Abstract

The study of thrombopoiesis has evolved greatly since an era when platelets were termed “the dust of the blood,” only about 100 years ago. During this time megakaryocytes were identified as the origin of blood platelets; marrow-derived megakaryocytic progenitor cells were functionally defined and then purified; and the primary regulator of the process, thrombopoietin, was cloned and characterized and therapeutic thrombopoietic agents developed. During this journey we continue to learn that the physiologic mechanisms that drive proplatelet formation can be recapitulated in cell-free systems and their biochemistry evaluated; the molecular underpinnings of endomitosis are being increasingly understood; the intracellular signals sent by engagement of a large number of megakaryocyte surface receptors have been defined; and many of the transcription factors that drive megakaryocytic fate determination have been identified and experimentally manipulated. While some of these biologic processes mimic those seen in other cell types, megakaryocytes and platelets possess enough unique developmental features that we are virtually assured that continued study of thrombopoiesis will yield innumerable clinical and scientific insights for many decades to come.

Introduction

The adult human produces 1011 platelets daily at steady state, a level of production that can increase 20-fold or more in times of heightened demand. While our understanding of thrombopoiesis has grown considerably since the advent of clonal assays of megakaryocytic progenitor cells in the 1970s and the cloning and characterization of several hematopoietic growth factors that support the process in the 1980s and 1990s, as recently as 100 years ago platelets were referred to as the “dust of the blood” and we had virtually no notion of their origin. Platelets were described by Addison in 1841 as “extremely minute … granules” in blood1 and were termed “platelets” (blutplättchen) by Bizzozero, who also observed their adhesive qualities of “increased stickiness … when a vascular wall is damaged”.2,3 The same elements were identified by microscopic examination of blood smears by Osler and by Hayem in the late nineteenth century.4,5 Megakaryocytes have been recognized as rare marrow cells for nearly 2 centuries, but it was the elegant camera lucida studies of Howell in 1890 and his coining of the term “megakaryocyte” that led to their broader appreciation as distinct entities.6 In 1906, James Homer Wright suggested that blood “plates” are derived from the cytoplasm of megakaryocytes,7,8 and the basic elements of thrombopoiesis were established. Much has been learned since of the origins of thrombopoiesis.

The importance of megakaryopoiesis and thrombopoiesis for clinical medicine is immediately apparent; morbidity and mortality from bleeding due to moderate to severe thrombocytopenia is a major problem facing a wide range of patients. The origins of thrombocytopenia are beyond the scope of this review, but include both iatrogenic and naturally occurring conditions that are frequently encountered in clinical practice. The magnitude of the problem can be gauged by considering that in the United States approximately 1.5 million platelet transfusions (representing the equivalent of the platelets from 9 million units of blood) are administered yearly to patients to reduce their risk of severe bleeding.9 Unfortunately, platelet transfusion therapy is less than ideal. At least 30% are associated with one or more complications,10 usually by immune or cytokine-mediated febrile reactions, but occasionally by bacteremia, graft-versus-host disease, or acute pulmonary injury. Moreover, an inadequate platelet response due to HLA alloimmunization occurs in from 10% to 30% of individuals who require repeated platelet transfusions, depending on the nature of their disease.11 And platelet transfusions are expensive; the approximate cost of a standard platelet transfusion product (usually sufficient to raise the platelet count 30 to 50 × 109/L) is $600, rising substantially if either a single donor apheresis product is desired or removal of leukocytes or HLA matching is required. The distinguished physician and teacher William Osler stated, “We are still without a trustworthy medicine which can always be relied upon to control purpura.” In many ways, Osler's dilemma is as true today as when first penned in 1892.12 Clearly, an understanding of thrombopoiesis sufficient to allow therapeutic stimulation of marrow platelet production would prove superior to the transfusion of allogeneic platelets.

