Abstract

Using an expression gene trapping strategy, we recently identified a novel gene, hematopoietic zinc finger (Hzf), which encodes a protein containing three C2H2-type zinc fingers that is predominantly expressed in megakaryocytes. Here, we have examined the in vivo function of Hzf by gene targeting and demonstrated that Hzf is essential for megakaryopoiesis and hemostasis in vivo. Hzf-deficient mice exhibited a pronounced tendency to rebleed and had reduced α-granule substances in both megakaryocytes and platelets. These mice also had large, faintly stained platelets, whereas the numbers of both megakaryocytes and platelets were normal. These results indicate that Hzf plays important roles in regulating the synthesis of α-granule substances and/or their packing into α-granules during the process of megakaryopoiesis.

Keywords: α-granules, hemorrhage, hemostasis, megakaryopoiesis, thrombopoiesis

Introduction

During hematopoiesis, anucleate platelets are generated from megakaryocytes and have an essential role in maintaining hemostasis in vivo. During megakaryocyte differentiation, megakaryocyte-restricted progenitor cells commence an unusual process, terminal endomitosis, in which DNA replication occurs but neither the nucleus nor the cell undergoes division (1). Hence, mature megakaryocytes are invariably polyploid, containing 4N to 64N of the normal diploid amount of DNA (2). Because platelets can produce only limited amounts of proteins, their cytoplasmic structures, including characteristic granules, are mostly derived from megakaryocytes (3). Morphologically, four distinct categories of granules differing in their internal constituents are produced by maturing megakaryocytes: α-granules, dense granules, lysosomal granules, and microperoxisomal granules (3). The α-granules, which are the most numerous, contain various proteins, including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)*, platelet factor 4, and von Willebrand factor (vWF). These proteins are synthesized in megakaryocytes and then transported to α-granules. These packed α-granules are subsequently shed from megakaryocytes (4). Thus, the process of megakaryocyte differentiation involves a complex series of cellular processes that culminate in the generation of functionally mature platelets.

Genetic approaches involving gene targeting in mice have revealed several genes and their protein products that are essential for megakaryopoiesis. These include various transcription factors, such as p45 NF-E2 (5), mafG (6), GATA-1 (7), and Fli-1 (8). The transcription factor NF-E2 is a heterodimer of two proteins, p45 and p18, that are members of the Cap'n'Collar protein and Maf subfamilies, respectively (9, 10). Deficiency of the p45 NF-E2 gene blocks completion of megakaryopoiesis and results in the complete absence of platelets (5), whereas the absence of MafG leads to hyperproliferation of megakaryocytes and mild thrombocytopenia (6). Mice carrying megakaryocyte-specific deletion of the GATA-1 zinc finger protein exhibit severely impaired cytoplasmic maturation of megakaryocytes and reduced platelet numbers (7). Mice carrying a null mutation in Fli-1, a member of the ETS family of winged helix-turn-helix transcription factors, exhibit a block in megakaryocyte differentiation (8).

The process of megakaryocyte differentiation also requires the interaction between thrombopoietin (TPO), also known as megakaryocyte growth and development factor (MGDF), and its cognate receptor c-Mpl (11–18). The ligand TPO/MGDF increases megakaryocyte ploidy at low concentrations while the final stage of platelet release is not dependent on TPO/MGDF (19). c-mpl–deficient mice exhibit thrombocytopenia and impaired megakaryopoiesis (20, 21). In addition, TPO/MGDF null mutant mice have decreased number of both platelets and megakaryocyte progenitors, and lower ploidy levels of megakaryocytes (22). Interestingly, both c-Mpl and TPO/MGDF null mice do not exhibit a bleeding disorder, suggesting that platelets produced from the abnormal megakaryocytes in these mice can function normally.

Using an approach that we have termed ‘expression gene trapping,’ we have previously identified and mutated in embryonic stem (ES) cells a number of genes that are expressed in hematopoietic and/or endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo (23, 24). One of these genes, hematopoietic zinc finger (Hzf), encodes a novel zinc finger protein which is predominantly expressed in megakaryocytes (24). Mice homozygous for the gene trapped allele of Hzf (Hzf gt/gt) exhibit no obvious phenotype (24). Transcripts corresponding to the Hzf gene were detected in Hzf gt/gt mice, consistent with the possibility that the trapped Hzf allele generated in our previous study was not a null allele. Therefore, to investigate the in vivo role of Hzf, we generated mice with a null Hzf mutation by gene targeting. Here we describe the essential function of Hzf in α-granule formation and megakaryopoiesis.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Hzf −/− Mutant Mice.

DNA fragments corresponding to the murine Hzf gene fragments were cloned from a 129/Sv genomic DNA library using a mouse Hzf cDNA probe (24). 17 overlapping phage genomic clones containing exons encoding three zinc finger domains were isolated. A targeting vector was designed to replace a 5.5-kb genomic fragment including the exons encoding three zinc finger domains with an internal ribosome-entry site (IRES) LacZ and a neomycin resistant gene (neo). IRES LacZ and neo were inserted in the pPNT targeting vector in the sense orientation to Hzf transcription, such that IRES LacZ was flanked on the 3′ side by 1.6 kb of genomic DNA and that neo was flanked on the 5′ side by 4.5 kb of genomic DNA. The targeting vector was linearized with NotI and electroporated into R1 ES cells. After positive-negative selection with gancyclovir and G418, 800 surviving clones were picked and screened by Southern blot analysis. Three out of six homologous recombinant ES clones were aggregated into CD1 blastomeres and transferred to foster mothers to generate chimeras. Chimeric mice were mated with CD1 females, and germline transmission of the mutant allele was verified by PCR and Southern blot analysis of ear punched tissues and tail DNA from F1 offspring. A primer “a” and “b” specific for the Hzf gene (5′-GGACCCTGTACAGAAAGCTGT-3′ and 5′-GCTTGGTCTACAGAGTGATT-3′, respectively) and a primer “c” specific for the IRES gene (5′-GGAGGGAGAGGGGCGGAATT-3′) were used in PCR analysis. Germline transmission of the targeted Hzf allele was achieved for three independent ES clones. F2 offspring from heterozygous intercrosses were genotyped by Southern blotting. Mutant mice derived from three targeted ES cells showed the identical phenotype.

Histological Analysis.

Organs were isolated in ice-cold PBS 3 wk after birth, fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C (for brains, fixed at least 1 wk in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C), dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Sections 5-μm thick were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Hematological Analysis.

4-wk-old mice were anesthetized with methoxyflurane. Peripheral blood was collected by heparinized capillary puncture of the retroorbital venous plexus into a tube containing 5 μl of 0.5 M EDTA, pH 8.0 (Becton Dickinson). Peripheral blood cell counts were determined with MASCOT automated hematology system (CDC Technologies). Blood smears and bone marrow smears were stained with Wright-Giemsa stain.

The preparation of platelets was performed essentially as described previously (25). Peripheral blood, which was prepared as described above, was centrifuged at 300× g for 10 min at room temperature to obtain platelet-rich plasma. The platelets were washed three times with PBS by centrifugation at 1,300× g for 10 min and were used immediately for Western immunoblot analysis.

Bleeding Time Assays.

Bleeding times were measured as described previously (26, 27) using 4-wk-old mice. 2 mm of the tip at the tail was cut with a sharp scalpel blade, the tail was placed in a solution of saline at 37°C, and the time for the flow of blood to cease was recorded. Genotyping of the animals took place after this procedure so that tails were intact for bleeding-time measurements. If bleeding restarted within 1 min, this result was recorded as a rebleed and taken to indicate an unstable hemostatic event.

Measurements of Megakaryocyte Frequency and DNA Content.

DNA distribution of megakaryocytes in unfractionated bone marrow cells was determined as described previously (2, 28). Bone marrow cells were harvested from Hzf mutant and control mice.

CFU-Mk Assay.

Megakaryocyte progenitor cells, in the bone marrow from Hzf mutant and control mice, were assayed in collagen-based media (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with recombinant human TPO (50 ng/ml), IL-6 (20 ng/ml), IL-11 (50 ng/ml), and recombinant mouse IL-3 (10 ng/ml). Colonies were stained for acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity counted after 6 d incubation.

