Abstract

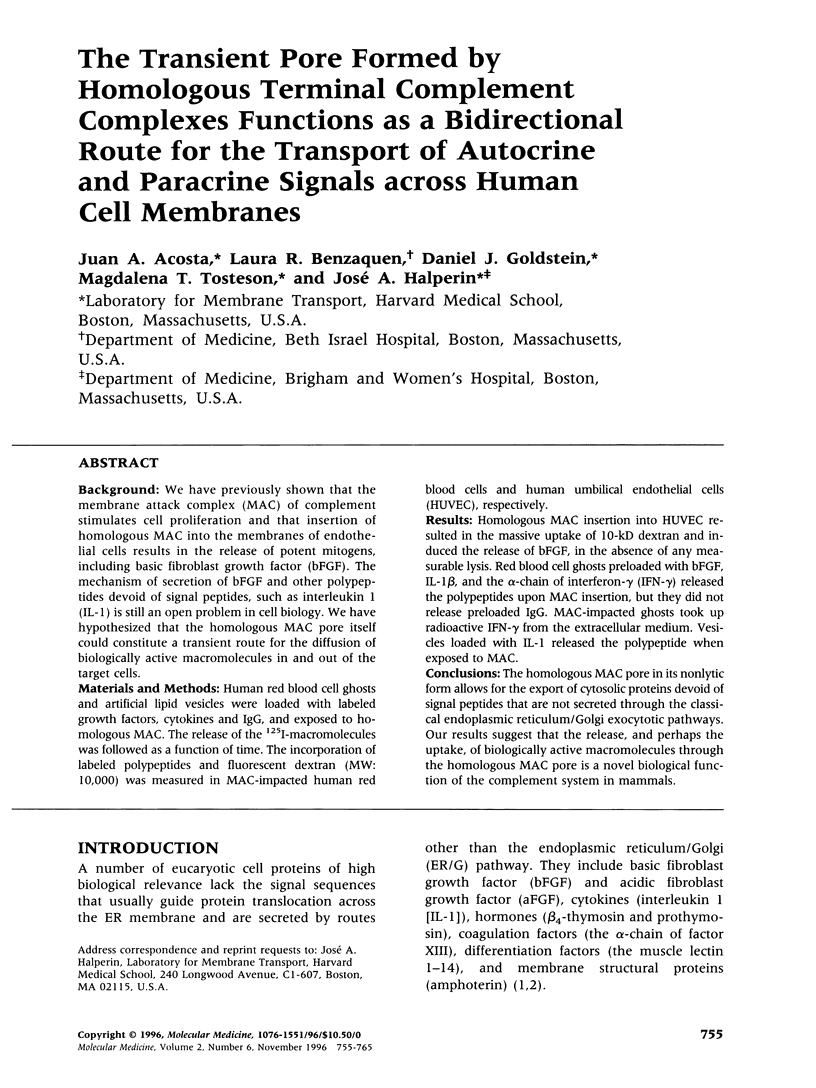

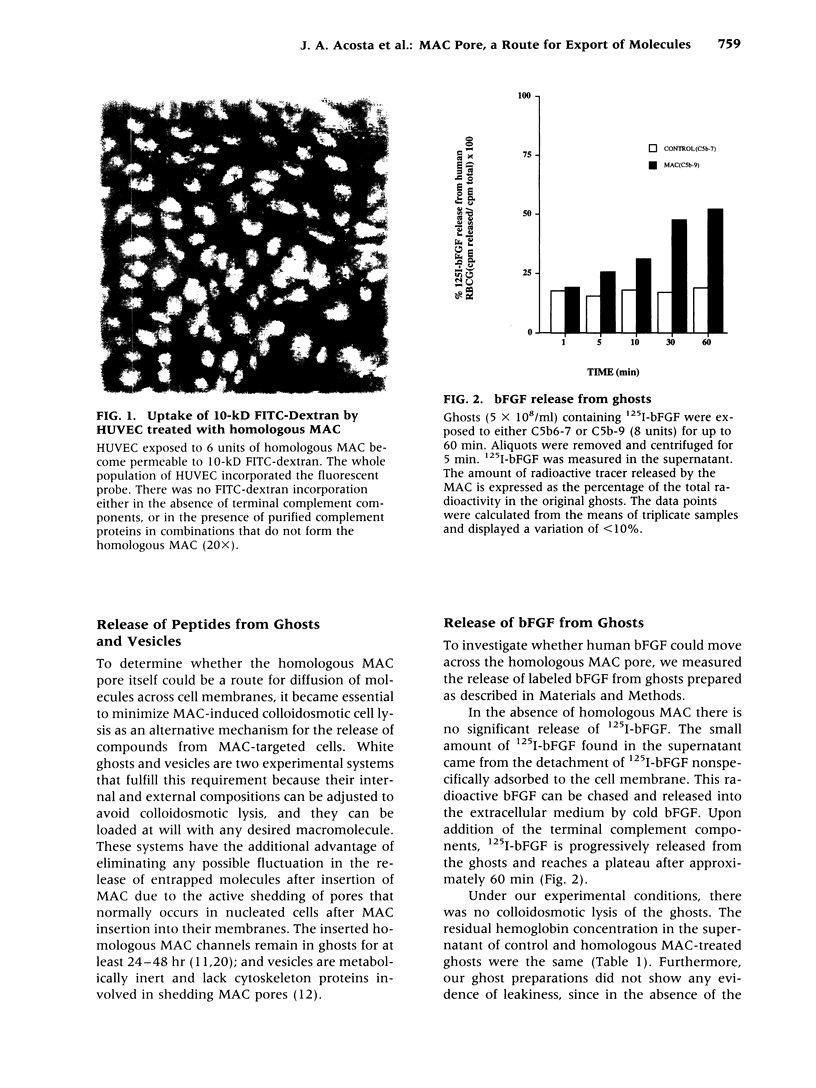

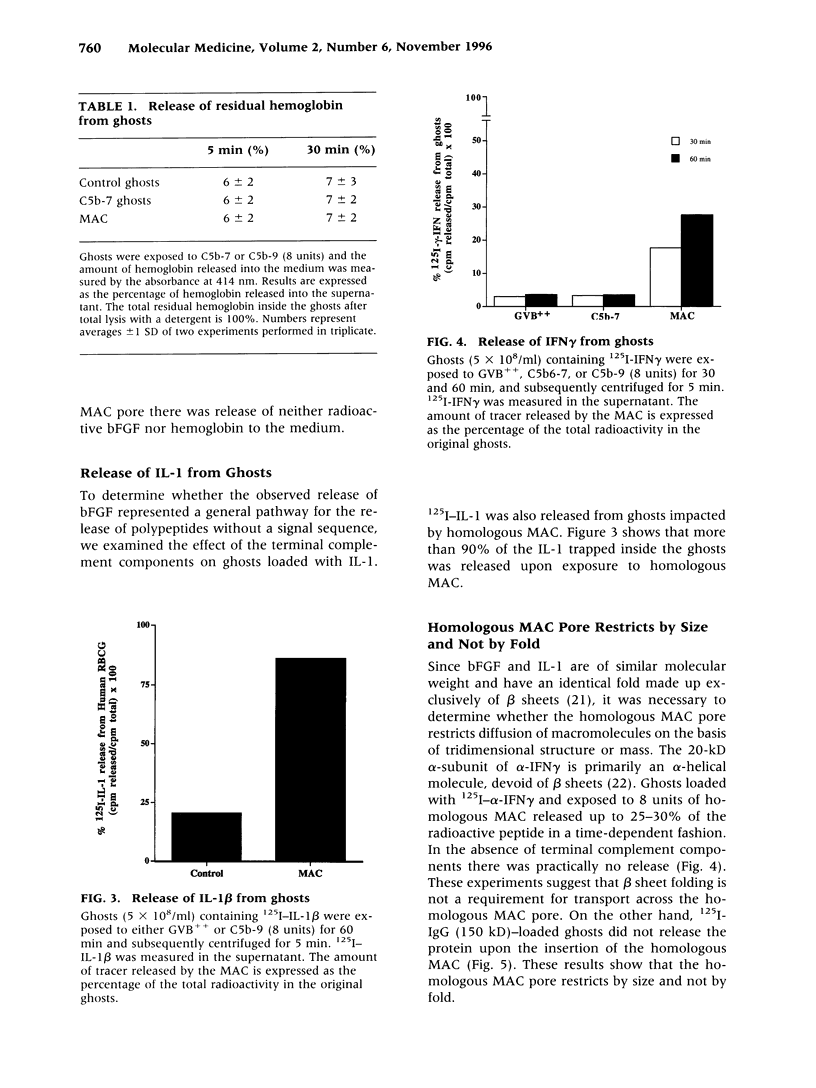

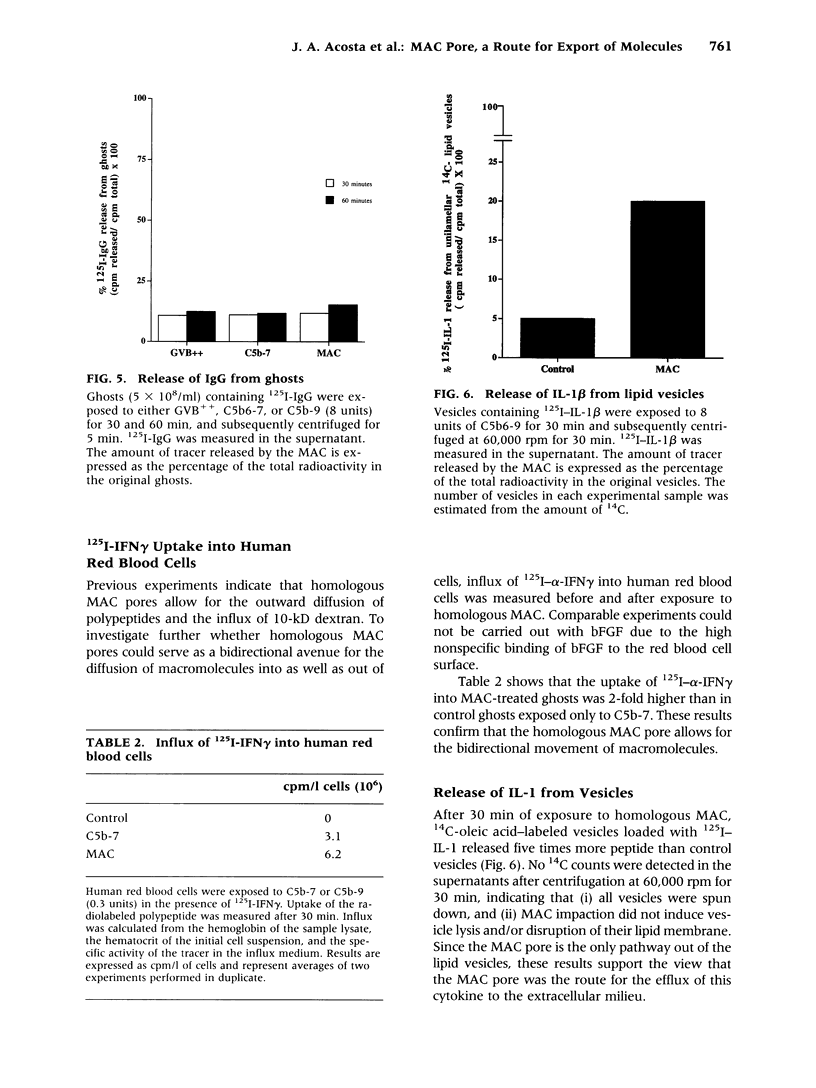

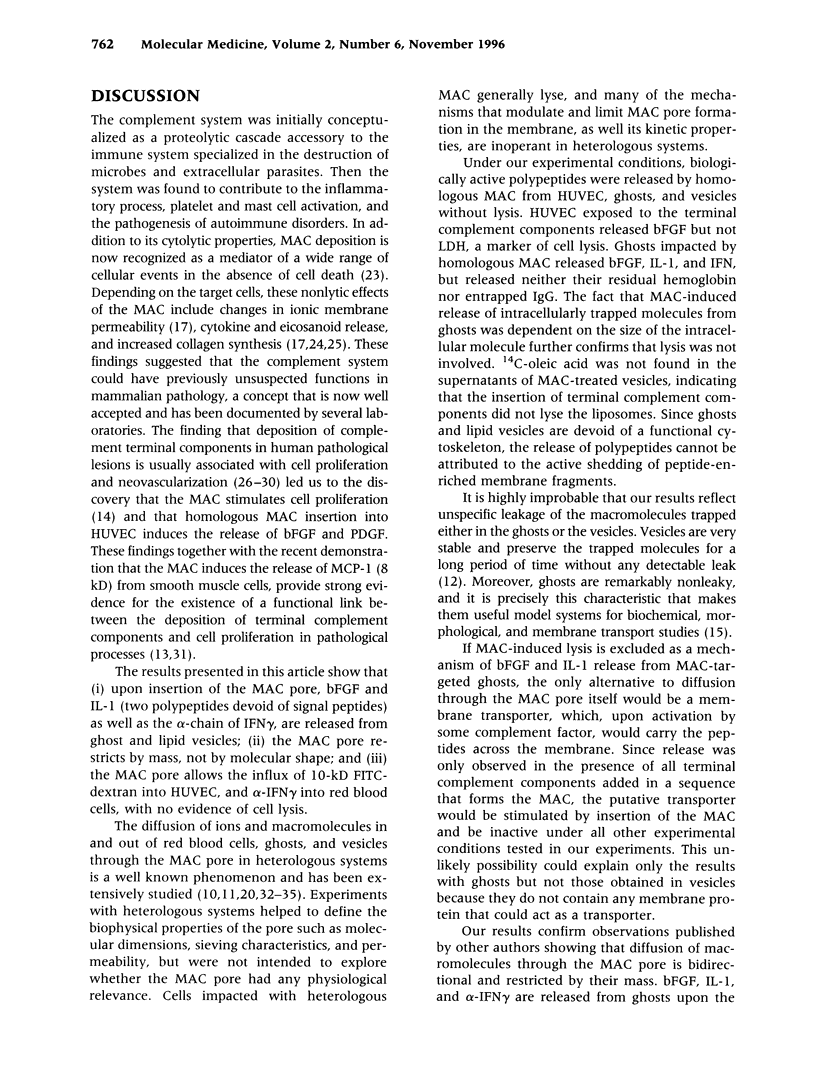

BACKGROUND: We have previously shown that the membrane attack complex (MAC) of complement stimulates cell proliferation and that insertion of homologous MAC into the membranes of endothelial cells results in the release of potent mitogens, including basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF). The mechanism of secretion of bFGF and other polypeptides devoid of signal peptides, such as interleukin 1 (IL-1) is still an open problem in cell biology. We have hypothesized that the homologous MAC pore itself could constitute a transient route for the diffusion of biologically active macromolecules in and out of the target cells. MATERIALS AND METHODS: Human red blood cell ghosts and artificial lipid vesicles were loaded with labeled growth factors, cytokines and IgG, and exposed to homologous MAC. The release of the 125I-macromolecules was followed as a function of time. The incorporation of labeled polypeptides and fluorescent dextran (MW: 10,000) was measured in MAC-impacted human red blood cells and human umbilical endothelial cells (HUVEC), respectively. RESULTS: Homologous MAC insertion into HUVEC resulted in the massive uptake of 10-kD dextran and induced the release of bFGF, in the absence of any measurable lysis. Red blood cell ghosts preloaded with bFGF, IL-1 beta, and the alpha-chain of interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) released the polypeptides upon MAC insertion, but they did not release preloaded IgG. MAC-impacted ghosts took up radioactive IFN-gamma from the extracellular medium. Vesicles loaded with IL-I released the polypeptide when exposed to MAC. CONCLUSIONS: The homologous MAC pore in its nonlytic form allows for the export of