Abstract

Bcl-2 inhibits apoptosis induced by a variety of stimuli, including chemotherapy drugs and glucocorticoids. It is generally accepted that Bcl-2 exerts its antiapoptotic effects mainly by dimerizing with proapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family such as Bax and Bad. However, the mechanism of the antiapoptotic effects is unclear. Paclitaxel and other drugs that disturb microtubule dynamics kill cells in a Fas/Fas ligand (FasL)-dependent manner; antibody to FasL inhibits paclitaxel-induced apoptosis. We have found that Bcl-2 overexpression leads to the prevention of chemotherapy (paclitaxel)-induced expression of FasL and blocks paclitaxel-induced apoptosis. The mechanism of this effect is that Bcl-2 prevents the nuclear translocation of NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T lymphocytes, a transcription factor activated by microtubule damage) by binding and sequestering calcineurin, a calcium-dependent phosphatase that must dephosphorylate NFAT to move to the nucleus. Without NFAT nuclear translocation, the FasL gene is not transcribed. Thus, it appears that paclitaxel and other drugs that disturb microtubule function kill cells at least in part through the induction of FasL. Furthermore, Bcl-2 antagonizes drug-induced apoptosis by inhibiting calcineurin activation, blocking NFAT nuclear translocation, and preventing FasL expression. The effects of Bcl-2 can be overcome, at least partially, through phosphorylation of Bcl-2. Phosphorylated Bcl-2 cannot bind calcineurin, and NFAT activation, FasL expression, and apoptosis can occur after Bcl-2 phosphorylation.

Keywords: Fas ligand, apoptosis, NFAT, Bcl-2, paclitaxel

Binding of Fas ligand (FasL)1 or an anti-Fas antibody to Fas (APO-1 or CD-95) causes apoptosis in Fas-bearing cells. Fas is ubiquitously expressed in various cell types 1 2 3, but the expression of FasL is much more restricted 4 5 6 7. Although the expression of FasL was originally considered to be restricted to activated T cells and NK cells, FasL has been identified in other cell types, including Sertoli cells and cells of the eye, liver, and kidney 8. The expression of functional FasL by some tissues contributes to their immune-privileged status by preventing the infiltration of inflammatory leukocytes 9 10. Recently, constitutive FasL expression has been detected on some tumor cells, indicating that it may function to induce apoptosis in Fas-expressing immune cells when they attempt to enter the tumor 11 12 13 14. Moreover, it has been postulated that the Fas/FasL system has an important role in the pathogenesis of many diseases such as hepatitis, insulin-dependent diabetes, cancer, and thyroiditis (Hashimoto's disease) 15 16 17 18 19 20 21.

The antiapoptotic gene Bcl-2 protects cancer cells from apoptosis induced by a variety of anticancer agents 22 23 24 25. The precise mechanism by which Bcl-2 inhibits drug-induced apoptosis is unknown. Mice in which wild-type Bcl-2 was overexpressed documented extended cell survival rather than increased proliferation and led to an accumulation of lymphocytes that eventually progressed to B and T cell malignancy after subsequent genetic changes 26 27 28. Loss of function studies that knocked out the Bcl-2 or Bcl-XL death suppressors demonstrated the loss of cells from selected lineages 29 30 31. Although hematopoietic lineages appear to develop normally in the Bcl-2–deficient mice, they are unable to maintain homeostasis of lymphocytes because of excess apoptotic loss of B and T cells. Microtubule-stabilizing agents such as paclitaxel and docetaxel and microtubule-disrupting drugs such as vincristine, vinblastine, and colchicine have antimitotic and apoptosis-inducing activity 24 25 32 33. Recently, screening of a library of phage-displayed peptides identified human Bcl-2 as a paclitaxel-binding protein 34. Paclitaxel induces Bcl-2 phosphorylation and apoptosis in human leukemic, breast, and prostate cancer cells 24 25 35, suggesting that phosphorylation of Bcl-2 may inhibit Bcl-2 function. The regulation of Bcl-2 function by phosphorylation has been demonstrated at the level of formation of Bcl-2–Bax heterodimers. However, it is also possible that Bcl-2 exerts its biological effects in additional protein interactions distinct from those with proapoptotic family members.

A growing body of evidence suggests that the nuclear factor of activated T lymphocytes (NFAT) is expressed in a variety of tissues in addition to lymphocytes 36. To date, NFAT expression or function has been described in several types of nonlymphoid cells, including mast cells 37, endothelial cells 38, vascular smooth muscle cells 39, and neuronal cells 40. The messenger RNAs of distinct NFAT isoforms are expressed in a tissue-specific manner 41. Linette et al. 41a have documented a regulatory interaction between Bcl-2 expression and NFAT activation. Thus, it is possible that NFAT regulates the transcription of genes involved in apoptosis and that antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members act in part by interfering with NFAT-induced gene transcription.

One candidate proapoptotic gene that is regulated by NFAT is FasL. Transcription of the FasL gene is regulated at least in part by an interaction of NFAT proteins with the FasL promoter 42 43 44. Transcription mediated by NFAT is regulated tightly in response to second messengers such as calcium. Increased intracellular Ca2+ stimulates calcineurin-dependent dephosphorylation of cytoplasmic NFAT, leading to its nuclear translocation 45. T cell activation was found to induce NFAT binding to the FasL enhancer 45. Thus, it is possible that Bcl-2 mediates its antiapoptotic effects not only by forming heterodimers with proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members but also through antagonism of NFAT activation.

In this study, we examine the intracellular mechanisms by which Bcl-2 inhibits apoptosis induced by microtubule-damaging drugs (paclitaxel, vincristine, and vinblastine) in Jurkat T lymphocytes and breast carcinoma cells. We demonstrate that expression of FasL plays a significant role in apoptosis induced by microtubule-damaging drugs. Upon exposure to such drugs, FasL is rapidly expressed. Antibody to FasL inhibits paclitaxel-induced apoptosis. In cells overexpressing Bcl-2, FasL expression is blocked upon exposure to low doses of paclitaxel. The mechanism by which Bcl-2 inhibits FasL expression is indirect; Bcl-2 binds to calcineurin and inhibits its dephosphorylation and release of NFAT. Thus, NFAT is unable to translocate to the nucleus and FasL transcription does not occur. These results suggest a mechanism by which Bcl-2 acts to block drug- or activation-induced apoptosis. Very high doses of paclitaxel can overcome the inhibitory effects of Bcl-2 on NFAT nuclear translocation. High doses of paclitaxel lead to Bcl-2 phosphorylation and dissociation from calcineurin, which allows NFAT activation and FasL expression.

Materials and Methods

Reagents.

Paclitaxel, vincristine, vinblastine, ascomycin, and 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. Secondary antibody (donkey anti–goat IgG) conjugated with Alexa-488 and 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid tetra(acetoxymethyl)ester (BAPTA-AM) were purchased from Molecular Probes, Inc. and Calbiochem Corp., respectively. Antibodies against Bcl-2, β-actin, Fas, and FasL were purchased from Transduction Labs. FasL-neutralizing antibody was purchased from PharMingen. Fas-blocking antibody was purchased from Alexis. Antibody against NFAT was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Enhanced chemiluminescent Western blot detection reagents were purchased from Amersham Life Sciences, Inc. The chemiluminescent reporter gene assay system for the combined detection of luciferase and β-galactosidase was purchased from Tropix, Inc.

Cells and Culture Conditions.

Jurkat T cells and breast carcinoma MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 tissue culture medium (BioWhittaker, Inc.) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin–streptomycin mixture at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Transfection of Bcl-2 Genes.

Jurkat cells and MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with wild-type Bcl-2 as described elsewhere 25. The pSFFVneo-Bcl-2, pSFFVneo-Bcl-XL, and pSFFV Neo plasmids were provided by Dr. Stanley Korsmeyer (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA). Jurkat cells (JT/mut CD95) harboring a Fas mutant lacking the cytoplasmic domain were provided by Dr. Gary A. Koretzky (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA) and described elsewhere 46. MDA-MB-231 cells were also transfected with either pSFFVneo-ΔBH4 Bcl-2 or pSFFVneo-Δloop Bcl-2 plasmid using lipofectine (GIBCO BRL). Transduced cells were selected in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1 mg/ml G418 (Geneticin; GIBCO BRL) for 1 mo. Clones expressing the highest levels of Bcl-2 were used (data not shown).

