Abstract

Math6 is a tissue-restricted member of the Atonal family of bHLH transcription factors and has been implicated in specification and differentiation of cell lineages in the brain. We identify here Math6 as a podocyte expressed bHLH protein that was downregulated in HIV-associated nephropathy; a collapsing glomerulopathy characterized by podocyte dedifferentiation. Early in metanephric development, Math6 was expressed in metanephric mesenchyme, but not ureteric bud-derived cells, with overall Math6 expression most abundant in the nephrogenic zone, including developing glomeruli. In adult kidney, Math6 expression was restricted to podocytes. In adult podocyte cell lines and kidneys from the transgenic mouse model of HIVAN, Math6 podocyte expression was reduced concurrent with previously reported reductions in Nephrin and Synaptopodin expression, suggesting a correlation between the loss of Math6 expression and typical podocyte terminal differentiation markers. These studies suggest that Math6 may participate in kidney development, and may be a permissive factor for podocyte differentiation.

Keywords: podocyte, HIV-associated nephropathy, HIV-1, transcriptional regulation grant support: NIH DK61395

INTRODUCTION

The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins are a class of transcription factors well known to participate in cell fate specification and differentiation events. There are 102 mouse and 125 human bHLH proteins either known or predicted from genome analyses, however, relatively few of these bHLH proteins have been shown to participate in kidney development (Ledent et al., 2002). To date these have included; Pod1/Capsulin/Epicardin (Miyagishi et al., 2000; Quaggin et al., 1998), the Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF) family (Falahatpisheh and Ramos, 2003; Freeburg et al., 2003), and the transcriptional repressor Id proteins (Duncan et al., 1994). In addition, a few other bHLH proteins, npas3 (Brunskill et al., 1999), myf5, myf6/Herculin (Imabayashi et al., 2001), Nulp1 (Olsson et al., 2002), and repressors Hes1 and Hes5 (Chen and al Awqati, 2005; Piscione et al., 2004) have been shown to be expressed by renal cells, although their functions have not been investigated in detail. During development, bHLH proteins regulate the expression of genes required for commitment and differentiation, and function either transcriptional activators or transcriptional repressors (Bergstrom and Tapscott, 2001; Kageyama et al., 2005). It is this balance between the bHLH repressors and bHLH activators that cue cells through their commitment and differentiation program. In addition, it appears that bHLH proteins alone are not sufficient, but act in concert with other homeodomain factors that together coordinate the expression of unique gene sets that ultimately specify the location, number, and maturation of highly specialized cell types (Westerman et al., 2003).

We have recently identified several additional bHLH proteins expressed by podocytes, the highly specialized visceral epithelial cell of the kidney glomerulus primarily responsible for synthesizing the major components of the filtration barrier. One of these, Math6, was downregulated in a differential expression screen comparing normal mouse podocytes with podocytes derived from a transgenic model of HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN). Math6 is a tissue-restricted bHLH protein first described by Kageyama and colleagues as a transcription factor with a necessary and non-redundant role in establishing neuronal versus glial cell types (Inoue et al., 2001). In this study, Math6 is expressed in both undifferentiated, neural precursor cells and in subsets of mature neurons, and is involved in both the differentiation and the maintenance of these mature neuronal cell types. It is not yet known if Math6 is a transcriptional activator or a transcriptional repressor.

We describe here the expression pattern for Math6 during kidney development and in the setting of a chronic glomerular disease, HIVAN. The glomerular lesion in HIVAN is a collapsing glomerulopathy, and various groups have extensively characterized the “dysregulated podocyte phenotype” (Barisoni et al., 1999) in both rodent models and human biopsies. These well documented phenotypic changes in podocytes include increased proliferation, increased apoptosis and loss of terminal differentiation (reviewed in Barisoni and Mundel, 2003). The transformation of HIVAN podocytes to a more proliferative and de-differentiated phenotype would suggest that the cells have lost a regulatory program that maintains the normal adult podocyte in its typically quiescent and terminally-differentiated state. Thus, Math6, a transcription factor known to be required for the maturation and homeostasis of highly specialized neuronal cell types, may be similarly required for the maintenance of the highly specialized kidney podocyte since its downregulation was associated with cellular dedifferentiation induced by disease.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of Math6 expression in podocytes