Ultrastructural Studies.

Freshly excised spleens obtained from 3–5-wk-old Hzf −/− and control mice were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde (Canemco, Inc.) in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3, (Canemco, Inc.). Samples were washed with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3, postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3, dehydrated in graded ethanols, and embedded in spurr epoxy resin (Canemco, Inc.). Embedded tissues were sectioned with an RMC 6000 ultramicrotome, (RMC-EM), stained with uranyl acetate, lead citrate, and examined in a Philips CM 100 electron microscope (Philips Electron Optics).

For platelet analysis, blood was collected into a syringe with prewarmed 2% glutaraldehyde (Canemco, Inc.) in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3 (Canemco, Inc.), from the inferior vena cava of anesthetized mice. Immediately, the syringe was inverted several times and was set at room temperature for 2 h. Platelet-rich plasma was prepared as described above and then analyzed, as described previously (29).

For quantitative estimation of vacant α-granules in platelets, dense and vacant α-granules were counted in platelets from Hzf +/+ and −/− mice by observers blinded to the experiment. The frequency of vacant α-granules was calculated from the number of detected vacant α-granules divided by that of dense α-granules.

To estimate the levels of PDGF-A in megakaryocytes, freshly excised spleens obtained from 3–5-wk-old Hzf −/− and control mice were fixed in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3 containing a combination of 0.1% glutaraldehyde (Canemco, Inc.) and 4% paraformaldehyde (Canemco, Inc.). The samples were washed with the same buffer, dehydrated with graded ethanol, infiltrated in lowicryl (Canemco, Inc.), and polymerized under UV at –20°C overnight. The sections were rinsed with PBS containing 0.15% glycine and 0.5% BSA, washed with 0.5% BSA in PBS, and then reacted with anti–PDGF-A antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) for 1 h at 22°C. After washing with 0.5% BSA in PBS, the sections were treated with anti–rabbit IgG conjugated with 10-nm gold (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). After washing with 0.5% BSA in PBS, PBS, and H2O, the sections were stained with uranyl acetate, lead citrate, and examined in the Philips CM 100 electron microscope. Then, PDGF-A labeling by counting the gold particles was determined as described previously (30). Briefly, the field (3.35 × 2.7 μm2) from the immunogold stained sections were determined with a minimum of 10 high power field counted per mouse. The frequency of PDGF-A gold particles in α-granules was calculated from the number of detected gold particles in α-granules divided by that in the whole field.

Western Blot Analysis.

Bone marrow cells were isolated from 4-wk-old Hzf +/+ and Hzf −/− mice, after washed with PBS, and subsequently suspended in lysis buffer (25). Soluble fractions from each sample were boiled with sample buffer for SDS-PAGE. Eluted proteins were separated by electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell). Immunoblotting was performed as described previously (25). We evaluated AChE expression to ensure equivalent sample loading. Commercially available Abs to vWF (Dako), fibrinogen (ICN Biochemicals), PDGF-A (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), PDGF-B (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), and AChE (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) were used at the concentrations of 57 μg/ml, 160 μg/ml, 5 μg/ml, 5 μg/ml, and 5 μg/ml, respectively. Goat anti–rabbit IgG Ab-conjugated with HRP and donkey anti–goat IgG Ab conjugated with HRP were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., respectively. The signals were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) as directed by the manufacturer.

The detection of platelet proteins was performed basically as described previously (25). Briefly, washed platelets were lysed with the same lysis buffer, as described above. Whole platelets were treated with standard sample buffer and loaded onto 10% SDS-PAGE following the same protocol as described above. We evaluated glycoprotein (GP)IIb to ensure equivalent platelet protein loading. The anti–mouse GPIIb mAb and anti–rat IgG Ab conjugated with HRP were purchased from BD PharMingen and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., respectively. The anti-GPIIb mAb and the anti–rat IgG Ab conjugated with HRP were used at the concentrations of 0.25 μg/ml and 0.8 μg/ml, respectively. The signal-enhancement was performed as described above.

RT-PCR Analysis.

Bone marrow cells, from male Hzf +/+ and Hzf −/− mice, were used for RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis, as described previously (31). The detailed method for RT-PCR and the primer sequences were described elsewhere (5, 32). We equalized cDNAs from male Hzf +/+ and Hzf −/− bone marrow cells by RT-PCR of hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase. The RT-PCR products were analyzed by PAGE.

Statistical Analysis.

Data were analyzed by using Student's t test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All experiments were performed at least three times.

Results

Generation of Hzf −/− Mutant Mice.

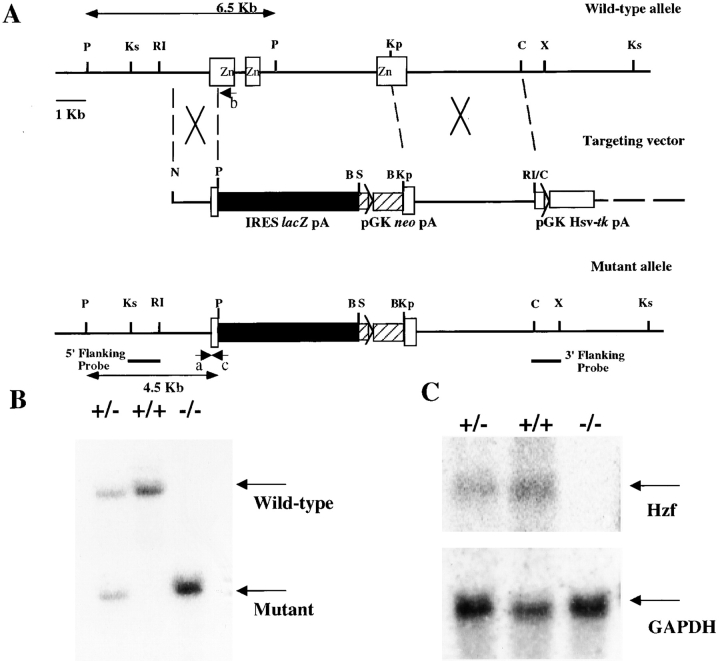

The Hzf gene was disrupted in murine ES cells using a targeting vector in which the exons encoding three zinc finger motifs were deleted (Materials and Methods, and Fig. 1 A). The targeting vector was electroporated into R1 ES cells. After positive-negative selection and genotyping by Southern blot analysis as described in Materials and Methods, six independent clones were identified as heterozygous for the targeted mutation at the Hzf locus. Three out of the six heterozygous mutant ES clones were used to generate chimeric mice. Chimeras were backcrossed to CD1 mice to generate mice heterozygous for the Hzf mutation. Heterozygous Hzf +/− mice were fertile and were intercrossed to generate homozygous Hzf −/− mice (Fig. 1 B). The null mutation of Hzf was confirmed by the absence of Hzf expression, as determined by Northern blot analysis of RNA extracted from brains of Hzf mutant mice at 3 wk after birth (Fig. 1 C).

Figure 1.

Targeted disruption of the Hzf locus. (A) A portion of the mouse 129/Sv Hzf wild-type locus (top) showing exons (open boxes) and a 6.5-kb PstI fragment in the wild-type allele. The targeting vector (middle) was designed to replace exons encoding three zinc finger domains with an IRES LacZ (closed box) and a neo (hatched box). The mutated Hzf locus (bottom) contains a 4.5-kb PstI fragment. The positions of the 5′ flanking and 3′ flanking probes used for Southern blot analysis are shown. Positions of PCR primers for the wild-type allele (a and b) and the mutant allele (c) are also shown. P, Ks, RI, Kp, C, X, and B represent PstI, KspI, EcoRI, KpnI, ClaI, XhoI, and BamHI sites, respectively. (B) Genomic DNA was isolated from Hzf +/+, Hzf +/−, and Hzf −/− mice, digested with PstI and analyzed by Southern blot analysis. Wild-type (6.5-kb) and mutant (4.5-kb) bands are indicated. (C) Northern blot analysis of Hzf expression. Total RNA extracted from the brains (40 μg per lane) was analyzed for the expression of transcripts corresponding to the Hzf gene.

