Abstract

Context: Increased production of antiangiogenic factors soluble endoglin (sEng) and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-1 (sFlt-1) by the placenta contributes to the pathophysiology in preeclampsia (PE).

Objective: Our objective was to determine the differences in endoglin (Eng), fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-1 (Flt-1), and placental growth factor (PlGF) expressions between normal and PE placentas and sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF production by trophoblast cells (TC) cultured under lowered oxygen conditions.

Methods: TCs isolated from normal and PE placentas were cultured under regular (5% CO2/air) and lowered (2% O2/5% CO2/93% N2) oxygen conditions. sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF productions were determined by ELISA. Protein expressions for Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF in the placental tissues were accessed by immunohistochemical staining and Western blot analysis. Deglycosylated Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF protein expressions in placental tissues were also examined.

Results: PE TCs produced significantly more sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF compared with those from normal TCs (P < 0.05). Under lowered oxygen conditions, PE TCs, but not normal TCs, released more sEng and sFlt-1. In contrast, both normal and PE TCs released less PlGF (P < 0.05). Enhanced expressions of Eng and Flt-1, as well as glycosylated Eng and Flt-1, were observed in PE placentas. Immunoblot also revealed that TCs released glycosylated sFlt-1, but not sEng, in culture.

Conclusions: PE TCs produce more sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF than normal TCs. Lowered oxygen conditions promote sEng and sFlt-1, but reduce PlGF, productions by PE TCs. More glycosylated sEng and sFlt-1 are present in PE placentas. Trophoblasts release glycosylated sFlt-1, but unglycosylated sEng, in culture.

Preeclampsia is a maternal hypertensive disorder with unknown etiology. Under lowered oxygen condition, trophoblasts from preeclamptic placentas released more soluble anti-angiogenic factors endoglin (sEng) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (sFlt-1), but less angiogenic factor placental growth factor (PlGF). Glycosylated Eng and Flt-1 were detected in preeclamptic placentas.

Preeclampsia (PE) is a maternal hypertensive disorder with unknown etiology during human pregnancy. Recent studies by Levine et al. (1,2) revealed significantly higher maternal circulating levels of soluble vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor-1 or soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-1 (sFlt-1) and soluble endoglin (sEng) in women complicated by PE than in women with normal pregnancies. In contrast, maternal circulating levels of free placental growth factor (PlGF) are significantly lower in women with PE. The elevated sFlt-1 and sEng levels were found to increase for several weeks in pregnant women who subsequently developed PE during their pregnancy. These findings indicate that increased maternal levels of sFlt-1 and sEng can be detectable in pregnant women before the onset of PE (1,2). Enhanced fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-1 (Flt-1) expression was found in the placental tissues from PE (3). A study by Maynard et al. (3) showed that administration of sFlt-1 adenovirus to pregnant rats could induce hypertension and glomerular endotheliosis, which mimics the maternal symptoms and pathological changes in the kidney in patients with PE. A subsequent study from the same group further noticed that endoglin (Eng), a cell surface receptor for TGFβ1, exerts a similar biological effect as sFlt-1 and may contribute to the pathogenesis in this pregnancy disorder (4).

Both sFlt-1 and sEng have antiangiogenic effects, and are considered endogenous antiangiogenic factors in humans. sFlt-1 binds to VEGF and PlGF (5), and blocks their angiogenic actions to vascular tissues. Eng is expressed in vascular endothelial cells and placental trophoblasts. Its function may be involved in vascular activity and homeostasis (6). sEng could impair binding of TGFβ1 to its receptor on cell surface, thus leading to dysregulation of TGFβ1 signaling with effects on activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and vasodilation. PlGF belongs to the VEGF family and plays an important role in enhancing VEGF-driven angiogenesis. In contrast, loss of PlGF impairs angiogenesis, wound healing, and inflammatory responses (7,8).

