Abstract

Pollen tubes are a good model for the study of cell growth and morphogenesis because of their extreme elongation without cell division. Yet, knowledge about the genetic basis of pollen germination and tube growth is still lagging behind advances in pollen physiology and biochemistry. In an effort to reduce this gap, we have developed a new method to obtain highly purified, hydrated pollen grains of Arabidopsis through flowcytometric sorting, and we used GeneChips (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA; representing approximately 8,200 genes) to compare the transcriptional profile of sorted pollen with those of four vegetative tissues (seedlings, leaves, roots, and siliques). We present a new graphical tool allowing genomic scale visualization of the unique transcriptional profile of pollen. The 1,584 genes expressed in pollen showed a 90% overlap with genes expressed in these vegetative tissues, whereas one-third of the genes constitutively expressed in the vegetative tissues were not expressed in pollen. Among the 469 genes enriched in pollen, 162 were selectively expressed, and most of these had not been associated previously with pollen. Their functional classification reveals several new candidate genes, mainly in the categories of signal transduction and cell wall biosynthesis and regulation. Thus, the results presented improve our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms underlying pollen germination and tube growth and provide new directions for deciphering their genetic basis. Because pollen expresses about one-third of the number of genes expressed on average in other organs, it may constitute an ideal system to study fundamental mechanisms of cell biology and, by omission, of cell division.

Pollen has been the subject of intense studies not only for its importance as the male partner in plant reproduction, but also as a model for the study of cell growth and morphogenesis in a broader sense (Feijó et al., 2001). Whereas early studies focused on pollen physiology and biochemistry (for review, see Mascarenhas, 1975), the last 20 years have been marked by increasing efforts to decipher the genetic basis of pollen development and functions (for reviews, see Scott et al., 1991; McCormick, 1993; Preuss, 1995; Taylor and Hepler, 1997; Franklin-Tong, 1999; Hepler et al., 2001; Lord and Russell, 2002). These efforts led to the identification of more than 150 pollen-expressed genes from more than 28 species (Twell, 2002). These genes encode proteins thought or known to be involved in pollen development, pollen germination, and pollen tube growth, as well as in interactions with the stigma/transmitting tissue or the female gametophyte. Many of these studies were conducted in Lilium sp. or in Solanaceae species, because their pollen is easily collected in sufficient quantities, and methods for in vitro germination are robust. However, the available genetic information for these species is limited. The availability of the genome sequence of Arabidopsis (The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative, 2000) and the concomitant increase in available genomic tools (Wixon, 2001) make Arabidopsis a preferable model for large scale genetic studies of pollen germination and tube growth. The shift toward Arabidopsis is reflected in recent studies of the cellular organization and ultrastructure of in vivo- and in vitro-grown pollen tubes of Arabidopsis (Lennon and Lord, 2000; Derksen et al., 2002) and by efforts to improve in vitro germination of Arabidopsis pollen (Fan et al., 2001).

Studies in several plant species have indicated that the bulk of mRNAs needed for pollen germination and tube growth accumulates in pollen grains well before germination (Mascarenhas, 1989; Guyon et al., 2000). Thus, we expected that identifying transcripts that were enriched (up-regulated gene expression) or even selectively expressed in hydrated pollen grains on a genomic scale would increase significantly our knowledge of the genetic basis of pollen germination and tube growth. We chose an approach using pollen of Arabidopsis and overcame the limitations of small-scale transcriptional analysis applying oligonucleotide-based microarray technology. The Arabidopsis Genome GeneChip array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) has been used to examine the transcriptional regulation of genes in Arabidopsis by the circadian clock (Harmer et al., 2000) and to identify gene expression changes during shoot development (Che et al., 2002). As a prerequisite for high-quality transcriptional profiles of pollen grains, we developed a protocol using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to obtain highly purified hydrated pollen grains of Arabidopsis. We obtained transcriptional profiles for hydrated pollen grains and for four types of vegetative tissues (leaves, roots, seedlings, and siliques) of Arabidopsis. By comparison of these data sets we show that the transcriptional profile of Arabidopsis pollen is clearly distinguishable from those of the vegetative tissues. About 1,500 genes (approximately 90%) expressed in pollen grains are also expressed in at least one of the vegetative tissues, whereas the remaining 10% (162 genes) are selectively expressed in pollen. Most of these 162 genes have not been described as selectively expressed in Arabidopsis pollen before, and their functional classification yields new insights into several aspects of the genetic program underlying germination and tube growth of Arabidopsis pollen.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

FACS Yields Highly Purified Arabidopsis Pollen Grains

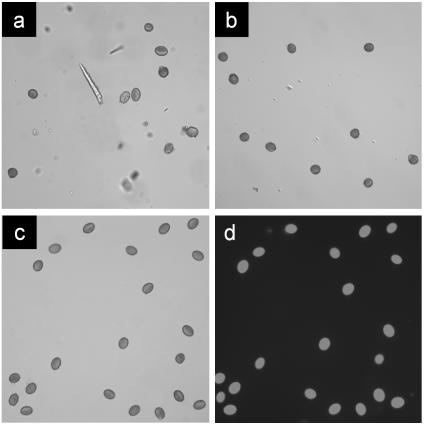

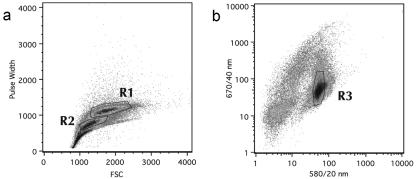

An essential requirement for obtaining high-quality DNA array data is purity of the tissue or cellular source for RNA extraction, because any kind of impurity could result in an inaccurate transcriptional profile. Because the reported sensitivity of the Arabidopsis Genome GeneChip arrays is one transcript in 100,000 to one transcript in 300,000 (Zhu and Wang, 2000), we consider this requirement especially important for pollen. Therefore, we have developed a new protocol to obtain highly purified, hydrated pollen grains. Prehydrated pollen was washed out from flowers in buffer and subjected to filtering steps. The resulting solution contained fully hydrated pollen grains (oval shape), non-hydrated and/or destroyed pollen grains (round shape) as well as smaller impurities (Fig. 1A). For a final purification step, we used FACS using the size and autofluorescence properties of pollen. To separate hydrated from non-hydrated pollen, a two-dimensional histogram using the forward scatter versus pulse width parameters was used, and an additional gate was then applied on the 670/40 and 580/20 nm detection channels to further purify the pollen grains based on their characteristic autofluorescence properties (see Fig. 2). The characteristic oval shape of fully hydrated pollen grains caused a longer pulse when passing the laser, thus allowing a separation of the non-hydrated pollen grains and smaller impurities from the fully hydrated pollen grains (Fig. 1, B and C). The purity of the hydrated pollen grain fraction was routinely >99%. The viability of the hydrated pollen grains was assessed by fluorescein diacetate staining (Fig. 1D). The remaining impurities (<1%) consisted of very small debris, which most likely did not include organelles. One hundred-fifty thousand hydrated pollen grains yielded 1 μg of total RNA. More than 500,000 non-hydrated pollen grains resulted in the same yield, supporting our assumption that the majority of the non-hydrated pollen grains were not intact.

Figure 1.

Purification steps and viability of Arabidopsis pollen. Pollen and impurities before sorting (A) were separated into non-hydrated (B) and hydrated pollen (C) by flowcytometric sorting. D, A viability stain of the sorted, hydrated pollen grains.

Figure 2.

Flowcytometric sorting of Arabidopsis pollen. Arabidopsis pollen was identified through its size (A) and autofluorescence properties (B). A, Hydrated pollen was located in region R1 of the pulse width versus Forward Scatter (FSC) display, whereas non-hydrated pollen was mostly contained in R2. B, For sorting, a logical gate combination of regions R1 and R3 was used.

Pollen Grains Have a Unique Transcriptional Profile

Gene expression patterns of approximately 8,200 genes, representing roughly one-third of the Arabidopsis genome, were obtained for Arabidopsis pollen grains and for several vegetative tissues: seedlings, leaves, root, and siliques. The results were highly reproducible as underlined by the high correlation coefficients of the replicates, which ranged from 0.977 to 0.992. For each vegetative tissue, a similar percentage of genes were called Present by the MAS 5 algorithm, with a mean of 59% in seedlings, 56% in leaves, and 64% in roots and siliques. In contrast, only 21% of the genes represented on the arrays were called Present in the pollen samples (1584 unique genes). Normalization reduces variation of non-biological origin and is therefore a prerequisite for the direct comparison of expression profiles from different arrays. The large differences in the transcriptional profiles in this study, i.e. the sample-specific differences in Presence calls, precluded the use of global scaling/normalization methods. Instead, we employed a sample-wise normalization to the median median probe cell intensity of all arrays, implemented into version 1.3 of the dChip software (http://www.dchip.org; Wong laboratory, Harvard, Boston). This method works independently from the overall intensity of an array. After normalization and model-based computation of expression values, we excluded genes called Absent in all arrays and genes with inconsistent expression levels within the replicate arrays. Thus, for further analysis, our data set contained 6,459 genes.

