figure 1).

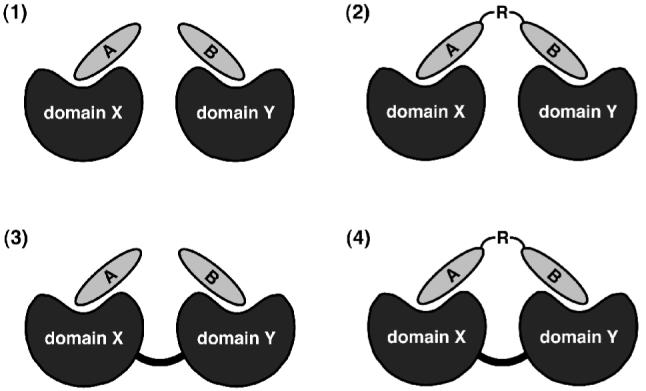

Figure 1.

Protein domain-ligand combinations for bivalent interactions.

As a simple and direct entry into this design challenge, we elected for a bivalent strategy. Figure 1 outlines the basic combinations involving a two-binding site architecture, from which we chose case (2), with a homobivalent peptide (A = B) and a single protein domain (X = Y). Bivalent peptides designed to recognize two discrete binding sites have been used to target important cellular proteins, including dual SH2-SH3 domain8 and SH2 domain-tyrosine kinase9 constructs, and G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs).10

The specific PDZ domain selected for this study was PDZ3, the third PDZ domain of the neuronal protein postsynaptic density-95 (PSD-95). PDZ3 is well characterized and has been the object of our prior ligand design efforts, which have demonstrated the facility with which PDZ3 can bind to relatively short stretches of peptide with dissociation constants in the low micromolar range.5,6 As with our previous work, the analytical method chosen was isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), a solution technique that provides not only the thermodynamic binding parameters (i.e., ΔG, ΔH and ΔS), but also the binding stoichiometry (n)— the ratio of ligand to host equivalents.11

To date the most thorough inquiries into binding multivalency using ITC have focused on protein-carbohydrate interactions.12 In the realm of protein-(poly)peptide interactions, calorimetric investigations have figured prominently in multivalent studies of the erythropoietin (EPO) receptor,13 the SH2 domain,14 and of heterobivalent peptides that bind both the SH2 and SH3 domains in an Abelson kinase construct.15 Although multivalency introduces additional complexity in binding analysis, there is ongoing calorimetric method development in the area.16 Multivalent ligand design principles in concert with calorimetry have only recently been applied to PDZ domains.17

As a compromise between simplicity, size, and synthetic convenience, we chose the diacid succinate as linker. We prepared a series of homobivalent peptides (Figure 2) based on the C-terminus of the protein CRIPT, from which an isolated hexapeptide (YKQTSV) was derived that we previously demonstrated to possess good affinity for PDZ3 (Kd = 0.8 μM).5b This series comprised peptides bearing five to nine residues of the CRIPT sequence (1-5).

Figure 2.

Structures of PDZ3-binding bivalent peptides.

Bivalent ligand preparation utilized standard Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis procedures (Scheme 1). The C-termini are resin-bound, leaving the amino termini of the completed sequences accessible for double coupling with succinate as the ultimate step before the final cleavage.18 An exposed C-terminus is required for peptide binding to most PDZ domains, which includes PDZ3; this is conveniently provided by TFA-induced global deprotection and release from resin to yield the bivalent peptide with free carboxylate ends.

Scheme 1.

Solid-phase peptide synthesis of homobivalent pentapeptide KQTSV (1). Peptides 2-5 were prepared in corresponding fashion.

Calorimetric binding analysis was performed in the same manner as our earlier work,5 with bivalent peptide solutions injected into the PDZ3 sample. The use of symmetric homobivalent ligands was intended to simplify the ensuing data interpretation, yet this form of multivalent interaction is still considerably more difficult to analyze than a standard 1:1 host-ligand titration. Binding of two PDZ3 would lead to a ternary complex, and an appropriate mathematical model with which to treat the calorimetric data is required. We applied each of three models: the One Set of Sites (OSS), the Sequential Binding Sites (SBS), and the Two Sets of Sites (TSS) models (each as implemented in the Origin program). In addition to assessing whether the assumptions of each model made biochemical sense, the chi-squared) (χ2) value was used as the primary criterion for the goodness of fit.