Placentas produce sFlt-1, sEng, and PlGF. Excess amounts of sFlt-1 and sEng derived from the placenta may offset VEGF, PlGF, and TGFβ1 bioactivities, impair maternal vascular endothelial function, and induce glomerular endotheliosis in PE (3,4). The harmful effects produced by sEng and sFlt-1 are believed to be a major component in the pathogenesis of PE (1,2,3). Although it is considered that the placenta trophoblasts might be the major source of sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF during pregnancy and abnormal placental function may lead to an increase in sFlt-1 and sEng releases during PE, trophoblast productions of sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF in normal and preeclamptic placentas have never been simultaneously studied; neither have hypoxic effects on trophoblast sEng production. To investigate this we isolated trophoblasts from placentas delivered by normal and preeclamptic pregnant women. Isolated trophoblasts were cultured under regular (21% O2) and lowered (2% O2) oxygen conditions. Productions of sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF were determined. We further examined Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF expressions by immunostaining of villous tissue sections and by Western blot analysis. Protein samples were also treated with glycosidase to determine whether glycosylated proteins for sEng, sFlt-1, or PlGF were present in the placenta.

Patients and Methods

Patient information

A total of 30 placentas, 16 from normal and 14 from PE, was used in this study. Normal pregnancy is defined as a pregnancy in which the mother had normal blood pressure (≤ 140/90 mm Hg) with the absence of medical and obstetrical complications. The definition for PE follows the guideline of National Institutes of Health publication No. 00-3029 (9). PE is defined as maternal systolic blood pressure higher than or equal to 140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure higher than or equal to 90 mm Hg on two occasions, separated by 6 h, and proteinuria more than 300 mg in a 24-h period after 20-wk gestation. PE is considered severe if one or more of the following criteria is present: maternal blood pressure higher than or equal to 160/110 mm Hg on two separate readings at least 6 h apart; proteinuria more than 2+ by dipstick or more than 2 g/24 h; visual disturbances; pulmonary edema; epigastric or right upper quadrant pain; impaired liver function; thrombocytopenia; or fetal growth restriction. This study was performed at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in Shreveport and approved by the institutional review board for Human Research at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in Shreveport, LA. In the PE group, all placentas were from pregnant women who were clinically diagnosed with severe PE. None of the study subjects had signs of infection. Smokers were excluded.

Trophoblast cell isolation and culture

Trophoblast cells were isolated from freshly delivered placentas as previously described (10,11). Briefly, dissected villous tissue excluding chorionic and basal plates was digested with Dispase (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Becton Dickinson, Bedford, MA). Isolated trophoblast cells were purified by Percoll density gradient (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) centrifugation. Percoll gradients were made from 45–15% Percoll (vol/vol) in 5% steps of 5.0 ml each. Trophoblasts were recovered in the density of the gradient between 1.048 and 1.062 g/ml. To eliminate contaminated red blood cells, isolated trophoblasts were incubated with lysis buffer containing 155 mm NH4Cl, 10 mm KHCO3, and 0.14 mm EDTA (pH 7.2) on ice for 3–5 min. Cell viability was examined by trypan blue exclusion. The viability of the cells was over 95%.

Isolated trophoblast cells were placed in six-well plates with a density of 5 × 106 cells per well in 4 ml DMEM (Sigma Chemical Inc., St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum. Two plates were prepared from each trophoblast isolation as previously described (11,12). After overnight culture under regular culture conditions (5% CO2 in air; 21% O2) to equilibrate the cultures, one plate was continued in the regular culture condition, and one plate was placed in a portable air chamber (Billups-Rothenberg, Del Mar, CA) for lowered oxygen culture, in which the chamber was filled with mixed air of 2% O2, 5% CO2 balanced with 93% N2. The chamber was flushed daily with the mixed air for 2 min at 10 liter/min. The “lowered O2” condition represents a range of ambient O2 of 2% ± 0.01. The chamber was housed in an incubator to maintain 37 C temperature. All cells were cultured in duplicate for 48 h. At the end of incubation, culture medium was collected and centrifuged. The supernatant was used for measuring sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF. Trophoblast cells were lysed with sodium hydroxide, and total cellular protein concentration per well was measured by Bio-Rad Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). BSA was used to generate a standard curve. The protein concentration was used to calculate sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF productions. Data are expressed as per microgram protein.

