Abstract

Heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) inhibits apoptosis by regulating cellular prooxidant iron. We now show that there is an additional mechanism by which HO-1 inhibits apoptosis, namely by generating the gaseous molecule carbon monoxide (CO). Overexpression of HO-1, or induction of HO-1 expression by heme, protects endothelial cells (ECs) from apoptosis. When HO-1 enzymatic activity is blocked by tin protoporphyrin (SnPPIX) or the action of CO is inhibited by hemoglobin (Hb), HO-1 no longer prevents EC apoptosis while these reagents do not affect the antiapoptotic action of bcl-2. Exposure of ECs to exogenous CO, under inhibition of HO-1 activity by SnPPIX, substitutes HO-1 in preventing EC apoptosis. The mechanism of action of HO-1/CO is dependent on the activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling transduction pathway. Expression of HO-1 or exposure of ECs to exogenous CO enhanced p38 MAPK activation by TNF-α. Specific inhibition of p38 MAPK activation by the pyridinyl imidazol SB203580 or through overexpression of a p38 MAPK dominant negative mutant abrogated the antiapoptotic effect of HO-1. Taken together, these data demonstrate that the antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 in ECs is mediated by CO and more specifically via the activation of p38 MAPK by CO.

Keywords: apoptosis, endothelial cells, heme oxygenase 1, carbon monoxide, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase

Introduction

In their normally quiescent state, endothelial cells (ECs) maintain blood flow, allowing the continuous traffic of plasma and cellular constituents between blood and parenchymal tissues. To accomplish this function, ECs must promote a certain level of vasorelaxation and inhibit leukocyte adhesion as well as coagulation and thrombosis (for a review, see reference 1). However, when ECs are exposed to proinflammatory stimuli, they become “activated” and promote vasoconstriction, leukocyte adhesion, and activation, as well as coagulation and thrombosis (for reviews, see references 1 2 3). These functional changes are due to the expression by activated ECs of a series of proinflammatory genes encoding adhesion molecules, cytokines/chemokines, and costimulatory and procoagulant molecules (for reviews, see references 1 2 3 4). To prevent unfettered EC activation that could lead to EC injury and apoptosis, the expression of these proinflammatory genes must be tightly regulated 5. One of the mechanisms by which this occurs relies on the expression by activated ECs of “protective genes” 6 7 8 9 10. One such gene is the stress responsive gene heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1).

Heme oxygenases are the rate-limiting enzymes in the catabolism of heme into biliverdin, free iron, and carbon monoxide (CO), with biliverdin being subsequently catabolyzed into bilirubin (for reviews, see references 11 12 13). Several proinflammatory stimuli that lead to EC activation also upregulate the expression of HO-1 (for reviews, see references 12 and 13). That HO-1 acts as a cytoprotective gene is suggested by the observation that expression of HO-1 in vitro prevents EC injury mediated by activated polymorphonuclear cells 14, hydrogen peroxide 14 15, or heme 15 16 17. In addition, expression of HO-1 in vivo suppresses a variety of inflammatory responses, including endotoxic shock 17 18 19, hyperoxia 20, acute pleurisy 21, ischemia reperfusion injury 22, and graft rejection 23 24, further supporting the cytoprotective role of this gene.

We have shown previously that expression of HO-1 prevents ECs from undergoing apoptosis 23. This may be an important mechanism by which HO-1 exerts its cytoprotective function, since EC apoptosis, such as it occurs during acute 25 and chronic inflammation 26, is highly deleterious. We now demonstrate that the antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 is mediated through the ability of HO-1 to generate the gaseous molecule CO. In addition, we demonstrate that CO suppresses EC apoptosis through a mechanism that is dependent on the activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signal transduction pathway.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

The murine 2F-2B EC line (American Type Culture Collection) and primary bovine aortic ECs (BAECs) were cultured as described previously 23 27.

Expression Plasmids.

The β-galactosidase was cloned into the pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen) as described previously 28. Two vectors encoding rat HO-1 cDNA were used. The original vector encoding the full-length rat HO-1 cDNA under the control of a the β-actin enhancer/promoter (β-actin/HO-1) has been described elsewhere 29. A 1.0-kbp XhoI-HindIII fragment encoding the full-length rat HO-1 cDNA was cut from the prHO-1 vector 30 and subcloned into the pcDNA3 vector to achieve expression of the HO-1 cDNA under the control of the CMV enhancer/promoter (pcDNA3/HO-1). The mouse Bcl-2 cDNA was cloned in the pac vector, as described elsewhere 10. p38/CSBP1 MAPK was amplified from HeLa cDNA by PCR and cloned into the pcDNA3/HA vector derived from pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) by inserting a DNA fragment coding for an epitope derived from the hemagglutinin protein of the human influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA; MYPYDVPDYASL). A dominant negative mutant of p38/CSBP1, harboring a T180A and a Y182F substitution, was generated by overlap extension mutagenesis. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) cDNA (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.) was cloned into the pcDNA3-expressing vector.

Transient Transfections.

BAECs and 2F-2B ECs were transiently transfected as described elsewhere 23 28. All experiments were carried out 24–48 h after transfection. β-Galactosidase–transfected cells were detected as described elsewhere 23 28. The percentage of viable cells was assessed by evaluating the number of β-galactosidase–expressing cells that retained normal morphology, as described elsewhere 23 28. The number of random fields counted was determined to have a minimum of 200 viable transfected cells per control well. The percentage of viable cells was normalized for each DNA preparation to the number of transfected cells counted in the absence of the apoptosis-inducing agent (100% viability). All experiments were performed at least three times in duplicate.

Adenovirus.

The recombinant HO-1 adenovirus has been described previously 31. The recombinant β-galactosidase adenovirus was a gift of Dr. Robert Gerard (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas). Adenoviruses were produced, extracted, purified, and titrated, as described previously 28. Confluent BAECs were infected with a multiplicity of infection of 200 PFU/cell, as described elsewhere 28.

Cell Extracts and Western Blot Analysis.

Cell extracts were prepared, electrophoresed under denaturing conditions (10–12.5% polyacrylamide gels), and transferred into polyvinyldifluoridine membranes (Immobilon P; Millipore), as described elsewhere 28. HO-1 was detected using a rabbit anti–human HO-1 polyclonal antibody (StressGen Biotechnologies). Vasodilatator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) was detected using a rabbit anti–human VASP polyclonal antibody (Calbiochem-Novabiochem). Total and activated/phosphorylated forms of extracellular signal–regulated kinases (ERK-1 and -2), c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases (JNK-1, -2, and -3), and p38 MAPK were detected using rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against the total or phosphorylated forms of these MAPKs, according to the manufacturer's suggestions (New England Biolabs, Inc.). β-Tubulin was detected using anti–human β-tubulin monoclonal antibody (Boehringer). Primary antibodies were detected using horseradish peroxidase–conjugated donkey anti–rabbit or goat anti–mouse IgG secondary antibodies (Pierce Chemical Co.). Peroxidase was visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence assay (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and stored in the form of photoradiographs (Biomax™ MS; Eastman Kodak Co.). Digital images were obtained using an image scanner (Arcus II; Agfa) equipped with FotoLook and Photoshop® software. The amount of phosphorylated ERK, JNK, and p38 MAPK was quantified using ImageQuant® software (Molecular Dynamics). When indicated, membranes were stripped (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, and 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 30 min, 50°C). Phosphorylated ERK, JNK, and p38 MAPK were normalized to the total amount of total ERK, JNK, and p38 MAPK detected in the same membrane.

Flow Cytometry.

2F-2B ECs were transfected with the GFP expression plasmid and harvested 24 h after transfection by trypsin digestion (0.05% in PBS). ECs were washed in PBS, pH 7.2, 5% FCS, and fluorescent labeling was evaluated using a FACSort™ equipped with CELLQuest™ software (Becton Dickinson).

Cell Treatment and Reagents.