The cellular origins of megakaryopoiesis

The term “erythropoietin” was coined at the turn of the last century to describe the humoral substance responsible for red cell production. Working in rodent models of thrombocytopenia, Kelemen first coined the term “thrombopoietin” to describe the humoral substance responsible for the recovery of platelet levels after thrombocytopenia.13 In the 1970s and 1980s, several groups attempted to purify thrombopoietin from the plasma of thrombocytopenic animals and the conditioned media from various cultured cells.14,15 At the time, the only reliable assay on which to base a purification strategy was the 35S or 75Se methionine uptake assay into the peripheral blood platelets of mice or rats injected with the assay fraction. This in vivo assay proved very cumbersome—the assay was too insensitive, costly, and time consuming to be practical, and little progress was made. Clearly, a more experimentally tractable system was required to better understand the genesis of megakaryocytes and platelets. Culture conditions that support the proliferation of megakaryocytic progenitors were established in the late 1970s for both mouse and man.16,17 Using several semisolid media, 2 colony morphologies that contain exclusively megakaryocytes have been described. The colony-forming unit–megakaryocyte (CFU-MK) is a cell that develops into a simple colony containing from 3 to 50 mature megakaryocytes; larger, more complex colonies that include satellite collections of megakaryocytes and contain up to several hundred cells are derived from the burst-forming unit–megakaryocyte (BFU-MK). Because of the difference in their proliferative potential and by analogy to erythroid progenitors, BFU-MK and CFU-MK are thought to represent the primitive and mature progenitors restricted to the lineage, respectively. Initial studies of megakaryocyte colony-forming cells used plasma and nonnaturally occurring substances (such as phorbol esters), and more recent studies have used purified cytokines (see the following section on humoral regulation of megakaryopoiesis) to dissect the cellular basis for megakaryopoiesis. Like their erythroid counterparts, the cytokine requirements for CFU-MK are simple; thrombopoietin stimulates the growth of 75% of all CFU-MK, with interleukin (IL)-3 being required along with thrombopoietin for the remainder.18 IL-3 or steel factor (SF) is required along with thrombopoietin for more complex, larger MK colony formation from primitive progenitor cells.

Megakaryocytes also arise in clonal colonies containing cells of one or more additional hematopoietic lineages. The most primitive in vitro colony-forming cell is termed a colony-forming unit–granuloycte-erythrocyte-monocyte-megakaryocte (CFU-GEMM), mixed progenitor colony (CFU-Mix), or common myeloid progenitor (CMP19), and colonies derived from this cell often contain several megakaryocytes. A derivative of the CMP is the mixed MK/erythroid progenitor cell (MEP20). Before their purification, the existence of an MEP was postulated based on the many common features of cells of the erythroid and megakaryocytic lineage, including the expression of several common transcription factors (SCL, GATA1, GATA2, NF-E2), cell surface molecules (TER119), and cytokine receptors (for IL-3, SF, erythropoietin, and thrombopoietin), and the finding that most erythroid and MK leukemia cell lines display, or can be induced to display, features of the alternate lineage.21,22 Moreover, the cytokines most responsible for development of these 2 lineages, erythropoietin and thrombopoietin, are the 2 most closely related proteins in the hematopoietic cytokine family23 and display synergy in stimulating the growth of progenitors of both lineages.18

Like other primitive hematopoietic cells, bipotent MEPs resemble small lymphocytes but can be distinguished by a specific pattern of cell surface protein display, IL-7Rα−/Lin−/c-Kit+/Sca-1−/CD34−/FcRγlo. Cells committed to the megakaryocytic lineage then begin to express CD41 and CD61 (integrin αIIbβ3), CD42 (glycoprotein Ib) and glycoprotein V.24,25 Those that are committed to the erythroid lineage begin to express the transferrin receptor (CD71), and as they mature they lose CD41 expression but express the thrombospondin receptor (CD36), glycophorin, and ultimately globin. These and other cell surface markers provide experimental hematologists several strategies to purify committed MK progenitors.

The transcription factors expressed by megakaryocytic progenitors that allow for their commitment to the lineage are becoming increasingly well understood. GATA1 is an X-linked gene encoding a 50 kDa zinc finger DNA binding protein.26 Genetic elimination of the transcription factor established the critical role of this transcription factor in hematopoiesis; the GATA1−/− condition is embryonic lethal due to failure of erythropoiesis,27 and megakaryocyte-specific elimination of GATA1 leads to severe thrombocytopenia due to dysmegakaryopoiesis.28 GATA1 acts in concert with another protein that affects transcription without binding to DNA, friend of GATA (FOG29). The importance of this interaction to megakaryopoiesis is clear, because several different mutations of the site on GATA1 responsible for FOG binding lead to congenital thrombocytopenia.30

The ets family of transcription factors includes approximately 30 members that bind to a purine box sequence, and consists of proteins that interact in both positive and antagonistic ways. For example, PU.1, initially termed Spi-1 based on its association with spleen focus-forming virus products, blocks erythroid differentiation, although it supports megakaryocyte development.31 Moreover, the ets factor Fli-1 is essential for megakaryopoiesis32 and mutations in the genetic region of the transcription factor are associated with congenital thrombocytopenia in humans.33

The humoral regulation of megakaryopoiesis

As noted, the term thrombopoietin was coined to depict the humoral agent responsible for regulating thrombopoiesis and was posited to affect the maturation and release of platelets, but not to stimulate the proliferation of more primitive cells in this lineage. With the availability of in vitro megakaryocyte differentiation assays in the 1980s, additional purifications of thrombopoietin were attempted; nevertheless, although the availability of what was thought to be partially purified thrombopoietin helped to define its expected biologic properties,34,35 none of the initial purification efforts led to amino acid determination or cloning of the molecule.

