Abstract

Expansion and fate choice of pluripotent stem cells along the neuroectodermal lineage is regulated by a number of signals, including EGF, retinoic acid, and NGF, which also control the proliferation and differentiation of central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) neural progenitor cells. We report here the identification of a novel gene, REN, upregulated by neurogenic signals (retinoic acid, EGF, and NGF) in pluripotent embryonal stem (ES) cells and neural progenitor cell lines in association with neurotypic differentiation. Consistent with a role in neural promotion, REN overexpression induced neuronal differentiation as well as growth arrest and p27Kip1 expression in CNS and PNS neural progenitor cell lines, and its inhibition impaired retinoic acid induction of neurogenin-1 and NeuroD expression. REN expression is developmentally regulated, initially detected in the neural fold epithelium of the mouse embryo during gastrulation, and subsequently throughout the ventral neural tube, the outer layer of the ventricular encephalic neuroepithelium and in neural crest derivatives including dorsal root ganglia. We propose that REN represents a novel component of the neurogenic signaling cascade induced by retinoic acid, EGF, and NGF, and is both a marker and a regulator of neuronal differentiation.

Keywords: EGF; NGF; retinoic acid; neurogenic bHLH; neural cell

Introduction

A critical role for EGF receptor (EGF-R)* signaling has been described in the differentiation of pluripotent stem cells. Indeed, EGF-R is expressed in early-stage embryo (Wiley et al., 1992), and EGF regulates the expansion and/or differentiation in vitro and in vivo of specific cell lineages generated from pluripotent embryonal stem (ES) cells (Threadgill et al., 1995; Wu and Adamson, 1996; Schuldiner et al., 2000). More specifically, EGF regulates neural cell fate choice and expansion of pluripotent murine P19 embryonal cells, and of both human and murine ES cells in vitro and in vivo (Wu and Adamson, 1993; Guan et al., 2001; Reubinoff et al., 2001).

The neurogenic activity of EGF also affects central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) neural stem cells. EGF, in combination with FGF, is required to promote differentiation within the neural lineage and may allow the emergence of primitive neural stem cells (for review see Vaccarino et al., 2001). In vivo administration of EGF and the EGF-R ligand TGFα induce the expansion and differentiation of CNS neural progenitor cells (Craig et al., 1996; Fallon et al., 2000). Likewise, EGF sustains the self-renewal of cultured adult and embryonic neural stem cells before further lineage selection, dependent on additional regulatory factors (Lillien and Raphael, 2000; Represa et al., 2001; Gritti et al., 2002). In addition to behaving as a mitogen for immature neuroblasts, EGF also acts as a survival or differentiation-inducing factor for neurons (Morrison et al., 1987; Cattaneo and Pelicci, 1998). EGF-R signaling influences neural crest cell behavior by mediating TGFα-promoted neurite outgrowth and the survival of dorsal root ganglia (Chalazonitis et al., 1992). EGF also promotes proliferation and neural rather than myogenic lineage determination of neural crest–derived TC-1S cells (Screpanti et al., 1995; Vacca et al., 1999; Giannini et al., 2001), stimulates the proliferation of PC12 pheochromocytoma and neuroblastoma cells, and promotes their terminal differentiation (Nakafuku and Kaziro, 1993; Janet et al., 1995; Mark et al., 1995).

How a single growth factor receptor pathway may elicit such wide ranging effects is still an open question. A number of reports suggest that this might occur via cooperation with differentiation specifying coregulatory signals. Several transduction pathways have been reported to functionally interact with EGF-generated signals. Indeed, the requirement of an activated EGF-R signaling for retinoic acid (RA)-induced neuronal differentiation of P19 cells, has been shown (Wu and Adamson, 1993). Finally, EGF and NGF also share common downstream signals that lead to PC12 cell differentiation (Marshall, 1995; Cattaneo and Pelicci, 1998; Klesse et al., 1999).

Therefore, EGF-induced promotion of a neural cell fate by progenitor cell populations would appear to be conserved between pluripotent ES cells and progenitors of CNS and PNS origin. However, the EGF-responsive genes that mediate these responses and their relationships with coregulatory signals, remain to be identified. To this end we have investigated genes differentially regulated during EGF-induced neurogenic fate selection and report the identification of a novel EGF-responsive gene, REN, upregulated by several neurogenic signals (RA and NGF), that exhibits developmentally regulated neural tissue specific expression in the embryo and promotes neuronal differentiation of undifferentiated cells while inducing growth arrest. Our data suggest that REN is a novel target involved in RA, EGF, and NGF downstream neurogenic signals and may terminate growth-enhancing EGF-derived signals, permitting progenitor cells to undergo growth arrest and neuronal cell differentiation.

Results

REN is upregulated by multiple neurogenic signals

In order to identify differentiation associated genes in addition to those related to enhanced proliferation, we analyzed the pattern of gene expression induced during EGF-triggered neurotypic differentiation of neural crest–derived TC-1S cells, by mRNA fingerprinting differential display (Giannini et al., 2001). EGF-regulated genes were compared with previously described genes or EST sequences upregulated during RA-induced ES neuronal differentiation. Among the panel of EGF-regulated genes, we describe in this report REN cDNA (see below), which corresponds to the EST sequence AW244266, which is significantly upregulated during RA-induced neuronal differentiation of ES cells (Bain et al., 2000). To correlate gene expression profiles obtained by mRNA fingerprinting with the neural differentiation process, we also screened a number of cell lines whose neural differentiation was enhanced by multiple neurogenic signals. In particular, we investigated P19 embryonic cells and embryonal striatal ST14A or pheocromocytoma PC12 and neuroblastoma N2a cells as representative of either CNS or PNS/neural crest–derived neural progenitors, respectively (Mark et al., 1995; Prinetti et al., 1997; Cattaneo and Conti, 1998).

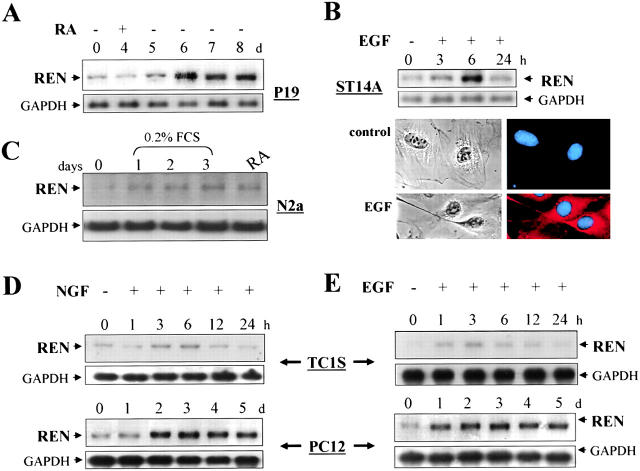

RA-induced neuronal differentiation of P19 cells (Boudjelal et al., 1997) was associated with enhanced levels of 3.0 Kb REN mRNA (Fig. 1 A). Likewise, the neurogenic activity of EGF was also associated with enhanced REN expression. EGF increased REN mRNA levels in ST14A cells in association with the expression of the neuronal marker MAP2 and extension of neurite-like cell processes (Fig. 1 B). Furthermore, REN expression was also upregulated in both TC-1S and PC-12 cells (Fig. 1 E), during EGF-induced neuronal differentiation (Nakafuku and Kaziro, 1993; Screpanti et al., 1995).

Figure 1.

REN is upregulated by multiple neural differentiation signals. Northern blot analysis of REN mRNA in P19 (A), ST14A (B), N2a (C), and TC1S and PC12 (D and E) cells. Hybridization with REN (top) and the ubiquitous GADPH (bottom) are indicated. P19 cells aggregates were treated with 1 μM RA for 4 d and, after plating, cultured in the absence of RA for further 4 d. ST14A cells were treated for 1–24 h with EGF (10 ng/ml) (B, top). (B, bottom) Phase contrast microscopy (left) and immunofluorescence coimmunostaining of cells with either anti-MAP2 antibody (red) or Hoechst (blue, right), 3 d after culturing in the absence (control) or in the presence of EGF treatment (EGF). N2a cells were cultured either in 0.2% FCS for 1–3 d or in the presence of 2% FCS plus 20 μM RA for 2 d (RA). TC-1S and PC12 cells were treated for 1–24 h or 1–5 d, respectively, with EGF (10 ng/ml, E) or with NGF (50 ng/ml, D).

