Abstract

Induction of neonatal T cell tolerance to soluble antigens requires the use of incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA). The side effects that could be associated with IFA and the ill-defined mechanism underlying neonatal tolerance are setbacks for this otherwise attractive strategy for prevention of T cell–mediated autoimmune diseases. Presumably, IFA contributes a slow antigen release and induction of cytokines influential in T cell differentiation. Immunoglobulins (Igs) have long half-lives and could induce cytokine secretion by binding to Fc receptors on target cells. Our hypothesis was that peptide delivery by Igs may circumvent the use of IFA and induce neonatal tolerance that could confer resistance to autoimmunity. To address this issue we used the proteolipid protein (PLP) sequence 139–151 (hereafter referred to as PLP1), which is encephalitogenic and induces experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in SJL/J mice. PLP1 was expressed on an Ig, and the resulting Ig–PLP1 chimera when injected in saline into newborn mice confers resistance to EAE induction later in life. Mice injected with Ig–PLP1 at birth and challenged as adults with PLP1 developed T cell proliferation in the lymph node but not in the spleen, whereas control mice injected with Ig–W, the parental Ig not including PLP1, developed T cell responses in both lymphoid organs. The lymph node T cells from Ig–PLP1 recipient mice were deviated and produced interleukin (IL)-4 instead of IL-2, whereas the spleen cells, although nonproliferative, produced IL-2 but not interferon (IFN)-γ. Exogenous IFN-γ, as well as IL-12, restored splenic proliferation in an antigen specific manner. IL-12–rescued T cells continued to secrete IL-2 and regained the ability to produce IFN-γ. In vivo, administration of anti–IL-4 antibody or IL-12 restored disease severity. Therefore, adjuvant-free induced neonatal tolerance prevents autoimmunity by an organ-specific regulation of T cells that involves both immune deviation and a new form of cytokine- dependent T cell anergy.

Keywords: neonatal tolerance, deviation, anergy, autoimmunity, antigen delivery

Nearly half a century ago, it was shown that mice injected at birth with splenic cells from an allogeneic donor were later able to accept grafts from the same donor (1). Ever since, the neonatal period has been considered a critical window during which an initial contact with antigen will instruct the immune system to ignore such an antigen and not respond to it during a subsequent encounter.

Soon after the discovery that T cells recognize rather short antigenic fragments, tolerization regimens using peptides in IFA were defined that induced clonal unresponsiveness and mediated neonatal tolerance (2, 3). However, recent developments indicated that antigen injection during the neonatal stage can immunize rather than suppress (4, 5). In allogeneic systems it was discovered that graft acceptance by neonatally tolerized animals was due to the development of functionally deviated T cells producing Th2-type cytokines instead of the usual Th1 cytokines produced by T cells of nontolerized mice (6, 7). These Th2 cells are unable to support development of the cytolytic T lymphocytes required for graft rejection (8). Similarly, neonatal in-jection of a self-peptide in IFA, which protected mice from autoimmune disease induction, was found to operate through clonal unresponsiveness in the lymph nodes accompanied by induction of deviated Th2 cells in the spleen (9). The notion that neonatal injection of antigen can immunize is now well accepted, and evidence has accumulated indicating that factors such as the type of APCs (5, 10), the adjuvant into which the antigen is emulsified (9), the dose of antigen (11), and the availability of antigen in vivo (12) could engender various outcomes ranging from inactivation of T cells to the priming of an immune response. Therefore, in the face of this susceptibility to regulation, it is important to further investigate the outcome of neonatal antigen injection, particularly to self-antigens, since neonatal tolerance could provide a potential strategy for prevention of autoimmunity.

IFA, which has been required for tolerance induction by soluble proteins and peptides, may exert adjuvanticity by contributing a slow release of antigen and inducing cytokine production by APCs (13). However, the use of IFA may generate side effects and trigger oil-induced arthritis (14).

Igs are autologous molecules permissive for peptide expression and can function as a delivery system for T cell epitopes (15–18). Internalization of Igs into APCs via FcRs grants the incorporated peptide access to newly synthesized MHC class II molecules, leading to efficient peptide presentation and T cell activation (19). For instance, when the proteolipid protein (PLP)1 139–151 peptide sequence (hereafter referred to PLP1) was expressed on an Ig molecule, the peptide's presentation was increased by 100-fold (20). Furthermore, the Ig–PLP1 chimera was a potent inducer of PLP1-specific T cell responses both in the spleen and lymph nodes (20, 21). Since Igs are long-lived molecules in vivo, presentation could persist for a long period of time. In addition by binding FcR on APCs, Igs can trigger production of cytokines (22, 23). These functions may provide the Ig delivery system with adjuvant-like properties that could circumvent the use of IFA for tolerance induction and prevention of autoimmunity. Here, we report that Ig–PLP1 injected into newborn mice in saline confers resistance to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) induction by a novel mechanism defined by IL-4 driven lymph node deviation and an unusual IFN-γ–mediated splenic proliferative unresponsiveness.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

6–8-wk-old SJL/J mice (H-2s) were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Frederick, MD) and maintained in our animal facility for the duration of experiments. For the generation of newborn mice, breeding sets of one adult male and three females, were caged together, and when pregnancy was visible the females were separated and caged individually. Offspring were weaned when they reached 3 wk of age. All experimental procedures were carried out according to the guidelines of the institutional animal care committee.

Peptides.

All peptides used in these studies were purchased from Research Genetics, Inc. (Huntsville, AL) and purified by HPLC to >90% purity. PLP1 peptide (HSLGKWLGHPDKF) encompasses an encephalitogenic sequence corresponding to amino acid residues 139–151 of PLP (24, 25). PLP1 peptide is presented to T cells in association with I-As MHC class II molecules. PLP2 peptide (NTWTTCQSIAFPSK) encompasses an encephalitogenic sequence corresponding to amino acid residues 178–191 of PLP (26). This peptide is also presented by I-As MHC class II molecules and induces EAE in SJL/J mice.

Ig–PLP Chimeras.

Expression of PLP1 peptide on Ig–PLP1 has been described previously (20). Ig–W, the parental Ig not encompassing PLP1 peptide, has been described elsewhere (27). The genes used to construct these chimeras are those coding for the light and heavy chains of the anti-arsonate antibody, 91A3, and the procedures for deletion of the heavy chain CDR3 region and replacement with nucleotide sequences coding for PLP1 are similar to those described for the generation of Ig–NP (27). Both Ig–W and Ig–PLP1 are from IgG2b κ isotypes, and Ig–PLP1 differs from Ig–W only by encompassing PLP1 peptide. Both chimeras were expressed in the non–Ig-secreting myeloma B cell line SP2/0 (20). Large scale cultures of transfectants were carried out in DMEM media containing 10% iron-enriched calf serum (Intergen, Purchase, NY). The Ig chimeras were purified from culture supernatant on columns made of rat anti–mouse κ chain coupled to CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). To avoid cross contamination separate columns were used to purify the chimeras.

Neonatal Injections and Adult Immunizations.

Neonatal injections of Ig chimeras were done intraperitoneally in 50–100 μl saline. When the mice reached 7 wk of age they were subjected to immunization with peptide in CFA or to EAE induction. Immunization of adult mice with peptide in CFA was carried out subcutaneously in the foot pads and at the base of the limbs and tail. The peptide was emulsified in a 200 μl PBS/CFA (vol/vol) mixture. 10 d later the mice were killed by cervical dislocation, and the spleens and lymph nodes (axillary, inguinal, popliteal, and sacral) were removed for analysis of proliferative and cytokine responses.

Induction of EAE.

EAE was induced by subcutaneous injection in the foot pads and at the base of the limbs with a 200 μl IFA/PBS (vol/vol) solution containing 100 μg free PLP1 peptide and 200 μg Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra. 6 h later 5 × 109 inactivated Bordetella pertussis were given intravenously. After 48 h, another 5 × 109 inactivated B. pertussis were given to the mice. Mice were scored daily for clinical signs as follows: 0, no clinical signs; 1, loss of tail tone; 2, hindlimb weakness; 3, hindlimb paralysis; 4, forelimb paralysis; and 5, moribund or death.

Assay of Neonatal Splenic and Thymic Cells for Ig–PLP1 Presentation.

