Abstract

Background

Dystrophin has a key role in striated muscles mechanotransduction of physical forces. Although cytoskeletal elements play a major role in the mechanotransduction of pressure and flow in vascular cells, the role of dystrophin in vascular functions has not yet been investigated. Thus we studied endothelial and muscular responses of arteries isolated from mice lacking dystrophin (mdx).

Methods and results

Carotid and mesenteric resistance arteries (120μm diameter) were isolated and mounted in vitro in an arteriograph to control intraluminal pressure and flow. Blood pressure was not affected by the absence of dystrophin. Pressure (myogenic)-, phenylephrine- and KCl-induced tone were unchanged. Flow (shear stress) -induced dilation in arteries isolated from mdx mice was decreased by 50 to 60%, whereas dilation to acetylcholine or sodium nitroprusside were unaffected. L-NAME-sensitive flow-dilation was also decreased in arteries from mdx mice. Thus the absence of dystrophin was associated to a defect in signal transduction of shear stress. Dystrophin was present in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells, as shown by immunolocalization and localized at the level of the plasma membrane, as seen by confocal microscopy of perfused isolated arteries.

Discussion

This is the first functional study of arteries lacking the gene for dystrophin. Vascular reactivity was normal with the exception of flow-induced dilation. Thus dystrophin could play a specific role in shear stress-mechanotransduction in arterial endothelial cells. Organs damages in diseases such as Duchenne’s dystrophy might be aggravated by such a defectuous arterial response to flow.

Short abstract

Dystrophin plays an active role in the transduction of mechanical forces in striated muscle. We showed that the absence of dystrophin altered specifically the mechanotransduction of shear stress due to flow by the endothelium of arteries isolated from mice lacking the gene for dystrophin (mdx), whereas other forms of vascular tone, dilators or constrictors, were unaffected.

Thus dystrophin plays a specific role in shear stress-mechanotransduction in arterial endothelial cells. Finally, organs damages in diseases such as Duchenne’s dystrophy might be aggravated by defectuous arterial responses to changes in blood flow.

Keywords: Acetylcholine, pharmacology, Analysis of Variance, Animals, Blood Flow Velocity, Blood Pressure, Calcium, pharmacology, Carotid Arteries, drug effects, metabolism, Dystrophin, analysis, deficiency, genetics, Endothelium, Vascular, drug effects, physiology, Humans, Mesenteric Arteries, drug effects, metabolism, Mice, Mice, Inbred mdx, Microscopy, Confocal, Muscle, Skeletal, blood supply, drug effects, physiology, Nitroprusside, pharmacology, Phenylephrine, pharmacology, Potassium Chloride, pharmacology, Signal Transduction, Vasodilation, drug effects

Introduction

Flow (shear stress)-induced dilation is a fundamental mechanism for the control of vascular tone. Shear stress is the main physiological stimulus for vascular endothelial cells, triggering the release of vasoactive agents 1–7. Its role in the control of blood flow supply to organs is fundamental7. Flow-induced dilation allows the adaptation of feeding arteries to the metabolic needs of each organ7,8. Mechanotransduction of shear stress involves the extracellular matrix and cell structure proteins8–18. Depolymerization of F-actin into G-actin is rapid upon shear stress stimulation12,19 and the absence of the gene encoding for the intermediate filament vimentin greatly lowers the vascular response to shear stress20. Dystrophin is a main cytoskeletal structure protein21–28 involved in skeletal and cardiac muscle cells mechanotransduction21,28–30. Although dystrophin is present in vascular smooth muscle cells25, 31–33 no functional study in blood vessels has been performed and especially in response to mechanical stimuli such as pressure and flow, the main effectors of vascular tone and blood supply1–8. The possibility that a specific vascular malfunction, such as a decrease in local blood flow supply to end-organs, has never been investigated in dystrophin-related diseases such as the Duchenne’s dystrophy, although it might, at least, accelerate damages to tissues and especially damages to cardiac and skeletal muscles. Thus, we tested the hypothesis that vascular mechanotransdution of the 2 main physical forces to which vessels are continuously submitted (pressure and flow) could involve dystrophin and that its absence might induce vascular disorders. Indeed, dystrophin has a key position between membrane structure proteins and the actin cytoskeleton, although never described as precisely in vascular cells, and disruption of the actin filaments has been shown to specifically affect vascular responses to flow12. We used carotid and mesenteric resistance arteries which represent the 2 main types of arteries, i.e., large conductance (or compliance) arteries using their elastic properties to damp the energy produced by the ejection of blood by the heart at each systole and resistance arteries using their muscular tone and endothelial relaxing capacity to regulate blood flow supply to organs.

