Abstract

We find that Bax, a proapoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family, translocates to discrete foci on mitochondria during the initial stages of apoptosis, which subsequently become mitochondrial scission sites. A dominant negative mutant of Drp1, Drp1K38A, inhibits apoptotic scission of mitochondria, but does not inhibit Bax translocation or coalescence into foci. However, Drp1K38A causes the accumulation of mitochondrial fission intermediates that are associated with clusters of Bax. Surprisingly, Drp1 and Mfn2, but not other proteins implicated in the regulation of mitochondrial morphology, colocalize with Bax in these foci. We suggest that Bax participates in apoptotic fragmentation of mitochondria.

Introduction

Proapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family, Bax and Bak, are essential for many pathways of programmed cell death (Wei et al., 2001). Bax is cytosolic, whereas Bak circumscribes the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM)* in healthy cells and upon the initiation of apoptosis they coalesce together into punctate foci on the surface of mitochondria (Hsu et al., 1997; Nechushtan et al., 2001). Interaction of Bax with components of the permeability transition pore (for review see Desagher and Martinou, 2000) has suggested that induction of permeability transition and mitochondrial swelling are the underlying mechanisms of apoptosis induction. An alternative model, supported by results obtained with artificial membranes, is that Bax directly forms pores (Antonsson et al., 1997; Schlesinger et al., 1997; Basanez et al., 1999) that allow proteins to escape from the mitochondria (Goldstein et al., 2000) into the cytosol to initiate apoptosis.

Recently, mitochondrial fission has been reported to occur during apoptosis induced by a variety of unrelated stimuli (Mancini et al., 1997; Desagher and Martinou, 2000; Chen et al., 2001; Frank et al., 2001; Pinton et al., 2001) and truncated Bid induces morphological remodeling of mitochondrial cristae (Scorrano et al., 2002).

Maintenance of mitochondrial shape depends on the balance between fusion and fission events and is controlled by several proteins, including dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) (Otsuga et al., 1998; Labrousse et al., 1999) and Mfn2 (Santel and Fuller, 2001).

Here we explore the relationship between Bax foci on mitochondria and mitochondrial scission machinery during the progression of apoptosis.

Results and discussion

Bax localizes at the tips, constriction sites, and scission foci of mitochondria in apoptotic cells

We explored Bax translocation and foci formation during the mitochondrial fragmentation process that frequently occurs during apoptosis. After treatment with the broad specificity kinase inhibitor staurosporine (STS), focal clusters of endogenous Bax were detected with the anti-Bax 6A7 antibody (Nechushtan et al., 1999). In some cells endogenous Bax clusters were located at the tips or along the edges of elongated tubular mitochondria typical of healthy cells (Fig. 1). Bax foci were also present at mitochondrial constriction sites, separating elongated mitochondria into several shorter units (Fig. 1 A, arrowheads). Similar results were obtained in the presence and absence of the broad specificity caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk, indicating that Bax translocation and foci formation are early apoptotic events, upstream of caspase activation. The same results were obtained with STS-treated Cos-7 cells (Fig. 1 B) and HeLa cells (unpublished data) cotransfected with CFP-Bax and mito-YFP.

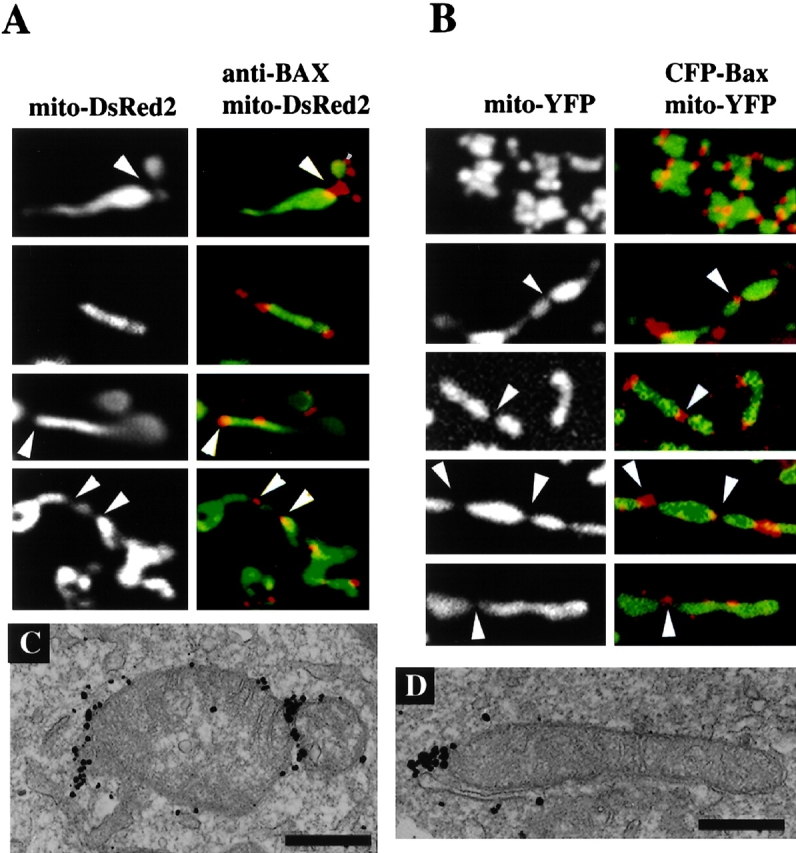

Figure 1.

