Abstract

A total of 87 Acinetobacter baumannii nonrepetitive consecutive clinical isolates were tested for the presence of metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs). Results of phenotypic assays (MBL Etest, imipenem/imipenem-EDTA combined-disk test, and imipenem/EDTA double-disk synergy test) were negative in all cases, but molecular testing revealed the presence of two blaVIM-1-carrying isolates. One isolate had blaVIM-1 preceded by a weak P1 promoter, and both had inactivated P2 promoters and reduced blaVIM-1 expression, partially justifying the results revealing hidden MBL phenotypes.

Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains are increasingly recovered from hospitalized patients worldwide and in some cases are associated with high morbidity and mortality rates (5). Mechanisms of resistance in such strains have been associated with decreased permeability, efflux pump overexpression, and, more lately, production of carbapenemases (10). Metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs), mainly of types IMP and VIM, are increasingly associated with the reduced susceptibility to carbapenems seen in several gram-negative species (15). However, despite the worldwide occurrence of epidemic carbapenem-resistant strains, MBL-producing A. baumannii isolates have been found to be disseminated only in specific geographic areas (8, 10). In Greek hospitals high rates of carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii clinical isolates are also detected, but MBL producers have been recognized in only a few instances (12). Therefore, the detection of these enzymes is of major importance in the control of A. baumannii hospital infections.

Several schemes have been proposed for the phenotypic detection of MBL-producing gram-negative species, including A. baumannii. These tests take advantage of the zinc dependence of MBLs by using chelating agents, such as EDTA, to inhibit enzyme activity (8). However, the phenotypic appearance of MBL-carrying organisms seems to depend on the nature of the bacterial host, since carbapenem-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae organisms may carry MBL genes not readily detectable by conventional assays (15). A recent study introduced a more sensitive procedure for MBL detection in a broad range of host organisms, including carbapenem-susceptible isolates (3). This prompted us to test a series of Greek A. baumannii clinical isolates which appeared to be MBL negative in routine clinical testing.

The study included 87 A. baumannii clinical isolates consecutively recovered from separate patients during October 2006 to March 2007 at the University Hospital of Larissa, Larissa, Greece. Species identification was performed by use of an API 20NE system (bioMerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) and PCR amplification of the intrinsic blaOXA-51 allele (13). Imipenem and meropenem MICs were tested by the agar dilution method according to CLSI recommendations and interpretive criteria (1), while status of susceptibility to other β-lactams, as well as to aminoglycosides, quinolones, and colistin, was investigated by disk diffusion testing. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 was used as a control in susceptibility assays. MBL phenotypic detection was performed with (i) an MBL Etest (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden), which is routinely applied in our laboratory, (ii) a double-disk synergy test (DDST), which included placing 20 mm apart one imipenem (10 μg) disk and another with 10 μl 0.1 M EDTA (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO), and (iii) a combined-disk test using two imipenem (10 μg) disks, one containing 10 μl of 0.1 M EDTA (Sigma), following previously described methods (3). All MBL phenotypic assays were performed using Mueller-Hinton agar, which has been proven to be the most sensitive medium for MBL detection (14); those assays were performed at least in triplicate in order to assess consistency. The criteria used for interpretation of the phenotypic assays were those proposed by Franklin et al. (3). A blaVIM-1-carrying A. baumannii isolate (strain AB5) (12) was used as a positive control. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of ApaI-digested genomic DNA was performed as previously described (11) to detect possible clonal dissemination among members of our bacterial collection.

All isolates were screened by PCR for known carbapenemase-encoding genes (blaIMP, blaVIM, blaSIM, blaOXA-23-like, blaOXA-24-like, blaOXA-58) using previously published primers and amplification conditions (6, 11). Primers amplifying the whole blaVIM region were used for sequencing purposes (16). Typing of the putative related integrons was performed with PCR mapping using primers specific for intI and blaVIM-like genes (4). PCR products were sequenced in both strands using an ABI Prism system. The blaVIM-positive isolates were also tested for the presence of insertion sequence (IS) elements ISAba1 and ISAba3, which contribute to OXA-51 and OXA-58 upregulation, respectively, by PCR mapping with combinations of primers specific for OXA genes and IS elements (11). To test the contribution of OXA-58 to the carbapenem resistance the phenotypic tests for MBL detection were performed on the blaVIM-positive isolates with and without the presence of 200 mM NaCl (11).