For transient transfection, lipofectine reagent was used to transfect the plasmid as per manufacturer's instructions (GIBCO BRL). After transfection, the cells were incubated with complete medium for one additional day. These cells were then used for experiments.

Subcellular Fractionation.

Nuclear and cytosolic fractions were prepared by resuspending cells in 0.8 ml ice cold buffer A (250 mM sucrose, 20 mM Hepes, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 17 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 8 μg/ml aprotinin, and 2 μg/ml leupeptin, pH 7.4). Cells were passed through an ice cold cylindrical cell homogenizer. Cell suspensions were pelleted at 750 g for 20 min. Cytoplasmic extract was separated from the pellet. This pellet was resuspended in buffer A, homogenized, and spun at 10,000 g for 25 min. The clear supernatant was considered nuclear extract.

Lysate Preparation.

For Western blot analysis, cells were lysed in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.6; 150 mM NaCl; 0.5 mM EDTA; 1 mM EGTA; 1% SDS; 1 mM sodium orthovanadate; and a mixture of protease inhibitors (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 2 μg/ml aprotinin). The lysates were then sonicated for 10 s and centrifuged for 20 min at 1,200 g. The supernatants were used to perform SDS-PAGE or stored at −70°C.

Apoptosis.

For detection of apoptotic cells, the cells were first washed twice with ice cold PBS and then fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. The fixed cells were washed again with PBS and stained with 1 μg/ml DAPI solution for 30 min. The apoptotic cells were examined under a fluorescence microscope. Fluorescent nuclei were screened for normal morphology (unaltered chromatin), and apoptotic nuclei comprising those with fragmented (scattered) and condensed chromatin were counted. Data are expressed as the percentage of apoptotic cells in total counted cells.

Confocal Microscopy.

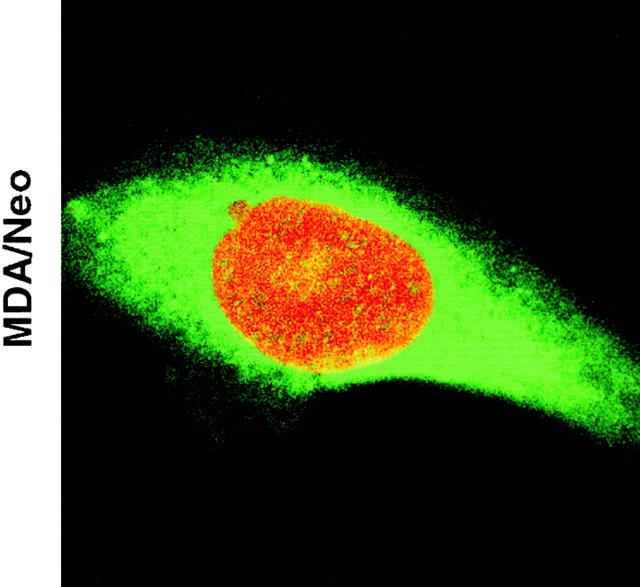

For the determination of NFAT translocation by confocal microscope imaging (Axiovert 100; Carl Zeiss, Inc.), cells from each group were seeded onto glass slides and treated with paclitaxel for 48 h. At the end of the incubation period, cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and 0.01% Triton X-100. Cells were incubated with propidium iodide (PI; 2 μg/ml) containing RNAse for 1 h and subsequently with anti-NFAT antibody (goat anti–human IgG; 2 μg/ml) for 1 h. After incubation, cells were washed three times and restained with secondary antibody (donkey anti–goat IgG) conjugated with Alexa-488 for 1 h. After mounting, cells were visualized for NFAT translocation (Alexa; emission 488 nm and excitation 520 nm) and nuclear fragmentation (PI; emission 540 nm and excitation 610 nm). The green and red colors represent cytoplasmic NFAT and nuclear staining, respectively. The yellow color represents NFAT translocated to the nucleus (red plus green) (see Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Confocal microscopy showing blockage of NFAT translocation by Bcl-2. MDA/Neo and MDA/Bcl-2 cells were treated with paclitaxel (50 nM) for 48 h. Cells were fixed and stained with anti-NFAT antibody along with PI. Cells were washed and restained with secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa-488. Green and red represent cytoplasmic NFAT and nuclear staining, respectively. Yellow, NFAT translocated to the nucleus.

Results

FasL Is Involved in Paclitaxel-induced Apoptosis.

