Abstract

Preventing fractures in older people is important. But Teppo Järvinen and colleagues believe that we should be putting our efforts into stopping falls not treating low bone mineral density

Fractures are a rapidly growing problem among older people. Hip fractures alone cost over $20bn (£10bn; €13bn) in the United States in 1997.1 Any intervention that may reduce the risk of fracture at either the individual or population level therefore warrants critical appraisal. The mainstay of current strategies to prevent fractures is to screen for osteoporosis by bone densitometry and then treat people with low bone density with antiresorptive or other bone-specific drugs.2,3,4 However, the strongest single risk factor for fracture is falling and not osteoporosis.5 6 Despite this fact, few general practitioners will have assessed the risk of falling among their elderly patients or even know how to do it.7 Risk of falling is also completely overlooked in many important publications on preventing fractures.4 We argue that a change of approach is needed.

Predictive value of bone density measurements

Bone densitometry does not give reliable estimates of a person’s true bone mineral density. The planar scanning principle of dual energy x ray absorptiometry, and assumptions in processing the scan data, can underestimate or overestimate bone mineral density by 20-50%.8 This means that a patient with a bone mineral density T score of −1.5 may have a true value between −3.0 and 0−that is, a range from clear osteoporosis to normal. Thus, not surprisingly, bone mineral density is a poor predictor of fracture in individuals (fig 1). In addition, when different scanners are used on the same patients, the proportion of patients diagnosed with osteoporosis varies from 6% up to 15%.9

Fig 1 Femoral neck bone mineral density versus age at time of fall in people who did and did not sustain a hip fracture. Dashed lines show 2 SD less than peak bone mass for women (lower line) and men (upper line). Adapted from Greenspan et al

Over 80% of low trauma fractures occur in people who do not have osteoporosis (defined as T score ≤−2.5).11 Even if a T score of −1.5 is used to define osteoporosis, 75% of fractures would still occur in people without osteoporosis.11 Thus, bone mineral density gives general practitioners little indication which patient will sustain a fracture. In addition, changes in bone density in people taking antiresorptive drugs explain only 4-30% of the reduction in risk of vertebral and non-vertebral fractures.12

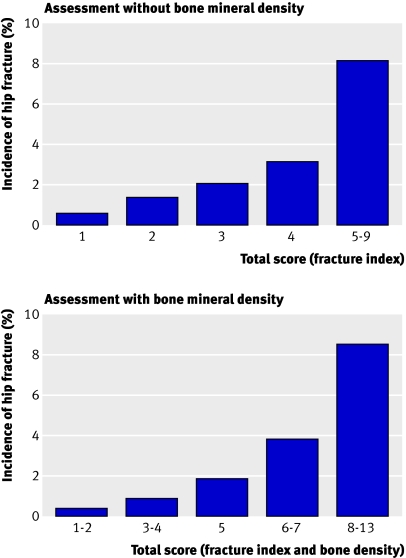

The fracture index, a simple risk assessment tool based on clinical risk factors (age, previous fracture, mother’s hip fracture occurrence, weight, smoking, and ability to rise from a chair without hands) can predict fractures in postmenopausal women as well as bone mineral density.3 Adding bone mineral density to the index only marginally improves its ability to predict hip or other fractures (fig 2).3

Fig 2 Five year incidence of hip fracture in postmenopausal women by score on fracture index (based on age, previous fracture, mother’s hip fracture occurrence, weight, smoking, and ability to rise from a chair without hands). The two panels illustrate the marginal effect of including bone mineral density on the ability of the index to predict future hip fractures. The finding was similar in other fractures. Adapted from Black et al

Absolute fracture risk

Partly because of the limitations of bone densitometry, the World Health Organization is devising a new model to calculate absolute fracture risk. The model combines, age specifically, six clinical risk factors (previous fracture, glucocorticoid use, family history of fracture, current cigarette smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and rheumatoid arthritis) with bone mineral density to estimate the 10 year probability of hip and other fractures.13 These probabilities can then be aligned with intervention thresholds for various drugs to combat osteoporosis.

