Abstract

Study Objectives:

Total sleep time (TST), sleep efficiency (SE), and wake after sleep onset (WASO) as assessed by actigraphy gathered in 3 different modes were compared to polysomnography (PSG) measurements. Each mode was compared to PSG to determine which was more accurate. Associations of the difference in TST measurement with demographics and sleep characteristics were examined.

Design:

Observational study.

Setting:

Community-based.

Participants:

Sixty-eight women (mean age 81.9 years) from the latest visit of the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures who were concurrently measured with PSG and actigraphy.

Interventions:

N/A.

Measurements and Results:

In-home 12-channel PSG was gathered along with actigraphy data in 3 modes: proportional integration mode (PIM), time above threshold (TAT) and zero crossings mode (ZCM). The PIM mode corresponded better to PSG, with a mean overestimation of TST of 17.9 min. For the PIM mode, the estimation of TST and SE by PSG and actigraphy significantly differed (P < 0.01), while the estimation of WASO was similar (P = 0.27). The intraclass correlation between the 2 procedures was moderate to high (PIM mode: TST 0.76; SE 0.61; WASO 0.58). On average, the PIM mode underestimated TST by 68 min for those who slept ≤5 hr, overestimated TST by 31 min for those with SE <70%, and underestimated TST by 24 min for self-reported poor sleepers (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

Sleep parameters from actigraphy corresponded reasonably well to PSG in this population, with the PIM mode of actigraphy correlating highest. Those with poor sleep quality had the largest measurement error between the 2 procedures.

Citation:

Blackwell T; Redline S; Ancoli-Israel S; Schneider JL; Surovec S; Johnson NL; Cauley JA; Stone KL; for the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Comparison of sleep parameters from actigraphy and polysomnography in older women: the sof study. SLEEP 2008;31(2):283–291.

Keywords: Actigraphy, polysomnography, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, validation

POLYSOMNOGRAPHY (PSG) IS THE “GOLD STANDARD” FOR SLEEP ASSESSMENT. STUDY PARTICIPANTS COME TO A SLEEP LABORATORY WHERE MULTIPLE channels of data are collected. Data typically gathered from PSG include measures of total sleep time (TST); sleep efficiency (SE); wake after sleep onset (WASO); sleep architecture; and identification of pathological events, including apneas, hypopneas, and periodic leg movements. Over the last decade advances in PSG equipment have made the collection of these data in the home setting possible, which can help to put participants at ease and allow for the collection of data in their usual sleeping environment. Even with these advancements, the gathering of polysomnographic data can be invasive, costly, and disruptive to sleep.

Actigraphy has been used for over 25 years to assess sleep/wake behavior.1 Actigraphy utilizes a single channel that collects data on movement, which is used to infer time spent asleep and wake. The benefits of utilizing actigraphy in sleep research are many: it is less cumbersome than PSG, less expensive, and the actigraph can be worn for extended periods of time. These properties make it potentially useful for gathering objective sleep data in large population studies in which issues of participant burden are important, and when measurements are needed to represent chronic behaviors and demonstrate good reliability. Actigraphy performed over multiple nights may provide more reliable data on sleep measures than PSG, which is more typically performed for one or two nights. Actigraphy data, usually averaged over several nights, typically includes TST, SE, WASO, information about daytime inactivity, and circadian rhythm information.

Most of the prior literature that has addressed the validity of actigraphy has focused on specific populations.2–17 High correlations for TST (over 90%) have been found among healthy volunteers.2–7 Some studies have included heterogeneous populations of controls and patients with sleep disorders.8,9 Other studies have examined this association among patients with sleep disorders,12 some specific to those with sleep disordered breathing13 and some to insomniacs.10,11 The accuracy of actigraphy has also been validated among nursing home residents.15

A number of prior studies comparing actigraphy to PSG have been performed, although the actigraph systems have varied. As noted by Ancoli-Israel and colleagues, different actigraphic devices may have different measurement of activity level and sleep-wake scoring algorithms, which can make direct comparison of devices difficult.1 The sleep outcomes derived after computer processing are more meaningful for comparison between devices, but it may be necessary to validate each actigraphic device and scoring algorithm within specific populations. This is particularly true when patterns of activity and rest may differ and thus influence the overall accuracy of specific approaches for inferring sleep. Population differences in age, gender, and underlying diseases may influence the overall accuracy of specific approaches for measuring sleep. For example, although proportional integration mode has been identified as the mode yielding the highest level of agreement for sleep duration measured by PSG in several studies of adults,1 a recent study showed that among adolescents, the highest level of agreement was obtained using the time above threshold mode.17 Since sleep quality and duration are important predictors of health outcomes, with growing recognition of the importance of sleep in geriatric populations,18 there is a need to identify the optimal approaches for measuring sleep parameters in older populations. In particular, there has been little research of sleep measurement in older women, in whom age-related changes in sleep patterns may influence the reliability of specific actigraphic approaches for quantifying sleep duration and quality. Poorer reliability may be due to additional time spent inactive, which may be interpreted as “sleep” by the actigraph, or to frequent nocturnal arousals, which may cause sleep to be underestimated. To our knowledge, there have been no studies that have examined the validity of actigraphy and the sleep scoring algorithms used on actigraphic data to assess sleep and wake in a population of elderly community-dwelling women.