Localization of Bax clusters on mitochondria in apoptotic Cos-7 cells. (A) Cells transfected with mito-DsRed2 (green) were treated with 1 μM STS for 6 h, fixed, stained with anti-Bax 6A7 mAb (red), and analyzed by confocal microscopy. (B) Cells were cotransfected with CFP-Bax and mito-YFP. At 12 h after transfection, cells were treated with 1 μM STS for 90 min and examined by confocal microscopy. Each field illustrates one of the typical morphologies of mitochondria (green) and Bax foci (red) in apoptotic Cos-7 cells. Bax associates with mitochondrial constriction sites (arrowheads) or at the tips of tubular elongated mitochondria and appositions of mitochondria. (C and D) Cos-7 cells were treated with 1 μM STS and analyzed by electron microscopy after staining endogenous Bax (C) or CFP-Bax (D) with anti-Bax 6A7 mAb and anti-GFP mAb, respectively, and processing by silver-enhancement of immunogold labeling. In dying cells, endogenous Bax localized to mitochondrial tips and constriction sites. Bars, 0.5 μm.

The submitochondrial localization of complexes of endogenous Bax (Fig. 1 C) or overexpressed CFP-Bax (Fig. 1 D) at tips and constriction sites of mitochondria was also detected by electron microscopy of apoptotic Cos-7 cells. Although the localization of Bax to mitochondrial scission sites was not previously recognized, examination of previously published electron micrographs (Nechushtan et al., 2001) reveals that both endogenous and overexpressed Bax localize to mitochondrial tips in Fig. 2, D and E, and constriction sites in Fig. 2, D and I, of that paper.

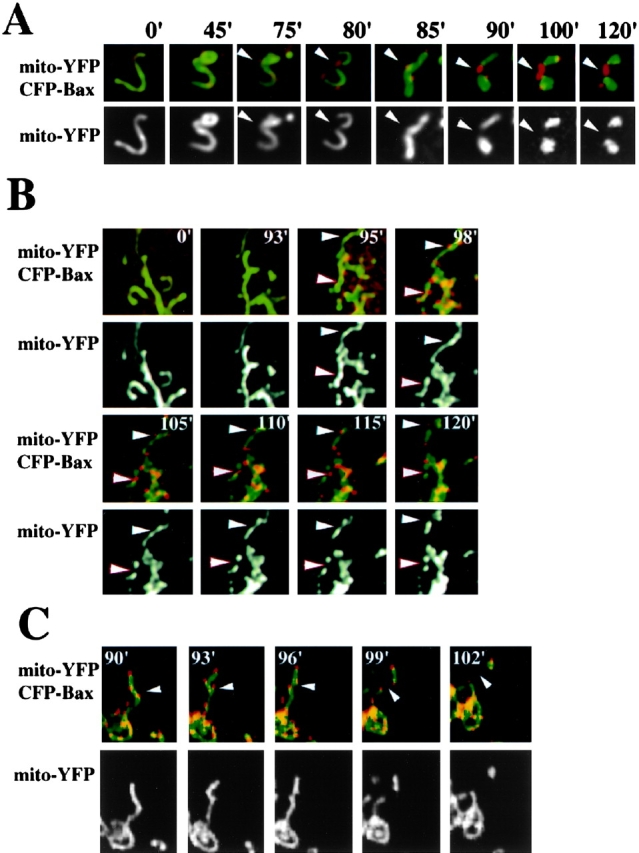

Figure 2.

Apoptotic Bax clusters colocalize with sites of mitochondrial fragmentation. HeLa (A and B) and Cos-7 (C) cells were cotransfected with CFP-Bax and mito-YFP. At 12 h after transfection cells were treated with 1 μM STS and analyzed by confocal microscopy over time. Fragmentation and vesiculation of mitochondria began at the same time (between 75 and 80 min in A) that Bax (red) coalesced at mitochondrial scission sites (arrowheads). Fragmented mitochondria often remained connected by Bax-containing structures (A and B). Complete separation of fragmented mitochondria was also detected (C).

We examined the time sequence of Bax foci localization during mitochondrial scission events. HeLa (Fig. 2, A and B) and Cos-7 (Fig. 2 C) cells were cotransfected with CFP-Bax and mito-YFP constructs, treated with STS and analyzed by confocal microscopy over time. CFP-Bax clusters became detectable between 60–120 min after addition of STS, immediately preceding major changes in the morphology of mitochondria (Fig. 2, A and B). In most cases Bax coalesced at sites where mitochondrial scission subsequently occurred, although some sites of Bax coalescence did not sever in the time frame examined (Fig. 2, B and C). However, all productive scission events had CFP-Bax aggregates associated with them (Fig. 2, A–C). In those instances in which the severed mitochondria moved apart, CFP-Bax clusters remained attached to both tips of the newly formed organelles at the scission site (Fig. 2 C). These observations suggest that Bax may participate in the severing of mitochondria that occurs during apoptosis. Consistent with this model, Bcl-XL inhibited STS-induced clustering of Bax on mitochondria (Nechushtan et al., 2001), mitochondrial fragmentation (unpublished data), and apoptosis (Boise et al., 1993).

Effect of Drp1K38A on Bax dynamics in apoptotic cells

The dominant negative inhibitor of Drp1, Drp1K38A, was shown to inhibit the mitochondrial fragmentation occurring during apoptosis induced by various stimuli (Frank et al., 2001). We explored the effect of Drp1K38A on Bax translocation, foci formation, and on mitochondrial scission.

