Abstract

The many binding studies of monoclonal immunoglobulin (Ig) produced by plasmacytomas have found no universally common binding properties, but instead, groups of plasmacytomas with specific antigen-binding activities to haptens such as phosphorylcholine, dextrans, fructofuranans, or dinitrophenyl. Subsequently, it was found that plasmacytomas with similar binding chain specificities not only expressed the same idiotype, but rearranged the same light (VL) and heavy (VH) variable region genes to express a characteristic monoclonal antibody. In this study, we have examined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay five antibodies secreted by silicone-induced mouse plasmacytomas using a broader panel of antigens including actin, myosin, tubulin, single-stranded DNA, and double-stranded DNA. We have determined the Ig heavy and light chain V gene usage in these same plasmacytomas at the DNA and RNA level. Our studies reveal: (a) antibodies secreted by plasmacytomas bind to different antigens in a manner similar to that observed for natural autoantibodies; (b) the expressed Ig heavy genes are restricted in V gene usage to the VH-J558 family; and (c) secondary rearrangements occur at the light chain level with at least three plasmacytomas expressing both κ and λ light chain genes. These results suggest that plasmacytomas use a restricted population of B cells that may still be undergoing rearrangement, thereby bypassing the allelic exclusion normally associated with expression of antibody genes.

Keywords: V(D)J rearrangement, plasmacytoma, allelic exclusion, polyreactivity, V gene usage

Pristane- and mineral oil–induced mouse plasmacytomas (PCs)1 have proved to be invaluable in the study of Ab diversity, as well as in the chromosomal translocations associated with the development of late-stage B cell tumors. Virtually all mouse PCs exhibit a nonrandom chromosomal translocation between the Ig heavy chain or light chain gene and the c-Myc/Pvt 1 gene locus 1. As the original source of homogeneous Abs, PCs exhibit allelic exclusion and express a single unique heavy chain and light chain Ig molecule. Although some PCs have demonstrated reactivity to specific Ags (i.e., DNP, α1,3- and α1,6-dextrans, phosphorylcholine, levan, and β2,1- and β2,6-fructofuranans), a single predominant Ag or hapten target has not surfaced despite nearly three decades of research 2. In earlier studies, we found that natural polyreactive autoantibodies (NAAs) are an important component of the normal B cell repertoire, and that hybridomas derived from the spleens of BALB/c mice frequently exhibited polyreactivity to a panel of Ags including actin, myosin, tubulin, single-stranded (ss)DNA, and double-stranded (ds)DNA 3 4 5. Although NAAs are of low affinity and are encoded by essentially germline V region sequences 6, pathogenic Abs implicated in autoimmune disease are monospecific with higher affinity, and exhibit Ag-driven somatic mutation. In addition, considerable data have accumulated in humans indicating that the autoreactive repertoire frequently undergoes malignant transformation. This evidence has accumulated in studies of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), follicular non-Hodgkin lymphomas (FNHLs), and monoclonal Ig (for review, see reference 7). Paradoxically, the NAA specificity frequently found among human monoclonal Ig has not yet been reported in mouse PCs. In this report, we have searched for and found polyreactivity to several Ags, including myosin, dsDNA, and ssDNA in BALB/c silicone-induced PCs (SIPCs) of primarily the IgA heavy chain class.

Since the analysis of V region nucleotide sequences can also provide insight into the stage of B cell development at which clonal expansion occurs, as well as the putative role that an Ag-driven process could play in the selection of malignant B cell tumors, we have examined and identified restricted V region usage in the SIPC tumors. We have also observed Ab diversification in the form of secondary rearrangements that may be targeting the B cell population (B-1) in the periphery, apparently in an attempt to diverge from the polyreactive response and possible autoimmunity.

Materials and Methods

Tumors.

SIPCs were generated by three successive inoculations (on days 0, 60, and 120) of silicone gel into the peritoneal cavity of BALB/c or BALB/c.DBA/2N-Idh1-Pep3 congenic mice 8. The latency times for first generation tumors were SIPC3301 (227 d), SIPC3308 (190 d), SIPC3282 (152 d), SIPC3336 (220 d) and SIPC3385 (225 d). Tumors were transplanted either with or without priming into syngeneic mice, and several generations (g) were examined, including: SIPC3301 (g1, g2), SIPC3308 (g0, g1, g2), SIPC3282 (g0, g1, g3), SIPC3336 (g1, g2, g3, g4), and SIPC3385 (g0, g2, g3).

ELISA Assay.

SIPCs were screened for Ig secretion and Ab activity against actin, myosin, tubulin, dsDNA, and ssDNA 5. In brief, polystyrene flat-bottomed plates were coated with different Ags. After incubation with serial dilutions of each sample in duplicate, peroxidase-conjugated anti–mouse Ig was added; dilution medium alone was included as the negative control. Each assay was done in triplicate.

Southern Hybridization and Slot Blot Analysis.

Approximately 10 μg of EcoR1- or BamH1-digested genomic DNA was size separated on 0.7% agarose gels. After electrophoresis, the gels were acid (HCl) treated, alkaline treated, and neutralized in 3 M NaCl, 0.5 M Tris-Cl, pH 7.6. Southern transfers were made to Nytran Plus filters (Schleicher and Schuell), UV cross-linked, and hybridized to 32P-labeled DNA probes at 65°C with a final wash stringency of 0.2× SSC at 65°C. The probes used to detect light chain κ rearrangements were either the 1.1-kb HindIII-XbaI (intervening sequence [IVS]) or the 1.8-kb HindIII-XbaI (Jκ) fragments. For heavy chain Ig rearrangements, a 0.8-kb EcoR1 JH probe was used. Translocation to c-Myc or Pvt 1 was assayed by screening EcoR1- or BamH1-digested filters with a 1.7-kb exon 2 PstI (c-Myc) or a 1.7-kb cDNA (Pvt 1) probe.

For slot blot hybridizations, ∼1 μg of RNAs from BALB/c. DBA/2N congenic mouse liver and spleen, as well as from each of the SIPC tumors used in this study, were applied to Hybond (Nycomed Amersham plc) filters and hybridized to Ly1, recombination activating gene 1 (RAG-1) cDNA, Vλ, Vk-24, Vκ-1, or Cκ-specific probes. After hybridization, the filters were washed at 0.2× SSC at 65°C for 30 min.

Spectral Karyotyping (SKY™) of SIPC Tumors.

Although detailed methods have been reported elsewhere 9, metaphase cells were equilibrated in 2× SSC, digested with RNase A and pepsin, fixed in 1% formaldehyde, denatured in 70% formamide/2× SSC, and then dried. The fluorochromes, spectrum orange (dUTP conjugate; Vysis), rhodamine 110 (Perkin-Elmer), and Texas red (12-dUTP conjugate; Molecular Probes) were used for direct labeling, and the haptens biotin-16–dUTP and digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim Corp.) were used for indirect labeling. The probes were precipitated in an excess of mouse DNA (COT-1 DNA; GIBCO BRL), and hybridized at 37°C for 72 h in 50% formamide/SSC/dextran sulfate. After hybridization and washing (4× SSC/Tween 20), the biotin was visualized by avidin-Cy5 (Nycomed Amersham plc), and the digoxigenin-11–dUTP was visualized by mouse antidigoxigenin (Sigma Chemical Co.) followed by sheep anti–mouse Cy5.5 (Nycomed Amersham plc). Chromosomes were counterstained with 4,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and embedded in antifade solution (1,4-phenylenediamine, Sigma Chemical Co.). Spectral images were obtained on a Leica DMRBE epifluorescence microscope equipped with an SD200 SpectraCube® (Applied Spectral Imaging) and a customized triple bandpass optical filter. Spectrum-based classification of the raw spectral images was performed using the software SkyView (Applied Spectral Imaging).

Cloning and Subcloning of Rearranged V(D)J Genes.