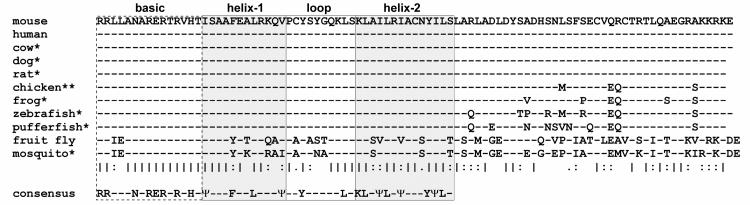

An expression analysis comparing normal and HIV-1 expressing mouse podocyte cell lines produced a collection of cDNA fragments representing both down-regulated and up-regulated genes induced by HIV-1 infection. The methodology and other results of this screen have been previously reported (Ross et al., 2003). One of the identified cDNAs was a novel gene containing a bHLH region that was down-regulated by HIV-1. Several full length clones of this bHLH gene were isolated from a normal mouse podocyte cDNA library and were sequenced on both strands by primer walking. Standard nucleotide translations and homology searches with public database information indicated this was a newly described bHLH protein in the Atonal superfamily, designated Math6 (Ledent et al., 2002). Human (Hath6) and Drosophila (atoh8/Net) orthologs of this protein have been described (Brentrup et al., 2000; Wasserman et al., 2002), and several other orthologs have been identified through genome analysis. All vertebrate Math6 proteins have 100% amino acid identity through the bHLH region and very high sequence conservation through the remaining carboxy terminus (Figure 1). Overall, all mammalian orthologs share a full protein sequence conservation of >84%, as well as 100% identity in the first 50 amino terminal residues (not shown).

Fig. 1.

Sequence alignment of the carboxy terminus of Math6 orthologs. The domains of the bHLH region are shown in the shaded boxes. Standard single letter amino acid abbreviations are used; (|) fully conserved residue, (:) conservation of strong groups, (.) conservation of weak groups. The bHLH region consensus is shown below (Υ, hydrophobic residue). *Predicted protein, **Predicted protein and EST.

Math6 expression pattern

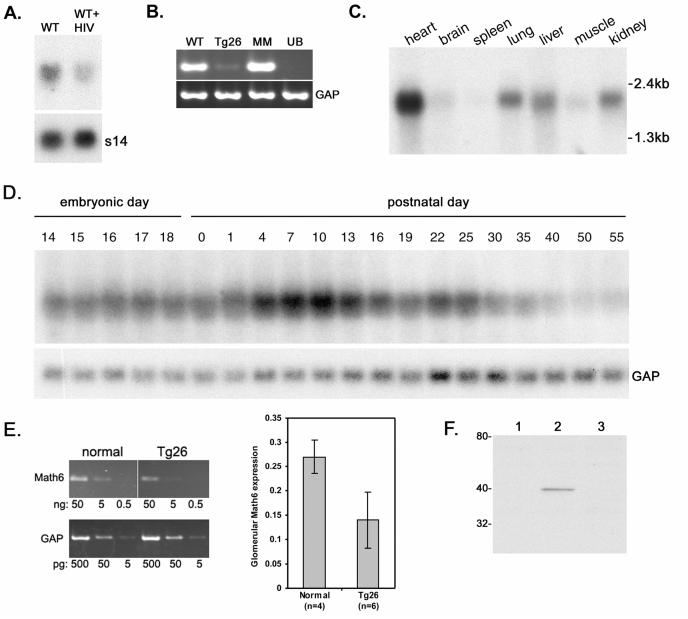

Math6 was strongly downregulated in both de novo HIV-1 infection of normal podocytes (WT+HIV, Figure 2A), and also in podocytes derived from the HIV-1 transgenic mouse model (Tg26, Figure 2B). As described above, these observations are consistent with the results of the expression analysis that originally identified Math6 in podocytes. The glomerular lesion in HIVAN is characterized by podocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation (Barisoni et al., 1999). Although the precise mechanisms underlying the HIV-induced podocyte dysregulation remain to be clarified, it has been shown that alterations in podocyte gene expression are caused, in part, by alterations in the activity of key transcription factors (Martinka and Bruggeman, 2005; Ross et al., 2003). Thus, Math6 appears to be another podocyte-expressed transcription factor that is altered in HIVAN, and will likely impact mature podocyte homeostasis through the function of downstream Math6 target genes.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of Math6 mRNA and protein expression. A. Northern analysis of altered Math6 expression between normal mouse (wild type, WT) podocytes and normal podocytes infected with a virus (WT+HIV) containing the HIV-1 proviral construct used to make the transgenic mouse model (ribosomal s14 as control). B. Math6 RT/PCR using RNA isolated from normal mouse podocytes (WT); podocytes from the HIV-1 transgenic mouse model (Tg26); E11.5 mouse metanephric mesenchyme (MM) cell line; and E11.5 mouse ureteric bud (UB) cell line. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAP) as control. C. Multi-tissue Northern blot from adult mouse demonstrating the restricted distribution and variable expression level in different adult tissues. D. Expression of Math6 during kidney development. Mouse total kidney RNA was harvested at various days during embryonic and post-natal development (GAP expression is used as a control). E. Semi-quantitative RT/PCR of Math6 expression in glomeruli isolated from normal and HIV-1 transgenic (Tg26) mouse kidneys. Example of a single animal comparison is shown at left using serial dilutions of input template. Quantification of replicas (mean±SD; normal n=4, and Tg26 n=6) is shown in graph at right and was statistical significant (P=0.014). F. Characterization of Math6 antibody by Western blotting. Lane 1, HEK293T cells. Lane 2, HEK293T cells transfected with a Math6 expression plasmid. Lane 3, HEK293T cells transfected with a Math6 expression plasmid of the cDNA cloned in the reverse orientation.

