Abstract

Parasites have evolved a plethora of strategies to ensure their survival. The intracellular parasite Theileria parva secures its propagation and spreads through the infected animal by infecting and transforming T cells, inducing their continuous proliferation and rendering them metastatic. In previous work, we have shown that the parasite induces constitutive activation of the transcription factor NF-κB, by inducing the constitutive degradation of its cytoplasmic inhibitors. The biological significance of NF-κB activation in T. parva-infected cells, however, has not yet been defined. Cells that have been transformed by viruses or oncogenes can persist only if they manage to avoid destruction by the apoptotic mechanisms that are activated on transformation and that contribute to maintain cellular homeostasis. We now demonstrate that parasite-induced NF-κB activation plays a crucial role in the survival of T. parva-transformed T cells by conveying protection against an apoptotic signal that accompanies parasite-mediated transformation. Consequently, inhibition of NF-κB nuclear translocation and the expression of dominant negative mutant forms of components of the NF-κB activation pathway, such as IκBα or p65, prompt rapid apoptosis of T. parva-transformed T cells. Our findings offer important insights into parasite survival strategies and demonstrate that parasite-induced constitutive NF-κB activation is an essential step in maintaining the transformed phenotype of the infected cells.

Theileria parva is an intracellular protozoan parasite that is transmitted by ticks and causes East Coast fever, a lymphoproliferative disorder of cattle in East and Central Africa (1). T. parva-induced T-cell transformation is the predominant mechanism underlying the pathogenesis of East Coast fever. Upon invasion by the parasite, T cells undergo lymphoblastoid transformation (2), become independent of antigen receptor stimulation (3, 4), and cease to require exogenous growth factors to proliferate (5, 6). T. parva-transformed T cells show many characteristics of tumor cells, including unlimited proliferation in vitro, clonal expansion, the formation of invasive tumors in nude mice, and lesions resembling multicentric lymphosarcoma (7, 8). Although the exact mode of transformation has not yet been elucidated, a number of host cell kinases, such as Src-family kinases (9, 10), jun-NH2-terminal kinase (4, 11), and casein kinase II (12, 13), with important functions in the regulation of T-cell activation, proliferation, and transformation have been found to be activated in a parasite-dependent manner in T. parva-transformed T cells (9, 14, 15). A unique aspect of T. parva-induced transformation is that it is entirely reversible (5, 16). Continuous proliferation depends on the presence of T. parva in the host cell cytoplasm. When the parasite is eliminated by treatment with the specific theilericidal drug BW720c, cells revert to a resting phenotype over a period of 3–4 days (5) and eventually undergo apoptosis (10).

Apoptosis is a widespread mechanism that is central to the maintenance of cellular homeostasis in all tissues, including the immune system (17). Apoptosis, or the lack of apoptosis, contributes to the pathogenesis of a number of diseases, including viral infection, autoimmune disease, and, in particular, cancer (18, 19). In the latter context, evidence has been accumulating that oncogenesis requires an antiapoptotic function that protects transformed cells from programmed cell death (20). The transcription factor NF-κB, which regulates the expression of a diverse set of genes involved in immune function, differentiation, and proliferation (21), also has been shown to contribute to cell survival by conveying protection against cell death, induced by a range of different apoptotic stimuli (22–28). It recently has been shown that this protection is conveyed by the induction of genes that encode different inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (29–32), which inhibit members of the caspase family of cell-death proteases (33).

NF-κB is regulated by cytoplasmic inhibitor proteins, IκBs, which sequester NF-κB in the cytoplasm, preventing its translocation to the nucleus and induction of κB-dependent gene expression. Signal-induced phosphorylation of IκB by IκB kinases (reviewed in ref. 34) targets IκB to a proteasomal degradation pathway, resulting in NF-κB release, nuclear translocation, and activation. In earlier work, it was demonstrated that transformation of T. parva-infected T cells is accompanied by high levels of NF-κB in the nucleus (35). More recently, it was shown that this transformation involves continuous parasite-dependent degradation of IκB, resulting in constitutive nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity (36). Upon elimination of the parasite, IκB degradation and NF-κB nuclear translocation are down-regulated (35, 36) and the expression of NF-κB-responsive genes such as the IL-2 and IL-2R genes (5, 37–39) is arrested.