Approximately 100 μg of genomic DNA from SIPC3336 was restricted with EcoR1 and subjected to low-melting (1.0%) gel electrophoresis. Bands corresponding to the rearranged V(D)J genes were excised, extracted with phenol, and precipitated with ethanol. Inserts were then ligated to either EMBL4 or λgt10 arms (EcoR1 digested). After ligation, the phage DNA was in vitro packaged and plated to densities of 125,000 per 20 × 20 cm LB plate. Benton-Davis transfer of the phage to nitrocellulose filters was followed by hybridization to 32P-labeled IVS or JH probes. Positive phage were mapped by restriction endonucleases, and inserts were subcloned into pGEM-4Z.

PCR Amplifications and Sequencing of Heavy and Light Chain Ig.

Total cellular RNA was extracted from tumor tissues by RNA PLUS solution (Bioprobe Systems), and first-strand synthesis was carried out as described previously 5. PCR amplifications were set up in 50-μl volumes containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.4, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 mM of each dNTP, 2 U of Taq DNA polymerase (GIBCO BRL), 50 pmol of each primer, and a 3 μl aliquot of the cDNA reaction. The primer sequences used to amplify specific heavy chain or light chain V regions are shown in Table . The primers for amplification of Ly1, RAG-1, and RAG-2 are as follows: CCTAGATATCCAGGTGGT (Ly1 5′), GTGTCCTGGCACCAGCTG (Ly1 3′), AGGATCTGCATTCTCAGA (RAG-1 5′), TCAGCTTGCCTGTGCTCA (RAG-1 3′), GTCTCCAACAGTCAGACA (RAG-2 5′), and GCTCTTGCTATCTGTACA (RAG-2 3′).

Table 1.

Primer Sequences Used in V Region–specific PCR Amplifications

| V region primers | |

|---|---|

| VH-SG1 | GTGCAGCTKMAGSAGTCRGG |

| VH-SG2 | CARCTGCARCARYCTGG |

| VH-SG3 | GTGAAGCTKSWSGARTCTGG |

| VH-SG4 | GTYCARCTKCARCAGTCTGG |

| VH13-3-5′ | GCTGAACTGGCAAAACCT |

| VH13-3-3′ | GTAATAGACTGCAGAGTC |

| Vκ1-FW1 | AGTCTTGGAGATCAAGCC |

| Vκ24-CDR1 | TCCTGCAGGTCTAGTAAG |

| Vκ24-FW3 | GCCTCAGGAGTCCCAGAC |

| Vκ1,2 | ATGTTGTGATGACCCA |

| Vκ4,5 | AAATTGTTCTCACCCA |

| Vκ8,14,15,19,21 | ACATTGTGMTGACHCA |

| Vκ9,12,13,31,33,34 | ACATCCAGATGACHCA |

| Vκ20 | AAACAACTGTGACCCA |

| Vkκ23 | ATATTGTGCTAACTCA |

| Vκ24,28 | RTATTGTGATGACYCA |

| Vλ | TTCCCAGGCTGTTGTGA |

| C region primers | |

| JH3 | GCAGAGAATCTTGGTCCT |

| IgG3 | GTCACTGCAGCCAGGGACCA |

| IgA | GATGGTGGGATTTCTCGCAGACTC |

| IgGX | CAGGGGCCAGTGGATAGAC |

| Jκ2 | CCTTAACACTTGATCTGA |

| Jκ4 | CTATTGATGCACAGGTTG |

| Cκ | ACACTCATTCCTGTTGAA |

| Cλ | GAGCTCTTCAGAGGAAGG |

Each PCR amplification product was purified by agarose gel electrophoresis, extracted, and then subcloned into the TOPO-TA vector following the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). Single bacterial colonies were isolated for direct sequencing. Sequencing was carried out according to the manufacturer's protocol (Promega). The nucleotide sequence data were analyzed, and comparisons were made with MacVector or Genetics Computer Group (GCG) software packages.

Results

SIPC Tumors Display Polyreactivity.

The ascites fluid of 33 different SIPC tumors was assessed for binding activity against actin, myosin, tubulin, ssDNA, and dsDNA by ELISA 10. We have focused on purified Abs from five of these tumors, each of which binds to at least one of the Ags from the panel. As far as heavy chain class, four out of the five SIPCs examined (SIPC3308, SIPC3301, SIPC3336, and SIPC3282) in this study expressed IgA (only SIPC3385 expressed IgG3). Although most Abs show higher reactivity to myosin, several are particularly reactive to dsDNA and ssDNA. The tumor SIPC3301 displays low reactivity with essentially all Ags on this panel. The SIPC3282, SIPC3308, SIPC3336, and SIPC3385 Abs were found to display a polyreactive binding activity (Table ).

Table 2.

Reactivity Pattern of SIPC-purified Abs against Various Antigens

| Abs | Isotype | Antigen activity as measured by ELISA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actin | Myosin | Tubulin | dsDNA | ssDNA | ||

| SIPC3385 | IgG3 | 390 ± 19.519 | 845 ± 31 | 869 ± 12.529 | 1,632 ± 368.501 | 1,835 ± 1 |

| SIPC3308 | IgA | 362 ± 1.732 | 1,178 ± 3.785 | 145 ± 17 | 287 ± 8.544 | 638 ± 8.504 |

| SIPC3301 | IgA | 219 ± 41.501 | 250 ± 31 | 56 ± 7.549 | 188 ± 5 | 240 ± 34 |

| SIPC3336 | IgA | 143 ± 1 | 1,253 ± 4 | 60 ± 2.645 | 126 ± 0 | 195 ± 12 |

| SIPC3282 | IgA | 924 ± 1 | 1,224 ± 2.081 | 454 ± 145.502 | 1,505 ± 64 | 1,978 ± 81 |

Cytogenetics of SIPC Tumors.

