Abstract

To analyze the implication of PTEN in the control of tumor cell invasiveness, the canine kidney epithelial cell lines MDCKras-f and MDCKts-src, expressing activated Ras and a temperature-sensitive v-Src tyrosine kinase, respectively, were transfected with PTEN expression vectors. Likewise, the human PTEN-defective glioblastoma cell lines U87MG and U373MG, the melanoma cell line FM-45, and the prostate carcinoma cell line PC-3 were transfected. We demonstrate that ectopic expression of wild-type PTEN in MDCKts-src cells, but not expression of PTEN mutants deficient in either the lipid or both the lipid and protein phosphatase activities, reverted the morphological transformation, induced cell–cell aggregation, and suppressed the invasive phenotype in an E-cadherin–dependent manner. In contrast, overexpression of wild-type PTEN did not counteract Ras-induced invasiveness of MDCKras-f cells expressing low levels of E-cadherin. PTEN effects were not associated with marked changes in accumulation or phosphorylation levels of E-cadherin and associated catenins. Wild-type, but not mutant, PTEN also reverted the invasive phenotype of U87MG, U373MG, PC-3, and FM-45 cells. Interestingly, PTEN effects were mimicked by N-cadherin–neutralizing antibody in the glioblastoma cell lines. Our data confirm the differential activities of E- and N-cadherin on invasiveness and suggest that the lipid phosphatase activity of PTEN exerts a critical role in stabilizing junctional complexes and restraining invasiveness.

Keywords: PTEN; invasiveness; E-cadherin; Src; PI3 kinase

Introduction

Neoplastic progression results from the dysregulation of a series of proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. In this context, the recently discovered PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted from chromosome 10) tumor suppressor gene has been found to be defective in a large number of human cancers, including glioblastomas, endometrial, prostate, and renal cancers, as well as melanomas (Cantley and Neel, 1999). The hallmark of malignancy is the acquisition of the invasive phenotype. This process involves breakdown of cell–cell junctions, increased motility of tumor cells, and focal proteolysis of the extracellular matrix. Among junctional complexes, the E-cadherin–catenin system exerts a critical role in the control of carcinogenesis. These complexes are subjected to inactivation by multiple mechanisms, including both genetic and epigenetic events. Accordingly, activation of the Src tyrosine kinase switches E-cadherin junctions from a strong to a weak state and induces the invasive phenotype in epithelial canine kidney MDCKts-src cells, transformed by a temperature-sensitive v-Src tyrosine kinase (pp60v-src) (Behrens et al., 1989, 1993; Takeda et al., 1995).

Several lines of evidence suggest that PTEN might participate in regulating cell–cell junctions and tumor cell invasion. The amino terminus of PTEN shows homology with tensin, a protein interacting with actin at focal adhesions, and its carboxy terminus encodes a potential PDZ binding motif. Proteins with PDZ domains, such as ZO-1, direct the assembly of multiprotein complexes, often at membrane–cytoskeletal interfaces. Furthermore, characterization of PTEN activity revealed that it is a phosphatase that acts on both phosphotyrosine residues and the D3 position of phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate, the product of phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase (PI3-kinase)* (Furnari et al., 1998; Myers et al., 1998). The PTEN mutations so far identified affect either the phosphatidylinositol phosphatase, or both phosphatidylinositol and protein phosphatase activities. We have previously demonstrated an involvement of the PI3-kinase signaling pathway in inducing the invasive phenotype of MDCKts-src cells (Kotelevets et al., 1998). It has also been reported that PTEN selectively dephosphorylates focal adhesion kinase, and it inhibits the motility of fibroblasts and the invasiveness of U87MG glioma cells (Tamura et al., 1998, 1999).

To delineate the involvement of PTEN in the control of tumor cell scattering and invasiveness, and to investigate the cross-talk between PTEN and the Ras and Src oncogenic pathways on the one hand, and cadherin junctional complexes on the other, we transfected MDCKras-f and MDCKts-src cells and several human, PTEN-defective tumor cell lines with vectors expressing either wild-type PTEN or PTEN mutants deficient in either the phosphoinositide phosphatase or both the protein and phosphoinositide phosphatase activities. We evaluated morphological conversion, invasion into type I collagen, cell aggregation, and the expression, composition, phosphorylation level, and subcellular localization of cadherin-containing junctional complexes.