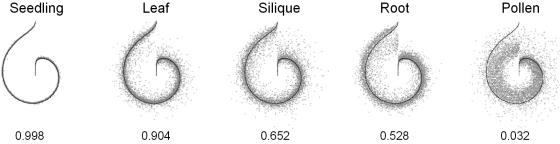

We developed a new graphical tool to visualize the striking differences between the transcriptional profiles of the vegetative tissues and pollen (Fig. 3). This tool, “Snail View”, compares and displays the changes in expression levels of thousands of genes simultaneously, but still allows meaningful interpretations of the overview obtained (the software can be downloaded at http://eao.igc.gulbenkian.pt/ti/Soft/SnailView/). The average expression value in the seedling samples were chosen as reference, considering that seedlings probably contain cell types found in roots, leaves and, most likely, in siliques. The high correlation of data derived from the replicates is exemplified by the comparison of expression values obtained for the single-seedling replicates. This high correlation is visualized by the small deviations from the line representing the average value of the seedling replicates. The expression values of leaves and of seedlings are strongly correlated, especially for those genes with the highest expression level in seedlings. The cotyledons contribute the largest part to the biomass of 4-d-old seedlings, so this similarity was anticipated. Expression values obtained for siliques and root samples show high deviations from the seedling reference. Genes highly expressed in seedlings are down-regulated (most considerably in roots), and those with low expression levels in seedlings are up-regulated (most considerably in siliques). The most dramatic differences are seen in the pollen to seedling comparison. Most genes with high or medium expression values in seedlings show low expression values in pollen. This trend is reversed for genes with low expression values in seedlings, because a high proportion of these genes are highly expressed in pollen and reach expression values comparable with those of genes with the highest expression in seedlings. The correlation coefficients (0.032, 0.029, 0.040, and 0.067) of the expression values of pollen relative to expression values of seedlings, leaves, siliques, and roots, show that pollen has a transcriptional profile that is clearly distinguished from that of vegetative tissues.

Figure 3.

“Snail view” representation of tissue-dependent gene expression patterns. The expression for 5,999 genes is represented in angular coordinates, in which angle encodes gene rank (clockwise from top) and radius encodes the logarithm of gene expression (values <1 were set to 1 for better visualization). Genes were ranked according to increasing mean expression in seedlings. For each tissue, the mean pattern in seedlings (black line) is coplotted with the mean pattern of specific tissue (gray dots), except for seedling where one replicate is coplotted. The values are the correlation coefficient between the gene expression patterns in the two tissues (for seedlings between the replicates).

Ten Percent of the Genes Expressed in Pollen Are Not Expressed in the Sporophyte

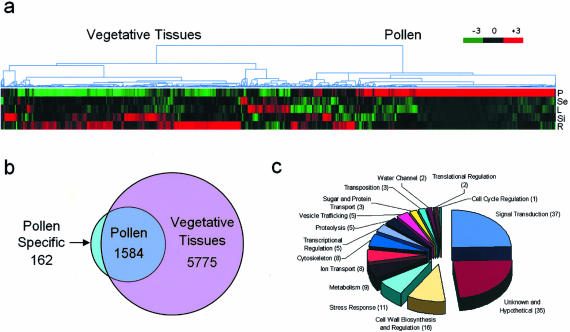

We assumed that gene products of transcripts that were highly enriched or even selectively expressed in pollen grains might be of major importance, if not crucial for successful pollen germination and tube growth. To identify such genes, we followed two complementing approaches. First, we measured enrichment in gene expression as the lower limit (lower confidence bound) of a 90% confidence interval for the fold change in gene expression. Gene expression values in pollen were compared with those in each of the vegetative tissues, and a score above 1.2 was used as the criterion to select genes enriched in pollen; 469 genes met this criterion in all four comparisons (supplemental Table I). Second, we used Affymetrix MAS 5 Present calls to sort genes; 5,775 genes were reproducibly called Present in at least one of the four vegetative tissues. Of the 1,584 genes called Present in pollen (for hierarchical clustering, see Fig. 4A), 1,422 (90%) showed an overlap with the genes detected in vegetative tissues (Fig. 4B). The remaining 10% (162 genes) were called Present only in pollen and are referred to as selectively expressed from hereon. The two methods yielded an overlap of 150 genes that we characterized in more detail.

Figure 4.

Analysis of genes enriched or selectively expressed in pollen. A, Hierarchical cluster analysis of the 1,584 genes called Present in pollen. Default parameters in dChip were used (standardization and clustering methods follow Golub et al. [1999] and Eisen et al. [1998]). Each column represents a single gene, and each row a single tissue type. Genes mainly enriched in pollen are found in the right cluster, whereas those expressed in pollen but with higher expression values in at least one of the vegetative tissues are found in the left cluster. P, Pollen; Se, seedling; L, leaf; Si; silique; R, root. B, Venn diagram depicting total numbers of genes expressed in vegetative tissues and in pollen. Genes were scored as Present in the vegetative tissues, if they received at least one Present call (MAS 5) in the seedling, leaf, root, or silique sample (5,775 genes). In pollen, 1,422 genes of these were also called Present. A set of 162 genes was exclusively called Present in pollen. Genes recognized by more than one probe set in the Affymetrix array were only counted once. C, Overview of the functional classification of 150 pollen selectively expressed genes listed in Table I. Total number of genes in each category is given in brackets. Functional classification is based on established as well as putative functions.

Thus, our expression analysis of roughly one-third of the annotated genes of Arabidopsis shows that 10% of the genes expressed in pollen are selectively expressed in pollen, whereas the other 90% are also expressed in one or more vegetative tissues. This substantial overlap of genes active in the sporophyte and in the male gametophyte had been predicted earlier based on isoenzyme studies in pollen and vegetative tissues in barley (Hordeum vulgare; Pederson et al., 1987), heterologous hybridizations of pollen cDNA with shoot poly(A) RNA and shoot cDNA to pollen poly(A) RNA in maize (Zea mays; Willing et al., 1988), as well as colony hybridizations of maize pollen cDNA libraries with cDNAs from pollen and vegetative tissues (Stinson et al., 1987).

Functional Classification of Selectively Expressed Genes

We sorted the 150 selectively expressed genes into functional categories (Table I; Fig. 4C), taking into consideration several aspects of current knowledge about the pollen grain and tube physiology. This categorization is based on known functions of the gene products as well as gene ontology annotations derived from homologies. Our analysis confirmed the expression of some genes already known to be expressed in pollen, but it also led to the identification of several genes not known to be expressed in the male gametophyte so far.

Table I.

Functional classification of genes selectively expressed in pollen

One hundred-fifty genes identified as selectively expressed in pollen are classified based on established as well as putative functions. The first column gives The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) annotation and the second gives the expression value of the gene in pollen (weighted average of triplicates). In the third column, the lower confidence bound fold change (FC; average of the comparisons of pollen to the four vegetative tissues) is given. The fourth and fifth column depict the Affymetrix probe set (Probes set) and, if available, the TAIR locus (AGIID) assigned to this probe set. Within each category, genes are ranked by highest signal.

| Annotation | Signal | Probe Set | Arabidopsis Genome Initiative Identification (AGI ID) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signal transduction (37) | ||||

| Putative protein kinase | 4,728 | 76.8 | 17803_at | At1g61860 |

| Putative receptor-like protein kinase | 4,061 | 78.4 | 18205_s_at | At4g39110 |

| Putative Pro extensin-like receptor kinase PERK7 | 4,010 | 20.3 | 17812_at | At1g49270 |

| Putative calcium-dependent protein kinase CPK24 | 3,538 | 160.8 | 16806_s_at | At2g31500 |

| Putative 4,5 PIP kinase | 3,425 | 45.9 | 19788_at | At1g01460 |

| Putative calmodulin | 3,326 | 214.9 | 13415_at | At4g03290 |

| Putative Leu-rich repeat transmembrane protein kinase AtPRKc | 3,051 | 80.7 | 19047_at | At2g07040 |

| Putative phosphatidylinositol/phophatidylcholine transfer protein | 1,887 | 15.0 | 19052_at | At2g18180 |

| Putative calcium-dependent protein kinase CPK14 | 1,511 | 250.6 | 20236_s_at | At2g41860 |

| Putative protein kinase | 1,083 | 16.9 | 18152_at | At2g24370 |

| Putative Leu-rich repeat transmembrane protein kinase AtPRKd | 1,026 | 17.2 | 19103_at | At5g35390 |

| Calcium-dependent protein kinase-like protein CPK26 | 854 | 26.4 | 20241_at | At4g38230 |

| Putative Ser/Thr protein kinase | 725 | 21.7 | 14364_at | At1g04700 |

| Putative protein kinase (cdc2 kinase homolog cdc2MaC, M. sativa) | 670 | 48.9 | 16824_at | At4g10010 |