The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) provides a unique opportunity to investigate our primary objectives: (1) to determine whether TST as assessed with the actigraph model SleepWatch-O (Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc., Ardsley, NY) is comparable to the assessment of TST using PSG in community-dwelling elderly women; (2) to determine which of three different modes of activity measurement from this model of actigraph is optimal for measurement of TST; (3) to explore if the differences found between the assessment of TST by PSG and actigraphy are driven by underlying factors, such as age, frailty, or a sleep disorder. Our secondary objectives are to examine the agreement of measures of sleep fragmentation, as defined by WASO and SE, scored by PSG and this model of actigraph.

METHODS

Participants

The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures is a longitudinal study designed to examine risk factors for osteoporotic fractures. Community-dwelling women aged 65 years or older were recruited from population-based listings in four US areas: Baltimore, Maryland; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Portland, Oregon; and the Monongahela Valley, Pennsylvania. At the baseline visit women were excluded if they were unable to walk without help or had previous bilateral hip replacements. The SOF study enrolled 9,704 Caucasian women from September 1986 to October 1988.19 Initially African American women were excluded from the study due to their low incidence of hip fractures, but from February 1997 to February 1998, 662 African American women were recruited.20

The focus of this analysis is the most recent visit, which took place between January 2002 and April 2004. There were a total of 4,727 participants at this visit: 3,137 (66%) visited a study clinic for performance measures, anthropometry, and a clinic interview, 1,051 (22%) had self-administered questionnaire data only, and 539 (11%) had a limited visit done in their homes. At this visit sleep measures were introduced into the SOF protocol. Actigraphy data were collected on all consenting participants who completed a clinic or home visit (N=3,127). In-home PSG data was collected in a convenience sample of 461 women at 2 of the clinics. Questionnaire information regarding sleep habits was also gathered. The actigraph recording typically started the day of the clinic exam. The study protocol did not specifically require the participants wear the actigraph while the PSG recording was performed, but rather that the PSG was performed within one month of the clinic visit exam. The PSG recording was often done later due to scheduling issues or availability of equipment. Therefore, not all 461 women with a PSG recording had an actigraphic recording done concurrently. This analysis consists of those 68 women who did have PSG and actigraphy recordings done concurrently. The institutional review boards at each clinic site approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Polysomnography

All clinic staff who gathered PSG data were required to go through formal, centralized training and pass a certification test before being allowed to oversee collection of sleep study data. PSG data were collected in the participant's home using the Compumedics Siesta Unit (Abbotsville, AU). Channels monitored included 2 central electroencephalographic leads (C1, C2), bilateral electrooculogram (EOG), chin electromyogram (EMG), thoracic and abdominal respiratory effort, airflow (by a nasal-oral thermocouple and nasal pressure recording), finger pulse oximetry, electrocardiogram (ECG), body position, and bilateral leg movements (with piezoelectric sensors). After studies were downloaded, they were transferred to the Case Reading Center (Cleveland, OH) for centralized scoring by a trained technician. Sleep stages and arousals in the PSG data were scored by certified scorers using standard criteria.21,22 Sleep was staged in 30-sec scoring epochs. Scorers were blinded to the results of the actigraphy data. The sleep period was defined as the time from reported lights off to morning awakening. Apneas were defined by the absence or near absence of airflow on thermistor for ≥10 sec with an oxygen desaturation of 3% or more. Hypopneas were defined by a decrease in breathing amplitude of ≥30% for ≥10 sec with an oxygen desaturation of 3% or more. The apnea hypopnea index (AHI) was defined as apneas plus hypopneas per hour of sleep time. AHI was considered as both a continuous variable and a categorical variable using the cutpoints >5 and >15. WASO was defined as the minutes awake during the sleep period after sleep onset (the first 2 continuous minutes scored as sleep). Sleep efficiency, defined as the percent of time scored as sleep during the sleep period, was examined as a continuous variable and using the cutpoint <70%.

Actigraphy

The Sleepwatch-O (Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc, Ardsley, NY) was used. This actigraph, which looks like a wristwatch, measures movement using a piezoelectric biomorph-ceramic cantilevered beam, which generates a voltage each time the actigraph is moved. These voltages are gathered continuously and stored in 1-min epochs. The term “mode” is used to refer to the technique with which different measures were obtained. Data were collected in the 3 modes of zero crossings (ZCM), proportional integration mode (PIM), and time above threshold (TAT). In ZCM mode the conditioned transducer signal is compared with a sensitivity threshold of zero. The number of times the signal voltage crosses zero voltage is summed over the epoch. The ZCM mode is a measure of frequency of movement. The PIM mode is a high-resolution measurement of the area under the rectified conditioned transducer signal (area under the curve). The PIM mode is a measure of activity level or vigor of motion. In TAT mode the amount of time in tenths of a second spent above the sensitivity threshold is gathered over the epoch. The TAT mode measures time spent in motion or duty-cycle.23