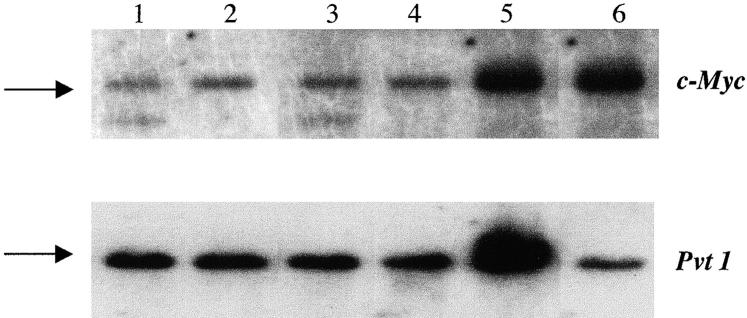

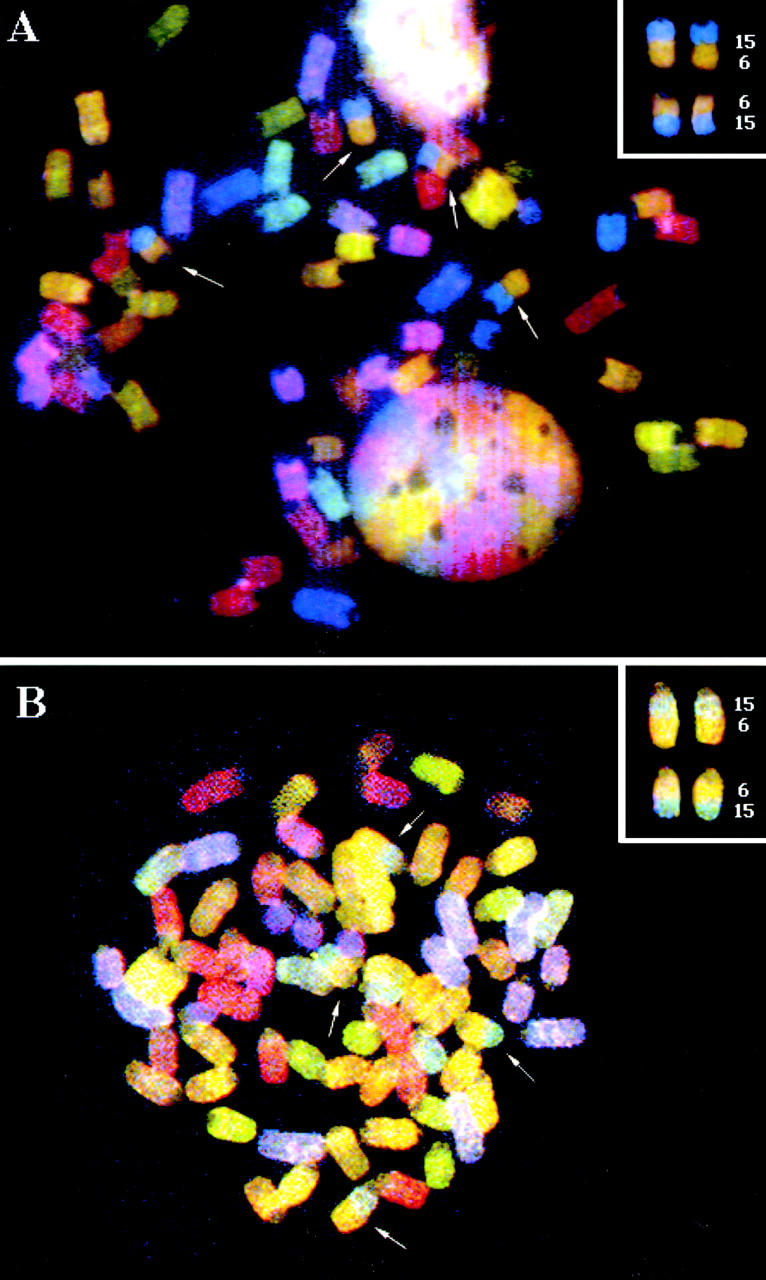

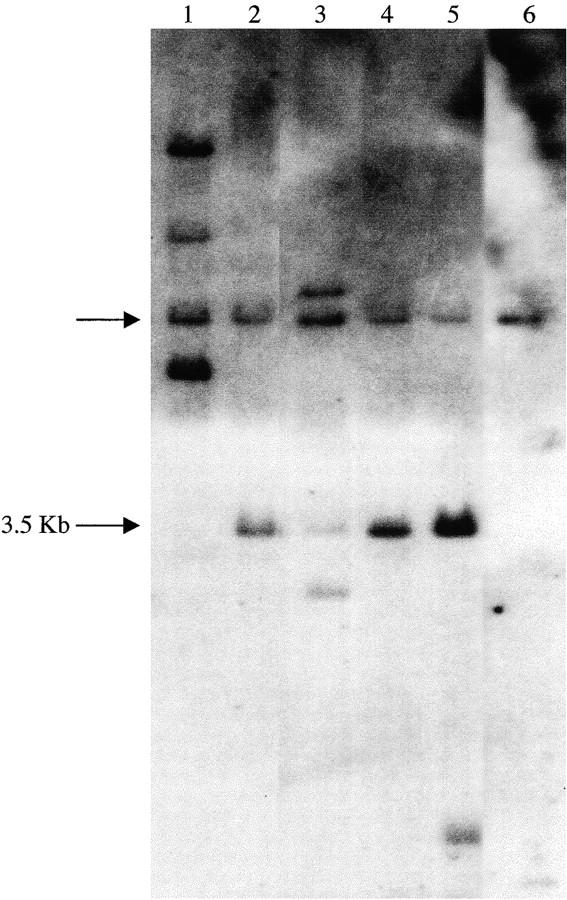

Cytogenetic studies have revealed that a majority of PCs contain reciprocal T(12;15) translocations 1. Alternatively, several SIPC tumors exhibit a reciprocal T(6;15) translocation (considered to be the variant translocation), as demonstrated by the SKY™ analysis performed on two representative SIPC tumors (Fig. 1). While SKY™ cytogenetics is a good indicator of T(12;15) or T(6;15) translocations, it is not entirely certain whether c-Myc or Pvt 1 is targeted by these translocations, as we have only found two SIPC tumors with c-Myc rearrangements (SIPC3385, SIPC3301) and no tumors with Pvt 1 rearrangements at the Southern hybridization level (Table , and Fig. 2). The assay for molecular rearrangement is based on utilization of a series of hybridization probes surrounding the major breakpoints of Pvt 1 or c-Myc, and by incorporating large restriction fragments into the analyses 11. The absence of detectable rearrangements with Pvt 1 or c-Myc in such a large number of SIPC tumors (Table , and data not shown) suggests that, in general, SIPC-associated translocations could reside outside the usual or more common breakpoint locations, and may not be detectable with the probes used in this study.

Figure 1.

SKY™ images of SIPC tumors with variant T(6;15) chromosomal translocations, (A) SIPC3308 and (B) SIPC3282. The arrows mark chromosomal translocations that have occurred between CHR6 (yellow) and CHR15 (blue). There are two copies of each T(6;15) and the reciprocal T(15;6).

Table 3.

Cytogenetics of SIPC Tumors

| Tumors | SKY™ analysis | Molecular rearrangement |

|---|---|---|

| SIPC3385 | T(12;15) | c-Myc (18 kb) |

| SIPC3308 | T(6;15) | NR |

| SIPC3301 | T(12;15) | c-Myc (18 kb) |

| SIPC3336 | T(6;15) | NR |

| SIPC3282 | T(6;15) | NR |

Figure 2.

Southern hybridization assay for c-Myc and Pvt 1 rearrangements in SIPC tumors. Shown top (c-Myc, EcoR1) and bottom (Pvt 1, BamH1) are the following tumors: lane 1, SIPC3385; lane 2, SIPC3308; lane 3, SIPC3301; lane 4, SIPC3336; lane 5, SIPC3282; and lane 6, BALB/c. Arrows depict the germline (nonrearranged fragments). Two samples (SIPC3385 and SIPC3301) contain rearranged bands with c-Myc, whereas no rearrangements are found with Pvt 1.

Ig VH Gene Expression.

