Abstract

The phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) negatively regulates cell survival and proliferation mediated by phosphoinositol 3 kinases. We have explored the role of the phosphoinositol(3,4,5)P3-phosphatase PTEN in T cell development by analyzing mice with a T cell–specific deletion of PTEN. Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice developed thymic lymphomas, but before the onset of tumors, they showed normal thymic cellularity. To reveal a regulatory role of PTEN in proliferation of developing T cells we have crossed PTEN-deficient mice with mice deficient for interleukin (IL)-7 receptor and pre–T cell receptor (TCR) signaling. Analysis of mice deficient for Pten and CD3γ; Pten and γc; or Pten, γc, and Rag2 revealed that deletion of PTEN can substitute for both IL-7 and pre-TCR signals. These double- and triple-deficient mice all develop normal levels of CD4CD8 double negative and double positive thymocytes. These data indicate that PTEN is an important regulator of proliferation of developing T cells in the thymus.

Keywords: PI-3K, thymus, Cre-LoxP, IL-7 receptor, pre–T cell receptor

Introduction

T cell development proceeds through various well-defined transitional cellular stages. T cell progenitors are negative for CD4, CD8, and CD3 and can be subdivided in four subpopulations on the basis of CD44 (Pgp-1) and CD25 (IL-2 receptor α-chain) surface expression (1). The most primitive of these CD4−CD8− (double negative [DN]) express CD44 and are negative for CD25 (DN1). These cells differentiate further into the intermediate DN stages with the phenotypes CD44+CD25+ (DN2) and CD44−CD25+ (DN3). TCRβ rearrangements are initiated in the CD44+ CD25+ DN2 stage. When these rearrangements are successful, the translated TCRβ protein forms a pre-TCR complex with the pTα chain and signals emanating from this receptor result in survival and proliferation of TCRβ-expressing cells (2, 3). As a consequence of β-selection, the CD44−CD25+ cells lose CD25, acquire CD2 and CD5 (4), and rapidly differentiate through an intermediate CD4− CD8+, immature (TCRlow) single positive (ISP) stage, to the CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP) stage.

In the early stages of T cell development, these cells go through two waves of proliferation: one mediated by the cytokines IL-7 and stem cell factor and the other by triggering of the pre-TCR complex. IL-7 and stem cell factor control the proliferation of the two first stages, DN1 and DN2, and survival of the DN3 cells (5–7). Pre-TCR triggering induces a second wave of extensive proliferation of pre–T cells. Recently, we documented that phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI-3K) is involved in IL-7–mediated cell survival because PI-3K associates with the IL-7Rα chain and a dominant-negative mutant of the p85 chain strongly inhibited T cell development in a fetal thymic organ culture (8). PI-3K converts phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-biphosphate (PtdIns[4,5]P2) to phosphatidylinositol-(3,4,5)-triphosphate (PtdIns[3,4,5]P3), which can bind pleckstrin homology domain-containing intracellular enzymes, including phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK-1), Akt/protein kinase B (PKB), and TEC family kinases such as IL-2–inducible T cell kinase (Itk) in T cells and Bruton agammaglobulinaemia tyrosine kinase in B cells. PDK-1 phosphorylates Akt/PKB, which seems to be an important player in the regulation of cell survival of thymocytes and mature T cells (9). Overexpression of a constitutive active mutant of Akt/PKB results in elevated levels of the antiapoptotic molecule Bcl-XL and enhanced NF-κB activation through accelerated degradation of the inhibitory molecule IκBα in both thymocytes and peripheral T cells (9). The PI-3K–Akt signal transduction pathway is counteracted by the phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN), whose lipid phosphatase activity is associated with tumor suppression (10). PTEN removes the D3 phosphate from PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and negatively regulates survival signaling mediated by Akt/PKB and other downstream targets of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (for review see references 11–13). Thus, PTEN might be involved in the control of proliferation and survival in early T cells. An absence of PTEN leads to an increase of the basal levels of PtdIns (3,4,5)P3 and, hence, to a sustained signaling through mediators that are activated by PtdIns(3,4,5)P3.

Pten −/− null mutant knockout mice have been generated in other laboratories (14, 15). These mice die during early embryogenesis, precluding any assessment of the role of PTEN in the development of T cells. Pten heterozygous mice have increased spontaneous tumor incidence (15), lymphoid hyperplasia development, and display autoimmune disorders (16). The fact that some spontaneous tumors were of T cell origin suggested a role for PTEN in the control of T cell survival and proliferation (17). To study the role of PTEN in T cell development in more detail, Suzuki et al. generated mice in which one allele of Pten was deleted and the other floxed and crossed these Pten flox/− with transgenic Lck-Cre animals to obtain mice with a T cell–specific PTEN deletion (17). These Pten flox/− Lck-Cre mice developed CD4+ T cell lymphomas (17). Before the onset of lymphomas, the cellularity of the thymus was somewhat increased. This may be in part caused by a defect in negative selection because loss of PTEN resulted in survival of HY-specific TCR transgenic cells in a negative-selecting background (17). Pten flox/− Lck-Cre mice showed elevated numbers of B cells, autoantibody production, and hypergammaglobulinemia, and in these mice increased numbers of CD4+ T cells were present that were hyperproliferative, autoreactive, and secreted high levels of cytokines. The effect of Pten deletion on early stages of T cell development was not investigated in the paper by Suzuki et al. (17).

The strategy of generating T cell–specific Pten −/− mice followed by Suzuki et al. (17) has as disadvantage that non–T cells have decreased levels of PTEN. This may have confused the analysis of these Pten flox/− Lck-Cre mice because Pten heterozygous mice show lymphoid hyperplasia and autoimmune disease features (16). In the present work, we generated Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice, which allowed us to analyze PTEN deficiency in T cell development, avoiding the problem of decreased PTEN levels in non–T cells. Using these mice, we examined the possibility that PTEN is involved in survival and proliferation of T cells at early stages of development by analyzing the thymuses of young Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice before the appearance of T cell lymphomas and of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre embryos. These analyses suggested an involvement of PTEN in the control of survival and proliferation of early T cell precursors. By analyzing crosses of the Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice with mice deficient for the γ common (γc) chain, CD3γ, or RAG2, in which proliferation of pre–T cells and β-selection, respectively, are perturbed, we observed that deletion of PTEN substitutes for both IL-7R and pre-TCR signaling.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Mice.

The conditional targeting vector and the generation of mice carrying the Pten flox allele by blastocyst microinjection have been described previously (18). To generate T cell–specific Pten-deficient mice, Pten flox/+ mice were crossed with Lck-Cre transgenic mice (provided by Merck; reference 19). Offspring carrying Lck-Cre and the floxed Pten mutation on both alleles (Pten flox/floxLck-Cre), Lck-Cre and the floxed Pten mutation on one allele (Pten flox/+ Lck-Cre), and Lck-Cre and the wild-type Pten gene (Pten +/+ Lck-Cre) were used for analysis as homozygous mutant, heterozygous mutant, and wild-type mice, respectively. The mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in the animal colony of the Netherlands Cancer Institute. CD3γ− (20), γc-deficient (21) and Rag2 −, γc–double deficient (22) mice were generated at the Netherlands Cancer Institute and have been described in detail previously. Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice were crossed with CD3γ-deficient or Rag2 − , γc–double deficient mice to generate the various double and triple deficient mice.

PCR Analyses of Genotypes.

Genomic DNA was isolated from tail clippings and amplified by PCR following a standard protocol. Sense primer (5′-GCCTTACCTAGTAAAGCAAG-3′) and antisense primer (5′-GGCAAAGAATCTTGGTGTTAC-3′) were used to detect the Pten flox allele, and sense primer (5′-GCACGTTCACCGGCATCAAC-3′) and antisense primer (5′-CGATGCAACGAGTGATGAGGTTC-3′) were used to detect the Lck-Cre transgene. Thermocycling conditions consisted of 31 cycles of 60 s at 94°C, 30 s at 58°C, and 30 s at 72°C. Reactions contained 200 ng of template DNA, 0.5 μM of primers, 100 μM dNTPs, 9% glycerol, 2.5 U Taq polymerase, 1.8 mM MgCl2, and PCR buffer (GIBCO BRL and Invitrogen) in a 25-μl volume. Amplified fragments of 230 bp (wild type), 280 bp (Pten flox/flox), and ∼350 bp (Cre), respectively, were obtained. Genotype analyses of CD3γ-deficient, γc-deficient, and Rag2 − , γc–double deficient mice have been described previously (20, 21, 23).

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblot.

