Abstract

Maintenance of pancreatic β-cell mass depends on extracellular stimuli that promote survival and proliferation. In the islet, these stimuli come from the β-cell microenvironment and include extracellular matrix deposited by associated vascular endothelial cells. Fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 (FGFR1) has recently been implicated as a signaling pathway that is important for normal β-cell function. We would like to understand how extracellular matrix and FGFR1 signaling interact to promote β-cell survival and proliferation. To examine β-cell-specific receptor responses, we created lentiviral vectors with rat insulin promoter-driven expression of Venus fluorescent protein-tagged full-length (R1βv) and kinase-deficient (KDR1βv) FGFR1. Significant FGF-1-dependent activation of ERK1/2 was observed in βTC3 cells, dispersed β-cells, and β-cells in intact islets. This response was enhanced by R1βv expression and reduced by KDR1βv expression. Plating-dispersed β-cells on collagen type IV resulted in enhanced expression of endogenous FGFR1 that was associated with sustained activation of ERK1/2. Conversely, plating cells on laminin reduced expression of FGFR1, and this reduction was associated with transient activation of ERK1/2. Addition of neutralizing antibodies to inhibit β-cell attachment to laminin via α6-integrin increased high-affinity FGF-1-binding at the plasma membrane and resulted in sustained ERK1/2 activity similar to cells plated on collagen type IV. These data show that the FGF-stimulated β-cell response is negatively affected by α6-integrin binding to laminin and suggest regulation associated with vascular endothelial cell remodeling.

FIBROBLAST GROWTH FACTORS (FGFs) are a family of 23 structurally related, heparin-binding polypeptides (1). Signaling is mediated at the cell surface by ligand binding to low-affinity, high-capacity heparan sulfate proteoglycans and high-affinity, low-capacity tyrosine kinase receptors [fibroblast growth factor receptors 1–4 (FGFR1–4)]. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans act as a reservoir for FGF, thereby protecting it from degradation, as well as facilitating and modulating ligand binding to the FGFRs (2). Alternative splicing of FGFR1–3 mRNA results in receptor variants that exhibit distinct ligand-binding and -signaling properties (1,3). Each FGF and FGFR shows restricted, albeit overlapping, spatial and temporal expression patterns, suggesting specificity yet redundancy in this signaling family (4).

FGFs and FGFRs are expressed in embryonic pancreas (5,6,7) and adult islets (8,9). Mice expressing dominant-negative FGFR1c driven by an early pancreas transcription factor promoter (Ipf1/Pdx1) develop diabetes with age resulting from impaired expression of glucose transporter 2 and increased proinsulin content (9). Similarly, endogenous FGFR1 expression is regulated in β-cells by the Ipf1/Pdx1 transcription factor and dominant-negative expression of either Ipf1/Pdx1 or the receptor itself results in down-regulation of prohormone-convertase-1/3 and -2 (PC1/3 and 2) (9,10). FGF-21, a ligand with unknown receptor specificity, stimulates activation of ERK1/2 and Akt1 in the INS-1 cells and isolated islets (11). This activation increased insulin mRNA and survival during glucose- and lipotoxicity. These studies together suggest a role for FGFR1 in maintaining insulin production and enhancing β-cell survival during heavy glucose load, processes relevant to the progression of type 2 diabetes.

Growth factor-induced responses (proliferation, migration, survival) are often dependent on integrin binding to the extracellular matrix (ECM). This dependence is well characterized for FGF-induced angiogenesis, with numerous studies demonstrating blockade of blood vessel formation by disrupting integrin (αvβ3) attachment (12). Pancreatic islet ECM is mainly deposited by associated endothelial cells (13,14) and is mainly composed of collagen type IV, laminin, and fibronectin (15,16,17). The ECM is degraded during islet isolation by collagenase digestion of the pancreas (14), and it has been argued that interaction with ECM during culture enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and reduces apoptosis (18,19,20). Because endothelial cell ECM is modified during the development of type 2 diabetes, particularly by advanced glycation end products (AGEs) (21), it is critical to understand how the FGFR1 response is modulated as the cell microenvironment is altered.

In the present study we confirm FGFR1 activity in the βTC3 cell line and isolated murine pancreatic islets. By using β-cell-specific expression of fluorescent-protein tagged full-length (R1βv) and kinase-deficient (KDR1βv) receptor-1 isoforms, we demonstrate FGF-1-stimulated ERK1/2 responses in β-cells. We also demonstrate that β-cells grown on collagen type IV matrix express greater levels of FGFR1 protein, which correlates with sustained activation of ERK1/2. Conversely, β-cells grown on laminin matrix exhibit reduced receptor protein expression and only a transient activation of ERK1/2, suggesting the microenvironment is a key regulator of FGFR1 function and signaling.

RESULTS

βTC3 Cells and Fluorescent Protein-Tagged FGFR1 Isoforms

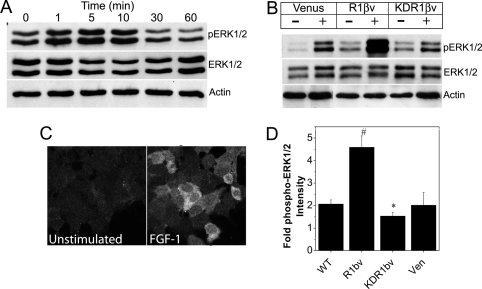

To characterize a cell line translational to islet β-cells, we first confirmed expression of FGFR1 mRNA and protein, as well as FGF-1-induced activation of downstream docking protein FRS2 in the murine insulin-secreting βTC3 cell line (supplemental Fig. S1, published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org). We also examined activation of ERK1/2 (p44/42 MAPK) because FRS2 signaling links FGFR to the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway (22) (Fig. 1). Transient phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was observed in βTC3 cells that peaked at 5–10 min stimulation (Fig. 1A). In contrast to previous studies, however, we did not observe activation of Akt (data not shown) (11). Subsequently, we measured the ERK1/2 response in βTC3 cells expressing fluorescent protein-tagged full-length (R1βv) and kinase-deficient (KDR1βv) FGFR1. Receptor isoforms of appropriate molecular weight were identified that translocated to the plasma membrane (supplemental Fig. S2). Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was significantly enhanced in R1βv cells compared with control Venus-expressing cells, and this effect was suppressed in KDR1βv cells (Fig. 1B). We also observed significant increases in phospho-ERK1/2-associated immunofluorescence in FGF-1-stimulated cells (Fig. 1C). Compared with unstimulated control cells, FGF-1 induced a 2-fold increase in phospho-ERK1/2-associated immunofluorescence in wild-type (WT) βTC3 cells (Fig. 1D). This response was significantly enhanced in R1βv cells and reduced in KDR1βv cells (4.5- and 1.5-fold, respectively). Venus-expressing cell activity was similar to WT βTC3 (2-fold). These data together are consistent with FGFR1-dependent activation of ERK1/2 in βTC3 cells and confirm the predicted biological function of the receptor constructs. These data also suggest that by pairing phospho-ERK1/2 immunofluorescence detection with rat insulin promoter-driven expression of the constructs, we can measure FGF-1-induced ERK1/2 activation in β-cells of intact islets.

