Abstract

Background and purpose:

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is activated by metformin, phenformin, and the AMP mimetic, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside (AICAR). We have completed an extensive study of the pharmacological effects of these drugs on AMPK activation, adenine nucleotide concentration, transepithelial amiloride-sensitive (Iamiloride) and ouabain-sensitive basolateral (Iouabain) short circuit current in H441 lung epithelial cells.

Experimental approach:

H441 cells were grown on permeable filters at air interface. Iamiloride, Iouabain and transepithelial resistance were measured in Ussing chambers. AMPK activity was measured as the amount of radiolabelled phosphate transferred to the SAMS peptide. Adenine nucleotide concentration was analysed by reverse phase HPLC and NAD(P)H autofluorescence was measured using confocal microscopy.

Key results:

Phenformin, AICAR and metformin increased AMPK (α1) activity and decreased Iamiloride. The AMPK inhibitor Compound C prevented the action of metformin and AICAR but not phenformin. Phenformin and AICAR decreased Iouabain across H441 monolayers and decreased monolayer resistance. The decrease in Iamiloride was closely related to Iouabain with phenformin, but not in AICAR treated monolayers. Metformin and phenformin increased the cellular AMP:ATP ratio but only phenformin and AICAR decreased cellular ATP.

Conclusions and implications:

Activation of α1-AMPK is associated with inhibition of apical amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels (ENaC), which has important implications for the clinical use of metformin. Additional pharmacological effects evoked by AICAR and phenformin on Iouabain, with potential secondary effects on apical Na+ conductance, ENaC activity and monolayer resistance, have important consequences for their use as pharmacological activators of AMPK in cell systems where Na+K+ATPase is an important component.

Keywords: AMPK, Na+ transport, ENaC, Na+K+ATPase, lung, epithelium, phenformin, metformin, AICAR

Introduction

Recently, there has been much interest in the action of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in cellular signalling processes, because of its role as a cellular metabolic sensor and its ability to elicit a wide range of effects in diverse tissues (Hardie, 2003; Kemp et al., 2003). This kinase is activated by an increase in the intracellular ratio of AMP:ATP, making it very sensitive to changes in cellular metabolic status. Once activated, AMPK downregulates pathways that consume ATP and upregulates those that generate ATP, in order to maintain cellular energy stores (Hardie, 2003, 2004; Hardie and Sakamoto, 2006).

There are several pharmacological agents that have been used extensively to activate AMPK in intact cells. These include the biguanides metformin, (Zhou et al., 2001), its more potent analogue phenformin (Sakamoto et al., 2004) and the nucleoside 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside (AICAR) (Corton et al., 1995). Phenformin is thought to activate AMPK by inhibiting Complex I of the mitochondrial respiratory chain (El-Mir et al., 2000; Owen et al., 2000), resulting in changes in intracellular levels of AMP and/or the AMP:ATP ratio (Hawley et al., 2005). Phenformin was used in the clinical treatment of type II diabetes, but it has been withdrawn from clinical use in the UK, due the high incidence of lactic acidosis. Metformin, which has replaced the use of phenformin, also inhibits Complex I (El-Mir et al., 2000; Owen et al., 2000), but changes in intracellular AMP:ATP ratios have been difficult to determine with this drug (Hawley et al., 2002; Fryer et al., 2002b). In contrast to the biguanides, AICAR, currently being considered as a clinical alternative, is taken into the cell via adenosine transporters (Gadalla et al., 2004) and then converted by adenosine kinase to the monophosphorylated nucleotide, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranosyl (AICAR) 5′ monophosphate, or ZMP, which binds to and activates AMPK in a manner similar to AMP. While these drugs activate AMPK, they may also have other cellular effects. Therefore, the AMPK inhibitor Compound C has been widely used to attribute downstream effects specifically to the activation of this kinase (Zhou et al., 2001; Fryer et al., 2002b).

Transport of Na+ across the lung epithelium from the lumen to interstitium is an essential regulator of airway fluid volume. Na+ crosses the epithelial cell apical membrane, predominantly through the amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel (ENaC), and is extruded via the basolateral Na+K+ATPase pump in an energy consuming process. Misregulation of this pathway can lead to accumulation or dehydration of fluid in the airway and contribute to the pathogenesis of airway disease (Boucher et al., 1988; Kerem et al., 1999). Changes in cell metabolism and oxygen tension have been observed to decrease Na+ transport processes across bronchiolar epithelium and rat alveolar cell monolayers (Stutts et al., 1988; Ramminger et al., 2000; Mairbaeurl et al., 2002), implying that AMPK may have a role in the signalling pathways mediating these events.

We have shown that pharmacological activation of AMPK with phenformin and AICAR, for 1 h decreased transepithelial Na+ transport, measured as short circuit current (Isc), in H441 airway epithelial cells (Woollhead et al., 2005). These findings provided support for a cellular signalling pathway that links decreased metabolic status and the consequent reduction in ion transport processes to activation of AMPK. Consistent with work in Xenopus oocytes, we found that this effect was the result of decreased apical Na+ entry through ENaC (Carattino et al., 2005). However, we also showed that there was a significant pharmacological effect of these agents on Na+K+ATPase function, which can also regulate transepithelial transport (Woollhead et al., 2005). Moreover, our findings raised the possibility that the widely prescribed drug metformin, also an activator of AMPK, could additionally inhibit ion transport processes in the lung.

To investigate the effect of metformin, phenformin and AICAR in more detail, we have carried out the first extensive study of the pharmacological effects of these drugs in H441 lung epithelial cells. The data presented here indicate that although all drugs activated AMPK, they have different effects on Na+ transport processes. Our data indicate that changes in cellular nucleotides, independently of activation of AMPK, could have additional effects on Na+K+ATPase function and apical Na+ entry, which contribute to the difference in potency observed with these drugs. These findings have wide implications for the use of pharmacological activators of AMPK in other cell systems.

Methods

Test system used

The human H441 lung epithelial cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA, USA) and maintained in Rosewell Park Memorial Institute-1640 medium supplemented with foetal bovine serum (10%) (Invitrogen, Paisley, Scotland, UK), L-glutamine (2 mM), sodium pyruvate (1 mM), insulin (5 μg ml−1), transferrin (5 μg ml−1), sodium selenite (7 ng ml−1) and antibiotics (penicillin, 100 U ml−1/streptomycin, 100 μg ml−1). Cells were seeded in 25 cm2 flasks and incubated in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37°C. For functional studies, H441 cells were seeded on Snapwell clear membranes (Costar, VWR, Lutterworth, Leicestershire, UK) and cultured overnight. The following day (or when fully confluent) the serum in the medium was replaced with 4% charcoal-stripped serum, with the additional supplement of triiodothyronine (T3) (10 nM) and dexamethasone (200 nM). The monolayers were cultured for 6–7 days in this medium at air interface to induce polarization.

Measurements made

Identification of subunits and measurement of AMPK activity PCR. RNA was extracted from H441 cells using Trizol (Sigma, Poole, Dorset, UK) with a post-extraction treatment with 1 U amplification grade DNase1 for 15 min at room temperature (Invitrogen, UK). A 2 μg weight of RNA was reverse transcribed using avian myeloma virus reverse transcriptase, as previously described (Woollhead et al., 2005). Reaction mixtures contained 50 ng of cDNA, 10 mM dNTPs, 0.2 μl platinum taq polymerase (5 U μl−1), 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 0.8 μM of primer. α1 AMPK primers (5′–3′; forward, cggcaaagtgaaggttggcaaa and reverse caaatagctctcctcctgagac) gave an expected product size of 227 bp pairs using cycle conditions of 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min for 35 cycles. α2 AMPK primers, (5′–3′; forward ttgggagggtgccacaaagaag and reverse, acgggttgaagagatggaagccag) gave an expected product size of 314 bp. Cycling conditions were the same as above, except that the annealing temperature was raised to 61.1°C. Amplification of β-actin (Clontech, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France) was used as a reaction control. Amplified products were resolved on 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide and visualized with UV light.