Since many bHLH proteins have an important role during development, we examined the expression of Math6 in the developing mouse kidney. By RT/PCR, Math6 was expressed in metanephric mesenchyme (MM) but not ureteric bud (UB) cell lines derived from mouse E11.5 metanephroi (Figure 2B), suggesting an early expression of Math6 in the metanephric blastema, but not in cells derived from the ureteric bud. By Northern analysis, Math6 was expressed in a variety of adult tissues including a low level of expression in adult kidney (Figure 2C). More abundant expression occurred in adult heart, liver and lung, with lower expression in skeletal muscle and also in brain as previously observed by Inoue et al. (Inoue et al., 2001). Throughout kidney development (Figure 2D) the total kidney expression level of Math6 was dynamic. In the early stages of in utero development (E14.5 to E18.5) to birth (postnatal day 0), Math6 remained relatively constant to the total amount of kidney RNA. After birth, expression increased in whole kidney RNA at days 7 through 10. It is not clear why expression peaked at this time. It may reflect only a change in the number of cells expressing Math6 relative to total kidney tissue, as the mRNA in situ hybridization patterns at day 7 looked similar to day 0 (Figure 4E). By day 13, corresponding to the end of new nephron induction which occurs at approximately 2 weeks of age in the mouse (Bard, 2003), expression levels began to decline. By day 19, Math6 expression returned to fetal levels, and by day 40 the low level of expression that persisted into adulthood was established. The low level of expression in adult was restricted to podocytes (see below). Since podocytes represent a very small cellular fraction of the adult kidney, this decline in total kidney Math6 RNA likely represented a loss of Math6 expression in the blastemal cells of the nephrogenic zone as nephron induction concludes (Figure 4E). The low level that persisted into adulthood represented the expression that was maintained only in the podocyte, which appeared low on a total kidney Northern blot only due to the low number of podocytes relative to the total cell mass of the mature kidney.

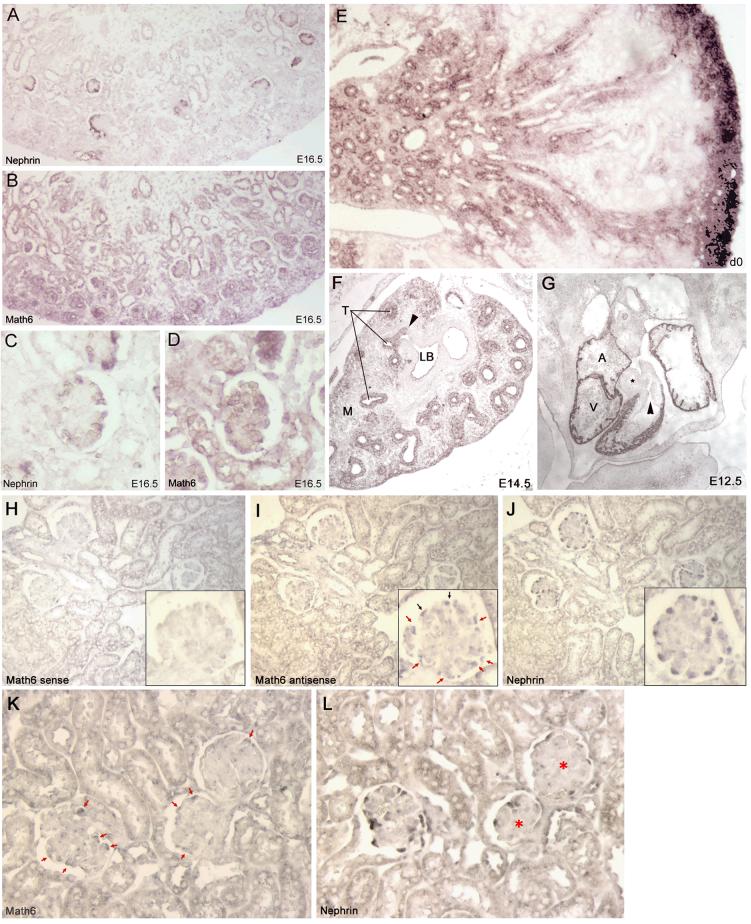

Fig. 4.