Figure 1.

FGF-1-Induced ERK1/2 Phosphorylation in βTC3 Cells Is Enhanced by R1βv Expression and Reduced by KDR1βv Expression

A, Western immunoblotting of βTC3 whole-cell lysates (10 μg/lane) stimulated with FGF-1 (10 ng/ml; times as indicated) using antibodies recognizing phospho-ERK1/2 (top), ERK1/2 (middle), and β-actin (loading control, bottom). B, Western immunoblotting of whole-cell lysates (10 μg/lane) from βTC3 cells expressing Venus, R1βv, or KDR1βv in the absence (−) or presence (+) of FGF-1 (10 ng/ml for 10 min) using antibodies to detect phosphoERK1/2, ERK1/2, and β-actin. Representative blots are shown. C, Immunofluorescent detection of phospho-ERK1/2 in WT βTC3 cells in the absence (left) or presence (right) of FGF-1. D, Fold change in phospho-ERK1/2 immunofluorescence for cells stimulated with FGF-1 (as shown in panel C) compared with nonstimulated control cells. Data were collected from five fields of view for each sample and are plotted as the mean fold increase in phospho-ERK1/2 intensity compared with control cells ± sem from four independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; #, P < 0.02 (Student’s two-tailed t test). Ven, Venus.

FGFR1-Dependent ERK1/2 Activation in Islet β-Cells

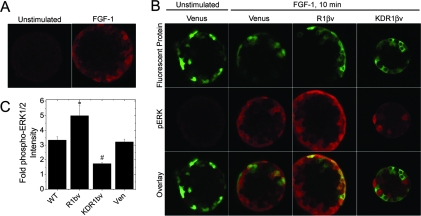

Previous studies report ERK1/2 phosphorylation in pancreatic islet lysates after stimulation with FGF-21 (11). FGF-21 has no significant binding affinity to any FGFR isoform, making the molecular mechanism of this response unclear (23). Furthermore, islets contain a number of non-β-cell types including vascular endothelial and nerve cells as well as other endocrine cells, making analysis of lysates only suggestive of a β-cell response. To focus our studies in a cell-specific manner, we examined the phospho-ERK1/2 response using immunofluorescence detection (Fig. 2). Islets stimulated with FGF-1 (10 min) showed significant phospho-ERK1/2 immunofluorescence at the periphery, consistent with a FGF-1-dependent response limited by diffusion of ligand into the tissue (Fig. 2A). To specifically examine FGFR1 signaling in β-cells, islets were infected with lentivirus to express R1βv, KDR1βv, or control Venus protein (Fig. 2B). The rat insulin promoter resulted in construct expression as a mosaic in insulin-positive cells only (supplemental Fig. S3). Venus protein was localized throughout individual cells of the islet in contrast to R1βv and KDR1βv, which were excluded from nuclei (Fig. 2B, top row). In the absence of FGF-1, phospho-ERK1/2 immunofluorescence in Venus-expressing islets was negligible and similar to unstimulated WT islets [compare Fig. 2A (left) vs. Fig. 2B, Venus (middle left)]. Unstimulated R1βv and KDR1βv islets also exhibited low phospho-ERK1/2 immunofluorescence consistent with neither construct affecting baseline phospho-ERK1/2 activity (data not shown). FGF-1 increased phospho-ERK1/2 immunofluorescence in both Venus-expressing and nonexpressing cells near the periphery of the islet (Fig. 2B, Venus+FGF-1 Overlay). Compared with nonexpressing cells within the same islet, the phospho-ERK1/2 response was enhanced in R1βv-expressing cells (Fig. 2B, R1βv+FGF-1 Overlay) and reduced in KDR1βv-expressing cells (Fig. 2B, KDR1βv+FGF-1 Overlay). To better determine changes in ERK1/2 activity, the associated phospho-ERK1/2 immunofluorescence intensity was normalized to cells expressing the same construct in unstimulated islets (Fig. 2C). Similar to responses identified in βTC3 (Fig. 1C), FGF-1 stimulation induced a significant increase in phospho-ERK1/2 in WT islet β-cells (3-fold) that was enhanced by R1βv expression (5-fold), inhibited by KDR1βv expression (1.5 fold), and unaffected by Venus expression (3-fold). These data are consistent with β-cell-specific FGF-1/FGFR1 signaling in islets.

Figure 2.

FGFR1 Enhances ERK1/2 Activation in β-Cells of Intact Islets

A, Phospho-ERK1/2 immunofluorescence of unstimulated or FGF-1 stimulated (10 ng/ml for 10 min) WT islets. B, Islets expressing β-cell specific Venus, R1βv, or KDR1β stimulated with FGF-1 (10 ng/ml for 10 min) and immunostained for phospho-ERK1/2. Representative images of Venus protein expression (top), phospho-ERK1/2 immunofluorescence (middle), and the overlay (bottom) are shown for islets expressing Venus, R1βv, and KDR1βv (as indicated). C, Fold change in phospho-ERK1/2 immunofluorescence in construct expressing β-cells. Data are plotted as mean fold change phospho-ERK1/2 intensity (FGF-1 treatment compared with nonstimulated islets) ± sem for WT, R1βv-, KDR1βv-, and Venus-expressing islets. The experiment was performed in triplicate, and intensity measurements were acquired from five to seven islets per treatment. *, P < 0.05; #, P < 0.02 (Student’s two-tailed t test). Ven, Venus.

