Abstract

The SDF-1α/CXCR4 ligand/chemokine receptor pair is required for appropriate patterning during ontogeny and stimulates the growth and differentiation of critical cell types. Here, we demonstrate SDF-1α and CXCR4 expression in fetal pancreas. We have found that SDF-1α and its receptor CXCR4 are expressed in islets, also CXCR4 is expressed in and around the proliferating duct epithelium of the regenerating pancreas of the interferon (IFN) γ–nonobese diabetic mouse. We show that SDF-1α stimulates the phosphorylation of Akt, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and Src in pancreatic duct cells. Furthermore, migration assays indicate a stimulatory effect of SDF-1α on ductal cell migration. Importantly, blocking the SDF-1α/CXCR4 axis in IFNγ-nonobese diabetic mice resulted in diminished proliferation and increased apoptosis in the pancreatic ductal cells. Together, these data indicate that the SDF-1α–CXCR4 ligand receptor axis is an obligatory component in the maintenance of duct cell survival, proliferation, and migration during pancreatic regeneration.

Keywords: chemokines; proliferation; regeneration; duct; interferon

Introduction

Chemokines are a superfamily of small secreted proteins known initially for their role in leukocyte trafficking (Luster, 1998; Gale and McColl, 1999; Rossi and Zlotnik, 2000). Chemokines have received much attention for their involvement in the regulation of HIV infection, proliferation, and mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells, fetal development, and regulation of angiogenesis (Kim and Broxmeyer, 1999).

Although most chemokines and receptors have overlapping binding specificity with other family members, SDF-1α and its receptor CXCR4 bind only each other (Kim and Broxmeyer, 1999). CXCR4 has also been the focus of numerous papers because it is a coreceptor for the entry of HIV into T cells (Feng et al., 1996). SDF-1α is involved in the migration of hematopoietic cells to the marrow, and hematopoietic precursors from the bone marrow via the circulation into peripheral tissues (Aiuti et al., 1997; D'Apuzzo et al., 1997). A comprehensive study of the expression of SDF-1α and CXCR4 from gastrulation to organogenesis in the mouse embryo provides evidence of the continuous involvement of the SDF-1α/CXCR4 axis during embryogenesis (McGrath et al., 1999). Furthermore, disruption of the genes for SDF-1α or its receptor results in late embryonic lethality. Importantly, the SDF-1α–deficient mouse and the corresponding CXCR4 mutants are the only known chemokine/chemokine receptor mutants that display embryonic lethality (Murphy et al., 2000). Genetically deficient embryos display severe defects in their gastrointestinal vasculature, cerebellar neuron migration, cardiac ventricular septal closure, B cell development, and hematopoietic bone marrow colonization (Nagasawa et al., 1996; Ma et al., 1998; Tachibana et al., 1998; Zou et al., 1998). The extensive consequences observed in different organ systems in the SDF-1α and CXCR4 knockout mice indicate that the SDF-1α–CXCR4 axis is an essential component of differentiation of numerous tissues.

The terminal differentiation of the pancreatic endocrine cells from epithelial progenitor cells occurs during their migration from the duct wall into primitive islet-like structures (Slack, 1995). The process involves the remodeling of the cell surface and a change in the adhesive properties of these cells as they migrate (Cirulli et al., 2000). The signals governing this migration are not fully defined. Based on the demonstrated involvement of the SDF-1α–CXCR4 pair in the migration and proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells, we hypothesized that this ligand–receptor pair may be important during pancreatic endocrine cell development. However, because the genetically deficient mice suffer from widespread midgestational defects, it is difficult to address the requirement for CXCR4/SDF-1α during embryonic development. Therefore, we sought to determine the role of CXCR4 ligation during pancreatic islet regeneration.

In transgenic mice in which the cytokine IFN-γ is expressed under the control of the insulin promoter, the pancreas displays remarkable ductal hyperplasia and regeneration of new islets (Sarvetnick et al., 1988; Gu and Sarvetnick, 1993, 1994). Previous work suggests the pancreatic islet regeneration proceeds through the same intermediates as does islet formation during ontogeny (Gu and Sarvetnick, 1993, 1994; Kritzik et al., 1999, 2000). We have found that spontaneous islet regeneration in the IFNγ transgenic mouse recapitulates the pancreatic developmental program in adults (Kritzik et al., 1999, 2000).

In this work, we tested the hypothesis that CXCR4 ligation is required for the differentiation of pancreatic islets during regeneration. Our results strongly support an essential role for the SDF-1α–CXCR4 pair during IFNγ induced pancreatic regeneration.

Results

Chemokine expression in the IFNγ-nonobese diabetic (NOD) pancreas

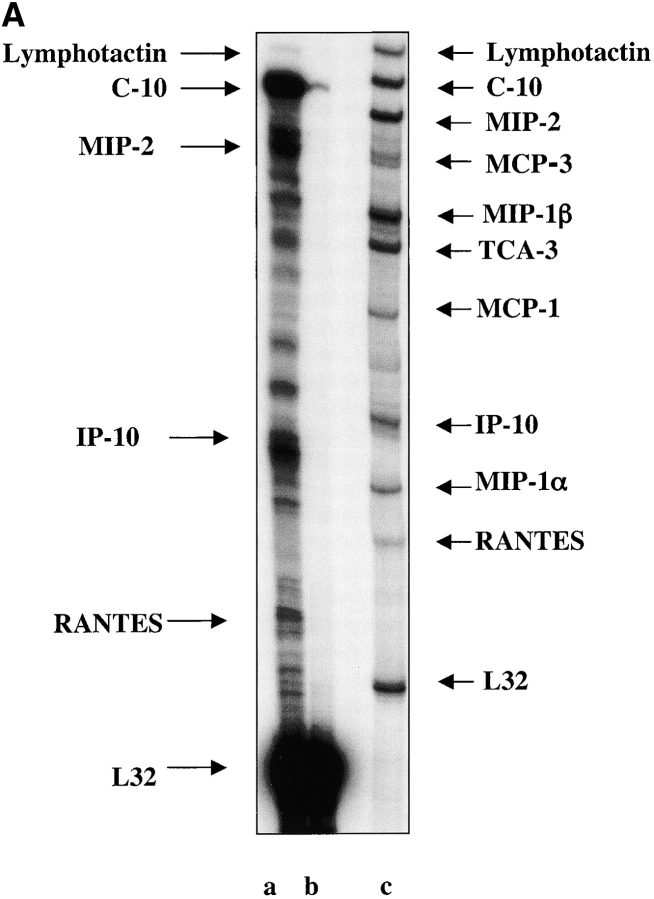

The cytokine IFNγ has been shown to induce the expression of a number of chemokines, specifically IFN-γ–inducible protein 10 kD (IP-10), monokine induced by γ IFN (MIG), and IFN-inducible T cell α chemoattractant in different tissues (Luster et al., 1985; Kaplan et al., 1987; Luster and Ravetch, 1987; Gottlieb et al., 1988; Ransohoff et al., 1993; Cassatella et al., 1997; Sauty et al., 1999). We hypothesized that IFNγ-induced chemokines may have an effect on the migration of pancreatic progenitors to their appropriate niche where they could differentiate into the endocrine cells of the pancreas. To investigate the induction of chemokines by IFNγ expression in the pancreas, we used RNase protection assays. The chemokines that were induced by the IFNγ transgene compared with nontransgenic NOD mice were: small inducible cytokine A6 (C-10); IP-10; macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-2 ; regulated on activation normal T-cell expressed and secreted (RANTES; Fig. 1 A); MIG; monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-5; SDF-1α; thymus-derived chemotactic agent 4 (TCA-4); and small inducible chemokine A 11 (Eotaxin; Fig. 1 B). In the NOD pancreas, five of the chemokines were detected: C-10, MIG, SDF-1α, TCA-4, and Eotaxin. The relative expression of chemokines in the transgenic mouse pancreas compared with the NOD pancreas is shown in Table I. As determined by densitometry, C-10 expression was elevated 12-fold in the IFNγ transgenic pancreas compared with the NOD pancreas. The expression of MIG was enhanced approximately sixfold in the transgenic pancreas. SDF-1α expression was elevated threefold, and TCA-4 and Eotaxin were expressed at five- and fourfold higher levels than in the NOD pancreas, respectively. Of the CHK2 chemokines expressed in the IFNγNOD pancreas, MIG was the most abundant. MIG expression was ∼3.5-fold higher than that of MCP-5 and almost 1.7-fold that of SDF-1α. IP10, C-10, and RANTES expression were modest compared with the MIG, MCP-1, and SDF-1α (the CHK1 samples had to be exposed for a longer time to be able to detect expression). All densitometric comparisons were performed by normalizing the data to the mitochondrial housekeeping gene L32.

Figure 1.

Chemokine expression in adult regenerating pancreas. (A) The expression of CHK1 group of chemokines in whole pancreas from IFNγNOD transgenic mice (lane a) and NOD (lane b) controls. RPA probe CHK1 is shown in lane c and gel positions of chemokines are indicated with arrows. In the control lane, the probes typically run more slowly than the digested fragments from target RNA due to the presence of restriction sites in the samples. The autoradiograph shown is representative of two independent experiments. (B) Expression of CHK2 group of chemokines in whole pancreas from IFNγNOD transgenic mice (lane a) and NOD (lane b) controls. RNase protection was performed on pooled RNA samples from three mice. The RPA probe CHK2 is shown in lane c and gel positions of chemokines are indicated with arrows. As in A, a second identical experiment yielded very similar results.