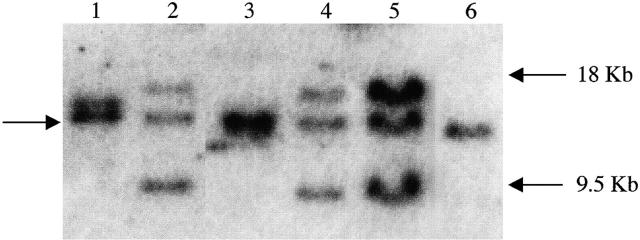

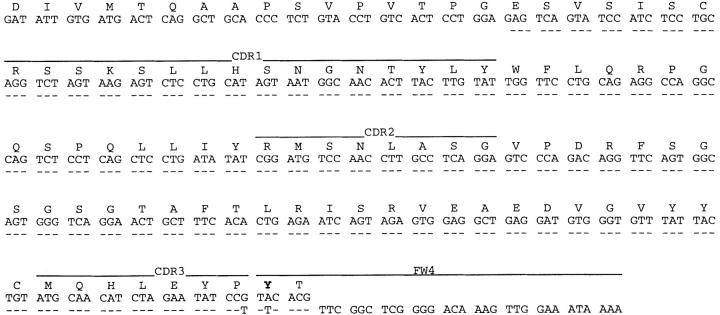

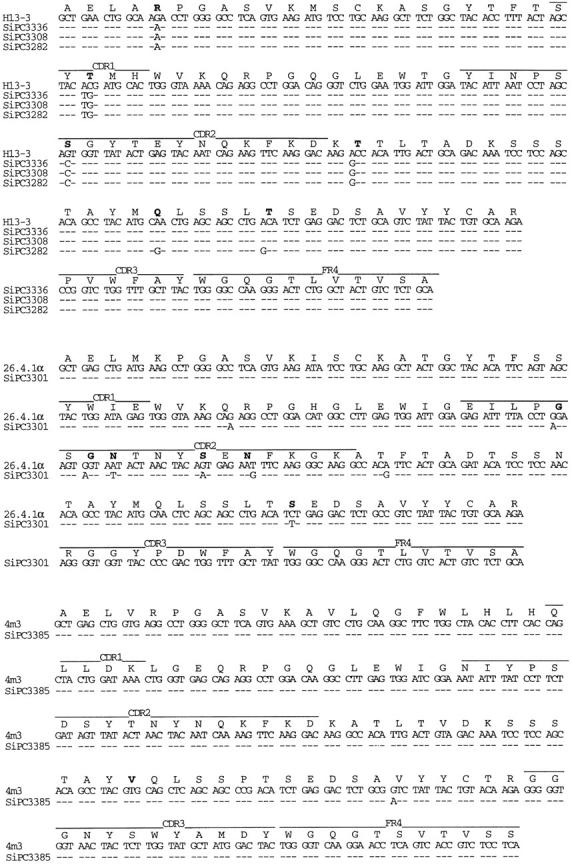

Initially, Ig heavy chain–specific rearrangements were identified in each tumor by Southern blot analysis using a JH probe (Fig. 3). Heavy chain-specific rearrangements were found in all tumors, including apparent rearrangements of both alleles in SIPC3385, SIPC3282, and SIPC3301. We also found shared rearrangements with both BamH1 (not shown) and EcoR1 digestions in SIPC3308, SIPC3336, and SIPC3282, suggesting the same VH gene may be expressed in these tumors. We cloned and sequenced the 3.5-kb EcoR1 fragment from SIPC3336, and established that the rearrangement consists of a member of the VH-J558 family (H13-3; reference 12) rearranged to DHSP2-9 and JH3. To more specifically determine VH gene usage in the SIPC tumors, we examined the expressed sequences by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (Fig. 4). Indeed, three of the SIPC tumors (SIPC3282, SIPC3336, and SIPC3308) that share the 3.5-kb EcoR1 rearrangement all use the same H13-3 gene from the VH-J558 family. We verified that this sequence was germline (nonmutated) by sequencing eight clones derived from the PCR product of BALB/c genomic DNA which was amplified by primer pairs specific for H13-3 (see Table ). Interestingly, these same three tumors have also rearranged to JH3, and use the same DH region (DHSP2-9) encoding the amino acid residues Trp-Phe. Although rearranged to JH3 and DHSP2-9 as well, SIPC3301 has a longer nucleotide addition sequence, and is in fact encoded by another member (26.4.1-α; reference 13) of the VH-J558 family. The RT-PCR product of SIPC3385 was also found to use a member of the VH-J558 family, but in this case the nitrophenyl-binding 4m3 VH gene 14. In SIPC3385, the rearrangement involves JH4 and another member of the DHSP2 family with N sequence additions. Analysis of the VH region sequences reveals somatic mutational activity with high replacement to silent (R/S) ratios, since all the SIPCs that express H13-3 exhibit four to six replacement changes with no accompanying silent base changes (Fig. 4). In the case of SIPC3385, we only find a single replacement in VH.

Figure 3.

JH rearrangements in SIPC tumors. Genomic DNAs from SIPC tumors and BALB/c liver were digested with EcoR1 and hybridized with the JH probe: lane 1, SIPC3385; lane 2, SIPC3308; lane 3, SIPC3301; lane 4, SIPC3336; lane 5, SIPC3282; and lane 6, BALB/c. An arrow (left) depicts the germline (nonrearranged) JH fragment, whereas the 3.5-kb EcoR1 rearrangement seen in several tumors is also highlighted.

Figure 4.

Nucleotide sequences of VH genes from SIPC tumors. The sequences obtained with the five SIPC tumors have been compared with the most homologous germline genes which are members of the VH-J558 family. Top: SIPC3336, SIPC3308, and SIPC3282 express VH13-3; middle: SIPC3301 expresses 26.4.1-α; bottom: SIPC3385 expresses 4ma. Dashes indicate sequence identities. Germline amino acids in bold indicate that they are replaced in SIPCs. These sequence data are available from EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ under accession nos. AF154880–AF154882, AF154909, and AF154910.

Ig VL Gene Expression.

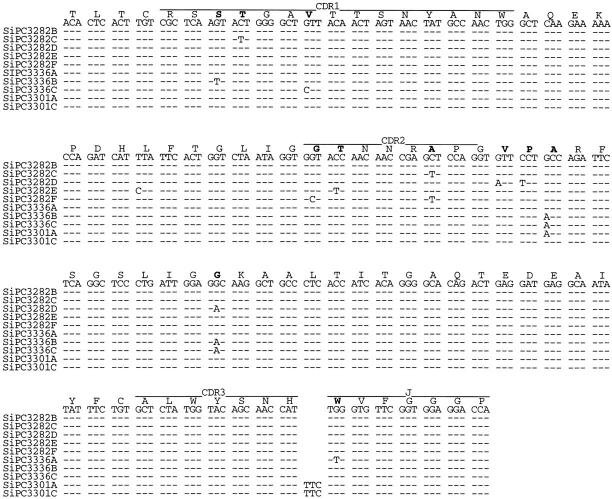

We examined the light chain–specific rearrangements of the SIPC tumors at the Southern hybridization level. The tumors SIPC3308, SIPC3336, and SIPC3282 all shared identical rearrangements with both EcoR1 (Fig. 5) and BamH1 (data not shown) digestions. By cloning and sequencing the 18-kb EcoR1 fragment (from SIPC3336), we obtained a Vκ24C-Jκ4 15 sequence suggesting that SIPC3308, SIPC3336, and SIPC3282 may all share the same rearrangement. When we performed PCR amplifications in each of these tumors with primers specific for Vκ24C and Jκ4, we obtained positive products that were identical as well as nonmutated (Fig. 6). To test whether the Vκ24C-Jκ4 rearrangement is productive (expressed), we used Vκ24C and Cκ–specific primers in RT-PCR assays, and again, found positive products in each of these tumors (data not shown). Although the nature of the common 9.5-kb EcoR1 band found in SIPC3308, SIPC3336, and SIPC3282 is uncertain at the moment, we do know it must be related to the rearrangement to Vκ24C-Jκ4, since they are always found in association with the productive rearrangement in each of these tumors. Southern blots with a Cκ only (minus IVS) probe result in no hybridization to the 9.5-kb EcoR1 band, proving this fragment to be nonproductive and probably a byproduct of the rearrangement process (data not shown). Both SIPC3385 and SIPC3301 exhibit different rearrangements at the Southern blot level. Therefore, we performed RT-PCR amplifications to determine the expressed Vκ gene for these two tumors as well. The tumor SIPC3385 was found to express a nonmutated Vκ21G-Jκ2 sequence 16, whereas SIPC3301 expressed a nonmutated Vκ34C-Jκ2 sequence 17.

Figure 5.

IgL rearrangements of SIPC tumors. Genomic DNAs from SIPC tumors and BALB/c liver were digested with EcoR1 and hybridized with the IVS probe: lane 1, SIPC3385; lane 2, SIPC3308; lane 3, SIPC3301; lane 4, SIPC3336; lane 5, SIPC3282; and lane 6, BALB/c. An arrow (left) depicts the germline (nonrearranged) Igκ fragment, whereas the 18 and 9.5-kb EcoR1 rearrangements seen in SIPC3308, SIPC3336, and SIPC3282 are also highlighted (right).

Figure 6.

Nucleotide sequence of the Vκ24C-Jκ4 gene from the SIPC tumors. Sequences obtained from SIPC3282, SIPC3336, and SIPC3308 (bottom line) have been compared to that of the germline Vκ24C (reference 15). Dashes indicate sequence identities. Substitutions at the amino acid level are indicated in bold. These sequence data are available from EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ under accession no. AF154911.

