Abstract

Summary: Bacteroides species are significant clinical pathogens and are found in most anaerobic infections, with an associated mortality of more than 19%. The bacteria maintain a complex and generally beneficial relationship with the host when retained in the gut, but when they escape this environment they can cause significant pathology, including bacteremia and abscess formation in multiple body sites. Genomic and proteomic analyses have vastly added to our understanding of the manner in which Bacteroides species adapt to, and thrive in, the human gut. A few examples are (i) complex systems to sense and adapt to nutrient availability, (ii) multiple pump systems to expel toxic substances, and (iii) the ability to influence the host immune system so that it controls other (competing) pathogens. B. fragilis, which accounts for only 0.5% of the human colonic flora, is the most commonly isolated anaerobic pathogen due, in part, to its potent virulence factors. Species of the genus Bacteroides have the most antibiotic resistance mechanisms and the highest resistance rates of all anaerobic pathogens. Clinically, Bacteroides species have exhibited increasing resistance to many antibiotics, including cefoxitin, clindamycin, metronidazole, carbapenems, and fluoroquinolones (e.g., gatifloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin).

INTRODUCTION

By a variety of measures, the species Homo sapiens is more microbial than human. Microorganisms comprise only a small, albeit significant, percentage of the body weight (between 2 and 5 pounds of live bacteria). However, in terms of cell numbers, we are about 10% human and 90% bacterial (308)! Further, the number of genes in our microbiome may exceed the number of human genes by two orders of magnitude (264, 308), making us genetically 1% human and 99% bacterial! Consequently, bacteria play a major role in bodily functions, including immunity, digestion, and protection against disease (208). Colonization of the human body by microorganisms occurs at the very beginning of human life (208), and many of these organisms become truly indigenous to the host.

The human colon has the largest population of bacteria in the body (in excess of 1011 organisms per gram of wet weight), and the majority of these organisms are anaerobes; of these, ∼25% are species of Bacteroides (226), the bacterial genus that is focus of this review. This review will summarize the current state of knowledge about Bacteroides species, the most predominant anaerobes in the gut. The aspects of these organisms that will be covered will include their role as commensal organisms (The Good); their involvement in human disease (The Bad); and information about their physiology, metabolism, and resistance mechanisms as well as a brief overview of clinical characteristics (The Nitty-Gritty).

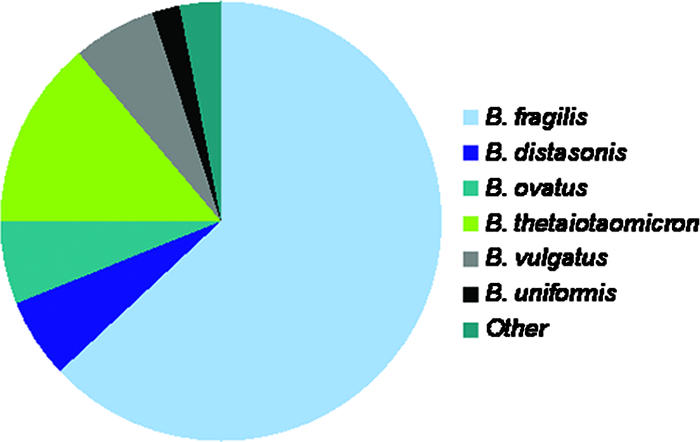

Bacteroidetes is one of the major lineages of bacteria and arose early during the evolutionary process (233). Bacteroides species are anaerobic, bile-resistant, non-spore-forming, gram-negative rods. The taxonomy of Bacteroides has undergone major revisions in the last few decades (see “Taxonomy” below), but the genus is now limited to species within the Bacteroides fragilis group, which now number >20. Names of species within the Bacteroides or Parabacteroides group to date are listed in Table 1 (146). Many of these species were isolated as single strains from human feces. The percentages of anaerobic infections that involve particular species of Bacteroides are indicated in Fig. 1 and were calculated from the Wadsworth Anaerobe Collection database, including more than 3,000 clinical specimens from which a Bacteroides species was isolated. The proportions of the most important species for the most common sites of isolation are indicated in Table 2. The numbers of B. fragilis isolates are 10- to 100-fold lower than those of other intestinal Bacteroides species, yet B. fragilis is the most frequent isolate from clinical specimens and is regarded as the most virulent Bacteroides species.

TABLE 1.

Species of the genera Bacteroides and Parabacteroides

| Species |

|---|

| Bacteroides |

| B. acidifaciens |

| B. caccae |

| B. coprocola |

| B. coprosuis |

| B. eggerthii |

| B. finegoldii |

| B. fragilis |

| B. helcogenes |

| B. intestinalis |

| B. massiliensis |

| B. nordii |

| B. ovatus |

| B. thetaiotaomicron |

| B. vulgatus |

| B. plebeius |

| B. uniformis |

| B. salyersai |

| B. pyogenes |

| B. finegoldii |

| B. goldsteinii |

| B. dorei |

| B. johnsonii |

| Parabacteroides |

| P. distasonis |

| P. merdae |

FIG. 1.

Proportions of Bacteroides species seen clinically.

TABLE 2.

Proportions of various species of the B. fragilis group found in anaerobic infections

| Site/specimen | No. of specimens | % of isolatesa

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. caccae | B. capillosus | B. distasonis | B. fragilis | B. merdae | B. ovatus | B. putredinis | B. stercoris | B. thetaiotaomicron | B. uniformis | B. vulgatus | B. fragilis group | Totalb | ||

| Abdominal (peritoneal) | 713 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 10.0 | 31.0 | 0.4 | 10.9 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 15.4 | 4.9 | 9.4 | 7.0 | 95.0 |

| Appendix | 490 | 3.5 | 0.4 | 10.2 | 26.7 | 0.6 | 11.4 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 16.3 | 4.5 | 9.2 | 11.0 | 96.5 |

| Blood | 286 | 4.9 | 61.2 | 5.2 | 12.2 | 5.2 | 2.4 | 91.3 | ||||||

| Buttock, hip, or groin rectal | 195 | 8.7 | 35.9 | 9.2 | 15.4 | 10.3 | 5.1 | 84.6 | ||||||

| Miscellaneous wound ulcer | 182 | 44.0 | 11.0 | 14.8 | 8.2 | 11.0 | 89.0 | |||||||

| Foot abscess or ulcer | 179 | 41.3 | 8.9 | 9.5 | 5.6 | 22.3 | 87.7 | |||||||

| Leg | 86 | 2.3 | 5.8 | 36.0 | 4.7 | 23.3 | 2.3 | 7.0 | 17.4 | 98.8 | ||||

| Bone | 72 | 8.3 | 2.8 | 33.3 | 12.5 | 19.4 | 6.9 | 12.5 | 95.8 | |||||

| Bronchial specimen (including TTA)c | 66 | 4.5 | 39.4 | 3.0 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 31.8 | 93.9 | ||||||

| Chest | 63 | 3.2 | 11.1 | 9.5 | 4.8 | 61.9 | 90.5 | |||||||

| Above the neck | 53 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 22.6 | 3.8 | 13.2 | 5.7 | 39.6 | 92.5 | |||||

| Urinary tract infection | 21 | |||||||||||||

| Obstetric/gynecological | 19 | |||||||||||||

| Liver | 19 | |||||||||||||

| Bile duct | 14 | |||||||||||||

| Stump wound | 14 | |||||||||||||

| Penis | 11 | |||||||||||||

| Brain | 8 | |||||||||||||

| Skin | 7 | |||||||||||||

| Blind loop | 5 | |||||||||||||

| Hand | 5 | |||||||||||||

| Oral | 4 | |||||||||||||

| Cerebrospinal fluid | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Heart | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Arm | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Hemovac tube | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Vertebrae | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Prostrate | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Lymph | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Total | 2,529 | |||||||||||||

Proportions of species were calculated for sites for which >50 specimens were documented.

The isolates enumerated account for >80% of infections.

TTA, transtracheal aspirate.

Bacteroides may be passed from mother to child during vaginal birth and thus become part of the human flora in the earliest stages of life (208). The bacteria maintain a complex and generally beneficial relationship with the host when retained in the gut, and their role as commensals has been extensively reviewed (308). A quote in a recent publication captured this attribute: “…with B. fragilis, as with real estate, it's location, location, location” (285). When the Bacteroides organisms escape the gut, usually resulting from rupture of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or intestinal surgery, they can cause significant pathology, including abscess formation in multiple body sites (e.g., the abdomen, brain, liver, pelvis, and lungs) as well as bacteremia.