The OSS model assumes that only one binding event is taking place during an ITC experiment. Consequently, each of the multiple identical binding events would be reported as the same set of thermodynamic parameters, and the n value would be a positive integer equal to the multiplicity. Considering the homobivalent nature of the ligands used in this study, this model is appropriate and was applied to directly determine the stoichiometry of the interaction. The resulting data from OSS model fitting are shown in Table 1. The stoichiometries obtained from titrations with every one of the bivalent peptides equaled or closely approximated the value of two. This strongly supports a binding mode that involves two PDZ domains in association with a single bivalent ligand. Further evidence for the binding mode of the bivalent ligands to two PDZ domains came from a reverse ITC experiment. Here PDZ3 is injected into the sample cell containing ligand 2. The n = 1.8 obtained from this titration provides independent evidence that binding involves one equivalent of bivalent ligand to two PDZ3.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic binding parameters for CRIPT-derived homobivalent peptides and PDZ3 using the OSS model.a

| Compds | Kd (μM) | ΔG (kcal/mol) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | TΔS (kcal/mol) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23.2 (± 0.5) | -6.3 (± 0.1) | -6.4 (± 0.1) | -0.1 (± 0.1) | 2.0 (± 0.1) |

| 2 | 6.7 (± 0.1) | -7.1 (± 0.1) | -4.1 (± 0.1) | 3.0 (± 0.1) | 2.2 (± 0.1) |

| 3 | 6.6 (± 0.1) | -7.1 (± 0.1) | -5.3 (± 0.2) | 1.8 (± 0.2) | 2.0 (± 0.1) |

| 4 | 5.5 (± 0.2) | -7.2 (± 0.1) | -5.5 (± 0.2) | 1.7 (± 0.2) | 2.1 (± 0.1) |

| 5 | 4.3 (± 0.1) | -7.3 (± 0.1) | -5.7 (± 0.2) | 1.6 (± 0.2) | 2.1 (± 0.1) |

Values are the arithmetic mean of at least two independent experiments (error shown below each value reflects the range).

When viewing these thermodynamic binding parameters, it is apparent that enthalpy is the predominant contributor to the free energy of association. Within the series, the transition from five to six residues (1→2) marks the largest improvement in ΔG, which thereafter remains relatively constant as additional residues are added. This behavior has also been seen with the corresponding CRIPT ‘monovalent’ peptide series and PDZ3.5b It appears that six residues per strand is necessary and sufficient to capture the bulk of binding affinity for this bivalent peptide series, which was likewise the case with the monovalent ligands.

Since this type of binding system is not well documented, in order to avoid any bias in our analysis we also examined alternative fitting methods. The SBS model provided a good fit for the experimental data and with smaller χ2 values than observed with OSS treatment. The main assumption of the SBS model is that association is sequential and yields a data set in which the binding sites are allowed to vary. This model, however, does not furnish the stoichiometry of the interaction, so the n value determined from the OSS model was used for initialization. Lastly, we also applied the TSS model, but of the three fitting methods it produced the poorest curve fits and was not pursued further.

Table 2 presents the thermodynamic parameters for each of the two sites determined by SBS fitting. Here, the bivalent ligands bind with one high affinity and one lower affinity interaction. The difference in the binding strength for PDZ3 between the two sites varies from ten-fold with ligand 1 to as little as a 1.5-fold increase with ligand 5. There are no clear and prominent trends in the thermodynamic parameters, other than the enthalpically-driven nature of the associations. This, and the affinity improvement marking the pentapeptide to hexapeptide sequence transition are reminiscent of the results from the OSS data treatment.

Table 2.

Thermodynamic binding parameters for CRIPT-derived homobivalent peptides and PDZ3 using the SBS model.a

| 1st Binding Siteb | 2nd Binding Siteb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compds | Kd (μM) | ΔG (kcal/mol) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | TΔS (kcal/mol) | Kd (μM) | ΔG (kcal/mol) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | TΔS (kcal/mol) |

| 1 | 9.7 (±1.0) | -6.8 (±0.1) | -6.1 (±0.1) | 0.7 (±0.2) | 107 (±50) | -5.8 (±0.3) | -10.3 (±2.8) | -4.5 (±3.1) |