Total cellular RNA was extracted with TRI reagent (Ambion). RNA abundance and purity was determined spectrophotometrically at 260 nm and 280 nm. Contaminating DNA was removed with DNase I treatment; residual DNase was removed by phenol-chloroform precipitation. Reverse transcription of 1 μg of total RNA was performed with a ThermoScript reverse transcriptase PCR system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR (Q-RealTime-PCR) was performed using a MX3005P apparatus (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and brilliant SYBR green (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) (to detect expression of blaVIM-like gene) and the above-mentioned primers (4). All reactions were performed in triplicate, and expression levels were compared to those seen with strain AB5, carrying blaVIM-1 downstream of a strong Pant promoter, which was set as a calibrator. The single-copy housekeeping recA gene was used for normalization (11), and control reactions using untranscribed RNA were also included. Cycling parameters for all tested genes were as follows: one cycle of 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 90 s. Analysis of the outer-membrane proteins (OMPs) was performed as previously described (7).

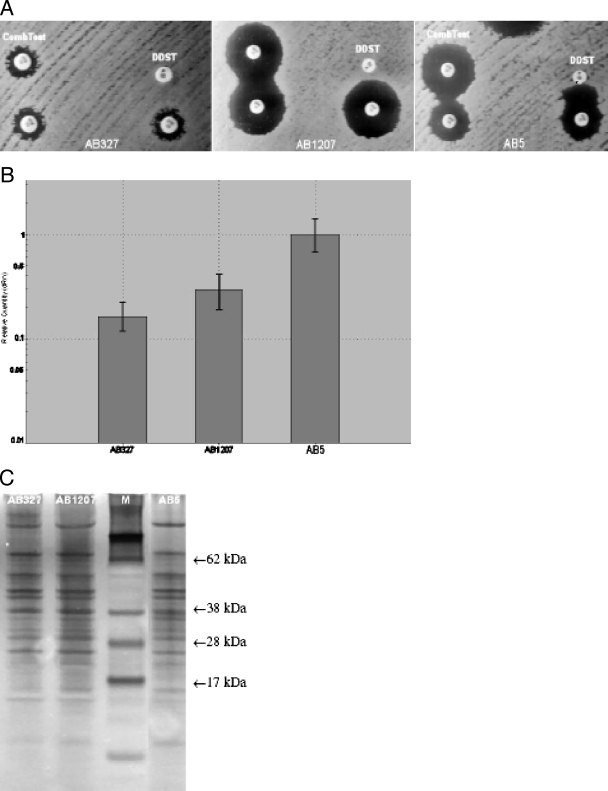

Of the tested isolates, 61 (70.1%) were resistant to both carbapenems, exhibiting drug MICs of at least 16 μg/ml, as well as to all other antimicrobials except colistin. Of the remaining isolates, 15 were susceptible to both carbapenems and 11 were imipenem intermediate (MIC, 8 μg/ml) but meropenem susceptible (MIC, ≤4 μg/ml). Carbapenem MICs ranged from 2 to 512 μg/ml for imipenem and from 1 to 64 μg/ml for meropenem, with the MIC50 and MIC90 values being 32 and 128 μg/ml and 8 and 32 μg/ml, respectively. The three phenotypic assays for MBL production were negative for all 87 A. baumannii isolates but typically positive for the control strain (Fig. 1A). That result represents a ≥8-fold reduction in IMP MIC for the MBL Etest, a more than 4-mm increase in the size of the imipenem-EDTA inhibition halo compared to that seen with imipenem alone in the combined test and enhancement of the zone of inhibition in the area between the two disks in the DDST (3) (Table 1). No differences were detected when these tests were performed in the presence of 200 mM NaCl, indicating that the contribution of OXA-58 to the carbapenem resistance was not significant. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis revealed 11 distinct clonal types among the 87 A. baumannii isolates on the basis of more than three band differences; the 61 carbapenem-resistant isolates also belonged to several unrelated clones, with three of those found to be dominant.

FIG. 1.

(A) Phenotypic assays for the two blaVIM-1-carrying A. baumannii isolates of the study in comparison with control strain AB5B results. (B) Q-RealTime-PCR results for the blaVIM gene. (C) OMP profiles (lane M, molecular mass marker).

TABLE 1.