Actigraphy data were transferred to the San Francisco Coordinating Center (San Francisco, CA) for centralized processing. Centralized training and certification were also required for clinic staff gathering actigraphy data. Action W-2 software was used to score the data.24 Sleep scoring algorithms available in this software were used to determine sleep from wake times. The Cole-Kripke algorithm was used for data collected in the ZCM mode, and the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) scoring algorithm was used for data collected in the PIM and TAT modes.9,25 These algorithms calculate a moving average, which takes into account the activity levels immediately prior to and after the current minute to determine if each timepoint should be coded as sleep or wake. Although the UCSD algorithm is also available for scoring the ZCM mode, a comparison of the data using the UCSD algorithm rather than the Cole-Kripke algorithm showed a very high rate of agreement (95%). Therefore, the default algorithm selected by the software was used in our current analysis. Sleep efficiency and WASO were defined similarly to PSG for comparison.

In SOF, women wore the actigraphs for a minimum of 3 consecutive 24-hour periods. For those 68 women who wore the actigraph concurrent with their PSG recording, the actigraphy files were edited to include only the time period that was assessed by both methods. None of these 68 women removed their actigraphs during this time period.

Sleep Parameters

The primary outcome measure was TST. Secondary outcomes of sleep, reflecting sleep fragmentation (WASO and SE), were also examined. The differences between the TST, WASO, and SE as measured by PSG and each of the 3 modes of actigraphy data collected were presented to show the direction of any bias. Absolute differences were presented to quantify the overall magnitude of differences among measurements. The TST and WASO differences in min were also categorized to examine the distributions as <−90, −90 to −61, −60 to −31, −30 to −16, −15 to 15, 16 to 30, 31 to 60, 61 to 90, >91. Similarly, the SE differences were categorized as < −25, − 25 to −16, −15 to −11, −10 to −6, −5 to 5, 6 to 10, 11 to 15, 16 to 25, and >25.

Other Measurements

All participants completed questionnaire data, which included questions about medical history, self-reported health, and physical activity. The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was used to assess depressive symptoms, with the standard cutoff of ≥6 symptoms used to define depression.26 The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was also completed, with self-reported poor sleep defined as global PSQI >5.27,28

During the home or clinic visits current medication use within the last 2 weeks was assessed by examination of medications, and a computerized medication coding dictionary was used to categorize these medications.29 The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was administered to assess cognitive function, with higher scores on a scale of 0 to 30 representing better cognition.30 Functional status was assessed by collecting information on 6 independent activities of daily living (IADL), which included walking 2 to 3 blocks on level ground, climbing up to 10 steps, walking down 10 steps, preparing meals, doing heavy housework, and shopping for groceries or clothing.31,32 Body weight and height were measured, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of this convenience subset of 68 women were summarized by means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables, and counts and percentages for categorical variables.

The differences between TST, WASO, and SE as assessed by the gold standard PSG measurement and those from actigraphy were examined using paired t-tests. Agreement between the 2 methods of sleep assessment was examined with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), which were computed using a two-way analysis of variance.33 Bland and Altman plots were presented to assess systematic bias in the differences in measurement of TST.34

Scatterplots were studied to assess if there was a potential u-shaped (nonlinear) relationship between the difference in the measurement of TST by PSG and actigraphy (PSG TST- actigraphy TST) and a number of factors which were considered to potentially explain these differences (plots not shown). Because no u-shaped relationships seemed apparent, linear regression models were used to explore these associations. Results were presented as beta coefficients and 95% CI.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Population

Of the 456 women with both actigraphy and polysomnography data, 68 (14.9%) had data from both methods measured concurrently. These 68 women were age 81.9 years old on average, with African Americans making up 16.2% of this analysis subset (Table 1). The mean time spent in bed during the PSG recording was 7.6 ± 1.3 hr. These women had an average TST from PSG of 5.7 hr, mean WASO of 83.7 min, sleep efficiency averaging 75.4%, and a median AHI of 20.0 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Analysis Subset

| Analysis Subset (n=68) | |

|---|---|

| PSG data: | |

| Total sleep time, min, mean ± SD | 342.8 ± 70.2 |

| Sleep efficiency <70%, N (%) | 18 (26.5) |

| Apnea-hypopnea index , mean ± SD | 15.1 ± 14.6 |

| AHI≥5, N(%) | 50 (73.5) |

| AHI≥15, N(%) | 28 (41.2) |

| Characteristics: | |

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 81.9 ± 3.8 |

| Body mass index, k/m2, mean ± SD | 29.1 ± 5.4 |

| African American, N (%) | 11 (16.2) |

| Difficulty with one or more IADL, N (%) | 31 (45.6) |

| Depression (GDS≥ 6), N (%) | 10 (14.7) |

| MMSE (range 0-30), mean ± SD | 28.3 ± 1.5 |

| Take walks for exercise, N (%) | 19 (27.9) |

| Self reported health, N (%) | |

| Poor/very poor | 2 (2.9) |

| Fair | 12 (17.7) |

| Good/very good | 54 (79.4) |

| Medical conditions*, N (%) | 11 (68.8) |

| Currently took medication for sleep, N (%) | 7 (10.3) |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (range 0-21), mean ± SD | 6.6 ± 3.9 |

| Poor sleep (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index>5), N (%) | 36 (52.9) |

Medical conditions included stroke, diabetes, dementia, COPD, osteoarthritis, or cancer.