Recent genomic and proteomic advances have greatly facilitated our understanding of the uniquely adaptive nature of Bacteroides species. The completion of the sequencing projects for B. thetaiotaomicron in 2003 (306) and B. fragilis in 2004 to 2005 (54, 138) and subsequent proteomic analyses have vastly added to our understanding of the manner in which these organisms adapt to, and thrive in, the human gut. A few examples are (i) complex systems to sense the nutrient available and tailor nutrient-metabolizing systems accordingly, (ii) multiple pump systems to rid the bacteria of toxic substances, and (iii) the ability to control the environment by interacting with the host immune system so that it controls other (competing) pathogens. We have recently shown that the expression of the various resistance-nodulation-division (RND) pumps of B. fragilis depends upon the site of isolation, another indication that the bacterium can tailor its disposal system according to its habitat (198). Additionally, comparisons of sequence analyses of the genomes of these two species suggested important mechanisms to explain the respective niches and characteristics of these organisms.

A few interesting facts that are common to both genomes have been noted. First, there is an unusually low gene content for their genome size, which reflects a large number of proteins containing >1,000 amino acids (308); many of these predicted proteins were assigned putative functions based on homology with known bacterial proteins (∼60% in B. thetaiotaomicron). Second, in both B. fragilis and B. thetaiotaomicron, extensive DNA inversions may control expression of a large number of genes. Third, both species exhibit multiple paralogous groups of genes, i.e., genes that seem to have derived from a common ancestral gene and have since diverged from the parent copy by mutation and selection or drift. The reasons for this seemingly inefficient use of genetic space are not completely clear, but it would seem that Bacteroides species are genetic “pack rats” that prefer to have all possibly needed versions of relevant proteins at hand and therefore will not need to rely on unpredictable mutations.

THE GOOD

Bacteroides as Friendly Commensals

A recent review suggested that commensal is too mild a term for the relationship of Bacteroides to its human host. The term commensal implies that one partner benefits from the relationship and the other is unaffected. The authors suggested that mutualism is a more apt description, since both the bacteria and the human experience increased fitness as a result of the relationship (8). The intestinal microbiome endows us with many features that we have not had to evolve ourselves, and we provide the organisms with “bed and board.”

Appearance in the GI tract.

Bacteroides species in the neonate appear at approximately 10 days after birth (251). Breast-fed infants do not show appreciable numbers of Bacteroides organisms in their stool until after they are weaned; in these newborns, Bifidobacterium is the major genus (150). Bacterial interactions with the host intestinal cells are facilitated by the presence of cellular and stromal components, blood, mucins, and neurons in the intestinal mucosal layer (208).

Nutrient sources for intestinal bacteria.

Polysaccharides comprise the most abundant biological polymer and, as such, also the most abundant biological food source. Carbohydrate fermentation by Bacteroides and other intestinal bacteria results in the production of a pool of volatile fatty acids that are reabsorbed through the large intestine and utilized by the host as an energy source, providing a significant proportion of the host's daily energy requirement (118). Thus, gut flora provide nutrient sources for the host as well. Studies show that germfree animals lacking a gut flora need 30% more calories to maintain body mass than normal rats (104); the gut bacteria liberate and generate simplified carbohydrates, amino acids, and vitamins. Other organisms in the gut, without the array of sugar utilization enzymes that Bacteroides has, can benefit from the presence of Bacteroides by using sugars (generated by the glycosylhydrolases) that they would otherwise be unable to use (264). For example, Bifidobacterium longum has a better system for importing simple sugars than does B. thetaiotaomicron, but B. thetaiotaomicron can break down a large variety of glycosidic bonds, providing nutrients that B. longum can then use. Also, studies with mice indicate that B. thetaiotaomicron can redirect its carbohydrate-utilizing capability from dietary to host polysaccharides according to nutrient availability (265). In another study, the adaptation of B. thetaiotomicron to utilize different nutrients during the suckling and weaning periods was investigated (27). Transcriptome analysis indicated that B. thetaiotaomicron harvested from the ceca of suckling mice has increased expression of enzymes that can utilize host-derived polysaccharides (host glycans, hexoseamines, and sialic acids that are present in mucus and the underlying gut epithelium), as well as enzymes to aid in the catabolism of mono-and oligosaccharides present in mother's milk. After weaning, the repertoire of sugar-digesting metabolic enzymes was expanded so that plant-derived polysaccharides (which would now be present in the gut) could be utilized (27).

Adaptive survival in the GI tract.

Bacteroides species have a superb ability to utilize the nutrients at hand. In the large intestine, these bacteria utilize simple and complex sugars and polysaccharides for growth (118). At sites of infection, B. fragilis may utilize host cell surface glycoproteins and glycolipids as a nutrient source; these may include simple sugars such as galactose and mannose and more complex compounds (e.g., N-acetyl-d-glucosamine [NAG]) and N-acetylneuraminic acids). Indeed, the largest paralogous group of proteins in B. thetaiotaomicron are those involved in oligo- and polysaccharide uptake and degradation (2, 3, 58, 59, 72, 73, 156, 206, 207, 229, 247, 248, 276), capsular biosynthesis, and environmental sensing/signal transduction/DNA mobilization (306). The authors of the B. thetaiotaomicron genome sequence publication suggest that these expansions “reveal strategies used by B. thetaiotaomicron to survive and to dominate in the densely populated intestinal system” (306). The coupling of these paralogs with a variety of regulatory apparatus may explain the exquisitely tuned ability of Bacteroides to sense and adapt to environmental changes and stresses, such as would normally be encountered in the gut. Another system used by Bacteroides to adapt to the human gut is its ability to modulate its surface polysaccharides by “flipping” the promoters needed for their expression to an “on” or “off” position (137); this ability may allow it to evade a host immune response.

Carbohydrate metabolism in B. thetaiotaomicron.

B. thetaiotaomicron has an extensive starch utilization system and multiple genes (sus genes) that are involved in starch binding and utilization. One hundred seventy-two glycosylhydrolases and 163 homologs of starch binding proteins (106 members homologous to SusC and 57 members homologous to SusD [306, 308]) enable the organisms to use the wide variety of dietary carbohydrates that might be available in the gut. Nearly half of the genes encoding the starch binding proteins (SusC homologs) are located next to glycosylhydrolase genes. In all, B. thetaiotaomicron contains more glycosylhydrolases than any sequenced prokaryote and appears to be able to cleave most of the glycosidic bonds found in nature (307). This ability to adapt to the use of different nutrient sources undoubtedly gives it an “edge” in its intestinal environment. These proteins may also be important in the attachment of the organism to mucus glycans.

Carbohydrate metabolism in B. fragilis.

The polysaccharide-utilizing ability of B. fragilis has not been as extensively studied, although analysis of the proteome of B. fragilis and comparison with B. thetaiotaomicron also suggests a tremendous capacity to use a wide range of dietary polysaccharides. A few years ago, we characterized a 200-kDa two-component protein (Omp200 [composed of Omp120 and Omp70, corresponding to their respective apparent molecular masses]). The intact two-component system had pore-forming ability in liposomes and black lipid bilayer membranes (two artificial systems that mimic the outer membrane of the cell and can measure pore formation). The 120-kDa component of this porin had significant homology to B. thetaiotaomicron SusC proteins (301). While Omp71 had no detectable similarity to SusD, it had homologs in the B. thetaiotomicron genome that are positioned next to a SusC homolog. Xu and Gordon speculated that the B. fragilis SusC-like component may be a conserved component of multifunctional outer membrane proteins. These multifunctional complexes may be divided into two groups: those with a downstream susD homolog that may affect acquisition/utilization of polysaccharides and those with homologs of omp71, encoding a protein whose function has not yet been defined (308).

The B. fragilis neuraminidase enzyme (product of the nanH gene) catalyzes the removal of terminal sialic acid from surface polysaccharides (105), and nanH mutants are often growth deficient. Because NAG is used in cell wall production, the ability to use extracytoplasmic NAG facilitates cell growth (181). Possibly, neuraminidase activity may render other carbon sources available when glucose levels are reduced (105), thus serving the nutritional requirements of the bacterium.

Miscellaneous enzymes used in sugar transport or utilization.