| Putative GTP-binding protein | 652 | 11.6 | 18107_at | At2g33870 |

| Putative inositol polyphosphate 5′-phosphatase | 636 | 8.8 | 19795_at | At2g43900 |

| Putative proline extensin-like receptor kinase PERK5 | 611 | 29.0 | 16876_at | At4g34440 |

| Putative protein (GTPase-activating protein, Yarrowia lipolytica) | 574 | 4.9 | 16758_at | At4g27100 |

| Putative inositol polyphosphate 5′-phosphatase | 563 | 17.1 | 19582_at | At2g31830 |

| Putative protein (various predicted protein kinases, Arabidopsis) | 532 | 11.0 | 18193_at | At5g26150 |

| AK20 gene protein kinase catalytic domain (fragment) | 519 | 6.1 | 19111_at | |

| Putative receptor-like Ser/Thr kinase RKF2 | 483 | 10.4 | 17496_at | At1g19090 |

| Putative Pro extensin-like receptor kinase PERK12 | 335 | 14.7 | 17359_at | At1g23540 |

| Hypothetical protein (similar to wall-associated kinase 1, Arabidopsis) | 324 | 10.8 | 18186_at | At1g78940 |

| Putative Ptα kinase interactor (similar to Ptα kinase interactor 1, tomato) | 300 | 3.8 | 18825_at | At4g13190 |

| Putative GTP-binding protein | 292 | 16.3 | 12489_at | At2g22290 |

| Protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) | 275 | 4.8 | 19345_at | At2g40180 |

| Putative calcium-dependent protein kinase CPK20 | 241 | 8.8 | 12311_at | At2g38910 |

| Putative calmodulin (calmodulin PIR1:MCKM, Chlamydomonas reinhardii) | 229 | 4.7 | 19274_i_at | At4g12860 |

| Protein kinase-like protein | 214 | 5.7 | 19556_at | At4g31220 |

| Putative protein (various predicted protein kinases, Arabidopsis) | 159 | 2.2 | 19071_at | At5g35380 |

| Putative Ser/Thr protein kinase | 110 | 4.0 | 16866_at | At1g79250 |

| Putative STE20/PAK-like protein kinase (similar to yeast STE20) | 74 | 4.7 | 18999_at | At1g70430 |

| Putative receptor-like kinase | 65 | 3.4 | 14275_at | At4g31230 |

| Putative protein kinase | 62 | 1.8 | 16848_at | At2g20470 |

| Putative phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase | 55 | 4.3 | 19310_at | At2g41210 |

| Calcium-dependent Ser/Thr protein kinase CPK18 | 44 | 1.8 | 16849_at | At4g36070 |

| Cell wall biosynthesis and regulation (16) | ||||

| Pectinesterase family (nearly identical to pollen-specific BP10 protein, canola) | 7,180 | 110.3 | 17753_at | At1g55570 |

| Exopolygalacturonase | 7,059 | 51.9 | 18923_g_at | At3g07850 |

| Extensin-like protein | 6,221 | 71.5 | 15765_at | At4g33970 |

| Putative polygalacturonase | 5,660 | 91.2 | 15716_at | At2g23900 |

| Putative cellulose synthase (AtCalD1—homolog of NaCalD1) | 4,911 | 58.9 | 20243_at | At2g33100 |

| Glycosyl hydrolase family 10 (xylan endohydrolase isoenzyme X-I, barley) | 4,536 | 40.1 | 13393_at | At4g33860 |

| Polysaccharide lyase family 1 (similar to pectate lyase P59, tomato) | 4,226 | 184.1 | 16837_at | At2g02720 |

| Polysaccharide lyase family 1 (At59) | 3,914 | 83.0 | 16857_at | At1g14420 |

| Putative cellulose synthase (AtCalD4—homolog of NaCalD1) | 3,489 | 28.5 | 16782_at | At4g38190 |

| Putative protein (bp4A protein, Brassica napus) | 1,196 | 51.4 | 15360_at | At4g11760 |

| COBRA-like protein COBL-11 | 929 | 13.1 | 15331_at | At4g27110 |

| Cellose synthase (1,3-β-glucan synthase) family (AtGal2, homolog of NaGal1) | 925 | 2.7 | 18515_at | At2g13675 |

| Pectinesterase family | 662 | 19.2 | 18519_at | At4g33230 |

| Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 (BETAG5, β-1,3-glucanase bg5) | 438 | 5.9 | 18539_at | At5g20340 |

| Putative xyloglucan endotransglycosylase | 214 | 5.8 | 19530_at | At4g18990 |

| Glycosyl hydrolase family 17 (BETAG4, β-1,3-glucanase bg4) | 214 | 2.3 | 18120_i_at | At5g20330 |

| Stress response (11) | ||||

| Putative plant defensin protein PDF2.6 | 9,739 | 53.2 | 19928_at | At2g02140 |

| Putative peroxiredoxin (similar to type 2 peroxiredoxin, Brassica rapa) | 3,640 | 7.3 | 15966_i_at | At1g60740 |

| 17.6-kD heat shock protein (AA 1-156) | 1,637 | 26.5 | 13276_at | At1g53540 |

| Heat shock protein 17.6A (At-HSP17.6A) | 731 | 17.2 | 13278_f_at | At5g12030 |

| Heat shock protein 22.0 (At-HSP22.0) | 431 | 8.6 | 17076_s_at | At4g10250 |

| Putative protein (similar to Mlo proteins, barley) | 402 | 4.8 | 14639_at | At2g33670 |

| Heat shock protein 18 | 299 | 3.1 | 13280_at | At5g59720 |

| Putative stress protein | 130 | 6.1 | 13378_at | At2g01330 |

| Putative peroxidase | 108 | 4.4 | 17828_at | At4g17690 |

| Mitochondrion-localized small heat shock protein (AtHSP23.6-mito) | 69 | 2.0 | 13282_s_at | At4g25200 |

| Putative disease resistance protein (TIR-NBS-LRR class) | 61 | 2.8 | 12258_at | At4g14370 |

| Metabolism (9) | ||||

| Glycosyl hydrolase family 35 (β-galactosidase) BGAL11 | 6,152 | 194.9 | 16874_at | At4g35010 |

| Glycosyl hydrolase family 32 (invertase) | 3,759 | 54.4 | 16369_s_at | At3g52600 |

| Glycosyl hydrolase family 35 (β-galactosidase) BGAL13 | 3,074 | 69.7 | 17316_at | At2g16730 |

| FAD-linked oxidoreductase family | 2,481 | 126.4 | 15302_at | At1g11770 |

| Putative thioredoxin | 2,236 | 21.2 | 19937_at | At2g33270 |

| Putative acyl-CoA:1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase | 656 | 10.4 | 18423_at | At1g51260 |

| 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase HMG1 isoform HMGR1L | 550 | 3.0 | 20160_at | |

| Glycosyl hydrolase family 1 | 101 | 18.6 | 19601_at | At2g25630 |

| Putative CDP-diacylglycerol synthetase | 53 | 1.7 | 19016_at | At4g26770 |

| Ion transport (8) | ||||

| Putative cation/H+ antiporter AtCHX8 | 3,259 | 17.1 | 17246_at | At2g28180 |

| Putative protein (anion exchange protein 2, Homo sapiens) | 3,208 | 67.1 | 18837_at | At4g32510 |

| Shaker potassium channel SPIK | 1,489 | 51.8 | 16783_at | At2g25600 |

| Putative cation/H+ antiporter AtCHX15 | 618 | 4.3 | 14334_at | At2g13620 |

| Ion transporter-like protein AtNRAMP5 | 404 | 30.2 | 18118_at | At4g18790 |

| Putative cyclic nucleotide-regulated ion channel AtCNGC16 | 205 | 8.3 | 14291_at | At3g48010 |

| G subunit of vacuolar-type H+-ATPase (vag1) | 78 | 5.3 | 16226_at | At4g25950 |

| Putative cation/H+ antiporter AtCHX13 | 60 | 2.4 | 15704_at | At2g30240 |

| Cytoskeleton (8) | ||||

| Actin 4 | 3,262 | 110.7 | 14356_at | At5g59370 |

| Actin depolymerizing factor-like protein | 3,092 | 37.4 | 12529_at | At4g25590 |

| Actin 12 | 1,815 | 35.8 | 15697_at | At3g46520 |

| Prolilin 4 | 2,691 | 25.8 | 12411_s_at | At2g19770 |

| Myosin heavy chain-like protein AtVIIIB | 341 | 19.7 | 12257_at | At4g27370 |

| Putative myosin heavy chain AtXID | 224 | 2.7 | 16327_at | At2g33240 |

| Putative myosin II heavy chain (Naegleria fowleri) | 179 | 6.2 | 15329_at | At4g33390 |

| Kinesin-related protein | 97 | 3.3 | 16794_at | At1g09170 |

| Transcriptional regulation (5) | ||||

| Putative protein (NorM, Vibrio parahaemolyticus) | 1,471 | 33.5 | 14992_at | At4g21900 |