ELISA measurements for sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF

Trophoblast productions of sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF were measured by ELISA. The ELISA kits for sEng (CD105), sFlt-1, and PlGF were purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). The range of standard curve for sEng was 15.6–4000 pg/ml. The range of standard curve for sFlt-1 was 31.2–2000 pg/ml. The range of standard curve for PlGF was 15.6–1000 pg/ml. Plates were read at 450 nm by an autoplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). For each assay, all samples were assayed in duplicate in the same plate. Within-assay variation was less than 5% for each assay.

Immunohistochemical staining

Fresh villous tissues were fixed with 10% formalin. Tissue sections (4 μm) were stained with monoclonal antihuman Eng (CD105), Flt-1, and PlGF. Antibody for CD105 (BD33551A2) was purchased from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA), Flt-1 from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA), and PlGF from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (San Diego, CA). Biotinylated secondary antibodies and ABC staining systems from Santa Cruz Biotechnology were used following the manufacturer’s instructions. Stained slides were counterstained with Gill’s formulation hematoxylin. Tissue sections stained with secondary antibody only were used as a negative control. For each target staining, all slides (seven normal and five PE) were processed at the same time. Stained tissue slides were reviewed by Olympus microscopy (Olympus IX71; Olympus America, Inc., Melville, NY), and images were captured by a digital camera and recorded into a microscopy linked personal computer. Immunohistochemical staining studies were mainly used for detecting localization of target molecules in the placental villous tissue.

Protein expression

Snap-frozen tissues were homogenized, and placental tissue protein expressions for Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF were determined by Western blot analysis. Briefly, total tissue protein 50 μg each sample was subject for electrophoresis (Mini-cell protein-3 gel running system; Bio-Rad) and then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were probed with a primary mAb against Eng, Flt-1, PlGF, or polyclonal antibody actin (Sigma-Aldrich). The bound antibodies were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescent detection kit (Amersham Corp., Arlington Heights, IL). Nitrocellulose membranes were stripped and blocked before they were probed with a different antibody.

Protein deglycosylation

Deglycosylation was performed using N-glycosidase F. Briefly, an aliquot of 100 μg total protein per sample was incubated with 1.0 U N-glycosidase F (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) at 37 C for 48 h. One unit glycosidase catalyzes the release of N-linked oligosaccharides from 1.0 nmol denatured ribonuclease B per minute at 37 C (pH 7.5). Cleavaged protein was monitored by SDS-PAGE and probed with antibody against Eng, Flt-1, or PlGF.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± se. The Student t test or paired t test was used for statistical analysis by StatView computer software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A probability level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Trophoblast cell productions of sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF

