Abstract

Background

Reimbursement for outpatient prescription drugs is not mandated by the Canada Health Act or any other federal legislation. Provincial governments independently establish reimbursement plans. We sought to describe variations in publicly funded provincial drug plans across Canada and to examine the impact of this variation on patients' annual expenditures.

Methods

We collected information, accurate to December 2006, about publicly funded prescription drug plans from all 10 Canadian provinces. Using clinical scenarios, we calculated the impact of provincial cost-sharing strategies on individual annual drug expenditures for 3 categories of patients with different levels of income and 2 levels of annual prescription burden ($260 and $1000).

Results

We found that eligibility criteria and cost-sharing details of the publicly funded prescription drug plans differed markedly across Canada, as did the personal financial burden due to prescription drug costs. Seniors pay 35% or less of their prescription costs in 2 provinces, but elsewhere they may pay as much as 100%. With few exceptions, nonseniors pay more than 35% of their prescription costs in every province. Most social assistance recipients pay 35% or less of their prescription costs in 5 provinces and pay no costs in the other 5. In an example of a patient with congestive heart failure, his out-of-pocket costs for a prescription burden of $1283 varied between $74 and $1332 across the provinces.

Interpretation

Considerable interprovincial variation in publicly funded prescription drug plans results in substantial variation in annual expenditures by Canadians with identical prescription burdens. A revised pharmaceutical strategy might reduce these major inequities.

Although the Canadian health care system attempts to provide universal coverage for all hospital stays and medically necessary procedures regardless of the patient's health status or ability to pay, outpatient prescription drugs are excluded from this arrangement. Because no federal guidelines or laws currently cover outpatient drug reimbursement policies, provinces establish and fund their own plans.

Prescription drugs constitute the second largest category of health spending in Canada, after hospital expenditures.1 In 2005, $20.6 billion was spent on outpatient prescription drugs, including over-the-counter and personal health products purchased as a result of a prescription or paid by a third-party insurer. Of this sum, $4 billion represents direct out-of-pocket expenditures by patients.1 Several studies2–8 have reported that patient health is potentially compromised when access to drug therapy is restricted.

Although 75% of Canadians have private insurance coverage for prescription drugs, about 25% (ranging from 9% in Manitoba to 43% in Quebec9) qualify for government reimbursement. Thus, it is crucial to understand the differences between provincial drug reimbursement policies and the potential impact of this variation on out-of-pocket expenditures. Previous studies9–12 have determined that disparities in publicly funded reimbursement policies for prescription drugs between provinces could result in cost inequities for individual patients.13 However, the nature and extent of variations within or between provinces have not been adequately characterized.

We sought to compare the extent of coverage and costs relating to publicly funded reimbursement plans for prescription drugs for seniors, nonseniors and recipients of social assistance across Canada. We used case studies and clinical scenarios to assess disparities in out-of-pocket expenditures borne by beneficiaries with identical annual prescription drug costs living in different provinces.

Methods

Provincial prescription drug plans

We collected information, accurate to December 2006, about the structure of the publicly funded prescription drug plans in all 10 Canadian provinces. We obtained these data from provincial websites14–23 and from Provincial Drug Benefit Programs,24 published by the Canadian Pharmacists Association. The data collected included eligibility criteria by category of beneficiary (seniors [age ≥ 65 years], nonseniors and social assistance recipients); cost-sharing strategies (premium, deductible, copayment and maximum annual contribution by the beneficiary); and details of pharmacists' dispensing fees and plan restrictions.

Several terms used in the study warrant definition. A “premium” is a fixed amount that a beneficiary must pay to be eligible for the reimbursement program. A “deductible” refers to a fixed amount or a percentage of income that constitutes the first portion of the costs that must be borne by the beneficiary before the insurer shares payment. A “copayment” may be a fixed amount, a percentage of the prescription cost or a percentage of income that is not reimbursed by the insurer but must be borne by the beneficiary. The “maximum annual beneficiary contribution” is the maximum amount a beneficiary will have to pay in a given year. Unless otherwise specified, all amounts are in Canadian dollars.

Clinical scenarios

We used 32 scenarios to evaluate the impact of the various provincial drug cost-sharing policies on individual annual expenditures. Four clinical scenarios featuring simulated but plausible patients were also developed to illustrate national variation in reimbursement policies.