Data from the two blaVIM-1-producing A. baumannii isolates relative to AB5 control strain resultsa

| Isolate | Phenotypic assays

|

MIC (μg/ml)

|

PCR, sequencing, and gene expression results

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition halo size (mm) in combined test

|

Result

|

IMP | MEM | blaOXA-58 | ISAba3 adjacent to blaOXA-58 | blaVIM-1 | Promoter status

|

Decrease (fold) in blaVIM-1 expression relative to AB5 expression | ||||

| IMP | IMP + EDTA | DDST | MBL Etest | |||||||||

| P1 | P2 | |||||||||||

| AB5 | 17 | 25 | + | + | 8 | 4 | + | + | + | Strong | Inactivated | |

| AB327 | 11 | 11 | − | − | 64 | 16 | + | + | + | Weak | Inactivated | 2.62 ± 0.05 |

| AB1207 | 26 | 26 | − | − | 2 | 1 | + | − | + | Strong | Inactivated | 1.76 ± 0.09 |

IMP, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; +, positive result; −, negative result.

PCR results were positive for the intrinsic blaOXA-51-like gene in all 87 isolates and for the blaOXA-58 gene in 80 (91.9%) of them. None of the remaining carbapenemase genes was amplified except for the blaVIM gene, which was detected in two genotypically unrelated isolates (AB327 and AB1207) that were also positive for blaOXA-58 gene (Table 1). Of these isolates, one (AB327) was resistant to carbapenems and all other β-lactams, while the second (AB1207) was susceptible to carbapenems and also to ampicillin-sulbactam. Both isolates had an ISAba1 element irrelevant to blaOXA-51, while AB327 had ISAba3 adjacent to blaOXA-58.The isolates were also genotypically unrelated to the control strain. Nucleotide sequencing in both cases revealed the blaVIM-1 allele. One of these isolates (AB327) was resistant to both carbapenems (imipenem MIC, 64 μg/ml; meropenem MIC, 16 μg/ml), while the other (AB1207) was susceptible (imipenem MIC, 2 μg/ml; meropenem MIC, 1 μg/ml). PCR mapping of the upstream region of blaVIM-1 gene revealed that both alleles were part of a class 1 integron structure carrying the intI1 allele. In strain AB327, blaVIM-1 was preceded by a weak P1 promoter (−35 box, TGGACA; −10 box, TAAGCT) and an inactivated P2 promoter (no GGG insertion). The Pant promoter upstream of blaVIM-1 in strain AB1207 was identical to the corresponding promoter of the control AB5 strain (strong P1 and inactivated P2). Q-RealTime-PCR showed that compared to the control strain results, isolates AB327 and AB1207 exhibited 2.62 (± 0.05)-fold and 1.76 (± 0.09)-fold reductions in blaVIM-1 expression, respectively (Fig. 1B). OMP profiles did not show any particular differences in results between the two A. baumannii isolates of the study and strain AB5 (Fig. 1C).

In the current study three phenotypic assays, including the recently modified combined test (3), were applied in order to recover possibly hidden MBL-encoding genes in a collection of A. baumannii clinical isolates. Although these assays were negative for all tested isolates, molecular testing revealed two isolates carrying blaVIM-l gene within class 1 integron structures. Both blaVIM-1-positive isolates were found to significantly (P < 0.0001) underexpress the MBL-encoding gene relative to the results seen with a control VIM-1 producer. The presence of a weak P1 promoter like the one upstream of the blaVIM-1 gene in AB327 has been previously shown to result in a 20-fold decrease in the level of resistance conferred by the downstream gene cassettes relative to the levels seen with promoters like that of the control strain (2). That may reflect a low contribution of blaVIM-1 to carbapenem resistance in isolate AB327 which might alternatively be attributed to other combined mechanisms, partially explaining the unconventional detection of the respective MBL determinant.

Isolate AB1207 had lower carbapenem MICs than AB327, partially justifying the negative result from the MBL Etest, which tests imipenem MICs of >4 mg/liter, and indicating that VIM-1 production per se may not suffice to elevate carbapenem MICs for A. baumannii. The nondetection of the MBL phenotype by the combined test and the DDST, which were found to detect efficiently carbapenem-susceptible isolates (3), may indicate that this level of VIM-1 expression probably did not significantly elevate carbapenem MICs for isolate AB1207. It is of interest that this isolate carried the same Pant sequence as did the control strain but showed a significant reduction of blaVIM-1 expression. However, it has yet to be defined whether gene expression in integron structures or mRNA stability is regulated by other genetic elements in addition to Pant. It should be noted that attempts to select mutants of AB1207 with possible VIM-1 upregulation and higher imipenem MICs, by subculturing the isolate in twofold increments of imipenem concentrations, were unsuccessful and that the isolate grew to a level of no more than 1 μg/ml (data not shown).