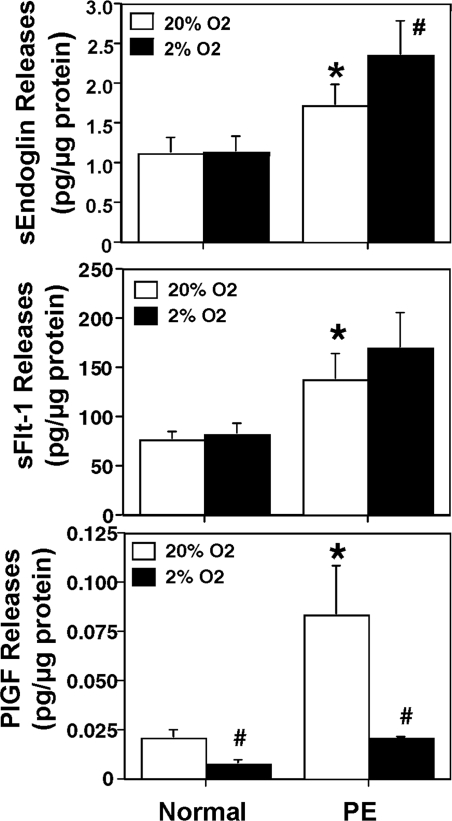

The productions of sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF by trophoblasts that were cultured under 21% O2 and 2% O2 conditions are shown in Fig. 1. Under the 21% O2 culture condition, trophoblast cells from preeclamptic placentas produced significantly more sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF than trophoblast cells from normal placentas: sEng 1.726 ± 0.272 vs. 1.123 ± 0.194 pg/μg protein, P < 0.05; sFlt-1 138 ± 26 vs. 77 ± 9 pg/μg protein, P < 0.05; and PlGF 0.084 ± 0.025 vs. 0.021 ± 0.004 pg/μg protein, P < 0.05, respectively. There were no differences for sEng and sFlt-1 production by normal trophoblast cells cultured between 21% O2 and 2% O2 conditions: sEng 1.123 ± 0.194 vs. 1.139 ± 0.194 pg/μg; and sFlt-1 77 ± 9 vs. 62 ± 12 pg/μg. In contrast, trophoblast cells from preeclamptic placentas produced more sEng when they were cultured under 2% O2 compared with 21% O2 (2.359 ± 0.434 vs. 1.726 ± 0.272 pg/μg; P < 0.05). Although sFlt-1 productions were increased by preeclamptic trophoblast cells when they were cultured with 2% O2, the value was not statistically significant (170 ± 36 vs. 138 ± 26 pg/μg; P = 0.315). For PlGF, trophoblasts from both normal and preeclamptic placentas produced significantly less PlGF when cultured under 2% O2 condition: normal 0.008 ± 0.002 vs. 0.021 ± 0.004; and PE 0.021 ± 0.001 vs. 0.084 ± 0.025 pg/μg, P < 0.05, respectively.

Figure 1.

sEng (top panel), sFlt-1 (middle panel), and PlGF (bottom panel) productions by placental trophoblasts. Trophoblasts from normal (n = 7) and PE (n = 7) placentas were cultured under regular (21%) or lowered (2%) O2 conditions over 48 h. Trophoblasts from PE placentas produced more sEng, sFlt, and PlGF when cultured under regular O2 condition. *, P < 0.05, PE vs. normal under 21% O2. #, P < 0.05, Two percent O2 vs. 21% O2.

Immunostaining of Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF

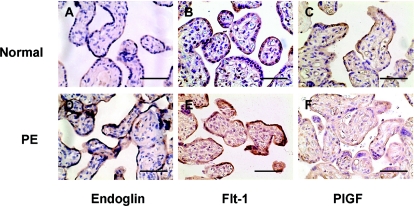

Tissue sections from 12 placentas (seven normal and five PE) were immunostained for Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF. Our results showed that: 1) positive staining for Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF was mainly localized in the syncytiotrophoblast layer; and 2) enhanced staining for Eng and Flt-1, but reduced staining for PlGF, was observed in preeclamptic tissue sections compared with normal tissue sections. Examples of immunostaining results from one normal and one preeclamptic placenta are shown in Fig. 2 (A and D, Eng; B and E, Flt-1; and C and F, PlGF). Both placentas were delivered at 38 wk.

Figure 2.

Representative immunostaining of Eng (A and D), Flt-1 (B and E), and PlGF (C and F) in normal (A–C) and PE (D–F) placental tissue sections. Bar, 20 μm.

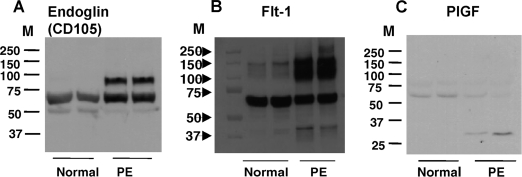

Placental tissue protein expressions for Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF

Placental tissue protein expressions for Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF are shown in Fig. 3. Total protein samples were run on SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Our results showed different patterns for Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF expressions between normal and preeclamptic placentas. Eng and Flt-1 protein expressions were up-regulated in preeclamptic tissue samples, whereas PlGF protein expressions were down-regulated in preeclamptic tissue samples. For Eng expression (Fig. 3A), there are two major bands in the preeclamptic samples with one approximate molecular mass of 65 kD and one approximate of 90 kD, whereas, only a 65-kD band is shown in the normal samples. For Flt-1 expression (Fig. 3B), an intense band with an approximate molecular mass of 65–72 kD is shown in both normal and preeclamptic samples, whereas in preeclamptic tissues, there are intense and diffused bands with molecular masses of 100–150 kD and a band with a lower molecular mass of approximately 40–45 kD. In contrast, a week band with an approximate molecular mass of 140–150 kD is shown in the normal tissue samples. For PlGF expression (Fig. 3C), one band shows up with an approximate molecular mass of 55 kD in normal and PE placental tissue samples. Whereas in the PE samples, an additional lower band with a molecular mass of approximately 28 kD is observed.