Western blotting. Lysates prepared from H441 cells and rat liver tissue were heated to 94°C for 5 min in the presence of 100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 2% w/v sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), to denature the proteins. A 30 μg weight of protein was subjected to electrophoresis on SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Fractionated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes by electroblotting and immunostained with either anti-α1 or -α2 AMPK antiserum, using standard techniques.

AMPK activity. H441 cell protein (100 μg) was incubated for 2 h at 4°C with 10 μg of AMPK α1 or α2 antibodies, which had been prebound to 10 μl of protein G–Sepharose. The immunoprecipitate was then washed 5 × 1 ml of ice-cold immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer ((in mM): Tris, 50 pH 7.4; NaCl, 1000; NaF, 50; Na+ pyrophosphate, 5; EDTA, 1; EGTA, 1; DTT, 1; benzamidine, 0.1; phenylmethylsulphonylfluoride, 0.1; 5 μg ml−1 soybean trypsin inhibitor and 1% v/v Triton X-100), and then with 5 × 1 ml of ice-cold IP buffer (as described above, except containing 150 mM NaCl) then with 1 × 1 ml with assay buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 1 mM DTT, 0.02% v/v Brij-35). Immunopurified AMPK activity was measured as the amount of radiolabelled phosphate transferred to the SAMS peptide, derived from the sequence surrounding the major AMPK site on acetyl-CoA carboxylase, as previously described (Hardie et al., 2000; Woollhead et al., 2005).

Measurement of Isc. Monolayers were mounted in Ussing chambers, where the drug was circulated in a physiological salt solution (in mM): NaCl, 117; NaHCO3, 25; KCl, 4.7; MgSO4, 1.2; KH2PO4, 1.2; CaCl2, 2.5; D-glucose, 11 (equilibrated with 5% CO2 to pH 7.3–7.4). The solution was maintained at 37°C, bubbled with 21% O2+5% CO2 premixed gas and continuously circulated throughout the course of the experiment. Control and drug-treated monolayers were analysed in parallel. The monolayers were first maintained under open-circuit conditions, while transepithelial potential difference (Vt) and resistance (Rt) were monitored and observed to reach a stable level. The cells were then short circuited by clamping Vt at 0 mV using a DVC-4000 voltage/current clamp and the current required to maintain this condition (Isc), was measured and recorded using a PowerLab computer interface. Every 30 s, throughout each experiment, the preparations were returned to open-circuit conditions for 3 s, so that the spontaneous Vt could be measured and Rt could be calculated.

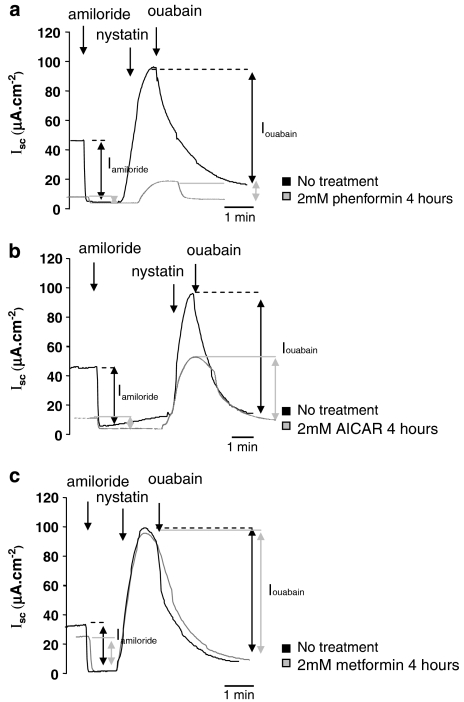

Amiloride-sensitive transepithelial Na+ Isc (Iamiloride) was measured by adding 10 μM amiloride to the solution perfusing the apical side of the monolayer. Basolateral ouabain-sensitive Isc (Iouabain) was measured by permeabilizing the apical membrane with 75 μM nystatin. The unrestricted access of ions to the intracellular compartment then causes basolateral Isc to rise. Once peak levels were achieved, 1 mM ouabain was added to the basolateral compartment to inhibit Na+K+ATPase activity. The ouabain-sensitive component of Isc (Iouabain) was calculated as the difference in Isc before and after application of ouabain, and gives a measure of maximal net transport capacity via Na+K+ATPase (number of pumps × turnover) in the ionic conditions used (Figures 4a-c).

Measurement of intracellular adenine nucleotide concentration. Adenine nucleotides—ATP, ADP, AMP and TAN (total adenine nucleotides)—were determined in untreated monolayers or those treated with phenformin, AICAR or metformin for 4 h. Cells were washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then cold (0.4 M) perchloric acid was added to extract the nucleotides. Cell extracts were neutralized with 3 M K3PO4 and were analysed with high-performance liquid chromatography, according to the reverse-phase procedures described previously in detail (Smolenski et al., 1990; Kalsi et al., 1999). The equipment used was the Hewlett-Packard 1100 series linked to a diode array detector. Protein content was determined in the perchlorate precipitate by using the Bradford assay.

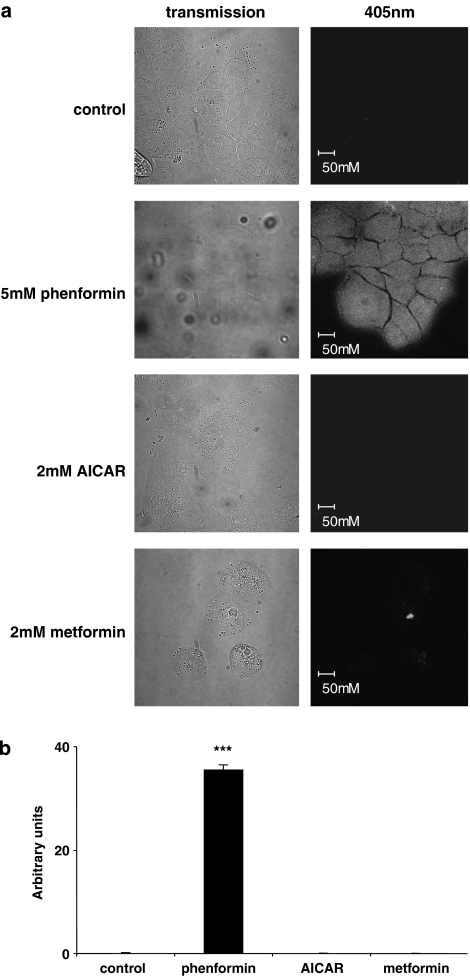

Measurement of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate) (NAD(P)H) autofluorescence. Cells seeded on coverslips were grown to subconfluence prior to treatment for 1–4 h with phenformin, AICAR or metformin and mounted in a perfusion chamber containing phenol red free culture medium (Invitrogen, UK) at room temperature. Patches of cells were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 510 laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with a blue diode laser and excitation at 405 nm. Emitted fluorescence was captured using LSM 510 software (release 3.2, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) via a Zeiss Apochromat × 63 oil-immersion objective (numerical aperture 1.4). There was no discernable effect on cell confluence or viability from treatment with the drugs.