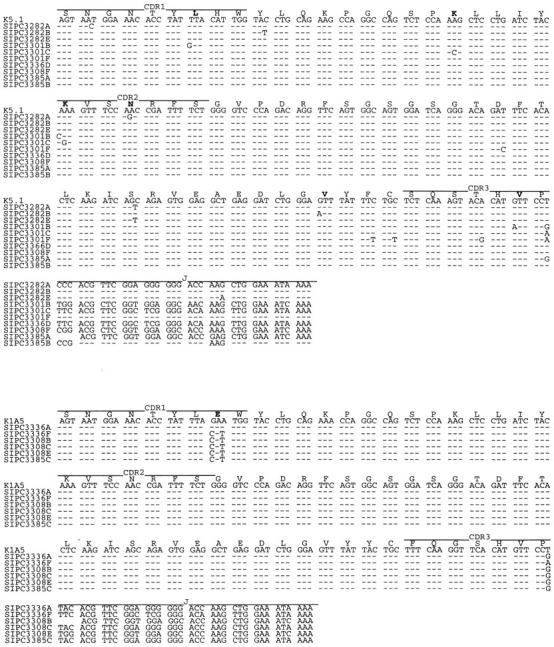

In the process of verifying the expressed Vκ sequences discussed above, we subjected all the SIPC tumors to RT-PCR amplification using sets of primers (Table ) that were cross-reactive to each of the Vκ and Vλ gene families. Unexpectedly, we found that in addition to expression of Vκ24C-Jκ4, Vκ21G-Jκ2, and Vκ34C-Jκ2, each of the SIPC tumors expressed an additional Igκ or Igλ light chain gene, a finding in violation of allelic exclusion normally associated with Ab gene expression 18 19 20. All the SIPC tumors examined in this study were found to express either Vκ1A or Vκ1C 21 22 rearranged to either Jκ1, Jκ2, or Jκ4 segments (Fig. 7). Furthermore, we also found that both Vκ1C sequences and Vκ1A sequences exhibited some level of somatic mutation (as found in the VH above). With a 1:1 R/S ratio for the whole V region (and a higher R/S ratio in CDR2) in Vκ1A, only minimal levels of Ag selection are evident. We also found three tumors, SIPC3282, SIPC3301, and SIPC3336, that express Vλ1-Cλ1 sequences (Fig. 8). In this instance, these sequences are mutated (all changes are replacements), and there is evidence of clonal divergence. Interestingly, no Vλ sequences were found in SIPC3385 or SIPC3308. This later result is important, as it is a critical distinction between SIPC3308 and SIPC3336.

Figure 7.

Nucleotide sequences of Vκ1 genes expressed in SIPC tumors. Sequences were obtained from individual clones (designated A–F) of SIPC3282, SIPC3301, SIPC3336, SIPC3308, and SIPC3385. Although multiple subclones with identical sequences were obtained, only representative sequences that differ are shown. The sequences are compared with the most homologous germline gene K5.1 (Vκ1A, top) or K1A5 (Vκ1C, bottom). Dashes indicate sequence identities, and amino acid substitutions are indicated in bold. These sequence data are available from EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ under accession nos. AF154883–AF154898.

Figure 8.

Nucleotide sequences of Vλ1 genes expressed in SIPC tumors. Nucleotide sequences of subclones (designated A–F) of Vλ genes from SIPC3282, SIPC3336, and SIPC3301 are compared with the most homologous germline gene. Dashes indicate sequence identities, and amino acid substitutions are indicated in bold. These sequence data are available from EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ under accession nos. AF154899–AF154908.

Transcript Levels of Igκ and Igλ in SIPC Tumors.

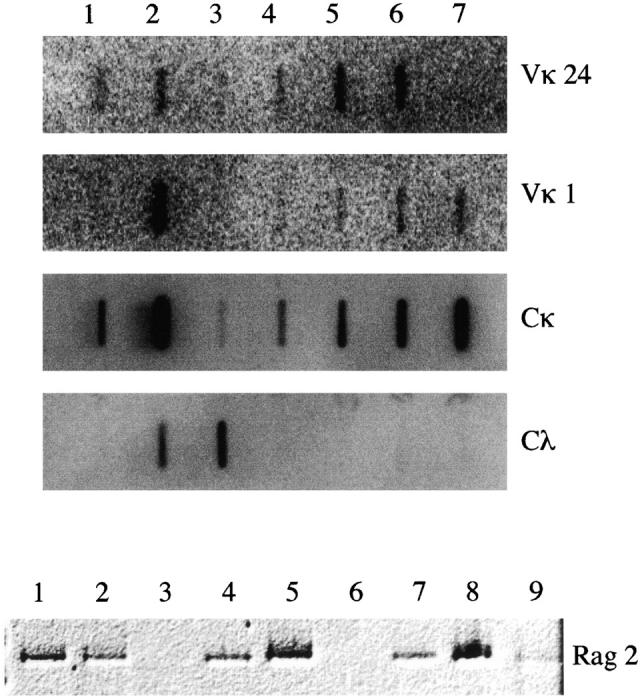

Levels of Igκ and Igλ were compared by slot blot hybridization using specific probes for Vκ1, Vκ24, Vλ, and Cκ (Fig. 9). Interestingly, SIPC3301 expressed high levels of Igλ, whereas SIPC3385 expressed high levels of Vκ1. Consistently, both SIPC3282 and SIPC3336 expressed high levels of both Vκ1 and Vκ24. Since there is evidence that peritoneal cavity B cells are enriched in B-1 cells, we also tested for Ly1 expression by RT-PCR amplification of total RNA from thymus, spleen, two PCs, (ABPC18, MOPC104E) and the SIPC tumors. Although expression of Ly1 was found in thymus, spleen, and the two conventional PCs, no expression of Ly1 was evident in the SIPC tumors (data not shown). RAG-1 (data not shown) and RAG-2 (Fig. 9) activity, both of which have recently been found in the peripheral B-1 population 23, were also independently assayed by RT-PCR amplification among similar panels of RNAs. Both RAG-1 and RAG-2 expression were found in thymus, spleen, SIPC3301, SIPC3308, SIPC3385, ABPC18, and MOPC104E, but not in SIPC3282 or SIPC3336.

Figure 9.

Transcript levels of Igκ, Igλ, and RAG-2 in SIPC tumors. (Top) Equal amounts of RNA from mouse liver (lane 1), spleen (lane 2), SIPC3301 (lane 3), SIPC3308 (lane 4), SIPC3282 (lane 5), SIPC3336 (lane 6), and SIPC3385 (lane 7) were loaded into slots and hybridized to nick-translated probes from Vκ24 (row 1), Vκ1 (row 2), Cκ (row 3), or Vλ (row 4). (Bottom) RNA from mouse spleen (lane 1), thymus (lane 2), SIPC3282 (lane 3), SIPC3301 (lane 4), SIPC3308 (lane 5), SIPC3336 (lane 6), SIPC3385 (lane 7), ABPC18 (lane 8), and MOPC104E (lane 9) was reverse transcribed (RT) and PCR amplified using primers specific for RAG-2.

Discussion

Since spontaneous PCs occur rarely in mice, studies in plasmacytomagenesis rely on induction models. All PCs arise in the peritoneum, where the presence of nonmetabolizable paraffin oils (pristane) or plastic implants induces chronic inflammation, granuloma formation, and finally development of the PC 1. The SIPC may differ by having fewer numbers of atypical foci 8. Binding studies of pristane-induced PCs showed that PCs can display binding activities against phosphorylcholine, various dextrans, and fructofuranans 2. The SIPCs, as we show in this study, possess a set of binding specificities against cytoskeletal proteins and DNA. In fact, in the initial panel of ascites from 33 SIPC tumors, binding activity against at least 1 of the Ags of the panel, and most often polyreactive binding activity, is commonly observed. To ascertain whether the SIPC tumors possess a characteristic set of binding properties and whether these binding specificities could assist in identifying a precursor cell population, we focused on the binding activity of purified proteins from five representative SIPC tumors.