For each scenario, 5 elements were varied: type of beneficiary (senior, nonsenior, social assistance recipient); annual household income (lower than, at, or higher than the national average); marital status (single or married); number of children (0, 1 or 2); and low or high annual prescription burden ($260 or $1000). The outcomes of interest were eligibility of individuals for reimbursement and the patient's calculated annual expenditure.

Annual household income was set as a function of after-tax national average income by economic family type, rounded to the nearest thousand Canadian dollars.25 In the senior group, we calculated Old Age Security pension and Guaranteed Income Supplement, where applicable, using figures from the Old Age Security program.26 In the senior group, a single senior and a married senior were assigned to each income category. In the general population group, a single beneficiary with 1 or 2 children, a married beneficiary with 1 or 2 children and a single beneficiary with no children were assigned to each income category. We defined the national prescription burden as the mean per capita spending on prescription drugs in the 10 provinces studied in 2005.1 It amounted to $260. We chose the $1000 expenditure level arbitrarily to reflect a high burden of expense. In the clinical scenarios, prescription costs reflected 2006 drug prices. In every scenario, we chose drugs that were listed in the provincial drug formularies.

We calculated annual out-of-pocket expenditures for each simulated patient according to the cost-sharing rules specific to each of the Canadian provinces studied. We used the maximum professional fee in each province for 2006 to calculate the total annual prescription cost; this fee varied between $7 and $25.97.24 Because most provinces allow a medication supply for 100 days,24 we assumed that prescriptions were renewed 4 times a year. In the clinical scenarios, we set the number of drugs dispensed per visit to a pharmacy at 2.

For the clinical scenarios, we categorized the annual out-of-pocket expenditures into 4 groups: ≤ 35% of total prescription costs and professional fees paid by user; > 35% but < 100% paid by user; 100% paid by user; and > 100% of total prescription costs and professional fees paid by user.

For the simulated patients, we calculated annual prescription costs using the Quebec drug formulary.27

Results

We found that the provincial drug plans have different criteria for reimbursement. Premiums, deductibles, copayments and maximum annual beneficiary contributions varied across the provinces and influenced the magnitude of the annual costs incurred by Canadian patients.

Details of the reimbursement plans

The senior population includes all Canadians aged 65 years and older who are not covered, partly or otherwise, by a private insurance plan. Even though every senior in Canada is covered by a provincially funded drug plan, we found that the extent of the coverage varies (see Appendix 1, available online at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/178/4/405/DC2/1).

The nonsenior population includes all residents of Canada between 18 and 65 years old who are not covered, partly or otherwise, by a private drug insurance plan. Although most of the provinces have incorporated nonseniors into their policies, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador do not offer public insurance for this age group. Prince Edward Island offers reimbursement to those whose annual household income is less than $22 000. In most provinces, special plans for families with very low incomes are available. Specific details pertaining to the individual provincial reimbursement policies for nonseniors are shown in Appendix 2, available online at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/178/4/405/DC2/2.

British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador offer full reimbursement of drug costs to social assistance recipients. Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Quebec have variable reimbursement policies (see Appendix 3, available online at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/178/4/405/DC2/3).

Simulations and clinical scenarios

Annual drug-cost categories for the various clinical scenarios are displayed in Appendix 4, which is available online at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/178/4/405/DC2/4.

Low-income seniors: For seniors with an annual household income below the national average, all plans offer some level of drug reimbursement. In British Columbia, Ontario, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador, beneficiaries pay 0%–35% of their annual prescriptions costs, regardless of their prescription burden. In Alberta and Nova Scotia, beneficiaries pay 35%–100% of their prescription costs and professional fees, regardless of their annual prescription burden.

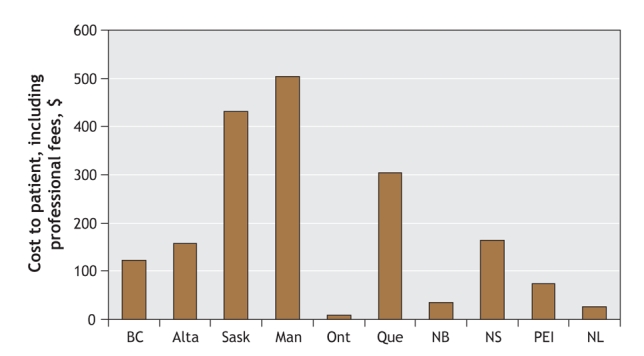

For the patient described in Figure 1, the annual cost of prescription drugs is $454. She will pay an out-of-pocket sum varying from $8 in Ontario to $503 in Manitoba (Figure 1). (Note: Because the calculated total by province includes professional fees, it may be higher than the cost of the drugs in some provinces.)