Experimental design

For short circuit current measurement, sets of snapwells (up to 12, plated at the same time and cultured under similar conditions for a similar length of time) supporting resistive monolayers of H441 cells (⩾300 Ω cm2) were treated in culture with 5 mM phenformin, 2 mM AICAR or 2 mM metformin for 1–48 h. The concentrations of phenformin and AICAR have been shown to elicit a similar elevation of AMPK activity in H441 cells (Woollhead et al., 2005), and 2 mM metformin has been shown to similarly elevate AMPK activity in other cell systems (Fryer et al., 2002a). We also used 0.5 mM phenformin, which we have previously shown to elevate AMPK activity twofold after a 1 h treatment (Woollhead et al., 2005). Cells were pretreated with Compound C (80 μM) (Calbiochem, Nottingham, UK) for 40 min before treatment with phenformin, AICAR or metformin as above. All agents were suspended in culture medium or as a 1000 × concentrated stock in dimethyl sulphoxide. Untreated cells were overlaid with culture medium alone or treated with vehicle control. At the end of each functional experiment, the cell monolayers were rinsed in ice-cold PBS and harvested into lysis buffer for analysis of AMPK activity (in mM): Tris, 50 (pH 7.4); NaCl, 150; NaF, 50; Na pyrophosphate, 5; EDTA, 1; EGTA, 1; DTT, 1; 1% v/v Triton X-100 and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, UK). H441 cell suspensions were then stored at −80°C until required. Cell viability in untreated monolayers and those treated with metformin, phenformin and AICAR for 1, 4, 8 and 24 h was assessed by Trypan Blue exclusion. Adherent (and any non-adherent cells) present in the transwell chamber were released from the filter by incubation with trypsin/EDTA solution (Sigma, UK) (200 μl) for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were resuspended in full culture medium and aliquots were mixed with an equal volume of Trypan Blue (Sigma, UK). White (live) and blue (blue) cells were counted (cells ml−1) using fast read counting chambers (ISL Ltd., Paignton, Devon, UK) and the live/dead cell ratio (indicative of cell viability) was calculated.

Data analysis and statistical procedures

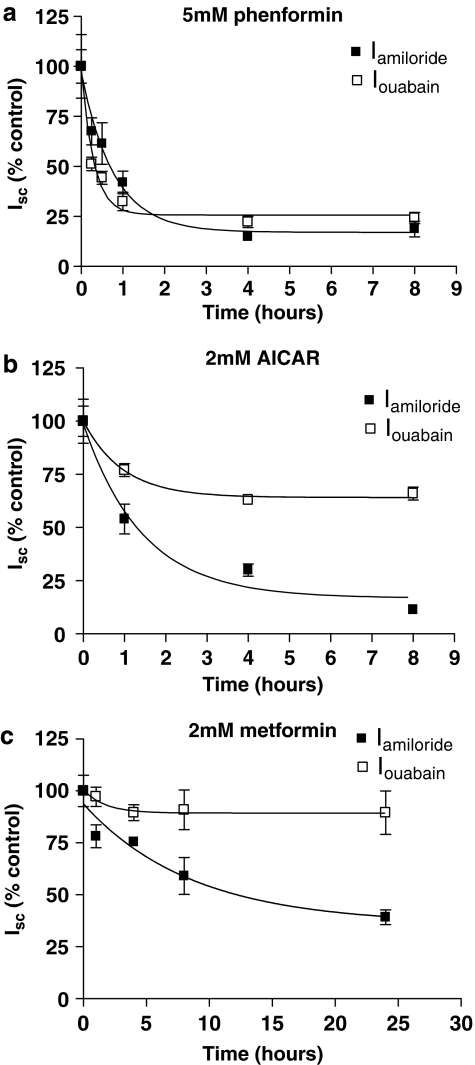

Since the resistance and basal levels of ion transport across the monolayers varied between batches of cells, control experiments and treatments were carried out on monolayers plated on the same day. Results are compiled from at least three independent sets of cells. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. in Table 1. In Figures 3, 4 and 5, Isc is presented graphically as percentage of control Isc to facilitate comparison between the pharmacological agents and effects on transepithelial amiloride-sensitive short circuit current (Iamiloride) and Iouabain.

Table 1.

Effects of phenformin, AICAR and metformin on H441 cellular nucleotide abundance

| ATP | ADP | AMP | TAN | AMP:ATP | ADP:ATP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 26.3±1.1 | 1.39±0.17 | 0.23±0.04 | 27.96±1.3 | 0.009±0.002 | 0.05±0.004 |

| Phenformin | 21.9±0.7* | 3.08±0.14* | 1.08±0.0.24** | 25.58±0.3* | 0.049±0.025* | 0.14±0.006*** |

| Metformin | 25.3±1.8 | 1.96±0.12* | 0.31±0.02* | 27.57±1.6 | 0.012±0.001* | 0.08±0.001** |

| AICAR | 18.7±2.3* | 0.88±0.11* | 0.17±0.02 | 19.7±2.4* | 0.009±0.002 | 0.05±0.003 |

Abbreviations: AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside;

Amounts of cellular adenine nucleotides (ATP, ADP, AMP) and total adenine nucleotides (TAN) are shown in nmol mg−1 cellular protein. Results are shown as mean±s.e.m.

significantly different from control, P<0.05

significantly different from control, P<0.01

significantly different from control, P<0.001 for n=3 independent experiments apart from phenformin/AMP, n=6.

Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post hoc Gabriel's pairwise test (Kendall and Stuart, 1968) or Student's t-tests, where applicable; P-values of < 0.05 were considered significant. Results are presented as mean±s.e.m.

Drugs

All drugs and reagents were purchased from Sigma (Poole, UK), unless otherwise stated.

Results

AMPK isoforms in H441 cells

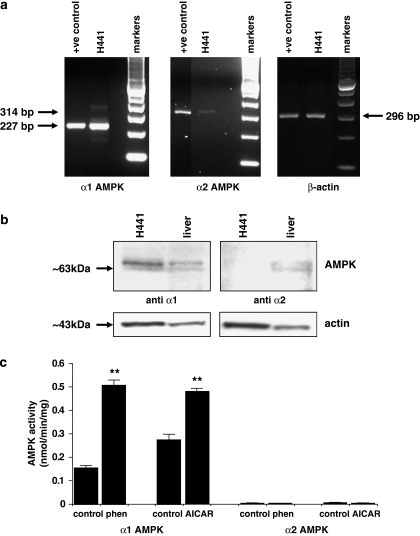

PCR analysis using primers to amplify sequences derived from α1 and α2 catalytic subunits of AMPK showed that mRNA products encoding both isoforms were present in H441 cells. However, amplified products from α1 AMPK were more abundant than those of α2 from similar starting quantities of cDNA. This was not due to inefficiency of the α2 primers, because amplification of both isoforms was similar from RNA extracted from our positive control (human ovarian tissue). The α1 subunit was also more readily detectable than the α2 subunit, in H441 cells, by western blotting (Figures 1a and b). Treatment of H441 cells with either 5 mM phenformin or 2 mM AICAR for 1 h induced a significant increase in AMPK activity of the α1 isoform. There was almost undetectable activity associated with the α2 isoform of AMPK (0.004±0.001 nmol min−1 mg−1, n=6), and this was not significantly changed by treatment with either phenformin or AICAR (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Expression and activity of AMPK α1 and α2 in H441 cells. (a) Reverse transcriptase PCR of 50 ng mRNA extracted from H441 cells (H441) and ovarian tissue (+control) using primers to amplify α1-AMPK (227 bp) or α2-AMPK (314 bp) or β-actin (296 bp). (b) Representative western blot of 100 μg protein extracted from H441 cells (H441) or rat liver tissue (liver) immunostained with anti α1 or anti α2 AMPK (both ∼63 kDa). Blots were reprobed with anti-β-actin to control for protein loading. (c) Activity of immunopurified AMPK α1 and α2 from H441 cells that were untreated (control) or treated with 5 mM phenformin (phen) or 2 mM AICAR (AICAR). **P<0.01 significantly different from control; mean±s.e.m., n=3. AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase.