SD = standard deviation, AHI = Apnea-hypopnea index, IADL = independent activities of daily living, GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale, MMSE = the Mini-Mental State Examination, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 2.

Comparison of Sleep Parameters Calculated by PSG and Actigraphy (N = 68 pairs)

| Mean ± SD | Difference PSG-Actigraphy mean ± SD | Absolute Difference mean ± SD | paired t-test P-value* | ICC (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TST, min | |||||

| PSG: | 342.8 ± 70.2 | ||||

| Actigraphy Mode: | |||||

| PIM | 360.7 ± 81.1 | −17.9 ± 50.1 | 44.2 ± 29.1 | 0.0045 | 0.76(0.64, 0.84) |

| TAT | 375.8 ± 85.6 | −33.0 ± 57.6 | 55.7 ± 35.7 | <0.0001 | 0.66(0.50, 0.77) |

| ZCM | 317.2 ± 107.6 | 25.6 ± 86.0 | 61.2 ± 65.3 | 0.0167 | 0.53(0.33, 0.68) |

| WASO, min | |||||

| PSG: | 83.7 ± 53.3 | ||||

| Actigraphy Mode: | |||||

| PIM | 76.9 ± 55.5 | 6.7 ± 49.9 | 38.8 ± 31.7 | 0.2657 | 0.58(0.40, 0.72) |

| TAT | 62.9 ± 55.6 | 20.7 ± 57.1 | 48.6 ± 36.0 | 0.0036 | 0.41(0.19, 0.57) |

| ZCM | 98.7 ± 74.1 | −15.1 ± 82.0 | 55.1 ± 62.2 | 0.1353 | 0.19(−0.05,0.41) |

| SE, % | |||||

| PSG: | 75.4 ± 12.1 | ||||

| Actigraphy Mode: | |||||

| PIM | 79.2 ± 14.2 | −3.9 ± 11.1 | 9.8 ± 6.5 | 0.0056 | 0.61(0.44, 0.74) |

| TAT | 82.4 ± 14.6 | −7.0 ± 13.0 | 12.4 ± 7.9 | <0.0001 | 0.44(0.23, 0.61) |

| ZCM | 69.5 ± 22.1 | 5.9 ± 20.1 | 13.9 ± 15.6 | 0.0192 | 0.33(0.11, 0.53) |

P-value is from a t-test on the paired data for difference. P-values for paired t-test on absolute difference was also significant.

TST = total sleep time, WASO = wake after sleep onset, SE = sleep efficiency, PSG = polysomnography, PIM = proportional integration mode, TAT = time above threshold, ZCM = zero crossings mode, SD = standard deviation, CI = confidence interval, ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient

Comparison of Total Sleep Time Calculated by Polysomnography and Actigraphy

There was a statistically significant difference between the estimation of TST by the gold standard PSG and all 3 modes of actigraphy (P < 0.02 for paired t-test, Table 2). Higher levels of agreement to PSG were observed for the PIM mode than other actigraphic modes, with an average overestimation of TST of 17.9 min (range −113 to 124) and an absolute difference of 44.2 min on average. The TAT mode also overestimated sleep on average by 33.0 min (range −125 to 146), while the ZCM mode underestimated sleep by an average of 25.6 min (range −113 to 317). While these differences are statistically significant, the intraclass correlation coefficients of the PSG measurement of TST and the data from the 3 modes of actigraphy were moderate to high (0.76 for the PIM mode, 0.66 for the TAT mode, and 0.53 for the ZCM mode). Examination of the distributions showed that while TST from the ZCM mode had more values that matched PSG TST within 15 min (24%), it also had more extreme differences from PSG, with 18% of the values overestimating sleep by over 90 min (Table 3). The PIM mode had fewer extreme differences that the other 2 modes, with only 9% showing a difference of over 90 min, compared to 19% for the TAT mode and 22% for ZCM mode (P < 0.01).

Table 3.

Difference Between PSG and Actigraphy, N (%) in Category

| Actigraphy Overestimated |

Actigraphy Underestimated |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minutes | <−90 | −90 to −61 | −60 to −31 | −30 to −16 | −15 to 15 | 16 to 30 | 31 to 60 | 61 to 90 | >90 |