Actinomycin D (Act.D; Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in PBS and added to the culture medium 24 h after transfection. The Act.D concentration used corresponded to the optimal concentration necessary to sensitize ECs to TNF-α–mediated apoptosis, e.g., 10 μg/ml for 2F-2B ECs and 0.1 μg/ml for BAECs. When indicated, EC apoptosis was induced by etoposide (200 μM, 8 h; Calbiochem-Novabiochem) or by serum deprivation (0.1% FCS for 24 h). The iron chelator deferoxamine mesylate (DFO; Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved extemporarily in water and added to culture medium (1–100 μM) 1 h before the induction of apoptosis. Hemoglobin (Hb; Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved (1 mM) extemporarily in PBS, 10 mM Na2S2O4, dialyzed against PBS (2 h, 4°C, 1:800 dilution), and added to the culture medium (1–100 μM) 6 h after transfection. The guanylcyclase inhibitor 1H(1,2,4)oxadiazolo(4,3-α)quinoxalin-1 (ODQ; Calbiochem-Novabiochem) was dissolved in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) and added to the culture medium (10–100 μM) 6 h after transfection. Iron protoporphyrin ([FePP]/heme), cobalt protoporphyrin (CoPPIX), and tin protoporphyrin (SnPPIX; all from Porphyrin Products, Inc.) were dissolved (10 mM) in 100 mM NaOH and conserved at −20°C until use. Metalloporphyrins were added to the culture medium (50 μM) 6 h after transfection. The cGMP analogue 8-bromo-cGMP sodium salt (8-Br-cGMP; Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in water and added to the culture medium (10–100 μM) 30 min before the induction of apoptosis. Human recombinant TNF-α (R&D Systems) was dissolved in PBS and 1% BSA, and added to the culture medium (10–100 ng/ml) 24 h after transfection. The p38 MAPK inhibitor pyridinyl imidazol SB203580 32 was dissolved in DMSO and added to the culture medium (5–20 μM) 6 h after transfection.

CO Exposure.

Cells were exposed to compressed air or varying concentration of CO (250 and 10,000 parts per million [ppm]), as described elsewhere 33.

Results

HO-1 Protects ECs from Apoptosis.

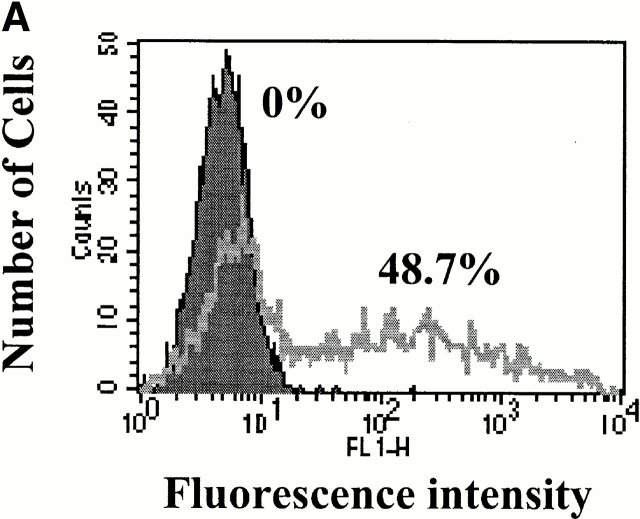

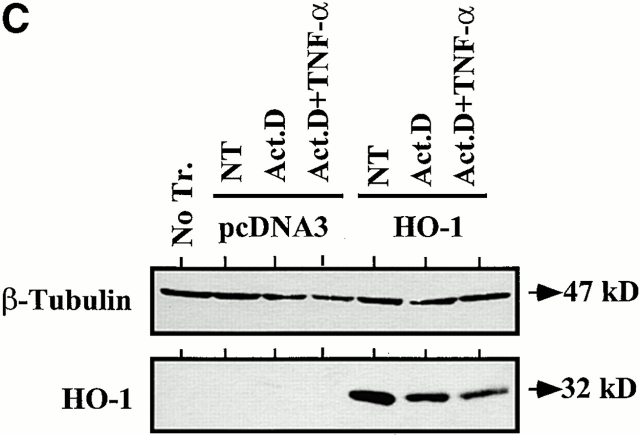

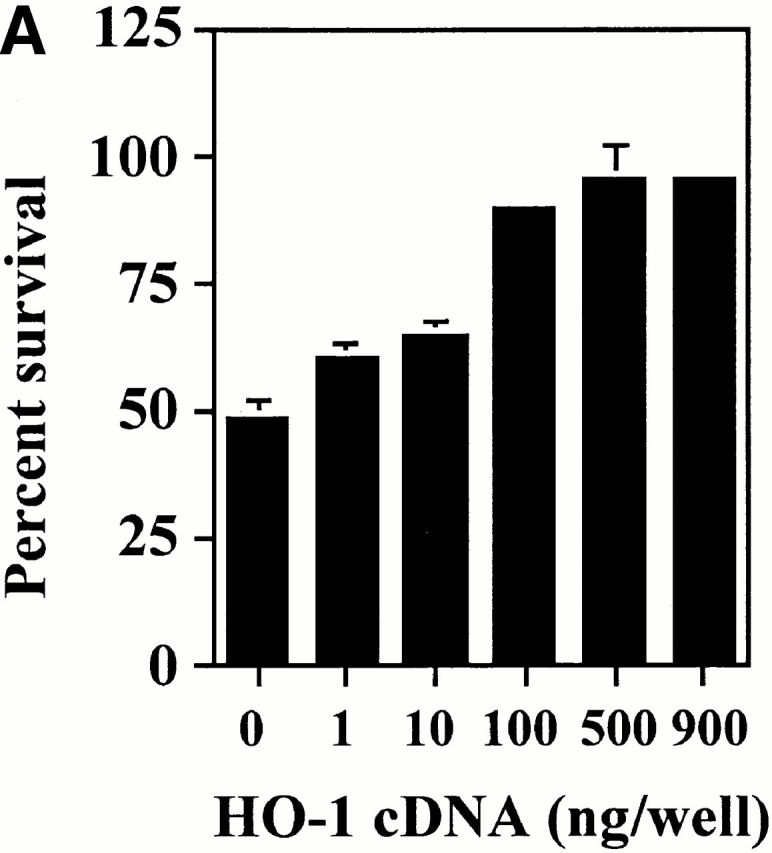

TNF-α induces apoptosis of cultured ECs when transcriptional activity is inhibited by Act.D 28. We have used this experimental system to ask whether transient overexpression of HO-1 could prevent ECs from undergoing apoptosis. We first evaluated the ability of ECs to be transiently transfected. To do so, ECs were transfected with a GFP-expressing plasmid and the percentage of GFP-expressing ECs was evaluated by flow cytometry. As illustrated in Fig. 1, 45% of ECs expressed the GFP protein 24 h after transfection. We then tested whether transfection of HO-1 would prevent ECs from undergoing TNF-α–mediated apoptosis. To do so, ECs were cotransfected with HO-1 and β-galactosidase and apoptosis was evaluated by counting the number of viable β-galactosidase–expressing ECs. TNF-α plus Act.D induced apoptosis of control ECs transfected with the pcDNA3 (60–70% apoptotic ECs). Overexpression of HO-1 prevented EC apoptosis (5–10% apoptotic ECs; Fig. 1). The expression of HO-1 was confirmed by Western blot (Fig. 1). Overexpression of HO-1 also prevented EC apoptosis induced by other proapoptotic stimuli such as etoposide or serum deprivation, which is in keeping with similar observations in 293 cells 34. The antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 was dose dependent in that increasing levels of HO-1 expression resulted in increased protection from TNF-α plus Act.D–mediated apoptosis (Fig. 2). The maximal antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 (90–100% protection) was reached using 500–1,000 ng of the β-actin/HO-1 expression vector per 3 × 105 cells (Fig. 2). All subsequent experiments were carried out using these experimental conditions.

Figure 1.

HO-1 suppresses EC apoptosis. (A) 2F-2B ECs were transfected with a GFP-expressing plasmid and monitored for GFP expression by flow cytometry. The percentage of transfected ECs was assessed by measuring fluorescence intensity in ECs transfected with control (pcDNA3; filled histogram) versus GFP (open histogram) expression plasmids. (B) ECs were cotransfected with β-galactosidase plus control (pcDNA3) or HO-1 (β-actin/HO-1) expression vectors. EC apoptosis was induced by TNF-α plus Act.D and apoptosis of β-galactosidase–transfected ECs was quantified. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. Results shown are the mean ± SD from duplicate wells taken from 1 representative experiment out of 10. (C) HO-1 expression was detected in BAECs by Western blot. No Tr, nontransfected. NT, nontreated. (D) 2F-2B ECs were cotransfected with β-galactosidase plus control (pcDNA3) or HO-1 (β-actin/HO-1) expression vectors. Gray bars represent untreated ECs and black bars represent ECs treated with etoposide (200 μM, 8 h) or subjected to serum deprivation (0.1% FCS for 24 h). Results shown are the mean ± SD from duplicate wells taken from one representative experiment out of three independent experiments. Similar results were obtained using BAECs.