In situ expression pattern of Math6 during mouse development and in a mouse model of glomerulosclerosis. A-E. Nonradioactive mRNA in situ hybridization of developing mouse kidneys. All studies included control hybridizations with the respective sense riboprobes which resulted in no staining (not shown). A. Low power view of E16.5 mouse kidney hybridized with an antisense probe for Nephrin to localize developing podocytes. B. Serial section to A, hybridized with an antisense probe to Math6. C-D. Higher power views from panels A and B respectively of a capillary loop stage glomerulus. E. Math6 expression in a newborn (d0) mouse kidney showing abundant staining in the nephrogenic zone. F. Math6 expression in E14.5 lung; arrow denotes transition between respiratory tubules/bronchioles (T) and a lobar bronchus (LB); mesenchyme (M). G. Math6 expression in E12.5 heart; asterisk denotes aorta, arrow indicates outflow tract to pulmonary artery; atrium (A); ventricle (V). H-J. Nonradioactive mRNA in situ hybridization in serial sections of a normal adult mouse kidney; insets are enlargements of the same glomerulus in each respective serial section. H. Hybridization with a Math6 sense probe (as negative control). I. Hybridization with a Math6 antisense probe; arrows indicate Math6 positive cells that co-localize with Nephrin positive cells in panel J. J. Hybridization with a Nephrin antisense probe to identify podocytes. K-L. Nonradioactive mRNA in situ hybridization in serial sections of HIV-1 transgenic mouse kidneys. K. Hybridization with a Math6 antisense probe; arrows indicate Math6 positive cells. L. Hybridization with a Nephrin antisense probe to identify podocytes; asterisk indicate more severely sclerotic glomeruli with fewer Nephrin positive cells.

This difference in Math6 expression between normal and the HIV-1 transgenics was confirmed and quantified in vivo using RT/PCR from isolated glomeruli. An example of an individual comparison of an age-matched normal and a transgenic mouse pair is shown in Figure 2E. All transgenic animals were four to five months of age with +2 to +3 proteinuria, representing a moderate level of disease progression (endstage animals with +4 proteinuria typically have mostly acellular, fully sclerosed glomeruli). Math6 expression was significantly (P=0.014) reduced in transgenic glomeruli compared to normal by approximately two fold. This reduction was less than what was observed in the cultured cell lines, possibly reflecting some in vivo variability in the severity of sclerosis and Math6 downregulation since HIVAN is a progressive, focal and segmental disease processes and not all glomeruli may be equally affected even within an individual animal.

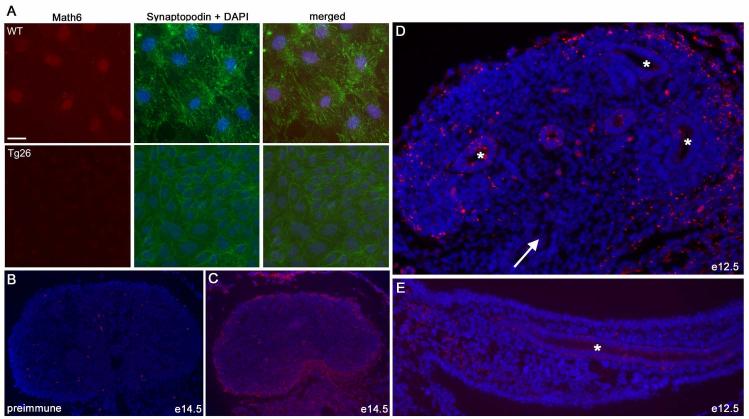

For further characterization of the Math6 protein, polyclonal antibodies were prepared in rabbits and affinity purified. Figure 2F shows a representative Western blot of Math6 protein in HEK293T cells transfected with a Math6 expression plasmid (lane 2), detecting a unique protein band at the predicted molecular weight (38.5kDa). The human cell line HEK293T does not natively express Hath6 (the human ortholog of Math6) as determined by RT/PCR (data not shown). Therefore, Western blotting following the transfection with a Math6 (the murine ortholog) expression plasmid will not be compounded by simultaneous expression of both endogenous and transfected proteins, since there is no endogenous protein produced by HEK293T cells. In immunofluorescence analysis of cultured podocytes (Fig. 3A), staining was observed in the nucleus, a typical location for a bHLH transcription factor. The staining for Math6 was qualitatively greater in normal (“WT”) podocytes compared to podocytes derived from the HIV-1 transgenic mouse model (“Tg26”), as the expression in Tg26 cells was not above background. Synaptopodin expression in the Tg26 cells was also qualitatively reduced and disorganized into circumferential stress fibers, as has been previously reported for these cells (Schwartz et al., 2001). The Tg26 podocytes are also smaller, do not spread as broadly as normal podocytes, and are not contact inhibited (Schwartz et al., 2001).