NGF shares with EGF the capacity to promote neuronal differentiation of TC-1S and PC-12 cells (Screpanti et al., 1992; Klesse et al., 1999) and increased REN mRNA levels in both cell lines (Fig. 1 D). RA and serum starvation also upregulated REN mRNA levels in N2a cells (Fig. 1 C) in association with neuronal differentiation (Prinetti et al., 1997; Franklin et al., 1999).

Therefore, upregulation of REN gene expression would appear to be a conserved feature of neuronal differentiation of pluripotent ES cells, CNS and PNS progenitors, thus representing a marker of neuronal differentiation triggered by a variety of neurogenic signals.

Cloning of full-length REN cDNA

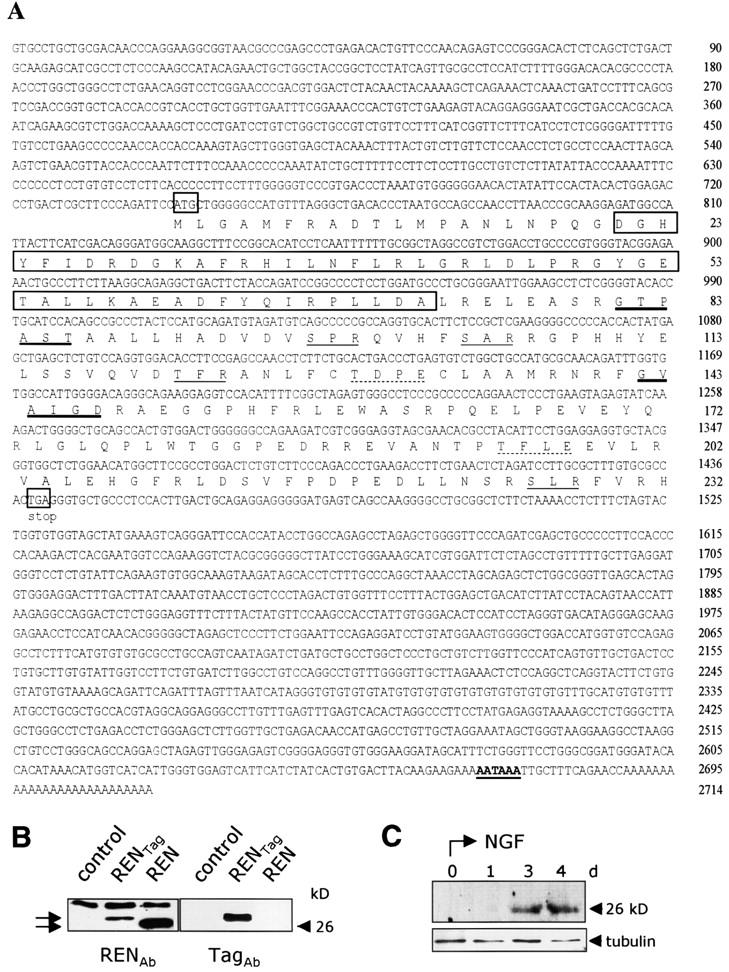

The partial (260 bp) cDNA clone that we refer to as REN (for induced by retinoic acid, EGF, and NGF) identified as described above, was used to screen a mouse embryo (E7) cDNA library, and resulted in the isolation of a cDNA, comprised of 2,688 bp before a poly(A) tail (Fig. 2 A). Sequence analysis revealed an ORF of 232 amino acids (Fig. 2 A) with a typical AATAAA polyadenylation consensus signal present 14 bp 5′ to the poly(A) tail and 1,227 bp downstream of a stop codon (Fig. 2 A). BLAST search revealed no homology with any previously described murine or human gene of known function. However, REN shares 85% nucleotide and 88% amino acid identity with a putative human cDNA ORF, detected in both GenBank and EST databases (EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ accession no. AK056227), that is upregulated during neuronal differentiation of NTera2 pluripotent teratocarcinoma cells.

Figure 2.

Sequence and expressoin of REN cDNA and protein. (A) Nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequence of mouse REN cDNA. The first and last codons of the ORF are boxed and the putative polyadenylation signal is in bold-face type and underlined. Putative casein kinase 2 (dotted underline), protein kinase C (underline), and N-myristoylation (thick underline) sites and BTB/POZ motif (boxed) are shown. These sequence data are available from at EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ accession no. AF465352. (B) Western blot analysis of REN protein in cell lysates from COS7 mock-transfected cells (control), transiently transfected with pCXN2-REN-myc encoding myc epitope-tagged REN protein (RENTag) or with pCXN2-REN encoding wild- type REN (REN) (arrows). Immunoblotting was performed with either anti-REN (RENAb) polyclonal or anti-myc (TagAb) monoclonal antibodies. (C) Western blot analysis of REN protein in cell lysates from PC12 cells treated for the indicated times with NGF, revealed by anti-REN antibody. α-Tubulin staining is also shown, as a loading control.

A protein similarity search revealed that REN amino acids 21 to 72 encode a BTB/POZ motif (Bardwell and Treisman, 1994) (Fig. 2 A), with no other similarities to known proteins detected. Sites for possible posttranslational modification include putative N-myristoylation and phosphorylation sites for PKC and casein kinase 2 (Fig. 2 A). The REN amino acid sequence is consistent with a soluble protein. The REN mRNA product exhibits an approximate molecular mass of 26 kD, similar to the calculated mass of the protein and to that of the protein upregulated by NGF in PC12 cells or extracted from cells transfected with either REN or myc epitope–tagged REN expression vectors, detected using either anti-REN polyclonal or anti-myc monoclonal antibodies (Fig. 2 B).

Developmentally regulated expression of REN in the mouse nervous system

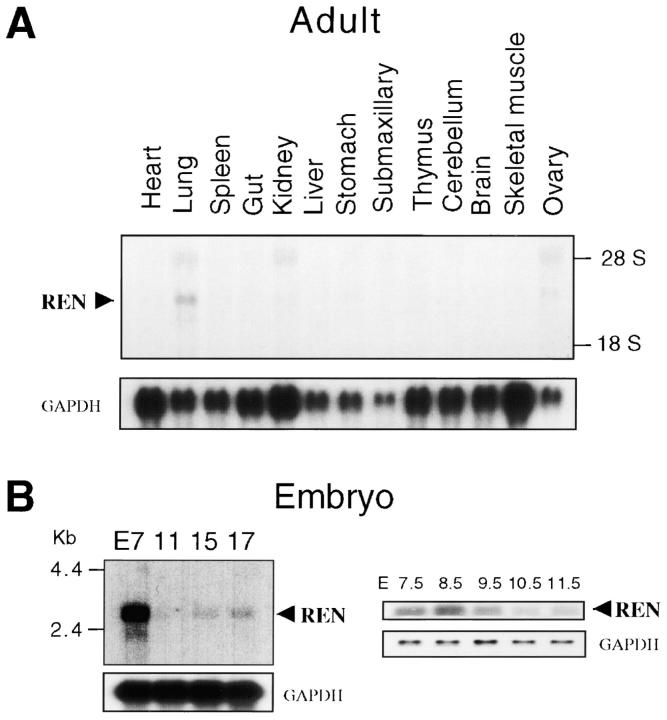

Northern blot analysis of adult mouse tissues did not reveal significant levels of REN mRNA, with the exception of low levels in lung tissue (Fig. 3 A). REN mRNA expression was detected in E7 embryo, with lower levels observed at subsequent stages (E11–E17) (Fig. 3 B, left). A more detailed analysis of REN transcripts, performed by semiquantitative RT-PCR, revealed a peak of gene expression at E8.5, with decreasing levels thereafter (Fig. 3 B, right).

Figure 3.

REN mRNA levels in adult murine tissues and during embryo development. Northern blot analysis of RNA isolated from adult mouse tissues (A) or from E7 to E17 whole embryos (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.; B, left), hybridized with REN cDNA. RT-PCR analysis (B, right) of REN RNA isolated from embryos at E7.5–E11.5. RT-PCR analysis of coamplified GAPDH is also shown.