Given that oncogenesis in tumor cells requires a functional antiapoptotic mechanism (18, 19, 40–42) and that NF-κB has been shown to suppress apoptosis induced by a range of stimuli, we investigated the specific role of parasite-induced NF-κB activation in the survival of T. parva-transformed T cells. We demonstrate that a stimulus to undergo spontaneous apoptosis is activated in T. parva-transformed T cells that is blocked, however, by activated NF-κB. Thus, in addition to inducing the expression of genes that contribute to proliferation (5, 37–39), permanently activated NF-κB is also critically required for the survival of T. parva-transformed T cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture.

T. parva-infected T cells (5) were cultured at 37°C in Leibovitz L15 medium containing 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FBS, 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.1), l-glutamine (2 mM), benzylpenicillin (100 units ml−1), and streptomycin sulfate (100 μg⋅ml−1) (cL15). Chemical inhibitors were added to the final concentrations as follows: N-α-tosyl-l-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone (TPCK, 25 μM; Sigma), BAY 11–7082 (50 μM; Calbiochem) or as indicated in the text.

Plasmids: Construction of pcDNA3-IS32A and p65ΔC.

The pcDNA3-IS32A construct was prepared by subcloning the IS32A cDNA fragment isolated from pcDNA3.Luc-IS32A (43) into the HindIII and BamHI sites of pcDNA3 (Invitrogen). The p65ΔC deletion mutant corresponding to bp 1–1248 of murine p65 cDNA was generated by reverse transcription–PCR and subcloned into pcDNA3 to generate pcDNA3-p65ΔC. pCMV-GFPsg25 was a kind gift of G. Pavlakis, (National Cancer Institute, Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center, Frederick, MD) and has been described (44).

Apoptosis Assay.

T. parva-infected cells were cultured at 2 × 105 cells ml−1 in cL15 for 5 h in the presence or absence of drugs. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed in cold PBS. After centrifugation cells were resuspended in cold staining buffer (10 mM Hepes/140 mM NaCl/5 mM CaCl2). Staining with recombinant annexin-V-FITC and propidiumiodide was done according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using standard protocols and a FACScan using lysysii software (Becton Dickinson).

Cell Lysates and Immunoblot Analysis.

Cells were collected and washed twice in ice-cold PBS, pH 7.4, and then processed for immunoblot analysis as described (36). A rabbit antipeptide polyclonal Ab with the following specificity was used: IκBα (C-terminal 21 amino acids; sc-371, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Bound primary Ab was detected by using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham Pharmacia).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA), Cell Transfection, and Chloramphenicol Acetyltransferase (CAT) Assays.

EMSA was carried out as described in standard protocols (35) using oligonucleotides (5′-GAGGGGACTTTCCG-3′ and its complement) in which the consensus NF-κB binding site is incorporated. Before preparation of nuclear extracts, cells were treated with 25 μM TPCK for 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 h. Plasmids used for transfection have been described (35). Plasmid −121/+232 HIV-CAT (abbreviated HIV-CAT) was derived by modification of pBLCAT5 containing the bacterial CAT gene. In HIV-CAT, the CAT gene is under control of an HIV-1 enhancer with two κB elements and the promoter region of the enhancer. Cells were transfected by electroporation using standard protocols (2 × 107 cells ml−1, 600-μl aliquots, 50 μg of plasmid DNA, 430 V, 250 μF). For cotransfection experiments 10 μg of HIV-CAT and 40 μg of the expression plasmids (pcDNA3-IS32A and p65ΔC) were used. After electroporation, cells were placed on ice for 5 min and then diluted in Leibovitz L15 medium and incubated at 37°C for 12 h, collected and washed with PBS, and then lysed by freeze-thawing in a CAT assay buffer (100 mM Tris, pH 7.4/1 mM EDTA/1 mM DTT). After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected, incubated for 6 min at 65°C, then recentrifuged. A 15-μl aliquot was assayed for CAT activity by using 9.25 × 103 Bq (250 nCi) of [14C]-chloramphenicol in CAT assay buffer supplemented with 100 μg BSA and 2 mg/ml n-butyryl CoA. Butyrylated chloramphenicol was extracted by using xylene, and activity was determined by liquid scintillation counting.

Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) Expression Assay.