Many bacteria have transport-linked phosphorylation systems that allow sugars transported into the cells to be immediately utilized in pathways for energy metabolism or biosynthesis; any sugar transported across the cell membrane by these phosphotransfer systems can immediately enter metabolic or biosynthetic pathways. Genes for these systems were not found in the genome of either B. fragilis or B. thetaiotaomicron. Thus, they must have alternate ways of transporting sugars into the cell and attaching an active phosphate moiety. Recently, two broad-specificity hexokinases from B. fragilis were characterized, and their roles in hexose and NAG utilization were studied (31). These enzymes allow utilization of nutrients found in the gut (undigested dietary polysaccharides and host-derived glycoproteins) and at sites of infection (host cell surface antigens [including the Lewis antigen] and glycolipids) (31).

Association of levels of intestinal Bacteroides with obesity.

During the last 2 years, there have been a number of reports in prominent journals pointing out that the respective levels of the two main intestinal phyla, the Bacteroidetes and the Firmicutes, are linked to obesity, both in humans and in germfree mice (102, 143, 144, 280). The authors of the studies deduce that carbohydrate metabolism is the important factor. They observe that the microbiota of obese individuals are more heavily enriched with bacteria of the phylum Firmicutes and less with Bacteroidetes, and they surmise that this bacterial mix may be more efficient at extracting energy from a given diet than the microbiota of lean individuals (which have the opposite proportions) (280). In some studies, they found that the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes increases as obese individuals lose weight and, further, that when the microbiota of obese mice are transferred to germfree mice, these mice gain more fat than a control group that received microbiota from lean mice (280). Until very recently, reports in the literature agreed that B. thetaiotaomicron had more glycosylhydrolases than any sequenced prokaryote and appeared to be able to cleave most of the glycosidic bonds found in nature (307). However, the most recent genomic analysis found that environmental gene tags coding for many enzymes involved in the initial steps in breaking down otherwise indigestible dietary polysaccharides were enriched in obese mice (note that these were ob/ob homozygous mice with a defective leptin gene as well). The genome of Eubacterium rectale (a member of the Firmicutes division), which has not been completed, is significantly enriched for glycoside hydrolases compared to several completed genomes of Bacteroides species (280).

While it is not completely clear how significant these differences are or how well they will translate into human equivalents (9), they have, in fact, been extended to the human diet. A very recent study found that diets that are based on a high intake of protein but a low intake of fermentable carbohydrate (e.g., many of the popular diets, including Atkins, South Beach, etc.) may alter the gut flora. These workers found that proportions of Bacteroides and several clusters of Clostridia were not altered but that numbers of Roseburia, Eubacterium rectale, and bifidobacteria decreased significantly as carbohydrate intake decreased (79). Furthermore, human colonic butyrate-producing organisms that are related to Roseburia spp. and Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens showed an increased ability to use a variety of starches for growth compared to B. thetaiotaomicron (202).

Adaptation of B. thetaiotomicron and B. fragilis to their respective microenvironments.

While both B. thetaiotaomicron and B. fragilis contain large numbers of paralogous genes, comparison of the two genomes suggests that they are specifically tailored for their respective microenvironments. For example, B. fragilis has a pronounced capacity to create variable surface antigenicities by multiple DNA inversion systems (138). This surface-altering capability is more developed in B. fragilis, which is more frequently found at the mucosal surface (i.e., often the site of attack by host defenses) than is B. thetaiotaomicron. Also, the ability of B. fragilis to tolerate and use oxygen may account for the observation that it is found in greatest numbers at the mucosal surface, where the PO2 should be higher than it is within the intestinal lumen (13). The impressive capacity to utilize polysaccharides is more pronounced in B. thetaiotaomicron, which is more concentrated within the colon. The multiplicity of sensing systems of B. thetaiotaomicron, discussed below, also allow fine-tuned and efficient recruitment of the appropriate carbohydrate utilization systems. This was aptly illustrated by a very recent study that demonstrated adaptations in B. thetaiotomicron in the guts of mice during the suckling period and after weaning. By analyzing whole-genome transcriptional profiles of the bacterium harvested from the intestines of mice at different time points, the authors demonstrated that in sucking animals, glucose/galactose transporters and other glycosidases (enzymes that would be important in using host glycans sources) were expressed at higher levels, whereas B. thetaiotaomicron harvested from mice in the weaned stage showed increased expression of genes for enzymes that can liberate sugars from plant polysaccharides. Thus, during the suckling period, B. thetaiotomicron preferentially used host-derived polysaccharides as well as mono-and oligosaccharides present in mother's milk, and after weaning, this organism expanded its metabolism to exploit abundant polysaccharides of plant origin (27).

Environmental Sensing Systems

Beneficial symbiosis requires that the bacteria can sense changes in the environment so that they can adapt to alterations in their surroundings. The genome studies of B. thetaiotaomicron reveal that they have multiple genes encoding signal sensing systems; these include σ-factors and two-component regulatory systems. The function of these systems in Bacteroides is not understood to the extent that they are understood in aerobic bacteria, but indications are that they serve similar functions.

ECF σ-factors.

σ-factors are essential dissociable protein subunits of prokaryotic RNA polymerase that are necessary for initiation of transcription. These factors provide promoter recognition specificity to the polymerase and contribute to DNA strand separation; they then dissociate from the RNA polymerase core. In some cases the factor may regulate large numbers of prokaryotic genes, and in some cases the genes comprising a sigma factor regulon have a clearly defined function (131). One class of these factors, the extracytoplasmic function σ-factors, known as ECF-type σ-factors, are relatively small proteins (65). They are frequently associated with specific membrane-tethered cognates, known as anti-σ-factors. This cognate may receive a signal causing it to release its σ-factor; the released σ-factor can then interact with RNA polymerase to initiate transcription.

B. thetaiotaomicron contains the largest proportion and number of ECF σ-factors among the species of Bacteria and Archaea for which complete genome data are available (307). Approximately half of the ECF σ-factor genes are located next to open reading frames encoding putative anti-σ-factors. Further, all but one of these ECF σ-factor/anti σ-factor pairs is located upstream of open reading frames encoding homologs of the polysaccharide binding susC gene products. While the starch binding proteins are located on the cell surface, the starch-degrading enzymes are located in the periplasm, perhaps to allow Bacteroides exclusive access to the substrate (3). However, genomic analysis of B. thetaiotomicron identified a host of glycosyl hydrolases (α-galactosidases, β-galactosidases, α-glucosidases, β-glucosidases, β-glucuronidases, β-fructofuranosidases, α-mannosidases, amylases, and endo-1,2-β-xylanases, plus 14 other activities); 61% of these glycosylhydrolases are predicted to be in the periplasm or outer membrane or to be extracellular and may be important in shaping the nutrient availability of the intestinal ecosystem (306). Taken together, these results suggest a finely tuned regulatory system that allows B. thetaiotaomicron to sense the nutrients at hand and adjust its metabolism accordingly, thus benefiting (i) itself, (ii) other bacteria that cannot utilize the complex polysaccharide, and (iii) the human host, who obtains 10 to 15% of his/her caloric intake through microbial fermentation of oligosaccharides (307).

Two-component signal transduction systems.

The architecture and regulation of two component signal transduction systems have been extensively studied (268). These systems allow organisms to sense and respond to changes in many different environmental conditions. The prototype structure is well conserved and includes a histidine protein kinase that is regulated by environmental stimuli. In response to a stimulus, this protein autophosphorylates at a histidine residue, creating a high-energy phosphoryl group. The phosphoryl group is subsequently transferred to an aspartate residue in the response regulator protein; this induces a conformational change in the regulatory domain that results in activation of an associated downstream domain and causes the response (268). The majority of response regulators are transcription factors with DNA-binding effector domains, although some have C-terminal domains that function as enzymes. Examples of this system include regulation of the differential expression of ompF and ompC by the EnvZ-OmpR system in Escherichia coli and of the commitment to sporulation by the Spo system in Bacillus subtilis (268). While there are few functional studies of these systems in Bacteroides, it is reasonable to assume that they are similar to those described for other organisms. For example, expression of a two-component regulatory system gene from Bacteroides that was cloned into a multicopy plasmid vector in E. coli resulted in a decrease in the level of the outer membrane porin protein OmpF and an increase in the level of the outer membrane porin protein OmpC (204).

