Abstract

Infection with DNA viruses commonly results in the association of viral genomes with a cellular subnuclear structure known as nuclear domain 10 (ND10). Recent studies demonstrated that individual ND10 components, like hDaxx or promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML), mediate an intrinsic immune response against human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection, strengthening the assumption that ND10 components are part of a cellular antiviral defense mechanism. In order to further define the role of hDaxx and PML for HCMV replication, we generated either primary human fibroblasts with a stable, individual knockdown of PML or hDaxx (PML-kd and hDaxx-kd, respectively) or cells exhibiting a double knockdown. Comparative analysis of HCMV replication in PML-kd or hDaxx-kd cells revealed that immediate-early (IE) gene expression increased to a similar extent, regardless of which ND10 constituent was depleted. Since a loss of PML, the defining component of ND10, results in a dispersal of the entire nuclear substructure, the increased replication efficacy of HCMV in PML-kd cells could be a consequence of the dissociation of the repressor protein hDaxx from its optimal subnuclear localization. However, experiments using three different recombinant HCMVs revealed a differential growth complementation in PML-kd versus hDaxx-kd cells, strongly arguing for an independent involvement in suppressing HCMV replication. Furthermore, infection experiments using double-knockdown cells devoid of both PML and hDaxx illustrated an additional enhancement in the replication efficacy of HCMV compared to the single-knockdown cells. Taken together, our data indicate that both proteins, PML and hDaxx, mediate an intrinsic immune response against HCMV infection by contributing independently to the silencing of HCMV IE gene expression.

Complex organisms have evolved several lines of defense in response to infection by pathogens. Besides the relatively well-characterized conventional innate and adaptive immune response, intrinsic immunity, a branch of defense neglected for a long time, has just recently gained substantial interest. Intrinsic immune mechanisms are of considerable importance as they form an antiviral frontline defense mediated by constitutively expressed proteins, termed restriction factors, that are already present and active before a virus enters the cell (6). While cellular intrinsic immune mechanisms in response to retroviral infections are already relatively well studied, the analysis of their role during herpesvirus infection can still be described as being in its infancy.

In the case of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a member of the β-subgroup of herpesviruses, only lately two cellular proteins, promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) and hDaxx, have been identified as restriction factors that are involved in mediating intrinsic immunity against HCMV infection (8, 45, 46, 48, 50). Interestingly, both proteins, PML and hDaxx, are components of a cellular subnuclear structure known as nuclear domain 10 (ND10) or PML nuclear bodies. ND10 structures represent multiprotein complexes of the cellular proteins PML, hDaxx, and Sp100 that assemble in distinct foci within the interchromosomal space of the nucleus (42). Previous studies identified the PML protein as the defining factor of ND10 structures since it functions as a kind of scaffold protein that is responsible for the assembly and maintenance of this domain and recruits other ND10-associated proteins like hDaxx to this subnuclear structure (25, 53). For a long time, this subcellular compartment, which colocalizes with sites where the input viral genome of various DNA viruses (herpesviruses, adenoviruses, and papovaviruses) accumulates, was hypothesized to be essential for HCMV replication since only viral DNA deposited at ND10 had been demonstrated to initiate transcription (24, 37). In contrast, several lines of evidence likewise implicated these nuclear substructures to be involved in host antiviral defenses. Arguments in favor of such an interpretation were as follows: (i) interferon treatment of cells induces the expression of ND10-associated proteins like PML or Sp100 (9, 18), resulting in an increase in both the size and number of ND10 structures (17); (ii) HCMV infection progresses poorly in cells expressing high levels of exogenous PML (4); (iii) specific regulatory proteins of several DNA viruses, including HCMV, accumulate at ND10 structures during infection to cause their disruption by a variety of different mechanisms. Such a structural modification of ND10 has been shown to correlate with increased efficiency of viral replication (13).

Direct evidence for an antiviral role of this subnuclear structure was finally obtained from infection studies using cells devoid of genuine ND10: extensive, small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated depletion of PML in primary human fibroblasts significantly increased the plaque-forming efficiency of HCMV as a result of an augmented immediate-early (IE) gene expression (48). Similarly, plaque formation and IE gene expression of an ICP0-deficient herpes simplex virus type 1 was also shown to be enhanced in PML-negative fibroblasts (15), further supporting the notion of PML and ND10 as mediators of an intrinsic immune defense against herpesvirus infections in general. At the same time, the ND10 constituent hDaxx was identified as a repressor of HCMV IE gene expression and replication (8, 45, 46, 50). hDaxx silences IE gene expression through the action of a histone deacetylase (HDAC), thereby inducing a transcriptionally inactive chromatin state around the major IE enhancer promoter (MIEP) of HCMV (46, 50). Taken together, these findings revealed the ND10 proteins PML and hDaxx as cellular restriction factors that are able to induce silencing of HCMV gene expression, thus controlling viral replication.

However, a successful virus like HCMV has evolved regulatory proteins to antagonize the cellular repression of ND10-associated intrinsic immune factors. As a first line of defense, the HCMV tegument protein pp71, which is delivered to cells upon infection, induces a proteasomal degradation of the hDaxx protein directly after virus entry, thereby relieving hDaxx-mediated inhibition of IE gene expression, as initially noticed by Saffert and Kalejta (46). Consistent with this observation, a pp71 knockout virus inefficiently enters productive infection (7), and depletion of hDaxx annihilates the impaired growth phenotype associated with this virus (8, 45). Furthermore, the IE regulatory protein IE1 targets to ND10 to induce a dispersal of the whole structure by abrogating the SUMOylation (SUMO refers to the small ubiquitin-related modifier) of the major component PML (2, 3, 29, 32, 49). This kind of posttranslational modification of PML was shown to be essential for ND10 formation, since only SUMOylated PML is capable of organizing ND10 accumulations (25, 53). Consequently, genomes of an IE1-negative HCMV mutant have an increased probability of becoming repressed (16), which could be counteracted by the depletion of PML in primary human fibroblasts (48).

Since PML orchestrates ND10 formation, the question remains of whether the negative effect of PML on viral IE gene expression can be related directly to the key component of ND10 structures or, alternatively, is a consequence of PML-mediated recruitment of hDaxx to the optimal subnuclear site, where hDaxx then functions as the actual repressor. Thus, in order to further clarify the role of PML and hDaxx for HCMV replication, a comparative analysis of HCMV replication in knocked down PML and hDaxx (PML-kd and hDaxx-kd, respectively) cells was conducted. Using three recombinant HCMVs (IE1- and pp71-deficient viruses and HCMV with a deletion within the major IE regulatory region [MIERR]), we show a differential complementation of the growth defect of the respective viruses after infection of either hDaxx- or PML-depleted primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs). Furthermore, we generated double-knockdown HFFs devoid of both PML and hDaxx, which revealed an additional enhancement in HCMV replication efficacy compared to the single-knockdown cells. Thus, our results strongly support the notion that PML and hDaxx independently contribute to the silencing of HCMV IE gene expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Primary HFF cells were maintained in Eagle's minimal essential medium (Gibco/Brl, Eggenstein, Germany) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (Cambrex, Verviers, Belgium). HFFs with an siRNA-mediated knockdown of PML (PML-kd cells) or hDaxx (hDaxx-kd cells) as well as fibroblasts with a double knockdown of both ND10 constituents (siDaxx1+siPML-kd cells) were cultured in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (Gibco/Brl) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 5 μg/ml puromycin (PAA Laboratories, Cölbe, Germany). Infection experiments were performed with either the HCMV laboratory strain AD169, a pp71-knockout virus termed AD169/del-pp71, the IE1-deficient virus CR208 (kindly provided by R. Greaves and E. Mocarski) (16), or an HCMV mutant with a deletion of the modulator as well as part of the enhancer sequence of the MIERR, designated AD169/del-MIEP. Virus titers of AD169 as well as of all the AD169-derived recombinant HCMVs were determined via IE1p72-fluorescence as described elsewhere (5), with viral inocula calculated in IE-protein forming units (IEU). Virus titers of CR208 (virus stock kindly provided by M. Nevels, Regensburg, Germany) were determined as described previously (44). Plaque assays were performed by infection of 3.0 × 105 cells per six-well plate with the amount of virus indicated in the figure legends. One hour postinfection the virus supernatant was removed, and overlay medium was added. Following an incubation time as indicated in the figure legends, the cells were stained for plaque counts. For the detection of IE-positive cells, either control or knockdown fibroblasts (3.0 × 105 cells per six-well plate) were infected with either HCMV, strain AD169, or recombinant HCMVs with the amount of virus indicated in the figure legends. The cells were fixed 24 h after infection, followed by immunostaining with either monoclonal antibody p63-27 (for the detection of IE1p72-positive cells) or rabbit antiserum anti-pHM178 (for the detection of IE2p86-positive cells). Then, the number of positive cells/well was determined by epifluorescence microscopy. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and standard deviations were calculated.