| 2 | 6.3 (±1.3) | -7.1 (±0.1) | -3.9 (±0.2) | 3.2 (±0.1) | 11.7 (±1.2) | -6.7 (±0.1) | -5.1 (±0.3) | 1.6 (±0.3) |

| 3 | 3.7 (±0.4) | -7.4 (±0.1) | -5.2 (±0.2) | 2.2 (±0.2) | 13.5 (±0. 8) | -6.7 (±0.1) | -5.7 (±0.4) | 1.0 (±0.4) |

| 4 | 5.0 (±1.7) | -7.3 (±0.2) | -5.5 (±0.1) | 1.8 (±0.3) | 9.2 (±0.6) | -6.9 (±0.1) | -5.6 (±0.7) | 1.3 (±0.6) |

| 5 | 5.8 (±3.3) | -7.3 (±0.4) | -5.3 (±0.4) | 2.0 (±0.1) | 8.6 (±1.1) | -6.9 (±0.1) | -7.2 (±0.4) | -0.3 (±0.4) |

Values are the arithmetic mean of at least two independent experiments (error shown beside each value reflects the range).

Ordinals do not necessarily reflect the order of binding.

If the values in Table 2 are biochemically meaningful, they do not, however, speak to the mechanism. This presumably proceeds through a stepwise process and not an entropically improbable event in which the three components assemble simultaneously. In a sequential process, it is possible that the first binding event could be that with either the lower or higher affinity value, and the second association would then be of higher or lower binding strength, respectively. This would then reflect a cooperative process, either in the positive or negative sense, again respectively.

The origin of this cooperativity might be an adventitious favorable or unfavorable interaction that may occur between the two units of PDZ3 attached to the bivalent ligand. If beneficial protein-protein contact took place, then there may exist a degree of positive cooperativity in which binding of the first PDZ3 to the ligand is followed by an enhanced affinity for the second PDZ3. Conversely, an unfavorable PDZ3-PDZ3 interaction would behave in opposite fashion, presumably reducing the overall apparent ΔG for ternary complex formation. In either case, fitting the data to yield an appropriate biochemical explanation will be made more difficult. This is, in the absence of more concrete structural data, admittedly speculation, but it is one plausible interpretation of the calorimetric results.

To further characterize the binding interaction, additional temperature-dependent ITC experiments were performed to determine the change in heat capacity (ΔCp) upon binding PDZ3 (see Supporting Information). The heat capacity change for ligand 1 is a positive 73 cal/mol·K, a value significantly different from that of -163 cal/mol·K determined for the monovalent hexapeptide YKQTSV in our prior work.5b In the context of protein-ligand interactions, ΔCp has been correlated with the change in solvent-exposed surface upon complex formation, and so can partially illumine the nature of the binding interaction in the absence of structural data.19 Heat capacity changes have been estimated using empirically-derived equations, such as (1).20

| (1) |

If this is correct, a positive value of ΔCp is predominately a consequence of burial of polar surface area (ΔAp) in a protein-mediated association. Our previous studies suggest nonpolar hydrophobic area is lost upon monovalent ligand binding to PDZ3.5b Here, though, this contribution could be offset by a more significant burial of polar surface area upon complex formation as a result of two proximal PDZ3 proteins bound to a single, short bivalent peptide. Based on the fact that the protein surface is mostly polar this explanation is not unreasonable, but additional experimental evidence would be required before strongly asserting such a hypothesis.

While the ITC data are unambiguous, independent confirmatory evidence for ternary complex formation was sought through electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). The association of PDZ3 domain with ligand 2 was probed under mild ionization conditions so as to hinder dissociation of the complex, given the possibility that the noncovalent forces involved could be prone to disruption. Control experiments with PDZ3 alone and incubated with the corresponding monovalent peptide, YKQTSV, were also recorded under the same experimental conditions (see Supporting Information). The ESI-MS data reinforce the existence of a ternary complex. Formation of a species between two PDZ3 and the bivalent ligand yields an expected mass of 24918 Da, and is verified by the presence of peaks representing different m/z ratios for this complex. In contrast, when PDZ3 is incubated with monomeric YKQTSV, the spectrum contains m/z peaks characteristic of the expected 1:1 PDZ3-YKQTSV complex.