Hemorrhage and Neonatal Lethality of Hzf −/− Mice.

Initial examination of the progeny from Hzf +/− parents revealed a reduced frequency of Hzf −/− mice at 3 wk of age. To determine the stage of neonatal development affected by the Hzf mutation, neonatal genotyping was performed. Of 300 offspring derived from heterozygous matings, 1-wk-old Hzf −/− pups were viable, usually of normal size, and were present in the expected Mendelian frequency. However, thereafter, especially between 2–3 wk after birth, the percentage of homozygotes decreased (Table I).

Table I.

Genotype Analysis of the Progeny from Hzf Heterozygous Intercrosses

| Number of mice of each genotype

|

Percentage

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | +/+ | +/− | −/− | Total | −/− |

| % | |||||

| 1 wk | 10 | 22 | 12 | 44 | 27 |

| 2 wk | 6 | 22 | 8 | 36 | 22 |

| 3 wk | 32 | 90 | 24 | 146 | 16 |

| 4 wk | 16 | 27 | 10 | 53 | 19 |

| Total | 295 | ||||

Breeding pairs were set up between Hzf +/− males and females (129 × CD1 mixed background). Tails of newborn and weaning pups were collected at the time of 1, 2, 3, and 4 wk after birth. The genotypes were determined by PCR analyses, as described in Materials and Methods. Each genotyping was confirmed by Southern blot analyses.

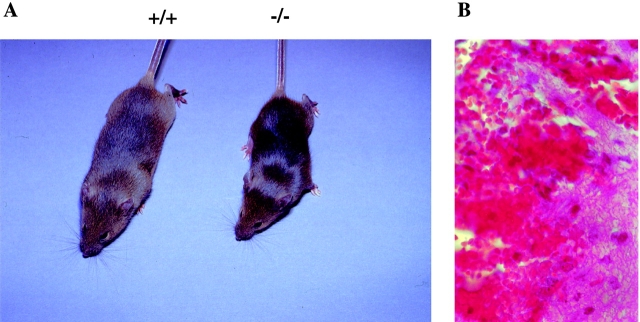

As shown in Fig. 2 A, the size of 4-wk-old Hzf −/− mice were clearly distinguishable from their wild-type littermates. Moreover, there was marked internal hemorrhaging evident primarily in the brains and gastrointestinal tracts (Fig. 2 B, and data not shown) in mutant neonates. This hemorrhaging was the likely cause of neonatal lethality. The surviving Hzf −/− mice of either sex were fertile (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Growth retardation and hemorrhage in Hzf −/− mice. (A) A Hzf −/− mouse compared with a control littermate 4 wk after birth, demonstrating slightly smaller size. (B) Transverse section of the brain of a 3-wk-old Hzf −/− mouse, demonstrating extensive hemorrhage. Original magnification: ×100.

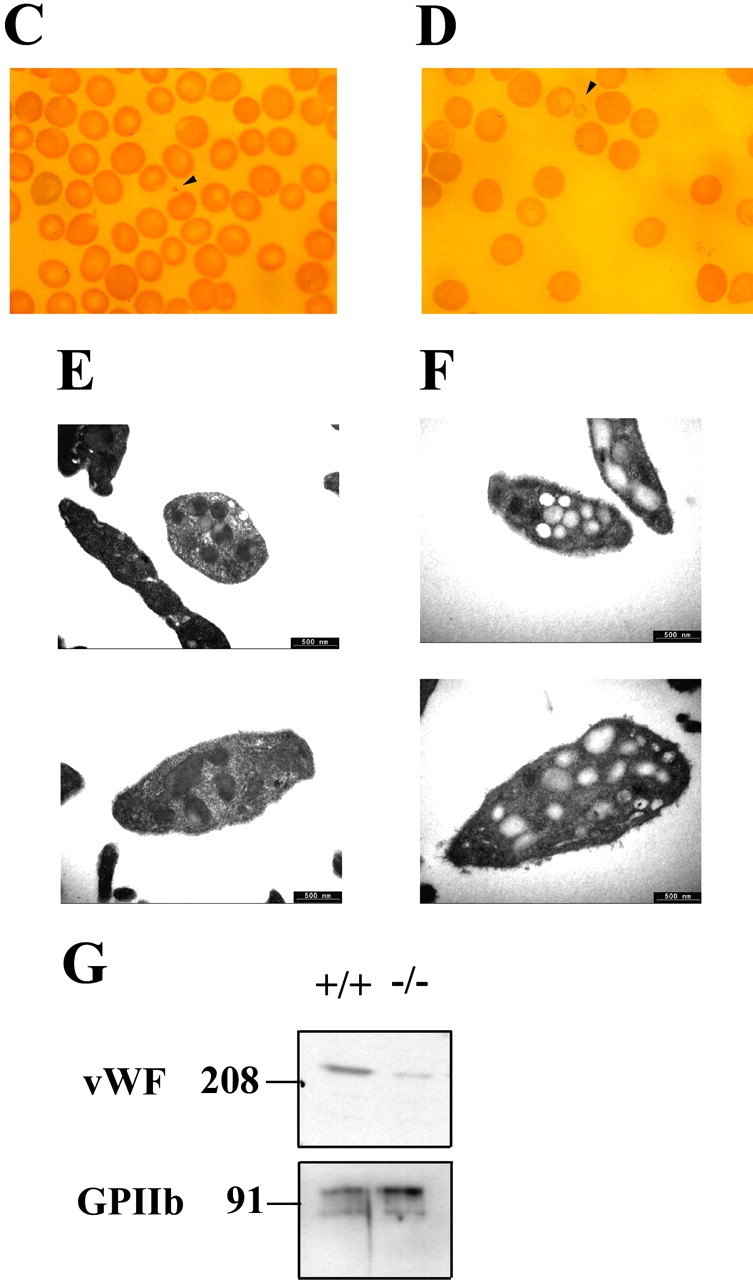

Unstable Hemostatic Plug Formation and Abnormal Platelet Morphology in Hzf −/− Mice.

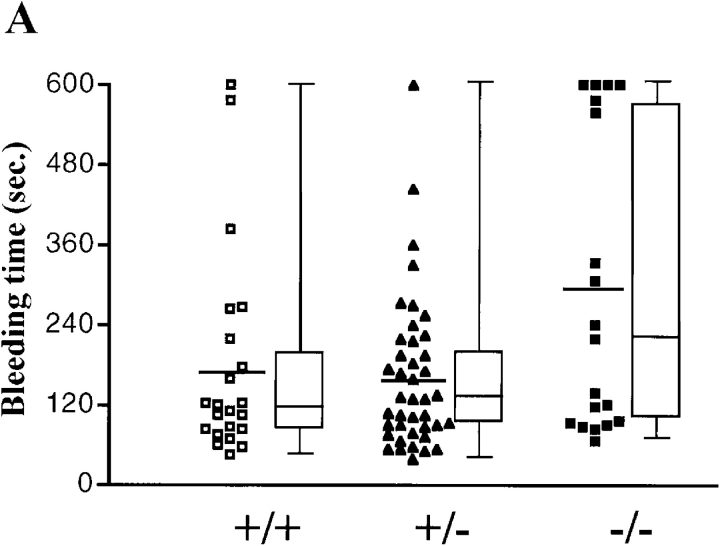

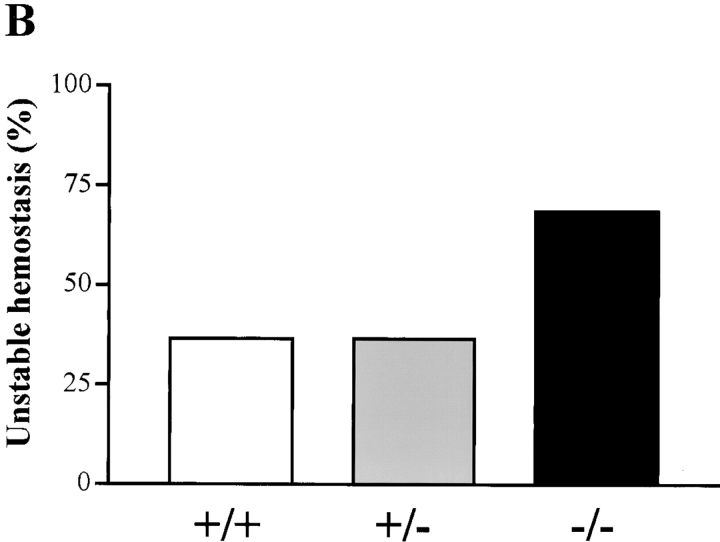

To determine whether the hemorrhaging phenotype was related to defective hemostasis in Hzf-deficient mice, we compared the bleeding times and rebleeding occurrences of Hzf +/+, Hzf +/−, and Hzf −/− mice. There were no significant differences in bleeding times when Hzf −/− mice were compared with wild-type and Hzf +/− heterozygous mice (Fig. 3 A). However, Hzf −/− mice rebled after transient hemostasis relative to the rebleeding frequency in wild-type and Hzf +/− mice (Fig. 3 B). These results indicate that Hzf-deficiency leads to unstable hemostatic plug formation in vivo.