cytosolic proteins devoid of signal peptides that are not secreted through the classical endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi exocytotic pathways. Our results suggest that the release, and perhaps the uptake, of biologically active macromolecules through the homologous MAC pore is a novel biological function of the complement system in mammals.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baldwin W. M., 3rd, Pruitt S. K., Brauer R. B., Daha M. R., Sanfilippo F. Complement in organ transplantation. Contributions to inflammation, injury, and rejection. Transplantation. 1995 Mar 27;59(6):797–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzaquen L. R., Nicholson-Weller A., Halperin J. A. Terminal complement proteins C5b-9 release basic fibroblast growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor from endothelial cells. J Exp Med. 1994 Mar 1;179(3):985–992. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhakdi S., Tranum-Jensen J. Complement lysis: a hole is a hole. Immunol Today. 1991 Sep;12(9):318–321. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90007-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerrum P. J. Hemoglobin-depleted human erythrocyte ghosts: characterization of morphology and transport functions. J Membr Biol. 1979 Jun 29;48(1):43–67. doi: 10.1007/BF01869256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney D. F., Koski C. L., Shin M. L. Elimination of terminal complement intermediates from the plasma membrane of nucleated cells: the rate of disappearance differs for cells carrying C5b-7 or C5b-8 or a mixture of C5b-8 with a limited number of C5b-9. J Immunol. 1985 Mar;134(3):1804–1809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra J., Joist J. H., Webster R. O. Loss of 51chromium, lactate dehydrogenase, and 111indium as indicators of endothelial cell injury. Lab Invest. 