For analysis of PTEN expression, 20 × 106 thymocytes from 4-wk-old Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre, Pten flox/+ Lck-Cre, or wild-type mice were lysed in lysis buffer containing 1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics). To be able to detect phosphorylated proteins, 50 mM NaF and 1 mM Na3VO4 were included in the lysis buffer. 30 μg of the soluble fractions was loaded on a 10% polyacrylamide gel in reducing conditions. After transfer on nitrocellulose membrane (ProtranR), the presence of PTEN protein was detected with the mouse monoclonal antibody specific for the COOH-terminal part of the protein (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). To confirm equal loading, membranes were stripped using strip buffer (625 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, and 100 mM 2-mercapto-ethanol) and stained with antiactin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). For analysis of Akt/PKB and Itk phosphorylation and Tec expression, thymocytes from 5- or 14-wk-old Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice or control (Pten flox/+ Lck-Cre or wild type) mice were lysed in the aforementioned lysis buffer. Unstimulated or CD3-stimulated Jurkat T cells were included as controls. The anti–human CD3 mAb 289 has been described previously (24). To detect Tec expression and phosphorylation of Akt/PKB, 20 × 106 thymocytes or 106 control Jurkat T cells per lane were analyzed. The anti-Tec rabbit polyclonal antiserum has been described previously (25). The antibodies specific for Akt/PKB and Akt/PKB phosphorylated at serine473 were obtained from New England Biolabs, Inc. For immunoprecipitation of Itk with the antibody 2F12 (a gift from L.J. Berg, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA), 15 × 107 thymocytes or 107 control Jurkat T cells were used. Phospho-Itk was visualized with the antiphosphotyrosine antibody 4G10 (Upstate Biotechnology).

Immunoprecipitated proteins were washed three times in lysis buffer and boiled in reducing SDS gel sample buffer for 3 min. Samples were resolved by 9% SDS-PAGE standard gels, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore), and the membrane was probed with specific antibodies. To visualize membrane-bound antibodies, relevant horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibodies (all obtained from DakoCytomation) and the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce Chemical Co.) were used.

Flow Cytometry Analysis.

All monoclonal FITC, PE, allophycocyanin- (APC), cychrome-5 (Cy-5)–, peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)–, or APC–Cy-7–conjugated antibodies used for standard analysis were obtained from BD Biosciences and used in three-, four-, or five-color staining analysis. For CD44, CD25 staining in CD4−CD8− cells, CD44 FITC was used in combination with CD25 PE. For CD44, CD25 staining in CD3−CD4−CD8− lineage− cells, CD44 Cy-5 was used in combination with CD25 APC. The polyclonality of the T cell repertoire was analyzed with monoclonal antibodies specific for Vβ2, Vβ3, Vβ5, Vβ6, Vβ8.1/8.2, Vβ8.3, Vβ9, Vβ10, and Vβ13 (labeled with PE). Intracellular staining for TCRβ and CD3ɛ was performed using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit obtained from BD Biosciences. For analysis of apoptosis, 5 × 104 E16 thymocytes from Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre or Pten flox/+ Lck-Cre embryos per well of a 96-well plate were incubated in Iscove's medium supplemented with 8% FCS at 37°C for 2 d before analysis. Cells were stained for annexin V and 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) (both obtained from BD Biosciences). The stained cells were analyzed with a FACSCalibur or with a LSRII (Becton Dickinson) using CELLQuest and FACSDiva software.

Results

Phosphorylated Akt/PKB in the Thymus of Ptenflox/floxLck-Cre Mice.

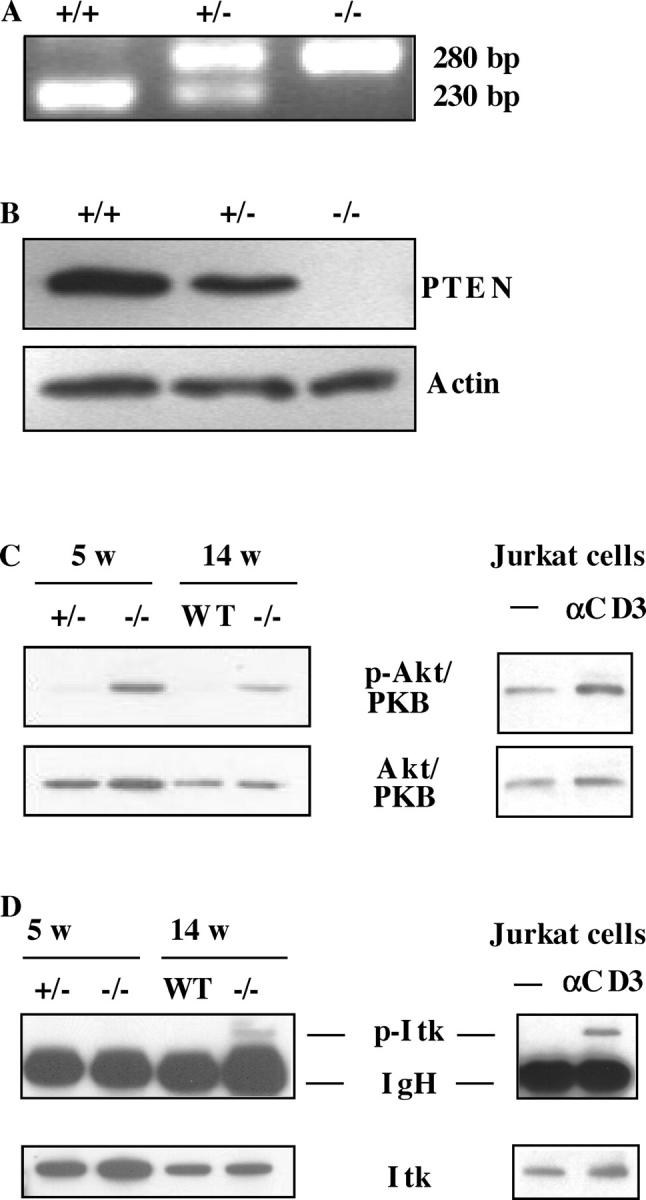

T cell–specific Pten-deficient mice (Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice) were generated by crossing Pten flox/flox mice (18) with Lck-Cre transgenic mice (19). Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice were born alive and appeared healthy. Genomic PCR of tail DNA showed the amplification of a 280-bp band corresponding to the floxed allele (Fig. 1 A). The deletion of Pten exon 5 encoding the phosphatase domain of PTEN (26) in Pten flox/flox mice crossed with Lck-Cre mice was confirmed by Western blotting. The expected 55-kD band was detected in the thymus of wild-type and heterozygous mice, but was absent in the thymus of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice (Fig. 1 B).

Figure 1.

The absence of PTEN in thymocytes results in constitutive activation of Akt/PKB, and a constitutive phosphorylation of Itk appears only when the mice are developing tumors. (A) PCR analysis of genomic tail DNA derived from 3-wk-old wild-type, heterozygote, and homozygote Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice. (B) Western blot analysis of the PTEN protein in the thymus of 4-wk-old homozygote Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre (n = 3) mice, compared with control (wild type, n = 3, and heterozygote, n = 3) mice. Actin staining was performed to confirm equal loading. (C) Western blot analysis of Akt/PKB and phospho-Akt/PKB in the thymus of 5-wk-old (n = 3) or 14-wk-old (n = 2) homozygote Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice, compared with control (wild type or heterozygote, n = 3 for each time point) mice. As a control, unstimulated (−) or CD3-stimulated (CD3) Jurkat T cells have been used. Akt/PKB and phospho-Akt/PKB were visualized by Western blotting with the relevant antibodies using 20 × 106 cells per lane (for thymocytes) or 106 cells per lane (for Jurkat T cells). The blots are representative for three separate experiments. (D) Western blot analysis of Itk and phospho-Itk in the thymus of 5-wk-old (n = 3) or 14-wk-old (n = 2) homozygote Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice, compared with control (wild type or heterozygote, n = 3 for each time point) mice. As a control, unstimulated (−) or CD3-stimulated (CD3) Jurkat T cells have been used. For immunoprecipitation of Itk with the antibody 2F12, 15 × 107 cells (for thymocytes), or 107 cells (for Jurkat T cells) were used. Phospho-Itk was visualized by Western blotting with the antiphosphotyrosine antibody 4G10. The blots are representative for three separate experiments.

Conversion of PtdIns(4,5)P2 to PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 by PI-3K creates binding sites for PH domain proteins Akt/PKB, Tec, and Itk, which may result in activation of these enzymes. Because the absence of PTEN causes sustained PI-3K signaling, it is possible that one or more of these PH domain enzymes are constitutively activated in the thymus of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice. Therefore, we compared the phosphorylation of Akt/PKB, Itk, and Tec in thymocytes of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre and in Pten flox/+ Lck-Cre or wild-type mice. As a control, we included the human PTEN-deficient T cell line Jurkat (27), incubated or not with anti-CD3 antibody. Fig. 1 C demonstrates that the thymus of both 5-wk-old Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice that had no signs of tumors and tumor-bearing 14-wk-old Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice contained much higher levels of phosphorylated Akt/PKB than the thymus of heterozygous or wild-type control littermates. In contrast, almost no phosphorylated Itk (Fig. 1 D) or Tec (not depicted) could be detected in the thymus of 5-wk-old Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice. However, some phosphorylated Itk was observed in thymic tumor-bearing 14 wk-old mice. These data clearly indicate that the absence of PTEN leads to an increase of basal PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels in the thymus, resulting in an enhanced Akt/PKB phosphorylation.