T. parva-transformed T cells were transfected by electroporation with 50 μg of pCMV-GFPsg25 (44) as described above and cultured for 2 h in complete L15 medium containing FCS. TPCK (1 μM, 10 μM, 25 μM) then was added for 5 h and the number of GFP-expressing cells was counted by using a Neubauer chamber and immunofluorescence microscopy (×40 magnification). For cotransfection experiments 10 μg of pCMV-GFPsg25 and 40 μg of the expression plasmids (pcDNA3-IS32A and p65ΔC) were used.

RESULTS

Inhibitors of IκBα Phosphorylation Induce Apoptosis.

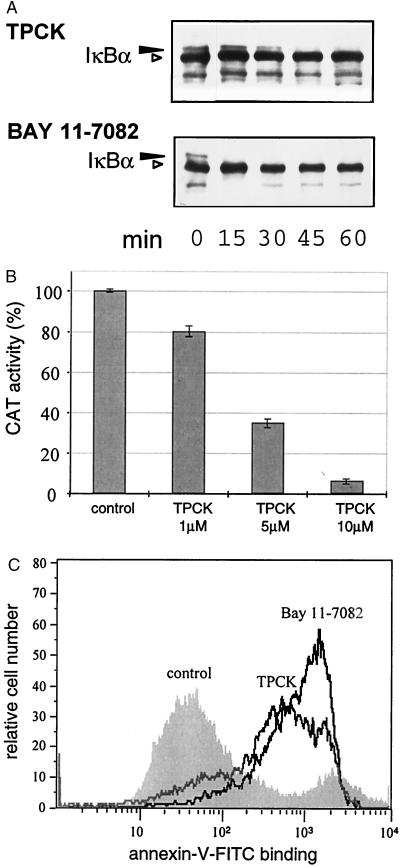

To determine whether the inhibition of NF-κB would initiate a cell death response, T. parva-transformed cells were treated with two potent inhibitors of the NF-κB activation pathway. TPCK (45, 46) and BAY 11–7082 (47) are unrelated compounds that both inhibit IκBα phosphorylation and subsequent degradation. Western blot analysis of IκBα revealed that treatment of T. parva-infected T cells with either compound resulted in a rapid block in IκBα phosphorylation as judged by the disappearance of the phosphorylated form of IκBα, which migrates with reduced electrophoretic mobility in SDS/PAGE (Fig. 1A, black arrowhead). The inhibition of phosphorylated IκBα formation was most pronounced in cells treated with BAY 11–7082. The effect of blocking IκBα phosphorylation on NF-κB transcriptional activity also was tested. Treatment of T. parva-transformed T cells with TPCK was accompanied by a dose-dependent arrest of κB-dependent HIV-CAT reporter gene expression (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

The inhibitors of IκB phosphorylation TPCK and BAY 11–7082 block NF-κB activation and induce apoptosis in T. parva-transformed T cells. (A) TPCK and BAY 11–7082 inhibit IκBα phosphorylation Whole-cell protein extracts were prepared from cells treated with TPCK (25 μM) or BAY 11–7082 (50 μM) for different lengths of time, and immunoblot analysis was carried out by using anti-IκBα antibodies. (B) T. parva-transformed cells were transfected with the −121/+232 HIV-CAT construct and cultured in the presence or absence of TPCK and CAT activity determined after 16 h. Error bars represent the SD for three independent experiments. (C) Logarithmically growing T. parva-infected T cells were treated with TPCK (25 μM) or BAY 11–7082 (50 μM) for 5 h, and annexin-V-FITC binding was analyzed by FACScan.

To see whether TPCK or BAY 11–7082 were capable of inducing apoptosis, T. parva-transformed T cells were analyzed by using an annexin-V binding assay. Annexin-V binds phosphatidylserine, which normally is situated on the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, but translocates to the outer layer of the membrane (cell surface) during the early phases of apoptosis, at a time when the cell membrane itself is still intact (48, 49). Flow-cytometric analysis showed that most cells bound FITC-labeled annexin V on exposure to either TPCK or BAY 11–7082 (Fig. 1C), with BAY 11–7082 being the strongest inducer of phosphatidylserine surface expression. Treated cells also showed the typical morphological hallmarks of apoptosis, including cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, and nuclear condensation (not shown).

Blocking NF-κB Activation Reveals a Temporal Relationship with the Induction of Apoptosis.