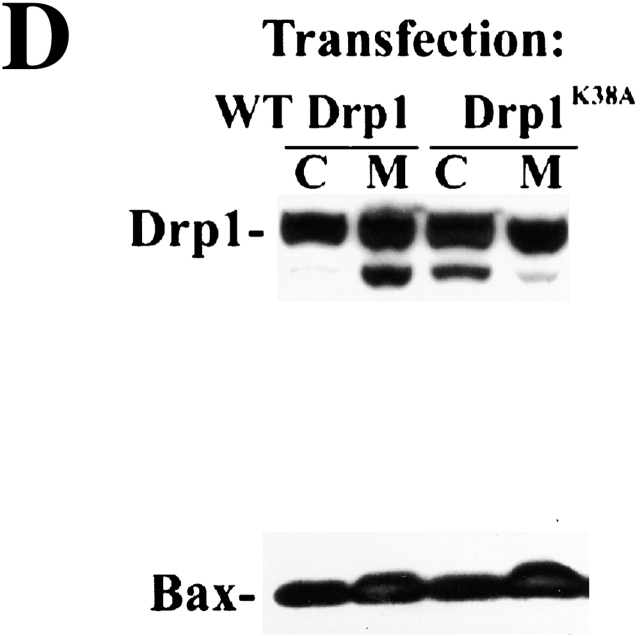

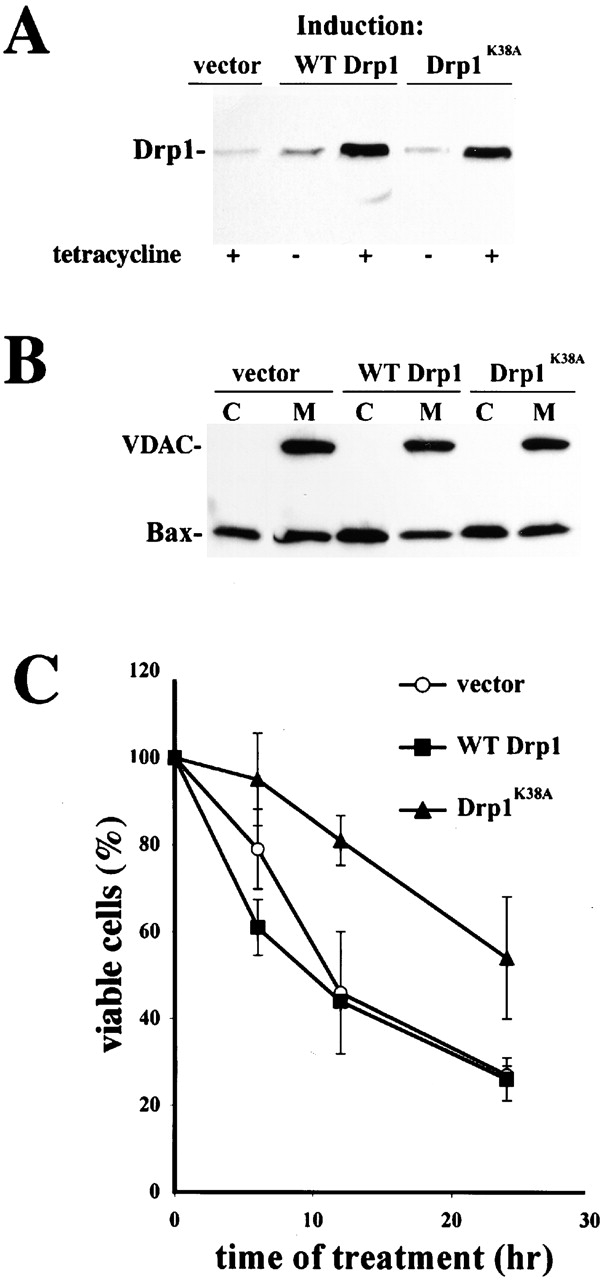

We analyzed the effect of Drp1K38A expression on mitochondrial Bax translocation using HeLa cells in which expression of WT Drp1 (T-Rex-Drp1) and Drp1K38A (T-Rex-Drp1K38A) is controlled by tetracycline (Fig. 3 A). Tetracycline-treated T-Rex-Drp1, T-Rex-Drp1K38A, and control vector–transfected cells (T-Rex-V) were incubated with STS for 5 h, fractionated, and analyzed by Western Blotting for mitochondrial translocation of Bax. Drp1K38A did not inhibit mitochondrial translocation of Bax (Fig. 3 B). However, T-Rex- Drp1K38A cells were more resistant to apoptosis induced by STS than T-Rex-V or T-Rex-Drp1 cells (Fig. 3 C). Drp1K38A also did not inhibit Bax translocation to membranes in Cos-7 cells transiently cotransfected with Bax and Drp1K38A (Fig. 3 D).

Figure 3.