Results and discussion

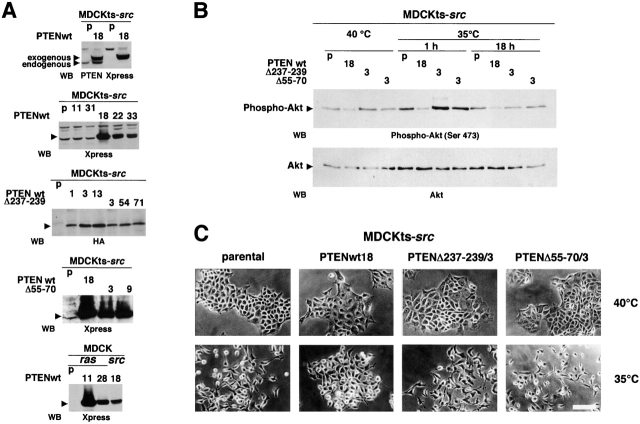

PTEN reverses the morphological conversion induced by pp60v-src

To investigate the cross-talk between the PTEN and the Src and Ras oncogenic pathways, we expressed wild-type PTEN and lipid phosphatase– or phosphatase-deficient PTEN mutants in MDCK cells, transformed by either a temperature-sensitive mutant of v-Src (MDCKts-src cells) (Behrens et al., 1989, 1993; Takeda et al., 1995) or v-Ras (MDCKras-f) (Vleminckx et al., 1991). It was previously demonstrated that PTEN mutation Δ237–239 results in a 10-fold decrease in phosphatase activity toward phosphatidylinositol (1,3,4,5)P4 without affecting protein phosphatase activity, whereas PTEN mutations Δ55–70 and C124A affect both the lipid and protein phosphatase activities of PTEN (Furnari et al., 1998; Tamura et al., 1998). PTEN expression in transformants was assessed by immunoblotting using anti-tag antibodies (anti-Xpress or anti-HA) as well as anti-PTEN antibody (Fig. 1 A). In MDCKts-src cells, PTEN overexpression affected neither the phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase nor the MAPK and PI3-kinase activities (unpublished data). In contrast, the ectopic expression of wild-type PTEN, but not PTEN mutants, reduced the phosphorylation of Akt, a downstream target of PI3-kinase, as shown in Fig. 1 B and in line with previous reports for other cell lines (Myers et al., 1998).

Figure 1.

Effect of functional transfer of wild-type or mutant PTEN expression vectors on the morphology of MDCKts-src. (A) Analysis of PTEN expression. The ectopic expression of wild-type and PTEN mutants deficient in either the lipid phosphatase activity (PTENΔ237–239) or both the protein and lipid phosphatase activities (PTEN Δ55–70) was assessed by Western blot using antibodies directed against PTEN, or against the Xpress or HA epitopes. Cell lines are indicated as parental (p) or as transfected clone numbers. (B) Analysis of Akt activity. Akt phosphorylation, which is a measurement of Akt activity, was analyzed with anti–phospho-Akt(Ser 473) antibody in cell lysates from parental MDCKts-src cells (p) and their derivatives transfected with either wild-type (clone 18) or mutant PTEN. Growth was either at the nonpermissive temperature for Src activity (40°C) or after transfer to 35°C for 1 or 18 h as indicated. The total amount of Akt was assessed using anti-Akt antibody. (C) Morphology of parental MDCKts-src cells and their derivatives transfected with either wild-type or mutant PTEN. MDCKts-src cells exhibited an epithelial morphology at 40°C and a fibroblast-like morphology when grown for 14 h at the permissive temperature for Src activity (35°C). Neither lipid phosphatase–deficient (PTENΔ237–239) nor the phosphatase-inactive (PTEN Δ55–70) PTEN mutants preserved the epithelial morphology at the permissive temperature as the wild-type PTEN did. Bar, 20 μm.

The possible cross-talk between PTEN and Src signaling pathways was first assessed at the morphological level. At the nonpermissive temperature for Src activity (40°C), both parental MDCKts-src and MDCKts-srcPTENwt cells grew as small clusters of adherent cells with few membrane ruffles or lamellipodia. Switching the MDCKts-src cells to the permissive temperature induced a fibroblast-like morphotype. The first effects were apparent 4 to 6 h after the temperature shift, as cells formed prominent lamellipodia and began to acquire the fibroblastic morphotype. 14 h after the shift, colonies of cells were almost completely dissociated (Fig. 1 C). Similar results were obtained in MDCKts-srcPTENΔ237–239 expressing the lipid phosphatase–deficient PTEN mutant, as well as the MDCKts-srcPTENΔ55–70 expressing inactive PTEN (Fig. 1 C). In contrast, after a 14-h incubation at 35°C, MDCKts-srcPTENwt retained a polygonal epithelioid morphotype, and cell clusters remained largely intact. In addition, wild-type PTEN delayed the scattering of MDCKts-srcPTENwt cells as compared with the parental cell line in wound healing assays (unpublished data).