Figure 3.

Placental tissue expressions for Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF by Western blot analyses. Placental tissues were homogenized, and total tissue proteins were run on SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Protein expressions for Eng (A) and Flt-1 (B) were up-regulated in preeclamptic tissue samples compared with normal tissue samples. In contrast, protein expression for PlGF (C) was down-regulated in preeclamptic tissue samples. The patterns of total tissue protein expressions for Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF are remarkably different between normal and preeclamptic placentas. M, Protein marker.

sEng and sFlt-1 expression

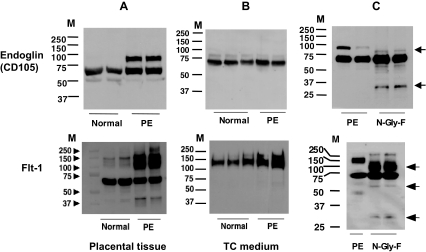

Because of the different patterns of Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF protein expressions detected between normal and preeclamptic placental tissues (Fig. 3), we further determined the molecular mass of sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF released by trophoblast cells. Trophoblast culture media were run on SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. An aliquot of 10 μg protein per medium sample was loaded per lane. As shown in Fig. 4, only the 65-kD band was detected for Eng in both normal and preeclamptic trophoblast culture media (Fig. 4B, upper panel), compared with the tissue protein expressions (Fig. 4A, upper panel). These results suggest that the 65-kD molecular mass is probably sEng. For Flt-1 expression, a diffused band with a molecular mass of 110–150 kD is shown in both normal and preeclamptic trophoblast medium samples, but the diffused band is more intense in the preeclamptic trophoblast medium samples (Fig. 4B, lower panel). The medium Flt-1 expression pattern suggests that the molecular mass of approximately 110–150 kD is probably sFlt-1. Medium PlGF protein expression was undetectable by Western blot (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Eng and Flt-1 expressions in placental tissues, trophoblast culture medium, and placental tissues after being treated with N-glycosidase (N-Gly-F). Upper panels, Eng expression. Lower panels, Flt-1 expression. A, Tissue expression. B, Trophoblast culture medium expression. C, Preeclamptic placental tissues treated with or without N-glycosidase for 48 h. Compared with tissue expression, only a single band with approximately 65 kD for Eng and diffused bands with approximately 110–150 kD are shown in the cell culture medium. After N-glycosidase treatment, the higher molecular mass bands for Eng at 90 kD and Flt-1 at approximately 140–150 kD disappeared, which suggests that glycosylated Eng and Flt-1 are present in the preeclamptic placental tissue, and trophoblasts are more likely able to release glycosylated sFlt-1, but not Eng, in culture. M, Protein marker.

Glycosylated Eng and Flt-1 expressions

Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF have putative N-glycosylation sites, which may account for the different molecular masses of their protein size revealed by the Western blot (Fig. 3). Glycosylations are known to occur in different cell compartments, including cell membrane, cytoplasm, and nucleus. To explore further whether glycosylated Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF are present in the placental tissue, an aliquot of total tissue protein from two preeclamptic placentas was digested with N-glycosidase F, and then deglycosylated samples and undeglycosylated controls were separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and probed with Eng, Flt-1, or PlGF antibody, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4C (upper panel) for Eng expression, after glycosidase digestion the 90-kD band disappeared, and two new bands show up, one at approximately 75–78 kD, and one at approximately 28 kD. These results imply that the 90-kD molecular mass is probably a glycosylated form for Eng, and more glycosylated Eng is present in placental tissues from PE (Fig. 4A, upper panel). However, it seems that the putative sEng (∼65 kD) released by trophoblasts is unglycosylated (Fig. 4B, upper panel). For Flt-1 expression, after glycosidase digestion, three new bands show up: one around 90–120 kD, one at approximately 55 kD, and one at approximately 28 kD (Fig. 4C, lower panel). These results suggest that dominant glycosylated sFlt-1 is probably present in the preeclamptic placental tissue (Fig. 4A, lower panel). In contrast to Eng, trophoblasts are more likely able to release glycosylated sFlt-1 (Fig. 4B, lower panel). No band was detected when the blots were probed with antibody against PlGF (data not shown).