Oligonucleotides and plasmids.

Oligonucleotides used for cloning and generation of recombinant bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) as well as sequencing reactions were obtained from Biomers (Ulm, Germany); the respective sequences are listed in Table 1. For generation of the plasmid pHM2499 utilized for retroviral transduction of cells with Flag-hDaxx-expressing lentiviruses, the Flag-hDaxx fusion sequence was amplified in a PCR using primers 5′ Daxx_SpeI and 3′ Daxx_SacII together with plasmid pHM945 as a template (21), followed by insertion of the PCR product via SpeI and SacII into plasmid pHM2070, a derivative of the lentiviral vector pLenti6/V5-D-TOPO (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for construction of plasmids and recombinant BACs and sequencing reactions

| Primer name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| 5′ pp71/pKD13 | GAAGACCCGTTCACCTTTGCGCATCCCCTGACCCTCCCCCCATCCCGCCTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| 3′ pp71/pKD13 | TAGAAATAAATACAGGGAATGGGAAAAACACGCGGGGGAAAAACAAAGAAATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC |

| 5′ IE1 upstream/pKD13 | TGCTATTGGGTCACAGCCGCGTGCCGCGGGTGCGCGCAGAAGAATGTTGCGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| 3′ IE1 upstream/pKD13 | AGATGTACTGCCAAGTAGGAAAGTCCCATAAGGTCATGTACTGGGCATAAATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC |

| 5′ IE1 upstream | CCATTGACGTCAATGGGGTGG |

| 3′ IE1 upstream | TCTGTACCCATCCCAATCTCA |

| 5′ pKD13-pp71 | ACACCTGTCACCGCTGCTATATTTG |

| 3′ pKD13-pp71 | CCGTGATACCCTAATAAAGCACACCG |

| 5′ Daxx_SpeI | TGACTAGTCATGGACTACAAAGACGATGAC |

| 3′ Daxx_SacII | ACTCCGCGGCCTCAGTCATCTGCTTCC |

Generation of recombinant CMVs.

The recombinant CMVs AD169/del-pp71 and AD169/del-MIEP were generated, isolated, and propagated as described previously (35). Briefly, BAC mutagenesis was performed via homologous recombination in Escherichia coli using a linear recombination cassette (reviewed in reference 1). For both viruses, the mutations were inserted into the parental BAC pHB15 (19). The recombination cassettes consisted of a kanamycin resistance gene framed by 50 nucleotides with homology to the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of the respective viral sequences that were deleted. The respective fragments were created by PCR amplification using the primer pair 5′ and 3′ pp71/pKD13 (AD169/del-pp71) as well as the pair 5′ and 3′ IE1 upstream/pKD13 (AD169/del-MIEP) together with plasmid pKD13 as a template, which codes for the kanamycin resistance marker (11). In a next step, the homologous recombination in E. coli was performed as described in detail by Lorz and colleagues (35). Thereafter, the structural integrity of all recombinant BACmids was confirmed via restriction enzyme digestion, Southern blotting, and sequence analysis (with sequencing primers 5′ and 3′ pKD13-pp71 as well as 5′ and 3′ IE1 upstream, respectively). BAC DNA of positive recombinants was isolated using the Nucleobond AX 100 kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Machery Nagel, Düren, Germany). For a subsequent reconstitution of recombinant viruses, HFFs were seeded into six-well dishes at a density of 3.5 × 105 cells/well and transfected with 1 μg of the respective BAC DNA together with expression plasmids for the Cre recombinase and pp71 using the transfection reagent SuperFECT according to the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). One week after transfection, the cells were transferred into 25-cm2 flasks and incubated until a nearly complete cytopathic effect occurred so that the supernatant could be used to infect fresh HFF cultures for preparation of virus stocks.

RNA interference.

Target sequences for RNA interference were selected using siRNA Designer software (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) as described previously (48). The target sequence siDaxx1 against hDaxx has been published previously (10). Additional siRNA sequences were as follows: siPML2, AGATGCAGCTGTATCCAAG (targeting codons 394 to 400 of PML); and siLuci, GTGCGTTGCTAGTACCAAC (targeting luciferase) (48). Oligonucleotides for short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) were designed with the siRNA Hairpin Oligonucleotide Sequence Designer Tool (BD Biosciences) and contained (5′ to 3′) a BamHI site, the respective siRNA sequence, a loop region, the complementary siRNA sequence, an RNA polymerase III termination sequence, an NheI site, and an EcoRI cloning site. In the siC oligonucleotide, which served as a negative control, no complementary sequence was incorporated, thus giving rise to a nonfunctional half-side siRNA. Double-stranded oligonucleotides were cloned into the retroviral vector pSIREN-RetroQ (BD Biosciences), and the resulting plasmids were designated according to their inserted siRNA sequence.

Retroviral transduction.

For the generation of the various knockdown cell lines as well as the corresponding control cells, replication-deficient murine leukemia virus-based retroviruses were prepared by cotransfection of 293FT cells (Invitrogen) with packaging plasmids pHIT60 (kindly provided by K. Überla, Bochum, Germany) and pVSV-G (Invitrogen) (where VSV-G is vesicular stomatitis virus protein G) in combination with the respective pSIREN-RetroQ vectors using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) as described previously (48). Low-passage-number primary HFF cells were incubated thereafter for 24 h with the particular retrovirus supernatants in the presence of 7.5 μg/ml of polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, Deisenhofen, Germany). Stably transduced cell populations were selected by adding 5 μg/ml puromycin to the cell culture medium 48 h posttransduction.

For construction of the double-knockdown cells devoid of both hDaxx and PML (siDaxx1+siPML2-kd) the following strategy was applied. In a first step, siDaxx1-expressing cells with a stable knockdown of hDaxx were generated. Thereafter, the hDaxx-deficient cells had to be infected twice with shPML2 containing retroviruses at an interval of 1 week to yield an efficient PML knockdown.

Reintroduction of a Flag-tagged version of hDaxx in siDaxx1-expressing cells as well as overexpression of Flag-hDaxx in normal HFFs was achieved via retroviral gene transfer using the ViraPower lentiviral expression system (Invitrogen). For this, the Flag-hDaxx fusion sequence was cloned into the pLenti6/V5-D-TOPO vector, resulting in plasmid pHM2499, which was then cotransfected with the ViraPower Packaging Mix into 293T cells according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen) for generation of lentiviral stocks. After transduction of low-passage HFFs, blasticidin-resistant cell populations were selected by adding 2 μg/ml of the antibiotic to the medium.

Real-time PCR.

HFFs (3 × 105 cells/well) were infected with AD169 and AD169/del-MIEP with the amount of viral IEU indicated in the figure legends. Then, 14 h postinfection (hpi), the DNA was extracted from virus-infected cells using a DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen), followed by real-time PCR as described recently (48).

Antibodies, indirect immunofluorescence analysis, and Western blotting.

For indirect immunofluorescence analysis, which was performed as described previously, HFFs were grown on coverslips at a density of 3 × 105 cells per well (48). For Western blotting, extracts from transduced or infected cells were prepared in sodium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer, separated on 8 to 12.5% polyacrylamide gels containing sodium dodecyl sulfate, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Western blotting and chemiluminescence detection were performed as described previously (34). For detection of PML the monoclonal antibody 5E10 (kindly provided by Roel van Driel, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) was used (47). hDaxx was detected either with a rabbit monoclonal antibody from Epitomics (Burlingame, CA) or the rabbit polyclonal antibody M-117 obtained from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies directed against IE1 (monoclonal antibody p63-27), IE2 (anti-pHM178), pp71 (SA2932), and pp65 (monoclonal antibody 65-33) have been described previously (5, 20, 35). Monoclonal antibodies anti-Flag (M2) and anti-β-actin (AC-15) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

RESULTS

Generation of primary human fibroblasts with a stable knockdown of either hDaxx or PML.