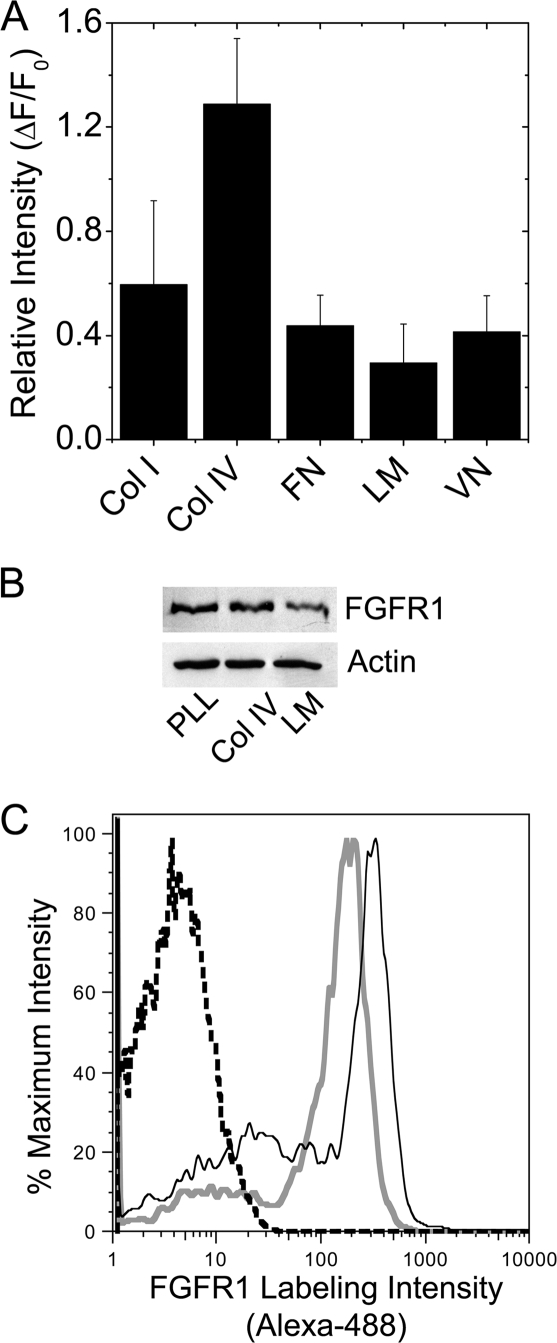

Temporal FGF-1-Stimulated ERK1/2 Responses Depend upon Specific ECM Attachment

The ECM of β-cells is deposited mainly by vascular endothelial cells and is likely remodeled throughout the lifetime of a β-cell. To examine how the β-cell FGFR1 response is modulated by changes in the microenvironment, we first measured FGFR1 protein expression in βTC3 cells plated on different ECMs (Fig. 3). FGFR1 immunofluorescence was brightest in cells plated on type IV collagen and dimmest in cells plated on laminin (Fig. 3A). Reduced expression of FGFR1 in cells plated on laminin was similarly observed by Western immunoblotting (Fig. 3B). To determine whether modulation of overall protein translates to receptor presentation, we examined receptor levels at the cell surface by flow cytometry using an N-terminal specific monoclonal antibody (Fig. 3C). Consistent with the trends observed by immunofluorescence and Western immunoblot, FGFR1 surface labeling intensity on laminin plated βTC3 cells (Fig. 3C, solid gray line) was consistently lower than cells plated on collagen type IV (solid black line). These data demonstrate that ECM modulates FGFR1 expression at the plasma membrane in βTC3 cells.

Figure 3.

βTC3 cell FGFR1 Expression Is Reduced by Attachment to Laminin

A, FGFR1-associated immunofluorescence in WT βTC3 cells plated overnight on collagen type I (Col I), collagen type IV (Col IV), fibronectin (FN), laminin (LM), and vitronectin (VN) (n = 4). B, Western immunoblotting of whole-cell lysates (5 μg/lane) from βTC3 cells plated overnight on poly-l-lysine (PLL), Col IV, and LM using an antibody to detect the N terminus of FGFR1 (3472, Cell Signaling Technology). β-Actin is shown as a loading control (representative blot is shown; n = 3). C, Enhanced cell surface labeling was detected in βTC3 cells plated on Col IV (solid black line) vs. LM (solid gray line) by flow cytometry using an antibody to detect the N terminus of FGFR1 (M2F12, QED Biosciences). Unstained control cell intensity is indicated by the black dashed line (representative plot shown; n = 5)

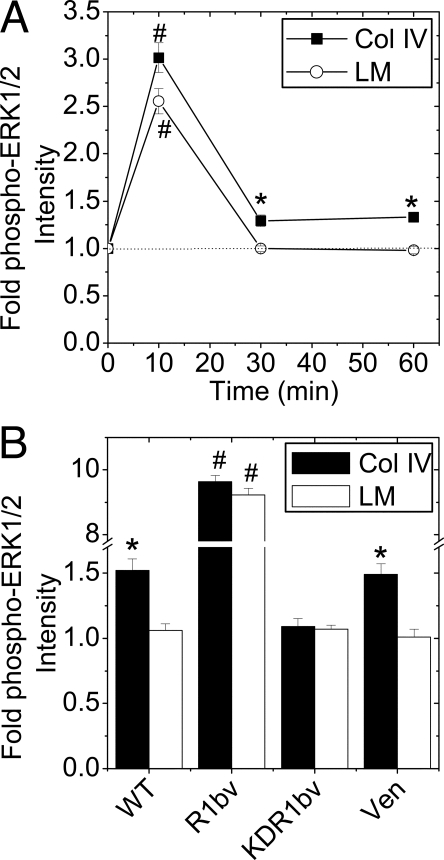

The FGF-1-induced temporal phospho-ERK1/2 response was also measured in βTC3 (Fig. 4). Cells plated on collagen type IV exhibited a maximal 3-fold phospho-ERK1/2 response at 10 min that decreased to a statistically significant steady state of 1.3-fold above baseline by 30 min (Fig. 4A; -▪-). The response in cells cultured on laminin was maximal at 10 min but returned to baseline levels by 30 min (Fig. 3B, -○-). To confirm that sustained ERK1/2 phosphorylation in cells plated on collagen type IV was FGFR1 dependent, the response was examined in WT, R1βv, KDR1βv, and Venus βTC3 cells at 30 min of FGF-1 stimulation (Fig. 4B). Consistent with the temporal study, WT cells exhibited a significantly larger phospho-ERK1/2 response on collagen type IV than on laminin (Fig. 4B; WT). Expression of R1βv significantly increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation on both substrates, consistent with elevated receptor levels overcoming ECM modulation (R1βv). KDR1βv expression significantly inhibited the collagen type IV response (KDR1βv) whereas Venus control cells exhibited a phospho-ERK1/2 response similar to WT cells.

Figure 4.

FGF-1 Stimulated βTC3 Cell ERK1/2 Phosphorylation Is Altered by ECM Attachment

A, FGF-1-induced phospho-ERK1/2 immunofluorescence of WT cells grown on collagen type IV or laminin. Data are plotted as fold change in phospho-ERK1/2 immunofluorescence intensity compared with nonstimulated control (time 0) ± sem for three to four independent experiments (minimum of 70 cells analyzed per time point). The dotted line shown at 1-fold change phospho-ERK1/2 intensity is shown to assist data interpretation. B, Similar experiment as panel A. including R1βv-, KDR1βv-, and Venus-expressing cells after 30 min of FGF-1 stimulation (10 ng/ml). Data are plotted as fold change in intensity compared with unstimulated control cells ± sem from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; #, P < 0.02 (Student’s two-tailed t test). Col, Collagen; LM, laminin;Ven, Venus.