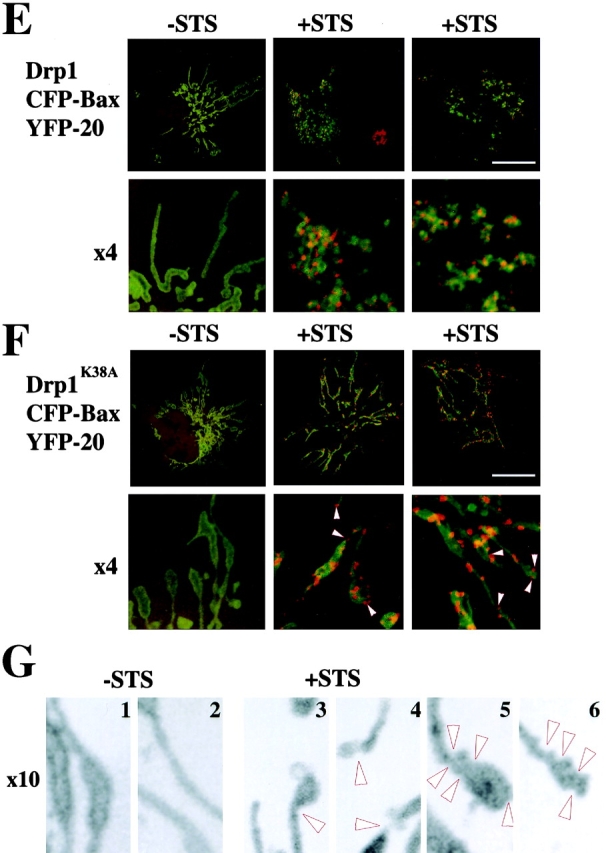

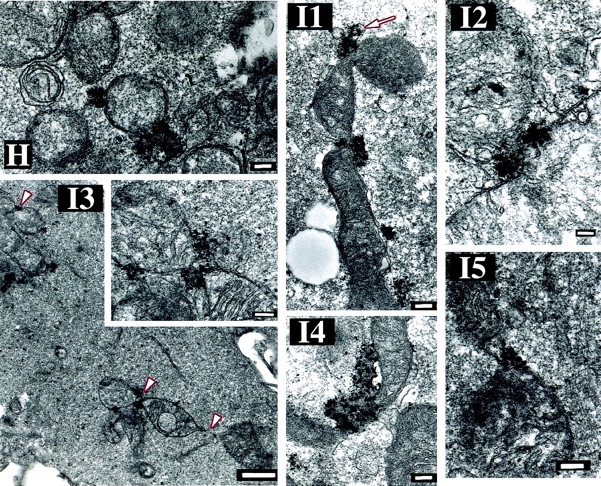

Drp1K38A cause accumulation of Bax-associated fission intermediates. (A) Induction of WT Drp1 and Drp1K38A. T-Rex- Drp1, T-Rex- Drp1K38A, and T-Rex-V cells were treated with 1 μg/ml of tetracycline for 24 h and analyzed for expression of WT Drp1, Drp1K38A by Western Blotting. (B) T-Rex- Drp1, T-Rex- Drp1K38A, and T-Rex-V cells were treated with 1 μg/ml of tetracycline for 24 h and then treated with 1 μM STS for 5 h, and analyzed for the translocation of Bax to the membranes by Western Blotting. (C) Viability T-Rex- Drp1, T-Rex- Drp1K38A, and T-Rex-V was assayed as described in Materials and methods. Data represent the mean ± SD of two experiments with the starting number of 100 cells per field. Two fields per sample were counted at each time point. (D) Cos-7 cells were cotransfected with pcDNA 3.1-Drp1 and pcDNA 3.1-Bax or pcDNA3.1- Drp1K38A and pcDNA 3.1-Bax (ratios 3:1), treated with 1 μM STS for 2 h and, after cell fractionation, heavy membrane fractions and cytosols were analyzed by Western Blotting. (E and F) Cells were transfected with CFP-Bax, YFP-20, and pcDNA3.1-Drp1 (E), or CFP-Bax, YFP-20, and pcDNA3.1-Drp1K38A (F) (ratio 2:0.5:6), treated with 1 μM STS for 90 min and analyzed with confocal microscopy. Arrowheads indicate invaginations of OMM; possibly representing fission intermediates localized with CFP-Bax clusters. Bars, 20 μm. (G) High magnification of some mitochondria from F (G1 and G2, control; G3–6, STS-treated cells). Arrowheads show the sites where Bax clusters localize, which may represent early fission sites. (H and I) Cells were transfected with CFP-Bax and pcDNA3.1-Drp1 (H) or CFP-Bax and pcDNA3.1-Drp1K38A (I), treated with 1 μM STS for 90 min and analyzed for submitochondrial localization of Bax clusters by electron microscopy. Arrow in I1 points to membrane vesiculations associated with Bax clusters. Arrowheads in I3 point to constriction sites associated with Bax clusters. Bars: (H, I1, I3 insert, I4, I5) 0.2 μm, (I2) 0.1 μm, (I3) 1 μm.

We also examined the effect of Drp1K38A on Bax translocation by confocal microscopy. Cells were cotransfected with CFP-Bax, a marker of the OMM, YFP-20 (Nechushtan et al., 2001), and Drp1, or CFP-Bax, YFP-20, and Drp1K38A and then treated with STS. As shown in Fig. 3, E and F, Drp1K38A did not inhibit formation of Bax clusters, consistent with the results of Western blotting in Fig. 3, B and D. However, in cells overexpressing Drp1K38A (Fig. 3 F), Bax translocation and cluster formation did not correlate with changes in the gross morphology of mitochondria, in contrast to cells overexpressing WT Drp1 and Bax (Fig. 3 E). Invaginations and/or vesiculations of the OMM were spatially associated with CFP-Bax in the presence of Drp1K38A (Fig. 3 G, arrowheads), suggesting an increase in membrane dynamics in the areas containing Bax or aberrant mitochondrial scission attempts.

To obtain high-resolution images of the effect of Drp1K38A on the spatial distribution of Bax, Cos-7 cells were cotransfected with Drp1K38A or WT Drp1 and CFP-Bax, treated with STS, stained with anti-GFP antibodies, and analyzed by electron microscopy (Fig. 3, H and I). In cells expressing WT Drp1, Bax clusters were tightly associated to one or two round mitochondria (Fig. 3 H). In cells overexpressing Drp1K38A (Fig. 3 I, 1–5), mitochondria containing multiple clusters of Bax were detected as seen by confocal microscopy (Fig. 3 F). In the presence of Drp1K38A, Bax clusters were detected in two predominant localizations; bud-like complexes associated with the OMM and mitochondrial constriction sites. These Bax foci are clearly delineated and more electron dense, indicating a higher protein concentration than the surrounding cytoplasm, and occasionally are associated with membrane vesicles (Fig. 3 I, 1, arrow).

