Abstract

The enediynes, unified by their unique molecular architecture and mode of action, represent some of the most potent anticancer drugs ever discovered. The biosynthesis of the enediyne core has been predicted to be initiated by a polyketide synthase (PKS) that is distinct from all known PKSs. Characterization of the enediyne PKS involved in C-1027 (SgcE) and neocarzinostatin (NcsE) biosynthesis has now revealed that (i) the PKSs contain a central acyl carrier protein domain and C-terminal phosphopantetheinyl transferase domain; (ii) the PKSs are functional in heterologous hosts, and coexpression with an enediyne thioesterase gene produces the first isolable compound, 1,3,5,7,9,11,13-pentadecaheptaene, in enediyne core biosynthesis; and (iii) the findings for SgcE and NcsE are likely shared among all nine-membered enediynes, thereby supporting a common mechanism to initiate enediyne biosynthesis.

Keywords: C-1027, neocarzinostatin, phosphopantetheinyl transferase

The enediyne antitumor antibiotics are among the most cytotoxic natural products ever discovered and have been actively pursued for their potential utility in cancer chemotherapy with two, calicheamicin (CAL) and neocarzinostatin (NCS), currently in clinical use (1–3). The enediynes have a common unprecedented structural feature accountable for their potent cytotoxicity: an enediyne core containing two acetylenic groups conjugated to a double bond, harbored within a nine-membered ring exemplified by C-1027, NCS, or maduropeptin (MDP) (Fig. 1) or a 10-membered ring such as CAL and dynemicin (4–6). To date, there are 11 enediynes that have been structurally elucidated (4, 7) with several more potential enediynes in existence, including two marine-derived compounds hypothesized to originate as enediynes and to undergo aromatization upon isolation (8, 9) and several structurally uncharacterized enediynes that have been predicted based on conserved and apparently cryptic genetic information (10–12).

Fig. 1.

Structure of representative 9-membered enediynes C-1027, NCS, and MDP.

The biosynthetic gene clusters for C-1027 (13), NCS (14), MDP (15), and CAL (16) have been cloned and sequenced, and the first biosynthetic step leading to the enediyne core was speculated to be catalyzed by a new type of iterative polyketide synthase (PKS) that is shared among the entire enediyne family (12–16). PKSs catalyze decarboxylative condensation similar to fatty acid synthases (FASs) and likewise share homologous ketosynthase (KS) domains, responsible for decarboxylation and condensation, and acyltransferase (AT) domains, responsible for selection and loading of an acyl CoA (CoA)-substrate to a free thiol of an acyl carrier protein (ACP). The ACP thiol is generated posttranslationally by covalent tethering of the 4′-phosphopantetheine (4′-PP) component of CoA onto a conserved Ser, and this reaction, catalyzed by a phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase), is essential for initiating catalysis of most PKS and all FAS systems. Unlike FAS, which contain a full set of ketoreductase (KR), dehydratase (DH), and enoylreductase domains to reduce the resulting carbonyl to saturation, PKS can have anywhere from all to none of these activities, resulting in a product with various levels of oxidation.

Bacterial PKSs are often categorized by domain architecture and the iterative or noniterative nature during polyketide formation, and this classification has led to three groupings (17). Noniterative type I PKS are large proteins with multiple domains forming modules, a minimal module consisting of a KS, AT, and ACP domain, wherein each domain catalyzes a single event during polyketide biosynthesis (18). More often than not, a single protein harbors more than one module in a type I PKS. Iterative type II PKS consist of domains as individual proteins that together coordinate polyketide formation in trans (19). In this case, each domain is used several times during the elongation of a single polyketide chain. Iterative type III PKS, also called chalcone synthases, are ACP-independent consisting of a single KS protein catalyzing multiple decarboxylative condensations (20). Rather recently, several bacterial PKS have been found that do not fit these model systems (21–25). For example, several iterative PKS have been discovered that contain one module located on a single protein analogous to fungal PKSs, and many of these PKS have been functionally characterized in heterologous hosts (26–29). In addition, bacterial PKS were originally believed to be pantheinylated only by a discrete PPTase, but a PPTase integrated in a probable type I PKS has recently been described (30), thus resembling yeast FAS that contains a C-terminal PPTase on the α-subunit (31, 32). In both of these cases, the integrated PPTase has clear sequence and structural homology to its free-standing counterparts.

We now report experimental evidence to demonstrate that (i) the enediyne PKS, or PKSE, does indeed have a molecular architecture distinct from all known PKSs and includes ACP and PPTase domains; (ii) PKSE is active in heterologous hosts, producing an enzyme-bound linear polyene intermediate that can be hydrolyzed by a conserved thioesterase (TE) to afford an isolable compound; and (iii) this biosynthetic pathway is shared among the nine-membered enediyne family, thus supporting that a common mechanism is used to initiate enediyne biosynthesis.