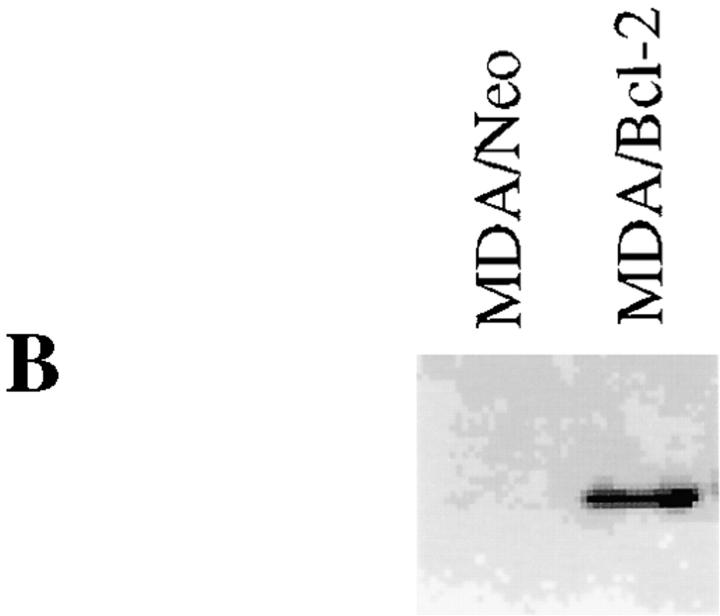

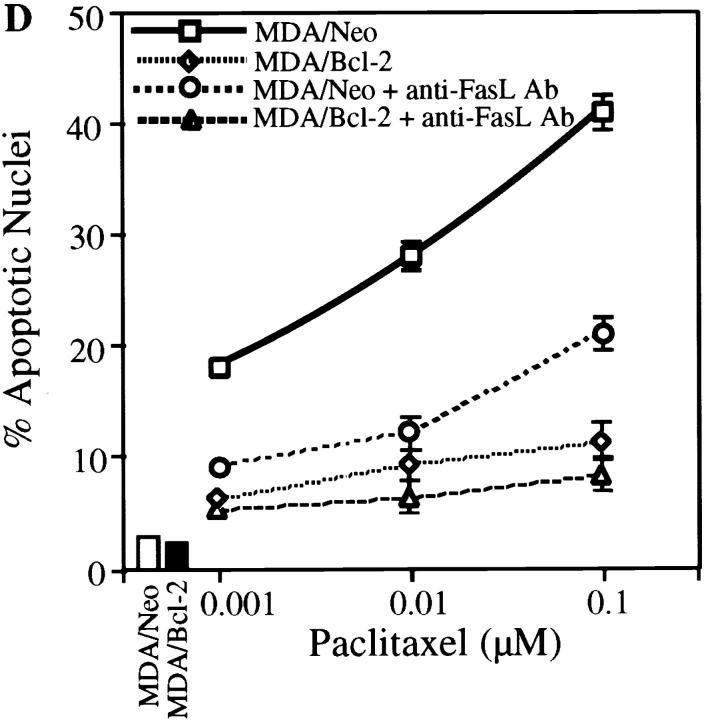

FasL induction has been demonstrated in activation-induced cell death in T cells 47 48 49 50 51 and in the death of other cell types induced by anticancer drugs 52, gamma irradiation 53, and UV light 54. We investigated the possibility of the involvement of the FasL/Fas pathway in paclitaxel-induced apoptosis. Jurkat cells or MDA-MB-231 cells were stably transfected with either pSSFV-Neo or pSSFV-Bcl-2 expression vector to assess the protective effects of Bcl-2 on paclitaxel-induced apoptosis (Fig. 1a and Fig. b). Treatment of cells with paclitaxel resulted in induction of apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner, and overexpression of Bcl-2 inhibited paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in Jurkat cells (Fig. 1 C). The paclitaxel dose–response curve suggests a 10-fold increase in resistance in cells overexpressing Bcl-2. Neutralization of FasL by treatment of cells with anti-FasL antibody (NOK-2) significantly inhibited paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in both JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells. Indeed, very little tumor cell death could be documented in Bcl-2–overexpressing Jurkat cells exposed to anti-FasL antibody. To examine the role of Bcl-2 in paclitaxel-induced apoptosis, we used MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, which do not express endogenous Bcl-2 (Fig. 1 B). Overexpression of Bcl-2 in MDA cells inhibited paclitaxel-induced apoptosis by greater than two logs (Fig. 1 D). Neutralization of FasL by anti-FasL antibody (NOK-2) significantly inhibited paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in MDA/Neo but had little effect in MDA/Bcl-2 cells. Incubation of cells with Fas- blocking antibody inhibited paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells. Similarly, overexpression of mutant CD95/Fas (mutant receptors lacking intracellular cytoplasmic domains) inhibited paclitaxel-induced apoptosis (Fig. 1 F). Taken together, these data demonstrate that (a) paclitaxel-induced apoptosis can be inhibited by Bcl-2 and (b) the FasL/Fas pathway, at least in part, mediates paclitaxel-induced apoptosis.

Figure 1.

Bcl-2 inhibits paclitaxel-induced apoptosis. (A) Jurkat cells were stably transfected with either pSSFV-neo or pSFFV-Bcl-2 plasmid. (B) MDA-MB-231 cells were stably transfected with either pSSFV-neo or pSFFV-Bcl-2 plasmid. (C) Jurkat cells (JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2) were treated with paclitaxel (0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 μM) with or without anti-FasL neutralizing antibody (NOK-2; 1 μg/ml) for 48 h. Cells were stained with DAPI and visualized under fluorescence microscopy. Cells with fragmented nuclei or condensed chromatin were counted as apoptotic. Data (mean ± SE of quadruplicate determinations) represent one of three separate experiments that gave similar results. (D) MDA/MB/231 (MDA/Neo and MDA/Bcl-2) were treated with paclitaxel (0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 μM) with or without anti-FasL neutralizing antibody (NOK-2; 1 μg/ml) for 48 h. Cells were stained with DAPI and visualized under fluorescence microscopy. Cells with fragmented and condensed chromatin were counted as apoptotic. Data (mean ± SE of quadruplicate determinations) represent one of three separate experiments that gave similar results. (E) JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells were treated with paclitaxel (0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 μM) with or without anti-Fas blocking antibody (1 μg/ml) for 48 h. Apoptotic nuclei were counted as described for D. (F) JT/Neo and JT/mut CD95 cells were treated with paclitaxel (0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 μM) for 48 h. Apoptotic nuclei were counted as described for D.

Bcl-2 Blocks FasL Expression.

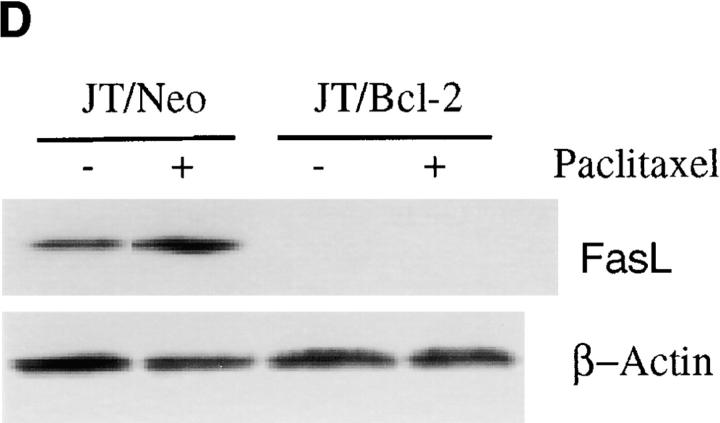

The induction of FasL during activation- or drug-induced cell death has been reported 47 48 49 50 51 52. As neutralization of FasL by anti-FasL antibody inhibited paclitaxel-induced apoptosis, we sought to evaluate the expression of FasL in wild-type and Bcl-2– overexpressing cells. Treatment of wild-type MDA cells with paclitaxel, vincristine, or vinblastine induced FasL expression in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2 A). Treatment of breast cancer cells (MDA and MCF-7) with paclitaxel resulted in induction of FasL in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2 B). We have previously demonstrated that Bcl-2 inhibits apoptosis induced by microtubule-damaging drugs (paclitaxel, vincristine, and vinblastine) 25; therefore, it was of interest to examine whether Bcl-2 would also inhibit FasL expression. Treatment of MDA/Neo cells with 50 nM of paclitaxel or vincristine resulted in induction of FasL; by contrast, the induction of FasL was blocked by overexpression of Bcl-2 in MDA/Bcl-2 cells (Fig. 2 C). JT/Neo cells expressed some FasL at baseline, and paclitaxel induced an increase in FasL expression. The expression of Bcl-2 in JT/Bcl-2 transfectants blocked both the baseline expression and the induction of FasL by paclitaxel (Fig. 2 D). Thus, Bcl-2 expression interferes with FasL expression.

Figure 2.

Bcl-2 inhibits paclitaxel-, vincristine-, and vinblastine-induced FasL expression. (A) MDA cells were treated with 50 nM of paclitaxel, vincristine, or vinblastine for either 24 or 48 h. At the end of incubation period, cells were harvested and lysed. Equal amounts of protein were resolved on SDS-PAGE. FasL levels were measured by Western blot analysis. The same blot was reprobed with anti–β-actin antibody to check if equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane. (B) MDA and MCF-7 cells were treated with various concentrations of paclitaxel for 48 h. FasL levels were detected by Western blot analysis. The blot was reprobed with anti–β-actin antibody to check if equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane. (C) MDA/Neo and MDA/Bcl-2 cells were treated with 50 nM of paclitaxel or vincristine for 48 h. FasL levels were detected by Western blot analysis. The blot was reprobed with anti–β-actin antibody to check if equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane. (D) JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells were treated with paclitaxel (50 nM) for 48 h. FasL levels were detected by Western blot analysis. The blot was reprobed with anti–β-actin antibody to check if equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane.

Bcl-2 Blocks NFAT Translocation to the Nucleus.

The activation of calcineurin, a serine phosphatase, is regulated by calcium. Activated calcineurin functions to dephosphorylate NFAT family members 45. Dephosphorylated NFAT proteins then translocate to and enter the nucleus, where they serve an essential role in regulating the expression of many cytokine genes 55 56. As Bcl-2 blocks paclitaxel-induced FasL expression and apoptosis, we examined the effects of Bcl-2 on NFAT translocation to the nucleus. NFAT was localized to the cytoplasm in untreated (control) JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 (Fig. 3 A). When JT/Neo cells were treated with paclitaxel, NFAT translocated to the nucleus (Fig. 3 A). In contrast, overexpression of Bcl-2 blocked paclitaxel-induced NFAT translocation to the nucleus (Fig. 3 A). Similarly, overexpression of Bcl-2 blocked paclitaxel-induced NFAT translocation to the nucleus in MDA/Bcl-2 cells (Fig. 3 B).

Figure 3.

Bcl-2 blocks NFAT translocation to the nucleus. (A) JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells were either treated with paclitaxel (50 nM) or vehicle (control) for 48 h. Cells were harvested, and cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-NFAT antibody. The same blot was reprobed with anti–β-actin antibody. (B) MDA/Neo and MDA/Bcl-2 cells were either treated with paclitaxel (50 nM) or vehicle for 48 h. Cells were harvested and C and N fractions were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-NFAT antibody. The same blot was reprobed with anti–β-actin antibody.