It has been suggested that use of such algorithms would more accurately identify people at high risk of fracture and thus make treatment more cost effective,13 14 although the evidence to support these claims is insufficient. In addition, high scores in the absolute fracture risk model may be mainly attributable to increased risk of falling rather than skeletal factors. If this proves to be the case, antiresorptive and other bone-specific drugs will not prevent more fractures, as they cannot reduce the risk of falling. The tighter case definition would also leave a larger untreated population and thus may have only a marginal effect on the overall burden of fractures in the population. In fact, tightening the criteria for treatment with bone-specific drugs does not require a specific multifactorial fracture prediction model—the same result would be achieved by moving the T score threshold from, for example, −2.5 to −3.5.

Drug treatment is not a panacea

Bisphosphonates have reduced vertebral fractures in clinical trials of efficacy when about 90% of patients complied with three years of treatment.4 However, if a T score of ≤ −2.5 is used as the indication for treatment, the cost of preventing one vertebral fracture is about £23 500 (table), and 70% of fractures would still occur in the population. Adjusting the threshold to treat more people would sharply increase the costs per averted fracture (table). One reason for such relatively large costs might be that over half of symptomatic vertebral fractures are related to trauma.17

Predicted effects and cost of different strategies for preventing fracture in US white women with osteoporosis or osteopenia diagnosed by bone densitometry at hip or spine (mean age 72 years at baseline) and treated for 8.5 years (hip) and 3.7 years (spine)*

| Treatment strategy and site of measurement | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic cohort* | Treat if T score ≤ −2.5 | Treat if T score ≤−1.5 | Treat all | |||||||||||

| Hip | Spine | Hip | Spine | Hip | Spine | Hip | Spine | |||||||

| No of women | 8047 | 6892 | 1424 | 2274 | 3871 | 4108 | 8047 | 6892 | ||||||

| % of population | 100 | 100 | 17.7 | 33 | 48.1 | 59.6 | 100 | 100 | ||||||

| No of fractures in untreated women: | ||||||||||||||

| Any non-spine | 2044 | — | 580 | — | 782 | — | 2044 | — | ||||||

| Hip | 622 | — | 253 | — | 371 | — | 622 | — | ||||||

| Spine | 389 | 361 | 149 | 213 | 191 | 230 | 389 | 361 | ||||||

| No of fractures prevented by treatment†(% of fractures in basic cohort): | ||||||||||||||

| Any non-spine | — | — | 290 (14) | — | 379 (19) | — | 505 (25) | — | ||||||

| Hip | — | — | 127 (20) | — | 179 (29) | — | 204 (33) | — | ||||||

| Spine | — | — | 75 (19) | 107 (29) | 93 (24) | 114 (32) | 113 (29) | 127 (35) | ||||||

| Total cost of treatment ($m)‡ | — | — | 7.3 | 5.0 | 19.7 | 9.1 | 41.0 | 15.3 | ||||||

| Cost ($)/prevented fracture: | ||||||||||||||

| Any non-spine | — | — | 25 043 | — | 52 090 | — | 81 267 | — | ||||||

| Hip | — | — | 57 184 | — | 110 291 | — | 201 175 | — | ||||||

| Spine | — | — | 96 832 | 47 180 | 212 281 | 79 998 | 363 183 | 120 474 | ||||||

*Data derived from Stone et al11

† Assuming a best case scenario in which risk is reduced by 50% for all fractures in women with a T score below −2.5, by 44% for hip fracture and 20% for spine fracture in women with T score of −2.5 to −1.5, and by an estimated (in absence of data) 10% for women with a T score above −1.5.15 16

‡Based on an estimate of annual drug costs of $600 per patient with no costs attributed to bone densitometry, monitoring of treatment efficacy, or treating possible adverse events.