| MYB97 (similar to anther-specific myb-related protein 2, tobacco) | 309 | 10.4 | 17979_at | At4g26930 |

| MADS-box protein AGL30 (homolog of MADS1;11, tobacco) | 167 | 5.2 | 18443_at | At2g03060 |

| MADS-box protein AGL29 | 154 | 15.8 | 19309_at | At2g34440 |

| CONSTANS B-box zinc finger family protein | 23 | 1.9 | 15698_at | At4g15250 |

| Proteolysis (5) | ||||

| Putative Ser carboxypeptidase II | 7,644 | 55.0 | 17765_at | At2g05850 |

| Ser-type carboxypeptidase-like protein | 4,000 | 117.4 | 18137_at | At3g52010 |

| Subtilisin-like Ser protease | 1,348 | 26.8 | 16349_at | At4g21326 |

| Ser-type carboxypeptidase-like protein | 721 | 12.1 | 17814_at | At3g52000 |

| Ser-type carboxypeptidase-like protein | 64 | 6.4 | 18461_at | At3g52020 |

| Vesicle trafficking (5) | ||||

| Syntaxin AtSYP124 | 1,243 | 10.7 | 15275_at | At1g61290 |

| ARF GTPase-activating domain-containing protein | 829 | 15.2 | 12639_at | At2g35210 |

| Clathrin protein family | 631 | 8.9 | 13499_at | At1g05020 |

| ARF GTPase-activating domain-containing protein | 598 | 4.4 | 17446_at | At2g14490 |

| Unknown protein (similar to yeast Sec7p protein) | 280 | 7.9 | 18381_at | At2g30690 |

| Sugar and protein transport (3) | ||||

| Monosaccharide transporter | 4,441 | 129.6 | 19270_at | At5g23270 |

| Putative ABC transporter AtNAP12 | 437 | 4.6 | 13049_at | At2g37010 |

| Putative vacuolar sorting receptor | 182 | 2.8 | 18509_at | At2g30290 |

| Transposition (3) | ||||

| Ac-like transposase (related to Ac/Ds transposon family of maize) | 198 | 4.8 | 16730_at | At2g16040 |

| Putative Mutator-like transposase | 118 | 2.1 | 12987_s_at | At2g30640 |

| Putative TNP2-like transposon protein | 60 | 2.6 | 19339_i_at | At2g10140 |

| Water channel (2) | ||||

| Aquaporin-like protein TIP5;1 (aquaporin, Vernicia fordii) | 1,497 | 13.6 | 18856_at | At3g47440 |

| Putative water channel protein—major intrinsic protein (MIP) TIP1;3 | 544 | 6.1 | 17798_at | At4g01470 |

| Translational regulation (2) | ||||

| Putative protein (similar to polyadenylate-binding protein PABP) | 429 | 10.9 | 16836_at | At3g16380 |

| Putative translation initiation factor | 65 | 5.2 | 18609_at | At2g39820 |

| Cell cycle regulation (1) | ||||

| Cyclin A2;1 | 89 | 1.8 | 16851_s_at | At5g25380 |

| Unknown and hypothetical (35) | ||||

| Arabinogalactan-protein AGP6 | 16,351 | 50.8 | 12003_at | At5g14380 |

| Nectarin-like protein (nectarin I precursor, Nicotiana plumbaginifolia) | 11,576 | 81.8 | 19014_at | At5g26696 |

| Hypothetical protein | 9,322 | 89.6 | 16201_at | At1g49490 |

| Unknown protein (homolog of protein ARPL 1;1) | 9,259 | 181.8 | 19385_at | At1g54070 |

| Putative LIM-domain protein (AtPLIM2) | 8,733 | 82.0 | 20478_at | At2g45800 |

| Unknown protein | 8,161 | 92.0 | 19301_at | At4g36490 |

| Unknown protein | 7,359 | 35.4 | 12568_at | At2g33420 |

| Putative pistil-specific protein (similar to potato pistil-specific protein STS15) | 7,018 | 149.3 | 14936_at | At4g02250 |

| Hypothetical protein | 4,933 | 47.1 | 13912_at | At1g04540 |

| Unknown protein | 3,744 | 101.5 | 12638_at | At1g04470 |

| Hypothetical protein | 3,186 | 61.3 | 18426_at | At2g13350 |

| Unknown protein | 1,225 | 42.7 | 17230_at | At2g40990 |

| Unknown protein | 962 | 96.2 | 20549_i_at | At2g26850 |

| Hypothetical protein | 818 | 33.4 | 17687_at | At1g60240 |

| Putative GDP-dissociation inhibitor | 753 | 28.9 | 19790_at | At1g12070 |

| Hypothetical protein | 466 | 5.4 | 15925_at | At1g43630 |

| Unknown protein | 420 | 13.4 | 13836_at | At1g06750 |

| Unknown protein | 379 | 27.4 | 15838_at | At2g29790 |

| Hypothetical protein | 377 | 2.7 | 13304_at | At1g24330 |

| Putative protein (MSP1, Saccharomyces cerevisiae) | 348 | 21.5 | 19604_at | At4g28000 |

| Unknown protein (related to MO25, early mouse development protein family) | 329 | 28.7 | 17711_at | At2g03410 |

| RALF-LIKE 10 | 313 | 7.0 | 18385_at | At2g19020 |

| Hypothetical protein | 258 | 6.9 | 13814_at | At2g29040 |

| Unknown protein | 254 | 5.8 | 15277_at | At2g41440 |

| Glu-rich protein | 238 | 22.1 | 16656_at | At4g20160 |

| Putative protein | 227 | 18.3 | 15322_at | At4g24580 |

| Unknown protein | 221 | 7.6 | 19849_at | At2g18080 |

| Unknown protein | 219 | 4.3 | 14496_at | At2g45610 |

| Hypothetical protein | 155 | 4.7 | 14379_at | At2g33320 |

| Unknown protein | 128 | 2.6 | 18454_g_at | At4g08605 |

| Unknown protein | 75 | 1.9 | 15016_at | At1g04090 |

| Putative protein | 51 | 2.1 | 12076_at | At4g36600 |

| Hypothetical protein | 49 | 2.3 | 15266_at | At4g08630 |

| Hypothetical protein | 45 | 3.5 | 15262_at | At2g33190 |

| Putative protein, (BRCA1-associated RING domain protein, H. sapiens) | 32 | 1.4 | 17790_g_at | At4g21070 |

Cytoskeleton

A fundamental aspect of tip growth of pollen tubes is the continuous deposition of new cell wall and plasma membrane at the tube apex. Vesicles delivering this material are transported by the actin cytoskeleton. In addition to components of the cytoskeleton in pollen tubes, which have been described as such, i.e. the actin genes ACT4/12 (Huang et al., 1996) and profilin PRF4 (Kandasamy et al., 2002), we have identified a previously uncategorized actin-depolymerizing factor-like protein (At4g25590). Furthermore, three potential motor proteins are selectively expressed. The myosins AtVIIID and AtXID might function in cargo movement along actin filaments (Reddy and Day, 2001), whereas the kinesin-related protein At1g09170 might be involved in movement along microtubules. The already described members of the myosin family, MYA1 to -3 (Kinkema et al., 1994), are not pollen selectively expressed but are pollen-enriched (supplemental Table I). We confirmed that profilin PRF3 (At4g29340) is highly expressed in pollen grains but is otherwise only called Present in roots, which is in disagreement with its reported constitutive, strong expression in all vegetative tissues (Kandasamy et al., 2002).

Vesicle Trafficking

Exo- and endocytosis are required to release the contents of the transported vesicles and to reincorporate excess membrane material. The syntaxin AtSYP124 (At1g61290) and a homolog of the yeast Sec7p protein (At2g30690) fall into the large group of genes presumably involved in vesicle trafficking. Other potential SNAREs that might be required for vesicle fusion in pollen are encoded by the pollenenriched genes AtBET12 (At4g14450) and AtVAMP725 (At2g32670). The clathrin family protein At1g05020 is selectively expressed, and a clathrin assembly protein (At1g03050), which is highly enriched in pollen, might have endocytic functions. Furthermore, two putative ARF GTPases (At2g35210 and At2g14490) are selectively expressed.

Cell Wall Biosynthesis and Regulation

The pollen tube wall is a bipartite structure with an inner sheath of 1,3-β-glucan (callose) covered by an outer fibrillar layer of 1,4-β-glucan (cellulose) and α-linked pectic polysaccharides. Recently, NaCslD1 and NaGsl1 were identified as pollen-expressed genes, potentially encoding the major β-glucan polysaccharide synthases in Nicotiana alata pollen tubes (Doblin et al., 2001). Here, we show that AtCslD4 (putative cellulose synthase; At4g38190) and AtGsl2 (callose synthase; At2g13675) are selectively expressed homologs in Arabidopsis pollen, as assumed in that study. However, AtCslD1 (At2g33100) is also selectively expressed in pollen, and it shows a higher expression than AtCslD4.