Development of Lymphomas.

To determine the impact of the Pten mutation, 20 Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice (10 males and 10 females) presenting a T cell–specific deletion were followed during their development. The first clinical signs of tumor formation were observed in some mice at 6–7 wk, and all the mice died within 17 wk (unpublished data).

The thymuses of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice were analyzed before 6 wk of age. Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice analyzed at 1–6 wk did not show any signs of tumor formation. Importantly, thymus weight; thymocyte number; CD3, CD4, and CD8 phenotypes; and TCRVβ diversity of thymocytes from Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice before 6 wk of age were completely comparable to those of Pten +/+ Lck-Cre mice (unpublished data), indicating that before the onset of lymphomas the PTEN deficiency does not lead to thymus hypercellularity.

Early T Cell Differentiation in Ptenflox/floxLck-Cre Mice.

To investigate the possibility that PTEN deletion affects T cell development before the DP stage, we analyzed the DN compartment in thymocytes of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre thymuses with antibodies against CD44, CD25 after exclusion of cells that express CD4 and CD8, TCRγδ and NK (DX5) cells, granulocytes and plasmacytoid DCs (GR1), macrophages (MAC1), and B lymphocytes (B220). We frequently observed an increase in the percentage of CD44−CD25− DN4 thymocyte population in Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice compared with heterozygous or wild-type mice, but these differences were not statistically significant (unpublished data).

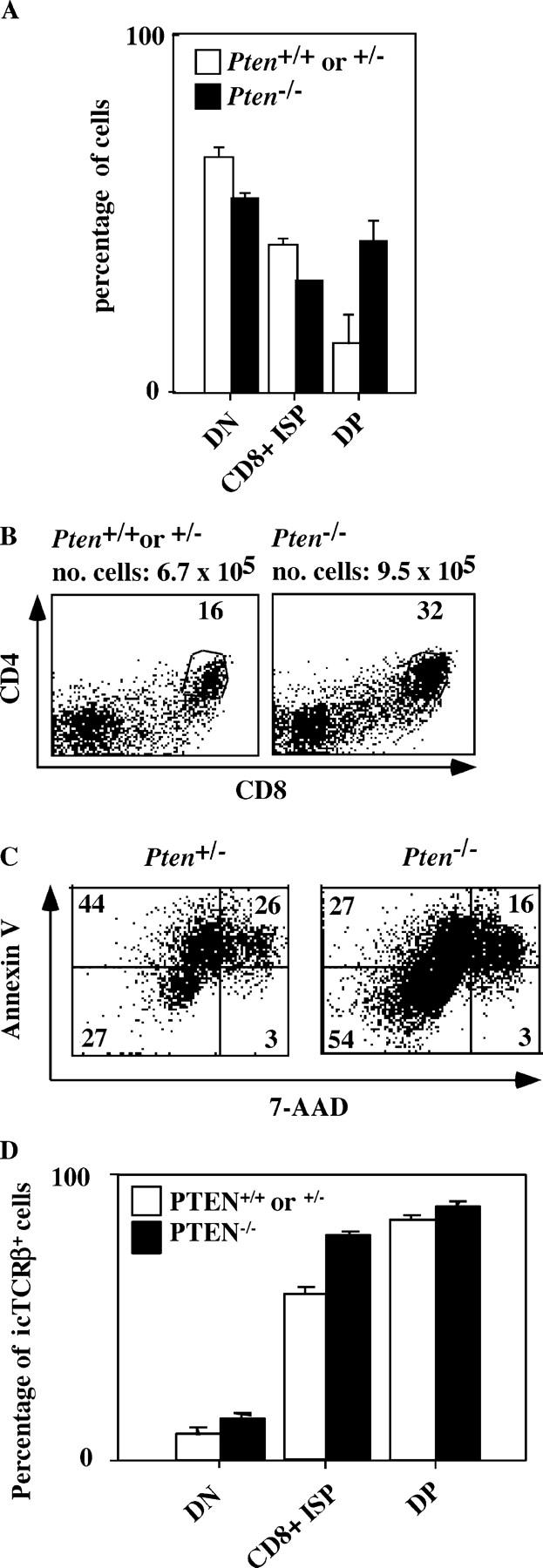

Thus, in the steady state thymus, no significant differences between Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre and heterozygous and wild-type animals were observed with regard to the thymus size and distribution of various CD4 and CD8, DN, DP, and single positive (SP) populations. This was unexpected in view of the role of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 in cell survival and proliferation and, in particular, in IL-7–mediated expansion of DN thymocytes (8). Therefore, we considered the possibility that Pten deletion affects the formation of the DP compartments during ontogeny. An analysis of DP thymocytes in Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre thymuses at day E16, when the thymus is being generated, revealed that the thymuses of E16 Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre embryos have 1.8–6-fold more DP cells (mean calculated from three Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre and four Pten flox/+ Lck-Cre embryos) as compared with thymuses of heterozygous or wild-type embryos (Fig. 2, A and B), suggesting that the absence of PTEN results in accelerated generation of DP thymocytes during ontogeny. To obtain information about the underlying mechanism, we tested the viability of the fetal thymocytes after 2 d of culture in Iscove's medium plus 8% FCS. After the incubation, the cells were stained with annexin V and 7-AAD and analyzed by FACS (Fig. 2 C). The average number of viable cells in the cultured Pten −/− thymocytes (48.3 ± 8.5, n = 4) was significantly higher than in the cultured control Pten +/− thymocytes (26.4 ± 4.5, n = 3). These data suggest that the absence of PTEN confers a survival advantage to embryonic thymocytes. Loss of PTEN induces survival and proliferation of TCRβ− DP cells in mice compromised in pre-TCR signaling (see Expansion of icTCRβ− DP Thymocytes in Ptenflox/floxLck-Cre × CD3γ2/2 Mice). These TCRβ− cells are in wild-type thymus eliminated after β-selection, but may survive and proliferate in embryonic Pten −/− thymus. To address the question of whether the increase in DP cell numbers was due to a selective expansion of DP cytoplasmic (ic)TCRβ− cells, we analyzed the expression of icTCRβ in the embryonic Pten −/− and Pten +/− immature single positive (ISP) and DP cells (Fig. 2 D). The percentages of icTCRβ+ cells were slightly higher in the Pten −/− (58 ± 2.2) than in the Pten +/− (78 ± 0.7) ISP compartment. However, the percentages of icTCRβ+ cells in the DP compartment were similar in both groups of embryos (84 ± 1.8 of Pten −/− and 88.5 ± 1.3 of Pten +/− DP cells; Fig. 2 D). Thus, although we observed some increased survival of icTCRβ− cells in the ISP compartment of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre embryos, the increase in DP cells observed in Pten −/− embryonic thymus is not caused by a selective expansion of TCRβ− DP cells.

Figure 2.

The absence of PTEN in thymocytes results in an accelerated generation of DP thymocytes during ontogeny. (A) Percentages of double negative (DN; CD4−CD8−), immature single positive (ISP; CD8+), and double positive (DP; CD4+CD8+) thymocytes of E16 old homozygote Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre (black bars, n = 3) or control (heterozygote or wild type; white bars, n = 4) embryos as determined by flow cytometry. (B) Flow cytometry of embryonic thymocytes. CD4CD8 staining of E16 old homozygote (Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre) or control (heterozygote or wild type) embryos. Numbers indicate percentages of gated populations. The total cell number mean is indicated for homozygote Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre (n = 3) or control (heterozygote or wild type; n = 4) embryos. (C) Flow cytometry of embryonic thymocytes after 2 d of culture in Iscove's medium supplemented with 8% FCS. 7-AAD and annexin V staining of E16 old homozygote Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre (n = 4) or control (heterozygote; n = 3) embryos. Numbers indicate percentages of gated populations. (D) Percentages of icTCRβ+ DN, ISP, and DP thymocytes of E16 old homozygote Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre (black bars, n = 4) or control (heterozygote; white bars, n = 3) embryos as determined by flow cytometry.

Loss of Pten Rescues Thymic Cellularity in CD3γ−/− Mice.