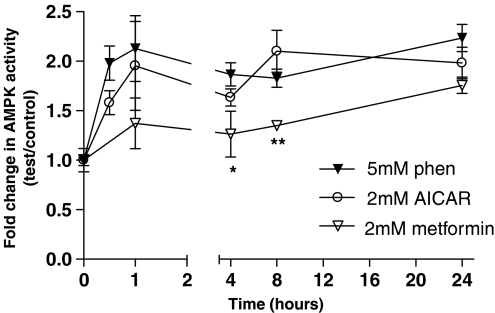

Time course of effect of phenformin, AICAR and metformin on AMPK activity

Treatment of H441 cells with 5 mM phenformin, 2 mM AICAR and 2 mM metformin significantly increased AMPK activity over time (one-way ANOVA, F5,12=5.45, P=0.0076; F5,12=9.34, P=0.0008 and F4,10=49.83, P=0.0001). Phenformin and AICAR increased AMPK activity approximately × twofold after 0.5 h, and elevated activity was sustained at 4, 8 and 24 h (n=3). There was no significant difference between phenformin- and AICAR-induced AMPK activity at any time point, up to 24 h. The metformin-induced increase in AMPK activity was significantly less than that induced by phenformin or AICAR, at 4 and 8 h (P<0.01 and P<0.05, n=3, respectively), but reached similar levels by 24 h (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of phenformin, AICAR and metformin on AMPK activity in H441 cells. H441 cells were treated in culture for 30 min to 24 h with 5 mM phenformin, 2 mM AICAR or 2 mM metformin. AMPK activity was measured as the rate of phosphorylation of the SAMS peptide (nmol min−1 mg−1) and is expressed as the change in AMPK activity of treated cells compared to control. Results are shown as means±s.e.m. (n=3). Data were analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by a pairwise Gabriel's test. *P<0.05; **P<0.01, significantly different from corresponding values after treatment with phenformin or AICAR. AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; ANOVA, analysis of variance.

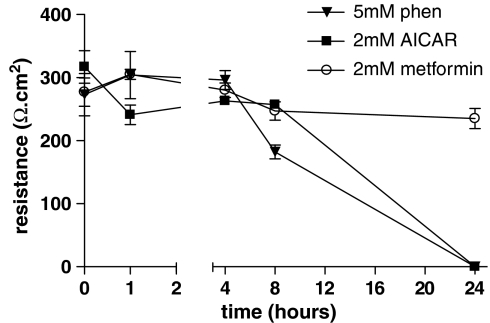

Effect of phenformin, AICAR and metformin on transepithelial resistance

To further investigate the differences in pharmacological effect of these drugs, we investigated their effect on transepithelial resistance (Rt) of H441 monolayers used in this study. This was lower at ∼300 Ω cm2 than we have previously published, and we have found this to be a consequence of passage number. However, spontaneous Isc and the component of current that was amiloride sensitive remained similar at 34±2 μA cm−2 and 85±5%, respectively. Compared to untreated monolayers, there was no significant change in Rt of metformin-treated monolayers at any of the time points studied. However, we did observe a decrease in resistance in monolayers treated with 5 mM phenformin after 8 h (P<0.01, n=4) (Figure 3). We were unable to measure a significant Rt across monolayers 24 h after treatment with 5 mM phenformin and 2 mM AICAR (Figure 3). Compared to controls, these snapwell membranes were flooded with medium on their apical surface.

Figure 3.

Effect of phenformin, AICAR and metformin on transepithelial resistance of H441 monolayers. Monolayers were treated with 5 mM phenformin, 2 mM AICAR or 2 mM metformin for 1, 4, 8, 24 and 48 h. Transepithelial resistance (Rt) was expressed in Ωcm2. Data are shown as mean±s.e.m., for the number of experiments given in Table 1. Rt could not be measured at 24 or 48 h after 5 mM phenformin or 2 mM AICAR treatment, and are assigned a value of zero. AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside.

To exclude the possibility that effects on Rt were the result of a drop in cell viability, we used Trypan Blue exclusion to assess the viability of cells contained within the transwell. We found that there was neither a significant elevation in the number of dead cells nor a decrease in the ratio of live/dead cells, which would indicate a decrease in cell viability of monolayers treated for 1, 4 and 8 h with metformin, phenformin or AICAR, compared to controls (n=3 for each time and treatment). We did however, find that there was a significant increase in the number of dead cells (P<0.05, n=3 respectively) and a decrease in the live/dead cell ratio of phenformin- and metformin-treated mononolayers after 24 h; live/dead cell ratio (control) 8±1 to metformin (4±0.5, P<0.05, n=3) and phenformin (2±0.2, P<0.01, n=3). There was a similar trend in monolayers treated with AICAR for 24 h, but we could not attribute significance to these effects.

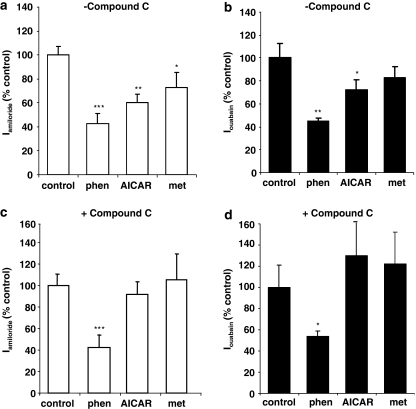

Effect of Compound C on phenformin, AICAR and metformin inhibition of Iamiloride and Iouabain

Treatment of monolayers with phenformin or AICAR for 1 h significantly inhibited transepithelial Iamiloride (Figure 4a). Metformin did not significantly inhibit Iamiloride after 1 h, but did inhibit Iamiloride after 4 h (Figure 4a). Therefore, these treatment times were used in subsequent experiments. Phenformin and AICAR also inhibited Iouabain, but metformin after 4 h had no significant effect on Iouabain (Figure 4b). Pretreatment of monolayers with the AMPK inhibitor, Compound C, did not prevent the inhibitory effect of phenformin on Iamiloride or Iouabain, but did prevent the inhibitory effect of AICAR and metformin on Iamiloride, and the effect of AICAR on Ioubain (Figures 4c and d).

Figure 4.

Effect of Compound C on phenformin or AICAR inhibition of Iamiloride and Iouabain. Monolayers were preincubated with 80 μM Compound C (+Compound C, c and d) or vehicle (−Compound C, a and b) for 40 min, before treatment with 5 mM phenformin (phenformin), 2 mM AICAR (AICAR) for 1 h or 2 mM metformin for 4 h (metformin). Iamiloride (a and c) and Iouabain (b and d) were calculated as the change in Isc after apical application of 10 μM amiloride and basolateral application of 100 mM ouabain after apical permeabilization. Data are plotted as percent control and shown as mean±s.e.m. * Significantly different from control, P<0.05, n=5; ** significantly different from control, P<0.01, n=5; *** significantly different from control, P<0.001, n=5. AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside; Iamiloride, amiloride-sensitive short circuit current; Iouabainouabain-sensitive short circuit current.