METHODS

Isolated arteries

Mdx mice and their control (C57-Bl10) were obtained from Iffa-Credo (L’Arbresle, France). They were anesthetized for blood pressure measurement through a catheter in the left carotid artery20. Then, right carotid and mesenteric arteries were isolated and cannulated at both ends in a video monitored perfusion system44 (LSI, Burlington, VT) as previously described20,34,45,46. Briefly, arteries were bathed in a physiological salt solution (pH 7.4, pO2 160 mmHg, pCO2 37 mmHg). Pressure was controlled by a servo-perfusion system and flow generated by a peristaltic pump. Diameter changes were measured when intraluminal pressure was increased from 10 to 125 mmHg. Pressure we then set at 75 mmHg and flow increased by steps. At the end of each experiment arteries were perfused and superfused with a Ca2+-free physiological salt solution containing EGTA (2 mM) and sodium nitroprusside (10 μM) and pressure steps were repeated in order to determine the arteries passive diameter20,34,45,46. Contractions to phenylephrine (1nM to 10μM), KCl (80 mM) and calcium (0.1 to 1 mM in a calcium-free medium + 80 mM KCl) were separately tested. Dilation to acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside were tested after preconstriction of the arteries with phenylephrine (50% of the maximal contraction)20,34.

Histomorphometrical analysis

Histomorphometry of the arteries was performed as previously described on segments of arteries previously mounted in the arteriograph as described above. Pressure was set at 75 mmHg and vessels were fixed in 10% formaldehyde in saline solution (30 min) and sectioned (10μm thick sections). Morphometric analysis was performed with an automated image processor45–47.

Immunolocalization of dystrophin and in situ confocal microscopy

Segments of arteries mounted in embedding medium (Miles, Inc., Elkhart, USA), frozen in isopentane45,46. Immunostaining was then performed on transverse cross section (5 μm thin) incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-dystrophin antibodies (anti dys2, 1:20, Novacastra) and then incubated for 30 min at 37°C with anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated to peroxydase (Amersham). Samples were mesenteric resistance or carotid arteries, gracilis muscle and heart from mdx and control mice, as well as human internal mammary and mesenteric arteries. Positive staining was visualized as a brown-orange staining, using video microscopy45,46.

In another group of experiments immunostaining of dystrophin was performed in isolated mesenteric arteries from control and mdx mice mounted in an arteriograph under a pressure of 75 mm Hg and a flow of 50 μl/min, so that vascular cells were left in physiological conditions. Cell membranes were permeabilized with β-escin (90 mg/ml, 10 min) to allow antibodies to reach dystrophin. A secondary antibody (anti IgG), bound to streptavidine and Texas-red was used to labeled anti-dystrophin antibodies45,46. Fluorescence staining was visualized using an Axiophot inverted microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an Odyssey XL confocal scanning system (Noran Instruments, Midleton, WI, USA) allowing to visualized staining of endothelial cells in the luminal side of the perfused artery.

Finally, we also used human mammary and epiploic arteries to immunolocalized, as described above, dystrophin in endothelial and smooth muscle cells. These human arteries were isolared from excess material normally discared after surgery.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as means ± standard error (s.e.mean). EC50 or IC50 (concentration of agonist required to induce half the maximum response) and Emax (maximal response) were calculated for each artery20. Significance of the differences between groups was determined by analysis of variance (one or two factor ANOVA, or ANOVA for consecutive measurements, when appropriate). Means were compared by paired t test or by Bonferroni’s test for multigroup comparisons. P values less than 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

Animals

Body weight was not affected by the absence of dystrophin (33±3 vs 35±3g, mdx vs control mice, n=12 per group). Similarly, blood pressure was normal in mdx mice (mean arterial pressure: 86±5 mmHg in mdx vs 88±6 mmHg in controls mice, n=12 per group).