We confirmed paclitaxel-induced NFAT translocation by confocal microscopy (Fig. 4). We next examined if Bcl-2 would block NFAT translocation to the nucleus in MDA cells by immunocytochemistry. As seen in Fig. 4 B, NFAT was localized to the cytoplasm in MDA/Neo and MDA/Bcl-2 cells (Fig. 4, green). Treatment of MDA/Neo cells with paclitaxel resulted in NFAT translocation to the nucleus (Fig. 4, red plus green = yellow color) and apoptosis (fragmented nucleus stained with red color). As expected, overexpression of Bcl-2 blocked paclitaxel-induced NFAT translocation to the nucleus and apoptosis in MDA cells (Fig. 4).

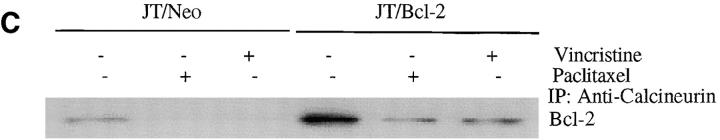

Bcl-2 Binds to Calcineurin but not NFAT.

The Bcl-2 inhibition of NFAT translocation to the nucleus is not direct but rather involves calcineurin 57. It has been shown that Bcl-2 binds to calcineurin and thereby inhibits translocation of NFAT to the nucleus 57. As the FasL promoter contains NFAT binding sites and NFAT participates in the regulation of FasL expression in activated human T cells 42, it was of interest to examine the intracellular mechanism(s) by which Bcl-2 inhibited paclitaxel-induced FasL expression. We have previously demonstrated that microtubule-damaging drugs initiated a signaling cascade that phosphorylated Bcl-2 in a time- and dose-dependent manner 25. The JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells were treated with 50 nM of either paclitaxel or vincristine for 24 h, lysed, immunoprecipitated with anti-NFAT antibody, and blotted with anti–Bcl-2 antibody (Fig. 5 A). These results indicated that NFAT did not bind to Bcl-2 in either JT/Neo or JT/Bcl-2 cells. When the NFAT immunoprecipitate was followed by NFAT Western blot, similar amounts of NFAT were immunoprecipitated (Fig. 5 A). Therefore, the apparent lack of association of NFAT and Bcl-2 is not related to inefficient NFAT immunoprecipitation. We next examined the interaction between Bcl-2 and calcineurin in paclitaxel- or vincristine-treated JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells. Cells were exposed to paclitaxel or vincristine for 48 h and then lysed. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibody to either Bcl-2 (Fig. 5 B) or calcineurin (Fig. 5 C), and Western blots were performed with the antibody not used in the immunoprecipitation. As shown in Fig. 5 B and C, Bcl-2 was able to bind calcineurin in untreated JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells. When JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells were treated with paclitaxel (50 nM) or vincristine (50 nM), less calcineurin was bound to Bcl-2 (Fig. 5b and Fig. c). These results suggest that Bcl-2 binds to calcineurin but not to NFAT, and the fraction of Bcl-2 and calcineurin bound to each other decreases upon exposure to the drugs. These results suggest that the phosphorylation of Bcl-2 stimulated by the drugs may also influence Bcl-2 binding to calcineurin just as it affects Bcl-2–Bax interaction 25.

Figure 5.

Bcl-2 binds to calcineurin but not NFAT. (A) JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells were treated with 50 nM of paclitaxel or vincristine for 48 h. The cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with 10 μg of anti-NFAT antibody and 20 μl of protein A–Sepharose. The samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with either anti–Bcl-2 antibody (top panel) or anti–NF-AT antibody (bottom panel). (B) JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells were treated with 50 nM of paclitaxel or vincristine for 48 h. The cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with 10 μg of anti–Bcl-2 antibody and 20 μl of protein A–Sepharose. The samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anticalcineurin. (C) JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells were treated with 50 nM of paclitaxel or vincristine for 48 h. The cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with 10 μg of anticalcineurin antibody and 20 μl of protein A–Sepharose. The samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–Bcl-2 antibody. (D) Left, JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells were treated with various concentrations of paclitaxel (0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 μM) with or without FK506 analogue ascomycin (10 μM) for 48 h to measure apoptosis. Cells were stained with DAPI and visualized under fluorescence microscopy. Cells with fragmented nuclei or condensed chromatin were counted as apoptotic. Data (mean ± SE of quadruplicate determinations) represent one of three separate experiments that gave similar results. Right, MDA/Neo and MDA/Bcl-2 cells were treated with various concentrations of paclitaxel (0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 μM) with or without FK506 analogue ascomycin (10 μM) for 48 h to measure apoptosis. Cells were stained with DAPI and visualized under fluorescence microscopy. Data (mean ± SE of quadruplicate determinations) represent one of three separate experiments that gave similar results. (E) JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells were pretreated with [(Ca2+)i] chelator BAPTA-AM (10 μM) for 45 min and then treated with paclitaxel (50 nM) for 48 h to measure apoptosis. Data (mean ± SE of quadruplicate determinations) represent one of three separate experiments that gave similar results.

The immunosuppressants cyclosporin and FK506 inhibit NFAT-dependent transcriptional events by binding calcineurin and blocking its enzymatic activity, thus preventing the redistribution of NFAT to the nucleus 36. To evaluate the involvement of active calcineurin in paclitaxel-induced apoptosis, cells were treated with the FK506 analogue ascomycin (Fig. 5 D). Paclitaxel induced apoptosis in both JT/Neo and MDA/Neo cells (Fig. 5 D). If Bcl-2 was acting to prevent calcineurin activation, its effects should have been mimicked by the pharmacological calcineurin inhibition of ascomycin. Overexpression of Bcl-2 inhibited paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in these cell lines. As expected, treatment of cells with ascomycin inhibited paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in neo- and Bcl-2–transfected cells (Fig. 5 D). Ascomycin appears to inhibit apoptosis additively in Bcl-2–expressing cells. It is possible that ascomycin has additional effects unrelated to Bcl-2 binding of calcineurin. These data confirm that inhibition of calcineurin activation blocks paclitaxel-induced apoptosis.

Because a rise in intracellular free calcium levels [(Ca2+)i] is essential for calcineurin activation 56, we sought to examine the effects of chelating intracellular free calcium by BAPTA-AM on paclitaxel-induced apoptosis (Fig. 5 E). JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells were pretreated with 10 μM BAPTA-AM for 45 min and then treated with paclitaxel (50 nM) for 48 h. Overexpression of Bcl-2 significantly inhibited paclitaxel-induced apoptosis. Interestingly, chelation of in-tracellular free calcium by BAPTA-AM inhibited paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2 cells (Fig. 5 E). That paclitaxel induces a rise in [(Ca2+)i] has been described by others 58 and confirmed by us (data not shown). These data suggest that a rise in [(Ca2+)i] is required for paclitaxel-induced apoptosis. These results provide additional evidence that paclitaxel-induced apoptosis involves a rise in [(Ca2+)i], leading to calcineurin activation, which in turn leads to NFAT translocation and expression of FasL.

BH4 Domain of Bcl-2 Is Required for Interaction with Calcineurin and Paclitaxel-induced FasL Expression and Apoptosis.

Thus, Bcl-2 blocked NFAT translocation by binding to calcineurin but not directly to NFAT. The BH4 domain of Bcl-2 has been demonstrated to mediate heterodimerization with calcineurin. We wished to use this finding to verify that the antiapoptotic effects of Bcl-2 were related to calcineurin binding. To answer this question, MDA cells were transfected with empty vector (MDA/Neo), wild-type Bcl-2 (MDA/Bcl-2), or ΔBH4 Bcl-2 (Bcl-2 lacking ΔBH4 domain, MDA/ΔBH4 Bcl-2) (Fig. 6 A). Cells were treated with paclitaxel (50 nM) or left untreated (control) (Fig. 6 B). Fig. 6 B demonstrates that paclitaxel induced FasL expression in MDA/Neo cells. Overexpression of wild-type Bcl-2 (MDA/Bcl-2), but not ΔBH4 Bcl-2, inhibited paclitaxel-induced FasL expression (Fig. 6 B). We next examined the ability of ΔBH4 Bcl-2 to bind with calcineurin in MDA cells. MDA/neo, MDA/Bcl-2, and MDA/ΔBH4 Bcl-2 cells were treated with paclitaxel, and lysates were immunoprecipitated with anticalcineurin antibody and immunoblotted with anti–Bcl-2 antibody. Fig. 6 C demonstrates that wild-type Bcl-2 can be coimmunoprecipitated with calcineurin, and treatment of cells with low doses of paclitaxel significantly inhibited the Bcl-2–calcineurin interaction. As expected, ΔBH4 Bcl-2 was unable to heterodimerize with calcineurin.