Figure 2.

The antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 is dose dependent. (A) 2F-2B ECs were cotransfected with increasing doses of HO-1 expression vector (β-actin/HO-1). EC apoptosis was induced by TNF-α plus Act.D. Results shown are the mean ± SD from duplicate wells taken from one representative experiment out of three. Similar results were obtained using BAECs. (B) The expression of HO-1 was detected in BAECs by Western blot. Values indicate the amount of HO-1 vector (pcDNA3/HO-1) used in each transfection (ng of DNA per 3 × 105 cells). No Tr., nontransfected.

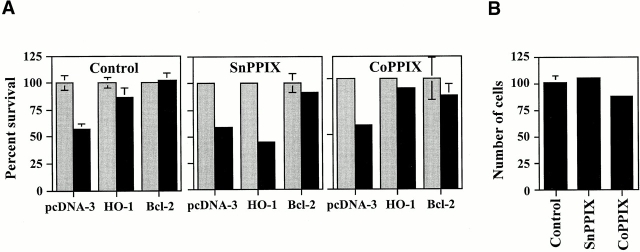

The Antiapoptotic Function of HO-1 Requires Its Enzymatic Activity.

To test whether the antiapoptotic action of HO-1 was dependent on its enzymatic action, HO-1 activity was blocked using SnPPIX. When HO-1 activity was blocked by SnPPIX, HO-1 was no longer able to prevent EC apoptosis (Fig. 3), and the antiapoptotic effect of bcl-2 was not impaired by SnPPIX (Fig. 3). CoPPIX, which has a similar structure to SnPPIX but does not inhibit HO activity, did not suppress the antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 or that of bcl-2 (Fig. 3). These protoporphyrins had no detectable effect per se on EC viability (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 is dependent on HO enzymatic activity. (A) 2F-2B ECs were cotransfected with β-galactosidase plus pcDNA3, HO-1 (β-actin/HO-1), or bcl-2 expression vectors. Cells were either left untreated (Control) or treated with the inhibitor of HO enzymatic activity SnPPIX. CoPPIX, a protoporphyrin that does not inhibit HO enzymatic activity, was used as a control treatment. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. Results shown are the mean ± SD from duplicate wells taken from one representative experiment out of three. (B) 2F-2B ECs were transfected with β-galactosidase plus pcDNA3 expression vectors. ECs were either left untreated (Control) or were treated with SnPPIX and CoPPIX as in A. The results shown are the mean ± SD from duplicate wells taken from one representative experiment out of three.

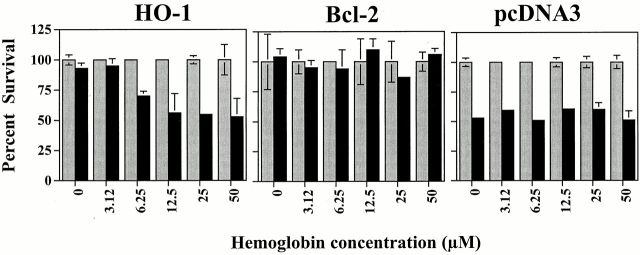

Endogenous CO Mediates the Antiapoptotic Effect of HO-1.

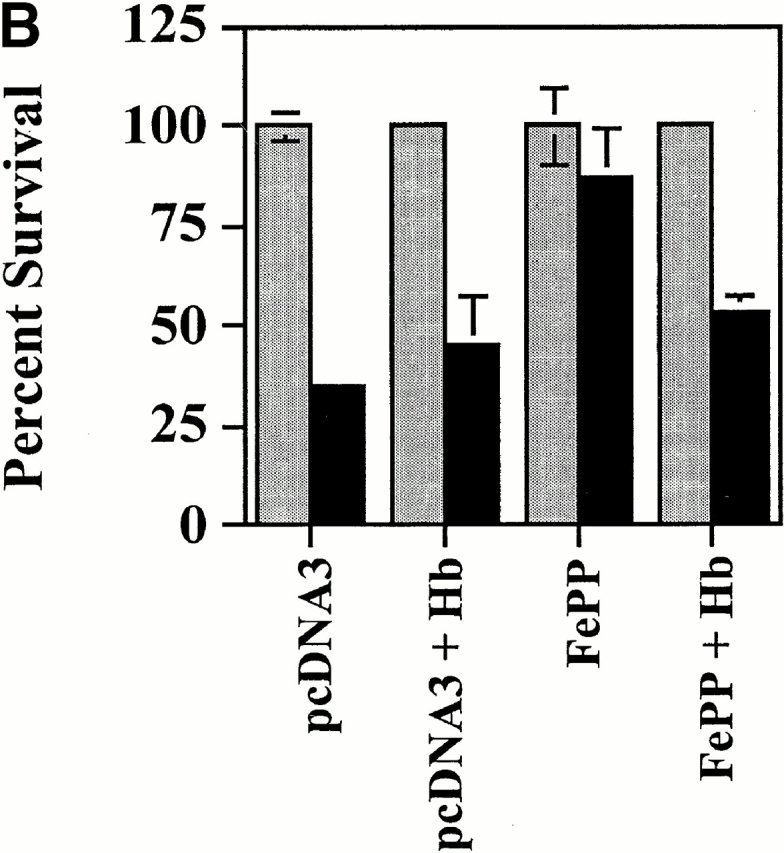

Since HO-1 enzymatic activity is needed for its antiapoptotic effect, this suggests that this antiapoptotic effect is mediated through one or more end products of heme catabolism by HO-1, i.e., bilirubin, iron, and/or CO. We tested if CO would account for the antiapoptotic effect of HO-1. ECs were transiently transfected with HO-1 and treated with Hb to scavenge CO. Under these conditions, the antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 was suppressed (Fig. 4). The ability of Hb to block the antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 was dose dependent, in that increasing concentrations of Hb (3–50 μM) decreased the ability of HO-1 to prevent EC apoptosis (Fig. 4). Hb did not impair the antiapoptotic effect of bcl-2 (Fig. 4), nor did it sensitize control ECs (pcDNA3) to apoptosis (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Scavenging of CO by Hb suppresses the antiapoptotic effect of HO-1. 2F-2B ECs were cotransfected with β-galactosidase plus control (pcDNA3), HO-1 (β-actin/HO-1), or bcl-2 expression vectors. ECs were either left untreated (0) or were treated with increasing concentrations of Hb. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. The results shown are the mean ± SD from duplicate wells taken from one representative experiment out of four.

Exogenous CO Can Substitute for HO-1 in Preventing EC Apoptosis.

If CO mediates the antiapoptotic action of HO-1, then exogenous CO should prevent EC apoptosis. The data illustrated in Fig. 5 show that this is the case. When control ECs (transfected with pcDNA3) were exposed to exogenous CO (10,000 ppm), TNF-α–mediated apoptosis was suppressed (Fig. 5). Exogenous CO also suppressed EC apoptosis when HO-1 activity was inhibited by SnPPIX, suggesting that CO can prevent EC apoptosis in the absence of other biological functions of HO-1 (Fig. 5). We then tested whether the level of exogenous CO used (10,000 ppm) was comparable to that produced when HO-1 is expressed in ECs. Given that Hb (50 μM) blocks the protective effect of endogenously produced CO (Fig. 4), we reasoned that if this was the case for exogenous CO then the effects of exogenous CO may mimic those of endogenous CO. The antiapoptotic effect of exogenous CO was suppressed by Hb (50 μM), suggesting that the concentration of exogenous CO (10,000 ppm) used in these experiments is not supraphysiologic (Fig. 5).