We have found that three independent SIPC tumors, each derived from different generations (SIPC3282, SIPC3308, and SIPC3336), share identical VH domains including DH and JH regions (Table ). Several facts argue strongly in favor of the independent derivation of these tumors: (a) each tumor was harvested at different times as a result of variable latency periods (see Materials and Methods); (b) reactivity patterns differ between each tumor (Table ); (c) SIPC3282 shows an additional rearrangement (JH) not found in other tumors, as well as additional somatic mutations not found in other tumors; (d) SIPC3385 and SIPC3308 both lack Vλ1 rearrangements; and (e) no RAG-1/2 expression is found in SIPC3282 or SIPC3336. These results also support the existence of a strong restriction in V gene usage for the SIPCs. These results are in contrast with reports for human myeloma, where no particular selection for V genes has been observed 24. In contrast, Waldenström macroglobulinemia patients exhibiting rheumatoid or cold agglutinin anti-I specificities exhibit a strong restriction for V genes, as the V1-69 VH1 gene member is almost constantly expressed in the case of cryoglobulins expressing the WA recurrent idiotype (60% of cases), and the V4-34 (VH4-21) gene is constantly expressed by cold agglutinins with anti-I specificity (95% of cases; 25). Although the DH region is not identical among these Abs, a report by Fais et al. 26 shows that among 50% of CLL patients expressing the 1-69 gene, the DH3-3 region is used. In addition, a report from the same group indicated that five different cases of CD5+IgG+ CLLs expressed virtually identical Ag receptors, by recombining (unmutated) the VH-4-39 gene to D6-13-JH5b and the Vκ012 gene to Jκ1 27.

Table 4.

Heavy and Light Chain Gene Usage in SIPC Tumors

| Tumors | Expressed heavy chain | Expressed light chain | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| SIPC3385 | 4m3- | Vκ21G-Jκ2 | Vκ1A-Jκ1 | |

| DSP2- | Vκ1C-Jκ2 | |||

| JH4 | ||||

| SIPC3308 | H13-3- | Vκ24C-Jκ4 | Vκ1A-Jκ1 | |

| DSP2-9- | Vκ1C-Jκ1 | |||

| JH3 | Vκ1C-Jκ2 | |||

| SIPC3301 | 26.4.1.α- | Vκ34C-Jκ2 | Vκ1A-Jκ1 | Vλ1-Cλ1 |

| DSP2-9- | Vκ1A-Jκ4 | |||

| JH3 | ||||

| SIPC3336 | H13-3- | Vκ24C-Jκ4 | Vκ1A-Jκ4 | Vλ1-Cλ1 |

| DSP2-9- | Vκ1C-Jκ2 | |||

| JH3 | Vκ1C-Jκ4 | |||

| SIPC3282 | H13-3- | Vκ24C-Jκ4 | Vκ1A-Jκ2 | Vλ1-Cλ1 |

| DSP2-9- | ||||

| JH3 | ||||

Ig gene assembly is an ordered process that begins with heavy chain gene rearrangement 28 under the regulation of recombinase genes (RAG-1/RAG-2). As the Ig rearrangement process is error prone, only a successful V(D)J assembly leads to pre-B cell receptor assembly 29 30 and eventual downregulation of RAG-1/RAG-2 activity 31. Further differentiated and proliferating B cells reactivate the recombinases to rearrange the light chain genes, which once again are error prone, i.e., wherein only successful rearrangement leads to maturation rather than cell death 29 30. Therefore, allelic exclusion, typically the hallmark of Ig gene expression and of an active process, may also stem more from the low frequency of productive or successful rearrangement. With the elucidation of V gene receptor editing 32 33 34 35 36 37 38, we now know that lymphocytes expressing self-reactivity in the bone marrow, germinal center (GC), or even in the periphery can be rescued from cell death by exchanging already rearranged V regions with other available V genes through reactivation of the RAG-1/RAG-2 recombination pathway 23 38 39 40. It has been shown that recombinase activity is stimulated by low-affinity Abs and is inhibited by high-affinity Abs 41, and accordingly, secondary Ig rearrangements actually occur quite frequently 42 43 44 45. RAG-1/RAG-2 activity is also found in GC B cells bearing low-affinity receptors, or in peripheral B-1 cells 23. Indeed, there is increasing evidence that productive and successful light chain rearrangements do not effectively arrest further rearrangement 46 47 48 49 50 51 52. Thus, one would then expect frequent violations of allelic exclusion in that κ:λ dual expressors 53, as well as dual expressors of Igκ 54 55 subtype, should be quite common.

In this study of SIPC tumors, we have observed only a single productive rearrangement of the light chain genes at the Southern hybridization level for Vκ24C-Jκ4. For SIPC3385 (expressing Vκ21G-Jκ2) and SIPC3301 (expressing Vκ34C-Jκ2), we find rearrangements in both EcoR1 and BamH1 Southern blots that are, in fact, consistent with predicted sizes from germline restriction maps for both Vκ and Jκ gene segments 16 17. We only detected secondarily expressed alleles (κ or λ) by RT-PCR at levels below the Southern detection levels, i.e., subthreshold. We can eliminate contaminating host tissue as contributing to this observation by several lines of argument. (a) A restricted subset (Vκ1 or Vλ1) of V genes are found, rather than simply random usage. Furthermore, since Vλ1 is rarely expressed in the mouse, finding Vλ1 in 3/5 tumors is highly unlikely. (b) We have recently colinked Vκ24 and Vλ1 expression at the single cell level by RT-PCR amplification (our unpublished results). A more likely explanation, therefore, is that we must be observing only a subset of B cells in these tumors expressing both alleles. Thus, the presence of dual expressing κ:λ or κ:κ alleles indicates that secondary rearrangements are occurring in the SIPC tumors, but whether this rearrangement occurs at significant levels to alter the tumor reactivity patterns must be considered further. Interestingly, it is conceivable that the Vκ24C-Jκ4 rearrangement that is shared by three of the tumors may already be an example of secondary rearrangements after a highly selectable process, as secondary rearrangements of the same allele are often characterized by upstream Vκ segments associated with downstream Jκ segments. An alternative explanation, that the observed biallelic expression arises from an outgrowth of a subset of tumor cells, cannot formally be discounted. Indeed, when we compare the reactivities (Table ) of two SIPC tumors (SIPC3308, SIPC3336) that exhibit identical Vκ24C-Jκ4 and V(D)J rearrangements, including amino acid substitutions, we find greater reactivity to ssDNA with SIPC3308. Thus, a perceived difference in reactivity between these tumors may stem from the “subthreshold” levels of Vκ1 or Vλ. These “subthreshold” rearrangements do not necessarily have to occur in the bone marrow or GC, but could occur in the periphery where RAG-1/2 can be reactivated 56. However, as recent studies suggest that RAG-1/2 activity may not actually be reinduced, but may reflect differing levels of B cell development 57, we may be observing a small self-renewing B cell population in the tumors presented here. Interestingly, we find RAG-1/2 still active in most of the SIPCs, with the exception of two tumors (SIPC3336 and SIPC3282), both of which also express IgVλ.

The precursor to PCs has long been thought to be the B-1 cell through two lines of evidence: (a) B-1 cells are most abundant in the peritoneum, and are associated primarily with IgA in the lamina propria 58; and (b) in addition to dextran, phosphorylcholine is one of the more common Ags associated with the gut flora and is dominated by the T15 idiotype 1. It has been shown by X-irradiation and failure to regenerate the T15 idiotype by bone marrow reconstitution 59 60 that the T15 idiotype can only be restored by peritoneal B cells (i.e., B-1 cells). While B-1 cells express Ly1, it is uncertain as to whether Ly1 is activated as a consequence of immortalization, or whether this represents a distinct B cell lineage. We have determined that several pristane-induced PCs (including M104E and ABPC18) express Ly1 by RT-PCR amplification. Conversely, we have found that the SIPC tumors do not express Ly1, but further studies will be needed to rigorously determine whether the SIPCs are truly B-1a, B-1b, or even B-2 cells.