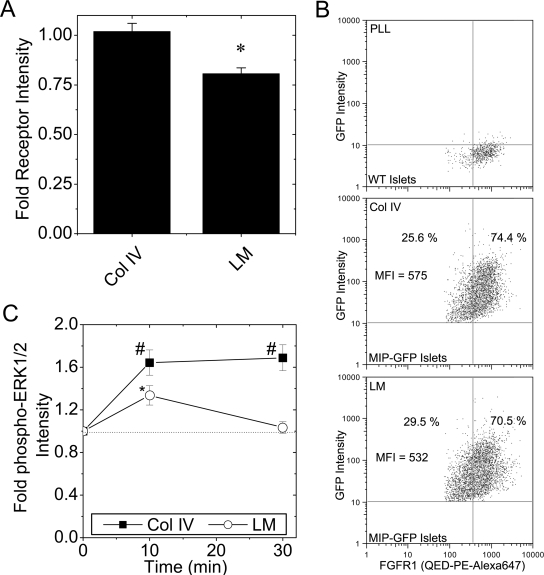

ECM within islets is affected by a number of cell types including other endocrine and endothelial cells. Therefore, to measure the direct effect of ECM on β-cell FGFR1, islets were dispersed to single cells before plating on collagen type IV or laminin (Fig. 5). All immunofluorescence studies included insulin colabeling to positively identify β-cells. Significantly lower FGFR1-associated immunofluorescence was observed in cells plated on laminin than on collagen type IV (Fig. 5A), consistent with the response observed in βTC3 (Fig. 3A). To verify this trend in islet β-cells, we measured FGFR1 expression from islets with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive β-cells [mouse insulin promoter-driven expression (MIP-GFP) (24)] by flow cytometry (Fig. 5B). Control WT islets were used to establish gating parameters for GFP- and FGFR-positive cells (Fig. 5B, top). In dispersed islets plated on collagen type IV, 74% of the GFP-positive cells were also FGFR1 positive (Fig. 5B, middle). In dispersed islets plated on laminin, fewer GFP (β-cell)-positive cells were FGFR1 positive (70%), and the FGFR1 mean fluorescence intensity was reduced (575 to 532 AU on Collagen type IV as compared with laminin). A similar trend was also observed in WT islets costained for insulin (data not shown). FGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation was significantly higher in cells plated on collagen type IV than laminin at all time points studied (Fig. 5C; -▪- vs. -○-). In contrast to the sustained response in cells plated on collagen type IV, the response on laminin returned to baseline by 30 min. These data indicate that β-cell FGFR1 activity is regulated by microenvironment, which subsequently affects downstream ERK1/2 signaling. A maximal, sustained ERK1/2 response is found in cells plated on collagen type IV whereas a smaller, transient response is observed in cells plated on laminin.

Figure 5.

Dispersed β-Cell FGFR1 Expression and ERK1/2 Phosphorylation Is Reduced by Attachment to Laminin

A, FGFR1-associated immunofluorescence (flg) in dispersed islet β-cells cultured overnight on collagen type IV or laminin. Data are plotted as fold change in intensity compared with cells plated on control poly-l-lysine ± sem from three mice on separate days. B, FGFR expression was detected by flow cytometry in insulin (GFP)-positive β-cells dispersed on Col IV and LM. WT islets labeled for FGFR1 using the N terminus-specific antibody complexed with Zenon PE-Alexa647 were used to set the quadrants (top). MIP-GFP islets were dispersed on collagen type IV (Col IV, middle) and laminin (LM, bottom). FGFR1-mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the GFP-positive cells is shown as well as the percent GFP-positive cells that were FGFR1 negative and positive. A representative plot is shown; n = 2. C, Changes in ERK1/2 phosphorylation in dispersed islet β-cells plated on collagen type IV and laminin. Cells were stimulated with FGF-1 (10 ng/ml, times as indicated), and phospho-ERK1/2-associated fluorescence intensity was measured in β-cells costaining positively for insulin. Data are plotted as fold change in phospho-ERK1/2 immunofluorescence intensity compared with nonstimulated control (time 0) ± sem from four mice on separate days. The dotted line shown at 1-fold change phospho-ERK1/2 intensity is shown to assist data interpretation. *, P < 0.05; #, P < 0.02 (Student’s two-tailed t test). PLL, Poly-l-lysine.

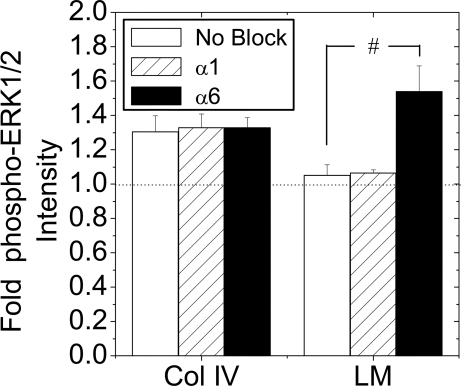

α6-Integin Engagement Mediates Transient ERK1/2 Responses on Laminin

To determine whether the ERK1/2 responses are enhanced or reduced by binding to collagen type IV or laminin, respectively, we examined phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in the presence of neutralizing integrin antibodies (Fig. 6). Antibodies were selected to inhibit the primary epithelial cell integrins that bind collagen type IV (α1β1 with α1-neutralizing antibody) or laminin (α6β1 with α6-neutralizing antibody). At 30 min FGF-1 stimulation, the phospho-ERK1/2 response of cells plated on collagen type IV was unaffected by either antibody. In cells plated on laminin in the absence of blocking antibody, a reduced phospho-ERK1/2 response was again observed. This response was unaffected by α1-integrin neutralizing antibody but significantly increased in the presence of the α6-neutralizing antibody. These data are consistent with a transient FGF-1-stimulated response due to engagement of α6-integrin receptors to laminin. Loss of this engagement results in a sustained phospho-ERK1/2 response.

Figure 6.

FGF-1 Induced ERK1/2 Activation in the Presence of Neutralizing Integrin Antibodies

Islets were dispersed to single β-cells and cultured overnight on collagen type IV (Col IV) or laminin (LM) in the presence or absence (No block) of integrin-neutralizing antibodies (α1 or α6; 10 μg/ml). Cells were serum starved in 0.2% fetal bovine serum for 6 h before treatment with 10 ng/ml FGF-1 for 30 min. Data are plotted as fold change in phospho-ERK1/2 immunofluorescence intensity compared with nonstimulated control ± sem from four mice on separate days. *, P < 0.05 (Student’s two-tailed t test).

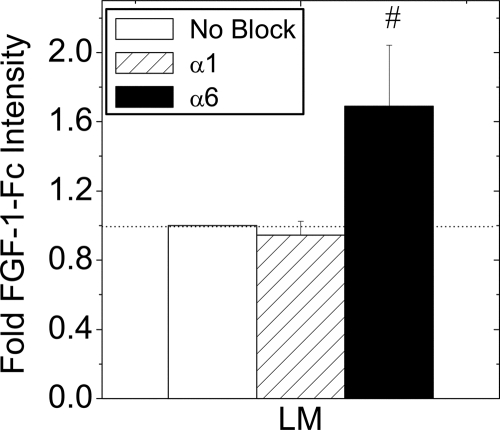

α6-Integrin Engagement Decreases High-Affinity FGF-1 Binding Sites

FGF-1-Fc fusion protein was used to measure the effect of laminin attachment on high-affinity receptors at the plasma membrane (Fig. 7). FGF-1-Fc binding to laminin-plated cells was unaffected by α1-neutralizing antibody, but was significantly increased in the presence of α6-neutralizing antibody. In contrast, FGF-1-Fc binding to cells plated on collagen type IV was unaffected by either antibody (data not shown). These data indicate that the number of FGFRs at the plasma membrane is reduced by engagement of α6-integrins to laminin.