Fig. 3.

Immunolocalization of Math6 expression in cultured podocytes and fetal mouse kidneys. A. Immunofluorescence for Math6 in normal (WT) and HIV-1 transgenic (Tg26) mouse podocytes (matched exposures). Additional staining included DAPI as a DNA/nuclear dye and Synaptopodin as a podocyte-specific maturation marker. Bar is 20μm. B-D. Immunolocalization of Math6 expression (red) in fetal mouse kidneys; sections were also stained with DAPI (blue) to visualize nuclei. B. Preimmune serum staining in an e14.5 normal mouse kidney as a control. C. Math6 expression (red) in e14.5 mouse kidney, with staining present in the outermost nephrogenic zone. D. Math6 expression (red) in e12.5 mouse kidney, ureteric bud (arrow) and initial branches (*) were negative. E. Math6 expression in mesonephros/urogenital ridge, mesonephric duct (*) was negative.

Early in nephrogenesis (E12.5), Math6 expression did not occur in the mesonephric duct, metanephric duct, or ureteric bud derived cells (Fig. 3B-E). Expression at E14.5 could be observed in the outmost regions of the developing metanephros, with no expression evident in ureteric bud derived cells in vivo.

To better establish which cells in the kidney expressed Math6, mRNA in situ hybridization using a Math6 antisense riboprobe were performed on developing normal mouse kidneys (Fig. 4A-E). The riboprobe used was derived from the 3’ untranslated region of Math6 to eliminate potential cross hybridization with other bHLH containing genes. As a reference gene for podocytes, serial sections were hybridized with an antisense riboprobe for Nephrin. In these studies, Math6 was expressed in metanephric mesenchyme-derived cells including developing glomerular and tubular structures, with the most intense staining associated with the least differentiated cell types at the outermost nephrogenic zone. In capillary loop stage glomeruli (Fig. 4C,D), the expression of Nephrin co-localized with Math6 in serial sections. Although Math6 expression was not as restricted as compared to Nephrin at this time, it does indicate expression in podocyte precursors as well as other glomerular cell types. At birth (d0, Fig. 4E), the expression of Math6 was very intense in the outermost nephrogenic zone and also present at lower levels in some tubule segments of papilla (a region undergoing remodeling of the collecting system a this time), but absent in much of the maturing cortex. The results of the in situ hybridizations and the immunohistochemistry studies are consistent and indicate that Math6 expression was most abundant through development in the metanephric mesenchyme derived cell populations and highest in the least differentiated cell types of the outmost nephrogenic zone.

Math6 was expressed in other developing organs which were also associated with high levels of expression in adult tissues. Fetal lung (Fig 4F) expression was most evident in the single layer epithelium of the branching respiratory tubular epithelia, with a lower level of expression in the more distal mesenchymal regions. Expression, however, was not observed in the epithelium of the main lobar bronchi at this stage of development, suggesting an association of Math6 expression with nascent branching tubular structures. In fetal heart (Fig. 4G), Math6 expression was abundant in trabeculations of the developing cardiac muscle layer but not in the developing aorta or pulmonary artery suggesting a likely restricted expression to cardiomyocytes. This may indicate that Math6 could be another bHLH protein associated with myogenesis (Berkes and Tapscott, 2005).

Association with a chronic glomerular disease

In normal adult mouse kidney, Math6 was expressed, but at a much lower level than in fetal kidney (Figure 4H-L), consistent with Northern blotting results on whole kidney RNA (Figure 2D). Adult kidney Math6 expression occurred in glomerular podocytes (Fig. 4H-J) as determined by co-localization in serial sections with Nephrin, a gene expressed only in podocytes in the kidney. No specific staining could be identified in tubules. Also, there was no evidence of peritubular or glomerular microvascular endothelial cell staining in our studies, which was previously reported for Hath6 expression in a nonhuman primate kidney (Wasserman et al., 2002). In this report, an adult monkey glomerulus was shown to be positive for Hath6 by mRNA in situ hybridization, but the expressing cell type was not established, nor was the riboprobe used for the studies described in sufficient detail to rule out cross hybridization with other bHLH proteins. Alternatively, this possibly could reflect a difference in expression pattern between mice and nonhuman primates.

In HIV-1 transgenic mouse kidneys, podocyte Math6 expression was reduced and detected in a fewer number of podocytes in those glomeruli with evidence of pathological changes such as sclerosis, as seen by the loss of patent capillary loops (Fig. 4 K-L). Podocyte expression of Nephrin was also reduced in these same injured glomeruli, which has been previously described as a typical finding in collapsing glomerulopathy (Barisoni et al., 1999; Barisoni et al., 2000). In HIVAN, there is not a loss of podocytes in diseased glomeruli, but a proliferation of podocytes in which their characteristic differentiation markers such as Nephrin is much reduced or absent (Barisoni et al., 1999). Thus, this observed loss of Nephrin would not suggest a loss of podocytes by cell death, but a dedifferentiation that downregulated the expression of Nephrin. In our study, downregulation of Math6 expression was concurrent with the loss of Nephrin expression in the same injured glomeruli, confirming in vivo that Math6 is a gene downregulated in the dysregulated podocyte phenotype of HIVAN. Whether the loss of Math6 expression caused the podocyte dedifferentiation or is only a co-phenomenon is currently under investigation.