Isolated arteries

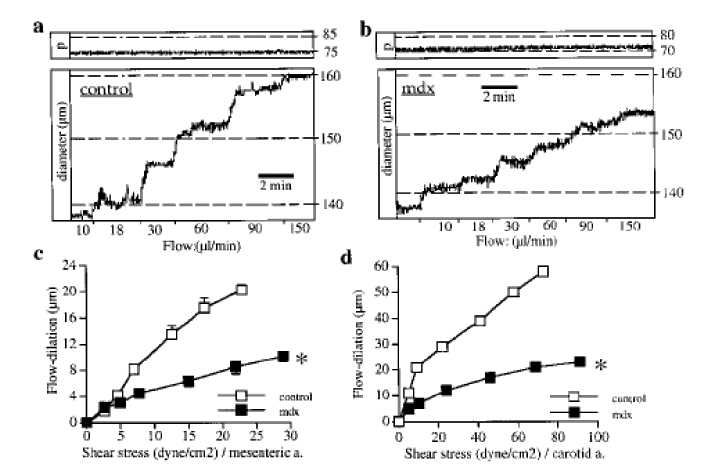

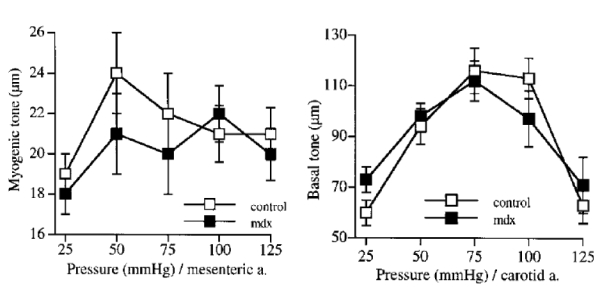

In isolated carotid and mesenteric resistance arteries under a physiological level of intraluminal pressure a basal (myogenic) tone develops, which was antagonized by flow (shear stress)-induced dilation. Thus, increasing flow by steps induced a progressive dilation (figure 1). In both carotid and mesenteric resistance arteries flow (shear stress)-induced dilation was strongly attenuated in mdx mice (fig. 1). Pressure (tensile stress)-induced tone (myogenic in resistance arteries) was unaffected by the absence of dystrophin (mdx mice) in both type of vessels (figure 2). Other endothelium dependent (acetylcholine) or independent (sodium nitroprusside) forms of dilation were not modified in mdx mice, in both carotid and resistance arteries (table 1). Similarly, contractions to calcium, KCl or phenylephrine (table 1), in addition to basal tone due to pressure (figure 2) were not affected by the lack of dystrophin.

Figure 1.

Vascular response to flow. Typical recordings showing changes in diameter in response to step increases in flow in mesenteric resistance arteries isolated from control (a) or mdx mice (b) and mounted in an arteriograph, under a pressure (P, top recordings) of 75 mmHg. Flow-induced dilation obtained in mesenteric (c) and carotid (d) arteries was strongly attenuated in mdx mice. n=14 per group.

*P <0.001; two-factor ANOVA, control vs mdx.

Figure 2.

Changes in diameter in response to step increases in pressure in mesenteric resistance (myogenic tone, upper panel) and carotid (basal tone, lower panel) arteries isolated from mdx and control mice. n=14 per group.

No significant difference; two-factor ANOVA, control vs mdx.

Table 1.

Pharmacological profile of mice arteries. Contraction to phenylephrine (PE), KCl (80 mM) and calcium (Ca2+) and dilation to acetylcholine (ACh) and sodium nitroprusside (SNP) were obtained in mesenteric resistance arteries and carotid arteries isolated from mice lacking the gene for dystrophin (mdx) and their control.

| Mesenteric arteries: | mdx | control | ||

| SNP: | IC50 | 43±7 | 32±8 | nM |

| Imax | 100±1 | 100±1 | % | |

| ACh: | IC50 | 78±9 | 87±8 | nM |

| Imax | 99±2 | 96±3 | % | |

| PE: | EC50 | 28±4 | 40±5 | nM |

| Emax | 86±8 | 93±8 | μm | |

| Ca2+ | EC50 | 0.2±0.04 | 0.16±0.03 | mM |

| Emax | 105±11 | 128±20 | μm | |

| Carotid arteries: | mdx | control | ||

| SNP: | IC50 | 61±17 | 90±30 | nM |

| Imax | 78±5 | 85±6 | % | |

| ACh: | IC50 | 621±134 | 585±78 | nM |

| Imax | 68±5 | 74±3 | % | |

| PE: | EC50 | 497±106 | 406±82 | nM |

| Emax | 85±6 | 96±6 | μm | |

| Ca2+ | EC50 | 0.34±0.06 | 0.31±0.07 | mM |

| Emax | 74±7 | 72±6 | μm | |

| Contraction to KCl: | mdx | control | ||

| Carotid arteries: | 93±8 | 100±12 | μm | |

| Mesenteric arteries: | 112±8 | 118±6 | μm | |

EC50 and IC50 represent the concentration necessary to reach 50% of the maximal effect; Emax and Imax give the maximal effect of the drug (n=8 per group).

No significant difference between mdx and control mice was found.

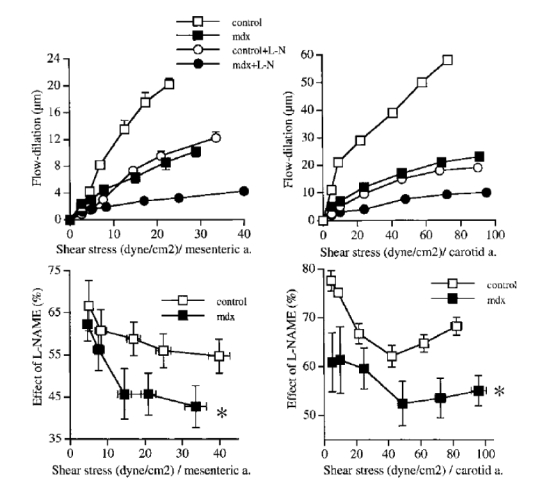

Blockade of NO synthesis by L-NAME reduced flow-induced dilation in both types of arteries (figure 3, top). L-NAME was less efficient in arteries from mdx mice stimulated by flow than in control mice (figure 3, bottom graphs). Direct stimulation of cGMP-dependent dilation (endothelium-independent) with sodium nitroprusside was unaffected in mdx mice (table 1).