Figure 7.

FGF-1-Fc Fusion Protein Receptor Binding in the Presence of Integrin-Neutralizing Antibodies

Islets were dispersed to single β-cells and cultured overnight on laminin (LM) in the presence or absence (No block) of integrin neutralizing antibodies (α1 or α6; 10 μg/ml). Cells were incubated with FGF-1-Fc (100 ng/ml, 1 h on ice) and fusion protein was removed from low-affinity binding sites by washing quickly with heparin (250 μg/ml). FGF-1-Fc and insulin were detected by immunofluorescence. Data are plotted as the mean FGF-1-Fc immunofluorescence intensity relative to no block control ± sem from four mice on separate days. The dotted line shown at 1-fold change phospho-ERK1/2 intensity is shown to assist data interpretation.*, P < 0.05 (Student’s two-tailed t test).

DISCUSSION

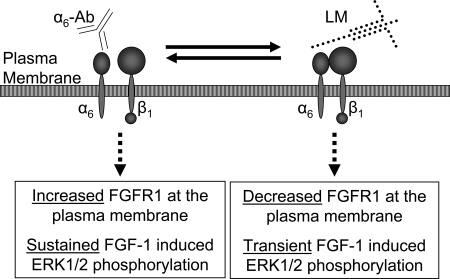

Recent studies demonstrate a role for FGFR1 signaling in β-cell survival and function as well as enhancement of insulin content (9,10,11). To gain insight into the molecular physiology of FGFR1 signaling specifically in insulin-secreting cells, we first confirmed expression of functional FGFR1 in islet β-cells that induces phosphorylation of ERK1/2. This response was specific to FGFR1 because it increased significantly with expression of full-length receptor-1 (R1βv) and was suppressed by expression of kinase-deficient receptor-1 (KDR1βv). Due to evidence for integrin cross-talk in other cell types, we subsequently investigated modulation of FGFR1 activity of cells plated on various ECMs. We observed significantly greater FGFR1 protein levels and a sustained phospho-ERK1/2 response in cells plated on collagen type IV as compared with laminin, the major components of in vivo islet basement membrane (Fig. 8) (15). By using integrin-neutralizing antibodies to inhibit binding to collagen type IV and laminin, we determined that the activity of FGFR1 was reduced in cells plated on laminin due to α6-integrin engagement. These data indicate that the FGFR1-stimulated response in β-cells is contextual, with the response influenced by environmental cues from the ECM.

Figure 8.

The Effect of β-Cell Attachment to Laminin through α6-Integrin

A schematic representing a β-cell plasma membrane with α6β1-integrin either neutralized with antibody (α6-Ab) or bound to laminin (LM). Our data demonstrate that inhibiting integrin attachment with neutralizing antibody results in an increase in high-affinity FGF-1 binding (Increased FGFR1) and sustained FGF-1-stimulated ERK1/2 response. In contrast, α6β1 binding to laminin decreases high-affinity receptor at the plasma membrane (Decreased FGFR1) and results in a transient FGF-1-stimulated ERK1/2 response.

Pancreatic islets are vascularized in vivo to the extent that each β-cell is associated with a vascular endothelial cell that is primarily responsible for deposition of ECM (13,25). Interaction of β-cells with ECM occurs through integrins including α6β1 and α1β1 (16,26). Integrin engagement affects β-cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and insulin secretion during ex vivo culture (18,26,27,28). The ability of vascular endothelial cell-deposited ECM to affect β-cell responses underscores a communication between these cells. Our data add further complexity to this communication by highlighting the modulation of FGF-signaling: ECM remodeling of laminin/α6-integrin engagement regulates FGFR receptor at the β-cell plasma membrane. It should be noted that the ECM also acts as a reservoir for FGF-ligand that can be released during matrix remodeling (2). One can therefore postulate a communication loop between β-cells and vascular endothelial cells that involves ECM and FGF-interactions. Studies are in progress to further examine the molecular mechanisms behind the regulation of β-cell FGFR1 by α6-integrin engagement.

Temporal regulation of ERK1/2 activity results in varied responses even within the same cell type. ERK1/2 activation in the neuronal PC12 cell line stimulates proliferation, differentiation, or apoptosis depending on whether the response is transient (10 min), sustained (several hours), or chronic during stress (24 h), respectively (29). Such variation results, in part, from localization of the signal, with ERK1/2 translocating from the cytosol to the nucleus during sustained activation due to homodimerization (30). Modeling of the PC12 cell temporal ERK1/2 response suggests that increasing activated receptor concentration leads to sustained activation (31). Our data are consistent with this model because we observed a shift from transient- to sustained-ERK1/2 activation that was associated with an increase in high-affinity receptor at the plasma membrane (cells plated on laminin in the presence of α6-neutralizing antibody). In β-cells, ERK1/2 activation elevates insulin gene transcription (32). Taking into consideration the similarities between neuronal- and β-cells, the ability to control the ERK1/2 response by modification of endothelial ECM suggests a strategy to modify the phenotype to a wider range, perhaps including proliferation and differentiation.

β-Cell mass increases through hyperplasia in response to elevated insulin need, as occurs during weight gain or pregnancy. This hyperplasia is likely associated with concerted vascular endothelial cell remodeling. Mature vascular endothelial cells maintain a laminin-rich matrix that is degraded as an early step in microvasculature budding, leaving collagen type IV as an intermediate scaffold (33). At the conclusion of angiogenesis, a laminin-rich matrix is again formed. Our data suggest that β-cell FGFR1 activity is modulated throughout this process with the initial reduction in laminin increasing receptor activity, and the conclusion of hyperplasia associated with an increase in laminin that decreases receptor activity. ECM modification also occurs during the progression of diabetes due to vascular injury and the formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) (21). AGEs modify collagen type IV to inhibit matrix formation and modify laminin to reduce collagen type IV binding. AGE modification is not limited to ECM because it has recently been shown to reduce FGF activity (34). Our data suggest that a loss of collagen type IV matrix due to AGEs would result in short-term FGF-induced ERK1/2 activation.