| TST | |||||||||

| PIM | 4 (6) | 8 (12) | 17 (25) | 13 (19) | 11 (16) | 3 (4) | 5 (7) | 5 (7) | 2 (3) |

| TAT | 11 (16) | 6 (9) | 25 (37) | 7 (10) | 8 (12) | 1 (1) | 5 (7) | 3 (4) | 2 (3) |

| ZCM | 3 (4) | 4 (6) | 6 (9) | 12 (18) | 16 (24) | 4 (6) | 6 (9) | 5 (7) | 12 (18) |

| WASO | |||||||||

| PIM | 2 (3) | 6 (9) | 5 (7) | 7 (10) | 17 (25) | 13 (19) | 8 (12) | 7 (10) | 3 (4) |

| TAT | 3 (4) | 4 (6) | 5 (7) | 1 (1) | 12 (18) | 13 (19) | 16 (24) | 8 (12) | 6 (9) |

| ZCM | 10 (15) | 3 (4) | 6 (9) | 5 (7) | 20 (29) | 10 (15) | 6 (9) | 3 (4) | 5 (7) |

| Percent | >25 | −25 to −16 | −15 to −11 | −10 to −6 | −5 to 5 | 6 to 10 | 11 to 15 | 16 to 25 | >25 |

| SE | |||||||||

| PIM | 1 (1) | 8 (12) | 8 (12) | 20 (29) | 18 (26) | 3 (4) | 4 (6) | 6 (9) | 0 |

| TAT | 3 (4) | 13 (19) | 15 (22) | 16 (24) | 10 (15) | 4 (6) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 3 (4) |

| ZCM | 0 | 5 (7) | 3 (4) | 11 (16) | 24 (35) | 7 (10) | 2 (3) | 6 (9) | 10 (15) |

TST = total sleep time, WASO = wake after sleep onset, SE = sleep efficiency, PSG = polysomnography, PIM = proportional integration mode, TAT = time above threshold, ZCM = zero crossings mode

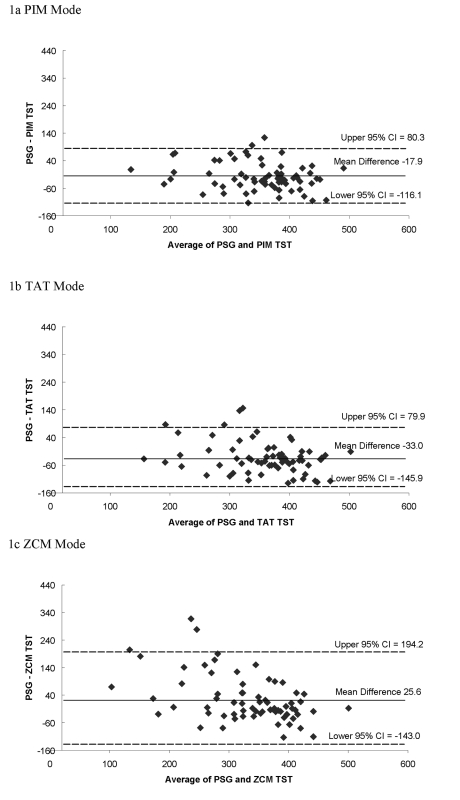

Examining the Bland and Altman plots comparing PSG to actigraphic TST showed a systematic bias towards overestimation for the PIM and TAT modes (Figure 1). The plots also show the actigraphic TST measurement corresponded more closely to PSG when TST was longer for the ZCM mode, showing a systematic bias in misclassification for short sleepers. The mean difference between actigraphic and PSG measurement of TST is closer to 0 (agreement) for the PIM mode, which had a more compact clustering of differences and a more compact 95% confidence interval for the mean difference.

Figure 1.

Bland and Altman Plots of Total Sleep Time, min. TST = total sleep time, PSG = polysomnography, PIM = proportional integration mode, TAT = time above threshold, ZCM = zero crossings mode, CI = confidence interval; Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence intervals, solid line is the mean difference.

Exploring Associations of Participant Characteristics and the Differences between TST from PSG and Actigraphy (PIM mode)

As shown in Table 4, those women with lower TST as measured by actigraphic PIM mode had a significant association to the difference in PSG-PIM mode TST (P < 0.001). When compared to women with >5 to 8 hr of PIM TST, women with ≤5 hr had an underestimate of PSG TST by 68 min on average. Those women with lower SE as measured by PSG had a significant association with the misclassification of sleep by actigraphy (P < 0.03). For those women with SE <70% by PSG, the PIM mode of actigraphy on average overestimated TST from PSG by 31 min. Self-reported poor sleepers, as defined by PSQI >5, had an average underestimation of TST of 24 min from the PIM mode when compared to TST from PSG (P = 0.044). No other characteristics examined, including age, BMI, functional status, and cognition, were significantly associated to the difference in PSG and actigraphic PIM mode estimation of TST (P > 0.10, data not shown).

Table 4.