Figure 3.

Effect of the inhibition of NO synthesis with L-NAME (0.1 mM) on flow-induced dilation (upper panel) in mesenteric resistance (left) and carotid (right) arteries isolated from mdx and control mice. In the lower panel, the inhibitory effect of L-NAME is shown as a percentage of inhibition of flow-induced dilation. (n=9 to 14 per group).

*P <0.01; two-factor ANOVA, control vs mdx.

Angiotensin II or endothelin-1 receptors inhibition, did not affect flow-induced dilation in arteries from mdx mice (n=6 per group, data not shown).

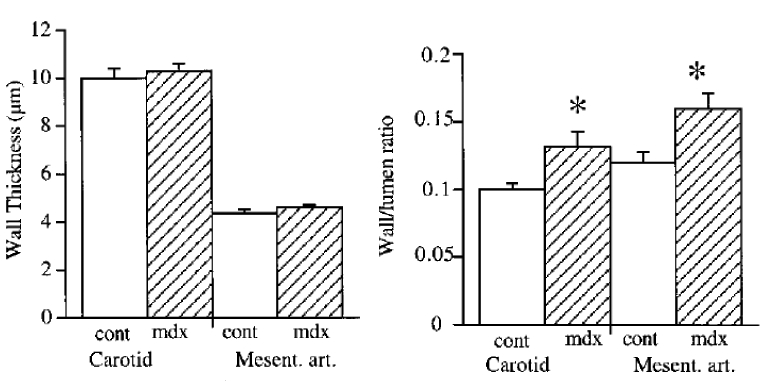

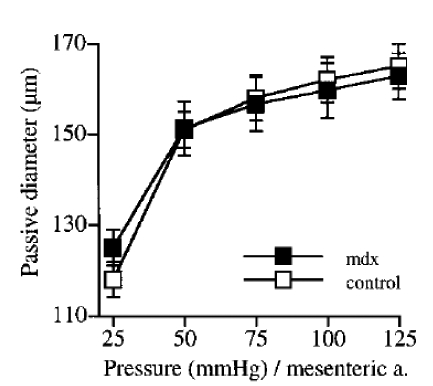

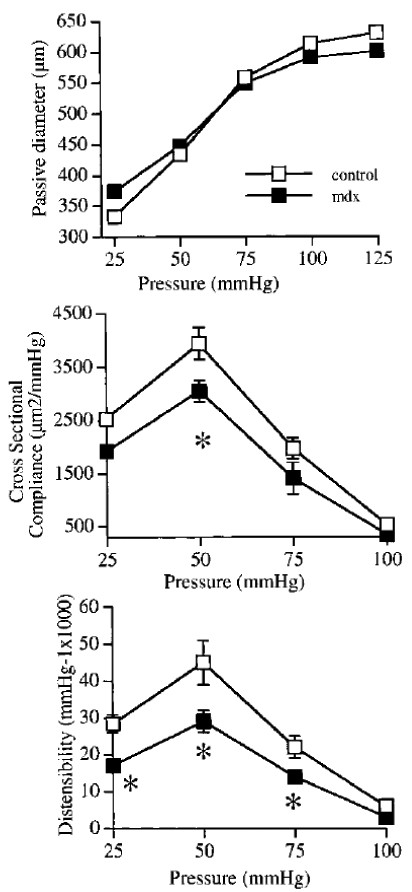

Histomorphometry and passive properties of the vascular wall

Although no significant change in arterial wall thickness (figure 4) or passive diameter (figure 5, mesenteric arteries and figure 6, carotid arteries) was found, arterial wall structure was affected by the absence of dystrophin, as visualized by a larger wall to lumen ratio (figure 4) and a lower compliance and distensibility of the carotid artery (figure 6).

Figure 4.

Arterial wall thickness (left panel) and wall to lumen ratio (right panel) in mesenteric resistance and carotid arteries isolated from mdx and control mice. (n=6 to 8 per group).

P <0.01; two-factor ANOVA, control vs mdx.

Figure 5.

Passive diameter determined in response to increases pressure levels in mesenteric resistance arteries isolated from mdx and control mice. (n=10 and 14, respectively). No significant difference; two-factor ANOVA, control vs mdx.

Figure 6.

Passive arterial diameter (upper panel), cross sectional compliance (middle panel) and distensibility (lower panel) in carotid arteries isolated from mdx and control mice. (n=8 to 10 per group). *P <0.01; one-way ANOVA, control vs mdx.

