Abstract

The majority of individuals chronically exposed to tobacco smoke will eventually succumb to cardiovascular disease (CVD). However, despite the major cardiovascular health implications of tobacco smoke exposure, concepts of how such exposure specifically results in cardiovascular cell dysfunction that leads to CVD development are still being explored. Moreover, surprisingly little is known about the effects of prenatal and childhood tobacco smoke exposure on adult CVD development. Herein, it is proposed that the mitochondrion is a central target for environmental oxidants, including tobacco smoke. By virtue of its multiple, essential roles in cell function including energy production, oxidant signaling, apoptosis, immune response, and thermogenesis, damage to the mitochondrion will likely play an important role in the development of multiple common forms of human disease, including CVD. Specifically, this review will discuss the potential role of tobacco smoke and environmental oxidant exposure in the induction of mitochondrial damage which is related to CVD development. Furthermore, mechanisms of how mitochondrial damage can initiate and/or contribute to CVD are discussed, as are experimental results that are consistent with the hypothesis that mitochondrial damage and dysfunction will increase CVD susceptibility. Aspects of both adult and developmental (fetal and childhood) exposure to tobacco smoke on mitochondrial damage, function and disease development are also discussed, including the future implications and direction of studies involving the role of the mitochondrion in influencing disease susceptibility mediated by environmental factors.

Keywords: tobacco smoke, mitochondria, cardiovascular disease, mtDNA

1. Introduction

There are an estimated 1.3 billion tobacco smokers worldwide, and it is estimated that this figure will be 1.7 billion by 2025 [1]. The majority of individuals chronically exposed to tobacco smoke in the U.S. will succumb to cardiovascular disease (CVD): of the 500,000 annual CVD related deaths in the US each year, 20% can be directly attributed to tobacco smoke exposure, and 40,000 of these deaths are believed to be related to second-hand tobacco smoke exposure [2;3]. Despite the major cardiovascular health implications of tobacco smoke exposure, concepts of how tobacco smoke exposure specifically results in cardiovascular cell dysfunction leading to CVD development are still being explored; moreover, surprisingly little is known about the effects of prenatal and childhood tobacco smoke exposure on adult CVD development. Herein, it is posited that the mitochondrion is a central target for environmental oxidants, including tobacco smoke, and mitochondrial damage plays an important role in the development of CVD. Consequently, this review will discuss the potential role tobacco smoke and environmental oxidant exposure play in the induction of mitochondrial damage, which is related to CVD development. Initially, basic aspects of CVD development and mitochondrial functions will be introduced, followed by a discussion of environmental oxidant effects (including tobacco smoke) on cardiovascular mitochondrial function and damage in CVD development.

2. Cardiovascular Disease is the Major Cause of Death in the Western World

With the exception of the worldwide Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918, cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in the United States every year since 1900 [3]. Atherosclerosis is the leading cause of CVD-related mortality, accounting for nearly 75% of all deaths from heart disease [2;3]. Atherosclerosis is generally considered to be a form of progressive chronic inflammation resulting from interaction between modified lipoproteins, monocyte-derived macrophages, T cells, and cellular elements of the arterial wall. Numerous reviews have described atherogenesis in detail [4-7]. Because atherosclerosis is thought to be initiated by endothelial cell injury, many studies have investigated the potential sources and causes of endothelial cell dysfunction and damage. Increasing evidence from such studies implicates oxidative stress as a major factor in endothelial injury and the subsequent development and progression of CVD. [8]

3. Cardiovascular Disease Risk and Oxidant Stress

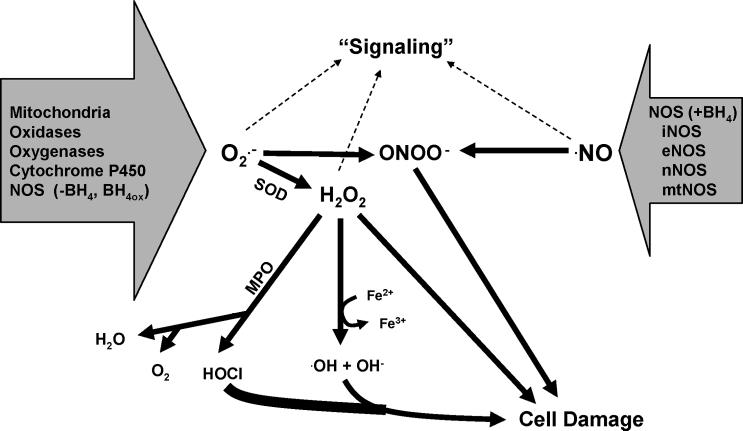

Oxidative stress is caused by reactive species (RS), a collective grouping of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS, respectively) that are capable of disrupting cell function and exerting cytotoxic effects when generated in excess. Superoxide anion radical (O2•−), and nitric oxide (•NO) are the primary or fundamental “building block” RS, in that all other cellular sources of RS can be generated from these two species (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Potential sources of superoxide (O2•−) and nitric oxide (•NO). O2•− is generated from various sources and can enzymatically be converted to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by superoxide dismutase (SOD). H2O2 can act as a signaling molecule, be degraded by myeloperoxidase (MPO) to water and oxygen, also producing hypochlorous acid (HOCl), a potent oxidant and reactant. MPO also reacts with O2•− in reduction reactions that increase HOCl production. In the presence of transition metals (Fe2+), H2O2 can produce hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and hydroxide anion (OH¯) via Fenton Haber-Weiss reaction. Under high concentrations or chronic levels, H2O2 can cause cellular damage. •NO is produced by a variety of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) isoforms (iNOS - inducible NOS; eNOS - endothelial NOS; nNOS - neuronal NOS; mtNOS - mitochondrial NOS), can act as a signaling molecule, or react with O2•− to produce peroxynitrite (ONOO¯), which is capable of mediating a variety of biological effects including cell damage and apoptosis. Under conditions where tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), a required cofactor for NOS, is oxidized or absent (-BH4), NOS can produce O2•−.

A shared feature among the common CVD risk factors, such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, tobacco smoke and age, is increased levels of vascular RS, which can exert cytotoxic effects by modifying essential molecules such as lipids, proteins and DNA. Numerous studies have shown that increased vascular oxidant stress has biological effects, including the peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids in membrane or plasma lipoproteins, direct inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes, inactivation of membrane sodium channels, and DNA damage [5;9-12]. These effects, in turn, perpetuate the continued generation of increased vascular RS, creating a cycle of injury and further RS production.

Whereas many studies have investigated the potential endogenous sources of RS associated with CVD risk factors and disease development, the biological effects of increased vascular oxidative stress on specific cellular processes and organelle function and damage have not been as intensively studied. For example, while it is known that increased oxidative stress originating from a variety of endogenous sources is a common theme among CVD risk factors, [13-21], it is not yet clear whether these factors act to alter cellular function through common mechanisms, or whether there is a common cellular “target” of this oxidant stress.

4. Mitochondria and Cellular Functions

Mitochondria are commonly stereotyped as “cellular power plants”; however, the mitochondrion also plays critical roles in cell regulation, growth, thermogenesis and apoptosis by generating oxidants that are utilized in these processes. Perhaps most significantly, it has been suggested that the balance between energy efficiency, oxidant production, and thermogenesis in the mitochondrion has long term implications for human disease development, susceptibility and evolution [22-24]. Consequently, the mitochondrion is a multifunctional organelle, whose primary function will be dependent upon the current requirements and environment of the cell. Hence, the primary function of a mitochondrion in an endothelial cell may be the regulated generation of oxidants for cell signaling, whereas within a cardiac myocyte it may be the generation of ATP, or a combination of functions (e.g. ATP and oxidant generation). Therefore mitochondrial damage and dysfunction can have multiple cellular effects depending upon the primary functional role(s) of the mitochondrion in that tissue.

