Abstract

The structural context of a CD4+ T-cell epitope is known to influence immunodominance at the level of antigen processing, but general rules have not emerged. Dominant epitopes of influenza virus hemagglutinin are found to be localized to the C-terminal flanks of conformationally stable segments identified by low crystallographic B-factors or high COREX residue stabilities. The bias toward C-terminal flanks is distinctive for antigens from the influenza virus. Dominant epitopes in antigens/allergens from other sources also localize to the flanks of stable segments but are found on either N- or C-terminal flanks. Thus, dominance arises from preferential endoproteolytic nicking between stable segments followed by loading of fragment terminal regions into antigen-presenting proteins. This mechanism probably arose in order to direct CD4+ responses onto sequences that are conserved for structure and function. Structure-guided presentation could enhance protection against genetically drifting influenza virus variants but most likely reduces protection against new viral subtypes.

Particular CD4+ T cells may have a positive or negative role in the response to influenza infection (7, 26, 35). Thus, CD4+ T-cell epitope immunodominance could have a major impact on recovery from disease and protection against new infections. The importance of specific CD4+ responses in protection against other viruses is evident in the appearance of immune escape mutations. Mutation of a CD4+ epitope was shown to be a viable mechanism for immune escape by lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in mice (11), and CD4+ escape mutants have been described in chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections (53, 69, 70). Some human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) mutations whose selection cannot be explained by escape from CD8+ T cells are located in CD4+ epitopes (3). CD4+ epitopes in HIV appear to be less conserved than CD8+ epitopes, possibly for the simple reason that CD4+ epitopes are longer (64). Some evidence suggests that breadth of specificity in the CD4+ response correlates with protection against HCV (16, 60). Thus, strong CD4+ epitope immunodominance may be advantageous to the virus and disadvantageous to the host. Understanding the molecular basis of CD4+ epitope immunodominance is of crucial importance to vaccine design.

Epitope dominance can be based on the frequency of response in a population of individuals or the intensity of response in a particular individual, although dominant epitopes often satisfy both definitions (15, 21). Peptide affinities for class II major histocompatibility (MHC) antigen-presenting proteins have not explained CD4+ epitope immunodominance as well as peptide affinities for class I MHC proteins have explained CD8+ epitope immunodominance (76). The class II MHC protein has been distinguished from the class I MHC protein in that the class II MHC protein is exquisitely adapted for nonspecific binding to peptides (38). The presence or absence of certain class II MHC alleles influences the dominance of particular epitopes (1, 43). However, peptide affinity for the class II MHC protein is a poor predictor of epitope dominance in influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) (22) and other antigens (40, 46, 52). The weak influence of MHC-peptide affinity on epitope dominance is further indicated by the frequent observation of “promiscuous” or “universal” CD4+ epitopes, which are dominant in multiple MHC backgrounds (17, 20, 28, 39, 50, 54, 60). Thus, other factors exert a major influence on epitope immunogenicity.

An epitope's structural context has been shown to influence CD4+ T-cell epitope dominance at the level of antigen processing (4, 9, 14, 45, 62, 65, 67, 68, 73), but a general relationship between structure and immunodominance has not been described. Processing of CD4+ epitopes occurs in a lysosome-like compartment, where there is no evidence for ATP-dependent protein-unfolding mechanisms other than lysosomal acidification (72). Protease-sensitive sites in proteins have been correlated with conformational flexibility, as reported by high crystallographic B-factors (8, 19, 36, 49), and dominant CD4+ epitopes have been shown to occur adjacent to flexible antigen segments identified by crystallographic B-factors in several model antigens (42), tetanus toxoid (17), Hsp10s (8), and HIV gp120 (15).

In the present study, published epitope maps are compared to profiles of conformational stability in influenza virus HA and eight other well-studied antigens/allergens. The profiles of conformational stability were generated with the COREX algorithm, which evaluates the dominant forces of protein folding, namely, the hydrophobic interaction and conformational entropy (33). The analysis yields information about probable pathways of proteolytic antigen processing and indicates that dominant CD4+ epitopes arise on the flanks of stable antigen segments, which most likely correspond to proteolytic processing intermediates. The relationship of epitope dominance to antigen structure focuses immunity onto conserved antigen sequences but also creates a mechanism for immune evasion by pathogens such as influenza virus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Calculation of epitope scores, alignment of data sets, and analysis of correlation versus offset were performed using Microsoft Excel. Significance tests were performed using GraphPad Prism or Instat. Residue-stability profiles were calculated using the COREX implementation at http://www.best.utmb.edu/BEST/ with default values for all parameters. Entropy factors were estimated with the COREX implementation, but they typically resulted in residue stability profiles with less dispersion than could be obtained with a slightly lower entropy factor. Thus, the entropy factor was adjusted downward by 0.02 from the estimated value for all residue stability calculations. Antigen/allergen-specific details are provided below. Multiple sequence alignments were performed with ClustalW (10). Sequence entropy calculations were performed with BioEdit (27).

Identification of dominance peaks. (i) HA.

Proliferative responses to HA in 30 human subjects reported by Gelder et al. (22-24) were converted to stimulation indices (SI) by dividing the response (cpm) for each peptide pool by the response for the unstimulated control. The response was scored as positive for a given subject if the SI was greater than 4. Epitope scores (expressed as the percentage of subjects responding) were assigned to residues according to the frequency of response to the peptide pool that contained the residue. Each pool of five 15-mer peptides spanned 35 residues, and the 24 pools spanned the complete sequence of HA. The peptide pools partially overlapped, and therefore residues that appeared in two peptide pools were assigned the average of the two scores. Dominance peaks were identified as local maxima in the smoothed profile of epitope scores. Smoothing facilitated the identification of a single amino acid residue at the center of each dominance peak, which was characterized by a broad plateau in the raw profile. Smoothing did not affect the number of dominance peaks. The profile of raw epitope scores was smoothed with a 23-residue moving window average. A “first-derivative” profile was generated by taking the difference between scores for the current residue and the preceding residue, and then this profile was smoothed with a 13-residue moving window average. Dominance peaks were assigned to the residues where the smoothed first derivative changes from positive to negative. For Fig. 1, the responses of H3-infected C57BL/6 mice and of H1-infected HLA-DR1 trangenic mice were assigned to residues according to the average response to the peptides that contained the residue. In the study using H1-infected HLA-DR1 mice, responses had been scored according to the percentage of the maximum, defined by the number of enzyme-linked immunospots (ELISPOTs) obtained for peptide 63 (corresponding to 443 to 465 in the x31 strain) as follows: negative (less than 6%), weak (6 to 24%), moderate (25 to 60%), or strong (greater than 60%). In the present work, peptides were assigned scores corresponding to the average response for the range: negative (3%), weak (15%), moderate (43%), or strong (81%). Residues that appeared in multiple peptides were assigned the average of the scores.

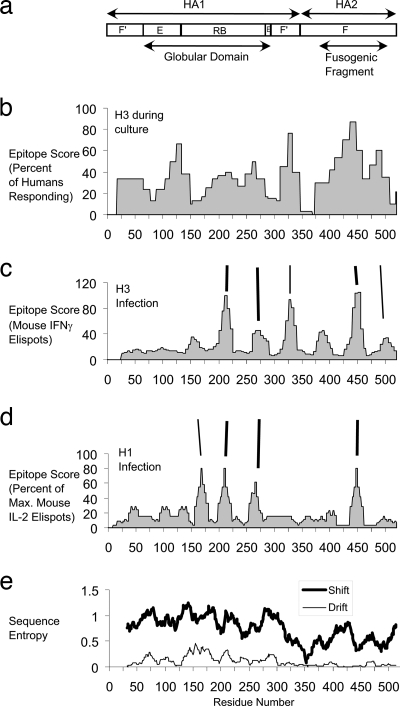

FIG. 1.

Similar profiles of CD4+ epitope dominance for influenza virus HA in mice and humans infected with H3 or H1 strains of virus. (a) Schematic diagram of HA subdomains. F′, HA1 portion of fusion domain; E, vestigial esterase; RB, receptor binding; F, HA2 portion of fusion domain. (b) Profile of epitope scores for a population of 30 human subjects. (c) Profile of epitope scores for a group of C57BL/6 mice that had been inflected with an H3N1 strain. IFNγ, gamma interferon. (d) Profile of epitope scores for a group of HLA-DR1 transgenic mice that had been infected with an H1N1 strain. IL-2, interleukin-2. (e) Profiles of sequence entropy calculated for HA molecules representing five HA subtypes (“Shift”) or for 135 HA molecules representing different isolates of viral subtype H3N2 (“Drift”). Vertical lines indicate peaks of epitope dominance that are shared in all three studies (heavy lines) or shared between only two studies (light lines).