Time course of effect of phenformin, AICAR or metformin on amiloride-sensitive transepithelial Na+ transport (Iamiloride)

All the pharmacological agents significantly decreased transepithelial Iamiloride but with differing potency order of phenformin>AICAR>metformin. A typical example of an Isc trace showing Iamiloride for one time point (4 h post-drug treatment) is given in Figure 5. The complete time course is summarized in Figure 6. Phenformin (5 mM) induced a significant decrease in amiloride-sensitive transepithelial Isc (Iamiloride) over a time course of 8 h (one-way ANOVA, F5,16=9.23, P=0.0003). A decrease in Iamiloride from 37.9±4.5 to 24.2±1.0 μA cm−2, P=0.05, n=4 was observed at 15 min. Such a rapid decrease in Iamiloride was not seen with 2 mM AICAR or 2 mM metformin. Iamiloride decreased to minimal levels (∼17% of control levels) at 4–8 h. Further changes in Iamiloride could not be determined after 8 h, because of loss of resistance of the monolayer (see above) Inhibition of Iamiloride by 5 mM phenformin followed an exponential decay curve (r2=0.88) and the time required to reduce Iamiloride to half-maximal values was 31 min (Figures 5a and 6a). Interestingly, a 10-fold lower concentration of phenformin (0.5 mM) also induced a significant exponential reduction in Iamiloride over time (one-way ANOVA, F5,12=8.21, P=0.0014) (r2=0.97) (data not shown). AICAR inhibition of Iamiloride was slower than that observed with phenformin, half-maximal values were achieved after 60 min and minimal plateau levels were 13 % of control, (one-way ANOVA, F3,14=6.99, P=0.0042) (r2=0.97) (Figures 5b and 6b). Metformin also induced a significant change in Iamiloride over time (one-way ANOVA, F4,16=6.15, P=0.003), but it had the slowest effect of all the pharmacological drugs tested. Compared to control, an apparent reduction in Iamiloride was observed 1 h post-treatment, but this did not reach statistical significance until 4 h (P<0.06 and P<0.01, respectively, n=4). Half-maximal reduction of Iamiloride was not achieved until 358 min (∼6 h) post-treatment. In addition, Iamiloride remained higher at every corresponding time point compared to all other treatments (Figures 5c and 6c).

Figure 5.

Effect of phenformin, AICAR and metformin on amiloride-sensitive transepithelial (Iamiloride) and basolateral ouabain-sensitive (Iouabain) short circuit current. Representative Isc traces from H441 monolayers before treatment (control; black lines) and after treatment with 5 mM phenformin (a), 2 mM AICAR (b) or 2 mM metformin (c), all for 4 h (grey lines). Iamiloride was calculated as the change in Isc after apical application of 10 μM amiloride. Iouabain was measured by apical permeabilization of monolayers with 75 μM nystatin followed by basolateral blockade with 1 mM ouabain. AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside; Iamiloride, amiloride-sensitive short circuit current; Iouabain, ouabain-sensitive short circuit current; Isc, short circuit current.

Figure 6.

Time course of effect of phenformin, AICAR and metformin on amiloride-sensitive transepithelial (Iamiloride) and basolateral ouabain-sensitive (Iouabain) short circuit current. Monolayers were treated with 5 mM phenformin (a), 2 mM AICAR (b), or 2 mM metformin (c) for 1, 4, 8, 24 and 48 h. Effects on Iamiloride are shown as percent of Iamiloride before treatment (% of control), to allow comparison between the drugs. Data are shown as mean±s.e.m. (n=4, except AICAR 1 h when n=5). One-phase exponential decay curves were fitted to the data using GraphPad Prism4. Best-fit r2 values to the data were 0.88 (phenformin), 0.97 (AICAR) and 0.83 (metformin). (b) Effects on Iouabain are shown as percent of Iouabain before treatment (% control), to allow comparison between the drugs. Data are shown as mean±s.e.m. (n=4, except AICAR 1 h when n=5). One-phase exponential decay curves were fitted to the data as above for 5 mM phenformin and AICAR and metformin, with r2 values of 0.85, 0.65 and 0.1, respectively. AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside; Iamiloride, amiloride-sensitive short circuit current; Iouabain, ouabain-sensitive short circuit current; Isc, short circuit current.

Time course of effect of phenformin, AICAR and metformin on ouabain-sensitive basolateral Isc (Iouabain)

A typical example of an Isc trace showing Iouabain for one time point (4 h post-drug treatment) is given in Figure 5. The complete time course is summarized in Figure 6. Phenformin (5 mM) induced a significant decrease in ouabain-sensitive basolateral Isc (Iouabain), which could be attributed to net Na+K+ATPase transport capacity, over a time course of 8 h (one-way ANOVA, F5,16=4.89, P=0.007). A significant decrease in Iouabain from 59.2±12.6 to 30.4±2.6 μA cm−2, P<0.05, n=4 was observed at 15 min. This was not observed with 2 mM AICAR or 2 mM metformin. Iouabain reached minimal levels at 4–8 h. Inhibition of Iouabain followed an exponential decay curve (r2=0.85) and the time required for 5 mM phenformin to reduce Iouabain by half was 12 min, more rapid than that observed to reduce Iamiloride. Minimum Iouabain plateau levels were 26% of control levels (Figures 5a and 6a). A concentration of 2 mM of AICAR significantly decreased Iouabain at 1 and 4 h, compared to control (P<0.05, n=5 and n=4, respectively). An exponential curve fitted to the experimental data (r2=0.65) indicated that 50% maximal values occurred at 40 min. Minimal Iouabain levels were achieved by 4 h, but were only reduced to 66% of control levels (Table 1; Figures 5b and 6b). There was an apparent decline in Iouabain after metformin treatment. Fitting a similar exponential curve to this data indicated that metformin reduced pump activity to 89% of control levels, with 50% maximal values occurring at 70 min (r2=0.1). However, we were unable to attribute significance to the changes in these experiments (one-way ANOVA, F4,16=0.94, P=0.5) (Figures 5c and 6c).