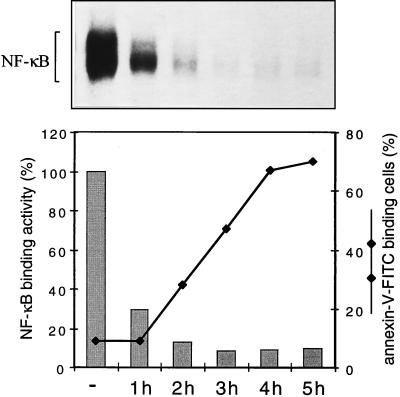

To test whether a correlation exists between the occurrence of apoptosis and NF-κB inhibition, a time-course experiment was carried out in which the effect of TPCK on NF-κB DNA binding activity, measured in a quantitative electrophoretic mobility-shift assay, and annexin V-FITC binding was monitored over a period of 5 h (Fig. 2). The block of IκBα phosphorylation induced by TPCK (see Fig. 1A), which became apparent within 30 min and was complete within 45 min, was accompanied by the arrest of DNA binding activity. The latter could be observed within 1 h of treatment and was almost complete within 2 h. The decrease in NF-κB DNA binding activity, in turn, immediately preceded the onset of apoptosis, with the first annexin V-FITC binding cells being detectable at 2 h, steadily increasing to a maximum at 5 h. This observation shows that TPCK-mediated inhibition of NF-κB correlates closely with the induction of apoptosis. Similarly, the inhibition of NF-κB DNA binding by BAY 11–7082 (not shown) and induction of apoptosis by BAY 11–7082 (Fig. 1B) were preceded by a block in IκBα phosphorylation (Fig. 1A, Lower).

Figure 2.

The inhibition of NF-κB DNA binding activity correlates with the induction of apoptosis. Cells were treated with TPCK (25 μM) for different times as indicated. NF-κB complexes present in nuclear extracts were demonstrated by electrophoretic mobility-shift assay (Upper) and quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis (Lower, gray bars). Cells also were analyzed by FACScan, and the percentage of annexin-V-FITC binding cells were determined at each time point (Lower).

Direct Interference with Components of the NF-κB Activation Pathway Induces Apoptosis.

Despite the fact that TPCK-induced and BAY 11–7082-induced apoptosis correlated closely with NF-κB inhibition, it could not be completely excluded that these inhibitors induce apoptosis by affecting other signaling pathways that are essential for maintaining cell survival. To confirm the antiapoptotic role of NF-κB in T. parva-transformed T cells in a direct manner, we designed transfection experiments aimed at interfering directly with specific components of the NF-κB activation pathway through the expression of dominant negative mutants.

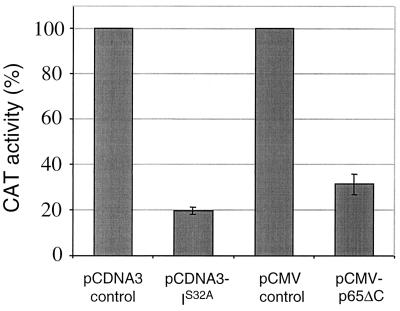

We used a repressor form of IκBα, which contains a serine-to-alanine mutation at residue 32 (IκBαS32A) (43). This mutation prevents IκBα phosphorylation by IκB kinase and subsequent proteasomal degradation (50, 51), impeding both NF-κB nuclear translocation and DNA binding. In a second approach, a dominant negative mutant form of the NF-κB subunit p65 lacking the transcriptional activation domain [p65(Δ)C] was used to inhibit NF-κB transcriptional activity. Transient expression of IκBαS32A and p65(Δ)C in T. parva-transformed T cells that were cotransfected with the HIV-CAT reporter construct caused a reduction in κB-dependent CAT activity of 80.3% and 58.7%, respectively (Fig. 3), demonstrating that both constructs effectively reduced NF-κB transcriptional activity in T. parva-transformed T cells.

Figure 3.

Dominant negative mutant forms of IκBα and p65 inhibit NF-κB transcriptional activity in T. parva-transformed T cells. CAT activity was monitored in cells that were cotransfected with −121/+232 HIV-CAT (10 μg) and either the empty expression vectors pcDNA3 and pCMV, or the expression vectors pcDNA3-IS32A or pCMV-p65ΔC (40 μg each). Data are presented as percentage of CAT activity measured for cells transfected with the corresponding control plasmid constructs. Error bars represent the SD for three independent experiments.