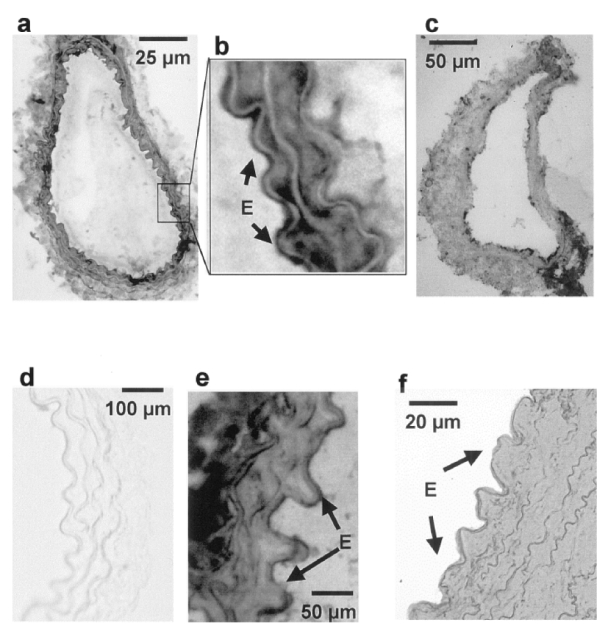

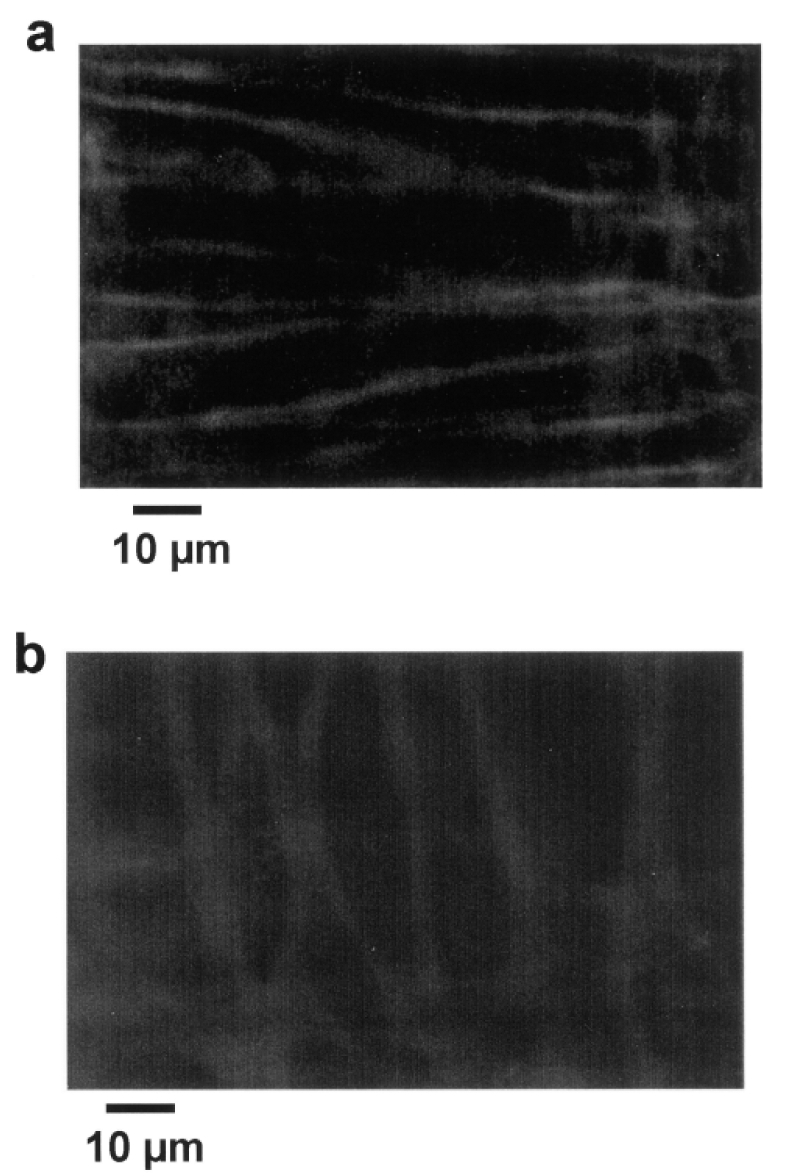

Immunolocalization of dystrophin

The protein dystrophin was present in both vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells in control mice (absent in mdx mice), but also in human internal mammary and mesenteric resistance arteries (figure 7). Confocal scanning of an isolated arteries, mounted in an arteriograph in order to maintain physiological levels of pressure and flow in the lumen of the arteries, shows that dystrophin is present in both endothelial and smooth muscle cells. In these cells, dystrophin was located at the level of the plasma membrane (figure 8).

Figure 7.

Immunolocalization of dystrophin in different type of arteries (peroxydase staining: orange to brown when positive). Dystrophin was present in the tunica media and in the endothelium of mesenteric (a,b) and carotid arteries (e). No staining in mdx mice (carotid artery: d). A similar pattern was found in human mesenteric (c) and mammary arteries (f).

Figure 8.

Immunolocalization of dystrophin (Texas-Red staining) in perfused resistance arteries mounted in an arteriograph (pressure = 75 mmHg and flow = 30 μl/min) shows the in situ localization of dystrophin in smooth muscle (a) and endothelial cells (b). Confocal scanning was performed at a high speed (30 images per second) due to the movements of the vessel wall during perfusion under pressure.