Newborn mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μg Ig–PLP1 or Ig–W in 100 μl saline. 2 d later the spleen and thymus were removed, and single cell suspensions were prepared, irradiated (3000 rads), and assayed for stimulation of the PLP1-specific T cell hybridoma 4E3 (28) without addition of exogenous peptide. In brief, graded numbers of splenic or thymic cells were incubated with 5 × 104 4E3 cells, and after 24 h the supernatant was removed and IL-2 production, used as a measure of T cell activation, was determined. [3H]Thymidine incorporation upon incubation of the supernatant with the IL-2–dependent HT-2 cell line was used for detection of IL-2 as described previously (20).

Lymph Node and Spleen T Cell Proliferation.

Lymph node and spleen cells were incubated in 96-well flat-bottomed plates at 4 × 105 and 10 × 105 cells/100 μl per well, respectively, with 100 μl of stimulator for 3 d. Subsequently, 1 μCi [3H]thymidine was added per well, and the culture was continued for an additional 14.5 h. The cells were then harvested on glass fiber filters and incorporated [3H]thymidine was counted using the trace 96 program and an Inotech β counter (Wohlen, Switzerland). The stimulators were used at the following concentrations: PLP1 and PLP2 at 15 μg/ml. A control media with no stimulator was included for each mouse and used as background.

Assays for Restoration of Splenic T Cell Proliferation with Exogenous Cytokines.

Spleen cells from mice that were injected at birth with Ig–PLP1 and immunized as adults with PLP1 in CFA were incubated in 96-well flat-bottomed plates at 10 × 105 cells/100 μl per well with 100 μl media containing the stimulator peptide and the exogenous cytokine (IFN-γ or IL-12) for 3 d. Subsequently, 1 μCi [3H]thymidine was added per well, and the assay was continued as above.

Cytokine restoration of splenic T cell proliferation was also carried out in the presence of anti-CD4, anti-I-As, or isotype-matched mAb. The rat IgG2b anti-CD4 mAb, GK1.5, was used at 5 μg/ml and the mouse IgG2b anti–I-Ak,r,f,s mAb, 10-2.16, was used at 100 μg/ml. Both hybridomas were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD) and antibodies were affinity chromatography purified from culture supernatant on antiisotypic antibodies coupled to Sepharose.

Measurement of Cytokines by ELISA.

Spleen cells were incubated in 96-well round-bottomed plates at 10 × 105 cells/100 μl per well with 100 μl of stimulator for 24 h. Cytokine production was measured by ELISA according to PharMingen's instructions (San Diego, CA) using 100 μl of culture supernatant. Capture antibodies were rat anti–mouse IL-2, JES6-1A12; rat anti–mouse IL-4, 11B11; rat anti–mouse IFN-γ, R4-6A2; and rat anti–mouse IL-10, JES5-2A5. Biotinylated anticytokine antibodies were rat anti–mouse IL-2, JES6-5H4; rat anti–mouse IL-4, BVD6-24G2; rat anti–mouse IFN-γ, XMG1.2; and rat anti–mouse IL-10, JES5-16E3. All cytokines and anticytokine antibodies used in these studies were purchased from PharMingen. The OD405 was measured on a SpectraMAX 340 counter (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) using SoftMAX PRO version 1.2.0 software. Graded amounts of recombinant mouse IL-2, IL-4, IFN-γ, and IL-10 were included in all experiments in order to construct standard curves. The concentration of cytokines in culture supernatants was estimated by extrapolation from the linear portion of the standard curve.

Measurement of Cytokines by ELISPOT Assay.

ELISPOT assay was used to measure cytokines produced by lymph node T cells during antigen stimulation as previously described (9). HA-multiscreen plates (Millipore, Bedford, MA) were coated with 100 μl/well 1 M NaHCO3 buffer containing 2 μg/ml capture antibody. After an overnight incubation at 4°C the plates were washed three times with sterile PBS and free sites were saturated with DMEM culture media containing 10% fetal calf serum for 2 h at 37°C. Subsequently, the blocking media was removed and 5 × 105 lymph node cells/100 μl per well were added along with 100 μl of antigen and incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a 7% CO2 humidified chamber. The plates were then washed and 100 μl of biotinylated anticytokine antibody (1 μg/ml) was added. The anticytokine antibody pairs used here were those described for the ELISA technique. After overnight incubation at 4°C the plates were washed and 100 μl of avidin-peroxidase (2.5 μg/ml) was added. The plates were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Subsequently, spots were visualized by adding 100 μl of substrate (3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole, from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) in 50 mM acetate buffer, pH 5.0, and counted under a dissecting microscope.

Results

Neonatal Injection of Ig–PLP1 Circumvents the Use of Adjuvant and Confers Resistance to EAE Induction.

The nucleotide sequence coding for PLP1 peptide was genetically inserted into the variable region of an Ig heavy chain gene and the resulting gene chimera was transfected together with the gene encoding the parental light chain into the non–Ig- secreting myeloma B cell line, SP2/0 (20). Selection with the appropriate drugs allowed for the generation of transfectants producing complete Ig molecules with PLP1 peptide embodied within the heavy chain CDR3 region. Affinity chromatography–purified Ig–PLP1 was efficiently presented to PLP1-specific T cell hybridomas (20) and induced in vivo T cell responses in both the lymph nodes and spleen that were of Th1 type and produced both IL-2 and IFN-γ (20, 21).

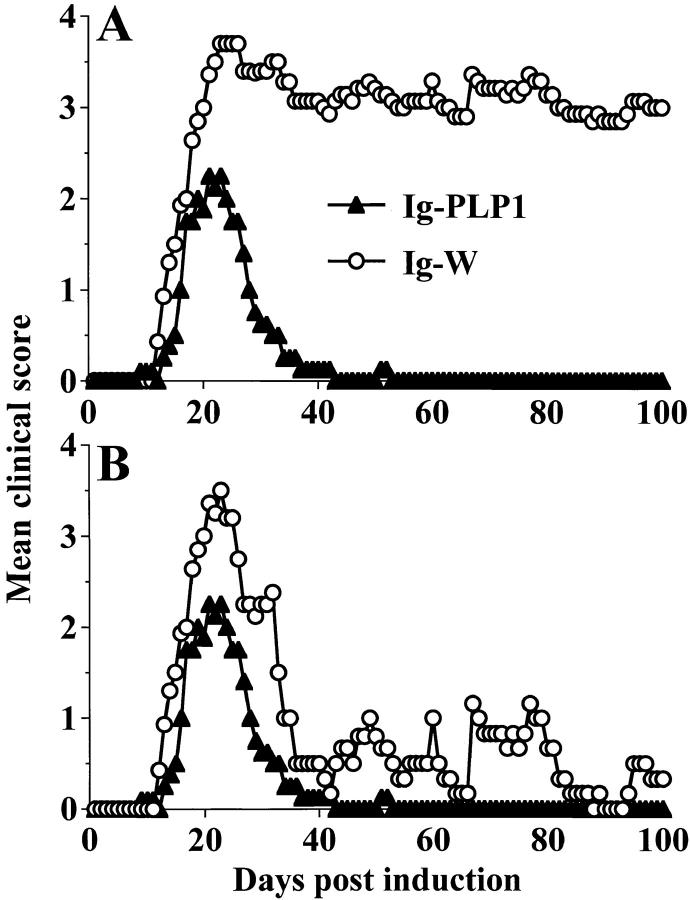

To assay for induction of neonatal tolerance, 1-d-old mice were injected with Ig–PLP1 in saline, and 7 wk later were challenged with a disease-inducing regimen of free PLP1 peptide and scored daily for paralysis. As can be seen in Fig. 1 A, the mice were resistant to induction of paralysis and developed mild monophasic clinical signs of EAE. The mean maximal disease severity was 2.7 ± 0.5 with 0% mortality rate. However, mice that were injected with Ig–W, the parental wild-type Ig not encompassing any PLP peptide (27), developed severe clinical signs of EAE with a 4.2 ± 0.9 mean maximal disease severity accompanied by a 40% mortality. The surviving mice from the group that received Ig–W at birth exhibited a relapsing and remitting disease that persisted to day 100, whereas animals that were injected with Ig–PLP1 did not display any relapses after recovery from the initial mild disease (Fig. 1 B).

Figure 1.

SJL/J mice injected with Ig–PLP1 at birth resist induction of EAE during adult life. Newborn mice (10 per group) were injected with 100 μg of affinity chromatography–purified Ig–PLP1 (▴) or Ig–W (○) in saline within 24 h of birth and were induced for EAE with free PLP1 peptide at 7 wk of age as described in Materials and Methods. Mice were scored daily for signs of paralysis for 100 d. A shows the daily mean clinical score of all mice, and B shows the daily mean score of only the surviving animals. Although all mice in both groups developed signs of paralysis, 40% of the mice that were injected with Ig–W at birth died of severe disease. Death did not occur in mice injected with Ig–PLP1 at birth. The mean maximal disease severity was 4.2 ± 0.9 in the mice recipient of Ig–W at birth and 2.7 ± 0.5 in the Ig–PLP1 group.