Table I.

Chemokine and chemokine receptor induction by the IFNγ transgene in the NOD mouse pancreas

| Chemokines | NOD | IFNγNOD |

|---|---|---|

| C-10 | 1 | 12X |

| MIG | 1 | 6X |

| SDF-1α | 1 | 3X |

| TCA-4 | 1 | 5X |

| Eotaxin | 1 | 4X |

| Chemokine receptors | ||

| CXCR4 | 1 | 4X |

| CXCR5 | 1 | 2.5X |

| DARC | 1 | 2.5X |

Chemokine receptor expression in the IFNγNOD pancreas

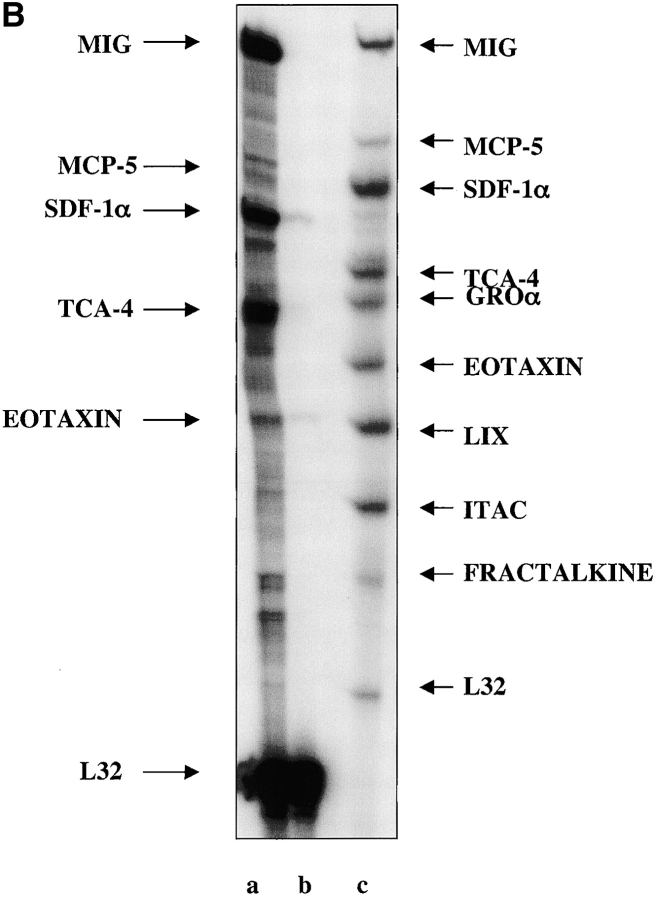

Chemokines induce their effects by binding G protein–coupled receptors. We used probes for chemokine receptors to determine their expression in NOD and IFNγNOD mouse pancreas. The chemokine receptors induced in the IFNγNOD mouse pancreas were CCR6, CCR7, CCR1, CCR3, CCR5, CXCR5, DARC, CX3CR1, and CXCR4 (Fig. 2, A and B). In the NOD only CXCR4, CXCR5, and DARC were detected. The relative expression of the chemokine receptors in the transgenic pancreas compared with the NOD pancreas is shown in Table I. In the transgenic pancreas, CXCR4 and CXC3CR1 were expressed at approximately fourfold higher levels compared with the NOD pancreas. Of the CXC group of chemokine receptors, CXCR4 was the most abundantly expressed in the IFNγNOD regenerating pancreas (Fig. 2 B). The CX3CR1 receptor was the second most abundant in this group.

Figure 2.

Expression of chemokine receptors in adult regenerating pancreas. (A) Expression of CCR group of chemokine receptors in whole pancreas from IFNγNOD transgenic mice (lane a) and NOD (lane b) controls. The RPA probe for CCR is shown in lane c. (B) Expression of CXCR group of chemokine receptors in IFNγNOD (lane a) and NOD (lane b) pancreas was determined as described in A. The RPA probe for CXCR is shown in lane c. As with the chemokine expression experiments a second experiment yielded similar findings. Gel positions of chemokine receptors are indicated with arrows.

Localization of SDF-1α and CXCR4 expression in the pancreas

Of the chemokines and chemokine receptors that we found to be induced by IFNγ, the SDF-1α/CXCR4 pair has been shown to be an important regulator of cell migration, proliferation, and embryonic development. Next, we performed histological studies to determine whether the immunolocalization of SDF-1α and CXCR4 was consistent with their involvement in epithelial migration in the transgenic pancreas.

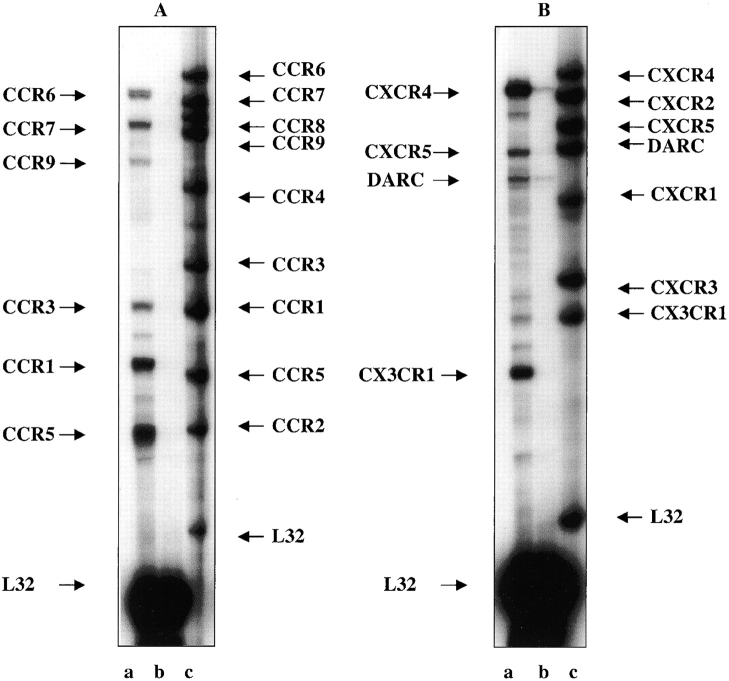

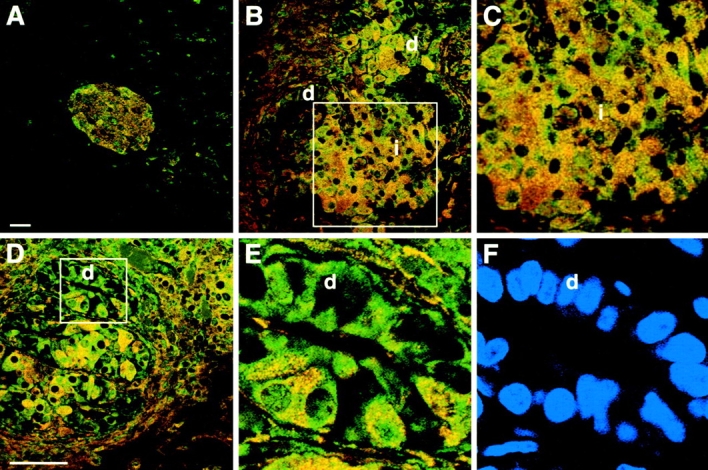

In the NOD mouse pancreas, SDF-1α and CXCR4 expression was detected in islets by immunofluorescence (Fig. 3 A). In addition, SDF-1α expression was confirmed by Western blot analysis of proteins expressed by isolated pancreatic islets (unpublished data). The expression of SDF-1α in NOD mice appeared constitutive because in vitro treatment of the islets by IFNγ (1,000 U/ml) for 24 h did not augment SDF-1α expression, as determined by Western blotting (n = 2; unpublished data). In the IFNγNOD mouse, SDF-1α staining was localized to cells within the islet mass (Fig. 3, B and C). In the duct epithelium, frequent cells, which express only CXCR4 (Fig. 3 E, green), and occasional cells, which coexpress CXCR4 and SDF-1α (Fig. 3 E, yellow), were observed. Thus, the majority of duct cells express CXCR4, suggesting that these cells may be migrating toward the SDF-1α expressing newly forming islets.

Figure 3.

SDF-1α and CXCR4 colocalize in the islets of NOD and IFNγNOD pancreas. Panel A depicts a confocal image of NOD islet stained with SDF-1α (red) and CXCR4 (green) antibodies. Panel B shows SDF-1α and CXCR4 staining in an area of ductal proliferation and islet formation in the IFNγNOD pancreas. The central region of B which comprises the islet mass is magnified in C. Note that several islet cells exhibit SDF-1α (red) expression; others exhibit CXCR4 (green) expression, whereas the majority of cells exhibit double staining (yellow). A second region of ductal proliferation is shown in D. A prominent ductal region shown in the square is magnified in E. Most of the ductal cells in this region stain for CXCR4 only, with several of the cells exhibiting colocalization of CXCR4 and SDF-1α. Panel F shows nuclear staining (blue) of the region in E, confirming its ductal morphology (d, duct; i, islet). Bars, 25 μm.