Figure 3.

Unstable plug formation and abnormal platelet morphology in Hzf −/− mice. (A) Time taken for initial cessation of bleeding. Each symbol represents a single animal (Hzf +/+ mice, open squares, n = 22; Hzf +/− mice, closed triangles, n = 41; Hzf −/− mice, closed squares, n = 19). Bars indicate the average bleeding time for each genotype (Hzf +/+ mice, 177.0 s; Hzf +/− mice, 162.8 s; Hzf −/− mice, 290.5 s). Box and whisker graphs indicate the median, first and third quartiles, and the total range of bleeding times for each genotype. (B) Rebleeding occurrences in Hzf +/+ (white column), Hzf +/− (gray column), and Hzf −/− (black column) mice. Rebleeding occurred in 68.4% of Hzf −/− mice (n = 19) as compared with 36.4% (n = 22) of Hzf +/+ and 36.6% (n = 41) of Hzf +/− mice. (C) Peripheral blood smear from Hzf +/+ mice demonstrates a normal platelet (arrowhead). Original magnification: ×100. (D) Peripheral blood smear from Hzf −/− mice reveals a large, faintly stained platelet. Representative platelet is highlighted by an arrowhead. Original magnification: ×100. (E) Ultrastructural morphology of platelets of peripheral blood from two individual Hzf +/+ mice demonstrates normal α-granules. Scale bars, 500 nm. (F) Ultrastructural analysis of abnormal platelet morphology in Hzf −/− mice. Platelets from two individual Hzf −/− mouse exhibit numerous vacuoles with reduced α-granules. Scale bars, 500 nm. (G) Reduced platelet-vWF in Hzf −/− mice. Whole washed-platelets from control littermates and Hzf mutant mice were used to assay protein levels of vWF. Hzf −/− platelets have reduced protein levels of vWF. GPIIb, which is a GP bound to plasma membranes of platelets, was used to verify equivalent sample loading. Molecular size markers are indicated on the left in kilodaltons. This data was representative with comparable results.

The defects in hemostasis in Hzf −/− mice led us to analyze hematologic parameters in Hzf −/− mice. Surprisingly, complete hematologic profiles revealed no significant differences in platelet counts and differential counts between Hzf −/− mice and their control littermates (data not shown).

To address the defect of hemostasis in detail, we next examined the morphology of blood cells in peripheral blood smears from Hzf −/− mice. Normal platelet sizes from control mice were observed by comparison with the diameter of erythrocytes (Fig. 3 C). Large faint-colored platelets were occasionally observed in blood smears from Hzf −/− mice (Fig. 3 D). Although the frequency of these pale ghostlike platelets was low, they were never observed in peripheral blood smears from Hzf +/+ mice. To examine these morphological differences more closely, we performed ultrastructural analysis of peripheral platelets from Hzf −/− and control mice. As shown in Fig. 3 E, platelets from wild-type mice had easily identified dense α-granules. In contrast, Hzf −/− platelets had significantly reduced numbers of α-granules, with many vacuoles (Fig. 3 F; vacant frequency of α-granules, 9.4 ± 15.4 [controls] vs. 80.6 ± 12.3 [Hzf −/−], n = 11, P < 0.0001).

Numerous procoagulant substances are packed in platelet α-granules, and the release of granule contents is important for platelet function (33). vWF, one of the procoagulant substances contained in platelet α-granules, is associated with attachment of platelets onto damaged blood vessels, thereby reinforcing the stability of the plug, and activating the coagulation pathway that leads to blood clot formation (33). To investigate whether α-granules in Hzf −/− platelets contain α-granule substances, we examined the protein levels of platelet-vWF, a key GP involved in coagulation. As shown in Fig. 3 G, the levels of vWF were dramatically reduced in Hzf −/− platelets compared with that observed in platelets from wild-type mice.

Number and DNA Ploidy Levels of Megakaryocytes and Megakaryocyte Progenitors from Hzf −/− Mice.

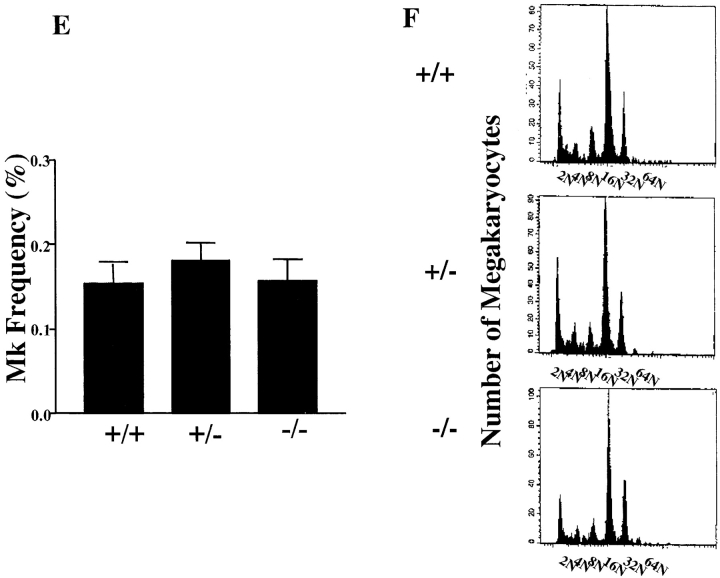

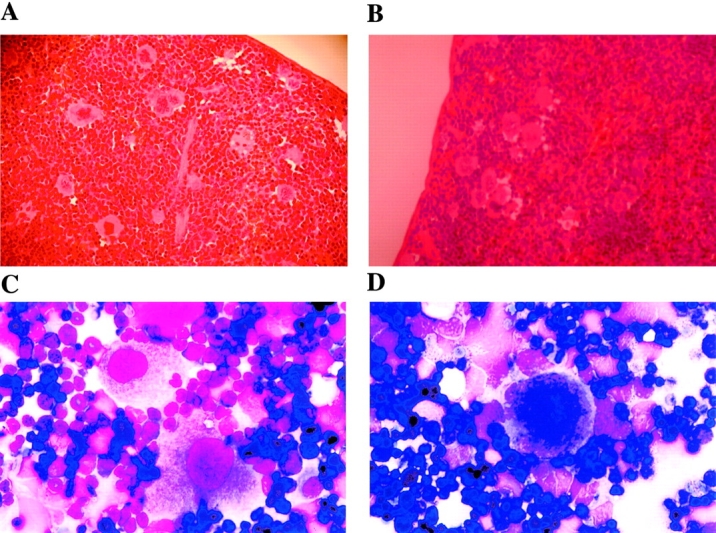

To explore in greater detail the nature of the platelet defects described above, we characterized megakaryocytes from Hzf −/− mutant mice. No differences in the numbers of megakaryocytes were observed in the spleens and bone marrows of Hzf mutant mice, as determined morphologically and by flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 4 A–E).

Figure 4.