Discussion

In this study we determined sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF productions by trophoblasts from normal and preeclamptic placentas. We found that placental trophoblasts from preeclamptic pregnancies produced significantly more sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF than normal trophoblasts when cells were incubated under regular culture condition (20% O2). We further noticed increased sEng and sFlt-1 productions by preeclamptic trophoblasts, but not by normal trophoblasts, when they were cultured under lowered oxygen condition (2% O2). PlGF production was significantly reduced by trophoblasts from both normal and preeclamptic placentas when they were cultured under lowered oxygen condition. The different productions of sEng, sFlt-1, and PlGF by normal and preeclamptic trophoblasts cultured under regular and lowered oxygen conditions suggest that:

1. Trophoblast cells from normal placentas might be able to compensate or be more resistant to lowered oxygen stimulation than the cells from preeclamptic placentas. In other words, the lack of endogenous protective factors such as heme oxygenase-1 (13), as well as antioxidant superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase in trophoblasts may contribute to the increased sEng and sFlt-1 productions by preeclamptic placentas (10,14).

2. Compared with sEng and sFlt-1 productions, PlGF production may be the most sensitive one being affected by lowered oxygen environment.

To determine whether increased Eng and Flt-1 and decreased PlGF immunoreactivities are present in preeclamptic placentas, villous tissue sections were immunostained with antibodies against Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF. Our results showed that positive stainings for Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF were mainly localized in the syncytiotrophoblast layer of the placenta. Compared with normal placentas, tissue sections from preeclamptic placentas showed intense immunostaining of Eng and Flt-1, but reduced immunostaining of PlGF, in the syncytiotrophoblasts of preeclamptic placentas. The Western blot data of increased Eng and Flt-1, but decreased PlGF, expressions in preeclamptic placentas are consistent with the immunostaining observations. These results support the concept that aberrant angiogenic and antiangiogenic factor activities occur in preeclamptic placentas. One discrepancy we observed in this study is the result of a relatively more PlGF production in preeclamptic trophoblasts than in normal trophoblasts when cultured under 21% O2 condition in contrast to reduced PlGF immunostaining in the villous tissue from preeclamptic placentas. The reason for this discrepancy in PlGF production between cultured trophoblasts and tissue expression from preeclamptic placentas is not known. However, a similar phenomenon had been observed for vasodilator prostacyclin production (15), in which more prostacyclin was produced by isolated trophoblasts from preeclamptic than trophoblasts from normal placentas. In contrast, whole villous tissue from preeclamptic placentas produced less prostacyclin than that from normal placentas (16). It is possible that the loss of tissue integrity control in isolated trophoblasts might account for the dissociated phenomenon in PlGF production by trophoblasts and its expression in whole villous tissue.

Both Flt-1 and Eng genes contain hypoxia-inducible factor-1 binding sites. In the present study, we did not examine the signaling pathway regulation of Eng and Flt-1 in trophoblasts because previous published work demonstrated that hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression was increased in cells cultured under lowered oxygen condition (17), a key regulator of up-regulation of Flt-1 and Eng expression.