Figure 1: Variation, by province, in annual drug costs paid by a 65-year-old woman whose annual income is below the national average. The patient has diabetes mellitus, hypertension and insomnia and is married to a senior receiving Old Age Security and Guaranteed Income Supplement. Their annual household income is $23 315. The patient's prescription drugs are metformin (850 mg twice daily), lorazepam (0.5 mg at bedtime), hydrochlorothiazide (25 mg/d) and ramipril (5 mg/d). The total annual cost of the drugs is $454 excluding professional fees.

Seniors with income at or above the national average: According to our case scenarios, seniors with an income at or above the national average living in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island pay 0%–35% of their prescription costs, regardless of their prescription burden. In Ontario and Nova Scotia, the same senior would also pay 0%–35% of their prescription cost, but only if he or she had a high prescription burden (≥ $1000). For a prescription burden of $260 in Quebec, the annual cost to the patient exceeds prescription costs by an amount that depends on annual income, because this province imposes a premium on most of its beneficiaries.

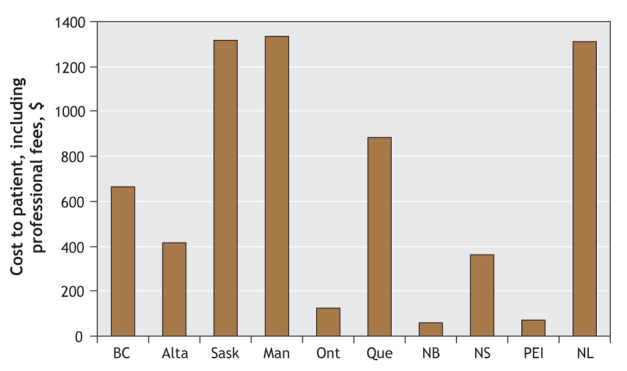

The patient described in Figure 2, who incurs an annual prescription burden of $1283, will pay from $60 in New Brunswick to $1332 in Manitoba.

Figure 2: Variation, by province, in annual drug costs paid by a 73-year-old man whose annual income is at the national average. The patient has heart failure and hyperlipidemia and is married to a senior receiving Old Age Security. Their annual household income is $44 806. The patient's prescription drugs are furosemide (20 mg twice a day), acetylsalicylic acid (80 mg/d), metoprolol (50 mg twice daily), atorvastatin (40 mg/d), ramipril (5 mg/d) and digoxin (0.125 mg/d). The total annual cost of the drugs is $1283 excluding professional fees.

Overall, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island stand out as offering the most comprehensive public prescription drug plans for seniors, with patients paying only 0%–35% of their total prescription costs, regardless of their income level. Ontario and Nova Scotia have somewhat comprehensive plans, but reimbursement is proportional to prescription costs and inversely proportional to income level. Seniors in Quebec generally pay more than their total annual prescription cost because of premiums, except for low-income seniors and those with a high prescription burden. Seniors in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Newfoundland and Labrador are covered only if they have low income.

Low-income nonseniors: In contrast with the senior population, nonseniors are offered high levels of reimbursement in only a few provinces. Most people in this category must pay the full cost of their medications unless they or their employer subscribe to a private insurance plan.

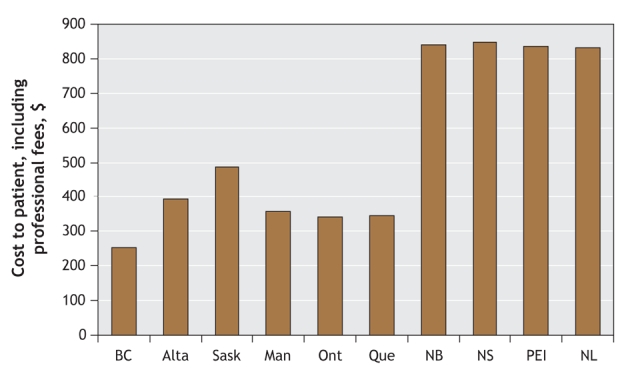

The patient described in Figure 3, whose annual prescription burden is $807, will pay from $252 in British Columbia to $849 in Nova Scotia for these medications.