CXCR4 and SDF-1α expression in embryonic pancreas

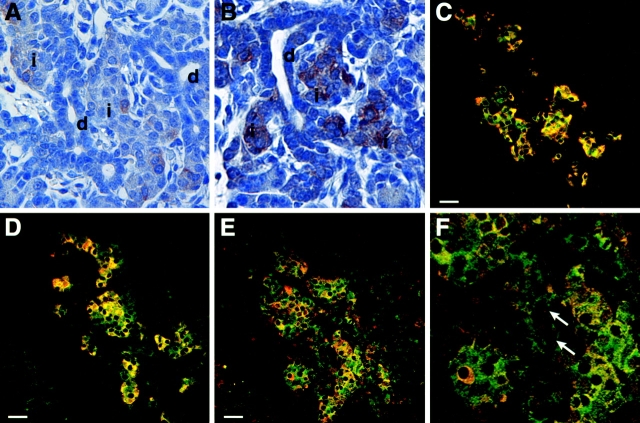

We asked whether the expression of the chemokine SDF-1α and its receptor CXCR4 were involved in the development of islets during embryogenesis. E18 embryos were used as they display extensive islet neogenesis at this point. Immunostaining of the pancreas from these embryos revealed expression of SDF-1α (Fig. 4 A) and CXCR4 (Fig. 4 B) in fetal pancreas. Our results show that SDF-1α and CXR4 are localized to primitive islet cell clusters. However, the ducts are negative for SDF-1α expression (Fig. 4 A) while they display CXCR4 (Fig. 4 B) expression. In the embryonic pancreas, both SDF-1α (Fig. 4 C, green) and CXCR4 (Fig. 4 D, green) were found to be frequently coexpressed with insulin (red). CXCR4 staining was often adjacent to insulin expressing cell clusters (Fig. 4 D). Double immunofluorescent staining of CXCR4 and SDF-1α (Fig. 4, E and F) revealed that some cells in the primitive islet structures express SDF-1α (red) and duct cells expressed CXCR4 (Fig. 4, D and E, green). However, the two were often colocalized, suggesting that this chemokine may be involved in the recruitment of cells from ducts into the developing islet cell clusters.

Figure 4.

SDF-1a and CXCR4 expression in embryonic NOD pancreas. Panel A illustrates SDF-1α expression by DAB staining in primitive islet structures in the fetal pancreas. Ductal areas are clear of SDF-1α staining. Panel B depicts CXCR4 expression in primitive islets and also in some ductal cells (d, duct; i, islet). (C) Representative double immunofluorescent images of SDF-1α (green) and insulin (red) reveal extensive colocalization (yellow) in the E18 pancreas with a population of cells expressing SDF-1α alone. (D) Insulin (red) and CXCR4 (green) immunofluorescent staining demonstrating that some cells display coexpression of CXCR4 and insulin (yellow), with a significant number of cells staining only for CXCR4. (E) Double immunofluorescent staining of CXCR4 (green) and SDF1-α (red) demonstrates that contiguous cells in the primitive islet clusters can express the ligand, the receptor, or both (yellow). (F) A ductal region surrounded by developing islet clusters magnified from E. Arrows point to duct cells. Bars, 25 μm.

In vitro stimulation of cell migration by SDF-1α

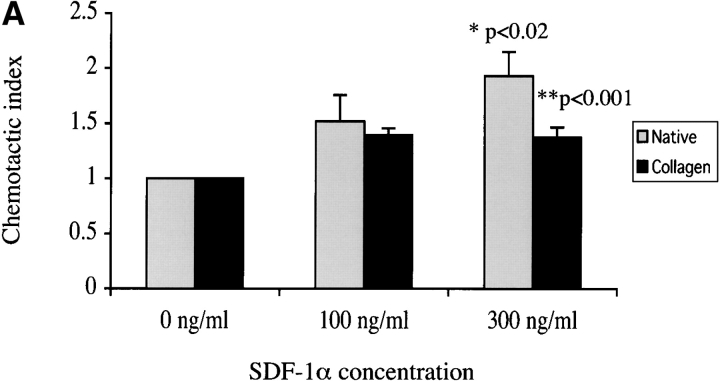

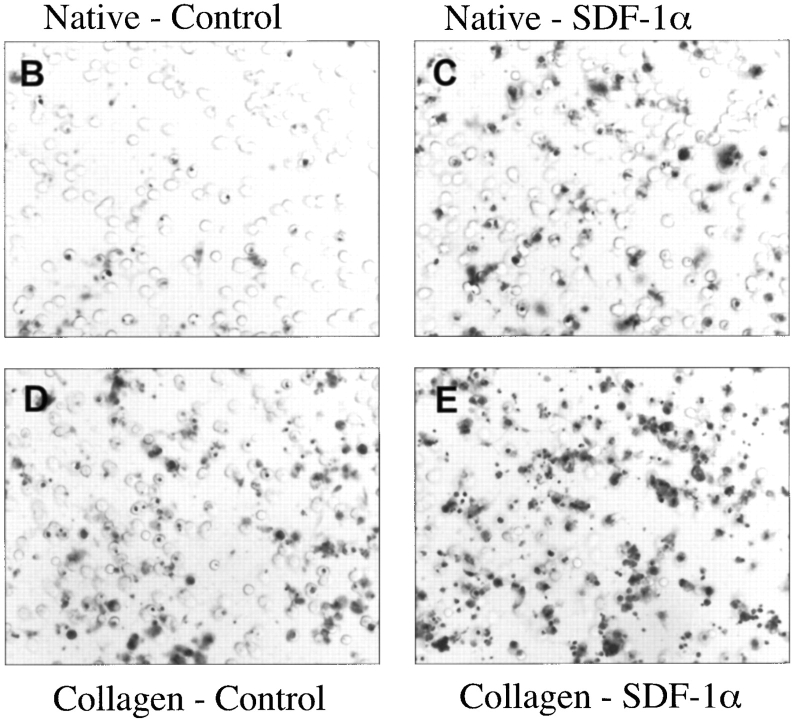

To test the hypothesis that SDF-1α can stimulate the migration of ductal progenitor cells of the regenerating pancreas, we performed in vitro migration assays using cells isolated from the pancreatic ductal network of regenerating IFNγNOD.scid mice. We measured the effect of SDF-1α on the migration of these cells using native or type 1 collagen–coated membrane inserts. Interestingly, the stimulatory effect of SDF-1α was most pronounced in the absence of collagen. 100 and 300 ng/ml of SDF-1α enhanced duct cell migration by 52 and 93% (P < 0.02), respectively. In the presence of collagen, chemotaxis was increased by ∼38% at both 100 and 300 ng/ml concentrations of SDF-1α (P < 0.001; Fig. 5 A). Interestingly, collagen coating of the inserts greatly enhanced the apparent basal and SDF-1α induced migration of the ductal cells (Fig. 5, D and E). This could be because the freshly isolated cells exhibit increased survival in the presence of the matrix coating. Alternatively, collagen may increase the adhesion of these cells, accounting for the reduced ability of SDF-1α to induce chemotaxis. Together, the data demonstrate that ductal cells from the regenerating pancreas migrate in response to SDF-1α and their migration in vitro is clearly modulated by the presence of ECM.

Figure 5.

SDF-1α stimulates in vitro migration of pancreatic ductal cells. (A) Cell migration was measured in the presence and absence of collagen coating. Each bar represents either basal migration or fold stimulation from basal in a total of six membranes from three experiments (mean ± SEM); P < 0.02 for migration on native membranes and P < 0.001 on collagen-treated membranes by analysis of variance. B and C are two representative fields of (B) basal and (C) SDF-1α–stimulated (300 ng/ml each) ductal cells on uncoated membranes. D and E depict two fields of (D) basal and (E) SDF-1α–stimulated ductal cells migrating on collagen I–coated membranes.