Arabidopsis pollen grains express a whole range of cell wall hydrolytic and cell wall-loosening enzymes such as polygalacturonases, pectate lyases, pectin esterases, glycosyl hydrolases, and expansins. The genes encoding these proteins are among those with the highest expression levels in pollen grains in our study, e.g. the putative polygalacturonase At3g07820. Besides their putative roles in modifications of the pollen tube wall, they may be important for the penetration of the stigmatic tissue.

Glycosylphospatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins are targeted to the cell surface and presumably are involved in remodeling of the extracellular matrix and/or in signaling (Borner et al., 2002). The putative GPI-anchored COBL11 (At4g27110), a member of the recently described COBRA family (Roudier et al., 2002), is selectively expressed in pollen in our study. COBRA is implicated in the regulation of oriented cell expansion in the root (Schindelman et al., 2001), and we propose that COBL11 might fulfill a similar function in pollen tubes. Two other putatively GPI-anchored proteins identified in this study are the arabinogalactan proteins AGP6 (At5g14380) and AGP23 (At3g57690), with the highest expression values of the selectively expressed and the pollen-enriched genes, respectively. Although the exact function of AGPs in pollen tubes and styles remains to be determined, it is interesting that AGP23 encodes an AG-peptide (Schultz et al., 2002) of only 61 amino acids length. If cleaved and thus released from its lipid anchor, it might serve as a diffusible signal molecule.

Ion Dynamics

Besides calcium fluxes, several studies indicate the involvement of polarized internal gradients and/or external fluxes of protons, potassium, and chloride in pollen tube growth (for review, see Hepler et al., 2001). However, channels and transporters accounting for the observed ion fluxes across the plasma membrane in pollen tubes remain largely unknown. Thus, the identification of ion transporters that are selectively expressed or enriched in pollen could open new avenues (Feijó et al., 2001). The important role of the selectively expressed, inwardly rectifying K+ channel SPIK (At2g25600) for pollen tube development and competitive ability has been shown by Mouline et al. (2002) and the pollen enriched, outwardly rectifying K+ channel SKOR (At3g02850) has been characterized extensively in root stelar tissues (Gaymard et al., 1998; Lacombe et al., 2000). Interestingly, SKOR is permeable to both monovalent cations and Ca2+ and decreasing cytoplasmic pH reduces SKOR-mediated currents. The selectively expressed, putative cyclic-nucleotide-gated ion channel AtCNGC16 (At3g48010) could be involved in the control of [Ca2+]cyt, too, because it has been shown that an increase in cytoplasmic cAMP or cGMP elicits both a Ca2+ influx and a rise in [Ca2+]cyt in plant cells (Kurosaki et al., 1994; Volotovski et al., 1998). Furthermore, an overlap of the cyclic nucleotide-binding domain and a calmodulin-binding site in AtCNGC1 and -2 (Kohler and Neuhaus, 2000) suggests a regulation of the channels by cyclic nucleotides and calmodulin. Because it has been demonstrated that cAMP can modulate pollen tube growth and reorientation (Moutinho et al., 2001), AtCNGC16 could constitute a possible link between increases in cAMP concentrations and increases in [Ca2+]cyt in pollen tubes.

The putative cation/H+ antiporters AtCHX8, -13, and -16 (At2g28180, At2g13620, and At2g30240) are possible regulators of proton fluxes observed during pollen tube growth (Feijó et al., 1999), although their specificity and membrane localization are still to be determined (Maser et al., 2001). In addition, the identification of a pollen selectively expressed G subunit of the vacuolar type H+-ATPase underlines the possible importance of V-ATPases for proton homeostasis in growing pollen tubes. Recently, Cl– fluxes have been shown to play a role in growth and cell volume regulation in pollen tubes (Zonia et al., 2002). The chloride channel CLC-c (At5g49890) is pollen enriched, and its function in cation homeostasis has been demonstrated by suppression of the Gef1 mutant phenotype in yeast (Gaxiola et al., 1998). Thus, CLC-c might fulfill a similar function in pollen. Furthermore, we identified two tonoplast intrinsic proteins (TIPs), TIP5;1 (At3g47440) and TIP1;3 (At4g01470), as selectively expressed in pollen.

Signal Transduction

Inhibitor studies with pollen of several plant species (for review, see Mascarenhas, 1975) indicate that pollen germination and early tube growth are largely independent of transcription, but strictly dependent on translation. Thus, signal transduction and translational control might play a more important role than transcriptional control. In fact, 25% of the selectively expressed genes fall under the signal transduction category. Most of these genes (26 of 37) encode putative protein kinases. In addition to the Arabidopsis receptor-like kinase RKF1 (At1g29750; Takahashi et al., 1998), the Leu-rich repeat receptor-like kinases LePRK1-3 and ZmPRK1 were characterized as examples of pollen-specific receptor kinases possibly involved in these signaling events (Muschietti et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2002). Here, we show that the Arabidopsis homologs AtPRKc (At2g07040) and AtPRKd (At5g35390) are not only expressed in pollen, but that their expression is restricted to pollen. For RKF2 (At1g19090), which was reportedly expressed at low levels in several organs (Takahashi et al., 1998), we found that it was selectively expressed in pollen. Moreover, we identify the putative Pro-rich, extensin-like receptor kinases AtPERK5, -7, -12, and -4 (At4g34440, At1g49270, At1g23540, and At2g18470) as selectively expressed and pollen enriched, respectively. PERK1 is a canola (Brassica napus) homolog of this novel family of plant receptor-like kinases and is rapidly induced by wounding (Silva and Goring, 2002). Sequence similarities of its extracellular domain to extensins might indicate an involvement of the Arabidopsis pollen homologs in a signal transduction pathway, signaling changes in the mechanical properties of the pollen tube cell wall to target proteins in the pollen cytoplasm.

Potential ligands to pollen receptor kinases might be expressed by the pistil or by the pollen itself as shown for LePRK2 and its pollen-expressed ligand LAT52 (Tang et al., 2002). The potential signaling peptide RALF-LIKE 10 (At2g19020; Olsen et al., 2002) is selectively expressed in pollen. Its tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) homolog rapid alkalinization factor (RALF) encodes a ubiquitous 115-amino acid prepro-protein, which is processed into a 5-kD signaling peptide (Pearce et al., 2001). RALF causes a rapid alkalinization of tobacco cell cultures and an arrest of root growth and development when supplied to germinating tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) and Arabidopsis seeds. RALF-LIKE 10, encoding a 73-amino acid protein with a potential N-terminal signal peptide for export, might be a putative ligand, e.g. for Leu-rich receptor-like kinases in the plasma membrane of pollen or the pistil. The importance of intracellular signaling for pollen tube growth has been demonstrated by studies covering several types of molecular switches, e.g. Rop/Rac GTPases (Gu et al., 2003) and the MAP kinase kinase kinase AtMAP3Kγ (Jouannic et al., 1999). We confirm the pollen-enriched expression of the Rho-related GTPases At-Rac1 (At2g17800) and AtRac6 (At4g35950) and of AtMAP3Kγ (At5g66850), as well as the pollen-enriched expression of the G-protein AtRAB2 (At4g17170; Moore et al., 1997). The Rho-related GTPase Rop1At (At3g51300), reported to be specifically expressed in anthers (Li et al., 1998), is highly enriched in pollen but was called Present in roots and siliques. Moreover, our study enlarges this list significantly, including several putative protein kinases, a putative STE20/PAK-like protein kinase (MAP4K-At1g70430), and two putative G-proteins (At2g33870 and At2g22290). Considering the established link between elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ at the pollen tube tip and its growth (for review, see Franklin-Tong, 1999) our identification of two selectively expressed putative calmodulins (At4g03290 and At4g12860) and the five calcium-dependent protein kinases CPK14, -18, -20, -24, and -26 (At2g41860, At4g36070, At2g38910, At2g31500, and At2g31500) points out six new potential players in Ca2+-mediated signaling in Arabidopsis pollen. In addition, several genes presumably involved in phosphoinositide signaling are selectively expressed in pollen (At2g18180, At2g43900, At2g31830, and At2g41210).

Translational and Transcriptional Regulation

Although only two genes encoding potential regulators of translation were selectively expressed (At3g16380 and At2g39820), there are several more potential regulators of translation showing an enriched expression in pollen (supplemental Table I). Protein turnover in pollen might also contribute to regulation, and therefore the five genes involved in proteolysis are notable. Three percent of the genes that are selectively expressed encode proteins potentially involved in transcriptional regulation. Among these are transcription factor MYB97 (At4g26930) and the MADS-box proteins AGL29 and AGL30 (At2g34440 and At2g03060). AGL30 is a homolog of MADS1;11 of tobacco, which is thought to be a regulator of gene expression during early pollen tube growth (Steiner et al., 2003). Several more potential transcription factors are pollen enriched, including the response regulator ARR2 (At4g16110), as described previously (Lohrmann et al., 2001). The expression of several genes encoding transcription factors in hydrated pollen grains is surprising, because it might indicate that more de novo synthesis of RNA takes place in germinating pollen and during tube growth than had been anticipated by early inhibitor studies (for review, see Mascarenhas, 1975).

