Many rural communities are desperate to recruit and retain physicians. Although there are important shortages of family physicians and specialists in all areas of Canada, physicians in rural areas are far fewer in number and fulfill a wider range of roles. The loss of a single physician from a rural community can change how the entire health care system is organized and run.

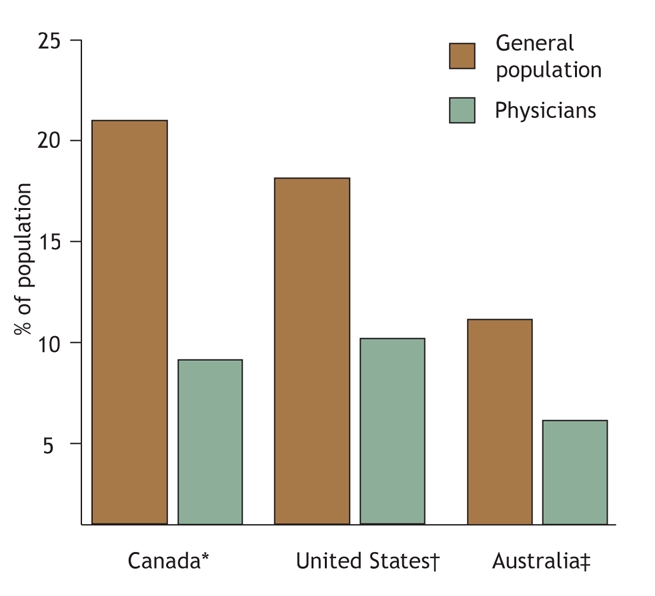

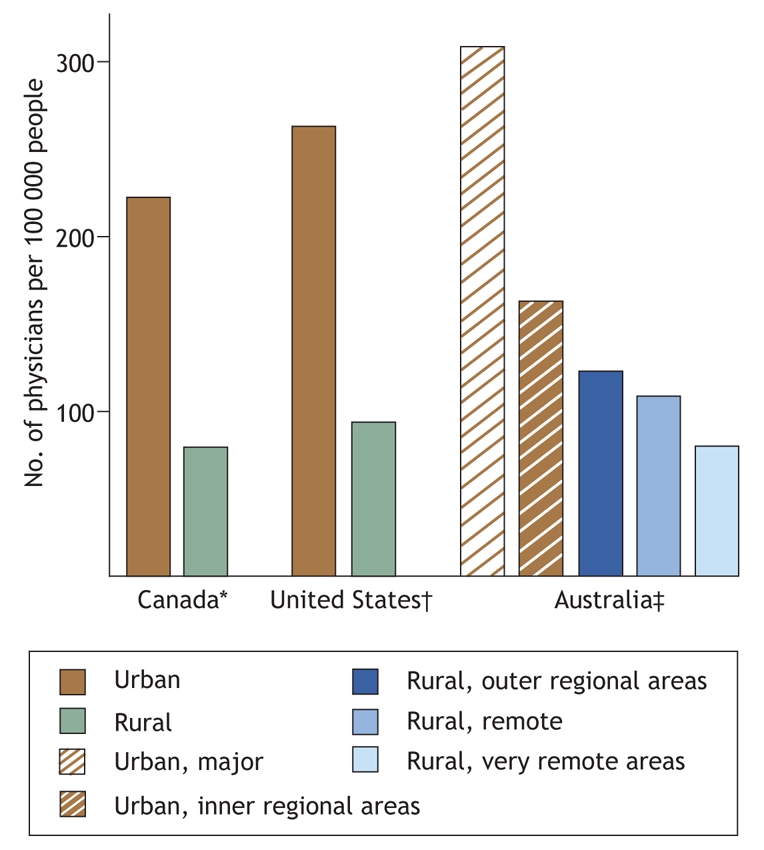

One might ask whether there is a maldistribution of physicians favouring urban centres. Indeed, a detailed analysis of the practice locations of Canadian physicians in 2004 showed that 9.4% of physicians (15.7% of family physicians and 2.4% of specialists) were located in rural areas. In contrast, 21.4% of the general population resided in rural areas.1 This is slightly worse than in 1998, when 9.8% of physicians and 22.2% of the population lived in rural areas.1 The United States and Australia are experiencing similar shortages (Figure 1, Figure 2). The shortage of rural physicians, however, is not limited to large or developed countries.

Figure 1: Physicians and general population in rural areas of Canada,1 the United States2 and Australia.3 *Includes communities up to 10 000 people. †Includes all non-metropolitan areas. ‡Includes outer regional, remote and very remote areas.

Figure 2: Physicians practising in urban and rural areas of Canada, the United States2 and Australia.3 Data for Canada: Dr. Ray Pong and Dr. Roger Pitblado, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario: personnel communication, 2007.