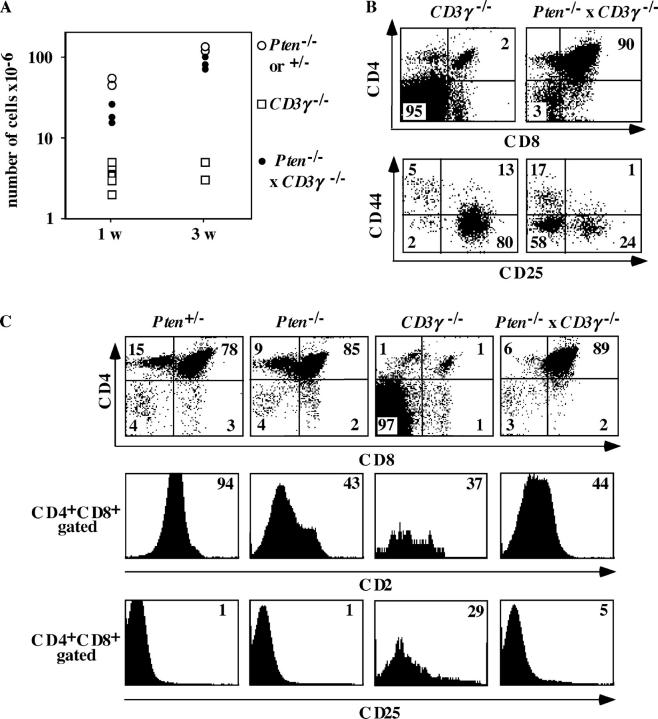

One explanation for the high numbers of DP thymocytes observed in E16 Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mouse embryos was that elevated PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels stimulate differentiation, cell survival, and/or proliferation around the β-selection checkpoint. To test this, we crossed Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice with CD3γ−/− mice that have a small thymus due to a poor capacity of inducing β-selection (20). Strikingly, the number of thymocytes in mice deficient for both PTEN and CD3γ were increased 3–6-fold at 1 wk of age (15–30 × 106 cells in the double deficient mice vs. 5 × 106 in CD3γ−/−) to >20-fold (100–150 × 106 cells in Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− mice) at 3 wk of age compared with CD3γ−/− mice (Fig. 3 A). Analysis of CD4/CD8 distribution in these mice revealed that the percentages of DP cells in the thymus of mice deficient for both PTEN and CD3γ were increased 40-fold compared with those in CD3γ−/− and similar to those of wild-type mice (Fig. 3 B, top). In addition, the percentages of DN4 thymocytes were strongly increased in the Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− mice (58% compared with 2% in CD3γ−/− mice; Fig. 3 B, bottom). These data indicate that the loss of PTEN completely neutralized the effect of CD3γ deficiency on the generation of DN4 cells and the DP thymocytes.

Figure 3.

The absence of PTEN in thymocytes can rescue the β-selection defect in CD3γ−/− mice. (A) Thymic cellularity of 1- or 3-wk-old Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− mice (n = 6) compared with Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre or Pten +/− (n = 4) and CD3γ−/− (n = 8) mice. (B) Flow cytometry of thymocytes. CD4CD8 and CD44, CD25 staining of 3-wk-old CD3γ−/− (n = 3), or Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− mice (n = 4) mice. Numbers in quadrants indicate percentages of each population. Note that CD25 and CD44 were analyzed after gating on CD4−CD8− thymocytes. The gates were set to include 99% of the control, isotype-stained cells of each sample in the negative quadrant. (C) Flow cytometry of thymocytes. CD4CD8 staining of 3-wk-old control (heterozygote; n = 3), Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre (n = 4), CD3γ−/− (n = 4), or Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− (n = 4) mice. Numbers in quadrants indicate percentages of each population. CD2 and CD25 expression are analyzed on CD4+CD8+ thymocytes. Numbers in histogram plots indicate percentages of each positive population.

It has been documented that CD25 is down-regulated and CD2 is up-regulated upon β-selection (4). To investigate whether PTEN deficiency affects up-regulation of CD2 and down-regulation of CD25, we examined DP thymocytes for expression of these antigens. Fig. 3 C demonstrates that CD2 was expressed on 40% of the DP thymocytes of both Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− and CD3γ−/− mice. To our surprise, we observed that CD2 was also diminished in DP thymocytes of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre. This effect was independent of the age of the animal because we also observed a lower CD2 expression in DP of E16 thymocytes and thymocytes of 1-wk-old mice (unpublished data). Thus, loss of PTEN by itself results in diminished up-regulation of CD2 after β-selection. The mechanism underlying this effect remains to be investigated. We observed that CD25 was absent on DP thymocytes of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre and Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/−, whereas this antigen is expressed on 28% of the DP thymocytes of CD3γ−/− mice (Fig. 3 C), indicating the loss of PTEN in CD3γ−/− mice restores down-regulation of CD25 in DP thymocytes.

Expansion of icTCRβ− DP Thymocytes in Ptenflox/floxLck-Cre × CD3γ−/− Mice.

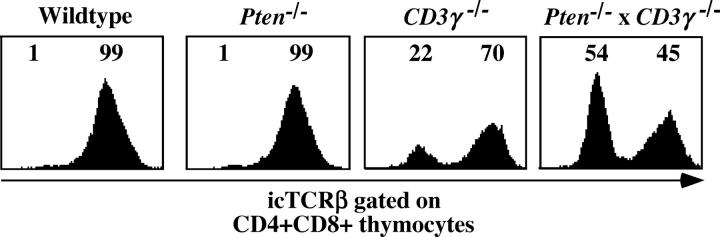

There were two possible explanations for the dramatic rise in DP cells in the thymus caused by the deletion of Pten in CD3γ−/− mice. One was that the absence of PTEN results in hyperresponsiveness to pre-TCR triggering and, hence, overrides diminished pre-TCR signaling caused by the absence of the CD3γ protein in the pre-TCR complex. Activation of T cells through the mature TCR results in activation of PI-3K (28) and Akt/PKB (9, 29, 30). Although there is no evidence yet that triggering of the pre-TCR results in activation of PI-3K and Akt/PKB, it was possible that increased basal levels of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 could amplify the suboptimal pre-TCR signal in CD3γ−/− mice. The second explanation was that PTEN deficiency led to survival and proliferation not only of those cells that undergo β-selection but also of those that are normally eliminated during β-selection. The first explanation predicted that the majority of the DP cells in the thymus of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− mice express TCRβ protein. If the second explanation was correct, we expected that many of the DP cells lack TCRβ protein. Assuming that 2/3 of the rearrangements at one TCRβ locus are nonproductive and 2/3 at the second, 4/9 of the cells are eliminated (2). In the case that those cells were not eliminated but survived, we would expect ∼45% TCRβ− cells. To check this, we performed intracytoplasmic (ic) staining with anti-TCRβ antibodies (Fig. 4 and Table I). As expected, we observed that >99% of the DP thymocytes in wild-type mice are icTCRβ+ (Fig. 4 and Table I). Similar percentages were observed in the thymus of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice (Fig. 4 and Table I). The majority of the DP cells in CD3γ−/− mice (61–88%) were TCRβ+, indicating that the few DP cells in these mice were subjected to β-selection. This could have been due to signaling through the incomplete CD3δ, ɛ–containing pre-TCR complex (31), which may induce selective survival but no proliferation of cells expressing a functional TCRβ/pTα dimer. In contrast, in Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− mice only 23–46% of the DP cells were TCRβ+ (Fig. 4 and Table I). The increase in icTCRβ− cells was not due to a preferential outgrowth of TCRγδ+ cells because no icTCRδ+ DP cells were observed in the thymus of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− mice (unpublished data). These data suggest that in the absence of PTEN, thymocytes lacking productive TCRβ rearrangements are able to survive and to expand over time in the DP stage. The data presented in Fig. 4 suggests that the absence of PTEN results in a selective outgrowth of TCRβ− DP thymocytes. However, inspection of the absolute numbers of icTCRβ+ and icTCRβ− DP thymocytes in Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− and CD3γ−/− mice indicated that the numbers of icTCRβ+ DP thymocytes were considerably increased in the absence of PTEN (Table I). At 1 wk of age, the numbers of icTCRβ+ DP cells in the thymuses of both mice were similar; however, at 3–4 wk of age, the numbers of icTCRβ+ DP thymocytes in the Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− mice were much higher (13 × 106 and 30 × 106, respectively) than in the CD3γ−/− mice (0.64 × 106 and 0.08 × 106, respectively). Thus, although the proportion of the icTCRβ+ cells in the DP compartment decreased as a result of Pten deletion in CD3γ−/− background, the absolute numbers of these cells increased as compared with the numbers of DP thymocytes in CD3γ−/− mice with normal PTEN levels.

Figure 4.

The absence of PTEN in CD3γ−/− thymocytes results in a strong increase of the percentages of CD4+CD8+ icTCRβ− cells. Flow cytometry of thymocytes. Intracellular TCRβ staining of 3-wk-old control (wild type; n = 4), Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre (n = 4), CD3γ−/− (n = 4) or Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− (n = 4) mice. Intracellular TCRβ expression is analyzed on CD4+CD8+ DP thymocytes. Numbers in histogram plots indicate percentages of negative and positive populations.

Table I.