Occasionally in science, a finding from one field, although important in itself, can have a profound and catalytic effect on a seemingly unrelated area of research. The discovery and characterization of the murine myeloproliferative leukemia virus (MPLV) had such an influence on the search for thrombopoietin. The virus causes an acute myeloproliferative syndrome in infected mice.36 In 1990, the responsible oncogene was cloned, and the proto-oncogene obtained 2 years later.37,38 Based on several characteristic features, it was immediately evident that the cellular gene was a member of the hematopoietic cytokine receptor family,39 which includes the receptors for erythropoietin, IL-3, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and multiple lymphokines. However, in 1992 its ligand was unknown; c-Mpl encoded an orphan receptor. Based on the origin of the c-Mpl cDNA, the bipotent erythroid/megakaryocytic cell line HEL,40 and antisense c-Mpl knock-out experiments demonstrating a significant reduction in megakaryocytes,41 many groups postulated that the c-Mpl ligand might be identical to thrombopoietin.

Using the c-Mpl proto-oncogene product coupled to affinity matrices, scientists at Genentech and at Amgen obtained microgram quantities of porcine and canine thrombopoietin, respectively, allowing their amino acid sequencing and cDNA cloning.42,43 An expression cloning strategy was used by our group to obtain cDNA for murine and then human thrombopoietin.23 While progress in understanding megakaryocyte biology and in purifying thrombopoietin was being made using the c-Mpl receptor, others had developed improved bioassays for the hormone and continued to make efforts using conventional purification strategies; 2 groups obtained sufficient plasma thrombopoietin from thrombocytopenic animals to obtain amino acid sequence and in one case clone cDNA for the hormone.44,45 Remarkably, the cDNA obtained from the above groups, cloned nearly simultaneously, all encoded the same polypeptide (except for species differences). Initial in vitro experiments using the corresponding recombinant proteins demonstrated the effect of each of these substances on megakaryocyte maturation, and injections into normal mice resulted in impressive increases in peripheral blood platelet counts and marrow megakaryopoiesis.46

With the availability of thrombopoietin and other cytokines, the physiology of megakaryopoiesis was established, and the molecular mechanisms that govern the process explored. The biologic activities of thrombopoietin have been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo in mice, rats, dogs, nonhuman primates and man. Incubation of marrow cells with thrombopoietin stimulates both megakaryocyte survival and proliferation, alone and in combination with other cytokines.46 In vivo, thrombopoietin stimulates platelet production in a log-linear manner to levels 10-fold higher than baseline46–48 without affecting the peripheral blood red or white cell counts. In addition, owing to its affect on hematopoietic stem cells,49,50 the number of erythroid and myeloid progenitors and mixed myeloid progenitors in marrow and spleen are also increased, an effect that is particularly impressive when the hormone is administered after myelosuppressive therapy.51–53 It is likely that this effect is due to the synergy between thrombopoietin and the other hematopoietic cytokines circulating at high levels in this condition.

Thanks to genetic studies, it is now clear that thrombopoietin is the primary regulator of thrombopoiesis. Elimination of either the c-Mpl or Tpo gene leads to profound thrombocytopenia in mice,49 due to a greatly reduced number of megakaryocyte progenitors and mature megakaryocytes as well as reduced polyploidy of the remaining megakaryocytes. A similar result occurs in humans; patients with congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia (CAMT) display numerous homozygous or mixed heterozygous nonsense or missense mutations that severely reduce activity or inactivate the thrombopoietin receptor, c-MPL.54

The regulation of thrombopoietin production has received much attention. Nearly 50 years ago it was shown that the experimental induction of immune-mediated thrombocytopenia results in a relatively rapid restoration of platelet levels followed by a brief period of rebound thrombocytosis.55 With the cloning and characterization of several cytokines that affect megakaryopoiesis in vitro, it was established that thrombopoietin, but not IL-6 or IL-11, is responsible for this response because in both experimental and most naturally occurring cases of thrombocytopenia, plasma concentrations of thrombopoietin vary inversely with platelet counts,56 rising to maximal levels within 24 hours of the onset of profound thrombocytopenia. Two nonmutually exclusive models have been advanced to explain these findings. In the first, thrombopoietin production is constitutive, but its consumption, and hence the level remaining in the blood to affect megakaryopoiesis, is determined by the mass of c-Mpl receptors present on platelets and megakaryocytes accessible to the plasma.57 In this way states of thrombocytosis result in increased thrombopoietin consumption (by the expanded platelet and/or megakaryocyte mass of c-Mpl receptors), reducing megakaryopoiesis. Conversely, thrombocytopenia reduces thrombopoietin consumption, resulting in elevated blood levels that stimulate platelet recovery. Moreover, thrombopoietin knockout mice display a gene dosage effect58; platelet levels in heterozygous mice are intermediate between those seen in wild type and null animals, suggesting that active regulation of the remaining thrombopoietin allele cannot compensate for the mild (60% of normal) thrombocytopenia induced by the loss of one allele.