1987 Nov;57(5):578–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D. N., Barondes S. H. Evidence for export of a muscle lectin from cytosol to extracellular matrix and for a novel secretory mechanism. J Cell Biol. 1990 May;110(5):1681–1691. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.5.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cybulsky A. V., Monge J. C., Papillon J., McTavish A. J. Complement C5b-9 activates cytosolic phospholipase A2 in glomerular epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1995 Nov;269(5 Pt 2):F739–F749. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.269.5.F739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A., Simmons D. L., Hale G., Harrison R. A., Tighe H., Lachmann P. J., Waldmann H. CD59, an LY-6-like protein expressed in human lymphoid cells, regulates the action of the complement membrane attack complex on homologous cells. J Exp Med. 1989 Sep 1;170(3):637–654. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ealick S. E., Cook W. J., Vijay-Kumar S., Carson M., Nagabhushan T. L., Trotta P. P., Bugg C. E. Three-dimensional structure of recombinant human interferon-gamma. Science. 1991 May 3;252(5006):698–702. doi: 10.1126/science.1902591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk R. J., Sisson S. P., Dalmasso A. P., Kim Y., Michael A. F., Vernier R. L. Ultrastructural localization of the membrane attack complex of complement in human renal tissues. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987 Feb;9(2):121–128. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(87)80089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giavedoni E. B., Chow Y. M., Dalmasso A. P. The functional size of the primary complement lesion in resealed erythrocyte membrane ghosts. J Immunol. 1979 Jan;122(1):240–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin J. A., Nicholson-Weller A., Brugnara C., Tosteson D. C. Complement induces a transient increase in membrane permeability in unlysed erythrocytes. J Clin Invest. 