The presence of megakaryocytes and normal aspects of megakaryocyte maturation in Hzf −/− mice. (A and B) Transverse sections through the spleens from Hzf +/+ (A) and Hzf −/− (B) mice, demonstrating the presence of megakaryocytes in each. A and B, original magnification: ×100. (C and D) Microscopic examination of bone marrow smears from Hzf +/+ (C) and Hzf −/− (D) mice, showing the presence of megakaryocytes in each. C and D, original magnification: ×100. (E) Flow cytometric analysis confirms no significant difference of megakaryocyte frequency between control and Hzf −/− mice. The proportion of megakaryocytes to bone marrow cells was performed after staining with 4A5 mAb, to murine megakaryocytes. Six mice, which were age- and sex-matched, were analyzed in each genotype with FACScan™. Results are presented as the means ±SD. (F) Representative megakaryocyte DNA ploidy in Hzf −/− mice. The proportion of cells in each ploidy class was determined by PI-staining after gated on 4A5-positive cells with FACScan™, demonstrating no effect of Hzf deficiency on endomitosis. Six mice, which were age- and sex-matched, were analyzed in each genotype. This data was representative with comparable results.

Megakaryocyte development initiates with proliferation of precursor cells. These precursor cells then undergo endomitosis, followed by cytoplasmic maturation and organization, culminating in platelet release (1). To determine whether the process of endomitosis was affected by the absence of Hzf, we performed DNA ploidy analysis on bone marrow megakaryocytes. As shown in Fig. 4 F, no significant differences in DNA ploidy patterns were observed between wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mutant mice. We next examined the levels of megakaryocyte progenitor cells (CFU-Mk) in the bone marrow of Hzf wild-type and mutant mice by plating bone marrow cells in semi-solid media in the presence of TPO/MGDF. Normal numbers of megakaryocyte progenitors were observed in Hzf-deficient mice (data not shown).

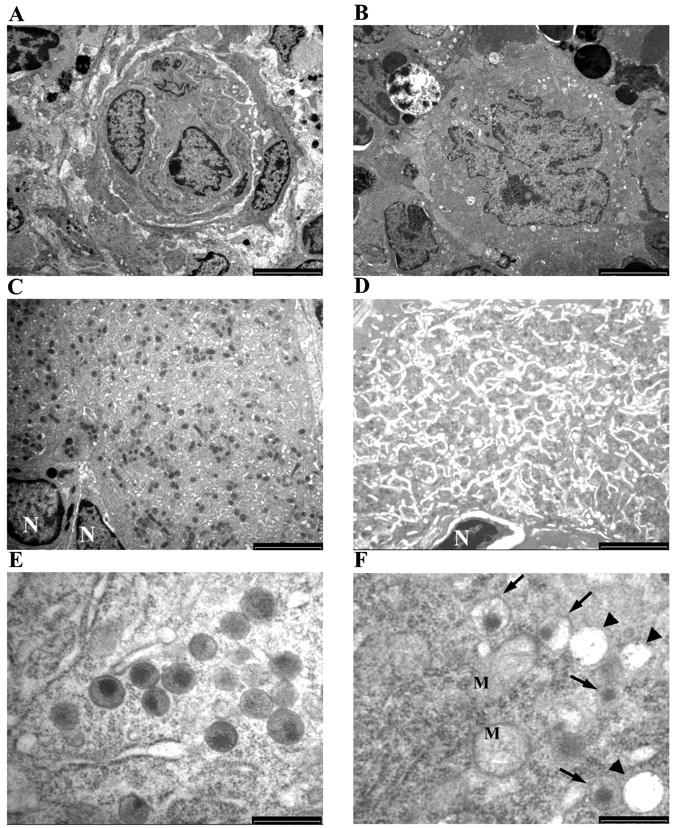

Ultrastructural Analysis of Megakaryocytic Abnormality.

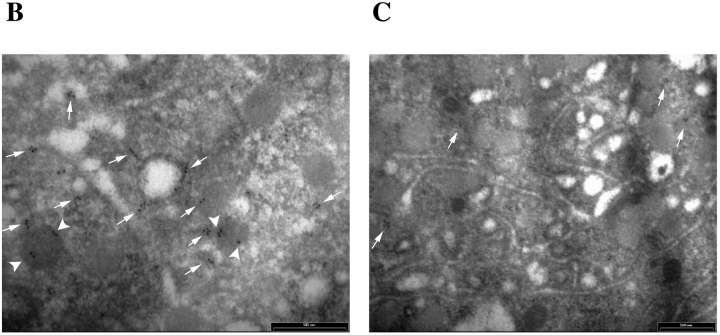

To characterize further the maturation defect in Hzf −/− mice, we performed electron microscopic analysis of megakaryocytes derived from Hzf −/− mice. As expected, megakaryocytes from both Hzf +/+ and Hzf −/− mice exhibited hyperlobulated nuclei (Fig. 5 A and B). Megakaryocytes from Hzf +/+ mice exhibited well-formed platelet fields, demarcation membrane systems, and numerous α-granules (Fig. 5 C); in contrast, Hzf −/− megakaryocytes displayed a dramatic reduction in the number of α-granules, with many vacuoles in their cytoplasm (Fig. 5 D). Furthermore, detailed ultrastructural analysis revealed that α-granules in megakaryocytes from control mice were dense, readily identifiable, and exhibited distinct zones: dense nucleoid regions and diffuse granular matrixes (Fig. 5 E). In contrast, the α-granules in Hzf −/− megakaryocytes were pale and vacant, although membranes of α-granules could be identified (Fig. 5 F). In addition, the majority of Hzf −/− α-granules were devoid of diffuse granular matrixes, although dense nucleoid regions were observed only in some α-granules in Hzf −/− megakaryocytes (Fig. 5 F).

Figure 5.

Ultrastructural analysis of megakaryocytic abnormality. (A and B) Mature megakaryocytes from the bone marrow of both Hzf +/+ (A) and Hzf −/− (B) mice exhibit hyperlobulated nuclei. A and B, scale bars, 5,000 nm. (C) Detail of the cytoplasm of the megakaryocyte shown in A. Platelet fields or territories are clearly demarcated. Many α-granules are observed. N, nuclei. Scale bar, 2,500 nm. (D) Detail of the cytoplasm of the megakaryocyte shown in B. The Hzf −/− megakaryocyte reveals reduced numbers of α-granules, with many vacuoles. N, nucleus. Scale bar, 2,500 nm. (E) Ultrastructural analysis of α-granules of the megakaryocyte from Hzf +/+ mice. Normal dense α-granules, which exhibits distinct zones: dense nucleoid regions and diffuse granular matrixes are observed. Scale bar, 500 nm. (F) Ultrastructural analysis of α-granules of the megakaryocytes from Hzf −/− mice. Some vacuoles (arrowheads) and low dense α-granules (arrows) are present in cytoplasm. M, mitochondria, in which cristae are observed. Scale bar, 500 nm.

Taken together, these data suggest that the process of endomitosis is not affected by Hzf-deficiency. However, Hzf-deficiency appears to block the process of terminal maturation of megakaryocytes, affecting the assembly of α-granule substances in α-granules of megakaryocytes.