Figure 6.

Bcl-2 interacts with calcineurin through its BH4 domain in inhibiting paclitaxel-induced FasL expression and apoptosis. (A) Western blot showing overexpressed wild-type Bcl-2 and ΔBH4 Bcl-2 in MDA-MB-231 cells. (B) MDA/Neo, MDA/ΔBH4 Bcl-2, and MDA/Bcl-2 cells were treated with paclitaxel (50 nM) for 48 h. Cells were harvested and lysed. FasL expression was detected by Western blot analysis. The same blot was reprobed with anti–β-actin antibody. (C) MDA/Neo, MDA/Bcl-2, and MDA/ΔBH4 Bcl-2 cells were treated with paclitaxel (50 nM) for 48 h. The cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with 10 μg of anticalcineurin antibody and 20 μl of protein A–Sepharose. The samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–Bcl-2 antibody. (D) MDA/Neo, MDA/Δloop Bcl-2, and MDA/Bcl-2 cells were treated with paclitaxel (200 nM) for 48 h. Top panel, cell lysates were run on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti–Bcl-2 antibody. Bottom panel, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti–Bcl-2 antibody, run on SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with anticalcineurin antibody. (E) MDA/Neo, MDA/ΔBH4 Bcl-2, MDA/Δloop Bcl-2, and MDA/Bcl-2 cells were treated with paclitaxel (0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 μM) for 48 h to measure apoptosis. Cells were stained with DAPI and visualized under fluorescence microscopy. Data (mean ± SE of quadruplicate determinations) represent one of three separate experiments that gave similar results.

As treatment of cells with high doses of paclitaxel causes more complete Bcl-2 phosphorylation, we sought to examine if phosphorylated Bcl-2 can bind to calcineurin. We and others have previously shown that the loop region of Bcl-2 is an important target for regulatory phosphorylation 59 60. MDA/Neo, MDA/Δloop Bcl-2 (which can not be phosphorylated), and MDA/Bcl-2 cells were treated with 200 nM paclitaxel for 48 h (Fig. 6 D). Treatment of MDA/Bcl-2 cells with high doses of paclitaxel causes phosphorylation of wild-type Bcl-2, whereas paclitaxel has no effect on Δloop Bcl-2 (phosphorylation-deficient mutant) (Fig. 6 D, top panel). In addition, phosphorylated Bcl-2 was unable to bind with calcineurin (Fig. 6 D, bottom panel). By comparison, Δloop Bcl-2 was not phosphorylated by paclitaxel and formed heterodimers with calcineurin. These data suggest that phosphorylation of Bcl-2 is essential for calcineurin to be released from the complex.

Because ΔBH4 Bcl-2 was not able to bind with calcineurin, we sought to examine the effects of this mutant on paclitaxel-induced apoptosis. Overexpression of wild-type Bcl-2 in MDA cells significantly inhibited paclitaxel-induced apoptosis, whereas overexpression of ΔBH4 Bcl-2 mutant had only a slight inhibiting effect (Fig. 6 E). In addition, overexpression of Δloop Bcl-2 completely inhibited paclitaxel-induced apoptosis. Taken together, these data suggest that the ΔBH4 domain of Bcl-2 plays a significant role in heterodimerizing with calcineurin and inhibiting paclitaxel-induced apoptosis, and the phosphorylation of the Bcl-2 loop domain allosterically interferes with the BH4–calcineurin interaction.

Bcl-2 Blocks Paclitaxel-induced FasL Promoter Activity.

It has been shown that the FasL promoter contains two NFAT binding sites 42 43. We next addressed the functional importance of the two NFAT sites for paclitaxel-mediated FasL expression by generating mutations at one or both NFAT binding sites. Two FasL sites were also mutated in the context of the full length, 486-bp FasL reporter so that FasL expression in this system would not kill the cells. Jurkat cells were transfected with the wild-type reporter or double mutant reporter constructs and then left untreated or treated with paclitaxel. As shown in Fig. 7 A, treatment of JT/Neo cells transfected with wild-type FasL reporter resulted in a 10-fold increase in luciferase activity relative to control cells. In contrast, the reporter containing mutations in both NFAT sites exhibited no luciferase production over control in JT/Neo cells (Fig. 7 A). Interestingly, overexpression of the Bcl-2 gene in JT cells (JT/Bcl-2) inhibited wild-type FasL promoter activity in cells treated with paclitaxel. As expected, low levels of luciferase activity were detected in cells transfected with the double NFAT mutant reporter plasmid in JT/Bcl-2 cells (Fig. 7 A).

Figure 7.

NFAT sites play important roles in FasL promoter activation. (A) Jurkat cells (JT/Neo and JT/Bcl-2) were transfected with 70 μg of the wild-type 486-bp FasL reporter (FasL-486) or a reporter containing mutations in both the distal and proximal NFAT sites (double mutant). Transfectants were left untreated (control) or treated with paclitaxel (100 nM) for 48 h. Cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity. Data are expressed as arbitrary luciferase light units and are representative of four independent experiments. Error bars, SE of triplicate samples. (B) MDA/Neo and MDA/Bcl-2 cells were transfected with 70 μg of the wild-type 486-bp FasL reporter (FasL-486) or a reporter containing mutations in both the distal and proximal NFAT sites (double mutant). Transfectants were left untreated (control) or treated with paclitaxel (100 nM) for 48 h. Cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity. Data are expressed as arbitrary luciferase light units and are representative of four independent experiments. Error bars, SE of triplicate samples.

We next sought to examine the FasL promoter activation in MDA-MB-231 cells that do not express endogenous Bcl-2 protein. Paclitaxel treatment of MDA/Neo cells transfected with wild-type FasL reporter resulted in a 12-fold increase in luciferase activity relative to control cells. In contrast, overexpression of Bcl-2 blocked FasL promoter activation in paclitaxel-treated MDA/Bcl-2 cells (Fig. 7 B). By comparison, low levels of luciferase activity were detected in cells transfected with double NFAT mutant reporter plasmid in MDA/Bcl-2 cells (Fig. 7 A). Collectively, these results indicate that Bcl-2 blocked FasL transcription by inhibiting NFAT activity.

Discussion

Involvement of FasL in Apoptosis.

Activation of T cells results in expression of FasL and induction of apoptosis. In comparison to activation-induced FasL expression in T cells, FasL is constitutively expressed in other selected cell types. The identification of FasL expression on cells in immune privileged sites, such as testis 9 and the anterior chamber of the eye 10, has suggested that FasL may be important in tolerance induction and immunosuppression. Indeed, inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber of the eye undergo Fas-mediated apoptosis and show a systemic tolerance to herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) infection 10. In addition to immune cells, expression of FasL on human tumors, including colon 61, hepatocellular carcinoma 62 63, melanoma 12, and lung carcinoma 13 has been demonstrated; this expression on cancer cells may be involved in induction of apoptosis in Fas-expressing T cells.

Here we have shown that paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in lymphoid and breast tumor cells is mediated at least in part by increased expression of FasL. As Fas is constitutively expressed in most tumors cells, induction of FasL would be an amplification signal for tumor cell apoptosis. FasL-neutralizing antibody nearly completely abrogates apoptosis induced by microtubule poisons such as paclitaxel and vinblastine.

Recent studies have suggested that environmental stress mediated by exposure to gamma irradiation 53, UV light 54, and anticancer drugs such as etoposide or doxorubicin 52 induces upregulation of Fas receptors and ligands, resulting in autocrine or paracrine cell death. However, the level of Fas expression is only one of the factors regulating the susceptibility to Fas-mediated apoptosis 64. Exposure to radiation, anticancer drugs, or other forms of stress may lead to apoptosis, not only by increasing surface expression of Fas, but also by affecting intracellular signaling molecules activated upon Fas ligation. Indeed, numerous drug-resistant cell lines were also found to be resistant to Fas-mediated apoptosis 65. These findings support the hypothesis that apoptosis mediated by both chemotherapeutic agents and physiologic stimuli such as Fas ligation may share common downstream effector molecules.