Thymus Cell Counts, Percentages, and Absolute Cell Numbers of CD4+CD8+icTCRβ+ or CD4+CD8+icTCRβ− Cells in Wild Type, Ptenflox/floxLck-Cre, CD3γ−/−, and Ptenflox/floxLck-Cre × CD3γ−/− Mice

| Age | Genotype | n | Thymus cellularity |

CD4+CD8+

total |

CD4+CD8+

icTCRβ+ |

CD4+CD8+

icTCRβ+ |

CD4+CD8+

icTCRβ− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wk | no. × 10−6 | % | % | no. × 10−6 | no. × 10−6 | ||

| 1 | wild type | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Pten−/− | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| CD3γ−/− | 9 | 4.4 ± 1.4 | 12 ± 4.4 | 88 ± 2.7 | 0.48 ± 0.26 | 0.07 ± 0.04 | |

| Pten−/− × CD3γ−/− | 1 | 3.4 | 26 | 46 | 0.40 | 0.47 | |

| 2 | wild type | 7 | 96 ± 20 | 81 ± 5.6 | 99 ± 0.1 | 80 ± 15 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| Pten−/− | 4 | 108 ± 10 | 81 ± 6.8 | 99 ± 0.1 | 88 ± 13 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | |

| CD3γ−/− | 7 | 12 ± 2.4 | 8.7 ± 7.7 | 58 ± 5.1 | 0.64 ± 0.56 | 0.44 ± 0.41 | |

| Pten−/− × CD3γ−/− | 3 | 56 ± 23 | 83 ± 1.5 | 27 ± 9.1 | 13 ± 7.1 | 34 ± 16 | |

| 4 | wild type | 3 | 144 ± 32 | 81 ± 0.9 | 99 ± 0.9 | 114 ± 23 | 2.0 ± 1.2 |

| Pten−/− | 2 | 162 ± 29 | 78 ± 3.3 | 99 ± 0.4 | 124 ± 27 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | |

| CD3γ−/− | 4 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 70 ± 7.0 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.03 ± 0.003 | |

| Pten−/− × CD3γ−/− | 3 | 180 ± 4.0 | 72 ± 5.0 | 23 ± 3.0 | 30 ± 5.3 | 100 ± 0.9 |

Loss of PTEN Rescues Thymic Cellularity in γc−/− Mice.

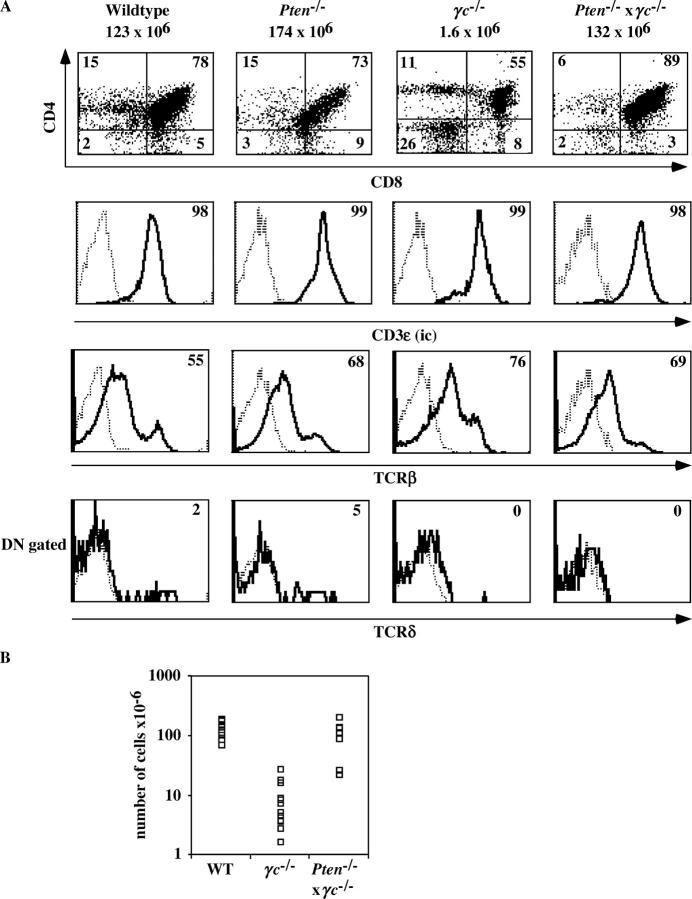

How did the icTCRβ− cells survive in Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− mice? One possibility was that PTEN deficiency mimicked the IL-7R signal, which is normally absent in wild-type nonselected DN3 cells. It has been established that IL-7 activates PI-3K in thymocytes (32). Moreover, PI-3K can associate with the IL-7Rα after engagement with IL-7 (33) and a dominant negative form of p85 inhibited T cell development (8), strongly suggesting that accumulation of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is critical for IL-7–mediated survival and proliferation of early T cell precursors. It might have been possible that the absence of PTEN, which catalyzes the reverse conversion of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 into PtdIns(4,5)P2 leading to elevated basic levels of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, would compensate for the loss of the IL-7R complex. To test this idea, we analyzed the thymus of γc −/− mice crossed with Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice. The absence of PTEN in a γc −/− background rescued thymic cellularity (Fig. 5 B) with normal percentages of various TCRαβ lineage thymocyte subsets (Fig. 5 A). Interestingly, TCRγδ cells were not rescued by the absence of PTEN in γc −/− mice (Fig. 5 A). IL-7 (34) and its receptor (35–37) are required for optimal rearrangements at the TCRγ locus and, thus, for differentiation of TCRγδ cells. Our observations indicate that PTEN deficiency compensates for the proliferative defect of TCRαβ lineage precursors caused by the absence of γc but not for the TCRγδ differentiation defect.

Figure 5.

The absence of PTEN compensates the thymic defect in γc −/− mice. (A) Flow cytometry of thymocytes for expression of CD4CD8, intracellular CD3ɛ, TCRβ, and TCRδ of 5 wk-old control (wild type), Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre, γc −/−, or Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × γc −/− mice. Numbers in quadrants indicate percentages of each population. Numbers in histogram plots indicate percentages of each positive population. The total number of thymocytes are indicated on top of the CD4/CD8 dotplots. The gates were set to include 99% of the control isotype-stained cells of each sample in the negative quadrant. (B) Thymic cellularity of 5-wk-old control (wild type or heterozygous; n = 6), γc −/− (n = 17), and Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × γc −/− mice (n = 10).

Loss of PTEN Reconstitutes Thymic Cellularity in Mice Doubly Deficient for RAG2 and γc.