So far, identifying MBL-carrying isolates has been challenging due to the emergence of carbapenem-susceptible MBL-carrying organisms which may be missed in daily laboratory practice, compromising the sensitivity of detection methods (15). It has been suggested that screening only carbapenem-resistant organisms, as is most often performed, might produce suboptimal results (3). In the present study a blaVIM-1-producing carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii clinical isolate showed a negative MBL phenotype but was PCR positive for the respective gene. That observation raises the issue of whether phenotypic screening of putative MBL carriers is sufficient in terms of sensitivity. This issue is more debatable for species like A. baumannii in which several factors seem to provoke high levels of carbapenem resistance and MBL inhibition might not reverse the susceptibility status. It is plausible to suggest that in regions where VIM producers are common, all carbapenem-resistant isolates should be tested by PCR regardless of whether the conventional MBL testing is performed. This would be a more expensive and laborious approach; however, the disadvantages might be outweighed by the prevention of horizontal interspecies spread of hidden MBLs, as was emphasized previously (9).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 November 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2005. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 15th informational supplement, M100-S15. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 2.Collis, C. M., and R. M. Hall. 1995. Expression of antibiotic resistance genes in the integrated cassettes of integrons. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39155-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franklin, C., L. Liolios, and A. Y. Peleg. 2006. Phenotypic detection of carbapenem-susceptible metallo-β-lactamase-producing gram-negative bacilli in the clinical laboratory. J. Clin. Microbiol. 443139-3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ikonomidis, A., D. Tokatlidou, I. Kristo, D. Sofianou, A. Tsakris, P. Mantzana, S. Pournaras, and A. N. Maniatis. 2005. Outbreaks in distinct regions due to a single Klebsiella pneumoniae clone carrying a blaVIM-1 metallo-β-lactamase gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 435344-5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuo, L. C., C. C. Lai, C. H. Liao, C. K. Hsu, Y. L. Chang, C. Y. Chang, and P. R. Hsueh. 2007. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii bacteraemia: clinical features, antimicrobial therapy and outcome. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13196-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee, K., J. H. Yum, D. Yong, H. M. Lee, H. D. Kim, J. D. Docquier, G. M. Rossolini, and Y. Chong. 2005. Novel acquired metallo-β-lactamase gene, blaSIM-1, in a class 1 integron from Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates from Korea. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 494485-4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maniati, M., A. Ikonomidis, P. Mantzana, A. Daponte, A. N. Maniatis, and S. Pournaras. 2007. A highly carbapenem resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate with a novel blaVIM-4/blaP1b integron over-expresses two efflux pumps and lacks OprD. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60132-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oh, E. J., S. Lee, Y. J. Park, J. J. Park, K. Park, S. I. Kim, M. W. Kang, and B. K. Kim. 2003. Prevalence of metallo-β-lactamase among Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii in a Korean university hospital and comparison of screening methods for detecting metallo-β-lactamase. J. Microbiol. Methods 54411-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peleg, A. Y., C. Franklin, J. M. Bell, and D. W. Spelman. 2005. Dissemination of the metallo-β-lactamase gene blaIMP-4 among gram-negative pathogens in a clinical setting in Australia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 411549-1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poirel, L., and P. Nordmann. 2006. Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: mechanisms and epidemiology. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12826-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pournaras, S., A. Markogiannakis, A. Ikonomidis, L. Kondyli, K. Bethimouti, A. N. Maniatis, N. J. Legakis, and A. Tsakris. 2006. Outbreak of multiple clones of imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates expressing OXA-58 carbapenemase in an intensive care unit. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57557-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsakris, A., A. Ikonomidis, S. Pournaras, L. S. Tzouvelekis, D. Sofianou, N. J. Legakis, and A. N. Maniatis. 2006. VIM-1 metallo-β-lactamase in Acinetobacter baumannii. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12981-983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turton, J. F., N. Woodford, J. Glover, S. Yarde, M. E. Kaufmann, and T. L. Pitt. 2006. Identification of Acinetobacter baumannii by detection of the blaOXA-51-like carbapenemase gene intrinsic to this species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 442974-2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh, T. R., A. Bolmström, A. Qwärnström, and A. Gales. 2002. Evaluation of a new Etest for detecting metallo-β-lactamases in routine clinical testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 402755-2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh, T. R., M. A. Toleman, L. Poirel, and P. Nordmann. 2005. Metallo-β-lactamases: the quiet before the storm? Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18306-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan, J. J., P. R. Hsueh, W. C. Ko, K. T. Luh, S. H. Tsai, H. M. Wu, and J.-J. Wu. 2001. Metallo-β-lactamases in clinical Pseudomonas isolates in Taiwan and identification of VIM-3, a novel variant of the VIM-2 enzyme. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 452224-2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]