Results and Discussion

Bioinformatics Prediction of the Molecular Architecture of PKSE.

PKSE has four probable domains based on sequence homology and putative active site mapping: a KS, AT, KR, and DH, sequentially located on a single protein from the N to the C terminus (Fig. 2A). The remaining regions, one located between the AT and KR of ≈220 aa and the other residing at the C terminus (≈350 aa), are shared among the PKSE family (minimum of 20% identity) but have no apparent sequence homology to other proteins, as revealed by using bioinformatics analysis (12). However, the head-to-tail domain organization of PKSE is very similar to that found in polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) synthases involved in eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid biosynthesis (33), and the KS and AT domains of PUFA synthases and PKSE show significant sequence homology [supporting information (SI) Fig. 4]. In contrast to PKSE, the region between the AT and KR for PUFA synthases consists of up to nine tandem ACP domains (33–35). Realizing that ACP is the ubiquitous anchor for all FAS and most PKS processes, we predicted that the central domain of PKSE is in fact a unique ACP. In addition, structural modeling of the C-terminal domain revealed significant similarities with the PPTase Sfp, including the active-site residues critical for Mg2+ coordination and hence PPTase activity (SI Fig. 5) (11, 36). Despite the fact that all biochemically characterized ACP-dependent PKSs to date use a discrete PPTase to activate ACPs in trans, the C-terminal domain was hypothesized to function as a PPTase.

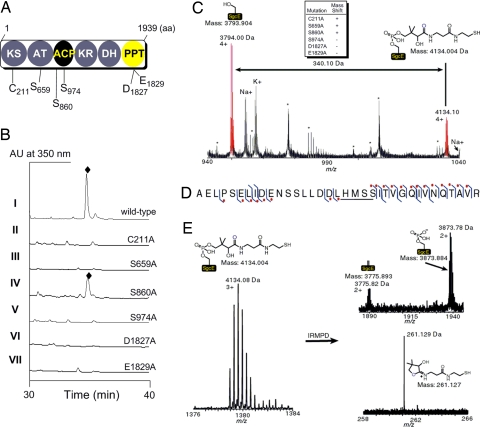

Fig. 2.

Functional assignments of SgcE. (A) Putative domain organization of PKSE and the amino acids of SgcE targeted for site-directed mutagenesis. (B) HPLC traces of C-1027 (♦) production from SB1005 using complementation plasmids expressing wild-type SgcE (pBS1049, I); C211A (pBS1064, II); S659A (pBS1069, III); S860A (pBS1070, IV); S974A (pBS1071, V); D1827A (pBS1071, VI); and E1831A (pBS1072, VII). (C) ESI-FTICR-MS analysis of the ACP-containing peptide fragment of heterologously produced SgcE indicating a + 340.1 Da mass shift consistent with the 4′-phospopantetheine (4′-PP) cofactor. Upper Center indicates whether a similar mass shift is observed for the indicated SgcE mutation. The asterisks (*) refer to peptides that are not the ACP active site, and Na+ and K+ are sodium and potassium adducts of the corresponding peptides. (D) Peptide ion subjected to collisionally activated dissociation. The right hook indicates that a b-fragment ion was identified and the left hook indicates that a y-fragment ion was identified. The red dot denotes fragment ions that contain the 340.1 Da modification. The location of the 340.1 Da modification is underlined. (E) Characteristic mass spectral pattern upon 4′-PP elimination as shown for SgcE. IRMPD, infrared multiphoton dissociation.

Mapping PKSE Domains and Active Sites in Vivo.

To investigate the significance of the PKSE domains, we used a PKSE complementation system in the C-1027 producer Streptomyces globisporus that had been developed in our laboratory (13). Inactivation of sgcE, the PKSE gene for C-1027 biosynthesis, yielded a ΔsgcE mutant strain SB1005 incapable of producing C-1027, the production of which could be restored by introducing a plasmid expressing a functional copy of sgcE under control of the constitutive ErmE* promoter as determined from HPLC and MS analysis. This approach was adopted to probe the role of individual domains of SgcE by preparing site-directed point mutations of residues considered critical for activity and therefore essential for C-1027 production (Fig. 2A and http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0711625105/DC1SI Text).

The catalytic domains that are known to be indispensable for PKS activity were first inactivated to verify their roles in C-1027 biosynthesis. The active-site Cys of the KS domain (C211) and the critical Ser of the AT domain (S659) were individually replaced with Ala, and the SgcE-mutant plasmids pBS1064 and pBS1069, respectively, introduced into SB1005 by conjugation. Fermentation of the resulting strains revealed that both complementation plasmids failed to restore C-1027 production, showing C211 and S659 are essential for SgcE activity and consistent with the designation of KS and AT domains (Fig. 2B).