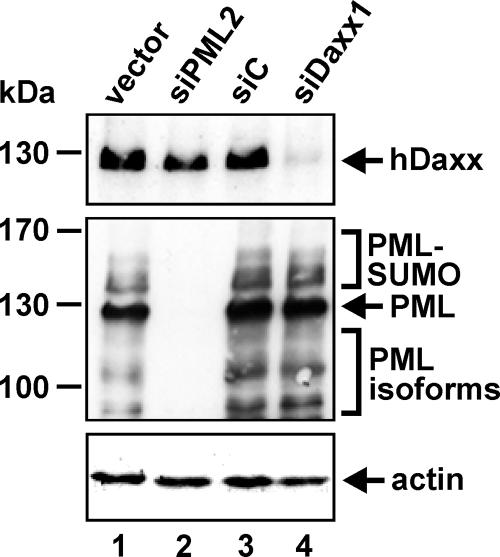

In order to further elucidate the role of hDaxx and PML for HCMV infection in general and in particular to clarify whether PML is directly involved in repressing HCMV replication or serves only as a scaffold protein for hDaxx, we decided to generate primary HFFs with an siRNA-mediated, stable knockdown of either hDaxx or PML in parallel. For this, PML and hDaxx shRNA sequences, designated siPML2 and siDaxx1, respectively, were cloned into the retroviral siRNA expression vector pSIREN-RetroQ, followed by retroviral transduction of primary HFFs (48). As controls, cells containing integrated copies of either the pSIREN-RetroQ vector alone (vector cells) or a functionally inactive half-side shRNA sequence (siC cells) were produced as described previously (48). After selection of puromycin-resistant cell populations, the knockdown of endogenous hDaxx and PML was assessed by Western blotting. As illustrated in Fig. 1, hDaxx expression was substantially reduced in the constructed siDaxx1 cells as detected with an anti-hDaxx rabbit polyclonal antiserum (Fig. 1, lane 4, upper panel). In contrast, PML and β-actin protein levels of siDaxx1 cells remained unaffected (Fig. 1, lane 4, middle and lower panels), confirming the specificity of the hDaxx siRNA sequence used. Similarly, expression of the siPML2 siRNA resulted in a complete down-regulation of PML in the generated PML-kd cells (Fig. 1, lane 2). In addition, hDaxx as well as PML expression of control cells was not altered after retroviral transduction (Fig. 1, lanes 1 and 3). Thus, we were able to generate primary human fibroblast cells in which the protein levels of the respective ND10 constituents, hDaxx or PML, are highly suppressed.

FIG. 1.

Detection of endogenous ND10 proteins hDaxx and PML by Western blotting using cell lysates derived from primary human fibroblasts stably transduced with the respective shRNA expression vectors as indicated. The upper panel shows levels of hDaxx protein detected with the anti-hDaxx rabbit polyclonal antiserum M-117 in various cell types, as indicated above the lanes. The middle panel shows detection of the various SUMOylated as well as non-SUMOylated isoforms of PML using the monoclonal anti-PML antibody 5E10. The major PML isoform is indicated by an arrow. In the lower panel, β-actin detection served as a loading control.

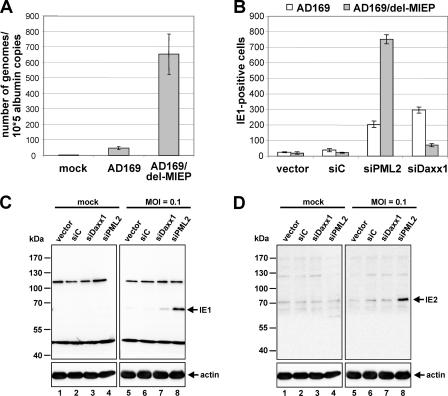

Comparable enhancement of HCMV replication after infection of hDaxx-kd and PML-kd cells as a consequence of more cells initiating IE gene expression.

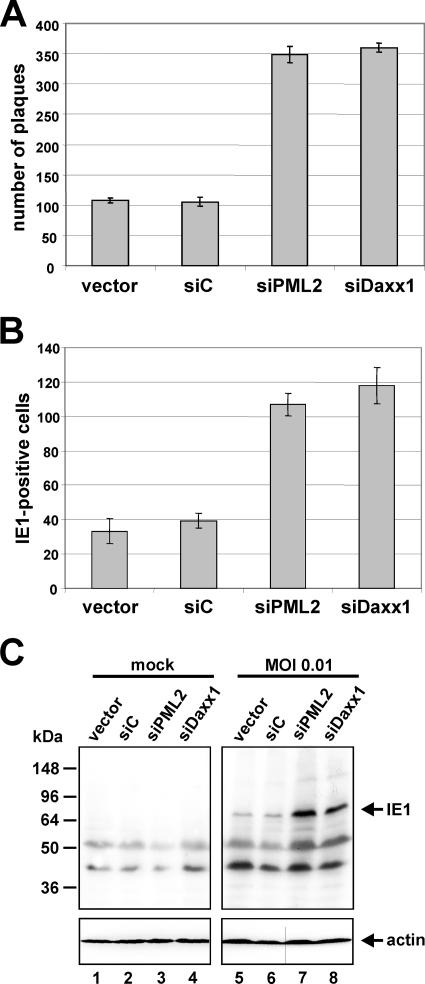

In a next step, a comparative analysis of HCMV infection in the absence of hDaxx or PML was conducted in order to examine the effect of depletion of the respective ND10 protein on HCMV replication. In order to be able to quantify HCMV replication, a standard plaque assay was performed. For this, the generated PML-kd and hDaxx-kd cells together with control fibroblasts were infected with 100 IEU per well of wild-type (wt) HCMV AD169, followed by determination of the number of plaques at 7 days postinfection. Interestingly, we observed an approximately three- to fourfold-higher number of plaques in the knockdown cells than in the control fibroblasts, irrespective of which ND10 component was absent (Fig. 2A). Hence, a lack of PML or hDaxx enhances the plaque-forming ability of wt HCMV AD169 to similar levels at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI).

FIG. 2.

Enhanced replication of HCMV in PML-kd as well as hDaxx-kd cells. Depletion of PML or hDaxx from primary human fibroblasts facilitates the initiation of HCMV gene expression, thus leading to a higher number of infected cells. (A) Quantification of the number of plaques by standard plaque assay 7 days postinfection of retrovirally transduced HFFs (vector, siC, siPML2, and siDaxx1) with 100 IEU of HCMV AD169. (B and C) Enhancement of HCMV IE gene expression in the absence of PML or hDaxx. In panel B, retrovirally transduced HFFs as indicated were infected with 50 IEU/well of HCMV AD169. Cells were fixed at 24 hpi followed by determination of the number of IE1-expressing fibroblasts via indirect immunofluorescence. Panel C shows Western blot analysis of IE1 gene expression 8 h after infection of PML- and hDaxx-negative cells and control fibroblasts with HCMV AD169 (MOI of 0.01).

Previous studies had revealed that the augmented replication efficacy of HCMV in the absence of hDaxx or PML could directly be ascribed to a significant increase in HCMV IE gene expression (8, 45, 46, 48, 50). Consistent with this, we were able to detect three to four times more IE1-positive cells after infection of PML-deficient as well as hDaxx-deficient HFFs than with control fibroblasts (Fig. 2B). Consequently, the initiation of HCMV gene expression is also facilitated to a comparable degree in both knockdown cell lines, regardless of which ND10 factor is missing. The augmented HCMV IE gene expression after infection of cells in which hDaxx and PML levels are strongly reduced could additionally be confirmed by Western blotting experiments with cell lysates of knockdown and control cells harvested at 8 hpi with HCMV AD169 (MOI of 0.01) (Fig. 2C). In summary, our data, obtained with knockdown cells that were generated in parallel, showed that the depletion of either hDaxx or PML in primary human fibroblasts resulted in a comparable enhancement of HCMV replication.

Reintroduction of Flag-hDaxx into hDaxx-kd cells as well as overexpression in normal fibroblasts results in strongly impaired HCMV IE gene expression.