Bcl-2 Inhibits NFAT Translocation to the Nucleus by Binding to Calcineurin but not NFAT.

The expression of FasL is inhibited by immunosuppressive agents CsA and FK506 47 50 66 67, suggesting that the transcription factor NFAT is involved in FasL induction. Our data demonstrate that the FK506 analogue ascomycin inhibits paclitaxel-induced FasL expression and blocks apoptosis. These data suggest that the calcineurin–NFAT pathway is involved in the control of FasL expression and consequent paclitaxel-induced apoptosis.

Current evidence indicates that both nuclear import and export of NFAT can be regulated dynamically 68 69. In T cells, relatively profound and sustained cytosolic Ca2+ transients, such as those that occur after antigen receptor engagement, appear to be necessary to activate calcineurin and counterbalance the effects of processes that effect nuclear export of NFAT 70. It has recently been suggested that the Ca2+ signals of shorter duration elicited by activation of the Gαq receptors may preferentially activate the putative negative regulatory processes 71, whereas activation of calcineurin, dephosphorylation of NFAT, and its subsequent nuclear import require Ca2+ transients of longer duration. Recent studies have provided evidence that a nuclear kinase activity is involved in rephosphorylating NFAT and exporting it to the cytosol as a means for terminating its transcriptional activity 72. Although protein kinase A and glycogen synthase kinase 3 have been implicated as the major NFAT kinases in Jurkat T cells, calmodulin-dependent kinases appear to have some NFAT nuclear export activity as well as a heterotopic expression system 70.

We have shown that NFAT regulates the induction of FasL upon paclitaxel treatment in Jurkat T cells and breast cancer cells. It has been demonstrated that the FasL promoter contains two NFAT binding sites (bp −263 to −283 relative to the FasL translation). Furthermore, the ability of a mutation in this NFAT site (within the context of a 486-bp FasL reporter) to prevent reporter activity in lymphocytes illustrates that this response element is critical for the regulated expression of FasL in our studies. In addition to the observation that CsA inhibits expression of FasL 47 50 67 in lymphocytes and that NFAT-deficient mice do not inducibly express FasL 73, these results strongly suggest that NFAT transcription factors are critical for the regulation of FasL expression in lymphocytes and breast carcinoma. The induction of FasL reporter expression is blocked by overexpression of Bcl-2.

The comparison of the NFAT binding region of the FasL promoter with IL-2 and TNF-α promoters provides some insight into the regulation of these genes. AP-1 (activator protein 1) binding sequences are adjacent to NFAT sites in the IL-2 promoter 74, whereas the NFAT sites from the FasL promoter do not include any surrounding predicted AP-1 binding sequences. In contrast, the sequence of the FasL promoter NFAT binding site is similar to that of a previously reported NFAT site within the TNF-α promoter 75. Because of the structural and functional similarities between TNF-α and FasL, it is intriguing to speculate that the conserved NFAT regulatory sequences within the promoters of these genes may have arisen from a common ancestral apoptosis-inducing gene.

As FasL plays an important role in control of lymphocyte apoptosis, and, according to our data, drug-induced apoptosis, we have examined the intracellular mechanism of FasL induction in human T cells and breast cancer cells. The mechanism by which Bcl-2 inhibits drug-induced FasL expression and apoptosis is not known. We have demonstrated that Bcl-2 inhibits paclitaxel-induced NFAT translocation to the nucleus through interactions with calcineurin. Indeed, Bcl-2 does not bind to NFAT directly, as has also been reported by others 57. The BH4 domain of Bcl-2 binds to calcineurin and thereby inhibits the translocation of NFAT. Calcium-dependent phosphorylation of calcineurin is essential for activation of NFAT and subsequent translocation to the nucleus.

The inhibition of paclitaxel-induced NFAT translocation and apoptosis by Bcl-2 may be one of the mechanisms by which Bcl-2 regulates apoptosis. We have previously shown that microtubule-damaging drugs (paclitaxel, vincristine, and vinblastine) induced Bcl-2 phosphorylation and apoptosis. Indeed, phosphorylated Bcl-2 loses its antiapoptotic function and is unable to heterodimerize with the proapoptotic partner Bax. This free Bax itself can induce apoptosis. Therefore, phosphorylation of Bcl-2 may result in at least two events: (a) release of Bax and (b) failure to hold on to or sequester calcineurin.

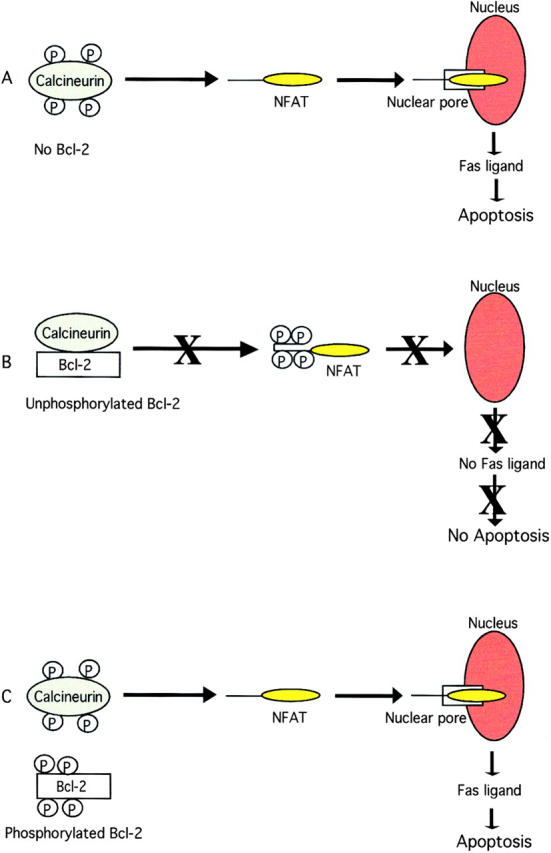

Model: Inhibition of Paclitaxel-induced Apoptosis by Bcl-2.

Collectively, these data support a model in which microtubule-damaging drugs such as paclitaxel stimulate an increase in intracellular free Ca2+ that activates calcineurin, which results in NFAT nuclear translocation, FasL expression, and apoptosis (Fig. 8 A). Apoptosis can be blocked either by treatment of cells with anti-FasL antibody (Fig. 1) or by overexpression of Bcl-2. Bcl-2 sequesters calcineurin, which results in blockage of NFAT nuclear translocation, FasL expression, and apoptosis (Fig. 8 B). All of the phosphorylation sites of Bcl-2 are located within the loop region (amino acid 32–80). The loop region deletion mutant Bcl-2 (Δloop Bcl-2) cannot be phosphorylated and does not release calcineurin from the complex after paclitaxel exposure, and it becomes hyperfunctional in inhibiting drug-induced apoptosis. The inhibition of FasL translocation by Bcl-2 can be overcome by treatment of cells with high doses of paclitaxel (>100 nM) (Fig. 8 C). Treatment of cells with high doses of paclitaxel results in inactivation of Bcl-2 through phosphorylation. Phosphorylated Bcl-2 cannot bind calcineurin, and NFAT activation and FasL expression can occur after Bcl-2 phosphorylation.

Figure 8.

Model for the inhibition of NFAT signaling by Bcl-2. (A) Treatment of cells with paclitaxel results in calcineurin activation, NFAT nuclear translocation, FasL expression, and apoptosis. (B) Unphosphorylated Bcl-2 binds to calcineurin and blocks NFAT nuclear translocation, FasL expression, and apoptosis. (C) Phosphorylation of Bcl-2 results in release of calcineurin from the complex, translocation of NFAT to the nucleus, and induction of FasL expression and apoptosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Charles Filburn for assisting us with confocal microscopy work. We also extend our sincere thanks to Dr. Stanley J. Korsmeyer (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA) for providing the Bcl-2 expression vector. We are grateful to Dr. Gary Koretzky (University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA) for providing FasL promoter–luciferase constructs and JT/mut CD95 (DD3) cell line.