One Bacteroides two-component regulatory system which has been extensively studied is the RteA-RteB two-component system. The tetracycline resistance gene, tetQ, is part of the rteA-rteB-tetQ operon, which is located on a mobile element (CTnDot [see below]) found in many strains of Bacteroides. RteA is the sensor component, and RteB is the transcriptional regulator that controls the expression of a third downstream gene, rteC. The RteC product, in turn, controls the expression of a gene cluster (orf2C) that is important for excision (and therefore of transfer) of the CTnDot element. Tetracycline has a stimulatory effect on expression of the RteA-RteB system and, therefore, on both expression and transfer of tetracycline resistance. However, the rteA gene is not directly sensing tetracycline, and exactly what it is sensing is not yet clear (164).

In addition to the sizeable numbers of classical two-component systems (i.e., sensor kinases and response regulators), there is a family of 32 unique proteins in B. thetaiotaomicron that incorporate all of the domains found in the classical two-component system into a single polypeptide. In one system, nutrient sensing is coupled to regulation of monosaccharide metabolism (263). BT3172 belongs to this family of proteins, and its expression is regulated by polysaccharides in the environment. The presence of α-mannosides in the medium can induce expression of BT3172, which, in turn, will cause upregulated expression of secreted α-mannosidases. This system may also be important for capsular polysaccharide gene expression. Typically, expression of one of the capsular polysaccharide synthesis loci (cps3) is upregulated when polysaccharides are scarce. In a mutant deficient in BT3172, expression of cps3 is increased even in the presence of a medium rich in polysaccharides, suggesting that BT3172 is important for the bacterium to properly interpret its nutrient landscape in terms of adequate supply of polysaccharides (263).

Another feature of the ability of BT3172 to sense the neighboring polysaccharide landscape is that it can modulate “mimicry” so that the surface polysaccharide structure of the bacterium can be altered to match the surrounding landscape, possibly allowing the bacterium to avoid eliciting a host immune response (68).

Cross talk between Bacteroides and the intestinal cells.

Most of the characteristics of Bacteroides discussed to this point pertain to the adaptability of Bacteroides to its environment and changes that occur as a result of alterations in that environment. However, this is a two-way communication system, and studies have shown that the intestinal Bacteroides strains directly modulate gut function (94). Almost a decade ago, Hooper et al. demonstrated that B. thetaiotomicron can modify intestinal fucosylation in a complex interaction mediated by a fucose repressor gene and a signaling system (121). Subsequently, using transcriptional analysis, they demonstrated that B. thetaiotaomicron could modulate expression of a variety of host genes, including those involved in nutrient absorption, mucosal barrier fortification, and production of angiogenic factors (120). The line of communication from bacterium to intestinal cell can morph into a complete circle: B. thetaiotaomicron can stimulate production of RegIIIγ, a bactericidal lectin, which can then bind directly to bacterial peptidoglycan in gram-positive bacteria and result in bacterial killing (53).

Interactions with the Immune System

There are numerous studies detailing the host immune response to bacterial virulence factors. However, the vast majority of human-bacterial interactions are benign and commensal or mutualistic in nature. Intestinal bacteria are important in the development of gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT): in the absence of bacterial colonization, development of GALT is defective (117). In rabbits, the combination of B. fragilis and Bacillus subtilis consistently promoted GALT development and led to development of the preimmune antibody repertoire (212). Mazmanian and Kasper reviewed the factors that allow the GI tract—an environment with multiple immune capabilities—to coexist with the huge numbers of bacteria found there (154) and proposed a model whereby the immune capabilities of the GI tract are profoundly affected by some of those bacteria. The general outline of this model is described below.

Polysaccharides produced by B. fragilis are important in the activation of the T-cell-dependent immune response.

A zwitterionic polysaccharide (ZPS) produced by B. fragilis can activate CD4+ T cells (i.e., T helper cells expressing the CD4 [cluster of differentiation 4] glycoprotein). Polysaccharides A and B (PS-A and PS-B) of the B. fragilis capsular polysaccharide complex are both ZPSs. Normally, polysaccharides (which almost never carry a positive charge) are considered activators of B cells, and they promote increased immunoglobulin M (IgM) production but without IgG production and without a memory response. However, the unusually structured ZPSs can bind onto the borders of the peptide-binding groove on major histocompatibility complex class II molecules of the antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and dock in this groove, and they can thus be presented to the T-cell receptors of CD4+ T cells in the same way that a peptide or glycopeptide conjugate would be presented. Experimental data indicate that these ZPSs are internalized by the APCs, processed by chemical oxidation into smaller fragments, and then presented to the T cell at the surface of the APC. Indeed, these ZPSs appear to be important in the development of CD4+ T cells. Splenocytes from germfree mice showed a lower proportion of CD4+ cells than splenocytes from conventionally colonized mice, and colonization with B. fragilis (even in the absence of all the other gut microflora) could correct this proportion in the germfree animals. Moreover, colonization with a mutant that could not produce PS-A was not able to correct the defect, whereas PS-A alone could also correct the defect (154, 155).

The CD4+ T cells stimulated by PS-A produce interleukin-10 (IL-10), which can act to prevent abscess formation and other inflammatory responses. Also, in either in vivo or in vitro experiments, these PS-A-stimulated cells also produce gamma interferon, IL-2, and IL-12. The studies accomplished by this group reveal an intricate “dance” between the microbe and certain components of the host immune system, and the authors conclude that the PS-A of B. fragilis “is necessary and sufficient to mediate the generation of a normal mature immune system” (154).

Gut bacteria and the “hygiene hypothesis.”

There have been reports that modulation of the immune system by the commensal gut bacteria is important in allergy development. One scenario is that increases in vaccination, antibiotic usage, and disinfectant use decrease the gut flora at an important point in the development of the immune system, which results in a skewing of the immune system toward TH2 cell response and overproduction of TH2 cytokines and IgE; the innate immune mechanisms and TH1, TH2, and regulatory T cells are all part of this fine balancing act (210). The specific bacterial determinants of this phenomenon are not clear. Mazmanian and Kasper suggest that B. fragilis PS-A may be involved (154). Others suggest that lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (not necessarily Bacteroides LPS), which at low levels is an inducer of IL-12 and gamma interferon (cytokines that stimulate TH1-mediated immunity and decreases the production of TH2 inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13), is part of this process (293).

Bacteroides can affect expression of Paneth cell proteins.

Small intestinal crypts house stem cells that serve to constantly replenish epithelial cells that die and are lost from the villi. Paneth cells (immune systems cells similar to neutrophils), located adjacent to these stem cells, protect them against microbes by secreting a number of antimicrobial molecules (defensins) into the lumen of the crypt (97), and it is possible that their protective effect even extends to the mature cells that have migrated onto the villi (97). In animal models, B. thetaiotaomicron can stimulate production of an antibiotic Paneth cell protein (Ang4) that can kill certain pathogenic organisms (e.g., Listeria monocytogenes) (119). In newborn mice, B. thetaiotaomicron promotes angiogenesis and postnatal development (266).

Limiting Colonization of the GI Tract by Pathogens

Studies by Wells and colleagues indicate that anaerobic bacteria play a pivotal role in limiting the translocation of normal intestinal bacteria but that other bacterial groups also have a role in preventing the intestinal colonization and translocation of potential pathogens (295). Recent studies suggest that Bacteroides, and possibly specific species of Bacteroides, have a role in preventing infection with Clostridium difficile (122, 123). As detailed above, the development of the immune response that limits entry and proliferation of potential pathogens is profoundly dependent upon B. fragilis. Also as mentioned, Paneth cell proteins may produce antibacterial peptides in response to stimulation by B. thetaiotomicron (119), and these molecules may prevent pathogens from colonizing the space. In addition, B. thetaiotomicron can induce Paneth cells to produce a bactericidal lectin, RegIIIγ, which exerts its antimicrobial effect by binding to the peptidoglycan of gram-positive organisms (53).

TRANSITION: FROM COMMENSAL TO PATHOGEN

As outlined above, Bacteroides species are normally commensals in the gut flora. However, these organisms can also be responsible for infections with significant morbidity and mortality. A similar scenario is found with the “commensal gone bad” (186), i.e., Enterococcus faecalis. E. faecalis is normally a benign resident of the gut flora. However, the first vancomycin-resistant enterococcal strain had a number of DNA elements, apparently of foreign origin, which comprised a quarter of the genome of that strain (186). These elements included a variety of resistance determinants as well as a pathogenicity island carrying a number of virulence-associated genes. Thus, there may be considerable “sharing” of genes within the crowded neighborhood of the gut flora. Acquiring genes that favor the “new” resident (e.g., genes that code for improved adhesion, new nutrition pathways, antibiotic resistance, and inhibition of host defenses) will give these organisms an edge in establishing a niche for themselves. Indeed, some bacteria may not even need to acquire new genes. Organisms such as Bacteroides with such a large genome bank at their disposal may simply need to turn on certain genes (such as those involving new nutrition pathways, efflux pumps to rid the cell of toxic substrates, or new surface epitopes) to change from friendly commensal to dangerous threat (104).