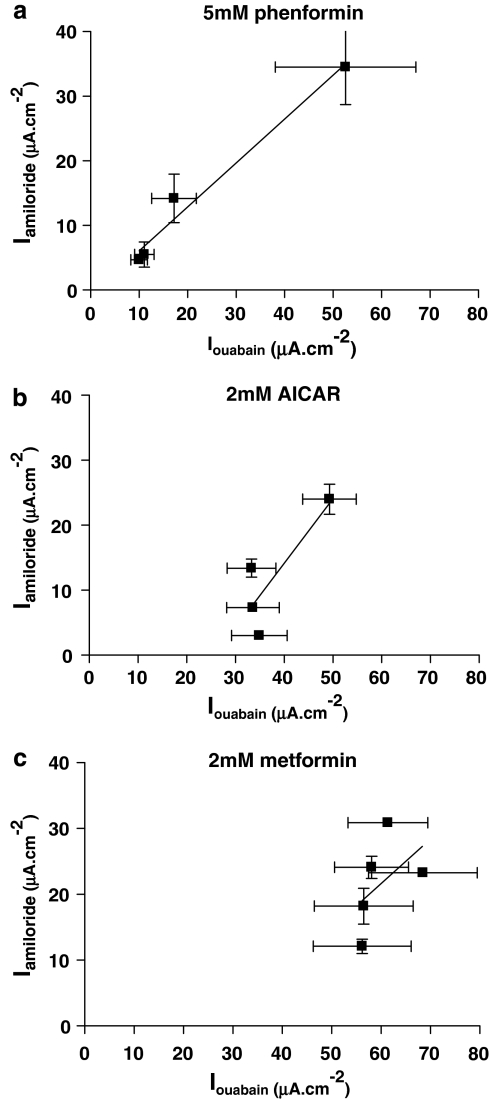

Relationship between Iamiloride and Iouabain

The relationship between Iamiloride and Iouabain was different between the pharmacological treatments. Iouabain reflects the basolateral transport capacity of Na+K+ATPase, which is critical for the generation and maintenance of the intracellular gradient for Na+ movement into the cell via the amiloride-sensitive channel ENaC. Thus, changes in Iouabain can directly influence Iamiloride. Phenformin induced a similar rapid exponential decrease in both Iamiloride and Iouabain (Figure 6a), indicating that inhibition of Na+K+ATPase transport capacity could mediate the decrease in Iamiloride. AICAR also induced a decrease in Iamiloride, but the inhibitory effect on Iouabain was much less than that on Iamiloride (see above) (Figure 6b). Furthermore, we could not attribute a significant effect of metformin on Iouabain, yet it significantly reduced Iamiloride (Figure 6c). Plotting values obtained for Iamiloride against Iouabain from the 0, 1, 4 and 8 h time points (phenformin and AICAR) and the 0, 1, 4, 8 and 24 h points (metformin) obtained in the time course study showed that there was a significant linear relationship between the two parameters only when monolayers were treated with phenformin (r2=0.97, slope=0.68±0.08, P=0.01, n=4) (Figure 7a). These data indicate that the inhibition of Iamiloride is closely related to the inhibition of Iouabain in cells treated with phenformin, but not in cells treated with AICAR and metformin (Figures 7b and c).

Figure 7.

Relationship between Iamiloride and Iouabain in cell treated with phenformin, AICAR and metformin. Values obtained for Iamiloride are plotted against Iouabain from cells treated with 5 mM phenformin (a), 2 mM AICAR (b) or 2 mM metformin (c). Data are shown as mean±s.e.m. Lines were fitted to the data using GraphPad Prism4 linear regression analysis. Best-fit r2 values were 0.97 (phenformin), 0.71 (AICAR) and 0.2 (metformin). There was a significant correlation between Iamiloride and Ioubain cells treated with phenformin (P=0.01, n=4), but not in cells treated with AICAR or metformin. AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside; Iamiloride, amiloride-sensitive short circuit current; Iouabain, ouabain-sensitive short circuit current; Isc, short circuit current.

Measurement of intracellular nucleotide concentration

As maximal inhibition of Iouabain occurred 4 h after treatment with phenformin and AICAR, we investigated the amount of cellular nucleotides at this time, as we hypothesized that alteration of cellular nucleotides could have additional effects on ENaC and Na+K+ATPase. Treatment with phenformin decreased cellular ATP (Table 1). This was associated with significant increases in cellular ADP and AMP, and a fivefold increase in the AMP:ATP ratio compared to control (Table 1). Metformin also increased ADP, AMP and the AMP:ATP ratio (1.3-fold compared to control), but these changes were much smaller than that seen with phenformin, and we could not detect any changes in cellular ATP levels. These data are consistent with their action as inhibitors of Complex 1 of the respiratory chain. Interestingly, AICAR significantly decreased cellular ATP and ADP. This was associated with a decrease in the total adenine nucleotide pool and did not change the AMP:ATP or ADP:ATP ratios compared to controls (Table 1).

Effect of phenformin, metformin and AICAR on NAD(P)H autofluorescence

There was a significant increase in NAD(P)H autofluorescence in cells treated with phenformin for 1 h, compared to controls. No autofluorescence was detected in cells treated with AICAR (1 h) or metformin (4 h) (Figure 8). These data indicate that phenformin is a more potent inhibitor of Complex 1 than metformin, and that AICAR has no effect on mitochondrial respiration.

Figure 8.

Effect of phenformin, AICAR and metformin on NAD(P)H autofluorscence. Cells were pretreated in culture for 1–4 h with either 5 mM phenformin, 2 mM AICAR or 2 mM metformin. (a) Panels on the left show representative transmission images of untreated (control) or treated cells (phenformin) (AICAR) (metformin) within the field of view with the corresponding emitted light after 405 nm excitation shown on the right. (b) Fluorescence intensity measurements were made from 20 cells within fields of view acquired from three independent experiments using Zeiss LSM 510 software and data plotted as arbitrary units and shown as mean±s.e.m. *** significantly different from control, P<0.001, n=20. AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside. NAD(P)H, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate).

Discussion and conclusions

We previously showed that both isoforms of AMPK, α1 and α2, were present in H441 cells (Woollhead et al., 2005). In this study, we show that it is the α1 catalytic subunit of AMPK that is predominantly expressed and pharmacologically activated in H441 lung cells. Consistent with our findings, α1-AMPK protein has been localized to the apical membrane of polarized human bronchiolar epithelial cells and catalytic activity was associated with the α1 subunit in Calu-3 lung epithelial cells (Crawford et al., 2005; Hallows et al., 2006). The functional implications of different isoform activation is not yet fully understood, but could underlie tissue-specific differences in AMPK regulation and distribution (Kemp et al., 2003).

We show for the first time that metformin activated AMPK in H441 cell monolayers, although its effect was less potent than that of phenformin and AICAR (Woollhead et al., 2005). The biguanides inhibit Complex 1 of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Consistent with results from a number of other cell types (Hawley et al., 2002; Fryer et al., 2002a), metformin was a less effective metabolic inhibitor in H441 cells, inducing a much smaller change in the cellular AMP:ATP ratio compared to phenformin and with no significant effect on NAD(P)H autofluorescence. This difference in efficacy between the two biguanide drugs most likely reflects the difference in their chemical structure and the increased lipophilic nature of phenformin (Jalling and Olsen, 1984; Holstein and Egberts, 2006). AMPK is reported to be activated by very small changes in the AMP:ATP ratio, because of its ultrasensitive mechanism of activation (Hardie et al., 1999). However, we suggest that the level of AMPK activity induced by the biguanides in H441 cells is related to their effect on the AMP:ATP ratio.

As expected, AICAR did not change the cellular AMP:ATP ratio or NAD(P)H levels, consistent with its direct action on AMPK. However, it did decrease the cellular content of ATP, ADP and AMP in H441 cells. Why this occurred is unclear. In short-term incubations (up to 1 h) of rat hepatocytes and cultured mouse muscle cells, 0.5 mM AICAR has been reported not to affect cellular ATP, ADP or AMP levels (Corton et al., 1995; Fryer et al., 2002a) and in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells incubated for up to 10 h AICAR transiently increased ATP and its diphosphate and monophosphate forms (Sabina et al., 1985).

Iamiloride

We show that metformin decreased transepithelial amiloride-sensitive Na+ transport (Iamiloride) across H441 cells. The effect of metformin was slower than that of AICAR or phenformin and mirrored the lower level of α1-AMPK activity. Thus, together with our previous findings, these data indicate that activation of AMPK was the mechanism by which these drugs inhibited Iamiloride. In support of this, we found that the AMPK inhibitor Compound C prevented the AICAR- and metformin-induced reduction in Iamiloride. In contrast, Compound C did not prevent the inhibitory action of phenformin. This finding contradicts our previous suggestion that phenformin acted via AMPK to decrease Iamiloride. It is important to note that the specificity of Compound C has not been fully reported (Zhou et al., 2001), and some caution is required in the interpretation of its effect. However, this new finding raises the possibility that phenformin elicited an effect on Iamiloride that was either independent of, or additional to, pharmacological activation of AMPK.