Mice Injected at Birth with Ig–PLP1 in Saline and Challenged with PLP1 Peptide in CFA at 7 wk of Age Developed Lymph Node But Not Splenic Proliferative T Cell Responses.

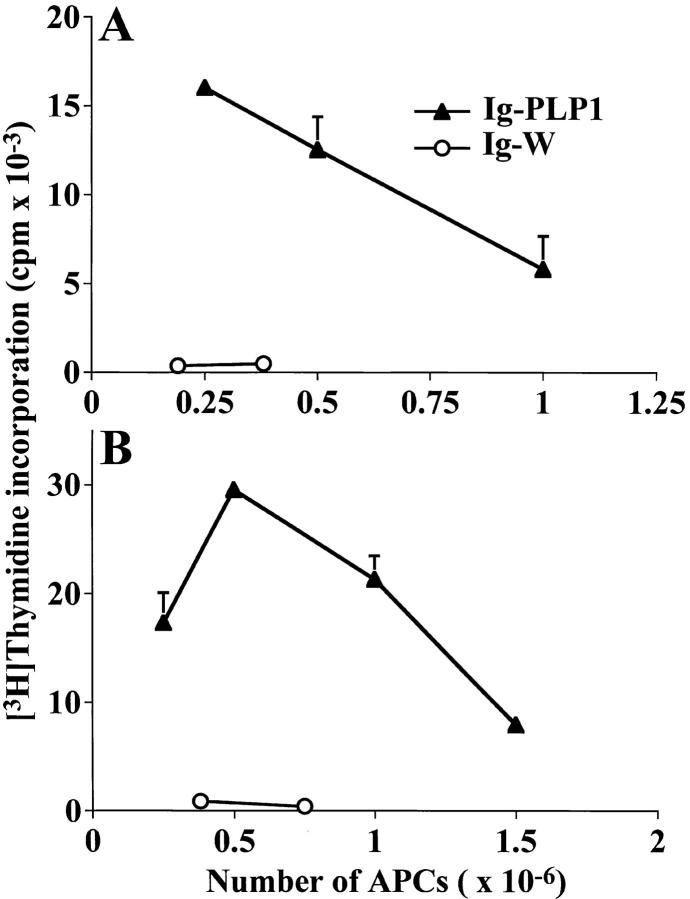

To investigate the mechanism underlying tolerance induction in newborn mice, we first determined if Ig–PLP1 is presented by neonatal APCs in vivo. Mice were injected with Ig– PLP1 at birth, and 2 d later thymic and splenic cells were irradiated and assayed for stimulation of the PLP1-specific T cell hybridoma 4E3 (28) without addition of exogenous antigen. Fig. 2 shows that both thymic and splenic cells from mice that were injected with Ig–PLP1 stimulated the 4E3 hybridoma, whereas cells from mice that received Ig–W instead of Ig–PLP1 did not. These results indicate that Ig–PLP1 was taken up and processed by neonatal APCs and that PLP1–I-As complexes were displayed on the surface of these APCs. Next, we investigated the consequences of such neonatal Ig–PLP1 presentation on the outcome of a later challenge with PLP1 peptide. Newborn mice were injected at birth with either Ig–PLP1 or the control Ig–W, challenged with PLP1 peptide in CFA when they reached 7 wk of age, and then examined for proliferative responses in both lymph node and spleen at day 10 after challenge. The results in Fig. 3 indicate that those animals, that received Ig–PLP1 at birth developed proliferative responses to PLP1 peptide in the lymph node but not the spleen, whereas mice that were injected with Ig–W developed proliferative responses in both lymphoid organs. Neither group responded to the negative control PLP2 peptide, corresponding to amino acid residues 178– 191 of PLP (26). Therefore, exposure to Ig–PLP1 during the neonatal stage affects the response to a challenge with PLP1 peptide and leads to lymph node proliferation and splenic unresponsiveness.

Figure 2.

In vivo presentation of Ig–PLP1 by neonatal thymic and splenic APCs. Newborn mice (three per group) were injected with 100 μg Ig–PLP1 (▴) or Ig–W (○) in saline within 24 h of birth, and in vivo presentation of Ig–PLP1 was allowed for 2 d. The mice were then killed, and pooled thymic (A) and splenic (B) cells were irradiated and used as APCs for stimulation of the PLP1-specific T cell hybridoma 4E3 (28). IL-2 production in the supernatant, which was used as a measure of T cell activation, was determined using the IL-2–dependent HT-2 cell line as described in Materials and Methods. The indicated cpms represent the mean ± SD of triplicates.

Figure 3.

Reduced splenic proliferative T cell response in mice injected with Ig–PLP1 at birth. Newborn mice (eight per group) were injected intraperitoneally within 24 h of birth with 100 μg Ig–PLP1 or Ig–W in saline. When the mice reached 7 wk of age they were immunized with 100 μg free PLP1 peptide in 200 μl CFA/PBS (vol/vol) subcutaneously in the foot pads and at the base of the limbs and tail. 10 d later the mice were killed, and the (A) lymph node (0.4 × 106 cells/well) and (B) splenic (1 × 106 cells/well) cells were in vitro stimulated for 4 d with 15 μg/ml of free PLP1 or PLP2, a negative control peptide corresponding to the encephalitogenic sequence 178–191 of PLP (26). 1 μCi/well of [3H]thymidine was added during the last 14.5 h of stimulation, and proliferation was measured using an Inotech β-counter and the trace 96 Inotech program. The indicated cpms represent the mean ± SD of triplicate wells for individually tested mice. The mean cpm ± SD of lymph node proliferative response of all Ig–PLP1 and Ig–W recipient mice was 34,812 ± 7,508 and 37,026 ± 10,333, respectively. The mean splenic proliferative response was 3,300 ± 3,400 for the Ig–PLP1 recipient group and 14,892 ± 4,769 for the Ig–W recipient group.