(ii) Phl p 1.

The responses of T-cell lines or clones from nine allergic patients reported by Schenk et al. (59) were based on proliferation stimulated by 12-mer peptides spanning Phl p 1 with nine-residue overlaps. The authors scored the response for a given clone as positive if the SI was greater than 10. Epitope scores were assigned to residues according to the number of patients whose lines or clones responded to the peptide that contained the residue. The profile of raw epitope scores was smoothed with a seven-residue moving window average. The first-derivative profile generated as described for HA was smoothed with a seven-residue moving window average. Dominance peaks were assigned as for HA.

(iii) Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ag85A.

The responses of 10 tuberculin-positive subjects reported by Launois et al. (44) were based on lymphocyte proliferation stimulated by 20-mer peptides spanning Ag85A with 10-residue overlaps. The authors scored the response for a given subject as positive if the SI was greater than 5. Epitope scores (expressed as the percent of subjects responding) were assigned to residues according to the average frequency of response to the peptides that contained the residue. The profile of raw epitope scores was smoothed with a 13-residue moving window average. The first-derivative profile generated as for HA was smoothed with a 13-residue moving window average. Dominance peaks were assigned as for HA.

(iv) M. tuberculosis Mpb70.

The responses of 14 BCG-vaccinated subjects reported by Al-Attiyah et al. (2) were based on lymphocyte proliferation stimulated by 25-mer peptides spanning Mpb70 with 10-residue overlaps. The authors scored the response for a given subject as positive if the SI was greater than 3. Epitope scores (expressed as the percentage of subjects responding) were assigned to residues according to the frequency of response to the peptide that contained the residue. Residues that appeared in multiple peptides were assigned the average of the scores. The profile of raw epitope scores was smoothed with a 15-residue moving window average. The first-derivative profile generated as for HA was smoothed with a 15-residue moving window average. Dominance peaks were assigned as for HA.

(v) Mycobacterium bovis Ag85B.

The responses of 15 BCG-vaccinated subjects reported by Roche et al. (57) were based on lymphocyte proliferation stimulated by 20-mer peptides spanning Ag85B with 10-residue overlaps. The authors scored the response for a given subject as positive if the SI was greater than 4. Epitope scores (expressed as the percentage of subjects responding) were assigned to residues according to the frequency of response to the peptide that contained the residue. Residues that appeared in multiple peptides were assigned the average of the scores. The profile of raw epitope scores was smoothed with a 17-residue moving window average. The first-derivative profile generated as for HA was smoothed with a 13-residue moving window average. Dominance peaks were assigned as for HA.

(vi) M. tuberculosis Hsp65.

The responses of immunized Lewis rats reported by Moudgil et al. (47) were based on lymphocyte proliferation stimulated by 15-mer peptides spanning Hsp65 with 11-residue overlaps. Epitope scores (expressed as thousands of cpm) were assigned to residues according to the response to the peptide that contained the residue. Residues that appeared in multiple peptides were assigned the average of the scores. The profile of raw epitope scores was smoothed with a 15-residue moving window average. The first-derivative profile generated as for HA was smoothed with a five-residue moving window average. Dominance peaks were assigned as for HA.

(vii) Bet v 1.

The responses of 22 T-cell clones from nine allergic patients reported by Dormann et al. (18) were based on proliferation stimulated by 12-mer peptides spanning Bet v 1 with 10-residue overlaps. The authors scored the response for a given clone as positive if the SI was greater than 5. Epitope scores were assigned to residues according to the frequency that T-cell clones responded to the peptide that contained the residue. The profile of raw epitope scores was smoothed with a seven-residue moving window average. The first-derivative profile generated as for HA was smoothed with a seven-residue moving window average. Dominance peaks were assigned as for HA.

(viii) Ves v 5.

The responses of T-cell lines from 13 allergic patients reported by Bohle et al. (6) were based on proliferation stimulated by 12-mer peptides spanning Ves v 5 with nine-residue overlaps. The authors scored the response for a given clone as positive if the SI was greater than 4. Epitope scores were assigned to residues according to the number of patients whose lines responded to the peptide that contained the residue. The profile of raw epitope scores was smoothed with a 15-residue moving window average. The first-derivative profile generated as for HA was smoothed with a seven-residue moving window average. Dominance peaks were assigned as for HA.

(ix) HCV NS3 helicase domain.

The responses of 20 HCV patients reported by Gerlach et al. (25) were based on lymphocyte proliferation stimulated by 20-mer peptides spanning the NS3 helicase with 10-residue overlaps. The authors scored the response for a given patient as positive if the SI was greater than 3. Epitope scores were assigned to residues according to the number of responses to the peptide(s) that contained the residue. Residues that appeared in multiple peptides were assigned the average of the scores. The profile of raw epitope scores was smoothed with a 15-residue moving window average. The first-derivative profile generated as for HA by was smoothed with a 15-residue moving window average. Dominance peaks were assigned as for HA.

Identification of stable and unstable segments. (i) HA.

A composite stability profile, including residue stabilities for the neutral-pH globular domain, a portion of the neutral-pH stem, and the entire low-pH fusogenic fragment, was used for the identification of stable and unstable segments. Stability profiles were calculated for the globular domain at neutral pH (residues 73 to 286 from PDB:2VIU, entropy factor 1.0), the stem at neutral pH (residues 25 to 72 and 287 to 524 from PDB:2VIU, entropy factor 0.92), and the fusogenic fragment (residues 27 to 32 and 385 to 507 from PDB:1HTM, chain D, entropy factor 0.80). For the identification of stability minima and maxima, the first-derivative profile was smoothed with a 15-residue moving window average and then the local minima and maxima were assigned to residues where the smoothed first derivative became positive and negative, respectively. For the H1, H5, and H9 stability profiles, COREX profiles were calculated for aligned portions of the corresponding structures. Input structures and entropy factors, respectively, were as follows: for the H1 globular domain, PDB:1RU7 and 1.009, and for the H1 stem, PDB:1RU7 and 0.932; for the H5 globular domain, PDB:1JSM and 1.008, and for the H5 stem, PDB:1JSM and 0.931; and for the H9 globular domain, PDB:1JSD and 0.980, and for the H9 stem, PDB:1JSD and 0.940.

(ii) Phl p 1.

A stability profile was calculated for a structure of Phl p 1 that was generated by Swiss-Model (61) (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/) based on the incomplete crystal structures of Phl p 1 (PDB:1N10, chains A and B) and the complete amino acid sequence (accession no. P43213). Automated procedures in Swiss-Model constructed a chemically reasonable structure for a loop (residues 29 to 38 of the mature Phl p 1) that was missing from the experimentally determined structures. The COREX calculation employed an entropy factor of 0.850. For the identification of stability minima and maxima, the first-derivative profile was smoothed with a 15-residue moving window average.

(iii) M. tuberculosis Ag85A.

A stability profile was calculated for the crystal structure of Ag85A (PDB:1SFR, chain A), using an entropy factor of 1.058. For the identification of stability minima and maxima, the first-derivative profile was smoothed with a 15-residue moving window average. The M. tuberculosis Ag85A sequence has 76% identity to the M. bovis Ag85B sequence.

(iv) M. tuberculosis Mpb70.

A stability profile was calculated for the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structure of Mpb70 (PDB:1NYO, model 1), using an entropy factor of 0.93 and default values for all other parameters. For the identification of stability minima and maxima, the first-derivative profile was smoothed with a 15-residue moving window average.

(v) M. bovis Ag85B.

A stability profile was calculated for the crystal structure of M. tuberculosis Ag85B (PDB:1F0N, chain A), using an entropy factor of 1.058 and all other parameters set to default values. For the identification of stability minima and maxima, the first-derivative profile was smoothed with a 15-residue moving window average. The M. bovis Ag85B sequence has 99% identity to the M. tuberculosis Ag85B sequence and 76% identity to the M. tuberculosis Ag85A sequence.

(vi) M. tuberculosis Hsp65.