Inhibition of pp60v-src-induced invasiveness by wild-type PTEN

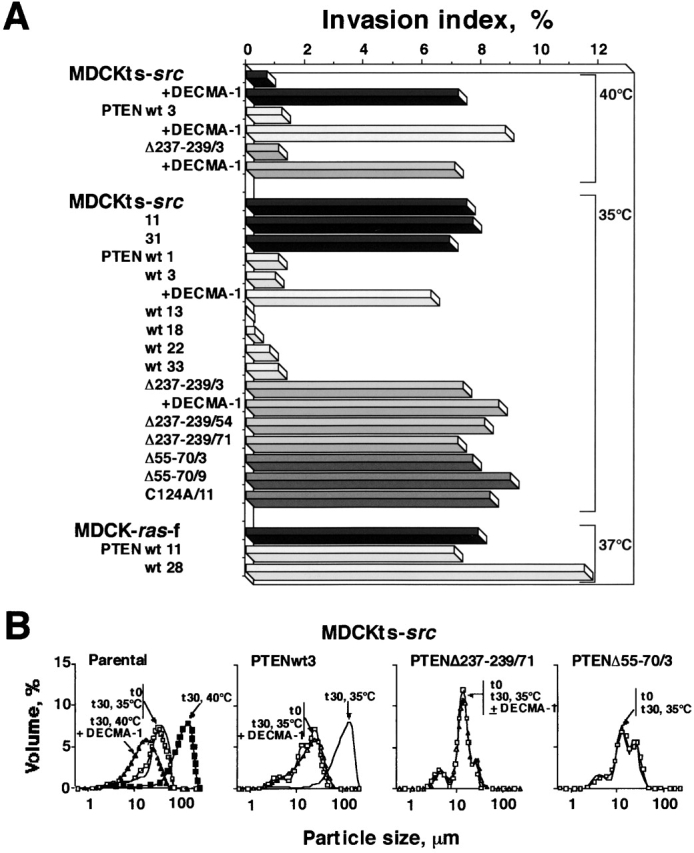

Because PTEN interfered with Src-induced cell scattering, we further investigated the invasive properties of parental and PTEN-transfected MDCKts-src cells in type I collagen gels. As shown in Fig. 2 A, the parental MDCKts-src cells and those derivatives that did not express exogenous PTEN, MDCKts-src11 and MDCKts-src31, became invasive after a temperature shift to 35°C. In contrast, the six MDCKts-srcPTENwt clones that overexpressed wild-type PTEN remained noninvasive at the permissive temperature (Fig. 2 A). Overexpression of PTEN mutants in MDCKts-src cells did not revert the invasive phenotype induced by Src at 35°C, demonstrating the critical role of the PTEN lipid phosphatase activity in the control of the invasive phenotype. Besides the lipid phosphatase activity of PTEN, invasion suppression clearly involved the E-cadherin system, as inactivation of E-cadherin by DECMA-1 mAb induced the invasive phenotype in MDCKts-srcPTENwt, both at the restrictive and the permissive temperature for Src activity (Fig. 2 A). Likewise, PTEN could not counteract the invasive phenotype of MDCKras-f cells that poorly expressed E-cadherins (Vleminckx et al., 1991).

Figure 2.

Effects of PTEN expression on the invasive phenotype and cell aggregation of the MDCKts-src and MDCKras-f cell lines. (A) Invasion of type I collagen. MDCKts-src, MDCKras-f cells, and their derivatives transfected by wild-type or mutant PTEN were seeded on type I collagen gel at the restrictive or permissive temperature for Src activity (MDCKts-src) or at 37°C (MDCKras-f cells), and the number and depth of cells inside the gel were measured after 24 h. The dependence of this process on E-cadherin function was assessed by the inactivation of E-cadherin with DECMA-1 mAb. (B) Fast aggregation assay. The activity of junctional complexes in MDCKts-src cells and their derivatives was assessed by the distribution of the size of cell aggregates evaluated at t 0 (□) or after a 30-min incubation (t 30). Aggregation of parental cells for 30 min at 40°C yielded curves corresponding to particles with large size (left panel, ▪). The same was observed for PTEN (wild-type or mutant) transfectants at 40°C (unpublished data). Src activation at 35°C impaired aggregation of the parental MDCKts-src cells and derivatives expressing mutant PTEN (PTEN Δ237–239/71, PTEN Δ55–70/3, and unpublished data) yielding curves coinciding with the t 0 curves (similar results were obtained with the MDCKts-srcΔ55–70 /9 and MDCKts-srcC124A/11 cells; unpublished data). In contrast, aggregation of MDCKts-srcPTENwt3 cells for 30 min at 35°C yielded a curve corresponding to large cell aggregates, which can be superimposed on the one measured at 40°C (unpublished data). Treatment with mAb DECMA-1 against E-cadherin at the restrictive (▴) or the permissive (▵) temperature for Src activity abolished aggregation in all cell types.