Cell Cycle

The cell cycle in the vegetative cell of pollen is believed to be arrested. However the sperm cells continue through the S phase of the cell cycle after pollination and are deposited into the embryo sac with a 2C content of DNA in G2 (Friedman, 1999). According to our results, cyclin A2;1 (At5g25380) is selectively expressed, and cyclin B3;1 (At1g16330) is enriched in pollen with an additional Present call only in roots. Both genes were described recently as showing a peak of expression in M phase of the cell cycle in synchronized cell suspensions of Arabidopsis (Menges et al., 2002). Interestingly, the mitotic cyclin gene CycA1;1 of maize was found to be expressed in isolated sperm and zygotes, although sperm of maize remain in G1 until fertilization (Sauter et al., 1998). We cannot exclude that the cyclin transcripts we have detected are derived from expression in the sperm cells, but whatever their origin, their expression in pollen might be important for fertilization or post-fertilization events rather than for pollen tube growth.

Stress Response

Stress response-related genes, such as the small heat shock protein gene At-HSP17.6A (At5g12030), represent 7% of the pollen selectively expressed genes. The expression of At-HSP17.6A was shown to be induced by heat and osmotic stress (Sun et al., 2001). Thus, the expression of this gene could be explained by osmotic stress during dessication and rehydration of the pollen grain, or the flowcytometric sorting might have caused the induction of stress response-related genes.

Hypothetical proteins and proteins with unknown function account for 23% of the 150 selectively expressed genes. The high expression levels for some of them indicate their potential importance for the male gametophyte. Furthermore, our data confirm the expression of 10 genes that had hypothetical status so far (i.e. no representation in EST databases existing), which makes them interesting candidates for a functional characterization of their encoded gene products.

One-Third of Constitutively Expressed Genes in Vegetative Tissues Are Not Expressed in Pollen

Our main goal was to identify enriched or selectively expressed genes in pollen to gain insight into the genetic basis of pollen germination and tube growth, but identifying genes that are specifically down-regulated in pollen is also informative. For this purpose, we used a list of constitutively expressed genes from samples from 5-week-old Arabidopsis (leaves, roots, inflorescence stems, and flowers; Zhu et al., 2001). Comparing the analysis of Zhu et al. (2001) with our data yielded 283 genes that showed constitutive expression in vegetative tissues in our study as well. We used the lower confidence bound 1.2 criterion and MAS 5 calls to identify those of the 283 genes that were down-regulated or called Absent in pollen with high confidence, resulting in a list of 104 genes, which were functionally characterized (Table II; supplemental Table II). Thus, 37% of 283 genes constitutively expressed in vegetative tissues are not expressed in pollen grains. The largest set (27%) of transcripts is functionally related to protein biosynthesis; all of the 29 genes in this category encode putative or known ribosomal proteins. Labeling experiments of lily and Tradescantia sp. pollen tubes indicated transcriptional inactivation of rRNA genes in immature pollen grains and during pollen tube growth (for review, see Mascarenhas, 1975), and our data is in accordance with these early observations. This supports the view that in many species, the majority of rRNAs and ribosomal proteins as well as tRNAs, mRNAs, and other proteins are already stored in the mature pollen grain to ensure rapid germination and initial tube growth on the stigma (Mascarenhas, 1989). Thus, in most cases, the transcript abundance that we have measured in Arabidopsis pollen grains most likely reflects the accumulation and storage of transcripts during earlier stages of pollen development.

Table II.

Functional classification of constitutively expressed genes not expressed in pollen

Of the 283 genes identified as constitutively expressed in the vegetative tissues, 104 are called Absent in pollen. These 104 genes are classified based on established as well as putative functions. For each functional category, the number of genes is given in brackets, and each gene is given by its TAIR locus identifier (if no locus is associated, only the Affymetrix probe set is given. Genes in each category were ranked by highest negative fold change (see Supplemental Table II for more details).

| Protein biosynthesis (29) |

| At2g34480, At1g43170, At4g11050, At2g09990, At4g27090, At1g34030, At1g67430, At1g09690, At1g70600, At2g39460, At4g34670, At2g19730, At4g16720, At3g49010, At2g25210, At3g52580, At1g27400, At4g14320, At2g18020, At3g47370, At4g00100, At2g36160, At1g72370, At2g19750, At4g26230, At2g33370, At2g40510, At2g31610, At4g18730 |

| Metabolism (28) |

| At2g25450, At1g04410, At3g61440, At2g26670, At4g21960, At5g35630, At2g28000, At5g43940, At2g30860, At2g31570, At3g58610, At4g23860, At5g04590, At2g30490, At1g70310, (12881_s_at), At1g53240, At1g50480, At2g13360, At4g09320, At5g39950, At2g30870, At2g43090, At5g60920, (20709_s_at), At1g65960, At1g75330, At2g36580 |

| Water channel (8) |

| At2g37170, At3g53420, At3g26520, At3g61430, At4g35100, At2g45960, At4g23400, At2g36830 |

| Signal transduction (6) |

| At5g10450, At2g42590, At5g55190, At5g42080, At1g02130, At5g38480 |

| Stress response (5) |

| At1g47128, At4g24190, At1g20620, At1g20440, At2g02130 |

| Transcriptional regulation (5) |

| At3g16770, At2g32080, At4g40060, At2g33340, (18032_i_at) |

| Translational regulation (4) |

| At3g04730, At1g30230, At1g09640, At2g22670 |

| Others |

| At2g27020, At1g13060, At4g26840 (proteolysis); At5g49720, At4g19410 (cell wall biosynthesis and regulation); At3g06720, At2g14720 (protein transport); At4g30270 (senescence); At5g12250 (cytoskeleton); At1g04400 (phototropism); At5g40890 (ion transport) |

| Unknown (8) |

| At2g41430, At3g15353, (12847_at), At1g13930, At4g36040, At2g35810, At4g16520, At1g14910 |

The next largest set (26%) of transcripts encodes proteins involved in diverse functions related to metabolism. Surprisingly, the third largest group (8%) consists of genes encoding membrane intrinsic proteins. Besides two TIPs (TIP1;1 and TIP1;2), six of these encode plasma membrane intrinsic proteins (PIPs; PIP1;1, PIP1;2, PIP1;5, PIP2;1, PIP2;2, and PIP2; 7). This observation prompted us to study the expression levels and calls of the remaining seven annotated Arabidopsis PIPs (Johanson et al., 2001). Probe sets for five of these genes (PIP1;3, PIP1;4, PIP2;5, PIP2;6, and PIP2;8) were found on the version of the Arabidopsis array used in this study. Taking all our available data about PIPs together, we identified PIP1;3 (At1g01620) as the only PIP expressed in pollen. It has been assumed that water fluxes might be linked to the flux of Cl– (Zonia et al., 2001). Plant major intrinsic proteins have been reported to be enriched in zones of fast cell division and expansion or in areas where water flow or solute flux density would be expected to be high (for review, see Johanson et al., 2001; Tyerman et al., 2002). Our data indicate the sole expression of PIP1;3 (old name TMP-B) in pollen, although 13 PIPs are annotated in the Arabidopsis genome. Interestingly, it has been shown that PIP1;3 expression is turgor responsive (Shagan et al., 1993). The selectively expressed TIPs, TIP1;3 and TIP5;1, might be involved in cytosolic osmoregulation, too. The subcellular localizations indicated by the TIP and PIP labels should be taken as putative (Barkla et al., 1999) because they are solely based on sequence data in most cases.

CONCLUSIONS

We have identified transcripts of 1,584 genes in Arabidopsis pollen, of which 30% are pollen enriched and 10% pollen selectively expressed. Thus, our study significantly increases the current knowledge of genes expressed in the male gametophyte of Arabidopsis. The specific down-regulation of otherwise constitutively expressed genes emphasizes that a particular genetic program underlies the unique growth of pollen tubes. T-DNA insertion lines are available for the majority of the 150 genes selectively expressed in pollen, and their characterization might support the ongoing efforts to combine genetic and physiological evidence into a model for pollen germination and pollen tube growth. We show here that pollen possesses a significantly lower amount of expressed genes compared with other vegetative tissue and yet retains remarkable self-organized regulatory mechanisms of growth. This makes pollen an excellent model for the study of cell growth and morphogenesis on apical growing cells because it seems to be using a “minimal” set of genes encoding a mechanism with obvious evolutionary success.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis ecotype Col-0 was used in this study. To minimize interplant variability, tissues from a minimum of 12 plants were pooled for each RNA extraction. For seedling and root, seeds were surface-sterilized and then spread on petri dishes containing B-5 medium (Duchefa, Haarlem, The Netherlands) solidified with 0.8% (w/v) phytagar (Duchefa). The seeds were cold-treated for 3 d at 4°C to ensure uniform germination. The plates were transferred to short-day conditions (8 h of light at 21°C–23°C) and grown in a horizontal (for harvest of seedlings) or vertical position (for harvest of roots). For the seedling samples more than 25 seedlings from five petri dishes were collected after 4 d of growth. For the root samples more than 25 roots from 10 petri dishes were harvested after 13 d.