A stability profile was calculated for a “homology model” of M. tuberculosis Hsp65 (accession no. P0A520) that was based on crystal structures of the same protein (PDB:1SJP, chains A and B). The homology model was prepared using Swiss-Model. Automated procedures in Swiss-Model constructed a chemically reasonable structure for a loop (residues 81 to 88) that was missing from the experimentally determined structures. Due to the large size of Hsp65, residue stabilities for the apical and equatorial domains were calculated separately and then combined into a composite stability profile. For the apical domain (residues 188 to 372), the COREX calculation employed an entropy factor of 0.952 and default values for all other parameters. For the equatorial domain (residues 1 to 187 and 373 to 525), the calculation used Monte Carlo sampling at 5,000 samples per partition, an entropy factor of 0.957, and default values for all other parameters. For the identification of stability minima and maxima, the first-derivative profile was smoothed with a 15-residue moving window average.

(vii) Bet v 1.

A stability profile was calculated for the NMR structure of Bet v 1 (PDB:1BTV, model 1) using an entropy factor of 0.90 and default values for all other parameters. For the identification of stability minima and maxima, the first-derivative profile was smoothed with a 15-residue moving window average.

(viii) Ves v 5.

A stability profile was calculated for the crystal structure of Ves v 5 (PDB:1QNX), using an entropy factor of 0.994 and default values for all other parameters. For the identification of stability minima and maxima, the first-derivative profile was smoothed with a seven-residue moving window average.

(ix) HCV NS3 helicase domain.

A stability profile was calculated for a homology model of the NS3 helicase domain (HCV genotype 1a; accession no. P26664) that was based on the following structures (percent identity): PDB:1CU1 (99%), PDB:1HEI (94%), PDB:8OHM (96%), and PDB:2F55 (97%). The homology model was prepared using Swiss-Model. The stability profile was calculated using COREX with Monte Carlo sampling at 10,000 samples per partition, an entropy factor of 0.99, and all other parameters set to default values. For the identification of stability minima and maxima the first-derivative profile was smoothed with a 15-residue moving window average.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Dominance of HA CD4+ epitopes in humans and mice.

The hypothesis that antigen structure controls CD4+ epitope immunodominance implies that dominance patterns should be similar in different MHC backgrounds and even different animal species. CD4+ epitope-mapping data for HA have been compiled from studies of humans and two strains of mice. Gelder and coworkers mapped HA epitopes by proliferation of T-cell lines obtained from 30 human subjects that had been naturally exposed to influenza virus and, in some cases, had also been immunized with a subunit vaccine (22-24). Woodland and coworkers mapped HA epitopes by gamma interferon secretion from splenocytes pooled from a group of C57BL/6 mice that had been infected with an H3N2 strain of influenza virus (12). Sant and coworkers mapped HA epitopes by interleukin-2 secretion from splenocytes pooled from a group of HLA-DR1 transgenic mice that had been infected with an H1N1 strain of influenza virus (55). In order to facilitate the comparison of epitope dominance between the different studies and with structural parameters, the epitope-mapping data were converted from a peptide basis to an amino acid residue basis by assigning an “epitope score” to each residue in HA according to the frequency of response in humans or average intensity of response in mice elicited by the overlapping peptides that contain the residue. In spite of differences in host, viral strain, and method of detection, the profiles of epitope scores from the human and mouse studies are similar in terms of the numbers and locations of peaks (Fig. 1).

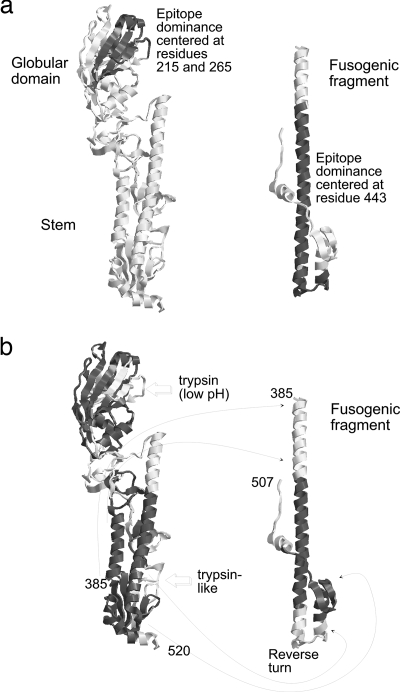

The most outstanding similarity in the CD4 T-cell epitope profiles is the coincidence of three immunodominant regions (centered at residues 215, 265, and 443) in the human and both mouse profiles (Fig. 1 and 2a). The human profile exhibits additional dominant regions (at residues 333 and 490) that are shared in common with the profile for H3-infected C57BL/6 mice. Humans have a distinct dominant region in the globular domain (at residue 130) that is not shared by either group of mice. The H3-infected C57BL/6 mice have a dominant region in the stem (at residue 390) that is not shared by the H1-infected HLA-DR1 mice but which is encompassed by a large shoulder in the peak of dominance in humans at residue 443. A dominant region in the globular domain (at residue 172) in the H1-infected HLA-DR1 mice appears to be shared with the H3-infected C57BL/6 mice but is shifted to a slightly more N-terminal position in the H3-infected mice.

FIG. 2.

Structural context of structurally stable segments and regions of conserved epitope dominance in the HA precursor and the low-pH conformation of the HA fusogenic fragment. In panel a, regions of above-average epitope score that were observed in humans and mice are shaded (dark gray). Note that the region of dominance centered at residue 443 is not shaded in the stem of the HA precursor. In panel b, regions of above-average residue stability are shaded (dark gray). Note that some stable regions in the stem of the precursor become unstable in the fusogenic fragment and vice versa. Arrows indicate established proteolytic cleavage sites in HA. Lines connect equivalent positions in the neutral-pH structure (PDB:1HA0) and fusogenic fragment (PDB:1HTM).

In principle, the similarity in dominance profiles could be due to similar peptide-binding selectivity by class II MHC proteins. Testing this hypothesis is complicated by the differences in MHC alleles present and differences in the HA subtypes to which the individuals have been exposed. Although the HLA-DR1 mice have the most frequently observed MHC allele of humans, these mice were exposed to an HA subtype (H1) that is different from the HA subtype used to culture T-cell lines from human subjects (H3). In the two experimental infections of mice, the mouse strains had different MHC alleles and the viral subtypes were different. Given the existence of conserved epitopes, the peptide-binding selectivity hypothesis predicts that they would occur in conserved HA sequences. However, at least two of the conserved, dominant segments (at residues 215 and 265) are located in regions of the HA sequence that are poorly conserved across HA subtypes (Fig. 1e, trace labeled “Shift”). Epitopes in these regions of the H1 and H3 subtype viruses could share no more than 50% identity. Thus, factors other than peptide selectivity in the MHC protein are likely to be responsible for the similarity of the T-cell epitope dominance profiles.

CD4+ epitopes adjacent to flexible, protease-sensitive HA segments.

The similarity of HA epitope dominance profiles obtained for diverse subjects and different viral subtypes suggests that the conserved HA structure shapes the dominance profile by influencing HA processing and/or peptide loading. Conserved, dominant epitopes at residues 215, 265, 333, and 490 lie adjacent to established protease-sensitive sites in HA (Fig. 3b). The epitopes at residues 215 and 265 flank the tryptic cleavage site observed following residue 240 in the globular domain (74). This site becomes sensitive to trypsin only after HA undergoes the low-pH conformational change (63), which is expected in an antigen-processing compartment. The epitope at residue 333 lies at the C terminus of HA1, which is produced by a trypsin-like cleavage following residue 344 of the HA precursor in all infected tissues (74). The epitope at residue 490 lies at the C terminus of the HA ectodomain, which is the soluble fragment generated by bromelain cleavage of the membrane-bound protein (74). Local regions of conformational flexibility in the native or acid-induced conformation of HA most likely promote cleavage by trypsin and bromelain, and the same regions of flexibility are expected to promote cleavage by antigen-processing proteases and therefore facilitate presentation of adjacent epitopes.