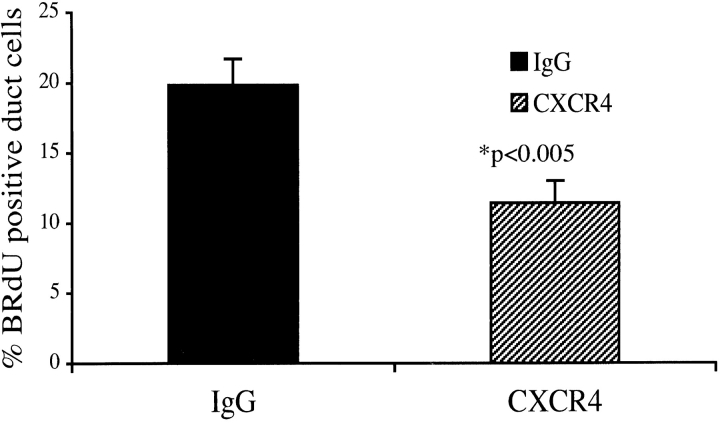

Effect of CXCR4 neutralization on ductal cell proliferation in the IFNγNOD pancreas

We have hypothesized that cell migration is critical for the regenerative process to occur. Because we observed the CXCR4 receptor induced in the expanding epithelium of the transgenic pancreas, and because in vitro studies demonstrated the ability of SDF-1α to induce transgenic ductal cell migration, we asked whether this receptor–ligand interaction participated in the regenerative process. Therefore, we determined the outcome of blocking SDF-1α binding by treating the IFNγ transgenic mice with a CXCR4 neutralizing antibody (Gonzalo et al., 2000). For this analysis, two groups of 12-wk-old IFNγNOD mice were intravenously treated with 20 μg/mouse CXCR4 blocking antibody (n = 8) or rabbit IgG (n = 7) every third day for 2 wk. Normally, 12-wk-old transgenic mice display strong proliferative activity, as evidenced by BrdU incorporation, with the development of elaborate ducts and formation of new islets in the pancreas (Gu and Sarvetnick, 1993). We stained sections from different levels of the pancreas of each mouse and counted the BrdU-positive duct cells, as well as the total number of duct cells. The CXCR4 antibody treatment resulted in a 42% decrease in the ratio of BrdU labeled duct cells to the total number of duct cells in the IFNγNOD pancreas compared with IgG-treated control mice (CXCR4 = 19.8%; IgG controls = 11.41%; Fig. 6). This significant (P < 0.005) decrease in the proportion of BrdU-positive duct cells indicates that the SDF-1α/CXCR4 axis has a critical role in the net expansion of the regenerating duct epithelium.

Figure 6.

CXCR4 neutralizing antibody treatment diminishes BrdU incorporation in the regenerating pancreatic duct cells of the IFNγNOD mouse. The ratio of BrdU-positive ductal cells to the total number of ductal cells is expressed as a mean percentage ± SEM (P < 0.005).

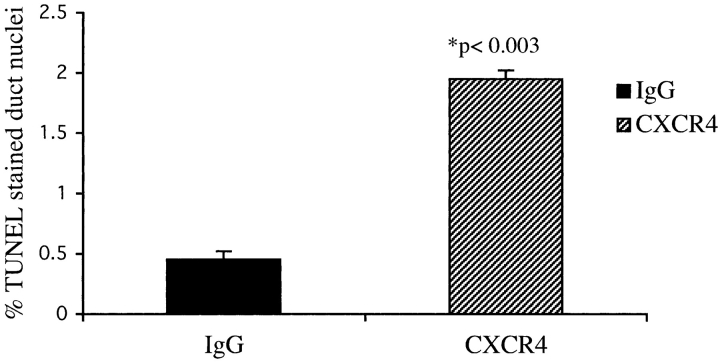

The effect of CXCR4 neutralization on survival in IFNγNOD pancreata

Remodeling and directed movement of tissue in development involves regulation of both cell proliferation and programmed cell death (Zakeri and Lockshin, 2002). Apoptotic cell death has also been demonstrated to be involved in the homeostatic regulation of hematopoiesis (Peters et al., 1998). Indeed, the decreased incorporation of BrdU in the CXCR4-treated mice could reflect either decreased duct cell replication or increased turnover of the duct cell population. Therefore, we decided to assess cell turnover by measuring apoptosis in the pancreatic epithelial duct cells, quantitating fragmented DNA using the TUNEL method in the CXCR4 antibody–treated and control IgG–treated mice. Treatment of IFNγNOD transgenic mice with the CXCR4 blocking antibody resulted in a fourfold increase in the number of pancreatic ductal nuclei displaying fragmentation (2.0%; P < 0.003; Fig. 7). The number of duct cells undergoing apoptosis was 0.5% in control IFNγNOD mice treated with rabbit IgG. Our results demonstrate a destabilizing effect of blocking CXCR4–SDF-1α interactions on the survival of duct cells in vivo.

Figure 7.

CXCR4 neutralization increases apoptosis in the pancreatic duct cells of the IFNγNOD mouse. Sections from the pancreas of two mice each from the CXCR4 antibody–treated and control groups were assessed for apoptosis using the TUNEL method. The number of apoptotic nuclei was quantitated as a percentage of the total number of duct cells in the pancreas. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (P < 0.003).

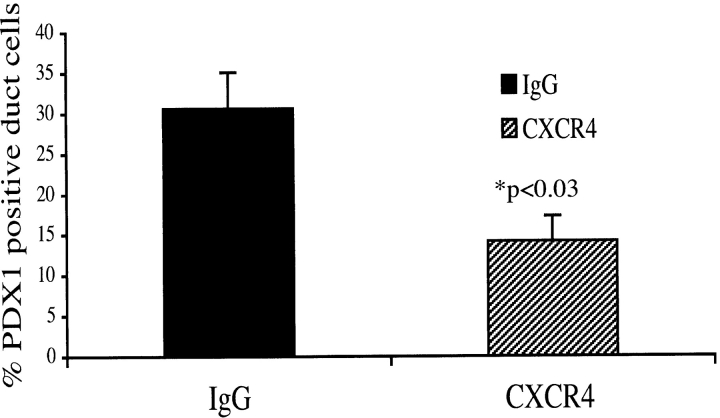

The effect of CXCR4 neutralization on the proportion of pancreatic progenitors present in ductal cells

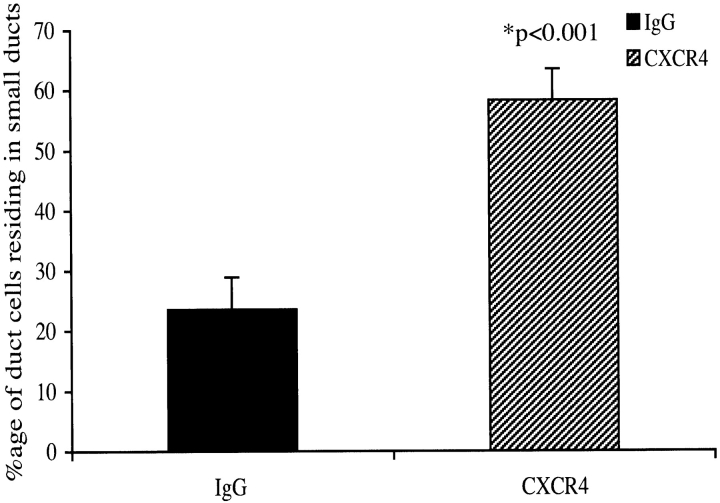

We postulated that the decline in ductal cell replication, and augmentation in apoptosis in response to CXCR4 neutralizing antibody could affect the proportion of pancreatic progenitor cells in the regenerating pancreas. The pdx1 gene is a key regulator of pancreatic development and insulin expression on β cells (Jonsson et al., 1994; Offield et al., 1996). We have demonstrated previously that the proliferating ducts in the IFNγ transgenic mouse pancreas express pancreatic duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX1; Kritzik et al., 1999). Treatment with the CXCR4 neutralizing antibody (n = 4) led to a 50% decrease in the number of ductal cells expressing PDX1 compared with IgG-treated controls (n = 4; P < 0.03; Fig. 8). These results suggest that the SDF-1α–CXCR4 interaction may be affecting the size of the population of ductal cells that could differentiate into insulin-producing cells. Interestingly, the inhibition of the SDF-1α–CXCR4 axis impacted the average diameter of ducts. Although the actual number of duct cells in the treatment and control groups were not statistically significantly different (not depicted), the number of duct cells residing in smaller ducts were increased significantly in the CXCR4-treated group (n = 7) compared with IgG-treated controls (n = 7; P < 0.001; Fig. 9). These data are consistent with a role for SDF-1α and CXCR4 in the initiation of expansion and recruitment to facilitate islet differentiation.

Figure 8.

CXCR4 neutralization causes reduced numbers of PDX1-positive progenitor cells within the ductal cell population in the IFNγNOD pancreas. Sections from the pancreas of four mice each from the CXCR4 antibody treatment and control groups were assessed for PDX1 expression. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (P < 0.03).

Figure 9.

Disruption of the CXCR4 SDF-1α axis shifts the distribution of the duct cell population into smaller ducts. Hematoxylin stained sections from BOUIN's fixed pancreas from CXCR4 neutralizing antibody (n = 7) or rabbit IgG (n = 7) were scored for ductal cells. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (P < 0.001).