Less evidence exists to support drug treatment to prevent hip fractures than for vertebral fractures. Under idealised circumstances, 577 postmenopausal women must be treated for one year to avert one hip fracture, at a cost of about £120 000.18 Among women older than 80 (a high risk population), for whom drug therapy would theoretically be most effective, prevention of one hip fracture costs about £28 500 (table). This case-finding strategy, however, would prevent only about 20% of hip fractures occurring in the total population (table). Also, the only adequately sized clinical trial assessing the efficacy of bisphosphonates on hip fracture among this older age group, found no significant effect.19 Additionally, the efficacy, expense, and adverse effects of osteoporosis drugs have not been examined in nursing homes, where many hip fractures occur.20

Outside clinical trials, drug treatment is likely to be even less effective. Only 50% of patients are compliant a year after starting treatment, dropping to 20% after three years.21 An analysis (that assumes an unrealistic 70% compliance with bisphosphonates for five years) showed that we need to screen 731 women aged 65-69 years with bone densitometry and treat 88 of them with oral bisphosphonates (that is, those with osteoporosis) for five years to prevent one hip fracture.9 Among women aged 70-74, these numbers are 254 and 51, respectively. These figures support our claim that efforts to prevent fractures by bone specific drugs are extremely costly.

Shifting the focus

Numerous studies show that among older people falling, not osteoporosis, is the strongest risk factor for fracture.5 6 22 When a person falls, the type and severity of the fall (including fall height, energy, and direction) largely determine whether a fracture occurs.5 6 22 A 1 SD reduction in bone mineral density increases the fracture risk 2-2.5 times. By contrast, a sideways fall increases the risk of hip fracture three to five times, and when such a fall causes an impact to the greater trochanter of the proximal femur, hip fracture risk is raised about 30 times.22 These fall induced fracture risks are “strong” associations—comparable to those between smoking and lung cancer.

Thus, preventing falls is a logical approach to preventing fracture, but can falls be prevented? Evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomised trials shows that at least 15% of falls in older people can be prevented, with individual trials reporting reductions of up to 50%.6 23 The randomised trials used either a single intervention strategy (such as exercise) or multifactorial preventive programmes that included simultaneous assessment and reduction of predisposing and situational risk factors. Scientific evidence is most consistent for strength and balance training,24 followed by reduction in the number and doses of psychotropic drugs, dietary supplementation with vitamin D and calcium, and, in high risk populations, assessment and modification of home hazards.6 In addition, some randomised trials support more specific approaches such as expedited cataract surgery and cardiac pacing where indicated, and use of gait stabilising, antislip devices when walking outdoors under slippery winter conditions.6 25 26

These interventions can be administered alone or in combination. Prevention will require general practitioners to identify relevant risk factors and organise the appropriate intervention.

Preventing falls is laudable, but the ultimate question is whether it also prevents fractures. Unfortunately, no study into preventing falls has had sufficient power to use fractures as a primary outcome. Nevertheless, some randomised trials have reported that preventing falls among older adults also reduces the numbers of fractures, sometimes by over 50%.25 27,28,29,30,31,32 In addition, a meta-analysis of trials of interventions to prevent falls trials showed that the relative risk of injurious falls could be reduced by the same amount as falls alone (35%).24 All these findings are, however, preliminary, and we need a large multicentre randomised study to examine the effect of these interventions on fractures.

Preventing fall related fractures in general practice

The risk of falling still remains overlooked in clinical practice7 as well as in important publications4 on prevention of fractures. Paradoxically, the WHO omitted assessment of risk of falling from its absolute fracture risk model because it was “too difficult to assess for GPs.”14 This excuse is unacceptable when falling is the main aetiological factor in over 90% of hip fractures. Simple screening identifies populations at risk of falling with reasonable accuracy (box).33

General practice guidelines for assessment of risk of falling

-

Detailed history of current and past falls:

Fall in past 12 months

Indoor fall

Inability to get up after fall

-

Review of medical risk factors, especially:

Prescribed drugs (especially psychotropic)

Visual impairment

Cognitive function

Watch patient walk and movement to assess muscle strength, balance, and gait

Assess time taken to stand from sitting

As well as recommending interventions such as strength and balance training, sufficient intake of vitamin D and calcium, and smoking cessation, general practitioners should refer people identified as at high risk of falling for professional environmental assessment—for example, to occupational therapy.34 People who have difficulty in performing a simple sit to stand test or taking over 13 seconds to complete a simple timed “up and go test”35 should be referred to a geriatrician or falls clinic for a more comprehensive evaluation.