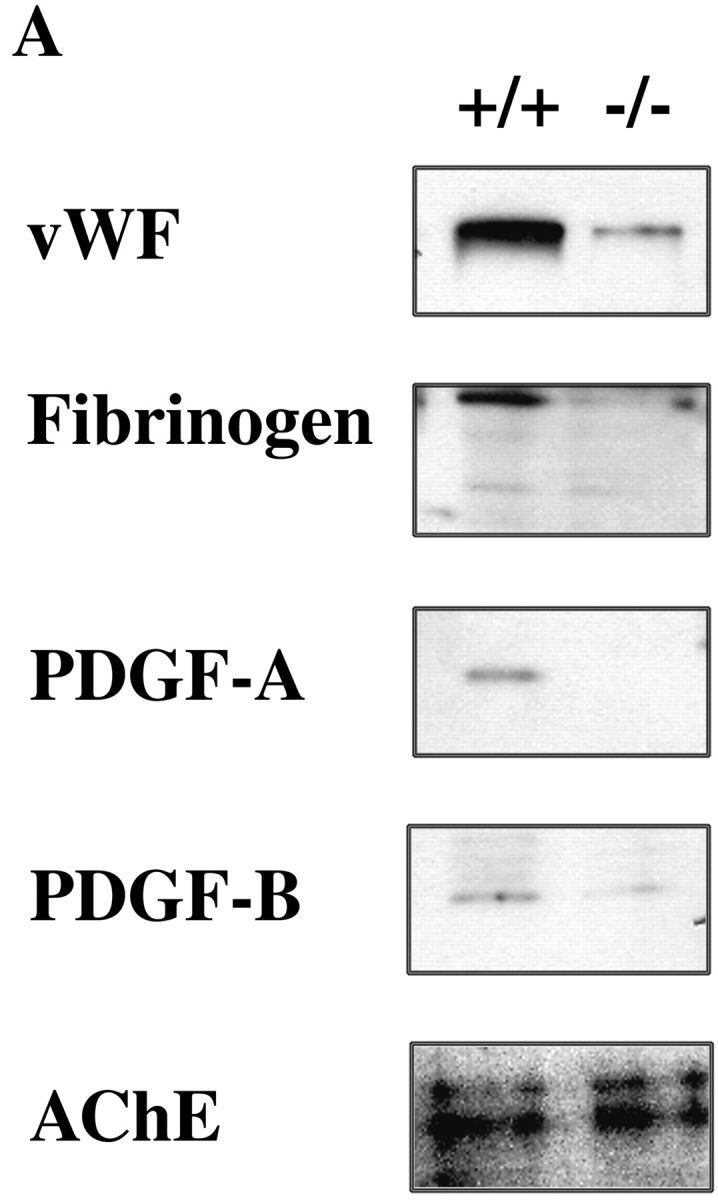

Reduced Concentrations of α-Granule Substances in Hzf −/− Megakaryocytes.

Previous biochemical and immunoelectron microscopic analyses have shown that megakaryocytic α-granules contain numerous substances essential to the coagulation system (3). To examine the effect of Hzf-deficiency on production of α-granule substances in megakaryocytes, we analyzed the levels of vWF, fibrinogen, PGDF-A, and PDGF-B by Western immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 6 A, the levels of adhesive GP, vWF and fibrinogen, were both dramatically reduced in Hzf −/− bone marrow. In addition, Hzf-deficient bone marrow had significantly decreased protein levels of PDGF-A and PDGF-B.

Figure 6.

Reduced concentrations of α-granule substances in megakaryocytes from Hzf −/− mice. (A) Western immunoblotting analysis reveals reduced levels of vWF, fibrinogen, PDGF-A, and PDGF-B from bone marrow cells in Hzf −/− mice. The AChE, a house keeping protein expressed specifically in megakaryoctes, was used to verify equivalent sample loading. This data was representative with comparable results. (B and C) Immunogold localization of PDGF-A on thin sections of megakaryocytes in the spleens of Hzf +/+(B) and Hzf −/− (C) mice. (B) Concentrated gold particles are located in the α-granules (arrowheads) and vesicles (arrows) of cytoplasm in megakaryocytes from Hzf +/+ mice. Scale bar, 500 nm. (C) A few gold particles are present on the vesicles (arrows) of cytoplasm in megakaryocytes from Hzf −/− mice. Partially empty α-granules and vacant α-granules are also observed. Scale bar, 500 nm.

To examine further the effect of Hzf deficiency on the levels of α-granule substances in megakaryocytes, we performed immunogold labeling followed by transmission electron microscopy. Using this strategy, we observed concentrated gold particles corresponding to PDGF-A in α-granules and on vesicles in the cytoplasm of Hzf +/+ megakaryocytes (Fig. 6 B; numbers of PDGF-A gold particles in Hzf +/+ α-granules: 19.8 ± 5.7%, n = 5). In contrast, PDGF-A was not detected in α-granules from Hzf −/− megakaryocytes although a few gold particles were present on vesicles (Fig. 6 C; PDGF-A gold particles in Hzf −/− α-granules: 0.8 ± 1.8%, n = 5, P = 0.001).

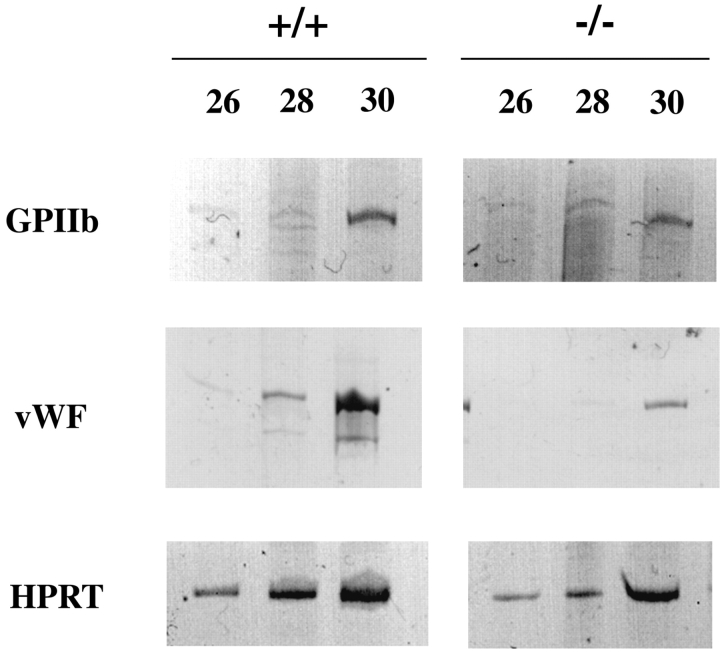

Transcript Levels of Megakaryocyte-specific Genes.

To determine whether the structural defects observed in megakaryocytes from Hzf −/− mice were the consequence of an earlier block in megakaryocyte maturation, we examined the expression of two genes associated with megakaryopoiesis (29). In this experiment, bone marrow cells from mutant and wild-type male mice were used as the source of mRNAs for comparison of expression levels of the coadhesive GP, vWF, and the cell surface receptor, GPIIb. As shown in Fig. 7 , Hzf −/− megakaryocytes expressed an equivalent level of RNA transcripts corresponding to GPIIb as Hzf +/+ cells. In contrast, transcripts corresponding to vWF gene were significantly reduced in Hzf −/− cells relative to that observed in wild-type cells.

Figure 7.

Down-regulation of megakaryocyte-specific gene expression in Hzf −/− mice. RT-PCR analysis of megakaryocyte-specific mRNAs from bone marrow cells of male Hzf +/+ and Hzf −/− mice. Expression of indicated gene expression was determined by RT-PCR with indicated number of cycles and PAGE. Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase signal was used to equivalent cDNA amounts between male wild-type and male Hzf mutant.

Discussion

We have previously identified a novel gene, Hzf, by a gene trapping strategy in ES cells (24). Hzf encodes a novel protein containing three C2H2-type zinc fingers and is predominantly expressed in megakaryocytes within the hematopoietic system. In this study, we have investigated the in vivo role of Hzf in mice using gene targeting. Hzf deficiency causes a block in the formation of α-granules in megakaryocytes, abnormal platelet morphology, and disruption of hemostasis in vivo. These findings identify Hzf as a novel regulator of megakaryopoiesis and hemostasis.

Megakaryocyte Development and α-Granule Formation in Hzf-deficient Mice.

Megakaryocytes in Hzf −/− mice were produced in normal number and appeared to undergo complete differentiation based on DNA ploidy analysis. Electronmicroscopic analysis revealed the presence of polyploid nuclei and the characteristic demarcation membrane system in megakaryocytes lacking HZF. Together, these findings suggest that Hzf-deficiency does not cause a block in the intermediate and late stages of megakaryocyte differentiation. The numbers of megakaryocyte progenitor cells were also not affected by the absence of Hzf, suggesting that Hzf is not essential for the early stages of megakaryocyte differentiation.

