Abstract

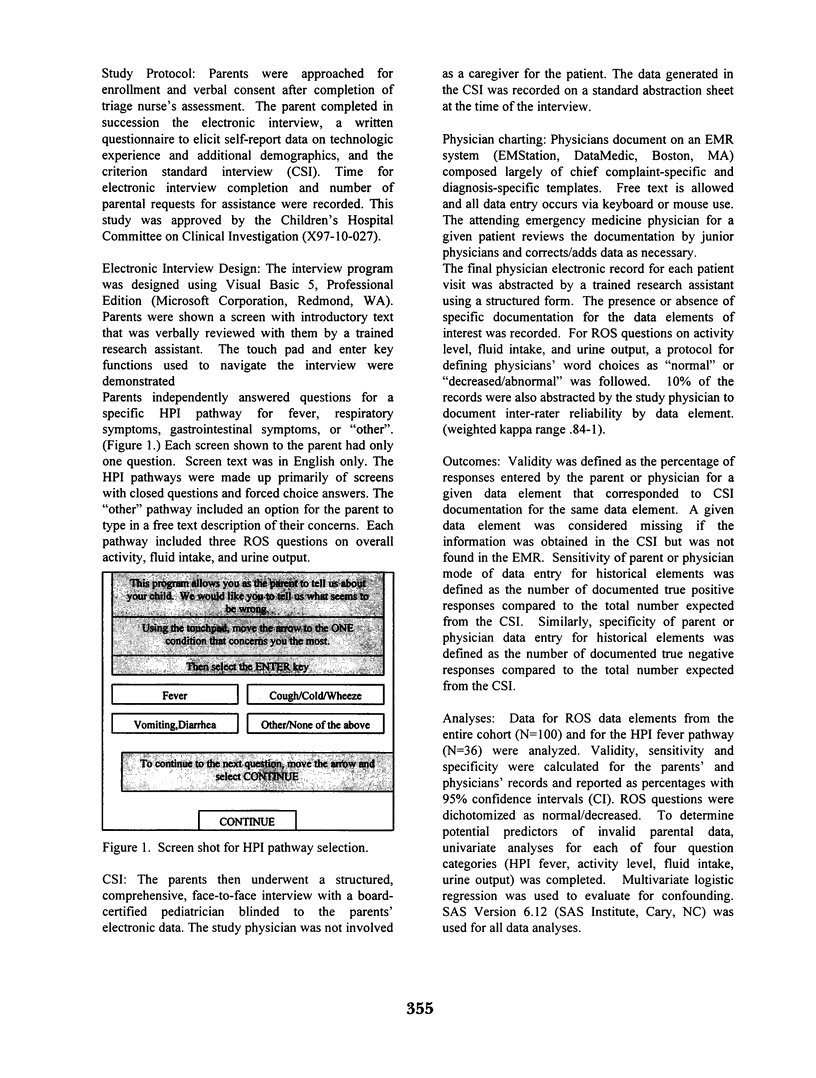

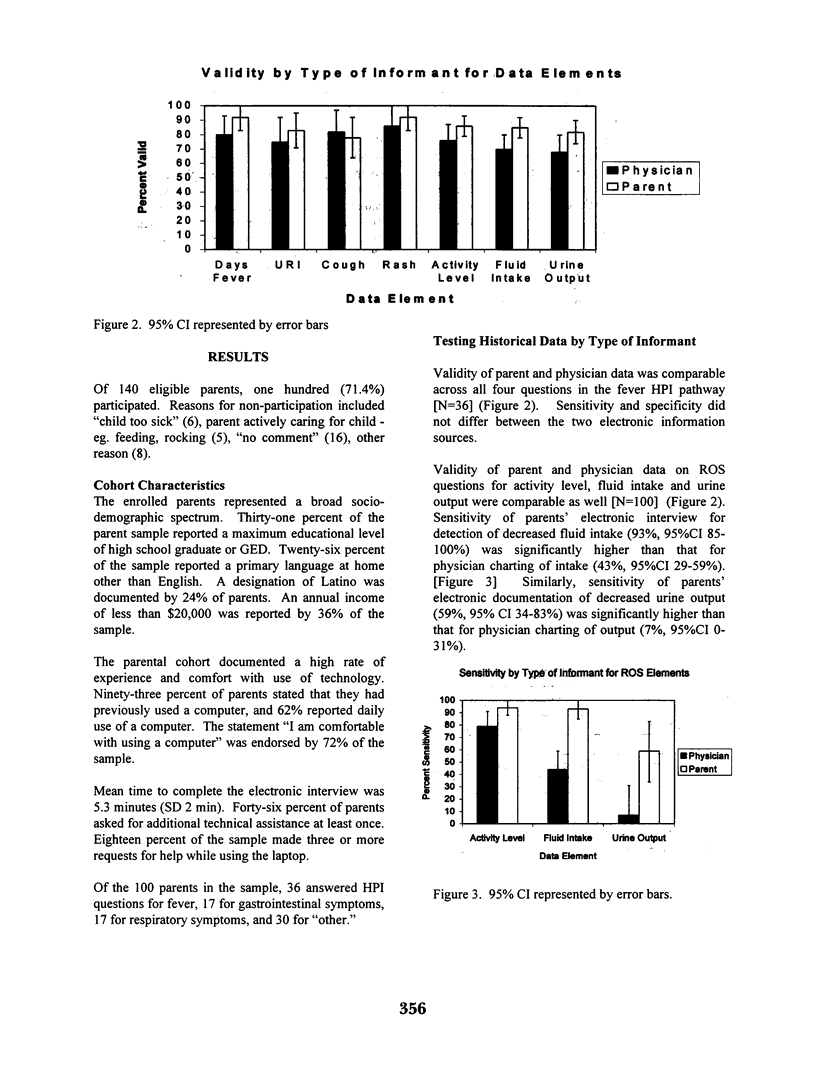

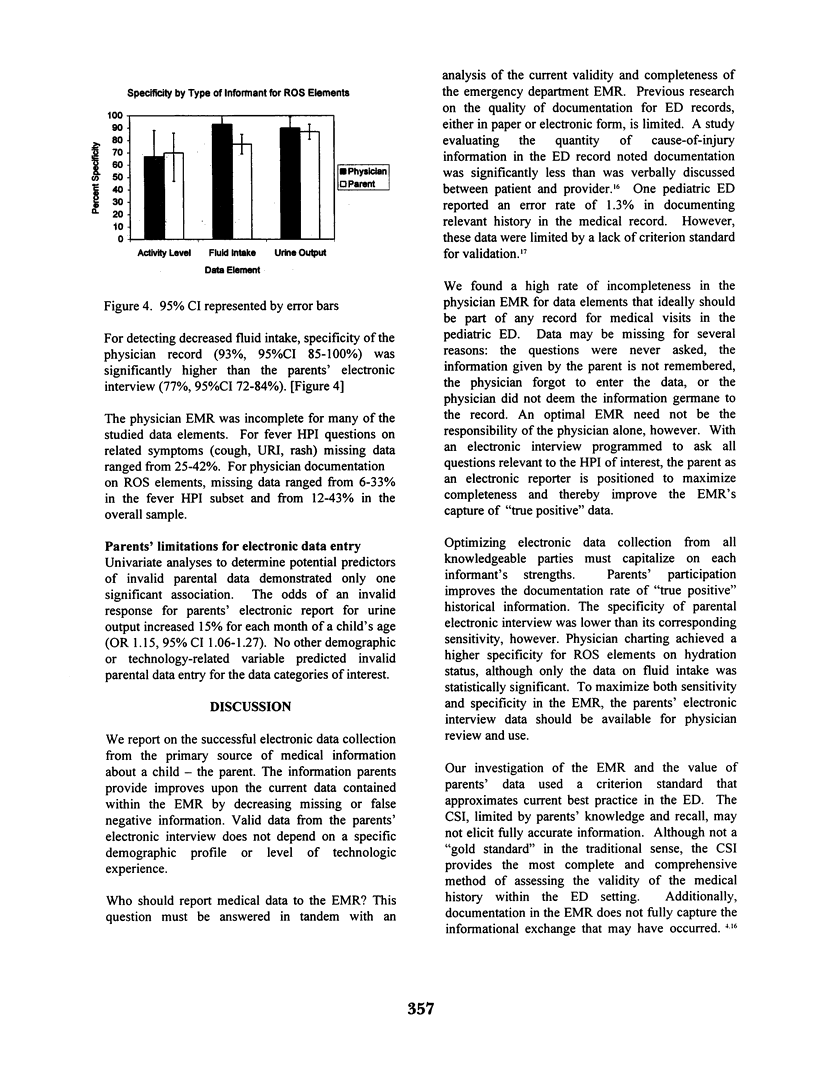

INTRODUCTION: The paper and electronic medical record (EMR) have evolved with little scientific inquiry into what effect the informant (clinician or patient) has on the validity of the recorded information. We have previously reported on an electronic interview program that facilitated parents' direct reporting of past medical history data. We sought to define additional data elements that parents could report electronically and to compare parents' electronically entered data to that charted by physicians using the current EMR system. METHODS: A convenience sample of parents was recruited to enter data on history of present illness (HPI) and review of systems (ROS) elements using an electronic interview. Data from the electronic parental interview and information abstracted from the physician EMR were compared to data derived from a face-to-face criterion standard interview. Validity, sensitivity and specificity of each mode of data entry were calculated. RESULTS: 100 of 140 eligible parents (71.4%) participated. Validity of information from the electronic interview was comparable to that charted by emergency physicians for HPI regarding fever and ROS questions. Sensitivity of parents' electronic interview was superior to physicians' charting for ROS elements specific to hydration status. CONCLUSIONS: Improved sensitivity for detection of historical risk factors for illness can be achieved by augmenting the pediatric EMR with a section for direct parental direct data input. Direct parental data input to the EMR should be considered to improve the quality of documentation for medical histories.