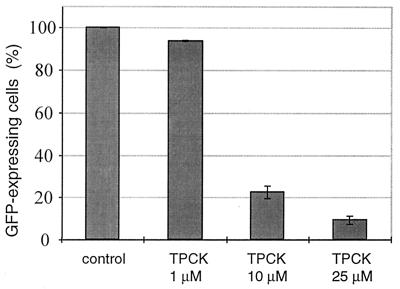

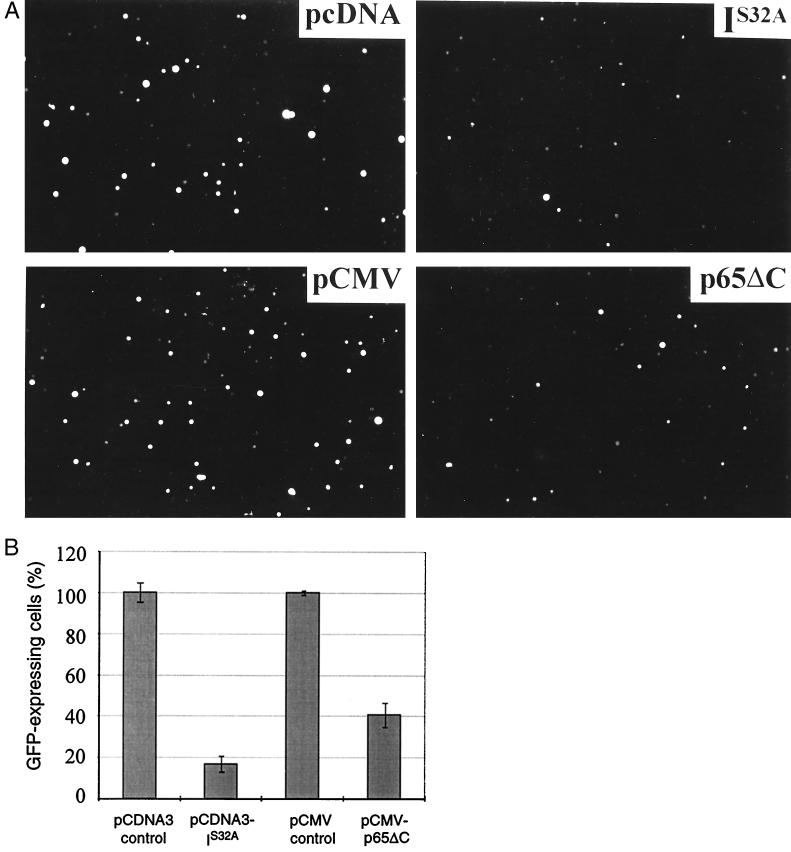

To monitor the effects of NF-κB inhibition on cell viability at the level of individual cells, an assay system first had to be established that allows the induction of apoptosis T. parva-transformed T cells to be visualized. A cell viability assay, developed to study apoptosis in adherent cells and which relies on the expression of a reporter gene by viable, transiently transfected cells (20, 52, 53), was adapted for T. parva-transformed T cells. In this assay, T. parva-transformed T cells were transfected with the pCMV-GFPsg25 expression plasmid (44) and the number of cells expressing GFP was monitored in the presence or absence of NF-κB inhibition. Fig. 4 demonstrates how upon TPCK treatment the number of T. parva-transformed T cells expressing GFP decreased in a dose-dependent manner. To test whether transient expression of dominant negative mutants that block NF-κB activation also affects cell viability, T. parva-transformed T cells were cotransfected with pCMV-GFPsg25 and either vectors encoding IκBαS32A or p65(Δ)C, or the corresponding empty expression vectors. Expression of either IκBαS32A or p65(Δ)C resulted in a marked reduction in the number of GFP-expressing cells (Fig. 5A). Quantitation revealed a reduction by 83% and 59%, respectively (Fig. 5B). FITC-labeled annexin-V binding experiments carried out on individual cells in which both dominant negative mutants were transiently expressed revealed a corresponding increase in the number of apoptotic cells (not shown).

Figure 4.

Analysis of GFP expression in T. parva-transformed T cells undergoing apoptosis. Cells were transfected with the plasmid pCMV-GFPsg25 (50 μg) and treated for 5 h with TPCK as indicated. GFP expression was monitored in a counting chamber by using a fluorescence microscope. Error bars represent the SD for three independent experiments.

Figure 5.