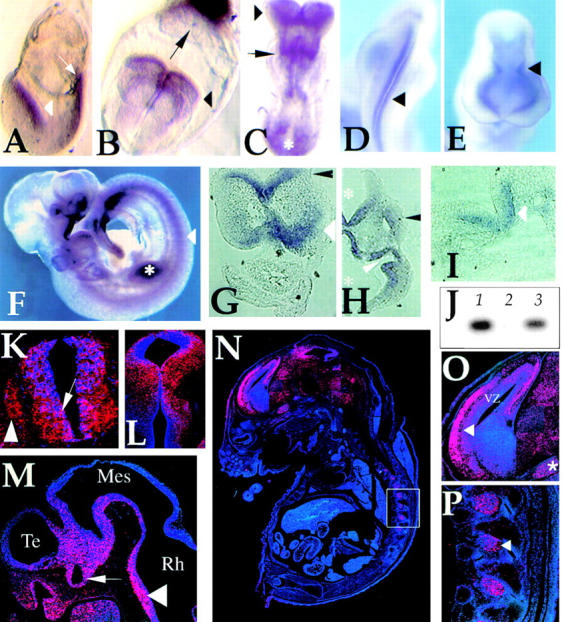

The developmental pattern of REN expression was also investigated by in situ hybridization using embryos of ages E7.5–E16.5. At E7.5, REN transcript was detected in the ectodermal neural folds, the primitive streak and the ectoplacental cone (Fig. 4, A and B) . Subsequently (E8.25–E10.5), a REN hybridization signal was detected along the entire neural tube, in the first rhombomere and in the optic and otic vesicles, although REN was also expressed in the maxillary and mandibular component of first branchial arch, in the somites and in the limb buds (Fig. 4, C–F).

Figure 4.

REN expression in mouse embryo tissues during development. Whole-mount in situ hybridization at E7.5 (A), E8 (B), E8.25 (C), E9 (D and E) and E9.5 (F) reveals expression in the developing neural folds (A, white arrowhead in; B and C, black arrowhead), along the neural tube (D and E, black arrowhead), in the primitive streak (A, arrow; C, asterisk), in the ectoplacental cone (B, arrow), in newly forming somites and in the first rhombomere (C, arrow). At later stage (F), expression is restricted to the ventro-medial region of the neural tube (arrowhead), somites, optic and otic vesicles, the regions of the first branchial arch, the olfactory placode and developing limb buds (asterisk). Bright-field views of sections from whole mount (G–I) and postembedded in situ radioactive hybridizations (K–P) are also shown. Transverse sections confirmed expression in the cephalic neural folds (prospective forebrain; G, black arrowhead; E8.25), in the neuroepithelium of prospective hind brain (G, white arrowhead) and more caudally in the ventro-medial region of the neural tube (I, arrowhead; stage E8.25; K, arrow; stage E10.5). Coronal (H, stage E9.5) and sagittal (M, stage E10.5) sections show REN expression in the neuroepithelium of the fourth ventricle and of the diencephalon (H, asterisks) of the rhomboencephalic (Rh), mesencephalic (Mes), and telencephalic (Te) vesicles (M, arrowhead), in the olfactory placode including the epithelium lining the olfactory pit (M) and in the optic vesicle and stalk (H, white arrowhead; M, arrow). At later stages, REN expression characterizes more defined territories within the outer neuropeithelium layers of the midbrain and of the ventricular zone (VZ) of the cortical plate (L at stage E12.5; N; O, arrowhead; at stage E16.5). Some low and diffuse REN staining is also observed in the whole brain area (N). In the E16.5 embryo, outside of the brain REN expression was detected in dorsal root ganglia (N; P, arrowhead), preceded by expression in neural crest-derived spinal primordia (K, arrowhead). REN is also expressed in the trigeminal ganglion (O, asterisk) and in mesenchime of the maxillary component of the first branchial arch containing trigeminal neural crest tissue (H, black arrowhead). (J) RT-PCR analysis of REN expression in primary cultures of neural cells explanted from E9.5 embryonal neural tubes, cultured for 24 h (lane 1) and in differentiated N2a cells (lane 3), whereas no expression is detected in thymocytes isolated from newborn mice (lane 2).

Sections of E8.25–E10.5 embryos revealed REN expression in the neuroepithelium of the cephalic neural folds and of the neural tube, where REN was strongly expressed in the middle and ventral region in layers external to the lumen (Fig. 4, G–K and M). REN expression within the neural tube was confirmed by RT-PCR analysis of mRNA isolated from primary neural tube cell cultures derived from E9.5 neural tube explants (Fig. 4 J).

REN expression was also observed in the neural crest–derived spinal primordia, that give rise to the sensory cells of dorsal root ganglia (Fig. 4 K), in the optic stalk and vescicle (Fig. 4, H and M) and in the nasal process (Fig. 4 M). At stage E16.5, REN displayed a more restricted pattern of tissue expression (Fig. 4 N), confirmed by a decreased level of mRNA detected by RT-PCR and Northern blot analysis (Fig. 3 B). This would suggest that REN is regulated during progressive neural development.

The ability of REN to be upregulated by signals inducing neuronal differentiation (Fig. 1) suggests that its expression pattern might be restricted as neuronal progenitors undergo differentiation. Therefore, in order to investigate REN expression in actively proliferating versus differentiating neural regions, embryo sections at E12.5–E16.5 stages were examined. At these stages neural cell proliferation occurs in the ventricular zone lining the ventricular lumen of the cortex (Conti et al., 1997). Conversely, differentiation follows a gradient of neurogenesis in which postmitotic cells migrate away from the lumen towards the cortical plate and subsequently mature (Bayer and Altman, 1991; Zhong et al., 1997). REN expression was barely detectable in the ventricular zone lining the lumen, whereas a strong signal was detected in outer layers of the cortical plate (Fig. 4 O) containing newly differentiated neural cells (Bayer and Altman, 1991; Conti et al., 1997; Zhong et al., 1997). A similar pattern was detected in the mesencephalic and diencephalic regions at the earlier E12.5 developmental stage (Fig. 4 L). Lower hybridization signals were observed in areas outside of the ventricular layers of E16.5 brain (Fig 4 N). No hybridization was detected in E16.5 embryo outside of the brain, with the exception of dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglion of neural crest origin (Fig. 4, P and O).

These results suggest that REN expression is developmentally regulated, being expressed initially by neuroectodermal cells, later in neural crest derivatives, in the ventral region of the spinal cord and in the ventricular epithelium of the cephalic neural tube restricted to differentiating (outer) rather than proliferating (inner) cells of the cortical ventricular zone.

Enforced expression of REN slows the proliferative rate and induces p27Kip1 upregulation

During neurogenesis, neuronal differentiation is preceded by withdrawal from the cell cycle (Farah et al., 2000). The specific pattern of REN expression in regions containing differentiating neural progenitors at late embryonal CNS stages (Fig. 4 O), led us to investigate whether REN expression could regulate proliferation while permitting neuronal differentation.

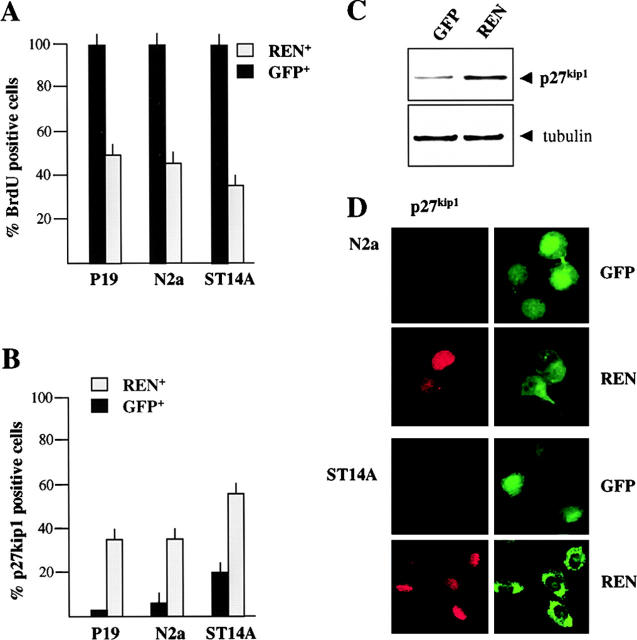

For this purpose, P19 cells were transfected with either empty expression vector (pCXN2) or REN cDNA cloned into pCXN2. Stable REN+ transfectants were selected by resistance to geneticin. No clones expressing REN protein were isolated after long term culture, suggesting that enforced REN expression interferes with growth and/or survival. REN control of cell growth was confirmed by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) uptake after enforced transient myc epitope–tagged REN expression in P19 cells, which induced a significant decrease in BrdU incorporation, when compared with GFP-transfected controls (Fig. 5 A). Similar growth inhibitory activity of REN was observed in ST14A and N2a cells, with a significant decrease of BrdU incorporation observed after REN transfection compared with GFP-transfected controls (Fig. 5 A).