Stabilization of E-cadherin junctional complexes by PTEN

To gain further insight into the mechanisms involved in the PTEN-mediated reversion of Src-induced cell scattering and invasiveness, we used the fast aggregation assay to test whether PTEN activity affects the E-cadherin–dependent adhesion system. A prominent feature of suspended parental MDCKts-src cells is the inability to aggregate at the permissive temperature, whereas cell aggregates form readily in an E-cadherin–dependent manner at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 2 B, left). In contrast, wild-type PTEN but not mutant PTEN transfectants (Δ237–239/71, Δ55–70/3, and C124A/11) formed aggregates at the permissive temperature for Src activity (35°C). All aggregations observed here were impaired by the E-cadherin neutralizing antibody DECMA-1 (Fig. 2 B). These results confirmed the critical role of the lipid phosphatase activity of PTEN in stabilizing E-cadherin junctions and reverting cell scattering and invasiveness.

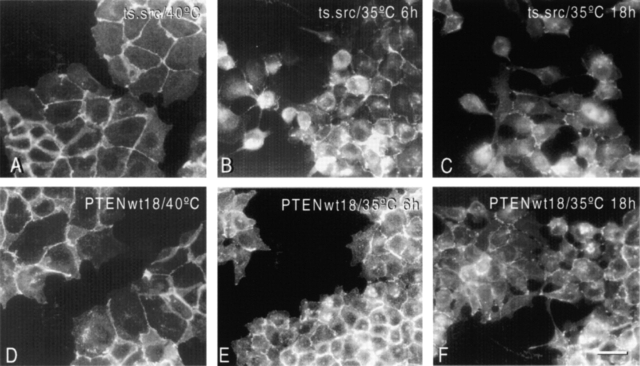

Effect of PTEN on E-cadherin–catenin complexes

We next compared the expression, phosphorylation level, and cellular localization of E-cadherin and associated proteins in MDCKts-src and MDCKts-srcPTENwt cells before and after a shift to the permissive temperature for Src activity. At the restrictive temperature, the E-cadherin signal was concentrated at cell–cell contacts (Fig. 3 A). Time-course studies showed that Src activation in MDCKts-src cells resulted in progressive reduction of junctional complexes, delocalization of E-cadherin from the cell surface, and loss of epithelioid morphotype (Fig. 3, B and C). In contrast, MDCKts-srcPTENwt cells preserved cell–cell junctions and E-cadherin localization for longer times (Fig. 3, D–F). The same was observed for α-catenin, β-catenin, and p120ctn (unpublished data).

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescent staining of E-cadherin in parental MDCKts-src cells and their wild-type PTEN transfectants grown at 40°C or after switch to 35°C. E-cadherin is concentrated at cell–cell contacts at the nonpermissive temperature for Src activity. Note that it is more diffusely distributed over the surface of dissociated MDCKts-src cells at the permissive temperature but largely concentrated at sites of cell–cell contacts in MDCKts-srcPTENwt18 cells. Bar, 10 μm.

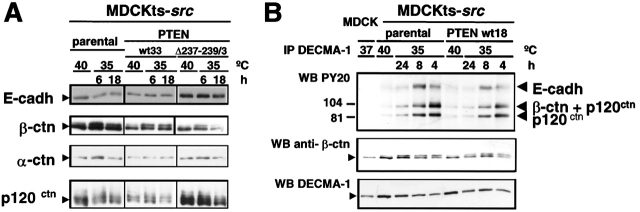

Because E-cadherin activity crucially depends on its association with several cytoplasmic proteins, we analyzed the total amount of E-cadherin, and associated α-catenin, β-catenin, and p120ctn. We found that any of these expression levels were similar at both nonpermissive and permissive temperatures and also not significantly altered by PTEN expression (Fig. 4 A). In addition, Src-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of E-cadherin and associated catenins was comparable in MDCKts-src cells and their PTEN derivatives (Fig. 4 B). Thus, in the presence of wild-type PTEN, Src-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of E-cadherin junctional complexes is not sufficient to promote the disruption of adherens junctions.