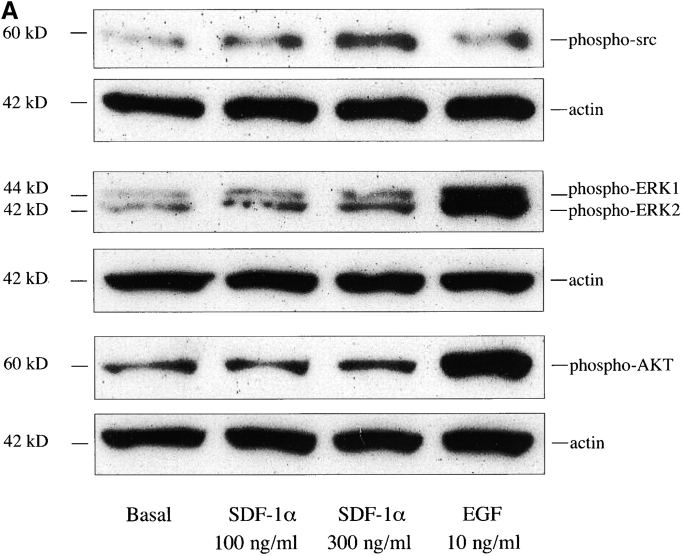

Stimulation of freshly isolated ductal cells with SDF-1α induces tyrosine phosphorylation of Src, MAPK, and Akt (protein kinase B)

SDF-1α has been shown to transduce its actions by binding its G protein–coupled seven transmembrane receptor CXCR4 and activating p44/42 MAPK, PI3-Kinase, and Akt (Ganju et al., 1998; Majka et al., 2000; Vlahakis et al., 2002; Floridi et al., 2003). The Src family of tyrosine kinases have been have been reported to be involved in the activation of migration in different cell types (Datta et al., 1997; Coffer et al., 1998; Lowell and Berton, 1998; O'Laughlin-Bunner et al., 2001; Inngjerdingen et al., 2002). Therefore, we wanted to determine if SDF-1α could stimulate the phosphorylation of MAPK, Akt, or Src, signaling proteins that are potentially associated with the proliferation, survival, or migration of ductal cells. Cells isolated from the pancreatic ducts of IFNγNOD mice were serum-starved overnight, and stimulated with 100 or 300 ng/ml of SDF-1α or 10 ng/ml of EGF for 5 min. Fig. 10 A shows SDF-1α and EGF-stimulated phosphorylation of Src, MAPK, and Akt in vitro. EGF-stimulated MAPK and Akt phosphorylation in these cells. SDF-1α–stimulated Src phosphorylation about twofold at 300 ng/ml, where we observed a striking effect of the chemokine on migration. Our findings suggest a potential role for Src in the regulation of migration by SDF-1α in the duct progenitor cells of the regenerating pancreas.

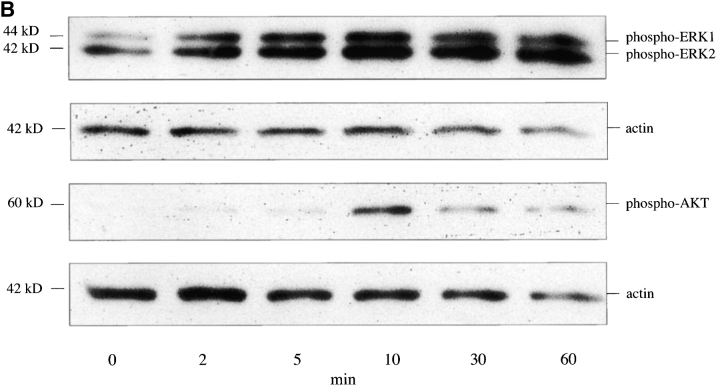

Figure 10.

SDF-1α stimulates Src, Akt, and MAPK phosphorylation in pancreatic duct cells. (A) SDF-1α stimulates Src phosphorylation in the pancreatic duct cells of the IFNγNOD mouse. Cells were stimulated with 100 or 300 ng/ml SDF-1α or 10 ng/ml EGF for 5 min at 37°C. Whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to phospho-Src, phospho-MAPK, and phospho-Akt. The blots were stripped and reblotted with antiactin antibody to confirm equal protein loading. (B) Time course for SDF-1α–stimulated phosphorylation of MAPK (ERK1 and ERK2) and Akt in pancreatic duct cells of the IFNγNOD mouse. Cells were treated with 300 ng/ml SDF-1α at 37°C for 0, 2, 5, 10, 30, and 60 min. Whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to phospho-MAPK and phospho-Akt.

The time courses of stimulation of the phosphorylation of signaling proteins vary depending on the specific ligand. Therefore, we examined the time courses of SDF-1α stimulation of MAPK and Akt phosphorylation in freshly isolated ductal cells. Cells were isolated and serum-starved overnight as indicated in the previous paragaph, and stimulated with 300 ng/ml SDF-1α for 0, 2, 5, 10, 30 or 60 min. Fig. 10 B shows the time course of the phosphorylation of MAPK (p42, p44 ERK1, and ERK2) and Akt. SDF-1α–stimulated ERK1 and ERK2 phosphorylation was first seen at 2 min and reached a peak at ∼10 min. The stimulation of Akt phosphorylation by SDF-1α was not evident until 10 min, at which point it was very potent (∼30-fold by densitometry). The dramatic phosphorylation of Akt and to a lesser extent MAPK and Src, in response to SDF-1α in duct cells of the IFNγNOD transgenic mice, indicate a potential involvement of these signaling proteins in the regulation of migration, proliferation, and survival of the pancreatic progenitor population.

Discussion

Our focus was to identify chemokines that are involved in cell migration within the regenerating pancreas. SDF-1α and CXCR4 expression, as determined by RNase protection assays, were greatly enhanced in the IFNγNOD mouse pancreas. Our experiments revealed expression of this chemokine–chemokine receptor pair in the regenerating IFNγNOD pancreas and in the developing islet clusters of NOD embryos. In vivo blocking experiments demonstrated that the CXCR4 receptor is an obligatory component of pancreatic regeneration. A concomitant augmentation in apoptosis in response to CXCR4 antibody treatment indicated that an antiapoptotic effect of CXCR4 ligation in the ductal epithelial cells is a component of the enhanced ductal expansion in the regenerating pancreas. Furthermore, we report a direct stimulatory effect of SDF-1α on the migration of cells isolated from the ducts of the regenerating adult pancreas. Therefore, our data suggests that the IFNγ induced elevation in the expression of SDF-1α in the duct epithelium of the pancreas results in the chemotactic migration of CXCR4 expressing cells, in response to the SDF-1α gradient.

Importantly, neutralization with CXCR4 antibody elicited a fourfold increase in the proportion of apoptotic ductal cells. The role of CXCR4 in the regulation of apoptosis is context dependent. CXCR4 involvement in the stimulation of apoptosis by HIV envelope proteins in CD4+ T cells has been an area of extensive study (Herbein et al., 1998; Biard-Piechaczyk et al., 1999; Colamussi et al., 2001; Yao et al., 2001; Arthos et al., 2002). Similarly, CXCR4 regulation of the apoptotic effect of HIV coat proteins on neurons of the neocortex has also been reported (Corasaniti et al., 2001). In contrast, SDF-1α has been reported to promote survival by inhibiting apoptosis in hematopoietic progenitor cells (Lataillade et al., 2002). Furthermore, in fetal thymus organ culture, SDF-1α enhanced viability of serum-depleted cells in culture by down-regulating the pro-apoptotic bax protein and up-regulating the antiapoptotic bcl-2 protein (Hernandez-Lopez et al., 2002). Interestingly, transgenic mice expressing SDF-1α under a Rous sarcoma virus promoter display enhanced spleen and bone marrow myelopoiesis in vivo (Broxmeyer et al., 2003). Myeloid progenitors from the SDF-1α transgenic mice also exhibit prolonged survival in the absence of growth factors in vitro compared with progenitors from wild-type mice. In our pancreatic regeneration model, it appears that blocking the CXCR4 receptor resulted in an augmentation of apoptosis, indicating a role for the CXCR4 receptor in promoting survival of the ductal cell precursor pool in the regenerating ducts, similar to its role in hematopoietic progenitor cells. Our observation of diminished numbers of ductal cells expressing PDX1, a critical pancreatic progenitor marker, in mice treated with CXCR4 neutralizing antibody is consistent with the concurrent enhanced programmed cell death.

The endocrine progenitor cells in the ductal epithelium of the IFNγNOD pancreas display primitive cell markers (unpublished data), and may be migrating in response to local changes in SDF-1α concentration and variations in CXCR4 expression in the cells in response to the cytokine IFNγ. Once recruited to a niche where growth factors stimulate their proliferation and differentiation, these progenitors assume an endocrine cell lineage. The stimulatory effect of SDF-1α on the migration of CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells was established relatively early (Aiuti et al., 1997; Kim and Broxmeyer, 1998; Mohle et al., 1998). Of the many chemokines assayed SDF-1α was the first to have been shown to affect directed movement of myeloid progenitor cells (Broxmeyer et al., 1999). Wright et al. (2002) have reported recently that a purified population of hematopoietic stem cells expresses CXCR4 and migrates in response to SDF-1α in vitro. The mobilization of stem cells in and out of the bone marrow is important in therapeutic transplant procedures. However, what is more intriguing is whether these hematopoietic stem cells can migrate to sites of inflammation and differentiate into other tissue cell types (Krause et al., 2001). In vivo, SDF-1α is produced by bone marrow (Bleul et al., 1996) and the epithelial cells in many organs such as lung (Aiuti et al., 1997). Two recent papers provide evidence of CXCR4 expression in epithelial colon cells (Dwinell et al., 1999; Jordan et al., 1999). Interestingly, another class of cells of epithelial origin that express CXCR4 receptors are breast cancer cells, both primary and metastatic (Muller et al., 2001). Furthermore, using neutralizing antibodies for CXCR4 resulted in a significant reduction in metastatic ability indicating a clear effect of CXCR4 in the migration of breast cancer cells.