Figure 5.

REN induces cell growth arrest. (A) Cell growth arrest in P19, N2a, and ST14A cells transfected with expression vector pCXN2-REN-myc or with GFP expression vector. BrdU was added 24 h after transfection and detected after 2–24 h of incorporation. The percentage of BrdU incorporating cells in the REN+ or in the GFP+ population, was determined by coimmunostaining with anti-myc epitope and anti-BrdU antibodies or with anti-GFP and anti-BrdU antibodies and immunofluorescence microscopy. Average (± SEM) percentages of BrdU positive cells from three independent experiments performed in triplicate are shown. (B) Expression of p27Kip1 in control (GFP-transfected cells, GFP) and REN cDNA-transfected cells (REN) 48 h after transfection into P19, N2a, and ST14A cells. The percentage of p27Kip1 positive cells in the REN+ and in the GFP+ population, was determined by coimmunostaining with anti-myc epitope or anti-GFP antibodies and by immunofluorescence microscopy. Average (± SEM) percentages of p27Kip1 positive cells from three independent experiments performed in triplicate are shown. (C) Western blot analysis of p27Kip1 and α-tubulin expression in control (GFP-transfected, GFP) and REN cDNA-transfected N2a cells (REN), 48 h after transfection. (D) Exogenous expression of REN enhances p27Kip1 expression in N2a and ST14A cells. Confocal microscopy of coimmunostaining of p27Kip1 (red) and either myc epitope (green, REN) or GFP (green, GFP), in either GFP- (GFP) or REN-transfected (REN) cells, 48 h after transfection.

To further characterize the growth arrest response to REN, the expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 was examined in REN-transfected N2a cells in which a significant increase of p27Kip1 levels was detected by Western blot (Fig. 5 C). This was confirmed by immunofluorescence studies in which GFP-transfected controls expressed barely detectable levels of p27Kip1 (5% of GFP+ cells coexpressed p27Kip1), whereas 36% of REN-transfected cells coexpressed significantly higher levels of p27Kip1 (Fig. 5, B and D). Likewise, a significantly higher number of REN transfected ST14A and P19 cells coexpressed p27Kip1 when compared with GFP-transfected controls (Fig. 5, B and D). These results suggest that REN regulates cell proliferation in several neuronal cell precursors leading to the triggering of cell growth inhibitory signals.

Abrogation of REN expression prevents RA-induced enhancement of neurogenin1 and NeuroD expression in P19 cells

The specific neuroectodermal pattern of REN expression in the embryo, its association with neuronal differentiation in vivo and in vitro and its capacity to regulate cell proliferation, led us to investigate the potential role of REN in the regulation of molecular events implicated in neural development. Several genes are activated during RA-induced neuronal differentiation of P19 cells, including neurogenic bHLH transcription factors such as Mash1, neurogenin (ngn)1, and NeuroD, which promote mammalian neuronal determination and differentiation (Johnson et al., 1992; Boudjelal et al., 1997; Massari and Murre, 2000). The enforced expression of NeuroD, ngn1, or Mash1 initiates cell cycle withdrawal by increasing p27Kip1 levels and converts undifferentiated P19 embryonal cells into neurons (Farah et al., 2000).

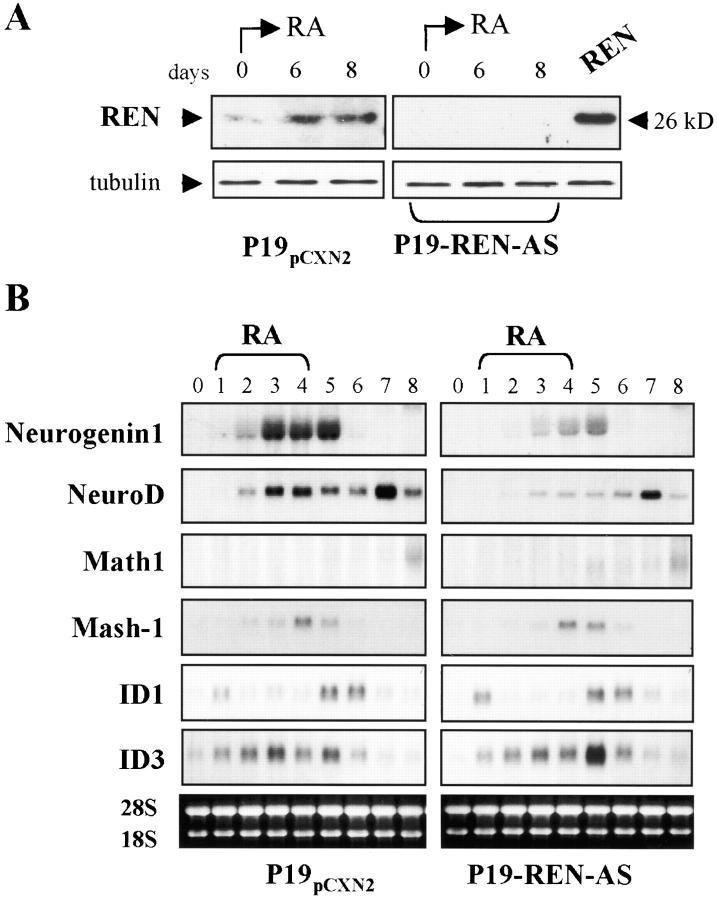

In order to investigate the involvement of REN in the regulation of neurogenic bHLH expression in differentiating P19 cells, the effect of inhibiting REN expression was studied using antisense RNA technology. P19 cells were transfected either with empty expression vector pCXN2 (P19-pCXN2 control cells) or with REN cDNA cloned into pCXN2 in antisense orientation (P19-REN-AS), and several individual stably transfected clones and polyclonal populations were selected by neomycin resistance.

Low levels of REN protein were detected in undifferentiated P19-pCXN2 control cells (Fig. 6 A). RA treatment, while inducing neural differentiation, increased REN protein expression above basal levels (Fig. 6 A, left). In contrast, several individual P19-REN-AS clones and a polyclonal cell population exhibited no endogenous REN protein expression, when compared with pCXN2 transfectants, either in the absence or in the presence of RA treatment (Fig. 6 A, right; Table I), suggesting that both basal and RA-enhanced REN protein production had been abrogated by the expression of antisense-REN. Likewise, REN–myc fusion protein expression was significantly lower after transfection of pCXN2-REN-myc into P19-REN-AS stably transfected cells when compared with the P19-pCXN2 controls (Table I). This confirmed that lack of REN expression in P19-REN-AS cells was not just an intrinsic property of this selected cell population but a result of antisense REN mRNA production.

Figure 6.

Abrogation of REN expression reduces the levels of Neurogenin1 and NeuroD. (A) Western-blot of endogenous REN and protein encoded by transfected pCXN2-REN (REN) in P19 cells treated with RA, as described in B, and revealed using anti-REN antibody. (B) Northern blot analysis of RNA isolated from P19 cells stably transfected with either REN cDNA cloned in antisense orientation into pCXN2 (P19-REN-AS) or empty vector P19-pCXN2 and treated with RA as described in Fig. 1 A. Blots were hybridized with cDNA probes for neurogenin-1, NeuroD, Math1, Mash1, Id1, and Id3, as indicated on each panel. Ethydium bromide staining of ribosomal RNA is shown as a loading control.