The electronmicroscopic and biochemical analyses revealed that platelets and megakaryocytes from Hzf −/− mice contain numerous vacuoles with reduced amount of α-granule substances. Interestingly, membranes of α-granules were observed in Hzf −/− megakaryocytes. In addition, PDGF-A was not detected in the α-granules of Hzf −/− megakaryocytes although a few gold particles were present on vesicles. Interestingly, immunoelectron microscopic analysis shows that vWF is detected on small vesicles of human cultured megakaryocytes (34). These findings suggest that Hzf is required for the synthesis of α-granule substances and/or the trafficking of these substances into α-granule bags during the process of megakaryocyte maturation.

Hzf in Platelet Morphogenesis and Hemostasis.

Most Hzf −/− mice were smaller than their wild-type littermates, presumably as a result of sustained hemorrhage during a period of rapid growth. Because the numbers of platelets in Hzf mutant mice were within normal range, HZF does not appear to impair the release of platelets from megakaryocytes. Nevertheless, circulating large, faintly stained platelets containing numerous empty vacuoles were present in the peripheral blood of Hzf −/− mice.

Platelets from Hzf −/− mice have dramatically reduced levels of the coadhesive GPs, vWF and fibrinogen. vWF and fibrinogen contribute to hemostasis by producing a platelet plug and then reinforcing the plug by converting fibrinogen to fibrin strands, inducing activation of the coagulation pathway (33, 35). It is also known that GPIb, which is a heterodimer of GPIbα and GPIbβ, has an important role in the adherence of platelets to subendothelial surfaces with binding to vWF (35–37). Indeed, vWF−/− platelets exhibit delayed adhesion to vessel walls and they failed to form thromba in arterioles in vivo (38, 39). Thus, the instability of plug formation in Hzf-deficient mice may result from a failure of platelet adhesion onto damaged blood vessel walls, a process which is mediated by the binding of vWF to GPIb.

Gray Platelet Syndrome and Hzf Deficiency.

It is of interest to note that the phenotype of the Hzf −/− mice described here resembles that observed in patients with gray platelet syndrome (GPS), a human congenital bleeding disorder (40, 41). Platelets from patients with GPS appear gray and are markedly deficient in morphologically dense α-granules and in the α-granule substances, β-thromboglobulin, fibrinogen, vWF, and PDGF (42–45). These similarities raise the intriguing possibility that GPS may be associated with defects in the biochemical pathway defined by HZF.

Gene Regulation by Hzf.

The generation of mice with targeted mutations in specific genes has greatly enhanced our understanding of megakaryocyte differentiation. RNA transcripts for the vWF gene were significantly reduced in bone marrow cells derived from Hzf −/− mice. Thus, these results suggest either that Hzf directly regulates the expression of vwf and/or that delayed or incomplete maturation of megakaryocytes as a result of Hzf deficiency is reflected in decreased expression levels of vwf transcripts.

Taken together, this data suggests that Hzf plays an essential role in hemostasis in vivo through its direct or indirect regulation of the levels of at least one molecule, vWF known to be involved in plug formation through the adhesion of platelets to endothelial cells. We conclude that the defects in Hzf-deficient mice reflect, at least in part, a direct or indirect role for Hzf in vWF regulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sandra Tondat for ES cell aggregations, Lynda Doughty for DNA sequences, Ken Harpal for sectioning of tissues, Shirly Vesely, and George Cheong for preparation of reagents, Dr. Pascale Marchot for information on AChE, Drs. Denisa D. Wagner, Yoshiyasu Aoki, and anonymous reviewers for giving valuable comments, Lawrence Ng, Drs. Jerry Ware, Akira Suzuki, Ryuichi Sakai, Takehiro Kawano, Seiji Tadokoro, Sanford J. Shattil, and Ramesh A. Shivdasani for technical advice, Bev Bessey for administrative support, and Drs. Mira Puri, Cindy Todoroff, and Kazunobu Tachibana for reviewing the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute of Canada and the Terry Fox Cancer Foundation (to A. Bernstein) and in part by grants p30CA21765 and p01CA20180 from the National Cancer Institute, U.S. Public Health Service, Department of Health and Human Services, and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (to C.W. Jackson). Y. Kimura was supported by the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research.

A. Hart's present address is The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, PO Royal Melbourne Hospital, VIC 3050, Australia.

X.-L. Pang's present address is Arius Research, Inc., Mississauga, Ontario, L4V 1N3, Canada.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: AChE, acetylcholinesterase; ES, embryonic stem; GP, glycoprotein; GPS, gray platelet syndrome; Hzf, hematopoietic zinc finger; IRES, internal ribosome-entry site; MGDF, megakaryocyte growth and development factor; neo, neomycin resistant gene; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; TPO, thrombopoietin; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

References

- 1.Zuker-Franklin, D. 1989. Megakaryocytes and platelets. In Atlas of Blood Cells: Function and Pathology. D. Zuker-Franklin, M.F. Greaves, C.E. Grossi, and A.M. Marmont, editors. Lea and Feiger, Philadelphia. pp. 621–693.

- 2.Jackson, C.W., L.K. Brown, B.C. Somerville, S.A. Lyles, and A.T. Look. 1984. Two-color flow cytometric measurement of DNA distributions of rat megakaryocytes in unfixed, unfractionated marrow cell suspensions. Blood. 63:768–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burstein, S.A., and J. Breton-Gorius. 1995. Megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation. 5th ed. In Williams Hematology. E. Beutler, M.A. Litchtman, B.S. Coller, and T.J. Kipps, editors. McGraw-Hill, Inc., New York, NY. 1149–1160.