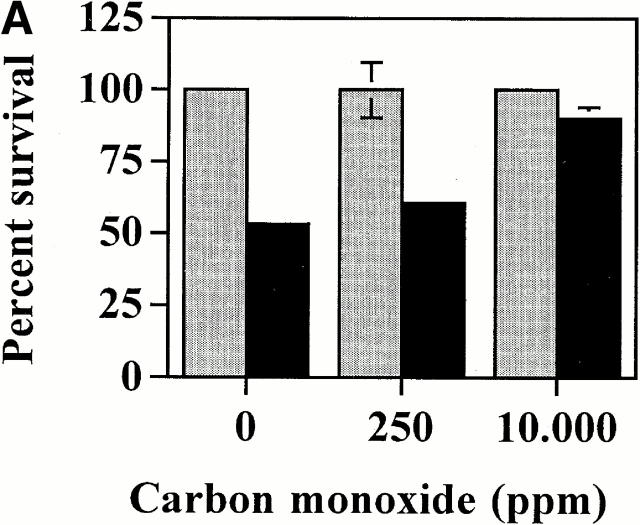

Figure 5.

Exogenous CO suppresses EC apoptosis in the absence of HO-1. (A) 2F-2B ECs were transfected with a β-galactosidase expression vector and exposed to exogenous CO. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D alone and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. (B) 2F-2B ECs were transfected with a β-galactosidase expression vector and exposed to exogenous CO (10,000 ppm) with or without Hb. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. (C) 2F-2B ECs were cotransfected with β-galactosidase and HO-1 (β-actin/HO-1) expression vectors. Where indicated (+), HO-1 enzymatic activity was inhibited by SnPPIX and/or exposed to exogenous CO. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. Results shown (A, B, and C) are the mean ± SD from duplicate wells taken from one representative experiment out of three.

ECs That Express HO-1 Can Suppress Apoptosis of ECs That Do Not Express HO-1.

Given that CO can act as an intercellular signaling molecule, we hypothesized that ECs that express HO-1 may generate sufficient levels of CO to protect neighboring ECs that do not express HO-1 from undergoing apoptosis. To test this hypothesis, ECs were transfected with control (pcDNA3) or HO-1 expression vectors and cocultured with β-galactosidase–transfected ECs. When cocultured with control ECs (pcDNA3), TNF-α plus Act.D induced apoptosis of β-galactosidase–transfected ECs (that do not express HO-1). However, when cocultured with ECs expressing HO-1, β-galactosidase–transfected ECs were protected from TNF-α plus Act.D–mediated apoptosis (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

ECs that express HO-1 suppress apoptosis of ECs that do not express HO-1. 2F-2B ECs were transfected with control (pcDNA3; I and II) or HO-1 (III) expression vectors. 16 h after transfection, ECs were harvested, washed, and cocultured at a ratio of 1:1 with ECs transfected with β-galactosidase (I and II) or with β-galactosidase plus HO-1 (III). Cocultures were maintained for an additional 24 h before induction of apoptosis by TNF-α plus Act.D. The percentage of survival was evaluated by counting the number of β-galactosidase–positive cells that retained normal morphology. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. Results shown are the mean ± SD from duplicates taken from one representative experiment out of three.

Expression of Endogenous HO-1 Inhibits EC Apoptosis via CO.

We questioned whether upregulation of endogenous HO-1 by heme would suppress EC apoptosis. The data illustrated in Fig. 7 suggest that this is the case. Exposure to heme protected ECs from TNF-α plus Act.D–mediated apoptosis (Fig. 7). This protective effect was observed only at heme concentrations ranging from 5 to 7 μM and was lost at higher concentrations, suggesting that heme becomes cytotoxic at concentrations higher than 10 μM (35; Fig. 7). The antiapoptotic effect of heme was dependent on the generation of CO, since heme was no longer able to suppress EC apoptosis when CO was scavenged by Hb (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Upregulation of endogenous HO-1 expression inhibits EC apoptosis via CO. (A) 2F-2B ECs were cotransfected with a β-galactosidase expression vector and exposed to FePP. Apoptosis was induced by TNF-α and Act.D. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. The results shown are the mean ± SD from duplicate wells taken from one representative experiment out of three. (B) 2F-2B ECs were cotransfected with a β-galactosidase expression vector and exposed to FePP (6.25 μM). Where indicated, ECs were treated with Hb (50 μM). The results shown are the mean ± SD from duplicate wells taken from one representative experiment out of three.

Iron Chelation Protects ECs from Apoptosis.

The observation that CO can prevent EC apoptosis (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5) contrasts with the notion that the antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 relies exclusively on its ability to prevent intracellular iron accumulation 34. Given that overexpression of HO-1 in ECs resulted in significant upregulation of ferritin expression (data not shown), we questioned whether elimination of reactive intracellular iron such as it occurs when ferritin is expressed would contribute to prevent TNF-α–mediated apoptosis of ECs. To mimic the iron chelator effect of ferritin, we used the iron chelator DFO and tested whether DFO would suppress EC apoptosis. The data illustrated in Fig. 8 suggest that this is the case. Induction of EC apoptosis by TNF-α plus Act.D was suppressed by DFO (Fig. 8). When HO-1 activity was inhibited by SnPPIX or the action of CO was suppressed by Hb, DFO was still able to prevent EC apoptosis (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Iron chelation by DFO suppresses EC apoptosis. (A) 2F-2B ECs were transfected with a β-galactosidase expression vector and exposed to DFO. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D alone and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. (B) 2F-2B ECs were cotransfected as described above in A. Where indicated (+), HO-1 enzymatic activity was inhibited by SnPPIX and iron was chelated by DFO, as described above in A. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. (C) 2F-2B ECs were cotransfected as described above in A. Where indicated (+), CO was removed from the culture medium by Hb and/or iron was chelated by DFO as described above in A and B. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. Results shown (A, B, and C) are the mean ± SD from duplicate wells taken from one representative experiment out of three.

CO and Iron Chelation Have Additive Effects in Protecting ECs from Apoptosis.

Given the ability of both CO and iron chelation to suppress EC apoptosis, we asked whether these two biological functions, engendered by HO-1, would act together to suppress EC apoptosis. Under inhibition of HO activity by SnPPIX, exposure to low levels of CO (250 ppm) did not suppress EC apoptosis significantly. When used alone, DFO (100 μM) suppressed EC apoptosis, but to a lesser extent than HO-1 (Fig. 9). However, when ECs were exposed to both CO (250 ppm) and DFO (100 μM), inhibition of EC apoptosis was comparable to that achieved with the expression of HO-1.

Figure 9.

Iron chelation and CO have additive effects in suppressing EC apoptosis. 2F-2B ECs were cotransfected with β-galactosidase and HO-1 (β-actin/HO-1) expression vectors. Where indicated (+), cells were treated with the inhibitor of HO enzymatic activity SnPPIX. ECs were exposed to CO (250 ppm) and to the iron chelator DFO. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. The results shown are the mean ± SD from duplicate wells taken from one representative experiment out of three.

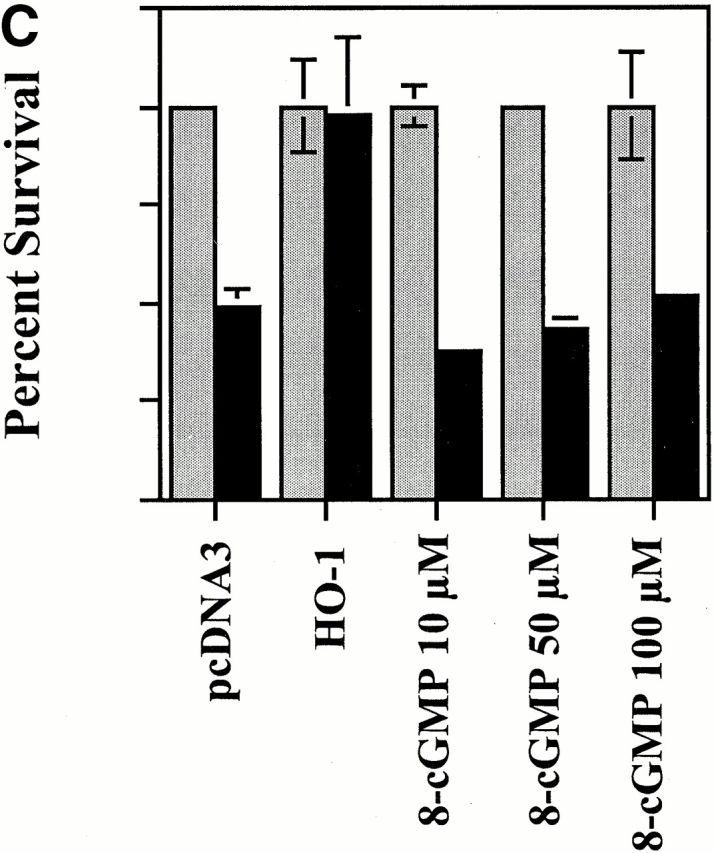

The Antiapoptotic Effect of HO-1 Is Not Mediated by Guanylcyclase Activation or cGMP Generation.