Analysis of the submitochondrial localization and spatial relation of proteins implicated in the regulation of mitochondrial morphology to the Bax-foci

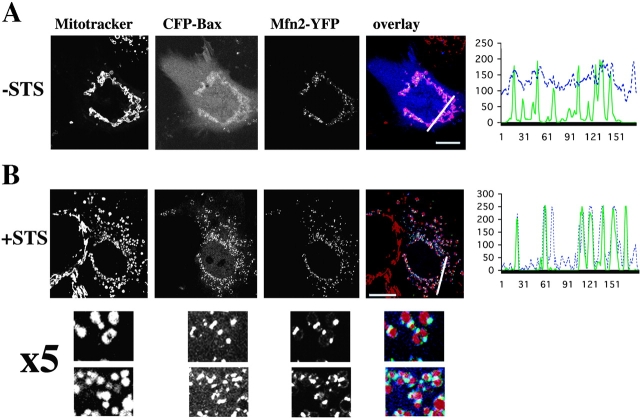

To assess the possible participation in the apoptotic fission foci of proteins having proven or potential roles in the regulation of mitochondrial morphology in mammals, we analyzed the submitochondrial localizations of: Mfn2 (Santel and Fuller, 2001), Drp1 (Smirnova et al., 1998), a human homologue of Fis1 (Mozdy et al., 2000), human OMP25, and synaptojanin 2A (Nemoto and De Camilli, 1999). YFP-Fis1 and YFP-OMP25 circumscribed mitochondria completely in healthy cells, whereas YFP-synaptojanin 2A was mostly cytosolic. Their localization did not change upon induction of apoptosis (unpublished data). We also did not detect submitochondrial foci formation in either healthy or apoptotic cells by the members of the Bcl-2 family, Bad, Bid and Bcl-XL (unpublished data; Nechushtan et al., 2001). However, Mfn2-YFP formed mitochondria-associated clusters (Fig. 4 A; Online supplemental material) that colocalized with CFP-Bax upon induction of apoptosis (Fig. 4 B). Almost complete colocalization of clusters of Mfn2-YFP with CFP-Bax was detected in apoptotic cells. 92% ± 10.5% of Mfn2 clusters (n = 847) colocalized with Bax clusters and 68% ± 10% of Bax clusters (n = 1,238) colocalized with Mfn2 clusters. Endogenous Mfn2 was also found to colocalize with endogenous Bax in primary human myocytes (see Online supplemental material). Bak, the closest Bax homologue in the Bcl-2 family, which colocalized with Bax foci in apoptotic cells (Nechushtan et al., 2001) was also found to colocalize with Mfn2 in apoptotic cells (see Online supplemental material, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200209124/DC1).

Figure 4.

Mfn2 protein forms mitochondria-associated punctate foci that colocalize with Bax during apoptosis. Cos-7 cells were cotransfected with CFP-Bax (blue) and Mfn2-YFP (green), incubated without (A) and with (B) 1 μM STS for 90 min, and analyzed by confocal microscopy after staining with Mitotracker CMXRos (red). In untreated cells (A) Bax is mostly cytosolic and Mfn2 is concentrated in punctate mitochondrial foci. In apoptotic cells (B) Bax localizes to foci containing Mfn2. The line scans plot the intensity of CFP-Bax (blue) and Mfn2-YFP (green). Bars, 20 μm.