Table I. Differential RA-induced regulation of HLH gene expression in response to inhibition of REN expression.

| P19-pCXN2 | P19-REN-AS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pool | #E3 | #E5 | #E10 | Pool | #D11 | #D12 | #D13 | |

| ngn1 | 1.0 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 1.1 | 0.20 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.15 |

| NeuroD | 1.0 | 0.98 | 1.15 | 0.90 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.20 | 0.30 |

| Mash1 | 1.0 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 1.1 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 1.10 | 0.80 |

| Math1 | 1.0 | 1.10 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 1.0 | 0.90 | 1.10 | 1.15 |

| Id1 | 1.0 | 0.90 | 1.15 | 0.95 | 1.0 | 1.15 | 0.85 | 0.95 |

| Id3 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.15 | 0.80 | 1.25 | 1.0 | 0.80 | 0.90 |

| %REN+ | 15% | 12% | 16% | 13% | 5% | 6% | 4% | 5% |

Relative average mRNA levels (from two experiments) of HLH gene products in P19-REN-AS cells (polyclonal pool population and individual #D11, #D12, and #D13 clones), with respect to the value observed in P19-pCXN2 (polyclonal pool population, assigned the value 1) and individual #E3, #E5, and #E10 clonal control cells. Levels of mRNA for each gene product were evaluated at the time of maximum induction in response to RA treatment (as indicated in Fig. 6). The percentages of REN-positive cells among GFP-transfected cells (%REN+) are from a representative experiment, by evaluating myc-tag immunofluorescence in either P19-pCXN2 and P19-REN-AS cells 24 h after cotransfection with pCXN2-RENmyc and GFP expression vectors.

RA enhanced the expression of ngn1, NeuroD, Mash1, Math1, and their inhibitors Id1 and Id3 in polyclonal P19-pCXN2 cells (Fig. 6 B), confirming previous reports (Johnson et al., 1992; Boudjelal et al., 1997). In contrast, RA-treated polyclonal P19-REN-AS populations exhibited a reduced induction of ngn1 and NeuroD expression, whereas RA-induction of Mash1, Math1, Id1, and Id3 expression was not significantly affected (Fig. 6 B). These data suggest that impaired upregulation of ngn1 and NeuroD after the abrogation of REN expression represents a specific response of P19-REN-AS cells to RA, as RA enhanced the expression of other bHLH genes (e.g., Mash1). Similar results were obtained with several individual P19-pCXN2 and P19-REN-AS clones (Table I). Therefore, appropriate levels of REN are specifically required for RA enhancement of ngn1 and NeuroD expression, suggesting a role in the regulation of specific bHLH neurogenic genes.

REN enhances the expression of neuronal markers in neural progenitor cells

The hypothesis that REN may promote neuronal differentiation was directly addressed by transfecting either myc epitope–tagged REN or the empty GFP-encoding vector into cell lines representative of distinct differentiation stages or types of progenitor cells that undergo neuronal differentiation in response to different growth inhibitory signals (Prinetti et al., 1997; Cattaneo and Conti, 1998; Farah et al., 2000). Undifferentiated pluripotent P19 ES cells failed to undergo neuronal differentiation (as evaluated by monitoring the expression of MAP2 or TuJ1 neuronal markers) upon transduction of REN-myc, whereas enforced Mash1 expression enabled cells to differentiate into mature neurons (unpublished data), confirming a previous report (Farah et al., 2000). Therefore, REN is not sufficient for promoting a complete neurogenic program from an early differentiation phase.

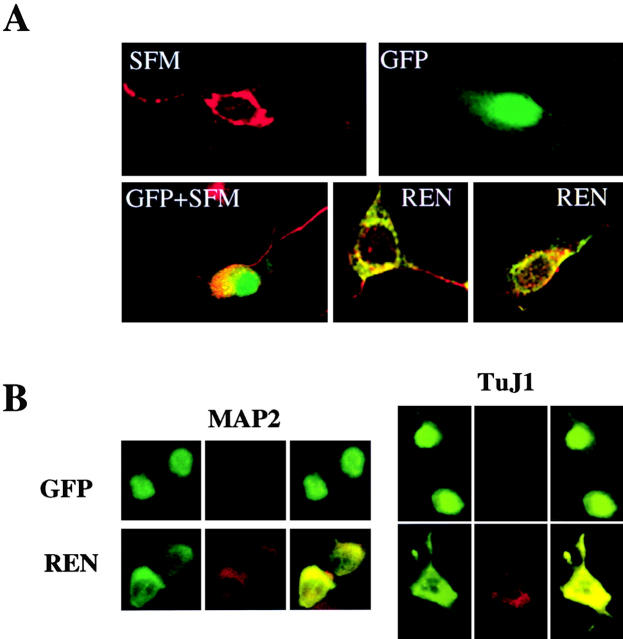

In contrast, REN promoted neuronal differentiation of neural committed progenitor cells of CNS (ST14A cells, Fig. 7 A) or PNS (N2a cells, Fig. 7 B) origin. ST14A neural stem cells undergo postmitotic neuronal differentiation when cultured in SFM conditioned medium, but not in conventional growth medium (Cattaneo and Conti, 1998). Accordingly, we observed that untransfected or GFP-transfected ST14A cells exhibited morphological modifications characterized by neurite extension and enhanced expression of neuron-specific differentiation markers, including MAP2, when cultured in SFM (Fig. 7 A), but not in conventional growth medium (<1% of GFP+MAP2+ cells) (Fig. 7 A). In contrast, ∼90% of transfected REN+ cells cultured in growth medium exhibited MAP2 expression, with REN and MAP2 colocalized to the cell body with additional MAP2 localization to neurite-like cell processes (Fig. 7 A).

Figure 7.

Exogenous expression of REN enhances neuronal marker expression in ST14A and N2a neural progenitor cells. Confocal microscopy of combined coimmunostaining of MAP2 or TuJ1 (red) and either myc epitope (green) or GFP (green; overlapping signals are yellow). (A) Untransfected (SFM) or GFP-transfected (GFP + SFM) ST14A cells grown in SFM for 7 d display a differentiated morphology and positive staining for MAP2. Cells transfected with GFP encoding expression vector and cultured in growth medium for 7 d, display GFP immunofluorescence and no staining for MAP2 (GFP panel). Cells transfected with myc epitope-tagged REN protein encoding vector and cultured in growth medium for 7 d, display coexpression of both myc epitope and MAP2 immunofluorescence (REN panels). (B) N2a cells transfected with REN expression vector (REN) display coexpression of REN and either MAP2 or TuJ1, 3 d after transfection. In contrast, cells transfected with GFP encoding expression vector and cultured for 3 d, display GFP immunofluorescence and no staining for either MAP2 or TuJ1. The pictures shown are from a representative experiment (out of three) with MAP2 or TuJ1 expression scored from 150 to 300 transfected cells examined.

Similarly, GFP-transfected N2a cells revealed low-level MAP2 and TuJ1 coexpression with GFP (8 –13 ± 2% of GFP+MAP2+ or GFP+TuJ1+ cells), whereas 40 ± 3% and 45 ± 5% of REN+ cells exhibited high-level MAP2 or TuJ1 expression, respectively, and displayed neurite outgrowth (Fig. 7 B). These results suggest that enforced REN expression promotes the neuron-specific protein expression in neural progenitor cells, consistent with a role for REN in neuronal differentiation.

Discussion

We describe the identification and functional characterization of a novel EGF-, NGF- and RA-responsive gene, REN, that exhibits no significant homology with previously described murine or human genes nor carries putative functional domains observed in other classes of proteins, with the exception of a BTB/POZ motif located at the NH2-terminal between amino acid residues 21 and 72. Such a motif is involved in protein–protein interactions and is typical of several CH2H2-type transcription factors and Shaw-type potassium channels (Bardwell and Treisman, 1994) suggesting that REN may dimerize with other proteins, yet to be identified.

The involvement of REN in early phases of neural cell development is suggested by its peculiar pattern of expression during embryogenesis. In fact, REN transcripts appear in neuroectodermal cells of neural folds and later extend to neuroepithelial cells throughout the neural tube and encephalic vesicles, therefore suggesting a relationship with the early developmental neurogenetic process. Likewise, REN is specifically expressed in neural crest primordia and subsequently in their derivatives (e.g., dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglion). These observations are consistent with a role for REN in the regulation of neural cell differentiation from CNS- and neural crest/PNS-derived progenitor cells observed in vitro. Accordingly, we also report that REN directly promotes neuronal differentiation, being sufficient to trigger phenotypic features such as neurite elongation and the expression of the neuron specific markers (MAP2 and TuJ1), that characterize terminal differentiation of ST14A and N2a neural progenitor cells. However, the ability of REN to control additional cell differentiation programs (e.g., glial) cannot be ruled out, as suggested by the presence of REN expression in optic stalk, known to give rise mainly to glial cells.