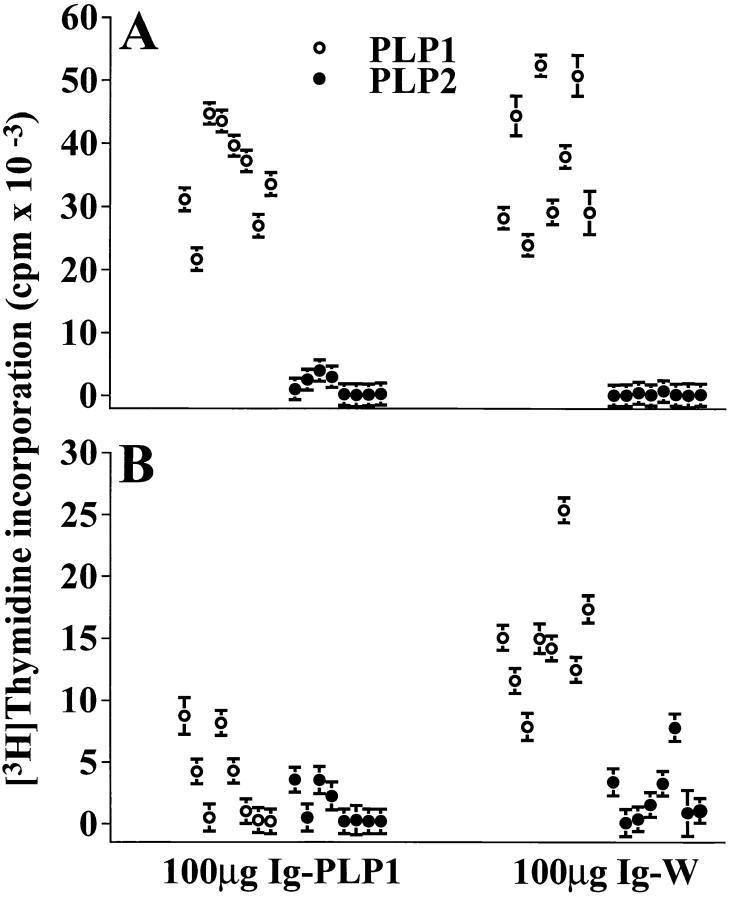

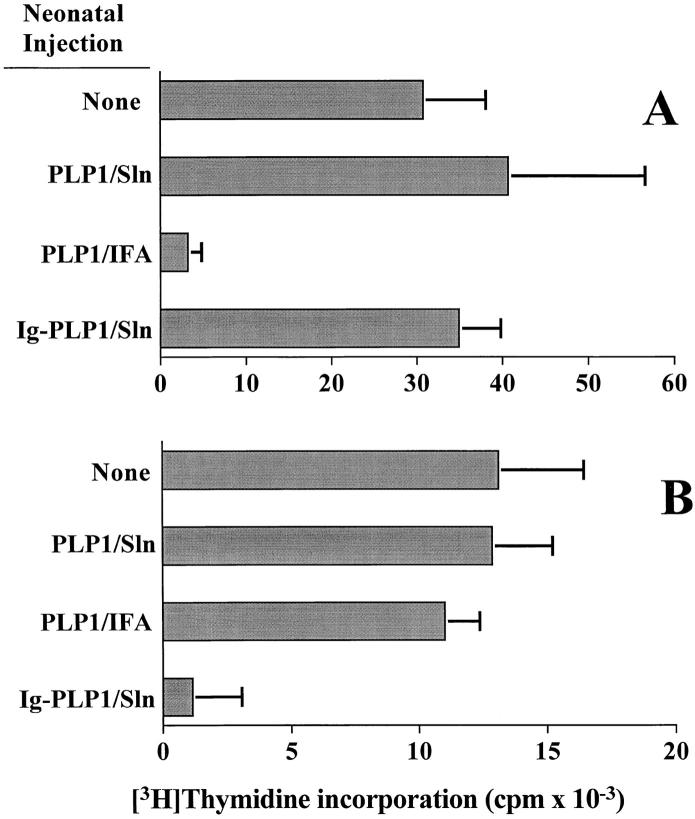

Injection of free PLP1 peptide in saline at birth had no effect on the outcome of a challenge with PLP1 at 7 wk of age. Indeed, when newborn mice were injected with PLP1 peptide in saline and challenged at 7 wk of age with PLP1 in CFA, both the lymph node and spleen developed T cell proliferative responses (Fig. 4). These responses were comparable to those obtained in mice that were not subject to any injection at birth but were immunized with PLP1 peptide in CFA at 7 wk of age. In contrast, mice injected at birth with free PLP1 peptide emulsified in IFA and challenged with PLP1 peptide in CFA at the age of 7 wk developed T cell proliferation in the spleen but were unresponsive in the lymph node (Fig. 4). The slight reduction in the splenic response in mice recipient of PLP1/IFA at birth versus those injected with PLP1/saline is not statistically significant (unpaired Student's t test analysis, P > 0.1). The results obtained with PLP1/IFA injection are in good agreement with data reported for other peptides (9). Consequently, injection of Ig–PLP1 in saline at birth displays an organ-specific regulation of the T cell that is different from the regulation induced by injection of free peptide in IFA or saline (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Neonatal injection of free PLP1 peptide in saline or IFA has a different effect than Ig–PLP1/saline on the proliferative T cell responses to a challenge with PLP1 in CFA. Three groups of newborn mice (seven mice per group) were injected at birth intraperitoneally with 100 μg PLP1 peptide in 100 μl saline (PLP1/Sln), 100 μg PLP1 peptide in 100 μl PBS/IFA (vol/vol) (PLP1/IFA), and 100 μg Ig–PLP1 in 100 μl saline (Ig–PLP1/Sln), and challenged with 100 μg PLP1 in CFA as in Fig. 3. 10 d later the mice were killed and lymph node (A) and splenic (B) proliferative responses were analyzed by [3H]thymidine incorporation as described in Fig. 3. A control group of mice that was not injected at birth (None) but immunized as adults with PLP1 in CFA was included for comparison purposes. The bars represent the mean cpm ± SD of seven individually tested mice.

Newborn Mice Injected with Ig–PLP1 at Birth Develop a Lymph Node Deviation and an IFN-γ–mediated Splenic Anergy upon Challenge with PLP1 Peptide in CFA During Adult Life.