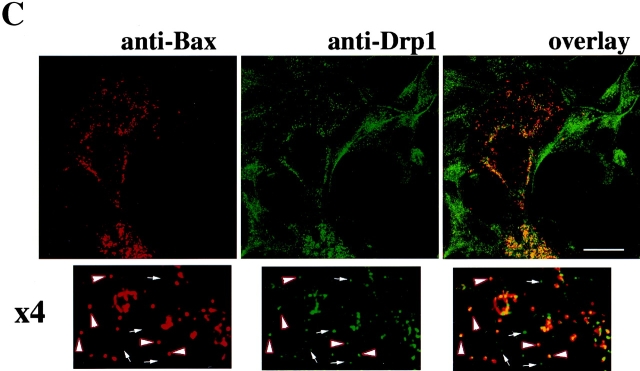

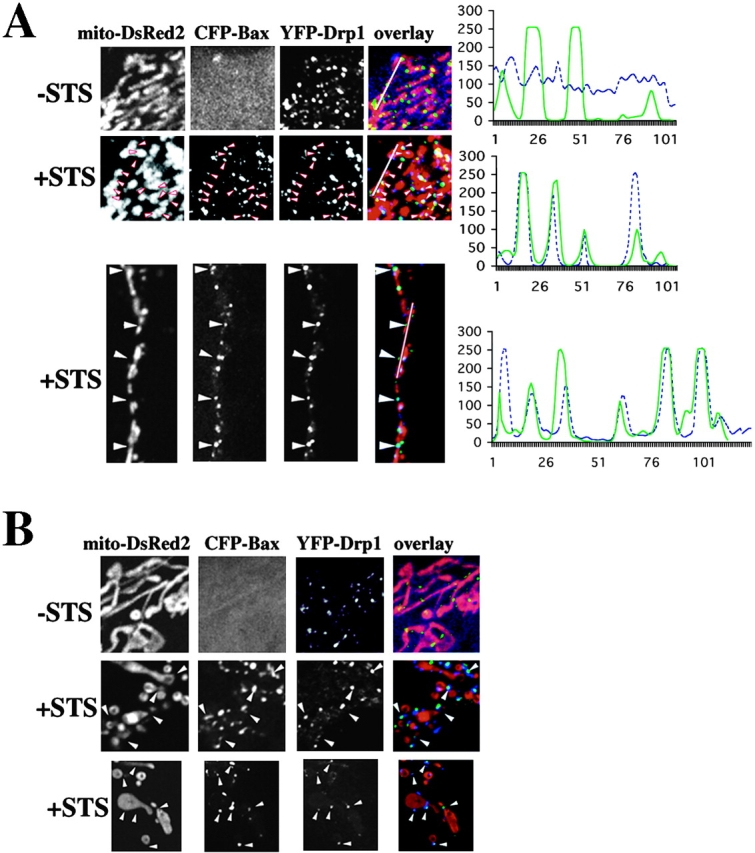

Scission of mitochondria is preceded by formation of Drp1-containing foci at sites of subsequent scission (Labrousse et al., 1999). We examined the spatial relationship between Bax and Drp1 in healthy and apoptotic cells. Cos-7 and HeLa cells were cotransfected with CFP-Bax, YFP-Drp1, and mito-DsRed2, treated with STS, and analyzed by confocal microscopy. In healthy cells, Bax did not colocalize with foci of Drp1 on mitochondria (Fig. 5 A, top row). Upon treatment of HeLa (Fig. 5 A) or Cos-7 cells (Fig. 5 B) with STS, CFP-Bax relocalized into foci containing YFP-Drp1.

Figure 5.

Upon induction of apoptosis Bax localizes to mitochondrial foci containing Drp1. HeLa (A) and Cos-7 (B) cells were triple-transfected with CFP-Bax (blue), YFP-Drp1 (green), and mito-DsRed2 (red). At 12 h after transfection, cells were treated with 1 μM STS to induce apoptosis and analyzed by confocal microscopy over time. The same field of the cell was analyzed before (−STS) and after (+STS) Bax translocation/clustering (A, top). The bottom panel in A shows an independent example of CFP-Bax and YFP-Drp1 localization. The line scans plot the intensity of CFP-Bax (blue) and YFP-Drp1 (green). Colocalization of Bax with Drp1 at the mitochondrial foci is apparent in apoptotic cells. (B) Localization of CFP-Bax (blue) and YFP-Drp1 (green) in healthy (−STS) and apoptotic Cos-7 cells (+STS). The mitochondrial matrix is marked with mito-DsRed2 (red). CFP-Bax and YFP-Drp1 colocalize in clusters on mitochondria (cyan in overlay). (C) Colocalization of endogenous Bax and Drp1 in apoptotic cells. Cos-7 cells were treated for 6 h with 1 μM STS in the presence of zVAD-fmk. Cells were stained with anti-Bax 6A7 mAb (red), and anti-Drp1 polyclonal antibodies (green). Arrowheads point to some of the foci where endogenous Bax and Drp1 colocalize. Arrows shows some of the Drp1 foci, which do not colocalize with Bax, and may represent the nonmitochondrial subpopulation of Drp1 (Yoon et al., 1998). Bar, 20 μm.

Endogenous Drp1 also colocalized with endogenous Bax after induction of apoptosis with STS, actinomycin D and etoposide in Cos-7 cells (Fig. 5 C; Online supplemental material) and primary human fibroblasts treated with actinomycin D or etoposide (see Online supplemental material, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200209124/DC1). Thus, two proteins that participate in the mitochondrial fission (Drp1) and fusion (Mfn2) colocalize with Bax in foci.

These results suggest that Bax may participate with the mitochondrial fission apparatus to promote apoptosis. Previous results leading to other models of Bax activity could be consistent with the mitochondrial fission model. Bax was found to form channels in membranes that suggested a mechanism of the OMM permeabilization through Bax oligomeric pores. However, detailed analysis shows that Bax forms a lipidic pore (Basanez et al., 1999), most similar to the type of pore formed during membrane fusion events (Zimmerberg et al., 1993), suggesting that the cell-free pore assay may be revealing how Bax participates in mitochondrial fusion and fission events. Although Bax pore–forming activity may be related to fission activity, further work is needed to interpret the biological significance of Bax localization with the mitochondrial fission process.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Cos-7, HeLa cells (American Type Culture Collection) and primary human fibroblasts were grown as described (Frank et al., 2001). Human myocytes were obtained by biopsy and cultured as described previously (Semino-Mora et al., 1997).

Generation of cell lines expressing tetracycline-inducible WT Drp1 and Drp1K38A

A tetracycline-regulated expression system (T-Rex system; Invitrogen) was used. cDNAs of WT Drp1 and Drp1K38A were cloned into pcDNA 4/TO. The pcDNA4/TO constructs were transfected into a HeLa cell line stably expressing the Tet repressor from pcDNA6/TR plasmid (T-Rex-HeLa). T-Rex-HeLa cell lines stably expressing tetracycline-inducible WT Drp1 and Drp1K38A in pcDNA4/TO were generated by dual selection using zeocin (100 μg/ml) and blasticidin (5 μg/ml). The expression levels of WT Drp1 and Drp1K38A were assayed by Western Blotting at 24 h after addition of tetracycline (1 μg/ml). Clones that showed high, comparable expression levels of WT Drp1 and Drp1K38A and tight control by tetracycline were used in this study.