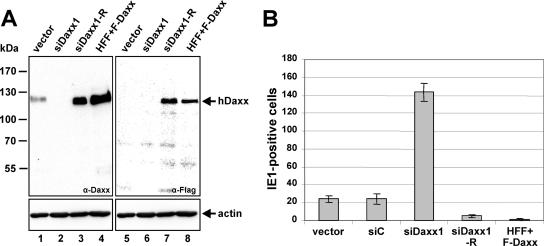

To exclude that any off-target effects of the selected siDaxx1 siRNA contribute to the observed phenotype of siDaxx1 fibroblasts, we decided to reconstitute hDaxx expression in hDaxx-kd cells. Previous studies of our group had demonstrated that overexpression of a protein without the introduction of mutations can already serve as a successful means by which siRNA-mediated gene silencing can be overcome and protein expression be restored, as illustrated in case of PML-kd cells in which PML isoform VI was successfully reintroduced (48). Thus, to achieve a reintroduction of hDaxx in siDaxx1-expressing cells, a similar strategy was followed. In order to be able to discriminate between endogenous and reintroduced hDaxx, a Flag-tagged version of the protein was generated and inserted into the lentiviral vector pLenti6/V5-D-Topo. Next, not only hDaxx-kd fibroblasts but also normal HFFs, which served as positive controls, were transduced with the respective lentiviral vector expressing the Flag-hDaxx fusion protein, resulting in cell populations termed siDaxx1-R (revertant) and HFF+F-Daxx, respectively. Subsequent Western blot analysis revealed that Flag-hDaxx overexpression in the retrovirally transduced cells that were generated induced a strong increase in intracellular hDaxx levels not only in normal HFFs (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 8) but also in siDaxx1-expressing cells (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 7) compared to control fibroblasts (Fig. 3A, lanes 1 and 5) as detected with anti-hDaxx (Fig. 3A, lanes 1 to 4) as well as anti-Flag antibody (Fig. 3A, lanes 5 to 8). The siDaxx1 cells which had been used for the restoration of hDaxx expression proved to be still hDaxx negative (Fig. 3A, lanes 2 and 6).

FIG. 3.

Reconstitution of hDaxx expression in hDaxx-kd cells. (A) Detection of hDaxx protein levels by Western blotting after transduction of siDaxx1 fibroblasts or normal HFFs with the lentiviral Flag-Daxx expression vector pHM2499 resulting in siDaxx1-R and HFF+F-Daxx cells, respectively. hDaxx expression was assayed using an anti-hDaxx monoclonal rabbit antibody (lanes 1 to 4) as well as the anti-Flag monoclonal antibody M2 (lanes 5 to 8). Actin was included as an internal loading control. (B) Examination of HCMV IE gene expression after infection of cells with either a knockdown of hDaxx (siDaxx1) or after introduction of Flag-Daxx expression in siDaxx1-R and HFF+F-Daxx cells. Flag-Daxx-transduced cells (siDaxx1-R and HFF+F-Daxx), hDaxx-negative fibroblasts (siDaxx1), and control cells (vector and siC) were infected in parallel with 25 IEU per well of HCMV AD169. At 24 hpi the cells were stained with an anti-IE1 antibody (monoclonal antibody p63-27) followed by the quantification of IE1-positive fibroblasts. Error bars indicate standard deviations derived from three independent experiments.

Next, the generated siDaxx1-R and HFF+F-Daxx cells together with Daxx-kd and control fibroblasts (vector and siC) were infected with 25 IEU per well of wt AD169, followed by the quantification of IE1-positive cells at 24 hpi. As depicted in Fig. 3B, reintroduction of hDaxx expression in siDaxx1-R cells did not only reverse the phenotype of an enhanced initiation of IE gene expression, as observed in hDaxx-deficient cells (siDaxx1), but also resulted in a decrease in HCMV IE gene expression compared to control fibroblasts (vector and siC). Similar results were obtained for the hDaxx-overexpressing HFFs (HFF+F-Daxx) and can be ascribed to the high abundance of hDaxx present in siDaxx1-R and HFF+F-Daxx cells, since several groups of investigators recently could show that overexpression of hDaxx leads to a marked reduction of HCMV IE gene expression and replication (8, 50). Thus, this experiment ruled out off-target effects of the selected siDaxx1 siRNA.

pp71-mediated relief of hDaxx repression, induced by hDaxx degradation, occurs in the absence of genuine ND10 structures.

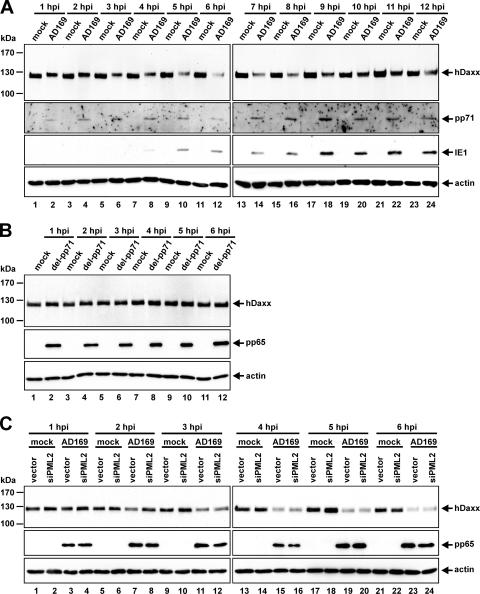

The HCMV tegument protein pp71 has recently been identified as an important antagonist of hDaxx-mediated repression of viral IE transcription by inducing proteasomal degradation of the cellular restriction factor early after infection (46). Although we were also able to detect by immunofluorescence (data not shown) or Western blot analyses a clear reduction of hDaxx levels directly after HCMV infection (Fig. 4A), a residual amount of hDaxx always remained detectable irrespective of the viral load used. The latter observation is exemplarily illustrated in Fig. 4A, showing a Western blot experiment of HFFs infected with AD169 at an MOI of 2. While hDaxx levels were evidently reduced starting at about 3 hpi and reaching minimal levels at 6 hpi, distinct hDaxx signals were detectable at any time point analyzed. At later times of infection, hDaxx levels were stabilized again and at about 12 hpi returned to those observed in mock-infected cells. Thus, pp71 obviously is not able to cause a complete depletion of hDaxx during HCMV infection. It rather seems that preferentially the faster migrating forms of hDaxx are down-regulated after HCMV infection (Fig. 4). These forms most probably reflect the hypophosphorylated proportion of the ND10 protein, as multiple phosphorylation sites within hDaxx have been described (23). In contrast to that, no hDaxx degradation was detectable after infection of HFFs with a pp71-null mutant, AD169/del-pp71 (Fig. 4B), which we constructed by using BAC technology (see Materials and Methods). This result further confirms previous observations by Saffert and Kalejta that pp71 is absolutely necessary for HCMV-induced degradation of hDaxx (46).

FIG. 4.

Examination of hDaxx protein levels in wt AD169- and AD169/del-pp71-infected PML-positive and -negative HFFs. (A) HFFs were either mock infected or infected with wt HCMV AD169 (MOI of 2). Lysates were harvested at the indicated times postinfection (1 to 12 hpi) and analyzed by Western blotting for the expression of hDaxx, pp71, IE1, and actin (actin was included as an internal loading control). (B) Investigation of hDaxx levels after infection with the pp71 deletion virus AD169/del-pp71. HFFs were left uninfected (mock) or were infected with AD169/del-pp71 (MOI of 2). At the indicated hours postinfection cell lysates were sampled and examined for the presence of hDaxx, pp65, or actin via immunoblotting. (C) PML-kd and control HFFs (vector) were infected in parallel with wt AD169. Cell lysates were harvested directly after infection, as indicated, followed by the detection of hDaxx, pp65, or actin protein levels via Western blot analysis.

In PML-kd HFFs, which are devoid of putative ND10 structures, hDaxx can no longer be found in distinct foci but shows a dispersed distribution pattern throughout the nucleus (15, 48). Since pp71 and hDaxx are known to directly interact in ND10 structures initially after infection of normal fibroblasts (21, 26, 36), this raised the interesting question of whether pp71 is still able to induce hDaxx degradation in PML-kd HFFs. To address this issue, PML-deficient as well as control fibroblasts were infected in parallel with AD169 at an MOI of 2 and analyzed for the presence of hDaxx during the first hours postinfection (Fig. 4C). Again, starting at about 3 hpi, a continuous decrease of the intracellular amount of hDaxx was detectable in normal fibroblasts, which occurred to a comparable degree in PML-depleted cells as well. Thus, pp71 is also able to down-regulate hDaxx in siPML2-expressing fibroblasts, indicating that the ND10 localization is not a prerequisite for pp71-mediated hDaxx degradation.