A second model argues that thrombopoietin expression is a regulated event; very low platelet levels can upregulate thrombopoietin-specific mRNA expression, at least in the marrow.59–61 The signal(s) responsible for this form of thrombopoietin regulation are under investigation.62,63 Moreover, the thrombocytosis that is secondary to inflammation, which along with iron deficiency is responsible for most patients with thrombocytosis, is due to IL-6–mediated increases in hepatic thrombopoietin production.64,65 Obviously, receptor-mediated catabolism and inducible production mechanisms of thrombopoietin regulation, and hence megakaryopoiesis, are not mutually exclusive.

The cellular origins of thrombopoiesis

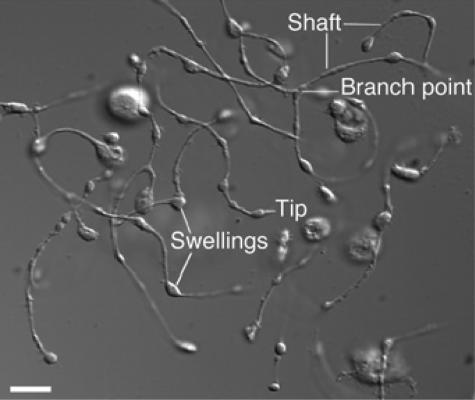

Platelets form by fragmentation of mature megakaryocyte membrane pseudopodial projections termed proplatelets (Figure 166), in a process that consumes nearly the entire cytoplasmic complement of membranes, organelles, granules, and soluble macromolecules. It has been estimated that each megakaryocyte gives rise to 1000 to 3000 platelets67 before the residual nuclear material is eliminated by macrophage-mediated phagocytosis.68 This process involves massive reorganization of megakaryocyte membranes and cytoskeletal components, including actin and tubulin, during a highly active, motile process in which the termini of the process branch and issue platelets.69 It is also likely that localized apoptosis plays a role in initiating the final stages of platelet formation,70,71 potentially by allowing the issuing of proplatelet processes from the constraints of the actin cytoskeleton. During the final stages of proplatelet maturation, cytoplasmic organelles and secretory granules traffic to the distal tips of proplatelet processes and are trapped there.72 Microtubules sliding over one another are the engine that drives the elongation of proplatelet processes and organelle transportation.73 In a humbling reminder that what comes before informs the present, proplatelets were first demonstrated to exist in vivo nearly 20 years ago, well before thrombopoiesis was understood in molecular terms.74 Despite our growing understanding ofthrombopoiesis, we still do not understand many basics; for example, little is known about what determines the size of mature platelets or how the mechanism of platelet formation is affected by the transcription factor GATA1, the glycoprotein Ib/IX complex, the Wiskott Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP), and platelet myosin, as defects in each of these genes leads to unusually large or small platelets.75 And despite the importance of thrombopoietin for the generation of fully mature megakaryocytes from which platelets arise, elimination of the cytokine during the final stages of platelet formation is not detrimental76; thus, whether humoral regulators of the final stages of platelet formation exist remains an incompletely answered question.

Figure 1.

Proplatelet processes. A differential interference contrast micrograph of several proplatelets is shown with the hallmark features, long thin shafts, branch points, and tip swellings. Reprinted with permission from Patel and colleagues.66

Translation to the thrombocytopenic patient

With this new understanding of the origins of thrombopoiesis should come a corresponding advance in our ability to manipulate the process for therapeutic benefit. Shortly after the cloning of thrombopoietin, several clinical trials were launched designed to ameliorate the thrombocytopenia that accompanies chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation. Two different forms of recombinant thrombopoietin were used in these clinical trials, one representing the full-length molecule produced in mammalian cell culture, the other a truncated form retaining the receptor binding domain of the hormone, produced in Escherichia coli and modified by the addition of polyethylene glycol. In general, both forms of the protein stimulated thrombopoiesis in healthy controls and hastened the recovery of platelet production in modest but not severe states of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia.77–80 However, use of the modified form of thrombopoietin in normal platelet donors leads, after repeated subcutaneous injections, to the development of antithrombopoietin antibodies and severe thrombocytopenia in many of these individuals.81 With this event the pharmaceutical industry abandoned the use of the full-length protein for therapeutic interventions, and instead concentrated on the development of thrombopoietin mimics, either peptides or small organic molecules that bind to and stimulate the thrombopoietin receptor. Over the past 2 years, several of these molecules have entered clinical testing, and results of the effects of 2 such molecules, AMG531 and Eltrombopag, have been reported.82,83 As with thrombopoietin, the thrombopoietin mimics reported thus far are potent stimulators of normal thrombopoiesis and accelerate the recovery of platelet levels in patients with immune-mediated and drug-induced thrombocytopenia. Additional studies will be required to carefully define the full range of usefulness of these pharmacologic agents, but the translation of our knowledge of megakaryopoiesis and thrombopoiesis to advance clinical medicine has begun to address Osler's dilemma of 1892.12