REN appears to be upregulated by EGF, known to enhance proliferation of neural stem cells. How growth signal-enhanced REN is related to events determining neuronal differentiation needs to be fully elucidated. However, we report evidence indicating that this may occur via inhibition of cell growth. Indeed, REN appears to be developmentally regulated in embryonal neuroepithelial cells and its expression correlates with the spatially defined gradient of neurogenesis observed in the cortex, in which proliferating neuroblasts are localized in the ventricular zone lining the lumen and, as they subsequently exit from the cell cycle and differentiate, migrate away from the lumen towards the cortical plate (Bayer and Altman, 1991; Conti et al., 1997; Zhong et al., 1997). Interestingly, REN expression was barely observed in the layer of the ventricular zone lining the lumen, but was instead confined to outer layers containing low proliferating and newly differentiated neural cells. These in vivo observations are consistent with the in vitro findings that REN expression relates to growth arrest conditions in association with neuronal differentiation. Indeed, NGF, RA, and serum withdrawal, which inhibit neural cell proliferation (Screpanti et al., 1992; Prinetti et al., 1997; Franklin et al., 1999; Bang et al., 2001), increased REN expression in a number of cell lines (e.g., N2a, PC12, and P19 cells) and enhanced neuronal differentiation. The ability of REN to control cell growth has been confirmed by REN-dependent inhibition of proliferation in association with enhanced expression of cyclin D/cdk4 cell cycle inhibitor p27Kip1 in P19 cells and in a number of CNS- and PNS-derived cell lines. The requirement of REN for the RA-induced upregulation of ngn1 and NeuroD expression, involved in neuronal differentiation of P19 embryonal cells, is consistent with a previous report that growth arrest and p27Kip1 protein expression are enhanced by these bHLH proteins (Farah et al., 2000).

These data are in agreement with previous reports which describe that, after an initial burst of cell division during the development of the mammalian embryonic nervous system, the subsequent inhibition of cell proliferation is a prerequisite for neuronal differentiation (Mark and Storm, 1997). Indeed, the combination of EGF with antiproliferative signals (e.g., cAMP) has been described to modify the mitogenic properties of EGF and to convert it to a differentiation factor (Mark and Storm, 1997). A number of reports suggest that these negative regulatory signals might behave as a feedback loop which modulates the output of signals generated by EGF itself. Indeed, developmental studies have provided evidence that such a feed back regulation is required to ensure proper cell fate determination. For instance, Argos, an inhibitor of Drosophila EGF-R (DER) function, is transcriptionally triggered by DER itself, and specifies the patterning of the ventral ectoderm in response to DER activity (Golembo et al., 1996).

However, REN-induced growth inhibitory activity is not sufficient to promote neuronal differentiation of all neural progenitor cells, as suggested by its capacity to differentiate neural committed ST14A and N2a cells, but not P19 pluripotent embryonal cells. Whether this is due to the ability of REN to only partially recruit neuronal differentiation signals in P19 cells, remains to be elucidated. However, the capacity of REN to regulate ngn1 and NeuroD, but not Mash1 expression (Fig. 6), is consistent with this hypothesis. Accordingly, Mash1 has been reported to be a much stronger inducer of P19 cell neuronal differentiation, when compared with ngn1 and NeuroD (Farah et al., 2000). Therefore, whereas growth inhibitory activity appears to be a general property of REN, its ability to promote neuronal differentiation is restricted to neural committed CNS and PNS progenitors. REN requirement for RA-enhanced expression of ngn1 and NeuroD but not of other HLH genes (e.g., Mash1, Math1, Id1, and 3), suggests its involvement in specific regulatory pathways. This is further supported by the overlapping patterns of expression of REN with ngn1 and NeuroD, which were all detected in the ventral neural tube, in the ventricular and adjacent intermediate zones of the cortex, and in sensory ganglia (dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglion) in E8.5–E16 embryos (Sommer et al., 1996; Ma et al., 1998). bHLH proteins have been implicated in the control of the individual steps and the different cell lineages that characterize the vertebrate CNS neurogenic process (Hassan and Bellen, 2000). In the vertebrate PNS, neuronal lineage development is initiated by the determination of multipotent precursors via the action of neurogenins, with their function being subsequently maintained by their target gene NeuroD. Further lineage determination is specified by the action of independently regulated bHLH genes, such as Mash1 and Math1 (Hassan and Bellen, 2000). The requirement of REN for specific regulation of ngn1 and NeuroD expression but not other bHLH genes (e.g., Mash1 and Math1) suggests an influence upon early ngn1-dependent steps of neurogenesis, via the regulation of specific bHLH proteins which influence specific developmental phases or cell lineages. In conclusion, we have identified a novel developmentally regulated gene and its product, REN, that displays a neuroectodermal specific pattern of embryonal expression, promotes neural progenitor cell growth arrest and neuronal differentiation. Such features correlate with proliferative and differentiative status of embryonic neuroepithelial cells in the murine forebrain.

These observations together with REN responsiveness to distinct neurogenic stimuli (e.g., EGF, RA, and NGF) and its involvement in the regulation of selected downstream signals (e.g., ngn1 and NeuroD), suggest a role in the transition from proliferation to differentiation of neural cells. In particular, enhanced REN expression by mitogenic stimuli such as EGF, may withdraw progenitor cells from the cell cycle permitting their terminal neuronal differentiation.

Materials and methods

mRNA fingerprinting differential display, and REN

Five 800–1,400-bp partially overlapping clones containing REN sequences were obtained by screening an oligo(dT) and random primed Swiss Webster/NIH mouse 7-d Embryo 5′ Stretch Plus cDNA Library (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.) with a 260-bp probe generated by mRNA fingerprinting performed as described (Giannini et al., 2001). Full-length REN cDNA was assembled from cloned sequences using AutoAssembler software (Perkin-Elmer).

Plasmids

pCXN2-REN and pCXN2-REN-AS were obtained by cloning REN cDNA fragment (1–2,015 bp) into the pCXN2 vector, provided by Dr. E.D. Adamson (Burnham Institute, La Jolla, CA) (Wu and Adamson, 1996), in sense (pCXN2-REN) or antisense orientation (pCXN2-REN-AS). pCDNA/REN-myc and pCXN2-REN-myc were constructed by cloning the coding region of REN cDNA (737–1,438 nt) into pCDNA3.1(−)/myc-His A and subsequently into pCXN2. Each clone was verified by automated DNA sequence analysis.

Production of anti-REN polyclonal antibody

Polyclonal antibodies against amino acid residues 116–232 of recombinant GST–REN fusion protein were raised in New Zealand white male rabbit and purified using Sephadex Fast flow beads conjugated with a Protein A (Sigma-Aldrich; Harlow and Lane, 1988).

Cell culture and transfections

TC-1S cells were cultured as described (Screpanti et al., 1992). P19 cells were maintained in αMEM supplemented whith 7.5% heat-inactivated newborn calf serum (GIBCO BRL) and 2.5% FCS. To induce differentiation, 106 cells were allowed to aggregate in the presence of 1 μM all trans-RA (Sigma-Aldrich), and after 4 d embryoid bodies were dissociated and transferred onto poly-l-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich) coated dishes without RA and further treated with 4 μM cytosine arabinoside after 24 h (Farah et al., 2000). Differentiated neurons appeared after a further 24 h. PC12 cells were grown on collagen-coated dishes in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% noninactivated FCS and 10% horse serum (Sigma-Aldrich).