4.1 Mitochondrial oxidant production

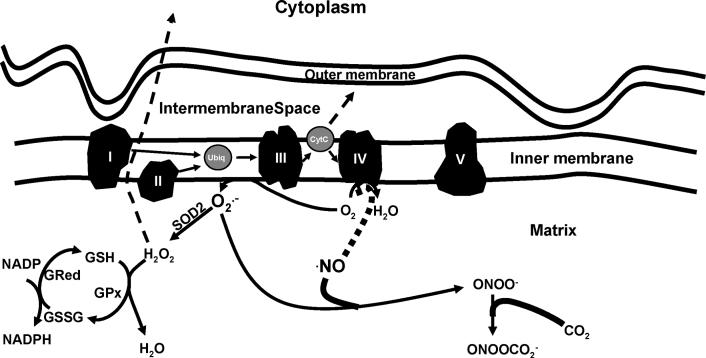

While the majority of oxygen consumed by the mitochondrion is converted to water at complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase), it can also pick up electrons directly from the ubiquinone site in complex III and flavin mononucleotide group of complex I to generate O2•− [25;26] (Figure 2). Mitochondrial generated O2•− can be converted to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2) (Figure 2). Under basal conditions, up to 2% of the mitochondrial oxygen consumption is used to generate H2O2, with concentration fluxes being altered by drugs or toxins such as electron transport inhibitors, uncouplers, redox cycling molecules, or by local (endogenous) and exogenous environmental changes [26-31]. Being freely diffusible, mitochondrial generated H2O2 can act as a signaling molecule,[32-36] be converted to H2O by the glutathione redox system, react with O2•−, or, in the presence of transition metals, yield highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (•OH) [37]. (Figures 1 and 2)

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial oxidant production. Reducing equivalents are provided within the mitochondrial matrix (e.g. metabolism of glucose via glycolysis and the citric acid cycle) to complex I (NADH) and complex II (FADH2). Electrons are shuttled to complex III via ubiquinol. Cytochrome c carries electrons from complex III to complex IV, with the reduction of O2 to form H2O (a reaction inhibited by •NO). Of the electrons entering the transport chain, it has been estimated that 2% - 4% escape the confines of the “chain” to form O2•−. Inhibitors of electron transport (e.g. •NO) can increase mitochondrial oxidant (O2•−) production. •NO can impair electron flow at cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) by oxidizing the heme group of cytochrome aa3, and is competitive with O2. •NO also inhibits the bc1 segment of complex III, resulting in increased auto-oxidation of ubisemiquinone and O2•− production. At low •NO concentrations, the dismutation of O2•− (via SOD2) and formation of H2O2 is favored, which can subsequently diffuse from the mitochondrion and act as a signaling molecule, or, is reduced by GSH to form H2O. At higher •NO concentrations, O2•− reacts with •NO to form ONOO¯, which may promote cytochrome c release and apoptosis, inhibit electron transport, and inactivate mitochondrial proteins (e.g. aconitase and SOD2). In the presence of CO2, ONOO¯ yields nitrosoperoxycarbonate (ONOOCO2¯), which has been proposed to diminish oxidation and increase nitration reactions. Hence, modulation of mitochondrial ROS/RNS concentrations influences organellar function, damage, and apoptosis.

One of the more studied effects of O2•− is its diffusion limited reaction with nitric oxide (•NO) (109 M-1 sec-1) [38] to form peroxynitrite (ONOO¯), a molecule that has been implicated in the initiation of a number of deleterious biological effects including DNA damage, enzyme inactivation, lipid peroxidation reactions (oxidative degradation of phospholipids, cholesterol) and the modification (oxidation or nitration) of biomolecules [39-42]. In the mitochondrion, it is likely that ONOO¯ reacts with CO2 (the principle site of CO2 is the mitochondrion) to form a nitrosoperoxycarbonate intermediate (ONOOCO2¯). ONOOCO2¯ has been shown to efficiently mediate nitration reactions, thus diminishing oxidation yields [43]. ONOOCO2¯ homolyzes to form carbonate radical (CO3•−) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), [44] wherein the CO3•− acts as the oxidant to yield the tyrosyl radical and NO2 subsequently adds via radical-radical addition, resulting in the production of nitrotyrosine. Consequently, any factors that increase cellular/mitochondrial CO2 levels may hasten these processes (e.g., inflammation, metabolic dysfunction). Recent studies also suggest that activation of specific oxidases (e.g. NAD(P)H oxidase) thought to be associated with increased CVD risk may influence mitochondrial oxidant production and function [45].

4.2 Mitochondrial oxidant regulation

A number of factors regulate mitochondrial oxidant generation, including local concentrations of both RNS and ROS, mitochondrial antioxidants, electron transport efficiency, metabolic reducing equivalent availability (NADH and FADH2), uncoupling protein (UCP) activities, cytokines, and overall organelle integrity (damage to membranes, DNA, and proteins). Low •NO concentrations can modulate mitochondrial respiration and oxygen consumption through reversible binding at complex IV, whereas higher concentrations of •NO result in increased ONOO¯ formation and can contribute to cytoxicity [46;47]. Inhibition of electron flow at complex IV results in increased mitochondrial O2•− generation [48]. (Figure 2) Chronic exposure to high •NO results in decreased respiratory complexes I, II, and IV activity and protein levels, accompanied by an increase in cellular S-nitrosothiol levels and free iron [49]. Hence, local •NO concentrations within the mitochondrion can play an important role in regulating mitochondrial respiration, oxygen diffusion, and O2•− generation. In turn, increased O2•− production can scavenge free •NO to yield ONOO¯. In this manner the relative levels of •NO and O2•− are important in influencing mitochondrial respiratory regulation, and the production of downstream reactive species (e.g. H2O2, ONOO¯, etc.).

Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins (UCPs) are a family of mitochondrial anion carriers that appear to play a role in proton conductance across the inner membrane, can be associated with thermogenesis, and play a role in regulating mitochondrial membrane potential, and thus, mitochondrial ROS production [50-56]. UCPs can regulate the production of mitochondrial oxidants by modulating the proton “leak” across the inner membrane. The greatest levels of mitochondrial O2•− production are associated with high membrane potentials; consequently proton “leak” can reduce mitochondrial oxidant formation. In this regard, low UCP expression may be associated with reduced proton “leakage” and high membrane potentials, and thus, increased O2•− production. Interestingly, it has been noted that O2•− activates UCPs indirectly, through lipid peroxidation products, and reactive aldehydes such as 4-hydroxynonenal [57].

Antioxidant expression and cytokine effects are also important factors influencing the steady state levels of specific mitochondrial oxidants, and thus play a significant role in cell function and redox signaling in the mitochondrion. Numerous cytokines can either directly or secondarily alter cellular and/or mitochondrial oxidant production [58;59]. For example, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) increases SOD2 transcripts in NIH3T3 cells, a process that is thought to be mediated by the mitogen activated protein kinase kinase 1 (MEK1) and extracellular signal related kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), which induce early growth-responsive-1 (Egr-1) protein that stimulates expression of SOD2 transcription [60].

Consequently, the reactivity and biological effects of O2•−, •NO, and ONOO¯ formation are influenced by several factors, including the relative concentrations of O2•− and •NO, antioxidant concentration gradients, and local cellular phasic environment (e.g. hydrophobic vs. hydrophilic) and compartmentalization (e.g. organelles) characteristics.

4.3 Mitochondria are Targets of ROS

Numerous reports have shown that mitochondria are sensitive to both reactive oxygen and nitrogen species mediated damage and alterations in function [26;39;41;48;61-63]. Whereas ROS and RNS are capable of targeting a variety of subcellular components, the mitochondrial membranes, proteins and mtDNA appear particularly sensitive to oxidative and nitrosative damage [39;61;62;64-66]. Studies have shown that reactive species such as H2O2 and ONOO¯ can induce a variety of effects, including preferential and sustained mtDNA damage, altered mitochondrial transcript levels and mitochondrial protein synthesis, and lowered mitochondrial redox potentials in vascular cells [39]. RNS and ROS mediate post-translational modifications of mitochondrial proteins that can result in their inactivation (e.g. SOD2, ANT) or altered function (e.g. cytochrome c, aconitase) [41;61;67-71]. For example, nitration of Tyr34 on SOD2 results in enzyme inactivation, and it has been shown that increased 3-nitrotyrosine levels of SOD2 in vivo are associated with decreased specific activity of the enzyme [67;72]. Similarly, cytochrome c can be oxidized and nitrated (Tyr67) which induces profound changes in its redox properties, including an increase in peroxidase activity [73]. In this manner, cytochrome c catalyzes the H2O2 mediated oxidation of various electron donors, and participates as a catalyst in mitochondrial lipid peroxidation. It has also been shown that reactive halogen species (RHS), such as HOCl (a product of myeloperoxidase), inhibit mitochondrial electron transport and have been shown to oxidize cytochrome c. HOCl treatment of cytochrome c results in the oxidation of the heme ligand (Met80), increasing cytochrome c peroxidase activity and ability to oxidize tyrosine to tyrosyl radical in the presence of H2O2 [74]. Additionally, HOCl oxidized cytochrome c impairs the ability to support oxygen consumption, suggesting that protein oxidation of cytochrome c may break the electron transport chain and inhibit energy transduction in the mitochondria [74]. Consequently, hemoproteins with peroxidase-like activities may also contribute to mitochondrial oxidative damage.