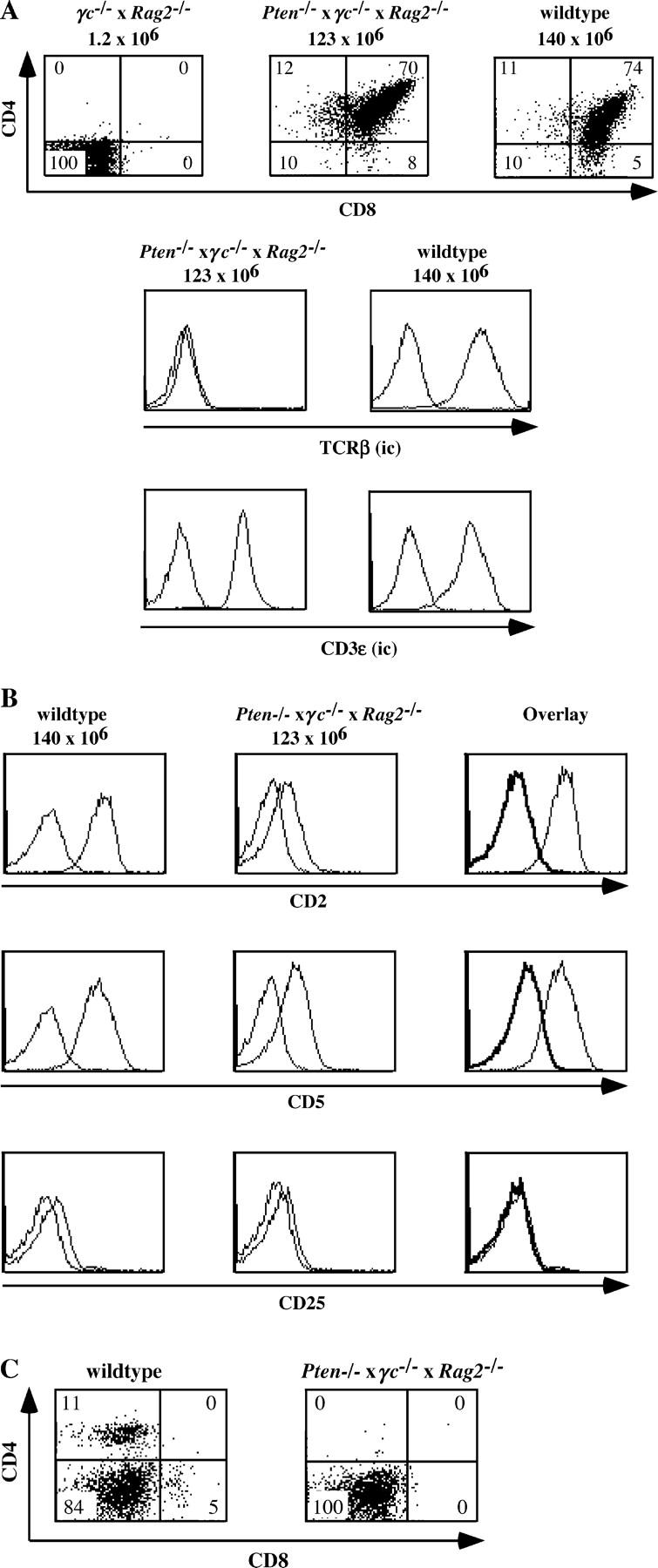

Our findings that loss of PTEN results in reconstitution of thymic defects caused by γc and CD3γ deficiencies may suggest that the increase in basal levels of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels by itself bypasses the proliferation-inducing signals emanating from the IL-7R and the pre-TCR. However, an alternative possibility was that PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels amplified the γc signal in CD3γ−/− mice and the pre-TCR signal in γc −/− mice. To distinguish between these possibilities, we investigated the effect of loss of PTEN on thymic cellularity in mice deficient for both RAG2 and γc. Because both the IL-7R complex and the pre-TCR are absent in these mice, the two most important external growth-promoting signals cannot be transmitted in the developing T cells. We analyzed three Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × γc −/− × Rag2 −/− mice from three different litters at the age of 4–5 wk. The thymuses of these three mice contained 50 × 106 (4 wk), 95 × 106 (5 wk), and 123 × 106 (5 wk) cells, respectively. The thymus phenotypes of these mice were identical. Fig. 6 A shows that loss of PTEN compensated for the loss of both γc and the pre-TCR with regard to the numbers of thymocytes. Most of the thymocytes in the Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × γc −/− × Rag2 −/− mice were DP (70%), but also some CD4+ and CD8+ SP cells could be observed (Fig. 6 A). As expected, the DP thymocytes expressed icCD3ɛ, but did not express cell surface CD3ɛ nor icTCRβ (Fig. 6 A and not depicted), confirming the absence of a pre-TCR and a mature TCR. Because the up-regulation of CD2 and CD5 and the down-regulation of CD25 are considered to be hallmarks of pre-TCR expression, we also analyzed the expression of CD2, CD5, and CD25. Fig. 6 B shows that CD2 and CD5 were only very slightly up-regulated and much less than in wild-type DP thymocytes. CD25 was not expressed on DP cells of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × γc −/− × Rag2 −/− mice. The DP cells of these mice expressed almost no CD69 (unpublished data), which was expected because the activation marker CD69 is only up-regulated as consequence of TCR-mediated positive selection. Despite the presence of small numbers of SP cells in the thymus of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × γc −/− × Rag2 −/− mice, no CD4+ or CD8+ cells could be found in the spleen of the these mice (Fig. 6 C). We conclude that the loss of PTEN resulted in proliferation of thymocytes and induction of CD4 and CD8 in the absence of IL-7R and pre-TCR signaling.

Figure 6.

Loss of PTEN compensates the thymic defect in γc −/− × Rag2 −/− mice. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of expression of CD4CD8, icCD3ɛ, and icTCRβ in thymocytes of 4–5 wk-old control (wild type; n = 11), γc −/− × Rag2 −/− (n = 1), and Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × γc −/− × Rag2 −/− (n = 3) mice. Numbers in quadrants indicate percentages of each population. The total numbers of thymocytes are indicated on top of the CD4/CD8 dotplots. The gates were set to include 99% of the control, isotype-stained cells of each sample in the negative quadrant. (B) Expression of CD2, CD5 and CD25 in CD4+CD8+ cells of 4–5-wk-old control (wild type; n = 11) and Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × γc −/− × Rag2 −/− (n = 3) mice. The cells were stained and expression of CD2, CD5 and CD25 were analyzed on CD4+CD8+ DP thymocytes. (C) Expression of CD4 and CD8 on spleen cells of 4–5 wk-old control (wild type; n = 11) and Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × γc −/− × Rag2 −/− (n = 3) mice. Numbers in quadrants indicate percentages of each population. The gates were set to include 99% of the control, isotype-stained, cells of each sample in the negative quadrant.

Discussion

In this work, we demonstrate a critical role of PTEN in regulation of survival and growth of developing T cells in the thymus. We have analyzed mice with a T cell lineage-specific PTEN deletion. In agreement with the observations of Suzuki et al. (17), we observed that all Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice developed T cell lymphomas. A comparison of wild-type and Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice before the onset of lymphomagenesis revealed no gross differences in thymic cellularity and distribution of various DN, DP, and SP populations. Using an independently made mouse strain with a T cell–specific loss of PTEN, Suzuki et al. also noted little effects on the phenotypes of thymocytes, but these investigators observed a modest hypercellularity of the thymus before the onset of lymphomagenesis (38). Our data indicate that loss of PTEN does not affect thymic cellularity and the distribution of CD4 and CD8 under steady state conditions. Thus, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels produced in wild-type mice are not rate limiting for optimal proliferation of developing T cells. However, we observed a higher number of DP cells in thymuses of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre E16 embryos compared with heterozygous or wild-type E16 embryos, suggesting that PTEN deficiency conferred a proliferative advantage to early pre–T cells before and/or after the β-selection checkpoint during ontogeny. To examine this, we introduced the Pten deletion in mice with deficiencies in IL-7R, pre-TCR signaling, or both. The size of the thymus was strongly increased in the absence of PTEN in either context, indicating the importance of sustained PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels for expansion of thymocytes at all stages of differentiation. The observation that the absence of PTEN compensated for the effect of γc deletion on thymic cellularity is consistent with the notion that PI-3K is pivotal for the IL-7–induced proliferation of pre–T cells (8). However, TCRγδ cells were not rescued. Assuming that the Lck-Cre transgene is also expressed in TCRγδ cells, our findings indicate that Pten deletion did not recapitulate all effects of the IL-7R. This was expected because the absence of TCRγδ cells in γc −/− mice is the result of inefficient rearrangements at the TCRγ locus (34–37), which is mediated in wild-type mice through activation of STAT5 by IL-7 (39, 40). However, we cannot formally exclude that in our mice the Lck-Cre transgene was not expressed in TCRγδ cells.

The deficiency of PTEN in CD3γ−/− mice and mice with a RAG2 deficiency eventually resulted in a numerical reconstitution of the thymus and high percentages of DP cells, indicating that the appearance of CD4 and CD8 is a consequence of increased PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels resulting from the loss of PTEN. Strikingly, we observed that the proportion of TCRβ− DP cells in the thymus of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− mice is much higher than in CD3γ−/− mice. These TCRβ− DP cells were also negative for icTCRδ, but expressed icCD3ɛ. Moreover, loss of PTEN also rescued the thymic cellularity in mice deficient for RAG2 and γc, which do not express a pre-TCR at all. These findings indicate that the absence of PTEN results in survival and expansion of early TCRαβ lineage cells that are normally eliminated during β-selection. It is important to note that, whereas the proportion of icTCRβ+ cells was decreased, the absolute numbers of these cells were increased in Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− mice compared with CD3γ−/− mice (Table I), indicating that the absence of PTEN in the thymus results in survival and expansion of cells both with productive (icTCRβ+) and unproductive TCRβ (icTCRβ−) rearrangements. We have observed that the absence of PTEN reconstituted thymic cellularity in γc −/− mice and, thus, compensated for the absence of the IL-7–mediated survival and proliferation signals.

These data may explain why PTEN deficiency leads to survival of icTCRβ− cells in the context of suboptimal pre-TCR signaling and suggests a physiological role of PTEN in β-selection. Approximately one third of TCRβ rearrangements at the first allele are successfully producing a full-length TCRβ protein (2). Assuming that one third of the cells that fail to successfully complete a TCRβ rearrangement at one allele complete a productive rearrangement at the second allele, five out of nine cells eventually produce a TCRβ protein, the rest being eliminated (2). It seems reasonable to assume that these cells die because of an absence of a survival signal. This implies that IL-7R signaling needs to be shut off in cells that failed to pass the β-selection. The currently accepted model holds that cells expressing a functional TCRβ–pTα complex are rescued from death by pre-TCR signaling and proliferate, whereas the nonselected cells, which do not receive a survival signal neither from the IL-7R nor from the pre-TCR will die.

A problem with this model is that, although the IL-7R is down-regulated in icTCRβ− DN4 cells compared with icTCRβ+ DN4 cells, there is still some IL-7R expressed on icTCRβ− DN4 cells (41), raising the question how IL-7R signaling is turned off in pre–T cells poised for elimination. We propose that PTEN shuts off a remaining IL-7–mediated survival signal and ensures that the pre–T cells that failed to complete productive rearrangements at the TCRβ locus cannot receive a survival signal and, thus, die by neglect. The observation of a dramatic expansion of DP cells in Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × γc −/− × Rag2 −/− mice is consistent with this model. However, it should be noted that we did not observe increased numbers of TCRβ− cells in DP Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre thymocytes compared with wild-type cells.