Plants for the leaf, silique, and pollen samples were grown on soil for 12 weeks in short-day conditions (8 h of light at 21°C–23°C) and then changed to long-day conditions (16 h of light) to induce flowering. After bolting, more than 12 rosette leaves from different plants per leaf sample were collected. Young siliques were harvested 2 weeks later. Old parts of the flower, especially stamens, were removed from the siliques to ensure pollen-free silique samples, and more than 25 siliques from different plants were pooled per sample.

Isolation and FACS Sorting of Pollen Grains

A detailed protocol of the purification of hydrated pollen grains can be found in the supplemental “Materials and Methods”. In brief, flower heads were cut and placed in a humid chamber for 2 h. Then the flower heads were agitated three times in 500 mL of pollen-sorting buffer (10 mm CaCl2, 1 mm KCl, 2 mm MES, and 5% [w/v] Suc, pH 6.5 with NaOH, in double-distilled water). After consecutive filtration and centrifugation steps, the resulting pellet, highly enriched in pollen, was re-suspended in 10 mL of pollen-sorting buffer. Hydrated pollen grains were separated from non-hydrated and/or destroyed pollen grains and other impurities in a final purification step using FACS based on size and autofluorescence criteria of pollen. Pollen viability was assessed by enzymatically induced fluorescence using fluorescein diacetate according to Heslop-Harrison and Heslop-Harrison (1970).

RNA Isolation, Target Synthesis, and Hybridization to Affymetrix GeneChips

Total RNA was extracted from the tissue and cell samples, respectively, using the RNeasy Mini Plant Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA quality was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry. RNA was processed for use on Affymetrix Arabidopsis Genome GeneChip arrays, according to the manufacturer's protocol. In brief, 7 μg of total RNA was used in a reverse transcription reaction (SuperScript II, Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) to generate first-strand cDNA. After second-strand synthesis, double-strand cDNA was used in an in vitro transcription reaction to generate biotinylated cRNA. After purification and fragmentation, 15 μg of cRNA was used in a 300-μL hybridization containing added hybridization controls. Two hundred microliters of mixture was hybridized on arrays for 16 h at 45°C. Standard post hybridization wash and double-stain protocols were used on an Affymetrix GeneChip Fluidics Station 400. Arrays were scanned on an Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 2500.

Data Analysis

Scanned arrays were analyzed first with Affymetrix MAS 5.0 software to obtain Absent/Present calls and to assure that all quality parameters were in the recommended range. For subsequent analysis, dChip 1.3 (http://www.dchip.org; Wong laboratory, Harvard) was used. The following conditions were applied to ensure reliability of the analyses (for details, see supplemental “Materials and Methods”): First, each GeneChip experiment was performed with biological replicates and triplicates in the case of pollen, respectively. Second, we used a sample-wise normalization to the median median probe cell (CEL) intensity of all arrays. Third, normalized CEL intensities of the 11 arrays were used to obtain model-based gene expression indices based on a Perfect Match-only model (Li and Hung Wong, 2001). Finally, all genes compared were considered to be differentially expressed if they were called Present in at least one of the arrays and if the 90% lower confidence bound of the -fold change between experiment and baseline was above 1.2.

To achieve a higher stringency for the identification of constitutively expressed genes in the vegetative tissues, we combined our data with a set identified by Zhu et al. (2001). Because a proprietary pre-version of the Arabidopsis Genome GeneChip array was used by these authors, 81 of the 346 probe sets they identified as constitutively expressed were not included in our study, resulting in an overlap of 283 probe sets.

Gene Annotation

For gene annotation, we used the updated TAIR (The Arabidopsis Information Resource) annotation (October 2002 release) for the Arabidopsis Genome GeneChip array (http://www.arabidopsis.org). Genes were classified into functional categories using the Gene Ontology information available from TAIR as of October 2002. Genes represented by two or more probe sets on the array were analyzed manually, and only the most significant probe set for this gene was included in the final tables.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Philip Benfey (New York University [now at Duke University, Durham, NC]) for initial support and critical reading of the manuscript, Pedro Coutinho (Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência) for his help to update the gene annotation, and Sheila McCormick (Plant Gene Expression Center, Albany, CA) for critical reading of the manuscript.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.103.028241.

This work was supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT; project nos. POCTI/BCI/41725/2001, POCTI/BIA/34772/1999, and POCTI/BCI/46453/2002). J.D.B. and L.C.B. were supported by FCT fellowships SFRH/BPD/3619/2000 and SFRH/BD/1128/2000.

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

References

- Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (2000) Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408: 796–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkla BJ, Vera-Estrella R, Pantoja O, Kirch HH, Bohnert HJ (1999) Aquaporin localization: how valid are the TIP and PIP labels? Trends Plant Sci 4: 86–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borner GH, Sherrier DJ, Stevens TJ, Arkin IT, Dupree P (2002) Prediction of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins in Arabidopsis: a genomic analysis. Plant Physiol 129: 486–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che P, Gingerich DJ, Lall S, Howell SH (2002) Global and hormone-induced gene expression changes during shoot development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 14: 2771–2785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derksen J, Knuiman B, Hoedemaekers K, Guyon A, Bonhomme S, Pierson ES (2002) Growth and cellular organization of Arabidopsis pollen tubes in vitro. Sex Plant Reprod 15: 133–139 [Google Scholar]