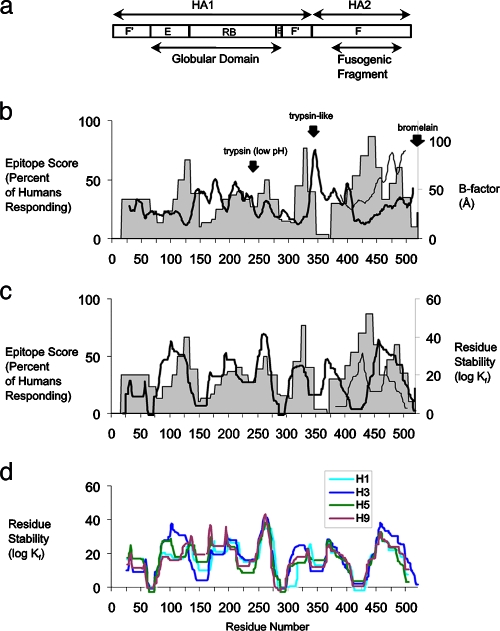

FIG. 3.

Influenza virus HA epitopes cluster on the flanks of structurally stable HA segments. (a) Schematic diagram of HA subdomains (as in Fig. 1a). (b) Profiles of crystallographic B-factors for the subtype H3 precursor (heavy line) and fusogenic fragment (light line) superimposed on the profile of epitope scores for humans (as in Fig. 1b) and illustrating the locations of known proteolytic cleavage sites (arrows) (74). (c) Profiles of residue stability for the subtype H3 precursor (heavy line) and fusogenic fragment (light line) superimposed on the profile of epitope scores for humans (as in Fig. 1b). (d) Residue stability for four subtypes of HA. Residues are numbered according to the sequence of the HA precursor from the x31 strain of influenza virus (UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot accession no. P03437).

The possibility of a more general correlation of epitope dominance and structural flexibility in HA was examined by using B-factors reported with crystallographic structures of the uncleaved precursor and the fusogenic domain of HA. The structure of the HA precursor at neutral pH might be regarded as a poor model for the structure of the HA1 or HA2 protein at low pH. However, the three-dimensional structure of many proteins generally and of the HA globular domain in particular remain essentially the same at low pH (41, 63, 74). B-factors describe the uncertainty in the positions of atoms, which are less well determined in flexible protein segments (56). Protein segments characterized by high backbone atom B-factors are associated with sensitivity to proteolysis (36). HA segments that are likely to be protease sensitive are located in the RB subdomain, at the HA1-HA2 cleavage site loop, and in the N-terminal portion of the F subdomain (Fig. 3b). Since some of the peaks of epitope dominance occur in sequences adjacent to known proteolytic cleavage sites, the correlation of epitope scores and B-factors was evaluated for various N-terminal or C-terminal offsets of one data set relative to the other, effectively correlating epitopes with adjacent regions of flexibility.

The correlations were evaluated on a peptide basis in order to properly weight the sampling frequency: i.e., the average epitope score for a peptide sequence was paired with the average B-factor for the same sequence or a similarly sized sequence at a given offset from the peptide. Using B-factors for the HA precursor, human epitopes were anticorrelated with B-factors, achieving an optimal value (rmax) of −0.60 (P = 0.003) with offset −10, suggesting that epitopes tend to be centered 10 residues C terminal from regions of low flexibility (Fig. 4a, upper panel).

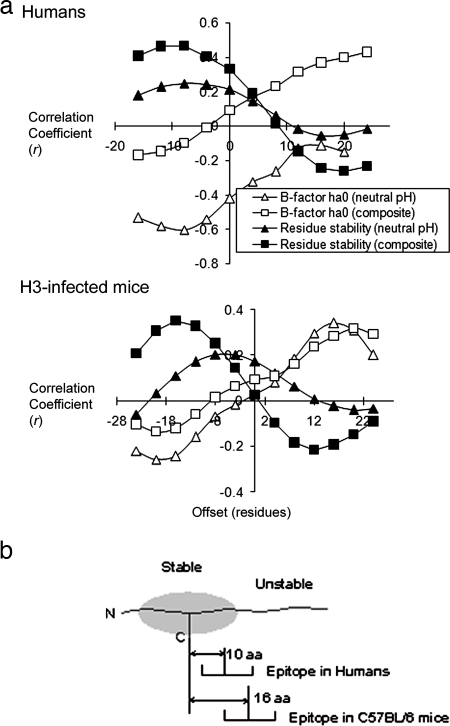

FIG. 4.

Spatial relationship of CD4+ epitopes to stable antigen segments in influenza virus HA. (a) Correlation versus offset using epitope scores from studies of humans or H3-infected mice. The y axis indicates the center of the epitope, and the offset indicates the relative position of the stable/unstable segment being correlated (positive offset indicates C terminal). High B-factors indicate low stability, and thus correlations involving B-factor and residue stability generally have the opposite sign. In panel b, the average distances of mouse and human epitopes from the centers of stable segments are illustrated schematically.

In contrast to most proteins, which retain native-like structure in acid conditions (41), the fusogenic fragment of HA adopts an alternate conformation in acid pH (Fig. 2b) (63). The low-pH structure of the fusogenic fragment could be more relevant for prediction of cleavages occurring in an acidic antigen-processing compartment. A composite B-factor profile was produced by substituting B-factors from the structure of the fusogenic fragment in place of corresponding B-factors from the structure of the uncleaved precursor. As a result, the correlation of epitope scores with B-factors increased at positive offsets, but the anticorrelation decreased at negative offsets (Fig. 4a). Moreover, the correlations (or anticorrelations) using the composite B-factor profile did not exhibit a distinct maximum over the range sampled. Thus, the inclusion of B-factors from the fusogenic fragment did not strengthen the argument for a specific relationship between epitope dominance and adjacent flexibility.

Using B-factors from the uncleaved HA precursor, the epitope scores from H3-infected mice achieved values of rmax that indicate both correlation and anticorrelation, depending on the offset (Fig. 4a, lower panel). The rmax of 0.34 (P = 0.0007) at offset +16, suggests that epitopes tend to be located 16 residues N terminal from flexible, protease-sensitive sites. The rmax of −0.26 (P = 0.0123) at offset −20 suggests that epitopes tend to be located 20 residues C terminal from segments of low flexibility. This anticorrelation is similar to the anticorrelation observed for humans but at a larger offset from segments of low flexibility. Since dominance correlates well with nearby regions of low flexibility, these results raise the possibility that the positions of epitopes are related to the distribution of stability within the proteolytic fragments generated during antigen processing. As observed for the correlation with epitope scores from humans, the inclusion of B-factors from the fusogenic fragment did not improve the correlation with epitope scores from H3-infected mice (Fig. 4a, lower panel).

In spite of the statistical correlation of epitope scores and B-factors, it is difficult to discern the relationship by inspection of the overlaid profiles (Fig. 3b). Although B-factors represent the most well-documented structural correlate with proteolytic sensitivity, B-factors often do not reveal conformational fluctuations on time scales of seconds to minutes, which could be important during antigen processing (42).

CD4+ epitopes C terminal from stable HA segments.

Amide-group hydrogen-deuterium exchange NMR (HX-NMR) can detect conformational fluctuations of the appropriate size and time scale for prediction of protease-sensitive sites (42, 71); however, HX-NMR data are not available for many proteins, especially large ones such as HA. The COREX algorithm developed by Hilser and Friere calculates a residue stability profile by computing the equilibrium constant for folding, Kf, of all possible segments in the protein (33). The stability (log Kf) profiles resemble the patterns of amide-group hydrogen-exchange protection observed by HX-NMR (31-34, 58). Residue stability profiles were calculated separately for monomers of the HA globular domain, stem, and fusogenic fragment. The residue stability profile for the complete HA monomer calculated at lower precision (due to computational overhead) was similar to the combined profiles for the globular domain and stem, and the profiles calculated for trimers of the stem and fusogenic fragment were similar to those of the monomers (data not shown). The acid-induced structure of the fusogenic fragment may be a better model for processing of the HA stem in the acidic lysosome. Thus, a composite stability profile, including residue stabilities for the neutral-pH globular domain, a portion of the neutral-pH stem, and the entire low-pH fusogenic fragment, also was compared to the epitope profile of HA.