We present evidence that Src, MAPK, or Akt phosphorylation may potentially be involved in the stimulation of migration of the ductal cells by SDF-1α. In vitro stimulation of the freshly isolated ductal cells with SDF-1α resulted in the phosphorylation of MAPK and Akt. The robust SDF-1α effect on Akt phosphorylation coupled with the in vivo results of an augmentation of apoptosis with CXCR4 neutralization suggests an involvement of Akt in the promotion of survival of duct cells. Therefore, it is possible for SDF-1α to have a direct effect on proliferation and survival. Alternatively, CXCR4 expression might induce migration of progenitor cells to niches where they can be stimulated to proliferate, and subsequently, differentiate into endocrine cells. Importantly, we have shown previously that inhibition of the infiltration of macrophages did not play a role in the observed proliferation and islet regeneration in the IFNγ transgenic mice (Gu et al., 1995).

In the current paper, we report the limited expression of the chemokines C-10, MIG, TCA-4, Eotaxin, and SDF-1α in the 8-wk-old NOD pancreas. We had reported previously low level C-10 expression in the 10-wk-old NOD mouse pancreas (Bradley et al., 1999). In this earlier paper, Th1 cells harvested from primary cultures expressed high levels of lymphotactin, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and MCP-1, and low levels of IP-10 and RANTES, when stimulated with anti-CD3. In addition, Chen et al. (2001) have reported the expression of MCP-1 in pancreatic islets isolated from NOD mice at the peak of insulitis (8–10 wk) using RT-PCR; and Cameron et al. (2000) observed a progressive increase in MIP-1α production by the NOD pancreas peaking at 5 wk, and MCP-1 expression starting to rise by 10 wk. In the latter paper, chemokine expression was measured by ELISA. The discrepancies in the findings by different investigators may reflect differences in the time course of insulitis progression in the NOD mice, methods used to measure expression of the chemokines, and the genders of the NOD mice. Furthermore, as the analysis of whole pancreas RNA clearly masks important local differences in chemokine and chemokine receptor expression, the localization and potential significance of chemokines both in the pathogenesis of diabetes and islet regeneration still remain challenging fields of study.

In conclusion, this paper provides in vivo evidence for a role of the SDF-1α–CXCR4 chemotaxis axis in a model of tissue regeneration. Importantly, elucidating the molecular mechanisms involved in the stimulation of migration and proliferation and the diminution of apoptosis in the epithelial precursor cells in the regenerating pancreas will help devise effective means for islet replacement in the future.

Materials and methods

Mice

The transgenic mice expressing IFNγ in the pancreatic β cells have been described previously (Gu and Sarvetnick, 1993, 1994; Sarvetnick et al., 1988, 1990). The IFNγ transgenic mice used in the present work were on the NOD and NOD.scid background (Makino et al., 1980; Prochazka et al., 1992). The NOD background provides an excellent model for type 1 diabetes.

RNase protection assays

Total RNA was extracted from pancreata from 8-wk-old male IFNγNOD and NOD mice using an RNeasy Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Pancreatic RNA was pooled from three IFNγNOD transgenic mice and three NOD mice for the RNase protection assays. This process was repeated two independent times. In-house chemokine and chemokine receptor probes were used to perform the RNase protection assays as described previously (Asensio and Campbell, 1997; Boztug et al., 2002). The CHK1 chemokine probe detects lymphotactin, C-10, MIP-2, MCP-3, MIP-1β, T cell activation gene 3, MCP-1, IP-10, MIP-1α, and RANTES. The CHK2 probe detects MIG, MCP-5, SDF-1α, TCA-4, growth-regulated oncogene α, Eotaxin, lipopolysaccharide-induced CXC chemokine, IFN-inducible T cell α chemoattractant, and Fractalkine. The probe for the CCR group of chemokine receptors included CCR6, CCR7, CCR8, CCR9, CCR4, CCR3, CCR1, CCR5, and CCR2. The probe for the CXCR group of receptors included CXCR4, CXCR2, CXCR5, DARC, CXCR1, CXCR3, and CX3CR1. Autoradiographs were analyzed by densitometry using NIH Image 1.63 for quantitation.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Pancreata from IFNγNOD transgenic, NOD mice, and E18 NOD embryos were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin embedded tissue was cut into 4-μm sections and stained using rabbit polyclonal anti–SDF-1α antibody against mouse SDF-1α (Cell Sciences), goat polyclonal anti-CXCR4 antibody raised against the NH2-terminal extracellular domain of mouse CXCR4 receptor (Capralogics Inc.), or guinea pig antibody against insulin (DakoCytomation). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. For double immunofluorescent detection, biotinylated secondary goat, rabbit, and guinea pig antibodies (Vector Laboratories) were used, followed by streptavidin-conjugated Alexa Fluor 488 and 568 (Molecular Probes Inc.). The first streptavidin-conjugated Alexa Fluor (488) incubation was followed by avidin and biotin blocking (Vector Laboratories). After the Alexa Fluor (568) incubation, the sections were placed in mounting medium from The Slowfade Light Antifade Kit (Molecular Probes Inc.). Nuclei were visualized with TOPRO3 (Molecular Probes Inc.). Sections were analyzed on a scanning confocal microscope (model MRC 1024; BioRad Laboratories), mounted on an Axiovert TV-100 with 40 or 63X objectives (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.).

Pancreatic ductal cell purification and islet isolation

Cells of the pancreatic ductal network were purified from 10- to 12-wk-old IFNγNOD.scid mice for the migration experiments and IFNγNOD mice for the assessment of in vitro phosphorylation of signaling proteins. The pancreata were collagenase (1 mg/ml; Roche) digested for 45 min. The digest was filtered through a 200-μm mesh and the ductal network above the mesh was treated with 0.05% trypsin, 0.53 mM EDTA. The resulting cell suspension was filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer. The cells in the filtrate were resuspended in RPMI medium. Approximately one million duct cells were derived from each pancreas preparation. The viability of these duct cells ranges from 75 to 95%. Pancreatic islets were isolated and cultured as described previously (Flodstrom et al., 2002).

Migration assays

Chemotaxis was assessed using uncoated or collagen-coated culture plate inserts (12-μm pore; 12-mm diam; Millipore) placed into 24-well plates. Half the inserts were coated with 3.48 mg/ml collagen type I (BD Biosciences), diluted threefold with 95% ethanol, 2 h at RT, and blocked with 1% BSA. Freshly isolated ductal network cells resuspended in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium (200,000 cells in 200 μl) were added to the upper chambers. 600 μl of RPMI 1640 medium with 0, 100, or 300 ng/ml of SDF-1α (PeproTech) was added to the bottom chambers and the cells were allowed to migrate for 24 h at 37°C. At the end of the assay, the cells from the upper chamber were aspirated and the membranes were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and mounted on slides upside down. Images of eight fields were captured from each membrane (at a magnification of 20) and the number of cells in or associated with the pores was counted.

Experimental protocol for the CXCR4 antibody neutralization study

12-wk-old IFNγNOD mice were divided into two groups of eight. Rabbit IgG or a rabbit polyclonal CXCR4 neutralizing antibody (20 μg/mouse; Gonzalo et al., 2000; Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) was injected intravenously every third day for a period of 2 wk. The total number of injections per mouse was five. On day 13 of treatment, 100 μg/g BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich) was administered intraperitoneally. 15 h after the BrdU injection, pancreatic tissue was fixed in BOUIN's. Monoclonal rat anti-BrdU antibody (Accurate Chemical) was used to assess proliferation.

In pancreata from a subgroup of mice (n = 2 per group) treated with CXCR4 neutralizing antibody or control IgG, TUNEL staining was performed using the in situ cell death detection POD kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. TUNEL staining was repeated on sections from two different levels of the pancreas for each animal.

Pancreata from mice treated with IgG or CXCR4 neutralizing antibody (n = 4 per group) were evaluated for PDX1 staining using rabbit polyclonal anti-PDX1 antibody (CHEMICON International, Inc.). Images were captured from at least six ductal areas from each mouse and the PDX1-positive duct cell number and the total duct cell number in these areas were quantified. In seven of the mice from each group, the percentage of small ducts (defined as ducts comprising <15 cells) and large ducts were quantified by counting duct cells from at least 10 images captured from one hematoxylin stained section from each mouse.

Assessment of SDF-1α–stimulated Src, MAPK, and Akt phosphorylation

Freshly isolated cells from the pancreatic ductal network from IFNγNOD transgenic mice were serum-starved overnight, and stimulated with 100 or 300 ng/ml SDF-1α or 10 ng/ml EGF for 5 min at 37°C. Cells were lysed with RIPA buffer containing 20 mmol/liter Tris, pH 7.5, 1 mmol/liter EDTA, 140 mmol/liter NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mmol/liter orthovanadate, 1 mmol/liter PMSF, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin. Cell lysates were prepared for Western blot analysis. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to phospho-Src (Tyr 416), dually phosphorylated phospho-MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204), and phospho-Akt (Ser473) were used for immunodetection (Cell Signaling Technology). In a second stimulation experiment, the cells were isolated and serum starved as above and treated with 300 ng/ml SDF-1α for 0, 2, 5, 10, 30, and 60 min.