Figure 4.

Effects of wild-type or mutant PTEN expression on the accumulation and phosphorylation levels of E-cadherin and associated proteins in MDCKts-src cells and derivatives. (A) Western blotting of E-cadherin, α-catenin, β-catenin, and p120ctn in total cell lysates at permissive and nonpermissive temperature for Src activity. (B) Cell lysates from MDCK, MDCKts-src, and their derivatives grown at 37°C, 40°C, or 35°C were immunoprecipitated with the E-cadherin–specific mAb DECMA-1. The tyrosine phosphorylated components of cadherin–catenin complexes were revealed using the PY20 mAb and the ECL system.

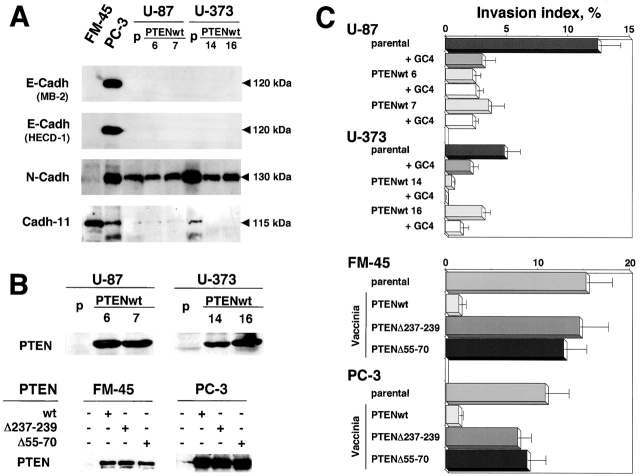

Reversion of invasiveness of PTEN-defective human cell lines after restoration of PTEN expression

To further extend the effects of PTEN on the stabilization of junctional complexes and the reversion of the invasive phenotype, we restored PTEN expression in human cell lines known to be PTEN defective: glioblastoma cell lines U87MG and U373MG, melanoma cell line FM-45, and prostate carcinoma cell line PC-3 (Guldberg et al., 1997; Tamura et al., 1998; Whang et al., 1998). We first analyzed the expression patterns of epithelial E-cadherin, mesenchymal N-cadherin, and cadherin-11 (Fig. 5 A). All three cadherins were found to be expressed in PC-3 cells, which are known to be defective in Ca2+-dependent cell aggregation due to αE-catenin defects (Morton et al., 1993). In contrast, the U87MG and U373MG glioblastoma cells expressed mainly N-cadherin, and FM-45 melanoma cells were featured by weak expression of N-cadherin and major expression of cadherin-11. A small amount of the latter cadherin was also identified in U373MG cells. In agreement with the results obtained from MDCKts-src cells, wild-type PTEN reverted the invasive phenotype of U87MG and U373MG glioblastoma cells stably transfected by wild-type PTEN, and of FM-45 melanoma and PC-3 prostate carcinoma cells transiently transfected using vaccinia virus–mediated PTEN expression (Fig. 5, B and C). In the latter two cell lines, overexpression of mutant PTEN molecules did not revert the invasive phenotype (Fig. 5 C). These results confirm the critical role of the lipid phosphatase activity of PTEN in regulating invasiveness. Moreover, the invasive phenotype of the U87MG and U373MG glioblastoma cell lines was clearly dependent on N-cadherin activity, because it was inhibited after application of the N-cadherin blocking antibody GC-4 (Fig. 5 C), whereas it was noneffective on FM-45 cells that express mainly cadherin-11 (Fig. 5 A, and unpublished data). Nonetheless, PTEN-mediated invasion suppression was not associated with any significant change in the expression pattern of cadherins (Fig. 5 A, and unpublished data).

Figure 5.

Effect of restoration of PTEN expression on the invasive phenotype of the PTEN-defective human melanoma cell line FM-45, the prostate carci-noma cell line PC-3, and the glioblastoma cell lines U87MG and U373MG. (A) Immunoblot analysis of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and cadherin-11. Cell lysates (50 μg protein for all cell lines except for U87MGwt14 and U373MGwt16 lysates for which 30 μg was used) were immunoblotted with mAbs directed against E-cadherin (MB-2 and HECD-1), N-cadherin (Zymed), or cadherin-11 (113H), and probed using the ECL system. (B) Analysis of PTEN expression in U87MG and U373MG cells and their derivatives stably transfected by wild-type PTEN, and in FM-45 and PC-3 cell lines transiently expressing wild-type or mutant GFP–PTEN upon vaccinia infection. Cell lysates (100 μg protein) from parental and PTEN-transfected cells were immunoblotted with mAbs directed against PTEN. (C) Invasion of type I collagen by U87, U373, FM-45, and PC-3 cells and their derivatives transfected by wild-type or mutant PTEN. Cells were seeded on type I collagen gels at 37°C and the number and depth of cells inside the gel were measured after 24 h. The dependence of cell migration and invasion on N-cadherin was assessed by the blocking of N-cadherin using GC-4 antibodies (dilution 1:50).