One of the most significant findings of the present study is the different pattern of total tissue protein expressions for Eng, Flt-1, and PlGF between normal and preeclamptic placentas. Eng is a type I integral membrane protein with a molecular size of approximately 68 kD (18). Our Western blot data revealed two bands for Eng, one at approximately 65 kD and one at 90 kD, which are consistent with the results reported by Venkatesha et al. (4), which show that Eng protein exists as a 90-kD “full length” and a 65-kD soluble form in the preeclamptic placenta when the samples were determined by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Soluble and truncated forms of human Eng are present as a disulfide-linked dimer (19). Mature and monomer sFlt-1 is an approximate 70-kD protein (20). The higher molecular mass bands of Eng and Flt-1 in preeclamptic tissue samples revealed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3) implicate that Eng and Flt-1 may very likely exist as dimer, polymer, and/or complex formation, especially in the preeclamptic placentas. By examining medium protein expression, we confirmed that sEng released by trophoblasts is a 65-kD protein under reducing conditions. These results agree with the results reported by Raab et al. (19). In contrast, sFlt-1 released by trophoblasts may exist as a dimer or a complex form. The latter one may include glycosylated sFlt-1 or ligand/receptor complex formed by binding of VEGF/PlGF to Flt-1 or sFlt-1. This notion is supported by our Western blot data shown in Fig. 4, and the ligand binding and receptor dimerization study of Flt-1 by Barleon et al. (20). The mature PlGF is about 28–32 kD and usually exists in a homodimeric structure (5). It seems that PlGF is present either as monomer or dimer in preeclamptic placentas, whereas only dimerized PlGF is present in the normal placental tissue.

Another important finding of the present study is that more glycosylated Eng and Flt-1 are present in the preeclamptic placentas (Fig. 4). Studies have shown that the extracellular peptide sequence for Flt-1 has 11 putative glycosylation sites (20), and Eng has four putative glycosylation sites (18). Theoretically, PlGF has four putative glycosylation sites (5). Unfortunately, we were unable to detect glycosylated PlGF in preeclamptic placentas. It is well known that a glycosylated protein has different physical and biochemical properties from its deglycosylated format (21). A glycosylated or deglycosylated protein may lead to functional diversities. For example, deglycosylated human chorionic gonadotropin interacts with a different domain of the receptor compared with its native hormone (22). Glycoprotein could attribute to the heterogeneity of its constitute oligosaccharides (23). In the present study, glycosylated protein may account for the broadened bands observed for sFlt-1 expression in preeclamptic placental tissues detected by Western blot analysis. The ubiquity of glycosylation is well established, and it is quite common with secreted proteins. In blood serum, almost all proteins are glycosylated (21). Interestingly, by examining sEng and sFlt-1 expressions in the trophoblast culture medium, we found that placental trophoblasts produce/release glycosylated sFlt-1, but unglycosylated sEng, in vitro. It seems that trophoblast cells from preeclamptic placentas produce more glycosylated sFlt-1 than that from normal placentas. At the present time, we do not know whether our in vitro observations reflect the changes that might occur in vivo in PE, and what the properties are between the glycosylated sFlt-1 and sEng from their deglycosylated ones. Further study of their functional differences may provide insight regarding their antiangiogenic actions and their role in PE.

Footnotes

This study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD36822), and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL65997).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

First Published Online October 23, 2007

Abbreviations: Eng, Endoglin; Flt-1, fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-1; PE, preeclampsia; PlGF, placental growth factor; sEng, soluble endoglin; sFlt-1, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-1; TC, trophoblast cells; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