The physiological profile assessment instrument is a useful, inexpensive tool for evaluating risk of falling.36 Among older people living in the community, this well validated instrument has a 75% positive predictive accuracy for distinguishing multiple fallers in the next year from those who will fall once or less.36

Another question is whether general practitioners should prescribe hip protectors to prevent hip fractures related to falls. Hip protectors are designed to shunt the force and energy of impact away from the greater trochanter, thus preventing fracture.37 The first randomised clinical trials of hip protectors showed good efficacy, but later, more inconsistent, study results have been attributed to differences in study designs, variation in the devices’ capacity to attenuate biomechanical forces, and widely varying user compliance.20 37 Like antiresorptive drugs, hip protectors seem to have poor long term compliance.20 37

Nevertheless, current meta-analyses and systematic reviews suggest that in institutions with high rates of hip fracture, the use of hip protectors may reduce hip fractures by 23-60%.23 37,38,39 However, there is no evidence of benefit from hip protectors for lower risk people living in the community.38

In summary, it is time to shift the focus in fracture prevention from osteoporosis to falls. Falling is an under-recognised risk factor for fracture, it is preventable, and prevention provides additional health benefits beyond avoiding fractures.

Summary points

Falling, not osteoporosis, is the strongest single risk factor for fractures in elderly people

Bone mineral density is a poor predictor of an individual’s fracture risk

Drug treatment is expensive and will not prevent most fractures in elderly people

Randomised controlled trials show that falls in older people can be reduced by up to 50%

General practitioners should shift the focus in fracture prevention by systematically assessing risk of falling and providing appropriate interventions to reduce the risk

We thank Jacqueline Close, Stephen Lord, and BMJ editors for helpful comments.

Contributors and sources: The authors have a long experience and research interest in methodological issues of bone densitometry, epidemiology, and prevention of osteoporosis, falls, and fractures in elderly people. This article arose out of discussions at several meetings on osteoporosis and hip fracture prevention including, most recently, the Paulo symposium on preventing bone fragility and fractures in Tampere, Finland, May 2006.