To account for this observation in the context of our hypothesis, we propose that the signal induced by an intact pre-TCR results in a much higher rate of proliferation than induced by the mere absence of PTEN. Because of the difference in proliferation rate, the DP cells expressing an intact pre-TCR in Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice preferentially filled the DP “niche,” whereas in Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × CD3γ−/− mice, the TCRβ+ cells did not have a proliferative advantage and hence the DP niche was filled with both TCRβ+ and TCRβ− cells. This notion is supported by the observation that the CD3γ deficiency was only fully compensated by the absence of PTEN 3 wk after birth (Fig. 4). Thus, before the first 2 wk after birth, PTEN-deficient thymocytes that undergo normal pre-TCR signaling had expanded much more than the PTEN CD3γ doubly deficient thymocytes in which pre-TCR signaling is compromised.

Our data indicate that the absence of PTEN sufficiently elevates basal levels of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 to mediate survival and proliferation of thymocytes before and after the β-selection point in the absence of external growth stimuli. Any signaling molecule that has a PH domain that preferentially binds to PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 can be involved in expansion of thymocytes observed in the Pten-deficient CD3γ−/−, γc −/−, and Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × γc −/− × Rag2 −/− thymuses. PDK-1 has an NH2-terminal catalytic domain and a COOH-terminal PH domain that binds to PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 with high affinity. PDK-1 appears to be a critical mediator because T cell–specific deletion of this enzyme results in a strong inhibition at the transition of DN to DP thymocytes (42). PDK-1 is a “master” kinase that phosphorylates residues in the activation loops of AGC superfamily serine/threonine kinases, including the PI-3K–controlled serine kinases Akt/PKB, which are corecruited to PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, and S6 kinase 1. Indeed, Akt/PKB is phosphorylated in the thymus of Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre mice, indicating that PDK-1 is active. At least 13 substrates of Akt/PKB have been identified so far and can be separated into two main subsets: regulators of survival/apoptosis and cell cycle regulators (for review see reference 43), giving to Akt/PKB an important role in the control of the survival/proliferation of different cell types. Expression of a transgene encoding a constitutive active Akt/PKB (gagPKB) has been shown to improve survival of thymocytes and mature T lymphocytes (9). However, introduction of a transgene encoding another constitutively membrane-targeted Akt/PKB (myristoylated Akt/PKB) in γc −/− mice or in pre-TCR–deficient Rag2 −/− mice failed to reconstitute thymic cellularity in these animals (Di Santo, J., personal communication). Unless one assumes that myristoylated Akt/PKB, because of its forced membrane targeting, does not completely mimic the natural PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-recruited Akt/PKB in a thymic context, these data suggest that activated Akt/PKB by itself is not responsible for the generation of a full size thymus in Pten flox/flox Lck-Cre × γc−/− mice. Given the observations that the myristoylated Akt/PKB transgene failed to reconstitute thymic cellularity in γc −/− mice or in Rag2 −/− mice, it is unlikely that known targets of Akt/PKB as Bad and Caspase 9 are involved in the effect caused by the loss of PTEN. The antiapoptotic molecule Bcl-2, believed to be downstream of the IL-7 receptor (44, 45) and possibly induced in a PI-3K–dependent way, is likely not a critical element as transgenic overexpression of Bcl-2 is unable to rescue the CD3γ (46), RAG (44), or γc deficiencies (7, 21). We could not detect phosphorylation of another PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-regulated kinase, Itk, in PTEN−/− thymocytes before the onset of lymphomagenesis, arguing against a role of this enzyme. We did observe some phosphorylated Itk in the thymus of 14-wk-old thymic tumor-bearing mice, but the mechanism remains to be established.

Our data suggest that PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-dependent molecules other than Akt/PKB or Itk are involved in the growth-promoting effects of thymocytes. Possible candidates are the small GTPases Rac and Rho, which are influenced by PI-3K (47) and have been shown to affect growth of early T cell precursors (4, 48). Another possible mediator is the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) because rapamycin reduces the size of the thymus in the mouse (49) and inhibits transition of DN to DP cells in the rat thymus (50). Interestingly rapamycin interferes with GM-CSF signaling in DCs partly through down-regulation of the antiapoptotic molecule Mcl-1, indicating that in these cells, mTOR mediates expression of Mcl-1 (51). Recent data strongly suggest that Mcl-1 is involved in IL-7–mediated survival (52), but it is unclear whether Mcl-1 is involved in pre-TCR–mediated cell survival. Whether or not Mcl-1 levels are affected by the loss of PTEN is not yet known. Due to the complexity of the network of downstream signaling pathways that are connected to PI-3K and PTEN-dependent PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, determination of the exact downstream participants in the pathway that controls proliferation of T lineage cells during development will not be straightforward.

Given our observations and those of Hinton et al. indicating that PDK-1 deficiency strongly compromises proliferation and differentiation at the DN to DP transition (42), PDK-1 and PTEN may be considered to form a switch that functions as a major regulator of survival and proliferation of developing thymocytes. The absence of PTEN induces proliferation and is dominant over the apoptosis-inducing signals, which may be the reason why the PTEN deficiency leads to thymic tumors with a rapid onset.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. A. Kruisbeek and M. Haks for kindly providing the CD3γ−/− mice. We thank Drs A. Berns, B. Blom, J. DiSanto, and D. Cantrell for critically reading the manuscript. We would like to thank Dr. L.J. Berg for providing reagents.

This work was supported by an EEC fellowship contract no. HPMF-CT-1999-00057 (to M. Naspetti); by grants from the Netherlands Foundation for Cancer Research, no. NKI 2000-2279, and the Dutch National Research Organization (NWO), no. 901-08-093 (to H. Spits); and a grant “Equipe labellisée 2001” from the Ligne Nationale Contre le Cancer (to F. Garcon and J. Nunes).

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

T.J. Hagenbeek and M. Naspetti contributed equally to this work.

Abbreviations used in this paper: DN, double negative; DP, double positive; ISP, immature single positive; Itk, IL-2–inducible T cell kinase; PDK-1, phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1; PI-3K, phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase; PKB, protein kinase B; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10; SP, single positive.

References

- 1.Godfrey, D.I., and A. Zlotnik. 1993. Control points in early T-cell development. Immunol. Today. 14:547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mallick, C.A., E.C. Dudley, J.L. Viney, M.J. Owen, and A.C. Hayday. 1993. Rearrangement and diversity of T cell receptor beta chain genes in thymocytes: a critical role for the beta chain in development. Cell. 73:513–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Boehmer, H., I. Aifantis, J. Feinberg, O. Lechner, C. Saint-Ruf, U. Walter, J. Buer, and O. Azogui. 1999. Pleiotropic changes controlled by the pre-T-cell receptor. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 11:135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomez, M., V. Tybulewicz, and D.A. Cantrell. 2000. Control of pre-T cell proliferation and differentiation by the GTPase Rac-I. Nat. Immunol. 1:348–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim, K., C.K. Lee, T.J. Sayers, K. Muegge, and S.K. Durum. 1998. The trophic action of IL-7 on pro-T cells: inhibition of apoptosis of pro-T1, -T2, and -T3 cells correlates with Bcl-2 and Bax levels and is independent of Fas and p53 pathways. J. Immunol. 160:5735–5741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Offner, F., and J. Plum. 1998. The role of interleukin-7 in early T-cell development. Leuk. Lymphoma. 30:87–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodewald, H.R., C. Waskow, and C. Haller. 2001. Essential requirement for c-kit and common γ chain in thymocyte development cannot be overruled by enforced expression of Bcl-2. J. Exp. Med. 193:1431–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pallard, C., A.P. Stegmann, T. van Kleffens, F. Smart, A. Venkitaraman, and H. Spits. 1999. Distinct roles of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and STAT5 pathways in IL-7-mediated development of human thymocyte precursors. Immunity. 10:525–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones, R.G., M. Parsons, M. Bonnard, V.S. Chan, W.C. Yeh, J.R. Woodgett, and P.S. Ohashi. 2000. Protein kinase B regulates T lymphocyte survival, nuclear factor κB activation, and Bcl-X(L) levels in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 191:1721–1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myers, M.P., I. Pass, I.H. Batty, J. Van der Kaay, J.P. Stolarov, B.A. Hemmings, M.H. Wigler, C.P. Downes, and N.K. Tonks. 1998. The lipid phosphatase activity of PTEN is critical for its tumor supressor function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:13513–13518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantley, L.C., and B.G. Neel. 1999. New insights into tumor suppression: PTEN suppresses tumor formation by restraining the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:4240–4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Cristofano, A., and P.P. Pandolfi. 2000. The multiple roles of PTEN in tumor suppression. Cell. 100:387–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seminario, M.C., and R.L. Wange. 2003. Lipid phosphatases in the regulation of T cell activation: living up to their PTEN-tial. Immunol. Rev. 192:80–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stambolic, V., A. Suzuki, J.L. de la Pompa, G.M. Brothers, C. Mirtsos, T. Sasaki, J. Ruland, J.M. Penninger, D.P. Siderovski, and T.W. Mak. 1998. Negative regulation of PKB/Akt-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell. 95:29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Cristofano, A., B. Pesce, C. Cordon-Cardo, and P.P. Pandolfi. 1998. Pten is essential for embryonic development and tumour suppression. Nat. Genet. 19:348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Cristofano, A., P. Kotsi, Y.F. Peng, C. Cordon-Cardo, K.B. Elkon, and P.P. Pandolfi. 1999. Impaired Fas response and autoimmunity in Pten+/− mice. Science. 285:2122–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki, A., J.L. de la Pompa, V. Stambolic, A.J. Elia, T. Sasaki, I. del Barco Barrantes, A. Ho, A. Wakeham, A. Itie, W. Khoo, M. Fukumoto, and T.W. Mak. 1998. High cancer susceptibility and embryonic lethality associated with mutation of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in mice. Curr. Biol. 8:1169–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marino, S., P. Krimpenfort, C. Leung, H.A. Van Der Korput, J. Trapman, I. Camenisch, A. Berns, and S. Brandner. 2002. PTEN is essential for cell migration but not for fate determination and tumourigenesis in the cerebellum. Development. 129:3513–3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu, H., J.D. Marth, P.C. Orban, H. Mossmann, and K. Rajewsky. 1994. Deletion of a DNA polymerase beta gene segment in T cells using cell type-specific gene targeting. Science. 265:103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haks, M.C., P. Krimpenfort, J. Borst, and A.M. Kruisbeek. 1998. The CD3gamma chain is essential for development of both the TCRalphabeta and TCRgammadelta lineages. EMBO J. 17:1871–1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blom, B., H. Spits, and P. Krimpenfort. 1997. The role of the common gamma chain of the IL-2, IL-4, IL-7 and IL-15 receptors in development of lymphocytes: constitutive expression of Bcl-2 does not rescue the developmental defects in gamma common-deficient mice. Cytokines and Growth Factors in Blood Transfusion. C.T. Smit Sibinga, P.C. Das, and B. Löwenberg, editors. Kluwer Academic Publishers, London. 3–12.