ST14A embryonal CNS neural stem cells, provided by Dr. E. Cattaneo (University of Milan, Milan, Italy), cultured at the permissive 33°C temperature in 10% FCS growth medium, remained undifferentiated, whereas cell division ceased and morphological differentiation occurred upon culture at 33°C in serum-free conditioned medium, as described (Cattaneo and Conti, 1998). N2a cells were maintained in DME supplemented with 10% FCS and induced to differentiate by culturing in either 0.2% FCS (Franklin et al., 1999) or 2% FCS plus 20 μM RA (Prinetti et al., 1997). COS7 cells were grown in DME with 10% FCS. Primary cultures of neural tube cells were explanted from E9.5 mouse embryos in DME containing 10% FCS, as described (Tajbakhsh et al., 1994).

Cells were transfected either with Lipofectamine (Life Technologies, GIBCO BRL) or with Superfect Transfection Reagent (QIAGEN, Inc.). Polyclonal populations and individual clones of P19-pCXN2 and P19-REN-AS cells, transfected with either pCXN2 vector or pCXN2-REN-AS, respectively, were isolated by appropriate drug selection.

RNA analysis

RNA was isolated using either the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Inc.) or Trizol (Life Technologies, GIBCO BRL), electrophoresed on a 6% formaldehyde/1% agarose gel and blotted onto nylon membranes (Hybond-N, Amersham Biosciences) for Northern analysis using 32P labeled probes.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR was carried out on DNase Amp Grade (GIBCO BRL)-treated RNA using MuLV RT (50 units) in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 500 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM each dNTP, 1 unit of Rnasin, 500 pmol of random hexamer primers. PCR cycles were designed to maintain the amplification in the exponential phase. RT-PCR products were electrophoresed and hybridized to REN and GAPDH specific probes. Primer sequences used for PCR were: REN sense primer 5′-GCTCTGACTGCAAGAGCATCGCCTC-3′ and antisense primer 5′-AGACTTGCTAAGTTGGAGGCAGAGG-3′; GAPDH sense primer 5′-CACCATGGAGAAGGCCGGGG-3′ and antisense primer 5′-GACGGACACATTGGGGGTAG-3′; Id1 sense primer 5′-CCAGTGGCAGTGCCGCAGCCGCTGCAGGC-3′ and antisense primer 5′-GGCTGGAGTCCATCTGGTCCCTCAGTGC-3′; Id3 sense primer 5′-AAGGCGCTGAGCCCGGTGC-3′ and antisense primer 5′-TCGGGAGGTGCCAGGACG-3′; and ngn1 sense primer 5′-CCGACGACACCAAGCTCA-3′ and antisense primer 5′-GGGATGAAACAGGGCGTC-3′. Probes for Math1, NeuroD and Mash1 were obtained from CS2+MATH1, CS2p + NeuroD and CS2 + Mash1 plasmids (Farah et al., 2000), provided by Dr. D. Turner (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI).

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy analysis

Immunofluorescence was performed on cells grown on 12-mm slides, fixed for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature, and processed as previously described (Giannini et al., 2001). Primary antibodies were: mouse monoclonal MAP2 and TuJ1 (MAB3418 and MAB 1637; Chemicon International, Inc.) and p27Kip1 (K25020 Transduction Laboratories); rabbit polyclonal anti-Myc Tag (06-549; Upstate Biotechnology) and anti-GFP (sc-8334; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Secondary antibodies were fluorescein- or Texas red–conjugated affinePure anti–rabbit or anti–mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Scanning confocal microscopy was performed using a laser scanning confocal microscope Zeiss LSM, equipped with Argon and HeNe lasers.

Western blot analysis

Cell lysates were prepared in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, containing 8 M urea, 140 mM β-Me, 0.1% SDS, and 20 mM EDTA, separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and elettroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell; Castellani et al., 1996). Immunoblotting was performed with mouse monoclonal antibodies against either c-myc (9E10; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) or p27Kip1 (K25020; Transduction Laboratories) or α-tubulin (Ab1; Oncogene Science) or anti-REN polyclonal antibody; HRP-conjugated secondary Abs, anti–rabbit IgG and anti–mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) were used and immunoreactive bands visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce Chemical Co.).

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was evaluated by BrdU labeling and detection assay (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH), 24 h after transfection with test plasmids. The cells were fixed after BrdU incorporation and permeabilized as described above. After the primary and secondary labeling with anti-GFP or anti-Myc, cells were refixed for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature, treated for 10 min with HCl 2N to denature DNA, and BrdU detection was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA in situ hybridization

Embryos were prepared for whole-mount in situ hybridization as previously described (Tajbakhsh et al., 1998), modified with 16-h washes after antibody incubation. mRNA transcripts were detected using Digoxigenin-labeled 780-bp riboprobes containing 400 bp of the 3′ coding region and 400 bp of 3′ UTR of cDNA subcloned into pBluescript SK (Stratagene) and synthetized using T3 or T7 polymerases. The probe used revealed reproducible hybridization patterns when in antisense orientation and no signal in the sense orientation (unpublished data). Photographs of whole-mount stained embryos were taken with a Leica MZ8 stereomicroscope using color reversal films (Ektachrome 64T). Stained embryos were embedded in 7% gelatin/15% sucrose and 30-μm cryostate sections were cut. In situ hybridization of post-embedded sections using the above described 35S-labeled REN probe was performed as described (Gulisano et al.,1996).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr G. Franzoso for critical reading of the manuscript, Drs. E.D. Adamson, E. Cattaneo, and D. Turner for providing reagents, and C. Pardini and M. Zani for technical assistance.

This work was partially supported by grants from the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro, the National Research Council, “Oncology” Projects, the Ministry of University and Research, the Ministry of Health, MURST-CNR “Biomolecole per la Salute Umana” Program, and Associazione Italiana per la Lotta al Neuroblastoma.

R. Gallo and F. Zazzeroni contributed equally to this work.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: BrdU, bromodeoxyuridine; CNS, central nervous system; DER, Drosophila EGF receptor; EGF-R, EGF receptor; ES, embryonal stem; ngn, neurogenin; PNS, peripheral nervous system; RA, retinoic acid.

References

- Bain, G., F.C. Mansergh, M.A. Wride, J.E. Hance, A. Isogawa, S.L. Rancourt, W.J. Ray, Y. Yoshimura, T. Tsuzuki, D.I. Gottlieb, and D.E. Rancourt. 2000. ES cell neural differentiation reveals a substantial number of novel ESTs. Funct. Integr. Genomics. 1:127–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang, O.S., E.K. Park, S.I. Yang, S.R. Lee, T.F. Franke, and S.S. Kang. 2001. Overexpression of Akt inhibits NGF-induced growth arrest and neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells. J. Cell Sci. 114:81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell, V.J., and R. Treisman. 1994. The POZ domain: a conserved protein-protein interaction motif. Genes Dev. 8:1664–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer, S.A., and J. Altman. 1991. Neocortical Development. Raven, New York. 272 pp.