Several studies have demonstrated that the switch in expression from E-cadherin to either N-cadherin or cadherin-11, as observed regularly in melanoma and prostate cancer cells, might promote cell motility (Tomita et al., 2000; Li et al., 2001). Whereas E-cadherin mediates tight cell–cell adhesion, the mesenchymal N-cadherin and cadherin-11 exert a dual activity on both cell–cell interactions and cell motility and invasiveness. N-cadherin and cadherin-11 might also exert a dominant effect over E-cadherin, as demonstrated in breast cancer cells after ectopic expression of N-cadherin (Nieman et al., 1999; Hazan et al., 2000). Because the N-cadherin–mediated survival and cell motility of melanoma cell lines seem to involve the PI3 kinase pathway (Li et al., 2001), PTEN might function as a potent gate keeper to counteract invasiveness mediated by mesenchymal cadherins. In consequence, PTEN inactivation during tumor progression might favor tumor cell dissemination.

Altogether, our data demonstrate that PTEN constitutes a critical effector in controlling the invasive phenotype. Because PTEN inactivation occurs in a wide range of tumors, we propose that PTEN can regulate the noninvasive phenotype via both E-cadherin–dependent and –independent pathways, according to the cellular context: (a) stabilization of E-cadherin complexes; (b) reversion of the activity and effector systems of mesenchymal cadherins; and (c) modulation of cell–matrix adhesion complexes through integrin and cytoskeleton reorganization. Development of therapeutic strategies targeting the many effector systems controlled by PTEN may not only suppress tumor growth and induce apoptosis, but holds also the promise to restrain tumor cell dissemination and metastasis.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction and cell transfection

Full-length wild-type PTEN cDNA and phosphatase inactive PTEN mutant Δ55–70 were generated by RT-PCR of RNA extracted from human colonic crypts and the invasive glioblastoma cell line 149, respectively. The resulting PCR products were subcloned into pcDNA-His (Invitrogen), in frame with the NH2-terminal Xpress epitope. Expression vectors encoding wild-type PTEN or the phosphophatidylinositol phosphatase inactive PTEN mutant Δ237–239 fused with the HA epitope (Furnari et al., 1998) were provided by Dr. F.B. Furnari (University of California, San Diego, CA). Expression vectors encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP)–tagged wild-type PTEN or phosphatase inactive PTEN mutant C124A (Tamura et al., 1998) were provided by Dr. K.M. Yamada (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

The MDCKts-src clone 2 and MDCKras-f cell lines expressing, respectively, thermosensitive v-Src and activated Ras, have been previously established by infection of MDCK cells with either a murine leukemia retroviral construct recombined with a thermosensitive v-src gene or the Harvey murine sarcoma virus (Behrens et al., 1989, 1993; Vleminckx et al., 1991; Takeda et al., 1995). MDCKts-src clone 2 and MDCKras-f cells, and the U87 and U373 glioblastoma cell lines were transfected with PTEN expression vectors, using lipofectamine (GIBCO BRL) as previously described (Kotelevets et al., 1998). The PTEN C124A construct that lacks a selection marker was cotransfected with pcDNA3.1 plasmid (Invitrogen), conferring G418 resistance. After selection for 2 wk with 500 μg/ml G418 (Xpress-tagged constructs, PTENC124A) or 4 μg/ml puromycin (HA-tagged constructs), colonies of growing, surviving cells were randomly picked up, amplified, and evaluated for expression of the transgene by Western blotting.

For vaccinia virus–mediated transient overexpression, wild-type and mutant (Δ237–239 and Δ55–70) PTEN cDNAs were subcloned in the pE/L-GFP vector, in frame with the GFP tag (Frischknecht et al., 1999). FM-45 and PC-3 cells were transfected with Lipofectin (Life Technologies) and simultaneously coinfected with vaccinia virus strain ΔA36R, which does not make actin tails. 10 h after transfection, PTEN cDNAs, under the control of the vaccinia virus early/late promoter, were expressed at high levels. The pE/L-GFP vector and vaccinia virus strain ΔA36R were provided by Dr. F. Frischknecht (European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Heidelberg, Germany) and B. Janssens (VIB-Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium).