Each peak of epitope dominance overlaps a structurally stable segment of HA (Fig. 3c). Optimum agreement between the number of stable segments and number of epitopes is obtained when HA's low-pH-induced conformational change is taken into account. The stability profile for the stem at neutral pH indicates only one peak in the region of the stem corresponding to the fusogenic fragment (positions 385 to 507), but the dominance profile indicates two peaks in this region. In contrast, the stability profile for the low-pH conformation of the fusogenic fragment indicates two peaks that overlap the epitopes at 443 and 490 (Fig. 3c). Correlation of epitope dominance with residue stability was evaluated for a range of offsets and using the stability profile from the neutral-pH structure or the composite profile that included residue stabilities from the low-pH fusogenic fragment. Epitope dominance in humans and H3-infected mice correlated at a low level with residue stability for the neutral-pH structure (rmax < 0.26) (Fig. 4a, upper and lower panels). The correlation was significantly improved by including residue stabilities from the fusogenic fragment. For dominance in humans, rmax reached 0.47 (P = 0.03) at offset −10 (Fig. 4a, upper panel). For the epitopes in H3-infected mice, the value of rmax reached 0.35 (P = 0.0005) at offset −16 (Fig. 4a, lower panel). The correlations with residue stability at offsets −10 and −16 are similar to the anticorrelations with B-factors at offsets −10 and −20 in humans and mice, respectively. Thus, HA epitopes in both humans and in the H3-infected mice tend to be located on the C-terminal flanks of stable segments, but in humans, the epitopes are shifted closer to the peaks of stability (Fig. 4b). Inclusion of residue stabilities from the fusogenic fragment improves the correlation because the fusogenic fragment has two stable segments, one on each side of the reverse turn formed at low pH, and an epitope lies on the C-terminal flank of each stable segment (Fig. 2b).

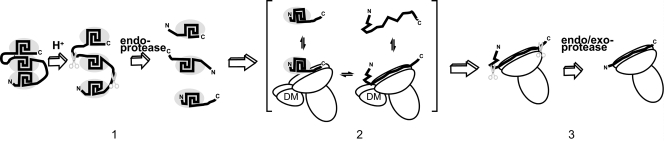

A model for antigen processing and peptide loading provides a framework for understanding CD4+ epitope immunodominance in HA (Fig. 5). In step 1, antigen three-dimensional structure is destabilized by acidification of the antigen-processing compartment and an endoprotease(s) cleaves near the center of the unstable segments, which generates polypeptide fragments having structurally frayed terminal segments. In step 2, a frayed C-terminal segment binds to the MHC protein, the stable segment unfolds, and the fragment adjusts its position in the MHC protein. This step may be aided by multiple DM-catalyzed cycles of fragment releasing and rebinding. DM reduces the selectivity of peptide binding to MHC proteins (48, 51), and therefore it may promote presentation of the most abundant proteolytic fragments. The final complex could be the product of an equilibrium that balances the stability of the MHC-fragment complex with the concentration and conformational stability of the free fragment. In step 3, unbound segments of the fragment are proteolytically trimmed and the completed MHC-peptide complex traffics to the surface of the antigen-presenting cell.

FIG. 5.

General model for HA processing and presentation that accounts for CD4+ epitope dominance on the C-terminal flanks of stable antigen segments. In step 1, an endoprotease(s) cleaves in the unstable loops between stable domains. In step 2, the C-terminal region of a fragment cycles on and off of the MHC protein (catalyzed by DM), allowing the MHC protein to sample more unfolded conformations of the fragment. In step 3, the stably bound fragment is trimmed by proteases and the MHC-peptide complex traffics to the cell surface.

Dominance patterns in nine antigens/allergens.

T-helper epitope dominance patterns were compared to residue stability profiles in a collection of nine antigens/allergens in order to identify general features of the structure-dominance relationship (Table 1 and Fig. 6, 7, and 8). Epitopes of each antigen have been mapped with lymphocytes from humans or rats and with a complete set of overlapping peptides. By inspection of profiles, some epitope dominance peaks occurred on the C-terminal flanks of stable segments; however, other dominance peaks occurred on the N-terminal flanks. Not surprisingly, the correlation of dominance and stability was low for all offsets (rmax < 0.22). Thus, it is necessary to isolate antigen segments in order to assess the individual spatial relationships of peaks of stability and dominance.

TABLE 1.

Frequency of CD4+ epitope dominance peaks and structurally stable segments

| Name | Source | Size (no. of amino acid residues) | No. of stable segments | No. of dominance peaks | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | Influenza virus A | 504 | 10 | 7 | 22-24 |

| Nonstructural 3 | HCV | 461 | 8 | 11 | 25 |

| Ag85A | M. tuberculosis | 296 | 5 | 6 | 44 |

| Ag85B | M. bovis | 285 | 6 | 7 | 57 |

| Hsp65 | M. tuberculosis | 539 | 11 | 16 | 47 |

| Mpb70 | M. tuberculosis | 163 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Bet v 1 | Birch tree | 159 | 3 | 6 | 18 |

| Phl p 1 | Timothy grass | 240 | 6 | 8 | 59 |

| Ves v 5 | Wasp venom | 204 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

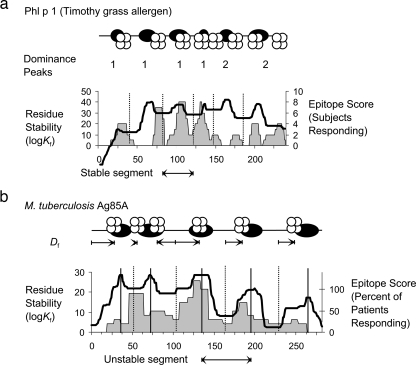

FIG. 6.

Illustrations of CD4+ epitope dominance mapped onto an antigen's stable and unstable segments. (a) Schematic diagram and graph illustrating the frequency of epitope-dominance peaks in stable segments of allergen Phl p 1. In the schematic diagram, the approximate positions of peaks of stability (dark ovals) and epitope score (MHC proteins stylized with four circles) are illustrated. The number of peaks of the epitope score for each stable segment is indicated below the diagram. For the purposes of statistics, stable segments are defined as spanning between stability minima (indicated as broken vertical lines in the graph). (b) Schematic diagram and graph illustrating the locations of epitope dominance within unstable segments of M. tuberculosis Ag85A. The schematic diagram is as in panel a, except the arrows indicate distances (Df) from the stability minimum to peaks of epitope scores within the same unstable segment. Locations of stability minima (broken vertical lines) and stability maxima (solid vertical lines) are illustrated.

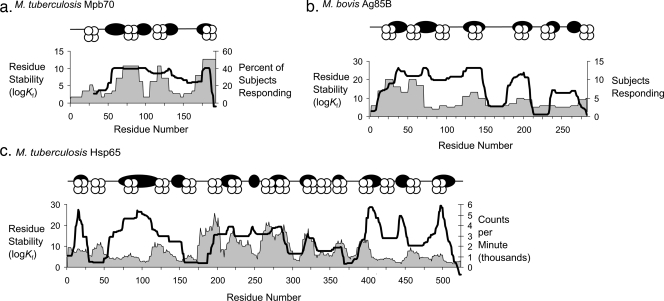

FIG. 7.

CD4+ epitope dominance mapped onto stable and unstable segments in three mycobacterial antigens. In panels a to c, schematic diagrams indicate the approximate positions of peaks of stability (dark ovals) and epitope scores (MHC proteins stylized with four circles) and graphs indicate residue stability (line graphs) and the frequency of epitopes (area graphs).

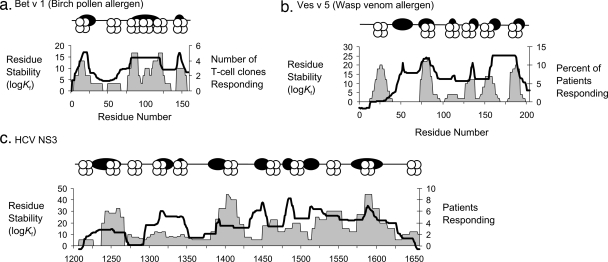

FIG. 8.

CD4+ epitope dominance mapped onto stable and unstable segments in two allergens and one viral antigen. In panels a to c, schematic diagrams indicate the approximate positions of peaks of stability (dark ovals) and epitope scores (MHC proteins stylized with four circles) and graphs indicate residue stability (line graphs) and the frequency of epitopes (area graphs).

The antigens/allergens were divided into stable segments with edges defined by minima in the residue stability profiles (average segment size, 48 ± 18 residues), and the positions of dominance peaks were assigned to stable segments, as illustrated for the Timothy grass allergen, Phl p 1 (Fig. 6a). For the nine antigens/allergens, the majority of the stable segments had a single dominance peak (68%) and a minority had two dominance peaks (20%). Only a small fraction of the stable segments lacked any dominance peak (7%) or had more than two dominance peaks (3%). The finding that the majority of the stable segments have one dominance peak is consistent with our earlier conclusion that there tends to be a one-to-one relationship between immunogenic sequences and disordered sites in antigens/allergens (15).