- Boudjelal, M., R. Taneja, S. Matsubara, P. Bouillet, P. Dollé, and P. Chambon. 1997. Overexpression of Stra13, a novel retinoic acid-inducible gene of the basic helix-loop-helix family, inhibits mesodermal and promotes neuronal differentiation of P19 cells. Genes Dev. 11:2052–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani, L., M. Reedy, J.A. Airey, R. Gallo, M.T. Ciotti, G. Falcone, and S. Alema. 1996. Remodeling of cytoskeleton and triads following activation of v-Src tyrosine kinase in quail myotubes. J. Cell Sci. 109:1335–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo, E., and L. Conti. 1998. Generation and characterization of embryonic striatal conditionally immortalized ST14A cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 53:223–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo, E., and P.G. Pelicci. 1998. Emerging roles for SH2/PTB-containing Shc adaptor proteins in the developing mammalian brain. Trends Neurosci. 21:476–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalazonitis, A., J.A. Kessler, D.R. Twardzik, and R.S. Morrison. 1992. Transforming growth factor alpha, but not epidermal growth factor, promotes the survival of sensory neurons in vitro. J. Neurosci. 12:583–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti, L., C. De Fraja, M. Gulisano, E. Migliaccio, S. Govoni, and E. Cattaneo. 1997. Expression and activation of SH2/PTB-containing ShcA adaptor protein reflects the pattern of neurogenesis in the mammalian brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:8185–8190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, C.G., V. Tropepe, C.M. Morshead, B.A. Reynolds, S. Weiss, and D. van der Kooy. 1996. In vivo growth factor expansion of endogenous subependymal neural precursor cell populations in the adult mouse brain. J. Neurosci. 16:2649–2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon, J., S. Reid, R. Kinyamu, I. Opole, R. Opole, J. Baratta, M. Korc, T.L. Endo, A. Duong, G. Nguyen, M. Karkehabadhi, D. Twardzik, S. Patel and S. Loughlin. 2000. In vivo induction of massive proliferation, directed migration and differentiation of neural cells in the adult mammalian brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:14686–14691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah, M.H., J.M. Olson, H.B. Sucic, R.I. Hume, S.J. Tapscott, and D.L. Turner. 2000. Generation of neurons by transient expression of neural bHLH proteins in mammalian cells. Development. 127:693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, J.L., B.E. Berechid, F.B. Cutting, A. Presente, C.B. Chambers, D.R. Foltz, A. Ferreira, and J.S. Nye. 1999. Autonomous and non autonomous regulation of mammalian neurite development by Notch1 and Delta1. Curr. Biol. 9:1448–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, G., E. Alesse, L. Di Marcotullio, F. Zazzeroni, R. Gallo, M. Zani, L. Frati, I. Screpanti, and A. Gulino. 2001. EGF regulates a complex pattern of gene expression and represses smooth muscle differentiation during the neurotypic conversion of the neural-crest-derived TC-1S cell line. Exp. Cell Res. 264:353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golembo, M., R. Schwitzer, M. Freeman, and B.Z. Shilo. 1996. Argos transcription is induced by the Drosophila EGF receptor pathway to form an inhibitory feedback loop. Development. 122:223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritti A., A.L. Vescovi, and R. Galli. 2002. Adult neural stem cells:plasticity and developmental potential. J. Physiol. 96:81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan, K., H. Chang, A. Rolletschek, and A.M. Wobus. 2001. Embryonic stem cell-derived neurogenesis. Cell Tissue Res. 305:171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulisano, M., V. Broccoli, C. Pardini, and E. Boncinelli. 1996. Emx1 and Emx2 show different patterns of expression during proliferation and differentiation of the developing cerebral cortex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 8:1037–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, E., and D. Lane. 1988. Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 726 pp.

- Hassan, B.A., and H.J. Bellen. 2000. Doing the MATH: is the mouse a good model for fly development? Genes Dev. 14:1852–1865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janet, T., G. Ludecke, U. Otten, and K. Unsicker. 1995. Heterogeneity of human neuroblastoma cell lines in their proliferative responses to basic FGF, NGF, andEGF: correlation with expression of growth factors and growth factor receptors. J. Neurosci. Res. 40:707–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.E., K. Zimmerman, T. Saito, and D.J. Anderson. 1992. Induction and repression of mammalian achaete-scute homologue (MASH) gene expression during neuronal differentiation of P19 embryonal carcinoma cells. Development. 114:75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klesse, L.J., K.A. Meyers, and L.F. Parada. 1999. Nerve growth factor induces survival and differentiation through two distinct signalling cascades in PC12 cells. Oncogene. 18:2055–2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillien, L., and H. Raphael. 2000. BMP and FGF regulate the development of EGF-responsive neural progenitor cells. Development. 127:4993–5005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q., Z. Chen, I. del Barco Barrantes, J.L. de la Pompa, and D.J. Anderson. 1998. Neurogenin1 is essential for the determination of neuronal precursors for proximal cranial sensory ganglia. Neuron. 20:469–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark, M.D., Y. Liu, S.T. Wong, T.R. Hinds, and D.R. Storm. 1995. Stimulation of neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells by EGF and KCl depolarization: a Ca(2+)-independent phenomenon. J. Cell Biol. 130:701–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark, M.D., and D.R. Storm. 1997. Coupling of epidermal growth factor (EGF) with the antiproliferative activity of cAMP induces neuronal differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 272:17238–17244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, C.J. 1995. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell. 80:179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massari, M.E., and C. Murre. 2000. Helix-loop-helix proteins: regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:429–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison R.S., H.I. Kornblum, F.M. Leslie, and R.A. Bradshaw. 1987. Trophic stimulation of cultured neurons from neonatal rat brain by epidermal growth factor. Science. 238:72–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakafuku, M., and Y. Kaziro. 1993. Epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-alpha can induce neuronal differentiation of rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells under particular culture conditions. FEBS Lett. 315:227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinetti, A., R. Bassi, L. Riboni, and G. Tettamanti. 1997. Involvement of a ceramide activated protein phosphatase in the differentiation of neuroblastoma neuro2a cells. FEBS Lett. 414:475–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Represa, A., T. Shimazaki, M. Simmonds, and S. Weiss. 2001. EGF-responsive neural stem cells are a transient population in the developing mouse spinal cord. Eur. J. Neurosci. 14:452–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubinoff, B.E., P. Itsykson, T. Turetsky, M.F. Pera, E. Reinhartz, A. Itzik, and T. Ben-Hur. 2001. Neural progenitors from human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotech. 19:1134–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuldiner, M., O. Yanuka, J. Itskovitz-Eldor, D.A. Melton, and N. Benvenisty. 2000. Effects of eight growth factors on the differentiation of cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:11307–11312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Screpanti, I., D. Meco, S. Scarpa, S. Morrone, L. Frati, A. Gulino, and A. Modesti. 1992. Neuromodulatory loop mediated by nerve growth factor and interleukin 6 in thymic stromal cell cultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:3209–3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Screpanti, I., S. Scarpa, D. Meco, D. Bellavia, L. Stuppia, L. Frati, A. Modesti, and A. Gulino. 1995. Epidermal growth factor promotes a neural phenotype in thymic epithelial cells and enhances neuropoietic cytokine expression. J. Cell Biol. 130:183–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, L., Q. Ma, and D.J. Anderson. 1996. Neurogenins, a novel family of atonal-related bHLH transcription factors, are putative mammalian neuronal determination genes that reveal progenitor cell heterogeneity in the developing CNS and PNS. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 8:221–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajbakhsh, S., E. Vivarelli, G. Cusella-De Angelis, D. Rocancourt, M. Buckingham, and G. Cossu. 1994. A population of myogenic cells derived from the mouse neural tube. Neuron. 13:813–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajbakhsh, S., U. Borello, E. Vivarelli, P. Kelly, J. Papkoff, D. Duprez, M. Buckingham, and G. Cossu. 1998. Differential activation of Myf5 and MyoD by different Wnts in explants of mouse paraxial mesoderm and the later activation of myogenenesis in the absence of Myf5. Development. 125:4155–4162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threadgill, D.W., A.A. Dlugosz, L. Hansen, T. Tennenbaum, U. Lichti, D. Yee, C. Lamantia, T. Mourton, K. Herrup, R.C. Harris, et al. 1995. Targeted disruption of mouse EGF receptor: effect of genetic background on mutant phenotype. Science. 269:230–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacca, A., L. Di Marcotullio, G. Giannini, M. Farina, S. Scarpa, A. Stoppacciaro, A. Calce, M. Maroder, L. Frati, I. Screpanti, and A. Gulino. 1999. Thrombospondin-1 is a mediator of the neurotypic differentiation induced by EGF in thymic epithelial cells. Exp. Cell Res. 248:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccarino, F.M., Y. Ganat., Y. Zhang and W. Zheng. 2001. Stem cells in neurodevelopment and plasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 25:805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley, L.M., J.X. Wu, I. Harari, and E.D. Adamson. 1992. Epidermal growth factor receptor mRNA and protein increase after the four-cell preimplantation stage in murine development. Dev. Biol. 149:247–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.-X., and E.D. Adamson. 1993. Inhibition of differentiation in P19 embryonal carcinoma cells by the expression of vectors encoding truncated or antisense EGF receptor. Dev. Biol. 159:208–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.-X., and E.D. Adamson. 1996. Kinase-negative mutant epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression during embryonal stem cell differentiation favours EGFR-independent lineages. Development. 122:3331–3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong W., M.M. Jiang, G. Weinmaster, L.Y. Jan, and Y.N. Jan. 1997. Differential expression of mammalian Numb, Numblike and Notch1 suggests distinct roles during mouse cortical neurogenesis. Development.124:1887–1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]