The growth defect of a pp71-deleted HCMV is preferentially alleviated in hDaxx-kd cells.

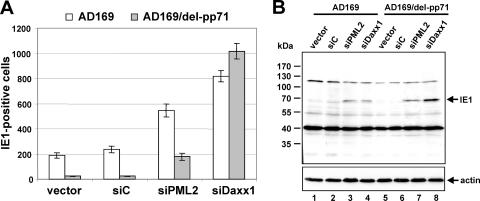

In a next series of experiments using a variety of different HCMV deletion viruses, we intended to solve the question of whether PML is directly involved in inhibiting HCMV IE gene expression. Alternatively, since PML is known to be essential for the integrity of ND10 structures, it would also be conceivable that PML functions as a kind of coordinator in recruiting hDaxx to the optimal subnuclear site, where this protein then serves as the actual repressor. In order to further investigate the contribution of PML and hDaxx to the repression of HCMV replication, we started with analyzing the effect of depletion of the respective ND10 components on the growth properties of the pp71-deficient virus AD169/del-pp71, which fails to degrade hDaxx during infection (Fig. 4B) and thus is not able to overcome hDaxx-mediated repression of IE gene expression (46). To accomplish this, PML- and hDaxx-depleted cells together with control fibroblasts were seeded in six-well dishes for infection with 200 IEU of HCMV AD169 and 500 IEU of AD169/del-pp71, respectively. After 24 h, the cells were immunostained for IE1, and the number of IE1-expressing cells was determined. The infection experiment with wt HCMV served as a control to verify the functionality of the PML- and hDaxx-kd cells. As expected, infection of the knockdown cell lines siPML2 and siDaxx1 with AD169 resulted in a three- to fourfold increase in the amount of IE1-positive cells compared to AD169-infected control HFFs (vector and siC) (Fig. 5A). In contrast to that, initiation of IE gene expression was severely reduced after infection with the pp71-deficient virus AD169/del-pp71 as almost no IE1-positive control cells were detectable due to the strongly impaired growth phenotype associated with this HCMV mutant under low MOI conditions (Fig. 5A) (7). This explains the necessity for using a higher infectious dose of AD169/del-pp71 than of wt HCMV. Infection of PML-depleted cells with AD169/del-pp71 caused an approximately sevenfold increase in the number of IE1-positive cells, indicating that PML contributes to repression of IE gene expression even in the absence of pp71-mediated hDaxx degradation (Fig. 5A). However, when hDaxx-kd cells were infected with AD169/del-pp71, a greater than 40-fold increase in IE1-positive cells was detected, demonstrating that hDaxx acts as the major repressor in the absence of virus-induced hDaxx degradation (Fig. 5A). This observation could additionally be confirmed via Western blotting, where cell lysates of knockdown (siPML2 and siDaxx1) and control cells (vector and siC) were harvested 24 h after infection with either AD169 or AD169/del-pp71 at an MOI of 0.01. While the amounts of IE1 protein were equal in AD169-infected PML- and hDaxx-negative cells, IE1 levels were substantially augmented in AD169/del-pp71-infected hDaxx-kd cells compared to PML-deficient fibroblasts (Fig. 5B). These results allow the conclusion that the growth defect of AD169/del-pp71 is preferentially restored by the depletion of hDaxx, the cellular restriction factor which is normally antagonized by pp71.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of IE gene expression after infection of knockdown (siPML2 and siDaxx) and control cells (vector and siC) with wt AD169 or the pp71 deletion virus AD169/del-pp71. (A) Retrovirally transduced HFFs as indicated were infected with 200 IEU/well of AD169 and 500 IEU/well of AD169/del-pp71, respectively. At 24 hpi the cells were immunostained for the IE1 protein, and the number of IE1-expressing cells was determined. Standard deviations derived from three independent experiments are illustrated by error bars. (B) Western blot experiments for comparison of IE1 gene expression in PML- and hDaxx-deficient cells and control fibroblasts. The indicated cells were infected in parallel with AD169 or AD169/del-pp71 at an MOI of 0.01. At 24 hpi lysates were harvested and assayed for IE1 expression. The detection of actin was used as a loading control.

The impaired growth phenotype associated with the IE1-deletion mutant CR208 is especially abrogated after depletion of PML.

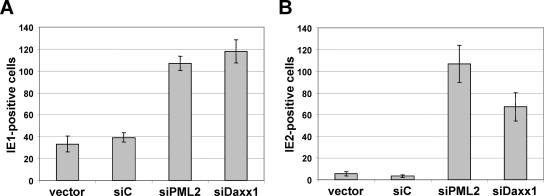

In addition to pp71, the viral IE1 protein is likewise supposed to counteract the repressive activity of ND10 domains on herpesvirus IE gene expression by disrupting these subnuclear structures early during infection (4). Therefore, we were next interested in investigating the replication of the IE1 deletion mutant CR208 in the absence of either PML or hDaxx. For this, siPML2, siDaxx1, and control cells were infected in parallel with 40 IEU per well of wt HCMV and CR208, respectively. The efficiency of the initiation of IE gene expression in the absence of PML and hDaxx was then quantified by counting the IE-positive cells 24 hpi. Infection with wt HCMV again confirmed the functionality of the knockdown cells as illustrated by the three- to fourfold increase in IE1-positive siPML2 and siDaxx1 cells in comparison to control fibroblasts (vector and siC) (Fig. 6A). Comparable to the situation with AD169/del-pp71, very few IE2-positive control cells were visible after infection with the growth-defective IE1 deletion mutant CR208 at a low MOI (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, depletion of the ND10 scaffold protein PML, with a consequent loss of putative ND10 structures, completely abolished the impaired growth phenotype of CR208. This result accords with the notion that IE1 counteracts the antiviral function of ND10 by targeting the posttranslational SUMO-modification of PML, resulting in a dispersal of these subnuclear structures (32, 41). A knockdown of hDaxx, in contrast, only partially rescued the growth defect of CR208 (Fig. 6B). Taken together, these findings indicate that the mutant phenotype of CR208 can especially be overcome by a depletion of PML.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of IE expression levels in PML-kd and hDaxx-kd and control fibroblasts infected with wt HCMV and the IE1-mutant virus CR208, respectively. siPML2, siDaxx1, and control cells (vector and siC) were infected with either 40 IEU/well of wt HCMV (A) or CR208 (B). At 24 hpi the number of IE-positive cells was determined by fluorescence microscopy using either monoclonal antibody p63-27 against IE1 (A) or antiserum anti-pHM178 against IE2 (B). Error bars represent standard deviations from three different experiments.

IE gene expression of a mutant HCMV with a deletion in the MIERR region is particularly stimulated in PML-negative cells.

In a final infection experiment with recombinant HCMVs, a mutant HCMV AD169, termed AD169/del-MIEP, was employed. This virus contains a deletion within the MIERR, ranging from nucleotide position −1798 to −294 relative to the IE1/2 transcription start. In particular, this deletion removed the modulator and unique region of the MIERR together with the distal part of the MIE enhancer sequence comprising three copies of the 21-bp repeat motif; this part of the MIERR has previously been implicated in negative regulation of HCMV IE gene expression in undifferentiated N-Tera 2 cells (30). Infection studies with AD169/del-MIEP in primary human fibroblasts revealed a distinct defect of this mutant virus in IE gene expression, since approximately 14-fold more AD169/del-MIEP input genomes were necessary (Fig. 7A) to achieve the same number of IE1-positive control HFFs (Fig. 7B, vector and siC) compared to infection with wt HCMV AD169 (infection with 25 IEU per well) (Fig. 7B). This observation is consistent with reports by Meier and colleagues, describing the requirement of multiple cis-acting elements in the HCMV MIE distal enhancer for efficient viral IE gene expression in HFFs under low MOI conditions (38, 39).

FIG. 7.