Transepithelial Iamiloride can be decreased by inhibition of apical ENaC channels and/or by downregulating basolateral Na+K+ATPase transport capacity, which would reduce the Na+ gradient and the driving force for Na+ transport via ENaC. The most likely explanation for our new observation that metformin elevated AMPK activity and inhibited Iamiloride, but had no significant effect on Na+K+ATPase, would be that activation of AMPK must primarily inhibit apical Na+ entry, via the amiloride-sensitive Na+ channel ENaC, to decrease Iamiloride independently of effects on Na+K+ATPase function. This hypothesis would also explain why the fall in Iamiloride was greater than that of Iouabain when cells were treated with AICAR, and why there was no significant relationship between the fall in Iamiloride and Iouabain over time with metformin or AICAR. Although we have not yet fully investigated the effect of metformin on apical Na+ conductance (GNa+), we have previously shown that treatment of H441 cells with AICAR decreased apical amiloride-sensitive GNa+ (Woollhead et al., 2005). Furthermore, Carattino et al. (2005) showed that injection of ZMP (the active form of AICAR) and constitutively active AMPK inhibited the activity of ENaCs expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

The rapid effect (within 4 h) of AICAR on Iamiloride determined in this study and our previous study would support a post-transcriptional mechanism of action of AMPK on ENaC-mediated Na+ transport. This could include changes in ENaC open probability (Po) and/or the number of channels in the membrane (n) by disruption of the normal ENaC retrieval and recycling processes (Carattino et al., 2005). However, the further decline in Iamiloride associated with AICAR and metformin between 8 and 24 h means that we cannot exclude additional effects of AMPK on ENaC gene transcription or RNA stability in these cells. Both possibilities are the subject of further study.

Iouabain

Phenformin and AICAR both inhibited Iouabain, although the effect of AICAR was less potent and was reversible with Compound C. Interestingly, an effect common to phenformin and AICAR, but not metformin, was that they evoked a significant decrease in monolayer resistance (Rt) after 8 h. As a reduction in the live/dead cell ratio was only observed after a 24 h treatment with phenformin and metformin but not AICAR, we reasoned that the effect on Rt was unlikely to be due to a reduction in cellular viability. Recent reports have indicated that Na+K+ATPase is important in regulating tight junction formation (Kaplan, 2005; Rajasekaran et al., 2005). Thus, the inhibition of its transport capacity by phenformin and AICAR may be the mechanism by which epithelial resistance is lost.

Reduction of the intracellular Na+ concentration intracellular Na+ ([Na+]i) by inhibition of apical Na+ entry has been shown to decrease Na+K+ATPase surface expression and activity in cortical collecting duct cells (Vinciguerra et al., 2003). However, our new data show that the inhibition of Iouabain preceded inhibition of Iamiloride and there was no significant correlation between the inhibition of Iamiloride and Iouabain with AICAR or metformin. We previously suggested that activation of AMPK with phenformin and AICAR could inhibit Na+K+ATPase directly. The finding that AICAR inhibition of Iouabain was reversed by Compound C would support our suggestion. However, Compound C did not reverse the effect of phenformin and metformin activated AMPK, but had no effect on Iouabain. These findings raise the possibility that other mechanisms are involved. Both phenformin and AICAR decreased cellular ATP levels (metformin did not) and Na+K+ATPase function is dependent on ATP concentration. We previously suggested that only a drastic depletion of ATP would alter Na+K+ATPase activity (Boldyrev et al., 1991; Woollhead et al., 2005). However, more recent evidence indicates that the relationship between intracellular ATP concentration and Na+K+ATPase function is non-hyperbolic and involves binding of ATP to both high- and low-affinity sites on the protein (Ward and Cavieres, 1998; Ward et al., 2006). Thus, a reduction in ATP could lead to a decrease in Na+K+ATPase function. Certainly, a diminution of ATP in renal cortical tubular cells (Coux et al., 2001) and reduced ATP levels in rat cerebellar granule cells (Petrushanko et al., 2006) were associated with a reduction of Na+K+ATPase function. Moreover, Compound C has been shown to inhibit AICAR uptake into cells and subsequent accumulation of ZMP. It could, therefore, prevent the effect on cellular nucleotides, in addition to any direct inhibition of AMPK activity (Fryer et al., 2002b). In vitro, Na+K+ATPase transport activity is also decreased by increased ADP concentration (Boldyrev et al., 1991). As cellular ADP levels were increased 200% by phenformin; this could be an additional factor contributing to the greater inhibition of Iouabain by this drug compared to AICAR. Finally, Luly et al. (1977) showed that phenformin rapidly inhibited Na+K+ATPase activity in isolated liver plasma membranes. Their suggestion that phenformin could alter the physico-chemical properties of the membrane and change the activities of membrane bound enzymes could provide another AMPK-independent mechanism of action.

Whatever the mechanism, the powerful inhibitory effect of phenformin on Iouabain could underlie the AMPK-independent action and the more potent effect on Iamiloride compared to AICAR. Inhibition of Na+K+ATPase would elevate [Na+]i, reducing the driving force for Na+ entry. Increases in [Na+]i have also been shown to decrease ENaC activity by ‘feedback inhibition' (Garty and Palmer, 1997) in a number of cell systems, including salivary duct cells (Dinudom et al., 1998), rat cortical collecting tubule (Frindt et al., 1995) and Xenopus oocytes expressing ENaC (Abriel and Horisberger, 1999). The observation that there was a very close relationship between Iamiloride and Iouabain in cells treated with phenformin, coupled with our previous finding that phenformin decreased apical GNa+, indicates that the AMPK-independent action of phenformin could involve such a mechanism.

In conclusion, we show for the first time that metformin decreases transepithelial amiloride-sensitive Na+ transport across H441 lung cells. This finding has significant implications for its future therapeutic use. We also show that the three pharmacological activators of AMPK we have used have different effects on Na+ transport processes across lung epithelium. Importantly, our data show that while pharmacological activation of α1-AMPK is associated with inhibition of amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels (ENaC), additional changes in intracellular nucleotide levels (AICAR and phenformin) and potential effects on membrane fluidity (phenformin) could also affect basolateral Na+K+ATPase transport capacity, with ensuing effects on apical Na+ conductance, ENaC activity and monolayer resistance. More work is now required to elucidate the cellular mechanisms by which AMPK and cellular nucleotide concentrations evoke such changes. In the interim, these findings have important consequences for the clinical use of pharmacological activators of AMPK, and the interpretation of their effect in other cell systems where Na+K+ATPase is an important component.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust Grant Nos. 068674/Z/02/Z and 07235/Z/03/A. JWS, KJM and DGH are supported by the EXGENESIS Integrated Project (LSHM-CT-2004-005272) funded by the European Commission. The authors would also like to thank Mandy Skasick for her technical assistance with the cell culture.

Abbreviations

- AICAR

5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside

- AMPK

adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- GNa+

Na+ conductance

- Iamiloride

amiloride-sensitive short circuit current

- Iouabain

ouabain-sensitive short circuit current

- Isc

short circuit current

- NAD(P)H

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate)

- [Na+]i

intracellular Na+

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulphate

- ZMP

5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranosyl (AICAR) 5′monophosphate