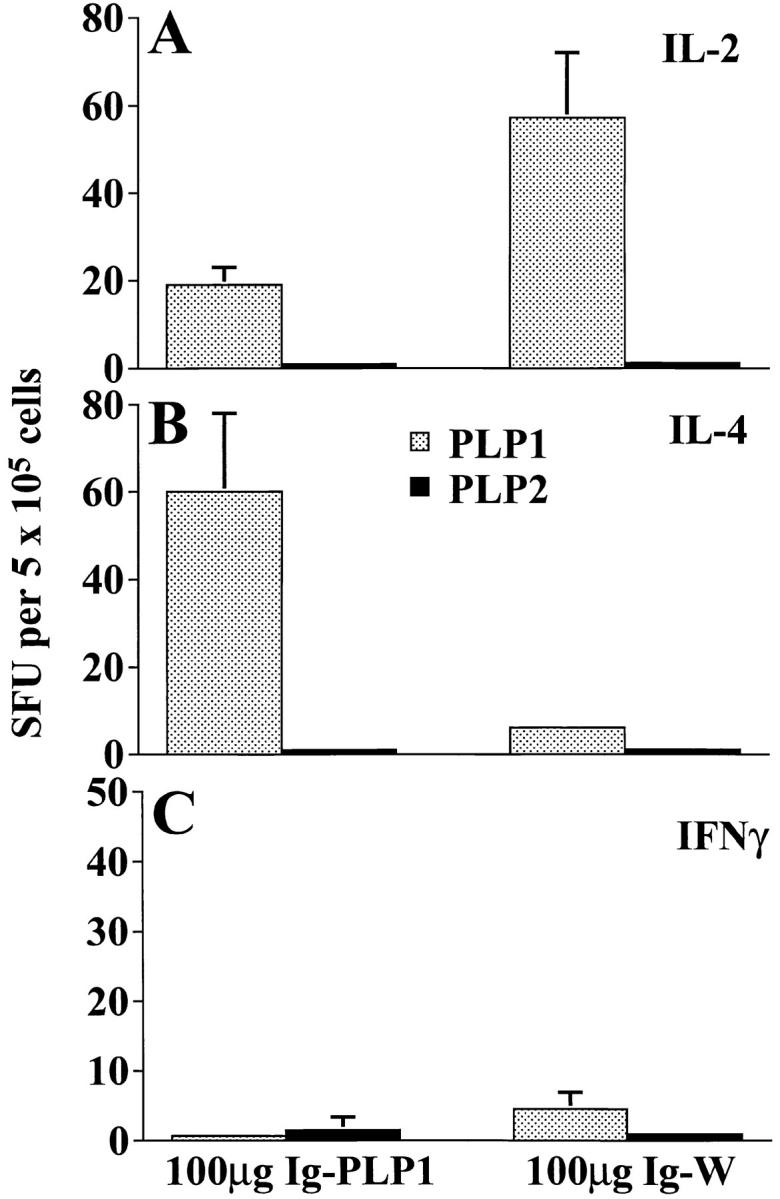

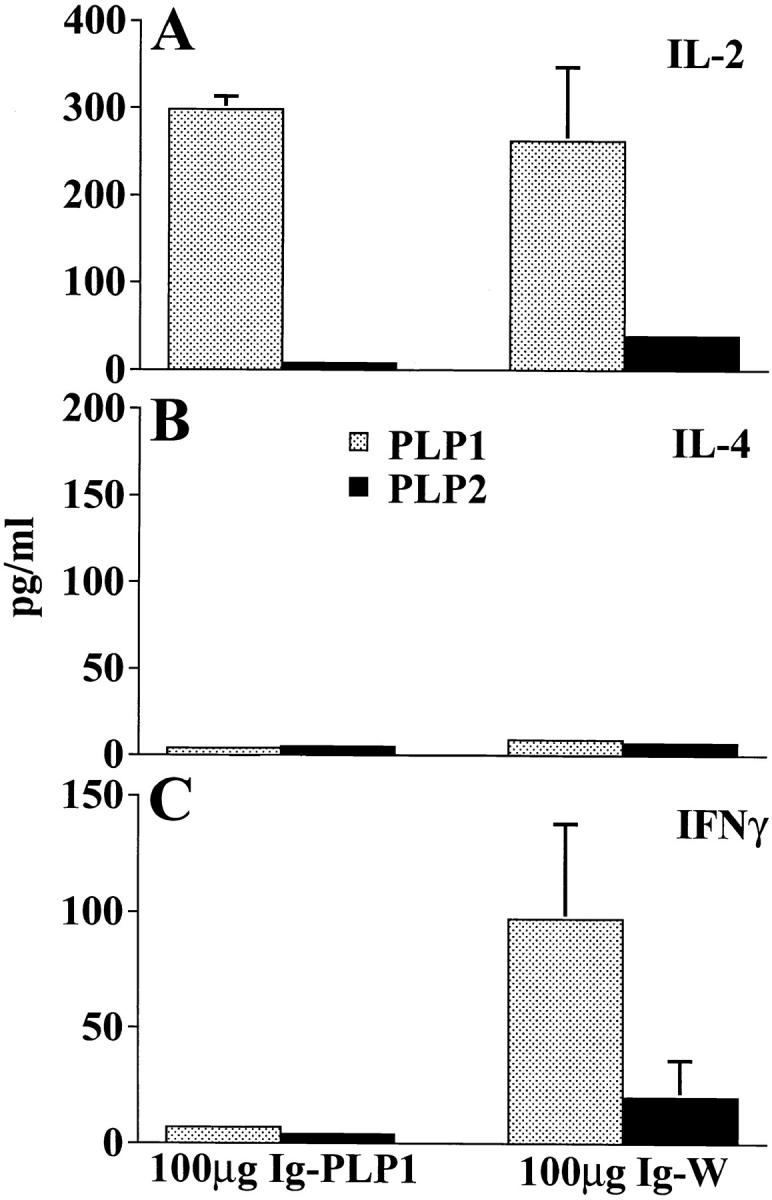

Examination of the cytokine production in the lymph node and spleen of mice injected at birth with Ig– PLP1 and challenged at 7 wk of age with PLP1 peptide in CFA revealed yet another unexpected result. As can be seen in Fig. 5, the lymph node T cells from the Ig–W recipient group produced IL-2 but not IL-4 or IFN-γ, whereas T cells from the Ig–PLP1 recipient group produced IL-4 instead of IL-2. This cytokine production was specific for PLP1 peptide, since PLP2 was unable to stimulate the cells for cytokine production. In the spleen, the Ig–W group produced both IL-2 and IFN-γ upon stimulation with PLP1, whereas cells from the Ig–PLP1 group, although nonproliferative, produced IL-2 and dropped IFN-γ to undetectable levels (Fig. 6). In vitro stimulation with PLP2 peptide had no effect on cytokine production. IL-4 was undetectable with either stimulation in both groups of mice (Fig. 6). IL-10 was undetectable in all groups of mice (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Lymph node T cell deviation in mice recipient of Ig–PLP1 at birth. Newborn mice (eight per group) were injected intraperitoneally within 24 h of birth with 100 μg Ig–PLP1 or Ig–W in saline. When the mice reached 7 wk of age, they were immunized with 100 μg free PLP1 peptide in 200 μl CFA/PBS (vol/vol) subcutaneously in the foot pads and at the base of the limbs and tail. 10 d later the mice were killed, and the lymph node cells (0.4 × 106 cells/well) were in vitro stimulated with free PLP1 or PLP2 (15 μg/ml) for 24 h. The production of IL-2 (A), IL-4 (B), and IFN-γ (C) was measured by ELISPOT as described in the Materials and Methods section using PharMingen anticytokine antibody pairs. The indicated values (spot forming units, SFU) represent the mean ± SD of eight individually tested mice.

Figure 6.

Production of IL-2 but not IFN-γ by nonproliferative splenic T cells from mice injected with Ig–PLP1 on the day of birth. Splenic cells (106 cells/well) from the mice described in Fig. 5 were in vitro stimulated with free PLP1 or PLP2 (15 μg/ml) for 24 h, and the production of IL-2 (A), IL-4 (B), and IFN-γ (C) in the supernatant was measured by ELISA using anticytokine antibody pairs from PharMingen according to the manufacturer's instructions. The indicated amounts of cytokine represent the mean ± SD of eight individually tested mice.

Restoration of Splenic T Cell Proliferation and IFN-γ Production by Exogenous IL-12.

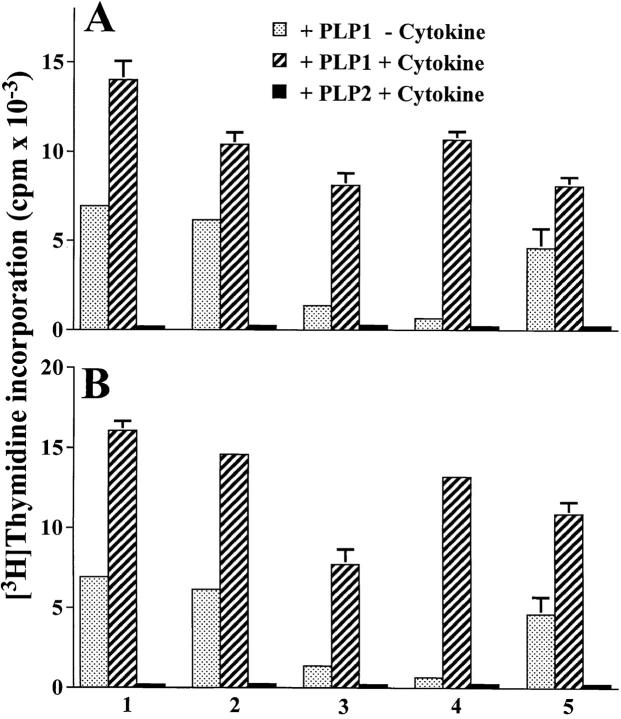

Because the splenic cells from mice that received Ig–PLP1 at birth produced IL-2 but could not proliferate or secrete IFN-γ upon stimulation with PLP1 peptide, we reasoned that the defect in proliferation might be related to the deficiency in IFN-γ. To address this issue, mice that received Ig–PLP1 at birth were challenged with PLP1 peptide in CFA, and the splenic cells were in vitro stimulated with PLP1 peptide in the presence of exogenous IFN-γ or IL-12 (an inducer of IFN-γ) and assayed for proliferation. As can be seen in Fig. 7 A, exogenous IFN-γ restored proliferation of the spleen cells upon stimulation with PLP1 peptide. The restoration of proliferation is antigen specific, since addition of exogenous IFN-γ did not restore proliferation when in vitro stimulation was carried out with PLP2 peptide. Furthermore, IL-12 was also able to restore splenic proliferation (Fig. 7 B). IL-12 restoration of proliferation also proved to be antigen specific and did not develop when in vitro stimulation was carried out with PLP2 peptide. The restoration of T cell proliferation by IL-12 was completely inhibited when the in vitro stimulation was carried out in the presence of 5 μg/ml of the anti-CD4 mAb, GK 1.5, indicating that the proliferating cells are CD4 T cells (data not shown). In addition, the anti–I-As mAb, 10-2.16, inhibited IL-12 restoration of proliferation, indicating the requirement for peptide presentation (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Cytokine-mediated restoration of splenic T cell proliferation in mice injected with Ig–PLP1 at birth. A group of five newborn mice was injected intraperitoneally with 100 μg of Ig–PLP1 and immunized with 100 μg PLP1 peptide in CFA at 7 wk of age, as in Fig. 3. 10 d later, the splenic cells (106 cells/well) were in vitro stimulated with free PLP1 peptide (15 μg/ml) in the presence of 100 U/ml IFN-γ (A) or 10 U/ml IL-12 (B), and [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured as in Fig. 3. Cells from each mouse were stimulated with PLP1 peptide without addition of exogenous cytokines (dotted bars), with PLP1 peptide in the presence of cytokine (hatched bars), or with PLP2 peptide in the presence of cytokine (black bars). The indicated cpms for each mouse represent the mean ± SD of triplicate wells.

Although IFN-γ–restored splenic T cell proliferation did not induce IL-4 production, the production of IL-2 was slightly reduced in comparison to stimulation without cytokine addition (Table 1, IFN-γ). In addition, exogenous IL-12, which restored proliferation but slightly reduced the amount of IL-2, restored production of IFN-γ by the splenic T cells (Table 1, IL-12). Restoration of IFN-γ production was antigen specific because it required stimulation with PLP1 and did not occur when PLP2 was used for stimulation.

Table 1.