Footnotes

1used in this paper: L, ligand; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T lymphocytes; PI, propidium iodide

R.K. Srivastava is a recipient of the National Research Council Fellowship.

References

- Watanabe-Fukunaga R., Brannan C.I., Copeland N.G., Jenkins N.A., Nagata S. Lymphoproliferation disorder in mice explained by defects in Fas antigen that mediates apoptosis. Nature. 1992;356:314–317. doi: 10.1038/356314a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leithauser F., Dhein J., Mechtersheimer G., Koretz K., Bruderlein S., Henne C., Schmidt A., Debatin K.M., Krammer P.H., Moller P. Constitutive and induced expression of APO-1, a new member of the nerve growth factor/tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, in normal and neoplastic cells. Lab. Invest. 1993;69:415–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French L.E., Hahne M., Viard I., Radlgruber G., Zanone R., Becker K., Muller C., Tschopp J. Fas and Fas ligand in embryos and adult miceligand expression in several immune-privileged tissues and coexpression in adult tissues characterized by apoptotic cell turnover. J. Cell Biol. 1996;133:335–343. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouvier E., Luciani M.F., Golstein P. Fas involvement in Ca2+-independent T cell–mediated cytotoxicity. J. Exp. Med. 1993;177:195–200. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arase H., Arase N., Saito T. Fas-mediated cytotoxicity by freshly isolated natural killer cells. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:1235–1238. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M., Suda T., Haze K., Nakamura N., Sato K., Kimura F., Motoyoshi K., Mizuki M., Tagawa S., Ohga S. Fas ligand in human serum. Nat. Med. 1996;2:317–322. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French L.E., Wilson A., Hahne M., Viard I., Tschopp J., MacDonald H.R. Fas ligand expression is restricted to nonlymphoid thymic components in situ. J. Immunol. 1997;159:2196–2202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe-Fukunaga R., Brannan C.I., Itoh N., Yonehara S., Copeland N.G., Jenkins N.A., Nagata S. The cDNA structure, expression, and chromosomal assignment of the mouse Fas antigen. J. Immunol. 1992;148:1274–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellgrau D., Gold D., Selawry H., Moore J., Franzusoff A., Duke R.C. A role for CD95 ligand in preventing graft rejection. Nature. 1995;377:630–632. doi: 10.1038/377630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith T.S., Brunner T., Fletcher S.M., Green D.R., Ferguson T.A. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis as a mechanism of immune privilege. Science. 1995;270:1189–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand S., Hofmann W.J., Hug H., Muller M., Otto G., Strand D., Mariani S.M., Stremmel W., Krammer P.H., Galle P.R. Lymphocyte apoptosis induced by CD95 (APO-1/Fas) ligand-expressing tumor cells—a mechanism of immune evasion? Nat. Med. 1996;2:1361–1366. doi: 10.1038/nm1296-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahne M., Rimoldi D., Schroter M., Romero P., Schreier M., French L.E., Schneider P., Bornand T., Fontana A., Lienard D. Melanoma cell expression of Fas(Apo-1/CD95) ligandimplications for tumor immune escape. Science. 1996;274:1363–1366. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehans G.A., Brunner T., Frizelle S.P., Liston J.C., Salerno C.T., Knapp D.J., Green D.R., Kratzke R.A. Human lung carcinomas express Fas ligand. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1007–1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.Y., Rubin M.A., Omene C., Lederman S., Stein C.A. Fas ligand is constitutively secreted by prostate cancer cells in vitro. Clin. Cancer Res. 1998;4:1803–1811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata S., Golstein P. The Fas death factor. Science. 1995;267:1449–1456. doi: 10.1126/science.7533326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata S. A death factor—the other side of the coin. Behring. Inst. Mitt. 1996;97:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T., Suda T., Fukuyama H., Adachi M., Nagata S. Essential roles of the Fas ligand in the development of hepatitis. Nat. Med. 1997;3:409–413. doi: 10.1038/nm0497-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chervonsky A.V., Wang Y., Wong F.S., Visintin I., Flavell R.A., Janeway C.A., Jr., Matis L.A. The role of Fas in autoimmune diabetes. Cell. 1997;89:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano C., Stassi G., De Maria R., Todaro M., Richiusa P., Papoff G., Ruberti G., Bagnasco M., Testi R., Galluzzo A. Potential involvement of Fas and its ligand in the pathogenesis of Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Science. 1997;275:960–963. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M.R., Terasaki S., Itoh J., Katoh H., Yonehara S., Nose M. Rheumatic diseases in an MRL strain of mice with a deficit in the functional Fas ligand. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1054–1063. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh N., Imagawa A., Hanafusa T., Waguri M., Yamamoto K., Iwahashi H., Moriwaki M., Nakajima H., Miyagawa J., Namba M. Requirement of Fas for the development of autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:613–618. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.4.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman J.A. Apoptosis induced by anticancer drugs. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1992;11:121–139. doi: 10.1007/BF00048059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietenpol J.A., Papadopoulos N., Markowitz S., Willson J.K., Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B. Paradoxical inhibition of solid tumor cell growth by bcl2. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3714–3717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldar S., Basu A., Croce C.M. Bcl2 is the guardian of microtubule integrity. Cancer Res. 1997;57:229–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava R.K., Srivastava A.R., Korsmeyer S.J., Nesterova M., Cho-Chung Y.S., Longo D.L. Involvement of microtubules in the regulation of Bcl2 phosphorylation and apoptosis through cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:3509–3517. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell T.J., Korsmeyer S.J. Progression from lymphoid hyperplasia to high-grade malignant lymphoma in mice transgenic for the t(14; 18) Nature. 1991;349:254–256. doi: 10.1038/349254a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser A., Harris A.W., Cory S. E mu-bcl-2 transgene facilitates spontaneous transformation of early pre-B and immunoglobulin-secreting cells but not T cells. Oncogene. 1993;8:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linette G.P., Hess J.L., Sentman C.L., Korsmeyer S.J. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma in lckpr-bcl-2 transgenic mice. Blood. 1995;86:1255–1260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veis D.J., Sorenson C.M., Shutter J.R., Korsmeyer S.J. Bcl-2-deficient mice demonstrate fulminant lymphoid apoptosis, polycystic kidneys, and hypopigmented hair. Cell. 1993;75:229–240. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80065-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma A., Pena J.C., Chang B., Margosian E., Davidson L., Alt F.W., Thompson C.B. Bclx regulates the survival of double-positive thymocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:4763–4767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoyama N., Wang F., Roth K.A., Sawa H., Nakayama K., Negishi I., Senju S., Zhang Q., Fujii S. Massive cell death of immature hematopoietic cells and neurons in Bcl-x-deficient mice. Science. 1995;267:1506–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.7878471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N. Taxol-induced polymerization of purified tubulin. Mechanism of action. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:10435–10441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagosklonny M.V., Giannakakou P., el-Deiry W.S., Kingston D.G., Higgs P.I., Neckers L., Fojo T. Raf-1/bcl-2 phosphorylationa step from microtubule damage to cell death. Cancer Res. 1997;57:130–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodi D.J., Janes R.W., Sanganee H.J., Holton R.A., Wallace B.A., Makowski L. Screening of a library of phage-displayed peptides identifies human bcl-2 as a taxol-binding protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;285:197–203. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldar S., Basu A., Croce C.M. Serine-70 is one of the critical sites for drug-induced Bcl2 phosphorylation in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1609–1615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S.L., Crabtree G.R. The mechanism of action of cyclosporin A and FK506. Immunol. Today. 1992;13:136–142. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90111-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D.L., Hural J., Tara D., Timmerman L.A., Henkel G., Brown M.A. Nuclear factor of activated T cells is associated with a mast cell interleukin 4 transcription complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:228–235. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerill G.W., Bert A.G., Ryan G.R., Gamble J.R., Vadas M.A., Cockerill P.N. Regulation of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and E-selectin expression in endothelial cells by cyclosporin A and the T-cell transcription factor NFAT. Blood. 