Pancreatic islets were precultured for 5–6 d before a 24-h exposure to 1,000 U/ml IFNγ (BD Biosciences) or vehicle. After exposure, the islets were homogenized in RIPA buffer, and lysates prepared for Western blot analysis and were immunoblotted with SDF-1α antibody. All membranes were stripped and reblotted with a mouse mAb to actin to confirm equal protein loading (ICN Biomedicals).

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance was used to analyze data in Fig. 5. The t test was used to analyze data in Figs. 6–9.

Acknowledgments

We thank Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for providing the CXCR4 antibody for our in vivo experiments. We would like to thank the members of the Sarvetnick Lab for critically reading this manuscript. We are grateful to Dr. Ronnda Bartel for guidance with the migration studies. We appreciate the excellent technical help of Ngan Pham-Mitchell.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health grant DK55230 to N. Sarvetnick and grants MH62231, MH62261, and NS36979 to I.L. Campbell. This is manuscript number 15665-IMM from the Scripps Research Institute.

M. Flodström-Tullberg's present address is Center for Infectious Medicine, The Karolinska Institute, SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden.

Abbreviations used in this paper: C-10, small inducible cytokine A6; Eotaxin, small inducible chemokine A 11; IP-10, IFN-γ–inducible protein 10 kD; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; MIG, monokine induced by γ IFN; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; NOD, nonobese diabetic; PDX1, pancreatic duodenal homeobox 1; RANTES, regulated on activation normal T-cell expressed and secreted; TCA-4, thymus-derived chemotactic agent 4.