Sleep Variables and Characteristics Predicting the Difference in PSG and Actigraphic PIM mode Calculation of Total Sleep Time (outcome = PSG-PIM mode TST)

| Predictor | Unit | Beta Coefficient (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actigraphy data (PIM mode): | |||

| Total sleep time, min | 30 min | −12.4 (−16.7, −8.2) | <0.001 |

| Total sleep time ≤5 hr | 1 | 68.0 (29.9, 106.0) | <0.001 |

| Total sleep time >5 to 8 hr | Reference | — | — |

| Total sleep time > 8 hr | 1 | −34.6 (−70.1, 1.0) | 0.061 |

| PSG data: | |||

| Sleep efficiency, % | 10% decrease | −11.1 (−20.6, −1.5) | 0.027 |

| Sleep efficiency <70% | 1 | −30.9 (−57.1, −4.8) | 0.024 |

| Characteristics: | |||

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | 1 | 3.1 (0.1, 6.1) | 0.045 |

| Self-reported poor sleep (PSQI >5) | 1 | 24.5 (1.2, 47.8) | 0.044 |

TST = total sleep time, PSG = polysomnography, PIM = proportional integration mode, CI = confidence interval, PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Comparison of Sleep Fragmentation Calculated by Polysomnography and Actigraphy

As with TST, the PIM mode of actigraphy corresponded better with PSG for measures of sleep fragmentation. For the PIM mode, there was no significant difference between the 2 procedures in calculation of WASO (P = 0.2657), with an average overestimation of 6.7 min (range −128 to 104) and a correlation of 0.58 (Table 2). The PIM mode had fewer extreme differences in WASO, with 25% of the actigraphy measurements falling within 15 min of the PSG measurements (Table 3). The PIM mode measurement of sleep efficiency did differ from PSG (P = 0.0056), with an average underestimation of 3.9% (range −25.5 to 95.6) and intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.61 (Table 2). Twenty-six percent of the PIM mode actigraphy measurements fell within a 5% difference in sleep efficiency when compared to PSG (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

We found a moderate to high correlation between TST measured concurrently by PSG and all three modes of actigraphy among this population of community-dwelling elderly women. Our analyses also showed a moderate level of agreement for SE and WASO. Results suggested some misclassification for sleep parameters derived by actigraphy, particularly systematic overestimation of sleep duration and SE and underestimation of WASO. The biases were greatest amongst individuals with more fragmented or poorer sleep and those with sleep durations in the extreme ranges in this population.

Of the 3 actigraphic modes for activity measurement considered—PIM, TAT, and ZCM—the PIM mode of activity collection yielded measures which compared best to PSG in this population. Both PIM and TAT modes tended to overestimate sleep and sleep efficiency, while the ZCM mode tended to underestimate TST and SE. In addition to having a higher intraclass correlation than the other 2 modes, the PIM mode also showed fewer extreme differences and showed no statistically significant difference in the measurement of WASO.

The goal within SOF is to have the most accurate actigraphic measures of sleep parameters compared to PSG. Our data suggest that a mode such as the PIM, which utilizes information on movement acceleration and amplitude, is more accurate in inferring sleep from wake periods in older women who have a high prevalence of sleep disordered breathing and sleep complaints. Although ZCM is more commonly used and may be preferred in other populations,7,9 for older community-dwelling women the actigraphic data from the PIM mode is most reliable.

Even though the level of agreement between PSG and actigraphy was moderate to high, the differences between calculation of TST by all 3 actigraphy modes and PSG were statistically significant, and subgroups of individuals were differentially classified. The PIM and TAT modes systematically overestimated sleep on average. Overestimation of sleep time by actigraphy has been previously reported in studies of healthy volunteers, sleep disordered patients, and depressed patients.7,12,13,16 This overestimation of sleep by actigraphy may be due to decreased activity and movement in this older population. As sleep quality decreased, the correlation was reduced. The extent of overestimation of TST by the PIM mode of actigraphy was highest among participants with lower SE, suggesting that long periods of wakefulness were unaccompanied by movement in many of these study participants. In contrast, underestimation of PSG TST by the PIM mode was found for women who self-report poor sleep (determined by PSQI) and for those who had ≤5 hr sleep, determined by actigraphy. This suggests that in these subgroups, sleep disturbances may increase underlying nocturnal movements and cause sleep to be underestimated by actigraphy. There was a lack of systematic bias introduced by other health conditions, such as cognitive function, medical conditions, depression, and physical performance (P > 0.10). These data suggest that actigraphy measures to infer differences in sleep duration among individuals with disturbed sleep should be interpreted cautiously, with potential overestimation of TST averaging as high as 31 min in those women with a PSG SE of <70%.

The differences between the PSG and actigraphy based measurement of TST, WASO and SE may be more pronounced if categorizing the variables for classification of potential sleep problems. In our prior analyses, we have focused on identifying health outcomes in subgroups with extreme sleep patterns identified by dichotomizing actigraphy derived sleep measures, with thresholds such as a TST of ≤5 hr, SE less than 70%, and WASO ≥90 min.35–37 Using these cutpoints in our subset of 68 women, the amount of misclassification for the TST categorical variable would be 19%; for WASO 31%; and for SE 25%. Thus, sensitivity analyses may be needed to fully interpret the implications of data from such epidemiological data sets.

This study had several strengths. We compared 3 different modes of actigraphy to polysomnography. The data was collected in the home rather than in a sleep laboratory, so the disruption of sleep by an unfamiliar environment was minimalized. The sample size allowed for the examination of associations of the measurement error and some of the sleep and participant characteristics.