- 22.Kirberg, J., A. Berns, and H. von Boehmer. 1997. Peripheral T cell survival requires continual ligation of the T cell receptor to major histocompatibility complex-encoded molecules. J. Exp. Med. 186:1269–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horton, R.M., P.I. Karachunski, and B.M. Conti-Fine. 1995. PCR screening of transgenic RAG-2 “knockout” immunodeficient mice. Biotechniques. 19:690–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nunes, J., S. Klasen, M. Ragueneau, C. Pavon, D. Couez, C. Mawas, M. Bagnasco, and D. Olive. 1993. CD28 mAbs with distinct binding properties differ in their ability to induce T cell activation: analysis of early and late activation events. Int. Immunol. 5:311–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang, W.C., M. Ghiotto, R. Castellano, Y. Collette, N. Auphan, J.A. Nunes, and D. Olive. 2000. Role of Tec kinase in nuclear factor of activated T cells signaling. Int. Immunol. 12:1547–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ali, I.U., L.M. Schriml, and M. Dean. 1999. Mutational spectra of PTEN/MMAC1 gene: a tumor suppressor with lipid phosphatase activity. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 91:1922–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seminario, M.C., P. Precht, R.P. Wersto, M. Gorospe, and R.L. Wange. 2003. PTEN expression in PTEN-null leukaemic T cell lines leads to reduced proliferation via slowed cell cycle progression. Oncogene. 22:8195–8204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ward, S.G., S.C. Ley, C. MacPhee, and D.A. Cantrell. 1992. Regulation of D-3 phosphoinositides during T cell activation via the T cell antigen receptor/CD3 complex and CD2 antigens. Eur. J. Immunol. 22:45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kane, L.P., V.S. Shapiro, D. Stokoe, and A. Weiss. 1999. Induction of NF-kappaB by the Akt/PKB kinase. Curr. Biol. 9:601–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lafont, V., E. Astoul, A. Laurence, J. Liautard, and D. Cantrell. 2000. The T cell antigen receptor activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-regulated serine kinases protein kinase B and ribosomal S6 kinase 1. FEBS Lett. 486:38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haks, M.C., T.A. Cordaro, J.H. van den Brakel, J.B. Haanen, E.F. de Vries, J. Borst, P. Krimpenfort, and A.M. Kruisbeek. 2001. A redundant role of the CD3 gamma-immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif in mature T cell function. J. Immunol. 166:2576–2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dadi, H.K., and C.M. Roifman. 1993. Activation of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase by ligation of the interleukin-7 receptor on human thymocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 92:1559–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Venkitaraman, A.R., and R.J. Cowling. 1994. Interleukin-7 induces the association of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase with the α chain of the interleukin-7 receptor. Eur. J. Immunol. 24:2168–2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laky, K., L. Lefrancois, F. von, U. Jeffry, R. Murray, and L. Puddington. 1998. The role of IL-7 in thymic and extrathymic development of TCR gamma delta cells. J. Immunol. 161:707–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maki, K., S. Sunaga, and K. Ikuta. 1996. The V-J recombination of T cell receptor-γ genes is blocked in interleukin-7 receptor–deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 184:2423–2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Durum, S.K., S. Candeias, H. Nakajima, W.J. Leonard, A.M. Baird, L.J. Berg, and K. Muegge. 1998. Interleukin 7 receptor control of T cell receptor γ gene rearrangement: role of receptor-associated chains and locus accessibility. J. Exp. Med. 188:2233–2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muljo, S.A., and M.S. Schlissel. 2000. Pre-B and pre-T-cell receptors: conservation of strategies in regulating early lymphocyte development. Immunol. Rev. 175:80–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki, A., M.T. Yamaguchi, T. Ohteki, T. Sasaki, T. Kaisho, Y. Kimura, R. Yoshida, A. Wakeham, T. Higuchi, M. Fukumoto, et al. 2001. T cell-specific loss of Pten leads to defects in central and peripheral tolerance. Immunity. 14:523–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ye, S.K., K. Maki, T. Kitamura, S. Sunaga, K. Akashi, J. Domen, I.L. Weissman, T. Honjo, and K. Ikuta. 1999. Induction of germline transcription in the TCRgamma locus by Stat5: implications for accessibility control by the IL-7 receptor. Immunity. 11:213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee, H.C., S.K. Ye, T. Honjo, and K. Ikuta. 2001. Induction of germline transcription in the human tcrgamma locus by stat5. J. Immunol. 167:320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trigueros, C., K. Hozumi, B. Silva-Santos, L. Bruno, A.C. Hayday, M.J. Owen, and D.J. Pennington. 2003. Pre-TCR signaling regulates IL-7 receptor alpha expression promoting thymocyte survival at the transition from the double-negative to double-positive stage. Eur. J. Immunol. 33:1968–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hinton, H.J., D.R. Alessi, and D.A. Cantrell. 2004. The serine kinase phophoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) regulates T cell development. Nat. Immunol. 5:539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blume-Jensen, P., and T. Hunter. 2001. Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature. 411:355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maraskovsky, E., L.A. O'Reilly, M. Teepe, L.M. Corcoran, J.J. Peschon, and A. Strasser. 1997. Bcl-2 can rescue T lymphocyte development in interleukin-7 receptor-deficient mice but not in mutant rag-1−/− mice. Cell. 89:1011–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akashi, K., M. Kondo, F. von, U. Jeffry, R. Murray, and I.L. Weissman. 1997. Bcl-2 rescues T lymphopoiesis in interleukin-7 receptor-deficient mice. Cell. 89:1033–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haks, M.C., P. Krimpenfort, J.H. van den Brakel, and A.M. Kruisbeek. 1999. Pre-TCR signaling and inactivation of p53 induces crucial cell survival pathways in pre-T cells. Immunity. 11:91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reif, K., C.D. Nobes, G. Thomas, A. Hall, and D.A. Cantrell. 1996. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signals activate a selective subset of Rac/Rho-dependent effector pathways. Curr. Biol. 6:1445–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galandrini, R., S.W. Henning, and D.A. Cantrell. 1997. Different functions of the GTPase Rho in prothymocytes and late pre-T cells. Immunity. 7:163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luo, H., W. Duguid, H. Chen, M. Maheu, and J. Wu. 1994. The effect of rapamycin on T cell development in mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 24:692–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Damoiseaux, J.G., L.J. Beijleveld, H.J. Schuurman, and P.J. van Breda Vriesman. 1996. Effect of in vivo rapamycin treatment on de novo T-cell development in relation to induction of autoimmune-like immunopathology in the rat. Transplantation. 62:994–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woltman, A.M., S.W. van der Kooij, P.J. Coffer, R. Offringa, M.R. Daha, and C. van Kooten. 2003. Rapamycin specifically interferes with GM-CSF signaling in human dendritic cells, leading to apoptosis via increased p27KIP1 expression. Blood. 101:1439–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Opferman, J.T., A. Letai, C. Beard, M.D. Sorcinelli, C.C. Ong, and S.J. Korsmeyer. 2003. Development and maintenance of B and T lymphocytes requires antiapoptotic MCL-1. Nature. 426:671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]