Additionally, the capsular polysaccharide of B. fragilis, which is so important in development of the host immune system, is also responsible for abscess formation; it is thus one of the most important virulence determinants in this bacterium and is the most obvious bacterial element that is both “friend and foe.”

The proportions of various species of the B. fragilis group found in anaerobic infections are given in Table 2.

THE BAD

Virulence

Although B. fragilis accounts for only 0.5% of the human colonic flora (190), it is the most commonly isolated anaerobic pathogen, due in part to its potent virulence factors. Virulence factors can generally be subdivided into three broad categories: those involved in (i) adherence to tissues, (ii) protection from the host immune response (such as oxygen toxicity and phagocytosis), or (iii) destruction of tissues. Bacteroides strains may possess all of these characteristics. The fimbriae and agglutinins of B. fragilis function as adhesins, allowing them to be established in the host tissue. The polysaccharide capsule, LPS, and a variety of enzymes protect it from the host immune response. The capsule is responsible for abscess formation, and histolytic enzymes found in B. fragilis can mediate tissue destruction.

The bacterial capsule.

The capsule of B. fragilis initiates a unique immune response in the host: abscess formation. The actual formation of the abscess is an example of a pathological host response to the invading bacterium: a fibrous membrane localizes invading bacteria and surrounds a mass of cellular debris, dead polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and a mixed population of bacteria (282). Abscesses left untreated can expand and can even cause intestinal obstruction, erosion of resident blood vessels, and ultimately fistula formation. Abscesses may also rupture and result in bacteremia and disseminated infection.

B. fragilis is the only bacterium that has been shown to induce abscess formation as the sole infecting organism. Abscess formation has been clearly linked to the B. fragilis capsule in an animal model (282). Injection of capsules alone was sufficient to induce abscess formation (67), while systemic injection prevented abscess formation in rats, presumably due to antibody development and subsequent protection (281). Responses to most other polysaccharide antigens are T-cell independent, but abscess formation induced by B. fragilis is dependent on T cells (243-245, 310).

The B. fragilis capsule was first analyzed with a prototype strain. Two distinct high-molecular-weight polysaccharides (PS-A and PS-B) that are coexpressed were described (179, 283), and the structures of these two polysaccharides were elucidated (14). PS-A is made up of repeating tetrasaccharide units, and PS-B is made up of repeating hexasaccharide units (283, 289). Other strains of B. fragilis were subsequently analyzed, and all possessed a complex capsular polysaccharide composed of at least two different polysaccharides; these polysaccharides were antigenically diverse, although some cross-reactivity with the prototype capsular polysaccharide was seen (180). A third capsular polysaccharide (PS-C) was also found, and the biosynthetic loci involved were cloned and sequenced (67, 129).

The assignment of specific biosynthetic loci (involving up to 22 genes/locus) to specific polysaccharides has been amended since first described (67), but the basic features of the complex polysaccharides remain. The most predominant feature of these polysaccharides is the presence of both positively and negatively charged groups on each repeating unit. The two polysaccharides have very different net charges at physiological pH and exhibit variable expression on the bacterial cell surface (180). The zwitterionic motif is necessary for the activities of this group of molecules, including promoting the formation of abscesses (282). The structural basis of the abscess-modulating activity of the polysaccharide has been extensively studied; one model suggests that grooves in the polysaccharide may serve as “docking sites” for α-helices of specific molecules (e.g., immunomodulating molecules such as major histocompatibility/antigen molecular complexes) and thus trigger specific T-cell responses which then lead to abscess formation (289).

There are various opinions concerning the prevalence of capsule among clinical isolates of B. fragilis (48, 180, 193); one possible explanation is that different staining techniques will detect capsule to different extents (180). Electron micrographs reveal that even within an individual strain of B. fragilis, one might observe a large capsule, a small capsule, and noncapsulate variants. The large capsule and unencapsulated strains share antigenic epitopes, but the bacteria with small capsules are different. Intra- and interstrain antigenic variation was noted (184), and this variation has been observed in clinical isolates from a variety of anatomical sites and different geographical locations and also in bacteria grown in an in vivo model of peritoneal infection (184). Expression of the different capsular types is inheritable, since populations can be enriched for their particular type by subculture from different layers of density gradients. In some bacteria that appear noncapsulate, an additional electron-dense layer might be visible adjacent to the outer membrane.

Evasion of host immune response.

The ability to evade the host immune response certainly contributes to the virulence of a bacterium. The B. fragilis capsule can mediate resistance to complement-mediated killing and to phagocytic uptake and killing (98, 209, 252). Recent studies indicate that B. fragilis may interfere with the peritoneal macrophages, the first host immunologic defense response to rupture of the intestine or other compromise of the peritoneal cavity (287). Macrophages are important for early immune responses to invading microorganisms, and the production of nitric oxide (NO) is central to this function. NO is generated by inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) following exposure to certain cytokines (e.g., gamma interferon). These cytotoxic radicals enhance microbicidal function but can also act on host cells to produce cell necrosis or death. In the study mentioned above, macrophages activated by interaction with B. fragilis showed decreased NO production, decreased iNOS activity, and colocalization of iNOS and actin filaments in the macrophage cytoskeleton, along with pore formations not seen in the control cells. The authors concluded that the infection of macrophages with B. fragilis leads to actin filaments and iNOS extrusion through the pore formations, thus allowing the bacteria to evade killing by the macrophages.

Another remarkable feature of Bacteroides is its ability to modulate its surface polysaccharides. The production of these polysaccharides is regulated by a reversible inversion of the DNA segment containing the promoter needed for their expression to an “on” or “off” position (137). These inversions are mediated by invertase genes; mpi, the best known of these genes, codes for a global DNA invertase that is involved in inverting 13 distinct DNA regions, including the promoters of seven of the capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis regions (69). By changing its surface architecture, Bacteroides may avoid the host immune response; other potential effects of surface modification would include the ability to colonize host tissue or form biofilms.

Enzymes implicated in virulence.

Proteases of B. fragilis have been implicated in destroying brush border enzymes (214); these enzymes on the microvillus membranes aid in the final digestion of food and in mechanisms that provide for the selective absorption of nutrients. The most widespread histolytic enzymes in B. fragilis include hyaluronidase and chondroitin sulfatase, which attack the host extracellular matrix (222). Some strains produce other histolytic (e.g., fibrinogenolytic) enzymes (57). Two hemolysins (HlyA and HlyB) have been characterized in B. fragilis; these are two-component cytolysins that act together in hemolysis of erythrocytes (216).

Neuraminidase, the product of the nanH gene in Bacteroides species, cleaves mucin polysaccharides and enhances growth of the bacterium by generating available glucose (105). This enzyme is found in many pathogenic bacteria and is generally considered a virulence factor (223), and many strains of B. fragilis produce neuraminidase (22, 274). Neuraminidase can catalyze the removal of the sialic acid from host cell surfaces and from important immunoactive proteins such as IgG and some components of complement and may consequently disrupt important host functions (237).

Enterotoxin.

The B. fragilis enterotoxin (BFT) is a zinc metalloprotease (136, 162) and may destroy the zonula adherens tight junctions in intestinal epithelium by cleaving E-cadherin (303), resulting in rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton of the epithelial cells and loss of tight junctions. The result is that this barrier leaks and results in diarrhea (303). More recent evidence indicates that this action is initiated when BFT binds to a specific receptor other than E-cadherin (305). BFT is secreted by enterotoxigenic B. fragilis (ETBF) strains, which encode three isotypes of BFT on distinct bft loci, carried on a 6-kb genome segment unique to these strains, called the B. fragilis pathogenicity island (238).

There is evidence that the enterotoxin pathogenicity island is contained within a novel conjugative transposon (91). This pathogenicity island is flanked by genes encoding mobilization proteins (92) and may thus be transmissible to nontoxigenic strains. A recent study found that 57% of blood culture isolates contained the pathogenicity island and/or its flanking segments (19% had both and 38% had just the flanking segments). Comparatively, in B. fragilis isolates from other clinical sources, 10% had both the pathogenicity island and flanking segments, 43% had only the flanking segments, and 47% had neither. The authors deduced that the pathogenicity island and the flanking elements may be general virulence factors of B. fragilis (61). BFT also induces cyclooxygenase 2 and fluid secretion in intestinal epithelial cells (133). Finally, BFT has a possible role as a carcinogen in colorectal cancer (277).