Restoration of IFN-γ Production by Stimulation of Splenic Cells from Ig–PLP1 Recipient Mice with PLP1 Peptide in the Presence of Exogenous IL-12*

| Exogenous cytokine | Stimulator peptide | Cytokine production | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | IL-2 | IL-4 | ||||||

| U/ml | pg/ml‡ | |||||||

| IFN-γ | ||||||||

| 0 | PLP1 | ≤16 | 322 ± 80 | ≤16 | ||||

| 1 | PLP1 | ND | 244 ± 74 | 20 ± 17 | ||||

| 10 | PLP1 | ND | 216 ± 60 | ≤16 | ||||

| 10 | PLP2 | ND | ≤16 | ≤16 | ||||

| IL-12 | ||||||||

| 0 | PLP1 | ≤16 | 322 ± 80 | ≤16 | ||||

| 1 | PLP1 | 675 ± 198 | 242 ± 60 | 31 ± 24 | ||||

| 10 | PLP1 | 654 ± 227 | 231 ± 60 | 30 ± 25 | ||||

| 10 | PLP2 | 99 ± 78 | ≤16 | ≤16 | ||||

Six newborn mice were injected with 100 μg Ig–PLP1 in PBS at birth and challenged with 100 μg PLP1 peptide in CFA at the age of 7 wk. 10 d later, the mice were killed and the spleen cells (106 cells/well) were in vitro stimulated with PLP1 or PLP2 peptide (15 μg/ml) in the presence of the indicated concentration of IFN-γ or IL-12. After 24 h of incubation, cytokine production was measured in the supernatant by ELISA as described in Fig. 6.

Mean ± SD of six individually tested mice. Statistical analysis using unpaired Student's t test indicated that the slight reduction in IL-2 production when the cells were stimulated with PLP1 in the presence of cytokines versus stimulation in the absence of cytokines is not significant (P > 0.05 in all groups). It is likely that reactivated proliferative T cells reabsorb some IL-2. ND, not done.

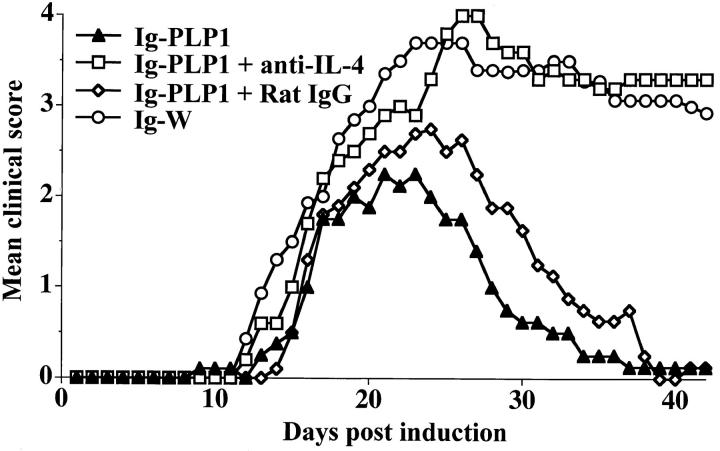

Restoration of Disease Severity in Ig–PLP1-tolerized Mice by Administration of Anti–IL-4 Antibody or rIL-12.

To evaluate the contribution of lymph node IL-4 and splenic anergy to the resistance against disease induction, mice, neonatally tolerized with Ig–PLP1, were subjected to EAE induction while exposed to anti-IL-4 mAb or rIL-12. As can be seen in Fig. 8, administration of 11B11 rat anti–mouse IL-4 mAb restored the severity of EAE to a level comparable to that obtained in the susceptible mice neonatally injected with Ig–W. The control group injected with rat IgG instead of 11B11 mAb, like the Ig–PLP1 neonatally tolerized mice that were not given anti–IL-4 during disease induction, did not restore paralysis. The mice treated with anti– IL-4 mAb had a 4.0 ± 0.9 mean maximal disease severity, a score comparable to the 4.2 ± 0.9 obtained with the Ig–W tolerized mice, whereas those treated with the rat IgG instead of 11B11 mAb had a mean severity of 2.7 ± 0.2, which is comparable to the 2.7 ± 0.5 of the mice tolerized with Ig–PLP1 but not treated with anti–IL-4. The rate of mortality was 40% in the anti–IL-4 treated mice and 0% in those treated with the rat IgG. Overall, in vivo neutralization of IL-4 restores severe EAE.

Figure 8.

Restoration of EAE in Ig–PLP1 tolerized mice by administration of anti–IL-4 antibody. Newborn mice were injected intraperitoneally within 24 h of birth with 100 μg Ig–PLP1 in saline. When they reached 7 wk of age, a group of seven mice was injected intraperitoneally with 1 mg/mouse of affinity purified 11B11 anti–IL-4 antibody in 500 μl of PBS (□). A second group of five mice was injected with 1 mg/mouse of rat IgG in 500 μl PBS (⋄) to serve as control. On the next day all mice were induced for EAE with PLP1 peptide as described in Fig. 1. 5 d after disease induction, the mice were given a second injection of 1 mg/mouse intraperitoneally of 11B11 or rat IgG. The mice were scored daily for signs of paralysis. For comparison purposes the clinical scores of the mice described in Fig. 1 that were tolerized with Ig–PLP1 (▴) or Ig–W (○) at birth and induced for EAE with PLP1 peptide at 7 wk of age were included.

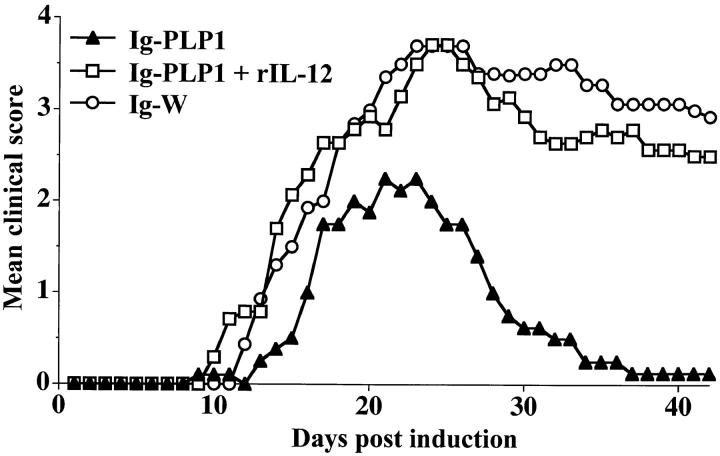

Administration of IL-12 also restores disease severity in Ig–PLP1 neonatally tolerized mice (Fig. 9). Indeed, mice injected with Ig–PLP1 during the neonatal stage and exposed to rIL-12 during disease induction developed a pattern of paralysis much more severe than mice that did not receive rIL-12. In fact, the severity followed a profile similar to that of the susceptible mice recipient of Ig–W during the neonatal stage. The mean maximal disease severity in these mice was 3.8 ± 0.8 and the rate of mortality was 29%. These values are significantly higher than the 2.7 ± 0.5 mean maximal disease severity and 0% death obtained in mice that were not administered with rIL-12.

Figure 9.

Restoration of EAE in Ig–PLP1-tolerized mice by administration of rIL-12. Newborn mice (seven per group) were injected intraperitoneally within 24 h of birth with 100 μg Ig–PLP1 in saline, and when the mice reached 7 wk of age they were induced for EAE with PLP1 peptide as described in Fig. 1. 4 h after disease induction the mice were injected intraperitoneally with 500 ng/mouse of rIL-12 (PharMingen). Additional intraperitoneal injections of rIL-12 (500 ng/mouse) were carried out on days 2, 4, and 7 after disease induction. These mice (□) were scored daily for signs of paralysis. For comparison purposes, the clinical scores of the mice described in Fig. 1 that were tolerized with Ig–PLP1 (▴) or Ig–W (○) at birth and induced for EAE with PLP1 peptide at 7 wk of age were included.