In order to study the spatial distribution of epitope dominance relative to putative antigen-processing sites, the unstable segments (spanning between stability maxima) were aligned according to their stability minima. For each dominance peak, a flanking distance (Df) was measured as the distance in amino acid residues from the dominance peak to the stability minimum. For example, M. tuberculosis Ag85a has one dominance peak on the left side of the stability minimum (Df, <0) and five dominance peaks on the right side of the stability minimum (Df, >0) (Fig. 6b). For the 71 dominance peaks representing nine antigens, the distribution of dominance peaks between the left and right sides of the stability minimum is essentially even (34 peaks and 36 peaks, respectively). Thus, the tendency for HA epitopes to occur on the C-terminal flanks of stable segments does not reflect a general feature of the antigen-presentation machinery.

The basis for the tendency of HA epitopes to occur on the C-terminal flanks of stable segments could be related to the effect of the influenza virus M2 protein on endosomal and trans-Golgi vesicle acidification and sorting. The M2 protein is an acid-activated proton channel that selectively inhibits acidification of a subset of transport vesicles and partially blocks the delivery and maturation of lysosomal enzymes (29, 30). The M2 protein does not affect lysosomal pH, as indicated by normal morphology of the lysosomes and normal degradation of epidermal growth factor. Thus, it is possible that M2 alters the composition of the antigen-processing machinery in such a way that it introduces a bias toward loading of the C-terminal flanks of stable segments. The processing compartment could be deficient in a lysosomal protease(s) that is normally involved in degradation of the C-terminal flanks. Alternatively, the activity of DM could be affected. The existence of an HA-like pattern in other influenza virus proteins would support the M2-based explanation for a bias in presenting C-terminal flanks. Unfortunately, there are few data to consult. In the study by Woodland and coworkers in mice, aside from HA, only the acidic polymerase (PA) and nucleoprotein (NP) elicited significant T-cell responses (12), and there are no high-resolution structures available for either protein. Amino acid sequence conservation serves as a reasonably good surrogate for structural stability when analyzing the relationship to CD4+ epitope immunodominance (15). When amino acid sequence variation in PA and NP was evaluated in terms of sequence entropy (a surrogate for flexibility), significant correlations with epitope dominance were found at positive offsets. For PA, the rmax of 0.32 occurred at offset +14, and for NP, the rmax of 0.19 occurred at offset +4 (data not shown). Thus, influenza virus could be using M2 protein to focus the CD4+ responses onto the C-terminal flanks of its protein fragments.

Impact of HA variation in the context of structure-based CD4+ epitope dominance.

Results presented here and in previous studies indicate that mechanisms of antigen processing disfavor presentation of epitopes in the middle of flexible antigen segments and favor presentation of epitopes in more stable antigen segments. It is likely that these mechanisms evolved in order to focus CD4+ T-cell immunity on antigen sequences that must be conserved to maintain protein structure and function. The advantage to the host is derived from the cost of immune escape, which is paid by the pathogen in reduced pathogen fitness (3, 5, 66). By extension of that argument, one might expect the processing and presentation machinery to target the most conserved, most stable segments for presentation, for example, by demanding high resistance to proteolysis. However, it is possible that such mechanisms would be too stringent in their requirements for stability, resulting in the presentation of too few epitopes—strong epitope dominance. Strong dominance probably is disadvantageous for the host because immune protection can be defeated by only a few mutations in the dominant epitopes.

The long-standing battle of influenza virus with vertebrate immune systems probably involves strategies to shape the CD4+ response. HA is the target for neutralizing antibodies, and it is a major antigen for both the murine and human CD4+ T-cell responses to influenza virus (74). Antigenic variation in HA arises by two mechanisms that render immunity ineffective against influenza: antigenic drift and antigenic shift (75). In antigenic drift, single amino acid changes accumulate in antibody epitopes of the prevailing viral subtype. In antigenic shift, the reassortment of genes from different viral subtypes produces a virus with more extensive changes in sequence and structure. As discussed below, CD4+ epitope dominance could mitigate or intensify losses in immune protection caused by antigenic drift, but dominance almost certainly intensifies the loss of protection caused by antigenic shift.

Antigenic drift is not expected to alter the CD4+ epitope dominance pattern because the small number of amino acid substitutions would have only minor effects on three-dimensional structure. Thus, the impact of antigenic drift on the recall of CD4+ T-cell responses depends on whether dominance is focused on conserved or divergent sequences. For example, epitopes in humans that are clustered near residue 443 are conserved, and thus responses to these epitopes are likely to be recalled by a new infection. In contrast, epitopes near residue 215 are poorly conserved, and thus dominant responses for that region of HA are less likely to be recalled in a new infection. Since particular CD4+ responses can reduce or exacerbate disease (7, 26, 35), HA is under selective pressure to evade the response to some epitopes more than others, and the dominance pattern could benefit the host or the virus. Mechanisms for epitope-specific CD4+ responses to influence viral clearance are not well understood, but epitope-specific CD8+ responses provide examples that could apply to CD4+ responses. On the one hand, the host benefits from more durable immunity if the dominant epitope is conserved for viral replicative fitness, such as has been observed for CD8+ T-cell epitopes in HIV (3, 5). On the other hand, the virus benefits if the immune response is somehow beneficial to the virus. For example, the CD8+ response to “nonprotective” T-cell epitopes can delay clearance of influenza virus (13).

When an influenza virus having a new HA subtype emerges, the allocation of CD4+ epitope dominance could determine whether the individual realizes any protection from exposure to the previously circulating viral subtype. Residue stability profiles for HA molecules of subtypes H1, H3, H5, and H9 illustrate striking differences in subdomain E and the N-terminal portion of RB (Fig. 3d), which correspond to the poorly conserved dominant regions at residues 130 and 172 (Fig. 1). Shifts of dominance in these regions could prevent the recall of CD4+ T-cell help for B cells specific for neutralizing antibody epitopes, which are most frequently observed in the same region of the protein (63, 74). Likewise, a weak recall of CD4+ T-cell help would reduce the response of CD8+ T cells that depend on CD4+ help (37). Further study of the relationship between HA structure and T-cell immunodominance is likely to reveal new insights on immunity to influenza virus and the feasibility of heterosubtypic immunization.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants R21-AI42702 and R01-AI42350 from the National Institutes of Health.