Expression of IκBαS32A or p65(Δ)C induces apoptosis in T. parva-transformed T cells. (A) Immunofluorescence micrographs (final magnification ×100) of cells cotransfected with pCMV-GFPsg25 and either the empty expression vectors pCDNA3 and pCMV, or vectors expressing IκBαS32A or p65(Δ)C. (B) Quantitation of GFP-expressing cells. T. parva-transformed T cells were transfected as described above, and the number of cells expressing GFP was monitored in a counting chamber by using a fluorescence microscope. Error bars represent the SD for three separate experiments.

DISCUSSION

Our results provide direct evidence that T cells transformed by T. parva require an intact, constitutively activated NF-κB pathway to escape apoptosis. The transformation of eukaryotic cells by viruses is a well-documented phenomenon (54), but among parasites, Theileria is unique in its ability to transform the cells it infects (9, 15, 55) and is also the only eukaryote known to transform another eukaryote. Most normal cells depend on tissue environment-specific factors to maintain viability and proliferate (56, 57). T. parva-transformed T cells appear to circumvent these homeostatic mechanisms by becoming independent of antigenic stimulation and exogenous growth factors (4–6), which allows them to proliferate in nonlymphoid as well as lymphoid tissues (8). Transformation is normally an irreversible event, and acquiring resistance to apoptotic cell death is an essential step in the progression to malignancy (40). Transformation by T. parva differs from other transformation processes in that it is reversible. Our findings show, however, that T cells transformed in this manner do not escape the requirement for protection against spontaneous apoptosis, and that protection is achieved by constitutive NF-κB activation. In this respect, T. parva-transformed T cells closely resemble murine immature B cell lymphoma WEHI 231 cells (58) and human cutaneous T cell lymphoma HuT-78 cells (59), which also appear to require NF-κB to become resistant to spontaneous apoptosis. It recently has been shown that oncogenic Ras initiates not only transformation in NIH 3T3 cells, but also an apoptotic response that is suppressed by the Ras-induced activation of NF-κB (20). Thus, in the same way that the ability of oncogenic Ras to transform cells depends on its capacity to activate NF-κB, T. parva-induced T-cell transformation requires parasite-dependent constitutive NF-κB activation.

The intralymphocytic schizont stage of T. parva is the only proliferative stage in the mammalian part of the parasite life cycle. Parasite survival therefore strictly depends on persistently infected T cells. By analogy to virus-infected cells (60, 61), early apoptosis would severely limit parasite production and eliminate the spread of parasites in the host. Similar strategies appear to be used by bacteria, and in this context, NF-κB activation has been shown to guarantee cell survival during Rickettsia rickettsii infection (62). T. parva-induced NF-κB activation may protect T cells at more than one level. For example, T. parva-transformed T cells acquire solid resistance to tumor necrosis factor-induced cytotoxicity (63), and observations made in several other systems (22–25) strongly suggest that this resistance is most likely to be mediated by NF-κB. Interestingly, NF-κB activation recently has been demonstrated for two other apicomplexan parasites, Plasmodium and Toxoplasma (64–66), raising the possibility that this is a common characteristic of parasites belonging to the phylum Apicomplexa. The fact that an NF-κB-dependent antiapoptotic pathway exists in T. parva-transformed T cells does not exclude the existence of other antiapoptotic mechanisms. In this regard, initial observations in our laboratory indicate that the death receptor FAS/APO-1 is down-regulated in T. parva-transformed T cells, compared with uninfected Con A-stimulated T cells.

T. annulata transforms cells of monocyte/macrophage- or B-cell lineage, and NF-κB also is activated in these cell lines. It will be interesting to find out whether such cells also rely on a NF-κB-dependent mechanism to avoid apoptosis. That T. parva may not be alone among parasites to induce resistance to apoptosis is suggested by the fact that cells infected with Toxoplasma gondii are resistant to multiple inducers of apoptosis (67), and it will be of interest to determine whether NF-κB activation induced by T. gondii infection (64) also is involved in these processes.

In conclusion, during the course of evolution, parasites have developed a broad spectrum of strategies to survive immune attack, including antigenic variation, molecular mimicry, and resistance to immunological effector mechanisms (68). T. parva has taken this to the extreme, first, by taking up residence inside those cells that have evolved to destroy invading organisms and, second, by inducing uncontrolled proliferation of the host cell and activating the antiapoptotic pathways that are required to maintain the transformed phenotype.