Expression plasmids and transfections

Bax linked to cyan fluorescent protein (CFP-Bax), and the marker of the OMM, 20 amino acids from the COOH terminus of Bax linked to yellow fluorescent protein (YFP-20) were described previously (Nechushtan et al., 1999). Mfn2-YFP was constructed from the GFP construct described previously (Santel and Fuller, 2001). Drp1 and Drp1K38A expression vectors were described previously (Smirnova et al., 1998; Frank et al., 2001). Drp1 was recloned into pEYFP-C1 to yield pEYFP-Drp1 (YFP-Drp1).

Human homologues of Fis1 (Mozdy et al., 2000), OMP 25, and synaptojanin 2A (Nemoto and De Camilli, 1999) were cloned from fetal human brain mRNA (Stratagene) using RT-PCR, and sub-cloned into pEYFP-C1 vectors (BD Biosciences). Mito-YFP (BD Biosciences) and mito-DsRed2 (BD Biosciences) revealed mitochondria.

Cells were transfected using the FuGENE 6 (Roche) and treated as indicated in individual experiments, 12–15 h later.

Confocal microscopy

Images were captured with an LSM 510 microscope using a 63× 1.4 NA Apochromat objective (ZEISS). The excitation wavelengths for CFP, YFP, DsRed2, or Mitotracker Red CMXRos (Molecular Probes, Inc.) were 413, 514, and 543 nm, respectively.

In some experiments signal intensities from each channel were reconstructed by plotting pixel values of each channel along lines drawn through optical sections. Multichannel images were separated into single channels and exported to the National Institutes of Health image software. Measurements of the pixel intensities were made along the lines shown in the respective picture. Numbers obtained were plotted against the position on the line using Microsoft Excel.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells grown in 2-well chamber slides were treated as indicated, fixed with cold acetone:methanol (1:1) for 4 min at −20°C, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.05% deoxycholate in PBS for 20 min at RT and then blocked with 3% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 45 min at RT. Cells were probed with mouse anti-Bax (6A7) mAb (Hsu and Youle, 1998), affinity-purified anti–human Mfn2 antibodies, affinity-purified anti–human Drp1 polyclonal antibodies (Frank et al., 2001). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific to Mfn2 protein (unpublished data) were raised against an internal peptide sequence ((C)-KNSRRALMGYNDQVQRPIPLTPAN) by Zymed Laboratories. Mitochondria were stained with anti-mitofilin mAb (Oncogene). Next, cells were washed with PBS, stained with goat anti–mouse Alexa Fluor 488 and goat anti–rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 antibodies (Molecular Probes, Inc.) washed, mounted with SlowFade Light Antifade kit (Molecular Probes, Inc.), and analyzed by confocal microscopy. In some experiments mitochondria were stained with 200 nM Mitotracker CMXRos (Molecular Probes, Inc.) for 30 min before fixation.

Electron microscopy

For detection of endogenous or overexpressed Bax, the anti-Bax (6A7) or anti-GFP–derived color variant proteins, 3E6 anti-AFP (Qbiogene) antibodies were used for preembedding immuno-EM as described previously (Nechushtan et al., 2001).

Cell fractionation and immunoblotting

Cells were scraped, washed in PBS and resuspended in lysis buffer (10 mM Hepes/KOH, pH 7.4, 38 mM NaCl supplemented with 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 μg/ml leupeptin). Cells homogenized and centrifuged at 2,000 g for 10 min to remove unbroken cells and nuclei. The supernatant was centrifuged at 13,000 g for 15 min and the pellet was used as the membrane fraction and the supernatant as a cytosol. For total extracts, cells were scrapped, washed with PBS, and resuspended in SDS PAGE sample buffer. An aliquot of the sample was taken to determine protein concentration. Proteins were separated on 10%-20% gradient polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen), transferred onto PVDF membranes (Immobilon-P; Millipore) and incubated with anti-Bax mAb (clone 1F6; Hsu and Youle, 1998) or anti-Drp1 mAb (clone 8; BD Transduction Laboratories) followed by HRP-conjugated anti–mouse secondary antibody. Blots were detected by the ECL (Amersham Biosciences).

Cell viability

T-Rex-Drp1, T-Rex-Drp1K38A, and T-Rex-V cells were seeded on 2-well chambers (Nunc) containing 55 μm CELLocate microgrid coverslips (Eppendorf). After treatment with tetracycline (1 μg/ml) for 24 h then 1 μM STS, the number of attached cells was scored in the same fields at the indicated time points.

Online supplemental material

The online supplemental material for this paper can be found at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200209124/DC1. Fig. S1 shows submitochondrial localization of Mfn2 protein. Fig. S2 shows colocalization of Mfn2-YFP and CFP-Bak in STS-treated Cos-7 cells. Fig. S3 shows colocalization of endogenous Bax and endogenous Drp1 in actinomycin D– or etoposide-treated Cos-7 cells. Fig. S4 shows colocalization of endogenous Bax and endogenous Drp1 in actinomycin D– or etoposide-treated human fibroblasts.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank J. Barrick for technical assistance, V. Tanner Crocker and S. Chang for assistance with EM, R. Raju and M. Dalakas for primary human myocytes, C. Blackstone for critical reading of the manuscript, A. van der Bliek for Drp1 constructs, and M. Suzuki for the human Fis1 clone.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, and a generous gift from MitoKor to M.T. Fuller.

The online version of this paper contains supplemental material.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: OMM, outer mitochondrial membrane; STS, staurosporine.