The presence of the BFT gene is generally detected by PCR techniques (246). In a study of strains from Germany and from southern California, blood culture isolates were more likely to carry the enterotoxin gene than were other isolates (62). There is some association of ETBF and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), although rigorous, clear-cut correlation has not been demonstrated (12, 192). While the enterotoxin gene was not found in patients with inactive IBD, 13% of patients with IBD and 19% of patients with active disease were toxin positive. For an exhaustive description of ETBF, see the review by Sears (238).

Endotoxin/LPS.

LPS in B. fragilis has an unusual structure (291) and is 10 to 1,000 times less toxic than that of E. coli. Thus, it is generally not referred to as “endotoxin,” although it does have a demonstrable toxicity (71). The induction of endotoxin liberation on exposure to antibiotics was many times higher with B. fragilis than with the other species of the B. fragilis group, which may also help to explain why this species is particularly associated with clinical infections and higher mortality (221). Both LPS and capsule may also function as adhesins that allow the bacterium to become established at the site of infection (15).

Aerotolerance of Bacteroides.

Aerotolerance is not an obvious virulence factor, but it is likely that the ability to survive oxidative stresses plays a role in its ability to initiate or persist in infection (253). Further discussion of the oxidative stress response in Bacteroides is found later in this review.

Infections in Adults

Anaerobic infections are usually polymicrobial, and Bacteroides fragilis is found in most of these infections, with an associated mortality of more than 19% (107). If a documented B. fragilis infection is left untreated, the mortality rate is reported to be about 60% (107). This mortality rate can be greatly improved, however, with use of appropriate antimicrobial therapy (107). Therefore, therapeutic regimens are normally designed to cover this species.

Intra-abdominal sepsis.

Intra-abdominal sepsis is the most common infection caused by Bacteroides. After disruption of the intestinal wall, rupture of the diverticula, or other perforations due to a surgical wound, malignancies, or appendicitis, members of the normal flora infiltrate the normally sterile peritoneal cavity, and the resultant infections reflect the gut flora composition. During the early, acute stage of infection (approximately 20 h), the aerobes, such as E. coli, are the most active members of infection, establishing preliminary tissue destruction and reducing the oxidation-reduction potential of the oxygenated tissue. Once sufficient oxygen has been removed to allow the anaerobic Bacteroides species to replicate, these bacteria begin to predominate during the second, chronic stage of infection.

Perforated and gangrenous appendicitis.

Detailed bacteriologic studies performed in our laboratory recovered more than 20 genera and 40 species of organisms from specimens taken from patients with gangrenous and perforated appendicitis (21); B. fragilis and E. coli were the most frequently recovered anaerobic and aerobic species, respectively. B. thetaiotaomicron was also frequently recovered (in more than 70% of the specimens). The other species of the B. fragilis group were also found but in lower percentages of specimens.

Gynecological infections.

Bacteroides species are not part of the normal flora of the vagina but are occasionally isolated from vaginal cultures. The rates of vaginal carriage of Bacteroides in healthy women (both pregnant and nonpregnant) were estimated to be between 0 and 6% (142, 145), but this rose to 16% in women in labor (141) and to 27 to 28% in patients with cervicitis (145). In a study of 120 pregnant women attending a hospital in Warsaw, Poland, several distinct subgroups of B. fragilis were found, including one ETBF strain, which was genetically different than ETBF strains obtained from other sources (142).

Pelvic infections in which B. fragilis is likely to be involved are often characterized by the presence of an abscess (175); B. fragilis has been isolated from Bartholin's abscess (an abscess in the glands at the side of the vaginal opening) (45) as well as abscesses in the ovaries or fallopian tubes (23). In a large study assessing risk factors for intrauterine growth retardation, colonization of the cervix and/or vagina with Bacteroides, Porphyromonas, and Prevotella was significantly associated with intrauterine growth retardation (100). In a study of 39 women with mild to severe pelvic inflammatory disease, B. thetaiotaomicron was recovered from the endometria or Fallopian tubes of several women with moderate to severe pelvic inflammatory disease (116).

Skin and soft tissue infections.

Necrotizing soft tissue infections are typically polymicrobic. In one retrospective study of 196 patients, nearly half had mixed aerobic and anaerobic growth, and Bacteroides species were the most common organisms isolated (84). In our studies, Bacteroides was not the most common anaerobic organism isolated; nevertheless, 7% of the anaerobes belonged to the B. fragilis group (299). In general, the organisms found in soft tissue infections reflect the normal flora found in the adjacent region. A comprehensive study of the bacteriology of human bite wounds (which include clenched fist injuries) included multiple anaerobes, basically reflecting the oral flora (e.g., Prevotella, Fusobacterium, and Peptostreptococcus); Bacteroides was not reported in these specimens (158). In a study of infected dog and cat bites, 56% of specimens (50 dog bites and 57 cat bites) yielded both aerobes and anaerobes. B. fragilis was isolated from one patient with a dog bite and from one patient with a cat bite, and B. ovatus was isolated from one patient with a dog bite (272).

Endocarditis and pericarditis.

Involvement of anaerobic bacteria in endocarditis is unusual (26), but when it does occur it may have serious consequences (including valvular destruction, dysrhythmias, and cardiogenic shock), with a mortality rate of 21 to 43% (42). The predominant anaerobes in pericarditis are the B. fragilis group and probably occur from hematogenous spread (40). If B. fragilis is found, the most likely source is the GI tract; a literature review of endocarditis due to anaerobes reported 53 cases, and a variety of sources of the infecting organism, including a GI malignancy, liver abscess, ruptured appendix, and decubitus ulcer (26).

Bacteremia.

The incidence of anaerobic bacteremia decreased in the 1980s but has been steadily increasing since the early 1990s. At the Mayo Clinic, 91 cases/year during 2001 to 2004 were seen (a 74% increase over that in the 1980s) (139). Increasing numbers of compromised and/or elderly patients may be one reason for this increase; also, improved survival rates among cancer patients may be another reason: chemotherapy may cause damage of GI mucosal barriers, allowing anaerobic bacteria to pass through and ultimately enter the bloodstream (139).

In one study of Bacteroides bacteremia, 44% of 128 patients had a surgical procedure within 4 weeks of the bacteremia and 30% had a malignancy (169). Twenty-eight percent of the patients had a polymicrobial bacteremia, and nine of the patients were infected with two different Bacteroides species. The mortality rate for all patients was 16% if active therapy was instituted and 45% if inappropriate therapy was given. In another study, bacteremia occurred in 27% of patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections; Bacteroides isolates were the most common species recovered (84). In this study, the presence of bacteremia was the only microbiological variable known to affect mortality. In a medical center setting in Taiwan, 48% of the systemic infections could be traced to a GI source, and 27% of patients with community-acquired anaerobic bacteria had an underlying malignancy. Strains of the Bacteroides fragilis group species were the most common anaerobic isolates, occurring in 45% of the cases (124).

According to a review by Brook, the mortality rate for Bacteroides bacteremia is up to 50% and is somewhat dependent on the species recovered (B. thetaiotaomicron > B. distasonis > B. fragilis); whether this is due to differences in virulence factors or to differences in antimicrobial susceptibility is not known (44).

Septic arthritis.

Bacteroides fragilis is a rare cause of septic arthritis. Most patients with B. fragilis septic arthritis have a chronic joint disease, particularly rheumatoid arthritis, and sources of infection include lesions of the GI tract and the skin (1, 29, 76, 112, 157, 220, 309). There is one report of a case of hip septic arthritis in an alcoholic patient (157). In that paper, the authors reported that about 9% of cases of anaerobic septic arthritis are attributed to B. fragilis, but the references for these data were two decades old, and the taxonomic changes that have occurred since then would render that data misleading. A 2006 report reviewed cases of infection in prosthetic joints and did find reports of infection with anaerobes, including Clostridium difficile, Clostridium perfringens, Porphyromonas melaninogenica, and Veilonella species, but not Bacteroides species (151). However, one recent report of an improved method of culturing these infections found one isolate of B. fragilis in intraoperative specimens from 72 patients with prosthetic joint revision (a total of 155 isolates were recovered) (239).