It is estimated that in 2004, an additional 1308 family physicians would have been needed in rural areas to equalize the family physician–population ratio between rural and urban areas of Canada. This would have required more than a 25% increase in the number of rural family physicians. And yet, even this probably wouldn't have been enough. Rural family physicians spend substantially more time than urban physicians providing hospital-based patient care (including treating patients in the emergency department, acting as the primary physician for hospital inpatients, providing intra-partum obstetrics care and, occasionally, working as an anesthesiologist4), which leaves rural family physicians less time to provide office-based primary care.

The supply pool for Canadian rural physicians consists of Canadian medical graduates and international medical graduates. In 2004, 26.3% of physicians in rural Canada were international medical graduates, compared with 21.9% of physicians in urban areas.1 However, the proportion of international medical graduates practising in rural areas is unlikely to increase. The traditional recruitment of international medical graduates from developing countries is in part responsible for the high cost of training and the devastating loss of physicians in the developing world, particularly Africa.5 Increasing the number of Canadian medical graduates interested in rural practice will be essential to developing a stable and sufficient rural physician workforce.

Although some urban physicians relocate to rural areas, rural physicians are more likely to move to urban areas. Each year from 2001–2005, an average of 368 (almost 8%) physicians moved from rural to urban areas, compared with 241 (about 0.5%) physicians who moved from urban to rural areas (Tara S. Chauhan, Canadian Medical Association, Ottawa, Ontario: personal communication, 2007).