References

- Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, Schisterman EF, Thadhani R, Sachs BP, Epstein FH, Sibai BM, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA 2004 Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med 350:672–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, Yu KF, Maynard SE, Sachs BP, Sibai BM, Epstein FH, Romero R, Thadhani R, Karumanchi SA, CPEP Study Group 2006 Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N Engl J Med [Erratum (2006) 355:1840] 355:992–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, Lim KH, Li J, Mondal S, Libermann TA, Morgan JP, Sellke FW, Stillman IE, Epstein FH, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA 2003 Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest 111:649–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesha S, Toporsian M, Lam C, Hanai J, Mammoto T, Kim YM, Bdolah Y, Lim KH, Yuan HT, Libermann TA, Stillman IE, Roberts D, D’Amore PA, Epstein FH, Sellke FW, Romero R, Sukhatme VP, Letarte M, Karumanchi SA 2006 Soluble endoglin contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Nat Med 12:642–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JE, Chen HH, Winer J, Houck KA, Ferrara N 1994 Placenta growth factor. Potentiation of vascular endothelial growth factor bioactivity, in vitro and in vivo, and high affinity binding to Flt-1 but not to Flk-1/KDR. J Biol Chem 269:25646–25654 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toporsian M, Gros R, Kabir MG, Vera S, Govindaraju K, Eidelman DH, Husain M, Letarte M 2005 A role for endoglin in coupling eNOS activity and regulating vascular tone revealed in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Circ Res 96:684–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autiero M, Waltenberger J, Communi D, Kranz A, Moons L, Lambrechts D, Kroll J, Plaisance S, De Mol M, Bono F, Kliche S, Fellbrich G, Ballmer-Hofer K, Maglione D, Mayr-Beyrle U, Dewerchin M, Dombrowski S, Stanimirovic D, Van Hummelen P, Dehio C, Hicklin DJ, Persico G, Herbert JM, Communi D, Shibuya M, Collen D, Conway EM, Carmeliet P 2003 Role of PlGF in the intra- and intermolecular cross talk between the VEGF receptors Flt1 and Flk1. Nat Med 9:936–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy JA, Dvorak AM, Dvorak HF 2003 VEGF-A(164/165) and PlGF: roles in angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Trends Cardiovasc Med 13:169–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National High Blood Pressure Education Program 2000 Working group report on high blood pressure in pregnancy. National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. National High Blood Pressure Education Program. NIH Publication no. 00-3029. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Walsh SW 2001 Increased superoxide generation is associated with decreased superoxide dismutase activity and mRNA expression in placental trophoblast cells in preeclampsia. Placenta 22:206–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Gu B, Zhang Y, Lewis DF, Wang Y 2005 Hypoxia-induced increase in soluble Flt-1 production correlates with enhanced oxidative stress in trophoblast cells from the human placenta. Placenta 25:210–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen RS, Zhang Y, Gu Y, Lewis DF, Wang Y 2005 Increased phospholipase A2 and thromboxane but not prostacyclin production by placental trophoblast cells from normal and preeclamptic pregnancies cultured under hypoxia condition. Placenta 26:402–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudmore M, Ahmad S, Al-Ani B, Fujisawa T, Coxall H, Chudasama K, Devey LR, Wigmore SJ, Abbas A, Hewett PW AA 2007 Negative regulation of soluble Flt-1 and soluble endoglin release by heme oxygenase-1. Circulation 115:1789–1797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Walsh SW 1996 Antioxidant activities and mRNA expression of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase in normal and preeclamptic placentas. J Soc Gynecol Investig 3:179–184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SW, Wang Y 1995 Trophoblast and placental villous core production of lipid peroxides, thromboxane, and prostacyclin in preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80:1888–1893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SW, Behr MJ, Allen NH 1985 Placental prostacyclin production in normal and toxemic pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 151:110–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakumar A, Doty K, Daftary A, Harger G, Conrad KP 2003 Impaired oxygen-dependent reduction of HIF-1α and -2α proteins in pre-eclamptic placentae. Placenta [Erratum (2003) 24:711] 24:199–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gougos A, Letarte M 1990 Primary structure of endoglin, an RGD-containing glycoprotein of human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 265:8361–8364 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raab U, Velasco B, Lastres P, Letamendia A, Cales C, Langa C, Tapia E, Lopez-Bote JP, Paez E, Bernabeu C 1999 Expression of normal and truncated forms of human endoglin. Biochem J 339:579–588 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barleon B, Totzke F, Herzog C, Blanke S, Kremmer E, Siemeister G, Marme D, Martiny-Baron G 1997 Mapping of the sites for ligand binding and receptor dimerization at the extracellular domain of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor FLT-1. J Biol Chem 272:10382–10388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lis H, Sharon N 1993 Protein glycosylation. Structural and functional aspects. Eur J Biochem 218:1–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji I, Ji TH 1990 Differential interactions of human choriogonadotropin and its antagonistic aglycosylated analog with their receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:4396–4400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall RL, Thomas KA 1993 Inhibition of vascular endothelial cell growth factor activity by an endogenously encoded soluble receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:10705–10709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]