In summary, Math6 was expressed early in nephrogenesis in the metanephric mesenchyme; through nephron induction and the establishment of podocyte and tubular precursors, and finally in the fully differentiated podocyte. This is similar to the previous descriptions of Math6 in neuronal development, in which Math6 expression appears to be broadly expressed during early development, and then becomes restricted to specific cell types in adulthood. It is possible that Math6 may have several roles during nephrogenesis, including an early role specifying the competent metanephric mesenchyme, and a later role as a permissive factor for the differentiation and maturation of the podocyte. The loss of Math6 in HIVAN would affect this later role, resulting in podocyte dedifferentiation. These different roles are probably distinguished by the combined activity of Math6 with other bHLH and homeobox transcription factors that are temporally expressed with Math6 in the metanephric mesenchyme and differentiating podocytes (Quaggin et al., 1999). Our studies would suggest that Math6 may be a transcriptional activator that is a permissive factor for terminal podocyte differentiation, and may be involved, either directly or indirectly, in the regulation of podocyte-restricted genes such as Nephrin. Understanding the role of Math6 in podocyte differentiation may help determine the cause of pathogenic responses by the podocyte in response to injury such as HIV-1 infection.

METHODS

Animal model, cell lines and transfections

The creation of the HIV-1 transgenic mouse model (Tg26), and the description of the kidney disease and podocyte dedifferentiation phenotype have been published (Barisoni et al., 2000; Dickie et al., 1991; Kopp et al., 1992). The normal mouse and Tg26 podocyte cell lines, and the HIV-1 infection of normal podocytes have been previously described (Ross et al., 2003; Schwartz et al., 2001). Podocytes were propagated under permissive conditions and used after culture for 10 days at nonpermissive conditions as described (Mundel et al., 1997b). Conditionally immortalized mouse ureteric bud (UB) and metanephric mesenchyme (m46) cell lines, both derived from E11.5 Immortomouse metanephroi, were obtained from Jonathan Barasch (Columbia University, New York) and Gregory Dressler (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor) respectively and propagated as described (Brophy et al., 2003; Sakurai et al., 1997). HEK293T cells (ATCC# CRL-1573) were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as recommended by the manufacturer. The full length Math6 cDNA was subcloned in both sense and antisense orientations into pCDNA3.1 (Invitrogen) for eukaryotic expression.

Cloning and sequencing

A PCR-generated Math6 cDNA fragment, originally obtained in a differential expression analysis comparing normal and HIV-1 expressing podocytes, was used to screen a mouse podocyte cDNA library to obtain full length clones. The podocyte library construction as well as the original expression analysis methodology has been previously published (Ross et al., 2003). Full length clones were sequenced on both strands by primer walking, and the complete cDNA sequence can be found under GenBank accession number AY349615. Nucleotide sequence manipulations and translations were performed with Vector NTI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and amino acid sequence comparisons used ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994).

mRNA expression analysis

Total cellular RNA was prepared from cells and tissues using TriReagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) with 10μg resolved on 1% agarose formaldehyde gels followed by transferred to nylon membranes. Radioactively labeled cDNA probes from the full length clone was generated by random priming and hybridized overnight at 42°C in Hybrisol I (Serologicals Corporation, Norcross, GA). Stringent washes were at 60°C in 1X SSC, 0.05% SDS. The multi-tissue Northern blot was purchased from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA) and contained 2μg polyA+ RNA of each tissue and was hybridized as above. For PCR, cDNA was synthesized by MMLV reverse transcription (RT) using oligodT priming (Advantage RT-for-PCR, Clontech) from 1μg of total cellular RNA pre-treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega, Madison, WI). One tenth of each RT reactions was used for PCR amplification with primers specific for the Math6 3’ untranslated region (forward: GTCTTCCTCAAGATGCTGCC and reverse: GCAATGATGTGGTTTTGTGC), and with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAP) primers purchased from Clontech. Recommended conditions for hot start PCR using Platinum Taq (Invitrogen) were used with an annealing temperature of 50°C for 30 cycles. Amplicons were resolved on 2% agarose gels. Standard controls of no RT cDNA synthesis reactions and no template PCR reactions were performed for all studies and were negative.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was performed with serial dilutions of input template to determine the linear range of amplification. Band intensities were quantified using Image Quant (Molecular Dynamics) and data means (±SD) were analyzed by t test. For these studies, glomeruli from individual animals were enriched using the standard sieving technique, collecting glomeruli on a 45μm mesh screen (Schlondorff, 1990).

