In North America, there is a low incidence of leptospirosis that occurs as a result of direct transmission of the bacterium from dogs to its owners and their families. It is not mandatory for leptospirosis to be reported to health authorities in Canada, thus it is likely underreported. It is important to take the precautions outlined below to reduce the risk of exposure, especially when young children and elderly people are involved.

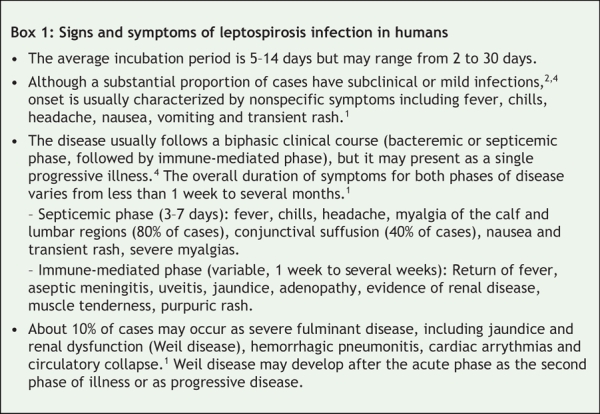

Leptospirosis, also known as fall fever or mud fever, affects both animals and humans (Figure 1). The disease is caused by the spirochete Leptospira, which has about 200 serotypes.1–3 The severity of illness may depend on the serotype, and it can range from an asymptomatic infection to a fatal illness involving the kidneys, liver and other vital organs (Box 1). However, there is no serotype-specific presentations of infection, and each serotype may cause mild or severe disease depending on the host. The virulence factors of leptospires are poorly understood. Patient factors such as old age and multiple underlying medical problems are often associated with more severe clinical illness and increased mortality.5 The infectious dose may also have an influence on the course of leptospirosis.

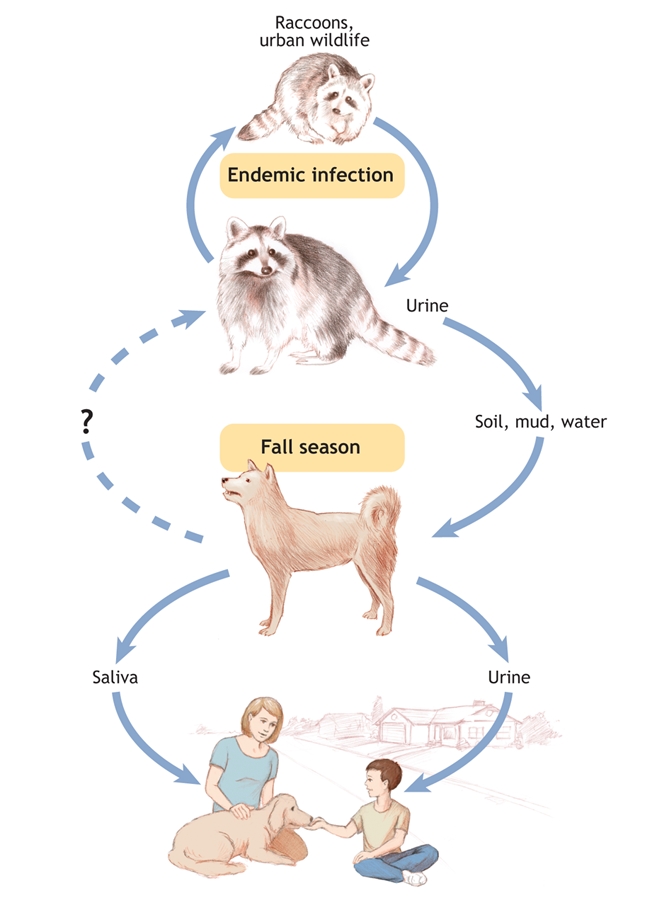

Figure 1: Transmission of leptospirosis infection from reservior species to humans.. Image by: Lianne Friesen and Nicholas Woolridge

Box 1.

This disease occurs worldwide, and the highest prevalence is in tropical climates and in warm and wet environments with poor sanitary conditions. The advent of animal vaccines against specific serotypes has reduced the risk of transmission to humans.6 Before the serotype Leptospira canicola was controlled in dogs by immunization, for example, cases of very serious disease involving disseminated intravascular coagulation were reported in children in the United States.6 In Canada, cases involving humans are uncommon. However, the incidence of infections in domestic dogs has risen markedly in recent years in the United States and Canada,7 thus veterinarians and physicians should be alert to the possibility of transmission.

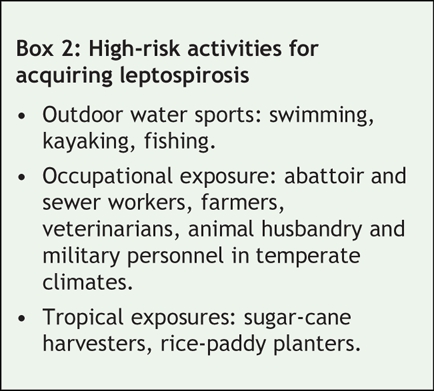

A variety of wild and domestic animals can act as reservoir hosts for 1 or more serotypes and can shed the organism in their urine for months or years after being infected (Figure 1). This includes dogs, rats, swine, cattle and, in North America, raccoons.2 Pets may come into contact with leptospires by contact with wildlife urine or farm animal reservoirs through activities such as swimming, drinking or walking through contaminated water, soil or mud. Humans become infected through contact of mucosal surfaces or abraded skin with contaminated soil or water or with animal urine or tissues. For example, participating in recreational activities in contaminated water increases the risk of infection (Box 2).1 Disease activity tends to be higher during the autumnal climate that occurs in most of the populated areas of Canada.