Figure 3: Variation, by province, in annual drug costs paid by a 23-year-old woman whose annual income is below the national average. The patient has hypothyroidism and hyperlipidemia. She is single, has a child and works part time. Her annual household income is $14 000. Her prescription drugs are levothyroxine sodium (0.075 mg/d) and atorvastatin (40 mg/d). The total annual cost of the drugs is $807 excluding professional fees.

Nonseniors with income at or above the national average: The scenarios show that beneficiaries with income at or higher than the national average always pay more than 35% of their prescription drug costs. Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador do not offer any reimbursement to patients in this category.

Social assistance recipients: Most social assistance recipients pay 0%–35% of their annual prescription costs in all Canadian provinces with a few exceptions.

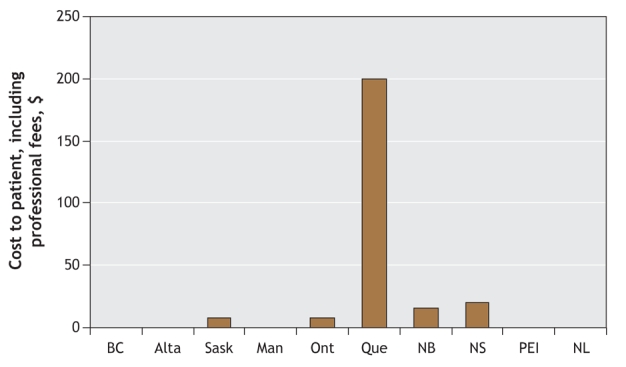

The social assistance recipient described in Figure 4 incurs an annual prescription burden of $1389. He will not pay anything in British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Prince Edward Island or Newfoundland and Labrador. However, he will pay $8 in Saskatchewan, $8 in Ontario, $200 in Quebec, $16 in New Brunswick and $20 in Nova Scotia. Prescription costs in Quebec are high, owing to higher deductibles and copayments for this specific type of beneficiary.

Figure 4: Variation, by province, in annual drug costs paid by a 40-year-old man who is an income security recipient. He has hypertension and hyperlipidemia. His prescription drugs are hydrochlorothiazide (25 mg/d), diltiazem (120 mg twice daily) and atorvastatin (40 mg/d). The total annual cost of the drugs is $1389 excluding professional fees.

Interpretation

This study highlights the marked variation among provincially funded drug reimbursement plans. The eligibility and reimbursement criteria of these plans for seniors, nonseniors and social assistance recipients differ widely across the country. Thus, the amount patients must pay for a given prescription burden is unequal across provinces. These inequities challenge one of the guiding principles of the Canadian health care system — that all Canadians should have similar levels of access to health care benefits.

Variations in reimbursement have been demonstrated for 3 population groups. First, provincial policies provide seniors with extensive drug reimbursement coverage compared with the rest of the population. Despite this, significant variations in coverage were documented. Second, in general, nonsenior Canadians pay a substantial part of the cost of their medications even where public plans are offered for this subgroup. However, discrepancies in reimbursement of nonseniors across provinces are less marked than for seniors. Third, although differences in coverage exist for social assistance recipients, provincial plans either provide some kind of protection for this group (Saskatchewan, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia) or offer full coverage (British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador).

There have been previous studies on provincial drug reimbursement plans9–13 and their impact on drug use.28 Our study demonstrates the inequities among publicly funded drug reimbursement plans across the country. This report includes insight into variations in out-of-pocket expenditures for populations with different individual characteristics (age, marital status, income) according to their province of residence. Furthermore, the case-based study design featuring patients with common health problems prescribed frequently used drugs allows us to provide “real world” examples of such variation and to foresee the impact of drug reimbursement policies on Canadians. Our study supports recent reports recommending that a national pharmaceutical strategy be considered as a way to achieve universal access to drugs.13–24,26,29–32 A national formulary with similar cost-sharing policies across the country could potentially reduce these inequities and reduce the influence of geography on access to medications in the Canadian health care system.

This study has several limitations. First, we explored variations only in drugs listed on provincial formularies. Substantial additional variation exists with respect to reimbursement policies for drugs not listed on the formularies or listed as restricted medications. Second, to conduct a simulation study, we had to make several assumptions. We chose each variable in an effort to cover a wide variety of possible cases, but the number of scenarios is limited. Third, we did not consider potentially important variables such as differences in pricing strategies across provinces or differences in drug listings on provincial formularies. Finally, individual provinces run special programs to cover the drug expenses of specific subgroups of the population, including very-low-income families and people who are HIV positive or have diabetes. Incorporating these variables into our simulation was beyond the scope of this study; thus, it may not be possible to generalize our findings to these populations.