Most biological functions attributed to CO have been linked to its ability to bind guanylcyclase and increase the generation of cGMP 15 36 37. Since cGMP can regulate apoptosis 38 39, we tested whether or not the antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 acted via the activation of guanylcyclase and/or the generation of cGMP. The data illustrated in Fig. 10 suggest that this is not the case. Expression of HO-1 in ECs did not result in a detectable increase of cGMP-related functions as illustrated by the absence of VASP phosphorylation, a protein phosphorylated by cyclic nucleotide–dependent protein kinases (protein kinase G-α/β; Fig. 10). This finding is in keeping with that reported by others 40. Inhibition of guanylcyclase activity by ODQ did not suppress the antiapoptotic effects of HO-1, and the cGMP analogue 8-Br-cGMP failed to suppress EC apoptosis (Fig. 10). That 8-Br-cGMP acted as a cGMP analogue was shown by its ability to induce VASP phosphorylation (Fig. 10). That ODQ was efficient in suppressing guanylcyclase activity in ECs was shown by its ability to prevent constitutive VASP phosphorylation in 2F-2B ECs (data not shown).

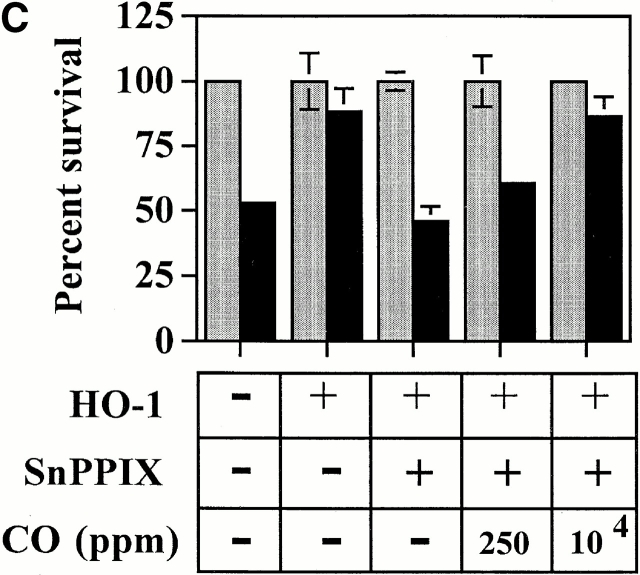

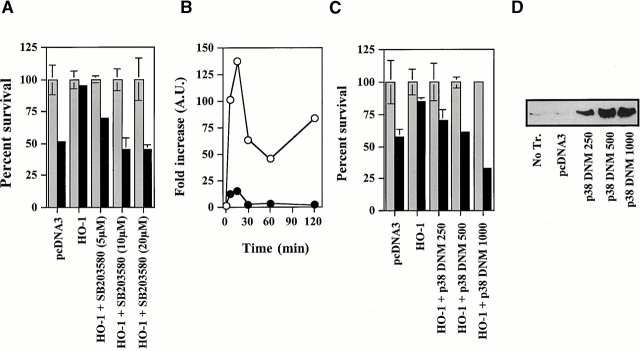

Figure 10.

The antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 does not act via a cGMP-dependent pathway. (A) 2F-2B ECs were cotransfected with β-galactosidase and HO-1 (β-actin/HO-1) expression vectors. HO-1–transfected cells were exposed to increasing doses of the guanylcyclase inhibitor ODQ. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D alone and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. The results shown are the mean ± SD from duplicate wells taken from one representative experiment out of three. (B) Activation of guanylcyclase was monitored in BAECs by analyzing the phosphorylation of VASP. P-VASP (50 kD) and VASP (46 kD) are the phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated forms of VASP, respectively. (C) 2F-2B ECs were with β-galactosidase or with β-galactosidase plus HO-1 (β-actin/HO-1) expression vectors as described above in A. Where indicated, ECs were exposed to the cGMP analogue 8-Br-cGMP, as described in Materials and Methods. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. The results shown are the mean ± SD from duplicate wells taken from one representative experiment out of three. (D) Phosphorylation of VASP was analyzed by Western blot as described above in B. N.T., nontreated.

HO-1 Increases TNF-α–mediated Activation of p38 MAPK in ECs.

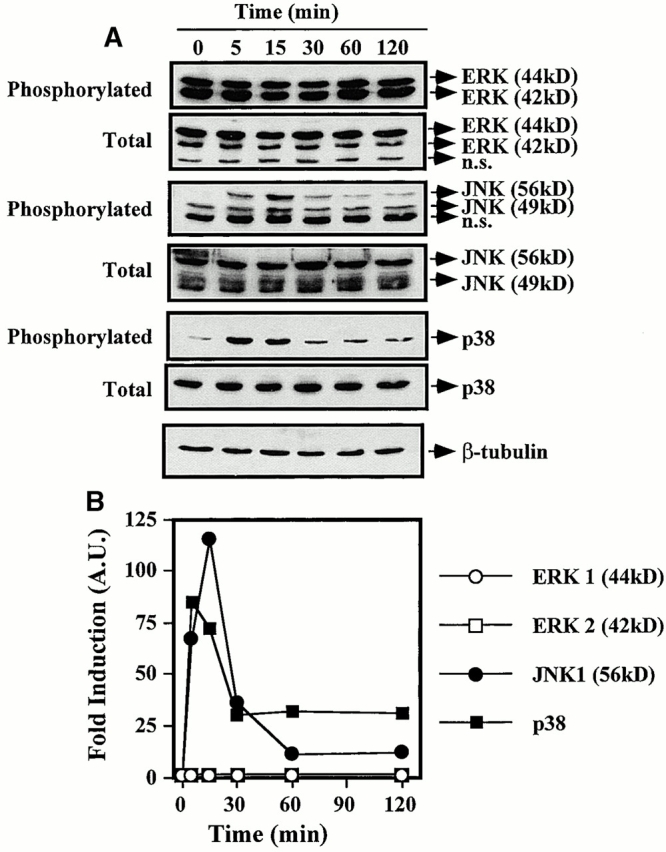

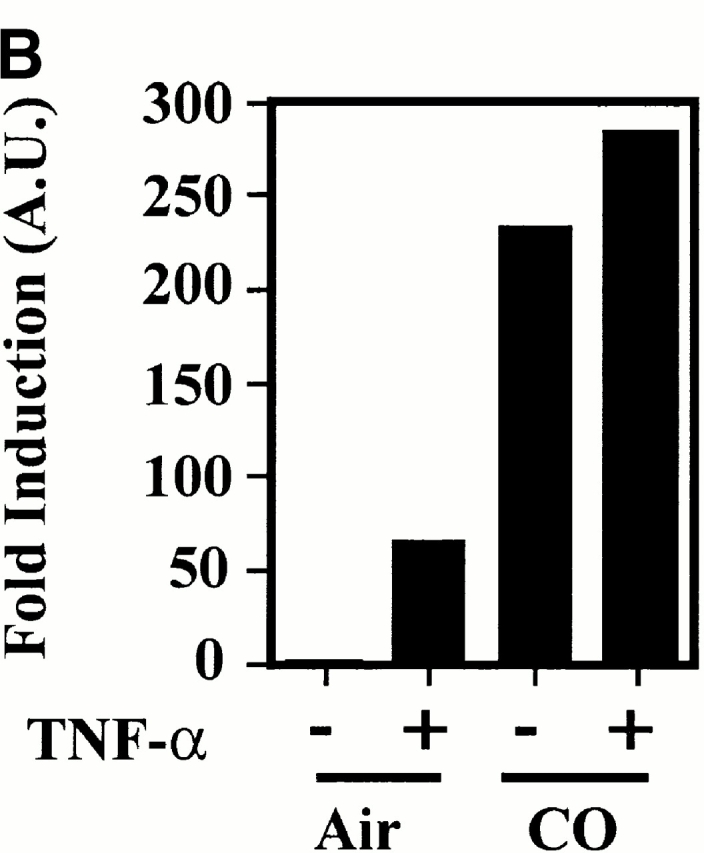

Given that HO-1 and/or CO can modulate p38 MAPK activation in monocyte/macrophages (Mφ [33]), we tested whether HO-1 and/or CO would have similar effects in ECs. Stimulation of ECs with TNF-α resulted in transient activation of JNK and p38 MAPK (Fig. 11), a finding consistent with those of others 41. ERKs (42 and 44 kD) were constitutively active in resting ECs, and no significant upregulation was detectable after TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 11). Recombinant adenovirus–mediated overexpression of HO-1 potentiated the ability of TNF-α to activate p38 MAPK (Fig. 12), but not to activate JNK (data not shown). Overexpression of β-galactosidase had no detectable effect on the activation of either p38 MAPK or JNK by TNF-α. Exposure of ECs to exogenous CO activated p38 MAPK even in the absence of TNF-α (Fig. 12).