Collagen type I invasion and fast aggregation assays

Single-cell suspensions were seeded on top of the type I collagen gel (Upstate Biotechnology), and cultures were incubated for 24 h at 35°C, 37°C, or 40°C. Using an inverted microscope controlled by a computer program (Vakaet et al., 1991), we counted the invasive and superficial cells in 12 fields of 0.157 mm2. The invasion index was expressed as the percentage of cells invading the gel over the total number of cells (Vleminckx et al., 1991).

For the fast aggregation assay, single-cell suspensions were prepared using an E-cadherin saving procedure (Bracke et al., 1993). Cells were incubated in an isotonic buffer containing 1.25 mM Ca2+ under Gyrotory shaking for 30 min at either 35°C or 40°C. Particle diameters were measured in a particle size counter (LS 200; Beckman Coulter) at the start (t 0) and after a 30-min incubation (t 30), and plotted against percentage volume distribution.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in PBS with Ca2+ and Mg2+, containing 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM Pefablock SC (Merck), 1 mM leupeptin, 0.3 mM aprotinin, 200 μM sodium orthovanadate, and 50 mM NaF. The lysates were cleared and adjusted to equal protein amounts. E-cadherin and associated proteins in the lysates were immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies and protein G–Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Immunoprecipitates and whole-cell extracts were separated on 8% polyacrylamide gels and blotted to PVDF membranes (Millipore). The mouse mAbs directed against p120ctn, β-catenin, and P-Tyr (PY20) were purchased from Transduction Laboratories. Rabbit pAb against αE-catenin, rat mAb DECMA-1 against E-cadherin, and N-cadherin blocking mAb GC-4 were from Sigma-Aldrich. Mouse mAb against N-cadherin was from Zymed Laboratories, mouse mAb HECD-1 against E-cadherin was from Takara Biochemicals, and mouse mAb 113H against cadherin-11 was provided by ICOS Corporation. The mAb MB2 against E-cadherin was created as previously described by Bracke et al. (1993).

For detection of exogenous PTEN expression, we used anti-HA mAbs (Eurogentec), anti-Xpress rabbit pAb, and anti-PTEN mAb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Anti-Akt and anti-phospho-Akt (ser 473) antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technologies. Signals were visualized with Ig coupled to HRP, using the ECL system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Monolayers prepared for fluorescent staining were grown on glass coverslips. Cells were rinsed briefly with PBS and fixed with ice cold methanol for 15 min at –20°C. Immunostaining was performed as previously described (van Hengel et al., 1997). The secondary antibodies used in immunofluorescence microscopy were AlexaTM488-coupled Ig antibodies (Molecular Probes). Samples were examined with a Zeiss Axiophot photomicroscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc.).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. F. Furnari and Dr. K. Yamada for providing PTEN expression vectors, and Dr. F. Frischknecht and B. Janssens for providing pE/L-GFP vector and vaccinia virus strain ΔA36R.

This work was supported by the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer, the Fund for Scientific Research (FWO), the Geconcerteerde Onderzoeksacties of Ghent University, the Sportvereniging tegen Kanker, and FORTIS Bank/Insurances. L. Kotelevets was a recipient of an EMBO fellowship. J. van Hengel is a postdoctoral fellow with the FWO.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: GFP, green fluorescent protein; PI3-kinase, phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase.