5. Mitochondrial Damage

Mitochondrial damage can result in altered cellular energetic capabilities, and a variety of important functions regulated by mitochondrial oxidant generation and response, thus mediating changes in cell function that may not be directly related to energetics. For example, it has been shown that cardiac mitochondria that sustain ischemic injury are more sensitive (complex IV activity) to changes in •NO concentration when compared to controls [75], and that inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis in endothelial cells increases cellular ROS production and sensitivity to •NO-induced apoptosis [47]. It has also been suggested that mitochondria are important in the activation of NFκB, a protein that plays a central role in the regulation of many genes involved in cellular defense mechanisms, pathogen defenses, immunological responses, and expression of cytokines and cell adhesion molecules. ROS generated in the mitochondrial respiratory chain have been proposed as intermediate second messengers in the activation of NFκB by TNFα and IL-1 [76-78]. Consistent with this notion, cells lacking functional mitochondrial electron transport as a result of drug treatment or organelle depletion also show significant suppression of NFκB activation [79]. More recently, it has been shown that inhibition of flavin or heme-containing proteins prevents H2O2-induced transactivation of the EGFR and stimulation of downstream targets JNK and Akt. Inhibitors of mitochondrial respiratory function or uncouplers also produce this effect, as does generation of mitochondria lacking mtDNA [80]. Mitochondrial function also appears to have an impact on H2O2 induced growth factor transactivation (both VEGF-2 receptor and PDGFβ receptor in endothelium and fibroblasts, respectively). Growth factor receptor transactivation and its downstream signaling in response to H2O2 is abrogated by mitochondrial targeted antioxidants, but not by non-targeted counterparts, suggesting the involvement of mitochondrial oxidants in these events[80]. Consequently, in addition to the clear association with energy production, mitochondrial damage may also cause “deregulation” of mitochondrial produced oxidants, thus altering the effects of certain signaling factors by shifting a “cytoprotective” signal to that of a cytotoxic effect. Hence, the relative balance between the stimuli of mitochondrial oxidant production and the concomitant accumulation of organellar damage can ultimately influence cellular response and function, and thus the cellular response to increased oxidative stress.

6. Mitochondrial Damage/Dysfunction is associated with CVD

Many CVD risk factors have been reported to cause cardiovascular mitochondrial damage and/or dysfunction [72;81-86]. Several lines of evidence suggest that an association exists between CVD development, mitochondrial damage and function. It has been shown that CVD patients have increased mtDNA damage when compared with healthy controls in both the heart and aorta [72;81;87;88]. Atherosclerotic lesions in brain microvessels from Alzheimer’s (AD) patients and rodent AD models have significantly more mtDNA deletions and abnormalities, (as do the endothelial and perivascular cells), suggesting the mitochondria within the vascular wall can be central targets for oxidative stress induced damage [89]. Chronic ischemia increases both mtDNA deletions in human heart tissue [88] and cardiac mitochondrial sensitivity to inhibitors of cellular respiration [75]. Ex vivo studies in rat heart have shown that ischemia reduces myocardial ANT activity, and reperfusion further contributes to the loss of both ANT and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) capacities [63]. Using a mouse model for myocardial infarction (MI), it was found that previous MI is associated with increased RS (left ventricle), and decreased mtDNA copy number, mitochondrial encoded gene transcripts, and related enzymatic activities (complexes I, III and IV). However, nuclear encoded genes (complex II) and citrate synthase, are unaffected [90]. Cardiotoxic RS generators increase mtDNA deletions and lipid peroxidation in the myocardial mitochondria; overexpression of mitochondrial antioxidants prevent these effects and increase cardiac tolerance to ischemia [91]. Decreased vascular SOD2 specific activities have been associated with increased exposure to CVD risk factors [72], susceptibility to ischemia/reperfusion mediated cardiac damage, and resistance to cardiac preconditioning [92].

Deficiencies in mitochondrial antioxidants and/or regulatory proteins such as SOD2 or UCPs that modulate mitochondrial oxidant production have been shown to promote the onset of CVD in vivo, consistent with the notion that mitochondrial generated oxidants can contribute to atherogenesis [81;93]. Likewise, overexpression of mitochondrial antioxidants (e.g. SOD2) and/or UCPs have generally been shown to protect against the effects of ischemia/reperfusion and oxidative stress [91;94;95]. However, studies by Bernal-Mizrachi and coworkers have shown that overexpression of UCP-1, (a protein typically expressed in brown adipose tissue) in aortic smooth muscle cells in vivo was shown to increase superoxide formation and hypertension and exacerbate atherosclerotic lesion formation in a cholesterol independent manner [96]. These results were somewhat unexpected since: i) decreased mitochondrial membrane potential due to the increased expression of UCP-1 should decrease superoxide formation; ii) overexpression of UCP-1 in skeletal muscle reduces blood pressure and increases insulin sensitivity in genetically obese mice;[97] iii) studies investigating the impact of UCP-2, a member of the UCP family that is widely expressed in a variety of tissues including the cardiovasculature, have shown that increased UCP-2 expression reduces ROS generation and prevents mitochondrial overload in cardiomyocytes,[94] and iv) loss of UCP-2 expression increases atherosclerotic lesion formation in vivo.[93] However, the presence of multiple UCP isoforms raises the possibility of distinct functional importance of the different UCP proteins, potentially explaining the contrasting experimental results between UCP-1 and UCP-2 described above. Similarly, studies examining the effects of cytosolic SOD (SOD1) overexpression failed to reduce atherogenesis [98], whereas reduced SOD2 levels hastened the onset of atherogenesis in mice [81]. Consequently, the impact of endogenous UCP and SOD expression in the absence or overexpression of specific UCPs or SODs (e.g. UCP-2 or SOD2 levels during UCP-1 or SOD1 overexpression, respectively) may shed light on the relative importance of each in CVD development. Nonetheless, these studies do suggest that altered metabolic and antioxidant efficiency (and thus O2•− formation) due to changes in UCP and/or SOD activity can contribute to vascular dysfunction.

6.1 Mitochondrial DNA Damage and CVD

The mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) encodes 13 protein components essential for the proper function of the mitochondrial respiratory chain and oxidative phosphorylation. Consequently, mtDNA damage will impact mitochondrial functions such as energetic and oxidant signaling capacities. Many “pro-atherogenic” factors (i.e. hypercholesterolemia, cigarette smoke exposure, oxidative stress) have been associated with significantly increased mtDNA damage both in vitro and in vivo [39;72;81;99]. The susceptibility of the mtDNA to damage is thought to be due to several factors, including the lack of both protective histone and non-histone proteins and a relatively limited DNA repair capability compared to the nucleus. Additionally, the mtDNA is attached to the matrix side of the mitochondrial inner membrane, putting it in close proximity to reactive lipophilic species and reactive lipid oxidation products (generated within the membrane) that are capable of modifying the mtDNA. In vitro studies have shown that ROS and RNS induce a variety of effects in both vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells, including preferential and sustained mtDNA damage, altered mitochondrial transcript levels, and decreased mitochondrial protein synthesis [39]. The resulting mtDNA damage as well as altered transcriptional and translational functions in the mitochondrion likely result in decreased efficiency of mitochondrial replication and assembly of respiratory chain proteins. This would result in increased mitochondrial dysfunction and greater susceptibility to the damaging effects of ROS/RNS. In support of this concept, it has been shown that high levels of •NO decrease the levels of mitochondrial respiratory proteins in endothelial cells and increase the susceptibility to cell death [47]. In vivo studies have shown that cardiovascular mtDNA damage is increased in animal models of CVD [72;81], and studies in humans have shown that CVD patients have increased mtDNA damage compared with healthy controls in both the heart [87;88] and aorta [81]. Whether this damage is an effect or initiator of CVD remains unclear although animal studies have shown that vascular mtDNA damage is increased in animal models of atherosclerosis; moreover, this damage occurs prior to or coincidental with disease development [72;81].