This study also had limitations. The study protocol did not require concurrent measurement of PSG and actigraphy, making it impossible to use data for all 456 women who had both polysomnography and actigraphy measured. Those 388 women with both measures whom were not included in the analysis differed from our analysis subset by many characteristics, including arousal index, sleep latency, and medical conditions (P < 0.05). Clock times for PSG and actigraphy were not synchronized, so there may be differences in machine times, although slight. PSG data were collected in 30-sec epochs, and actigraphy data was collected in 1-min epochs. Because of this lack of clock synchronization and differing epoch lengths, direct comparison of each epoch using the two methods is not possible, and sensitivity/specificity analysis cannot be performed. We also addressed only one actigraph system (Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc). Given the unique characteristics of actigraph devices and software among manufacturers, differing results may be expected with use of alternative methods of collecting, filtering, and analyzing actigraphy data.

In conclusion, although there are limitations to using actigraphy, data from the actigraphic system studied did correspond reasonable well to the ambulatory PSG measures of total sleep time. The proportional integration mode of actigraphy correlated best with PSG in this population. There was a significant relationship of total sleep time, SE, and self-reported poor sleep to the difference of the measurement of total sleep time by PSG and actigraphy, indicating that measurement error may be greatest for individuals with poorest sleep quality. Actigraphy may provide variable estimation of TST among populations with different movement and sleep patterns, so further examination for other populations may be necessary. Actigraphy does not replace PSG in sleep estimation, but was a convenient, affordable and accurate method of collecting measurements of sleep in a large epidemiologic study of older women.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Investigators in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group: San Francisco Coordinating Center (California Pacific Medical Center Research Institute and University of California San Francisco): SR Cummings (principal investigator), MC Nevitt (co-investigator), DC Bauer (co-investigator), DM Black (co-investigator), KL Stone (co-investigator), W Browner (co-investigator), R Benard, T Blackwell, PM Cawthon, L Concepcion, M Dockrell, S Ewing, C Fox, R Fullman, SL Harrison, M Jaime-Chavez, L Lui, L Palermo, M Rahorst, D Robertson, C Schambach, R Scott, C Yeung, J Ziarno

University of Maryland: MC Hochberg (principal investigator), L Makell (clinic coordinator), MA Walsh, B Whitkop.

University of Minnesota: KE Ensrud (principal investigator), S Diem (co-investigator), M Homan (co-investigator), D King (Program Coordinator), N Michels (Clinic Director), S Fillhouer (Clinic Coordinator), C Bird, D Blanks, C Burckhardt, F Imker-Witte, K Jacobson, K Knauth, N Nelson, M Slindee.

University of Pittsburgh: JA Cauley (principal investigator), LH Kuller (co-principal investigator), JM Zmuda (co-investigator), L Harper (project director), L Buck (clinic coordinator), C Bashada, W Bush, D Cusick, A Flaugh, A Githens, M Gorecki, D Moore, M Nasim, C Newman, N Watson.

The Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland, Oregon: T Hillier (principal investigator), E Harris (co-investigator), E Orwoll (co-investigator), K Vesco (co-investigator), J Van Marter (project director), M Rix (clinic coordinator), A MacFarlane, K Pedula, J Rizzo, K Snider, T Suvalcu-constantin, J Wallace.

This work was performed at the San Francisco Coordinating Center. Supported by NIH grants AG05407, AR35582, AG05394, AR35584, AR35583, AG08415.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PSG