TLNJ conceived the paper and wrote the first draft with KMK. All authors contributed to the initial critical review of the literature, planned the rationale for the article, contributed to the serial drafts and agreed the final submission. TLNJ is guarantor.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Braithwaite RS, Col NF, Wong JB. Estimating hip fracture morbidity, mortality and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:364-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NIH Consensus Development Panel. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA 2001;285:785-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black DM, Steinbuch M, Palermo L, Dargent-Molina P, Lindsay R, Hoseyni MS, et al. An assessment tool for predicting fracture risk in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 2001;12:519-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poole KE, Compston JE. Osteoporosis and its management. BMJ 2006;333:1251-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kannus P, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Palvanen M, Heinonen A, Sievanen H, et al. Why is the age-standardized incidence of low-trauma fractures rising in many elderly populations? J Bone Miner Res 2002;17:1363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannus P, Sievanen H, Palvanen M, Jarvinen T, Parkkari J. Prevention of falls and consequent injuries in elderly people. Lancet 2005;366:1885-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salter AE, Khan KM, Donaldson MG, Davis JC, Buchanan J, Abu-Laban RB, et al. Community-dwelling seniors who present to the emergency department with a fall do not receive guideline care and their fall risk profile worsens significantly: a 6-month prospective study. Osteoporos Int 2006;17:672-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolotin HH, Sievanen H. Inaccuracies inherent in dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry in vivo bone mineral density can seriously mislead diagnostic/prognostic interpretations of patient-specific bone fragility. J Bone Miner Res 2001;16:799-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson HD, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Allan JD. Screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: a review of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:529-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenspan SL, Myers ER, Maitland LA, Resnick NM, Hayes WC. Fall severity and bone mineral density as risk factors for hip fracture in ambulatory elderly. JAMA 1994;271:128-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone KL, Seeley DG, Lui LY, Cauley JA, Ensrud K, Browner WS, et al. BMD at multiple sites and risk of fracture of multiple types: long-term results from the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res 2003;18:1947-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seeman E. Is a change in bone mineral density a sensitive and specific surrogate of anti-fracture efficacy? Bone 2007;41:308-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, Johansson H, De Laet C, Brown J, et al. The use of clinical risk factors enhances the performance of BMD in the prediction of hip and osteoporotic fractures in men and women. Osteoporos Int 2007;18:1033-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverman SL. Selecting patients for osteoporosis therapy. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2006;4:91-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black DM, Thompson DE, Bauer DC, Ensrud K, Musliner T, Hochberg MC, et al. Fracture risk reduction with alendronate in women with osteoporosis: the fracture intervention trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:4118-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, Applegate WB, Barrett-Connor E, Musliner TA, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the fracture intervention trial. JAMA 1998;280:2077-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myers ER, Wilson SE. Biomechanics of osteoporosis and vertebral fracture. Spine 1997;22(24 suppl):25-31S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen ND, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV. Anti-hip fracture efficacy of biophosphonates: a bayesian analysis of clinical trials. J Bone Miner Res 2006;21:340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, Zippel H, Bensen WG, Roux C, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. N Engl J Med 2001;344:333-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiel DP, Magaziner J, Zimmerman S, Ball L, Barton BA, Brown KM, et al. Efficacy of a hip protector to prevent hip fracture in nursing home residents: the HIP PRO randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007;298:413-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Compston JE, Seeman E. Compliance with osteoporosis therapy is the weakest link. Lancet 2006;368:973-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinovitch SN, Inkster L, Maurer J, Warnick B. Strategies for avoiding hip impact during sideways falls. J Bone Miner Res 2003;18:1267-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliver D, Connelly JB, Victor CR, Shaw FE, Whitehead A, Genc Y, et al. Strategies to prevent falls and fractures in hospitals and care homes and effect of cognitive impairment: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ 2007;334:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson MC, Campbell AJ, Gardner MM, Devlin N. Preventing injuries in older people by preventing falls: a meta-analysis of individual-level data. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:905-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harwood RH, Foss AJ, Osborn F, Gregson RM, Zaman A, Masud T. Falls and health status in elderly women following first eye cataract surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:53-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKiernan FE. A simple gait-stabilizing device reduces outdoor falls and nonserious injurious falls in fall-prone older people during the winter. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:943-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Close J, Ellis M, Hooper R, Glucksman E, Jackson S, Swift C. Prevention of falls in the elderly trial (PROFET): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 1999;353:93-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen J, Lundin-Olsson L, Nyberg L, Gustafson Y. Fall and injury prevention in older people living in residential care facilities. A cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:733-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davison J, Bond J, Dawson P, Steen IN, Kenny RA. Patients with recurrent falls attending accident and emergency benefit from multifactorial intervention—a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2005;34:162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korpelainen R, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Heikkinen J, Vaananen K, Korpelainen J. Effect of impact exercise on bone mineral density in elderly women with low BMD: a population-based randomized controlled 30-month intervention. Osteoporos Int 2006;17:109-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashburn A, Fazakarley L, Ballinger C, Pickering R, McLellan LD, Fitton C. A randomised controlled trial of a home based exercise programme to reduce the risk of falling among people with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007;78:678-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stenvall M, Olofsson B, Lundstrom M, Englund U, Borssen B, Svensson O, et al. A multidisciplinary, multifactorial intervention program reduces postoperative falls and injuries after femoral neck fracture. Osteoporos Int 2007;18:167-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganz DA, Bao Y, Shekelle PG, Rubenstein LZ. Will my patient fall? JAMA 2007;297:77-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nikolaus T, Bach M. Preventing falls in community-dwelling frail older people using a home intervention team (HIT): results from the randomized falls-HIT trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitney JC, Lord SR, Close JC. Streamlining assessment and intervention in a falls clinic using the timed up and go test and physiological profile assessments. Age Ageing 2005;34:567-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lord SR, Menz HB, Tiedemann A. A physiological profile approach to falls risk assessment and prevention. Phys Ther 2003;83:237-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kannus P, Parkkari J. Hip protectors for preventing hip fracture. JAMA 2007;298:454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parker MJ, Gillespie WJ, Gillespie LD. Effectiveness of hip protectors for preventing hip fractures in elderly people: systematic review. BMJ 2006;332:571-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sawka AM, Boulos P, Beattie K, Papaioannou A, Gafni A, Cranney A, et al. Hip protectors decrease hip fracture risk in elderly nursing home residents: a bayesian meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:336-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]