The mRNA in situ hybridizations were performed as previously described (Bruggeman et al., 2000). Sense and antisense riboprobes, corresponding to 300bp of the 3’ untranslated region (generated using the above PCR primers), were synthesized with digoxigenin-labeled dUTP using T7 polymerase and appropriately linearized plasmid. Hybridization conditions were as previously described and slides were washed at maximum stringency of 54°C in 0.2XSSC, followed by immunodetection of the digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes and color development with NBT/BCIP (Roche Diagnostic, Indianapolis, IN). As a podocyte expressed reference gene, a plasmid containing a mouse Nephrin coding fragment (provide by Susan Quaggin, Toronto, Canada) was similarly used to generate sense and antisense riboprobes.

Antibody production, Western blotting and immunohistochemistry

Polyclonal antisera were generated in rabbits (ResGen, Huntsville, AL) using a GST fusion protein with the amino terminus of Math6, followed by affinity chromatography purification using a His-tagged Math6 amino terminus peptide. The amino terminal region was selected for antibody generation because this region was not of significant homology with other known proteins; did not include the bHLH motif; and was of 100% amino acid identity between the human and mouse proteins. The GST fusion protein was made by cloning into the EcoRI/XhoI sites of pGEX-5X-1 (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) a PCR product that was amplified with primers that contained an EcoRI site on the forward primer and an XhoI site on the reverse primer. The His-tagged fusion protein was made by cloning in to the NdeI/BamHI sites of pET15b (Novagen, Madison, WI) a similarly amplified product with the respective restriction sites included in the forward and reverse primers. Both were confirmed by sequencing prior to expression. Procedures for bacterial expression, purification of recombinant proteins, and affinity purification procedures have been previously described (Ross et al., 2003).

Western blotting was performed as described with a 1:300 dilution of Math6 antibody (Ross et al., 2005). Immunohistochemistry was performed with cells grown on collagencoated coverslips as previously described (Mundel et al., 1997a) using a 1:50 dilution of Math6 antibody. A mouse monoclonal antibody for Synaptopodin (Maine Biotechnology Services, Portland, ME) was used undiluted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Jeffrey Simske for helpful comments and discussion. We thank Drs. Florence Rothenberg and George Minowada for assistance with fetal heart and lung anatomy respectively.