polysomnography

- TST

total sleep time

- SE

sleep efficiency

- WASO

wake after sleep onset

- SOF

Study of Osteoporotic Fractures

- EEG

electroencephalograms

- EOG

electrooculogram

- EMG

electromyogram

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- AHI

apnea hypopnea index

- ZCM

zero crossings mode

- PIM

proportional integration mode

- TAT

time above threshold mode

- UCSD

University of California San Diego

- GDS

Geriatric Depression Scale

- PSQI

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- MMSE

the Mini-Mental State Examination

- IADL

independent activities of daily living

- BMI

body mass index

- SD

standard deviation

- ICC

intraclass correlation coefficient

- CI

confidence interval

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

This was not an industry supported study. Ms Blackwell has received research support from Eli Lilly. Dr. Redline has received equipment from Respironics for use in an NIH-sponsored trial. Dr. Ancoli-Israel has participated in speaking engagements for Cephalon, King, Neurocrine Biosciences, Sanofi-Aventis, and Sepracor; has been a consultant or on the advisory board of Acadia, Cephalon, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, King, Merck, Neurocrine Biosciences, Neurogen, Sanofi-Aventis, Sepracor, and Takeda; and has received Litebooks from the Litebook Company for use in research. Dr. Cauley has received research support from Merck, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Novartis; is on the speakers bureau for Merck; and has received honorarium from Merck, Novartis, and Eli Lilly. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ancoli-Israel S, Cole R, Alessi CA, et al. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep. 2003;26:342–92. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webster JB, Kripke DF, Messin S, Mullaney DJ, Wyborney G. An activity-based sleep monitor system for ambulatory use. Sleep. 1982;5:389–99. doi: 10.1093/sleep/5.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jean-Louis G, von Gizycki H, Zizi F, et al. Determination of sleep and wakefulness with the actigraph data analysis software (ADAS) Sleep. 1996;19:739–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsumoto M, Miyagishi T, Sack RL, Hughes RJ, Blood ML, Lewy AJ. Evaluation of the Actillume wrist actigraphy monitor in the detection of sleeping and waking. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;52:160–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1998.tb01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jean-Louis G, Kripke DF, Cole RJ, Assmus JD, Langer RD. Sleep detection with an accelerometer actigraph: comparisons with polysomnography. Physiol Behav. 2001;72:21–8. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollak CP, Tryon WW, Nagaraja H, Dzwonczyk R. How accurately does wrist actigraphy identify the states of sleep and wakefulness? Sleep. 2001;24:957–65. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.8.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Souza L, Benedito-Silva AA, Pires ML, Poyares D, Tufik S, Calil HM. Further validation of actigraphy for sleep studies. Sleep. 2003;26:81–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mullaney DJ, Kripke DF, Messin S. Wrist-actigraphic estimation of sleep time. Sleep. 1980;3:83–92. doi: 10.1093/sleep/3.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole RJ, Kripke DF, Gruen W, Mullaney DJ, Gillin JC. Automatic sleep/wake identification from wrist activity. Sleep. 1992;15:461–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauri PJ, Wisbey J. Wrist actigraphy in insomnia. Sleep. 1992;15:293–301. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jean-Louis G, Zizi F, von Gizycki H, Hauri P. Actigraphic assessment of sleep in insomnia: application of the Actigraph Data Analysis Software (ADAS) Physiol Behav. 1999;65:659–63. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kushida CA, Chang A, Gadkary C, Guilleminault C, Carrillo O, Dement WC. Comparison of actigraphic, polysomnographic, and subjective assessment of sleep parameters in sleep-disordered patients. Sleep Med. 2001;2:389–96. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedner J, Pillar G, Pittman SD, Zou D, Grote L, White DP. A novel adaptive wrist actigraphy algorithm for sleep-wake assessment in sleep apnea patients. Sleep. 2004;27:1560–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadeh A, Sharkey KM, Carskadon MA. Activity-based sleep-wake identification: an empirical test of methodological issues. Sleep. 1994;17:201–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.3.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ancoli-Israel S, Clopton P, Klauber MR, Fell R, Mason W. Use of wrist activity for monitoring sleep/wake in demented nursing-home patients. Sleep. 1997;20:24–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jean-Louis G, Mendlowicz MV, Gillin JC, et al. Sleep estimation from wrist activity in patients with major depression. Physiol Behav. 2000;70:49–53. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson NL, Kirchner HL, Rosen CL, et al. Sleep estimation using wrist actigraphy in adolescents with and without sleep disordered breathing: a comparison of three data modes. Sleep. 2007;30:899–905. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.7.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooke JR, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep and its disorders in older adults. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29:1077–93. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummings SR, Black DM, Nevitt MC, et al. Appendicular bone density and age predict hip fracture in women: The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. JAMA. 1990;263:665–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogt MT, Rubin DA, Palermo L, et al. Lumbar spine listhesis in older African American women. Spine J. 2003;3:255–61. doi: 10.1016/s1529-9430(03)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A, editors. Washington DC: National Institutes of Health; 1968. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques, and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. NIH publication 204. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Sleep Disorders Association. EEG arousals: scoring rules and examples: a preliminary report from the Sleep Disorders Atlas Task Force of the American Sleep Disorders Association. Sleep. 1992;15(2):173–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ardsley NY: Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc; Motionlogger® User's Guide: Act Millenium. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ardsley NY: Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc; Action-W User's Guide, Version 2.0. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Girardin JL, Kripke DF, Mason WJ, Elliot JA, Youngstedt SD. Sleep estimation from wrist movement quantified by different actigraphic modalities. J Neurosci methods. 2001;105:185–91. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:165–73. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Hoch CC, Yeager AL, Kupfer DJ. Quantification of subjective sleep quality in healthy elderly men and women using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Sleep. 1991;14:331–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pahor M, Chrischilles EA, Guralnik JM, et al. Drug data coding and analysis in epidemiologic studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:405–11. doi: 10.1007/BF01719664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Folstein MF, Robins LN, Helzer JE. The mini-mental state examination. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:812. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790060110016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fitti JE, Kovar MG. The supplement on aging to the 1984 National Health Interview Survey. Vital & Health Statistics-series 1: Programs & collection procedures. 1987;21:1–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pincus T, Summey JA, Soraci SA, Jr, et al. Assessment of patient satisfaction in activities of daily living using a modified Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26:1346–53. doi: 10.1002/art.1780261107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shrout PE, Fleiss LJ. Interclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–28. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Group. Yaffe K, Blackwell T, Barnes DE, Ancoli-Israel S, Stone KL. Preclinical cognitive decline and subsequent sleep disturbance in older women. Neurology. 2007;69:237–42. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000265814.69163.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Ensrud KE, Blackwell TL, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and sleep disturbances in community-dwelling older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1508–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Group. Blackwell T, Yaffe K, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Poor sleep is associated with impaired cognitive function in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:405–10. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]