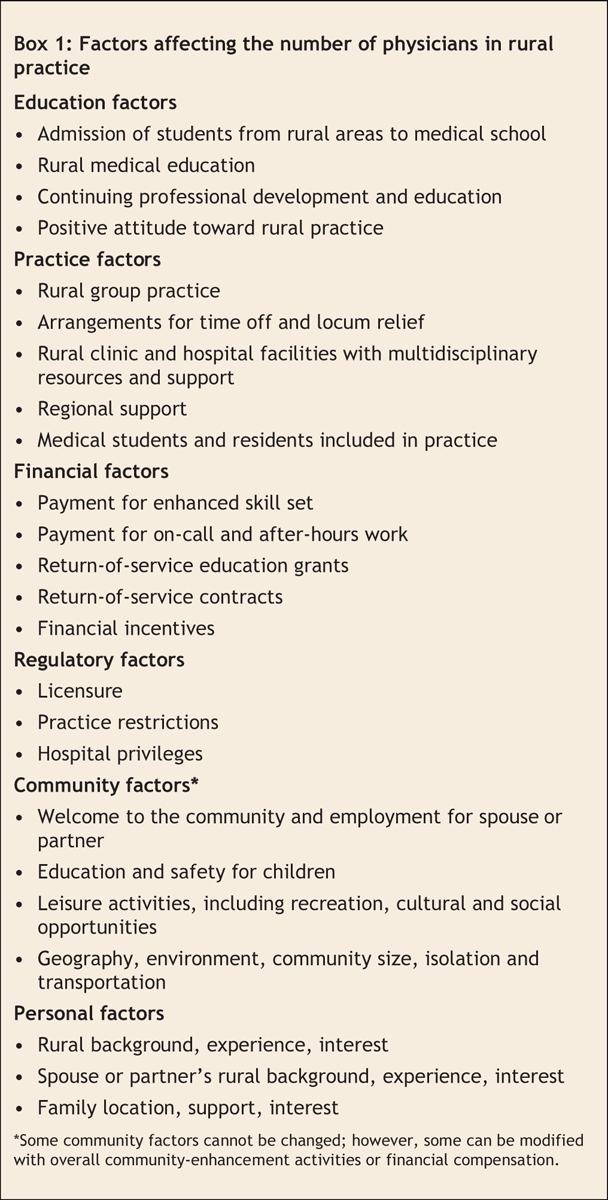

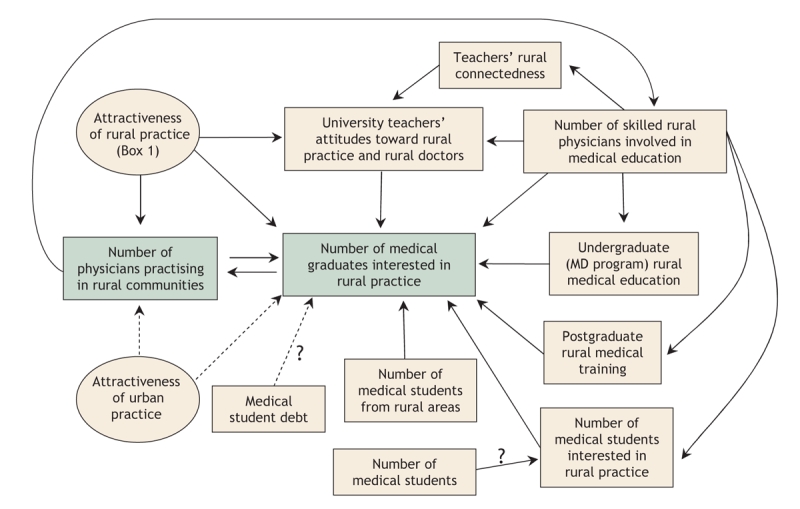

There are a number of solutions to address the dire need for physicians in remote areas. Like career choice, the selection of practice location involves a complex interplay of personal and professional preferences. Physicians often consider their education and desired practice type as well as financial, regulatory and community factors. Many of these complex, interrelated factors can be enhanced locally, regionally and provincially, and they all contribute to the ability of rural communities to attract physicians (Box 1, Figure 3).6,7,8

Box 1.

Figure 3: Interplay of positive (solid arrows) and negative (dashed arrows) factors that affect the number of medical graduates interested in rural practice.

In Canada, there has been a rapid increase in the last 10 years in the number of students enrolled in medical school, rising from 1563 in 1997/98 to 2458 in 2006/07. However, only about 11% of these students are from rural areas, compared with the 22% of students that would be expected based on Canada's population (Dr. Shaheed Merani [University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta], Dr. Sonia Abdulla [University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario], Dr. Ian Johnson [University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario]: personal communication 2007).9 Strategies have been developed to increase the number of students from rural areas.10 In Australia, the number of medical students from rural areas has increased from 10% in 1989 to 25% in 2000 because of new bursaries and scholarships for students from rural areas, changes to admission policies and the creation of additional spots for students from rural areas.11

Education plays an important role in recruiting and retaining rural physicians.12 A recent Ontario study found that, in addition to being from a rural area, undergraduate rural medical education and postgraduate rural training were independently associated with practising in a rural location.13 Some students from urban areas may develop, through their life and learning experiences, an interest in rural medicine that leads them to rural practice. Involving skilled rural physicians in medical education is vital, and increasing the number of these physicians can increase the number of graduating physicians interested in rural practice through role modeling, positively influencing university teacher's attitudes toward rural practice and physicians, and increasing the capacity of rural medical education for students and residents.

In a 2003 Ontario survey, family medicine residents and practising rural physicians reported that the following practice solutions would help to retain rural physicians: limiting on-call requirements, a locum program to provide time off, sessional payment for emergency, anesthesia and obstetrics work, and a user-friendly network for specialist referral.6 A survey of general practitioner trainees in New Zealand reported that two-thirds would consider practising in a rural area if similar incentives were implemented, including reduced on-call work, guaranteed time away from their practice and improved options for partners and children.14

Do financial incentives help to attract and retain physicians in rural areas? In a systematic review of financial incentives provided to physicians practising in rural or underserviced areas of the United States, Canada and New Zealand, Sempowski reported that return-of-service programs were successful in short-term recruitment but less successful in long-term retention.15 Sempowski noted, however, that the quality of evidence of the included studies was low and the results were of limited applicability to Canada.15 The 1 prospective cohort study included in the review found that physicians who voluntarily chose to practise in rural areas were far more likely to stay longer than those who located to rural areas as part of a return-of-services commitment.15,16 In contrast, a study of 69 US state-run programs reported that physicians who were obligated (by return-of-service commitments) to practice in rural or underserviced areas were slightly more likely than non-obligated physicians to stay longer (55% of obligated physicians stayed over 8 years compared with 52% of non-obligated physicians).17 This study reported that programs that provided incentives to physicians entering practice and to residents were more successful than for programs aimed at medical students. The increasing costs of medical education and student debt may decrease physicians' interest in rural practice, leading them to chose a more lucrative urban specialty.9

In some provinces, international medical graduates are generally offered specific service contracts for underserviced locations. Although there is no formal system of practice location restriction regulations in Canada, hospital privileges and support services, such as operating-room time are controlled, sometimes to the advantage of rural practitioners.

It is reasonable that physicians who are considering practising in a rural location should be able to expect a collegial, well-functioning group practice (with appropriate arrangements for time off) supported by a multi-professional team and a modern clinic with appropriate, up-to-date hospital facilities. Rural physicians may also be energized and stimulated by the inclusion of medical students and residents in their practice, which also serves to introduce the students and residents to the joys and challenges of rural practice. In the last decade, we have seen much improvement in the provision of facilities and the development of group practices in many rural communities. Few would see the continuation of the solo, isolated rural practitioner as viable. There have also been long-overdue improvements in the payment system to provide more appropriate compensation for the added skills and hospital-based responsibilities and night and weekend calls that go along with being a rural family physician. Rural specialists, most often general surgeons and general internists, also have very broad practice patterns and very heavy on-call burden. Additional financial incentives are generally required to attract physicians to the more isolated communities.