Investigation of AD169/del-MIEP infection in normal HFFs as well as in cells exhibiting a knockdown of PML or hDaxx. (A) Quantitative real-time PCR for evaluation of the viral load after infection of HFFs with wt HCMV AD169 and AD169/del-MIEP, respectively. HFF cells were infected with 25 IEU of AD169 or AD169/del-MIEP. Then, DNA was extracted at 14 hpi, and the number of HCMV genome copies was determined by real-time PCR. Amplification of the cellular albumin gene was utilized as a standard for calculation of cell numbers. (B, C, and D) Comparative analysis of HCMV IE gene expression following infection of knockdown and control cells with AD169/del-MIEP. PML-kd and hDaxx-kd cells together with control fibroblasts were infected in parallel with 25 IEU per well of AD169 and AD169/del-MIEP, respectively. At 24 hpi the amount of IE1-positive cells was evaluated by indirect immunofluorescence analysis (B). HFF cells transduced with the respective siRNA expression vectors as indicated were infected with AD169/del-MIEP at an MOI of 0.1. Cell lysates were prepared at 24 hpi and assayed for IE1 (C) as well as IE2 (D) expression by Western blotting. Detection of actin protein levels served as an internal loading control.

Interestingly, infection of PML-depleted cells resulted in an enormous increase in IE gene expression of AD169/del-MIEP as about 34 times more IE1-positive siPML2 cells than control fibroblasts were detectable (Fig. 7B). The outcome of this experiment indicated that PML is able to exert a strong inhibitory function in the absence of a major part of the MIERR. A lack of hDaxx, on the contrary, stimulated IE1 gene expression of AD169/del-MIEP only threefold (Fig. 7B). Since infection of siDaxx1 cells with wt AD169 resulted in an even ninefold increase in IE1-positive cells compared to control fibroblasts (Fig. 7B), this experiment suggests that deletion of sequences between −1798 to −294 of the MIERR partially abrogates hDaxx-mediated silencing (Fig. 7B). This correlates with data from Woodhall et al. demonstrating that the repressor activity of hDaxx is based on the induction of a transcriptionally inactive chromatin structure around the MIERR via the recruitment of HDACs (50).

Since the knockdown of PML induced such a pronounced enhancement of AD169/del-MIEP IE gene expression, we were also able to detect strongly augmented IE1 and IE2 protein levels via Western blotting in cell lysates of siPML2 HFFs (Fig. 7C and D). Hence, the defect of AD169/del-MIEP in IE gene expression is preferentially complemented by the depletion of PML.

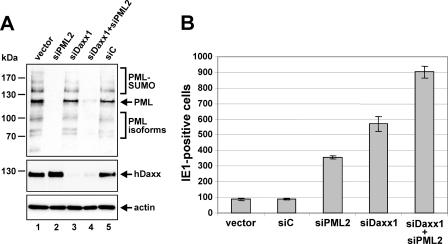

Additional enhancement of HCMV IE gene expression after infection of double-knockdown cells devoid of PML and hDaxx.

In order to obtain further evidence for the assumption that hDaxx and PML independently contribute to the repression of HCMV IE gene expression, we decided to generate primary human fibroblasts in which both ND10 constituents, PML and hDaxx, are depleted. Assuming that hDaxx serves as the major repressor and PML just functions in recruiting hDaxx to ND10 structures, no additional effect on HCMV replication would be expected in the absence of both ND10 factors compared to the individual depletion of hDaxx. To achieve a silencing of hDaxx as well as of PML expression in primary HFFs, hDaxx-negative cells were selected first, followed by two rounds of retroviral transduction with vectors expressing the PML shRNA, siPML2. This resulted in the generation of HFFs in which expression of not only hDaxx but also PML was highly suppressed (Fig. 8A, lane 4). However, it should be mentioned that a detailed comparison with the respective single-knockdown HFFs revealed that the knockdown observed with the double-knockdown cells was slightly less efficient, in particular for PML (Fig. 8A, compare lanes 2, 3, and 4).

FIG. 8.

Verification of the generation of double-knockdown HFFs (siDaxx1+siPML2) devoid of both ND10 constituents, PML and hDaxx, followed by the analysis of HCMV replication in the constructed double-knockdown cells compared to single-knockdown fibroblasts. (A) Western blotting for detection of hDaxx and PML expression in the generated double-knockdown cells, siDaxx1+siPML2. Comparison of PML (upper panel), hDaxx (middle panel), and actin protein levels (lower panel) in whole-cell extracts from double-knockdown (siDaxx1+siPML2), single-knockdown (siPML2, siDaxx1), and control HFFs (vector and siC). (B) Analysis of HCMV IE gene expression after infection of double-knockdown cells in comparison to single-knockdown fibroblasts. The different cell populations as indicated were grown on coverslips in six-well dishes and infected with 100 IEU/well of wt HCMV AD169. At 24 hpi the amount of IE1-expressing cells was assessed via indirect immunofluorescence analysis. Error bars illustrate the standard deviation of three independent determinations.

Finally, the generated double-knockdown cells siDaxx1+siPML2 were infected together with single-knockdown cells (siDaxx1 and siPML2) and control HFFs with 100 IEU of AD169, followed by the quantification of IE1-positive cells at 24 hpi (Fig. 8B). This experiment clearly showed that a loss of both ND10 proteins, PML and hDaxx, resulted in an additional enhancement of HCMV IE gene expression efficacy compared to the single-knockdown cells (Fig. 8B). This observation led us to the conclusion that hDaxx does not constitute the sole repressor of HCMV IE expression; it rather confirmed our hypothesis that PML and hDaxx independently contribute to an intrinsic immune response against HCMV infection.

DISCUSSION

This study was initiated in order to further define the role of the cellular restriction factors PML and hDaxx for repression of HCMV replication. Experimental results of previous, separately performed studies had demonstrated that both ND10 constituents are involved in suppressing the initiation of HCMV gene expression as enhanced IE gene expression was observable in the absence of either PML (48) or hDaxx (8, 45, 46, 50). While recent work from different groups illustrated that the ability of hDaxx to associate with HDACs (22, 33) appears to be responsible for the packaging of viral genomes into a transcriptionally repressive chromatin state almost immediately upon infection (46, 50), the exact mechanism of PML-mediated repression still remains elusive. Although PML has likewise been reported to interact with chromatin-modifying enzymes like HDAC1 and HDAC2 (28, 51) or transcriptional repressors such as SATB1 (31), conclusive evidence for a direct involvement of PML in the suppression of HCMV replication is still lacking. Since a loss of PML correlates with a dispersal of putative ND10 structures, the augmented replication efficiency of HCMV in PML-kd cells could also be an indirect effect of the dissociation of hDaxx, which might be the actual repressor, from ND10 structures that may constitute the optimal subnuclear site for viral DNA repression. Thus, we intended to perform a comparative analysis of HCMV replication in primary HFFs with a stable knockdown of either PML or hDaxx to be able to differentiate between these possibilities.

In previous work we could show that HCMV infection of PML-depleted cells triggers an active recruitment of dissociated residual ND10 components like hDaxx or Sp100 to sites of viral nucleoprotein complexes, resulting in the formation of ND10-like accumulations (48), an observation that was also reported in the context of herpes simplex virus infection (13). The rearrangement of ND10-like structures in HCMV-infected PML-kd cells prompted us to speculate that, even in the absence of PML, remaining ND10 constituents like hDaxx are able to target to viral nucleoprotein complexes in order to exert an antiviral function. This notion was now further supported by the observation that, comparable to the situation in normal fibroblasts, the pp71-induced hDaxx degradation that occurred immediately after infection was likewise detectable in HCMV-infected PML-negative cells, suggesting that pp71 still had to neutralize the repressive effect of hDaxx in the absence of PML. Interestingly, as shown by immunofluorescence analysis, the tight spatial association between pp71 and hDaxx as observed in normal HFFs directly after infection was also visible in siPML2-infected cells as the redistributed hDaxx accumulations perfectly colocalized with distinct pp71 foci which formed immediately after virus entry (N. Tavalai and T. Stamminger, unpublished data).