7. Tobacco Smoke, Mitochondrial Damage and Dysfunction

Smoking reduces arterial oxygen carrying capacity through increased serum carboxyhemoglobin levels, and causes OXPHOS dysfunction in cardiac cells [85;100-102]. The activity of the myocardial cytochrome oxidase (complex IV) falls 25% after a single 30 minute exposure to secondhand smoke in rats, and the activity continues to decline with prolonged exposures [100]. Similarly, cigarette smoke appears to inhibit mitochondrial OXPHOS in platelets, resulting in increased generation of mitochondrial RS [103]. Rats exposed to passive cigarette smoke from two cigarettes per day for two months have severely damaged myocardial OXPHOS function during reperfusion injury [85]. Cigarette smoke exposure also increases sensitivity to heart ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats [85]. Smoke related cardiomyopathy is also related to mitochondrial dysfunction. Passive smoke exposure results in impaired OXPHOS, diminished cytochrome oxidase activity, and increased mitochondrial F1 ATPase protein. Levels of CoQ are decreased as well [86;104]. Second-hand smoke exposure in mice causes significant aortic mtDNA damage, reduced ANT activity, increased nitration and inactivation of SOD2, and mitochondrial dysfunction compared with unexposed mice [72]. When combined with other CVD risk factors (e.g. hypercholesterolemia), second-hand tobacco smoke synergistically accelerates both mitochondrial damage and atherogenesis [72]. Treatment of VSMC with benzo-a-pyrene (BaP), a component of cigarette smoke that has previously been shown to induce atherogenesis in cockerels,[105] does not appear to induce any stress response or loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, but does induce cell death by necrosis[106]. More recently, it has been shown that rats treated with benzo-a-pyrene to induce an atherogenic phenotype have upregulated expression of mtDNA transcripts. Cultured cells from these rats have increased growth rates and marked enhancement of proliferation in response to serum mitogens [107]. Treatment of human monocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells with tobacco smoke filtrate results in the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, and increased apoptosis and necrosis; effects that are prevented by n-acetylcysteine treatment [106]. Similarly, SOD2 overexpression in mouse fibroblasts significantly reduces the cytotoxicity of cigarette smoke [108].

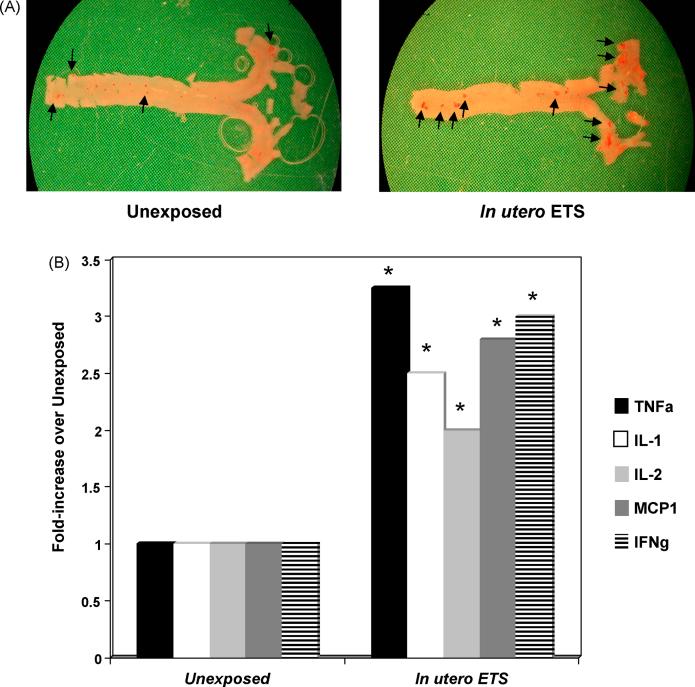

Cardiovascular disease generally begins decades before the onset of clinical manifestations; however, the majority of studies examining the impact of tobacco on CVD development have been performed in adults (both human and animal models), or, have been retrospective. One study in adults has shown that childhood smoking is a risk factor for decreased carotid artery elasticity in adulthood [109], while others have examined the effects of cigarette smoke exposure in younger adults, showing that atherosclerotic lesion development is increased with cigarette smoke exposure in 15-34 year olds, as shown by autopsies [110]. These studies suggest that childhood exposure and/or conditions within the fetal environment may influence disease development in exposed offspring. Some of the earliest studies examining the effects of gestational cigarette smoke exposure reveal that umbilical cords from exposed children have increased degree of atherogenic pathology [111]. More recently, it has been shown that children and young adults exposed to cigarette smoke have increased vascular wall thickening and atherosclerotic lesion formation [110;112]. Similarly, cigarette smoke exposure due to parental smoking is associated with atherosclerotic lesions in autopsy in children 1-36 months old [113]. Neonatal and in utero exposure to cigarette smoke increases sensitivity of aortic rings to phenylephrine induced vasoconstriction and reduces the maximum endothelium-dependent relaxation by acetylcholine, and increased the EC50 dose. In utero ETS exposure increased the EC50 dose of nitroglycerin in endothelium-independent vasodilation [114]. Neonatal ETS exposure results in increased levels of endothelin-1, which can induce growth factor release from vascular smooth muscle cells, ROS production by macrophages, and causes the expression of adhesion molecules in endothelial cells [115]. Prenatal ETS exposure has also been associated with larger myocardial infarct areas after ischemia-reperfusion [116]. Results within our laboratory examining the effects of gestational exposure to cigarette smoke in adult mice have shown that in utero exposure to cigarette smoke is associated with increased levels of atherogenic cytokines, including MCP-1 and TNF-α (Figure 3). Similarly, it has been reported that childhood exposure to cigarette smoke correlates increased MCP-1 levels, a monocyte chemoattractant [117].

Figure 3.

In utero exposure to cigarette smoke increases adult atherosclerotic lesion formation and inflammatory cytokine levels. (A) Oil red-O staining (oil red-O is an oil soluble dye, which partitions into lipids and stains neutral fats a brilliant red color) of whole aortas from 16-17 week old apoE -/- mice fed 4% chow diets that were exposed in utero (days 1-19 gestation, 5 hrs/day) to filtered air (left panel) or 1 mg/m3 total suspended particulate ETS (right panel). Whole aortas were stained with oil red-O as previously described to assess atherosclerotic lesion formation [142]. Adult mice exposed to ETS in utero had significantly increased levels of oil red-O staining compared to unexposed controls. Positively staining areas are indicated by arrows. (B) Aortic homogenates were prepared from 16-17 week old apoE -/- mice fed 4% chow diets that were exposed in utero (days 1-19 gestation, 5 hrs/day) to filtered air or 10 mg/m3 total suspended particulate ETS as previously described [142] and TNFα (TNFa), IL-1, IL-2, MCP1, and IFN γ (IFNg) were quantified via immunoblot. Aortas from animals exposed gestationally to ETS had significantly (* P <0.05) increased levels of all cytokines compared to unexposed controls.

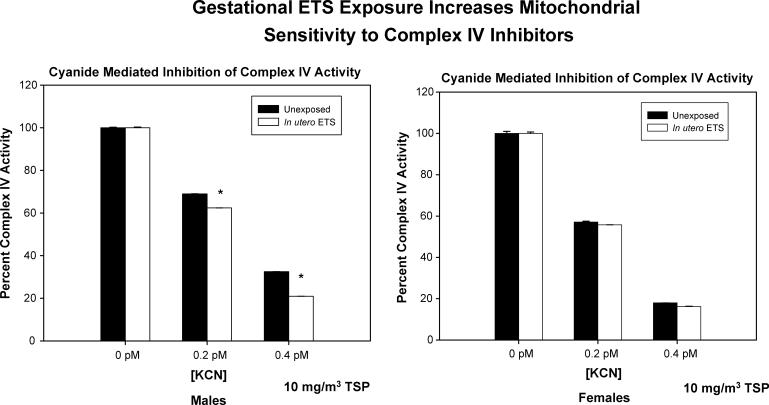

The impact of in utero or childhood cigarette smoke exposure on the mitochondrion are only beginning to be studied. Work from our laboratory has shown that in utero ETS exposure is associated with increased atherogenesis (Figure 3), oxidant stress and mtDNA damage in mice, and more recently is associated with increased sensitivity to complex IV inhibitors (Figure 4). Similarly, it has been reported that smoking decreases complex III activity in placenta and decreases mtDNA levels, showing that smoking is associated with placental mitochondrial dysfunction [118]. The mediating mechanisms likely involve the placental transfer of components of tobacco smoke to fetal tissues [119]. In vivo studies have shown that components of tobacco smoke target the mtDNA [120]. Carbon monoxide directly inhibits oxidative phosphorylation by reducing the amount of available oxygen (by forming carboxyhemoglobin, COHb) to the mitochondrion [121]. Moreover, •NO control of respiration may exacerbate the effects of hypoxia due to by ETS induced inflammation and the induction of iNOS. Hence, vascular mitochondrial damage sustained in utero could compromise energetic function and/or mitochondrial-dependent signaling in vascular cells earlier in life, markedly increasing the risk for atherosclerotic lesion development in exposed offspring. Hence, these findings suggest that fetal exposure to cardiovascular disease risk factors may cause mitochondrial damage which promotes earlier onset of disease in adults.