1995;86:2689–2698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss V., Abbott K.L., Wang X.F., Pavlath G.K., Murphy T.J. The cyclosporin A-sensitive nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) proteins are expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells. Differential localization of NFAT isoforms and induction of NFAT-mediated transcription by phospholipase C-coupled cell surface receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:19664–19671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho A.M., Jain J., Rao A., Hogan P.G. Expression of the transcription factor NFATp in a neuronal cell line and in the murine nervous system. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:28181–28186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoey T., Sun Y.L., Williamson K., Xu X. Isolation of two new members of the NF-AT gene family and functional characterization of the NF-AT proteins. Immunity. 1995;2:461–472. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linette G.P., Li Y., Roth R.K., Korsmeyer S.J. Cross talk between cell death and cell cycle progressionBcl-2 regulates NFAT-mediated activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:9545–9552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latinis K.M., Norian L.A., Eliason S.L., Koretzky G.A. Two NFAT transcription factor binding sites participate in the regulation of CD95 (Fas) ligand expression in activated human T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:31427–31434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latinis K.M., Carr L.L., Peterson E.J., Norian L.A., Eliason S.L., Koretzky G.A. Regulation of CD95 (Fas) ligand expression by TCR-mediated signaling events. J. Immunol. 1997;158:4602–4611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz-Heppelmann C.J., Algeciras A., Badley A.D., Paya C.V. Transcriptional regulation of the human FasL promoter-enhancer region. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:4416–4423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clipstone N.A., Crabtree G.R. Identification of calcineurin as a key signalling enzyme in T-lymphocyte activation. Nature. 1992;357:695–697. doi: 10.1038/357695a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson E.J., Latinis K.M., Koretzky G.A. Molecular characterization of a CD95 signaling mutant. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1047–1053. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199806)41:6<1047::AID-ART11>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anel A., Buferne M., Boyer C., Schmitt-Verhulst A.M., Golstein P. T cell receptor-induced Fas ligand expression in cytotoxic T lymphocyte clones is blocked by protein tyrosine kinase inhibitors and cyclosporin A. Eur. J. Immunol. 1994;24:2469–2476. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderson M.R., Tough T.W., Davis-Smith T., Braddy S., Falk B., Schooley K.A., Goodwin R.G., Smith C.A., Ramsdell F., Lynch D.H. Fas ligand mediates activation-induced cell death in human T lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:71–77. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner T., Mogil R.J., LaFace D., Yoo N.J., Mahboubi A., Echeverri F., Martin S.J., Force W.R., Lynch D.H., Ware C.F. Cell-autonomous Fas (CD95)/Fas-ligand interaction mediates activation-induced apoptosis in T-cell hybridomas. Nature. 1995;373:441–444. doi: 10.1038/373441a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhein J., Walczak H., Baumler C., Debatin K.M., Krammer P.H. Autocrine T-cell suicide mediated by APO-1/(Fas/CD95) Nature. 1995;373:438–441. doi: 10.1038/373438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju S.T., Panka D.J., Cui H., Ettinger R., el-Khatib M., Sherr D.H., Stanger B.Z., Marshak-Rothstein A. Fas(CD95)/FasL interactions required for programmed cell death after T-cell activation. Nature. 1995;373:444–448. doi: 10.1038/373444a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulda S., Sieverts H., Friesen C., Herr I., Debatin K.M. The CD95 (APO-1/Fas) system mediates drug-induced apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3823–3829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reap E.A., Roof K., Maynor K., Borrero M., Booker J., Cohen P.L. Radiation and stress-induced apoptosisa role for Fas/Fas ligand interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:5750–5755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehemtulla A., Hamilton C.A., Chinnaiyan A.M., Dixit V.M. Ultraviolet radiation-induced apoptosis is mediated by activation of CD-95 (Fas/APO-1) J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25783–25786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg E.V., Ward S.B. A dynamic assembly of diverse transcription factors integrates activation and cell-type information for interleukin 2 gene regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:9358–9365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao A., Luo C., Hogan P.G. Transcription factors of the NFAT familyregulation and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997;15:707–747. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki F., Kondo E., Akagi T., McKeon F. Suppression of signalling through transcription factor NF-AT by interactions between calcineurin and Bcl-2. Nature. 1997;386:728–731. doi: 10.1038/386728a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuret-Carnahan J., Bossu J.L., Feltz A., Langley K., Aunis D. Effect of taxol on secretory cellsfunctional, morphological, and electrophysiological correlates. J. Cell Biol. 1985;100:1863–1874. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.6.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava R.K., Mi Q.S., Hardwick J.M., Longo D.L. Deletion of the loop region of Bcl-2 completely blocks paclitaxel-induced apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:3775–3780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B.S., Minn A.J., Muchmore S.W., Fesik S.W., Thompson C.B. Identification of a novel regulatory domain in Bcl-XL and Bcl-2. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1997;16:968–977. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell J., O'Sullivan G.C., Collins J.K., Shanahan F. The Fas counterattackFas-mediated T cell killing by colon cancer cells expressing Fas ligand. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:1075–1082. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand S., Galle P.R. Immune evasion by tumoursinvolvement of the CD95 (APO-1/Fas) system and its clinical implications. Mol. Med. Today. 1998;4:63–68. doi: 10.1016/S1357-4310(97)01191-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand S., Hofmann W.J., Grambihler A., Hug H., Volkmann M., Otto G., Wesch H., Mariani S.M., Hack V., Stremmel W. Hepatic failure and liver cell damage in acute Wilson's disease involve CD95 (APO-1/Fas) mediated apoptosis. Nat. Med. 1998;4:588–593. doi: 10.1038/nm0598-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach D., Boldin M., Varfolomeev E., Beyaert R., Vandenabeele P., Fiers W. Cell death induction by receptors of the TNF familytowards a molecular understanding. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:96–106. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00553-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Los M., Herr I., Friesen C., Fulda S., Schulze-Osthoff K., Debatin K.M. Cross-resistance of CD95- and drug-induced apoptosis as a consequence of deficient activation of caspases (ICE/Ced-3 proteases) Blood. 1997;90:3118–3129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner T., Yoo N.J., Griffith T.S., Ferguson T.A., Green D.R. Regulation of CD95 ligand expressiona key element in immune regulation? Behring. Inst. Mitt. 1996;97:161–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner T., Yoo N.J., LaFace D., Ware C.F., Green D.R. Activation-induced cell death in murine T cell hybridomas. Differential regulation of Fas (CD95) versus Fas ligand expression by cyclosporin A and FK506. Int. Immunol. 1996;8:1017–1026. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.7.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff V.A., Leach K.L. Direct demonstration of NFATp dephosphorylation and nuclear localization in activated HT-2 cells using a specific NFATp polyclonal antibody. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:22602–22607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman L.A., Clipstone N.A., Ho S.N., Northrop J.P., Crabtree G.R. Rapid shuttling of NF-AT in discrimination of Ca2+ signals and immunosuppression. Nature. 1996;383:837–840. doi: 10.1038/383837a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals C.R., Sheridan C.M., Turck C.W., Gardner P., Crabtree G.R. Nuclear export of NF-ATc enhanced by glycogen synthase kinase-3. Science. 1997;275:1930–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss V., Wang X., Koppelman L.F., Xu K., Murphy T.J. Histamine induces nuclear factor of activated T cell-mediated transcription and cyclosporin A-sensitive interleukin-8 mRNA expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;54:264–272. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki F., Price E.R., Milan D., McKeon F. Role of kinases and the phosphatase calcineurin in the nuclear shuttling of transcription factor NF-AT4. Nature. 1996;382:370–373. doi: 10.1038/382370a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge M.R., Ranger A.M., Charles de la Brousse F., Hoey T., Grusby M.J., Glimcher L.H. Hyperproliferation and dysregulation of IL-4 expression in NF-ATp-deficient mice. Immunity. 1996;4:397–405. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao A. NF-ATpa transcription factor required for the co-ordinate induction of several cytokine genes. Immunol. Today. 1994;15:274–281. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai E.Y., Yie J., Thanos D., Goldfeld A.E. Cell-type-specific regulation of the human tumor necrosis factor alpha gene in B cells and T cells by NFATp and ATF-2/JUN. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:5232–5244. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]