Brain abscess and meningitis.

While not common, cases of meningitis due to B. fragilis have been reported (4, 88, 93, 163, 168, 172, 183). If these organisms are isolated, a predisposing source of infection should be sought (168). Ventriculoperitoneal shunts that perforate the gut may lead to a shunt infection with Bacteroides and ultimately to meningitis (50).

IBD.

ETBF has been implicated in IBD, but the correlation is not straightforward (12). In one study, the rate of ETBF was high in patients with or without disease. The prevalence of the enterotoxin gene was higher in luminal washings of patients with diarrhea in the control group than in patients without diarrhea, but overall no difference was seen in the prevalences of the toxin gene in patients with and IBD than in the control group. One hypothesis to explain a potential pathogenic mechanism is that colonization with ETBF leads to acute or chronic intestinal inflammation (304); also, the enterotoxin may cleave E-cadherin, an intercellular adhesion protein forming the zonula adherens of intestinal epithelial cells (303) (which limits the ability of water or larger molecules to pass between cells), thus leading to the increased permeability of intestinal epithelial cells. In polarized cell monolayers, BFT alters the apical F-actin structure, resulting in disruption of the epithelial barrier function (39), which may consequently contribute to the diarrhea1 disease associated with B. fragilis infection (28).

Gut bacteria have been implicated as environmental factors in the inflammatory process of ulcerative colitis, a chronic inflammatory mucosal disease. The pANCA (perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody) autoantibody, which is directed against neutrophil proteins, cross-reacted with a microbial antigen epitope in E. coli and Bacteroides (64). In E. coli, the epitope was located on the OmpC protein, one of the well-characterized porin proteins. In B. thetaiotaomicron and B. caccae, the epitope was found on ∼80-kDa and ∼100-kDa proteins, respectively.

Crohn's disease is a subacute or chronic inflammation of the GI tract that may include ulcers and granulomas (95). The role of the commensal bacteria in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis is currently being studied intensively (11, 269, 270). Some studies have implicated E. coli and B. vulgatus in the development of this disease. High titers of antisera to a 26-kDa antigen on the surface of B. vulgatus was found in patients with Crohn's disease (10), but the association of these bacteria with the disease process remains somewhat unclear (95). In a very recent report, two hypotheses of the nature of the bacterial role in IBD (including ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease) are discussed (270). One theory attributes an excessive immunologic response to normal microflora to a malfunction in the immune system. The second theory suggests that changes in the composition of gut microflora and/or deranged epithelial barrier function elicits pathological responses from the normal mucosal immune system. The authors conclude that IBD is characterized by an abnormal mucosal immune response but that microbial factors and epithelial cell abnormalities are implicated in this response. Paneth cells, for example, produce defensins, which are small cationic peptides with antimicrobial activity. Lack of production of these peptides may allow higher bacterial concentrations in the ileal intestinal crypt, which could ultimately contribute to inflammation. Several studies indicated that the gut flora could drive mucosal inflammation, perhaps due to a lack of immune tolerance to the antigens in this flora.

Anaerobes in Pediatric Infections

Infections with intra-abdominal origin.

Sites of Bacteroides infections in children mirror those found in adults. As in adults, Bacteroides isolates are most predominant in infections that have an intra-abdominal origin; normally present in the GI tract, these organisms may enter the peritoneal cavity due to a disturbance such as perforation, obstruction, or direct trauma. A few studies evaluating the microbiology of the peritoneal cavity and postoperative wounds in children following perforated appendix in pediatric patients found that Bacteroides species were recovered from 93% of peritoneal fluids, along with enteric gram-negative bacteria and enterococci (38). Complications following peritonitis may include subphrenic, hepatic, splenic, and retroperitoneal abscesses (39) (which may occur secondary to appendicitis), necrotizing enterocolitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, tubo-ovarian infection, surgery, or trauma (39). B. fragilis was the most common anaerobe found in postsurgical wound infections in wounds relating to the gut flora (37). As expected, wounds and other subcutaneous tissue infections in the rectal area, or that otherwise originated from the gut flora, are typically polymicrobial and often included Bacteroides species. A few studies found that ETBF was associated with diarrheal disease in young children 1 to 5 years of age (235).

Bone and joint infections in children.

Anaerobes have rarely been reported as a cause of joint and bone infections in children. If found, anaerobic infections in arthritis typically involve a single isolate; the isolates found include anaerobic gram-negative bacilli (both B. fragilis group and Fusobacterium species), Clostridium spp., and Peptostreptococcus spp. Anaerobic arthritis is generally secondary to hematogenous spread. Anaerobic osteomyelitis will usually occur due to an anaerobic infection elsewhere in the body and may involve more than one organism (36). Some of these infections may result in positive blood cultures, and the organisms recovered are similar to those from the infected sites (46). Osteomyelitis involving long bones, which may occur after trauma or fracture, may also involve Bacteroides (35). A fairly recent review by Brook comments on the reports of the recovery of anaerobic organisms from infected bones in children (36).

Bacteremia in children.

The incidence of anaerobic bacteremia in children appears to be lower than it is in adults (∼1 to 8% of blood cultures) The particular anaerobe implicated in the bacteremia depends on the portal of entry and the underlying disease, and while other anaerobes are found, Bacteroides fragilis is the isolate most often recovered (36 to 64% of anaerobic blood culture isolates) (44). These infections are more likely to be found in children with predisposing conditions (e.g., malignancies, immunodeficiencies, renal insufficiency, or polymicrobial sepsis).

Infections in newborns.

The involvement of anaerobes in infections in newborns is lower than that in older children. In newborns, anaerobes may be involved in cellulitis, aspiration pneumonia, infant botulism, conjunctivitis, and omphalitis (35). Bacteroides may be involved in cellulitis at the site of fetal monitoring (49). The fact that ETBF-associated diarrhea can be seen in children of 1 to 5 years but not in neonates suggests the possibility of maternal protection (192). In neonatal bacteremia, anaerobes are recovered in 2 to 12% of cultures, and close to half of those are Bacteroides species (47). The overall mortality noted was 26%, and mortality was highest with the B. fragilis group (34%). Inappropriate antimicrobial therapy was often a contributory factor for the high mortality (47). As mentioned above, ETBF is rarely found earlier than the age of 1 year; however, an ETBF strain was the sole organism isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid of a newborn with a complex congenital medullary-colonic fistula (4). No antibodies to the enterotoxin were found in the patient's serum.

Bacteroides as a Reservoir of Resistance Determinants

Clearly, human intestinal bacteria can have neutral or beneficial effects on human health and are, in fact, essential for the proper functioning of the digestive system. The other side of the coin is, in the words of Salyers et al., their “sinister role in human health as reservoirs for antibiotic resistance genes” (228). Thus, Bacteroides isolates, dwelling as seemingly innocuous members of the human colon, can serve as reservoirs of resistance determinants which they can pass on to much more virulent bacteria that move through the gut only periodically, even respiratory bacteria that are inhaled, swallowed, and pass through the gut in 24 to 48 h. “Viewed in this way, the human colon is the bacterial equivalent of eBay,” says Abigail Salyers, an expert on Bacteroides resistance and resistance transfer. “Instead of creating a new gene the hard way—through mutation and natural selection—you can just stop by and obtain a resistance gene that has been created by some other bacterium” (224).

This model suggests that human intestinal bacteria carry a variety of resistance genes that they can share among themselves (250). This genetic “elasticity” has permitted an unanticipated degree of transfer of resistance genes between species and suggests that multidrug resistance will continue to increase (108). The studies to support this model are retrospective in nature, comparing the DNA sequences of resistance genes found in different bacterial species of the human colon. Carriage of the tetracycline resistance gene (tetQ) in Bacteroides has increased from about 30% to more than 80%, and alleles of tetQ in different Bacteroides species were 96 to 100% identical at the DNA sequence level, which is what would be expected from horizontal gene transfer. Similarly, carriage of the erm gene rose from <2 to 23%. Furthermore, carriage of the tetQ and erm genes was also found in healthy people. If the genes found in different species are >95% identical, it is assumed that the gene was transferred horizontally from one species to the other (as opposed to two functionally similar proteins that evolved separately—in that case the DNA sequences can differ by more than 90%). Comparison of erm gene sequences found in other species that either do not normally reside in the human colon (Streptococcus pneumoniae) or reside there in low numbers (Clostridium perfringens and Enterococcus faecalis) with those in Bacteroides indicate that some transfer (direct or indirect) occurred between the species (250).