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Garrett L. E., Jr, Hammond W. E., Stead W. W. The effects of computerized medical records on provider efficiency and quality of care. Methods Inf Med. 1986 Jul;25(3):151–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasley S. A comparison of computer-based and personal interviews for the gynecologic history update. Obstet Gynecol. 1995 Apr;85(4):494–498. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00012-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan W. R., Wagner M. M. Accuracy of data in computer-based patient records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997 Sep-Oct;4(5):342–355. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1997.0040342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt D. L., Haynes R. B., Hayward R. S., Pim M. A., Horsman J. Automated direct-from-patient information collection for evidence-based diabetes care. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1997:81–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhaveri R. C., Lavorgna L., Macabuhay M., Evans H. E., Schaeffer H. A. Analysis of the medical records in a pediatric emergency room. J Natl Med Assoc. 1979 Jun;71(6):569–571. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke S. E., Kowaloff H. B., Hoff R. G., Safran C., Popovsky M. A., Cotton D. J., Finkelstein D. M., Page P. L., Slack W. V. Computer-based interview for screening blood donors for risk of HIV transmission. JAMA. 1992 Sep 9;268(10):1301–1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutner R. E., Roizen M. F., Stocking C. B., Thisted R. A., Kim S., Duke P. C., Pompei P., Cassel C. K. The automated interview versus the personal interview. Do patient responses to preoperative health questions differ? Anesthesiology. 1991 Sep;75(3):394–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons T. F., Payne B. C. The relationship of physicians' medical recording performance to their medical care performance. Med Care. 1974 May;12(5):463–469. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197405000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J. L., Haring O. M., Wortman P. M., Watson R. A., Goetz J. P. Medical information systems: assessing impact in the areas of hypertension, obesity and renal disease. Med Care. 1982 Jan;20(1):63–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198201000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruland C. M. Improving patient outcomes by including patient preferences in nursing care. Proc AMIA Symp. 1998:448–452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz R. J., Boisoneau D., Jacobs L. M. The quantity of cause-of-injury information documented on the medical record: an appeal for injury prevention. Acad Emerg Med. 1995 Feb;2(2):98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teich J. M. Information systems support for emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 1998 Mar;31(3):304–307. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman Z. E., Starfield B., Hochreiter C., Kovasznay B. Validating the content of pediatric outpatient medical records by means of tape-recording doctor-patient encounters. Pediatrics. 1975 Sep;56(3):407–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]