References

- Behrens, J., M.M. Mareel, F.M. van Roy, and W. Birchmeier. 1989. Dissecting tumor cell invasion: epithelial cells acquire invasive properties after the loss of uvomorulin-mediated cell–cell adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 108:2435–2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens, J., L. Vakaet, R. Friis, E. Winterhager, F. van Roy, M.M. Mareel, and W. Birchmeier. 1993. Loss of epithelial differentiation and gain of invasiveness correlates with tyrosine phosphorylation of the E-cadherin/β-catenin complex in cells transformed with a temperature-sensitive v-src gene. J. Cell Biol. 120:757–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracke, M.E., B.M. Vyncke, E.A. Bruyneel, S.J. Vermeulen, G.K. De Bruyne, N.A. Van Larebeke, K. Vleminckx, F.M. Van Roy, and M.M. Mareel. 1993. Insulin-like growth factor I activates the invasion suppressor function of E-cadherin in MCF-7 human mammary carcinoma cells in vitro. Br. J. Cancer. 68:282–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantley, L.C., and B.G. Neel. 1999. New insights into tumor suppression: PTEN suppresses tumor formation by restraining the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:4240–4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischknecht, F., V. Moreau, S. Rottger, S. Gonfloni, I. Reckmann, G. Superti-Furga, and M. Way. 1999. Actin-based motility of vaccinia virus mimics receptor tyrosine kinase signalling. Nature. 401:926–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnari, F.B., H.J.S. Huang, and W.K. Cavenee. 1998. The phosphoinositol phosphatase activity of PTEN mediates a serum-sensitive G1 growth arrest in glioma cells. Cancer Res. 58:5002–5008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guldberg, P., P.T. Straten, A. Birck, V. Ahrenkiel, A.F. Kirkin, and J. Zeuthen. 1997. Disruption of the MMAC1/PTEN gene by deletion or mutation is a frequent event in malignant melanoma. Cancer Res. 57:3660–3663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan, R.B., G.R. Phillips, R.F. Qiao, L. Norton, and S.A. Aaronson. 2000. Exogenous expression of N-cadherin in breast cancer cells induces cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. J. Cell Biol. 148:779–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotelevets, L., V. Noë, E. Bruyneel, E. Myssiakine, E. Chastre, M. Mareel, and C. Gespach. 1998. Inhibition by platelet-activating factor of Src- and hepatocyte growth factor-dependent invasiveness of intestinal and kidney epithelial cells. Phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase is a critical mediator of tumor invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 273:14138–14145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, G., K. Satyamoorthy, and M. Herlyn. 2001. N-cadherin-mediated intercellular interactions promote survival and migration of melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 61:3819–3825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton, R.A., C.M. Ewing, A.Nagafuchi, S. Tsukita, and W.B. Isaacs. 1993. Reduction of E-cadherin levels and deletion of the alpha-catenin gene in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 53:3585–3590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers, M.P., I. Pass, I.H. Batty, J. Van Der Kaay, J.P. Stolarov, B.A. Hemmings, B.A. Wigler, M.H. Wigler, C.P. Downes, and N.K. Tonks. 1998. The lipid phosphatase activity of PTEN is critical for its tumor suppressor function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:13513–13518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieman, M.T., R.S. Prudoff, K.R. Johnson, and M.J. Wheelock. 1999. N-cadherin promotes motility in human breast cancer cells regardless of their E-cadherin expression. J. Cell Biol. 147:631–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, H., A. Nagafuchi, S. Yonemura, S. Tsukita, J. Behrens, and W. Birchmeier. 1995. v-Src kinase shifts the cadherin-based cell adhesion from the strong to the weak state and beta catenin is not required for the shift. J. Cell Biol. 131:1839–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, M., J.G. Gu, K. Matsumoto, S. Aota, R. Parsons, and K.M. Yamada. 1998. Inhibition of cell migration, spreading, and focal adhesions by tumor suppressor PTEN. Science. 280:1614–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, M., J.G. Gu, T. Takino, and K.M. Yamada. 1999. Tumor suppressor PTEN inhibition of cell invasion, migration, and growth: differential involvement of focal adhesion kinase and p130(Cas). Cancer Res. 59:442–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita, K., A. van Bokhoven, G. van Leenders, E.T.G. Ruijter, C.F.J. Jansen, M.J.G. Bussemakers, and J.A. Schalken. 2000. Cadherin switching in human prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 60:3650–3654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakaet, L., Jr., K. Vleminckx, F. Van Roy, and M. Maeel. 1991. Numerical evaluation of the invasion of closely related cell lines into collagen type I gels. Invasion Metastasis. 11:249–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hengel, J., L. Gohon, E. Bruyneel, S. Vermeulen, M. Cornelissen, M. Mareel, and F. van Roy. 1997. Protein kinase C activation upregulates intercellular adhesion of α-catenin–negative human colon cancer cell variants via induction of desmosomes. J. Cell Biol. 137:1103–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vleminckx, K., L. Vakaet, Jr., M. Mareel, W. Fiers, and F. van Roy. 1991. Genetic manipulation of E-cadherin expression by epithelial tumor cells reveals an invasion suppressor role. Cell. 66:107–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whang, Y.E., X. Wu, H. Suzuki, R.E. Reiter, C. Tran, R.L. Vessella, J.W. Said, W.B. Isaacs, and C.L. Sawyers. 1998. Inactivation of the tumor suppressor PTEN/MMAC1 in advanced human prostate cancer through loss of expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:5246–5250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]