Figure 11.

Activation of MAPK by TNF-α. (A) BAECs were stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml; time 0) and MAPK phosphorylation was monitored by Western blot (0, 5, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after TNF-α stimulation) using antibodies directed against the phosphorylated forms of each MAPK. One single membrane was used for all the stainings shown. Experiments were repeated three times with virtually identical results. n.s., nonspecific band. (B) Phosphorylation of different MAPKs was quantified. The results were presented as fold induction in arbitrary units (A.U.), compared with time 0, before TNF-α stimulation. The results in B correspond to the membranes shown in A.

Figure 12.

HO-1 and CO modulate p38 MAPK activation in ECs. (A) BAECs were either nontransduced (NT), transduced with a β-galactosidase (βgal.), or HO-1 recombinant adenovirus, and were left untreated (−) or treated (+) with TNF-α (10 ng/ml for 15 min). p38 MAPK phosphorylation was monitored by Western blot using antibodies directed against the phosphorylated forms of each MAPK. Results are presented as fold induction of MAPK activation by TNF-α in arbitrary units (A.U.), compared with time 0, before TNF-α stimulation. (B) BAECs were stimulated (+) or not (−) by TNF-α (10 ng/ml, 30 min) in the presence or absence of CO (10,000 ppm). Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK was quantified as in A. The results are presented as fold induction of MAPK activation by TNF-α in arbitrary units (A.U.).

The Mechanism by Which CO Prevents EC Apoptosis Acts via the Activation of p38 MAPK.

Since p38 MAPK can regulate apoptosis 42, we investigated whether the ability of HO-1 to modulate p38 MAPK activation was linked to its ability to prevent EC apoptosis. We found that this is the case. The antiapoptotic action of HO-1 was suppressed when p38 MAPK activation was blocked by the pyridinyl imidazol SB203580 (10–20 μM), a specific inhibitor of p38 MAPK 32. This effect was dose dependent in that increasing concentrations of SB203580 were increasingly efficient in suppressing the antiapoptotic action of HO-1 (Fig. 13). Inhibition of p38 MAPK activation per se did not sensitize ECs to TNF-α–mediated apoptosis (data not shown). As expected, activation of p38 MAPK by TNF-α was significantly inhibited (85–95%) in ECs exposed to SB203580 (5–20 μM), compared with control ECs stimulated by TNF-α in the absence of SB203580 (Fig. 13). Similarly to SB203580, overexpression of a dominant negative mutant of p38/CSBP1 43 also suppressed TNF-α–mediated p38 MAPK activation, as tested by a kinase assay using the activating transcription factor (ATF)-2 as a substrate (data not shown). Overexpression of this dominant negative mutant suppressed the ability of HO-1 to prevent EC apoptosis (Fig. 13). This inhibitory effect was dose dependent in that increasing amounts of the p38/CSBP1 dominant negative mutant were more efficient in suppressing the antiapoptotic action of HO-1 (Fig. 13).

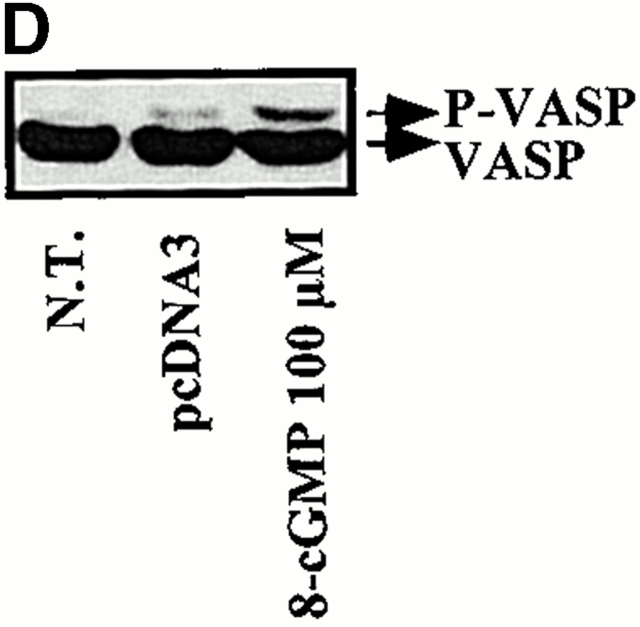

Figure 13.

The antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 acts via the activation of p38 MAPK. (A) 2F-2B ECs were cotransfected with β-galactosidase, control (pcDNA3), or HO-1 (β-actin/HO-1) expression vectors. Where indicated, ECs were treated with the p38 kinase inhibitor SB203580. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D alone and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. The results shown are the mean ± SD from duplicate wells taken from one representative experiment out of three. (B) BAECs were transfected with a control (pcDNA3) vector and stimulated with TNF-α in the presence (•) or absence (○) of the p38 kinase inhibitor SB203580 (20 μM). MAPK phosphorylation was monitored by Western blot (0, 5, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after TNF-α stimulation) using antibodies directed against the phosphorylated forms of each MAPK. (C) 2F-2B ECs were cotransfected with β-galactosidase, control, HO-1 (β-actin/HO-1), and where indicated with a phosphorylation-deficient p38/CSBP1 dominant negative mutant (DNM) expression vector. The values indicate the amount of vector used, in nanograms of DNA per 300 × 103 cells. Apoptosis was induced as in A. Gray bars represent ECs treated with Act.D and black bars represent ECs treated with TNF-α plus Act.D. The results shown are the mean ± SD from duplicate wells taken from one representative experiment out of three. (D) The expression of the p38/CSBP1 dominant negative mutant was confirmed by Western blot using an anti-p38 specific antibody. No Tr., nontransfected ECs.

Discussion

EC apoptosis is a prominent feature associated with acute and/or chronic inflammation such as it occurs during hyperoxia 44, endotoxic shock 25, arteriosclerosis 26, ischemia reperfusion injury 45 46, and acute or chronic graft rejection 23 47 48. Presumably, EC apoptosis contributes to the development of these inflammatory reactions by sustaining inflammation and promoting vascular thrombosis 25 45. The mechanism by which apoptotic ECs promote vascular thrombosis is thought to involve the expression of procoagulant phospholipids by apoptotic bodies 49 and presumably the exposure of the procoagulant subendothelial matrix that is associated with EC apoptosis. In addition, apoptotic cells can activate the complement cascade directly through the binding of C1q to apoptotic bodies 50, and promote platelet adhesion 49 that will sustain inflammation and thrombosis as well.

The observation that HO-1 prevents apoptosis induced by different proapoptotic stimuli (23 24; Fig. 1) suggests that HO-1 suppresses one or several signaling pathways that are common to a broad spectrum of proapoptotic stimuli. The antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 has recently been associated with increased cellular iron efflux through the upregulation of an iron pump that remains to be fully characterized 34. According to this study 34, HO-1 inhibits apoptosis by limiting the availability of prooxidant-free iron to participate in the generation of reactive oxygen species through the Fenton reaction, a well-established component in the signaling cascades leading to apoptosis 51. We hypothesized that HO-1 may have additional effects that could contribute to suppress EC apoptosis, such as by generating CO. Data from L.E. Otterbein, A.M.K. Choi, and colleagues have suggested that this may be the case in fibroblasts 52. However, data from other laboratories have suggested that in 293 cells CO is not antiapoptotic 34. Moreover, CO has been suggested to be proapoptotic in ECs 53. This data suggests that HO-1 can suppress EC apoptosis and that the antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 is mediated through the generation of CO (Fig. 4, Fig. 5, and Fig. 7).