1988 Aug;82(2):594–600. doi: 10.1172/JCI113637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin J. A., Taratuska A., Nicholson-Weller A. Terminal complement complex C5b-9 stimulates mitogenesis in 3T3 cells. J Clin Invest. 1993 May;91(5):1974–1978. doi: 10.1172/JCI116418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann P. J. The control of homologous lysis. Immunol Today. 1991 Sep;12(9):312–315. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90005-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liszewski M. K., Farries T. C., Lublin D. M., Rooney I. A., Atkinson J. P. Control of the complement system. Adv Immunol. 1996;61:201–283. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60868-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lublin D. M., Atkinson J. P. Decay-accelerating factor: biochemistry, molecular biology, and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:35–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald R. C., MacDonald R. I., Menco B. P., Takeshita K., Subbarao N. K., Hu L. R. Small-volume extrusion apparatus for preparation of large, unilamellar vesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991 Jan 30;1061(2):297–303. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90295-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinski J. A., Nelsestuen G. L. Membrane permeability to macromolecules mediated by the membrane attack complex. Biochemistry. 1989 Jan 10;28(1):61–70. doi: 10.1021/bi00427a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil P. L., Muthukrishnan L., Warder E., D'Amore P. A. Growth factors are released by mechanically wounded endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1989 Aug;109(2):811–822. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.2.