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Abriel H, Horisberger JD. Feedback inhibition of rat amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channels expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. J Physiol. 1999;516 Part 1:31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.031aa.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldyrev AA, Fedosova NU, Lopina OD. The mechanism of the modifying effect of ATP on Na(+)–K+ ATPase. Biomed Sci. 1991;2:450–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher RC, Cotton CU, Gatzy JT, Knowles MR, Yankaskas JR. Evidence for reduced Cl− and increased Na+ permeability in cystic fibrosis human primary cell culture. J Physiol. 1988;405:77–103. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattino MD, Edinger RS, Grieser HJ, Wise R, Neumann D, Schlattner U, et al. Epithelial sodium channel inhibition by AMP-activated protein kinase in oocytes and polarized renal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17608–17616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corton JM, Gillespie JG, Hawley SA, Hardie DG. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside. A specific method for activating AMP-activated protein kinase in intact cells. Eur J Biochem. 1995;229:558–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coux G, Trumper L, Elias MM. Cortical Na+, K+-ATPase activity, abundance and distribution after in vivo renal ischemia without reperfusion in rats. Nephron. 2001;89:82–89. doi: 10.1159/000046048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford RM, Treharne KJ, Best OG, Muimo R, Riemen CE, Mehta A. A novel physical and functional association between nucleoside diphosphate kinase A and AMP-activated protein kinase alpha1 in liver and lung. Biochem J. 2005;392:201–209. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Dinudom A, Harvey KF, Komwatana P, Young JA, Kumar S, Cook DI. Nedd4 mediates control of an epithelial Na+ channel in salivary duct cells by cytosolic Na+ Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7169–7173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Mir MY, Nogueira V, Fontaine E, Averet N, Rigoulet M, Leverve X. Dimethylbiguanide inhibits cell respiration via an indirect effect targeted on the respiratory chain complex I. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:223–228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frindt G, Silver RB, Windhager EE, Palmer LG. Feedback regulation of Na channels in rat CCT. III. Response to cAMP. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:F480–F489. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.268.3.F480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer LG, Parbu-Patel A, Carling D. The Anti-diabetic drugs rosiglitazone and metformin stimulate AMP-activated protein kinase through distinct signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2002a;277:25226–25232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer LG, Parbu-Patel A, Carling D. Protein kinase inhibitors block the stimulation of the AMP-activated protein kinase by 5-amino-4-imidazolecarboxamide riboside. FEBS Lett. 2002b;531:189–192. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03501-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadalla AE, Pearson T, Currie AJ, Dale N, Hawley SA, Sheehan M, et al. AICA riboside both activates AMP-activated protein kinase and competes with adenosine for the nucleoside transporter in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus. J Neurochem. 2004;88:1272–1282. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garty H, Palmer LG. Epithelial sodium channels: function, structure and regulation. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:359–396. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallows KR, Fitch AC, Richardson CA, Reynolds PR, Clancy JP, Dagher PC, et al. Up-regulation of AMP-activated kinase by dysfunctional cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells mitigates excessive inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4231–4241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG, Sakamoto K. AMPK: a key sensor of fuel and energy status in skeletal muscle. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006;21:48–60. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG. Minireview: the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade: the key sensor of cellular energy status. Endocrinology. 2003;144:5179–5183. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG. The AMP-activated protein kinase pathway—new players upstream and downstream. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5479–5487. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG, Salt IP, Davies SP. Analysis of the role of the AMP-activated protein kinase in the response to cellular stress. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;99:63–74. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-054-3:63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG, Salt IP, Hawley SA, Davies SP. AMP-activated protein kinase: an ultrasensitive system for monitoring cellular energy charge. Biochem J. 1999;338:717–772. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley SA, Gadalla AE, Olsen GS, Hardie DG. The antidiabetic drug metformin activates the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade via an adenine nucleotide-independent mechanism. Diabetes. 2002;51:2420–2425. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.8.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley SA, Pan DA, Mustard KJ, Ross L, Bain J, Edelman AM, et al. Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta is an alternative upstream kinase for AMP-activated protein kinase. Cell Metab. 2005;2:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstein A, Egberts EH.Traditional contraindications to the use of metformin—more harmful than beneficial Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2006131105–110.. Review [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalling O, Olsen C. The effects of metformin compared to the effects of phenformin on the lactate production and the metabolism of isolated parenchymal rat liver cell. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenhagen) 1984;54:327–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1984.tb01938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalsi KK, Smolenski RT, Pritchard RD, Khaghani A, Seymour AM, Yacoub MH. Energetics and function of the failing human heart with dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Clin Invest. 1999;29:469–477. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1999.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JH. A moving new role for the sodium pump in epithelial cells and carcinomas. Sci STKE. 2005;289:31. doi: 10.1126/stke.2892005pe31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp BE, Stapleton D, Campbell DJ, Chen ZP, Murthy S, Walter M, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase, super metabolic regulator. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:162–168. doi: 10.1042/bst0310162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall M, Stuart J. The advanced theory of statistics. The Statistician. 1968;18:163–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kerem E, Bistritzer T, Hanukoglu A, Hofmann T, Zhou Z, Bennett W, et al. Pulmonary epithelial sodium-channel dysfunction and excess airway liquid in pseudohypoaldosteronism. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:156–162. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907153410304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luly P, Baldini P, Cocco C, Incerpi S, Tria E. Effect of chlorpropamide and phenformin on rat liver: the effect on plasma membrane-bound enzymes and cyclic AMP content of hepatocytes in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol. 1977;46:153–164. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(77)90251-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mairbaeurl H, Mayer K, Kim K-J, Borok Z, Baertsch P, Crandall ED. Hypoxia decreases active Na transport across primary rat alveolar epithelial cell monolayers. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L659–L665. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00355.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen MR, Doran E, Halestrap AP. Evidence that metformin exerts its anti-diabetic effects through inhibition of complex 1 of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Biochem J. 2000;348 Part 3:607–614. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrushanko I, Bogdanov N, Bulygina E, Grenacher B, Leinsoo T, Boldyrev A, et al. Na–K-ATPase in rat cerebellar granule cells is redox sensitive. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R916–R925. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00038.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekaran SA, Barwe SP, Rajasekaran AK. Multiple functions of Na, K-ATPase in epithelial cells. Semin Nephrol. 2005;25:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramminger SJ, Baines DL, Olver RE, Wilson SM. The effects of PO2 upon transepithelial ion transport in fetal rat distal lung epithelial cells. J Physiol. 2000;524.2:539–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabina RL, Patterson D, Holmes EW. 5-Amino-4 imidazolecarborramide Riboside (Z-riboside) metabolism in eukaryotic cells. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:6107–6114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto K, Goransson O, Hardie DG, Alessi DR. Activity of LKB1 and AMPK-related kinases in skeletal muscle: effects of contraction, phenformin, and AICAR. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E310–E317. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00074.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolenski RT, Lachno DR, Ledingham SJ, Yacoub MH. Determination of sixteen nucleotides, nucleosides and bases using high-performance liquid chromatography and its application to the study of purine metabolism in hearts for transplantation. J Chromatogr. 1990;527:414–420. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)82125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutts MJ, Gatzy JT, Boucher RC. Effects of metabolic inhibition on ion transport by dog bronchial epithelium. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:253–258. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.1.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinciguerra M, Deschenes G, Hasler U, Mordasini D, Rousselot M, Doucet A, et al. Intracellular Na+ controls cell surface expression of Na, K-ATPase via a cAMP-independent PKA pathway in mammalian kidney collecting duct cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:2677–2688. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward DG, Cavieres JD. Photoinactivation of fluorescein isothiocyanate-modified Na, K-ATPase by 2*(3*)-O-(2, 4, 6-trinitrophenyl)8-azidoadenosine 5*-diphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14277–14284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward DG, Taylor M, Lilley KS, Cavieres JD. TNP-8N3-ADP photoaffinity labelling of two Na, K-ATPase sequences under separate Na+ plus K+ control. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3460–3471. doi: 10.1021/bi051927k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woollhead AM, Scott JW, Hardie DG, Baines DL. Phenformin and 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-{beta}-D-ribofuranoside (AICAR) activation of AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits transepithelial Na+ transport across H441 lung cells. J Physiol. 2005;566:781–792. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.088674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, Chen Y, Shen X, Fenyk-Melody J, et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1167–1174. doi: 10.1172/JCI13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]