References

- Aiuti, A., I.J. Webb, C. Bleul, T. Springer, and J.C. Gutierrez-Ramos. 1997. The chemokine SDF-1 is a chemoattractant for human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells and provides a new mechanism to explain the mobilization of CD34+ progenitors to peripheral blood. J. Exp. Med. 185:111–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthos, J., C. Cicala, S.M. Selig, A.A. White, H.M. Ravindranath, D. Van Ryk, T.D. Steenbeke, E. Machado, P. Khazanie, M.S. Hanback, et al. 2002. The role of the CD4 receptor versus HIV coreceptors in envelope-mediated apoptosis in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Virology. 292:98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asensio, V.C., and I.L. Campbell. 1997. Chemokine gene expression in the brains of mice with lymphocytic choriomeningitis. J. Virol. 71:7832–7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biard-Piechaczyk, M., V. Robert-Hebmann, J. Roland, N. Coudronniere, and C. Devaux. 1999. Role of CXCR4 in HIV-1-induced apoptosis of cells with a CD4+, CXCR4+ phenotype. Immunol. Lett. 70:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleul, C.C., R.C. Fuhlbrigge, J.M. Casasnovas, A. Aiuti, and T.A. Springer. 1996. A highly efficacious lymphocyte chemoattractant, stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1). J. Exp. Med. 184:1101–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boztug, K., M.J. Carson, N. Pham-Mitchell, V.C. Asensio, J. DeMartino, and I.L. Campbell. 2002. Leukocyte infiltration, but not neurodegeneration, in the CNS of transgenic mice with astrocyte production of the CXC chemokine ligand 10. J. Immunol. 169:1505–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, L.M., V.C. Asensio, L.K. Schioetz, J. Harbertson, T. Krahl, G. Patstone, N. Woolf, I.L. Campbell, and N. Sarvetnick. 1999. Islet-specific Th1, but not Th2, cells secrete multiple chemokines and promote rapid induction of autoimmune diabetes. J. Immunol. 162:2511–2520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broxmeyer, H.E., C.H. Kim, S.H. Cooper, G. Hangoc, R. Hromas, and L.M. Pelus. 1999. Effects of CC, CXC, C, and CX3C chemokines on proliferation of myeloid progenitor cells, and insights into SDF-1-induced chemotaxis of progenitors. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 872:142–162; discussion 163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broxmeyer, H.E., S. Cooper, L. Kohli, G. Hangoc, Y. Lee, C. Mantel, D.W. Clapp, and C.H. Kim. 2003. Transgenic expression of stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXC chemokine ligand 12 enhances myeloid progenitor cell survival/antiapoptosis in vitro in response to growth factor withdrawal and enhances myelopoiesis in vivo. J. Immunol. 170:421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, M.J., G.A. Arreaza, M. Grattan, C. Meagher, S. Sharif, M.D. Burdick, R.M. Strieter, D.N. Cook, and T.L. Delovitch. 2000. Differential expression of CC chemokines and the CCR5 receptor in the pancreas is associated with progression to type I diabetes. J. Immunol. 165:1102–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassatella, M.A., S. Gasperini, F. Calzetti, A. Bertagnin, A.D. Luster, and P.P. McDonald. 1997. Regulated production of the interferon-gamma-inducible protein-10 (IP-10) chemokine by human neutrophils. Eur. J. Immunol. 27:111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.C., P. Proost, C. Gysemans, C. Mathieu, and D.L. Eizirik. 2001. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 is expressed in pancreatic islets from prediabetic NOD mice and in interleukin-1 beta-exposed human and rat islet cells. Diabetologia. 44:325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirulli, V., G.M. Beattie, G. Klier, M. Ellisman, C. Ricordi, V. Quaranta, F. Frasier, J.K. Ishii, A. Hayek, and D.R. Salomon. 2000. Expression and function of α(v)β(3) and α(v)β(5) integrins in the developing pancreas: roles in the adhesion and migration of putative endocrine progenitor cells. J. Cell Biol. 150:1445–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffer, P.J., J. Jin, and J.R. Woodgett. 1998. Protein kinase B (c-Akt): a multifunctional mediator of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation. Biochem. J. 335:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colamussi, M.L., P. Secchiero, A. Gonelli, M. Marchisio, G. Zauli, and S. Capitani. 2001. Stromal derived factor-1 alpha (SDF-1 alpha) induces CD4+ T cell apoptosis via the functional up-regulation of the Fas (CD95)/Fas ligand (CD95L) pathway. J. Leukoc. Biol. 69:263–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corasaniti, M.T., S. Piccirilli, A. Paoletti, R. Nistico, A. Stringaro, W. Malorni, A. Finazzi-Agro, and G. Bagetta. 2001. Evidence that the HIV-1 coat protein gp120 causes neuronal apoptosis in the neocortex of rat via a mechanism involving CXCR4 chemokine receptor. Neurosci. Lett. 312:67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Apuzzo, M., A. Rolink, M. Loetscher, J.A. Hoxie, I. Clark-Lewis, F. Melchers, M. Baggiolini, and B. Moser. 1997. The chemokine SDF-1, stromal cell-derived factor 1, attracts early stage B cell precursors via the chemokine receptor CXCR4. Eur. J. Immunol. 27:1788–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta, S.R., H. Dudek, X. Tao, S. Masters, H. Fu, Y. Gotoh, and M.E. Greenberg. 1997. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell. 91:231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwinell, M.B., L. Eckmann, J.D. Leopard, N.M. Varki, and M.F. Kagnoff. 1999. Chemokine receptor expression by human intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 117:359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y., C.C. Broder, P.E. Kennedy, and E.A. Berger. 1996. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 272:872–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flodstrom, M., A. Maday, D. Balakrishna, M.M. Cleary, A. Yoshimura, and N. Sarvetnick. 2002. Target cell defense prevents the development of diabetes after viral infection. Nat. Immunol. 3:373–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floridi, F., F. Trettel, S. Di Bartolomeo, M.T. Ciotti, and C. Limatola. 2003. Signalling pathways involved in the chemotactic activity of CXCL12 in cultured rat cerebellar neurons and CHP100 neuroepithelioma cells. J. Neuroimmunol. 135:38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale, L.M., and S.R. McColl. 1999. Chemokines: extracellular messengers for all occasions? Bioessays. 21:17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganju, R.K., S.A. Brubaker, J. Meyer, P. Dutt, Y. Yang, S. Qin, W. Newman, and J.E. Groopman. 1998. The alpha-chemokine, stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha, binds to the transmembrane G-protein-coupled CXCR-4 receptor and activates multiple signal transduction pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 273:23169–23175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalo, J.A., C.M. Lloyd, A. Peled, T. Delaney, A.J. Coyle, and J.C. Gutierrez-Ramos. 2000. Critical involvement of the chemotactic axis CXCR4/stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha in the inflammatory component of allergic airway disease. J. Immunol. 165:499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, A.B., A.D. Luster, D.N. Posnett, and D.M. Carter. 1988. Detection of a γ interferon–induced protein IP-10 in psoriatic plaques. J. Exp. Med. 168:941–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, D., and N. Sarvetnick. 1993. Epithelial cell proliferation and islet neogenesis in IFN-g transgenic mice. Development. 118:33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, D., and N. Sarvetnick. 1994. A transgenic model for studying islet development. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 49:161–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, D., L. O'Reilly, L. Molony, A. Cooke, and N. Sarvetnick. 1995. The role of infiltrating macrophages in islet destruction and regrowth in a transgenic model. J. Autoimmun. 8:483–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbein, G., U. Mahlknecht, F. Batliwalla, P. Gregersen, T. Pappas, J. Butler, W.A. O'Brien, and E. Verdin. 1998. Apoptosis of CD8+ T cells is mediated by macrophages through interaction of HIV gp120 with chemokine receptor CXCR4. Nature. 395:189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Lopez, C., A. Varas, R. Sacedon, E. Jimenez, J.J. Munoz, A.G. Zapata, and A. Vicente. 2002. Stromal cell-derived factor 1/CXCR4 signaling is critical for early human T-cell development. Blood. 99:546–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inngjerdingen, M., K.M. Torgersen, and A.A. Maghazachi. 2002. Lck is required for stromal cell-derived factor 1 alpha (CXCL12)-induced lymphoid cell chemotaxis. Blood. 99:4318–4325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson, J., L. Carlsson, T. Edlund, and H. Edlund. 1994. Insulin-promoter-factor 1 is required for pancreas development in mice. Nature. 371:606–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, N.J., G. Kolios, S.E. Abbot, M.A. Sinai, D.A. Thompson, K. Petraki, and J. Westwick. 1999. Expression of functional CXCR4 chemokine receptors on human colonic epithelial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 104:1061–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, G., A.D. Luster, G. Hancock, and Z.A. Cohn. 1987. The expression of a γ interferon–induced protein (IP-10) in delayed immune responses in human skin. J. Exp. Med. 166:1098–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.H., and H.E. Broxmeyer. 1998. In vitro behavior of hematopoietic progenitor cells under the influence of chemoattractants: stromal cell-derived factor-1, steel factor, and the bone marrow environment. Blood. 91:100–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.H., and H.E. Broxmeyer. 1999. Chemokines: signal lamps for trafficking of T and B cells for development and effector function. J. Leukoc. Biol. 65:6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause, D.S., N.D. Theise, M.I. Collector, O. Henegariu, S. Hwang, R. Gardner, S. Neutzel, and S.J. Sharkis. 2001. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell. 105:369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritzik, M.R., E. Jones, Z. Chen, M. Krakowski, T. Krahl, A. Good, C. Wright, H. Fox, and N. Sarvetnick. 1999. PDX-1 and Msx-2 expression in the regenerating and developing pancreas. J. Endocrinol. 163:523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritzik, M.R., T. Krahl, A. Good, M. Krakowski, L. St-Onge, P. Gruss, C. Wright, and N. Sarvetnick. 2000. Transcription factor expression during pancreatic islet regeneration. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 164:99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lataillade, J.J., D. Clay, P. Bourin, F. Herodin, C. Dupuy, C. Jasmin, and M.C. Bousse-Kerdiles. 2002. Stromal cell-derived factor 1 regulates primitive hematopoiesis by suppressing apoptosis and by promoting G(0)/G(1) transition in CD34(+) cells: evidence for an autocrine/paracrine mechanism. Blood. 99:1117–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell, C.A., and G. Berton. 1998. Resistance to endotoxic shock and reduced neutrophil migration in mice deficient for the Src-family kinases Hck and Fgr. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:7580–7584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luster, A.D. 1998. Chemokines–chemotactic cytokines that mediate inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 338:436–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luster, A.D., and J.V. Ravetch. 1987. Biochemical characterization of a γ interferon–inducible cytokine (IP-10). J. Exp. Med. 166:1084–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luster, A.D., J.C. Unkeless, and J.V. Ravetch. 1985. Gamma-interferon transcriptionally regulates an early-response gene containing homology to platelet proteins. Nature. 315:672–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q., D. Jones, P.R. Borghesani, R.A. Segal, T. Nagasawa, T. Kishimoto, R.T. Bronson, and T.A. Springer. 1998. Impaired B-lymphopoiesis, myelopoiesis, and derailed cerebellar neuron migration in CXCR4- and SDF-1-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:9448–9453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majka, M., J. Ratajczak, M.A. Kowalska, and M.Z. Ratajczak. 2000. Binding of stromal derived factor-1alpha (SDF-1alpha) to CXCR4 chemokine receptor in normal human megakaryoblasts but not in platelets induces phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase p42/44 (MAPK), ELK-1 transcription factor and serine/threonine kinase AKT. Eur. J. Haematol. 64:164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino, S., K. Kunimoto, Y. Muraoka, Y. Mizushima, K. Katagiri, and Y. Tochino. 1980. Breeding of a non-obese, diabetic strain of mice. Jikken Dobutsu. 29:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, K.E., A.D. Koniski, K.M. Maltby, J.K. McGann, and J. Palis. 1999. Embryonic expression and function of the chemokine SDF-1 and its receptor, CXCR4. Dev. Biol. 213:442–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohle, R., F. Bautz, S. Rafii, M.A. Moore, W. Brugger, and L. Kanz. 1998. The chemokine receptor CXCR-4 is expressed on CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors and leukemic cells and mediates transendothelial migration induced by stromal cell-derived factor-1. Blood. 91:4523–4530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, A., B. Homey, H. Soto, N. Ge, D. Catron, M.E. Buchanan, T. McClanahan, E. Murphy, W. Yuan, S.N. Wagner, et al. 2001. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 410:50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.M., M. Baggiolini, I.F. Charo, C.A. Hebert, R. Horuk, K. Matsushima, L.H. Miller, J.J. Oppenheim, and C.A. Power. 2000. International union of pharmacology. XXII. Nomenclature for chemokine receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 52:145–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa, T., T. Nakajima, K. Tachibana, H. Iizasa, C.C. Bleul, O. Yoshie, K. Matsushima, N. Yoshida, T.A. Springer, and T. Kishimoto. 1996. Molecular cloning and characterization of a murine pre-B-cell growth-stimulating factor/stromal cell-derived factor 1 receptor, a murine homolog of the human immunodeficiency virus 1 entry coreceptor fusin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:14726–14729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Laughlin-Bunner, B., N. Radosevic, M.L. Taylor, Shivakrupa, C. DeBerry, D.D. Metcalfe, M. Zhou, C. Lowell, and D. Linnekin. 2001. Lyn is required for normal stem cell factor-induced proliferation and chemotaxis of primary hematopoietic cells. Blood. 98:343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offield, M.F., T.L. Jetton, P.A. Labosky, M. Ray, R.W. Stein, M.A. Magnuson, B.L. Hogan, and C.V. Wright. 1996. PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development. 122:983–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, R., S. Leyvraz, and L. Perey. 1998. Apoptotic regulation in primitive hematopoietic precursors. Blood. 92:2041–2052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochazka, M., H.R. Gaskins, L.D. Shultz, and E.H. Leiter. 1992. The nonobese diabetic scid mouse: model for spontaneous thymomagenesis associated with immunodeficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:3290–3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff, R.M., T.A. Hamilton, M. Tani, M.H. Stoler, H.E. Shick, J.A. Major, M.L. Estes, D.M. Thomas, and V.K. Tuohy. 1993. Astrocyte expression of mRNA encoding cytokines IP-10 and JE/MCP-1 in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. FASEB J. 7:592–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, D., and A. Zlotnik. 2000. The biology of chemokines and their receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:217–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarvetnick, N., D. Liggitt, S.L. Pitts, S.E. Hansen, and T.A. Stewart. 1988. Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus induced in transgenic mice by ectopic expression of class II MHC and interferon-gamma. Cell. 52:773–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarvetnick, N., J. Shizuru, D. Liggitt, L. Martin, B. McIntyre, A. Gregory, T. Parslow, and T. Stewart. 1990. Loss of pancreatic islet tolerance induced by beta-cell expression of interferon-gamma. Nature. 346:844–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauty, A., M. Dziejman, R.A. Taha, A.S. Iarossi, K. Neote, E.A. Garcia-Zepeda, Q. Hamid, and A.D. Luster. 1999. The T cell-specific CXC chemokines IP-10, Mig, and I-TAC are expressed by activated human bronchial epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 162:3549–3558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack, J.M. 1995. Developmental biology of the pancreas. Development. 121:1569–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana, K., S. Hirota, H. Iizasa, H. Yoshida, K. Kawabata, Y. Kataoka, Y. Kitamura, K. Matsushima, N. Yoshida, S. Nishikawa, et al. 1998. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is essential for vascularization of the gastrointestinal tract. Nature. 393:591–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahakis, S.R., A. Villasis-Keever, T. Gomez, M. Vanegas, N. Vlahakis, and C.V. Paya. 2002. G protein-coupled chemokine receptors induce both survival and apoptotic signaling pathways. J. Immunol. 169:5546–5554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, D.E., E.P. Bowman, A.J. Wagers, E.C. Butcher, and I.L. Weissman. 2002. Hematopoietic stem cells are uniquely selective in their migratory response to chemokines. J. Exp. Med. 195:1145–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Q., R.W. Compans, and C. Chen. 2001. HIV envelope proteins differentially utilize CXCR4 and CCR5 coreceptors for induction of apoptosis. Virology. 285:128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakeri, Z., and R.A. Lockshin. 2002. Cell death during development. J. Immunol. Methods. 265:3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.R., A.H. Kottmann, M. Kuroda, I. Taniuchi, and D.R. Littman. 1998. Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and in cerebellar development. Nature. 393:595–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]