A look to the future

Our understanding of thrombopoiesis has progressed substantially over the past 100 years, when platelets were considered the “dust” of the blood. We can now purify to homogeneity every progenitor cell that gives rise to megakaryocytes, produce recombinant forms of the growth factors that stimulate production of megakaryocytes and platelets in vitro, and administer the primary regulator of this process, thrombopoietin, to man to stimulate thrombopoiesis under normal and pathologic conditions. And we understand the molecular basis of a growing number of disorders of platelet under- and overproduction. With advances in genomics, it is not fanciful to believe that we will soon be able to fully describe the genetic contributions to variations in normal platelet counts, which contribute to the incidence of cardiovascular disease,84 the origins of virtually all the congenital thrombocytopenias and myeloproliferative diseases, and how to therapeutically and specifically intervene in each.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD: R01 CA31615-25, R01 DK49855-14, and P01 HL 78784-03.

Biography

As a second-year resident at a major research-intense university, with many terrific opportunities in the subspecialties of internal medicine, I was certain of 2 things: I was a biochemist at heart, and I enjoyed the beauty of a bone marrow aspirate. I chose my subspecialty in a Darwinian fashion: I eliminated disciplines one by one, and hematology emerged. The ultimate reason is the persuasive arguments of Clem Finch, then Chief of Hematology at the University of Washington. After having visited the Chief of Nephrology, Belding Scribner (because acid-base physiology intrigued me), and the Chief of Pulmonary Medicine (for the same reason), and knowing of my great interest in biochemistry, Clem argued in 1981, “there is no other discipline in medicine where we know more about the biochemistry of disease than in hematology,” which was as true then as it is now. I was hooked. Following my clinical training in hematology and oncology, I entered the laboratory of John Adamson, who followed Clem as chief of the division. John suggested a project and a pathway: after acquiring the tools of hematopoietic colony growth, purify a colony-stimulating factor (CSF) by joining the laboratory of Dr Earl Davie, then Chair of the Department of Biochemistry. While it was yet unclear whether CSFs were “interesting in vitro artifacts” or bona fide physiologic regulators of hematopoiesis, I would gain a large number of tools for my biochemical and hematologic tool boxes in the process. In that dual mentoring setting where protected time for junior faculty was the rule, I gained a great deal, and emerged with purified GM-CSF, technical courage (the term used by Joe Goldstein to depict the capacity to move one's science however it progresses), and a cadre of terrific collaborators in academic medicine and the biotechnology industry. Platelets and thrombopoietin came next, but the die was cast early, and I now firmly believe that—to paraphrase Hillary Clinton—it takes a village to mentor a physician-scientist!

Authorship

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dr Kenneth Kaushansky, Chair, Department of Medicine, 402 Dickinson St, Suite 380, University of California, San Diego, CA 92103-8811; e-mail: kkaushansky@ucsd.edu.