To recapitulate, this study demonstrates that bivalent ligands consisting of short peptide strands can simultaneously recognize two PDZ domains. Future expansions of this approach could include the development of heterodimeric peptides, in which each arm targets a different protein domain (PDZ or otherwise). Multivalency at the level of n = 3 and beyond, up through to dendrimers, is also a possible extension. Additionally, one can then consider the preparation of cellular probes by dedicating one strand for a membrane-permeating peptide sequence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM63021).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Mammen M, Choi S-K, Whitesides G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:2754. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981102)37:20<2754::AID-ANIE2754>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Lean A, Munson PJ, Rodbard D. Mol. Pharmacol. 1979;15:60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christopherson KS, Hillier BJ, Lim WA, Bredt DS. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4(a) Wang S, Yue H, Derin RB, Guggino WB, Li M. Cell. 2000;103:169. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Raghuram V, Mak DO, Foskett JK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031538898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Raghuram V, Hormuth H, Foskett JK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633250100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5(a) Saro D, Klosi E, Paredes A, Spaller MR. Org. Lett. 2004;6:3429. doi: 10.1021/ol049181q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Saro D, Klosi E, Paredes A, Spaller MR. Org Lett. 2004;6:3429. doi: 10.1021/ol049181q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Saro D, Li T, Rupasinghe C, Paredes A, Caspers N, Spaller MR. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6340. doi: 10.1021/bi062088k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6(a) Li T, Saro D, Spaller MR. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:1385. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.09.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Udugamasooriya G, Saro D, Spaller MR. Org Lett. 2005;7:1203. doi: 10.1021/ol0475966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piserchio A, Salinas GD, Li T, Marshall J, Spaller MR, Mierke DF. Chem Biol. 2004;11:469. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowburn D, Zheng J, Xu Q, Barany G. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9(a) Profit AA, Lee TR, Lawrence DS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:280. [Google Scholar]; (b) Profit AA, Lee TR, Niu J, Lawrence DS. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrithers MD, Lerner MR. Chem Biol. 1996;3:537. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward WH, Holdgate GA. Prog Med Chem. 2001;38:309. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6468(08)70097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12(a) Dimick S, Powell S, McMahon S, Moothoo D, Naismith J, Toone E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:10286. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lundquist JJ, Debenham SD, Toone EJ. J Org Chem. 2000;65:8245. doi: 10.1021/jo000943e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dam TK, Roy R, Das SK, Oscarson S, Brewer CF. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Shenoy SR, Barrientos LG, Ratner DM, O’Keefe BR, Seeberger PH, Gronenborn AM, Boyd MR. Chem Biol. 2002;9:1109. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00237-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Dam TK, Roy R, Page D, Brewer CF. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1351. doi: 10.1021/bi015830j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Dam TK, Roy R, Page D, Brewer CF. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1359. doi: 10.1021/bi015829k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Philo JS, Aoki KH, Arakawa T, Narhi LO, Wen J. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1681. doi: 10.1021/bi9524272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Brien R, Rugman P, Renzoni D, Layton M, Handa R, Hilyard K, Waterfield MD, Driscoll PC, Ladbury JE. Protein Sci. 2000;9:570. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.3.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Q, Zheng J, Xu R, Barany G, Cowburn D. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3491. doi: 10.1021/bi982744j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houtman JC, Brown PH, Bowden B, Yamaguchi H, Appella E, Samelson LE, Schuck P. Protein Sci. 2007;16:30. doi: 10.1110/ps.062558507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17(a) Saro D, Li T, Klosi E, Udugamasooriya G, Spaller M. Abstract Peptide Science. Design and Thermodynamic Binding Studies of Cyclic and Multivalent Peptide Ligands for the PDZ Domain; Boston: 2003. p. 297. [Google Scholar]; (b) Paduch M, Biernat M, Stefanowicz P, Derewenda ZS, Szewczuk Z, Otlewski J. Chembiochem. 2007;8:443. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holm A, Jorgensen RM, Ostergaard S, Theisen M. J Pept Res. 2000;56:105. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.2000.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gill SJ, Dec SF, Olofsson G, Wadso IJ. Phys. Chem. 1985;89:3758. [Google Scholar]

- 20(a) Murphy KP, Freire E. Adv Protein Chem. 1992;43:313. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60556-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Spolar RS, Livingstone JR, Record MT., Jr. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3947. doi: 10.1021/bi00131a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.