However, the results of this study clearly show that the existence of genuine PML-containing ND10 structures is not necessary for pp71-mediated hDaxx degradation. In this context, it is of note that, in contradiction to prior findings of Saffert and Kalejta (46), we were not able to detect a complete depletion of hDaxx after infection of normal HFFs as well as PML-kd cells with wt HCMV, as judged by Western blotting (Fig. 4) or immunofluorescence experiments (48). Moreover, the use of gels containing a low percentage of polyacrylamide revealed the existence of distinct hDaxx isoforms that slightly differed in their molecular mass, most probably corresponding to the basal phosphorylated and hyperphosphorylated states of hDaxx as defined by Ecsedy and colleagues (12). Our data suggest that specifically the faster migrating forms of hDaxx, corresponding to the hypophosphorylated isoforms, are down-regulated after HCMV infection. This observation strongly resembles the pp71-mediated degradation of pRb after transient cotransfection where, likewise, preferentially the growth-suppressive, hypophosphorylated forms of pRB have been shown to be depleted by pp71 (27). Furthermore, mutation of a putative hDaxx phosphorylation site identified by microcapillary liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry proved to result in increased hDaxx-mediated transcriptional repression, suggesting that phosphorylation of hDaxx diminishes transcriptional repression (12). In accordance with this, Hollenbach et al. (22) demonstrated that the physical interaction of hDaxx with various proteins of the chromatin matrix including H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, and the chromatin associated-protein Dek as well as HDAC II depends on the phosphorylation status of hDaxx, thereby regulating hDaxx repression activity (22). Consequently, our observation could be a first indication that pp71 preferentially targets the transcriptionally repressive forms of hDaxx.

One major argument for an independent role of PML and hDaxx in the silencing of HCMV IE gene expression is our observation that the depletion of either PML or hDaxx leads to differential complementation of the growth defect of various HCMV deletion mutants. For this, we made use of the fact that HCMV has evolved regulatory proteins to specifically counteract the antiviral effects of either PML or hDaxx. The HCMV tegument protein pp71, for instance, has been shown to normally antagonize hDaxx-mediated repression by inducing the proteasomal degradation of hDaxx initially after infection (46). Consistent with this, the pp71-null mutant AD169/del-pp71 failed to inactivate hDaxx-mediated gene silencing and consequently entered productive infection very inefficiently. Interestingly, the growth defect of the pp71 knockout virus was preferentially diminished by a depletion of hDaxx, the cellular restriction factor which is normally antagonized by pp71. In contrast, the mutant phenotype of the IE1 deletion virus CR208 (16), which is no longer capable of disrupting ND10 structures early after infection (2), was especially overcome by a depletion of PML, the scaffold protein responsible for the assembly of ND10 structures (25, 52).

Next, the replication behavior of a recombinant HCMV AD169/del-MIEP harboring a deletion in the MIERR comprising the modulator and unique region together with the distal part of the enhancer sequence was analyzed. This HCMV mutant failed to efficiently enter productive infection, which is in accordance with previous findings from Meier and colleagues, illustrating the necessity of multiple cis-acting elements located within the distal enhancer region for efficient HCMV IE gene expression (38, 39). Intriguingly, the growth defect associated with AD169/del-MIEP could be particularly reduced by depleting PML since this resulted in a remarkable stimulation of AD169/del-MIEP IE gene expression. We conclude from this observation that a deletion of a large part of the MIERR does not interfere with the ability of PML to inhibit HCMV IE gene expression. Moreover, the deletion of the modulator and distal enhancer region may even augment PML-mediated repression, since the binding of transcription factors that normally antagonize PML-mediated gene silencing might be abrogated (40); this could explain the enhanced repression of AD169/del-MIEP genomes in the presence of PML compared to wt AD169 DNA. A lack of hDaxx, in contrast, only marginally elevated IE transcription of AD169/del-MIEP, indicating that the deleted region of the MIERR contains important target sequences for hDaxx-mediated repression. This is in accordance with data from Woodhall et al. showing that hDaxx-mediated IE gene silencing correlates with the induction of a repressive chromatin structure around the MIERR (50). We conclude from this experimental outcome that hDaxx- and PML-mediated silencing occurs via distinct cis elements of the HCMV genome, indicating that the mechanisms used by both proteins obviously differ.

Finally, our assumption that PML and hDaxx are independently involved in the inhibition of HCMV replication was further reinforced by the observation that depletion of both ND10 proteins resulted in an additional enhancement of HCMV replication in siDaxx1+siPML2 double-knockdown HFFs compared to the respective single-knockdown cells. Consequently, PML not only recruits the transcriptional repressor hDaxx to ND10 and thus sites of incoming viral genomes but also itself possesses the ability to suppress HCMV gene expression, although the exact mechanism of PML-mediated silencing remains to be determined. In summary, the results of our study further support the evolving concept that ND10 structures are part of an antiviral defense mechanism of the cell, with individual components of these structures contributing independently to counteract viral gene expression (14, 15, 43, 48, 50).