- Doblin MS, De Melis L, Newbigin E, Bacic A, Read SM (2001) Pollen tubes of Nicotiana alata express two genes from different β-glucan synthase families. Plant Physiol 125: 2040–2052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D (1998) Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 14863–14868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan LM, Wang YF, Wang H, Wu WH (2001) In vitro Arabidopsis pollen germination and characterization of the inward potassium currents in Arabidopsis pollen grain protoplasts. J Exp Bot 52: 1603–1614 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feijó JA, Sainhas J, Hackett GR, Kunkel JG, Hepler PK (1999) Growing pollen tubes possess a constitutive alkaline band in the clear zone and a growth-dependent acidic tip. J Cell Biol 144: 483–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feijó JA, Sainhas J, Holdaway-Clarke T, Cordeiro MS, Kunkel JG, Hepler PK (2001) Cellular oscillations and the regulation of growth: the pollen tube paradigm. Bioessays 23: 86–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin-Tong VE (1999) Signaling and modulation of pollen tube growth. Plant Cell 11: 727–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman WE (1999) Expression of the cell cycle in sperm of Arabidopsis: implications for understanding patterns of gametogenesis and fertilization in plants and other eukaryotes. Development 126: 1065–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaxiola RA, Yuan DS, Klausner RD, Fink GR (1998) The yeast CLC chloride channel functions in cation homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 4046–4050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaymard F, Pilot G, Lacombe B, Bouchez D, Bruneau D, Boucherez J, Michaux-Ferriere N, Thibaud JB, Sentenac H (1998) Identification and disruption of a plant shaker-like outward channel involved in K+ release into the xylem sap. Cell 94: 647–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub TR, Slonim DK, Tamayo P, Huard C, Gaasenbeek M, Mesirov JP, Coller H, Loh ML, Downing JR, Caligiuri MA et al. (1999) Molecular classification of cancer: class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science 286: 531–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Vernoud V, Fu Y, Yang Z (2003) ROP GTPase regulation of pollen tube growth through the dynamics of tip-localized F-actin. J Exp Bot 54: 93–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon VN, Astwood JD, Garner EC, Dunker AK, Taylor LP (2000) Isolation and characterization of cDNAs expressed in the early stages of flavonol-induced pollen germination in petunia. Plant Physiol 123: 699–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer SL, Hogenesch JB, Straume M, Chang HS, Han B, Zhu T, Wang X, Kreps JA, Kay SA (2000) Orchestrated transcription of key pathways in Arabidopsis by the circadian clock. Science 290: 2110–2113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler PK, Vidali L, Cheung AY (2001) Polarized cell growth in higher plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 17: 159–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslop-Harrison J, Heslop-Harrison Y (1970) Evaluation of pollen viability by enzymatically induced fluorescence; intracellular hydrolysis of fluorescein diacetate. Stain Technol 45: 115–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SR, An YQ, McDowell JM, McKinney EC, Meagher RB (1996) The Arabidopsis thaliana ACT4/ACT12 actin gene subclass is strongly expressed throughout pollen development. Plant J 10: 189–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson U, Karlsson M, Johansson I, Gustavsson S, Sjovall S, Fraysse L, Weig AR, Kjellbom P (2001) The complete set of genes encoding major intrinsic proteins in Arabidopsis provides a framework for a new nomenclature for major intrinsic proteins in plants. Plant Physiol 126: 1358–1369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouannic S, Hamal A, Leprince AS, Tregear JW, Kreis M, Henry Y (1999) Characterisation of novel plant genes encoding MEKK/STE11 and RAF-related protein kinases. Gene 229: 171–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandasamy MK, McKinney EC, Meagher RB (2002) Plant profilin isovariants are distinctly regulated in vegetative and reproductive tissues. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 52: 22–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HU, Cotter R, Johnson S, Senda M, Dodds P, Kulikauska R, Tang W, Ezcura I, Herzmark P, McCormick S (2002) New pollen-specific receptor kinases identified in tomato, maize and Arabidopsis: The tomato kinases show overlapping but distinct localization patterns on pollen tubes. Plant Mol Biol 50: 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinkema M, Wang HY, Schiefelbein J (1994) Molecular analysis of the myosin gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 26: 1139–1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler C, Neuhaus G (2000) Characterisation of calmodulin binding to cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels from Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett 471: 133–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki F, Kaburaki H, Nishi A (1994) Involvement of plasma membranelocated calmodulin in the response decay of cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel of cultured carrot cells. FEBS Lett 340: 193–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacombe B, Pilot G, Gaymard F, Sentenac H, Thibaud JB (2000) pH control of the plant outwardly-rectifying potassium channel SKOR. FEBS Lett 466: 351–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon KA, Lord EM (2000) In vivo pollen tube cell of Arabidopsis thaliana: I. Tube cell cytoplasm and wall. Protoplasma 214: 45–56 [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Hung Wong W (2001) Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: model validation, design issues and standard error application. Genome Biol 2: RESEARCH0032.1–0032.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Wu G, Ware D, Davis KR, Yang Z (1998) Arabidopsis Rho-related GTPases: differential gene expression in pollen and polar localization in fission yeast. Plant Physiol 118: 407–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohrmann J, Sweere U, Zabaleta E, Baurle I, Keitel C, Kozma-Bognar L, Brennicke A, Schafer E, Kudla J, Harter K (2001) The response regulator ARR2: a pollen-specific transcription factor involved in the expression of nuclear genes for components of mitochondrial complex I in Arabidopsis. Mol Genet Genomics 265: 2–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord EM, Russell SD (2002) The mechanisms of pollination and fertilization in plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 18: 81–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas JP (1975) The biochemistry of angiosperm pollen development. Bot Rev 41: 259–314 [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas JP (1989) The male gametophyte of flowering plants. Plant Cell 1: 657–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maser P, Thomine S, Schroeder JI, Ward JM, Hirschi K, Sze H, Talke IN, Amtmann A, Maathuis FJ, Sanders D et al. (2001) Phylogenetic relationships within cation transporter families of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 126: 1646–1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick S (1993) Male gametophyte development. Plant Cell 5: 1265–1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menges M, Hennig L, Gruissem W, Murray JA (2002) Cell cycle regulated gene expression in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem 277: 41987–42002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore I, Diefenthal T, Zarsky V, Schell J, Palme K (1997) A homolog of the mammalian GTPase Rab2 is present in Arabidopsis and is expressed predominantly in pollen grains and seedlings. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 762–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouline K, Very AA, Gaymard F, Boucherez J, Pilot G, Devic M, Bouchez D, Thibaud JB, Sentenac H (2002) Pollen tube development and competitive ability are impaired by disruption of a Shaker K(+) channel in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 16: 339–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moutinho A, Hussey PJ, Trewavas AJ, Malho R (2001) cAMP acts as a second messenger in pollen tube growth and reorientation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 10481–10486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muschietti J, Eyal Y, McCormick S (1998) Pollen tube localization implies a role in pollen-pistil interactions for the tomato receptor-like protein kinases LePRK1 and LePRK2. Plant Cell 10: 319–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen AN, Mundy J, Skriver K (2002) Peptomics, identification of novel cationic Arabidopsis peptides with conserved sequence motifs. In Silico Biol 2: 0039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce G, Moura DS, Stratmann J, Ryan CA Jr (2001) RALF, a 5-kDa ubiquitous polypeptide in plants, arrests root growth and development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 12843–12847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson S, Simonsen V, Loeschcke V (1987) Overlap of gametophytic and sporophytic gene expression in barley. Theor Appl Genet 75: 200–206 [Google Scholar]

- Preuss D (1995) Being fruitful: genetics of reproduction in Arabidopsis. Trends Genet 11: 147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy AS, Day IS (2001) Analysis of the myosins encoded in the recently completed Arabidopsis thaliana genome sequence. Genome Biol 2: RESEARCH0024.1–0024.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roudier F, Schindelman G, DeSalle R, Benfey PN (2002) The COBRA family of putative GPI-anchored proteins in Arabidopsis: a new fellowship in expansion. Plant Physiol 130: 538–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter M, von Wiegen P, Lorz H, Kranz E (1998) Cell cycle regulatory genes from maize are differentially controlled during fertilization and first embryonic cell division. Sex Plant Reprod 11: 41–48 [Google Scholar]

- Schindelman G, Morikami A, Jung J, Baskin TI, Carpita NC, Derbyshire P, McCann MC, Benfey PN (2001) COBRA encodes a putative GPI-anchored protein, which is polarly localized and necessary for oriented cell expansion in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 15: 1115–1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz CJ, Rumsewicz MP, Johnson KL, Jones BJ, Gaspar YM, Bacic A (2002) Using genomic resources to guide research directions: the arabinogalactan protein gene family as a test case. Plant Physiol 129: 1448–1463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott R, Hodge R, Paul W, Draper J (1991) The molecular biology of anther differentiation. Plant Sci 80: 167–191 [Google Scholar]

- Shagan T, Meraro D, Bar-Zvi D (1993) Nucleotide sequence of an Arabidopsis thaliana turgor-responsive TMP-B cDNA clone encoding transmembrane protein with a major intrinsic protein motif. Plant Physiol 102: 689–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva NF, Goring DR (2002) The proline-rich, extensin-like receptor kinase-1 (PERK1) gene is rapidly induced by wounding. Plant Mol Biol 50: 667–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner C, Bauer J, Amrhein N, Bucher M (2003) Two novel genes are differentially expressed during early germination of the male gametophyte of Nicotiana tabacum. Biochim Biophys Acta 1625: 123–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson JR, Eisenberg AJ, Willing RP, Pe ME, Hanson DD, Mascarenhas JP (1987) Genes expressed in the male gametophyte of flowering plants and their isolation. Plant Physiol 83: 442–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Bernard C, Van de Cotte B, Van Montagu M, Verbruggen N (2001) At-HSP17.6A, encoding a small heat-shock protein in Arabidopsis, can enhance osmotolerance upon overexpression. Plant J 27: 407–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Mu JH, Gasch A, Chua NH (1998) Identification by PCR of receptor-like protein kinases from Arabidopsis flowers. Plant Mol Biol 37: 587–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Ezcurra I, Muschietti J, McCormick S (2002) A cysteine-rich extracellular protein, LAT52, interacts with the extracellular domain of the pollen receptor kinase LePRK2. Plant Cell 14: 2277–2287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor LP, Hepler PK (1997) Pollen germination and tube growth. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 48: 461–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twell D (2002) The developmental biology of pollen. In JA Roberts, ed, Plant Reproduction, Vol 6. Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield, UK, pp 86–153 [Google Scholar]

- Tyerman SD, Niemietz CM, Bramley H (2002) Plant aquaporins: multifunctional water and solute channels with expanding roles. Plant Cell Environ 25: 173–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volotovski ID, Sokolovsky SG, Molchan OV, Knight MR (1998) Second messengers mediate increases in cytosolic calcium in tobacco protoplasts. Plant Physiol 117: 1023–1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willing RP, Bashe D, Mascarenhas JP (1988) An analysis of the quantity and diversity of messenger RNAs from pollen and shoots of Zea mays. Theor Appl Genet 75: 751–753 [Google Scholar]

- Wixon J (2001) Arabidopsis thaliana. Comp Funct Genom 2: 91–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T, Budworth P, Han B, Brown D, Chang HS, Zou GZ, Wang X (2001) Toward elucidating the global gene expression patterns of developing Arabidopsis: parallel analysis of 8,300 genes by a high-density oligonucleotide probe array. Plant Physiol Biochem 39: 221–242 [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T, Wang X (2000) Large-scale profiling of the Arabidopsis transcriptome. Plant Physiol 124: 1472–1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonia L, Cordeiro S, Feijó JA (2001) Ion dynamics and hydrodynamics in the regulation of pollen tube growth. Sex Plant Reprod 14: 111–116 [Google Scholar]

- Zonia L, Cordeiro S, Tupy J, Feijó JA (2002) Oscillatory chloride efflux at the pollen tube apex has a role in growth and cell volume regulation and is targeted by inositol 3,4,5,6-tetrakisphosphate. Plant Cell 14: 2233–2249 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.