The elements containing resistance genes are remarkably stable, even in the absence of antibiotic pressure (227). One mechanism by which their stability is maintained may be the organization of genes into an integron, where the genes for antibiotic resistance are maintained in the same integron as enzymes that provide a benefit for the bacterium (e.g., the ability to colonize efficiently). Also, the ability to transfer these elements, coupled with the ability of tetracycline to induce transfer of these elements, makes it likely that bacteria exposed to low levels of tetracycline will have a tendency to transfer these elements to other bacteria that may have lost these genes (227).

Thus, aside from the danger posed by increasingly resistant B. fragilis, the possibility exists that even respiratory organisms such as Klebsiella pneumoniae (173) and Acinetobacter baumanii (60, 106, 125) may acquire resistance determinants from their temporary neighbors as they pass through the gut. Equally disturbing is the recent evidence that innocuous intestinal bacteria in cattle may be reservoirs for resistance and that mobile DNA elements (e.g., plasmids) were responsible for the rapid spread of drug resistance on farms whether or not therapeutic antibiotic use was involved (234). The likelihood of a meteoric rise in drug resistance is crystal clear; a strategy to halt or delay this potentially catastrophic development is, unfortunately, less obvious.

THE NITTY-GRITTY

Taxonomy

The genus Bacteroides has undergone major revisions in the past 15 years. The inclusion or exclusion of species within the genus Bacteroides changes frequently, and keeping up with the taxonomic revisions is a major undertaking. However, these changes are of importance both to clinicians and to clinical microbiologists, since taxonomic placement is a useful tool that can be an indicator of virulence potential or antimicrobial resistance. Familiarity with Bacteroides taxonomy can also influence the evaluation of published susceptibility assays and aid in predicting susceptibility of a clinical isolate. B. thetaiotaomicron, for example, is much more resistant to many antimicrobials than is B. fragilis, and omission of the more resistant species in a published antibiogram may give misleading results.

In 1989 to 1990, the species within Bacteroides were restricted to members of the B. fragilis group (241), and most of the clinically relevant species that were not retained in the genus Bacteroides were placed in the genus Porphyromonas (242) or Prevotella (240). Bacteroides gracilis, which is often involved in deep-seated infections (126), was moved to the genus Campylobacter and renamed Campylobacter gracilis (286). More recently, a host of other genera were described for Bacteroides species, including, among others, Dialister, Megamonas, Mitsuokella, Tannerella, Tissierella, and Alistipes (260).

Often by using culture-independent approaches such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing, a variety of new species have added to the total number of Bacteroides species (now >20). In the fall of 2005, several species were added to the genus Bacteroides, including Bacteroides goldsteinii (261), Bacteroides nordii and Bacteroides salyersai (262), Bacteroides plebeius and Bacteroides coprocola from human feces (135), and Bacteroides massiliensis isolated from the blood culture of a newborn (86). Recently, B. goldsteinii, along with Bacteroides distasonis and Bacteroides merdae, were moved to a new genus, Parabacteroides (225).

Isolation and Identification

Laboratories experienced in processing specimens for anaerobic bacteria will be familiar with the principles used in isolating and identifying Bacteroides strains, and the reader is referred to the Wadsworth-KTL Anaerobic Bacteriology Manual (127) and the Manual of Clinical Microbiology (128). A very brief summary of points to be aware of in processing the specimen is as follows: (i) collect the specimen in a manner to avoid contamination with normal flora; (ii) use an oxygen-free transport medium system and avoid drying; (iii) Bacteroides spp. grow relatively rapidly compared to most other anaerobes, and their growth on selective medium (e.g., Bacteroides bile esculin agar) is quite distinctive; and (iv) B. fragilis is resistant to kanamycin, vancomycin, and colistin and is stimulated by 20% bile (which is inhibitory for most other anaerobic organisms [except Bilophila]). Other tests to identify the species of Bacteroides isolates are listed in the Wadsworth-KTL Anaerobic Bacteriology Manual (127).

Several PCR schemes to identify Bacteroides species to the genus and/or species level have been developed. One report developed group-specific primers to the β-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase gene leuB and found that this was a useful tool for rapid diagnosis of Bacteroides infections (159). Our laboratory developed a multiplex PCR system with group- and species-specific primers to rapidly identify species of the B. fragilis group (146). Using the latter technique, 10 species of the B. fragilis group could be identified.

Physiology

Bacteroides species are a pleomorphic group of non-spore-forming gram-negative anaerobic bacteria. The cell envelope of B. fragilis is a particularly complex structure consisting of multiple layers, with subunits of one layer protruding through another. Descriptions of these layers come both from structural and functional studies, but results of these studies have not necessarily provided consistent descriptions either of the makeup, function, or relationship to each other of these layers. We have recently published a detailed review of the cell surface structures of Bacteroides (199), and they will be described briefly here. The B. fragilis capsule has already been discussed at length in a previous section (“The bacterial capsule”).

Cell Surface Structures

Pili, fimbriae, and adhesins.

The terms pili, fimbriae, and adhesins are not very distinctly defined. Although adhesins (for example, pili and fimbriae used in adhesion) are often protein, the term is not restricted to protein adhesins, and other structures may be implicated. B. fragilis may possess peritrichous fimbriae (178). These fimbriae have been implicated in adhesion; in one study, trypsin treatment of clinical isolates of B. fragilis inhibited both hemagglutination and adhesion to a human intestinal cell line, suggesting that the responsible adhesins were proteins (87). In various studies, pili have also been implicated in hemagglutination and adhesion (51, 193). Other studies, however, implicated the polysaccharide capsule rather than the protein appendages (177). Recent functional genomic studies classifying databases of specific molecules note that members of the Bacteroides secrete large numbers of lipoproteins with an N-terminal beta-propeller domain, which may form a specialized adhesion module (7, 20). Discrepancies among the various studies may be due to differences in the cell lines used, differences in the pilus type studied, or differences in the capsule characteristics of the particular strains.

Lectin-like adhesins have been demonstrated in B. fragilis (218); correspondingly, sialic acid and other sugars, as well as macromolecules rich in sialic acid, have been identified as the receptors for these adhesins (77). In some cases, the adhesin will bind to the receptor residue only after neuraminidase treatment (110). Indeed, many B. fragilis strains have neuraminidase activity, and Guzman et al. (110) suggest that the bacterial removal of the terminal sialic acid may serve as a mechanism to expose the adhesion sites in a two-step adhesion process. Others found that adherence to WiDr cells and hemagglutination were not affected by neuraminidase activity (167). Hemagglutination appears to be caused by more than one adhesin, at least one of which is a carbohydrate (probably the capsule), with the pili assuming this role in noncapsulated strains (15). Recently, a surface glycoprotein of B. fragilis was implicated in binding to one of the laminin proteins that make part of the extracellular matrix that underlies epithelial, endothelial, and surrounding connective tissue cells (74).

Fibrils.

Fibrils are a class of bacterial appendage consisting of polysaccharide and associated proteins and are much finer and often much shorter than pili. In fact, they may be impossible to distinguish from long LPS side chains in transmission electron microscopy, since the lengths quoted for these structures overlap. However, peritrichous fibrils were reported in only one out of 19 B. fragilis strains studied (178), and these were distinguished from the capsule, pili, and ruthenium red staining layer (probably composed mostly of LPS side chains). Again, not all cells of a given population exhibited these fibrils. Little is known about the function of these fibrils, and their role in adhesion and biofilm formation remains to be determined.

LPS.

The LPS side chains project from the lipid moiety that is anchored in the outer membrane, forming a visible fringe in transmission electron microscopy (the exact nature of this layer remains to be determined, but most authors assume that the fringe overlying the outer membrane comprises the LPS side chains.) In our own recent studies, we noted significant variation in the height and density of the LPS fringe between individual colonies within the same cell population grown under the same conditions (199).

Outer membrane proteins.

Several membrane proteins have so far been characterized in B. fragilis. We demonstrated that OmpA was the major outer membrane protein in B. fragilis (302), and our studies further suggest that B. fragilis OmpA1 is important in maintaining cell structure (unpublished data). We identified four distinct genes that encode OmpA homologs and found that all four ompA genes are transcribed in B. fragilis. In other bacteria OmpA has been shown to be associated with virulence (292), but we have not yet studied this in B. fragilis.