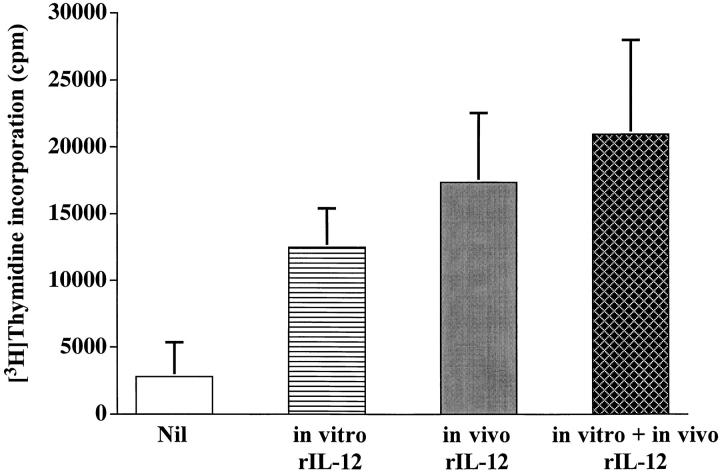

Interestingly, the spleen cells from mice tolerized with Ig–PLP1 at birth and immunized with PLP1 peptide at adult life re-acquired proliferative capabilities when the animals were given rIL-12 during peptide immunization (Fig. 10). Indeed, the splenic T cell proliferative responses in these mice were significantly higher than those obtained in the mice that were not treated with rIL-12. In addition, the proliferation was optimal as it was only slightly higher than the proliferation of cells provided rIL-12 in vitro only and moderately lower than the proliferation of cells exposed to rIL-12 both in vivo and in vitro (Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

Restoration of splenic proliferation in Ig–PLP1 tolerized mice by administration of IL-12. Newborn mice (seven per group) were injected intraperitoneally within 24 h of birth with 100 μg Ig–PLP1 in saline and when the mice reached 7 wk of age they were immunized subcutaneously with 100 μg PLP1 peptide in CFA as described in Fig. 3. 4 h after immunization, the mice were injected intraperitoneally with 500 ng/mouse of rIL-12. Additional intraperitoneal injections of rIL-12 (500 ng/mouse) were carried out on days 2, 4, and 7 after immunization. On day 10 the mice were killed, and the spleen cells (106/well) were stimulated with PLP1 peptide in the presence (cross-hatched bar) or absence (gray bar) of rIL-12 (10 U/well), and proliferation was measured as described in Materials and Methods. For comparison purposes, spleen cells from mice that did not receive rIL-12 in vivo were stimulated with PLP1 peptide in the presence (striped bar) or absence (white bar) of rIL-12 (10 U/well). Each bar represents the mean ± SD of seven individually tested mice.

Discussion

Ig–PLP1, an Ig molecule expressing the encephalitogenic sequence 139–151 of PLP, injected in saline into newborn mice was efficiently presented by neonatal thymic and splenic APCs in vivo (Fig. 2). Consequently, the mice showed resistance to EAE induction later in life (Fig. 1). Examination of the T cell responses to PLP1 in mice that received Ig–PLP1 at birth and challenged with PLP1 at 7 wk of age indicated a strong peptide-specific proliferative response in the lymph node but a markedly reduced splenic proliferation (Fig. 3). Control animals injected at birth with Ig–W, the parental Ig not encompassing PLP1 peptide, developed proliferative responses in both lymphoid organs (Fig. 3). In the lymph node there was a cytokine deviation from IL-2, in Ig–W recipient mice, to IL-4 in Ig–PLP1 recipient mice (Fig. 5). In the spleen, the control mice injected with Ig–W at birth produced both IL-2 and IFN-γ, whereas Ig–PLP1 recipient mice, despite the absence of T cell proliferation produced IL-2 but IFN-γ was undetectable (Fig. 6). The nonproliferative splenic T cells were able to recover from this status and proliferated when stimulated with PLP1 peptide in the presence of IFN-γ or IL-12 (Fig. 7). The restoration of proliferation by exogenous cytokines was inhibited by anti-CD4 and anti-MHC class II antibodies indicating that the target cells are CD4-positive T cells requiring peptide presentation for reacquisition of the proliferative status. In addition, these splenic T cells, once recovered, became able to produce IFN-γ (Table 1). In vivo, when the Ig–PLP1 tolerized mice were given anti-IL-4 mAb during disease induction, the severity of EAE was restored (Fig. 8). Similarly administration of rIL-12 during peptide immunization or disease induction restored both splenic proliferation (Fig. 10) and disease severity (Fig. 9). A summary of these results is illustrated in Table 2. The overall conclusion that could be drawn from these data is that the placing of a peptide in the context of an Ig for delivery to the neonatal immune system circumvents the use of IFA to confer resistance to disease induction later in life. Moreover, the results reveal a new mechanism operating neonatal tolerance. As indicated in Table 2, the lymph node T cells were deviated and produced IL-4 instead of IL-2, and the splenic T cells, although nonproliferative, produced IL-2 and regained the ability to proliferate when provided IFN-γ or IL-12. We wish to define this phenomenon as IFN-γ–mediated anergy.

Table 2.

Summary of the Lymph Node and Splenic Responses to PLP1 Peptide in Mice Recipient of Ig–PLP1 or Ig–W at Birth

| Injection at birth | Proliferation | Cytokine production | Response status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Splenic response | ||||||

| Ig–W |

yes | IL-2, IFN-γ | standard | |||

| Ig–PLP1 | no, but can | only IL-2, but | unusual IFN-γ– | |||

| be restored by | IFN-γ production | mediated anergy | ||||

| exogenous IFN-γ | can be restored by | |||||

| or IL-12 in vitro, | exogenous IL-12 in vitro | |||||

| or IL-12 in vivo | ||||||

| Lymph node response | ||||||

| Ig–W |

yes | IL-2 | standard | |||

| Ig–PLP1 | yes | IL-4 | IL-4–driven T cell | |||

| deviation |

T cell deviation has previously been associated with neonatal tolerance in allogeneic (6, 7), viral (11), and peptide/ IFA (9) antigen systems. In the Ig–PLP1 model, there is a unique organ-specific T cell regulation characterized by a deviation in the lymph node and an unusual IFN-γ–mediated anergy in the spleen. In fact, when free PLP1 peptide was injected in saline at birth, the response to challenge with PLP1 in CFA was normal (Fig. 4). Moreover, when free PLP1 peptide was injected into newborn mice in IFA, a challenge with PLP1 in CFA induced significant proliferation in the spleen but the lymph node was unresponsive (Fig. 4). Similar results were reported in an MBP/IFA model, where the proliferative splenic T cells were deviated and produced Th2-type cytokines (9). The lymph node IL-4 may play an important role in the resistance to disease induction. This statement is supported by the observation that neutralization of IL-4 by the administration of anti–IL-4 antibody restores the severity of disease. In addition, an IL-4–mediated bystander effect (29) may have been responsible for the suppression of epitope spreading and related relapses (30, 31) in the Ig–PLP1–tolerized mice.

The second striking observation is that the splenic T cells of mice injected with Ig–PLP1 at birth and challenged with PLP1 peptide as adults could not proliferate (Fig. 3 B) or produce IFN-γ (Fig. 6 C). However, there was production of IL-2 (Fig. 6 A). Moreover, these cells regained the ability to proliferate when supplied with IFN-γ or IL-12, a cytokine defined as an inducer of IFN-γ (Fig. 7; references 32, 33). This phenomenon may qualify for the term anergy, with the distinction that the T cells produce IL-2 but are unable to produce IFN-γ. Therefore, we propose the term IFN-γ–mediated anergy to differentiate it from standard T cell anergy (34). The fact that the T cells produce IFN-γ when they regain proliferative capacity upon supply of IL-12 further justifies the involvement of IFN-γ in this form of unresponsiveness. Moreover, since administration of rIL-12 was able to restore both in vivo splenic T cell proliferation and disease severity, it maybe that bystander reactivation of these cells is responsible for the residual EAE observed in Ig–PLP1 tolerized mice. Also, the question as to the factors involved in the initiation and perpetuation of these altered cellular responses mediating resistance to disease induction remains unanswered. On a speculative basis, it could be reasoned that neonatal presentation of Ig–PLP1 involves specific APCs that strongly attach Ig–PLP1 and coordinately regulate expression of costimulatory molecules and/or cytokine production. Under these circumstances, the T cell–APC interactions and the local cytokine environment could be affected, leading to the generation of T cells for which differentiation is still susceptible to regulation. During challenge with antigen these cells would be subject to organ-specific regulation. Alternatively, neonatal presentation of Ig–PLP1 could be generating T cells deficient in IFN-γ production. During antigen challenge those restimulated in regional lymph nodes would be subject to the effects of CFA and possibly default to the Th2 pathway, whereas those restimulated systemically remain dependent on IFN-γ for proliferation and differentiation.

The deficiency in IFN-γ and the dependency of splenic T cell proliferation on such a cytokine constitute another puzzle in these observations. IL-12, a key cytokine for the differentiation of T cells into effector Th1 cells (35, 36) restored proliferation and IFN-γ production by splenic T cells (Fig. 7 B and Table 1). It could be possible that the splenic T cells, although producing the growth factor IL-2, are defective in the biochemical signals required for differentiation and consequent IFN-γ production.