These data have broader implications for the treatment of type 1 and 2 diabetes. Loss of β-cell mass associated with type 1 and 2 diabetes eventually results in the inability to control blood glucose-homeostasis. Any means to either alleviate or restore β-cell mass clinically is a major target for numerous laboratories studying β-cell biology and development. One strategy is to delineate growth signals that induce ex vivo β-cell reproduction for use in transplantation. Our data suggest that a key regulatory signal is the extracellular environment. Our data also suggest that β-cell mass can be clinically regulated in vivo by affecting vascular endothelial ECM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell and Islet Culture

βTC3 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 15% fetal horse serum, 2.5% fetal bovine serum, 11 mm glucose, and 5 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin. Human embryonic kidney 293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 22 mm glucose, and 5 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin. Islets were isolated from pancreata of 6-to 12-wk-old male C57Bl/6 mice by collagenase digestion (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) (35,36), hand-picked twice, and cultured on human ECM (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA)-coated glass-bottomed dishes (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY). Freshly isolated islets were also routinely dispersed into single cells by treatment with 0.025% Trypsin-EDTA at 37 C before overnight culture on ECM-coated dishes. Islets and dispersed cells were maintained in complete RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 11 mm glucose, and 5 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin.

Full-Length and Kinase-Deficient FGFR1 Isoform Constructs

A full-length FGFR1βa1 (two IgG-loop isoform) sequence (present nomenclature: FGFR1IIIc) created by Dr. W. L. McKeehan (Texas A&M, College Station, TX) was obtained from Dr. G. Miller (Infectious Diseases, Vanderbilt University Medical Center). An NheI restriction site within the FGFR1βa1 sequence was removed while preserving the amino acid integrity using the paired primers 5′-CAGTGGGACTCCCAT(A)CTAGCAGGGGTCTCTG-3′ and 5′-CAGAGACCCCTGCTAG(T)ATGGGAGTCCCACTG-3′. The full-length receptor isoform with modified Kozak sequence was subsequently cloned in frame with monomeric Venus fluorescent protein into the NheI and AgeI sites of the N1 vector (37) using (R1-NheI) 5′-ATAA G/CTAGC CACCATGTGGAGCTGGAAGAGCCTCC-3′ and (R1-AgeI) 5′-AAATA/CCGGTCGGCGTTTGAGTCCGCCATTG-3′, resulting in the pR1βv vector. Similarly, a truncated receptor isoform lacking the kinase domain of the receptor was cloned in frame of monomeric Venus-N1 into the NheI and AgeI sites using the R1-NheI primer and (KDR1-AgeI) 5′-CGGAA/CCGGTGCCATCTGGCTGTGGAAGTC-3′, resulting in the kinase-deficient pKDR1βv vector.

Lentiviral Plasmids and Production

Lentiviral vectors (pCMVΔR8.2, pHR′-CMVEGFP, and pL-vsvg) were a generous gift from D. Unutmaz (Vanderbilt University Medical Center). pHR′-CMVEGFP was modified to use the Gateway cloning system (Gateway Cloning, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and to introduce the rat insulin promoter (RIP). The cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, ccdB, and attR1/attR2 splice sites from the Gateway Lenti6/V5-DEST vector were placed into ClaI and XhoI excision sites (pHR′-CMVgtw-ccb). The RIP was placed into the ClaI/SpeI sites of pHR′-CMVgtw-ccb (pHR′-RIPgtw-ccb) (38). The Gateway ENTR3C vector was also modified to remove an NheI site (5′-CCGTATTACCGCAAGCATGGATCTCG-3′, and 5′-CGAGATCCATGCAACGCCATTATGCC-3′) and replace a SalI site with an NheI site (5′-GGAACCAATTCAGCTAGCTGGATCCGGTACCG-3′, and 5′-CGGTACCGGATCCAGCTAGCTGAATTGGTTCC-3′) resulting in the pENTR3C-E/N/N vector. The NheI and NotI sites of pENTR3C-E/N/N were used to insert R1βv, KDR1βv, and N1-Venus. The resulting entry vectors were used for LR ligation (Gateway) into the HR′-RIPgtw-ccb plasmid resulting in the lentiviral packaging vectors pHR′RIP-R1βv, pHR′RIP-KDR1βv, and pHR′RIP-Venus. To reduce base pair distance between translation and start sites, the sequence between SpeI and NheI was removed.

Human embryonic kidney 293T cells (∼50% confluent) cultured overnight on poly-d-lysine-coated 100-mm culture dishes (BD Biosciences) were cotransfected with pL-vsvg (4 μg), pCMVΔR8.2 (7.5 μg), and pHR′RIP-R1βv, pHR′RIP-KDR1βv, or pHR′RIP-Ven (8 μg) using Fugene-6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science). Culture media were replaced 1 d after transfection and viral supernatant was collected at 48 and 72 h after transfection. Supernatant was filtered (0.45-μm polyvinylidenedifluoride filter) and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for storage at −80 C. Virus titers were 1–7 × 106 infectious units/ml as determined by measuring fluorescent protein expression in βTC3 cells.

βTC3 cells were infected with a multiplicity of infection of approximately 5 [20:1 (virus supernatant-100 μg/ml polybrene)] overnight. Infections resulted in 80–90% expression of R1βv, KDR1βv, and Venus and was stable for at least five passages. Cultured islets were infected overnight in eight-well glass-bottomed dishes (five to 10 islets per well) using 19:1 (viral supernatant-polybrene). Culture media were replaced the next day, and fluorescent protein expression was imaged 2–3 d after infection.

Western Immunoblotting

Dispersed islet or βTC3 cells were plated on matrices overnight for 18 h. Cells were harvested using Accutase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). For stimulation experiments, cells were serum starved in 0.2% fetal bovine serum/DMEM (11 mm glucose) overnight before incubation in the presence or absence of FGF-1 (10 ng/ml, times as indicated). Cell pellets were lysed in lysis buffer [1% Triton X-100, 100 mm sodium chloride, 50 mm HEPES, 5% glycerol, 1 mm sodium vanadate, and protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science)]. Whole-cell lysate protein concentration was determined by colorimetric protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) using BSA as a standard. Protein lysates (10 μg/lane) were separated by 7% or 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to Trans-Blot nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked by incubating with 5% nonfat dry milk powder/Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (1 h, RT). Proteins of interest were detected by overnight incubation at 4 C in either 5% BSA/TBS-T or 5% milk powder/TBS-T (as per manufacturer’s recommendations) for the following polyclonal antibodies: N-terminal FGFR1[Cell Signaling Technology (CST), Beverly, MA; 1:1000], Flg (C-15) FGFR-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA; 1:500), Living Colors A.V. Peptide (α-GFP, CLONTECH, 1:400), phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204) (CST, 1:1000), p44/42 MAPK (CST, 1:1000) or β-Actin (CST, 1:1000). Blots were subsequently incubated with either horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL; 1:5000) or antirabbit horseradish peroxidase-linked antibody (CST; 1:2000) diluted in 5% milk/TBS-T (45min RT), and proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence.