REFERENCES

- Barisoni L, Bruggeman LA, Mundel P, D′Agati VD, Klotman PE. HIV-1 induces renal epithelial dedifferentiation in a transgenic model of HIV-associated nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2000;58:173–181. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barisoni L, Kriz W, Mundel P, D′Agati V. The dysregulated podocyte phenotype: a novel concept in the pathogenesis of collapsing idiopathic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:51–61. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barisoni L, Mundel P. Podocyte biology and the emerging understanding of podocyte diseases. Am J Nephrol. 2003;23:353–360. doi: 10.1159/000072917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom DA, Tapscott SJ. Molecular distinction between specification and differentiation in the myogenic basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor family. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2404–2412. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.7.2404-2412.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkes CA, Tapscott SJ. MyoD and the transcriptional control of myogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:585–595. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brentrup D, Lerch H, Jackle H, Noll M. Regulation of Drosophila wing vein patterning: net encodes a bHLH protein repressing rhomboid and is repressed by rhomboid-dependent Egfr signalling. Development. 2000;127:4729–4741. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.21.4729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy PD, Lang KM, Dressler GR. The secreted frizzled related protein 2 (SFRP2) gene is a target of the Pax2 transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52401–52405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305614200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruggeman LA, Ross MD, Tanji N, Cara A, Dikman S, Gordon RE, Burns GC, D′Agati VD, Winston JA, Klotman ME, Klotman PE. Renal epithelium is a previously unrecognized site of HIV-1 infection. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:2079–2087. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V11112079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunskill EW, Witte DP, Shreiner AB, Potter SS. Characterization of npas3, a novel basic helix-loop-helix PAS gene expressed in the developing mouse nervous system. Mech Dev. 1999;88:237–241. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L al Awqati Q. Segmental expression of Notch and Hairy genes in nephrogenesis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F939–F952. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00369.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickie P, Felser J, Eckhaus M, Bryant J, Silver J, Marinos N, Notkins AL. HIV-associated nephropathy in transgenic mice expressing HIV-1 genes. Virology. 1991;185:109–119. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90759-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan MK, Shimamura T, Chada K. Expression of the helix-loop-helix protein, Id, during branching morphogenesis in the kidney. Kidney Int. 1994;46:324–332. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falahatpisheh MH, Ramos KS. Ligand-activated Ahr signaling leads to disruption of nephrogenesis and altered Wilms′ tumor suppressor mRNA splicing. Oncogene. 2003;22:2160–2171. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeburg PB, Robert B, St John PL, Abrahamson DR. Podocyte expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1 and HIF-2 during glomerular development. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:927–938. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000059308.82322.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imabayashi T, Iehara N, Takeoka H, Uematsu-Yanagita M, Kataoka H, Nishikawa S, Sano H, Yokode M, Fukatsu A, Kita T, Doi T. Expression of basic helix-loop-helix proteins in the glomeruli. Clin Nephrol. 2001;55:53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue C, Bae SK, Takatsuka K, Inoue T, Bessho Y, Kageyama R. Math6, a bHLH gene expressed in the developing nervous system, regulates neuronal versus glial differentiation. Genes Cells. 2001;6:977–986. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama R, Ohtsuka T, Hatakeyama J, Ohsawa R. Roles of bHLH genes in neural stem cell differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2005;306:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp JB, Klotman ME, Adler SH, Bruggeman LA, Dickie P, Marinos NJ, Eckhaus M, Bryant JL, Notkins AL, Klotman PE. Progressive glomerulosclerosis and enhanced renal accumulation of basement membrane components in mice transgenic for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1577–1581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledent V, Paquet O, Vervoort M. Phylogenetic analysis of the human basic helix loop-helix proteins. Genome Biol. 2002;3:e0030. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-6-research0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinka S, Bruggeman LA. Persistent NF-{kappa}B activation in renal epithelial cells in mouse modelof HIV-associated nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;290:F657–665. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00208.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagishi M, Nakajima T, Fukamizu A. Molecular characterization of mesoderm-restricted basic helix-loop-helix protein, POD-1/Capsulin. Int J Mol Med. 2000;5:27–31. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.5.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundel P, Heid HW, Mundel TM, Kruger M, Reiser J, Kriz W. Synaptopodin: an actin-associated protein in telencephalic dendrites and renal podocytes. J Cell Biol. 1997a;139:193–204. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundel P, Reiser J, Zuniga Mejia BA, Pavenstadt H, Davidson GR, Kriz W, Zeller R. Rearrangements of the cytoskeleton and cell contacts induce process formation during differentiation of conditionally immortalized mouse podocyte cell lines. Exp Cell Res. 1997b;236:248–258. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson M, Durbeej M, Ekblom P, Hjalt T. Nulp1, a novel basic helix-loop-helix protein expressed broadly during early embryonic organogenesis and prominently in developing dorsal root ganglia. Cell Tissue Res. 2002;308:361–370. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0544-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piscione TD, Wu MY, Quaggin SE. Expression of Hairy/Enhancer of Split genes, Hes1 and Hes5, during murine nephron morphogenesis. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;4:707–711. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaggin SE, Schwartz L, Cui S, Igarashi P, Deimling J, Post M, Rossant J. The basic-helix-loop-helix protein pod1 is critically important for kidney and lung organogenesis. Development. 1999;126:5771–83. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.24.5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaggin SE, Vanden Heuvel GB, Igarashi P. Pod-1, a mesoderm-specific basic-helix-loop-helix protein expressed in mesenchymal and glomerular epithelial cells in the developing kidney. Mech Dev. 1998;71:37–48. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MD, Bruggeman LA, Hanss B, Sunamoto M, Marras D, Klotman ME, Klotman PE. Podocan, a novel small leucine-rich repeat protein expressed in the sclerotic glomerular lesion of experimental HIV-associated nephropathy. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33248–33255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301299200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MJ, Martinka S, D′Agati VD, Bruggeman LA. NF-κB regulates Fas-mediated apoptosis in HIV-associated nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2403–2411. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004121101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai H, Barros EJ, Tsukamoto T, Barasch J, Nigam SK. An in vitro tubulogenesis system using cell lines derived from the embryonic kidney shows dependence on multiple soluble growth factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:6279–6284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlondorff D. Preparation and study of isolated glomeruli. Methods Enzymol. 1990;191:130–140. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)91011-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz EJ, Cara A, Snoeck H, Ross MD, Sunamoto M, Reiser J, Mundel P, Klotman PE. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 induces loss of contact inhibition in podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:1677–1684. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1281677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman SM, Mehraban F, Komuves LG, Yang RB, Tomlinson JE, Zhang Y, Spriggs F, Topper JN. Gene expression profile of human endothelial cells exposed to sustained fluid shear stress. Physiol Genomics. 2002;12:13–23. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00102.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerman BA, Murre C, Oudejans CB. The cellular Pax-Hox-helix connection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1629:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]