Despite these limitations, our study provides a contemporary portrait of publicly funded drug reimbursement plans for seniors, nonseniors and recipients of social assistance across Canada. Given differences in reimbursement according to age, income level, marital status and province of residence, prescription drug reimbursement in Canada is manifestly unequal. Although current provincial drug plans provide good protection for isolated groups, most Canadians still have unequal coverage for outpatient prescription drugs.

Our observations are timely given that prescription drugs are accounting for an increasing portion of Canadian health care costs. Financial hardships due to drug expenses have already been shown to affect the health of some Canadians adversely.2–8 Also, differences in drug access may lead to different clinical outcomes across the country. Policy-makers may want to consider a consistent pan-Canadian approach to prescription drug coverage.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Team Grant in Cardiovascular Outcomes Research awarded to the Canadian Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Team (CCORT). Virginie Demers is supported by a CCORT student grant funded through a CIHR Team Grant in Cardiovascular Outcomes Research. Dimitri Kalavrouziotis is supported by a CCORT master's student fellowship. Stéphane Rinfret is a junior physician scientist supported by the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec. Karin Humphries is supported by a CIHR New Investigator Award. Jack Tu is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Health Services Research and a Career Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario. Louise Pilote is a William Dawson Chair and an investigator supported by the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec.

Footnotes

Une version française de ce résumé est disponible à l'adresse www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/178/4/405/DC1

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All of the authors contributed to the study conception and design. Virginie Demers and Louise Pilote contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. All of the authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Competing interests: None declared for Virginie Demers, Magda Melo, Cynthia Jackevicius, Dimitri Kalavrouziotis, Karin Humphries, Helen Johansen, Jack Tu or Louise Pilote. Jafna Cox has received honoraria or consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Pfizer Canada and Sanofi-Aventis and has received research funding support from Merck and Pfizer Canada. Stéphane Rinfret has received research grants and consulting fees from Pfizer Canada, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Sanofi-Aventis.

Correspondence to: Dr. Louise Pilote, Division of General Internal Medicine, McGill University Health Centre, 687 Pine Ave. W, Rm. A4.23, Montréal QC H3A 1A1; louise.pilote@mcgill.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.Drug expenditure in Canada 1985 to 2005: National Health Expenditure Database. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2006. Available: http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca/Collection/H115-27-2005E.pdf (accessed 2007 Dec 10).

- 2.Tamblyn R, Laprise R, Hanley JA, et al. Adverse events associated with prescription drug cost-sharing among poor and elderly persons. JAMA 2001;285:421-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Soumerai SB, McLaughlin TJ, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Effects of a limit on Medicaid drug-reimbursement benefits on the use of psychotropic agents and acute mental health services by patient with schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 1994;331:650-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Anis AH, Guh DP, Lacaille D, et al. When patients have to pay a share of drug costs: effects on frequency of physician visits, hospital admissions and filling of prescriptions. CMAJ 2005;173:1335-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Johnson RE, Goodman MJ, Hornbrook MC et al. The impact of increasing patient prescription drug cost sharing on therapeutic classes of drugs received and on the health status of elderly HMO members. Health Serv Res 1997;32:103-22. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Lexchin J, Grootendorst P. Effects of prescription drug user fees on drug and health services use and on health status in vulnerable populations: a systematic review of the evidence. Int J Health Serv 2004;34:101-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Soumerai SB, Ross Degnan D, Avorn J, et al. Effects of Medicaid drug-payment limits on admission to hospitals and nursing homes. N Engl J Med 1991;325:1072-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Soumerai SB, Pierre-Jacques M, Zhang F, et al. Cost-related medication nonadherence among elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries: a national survey 1 year before the Medicare drug benefit. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1829-35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Kapur V, Basu K. Drug coverage in Canada: Who is at risk? Health Policy 2005; 71: 181-93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Gregoire JP, MacNeil P, Skilton K, et al. Inter-provincial variation in government drug formularies. Can J Public Health 2001;92:307-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Angus DE, Karpetz HM. Pharmaceutical policies in Canada. Issues and challenges. Pharmacoeconomics 1998;14(Suppl 1):81-96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Anis AH, Guh D, Wang XH. A dog's breakfast: prescription drug coverage varies widely across Canada. Med Care 2001;39:315-26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Coombes ME, Morgan SG, Barer ML, et al. Who's the fairest of them all? Which provincial pharmacare model would best protect Canadians against catastrophic drug costs? Healthc Q 2004;7(4 Suppl):13-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.PharmaCare: general information. Victoria: British Columbia Ministry of Health; 2006. Available: www.healthservices.gov.bc.ca/pharme/generalinfo/generalinfoindex.html (accessed 2006 Dec 15).