- 4.Greenberg, S.M., D.J. Kuter, and R.D. Rosenberg. 1987. In vitro stimulation of megakaryocyte maturation by megakaryocyte stimulatory factor. J. Biol. Chem. 262:3269–3277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shivdasani, R.A., M.F. Rosenblatt, D. Zucker-Franklin, C.W. Jackson, P. Hunt, C.J.M. Saris, and S.H. Orkin. 1995. Transcription factor NF-E2 is required for platelet formation independent of the actions of thrombopoietin/MGDF in megakaryocyte development. Cell. 81:695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shavit, J.A., H. Motohashi, K. Onodera, J. Akasaka, M. Yamamoto, and J.D. Engel. 1998. Impaired megakaryopoiesis and behavioral defects in mafG-null mutant mice. Genes Dev. 12:2164–2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shivdasani, R.A., Y. Fujiwara, M.A. McDevitt, and S.H. Orkin. 1997. A lineage-selective knockout establishes the critical role of transcription factor GATA-1 in megakaryocyte growth and platelet development. EMBO J. 16:3965–3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hart, A., F. Melet, P. Grossfeld, K. Chien, C. Jones, A. Tunnacliffe, R. Favier, and A. Bernstein. 2000. Fli-1 is required for murine vascular and megakaryocytic development and is hemizygously deleted in patients with thrombocytopenia. Immunity. 13:167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blank, V., and N.C. Andrews. 1997. The Maf transcription factors: Regulators of differentiation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:437–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Motohashi, H., J.A. Shavit, K. Igarashi, M. Yamamoto, and J.D. Engel. 1997. The world according to Maf. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:2953–2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Souyri, M., I. Vigon, J.-F. Penciolelli, J.-M. Heard, P. Tambourin, and F. Wendling. 1990. A putative truncated cytokine receptor gene transduced by the myeloproliferative leukemia virus immortalizes hematopoietic progenitors. Cell. 63:1137–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartley, T.D., J. Bogenberger, P. Hunt, Y.S. Li, H.S. Lu, F. Martin, M.S. Chang, B. Samal, J.L. Nichol, S. Swift, et al. 1994. Identification and cloning of a megakaryocyte growth and development factor that is a ligand for the cytokine receptor Mpl. Cell. 77:1117–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Sauvage, F.J., P.E. Hass, S.D. Spencer, B.E. Malloy, A.L. Gurney, S.A. Spencer, W.C. Darbonne, W.J. Henzel, S.C. Wong, W.-J. Kuang, et al. 1994. Stimulation of megakaryocytopoiesis and thrombopoiesis by the c-Mpl ligand. Nature. 369:533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaushansky, K., S. Lok, R.D. Holly, V.C. Broudy, N. Lin, M.C. Bailey, J.W. Forstrom, M.M. Buddle, P.J. Oort, F.S. Hagen, G.J. Roth, T. Papayannopoulou, and D.C. Foster. 1994. Promotion of megakaryocyte progenitor expansion and differentiation by the c-Mpl ligand thrombopoietin. Nature. 369:568–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuter, D.J., D.L. Beeler, and R.D. Rosenberg. 1994. The purification of megapoietin: a physiological regulator of megakaryocyte growth and platelet production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:11104–11108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lok, S., K. Kaushansky, R.D. Holly, J.L. Kuijper, C.E. Lofton-Day, P.J. Oort, F.J. Grant, M.D. Heipel, S.K. Burkhead, J.M. Kramer, et al. 1994. Cloning and expression of murine thrombopoietin cDNA and stimulation of platelet production in vivo. Nature. 369:565–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wendling, F., E. Maraskovsky, N. Debili, C. Florindo, M. Teepe, M. Titeux, N. Methia, J. Breton-Gorius, D. Cosman, and W. Vainchenker. 1994. c-Mpl ligand is a humoral regulator of megakaryocytopoiesis. Nature. 369:571–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato, T., K. Ogami, Y. Shimada, A. Iwamatsu, Y. Sohma, H. Akahori, K. Horie, A. Kokubo, Y. Kudo, and E. Maeda. 1995. Purification and characterization of thrombopoietin. J. Biochem. 118:229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi, E.S., M.M. Hokom, J.L. Chen, J. Skrine, J. Faust, J. Nichol, and P. Hunt. 1996. The role of megakaryocyte growth and development factor in terminal stages of thrombopoiesis. Br. J. Haematol. 95:227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gurney, A.L., K. Carver-Moore, F.J. de Sauvage, and M.W. Moore. 1994. Thrombocytopenia in c-mpl-deficient mice. Science. 265:1445–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander, W.S., A.W. Roberts, N.A. Nicola, R. Li, and D. Metcalf. 1996. Deficiencies in progenitor cells of multiple hematopoietic lineages and defective megakaryocytopoiesis in mice lacking the thrombopoietic receptor c-Mpl. Blood. 87:2162–2170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Sauvage, F.J., K. Carver-Moore, S.-M. Luoh, A. Ryan, M. Dowd, D.L. Eaton, and M.W. Moore. 1996. Physiological regulation of early and late stages of megakaryocytopoiesis by thrombopoietin. J. Exp. Med. 183:651–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanford, W.L., G. Caruana, K.A. Vallis, M. Inamdar, M. Hidaka, V.L. Bautch, and A. Bernstein. 1998. Expression trapping: identification of novel genes expressed in hematopoietic and endothelial lineages by gene trapping in ES cells. Blood. 92:4622–4631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hidaka, M., G. Caruana, W.L. Stanford, M. Sam, P.H. Correll, and A. Bernstein. 2000. Gene trapping of two novel genes, Hzf and Hhl, expressed in hematopoietic cells. Mech. Dev. 90:3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nieswandt, B., B. Echtenacher, F.-P. Wachs, J. Schroder, J.E. Gessner, R.E. Schmidt, G.E. Grau, and D.N. Mannel. 1999. Acute systemic reaction and lung alterations induced by an antiplatelet integrin gpIIb/IIIa antibody in mice. Blood. 94:684–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dejana, E., A. Quintana, A. Callioni, and G. de Gaetano. 1979. Bleeding time in laboratory animals. III - Do tail bleeding times in rats only measure a platelet defect? (the aspirin puzzle). Thromb. Res. 15:199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Law, D.A., F.R. DeGuzman, P. Heiser, K. Ministri-Madrid, N. Killeen, and D.R. Phillips. 1999. Integrin cytoplasmic tyrosine motif is required for outside-in αIIbβ3 signalling and platelet function. Nature. 401:808–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnold, J.T., N.C. Daw, P.E. Stenberg, D. Jayawardene, D.K. Srivastava, and C.W. Jackson. 1997. A single injection of pegylated murine megakaryocyte growth and development factor (MGDF) into mice is sufficient to produce a profound stimulation of megakaryocyte frequency, size, and ploidization. Blood. 89:823–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vyas, P., K. Ault, C.W. Jackson, S.H. Orkin, and R.A. Shivdasani. 1999. Consequences of GATA-1 deficiency in megakaryocytes and platelets. Blood. 93:2867–2875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berger, G., J.M. Masse, and E.M. Cramer. 1996. α-granule membrane mirrors the platelet plasma membrane and contains the glycoproteins Ib, IX, and V. Blood. 87:1385–1395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimura, Y., K. Yamada, T. Sakai, K. Mishima, H. Nishimura, Y. Matsumoto, M. Singh, and Y. Yoshikai. 1998. The regulatory role of heat shock protein 70-reactive CD4+ T cells during rat listeriosis. Int. Immunol. 10:117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fennie, C., J. Cheng, D. Dowbenko, P. Young, and L.A. Lasky. 1995. CD34+ endothelial cell lines derived from murine yolk sac induce the proliferation and differentiation of yolk sac CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 86:4454–4467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ware, J.A., and B.S. Coller. 1995. Platelet morphology, biochemistry, and function. In Williams Hematology. E. Beutler, M.A. Litchtman, B.S. Coller, and T.J. Kipps, editors. McGraw-Hill, Inc., New York, NY. 1161–1201.

- 34.Cramer, E.M., W. Vainchenker, G. Vinci, J. Guichard, and J. Breton-Gorius. 1985. Gray platelet syndrome: immunoelectron microscopic localization of fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor in platelets and megakaryocytes. Blood. 66:1309–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savage, B., E. Saldivar, and Z.M. Ruggeri. 1996. Initiation of platelet adhesion by arrest onto fibrinogen or translocation on von Willebrand factor. Cell. 84:289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakariassen, K.S., P.M. Nievelstein, B.S. Coller, and J.J. Sixma. 1986. The role of platelet membrane glycoproteins Ib and IIb-IIIa in platelet adherence to human artery subendothelium. Br. J. Haematol. 63:681–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parker, R.I., and H.R. Gralnick. 1987. Fibrin monomer induces binding of endogenous platelet von Willebrand factor to the glycocalicin portion of platelet glycoprotein Ib. Blood. 70:1589–1594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denis, C., N. Methia, P.S. Frenette, H. Rayburn, M. Ullman-Cullere, R.O. Hynes, and D.D. Wagner. 1998. A mouse model of severe von Willebrand disease: defects in hemostasis and thrombosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:9524–9529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ni, H., C.V. Denis, S. Subbarao, J.L. Degen, T.N. Sato, R.O. Hynes, and D.D. Wagner. 2000. Persistence of platelet thrombus formation in arterioles of mice lacking both von Willebrand factor and fibrinogen. J. Clin. Invest. 106:385–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raccuglia, G. 1971. Gray platelet syndrome: a variety of qualitative platelet disorder. Am. J. Med. 51:818–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White, J.G. 1979. Ultrastructural studies of the gray platelet syndrome. Am. J. Pathol. 95:445–462. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerrard, J.M., D.R. Phillips, G.H. Rao, E.F. Plow, D.A. Walz, R. Ross, L.A. Harker, and J.G. White. 1980. Biochemical studies of two patients with the gray platelet syndrome. Selective deficiency of platelet α granules. J. Clin. Invest. 66:102–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levy-Toledano, S., J.P. Caen, J. Breton-Gorius, F. Rendu, C. Cywiner-Golenzer, E. Dupuy, Y. Legrand, and J. Maclouf. 1981. Gray platelet syndrome: α-granule deficiency: its influence on platelet function. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 98:831–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nurden, A.T., T.J. Kunicki, D. Dupuis, C. Soria, and J.P. Caen. 1982. Specific protein and glycoprotein deficiencies in platelets isolated from two patients with the gray platelet syndrome. Blood. 59:709–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berndt, M.C., P.A. Castaldi, S. Gordon, H. Halley, and V.J. McPherson. 1983. Morphological and biochemical confirmation of gray platelet syndrome in two siblings. Aust. N.Z.J. Med. 13:387–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]