Acknowledgments

I. Roditi, G. Bertoni, E. Peterhans, E. Müller, and M. Schweizer are thanked for comments. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF No. 31.43328.95 to D.A.E.D.), the Federal Office for Education and Science (European Union collaboration Grant No. 95.0696), and a grant from the Swiss Cancer League (KFS 625-2-1998). P.C.F. is a recipient of Swiss National Science Foundation Stipend 31.44407.95 for the MD-Ph.D program.

ABBREVIATIONS

- TPCK

N-α-tosyl-l-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone

- CAT

chloramphenicol acetyltransferase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

References

- 1.Morrison W I, Lalor P A, Goddeeris B M, Teale A J. In: Parasite Antigens, Toward New Strategies for Vaccines. Pearson T W, editor. New York: Dekker; 1986. pp. 167–213. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown C G, Stagg D A, Purnell R E, Kanhai G K, Payne R C. Nature (London) 1973;245:101–103. doi: 10.1038/245101a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldwin C L, Teale A J. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:1859–1862. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830171230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galley Y, Hagens G, Glaser I, Davis W C, Eichhorn M, Dobbelaere D A E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5119–5124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobbelaere D A, Coquerelle T M, Roditi I J, Eichhorn M, Williams R O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4730–4734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown W C, Logan K S. Parasite Immunol. 1986;8:189–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1986.tb00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irvin A D, Brown C G, Kanhai G K, Stagg D A. Nature (London) 1975;255:713–714. doi: 10.1038/255713a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison W I, Buscher G, Murray M, Emery D L, Masake R A, Cook R H, Wells P W. Exp Parasitol. 1981;52:248–260. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(81)90080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eichhorn M, Dobbelaere D A E. Parasitol Today. 1994;10:469–472. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(94)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fich C, Klauenberg U, Fleischer B, Broker B M. Parasitology. 1998;117:107–115. doi: 10.1017/s0031182098002832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botteron C, Dobbelaere D. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:418–421. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ole-MoiYoi O K, Brown W C, Iams K P, Nayar A, Tsukamoto T, Macklin M D. EMBO J. 1993;12:1621–1631. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ole-MoiYoi O K. Science. 1995;267:834–836. doi: 10.1126/science.7846527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seldin D C, Leder P. Science. 1995;267:894–897. doi: 10.1126/science.7846532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaussepied M, Langsley G. Res Immunol. 1996;147:127–138. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(96)83165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hudson A T, Randall A W, Fry M, Ginger C D, Hill B, Latter V S, McHardy N, Williams R B. Parasitology. 1985;90:45–55. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000049003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osborne B A. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evan G. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:709–711. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970529)71:5<709::aid-ijc2>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wyllie A H. Eur J Cell Biol. 1997;73:189–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayo M W, Wang C Y, Cogswell P C, Rogers Graham K S, Lowe S W, Der C J, Baldwin A S J. Science. 1997;278:1812–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5344.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baldwin A S J. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:649–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Antwerp D J, Martin S J, Kafri T, Green D R, Verma I M. Science. 1996;274:787–789. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang C Y, Mayo M W, Baldwin A S., Jr Science. 1996;274:784–787. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beg A A, Baltimore D. Science. 1996;274:782–784. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Z G, Hsu H, Goeddel D V, Karin M. Cell. 1996;87:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arsura M, Wu M, Sonenshein G E. Immunity. 1996;5:31–40. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertrand F, Atfi A, Cadoret A, L’Allemain G, Robin H, Lascols O, Capeau J, Cherqui G. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2931–2938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baichwal V R, Baeuerle P A. Curr Biol. 1997;7:R94–R96. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chu Z L, McKinsey T A, Liu L, Gentry J J, Malim M H, Ballard D W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10057–10062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liston P, Roy N, Tamai K, Lefebvre C, Baird S, Cherton-Horvat G, Farahani R, McLean M, Ikeda J E, MacKenzie A, Korneluk R G. Nature (London) 1996;379:349–353. doi: 10.1038/379349a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stehlik C, de Martin R, Kumabashiri I, Schmid J A, Binder B R, Lipp J. J Exp Med. 1998;188:211–216. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang C Y, Mayo M W, Korneluk R G, Goeddel D V, Baldwin A S J. Science. 1998;281:1680–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devereaux Q L, Takahashi R, Salvesen G S, Reed J C. Nature (London) 1997;388:300–304. doi: 10.1038/40901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stancovski I, Baltimore D. Cell. 1997;91:299–302. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ivanov V, Stein B, Baumann I, Dobbelaere D A, Herrlich P, Williams R O. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:4677–4686. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.11.4677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmer G H, Machado J J, Fernandez P, Heussler V, Perinat T, Dobbelaere D A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12527–12532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dobbelaere D A, Prospero T D, Roditi I J, Kelke C, Baumann I, Eichhorn M, Williams R O, Ahmed J S, Baldwin C L, Clevers H, et al. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3847–3855. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.3847-3855.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coquerelle T M, Eichhorn M, Magnuson N S, Reeves R, Williams R O, Dobbelaere D A. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:655–659. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heussler V T, Eichhorn M, Reeves R, Magnuson N S, Williams R O, Dobbelaere D A. J Immunol. 1992;149:562–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson C B. Science. 1995;267:1456–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.7878464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bold R J, Termuhlen P M, McConkey D J. Surg Oncol. 1997;6:133–142. doi: 10.1016/s0960-7404(97)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lyons S K, Clarke A R. Br Med Bull. 1997;53:554–569. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen C G, Malliaros J, Katerelos M, d’Apice A J, Pearse M J. Mol Immunol. 1996;33:57–61. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(95)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stauber R H, Horie K, Carney P, Hudson E A, Tarasova N I, Gaitanaris G A, Pavlakis G N. BioTechniques. 1998;24:462–466. doi: 10.2144/98243rr01. , 468–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jung S, Yaron A, Alkalay I, Hatzubai A, Avraham A, Ben Neriah Y. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1995;766:245–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb26672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guesdon F, Ikebe T, Stylianou E, Warwick Davies J, Haskill S, Saklatvala J. Biochem J. 1995;307:287–295. doi: 10.1042/bj3070287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pierce J W, Schoenleber R, Jesmok G, Best J, Moore S A, Collins T, Gerritsen M E. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21096–21103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verhoven B, Schlegel R A, Williamson P. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1597–1601. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thiagarajan P, Tait J F. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17420–17423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palombella V J, Rando O J, Goldberg A L, Maniatis T. Cell. 1994;78:773–785. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen Z, Hagler J, Palombella V J, Melandri F, Scherer D, Ballard D, Maniatis T. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1586–1597. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.13.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar S, Kinoshita M, Noda M, Copeland N G, Jenkins N A. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1613–1626. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.14.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hsu H, Xiong J, Goeddel D V. Cell. 1995;81:495–504. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vousden K H, Farrell P J. Br Med Bull. 1994;50:560–581. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams R O, Dobbelaere D A. Semin Cell Biol. 1993;4:363–371. doi: 10.1006/scel.1993.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raff M C, Barres B A, Burne J F, Coles H S, Ishizaki Y, Jacobson M D. Science. 1993;262:695–700. doi: 10.1126/science.8235590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams G T, Smith C A, Spooncer E, Dexter T M, Taylor D R. Nature (London) 1990;343:76–79. doi: 10.1038/343076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu M, Lee H, Bellas R E, Schauer S L, Arsura M, Katz D, FitzGerald M J, Rothstein T L, Sherr D H, Sonenshein G E. EMBO J. 1996;15:4682–4690. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giri D K, Aggarwal B B. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14008–14014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.14008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Teodoro J G, Branton P E. J Virol. 1997;71:1739–1746. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1739-1746.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tschopp J, Thome M, Hofmann K, Meinl E. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:82–87. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clifton D R, Goss R A, Sahni S K, van Antwerp D, Baggs R B, Marder V J, Silverman D J, Sporn L A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4646–4651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.DeMartini J C, Baldwin C L. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4540–4546. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4540-4546.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gazzinelli R T, Sher A, Cheever A, Gerstberger S, Martin M A, Dickie P. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1645–1655. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schofield L, Novakovic S, Gerold P, Schwarz R T, McConville M J, Tachado S D. J Immunol. 1996;156:1886–1896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tachado S D, Gerold P, McConville M J, Baldwin T, Quilici D, Schwarz R T, Schofield L. J Immunol. 1996;156:1897–1907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nash P B, Purner M B, Leon R P, Clarke P, Duke R C, Curiel T J. J Immunol. 1998;160:1824–1830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beverley S M. Cell. 1996;87:787–789. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81984-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]