- 15.Health care insurance plan: prescription drug programs. Edmonton: Alberta Health and Wellness. Available: www.health.gov.ab.ca/ahcip/ahcip_prescription.html (accessed 2006 Dec 15).

- 16.Manitoba Pharmacare Program information: 2007–2008. Winnipeg: Manitoba Health. Available: www.gov.mb.ca/health/pharmacare/index.html (accessed 2006 Dec 15).

- 17.Prescription drug program. Fredericton: New Brunswick Department of Health. Available: www.gnb.ca/0051/0212/index-e.asp (accessed 2006 Dec 16).

- 18.Overview of the Newfoundland and Labrador Prescription Drug Program. St. John's: Health and Community Servces, Newfoundland and Labrador. Available: www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/nlpdp/overview.htm (accessed 2006 Dec 16).

- 19.Nova Scotia Pharmacare: drug programs and funding. Halifax: Nova Scotia Department of Health. Available: www.gov.ns.ca/heal/pharmacare/default.htm (accessed 2006 Dec 16).

- 20.Ontario Drug Benefit: the program. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2006. Available: www.health.gov.on.ca/english/public/pub/drugs/odb.html (accessed 2006 Dec 17).

- 21.Drug formulary. Charlottetown: Government of Prince Edward Island. Available: www.gov.pe.ca/hss/formulary/index.php3 (accessed 2008 Jan 9).

- 22.Prescription drug insurance. Québec: Régie de l'assurance maladie du Québec. Available: www.ramq.gouv.qc.ca/en/citoyens/assurancemedicaments/index.shtml (accessed 2006 Dec 16).

- 23.Drug Plan and Extended Benefits Branch. Web site of Saskatchewan Health; 2007. Available: http://formulary.drugplan.health.gov.sk.ca (accessed 2006 Dec 16).

- 24.Provincial drug benefit programs. 32nd ed. Ottawa: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2006.

- 25.Household, family and personal income. Summary tables. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. Available: http://cansim2.statcan.ca/cgi-win/cnsmcgi.pgm?LANG=E&ResultTemplate=SRCH4&CIITpl=CII_&CORCMD=GetTRel&CORId=2812&CORRel=5 (accessed 2007 Dec 16).

- 26.Tables of rates for Old Age Security, Guaranteed Income Supplement and the Allowance. Ottawa: Service Canada. Available: http://www1.servicecanada.gc.ca/en/isp/oas/tabrates/tabmain.shtml (accessed 2006 Dec 16).

- 27.Liste des médicaments. Québec: Régie de l'assurance maladie Québec; Oct 2006.

- 28.Pilote L, Beck C, Richard H, et al. The effects of cost-sharing on essential drug prescriptions, utilization of medical care and outcomes after acute myocardial infarction in elderly patients. CMAJ 2002;167:246-52. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Average cost per prescription dispensed in retail pharmacies, 2001–2005. IMS Health [Canada]; 2006. Available: www.imshealthcanada.com/vgn/images/portal/cit_40000873/6/14/79014599Trends05_En061129.pdf (accessed 2006 Dec 15).

- 30.Average income after tax by economic family types (2000–2004). Ottawa: Statistics Canada. Available: http://www40.statcan.ca/l01/cst01/famil21a.htm (accessed 2007 Feb 20).

- 31.ESI Canada 2003 drug trend report. Halifax: Maritime Life. Available: http://groupbenefits.manulife.com/canada/GB_V2.nsf/LookupFiles/MaritimeBulletinMaritimeBulletin1404/$File/BenefitsBulletin14English.pdf (accessed 2007 Dec 16).

- 32.National Forum on Health. Canada health action: building on the legacy. Volume I: Final report of the National Forum on Health. Ottawa: The Forum; 1997. Available: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/pubs/renewal-renouv/1997-nfoh-fnss-v1/index_e.html (accessed 2008 Jan 7).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.