ECM Coating

Coverslip-bottom dishes [eight-well LabTech (Nalge Nunc International) or custom made 16 well] were coated with poly-l-lysine (1 h) (0.01%, Sigma-Aldrich) before incubation at 37 C for 3–4 h with ECM (Sigma-Aldrich): 1 mg/ml collagen type IV (catalog no. 5533), 128 μg/ml laminin (catalog no. L2020), 0.1% (wt/vol) collagen type I in 0.1% acetic acid (catalog no. C9791), 320 μg/ml fibronectin (catalog no. F459), or 50 μg/ml vitronectin (catalog no. V9881). Dishes were washed with Hanks’ balanced salt solution immediately before plating βTC3 or dispersed islet cells.

Live Cell Fluorescence Recovery after Photobleaching

The 63× 1.4 NA oil immersion lens of a Zeiss LSM510 inverted confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) was used for image collection (0.985 s/image, 488 nm excitation, long-pass 505-nm emission). After acquisition of five baseline images, a region of interest (20 × 20 pixel area) on individual cells was photobleached using 50 iterations of 100% laser power. Fluorescence recovery data were collected from subsequent images in the bleached region, the remainder of the cell, and a background region to calculate the normalized fluorescence recovery (ΔF/Fo). Recovery plots were fit using Origin 7.0 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA) to calculate the t1/2 of recovery.

Immunofluorescence Protein Detection

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde [10 min at room temperature (RT)] followed by 100% ice-cold methanol (−20 C; 10 min), and blocked for 1 h at RT with 5% normal goat serum (0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS). The samples were then incubated overnight at 4 C with the following antibodies diluted in block solution (PBS containing 1.5% normal goat serum and 0.1% Triton X-100): phospho-ERK1/2 [phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204); 1:200], flg (C-15) (10 μg/ml), normal rabbit IgG (10 μg/ml), guinea pig antiglucagon (1:1000, Linco Research, Inc., St. Charles, MO) and/or guinea pig antiinsulin (1:1000, Linco). Antibodies were detected using either antirabbit Alexa-Fluor 568 or antiguinea pig Alexa Fluor 488 diluted 1:1000 (Invitrogen) in block solution for 45 min at RT. Single-color FGFR1 immunofluorescence of βTC3 cells was detected using a 40× 1.3 NA immersion oil lens and a 610-nm long-pass filter cube (Chroma) on a Nikon TE300 inverted wide-field microscope (Nikon Melville, NY), and images were acquired using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). All other images were collected using the 40× 1.3 NA oil immersion lens of a Zeiss LSM510 inverted confocal. For doubly stained samples, sequential images were collected using the 488- and 543-nm laser lines with the 500- to 550-nm band pass and 560-nm long-pass filters, respectively. This detection scheme allowed spectral separation of Venus or Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescence from Alexa Fluor 568 fluorescence.

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry was done on βTC3 cells and dispersed islets [WT and MIP-GFP (24)] using an N-terminal-specific mouse monoclonal antibody for FGFR1 (M2F12; QED Biosciences, San Diego, CA). βTC3 cells were plated on coated 100-mm dishes. Dispersed islets from two WT and four MIP-GFP mice were plated in two and three wells, respectively of a 24-well plate. Coatings and pretreatments were similar to the immunofluorescence detection of FGFR1 except the cells were lifted from the ECM using Accutase (10 min, 37 C; Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were then placed on ice, blocked with 1% BSA, and labeled with M2F12-antibody complexed with antimouse IgG2a Zenon PE-Alexa647 or Alexa488 (0.5 μg/ml, 1 h). The cells were then washed twice and placed in PBS for flow cytometry on a FACS Aria (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Single-color data are presented as histograms (Alexa488); multicolor data are presented as quadrants based on cell scatter and FGFR1-associated fluorescence intensity (GFP and PE-Alexa647).

High-Affinity FGF-1 Receptors

A previously described recombinant FGF-1 fusion protein (FGF-1-Fc) was used to measure high-affinity FGF-1 binding sites at the plasma membrane of dispersed β-cells (39). Dispersed β-cells were cultured overnight on the indicated matrix in media containing α1, α6, or no neutralizing antibody (10 μg/ml, CD49a and CD49f; BD Pharmingen). Cells were washed with PBS and incubated on ice (1 h) with 100 ng/ml FGF-1-Fc and 2.5 μg/ml heparin. To remove FGF-1-Fc from low-affinity heparin-binding sites, cells were incubated for 30 sec with 250 μg/ml heparin, washed with PBS, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Nonspecific sites were blocked using 5% normal goat serum/PBS (1 h, RT). High-affinity receptor-bound FGF-1-Fc was detected using successive 1-h incubations with rabbit antihuman IgG (1:100) and goat antirabbit Alexa 568 (1:1000) in 1.5% normal goat serum. To discern insulin-positive β-cells, the samples were permeabilized (0.1% Triton-X 100), blocked (5% normal goat serum), and incubated successively with guinea pig antiinsulin (1:1000; 1 h) and goat antiguinea pig Alexa 488 (1:1000; 1 h).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mark Rizzo for modifying the lentiviral entrance and packaging vectors, Dr. Roy Zent for selection of the appropriate integrin-neutralizing antibodies, and Dr. Subhadra Gunawardana for providing us with MIP-GFP mice from her mouse colony.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) career development award (DK68206; to J.V.R.). Laboratory space was generously provided by Dr. David W. Piston and supported by NIH Grant DK53434. Confocal and wide-field imaging was performed in part through the use of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Cell Imaging Shared Resource (supported by NIH Grants CA68485, DK58404, HD15052, DK59637, EY08126, and DK20593).

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online October 4, 2007

Abbreviations: AGE, Advanced glycation end-product; CMV, cytomegalovirus; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; FGFR, FGF receptor; GFP, green fluorescent protein; MIP, mouse insulin promoter; RIP, rat insulin promoter; RT, room temperature; TBS-T, Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20; WT, wild type.