Figure 4.

In utero exposure to cigarette smoke increases complex IV sensitivity to inhibition by cyanide. Complex IV activity was assessed in aortas from 16-17 week old apoE -/- mice fed 4% chow diets that were exposed in utero (days 1-19 gestation, 5 hrs/day) to filtered air (left panel) or 10 mg/m3 total suspended particulate ETS. Inhibition of complex IV activity by potassium cyanide (KCN, a known inhibitor of cytochrome oxidase) was significantly increased (indicated by asterisks, P < 0.05) in aortas from 16-17 week old male apoE -/- mice exposed to ETS in utero (10 mg/m3 total suspended particulate; days 1-19 gestation, 5 hrs/day) compared with unexposed mice.

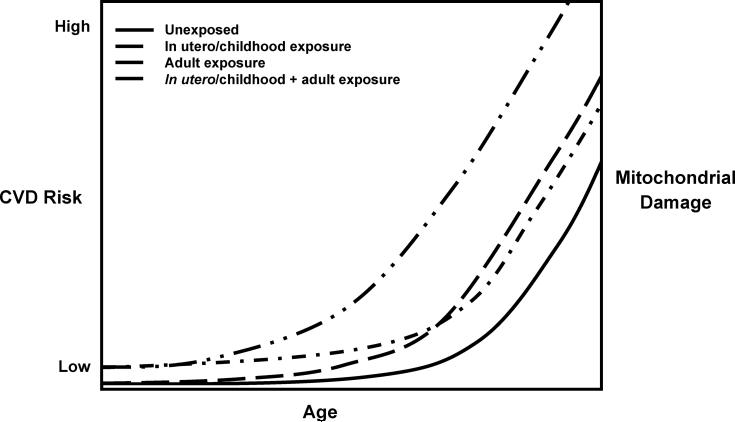

The basic concepts of developmental exposure, mitochondrial damage and cardiovascular risk are summarized in Figure 5. This model is based upon the concept that the extent of sustainable mitochondrial damage that can be tolerated without loss of function is limited over the lifetime of the organelle. A prediction of the model is that individuals experiencing prenatal and/or childhood cardiovascular disease risk factor exposure may experience the clinical manifestations of cardiovascular disease earlier in life.

Figure 5.

Model of developmental exposure to environmental oxidants, mitochondrial damage and relative CVD risk development. Unexposed individuals will have increasing mitochondrial damage and risk for CVD development with age, as do in individuals exposed to environmental oxidants in utero or during childhood. Similar mitochondrial damage and CVD risk may exist for individuals chronically exposed to environmental oxidants as adults, whereas the greatest mitochondrial damage and risk for CVD development exists in individuals exposed to environmental oxidants both in utero/childhood and adults.

Studies have also shown that gestational exposures to known cardiovascular disease risk factors increase adult atherosclerotic lesion development in well characterized mouse models [99;122]. These studies also revealed the existence of a gender bias; males were more susceptible to the cardiovascular effects potentially mediated by changes in the in utero environment. The basis of these differences are not yet known but is interesting to speculate that both estrogen receptors, α and β, have been found in the mitochondrion, with ERβ often present at its highest cellular levels within the mitochondrion [123-126].

Future directions and implications

A growing number of studies are showing that environmental oxidants, including tobacco smoke, cause mitochondrial damage and dysfunction. Given its multiple cellular functions, mitochondrial dysfunction and damage can potentially be related to several classes of human disease, including CVD. Altered mitochondrial antioxidant capability, mtDNA damage, and modification of mitochondrial proteins and related enzymatic activities have been associated with hastened onset of CVD in animal models [72;81;99]. These emerging concepts provide the impetus to determine how mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to human disease. Components of environmental oxidants presumably interact directly and/or indirectly (e.g. via inflammation) with the mitochondrion to induce damage and the formation of ROS. The loss of control, or “dysregulation” of mitochondrial reactive species generation can contribute to the pathology of CVD through a number of mechanisms including damage to mtDNA. However, the precise mechanisms involved in mediating mitochondrial damage and dysfunction are not yet known. One possibility is that increased levels of lipid oxidation products (a result of environmental oxidant exposure) may interact with the mitochondrion to stimulate reactive species formation, and may also cause mitochondrial damage when present at high concentrations. Pre-existent mitochondrial damage will result in altered response to these species (oxidized lipids) and other factors known to interact with the mitochondrion as part of their normal function (e.g. cytokines such as TNF-α, etc.). Prolonged “deregulation” of mitochondrial function (i.e. oxidant production and ATP generation) due to damage will lead to cellular dysfunction and disease development.

Another area of environmental disease susceptibility that may involve the mitochondrion is the concept of “mitochondrial genetic susceptibility”. By virtue of evolutionary history, mtDNA genotypes have undergone both geographic and climatic selection [22]. Hence, some mtDNA haplotypes are associated with “tight coupling” or high energy efficiency (advantageous in sub-Saharan latitudes), whereas other haplotypes are associated with “less coupled” mitochondria that are less energetically efficient but more thermogenic (advantageous in Northern latitudes). An additional biological effect of these two classes of mtDNA haplotypes is that the tightly coupled mitochondria although energetically efficient, generate more oxidants relative to the less coupled mitochondria - thereby, making them theoretically more vulnerable to disease associated with increased oxidant stress or mitochondrial oxidant generation. Although less coupled mitochondria have decreased energetic efficiency, they produce less oxidants, and therefore are less susceptible to disease associated with increased oxidant stress. Conversely, these susceptibilities would be reversed in the case of disease associated with energetic capacity, with the haplotypes associated with less coupled mitochondria being the most vulnerable. Overall, the most provocative concept in these projections is that mitochondrial function and damage play a more significant role in the development and evolution of human disease susceptibility than previously considered.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants ES 11172 (SWB), HL 77419 (SWB), Philip Morris USA (SWB) and a NIH GRS (CMH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- [1].World Health Organization . The world health report 2003 - shaping the future: Neglected Global Epidemics. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2003. pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- [2].American Heart Association . Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics - 2005 Update. American Heart Association; Dallas, TX: 2005. pp. 1a–60. [Google Scholar]