We now show that the SIPC tumors exhibit secondary Ig light chain gene rearrangements (and accompanying RAG-1/2 activity), exhibit low levels of somatic mutation in Vκ or Vλ, and show some evidence of clonal heterogeneity. While B-2 cells are mutated and most frequently found in the GC, the B-1 population is most often found in the mantle zone with few somatic mutations 61. The fact that we find evidence of tumors bearing somatic mutations with intraclonal heterogeneity and with high R/S ratios suggests Ag selection is occurring. V region analysis in several tumor systems besides SIPCs, including Burkitt's lymphoma 62 63, diffuse large cell lymphoma 64, mantle cell lymphoma 65, and follicular lymphomas 64, demonstrates clonal heterogeneity in that somatic mutations appear to be ongoing during the progression of the tumor. Temporally, many of these tumors arise at different stages of lymphoid maturation and in different lymphoid compartments. In contrast, more mature tumors such as multiple myeloma 66 67 and pristane-induced mouse PCs 2 have traditionally been found to exhibit homogeneous Abs, suggesting that these transformed cells must have been immortalized post-GC. Based on these findings, we propose that the SIPC tumors may have become an immortalized B cell population in the periphery.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the continuing support and suggestions of Dr. Michael Potter in the design of these experiments and in critically reviewing the manuscript.

This work was funded in part by a fellowship from the Fogarty Fund.

Footnotes

1used in this paper: CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; ds, double-stranded; g, generation; GC, germinal center; IVS, intervening sequence; NAA, natural polyreactive autoantibody; PC, plasmacytoma; R, replacement; RAG, recombination activating gene; RT, reverse transcription; S, silent; SI, silicone-induced PC; ss, single-stranded

References

- Potter M., Wiener F. Plasmacytomagenesis in micemodel of neoplastic development dependent upon chromosomal translocations. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13:1681–1697. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.10.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter M. Antigen-binding myeloma proteins of mice. Adv. Immunol. 1977;25:141–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilbert B., Dighiero G., Avrameas S. Naturally occurring antibodies against nine common antigens in human sera. I. Detection, isolation and characterization. J. Immunol. 1982;128:2779–2787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dighiero G., Lymberi P., Mazie J.C., Rouyre S., Butler B.G., Whalen R.G., Avrameas S. Murine hybridomas secreting natural monoclonal antibodies reacting with self antigens. J. Immunol. 1983;131:2267–2272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaw L., Magnac C., Pritsch O., Buckle M., Alzari P.M., Dighiero G. Structural and affinity studies of IgM polyreactive natural autoantibodies. J. Immunol. 1997;158:968–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai S.K., Mantovani L., Kasaian M.T., Casali P. Natural autoantibodies. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1994;347:147–159. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2427-4_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dighiero G. Autoimmunity and B-cell malignancies. Hematol. Cell Ther. 1998;40:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter M., Morrison S., Wiener F., Zhang X.K., Miller F.W. Induction of plasmacytomas with silicone gel in genetically susceptible strains of mice. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1058–1065. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.14.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrock E., du Manoir S., Veldman T., Schoell B., Wienberg J., Ferguson-Smith M.A., Ning Y., Ledbetter D.H., Bar-Am I., Soenksen D. Multicolor spectral karyotyping of human chromosomes. Science. 1996;273:494–497. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5274.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaw, L. 1997. Polyreactivite et structure des auto-anticorps naturels murins. Ph.D. thesis. Université de Reims, Reims, France. 207 pp.

- Huppi K., Siwarski D., Skurla R., Klinman D., Mushinski J.F. Pvt-1 transcripts are found in normal tissues and are altered by reciprocal(6;15) translocations in mouse plasmacytomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:6964–6968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.6964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiff C., Milili M., Fougereau M. Functional and pseudogenes are similarly organized and may equally contribute to the extensive antibody diversity of the IgVHII family. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1985;4:1225–1230. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03764.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikder S.K., Akolkar P.N., Kaladas P.M., Morrison S.L., Kabat E.A. Sequences of variable regions of hybridoma antibodies to α(1—6) dextran in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice. J. Immunol. 1985;135:4215–4221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H., Tarlinton D., Muller W., Rajewsky K., Forster I. Most peripheral B cells in mice are ligand selected. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:1357–1371. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caton A.J. A single pre-B cell can give rise to antigenic-specific B cells that utilize distinct immunoglobulin gene rearrangements. J. Exp. Med. 1990;172:815–825. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.3.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich G., Traunecker A., Tonegawa S. Somatic mutation creates diversity in the major group of mouse immunoglobulin κ light chains. J. Exp. Med. 1984;159:417–435. doi: 10.1084/jem.159.2.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiante N.M., Caton A.J. A new Igk-V gene family in the mouse. Immunogenetics. 1990;32:345–350. doi: 10.1007/BF00211649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleclough C., Perry R.P., Karjalainen K., Weigert M. Aberrant rearrangements contribute significantly to the allelic exclusion of immunoglobulin gene expression. Nature. 1981;290:372–378. doi: 10.1038/290372a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan S.P., Max E.E., Seidman J.G., Leder P., Scharff M.D. Two kappa immunoglobulin genes are expressed in the myeloma S107. Cell. 1981;26:57–66. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard O., Gough N.M., Adams J.M. Plasmacytomas with more than one immunoglobulin kappa mRNAimplications for allelic exclusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:5812–5816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.9.5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbet S., Milili M., Fougereau M., Schiff C. Two V kappa germ-line genes related to the GAT idiotypic network (Ab1 and Ab3/Ab1′) account for the major subfamilies of the mouse V kappa-1 variability subgroup. J. Immunol. 1987;138:932–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng K.H., Lavigueur A., Ricard L., Boivrette M., Maclean S., Cloutier D., Gibson D.M. Characterization of allelic V kappa-1 region genes in inbred strains of mice. J. Immunol. 1989;143:638–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X.F., Schwers S., Yu W., Papavasiliou F., Suh H., Nussenzweig A., Rajewsky K., Nussenzweig M.C. Secondary V(D)J recombination in B-1 cells. Nature. 1999;397:355–359. doi: 10.1038/16933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritzman J., Kunkel H.G., McCarthy J., Mellors R.C. Studies of a Waldenström-type macroglobulin with rheumatoid factor properties. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1961;57:905–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman G.J., Schrohenloher R.E., Accavitti M.A., Koopman W.J., Carson D.A. Structural characterization of the second major cross-reactive idiotype group of human rheumatoid factors. Association with the VH4 gene family. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1347–1360. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fais F., Ghiotto F., Hashimoto S., Sellars B., Valetto A., Allen S.L., Schulman P., Vinciguerra V.P., Rai K., Rassenti L.Z. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells express restricted sets of mutated and unmutated antigen receptors. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;102:1515–1525. doi: 10.1172/JCI3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valetto A., Ghiotto F., Fais F., Hashimoto S., Allen S.L., Lichtman S.M., Schulman P., Vinciguerra V.P., Messmer B.T., Thaler D.S. A subset of IgG+ B-CLL cells expresses virtually identical antigens receptors that bind similar peptides. Evidence for antigen-selection in the leukemogenic process Blood. 92 1998. 431(Abstr.)a [Google Scholar]