The observation that the elimination of endogenous CO by Hb abrogates the cytoprotective effect of HO-1 (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5) supports the notion that, in the absence of CO, other biological functions engendered by HO-1, i.e., upregulation of ferritin expression and subsequent iron chelation, are not sufficient per se to prevent EC apoptosis (Fig. 4 and Fig. 7). Given the above, it is difficult to understand why iron chelation by DFO can protect ECs from apoptosis, even under conditions in which the action of CO is prevented (i.e., inhibition of HO-1 activity by SnPPIX or elimination of CO by Hb; Fig. 8). At least two possible interpretations may explain these observations: (a) DFO may have a higher ability to “eliminate” free iron compared with ferritin, and/or (b) DFO may have additional effects that contribute to prevent EC apoptosis, independently of its ability to eliminate free iron. In any case, these observations suggest that DFO does not, at least fully, mimic the effect of HO-1–mediated ferritin expression in preventing EC apoptosis.

Our data also suggest that CO, generated by cells that express HO-1, acts as an intercellular signaling molecule to prevent apoptosis of cells that do not express HO-1 (Fig. 6). If a similar effect of CO would occur in vivo, these data would suggest that vascular ECs at sites of inflammation might protect neighboring cells, such as infiltrating leukocytes that immigrate into sites of inflammation or smooth muscle cells in blood vessels from undergoing apoptosis.

The antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 in ECs is not mediated by guanylylcyclase and/or by the generation of cGMP (Fig. 10). This is in contrast to data showing that inhibition of guanylcyclase suppresses the antiapoptotic effect of HO-1 and/or CO in fibroblasts 51. Our interpretation is that the mechanism by which HO-1 and/or CO prevents apoptosis is cell type specific.

Based on the finding by Otterbein et al. that HO-1/CO activates p38 MAPK in Mφ 33, we tested whether HO-1 and/or CO would have similar effects in ECs. We found that this is the case (Fig. 12). However, contrary to Mφ, exogenous CO per se induced the activation of p38 MAPK in ECs, whereas HO-1 did not (Fig. 12). Possible explanations for the difference between HO-1 and CO in regulating p38 MAPK activation include the following. Whereas CO generated by HO-1 activates p38 MAPK, other end products of HO-1 activity may inhibit p38 activation. Alternatively, the level of CO, generated by HO-1, is significantly lower than exposure to exogenous CO as we used it. Whatever the explanation, these data show that CO can specifically modulate the activation of p38 MAPK.

We also found that the antiapoptotic effect of HO-1/CO acts via the activation of a transduction pathway involving the activation of p38 MAPK (Fig. 13). This is consistent with findings by others showing that activation of p38 MAPK is key in regulating apoptosis in a variety of cell types including the kidney epithelial cell line HeLa 54, cardiac muscle cells 55, and lymphoid Jurkat T cells 54 56. The mechanism by which the activation of p38 MAPK modulates the induction of apoptosis is not well understood.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that CO, generated through heme catabolism by HO-1, acts as an antiapoptotic molecule that can suppress EC apoptosis. We show that the mechanism of action of CO involves the activation of p38 MAPK. These findings further support the notion that HO-1 acts as a protective gene and thereby contributes to prevent a series of inflammatory reactions that are associated with EC apoptosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Neil R. Smith for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a grant (Roche Organ Transplantation Research Foundation 998521355) awarded to M.P. Soares and a National Institutes of Health grant (HL58688) awarded to F.H. Bach. S. Brouard was supported by a grant from Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC) and by a grant from Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (Inserm), France. F.H. Bach is the Lewis Thomas Professor at Harvard Medical School and is a paid consultant for Novartis Pharma. This work was supported in part by Novartis Pharma, Basel, Switzerland. This is paper no. 800 from our laboratories.

Footnotes

A.M.K. Choi and M.P. Soares contributed equally to this work.

Abbreviations used in this paper: Act.D, actinomycin D; BAEC, bovine aortic endothelial cell; CoPPIX, cobalt protoporphyrin; DFO, deferoxamine mesylate; EC, endothelial cell; ERK, extracellular signal–regulated kinase; FePP, iron protoporphyrin; GFP, green fluorescent protein; Hb, hemoglobin; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; JNK, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; Mφ, monocyte/macrophage(s); ppm, parts per million; SnPPIX, tin protoporphyrin; VASP, vasodilatator-stimulated phosphoprotein.

References

- Cines D.B., Pollak E.S., Buck C.A., Loscalzo J., Zimmerman G.A., McEver R.P., Pober J.S., Wick T.M., Konkle B.A., Schwartz B.S. Endothelial cells in physiology and in the pathophysiology of vascular disorders. Blood. 1998;91:3527–3561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C.C., Savage C.O., Pober J.S. The endothelial cell as a regulator of T-cell function. Immunol. Rev. 1990;117:85–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1990.tb00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A., Bussolino F., Introna M. Cytokine regulation of endothelial cell functionfrom molecular level to the bedside. Immunol. Today. 1997;18:231–240. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)81662-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer T.A. Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature. 1990;346:425–434. doi: 10.1038/346425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares M.P., Ferran C., Sato K., Takigami K., Anrather J., Lin Y., Bach F.H. Protective responses of endothelial cells. In: World Health Organization and Foundation IPSEN. V. Boulyjenkov, K. Berg, and Y. Christen,, editor. Genes and Resistance to Disease. Springer-Verlag; Heidelberg: 2000. pp. 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Bach F.H., Hancock W.W., Ferran C. Protective genes expressed in endothelial cellsa regulatory response to injury. Immunol. Today. 1997;18:483–486. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroka D.M., Badrichani A.Z., Bach F.H., Ferran C. Overexpression of A1, an NF-κB-inducible anti-apoptotic bcl gene, inhibits endothelial cell activation. Blood. 1999;93:3803–3810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferran C., Stroka D.M., Badrichani A.Z., Cooper J.T., Wrighton C.J., Soares M., Grey S.T., Bach F.H. A20 inhibits NF-κB activation in endothelial cells without sensitizing to tumor necrosis factor-mediated apoptosis. Blood. 1998;91:2249–2258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J.T., Stroka D.M., Brostjan C., Palmetshofer A., Bach F.H., Ferran C. A20 blocks endothelial cell activation through a NF-κB-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:18068–18073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.18068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badrichani A.Z., Stroka D.M., Bilbao G., Curiel D.T., Bach F.H., Ferran C. Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL serve an anti-inflammatory function in endothelial cells through inhibition of NF-κB. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:543–553. doi: 10.1172/JCI2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maines M.D. The heme oxygenase systema regulator of second messenger gases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1997;37:517–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi A.M., Alam J. Heme oxygenase-1function, regulation, and implication of a novel stress-inducible protein in oxidant-induced lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1996;15:9–19. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.1.8679227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis D. Overview of HO-1 in inflammatory pathologies. In: Willoughby D.A., Tomlinson A., editors. Inducible Enzymes in the Inflammatory Response. Birkhauser; Basel: 1999. pp. 55–96. [Google Scholar]