Discussion

This is the first study of vascular functions in relation to the genetic deficiency in dystrophin. Interestingly, in mice lacking the gene for dystrophin, vascular reactivity (endothelial and muscular) was normal, with the exception of flow (shear stress)-induced dilation which was strongly attenuated.

Although dystrophin has been clearly shown to play a key role in force mechanotransduction in striated muscles, its possible role in the mechanotransduction of pressure and flow has never been investigated. Flow and pressure are 2 of the main factors involved in the control of blood vessels tone and blood flow supply and understanding their transduction pathway(s) is fundamental. Surprisingly, in both isolated carotid and mesenteric resistance arteries pressure (tensile stress)-induced tone (myogenic in resistance arteries) was unaffected by the absence of dystrophin, whereas flow (shear stress)-induced dilation was strongly attenuated in mdx mice. Thus only mechanotransduction of shear stress at the surface of endothelial cells, and not that to pressure exerted on the whole vessel wall, was attenuated. Furthermore, in this mice model with a strong attenuation of flow-induced dilation, blood pressure was normal. This and our previous observations in mice lacking the gene encoding for vimentin20 and in rats rendered hypertensive with a chronic infusion of endothelin34 strengthens the hypothesis that flow-dilation has a key role in the control of local blood flow but is not necessarily and/or directly related to the basal level of systemic blood pressure.

Flow-dilation was specifically attenuated in mdx mice. Other endothelium-dependent (acetylcholine) and independent (sodium nitroprusside) dilation were not modified in mdx mice. Similarly, contraction to calcium, KCl or phenylephrine, in addition to myogenic tone due to pressure were not affected by the lack of dystrophin, showing that no endothelium dysfunction and no defect in smooth muscle contractility or vasorelaxant properties could be involved in the reduction in dilation to shear stress found in arteries from mdx mice.

Although no significant change in arterial wall thickness or passive diameter was found, arterial wall structure was affected by the absence of dystrophin, as visualized by a larger wall to lumen ratio and a lesser compliance and distensibility (figure 2). Nevertheless, these changes cannot explain a change only in endothelial response to flow, without affecting other forms of tone. Indeed, in both mdx and control mice arterial tone before inducing flow-dilation was similar.

Nitric oxide (NO) is major relaxing agent released by the endothelium after flow stimulation5,7,35–38 and the blockade of its synthesis was less efficient in arteries from mdx mice stimulated by flow, whereas direct stimulation of cGMP-dependent dilation with sodium nitroprusside was unaffected in mdx mice. Thus arteries from mdx mice are less able to produce NO in response to shear stress. In addition, arteries from mdx mice did not produce more endothelium-derived vasoconstrictor agents when stimulated by flow, as angiotensin II or endothelin-1 receptors inhibition did not affect flow-induced dilation in arteries from mdx mice. Thus the lack of dystrophin caused a specific defect in the transduction of shear stress into a dilation through the NO-cGMP pathway in endothelial cells being able to normally dilate to other relaxing stimuli. This attenuation in flow-induced dilation might lead to a lesser adaptation to increases in blood flow in organs when a metabolic need requires a higher blood flow supply. In addition, flow (shear stress at the surface of the endothelial cells) being a major stimulus for vascular cells growth and angiogenesis8,38–40, a defect in flow-mechanotransduction due to the absence of dystrophin could be deleterious for the angiogenic process and consequently blood flow supply to organs might be affected when an increase in blood flow is required in situations such as exercise. In support of this statement, skeletal muscle contraction induces a NOS-I-dependent arteriolar dilation which is decreased in mdx mice. This lower dilation has been attributed to a lower capacity of the skeletal muscle to produce NO41 but in view of the present study we can also postulate that the increase in blood flow required for the contraction might not be high enough in mdx mice, leading to a lesser NO production in blood vessels as well. Also in support of our hypothesis the occurrence of ischemia has been shown in skeletal and cardiac muscles of dystrophin deficient patients42,43.

Finally, the protein dystrophin was present in both vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells in control mice (absent in mdx mice) and also in human internal mammary and mesenteric resistance arteries. This location is in agreement with the studies performed in skeletal and cardiac muscle cells29 and strengthens the possibility that dystrophin, in vascular endothelial cells plays a major role in mechanotransduction. Flow-mechanotransduction also involves integrins48. Although it is tempting to link the two proteins in the same pathway, such a possibility requires further investigations. In addition, integrins blockade with RGD peptides may suppress totally flow-induced dilation48, whereas the absence of dystrophin in mdx mice decreased the response to 40–50 % of that in control mice. This could reflect an adaptation of the endothelial cells to the chronic absence of dystrophin and other proteins such as dystrophin-related proteins could be involved in flow-mechanotransduction in mdx mice. Finally, the transduction pathway beyond dystrophin leading to the activation of NO synthesis, and especially the type of kinases involved, also remains to be elucidated

In conclusion we found that dystrophin plays a key role in the mechanotransduction of shear stress by the vascular endothelium in both large and resistance arteries. The present findings supports the concept that some elements of the cytoskeleton, with a central role for dystrophin, may specifically transduce the signal from shear stress to the enzymatic dilator machinery in vascular endothelial cells. This observation might be of importance to better understand the development and possibly to improve the treatment of dystrophin-related diseases.