I thank the New Orleans Protein Folding Intergroup; James Robinson, Robert Garry, and Colin Watts for helpful discussions; and David Woodland, Jay Berzofsky, and Eli Sercarz for critical reviews of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adorini, L., E. Appella, G. Doria, and Z. A. Nagy. 1988. Mechanisms influencing the immunodominance of T cell determinants. J. Exp. Med. 1682091-2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Attiyah, R., F. A. Shaban, H. G. Wiker, F. Oftung, and A. S. Mustafa. 2003. Synthetic peptides identify promiscuous human Th1 cell epitopes of the secreted mycobacterial antigen MPB70. Infect. Immun. 711953-1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen, T. M., M. Altfeld, S. C. Geer, E. T. Kalife, C. Moore, K. M. O'Sullivan, I. Desouza, M. E. Feeney, R. L. Eldridge, E. L. Maier, D. E. Kaufmann, M. P. Lahaie, L. Reyor, G. Tanzi, M. N. Johnston, C. Brander, R. Draenert, J. K. Rockstroh, H. Jessen, E. S. Rosenberg, S. A. Mallal, and B. D. Walker. 2005. Selective escape from CD8+ T-cell responses represents a major driving force of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) sequence diversity and reveals constraints on HIV-1 evolution. J. Virol. 7913239-13249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antoniou, A. N., S. L. Blackwood, D. Mazzeo, and C. Watts. 2000. Control of antigen presentation by a single protease cleavage site. Immunity 12391-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asquith, B., and A. R. McLean. 2007. In vivo CD8+ T cell control of immunodeficiency virus infection in humans and macaques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1046365-6370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohle, B., B. Zwolfer, G. F. Fischer, U. Seppala, T. Kinaciyan, C. Bolwig, M. D. Spangfort, and C. Ebner. 2005. Characterization of the human T cell response to antigen 5 from Vespula vulgaris (Ves v 5). Clin. Exp. Allergy 35367-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, D. M., E. Roman, and S. L. Swain. 2004. CD4 T cell responses to influenza infection. Semin. Immunol. 16171-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmicle, S., G. Dai, N. K. Steede, and S. J. Landry. 2002. Proteolytic sensitivity and helper T-cell epitope immunodominance associated with the mobile loop in Hsp10s. J. Biol. Chem. 277155-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmicle, S., N. K. Steede, and S. J. Landry. 2007. Antigen three-dimensional structure guides the processing and presentation of helper T-cell epitopes. Mol. Immunol. 441159-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chenna, R., H. Sugawara, T. Koike, R. Lopez, T. J. Gibson, D. G. Higgins, and J. D. Thompson. 2003. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 313497-3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciurea, A., L. Hunziker, M. M. Martinic, A. Oxenius, H. Hengartner, and R. M. Zinkernagel. 2001. CD4+ T-cell-epitope escape mutant virus selected in vivo. Nat. Med. 7795-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crowe, S. R., S. C. Miller, D. M. Brown, P. S. Adams, R. W. Dutton, A. G. Harmsen, F. E. Lund, T. D. Randall, S. L. Swain, and D. L. Woodland. 2006. Uneven distribution of MHC class II epitopes within the influenza virus. Vaccine 24457-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crowe, S. R., S. C. Miller, and D. L. Woodland. 2006. Identification of protective and non-protective T cell epitopes in influenza. Vaccine 24452-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dai, G., S. Carmicle, N. K. Steede, and S. J. Landry. 2002. Structural basis for helper T-cell and antibody epitope immunodominance in bacteriophage T4 Hsp10: role of disordered loops. J. Biol. Chem. 277161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai, G., N. K. Steede, and S. J. Landry. 2001. Allocation of helper T-cell epitope immunodominance according to three-dimensional structure in the human immunodeficiency virus type I envelope glycoprotein gp120. J. Biol. Chem. 27641913-41920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Day, C. L., G. M. Lauer, G. K. Robbins, B. McGovern, A. G. Wurcel, R. T. Gandhi, R. T. Chung, and B. D. Walker. 2002. Broad specificity of virus-specific CD4+ T-helper-cell responses in resolved hepatitis C virus infection. J. Virol. 7612584-12595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diethelm-Okita, B. M., D. K. Okita, L. Banaszak, and B. M. Conti-Fine. 2000. Universal epitopes for human CD4+ cells on tetanus and diphtheria toxins. J. Infect. Dis. 1811001-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dormann, D., C. Ebner, E. R. Jarman, E. Montermann, D. Kraft, and A. B. Reske Kunz. 1998. Responses of human birch pollen allergen-reactive T cells to chemically modified allergens (allergoids). Clin. Exp. Allergy 281374-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fontana, A., G. Fassina, C. Vita, D. Dalzoppo, M. Zamai, and M. Zambonin. 1986. Correlation between sites of limited proteolysis and segmental mobility in thermolysin. Biochemistry 251847-1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedl-Hajek, R., M. D. Spangfort, C. Schou, H. Breiteneder, H. Yssel, and R. J. Joost van Neerven. 1999. Identification of a highly promiscuous and an HLA allele-specific T-cell epitope in the birch major allergen Bet v 1: HLA restriction, epitope mapping and TCR sequence comparisons. Clin. Exp. Allergy 29478-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gammon, G., N. Shastri, J. Cogswell, S. Wilbur, S. Sadegh-Nasseri, U. Krzych, A. Miller, and E. Sercarz. 1987. The choice of T-cell epitopes utilized on a protein antigen depends on multiple factors distant from, as well as at the determinant site. Immunol. Rev. 9853-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelder, C., M. Davenport, M. Barnardo, T. Bourne, J. Lamb, B. Askonas, A. Hill, and K. Welsh. 1998. Six unrelated HLA-DR-matched adults recognize identical CD4(+) T cell epitopes from influenza A haemagglutinin that are not simply peptides with high HLA-DR binding affinities. Int. Immunol. 10211-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gelder, C. M., J. R. Lamb, and B. A. Askonas. 1996. Human CD4+ T-cell recognition of influenza A virus hemagglutinin after subunit vaccination. J. Virol. 704787-4790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gelder, C. M., K. I. Welsh, A. Faith, J. R. Lamb, and B. A. Askonas. 1995. Human CD4+ T-cell repertoire of responses to influenza A virus hemagglutinin after recent natural infection. J. Virol. 697497-7506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerlach, J. T., A. Ulsenheimer, N. H. Gruner, M.-C. Jung, W. Schraut, C.-A. Schirren, M. Heeg, S. Scholz, K. Witter, R. Zahn, A. Vogler, R. Zachoval, G. R. Pape, and H. M. Diepolder. 2005. Minimal T-cell-stimulatory sequences and spectrum of HLA restriction of immunodominant CD4+ T-cell epitopes within hepatitis C virus NS3 and NS4 proteins. J. Virol. 7912425-12433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graham, M. B., V. L. Braciale, and T. J. Braciale. 1994. Influenza virus-specific CD4+ T helper type 2 T lymphocytes do not promote recovery from experimental virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 1801273-1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall, T. A. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 4195-98. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammer, J., P. Valsasnini, K. Tolba, D. Bolin, J. Higelin, B. Takacs, and F. Sinigaglia. 1993. Promiscuous and allele-specific anchors in HLA-DR-binding peptides. Cell 74197-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henkel, J. R., G. A. Gibson, P. A. Poland, M. A. Ellis, R. P. Hughey, and O. A. Weisz. 2000. Influenza M2 proton channel activity selectively inhibits trans-Golgi network release of apical membrane and secreted proteins in polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J. Cell Biol. 148495-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henkel, J. R., J. L. Popovich, G. A. Gibson, S. C. Watkins, and O. A. Weisz. 1999. Selective perturbation of early endosome and/or trans-Golgi network pH but not lysosome pH by dose-dependent expression of influenza M2 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2749854-9860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hilser, V. J., D. Dowdy, T. G. Oas, and E. Freire. 1998. The structural distribution of cooperative interactions in proteins: analysis of the native state ensemble. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 959903-9908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hilser, V. J., and E. Freire. 1997. Predicting the equilibrium protein folding pathway: structure-based analysis of staphylococcal nuclease. Proteins 27171-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hilser, V. J., and E. Freire. 1996. Structure-based calculation of the equilibrium folding pathway of proteins. Correlation with hydrogen exchange protection factors. J. Mol. Biol. 262756-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hilser, V. J., B. D. Townsend, and E. Freire. 1997. Structure-based statistical thermodynamic analysis of T4 lysozyme mutants: structural mapping of cooperative interactions. Biophys. Chem. 6469-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hogan, R. J., W. Zhong, E. J. Usherwood, T. Cookenham, A. D. Roberts, and D. L. Woodland. 2001. Protection from respiratory virus infections can be mediated by antigen-specific CD4(+) T cells that persist in the lungs. J. Exp. Med. 193981-986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hubbard, S. J., S. F. Campbell, and J. M. Thornton. 1991. Molecular recognition. Conformational analysis of limited proteolytic sites and serine proteinase protein inhibitors. J. Mol. Biol. 220507-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janssen, E. M., E. E. Lemmens, T. Wolfe, U. Christen, M. G. von Herrath, and S. P. Schoenberger. 2003. CD4+ T cells are required for secondary expansion and memory in CD8+ T lymphocytes. Nature 421852-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jardetzky, T. S., J. H. Brown, J. C. Gorga, L. J. Stern, R. G. Urban, J. L. Strominger, and D. C. Wiley. 