- [3].American Heart Association Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics - 2006 Update. Circulation. 2006;105:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ross R. Mechanisms of Disease: Atherosclerosis - An Inflammatory Disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Harrison D, Griendling KK, Landmesser U, Hornig B, Drexler H. Role of oxidative stress in atherosclerosis. American Journal of Cardiology. 2003;91:7A–11A. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Madamanchi NR, Vendrov A, Runge MS. Oxidative stress and vascular disease. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. 2005;25:29–38. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000150649.39934.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Puddu GM, Cravero E, Arnone G, Muscari A, Puddu P. Molecular aspects of atherogenesis: new insights and unsolved questions. Journal of Biomedical Science. 2005;12:839–853. doi: 10.1007/s11373-005-9024-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ceconi C, Boraso A, Cargnoni A, Ferrari R. Oxidative stress in cardiovascular disease: myth or fact? Arch.Biochem.Biophys. 2003;420:217–221. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Diaz MN, Frei B, Vita JA, Keaney JF. Mechanisms of disease - Antioxidants and atherosclerotic heart disease. N.Engl.J.Med. 1997;337:408–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708073370607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cai H, Harrison DG. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases - The role of oxidant stress. Circ.Res. 2000;87:840–844. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dhalla NS, Temsah RM, Netticadan T. Role of oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. Journal of Hypertension. 2000;18:655–673. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Iuliano L. The oxidant stress hypothesis of atherogenesis. Lipids. 2001;36:S41–S44. doi: 10.1007/s11745-001-0680-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Reilly M, Delanty N, Lawson JA, Fitzgerald GA. Modulation of oxidant stress in vivo in chronic cigarette smokers. Circulation. 1996;94:19–25. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Reilly M, Pratico D, Delanty N, DiMinno G, Tremoli E, Rader D, Kapoor S, Rokach J, Lawson J, FitzGerald GA. Increased formation of distinct F2 isoprostanes in hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 1998;98:2822–2828. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.25.2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pratico D, Tangirala RK, Rader DJ, Rokach J, FitzGerald GA. Vitamin E suppresses isoprostane generation in vivo and reduces atherosclerosis in apoE deficient mice. Nature Medicine. 1998;4:1189–1192. doi: 10.1038/2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Pratico D, Barry OP, Lawson JA, Adiyaman M, Hwang S-W, Khanapure SP, Iuliano L, Rokach J, FitzGerald GA. IPF2α-I: An index of lipid peroxidation in humans. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 1998;95:3449–3454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ito H, Torii M, Suzuki T. Decreased superoxide dismutase activity and increased superoxide anion production in cardiac hypertrophy of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin.Exp.Hypertens. 1995;17:803–816. doi: 10.3109/10641969509033636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Holland JA, Ziegler LM, Meyer JW. Atherogenic levels of low-density lipoprotein increase hydrogen peroxide generation in cultured human endothelial cells: Possible mechanism of heightened endocytosis. J.Cell.Physiol. 1996;166:144–151. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199601)166:1<144::AID-JCP17>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ohara Y, Peterson TE, Harrison DG. Hypercholesterolemia increases endothelial superoxide anion production. J.Clin.Invest. 1993;91:2546–2551. doi: 10.1172/JCI116491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Watts GF, Playford DA. Dyslipoproteinaemia and hyperoxidative stress in the pathogenesis of endothelial dysfunction in a non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: an hypothesis. Atherosclerosis. 1998;141:17–30. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)00170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rousselot DB, Bastard JP, Jaudon MC. Consequences of the diabetic status on the oxidant/antioxidant balance. Diabetes Metabolism. 2000;26:163–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ruiz-Pesini E, Mishmar D, Brandon M, Procaccio V, Wallace DC. Effects of purifying and adaptive selection on regional variation in human mtDNA. Science. 2004;303:223–226. doi: 10.1126/science.1088434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wallace DC. The mitochondrial genome in human adaptive radiation and disease: On the road to therapeutics and performance enhancement. Gene. 2005;354:169–180. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wallace DC. A Mitochondrial Paradigm of Metabolic and Degenerative Diseases, Aging, and Cancer: A Dawn for Evolutionary Medicine. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:359–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhang Y, Marcillat O, Giulivi C, Ernster L, Davies KJ. The oxidative inactivation of mitochondrial electron transport chain components and ATPase. J.Biol.Chem. 1990;265:16330–16336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Turrens JF. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J Physiol. 2003;552:335–344. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Forman HJ, Boveris A. In: Free Radicals In Biology. Prior WA, editor. Academic Press; Orlando: 1982. pp. 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Forman HJ, Boveris A. Superoxide radical and hydrogen peroxide in mitochondria. In: Prior WA, editor. Free Radicals In Biology. Academic Press; Orlando: 1982. pp. 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Boveris A, Turrens JF. Production of superoxide anion by the NADH dehydrogenase of mammalian mitochondria. In: Bannister J, Hill H, editors. Chemical and biochemical aspects of superoxide and superoxide dismutase. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1980. pp. 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Turrens JF, Boveris A. Generation of superoxide anion by the NADH dehydrogenase of bovine heart mitochondria. Biochem.J. 1980;191:421–427. doi: 10.1042/bj1910421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chance B, Sies H, Boveris A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol.Rev. 1979;59:527–605. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Baas AS, Berk BC. Differential activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by H2O2 and O2¯ in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1995;77:29–36. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Chen K, Vita JA, Berk BC, Keaney JF., Jr. c-Jun-N-terminal Kinase Activation by Hydrogen Peroxide in Endothelial Cells Involves Src-dependent Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Transactivation. J.Biol.Chem. 2001;276:16045–16050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Guyton KZ, Liu Y, Gorospe M, Xu Q, Holbrook NJ. Activation of Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase by by H2O2. J.Biol.Chem. 1996;271:4138–4142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kim SM, Byun JS, Jung YD, et al. The effects of oxygen radicals on the activity of nitric oxide synthase and guanylate cyclase. E, Exp Mol Med. 1998;30:221–6. doi: 10.1038/emm.1998.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sundaresan M, Yu ZX, Fererans VJ, Irani K, Finkel T. Requirement for generation of H202 for platelet-derived growth factor signal transduction. Science. 1995;270:296–299. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ide T, Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, Suematsu N, Hayashidani S, Ichikawa K, Utsumi H, Machida Y, Egashira K, Takeshita A. Direct evidence for increased hydroxyl radicals orginating from superoxide in the failing myocardium. Circ.Res. 2000;86:152–157. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kissner R, Nauser T, Bugnon P, Lye PG, Loppenol WH. Formation and properties of peroxynitrite as studied by laser flash photolysis, high-pressure stopped-flow technique, and pulse radiolysis. Chem.Res.Toxicol. 1997;10:1285–1292. doi: 10.1021/tx970160x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ballinger SW, Patterson WC, Yan C-N, Doan R, Burow DL, Young CG, Yakes FM, Van Houten B, Ballinger CA, Freeman BA, Runge MS. Hydrogen peroxide and peroxynitrite induced mitochondrial DNA damage and dysfunction in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Circ.Res. 2000;86:960–966. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.9.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Leeuwenburgh C, Hardy MM, Hazen SL, Wagner P, Oh-ishi S, Steinbrecher UP, Heinecke JW. Reactive nitrogen intermediates promote low density lipoprotein oxidation in human atherosclerotic intima. J.Biol.Chem. 1997;272:1433–1436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].MacMillan-Crow LA, Crow JP, Thompson JA. Peroxynitrite-mediated inactivation of manganese superoxide dismutase involves nitration and oxidation of critical gyrosine residues. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1613–1622. doi: 10.1021/bi971894b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Levonen AL, Patel RP, Brookes P, Go YM, Jo H, Parthasarathy S, Anderson PG, Darley-Usmar VM. Mechanisms of cell signaling by nitric oxide and peroxynitrite: from mitochondria to MAP kinases. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2001;3:215–229. doi: 10.1089/152308601300185188. review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ischiropoulos H. Biological tyrosine nitration: a pathophysiological function of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species. Arch.Biochem.Biophys. 1998;356:1–11. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Beckman JS. Oxidative damage and tyrosine nitration from peroxynitrite. Chem.Res.Toxicol. 1996;9:836–844. doi: 10.1021/tx9501445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kimura S, Zhang GX, Nishiyama A, Shokoji T, Yao L, Fan YY, Rahman M, Suzuki T, Maeta H, Abe Y. Role of NAD(P)H oxidase- and mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species in cardioprotection of ischemic reperfusion injury by angiotensin II. Hypertension. 2005;45:860–866. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000163462.98381.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ramachandran A, Levonen AL, Brookes PS, Ceaser E, Shiva S, Barone MC, Darley-Usmar VM. Mitochondria, nitric oxide, and cardiovascular dysfunction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1465–1474. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ramachandran A, Moellering DR, Ceaser E, Shiva S, Xu J, Darley-Usmar VM. Inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis results in increased endothelial cell susceptibility to nitric oxide-induced apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6643–6648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102019899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Cassina A, Radi R. Differential inhibitory action of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite on mitochondrial electron transport. Arch.Biochem.Biophys. 1996;328:309–316. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Ramachandran A, Ceaser E, Darley-Usmar VM. Chronic exposure to nitric oxide alters the free iron pool in endothelial cells: Role of mitochondrial respiratory complexes and heat shock proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:384–389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304653101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Garlid KD, Jaburek M, Jezek P. Mechanism of uncoupling proteins action. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:803–806. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Jaburek M, Varecha M, Gimeno RE, Dembski M, Jezek P, Zhang M, Burn P, Tartaglia LA, Garlid KD. Transport function and regulation of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins 2 and 3. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26003–26007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Klingenberg M, Winkler E, Echtay K. Uncoupling protein, H+ transport and regulation. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:806–811. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Nedergaard J, Golozoubova V, Matthias A, Shabalina I, Ohba K, Ohlson K, Jacobsson A, Cannon B. Life without UCP1: mitochondrial, cellular, and organismal characteristics of the UCP1-ablated mice. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:756–763. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Stuart JA, Cadenas S, Jacobsons MB, Roussel D, Brand MD. Mitochondrial proton leak and the uncoupling protein 1 homologues. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2001;1504:144–158. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Dulloo AG, Samec S, Seydoux J. Uncoupling protein 3 and fatty acid metabolism. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:785–791. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Nedergaard J, Cannon B. The “novel” “uncoupling” proteins UCP2 and UCP3: what do they really do? Pros and cons for suggested functions. Exp Physiol. 2003;88:65–84. doi: 10.1113/eph8802502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Talbot DA, Lambert AJ, Brand MD. Production of endogenous matrix superoxide from mitochondrial complex I leads to activation of uncoupling protein 3. FEBS Lett. 2004;556:111–115. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01386-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Manna SK. Overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase suppresses tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis and activation of nuclear transcription factor-kappaB and activated protein-1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13245–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Schulze-Osthoff K, Bakker AC, Vanhaesebroeck B, Beyaert R, Jacob WA, Fiers W. Cytotoxic activity of tumor necrosis factor is mediated by early damage of mitochondrial functions. Evidence for the involvement of mitochondrial radical generation. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5317–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Maehara K, Oh-Hashi K, Isobe K-I. Early growth-responsive-1-dependent manganese superoxide dismutase gene transcription mediated by platelet-derived growth factor. FASEB J. 2001;15:2025–2026. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0909fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Yan L-J, Sohal RS. Mitochondrial adenine nucleotide translocase is modified oxidatively during aging. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 1998;95:12896–12901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.12896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Yakes FM, Van Houten B. Mitochondrial DNA damage is more extensive and persists longer than nuclear DNA damage in human cells following oxidative stress. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 1997;94:514–519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Duan J, Karmazyn M. Relationship between oxidative phosphorylation and adenine nucleotide translocase activity in two populations of cardiac mitochondria and mechanical recovery of ischemic hearts following reperfusion. Can.J.Physiol.Pharmacol. 1989;67:704–709. doi: 10.1139/y89-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Ballinger SW, Shoffner JM, Hedaya EV, Trounce I, Polak MA, Koontz DA, Wallace DC. Maternally trasnmitted diabetes and deafness associated with a 10.4 kb mitochondrial DNA deletion. Nat.Genet. 1992;1:11–15. doi: 10.1038/ng0492-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Ballinger SW, Van Houten B, Jin GF, Conklin CA, Godley BF. Hydrogen peroxide causes significant mitochondrial DNA damage in human RPE cells. Exper.Eye Res. 1999;68:765–772. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Yan L-J, Sohal RS. Prevention of flight activity prolongs the life span of the housefly, Musca Domestica, and attenuates the age-associated oxidative damage to specific mitochondrial proteins. Free Radic.Biol.Med. 2000;29:1143–1150. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00423-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].MacMillan-Crow LA, Crow JP, Kerby JD, Beckman JS, Thompson JA. Nitration and inactivation of manganese superoxide dismutase in chronic rejection of human renal allografts. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 1996;93:11853–11858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Flohe L, Otting F. Superoxide dismutase assays. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:93–104. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Hausladen A, Fridovich I. Measuring nitric oxide and superoxide: rate constants for aconitase reactivity. Methods Enzymol. 1996;269:37–41. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)69007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Tarpey MM, Wink D, Grisham M. Methods for detection of reactive metabolites of oxygen and nitrogen: in vitro and in vivo considerations. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;286:R431–R444. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00361.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Castro L, Eiserich JP, Sweeney S, Radi R, Freeman BA. Cytochrome c: a catalyst and target of nitrite-hydrogen peroxide-dependent protein nitration. Arch.Biochem.Biophys. 2004;421:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Knight-Lozano CA, Young CG, Burow DL, Hu Z, Uyeminami D, Pinkerton K, Ischiropoulos H, Ballinger SW. Cigarette Smoke Exposure and Hypercholesterolemia increase mitochondrial damage in cardiovascular tissues. Circulation. 2002;105:849–854. doi: 10.1161/hc0702.103977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Cassina AM, Hodara R, Souza JM, Thomson L, Castro L, Ischiropoulos H, Freeman BA, Radi R. Cytochrome c nitration by peroxynitrite. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21409–21415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909978199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Chen Y-R, Deterding LJ, Sturgeon BE, Tomer KB, Mason RP. Protein oxidation of cytochrome c by reactive halogen species enhances its peroxidase activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29781–29791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Brookes PS, Zhang J, Dai L, Zhou F, Parks DA, Darley-Usmar VM, Anderson PG, Brookes PS, Zhang J, Dai L, Zhou F, Parks DA, Darley-Usmar VM, Anderson PG. Increased sensitivity of mitochondrial respiration to inhibition by nitric oxide in cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:69–82. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Schulze-Osthoff K, Los M, Baeuerle PA. Redox signaling by transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1 in lymphocytes. Biochem.Pharmacol. 1995;50:735–741. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02011-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Devary Y, Rosette C, DiDonato JA, Karin M. NF-kappa B activation by ultraviolet light not dependent on a nuclear signal. Science. 1993;261:1442–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.8367725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Mohan N, Meltz MM. Induction of nuclear factor κB after low-dose ionizing radiation involves a reactive oxygen intermediate signaling pathway. Rad.Res. 1994;140:97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Schulze-Osthoff K, Beyaert R, Vandervoorde V, Haegeman G, Fiers W. Depletion of the mitochondrial electron transport abrogates the cytotoxic and gene-inductive effects of TNF. EMBO J. 1993;12:3095–3104. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Chen K, Thomas SR, Albano A, Murphy MP, Keaney JF. Mitochondrial function is required for hydrogen peroxide-induced growth factor receptor transactivation and downstream signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404859200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Ballinger SW, Patterson C, Knight-Lozano CA, Burow DL, Conklin CA, Hu Z, Reuf J, Horaist C, Lebovitz RM, Hunter G, McIntyre K, Runge MS. Mitochondrial integrity and function in atherogenesis. Circulation. 2002;106:544–549. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000023921.93743.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Li M, Absher M, Liang P, Russell JC, Sobel BE, Fukagawa NK. High glucose concentrations induce oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA in explanted vascular smooth muscle cells. Exp.Biol.Med. 2001;226:450–457. doi: 10.1177/153537020122600510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Yao PM, Tabas I. Free cholesterol loading of macrophages is associated with widespread mitochondrial dysfunction and activation of the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42468–42476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101419200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Asmis R, Begley JG. Oxidized LDL promotes peroxide mediated mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death in human macrophages. Circ Res. 2003;92:e20–e29. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000051886.43510.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].van Jaarsveld H, Kuyl JM, Alberts DW. Exposure of rats to low concentrations of cigarette smoke increases myocardial sensitivity to ischaemia/reperfusion. Basic Res.Cardiol. 1992;87:393–399. doi: 10.1007/BF00796524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Gvozdjakova A, Bada V, Sany L, Kucharska J, Kruty F, Bozek P, Trstanski L, Gvozdjak J. Smoke cardiomyopathy: disturbance of oxidative processes in myocardial mitochondria. Cardiovasc Res. 1984;18:229–232. doi: 10.1093/cvr/18.4.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Corral-Debrinski M, Shoffner JM, Lott MT, Wallace DC. Association of mitochondrial DNA damage with aging and coronary atherosclerotic heart disease. Mutat.Res. 1992;275:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(92)90021-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Corral-Debrinski M, Stepien G, Shoffner JM, Lott MT, Kanter K, Wallace DC. Hypoxemia is associated with mitochondrial DNA damage and gene induction: Implications for cardiac disease. JAMA. 1991;266:1812–1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Aliev G, Seyidova D, Neal ML, Shi J, Lamb BT, Siedlak SL, Vinters HV, Head E, Perry G, Lamanna JC, Friedland RP, Cotman C. Atherosclerotic lesions and mitochondria DNA deletions in brain microvessels as a central target for the development of human AD and AD-like pathology in aged transgenic mice. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;977:45–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Ide T, Tsutsui H, Hayashidani S, Kang D, Suematsu N, Nakamura K, Utsumi H, Hamasaki N, Takeshita A. Mitochondrial DNA damage and dysfunction associated with oxidative stress in failing hearts after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2001;88:529–535. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.5.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Chen Z, Siu B, Ho Y-S, Vincent R, Chua CC, Hamdy RC, Chua BHL. Overexpression of MnSOD protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in transgenic mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:2281–2289. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Asimakis G, Lick S, Patterson W. Postischemic recovery of contractile function is impaired in SOD2 (+/-) but not SOD1 (+/-) mouse hearts. Circulation. 2002;105:981–986. doi: 10.1161/hc0802.104502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Blanc J, Alves-Guerra MC, Esposito B, Rousset S, Gourdy P, Ricquier D, Tedgui A, Miroux B, Mallat Z. Protective role of uncoupling protein 2 in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2003;107:388–390. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051722.66074.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Teshima Y, Akao M, Jones SP, Marban E. Uncoupling protein-2 overexpression inhibits mitochondrial death pathway in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2003;93:192–200. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000085581.60197.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Bienengraeber M, Ozcan C, Terzic A. Stable transfection of UCP1 confers resistance to hypoxia/reoxygenation in a heart-derived cell line. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:861–865. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Bernal-Mizrachi C, Gates AC, Weng S, Imamura T, Knutsen RH, Desantis P, Coleman T, Townsend RR, Muglia LJ, Semenkovich CF. Vascular respiratory uncoupling increases blood pressure and atherosclerosis. Nature. 2005;435:502–506. doi: 10.1038/nature03527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Bernal-Mizrachi C, Weng S, Li B, Nolte LA, Feng C, Coleman T, Holloszy JO, Semenkovich CF. Respiratory uncoupling lowers blood pressure through a leptin-dependent mechanism in genetically obese mice. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. 2002;22:961–968. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000019404.65403.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Yang H, Roberts LJ, Shi MJ, Zhou LC, Ballard BR, Richardson A, Guo ZM. Retardation of atherosclerosis by overexpression of catalase or both Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase and catalase in mice lacking apolipoprotein E. Circ.Res. 2004;95:1075–1081. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000149564.49410.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Yang Z, Knight CA, Mamerow M, Vickers K, Penn A, Postlethwait E, Ballinger SW. Prenatal Environmental Tobacco Smoke Exposure Promotes Adult Atherogenesis and Mitochondrial Damage in apoE-/- mice fed a chow diet. Circulation. 2004;110:3715–3720. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000149747.82157.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Gvozdjak J, Gvozdjakova A, Kucharska J, Bada V. The effect of smoking on myocardial metabolism. Czech.Med. 1987;10:47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Gvozdjakova A, Kucharska J, Gvozdjak J. Effect of smoking on the oxidative processes of cardiomyocytes. Cardiology. 1992;1992:81–84. doi: 10.1159/000175780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].van Jaarsveld H, Kuyl JM, Alberts DW. Antioxidant vitamin supplementation of smoke exposed rats partially protects against myocardial ischemic/reperfusion injury. Free Radic Res Commun. 1992;17:263–269. doi: 10.3109/10715769209079518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Davis J, Shelton L, Watnabe I, Arnold J. Passive smoking affects endothelium and platelets. Arch.Intern.Med. 1989;149:386–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Gvozdjakova A, Simko F, Kucharska J, Braunova Z, Psenek P, Kyselovic J. Captopril increased mitochondrial coenzyme Q10 level, improved respiratory chain function and energy production in the left ventricle in rabbits with smoke mitochondrial cardiomyopathy. BioFactors. 1999;10:61–65. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520100107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Penn A, Chen LC, Synder CA. Inhalation of steady-state sidestream smoke from one cigarette promotes atherosclerotic plaque development. Circulation. 1994;90:1363–1367. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.3.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Vayssier-Taussat M, Camilli T, Aron Y, Meplan C, Hainaut P, Polla BS, Weksler B. Effects of tobacco smoke and benzo[a]pyrene on human endothelial cell and monocyte stress responses. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H1293–H1300. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.3.H1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Lu KP, Alejandro NF, Taylor KM, Joyce MM, Spencer TE, Ramos KS. Differential expression of ribosomal L31, Zis, gas-5 and mitochondrial mRNAs following oxidant induction of proliferative vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypes. Atherosclerosis. 2002;160:273–280. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00581-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].St Clair DK, Jordan JA, Wan XS, Gairola CG. Protective role of manganese superoxide dismutase against cigarette smoke-induced cytotoxicity. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1994;43:239–249. doi: 10.1080/15287399409531918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Li SX, Chen W, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Childhood blood pressure as a predictor of arterial stiffness in young adults - The Bogalusa Heart Study. Hypertension. 2004;43:541–546. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000115922.98155.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].McGill H, McMahan CA, Herderick E, Tracy RE, Malcom GT, Zieske AW, Strong JP, PDAY Research Group Effects of coronary heart disease risk factors on atherosclerosis of selected regions of the aorta and right coronary artery. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:836–845. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.3.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Asmussen I, Kjeldsen K. Intimal Ultrastructure of Human Umbilical Arteries. Circ.Res. 1975;36:579–589. doi: 10.1161/01.res.36.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Raitakari O, Juonala M, Kahonen M, Taittonen L, Maki-Torkko N, Jarvisalo M, Uhari M, Jokeinen E, Ronnemaa T, Akerblom H, Viikari J. Cardiovascular risk factors in childhood and carotid artery intima-media thickness in adulthood: The cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. JAMA. 2003;290:2277–2283. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.17.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Matturri L, Ottaviani G, Lavezzi A. Early atherosclerotic lesions in infancy: role of parental cigarette smoking. Virchows Archiv. 2005;447:74–80. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-1224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Hutchison SJ, Glantz SA, Zhu BQ, Sun YP, Chou TM, Chatterjee K, Deedwania PC, Parmley WW, Sudhir K. In-utero and neonatal exposure to secondhand smoke causes vascular dysfunction in newborn rats. J.Am.Coll.Cardiol. 1998;32:1463–1467. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Michael JR, Markewitz BA, Kohan DE. Oxidant stress regulates basal endothelin-1 production by cultured rat pulmonary endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;273 doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.4.L768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Zhu BQ, Sun YP, Sudhir K, Sievers RE, Browne AEM, Gao LR, Hutchison SJ, Chou TM, Deedwania PC, Chatterjee K, Glantz SA, Parmley WW. Effects of second-hand smoke and gender on infarct size of young rats exposed in utero and in the neonatal to adolescent period. J.Am.Coll.Cardiol. 1997;30:1878–1885. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00364-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Berrahmoune H, Lamont J, Herbeth B, FitzGerald P, Visvikis-Siest S. Biological determinants of an reference vaules for plasma interleukin-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, epidermal growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor: Results from the STANISLAS cohort. Clinical Chemistry. 2006;52:504–510. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.055798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Bouhours-Nouet N, May-Panloup P, Coutant R, de Casson FB, Descamps P, Douay O, Reynier P, Ritz P, Malthiery Y, Simard G. Maternal smoking is associated with mitochondrial DNA depletion and respiratory chain complex III deficiency in placenta. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;288:E171–E177. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00260.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Lu L-J, Disher RM, Reddy MV, Randerath K. 32P-Postlabeling assay in mice of transplacental DNA damage induced by the environmental carcinogens safrole, 4-aminobiphenyl, and benzo(a)pyrene. Cancer Res. 1986;46:3046–3054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Bandy B, Davison AJ. Mitochondrial mutations may increase oxidative stress: implications for carcinogenesis and aging? Free Radicals of Biology Medicine. 1990;8:523–539. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Couch NP. On the arterial consequences of smoking. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 1986;3:807–812. doi: 10.1067/mva.1986.avs0030807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Napoli C, De Nigris F, Welch JS, Calara FB, Stuart RO, Glass CK, Palinski W. Maternal hypercholesterolemia during pregnancy promotes early atherogenesis in LDL receptor-deficient mice and alters aortic gene expression determined by microarray. Circulation. 2002;105:1360–1367. doi: 10.1161/hc1102.106792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Chen JQ, Yager JD. Estrogen’s Effects on Mitochondrial Gene Expression: Mechanisms and Potential Contributions to Estrogen Carcinogenesis. Ann.N.Y.Acad.Sci. 2004;1028:258–272. doi: 10.1196/annals.1322.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Chen JQ, Eshete M, Alworth WL, Yager JD. Binding of MCF-7 cell mitochondrial proteins and recombinant human estrogen receptors alpha and beta to human mitochondrial DNA estrogen response elements. J.Cell Biochem. 2004;93:358–373. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Chen JQ, Delannoy M, Cooke C, Yager JD. Mitochondrial localization of ERalpha and ERbeta in human MCF7 cells. Am.J.Physiol Endocrinol.Metab. 2004;286:E1011–E1022. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00508.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Felty Q, Roy D. Mitochondrial signals to nucleus regulate estrogen-induced cell growth. Med.Hypotheses. 2005;64:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2003.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]