Acknowledgments

This was supported in part by a grant from the France-Myopathies association (AFM: Association France-Myopathies), Paris, France.

Laurent Loufrani is a fellow of the Foundation for Medical Research (Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale), Paris, France.

Abbreviations

- COX

Cyclooxygenase

- NO

Nitric oxide

- L-NAME, 10 μM

NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester

- EGTA

Ethylenbis-(oxyethylenenitrolo) tetra-acetic acid

- mdx

dystrophin-deficient mice

References

- 1.Bevan JA, Laher I. Pressure and flow-dependent vascular tone. FASEB J. 1991;5:2267–2273. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.9.1860618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osol G. Myogenic properties of blood vessels in vitro. In: Bevan JA, Halpern W, Mulvany MJ, editors. The resistance vasculature. Humana Press; Totowa, New Jersey: 1991. pp. 143–157. [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Angelo G, Meininger GA. Transduction mechanisms involved in the regulation of myogenic tone activity. Hypertension. 1994;23:1096–1105. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.6.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson PC. The myogenic response. In: Bevan JA, Halpern W, Mulvany MJ, editors. The resistance vasculature. Humana Press; Totowa, New Jersey: 1991. pp. 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bevan JA, Henrion D. Pharmacological implications of the influence of intraluminal flow on smooth muscle tone. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1994;34:173–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.34.040194.001133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Segal SS. Cell-to-cell communication coordinates blood flow control. Hypertension. 1994;23:1113–1120. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.6.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smiesko V, Johnson PC. The arterial lumen is controlled by flow-related shear stress. News Physiol Sci. 1993;8:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies PF. Flow-mediated endothelial mechanotransduction. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:519–559. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osol G. Mechanotransduction by vascular smooth muscle. J Vasc Res. 1995;32:275–292. doi: 10.1159/000159102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies PF, Tripathi SC. Mechanical stress mechanisms and the cell. An endothelial paradigm Circ Res. 1993;72:239–245. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malek AM, Izumo S. Molecular aspect of signal transductionof shear stress in the endothelial cell. J Hypertens. 1993;12:989–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutcheson IR, Griffith TM. Mechanotransduction through the endothelial cytoskeleton: mediation of flow- but not agonist-induced EDRF release. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:720–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15459.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morita T, Kurihara K, Maemura M, Yoshizumi M, Yazaki Y. Disruption of cytoskeletal structures mediates shear stress-induced endothelin-1 gene expression in cultured porcine aortic endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1706–1712. doi: 10.1172/JCI116757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girard PR, Nerem RM. Shear stress modulates endothelial cell morphology and F-actin organization through the regulation of focal adhesion-associated proteins. J Cell Physiol. 1995;163:179–193. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041630121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis MJ, Hill MA. Signaling mechanisms underlying the vascular myogenic response. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:387–425. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banes AJ, Tsuzaki J, Yamamoto T, Fischer B, Brigman T, Brown T, Miller M. Mechanoreception at the cellular level: the detection, interpretation and diversity of responses to mechanical signals. Biochem Cell Biol. 1995;73:349–365. doi: 10.1139/o95-043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welling LW, Zupka MY, Welling DJ. Mechanical properties of basement membrane. News Physiol Sci. 1995;10:30–35. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oike M, Schwartz G, Sehrer J, Jost M, Gerke V, Weber K, Droogmans G, Nilius B. Cytoskeletal modulation of the response to mechanical stimulation in human vascular endothelial cells. Pflügers Arch. 1994;428:569–576. doi: 10.1007/BF00374579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morita T, Kurihara H, Maemura K, Yoshizumi M, Nagai R, Yazaki Y. Role of Ca2+ and protein kinase C in shear stress-induced actin depolymerization and endothelin-1 gene expression. Circ Res. 1994;75:630–636. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.4.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henrion D, Terzi F, Matrougui K, Boulanger C, Duriez M, Boulanger C, Colucci-Guyon E, Babinet C, Briand P, Friedlander G, Poitevin P, Lévy BI. Impaired flow-induced dilation in mesenteric resistance arteries from mice lacking vimentin. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2909–2914. doi: 10.1172/JCI119840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown SC, Lucy JA. Dystrophin as a mechanochemical transducer in skeletal muscle. Bioessays. 1993;15:413–419. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stromer MH. The cytoskeleton in skeletal, cardiac and smooth muscle cells. Histol Histopathol. 1998;13:283–91. doi: 10.14670/HH-13.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, Ervasti JM, Leveille CJ, Slaughter CA, Sernett SW, Campbell KP. Primary structure of dystrophin-associated glycoproteins linking dystrophin to the extracellular matrix. Nature. 1992;355:696–702. doi: 10.1038/355696a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohlendieck K. Towards an understanding of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex: linkage between the extracellular matrix and the membrane cytoskeleton in muscle fibers. Eur J Cell Biol. 1996;69:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyatake M, Miike T, Zhao J, Yoshioka K, Uchino M, Usuku G. Possible systemic smooth muscle layer dysfunction due to a deficiency of dystrophin in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Sci. 1989;93:11–17. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(89)90157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Culligan KG, Mackey AJ, Finn DM, Maguire PB, Ohlendieck K. Role of dystrophin isoforms and associated proteins in muscular dystrophy. Int J Mol Med. 1998;2:639–648. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2.6.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlson CG. The dystrophinopathies: an alternative to the structural hypothesis. Neurobiol Dis. 1998;5:3–15. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fabbrizio E, Bonet-Kerrache A, Limas F, Hugon G, Mornet D. Dystrophin, the protein that promotes membrane resistance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;213:295–301. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chien KR. Stress pathways and heart failure. Cell. 1999;98:555–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Root DD. In situ molecular association of dystrophin with actin revealed by sensitized emission immuno-resonance energy transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5685–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lees D, Fabbrizio E, Mornet D, Pugnere D, Travo P. Parallel expression level of dystrophin and contractile performances of rat aortic smooth muscle. Exp Cell Res. 1995;218:401–404. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uchino M, Miike T, Iwashita H, Uyama E, Yoshioka K, Sugino S, Ando M. PCR and immunoblot analyses of dystrophin in Becker muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Sci. 1994;124:225–229. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90331-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rivier F, Robert A, Hugon G, Mornet D. Different utrophin and dystrophin properties related to their vascular smooth muscle distributions. FEBS Lett. 1997;408:94–98. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henrion D, Iglarz M, Lévy BI. Chronic endothelin-1 NO-dependent flow-induced dilation in resistance arteries from normotensive and hypertensive rats. Arterioscl Thromb Vase Biol. 1999;19:2148–2153. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.9.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koller A, Sun D, Kaley A. Role of shear stress and endothelial prostaglandins in flow and viscosity induced dilation of arterioles in vitro. Circ Res. 1993;72:1276–1284. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.6.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koller A, Huang A. Impaired nitric oxide-mediated flow-induced dilation in arterioles of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circ Res. 1994;74:416–421. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Juncos LA, Garvin J, Carretero OA, Ito S. Flow modulates myogenic responses in isolated microperfused rabbit afferent arterioles via endothelium-derived nitric oxide. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2741–2748. doi: 10.1172/JCI117977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friebel M, Klotz KF, Ley K, Gaethgens P, Pries PR. Flow-dependent regulation of arteriolar diameter in rat skeletal muscle in situ: role of endothelium-derived relaxing factor and prostanoids. J Physiol. 1995;483:715–726. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38a.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher AM. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–605. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ichioka S, Shibata M, Kosaki K, Sato Y, Harii K, Kamiya A. Effects of shear stress on wound-healing angiogenesis in the rabbit ear chamber. J Surg Res. 1997;72:29–35. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1997.5170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ando J, Kamiya A. Blood flow and vascular endothelial cell function. Front Med Biol Eng. 1993;5:245–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lau KS, Grange RW, Chang WJ, Kamm KE, Sarelius I, Stull JT. Skeletal muscle contractions stimulate cGMP formation and attenuate vascular smooth muscle myosin phosphorylation via nitric oxide. FEBS Lett. 1998;431:71–74. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00728-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radda GK. Of mice and men: from early NMR studies of the heart to physiological genomics. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;266:723–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Towbin JA, Bricker JT, Garson A., Jr Electrocardiographic criteria for diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in childhood. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:1545–1548. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90700-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halpern W, Osol G, Coy GS. Mechanichal behavior of pressurized in vitro prearteriolar vessels determined with a video system. Ann Biomed Ing. 1984;12:463–479. doi: 10.1007/BF02363917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henrion D, Dechaux E, Dowell FJ, Maclouf J, Samuel JL, Lévy BI, Michel JB. Alteration of flow-induced dilation in mesenteric resistance arteries of L-NAME treated rats is partially associated to induction of cyclooxygenase-2. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:83–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matrougui K, Loufrani L, Lévy BI, Henrion D. Role of angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation in the response to flow and pressure of rat resistance mesenteric arteries. Hypertension. 1999;34:659–665. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lévy BI, Benessiano J, Henrion D, Caputo L, Heymes C, Duriez M, Poitevin P, Samuel JL. Chronic blockade of AT2-subtype receptors prevents the effect of angiotensin II on the rat vascular structure. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:418–425. doi: 10.1172/JCI118807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muller JM, Chilian WM, Davis MJ. Integrin signaling transduces shear stress-dependent vasodilation of coronary arterioles. Circ Res. 1997;80:320–326. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.3.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]