- Balla G., Jacob H.S., Balla J., Rosenberg M., Nath K., Apple F., Eaton J.W., Vercellotti G.M. Ferritina cytoprotective antioxidant strategem of endothelium. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:18148–18153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Quan S., Abraham N.G. Retrovirus-mediated HO gene transfer into endothelial cells protects against oxidant-induced injury. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:L127–L133. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.1.L127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham N.G., Lavrovsky Y., Schwartzman M.L., Stoltz R.A., Levere R.D., Gerritsen M.E., Shibahara S., Kappas A. Transfection of the human heme oxygenase gene into rabbit coronary microvessel endothelial cellsprotective effect against heme and hemoglobin toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:6798–6802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poss K.D., Tonegawa S. Reduced stress defense in heme oxygenase 1-deficient cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:10925–10930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein L., Sylvester S.L., Choi A.M. Hemoglobin provides protection against lethal endotoxemia in ratsthe role of heme oxygenase-1. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1995;13:595–601. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.5.7576696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein L., Chin B.Y., Otterbein S.L., Lowe V.C., Fessler H.E., Choi A.M. Mechanism of hemoglobin-induced protection against endotoxemia in ratsa ferritin-independent pathway. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:L268–L275. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.2.L268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein L.E., Kolls J.K., Mantell L.L., Cook J.L., Alam J., Choi A.M. Exogenous administration of heme oxygenase-1 by gene transfer provides protection against hyperoxia-induced lung injury. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:1047–1054. doi: 10.1172/JCI5342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis D., Moore A.R., Frederick R., Willoughby D.A. Heme oxygenasea novel target for the modulation of the inflammatory response. Nat. Med. 1996;2:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nm0196-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amersi F., Buelow R., Kato H., Ke B., Coito A., Shen X., Zhao D., Zaky J., Melinek J., Lassman C. Upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 protects genetically fat Zucker rat livers from ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:1631–1639. doi: 10.1172/JCI7903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares M.P., Lin Y., Anrather J., Csizmadia E., Takigami K., Sato K., Grey S.T., Colvin R.B., Choi A.M., Poss K.D., Bach F.H. Expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) can determine cardiac xenograft survival. Nat. Med. 1998;4:1073–1077. doi: 10.1038/2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock W.W., Buelow R., Sayegh M.H., Turka L.A. Antibody-induced transplant arteriosclerosis is prevented by graft expression of anti-oxidant and anti-apoptotic genes. Nat. Med. 1998;4:1392–1396. doi: 10.1038/3982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haimovitz F.A., Cordon-Cardo C., Bayoumy S., Garzotto M., McLoughlin M., Gallily M., Edwards C., III, Schuchman E.H., Fuks Z., Kolesnick R. Lipopolysaccharide induces disseminated endothelial cell apoptosis requiring ceramide. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:1831–1841. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.11.1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler S., Hermann C., Zeiher A.M. Apoptosis of endothelial cells. Contribution to the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis? Eur. Cytokine Netw. 1998;9:697–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anrather J., Csizmadia V., Brostjan C., Soares M.P., Bach F.H., Winkler H. Inhibition of bovine endothelial cell activation in vitro by regulated expression of a transdominant inhibitor of NF-κB. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:763–772. doi: 10.1172/JCI119222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares M.P., Muniappan A., Kaczmarek E., Koziak K., Wrighton C.J., Steinhauslin F., Ferran C., Winkler H., Bach F.H., Anrather J. Adenovirus mediated expression of a dominant negative mutant of p65/RelA inhibits proinflammatory gene expression in endothelial cells without sensitizing to apoptosis. J. Immunol. 1998;161:4572–4582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P.J., Alam J., Wiegand G.W., Choi A.M. Overexpression of heme oxygenase-1 in human pulmonary epithelial cells results in cell growth arrest and increased resistance to hyperoxia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:10393–10398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibahara S., Yoshizawa M., Suzuki H., Takeda K., Meguro K., Endo K. Functional analysis of cDNAs for two types of human heme oxygenase and evidence for their separate regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;113:214–218. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein L.E., Lee P.J., Chin B.Y., Petrache I., Camhi S.L., Alam J., Choi A.M. Protective effects of heme oxygenase-1 in acute lung injury. Chest. 1999;116:61S–63S. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.suppl_1.61s-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.C., Laydon J.T., McDonnell P.C., Gallagher T.F., Kumar S., Green D., McNulty D., Blumenthal M.J., Heys J.R., Landvatter S.W. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature. 1994;372:739–746. doi: 10.1038/372739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein L.E., Bach F.H., Alam J., Soares M.P., Tao H.L., Wysk M., Davis R., Flavell R., Choi A.M.K. Carbon monoxide mediates anti-inflammatory effects via the mitogen activated protein kinase pathway. Nat. Med. 2000;6:422–428. doi: 10.1038/74680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris C., Jaffrey S., Sawa A., Takahashi M., Brady S., Barrow R., Tysoc S., Wolosker H., Baranano D., Dore S. Haem oxygenase-1 prevents cell death by regulating cellular iron. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:152–157. doi: 10.1038/11072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balla J., Jacob H.S., Balla G., Nath K., Eaton J.W., Vercellotti G.M. Endothelial-cell heme uptake from heme proteinsinduction of sensitization and desensitization to oxidant damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:9285–9289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita T., Perrella M.A., Lee M.E., Kourembanas S. Smooth muscle cell-derived carbon monoxide is a regulator of vascular cGMP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:1475–1479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma A., Hirsch D.J., Glatt C.E., Ronnett G.V., Snyder S.H. Carbon monoxidea putative neural messenger. Science. 1993;259:381–384. doi: 10.1126/science.7678352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.M., Talanian R.V., Billiar T.R. Nitric oxide inhibits apoptosis by preventing increases in caspase-3-like activity via two distinct mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:31138–31148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.31138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiche J.D., Schlutsmeyer S.M., Bloch D.B., de la Monte S.M., Roberts J.D., Jr., Filippov G., Janssens S.P., Rosenzweig A., Bloch K.D. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of cGMP-dependent protein kinase increases the sensitivity of cultured vascular smooth muscle cells to the antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of nitric oxide/cGMP. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:34263–34271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttner D.M., Dennery P.A. Reversal of HO-1 related cytoprotection with increased expression is due to reactive iron. FASEB (Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol.) J. 1999;13:1800–1809. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.13.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roulston A., Reinhard C., Amiri P., Williams L.T. Early activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 kinase regulate cell survival in response to tumor necrosis factor alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:10232–10239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakis J.M., Avruch J. Sounding the alarmprotein kinase cascades activated by stress and inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:24313–24316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Huang S., Sah V.P., Ross J., Jr., Brown J.H., Han J., Chien K.R. Cardiac muscle cell hypertrophy and apoptosis induced by distinct members of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase family. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:2161–2168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein L.E., Mantell L.L., Choi A.M. Carbon monoxide provides protection against hyperoxic lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:L688–L694. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.4.L688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cursio R., Gugenheim J., Ricci J.E., Crenesse D., Rostagno P., Maulon L., Saint-Paul M.C., Ferrua B., Auberger A.P. A caspase inhibitor fully protects rats against lethal normothermic liver ischemia by inhibition of liver apoptosis. FASEB (Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol.) J. 1999;13:253–261. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaoita H., Ogawa K., Maehara K., Maruyama Y. Attenuation of ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats by a caspase inhibitor. Circulation. 1998;97:276–281. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach F.H., Ferran C., Soares M., Wrighton C.J., Anrather J., Winkler H., Robson S.C., Hancock W.W. Modification of vascular responses in xenotransplantationinflammation and apoptosis. Nat. Med. 1997;3:944–948. doi: 10.1038/nm0997-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouard S., Cuturi M.C., Pignon P., Buelow R., Loth P., Moreau A., Soulillou J.P. Prolongation of heart xenograft survival in a hamster-to-rat model after therapy with a rationally designed immunosuppressive peptide. Transplantation. 1999;67:1614–1618. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199906270-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombeli T., Schwartz B.R., Harlan J.M. Endothelial cells undergoing apoptosis become proadhesive for nonactivated platelets. Blood. 1999;93:3831–3838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korb L.C., Ahearn J.M. C1q binds directly and specifically to surface blebs of apoptotic human keratinocytescomplement deficiency and systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. J. Immunol. 1997;158:4525–4528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G., Petit P., Zamzami N., Vayssiere J.L., Mignotte B. The biochemistry of programmed cell death. FASEB (Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol.) J. 1995;9:1277–1287. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.13.7557017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrache I., Otterbein L.E., Alam J., Wiegand G.W., Choi A.M. Heme oxygenase-1 inhibits TNF-α-induced apoptosis in cultured fibroblast. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2000;278:312–319. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.2.L312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom S.R., Fisher D., Xu Y.A., Notarfrancesco K., Ishiropoulos H. Adaptive responses and apoptosis in endothelial cells exposed to carbon monoxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:1305–1310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto S., Xiang J., Huang S., Lin A. Induction of apoptosis by SB202190 through inhibition of p38beta mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:16415–16420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Su B., Sah V.P., Brown J.H., Han J., Chien K.R. Cardiac hypertrophy induced by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7, a specific activator for c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase in ventricular muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:5423–5426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Jiang Y., Li Z., Nishida E., Mathias P., Lin S., Ulevitch R.J., Nemerow G.R., Han J. Apoptosis signaling pathway in T cells is composed of ICE/Ced-3 family proteases and MAP kinase kinase 6b. Immunity. 1997;6:739–749. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80449-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]