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels D. W., Abramovitz A. S., Hammer C. H., Mayer M. M. Increased ion permeability of planar lipid bilayer membranes after treatment with the C5b-9 cytolytic attack mechanism of complement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976 Aug;73(8):2852–2856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.8.2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan B. P. Complement membrane attack on nucleated cells: resistance, recovery and non-lethal effects. Biochem J. 1989 Nov 15;264(1):1–14. doi: 10.1042/bj2640001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan B. P., Luzio J. P., Campbell A. K. Intracellular Ca2+ and cell injury: a paradoxical role of Ca2+ in complement membrane attack. Cell Calcium. 1986 Dec;7(5-6):399–411. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(86)90042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan B. P. Physiology and pathophysiology of complement: progress and trends. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1995;32(3):265–298. doi: 10.3109/10408369509084686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muesch A., Hartmann E., Rohde K., Rubartelli A., Sitia R., Rapoport T. A. A novel pathway for secretory proteins? Trends Biochem Sci. 1990 Mar;15(3):86–88. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90186-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramm L. E., Mayer M. M. Life-span and size of the trans-membrane channel formed by large doses of complement. J Immunol. 1980 May;124(5):2281–2287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramm L. E., Whitlow M. B., Mayer M. M. Size of the transmembrane channels produced by complement proteins C5b-8. J Immunol. 