1996. Crystallographic analysis of endogenous peptides associated with HLA-DR1 suggests a common, polyproline II-like conformation for bound peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93734-738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaufmann, D. E., P. M. Bailey, J. Sidney, B. Wagner, P. J. Norris, M. N. Johnston, L. A. Cosimi, M. M. Addo, M. Lichterfeld, M. Altfeld, N. Frahm, C. Brander, A. Sette, B. D. Walker, and E. S. Rosenberg. 2004. Comprehensive analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific CD4 responses reveals marked immunodominance of gag and nef and the presence of broadly recognized peptides. J. Virol. 784463-4477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim, J., A. Sette, S. Rodda, S. Southwood, P. A. Sieling, V. Mehra, J. D. Ohmen, J. Oliveros, E. Appella, Y. Higashimoto, T. H. Rea, B. R. Bloom, and R. L. Modlin. 1997. Determinants of T cell reactivity to the Mycobacterium leprae GroES homologue. J. Immunol. 159335-343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuwajima, K. 1989. The molten globule state as a clue for understanding the folding and cooperativity of globular-protein structure. Proteins 687-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landry, S. J. 1997. Local protein instability predictive of helper T-cell epitopes. Immunol. Today 18527-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Latek, R. R., and E. R. Unanue. 1999. Mechanisms and consequences of peptide selection by the I-Ak class II molecule. Immunol. Rev. 172209-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Launois, P., R. DeLeys, M. N. Niang, A. Drowart, M. Andrien, P. Dierckx, J.-L. Cartel, J.-L. Sarthou, J.-P. Van Vooren, and K. Huygen. 1994. T-cell-epitope mapping of the major secreted mycobacterial antigen Ag85A in tuberculosis and leprosy. Infect. Immun. 623679-3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li, P., M. A. Haque, and J. S. Blum. 2002. Role of disulfide bonds in regulating antigen processing and epitope selection. J. Immunol. 1692444-2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma, C., P. E. Whiteley, P. M. Cameron, D. C. Freed, A. Pressey, S. L. Chen, B. Garni-Wagner, C. Fang, D. M. Zaller, L. S. Wicker, and J. S. Blum. 1999. Role of APC in the selection of immunodominant T cell epitopes. J. Immunol. 1636413-6423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moudgil, K. D., T. T. Chang, H. Eradat, A. M. Chen, R. S. Gupta, E. Brahn, and E. E. Sercarz. 1997. Diversification of T cell responses to carboxy-terminal determinants within the 65-kD heat-shock protein is involved in regulation of autoimmune arthritis. J. Exp. Med. 1851307-1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nanda, N. K., and E. K. Bikoff. 2005. DM peptide-editing function leads to immunodominance in CD4 T cell responses in vivo. J. Immunol. 1756473-6480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Novotny, J., and R. E. Bruccoleri. 1987. Correlation among sites of limited proteolysis, enzyme accessibility and segmental mobility. FEBS Lett. 211185-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panina-Bordignon, P., A. Tan, A. Termijtelen, S. Demotz, G. Corradin, and A. Lanzavecchia. 1989. Universally immunogenic T cell epitopes: promiscuous binding to human MHC class II and promiscuous recognition by T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 192237-2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pashine, A., R. Busch, M. P. Belmares, J. N. Munning, R. C. Doebele, M. Buckingham, G. P. Nolan, and E. D. Mellins. 2003. Interaction of HLA-DR with an acidic face of HLA-DM disrupts sequence-dependent interactions with peptides. Immunity 19183-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phelps, R. G., V. L. Jones, M. Coughlan, A. N. Turner, and A. J. Rees. 1998. Presentation of the Goodpasture autoantigen to CD4 T cells is influenced more by processing constraints than by HLA class II peptide binding preferences. J. Biol. Chem. 27311440-11447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Puig, M., K. Mihalik, J. C. Tilton, O. Williams, M. Merchlinsky, M. Connors, S. M. Feinstone, and M. E. Major. 2006. CD4+ immune escape and subsequent T-cell failure following chimpanzee immunization against hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 44736-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raju, R., D. Navaneetham, D. Okita, B. Diethelm-Okita, D. McCormick, and B. M. Conti-Fine. 1995. Epitopes for human CD4+ cells on diphtheria toxin: structural features of sequence segments forming epitopes recognized by most subjects. Eur. J. Immunol. 253207-3214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Richards, K. A., F. A. Chaves, F. R. Krafcik, D. J. Topham, C. A. Lazarski, and A. J. Sant. 2007. Direct ex vivo analyses of HLA-DR1 transgenic mice reveal an exceptionally broad pattern of immunodominance in the primary HLA-DR1-restricted CD4 T-cell response to influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 817608-7619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ringe, D., and G. A. Petsko. 1986. Study of protein dynamics by X-ray diffraction. Methods Enzymol. 131389-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roche, P. W., P. W. Peake, H. Billman-Jacobe, T. Doran, and W. J. Britton. 1994. T-cell determinants and antibody binding sites on the major mycobacterial secretory protein MPB59 of Mycobacterium bovis. Infect. Immun. 625319-5326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sadqi, M., S. Casares, M. A. Abril, O. Lopez Mayorga, F. Conejero Lara, and E. Freire. 1999. The native state conformational ensemble of the SH3 domain from alpha-spectrin. Biochemistry 388899-8906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schenk, S., H. Breiteneder, M. Susani, N. Najafian, S. Laffer, M. Duchene, R. Valenta, G. Fischer, O. Scheiner, D. Kraft, and C. Ebner. 1996. T cell epitopes of Phl p 1, major pollen allergen of timothy grass (Phleum pratense). Crossreactivity with group I allergens of different grasses. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 409141-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schulze zur Wiesch, J., G. M. Lauer, C. L. Day, A. Y. Kim, K. Ouchi, J. E. Duncan, A. G. Wurcel, J. Timm, A. M. Jones, B. Mothe, T. M. Allen, B. McGovern, L. Lewis-Ximenez, J. Sidney, A. Sette, R. T. Chung, and B. D. Walker. 2005. Broad repertoire of the CD4+ Th cell response in spontaneously controlled hepatitis C virus infection includes dominant and highly promiscuous epitopes. J. Immunol. 1753603-3613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schwede, T., J. Kopp, N. Guex, and M. C. Peitsch. 2003. SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 313381-3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sinnathamby, G., M. Maric, P. Cresswell, and L. C. Eisenlohr. 2004. Differential requirements for endosomal reduction in the presentation of two H2-E (d)-restricted epitopes from influenza hemagglutinin. J. Immunol. 1726607-6614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Skehel, J. J., and D. C. Wiley. 2000. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69531-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith, J. M., R. R. Amara, L. S. Wyatt, D. L. Ellenberger, B. Li, J. G. Herndon, M. Patel, S. Sharma, L. Chennareddi, S. Butera, J. McNicholl, H. M. McClure, B. Moss, and H. L. Robinson. 2005. Studies in macaques on cross-clade T cell responses elicited by a DNA/MVA AIDS vaccine, better conservation of CD8 than CD4 T cell responses. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 21140-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.So, T., H. Ito, T. Koga, S. Watanabe, T. Ueda, and T. Imoto. 1997. Depression of T-cell epitope generation by stabilizing hen lysozyme. J. Biol. Chem. 27232136-32140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Soderholm, J., G. Ahlen, A. Kaul, L. Frelin, M. Alheim, C. Barnfield, P. Liljestrom, O. Weiland, D. R. Milich, R. Bartenschlager, and M. Sallberg. 2006. Relation between viral fitness and immune escape within the hepatitis C virus protease. Gut 55266-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Streicher, H. Z., I. J. Berkower, M. Busch, F. R. Gurd, and J. A. Berzofsky. 1984. Antigen conformation determines processing requirements for T-cell activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 816831-6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vanegas, R. A., N. E. Street, and T. M. Joys. 1997. In a vaccine model, selected substitution of a highly stimulatory T cell epitope of hen's egg lysozyme into a Salmonella flagellin does not result in a homologous, specific, cellular immune response and may alter the way in which the total antigen is processed. Vaccine 15321-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang, H., T. Bian, S. J. Merrill, and D. D. Eckels. 2002. Sequence variation in the gene encoding the nonstructural 3 protein of hepatitis C virus: evidence for immune selection. J. Mol. Evol. 54465-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang, H., and D. D. Eckels. 1999. Mutations in immunodominant T cell epitopes derived from the nonstructural 3 protein of hepatitis C virus have the potential for generating escape variants that may have important consequences for T cell recognition. J. Immunol. 1624177-4183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang, L., R. X. Chen, and N. R. Kallenbach. 1998. Proteolysis as a probe of thermal unfolding of cytochrome c. Proteins 30435-441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Watts, C. 2004. The exogenous pathway for antigen presentation on major histocompatibility complex class II and CD1 molecules. Nat. Immunol. 5685-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Watts, C., and A. Lanzavecchia. 1993. Suppressive effect of antibody on processing of T cell epitopes. J. Exp. Med. 1781459-1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wiley, D. C., and J. J. Skehel. 1987. The structure and function of the hemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 56365-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wright, P. F., and R. G. Webster. 2001. Orthomyxoviruses, p. 1533-1579. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed., vol. 1. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yewdell, J. T., and J. R. Bennink. 1999. Immunodominance in major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted T lymphocyte responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1751-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]