- Tonegawa S. Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature. 1983;302:575–581. doi: 10.1038/302575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchers F., Rolink A., Grawunder U., Winkler T.H., Karasuyama H., Ghia P., Andersson J. Positive and negative selection events during B lymphopoiesis. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1995;7:214–227. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows P.D., Cooper M.D. B cell development and differentiation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1997;9:239–244. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grawunder U., Leu T.M., Schatz D.G., Werner A., Rolink A.G., Melchers F., Winkler T.H. Down-regulation of RAG1 and RAG2 gene expression in preB cells after functional immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement. Immunity. 1995;3:601–608. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanopoulou E., Roman C.A., Corcoran L.M., Schlissel M.S., Silver D.P., Nemazee D., Nussenzweig M.C., Shinton S.A., Hardy R.R., Baltimore D. Functional immunoglobulin transgenes guide ordered B-cell differentiation in Rag-1-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1030–1042. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young F., Ardman B., Shinkai Y., Lansford R., Blackwell T.K., Mendelsohn M., Rolink A., Melchers F., Alt F.W. Influence of immunoglobulin heavy- and light-chain expression on B-cell differentiation. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1043–1057. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiegs S.L., Russell D.M., Nemazee D. Receptor editing in self-reacting bone marrow B cells. J. Exp. Med. 1993;177:1009–1020. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radic M.Z., Erikson J., Litwin S.L., Weigert M. B lymphocytes may escape tolerance by revising their antigen receptors. J. Exp. Med. 1993;177:1165–1173. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay D., Saunders T., Camper S., Weigert M. Receptor editingan approach by autoreactive B cells to escape tolerance. J. Exp. Med. 1993;177:999–1008. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Radic M.Z., Erikson J., Camper S.A., Litwin S., Hardy R.R., Weigert M. Deletion and editing of B cells that express antibodies to DNA. J. Immunol. 1994;152:1970–1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Nagy Z., Prak E.L., Weigert M. Immunoglobulin heavy chain gene replacementa mechanism of receptor editing. Immunity. 1995;3:747–755. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikida M., Mori M., Takai T., Tomochika K., Hamatani K., Ohmori H. Reexpression of RAG-1 and RAG-2 genes in activated mature mouse B cells. Science. 1996;274:2092–2094. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S., Dillon S.R., Zheng B., Shimoda M., Schlissel M.S., Kelsoe G. V(D)J recombinase activity in a subset of germinal center B lymphocytes. Science. 1997;278:301–305. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz M., Kouskoff V., Nakamura T., Nemazee D. V(D)J recombinase induction in splenic B lymphocytes is inhibited by antigen-receptor signalling. Nature. 1998;394:292–295. doi: 10.1038/28419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S., Rosenberg N., Alt F., Baltimore D. Continuing kappa-gene rearrangement in a cell line transformed by Abelson murine leukemia virus. Cell. 1982;30:807–816. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ness B.G., Coleclough C., Perry R.P., Weigert M. DNA between variable and joining gene segments of immunoglobulin κ light chain is frequently retained in cells that rearrange the κ locus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1982;79:262–266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.2.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feddersen R.M., Van Ness B.G. Double recombination of a single immunoglobulin κ-chain alleleimplications for the mechanism of rearrangement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:4793–4797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.14.4793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro M.A., Weigert M. How immunoglobulin V kappa genes rearrange. J. Immunol. 1987;139:3834–3839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S., McCray S. A shared kappa reciprocal fragment and a high frequency of secondary Jk5 rearrangements among influenza hemagglutinin specific B cell hybridomas. J. Immunol. 1991;146:343–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada K., Yamagishi H. Lack of feedback inhibition of V κ gene rearrangement by productively rearranged alleles. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:409–415. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.2.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy R.R., Dangl J.L., Hayakawa K., Jager G., Herzenberg L.A., Herzenberg L.A. Frequent lambda light chain gene rearrangement and expression in a Ly-1 B lymphoma with a productive kappa chain allele. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:1438–1442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.5.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollahon K.A., Hagman J., Brinster R.L., Storb U. Ig lambda-producing B cells do not show feedback inhibition of gene rearrangement. J. Immunol. 1988;141:2771–2780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S., Campbell M.J., Levy R. Functional immunoglobulin light chain genes are replaced by ongoing rearrangements of germline V κ genes to downstream J κ segment in a murine B cell line. J. Exp. Med. 1989;170:1–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber C., Klobeck H.G., Zachau H.G. Ongoing V kappa-J kappa recombination after formation of a productive V kappa-J kappa coding joint. Eur. J. Immunol. 1992;22:1561–1565. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma A., Fisher P., Dildrop R., Oltz E., Rathbun G., Achacoso P., Stall A., Alt F.W. Surface IgM mediated regulation of RAG gene expression in E mu-N-myc B cell lines. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1992;11:2727–2734. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doglio L., Kim J.Y., Bozek G., Storb U. Expression of lambda and kappa genes can occur in all B cells and is initiated around the same pre-B-cell developmental stage. Dev. Immunol. 1994;4:13–26. doi: 10.1155/1994/87352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prak E.L., Trounstine M., Huszar D., Weigert M. Light chain editing in κ-deficient animalsa potential mechanism of B cell tolerance. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:1805–1815. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prak E.L., Weigert M. Light chain replacementa new model for antibody gene rearrangement. J. Exp. Med. 1995;182:541–548. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachino C., Padovan E., Lanzavecchia A. κ1λ1 dual receptor B cells are present in the human peripheral repertoire. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:1245–1250. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W., Nagaoka H., Jankovic M., Misulovin Z., Suh H., Rolink A., Melchers F., Meffre E., Nussenzweig M. Continued RAG expression in late stages of B cell development and no apparent reinduction after immunization. Nature. 1999;400:682–687. doi: 10.1038/23287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroese F.G.M., Cebra J.J., Van der Cammen M.J.F., Kantor A.B., Bos N.A. Contribution of B-1 cells to intestinal IgA production in the mouse. Methods. 1995;8:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa K., Hardy R.R., Stall A.M., Herzenberg L. Immunoglobulin-bearing B cells reconstitute and maintain the murine Ly-1 B cell lineage. Eur. J. Immunol. 1986;16:1313–1316. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830161021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster I., Rajewsky K. Expansion and functional activity of Ly-1+ B cells upon transfer of peritoneal cells into allotype-congenic, newborn mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 1987;17:521–528. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830170414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzenberg L.A., Kantor A.B. B-cell lineages exist in the mouse. Immunol. Today. 1993;14:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90063-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman C.J., Mockridge C.I., Rowe M., Rickinson A.B., Stevenson F.K. Analysis of VH genes used by neoplastic B cells in endemic Burkitt's lymphoma shows somatic hypermutation and intraclonal heterogeneity. Blood. 1995;85:2176–2181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R., Roncella S., Hashimoto S., Carbone A., P. Francia di Celle, R. Foa, M. Ferrarini, and N. Chiorazzi A potential role for antigen selection in the clonal evolution of Burkitt's lymphoma. J. Immunol. 1994;153:45–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottensmeier C.H., Thompsett A.R., Zhu D., Wilkins B.S., Sweetenham J.W., Stevenson F.K. Analysis of VH genes in follicular and diffuse lymphoma shows ongoing somatic mutation and multiple isotype transcripts in early disease with changes during disease progression. Blood. 1998;91:4292–4299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittaluga S., Tierens A., Pinyol M., Campo E., Delabie J., De Wolf-Peeters C. Blastic variant of mantle cell lymphoma shows a heterogenous pattern of somatic mutations of the rearranged immunoglobulin heavy chain variable genes. Br. J. Haematol. 1998;102:1301–1306. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkus M.H., Van Riet I., Van Camp B., Thielemans K. Evidence that the clonogenic cell in multiple myeloma originates from a pre-switched but somatically mutated B cell. Br. J. Haematol. 1994;87:68–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb04872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahota S., Hamblin T., Oscier D.G., Stevenson F.K. Assessment of the role of clonogenic B lymphocytes in the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 1994;8:1285–1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]