1982 Sep;129(3):1143–1146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer H., Pratsch L., Fritzsch G., Bhakdi S., Peters R. Complement pore genesis observed in erythrocyte membranes by fluorescence microscopic single-channel recording. Biochem J. 1991 Jun 1;276(Pt 2):395–399. doi: 10.1042/bj2760395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer H., Pratsch L., Tschopp J., Bhakdi S., Peters R. Functional size of complement and perforin pores compared by confocal laser scanning microscopy and fluorescence microphotolysis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991 Mar 18;1063(1):137–146. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90363-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simone C. B., Henkart P. Inhibition of marker influx into complement-treated resealed erythrocyte ghosts by anti-C5. J Immunol. 1982 Mar;128(3):1168–1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims P. J., Lauf P. K. Steady-state analysis of tracer exchange across the C5b-9 complement lesion in a biological membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Nov;75(11):5669–5673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.11.5669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl G. L., Reenstra W. R., Frendl G. Complement-mediated loss of endothelium-dependent relaxation of porcine coronary arteries. Role of the terminal membrane attack complex. Circ Res. 1995 Apr;76(4):575–583. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torzewski J., Oldroyd R., Lachmann P., Fitzsimmons C., Proudfoot D., Bowyer D. Complement-induced release of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 from human smooth muscle cells. A possible initiating event in atherosclerotic lesion formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996 May;16(5):673–677. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.5.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. D., Cousens L. S., Barr P. J., Sprang S. R. Three-dimensional structure of human basic fibroblast growth factor, a structural homolog of interleukin 1 beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Apr 15;88(8):3446–3450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]