Regional support, including specialty clinics, telemedicine and a functioning referral system with regional centre acceptance of patients who urgently require higher level care, is vital. Rural physicians describe a disturbing shift at some referral centres from “Yes, I agree that the patient needs to be transferred. We will make arrangements at our end” to “I'm sorry, we're full and can't accept your patient. You will need to make arrangements with another centre.” This shift is placing enormous strain on rural physicians who have limited local resources, especially when alternative arrangements are even more distant and difficult to arrange.

Community factors are highly important to physicians and their partners and families when selecting a practice location. Everything from the initial welcome to recreation and lifestyle, spousal employment opportunities and children's education is carefully considered. Rural communities can be wonderful places to live, particularly if physicians have time to enjoy the benefits of a rural lifestyle.

In summary, increasing the number of rural physicians in Canada and elsewhere will require the improvement of many factors, including medical school enrollment, financial incentives and resources. A strong rural health strategy to provide care to rural Canadians is needed. This must include a sufficient number of appropriately trained physicians to practise in modern rural health care facilities as part of collegial multiprofessional teams supported by a well-functioning referral network.

Increasing the number of rural physicians will require:

• Increased numbers of medical students from rural areas.

• More rural undergraduate medical education and rural-focused postgraduate training.

• Enhanced return-of-service programs.

• Improved financial incentives for rural practice.

• Stable rural group practices with appropriate facilities and health care teams.

• Community involvement and support.

• Functional referral networks.

Acknowledgments

I thank Drs. Ray Pong and Roger Pitblado for their help in accessing physician demographic information.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. James Rourke, Dean of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Health Sciences Centre, Memorial University, St. John's NL A1B 3V6; fax 709 777-6746; dean@med.mun.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.Pong RW, Pitblado JR. Geographic distribution of physicians in Canada: beyond how many and where. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2006.

- 2.United States General Accounting Office. Physician workforce: physician supply increased in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas but geographic disparities persisted.” Washington: US General Accounting Office; 2003. Available: www.gao.gov/cgi-bin/getrpt?GAO-04-124 (accessed 2007 Nov 14).

- 3.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Medical labour force: 2004. Canberra: The Institute; 2006. Available: www.aihw.gov.au/publications/hwl/mlf04/mlf04.pdf (accessed 2007 Nov 14).

- 4.Incitti F, Rourke J, Rourke L, et al. Rural women family physicians: Are they unique? Can Fam Physician 2003;49:320-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Bundred PE, Levitt C. Medical migration: Who are the real losers? Lancet 2000;356:245-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Rourke JT, Incitti F, Rourke LL, et al. Keeping family physicians in rural practice: solutions favoured by rural physicians and family medicine residents. Can Fam Physician 2003;49:1142-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Rourke JTB. Politics of rural health care: Recruitment and retention of physicians. CMAJ 1993;148:1281-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Canadian Medical Association. Report of the Advisory Panel on the Provision of Medical Services in under serviced Regions. Ottawa: The Association; 1992.

- 9.Dhalla IA, Kwong JC, Streiner DL, et al. Characteristics of first-year students in Canadian medical schools. CMAJ 2002;166:1029-35. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Rourke J. Strategies to increase the enrolment of students of rural origin in medical school: recommendations from the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada, Task Force of the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada. CMAJ 2005;172:62-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Dunbabin J, Levitt L. Rural origin and rural medical exposure: their impact on the rural and remote medical workforce in Australia. Rural Remote Health 2003;3:article 212. Available: www.rrh.org.au/articles/subviewnew.asp?ArticleID=212 (accessed 2007 Nov 14). [PubMed]

- 12.Curran V, Rourke J. The role of medical education in the recruitment and retention of rural physicians. Med Teach 2004;26:265-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Rourke JT, Incitti F, Rourke LL, et al. Relationship between practice location of Ontario family physicians and their rural background or amount of rural medical education experience. Can J Rural Med 2005;10:231-40. [PubMed]

- 14.Hill D, Martin I, Farry P. What would attract general practice trainees into rural practice in New Zealand? N Z Med J 2002;115:U161. [PubMed]

- 15.Sempowski IP. Effectiveness of financial incentives in exchange for rural and under serviced area return-of-service commitments: systematic review of the literature. Can J Rural Med 2004;9:82-8. [PubMed]

- 16.Pathman DE, Konrad TR, Ricketts TC III. The comparative retention of National Health Service Corps and other rural physicians. JAMA 1992;268:1552-8. [PubMed]

- 17.Pathman DE, Konrad TR, King TS, et al. Outcomes of states' scholarship, loan repayment and related programs for physicians. Med Care 2004;42:560-8. [DOI] [PubMed]