Box 2.

Diagnosis

Because of the difficulties associated with isolating leptospires, diagnosis in humans is based on serology. Samples are sent to the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg, Manitoba, from the public health laboratory in each province. Seroconversion may occur as early as 5–7 days after onset of the disease but may take more than 10 days. Increases in antibody titre can be delayed or absent in some patients.1

Standard texts suggest that penicillin is the antibiotic of choice for treating leptospirosis and that treatment should be initiated early in the course of illness.2 However, a recent Cochrane review suggested that there is insufficient evidence to provide clear guidelines for practise.8 Treatment of experimentally infected laboratory animals and veterinary experience in treating dogs supports the efficacy of amoxicillin (ampicillin) or doxycycline (minocycline) as the drugs of choice for treatment.9

Prevention

In North America, there is no currently available vaccine for humans against leptospirosis, although there is a vaccine that is given to workers in rice-paddy fields in China. Vaccines can only protect against the serotype, or at best the serogroup, present in the vaccine components, thus vaccines that include several antigens may be needed. Protection is short-lived and boosting is required. Vaccines may produce side effects such as pain at the injection site and fever.5

People at high risk of infection (Box 2) may need to be educated about their risk of exposure. Attention to hygienic standards, such as rodent and urban wildlife control, can reduce the risk of exposure. For adults with short-term, high-risk exposure to leptospirosis, doxycycline provides effective prophylaxis when administered weekly as a single oral dose of 200 mg.10 In general, chemoprophylaxis with antibiotics for members of families with an infected dog is not recommended, but it could be considered following consultation with an infectious disease specialist. Pregnant women are at risk of abortion following exposure to leptospires and are prime candidates for prophylactic antibiotic therapy.

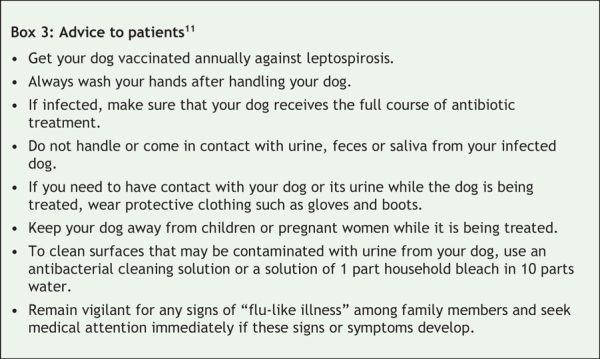

Dogs may be exposed to leptospires that have been excreted in the urine of wild animals or other dogs, thus it is difficult to prevent exposure. Surprisingly, leptospirosis is very rare in cats. The best protection for the family is to ensure that their dogs are vaccinated annually and that the vaccine protects against the newer serotypes L. grippotyphosa and L. pomona and against the older serotypes, L. canicola and L. icterohemorrhagiae (Box 3). Leptospirosis infection in dogs can be treated with appropriate antibiotics, which are highly effective in preventing urinary shedding.9

Box 3.

Leptospirosis may be virtually impossible to eradicate in wildlife (especially racoons) and opportunities to pass the infection to domestic pets will be constant. Although the risk of acquiring disease from domestic pets is considered to be low, clinicians may consider family pets as a possible source of infection for patients with febrile illness. Vaccination of the family dog against leptospirosis and other zoonotic diseases is an important topic for patients to discuss with their veterinarian.

Ken Brown BASc MPA Infectious Diseases Control Division York Region Community and Health Services Newmarket, Ont. John Prescott VetMB PhD Department of Pathobiology Centre for Public Health and Zoonosis Ontario Veterinary College University of Guelph Guelph, Ont.

@ See related article page 397

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pickering LK. Red Book: 2006 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. Elk Grove Village (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 2006.

- 2.Heymann DL, editor. Control of communicable disease manual. 18th ed. Washington: American Public Health Association; 2004.

- 3.Cohen J, Powderly WG. Infections from pets. In: Infectious diseases. 2nd ed. London: Mosby; 2004. p. 971.

- 4.Bharti AR, Nally JE, Ricaldi JN et al. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect Dis 2003;3:757-71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.World Health Organization. Human Leptospirosis: guidance for diagnosis, surveillance and control. Geneva: The Organization; 2003. p. 39. Available: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2003/WHO_CDS_CSR_EPH_2002.23.pdf (accessed 2007 Dec 13).

- 6.Faine S. Leptospira and leptospirosis. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 1994. p.353.

- 7.Moore GE, Guptill LF, Glickman NW, et al. Canine leptospirosis, United States 2002-2004. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12:501-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Guidugli F, Castro A, Atallah A. Antibiotics for treating leptospirosis [review]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD001306. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Langston CE, Heuter KJ. Leptospirosis: A re-emerging zoonotic disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2003;33:791-807. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Takafuji ET, Kirkpatrick JW, Miller RN, et al. An efficacy trial of doxycycline chemoprophylaxis against leptospirosis. N Engl J Med 1984;310:497-500. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Veterinary Information Network Community Contributors. Leptospirosis and your pet: A CDC fact sheet. VeterinaryPartner.com: The Network; 2004. Available: www.veterinarypartner.com/Content.plx?P=A&S=0&C=0&A=1745 (accessed 2007 Dec 13).