Acknowledgments

We thank R. van Driel (Amsterdam, The Netherlands), R. Greaves (London, United Kingdom), G. Hahn (Munich, Germany), E. Mocarski (Atlanta, Georgia), and M. Nevels (Regensburg, Germany) for providing reagents.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB473), the IZKF Erlangen, the elite graduate school BIGSS, and the graduate training program GRK1071.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler, H., M. Messerle, and U. H. Koszinowski. 2003. Cloning of herpesviral genomes as bacterial artificial chromosomes. Rev. Med. Virol. 13111-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn, J. H., E. J. Brignole, III, and G. S. Hayward. 1998. Disruption of PML subnuclear domains by the acidic IE1 protein of human cytomegalovirus is mediated through interaction with PML and may modulate a RING finger-dependent cryptic transactivator function of PML. Mol. Cell. Biol. 184899-4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn, J. H., and G. S. Hayward. 1997. The major immediate-early proteins IE1 and IE2 of human cytomegalovirus colocalize with and disrupt PML-associated nuclear bodies at very early times in infected permissive cells. J. Virol. 714599-4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahn, J. H., and G. S. Hayward. 2000. Disruption of PML-associated nuclear bodies by IE1 correlates with efficient early stages of viral gene expression and DNA replication in human cytomegalovirus infection. Virology 27439-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andreoni, M., M. Faircloth, L. Vugler, and W. J. Britt. 1989. A rapid microneutralization assay for the measurement of neutralizing antibody reactive with human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. Methods 23157-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bieniasz, P. D. 2004. Intrinsic immunity: a front-line defense against viral attack. Nat. Immunol. 51109-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bresnahan, W. A., and T. E. Shenk. 2000. UL82 virion protein activates expression of immediate early viral genes in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9714506-14511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantrell, S. R., and W. A. Bresnahan. 2006. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) UL82 gene product (pp71) relieves hDaxx-mediated repression of HCMV replication. J. Virol. 806188-6191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chelbi-Alix, M. K., L. Pelicano, F. Quignon, M. H. Koken, L. Venturini, M. Stadler, J. Pavlovic, L. Degos, and H. de The. 1995. Induction of the PML protein by interferons in normal and APL cells. Leukemia 92027-2033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, L. Y., and J. D. Chen. 2003. Daxx silencing sensitizes cells to multiple apoptotic pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 237108-7121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 976640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ecsedy, J. A., J. S. Michaelson, and P. Leder. 2003. Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 1 modulates Daxx localization, phosphorylation, and transcriptional activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23950-960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Everett, R. D. 2001. DNA viruses and viral proteins that interact with PML nuclear bodies. Oncogene 207266-7273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everett, R. D., and M. K. Chelbi-Alix. 2007. PML and PML nuclear bodies: implications in antiviral defence. Biochimie 89819-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Everett, R. D., S. Rechter, P. Papior, N. Tavalai, T. Stamminger, and A. Orr. 2006. PML contributes to a cellular mechanism of repression of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection that is inactivated by ICP0. J. Virol. 807995-8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greaves, R. F., and E. S. Mocarski. 1998. Defective growth correlates with reduced accumulation of a viral DNA replication protein after low-multiplicity infection by a human cytomegalovirus ie1 mutant. J. Virol. 72366-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grotzinger, T., T. Sternsdorf, K. Jensen, and H. Will. 1996. Interferon-modulated expression of genes encoding the nuclear-dot-associated proteins Sp100 and promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML). Eur. J. Biochem. 238554-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guldner, H. H., C. Szostecki, T. Grotzinger, and H. Will. 1992. IFN enhance expression of Sp100, an autoantigen in primary biliary cirrhosis. J. Immunol. 1494067-4073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hobom, U., W. Brune, M. Messerle, G. Hahn, and U. H. Koszinowski. 2000. Fast screening procedures for random transposon libraries of cloned herpesvirus genomes: mutational analysis of human cytomegalovirus envelope glycoprotein genes. J. Virol. 747720-7729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hofmann, H., S. Floss, and T. Stamminger. 2000. Covalent modification of the transactivator protein IE2-p86 of human cytomegalovirus by conjugation to the ubiquitin-homologous proteins SUMO-1 and hSMT3b. J. Virol. 742510-2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofmann, H., H. Sindre, and T. Stamminger. 2002. Functional interaction between the pp71 protein of human cytomegalovirus and the PML-interacting protein human Daxx. J. Virol. 765769-5783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hollenbach, A. D., C. J. McPherson, E. J. Mientjes, R. Iyengar, and G. Grosveld. 2002. Daxx and histone deacetylase II associate with chromatin through an interaction with core histones and the chromatin-associated protein Dek. J. Cell Sci. 1153319-3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollenbach, A. D., J. E. Sublett, C. J. McPherson, and G. Grosveld. 1999. The Pax3-FKHR oncoprotein is unresponsive to the Pax3-associated repressor hDaxx. EMBO J. 183702-3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishov, A. M., and G. G. Maul. 1996. The periphery of nuclear domain 10 (ND10) as site of DNA virus deposition. J. Cell Biol. 134815-826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishov, A. M., A. G. Sotnikov, D. Negorev, O. V. Vladimirova, N. Neff, T. Kamitani, E. T. H. Yeh, J. F. Strauss, and G. G. Maul. 1999. PML is critical for ND10 formation and recruits the PML-interacting protein Daxx to this nuclear structure when modified by SUMO-1. J. Cell Biol. 147221-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishov, A. M., O. V. Vladimirova, and G. G. Maul. 2002. Daxx-mediated accumulation of human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp71 at ND10 facilitates initiation of viral infection at these nuclear domains. J. Virol. 767705-7712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalejta, R. F., J. T. Bechtel, and T. Shenk. 2003. Human cytomegalovirus pp71 stimulates cell cycle progression by inducing the proteasome-dependent degradation of the retinoblastoma family of tumor suppressors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 231885-1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan, M. M., T. Nomura, H. Kim, S. C. Kaul, R. Wadhwa, T. Shinagawa, E. Ichikawa-Iwata, S. Zhong, P. P. Pandolfi, and S. Ishii. 2001. Role of PML and PML-RARalpha in Mad-mediated transcriptional repression. Mol. Cell 71233-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korioth, F., G. G. Maul, B. Plachter, T. Stamminger, and J. Frey. 1996. The nuclear domain 10 (ND10) is disrupted by the human cytomegalovirus gene product IE1. Exp. Cell Res. 229155-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kothari, S., J. Baillie, J. G. Sissons, and J. H. Sinclair. 1991. The 21 bp repeat element of the human cytomegalovirus major immediate early enhancer is a negative regulator of gene expression in undifferentiated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 191767-1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar, P. P., O. Bischof, P. K. Purbey, D. Notani, H. Urlaub, A. Dejean, and S. Galande. 2007. Functional interaction between PML and SATB1 regulates chromatin-loop architecture and transcription of the MHC class I locus. Nat. Cell Biol. 945-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee, H. R., D. J. Kim, J. M. Lee, C. Y. Choi, B. Y. Ahn, G. S. Hayward, and J. H. Ahn. 2004. Ability of the human cytomegalovirus IE1 protein to modulate sumoylation of PML correlates with its functional activities in transcriptional regulation and infectivity in cultured fibroblast cells. J. Virol. 786527-6542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, H., C. Leo, J. Zhu, X. Wu, J. O'Neil, E. J. Park, and J. D. Chen. 2000. Sequestration and inhibition of Daxx-mediated transcriptional repression by PML. Mol. Cell. Biol. 201784-1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lischka, P., Z. Toth, M. Thomas, R. Mueller, and T. Stamminger. 2006. The UL69 transactivator protein of human cytomegalovirus interacts with DEXD/H-Box RNA helicase UAP56 to promote cytoplasmic accumulation of unspliced RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 261631-1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorz, K., H. Hofmann, A. Berndt, N. Tavalai, R. Mueller, U. Schlotzer-Schrehardt, and T. Stamminger. 2006. Deletion of open reading frame UL26 from the human cytomegalovirus genome results in reduced viral growth, which involves impaired stability of viral particles. J. Virol. 805423-5434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marshall, K. R., K. V. Rowley, A. Rinaldi, I. P. Nicholson, A. M. Ishov, G. G. Maul, and C. M. Preston. 2002. Activity and intracellular localization of the human cytomegalovirus protein pp71. J. Gen. Virol. 831601-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maul, G. G., A. M. Ishov, and R. D. Everett. 1996. Nuclear domain 10 as preexisting potential replication start sites of herpes simplex virus type-1. Virology 21767-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meier, J. L., M. J. Keller, and J. J. McCoy. 2002. Requirement of multiple cis-acting elements in the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early distal enhancer for viral gene expression and replication. J. Virol. 76313-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meier, J. L., and J. A. Pruessner. 2000. The human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early distal enhancer region is required for efficient viral replication and immediate-early gene expression. J. Virol. 741602-1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meier, J. L., and M. F. Stinski. 1996. Regulation of human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene expression. Intervirology 39331-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muller, S., and A. Dejean. 1999. Viral immediate-early proteins abrogate the modification by SUMO-1 of PML and Sp100 proteins, correlating with nuclear body disruption. J. Virol. 735137-5143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Negorev, D., and G. G. Maul. 2001. Cellular proteins localized at and interacting within ND10/PML nuclear bodies/PODs suggest functions of a nuclear depot. Oncogene 207234-7242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Negorev, D. G., O. V. Vladimirova, A. Ivanov, F. Rauscher, III, and G. G. Maul. 2006. Differential role of Sp100 isoforms in interferon-mediated repression of herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early protein expression. J. Virol. 808019-8029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paulus, C., S. Krauss, and M. Nevels. 2006. A human cytomegalovirus antagonist of type I IFN-dependent signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1033840-3845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Preston, C. M., and M. J. Nicholl. 2006. Role of the cellular protein hDaxx in human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene expression. J Gen. Virol. 871113-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saffert, R. T., and R. F. Kalejta. 2006. Inactivating a cellular intrinsic immune defense mediated by Daxx is the mechanism through which the human cytomegalovirus pp71 protein stimulates viral immediate-early gene expression. J. Virol. 803863-3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stuurman, N., G. A. de, A. Floore, A. Josso, B. Humbel, J. L. de, and D. R. van. 1992. A monoclonal antibody recognizing nuclear matrix-associated nuclear bodies. J. Cell Sci. 101773-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tavalai, N., P. Papior, S. Rechter, M. Leis, and T. Stamminger. 2006. Evidence for a role of the cellular ND10 protein PML in mediating intrinsic immunity against human cytomegalovirus infections. J. Virol. 808006-8018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilkinson, G. W., C. Kelly, J. H. Sinclair, and C. Rickards. 1998. Disruption of PML-associated nuclear bodies mediated by the human cytomegalovirus major immediate early gene product. J. Gen. Virol. 791233-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woodhall, D. L., I. J. Groves, M. B. Reeves, G. Wilkinson, and J. H. Sinclair. 2006. Human Daxx-mediated repression of human cytomegalovirus gene expression correlates with a repressive chromatin structure around the major immediate early promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 28137652-37660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu, W. S., S. Vallian, E. Seto, W. M. Yang, D. Edmondson, S. Roth, and K. S. Chang. 2001. The growth suppressor PML represses transcription by functionally and physically interacting with histone deacetylases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 212259-2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhong, S., S. Muller, S. Ronchetti, P. Freemont, A. Dejean, and P. P. Pandolfi. 1999. PML is essential for proper formation of the nuclear body. Blood 94489A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhong, S., S. Muller, S. Ronchetti, P. S. Freemont, A. Dejean, and P. P. Pandolfi. 2000. Role of SUMO-1-modified PML in nuclear body formation. Blood 952748-2753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]