References

- Antonsson, B., F. Conti, S. Montessuit, S. Lewis, I. Martinou, L. Bernasconi, A. Bernard, J.J. Mermod, G. Mazzei, K. Maundrell, et al. 1997. Inhibition of Bax channel-forming activity by Bcl-2. Science. 277:370–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basanez, G., A. Nechushtan, O. Drozhinin, A. Chanturiya, E. Choe, S. Tutt, K. Wood, Y.-T. Hsu, J. Zimmerberg, and R.J. Youle. 1999. Full length Bax disrupts planar phospholipid membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:5492–5497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boise, L.H., M. Gonzlez-Garcia, C.E. Postema, L. Ding, T. Lindsten, L. Turka, X. Mao, G. Nunez, and C.B. Thompson. 1993. Bcl-XL, a bcl-2 related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 74:597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W., P.A. Calvo, D. Malide, J. Gibbs, U. Schubert, I. Bacik, S. Basta, R. O'Neill, J. Schickli, P. Palese, et al. 2001. A novel influenza A virus mitochondrial protein that induces cell death. Nat. Med. 7:1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desagher, S., and J.C. Martinou. 2000. Mitochondria as the central control point of apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 10:369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, S., B. Gaume, E.S. Bergmann-Leitner, W.W. Leitner, E.G. Robert, F. Catez, C.L. Smith, and R.J. Youle. 2001. The role of Dynamin-Related Protein-1, a mediator of mitochondrial fission, in apoptosis. Dev. Cell. 1:515–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, J.C., N.J. Waterhouse, P. Juin, G.I. Evan, and D.R. Green. 2000. The coordinate release of cytochrome c during apoptosis is rapid, complete and kinetically invariant. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Y.-T., K. Wolter, and R.J. Youle. 1997. Cytosol to membrane redistribution of members of the Bcl-2 family during apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:3668–3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Y.-T., and R.J. Youle. 1998. Bax in murine thymus is a soluble monomeric protein which displays differential detergent-induced conformations. J. Biol. Chem. 273:10777–10783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrousse, A.M., M.D. Zappaterra, D.A. Rube, and A.M. van der Bliek. 1999. C. elegans dynamin-related protein DRP1 controls severing of the mitochondrial outer membrane. Mol. Cell. 4:815–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, M., B.O. Anderson, E. Caldwell, M. Sedghinasab, P.B. Paty, and D.M. Hockenbery. 1997. Mitochondrial proliferation and paradoxical membrane depolarization during terminal differentiation and apoptosis in a human colon carcinoma cell line. J. Cell Biol. 138:449–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozdy, A.D., J.M. McCaffery, and J.M. Shaw. 2000. Dnm1p GTPase-mediated mitochondrial fisson is a multi-step process requiring the novel integral membrane component Fis1p. J. Cell Biol. 151:367–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechushtan, A., C.L. Smith, Y.-T. Hsu, and R.J. Youle. 1999. Conformation of the Bax C-terminus regulates subcellular location and cell death. EMBO J. 18:2330–2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechushtan, A., C.L. Smith, S.H. Yoon, and R.J. Youle. 2001. Bax and Bak coalesce into novel mitochondria-associated clusters during apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 153:1265–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto, Y., and P. De Camilli. 1999. Recruitment of an alternatively spliced form of synaptojanin 2 to mitochondria by the interaction with the PDZ domain of a mitochondrial outer membrane protein. EMBO J. 18:2991–3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuga, D., B.K. Keegan, E. Brish, J.W. Thatcher, G.J. Hermann, W. Bleazard, and J.M. Shaw. 1998. The dynamin-related GTPase, Dnm1p, controls mitochondrial morphology in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 143:333–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinton, P., D. Ferrari, E. Rapizzi, F. Di Virgilio, T. Pozzan, and R. Rizzuto. 2001. The Ca2+ concentration of the endoplasmic reticulum is a key determinant of ceramide-induced apoptosis: significance for the molecular mechanism of Bcl-2 action. EMBO J. 20:2690–2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santel, A., and M.T. Fuller. 2001. Control of mitochondrial morphology by a human mitofusin. J. Cell Sci. 114:867–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger, P.H., A. Gross, X.M. Yin, K. Yammamoto, M. Saito, G. Waksman, and S.J. Korsmeyer. 1997. Comparison of the ion channel characteristics of proapoptotic BAX and antiapoptotic BCL-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:11357–11362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scorrano, L., M. Ashiya, K. Buttle, S. Weiller, S.A. Oakes, C.A. Mannella, and S.J. Korsmeyer. 2002. A distinct pathway remodels mitochondrial cristae and mobilizes cytochrome c during apoptosis. Dev. Cell. 2:55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semino-Mora, C., M. Leon-Monzon, and M.C. Dalakas. 1997. Mitochondrial and cellular toxicity induced by fialuridine in human muscle in vitro. Lab. Invest. 76:487–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnova, E., D.-L. Shurland, S.N. Ryazantsev, and A.M. van der Bliek. 1998. A human dynamin-related protein controls the distribution of mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 143:351–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, M.C., W.-X. Zong, E.H.-Y. Cheng, T. Lindsten, V. Panotsakopoulou, A.J. Ross, K.A. Roth, G.R. MacGregor, C.B. Thompson, and S.J. Korsmeyer. 2001. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 292:727–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y., K.R. Pitts, S. Dahan, and M.A. McNiven. 1998. A novel Dynamin-like protein associates with cytoplasmic vesicles and tubules of the endoplasmic reticulum in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 140:779–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerberg, J., S.S. Vogel, and L.V. Chernomordik. 1993. Mechanisms of membrane fusion. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 22:433–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]