Overall, neonatal injection of antigen, generally thought of as a strategy for induction of unresponsiveness appears to function for immunization in this Ig–peptide model as well as in other systems (4, 5, 9). In addition, since immune deviation provides the possibility for bystander T cell downregulation (29, 37), the Ig–peptide strategy may evolve as a means of vaccination without the need for adjuvant against autoimmune diseases involving multiple antigens.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jacque Caprio for technical support.

This work was supported by grant RG2778A1/1 (to H. Zaghouani) from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and by a grant (to H. Zaghouani) from Astral, Inc., a subsidiary of Alliance Pharmaceutical Corp. (San Diego, CA).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- PLP

proteolipid protein

References

- 1.Billingham RE, Brent L, Medawar BP. Quantitative studies of tissue transplantation immunity. III. Acutely acquired tolerance. Proc R Soc Lond Biol Sci. 1956;239:44–57. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gammon G, Dunn K, Shastri N, Oki A, Wilbur S, Sercarz EE. Neonatal T cell tolerance to minimal immunogenic peptides is caused by clonal inactivation. Nature. 1986;319:413–415. doi: 10.1038/319413a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clayton JP, Gammon GM, Ando DG, Kono DH, Hood L, Sercarz EE. Peptide-specific prevention of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis: neonatal tolerance induced to the dominant T cell determinant of myelin basic protein. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1681–1691. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.5.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh RR, Hahn BH, Sercarz EE. Neonatal peptide exposure can prime T cells and upon subsequent immunization, induce their immune deviation: implications for antibody vs. T cell–mediated autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1613–1621. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ridge JP, Fuchs EJ, Matzinger P. Neonatal tolerance revisited: turning on newborn T cells with dendritic cells. Science. 1996;271:1723–1726. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powell TJ, Streilein W. Neonatal tolerance induction by class II alloantigens activates IL-4-secreting, tolerogen-responsive T cells. J Immunol. 1990;144:854–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen N, Field EH. Enhanced type 2 and diminished type 1 cytokines in neonatal tolerance. Transplantation. 1995;59:933–941. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199504150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao Q, Chen N, Rouse TM, Field EH. The role of IL-4 in the induction phase of allogeneic neonatal tolerance. Transplantation. 1996;62:1847–1854. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199612270-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forsthuber T, Yip HC, Lehmann P. Induction of TH1 and TH2 immunity in neonatal mice. Science. 1996;271:1728–1730. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuchs EJ, Matzinger P. B cells turn off virgin but not memory T cells. Science. 1992;258:1156–1159. doi: 10.1126/science.1439825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarzotti M, Robbins DS, Hoffman PM. Induction of protective CTL responses in newborn mice by a murine retrovirus. Science. 1996;271:1726–1728. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garza KM, Griggs ND, Tung KSK. Neonatal injection of an ovarian peptide induces autoimmune ovarian disease in female mice: requirement of endogenous neonatal ovaries. Immunity. 1996;6:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Victoratos P, Yiangou M, Avramidis N, Hadjipetrou L. Regulation of cytokine gene expression by adjuvants in vivo. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;109:569–578. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4631361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Svelander L, Mussener A, Erlandsson-Harris H, Kleinau S. Polyclonal Th1 cells transfer oil-induced arthritis. Immunology. 1997;91:260–265. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zanetti M, Rossi F, Lanza P, Filaci G, Lee RH, Billetta R. Theoretical and practical aspects of antigenized antibodies. Immunol Rev. 1992;130:125–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1992.tb01524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaghouani H, Kuzu Y, Kuzu H, Brumeanu T-D, Swiggard WJ, Steinman RM, Bona CA. Contrasting efficacy of presentation by major histocompatibility complex class I and class II products when peptides are administered within a common protein carrier, self immunoglobulin. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2746–2750. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaghouani H, Steinman R, Nonacs R, Shah H, Gerhard W, Bona C. Presentation of a viral T cell epitope expressed in the CDR3 region of a self immunoglobulin molecule. Science. 1993;259:224–227. doi: 10.1126/science.7678469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zambidis ET, Scott DW. Epitope-specific tolerance induction with an engineered immunoglobulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5019–5024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.5019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brumeanu TD, Swiggard WJ, Steinman RM, Bona C, Zaghouani H. Efficient loading of identical viral peptide onto class II molecules by antigenized immunoglobulin and influenza virus. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1795–1799. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Legge KL, Min B, Potter NT, Zaghouani H. Presentation of a T cell receptor antagonist by immunoglobulin ablates activation of T cells by a synthetic peptide or proteins requiring endocytic processing. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1043–1053. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.6.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Legge KL, Min B, Cestra AE, Pack CD, Zaghouani H. T cell receptor agonist and antagonist exert in vivo cross-regulation on one another when presented on immunoglobulins. J Immunol. 1998;161:106–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van de Winkel JGJ, Capel PJA. Human IgG Fc receptor heterogeneity: molecular aspects and clinical implications. Immunol Today. 1993;14:215–221. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90166-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krutmann J, Kirnbauer R, Kock A, Schwarz T, Schopf E, May LT, Sehgal PB, Luger TA. Cross-linking Fc receptors on monocytes triggers IL-6 production. Role in anti-CD3-induced T cell activation. J Immunol. 1990;145:1337–1342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuohy VK, Lu Z, Sobel RA, Laursen RA, Lees MB. Identification of an encephalitogenic determinant of myelin proteolipid protein for SJL mice. J Immunol. 1989;142:1523–1527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McRae BL, Kennedy MK, Tan LJ, Dal MC, Canto, Picha KS, Miller SD. Induction of active and adoptive relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) using an encephalitogenic epitope of proteolipid protein. J Neuroimmunol. 1992;38:229–240. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(92)90016-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greer JM, Kuchroo VK, Sobel RA, Lees MB. Identification and characterization of a second encephalitogenic determinant of myelin proteolipid protein (residues 178–191) for SJL mice. J Immunol. 1992;149:783–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaghouani H, Krystal M, Kuzu H, Moran T, Shah H, Kuzu Y, Schulman J, Bona C. Cells expressing an H chain Ig gene carrying a viral T cell epitope are lysed by specific cytolytic T cells. J Immunol. 1992;148:3604–3609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuchroo VK, Greer JM, Kaul D, Ishioka G, Franco A, Sette A, Sobel RA, Lees MMB. A single TCR antagonist peptide inhibits experimental allergic encephalomyelitis mediated by a diverse T cell repertoire. J Immunol. 1994;153:3326–3336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicholson LB, Murtaza A, Hafler BP, Sette A, Kuchroo VK. A T cell receptor antagonist peptide induces T cells that mediate bystander suppression and prevent autoimmune encephalomyelitis induced with multiple myelin antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9279–9284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller SD, Vanderlugt CL, Lenschow DJ, Pope JG, Karandikar NJ, Dal MC, Canto, Bluestone JA. Blockade of CD28/B7-1 interaction prevents epitope spreading and clinical relapses of murine EAE. Immunity. 1995;3:739–745. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu M, Johnson JM, Tuohy VK. A predictable sequential determinant spreading cascade invariably accompanies progression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: a basis for peptide-specific therapy after onset of clinical disease. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1777–1788. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan SH, Perussia B, Gupta JW, Kobayashi M, Pospisil M, Young HA, Wolf SF, Young D, Clark SC, Trinchieri G. Induction of interferon-γ production by natural killer cell stimulatory factor: characterization of the responder cells and synergy with other inducer. J Exp Med. 1991;173:869–879. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manetti R, Parronchi P, Giudizi MG, Piccinni MP, Maggi E, Trinchieri G, Romagnani S. Natural killer cell stimulatory factor (Interleukin 12 [IL-12]) induces T helper type 1 (Th1)-specific immune responses and inhibits the development of IL-4–producing Th cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1199–1204. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jenkins MK, Pardoll DM, Mizuguchi J, Quill H, Schwartz RH. T cell responsiveness in vivo and in vitro: fine specificity of induction and molecular characterization of the unresponsive state. Immunol Rev. 1987;95:113–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1987.tb00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parijs LV, Perez VL, Biuckians A, Maki RG, London CA, Abbas AK. Role of IL-12 and costimulators in T cell anergy in vivo. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1119–1128. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 36.Szabo SJ, Dighe AS, Gubler U, Murphy KM. Regulation of the interleukin (IL)-12R b2 subunit expression in developing T helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:817–824. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Falcone M, Bloom BR. A T helper cell (Th2) immune response against non-self antigens modifies the cytokine profile of autoimmune T cells and protects against experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 1997;185:901–907. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]