References

- 1.Addison W. On the colourless corpuscles and on the molecules and cytoblasts in the blood. London Med Gaz. 1841;NS 30:144–152. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bizzozero G. Ueber einer neuen formbestandtheil des blutes und dessen rolle bei der thrombose und der blutgerinnung. Virchows Arch fur pathol Anat und Physiol. 1882;90:261–332. [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Gaetano G. A new blood corpuscle: an impossible interview with Giulio Bizzozero. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:973–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osler W, Schaefer EA. Uber einige im blute vorhandene bacterienbildende massen. Centralbl Med Wissensch. 1873;11:577–578. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayem G. Recherches sur l'evolution des hematies dans le sang de l'homme, et des vertebres. Arch Physiol (deuxieme serie) 1878;5:692–734. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howell WH. Observations upon the occurrence, structure, and function of the giant cells of the marrow. J Morphol. 1890;4:117–130. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright JH. The origin and nature of the blood plates. Boston Med Surg J. 1906;23:643–645. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright JH. The histogenesis of blood platelets. J Morphol. 1910;21:263–278. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace EL, Churchill WH, Surgenor DM, et al. Collection and transfusion of blood and blood components in the United States, 1992. Transfusion. 1995;35:802–812. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1995.351096026360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kruskall M. The perils of platelet transfusions. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1914–1915. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712253372609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slichter SJ, Davis K, Enright H, et al. Factors affecting posttransfusion platelet increments, platelet refractoriness, and platelet transfusion intervals in thrombocytopenic patients. Blood. 2005;105:4106–4114. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osler W. The Principles and Practice of Medicine. New York, NY: D. Appelton and Company; 1892. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelemen E, Cserhati I, Tanos B. Demonstration and some properties of human thrombopoietin in thrombocythemic sera. Acta Haematol (Basel) 1958;20:350–355. doi: 10.1159/000205503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonald TP, Andrews RB, Clift R, Cottrell M. Characterization of a thrombocytopoietic-stimulating factor from kidney cell culture medium. Exp Hematol. 1981;9:288–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill RJ, Level RM, Levin FC, Levin J. The effect of partially purified thrombopoietin on guinea pig megakaryocyte ploidy in vitro. Exp Hematol. 1989;17:903–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metcalf D, MacDonald HR, Odartchenko N, Sordat B. Growth of mouse megakaryocyte colonies in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:1744–1748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vainchenker W, Bouguet J, Guichard J, Breton-Gorius J. Megakaryocyte colony formation from human bone marrow precursors. Blood. 1979;54:940–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broudy VC, Lin NL, Kaushansky K. Thrombopoietin (c-mpl ligand) acts synergistically with erythropoietin, stem cell factor, and interleukin-11 to enhance murine megakaryocyte colony growth and increases megakaryocyte ploidy in vitro. Blood. 1995;85:1719–1726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akashi K, Traver D, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature. 2000;404:193–197. doi: 10.1038/35004599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakorn TN, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL. Characterization of mouse clonogenic megakaryocyte progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:205–210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262655099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonald TP, Sullivan PS. Megakaryocytic and erythrocytic cell lines share a common precursor cell. Exp Hematol. 1993;21:1316–1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakahata T, Okumura N. Cell surface antigen expression in human erythroid progenitors: erythroid and megakaryocytic markers. Leuk Lymphoma. 1994;13:401–409. doi: 10.3109/10428199409049629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lok S, Kaushansky K, Holly RD, et al. Cloning and expression of murine thrombopoietin cDNA and stimulation of platelet production in vivo. Nature. 1994;369:565–568. doi: 10.1038/369565a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hodohara K, Fujii N, Yamamoto N, Kaushansky K. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) acts together with thrombopoietin to enhance the development of megakaryocytic progenitor cells (CFU-MK). Blood. 2000;95:769–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roth GJ, Yagi M, Bastian LS. The platelet glycoprotein Ib-V-IX system: regulation of gene expression. Stem Cells. 1996;14(Suppl 1):188–193. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530140724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin DI, Zon LI, Mutter G, Orkin SH. Expression of an erythroid transcription factor in megakaryocytic and mast cell lineages. Nature. 1990;344:444–447. doi: 10.1038/344444a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pevny L, Simon MC, Robertson E, et al. Erythroid differentiation in chimaeric mice blocked by a targeted mutation in the gene for transcription factor GATA-1. Nature. 1991;349:257–260. doi: 10.1038/349257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shivdasani RA, Fujiwara Y, McDevitt MA, Orkin SH. A lineage-selective knockout establishes the critical role of transcription factor GATA-1 in megakaryocyte growth and platelet development. EMBO J. 1997;16:3965–3973. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsang AP, Visvader JE, Turner CA, et al. FOG, a multitype zinc finger protein, acts as a cofactor for transcription factor GATA-1 in erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation. Cell. 1997;90:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nichols KE, Crispino JD, Poncz M, et al. Familial dyserythropoietic anaemia and thrombocytopenia due to an inherited mutation in GATA1. Nat Genet. 2000;24:266–270. doi: 10.1038/73480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doubeikovski A, Uzan G, Doubeikovski Z, et al. Thrombopoietin-induced expression of the glycoprotein IIb gene involves the transcription factor PU. 1/Spi-1 in UT7-Mpl cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24300–24307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Athanasiou M, Clausen PA, Mavrothalassitis GJ, Zhang XK, Watson DK, Blair DG. Increased expression of the ETS-related transcription factor FLI-1/ERGB correlates with and can induce the megakaryocytic phenotype. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:1525–1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hart A, Melet F, Grossfeld P, et al. Fli-1 is required for murine vascular and megakaryocytic development and is hemizygously deleted in patients with thrombocytopenia. Immunity. 2000;13:167–177. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carter CD, Schultz TW, McDonald TP. Thrombopoietin from human embryonic kidney cells stimulates an increase in megakaryocyte size of sublethally irradiated mice. Radiat Res. 1993;135:32–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erickson-Miller CL, Ji H, Parchment RE, Murphy MJ., Jr Megakaryocyte colony-stimulating factor (Meg-CSF) is a unique cytokine specific for the megakaryocyte lineage. Br J Haematol. 1993;84:197–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1993.tb03052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wendling F, Varlet P, Charon M, Tambourin P. MPLV: a retrovirus complex inducing an acute myeloproliferative leukemic disorder in adult mice. Virology. 1986;149:242–246. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Souyri M, Vigon I, Penciolelli JF, Heard JM, Tambourin P, Wendling F. A putative truncated cytokine receptor gene transduced by the myeloproliferative leukemia virus immortalizes hematopoietic progenitors. Cell. 1990;63:1137–1147. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90410-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vigon I, Mornon JP, Cocault L, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of MPL, the human homolog of the v-mpl oncogene: identification of a member of the hematopoietic growth factor receptor superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5640–5644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cosman D. The hematopoietin receptor superfamily. Cytokine. 1993;5:95–106. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(93)90047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Long MW, Heffner CH, Williams JL, Peters C, Prochownik EV. Regulation of megakaryocyte phenotype in human erythroleukemia cells. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1072–1084. doi: 10.1172/JCI114538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Methia N, Louache F, Vainchenker W, Wendling F. Oligodeoxynucleotides antisense to the proto-oncogene c-mpl specifically inhibit in vitro megakaryocytopoiesis. Blood. 1993;82:1395–1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Sauvage FJ, Hass PE, Spencer SD, et al. LA, Goeddel DV, Eaton DL. Stimulation of megakaryocytopoiesis and thrombopoiesis by the c-Mpl ligand. Nature. 1994;369:533–538. doi: 10.1038/369533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bartley TD, Bogenberger J, Hunt P, et al. Identification and cloning of a megakaryocyte growth and development factor that is a ligand for the cytokine receptor Mpl. Cell. 1994;77:1117–1124. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90450-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sohma Y, Akahori H, Seki N, et al. Molecular cloning and chromosomal localization of the human thrombopoietin gene. FEBS Lett. 1994;353:57–61. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuter DJ, Beeler DL, Rosenberg RD. The purification of megapoietin: a physiological regulator of megakaryocyte growth and platelet production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11104–11108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaushansky K, Lok S, Holly RD, et al. Promotion of megakaryocyte progenitor expansion and differentiation by the c-Mpl ligand thrombopoietin. Nature. 1994;369:568–571. doi: 10.1038/369568a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harker LA, Marzec UM, Hunt P, et al. Dose-response effects of pegylated human megakaryocyte growth and development factor on platelet production and function in nonhuman primates. Blood. 1996;88:511–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Basser RL, Rasko JE, Clarke K, et al. Thrombopoietic effects of pegylated recombinant human megakaryocyte growth and development factor (PEG-rHuMGDF) in patients with advanced cancer. Lancet. 1996;348:1279–1281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)04471-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Solar GP, Kerr WG, Zeigler FC, et al. Role of c-mpl in early hematopoiesis. Blood. 1998;92:4–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fox NE, Priestley GV, Papayannopoulou Th, Kaushansky K. Thrombopoietin (TPO) expands hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:389–394. doi: 10.1172/JCI15430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaushansky K, Broudy VC, Grossmann A, et al. Thrombopoietin expands erythroid progenitors, increases red cell production, and enhances erythroid recovery after myelosuppressive therapy. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1683–1687. doi: 10.1172/JCI118210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akahori H, Shibuya K, Obuchi M, et al. Effect of recombinant human thrombopoietin in nonhuman primates with chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol. 1996;94:722–728. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Neelis KJ, Hartong SC, Egeland T, Thomas GR, Eaton DL, Wagemaker G. The efficacy of single-dose administration of thrombopoietin with coadministration of either granulocyte/macrophage or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in myelosuppressed rhesus monkeys. Blood. 1997;90:2565–2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ballmaier M, Germeshausen M, Schulze H, et al. c-mpl mutations are the cause of congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2001;97:139–146. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Odell TT, Jr, McDonald TP, Detwiler TC. Stimulation of platelet production by serum of platelet-depleted rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1961;108:428–431. doi: 10.3181/00379727-108-26958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nichol JL, Hokom MM, Hornkohl A, et al. Megakaryocyte growth and development factor. Analyses of in vitro effects on human megakaryopoiesis and endogenous serum levels during chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2973–2978. doi: 10.1172/JCI118005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuter DJ, Rosenberg RD. The reciprocal relationship of thrombopoietin (c-Mpl ligand) to changes in the platelet mass during busulfan-induced thrombocytopenia in the rabbit. Blood. 