References

- Ornitz DM, Itoh N 2001 Fibroblast growth factors. Genome Biol 2:REVIEWS3005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gospodarowicz D, Cheng J 1986 Heparin protects basic and acidic FGF from inactivation. J Cell Physiol 128:475–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DE, Williams LT 1993 Structural and functional diversity in the FGF receptor multigene family. Adv Cancer Res 60:1–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cool SM, Sayer RE, van Heumen WR, Pickles JO, Nurcombe V 2002 Temporal and spatial expression of fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 isoforms in murine tissues. Histochem J 34:291–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arany E, Hill DJ 2000 Ontogeny of fibroblast growth factors in the early development of the rat endocrine pancreas. Pediatr Res 48:389–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichmann DS, Miller CP, Jensen J, Scott Heller R, Serup P 2003 Expression and misexpression of members of the FGF and TGFβ families of growth factors in the developing mouse pancreas. Dev Dyn 226:663–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miralles F, Czernichow P, Ozaki K, Itoh N, Scharfmann R 1999 Signaling through fibroblast growth factor receptor 2b plays a key role in the development of the exocrine pancreas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:6267–6272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichmann DS, Rescan C, Frandsen U, Serup P 2003 Unspecific labeling of pancreatic islets by antisera against fibroblast growth factors and their receptors. J Histochem Cytochem 51:397–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart AW, Baeza N, Apelqvist A, Edlund H 2000 Attenuation of FGF signalling in mouse β-cells leads to diabetes. Nature 408:864–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Iezzi M, Theander S, Antinozzi PA, Gauthier BR, Halban PA, Wollheim CB 2005 Suppression of Pdx-1 perturbs proinsulin processing, insulin secretion and GLP-1 signalling in INS-1 cells. Diabetologia 48:720–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wente W, Efanov AM, Brenner M, Kharitonenkov A, Köster A, Sandusky GE, Sewing S, Treinies I, Zitzer H, Gromada J 2006 Fibroblast growth factor-21 improves pancreatic β-cell function and survival by activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and Akt signaling pathways. Diabetes 55:2470–2478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliceiri BP 2001 Integrin and growth factor receptor crosstalk. Circ Res 89:1104–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolova G, Jabs N, Konstantinova I, Domogatskaya A, Tryggvason K, Sorokin L, Fässler R, Gu G, Gerber HP, Ferrara N, Melton DA, Lammert E 2006 The vascular basement membrane: a niche for insulin gene expression and β cell proliferation. Dev Cell 10:397–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RN, Rosenberg L 1999 Maintenance of β-cell function and survival following islet isolation requires re-establishment of the islet-matrix relationship. J Endocrinol 163:181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Deijnen JH, Hulstaert CE, Wolters GH, van Schilfgaarde R 1992 Significance of the peri-insular extracellular matrix for islet isolation from the pancreas of rat, dog, pig, and man. Cell Tissue Res 267:139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaido T, Perez B, Yebra M, Hill J, Cirulli V, Hayek A, Montgomery AM 2004 αv-Integrin utilization in human β-cell adhesion, spreading, and motility. J Biol Chem 279:17731–17737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirulli V, Beattie GM, Klier G, Ellisman M, Ricordi C, Quaranta V, Frasier F, Ishii JK, Hayek A, Salomon DR 2000 Expression and function of α(v) β(3) and α(v) β(5) integrins in the developing pancreas: roles in the adhesion and migration of putative endocrine progenitor cells. J Cell Biol 150:1445–1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnaud G, Hammar E, Rouiller DG, Armanet M, Halban PA, Bosco D 2006 Blockade of β1 integrin-laminin-5 interaction affects spreading and insulin secretion of rat β-cells attached on extracellular matrix. Diabetes 55:1413–1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkse GG, Bouwman WP, Jiawan-Lalai R, Terpstra OT, Bruijn JA, de Heer E 2006 Integrin signaling via RGD peptides and anti-β1 antibodies confers resistance to apoptosis in islets of Langerhans. Diabetes 55:312–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RN, Paraskevas S, Rosenberg L 1999 Characterization of integrin expression in islets isolated from hamster, canine, porcine, and human pancreas. J Histochem Cytochem 47:499–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin A, Beckman JA, Schmidt AM, Creager MA 2006 Advanced glycation end products: sparking the development of diabetic vascular injury. Circulation 114:597–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouhara H, Hadari YR, Spivak-Kroizman T, Schilling J, Bar-Sagi D, Lax I, Schlessinger J 1997 A lipid-anchored Grb2-binding protein that links FGF-receptor activation to the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway. Cell 89:693–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi M, Olsen SK, Ibrahimi OA 2005 Structural basis for fibroblast growth factor receptor activation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 16:107–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara M, Wang X, Kawamura T, Bindokas VP, Dizon RF, Alcoser SY, Magnuson MA, Bell GI 2003 Transgenic mice with green fluorescent protein-labeled pancreatic β-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284:E177–E183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera O, Berman DM, Kenyon NS, Ricordi C, Berggren PO, Caicedo A 2006 The unique cytoarchitecture of human pancreatic islets has implications for islet cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:2334–2339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco D, Meda P, Halban PA, Rouiller DG 2000 Importance of cell-matrix interactions in rat islet β-cell secretion in vitro: role of α6β1 integrin. Diabetes 49:233–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner-Weir S, Taneja M, Weir GC, Tatarkiewicz K, Song KH, Sharma A, O’Neil JJ 2000 In vitro cultivation of human islets from expanded ductal tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:7999–8004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaido T, Yebra M, Cirulli V, Rhodes C, Diaferia G, Montgomery AM 2006 Impact of defined matrix interactions on insulin production by cultured human β-cells: effect on insulin content, secretion, and gene transcription. Diabetes 55:2723–2729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung EC, Slack RS 2004 Emerging role for ERK as a key regulator of neuronal apoptosis. Sci STKE 2004:PE45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlatchev AV, Canagarajah B, Wilsbacher J, Robinson M, Atkinson M, Goldsmith E, Cobb MH 1998 Phosphorylation of the MAP kinase ERK2 promotes its homodimerization and nuclear translocation. Cell 93:605–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasagawa S, Ozaki Y, Fujita K, Kuroda S 2005 Prediction and validation of the distinct dynamics of transient and sustained ERK activation. Nat Cell Biol 7:365–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo S, Gibson TB, Arnette D, Lawrence M, January B, McGlynn K, Vanderbilt CA, Griffen SC, German MS, Cobb MH 2004 MAP kinases and their roles in pancreatic β-cells. Cell Biochem Biophys 40:191–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Senger DR 2005 Endothelial extracellular matrix: biosynthesis, remodeling, and functions during vascular morphogenesis and neovessel stabilization. Circ Res 97:1093–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facchiano F, D’Arcangelo D, Russo K, Fogliano V, Mennella C, Ragone R, Zambruno G, Carbone V, Ribatti D, Peschle C, Capogrossi MC, Facchiano A 2006 Glycated fibroblast growth factor-2 is quickly produced in vitro upon low-millimolar glucose treatment and detected in vivo in diabetic mice. Mol Endocrinol 20:2806–2818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan Y, Meda P, Neufeld M, Orci L 1987 Stimulation of insulin secretion reveals heterogeneity of pancreatic B cells in vivo. J Clin Invest 80:175–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharp DW, Kemp CB, Knight MJ, Ballinger WF, Lacy PE 1973 The use of ficoll in the preparation of viable islets of Langerhans from the rat pancreas. Transplantation 16:686–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T, Ibata K, Park ES, Kubota M, Mikoshiba K, Miyawaki A 2002 A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat Biotechnol 20:87–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D 1985 Heritable formation of pancreatic β-cell tumours in transgenic mice expressing recombinant insulin/simian virus 40 oncogenes. Nature 315:115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikov MM, Reich MB, Dworkin L, Thomas JW, Miller GG 1998 A functional fibroblast growth factor-1 immunoglobulin fusion protein. J Biol Chem 273:15811–15817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.