1995;85:2720–2730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Sauvage FJ, Carver-Moore K, Luoh SM, et al. Physiological regulation of early and late stages of megakaryocytopoiesis by thrombopoietin. J Exp Med. 1996;183:651–656. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McCarty JM, Sprugel KH, Fox NE, Sabath DE, Kaushansky K. Murine thrombopoietin mRNA levels are modulated by platelet count. Blood. 1995;86:3668–3675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sungaran R, Markovic B, Chong BH. Localization and regulation of thrombopoietin mRNa expression in human kidney, liver, bone marrow, and spleen using in situ hybridization. Blood. 1997;89:101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guerriero A, Worford L, Holland HK, Guo GR, Sheehan K, Waller EK. Thrombopoietin is synthesized by bone marrow stromal cells. Blood. 1997;90:3444–3455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Solanilla A, Dechanet J, El Andaloussi A, et al. CD40-ligand stimulates myelopoiesis by regulating flt3-ligand and thrombopoietin production in bone marrow stromal cells. Blood. 2000;95:3758–3764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sungaran R, Chisholm OT, Markovic B, Khachigian LM, Tanaka Y, Chong BH. The role of platelet alpha-granular proteins in the regulation of thrombopoietin messenger RNA expression in human bone marrow stromal cells. Blood. 2000;95:3094–3101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wolber EM, Fandrey J, Frackowski U, Jelkmann W. Hepatic thrombopoietin mRNA is increased in acute inflammation. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:1421–1424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaser A, Brandacher G, Steurer W, et al. Interleukin-6 stimulates thrombopoiesis through thrombopoietin: role in inflammatory thrombocytosis. Blood. 2001;98:2720–2725. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.9.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Patel SR, Hartwig JH, Italiano JE., Jr The biogenesis of platelets from megakaryocyte proplatelets. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3348–3354. doi: 10.1172/JCI26891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stenberg PE, Levin J. Mechanisms of platelet production. Blood Cells. 1989;15:23–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Radley JM, Haller CJ. Fate of senescent megakaryocytes in the bone marrow. Br J Haematol. 1983;53:277–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1983.tb02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Italiano JE, Jr, Lecine P, Shivdasani RA, Hartwig JH. Blood platelets are assembled principally at the ends of proplatelet processes produced by differentiated megakaryocytes. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1299–1312. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.6.1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li J, Kuter DJ. The end is just the beginning: megakaryocyte apoptosis and platelet release. Int J Hematol. 2001;74:365–374. doi: 10.1007/BF02982078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.De Botton S, Sabri S, Daugas E, et al. Platelet formation is the consequence of caspase activation within megakaryocytes. Blood. 2002;100:1310–1317. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Richardson JL, Shivdasani RA, Boers C, Hartwig JH, Italiano JE., Jr Mechanisms of organelle transport and capture along proplatelets during platelet production. Blood. 2005;106:4066–4075. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patel SR, Richardson JL, Schulze H, et al. Differential roles of microtubule assembly and sliding in proplatelet formation by megakaryocytes. Blood. 2005;106:4076–4085. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tavassoli M, Aoki M. Localization of megakaryocytes in the bone marrow. Blood Cells. 1989;15:3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Geddis AE, Kaushansky K. Inherited thrombocytopenias: toward a molecular understanding of disorders of platelet production. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2004;16:15–22. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200402000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Choi ES, Nichol JL, Hokom MM, Hornkohl AC, Hunt P. Platelets generated in vitro from proplatelet-displaying human megakaryocytes are functional. Blood. 1995;85:402–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Basser RL, Rasko JEJ, Clarke K, et al. Thrombopoietic effects of pegylated recombinant human megakaryocyte growth and development factor (PEG-rHuMGDF) in patients with advanced cancer. Lancet. 1996;348:1279–1281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)04471-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vadhan-Raj S, Verschraegen CF, Bueso-Ramos C, et al. Recombinant human thrombopoietin attenuates carboplatin-induced severe thrombocytopenia and the need for platelet transfusions in patients with gynecologic cancer. Ann Int Med. 2000;132:364–368. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-5-200003070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Archimbaud E, Ottmann O, Liu Yin JA, et al. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with pegylated recombinant human megakaryocyte growth and development factor (PEG-rHuMGDF) as an adjunct to chemotherapy for adults with de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 1999;94:3694–3701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bolwell B, Vredenburgh J, Overmoyer B, et al. Phase 1 study of pegylated recombinant human megakaryocyte growth and development factor (PEG-rHuMGDF) in breast cancer patients after autologous peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation (PBPC). Bone Marrow Transpl. 2000;26:141–145. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li J, Yang C, Xia Y, et al. Thrombocytopenia caused by the development of antibodies to thrombopoietin. Blood. 2001;98:3241–3248. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bussel JB, Kuter DJ, George JN, et al. AMG 531, a thrombopoiesis-stimulating protein, for chronic ITP. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1672–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jenkins JM, Williams D, Deng Y, et al. Phase I clinical study of eltrombopag, an oral, non-peptide thrombopoietin receptor agonist. Blood. 2007;109:4739–4741. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-057968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thaulow E, Erikssen J, Sandvik L, Stormorken H, Cohn PF. Blood platelet count and function are related to total and cardiovascular death in apparently healthy men. Circulation. 1991;84:613–617. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.2.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]