Adjacent to the AT domain is a stretch of 81 amino acids with a conserved central Ser (S974) hypothesized as the site of the 4′-PP attachment (11, 13). A second conserved Ser (S860), located near the boundary of the AT and proposed ACP, was also targeted to serve as a control with the expectation that this boundary Ser is not essential for catalytic activity and therefore is not necessary for C-1027 biosynthesis. Each Ser was individually replaced with Ala, and the SgcE-mutant plasmids pBS1071 and pBS1070, respectively, introduced into SB1005. Fermentation of the resulting strains revealed that pBS1071 could not restore C-1027 production, whereas the pBS1070 restored C-1027 production (Fig. 2B), thus establishing that S974 is critical for SgcE activity and consistent with the designation of an ACP domain downstream of the AT.

The identification of the ACP domain implicates a PPTase is required for PKSE activity. The DxE motif (D107 and E109 of Sfp corresponding to D1827 and E1829 of SgcE) essential for Mg2+ coordination and hence PPTase activity was next targeted for mutagenesis (11, 36). Both D1827A and E1829A mutations were prepared, and the SgcE-mutant plasmids, pBS1077 and pBS1078, respectively, failed to restore C-1027 production when introduced into strain SB1005, showing these residues are critical for PKS activity and consistent with the designation of a PPTase domain (Fig. 2B).

Mapping the ACP and PPTase Domains of PKSE in Vitro.

To provide further evidence that the central domain functions as an ACP with S974 as the site of 4′-PP attachment, recombinant SgcE was produced in Escherichia coli and purified to near homogeneity (SI Fig. 6). The protein was subjected to peptide mapping by using a trypsin digest followed by HPLC purification of the proteolytic fragments, and each fraction was analyzed by using electrospray ionization–Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance–MS (37). The peptide fragment containing S974 was identified and determined to have a +340 mass shift consistent with a 4′-PP cofactor covalently attached to the Ser (apo-SgcE 3,794.00 Da observed, 3,793.90 Da calculated; holo-SgcE 4,134.08 Da observed, 4,134.00 Da calculated) (Fig. 2C). Upon subjecting the 4,134.08-Da ion fragment to collisionally activated dissociation, the +340-Da modification was localized to the five residues LHMSS, with the latter Ser corresponding to the active site S974 (Fig. 2D). Finally, subjecting the same ion to infrared multiphoton dissociation for tandem MS, the characteristic elimination signature of a 4′-PP cofactor was observed (Fig. 2E) (38). This method allowed the monitoring of both the 4′-PP elimination fragment ion (261.129 Da observed, 261.127 Da calculated) and the two modified forms of the peptide: the dehydroalanine (3,775.82 Da observed, 3,775.89 Da calculated) and the phospho-serine form (3,873.78 Da observed, 3,873.88 Da calculated). Together, the data provide compelling evidence to assign SgcE as an ACP-containing PKS that has an active site at S974.

With the ACP-containing peptide mapped, the complete assortment of SgcE mutants used in the in vivo studies were prepared and analyzed for their effect on the 4′-PP mass shift observed for the wild-type SgcE. As expected, the mass patterns of the C211A, S659A, and S860A SgcE mutants resembled the wild-type SgcE, whereas the S974A, D1827A, and E1829A mutations eliminated the observed 4′-PP mass shift (summarized in Fig. 2C). These experiments provided additional support for the designation of an ACP domain and provide direct evidence for the assignment of the C-terminal domain as a PPTase.

Inspired by the ability to map the ACP active site of recombinant SgcE, we prepared an E. coli expression plasmid for NcsE, the PKSE involved in NCS biosynthesis in Streptomyces carzinostaticus (14), and the protein was purified to near homogeneity (SI Fig. 6). Subjecting NcsE to the identical MS analyses that were performed with SgcE revealed S1007, the NcsE equivalent of S974, was also postranslationally modified with the 4′-PP cofactor (SI Fig. 7), thereby strengthening the conclusions deduced from active site mapping of SgcE and consistent with our prior prediction that all PKSE have identical domain functionality (12).

Phosphopantetheinylation of the ACP in Vitro.

The ACP designation was next confirmed by monitoring the incorporation of the 4′-PP cofactor directly in vitro (SI Fig. 8). We prepared constructs expressing the individual ACP domain of SgcE, a general approach that has been successfully used to elucidate domain function for large multidomain PKS and FAS (39–41). Because nothing was known about the structural elements necessary for potential PPTase recognition of this type of ACP, five versions were prepared, ranging from a standard ACP size of 81 amino acids (ACP81) to a long version (ACP212) encompassing the majority of the region residing between the AT and KR. All five versions were heterologously produced in E. coli and purified, and by using HPLC and MS analysis, it was determined that all five proteins were entirely in the apo-form (SI Table 1). When incubated with CoA and Svp, a promiscuous PPTase from the bleomycin-producer Streptomyces verticillus (42), each apo-ACP was quantitatively converted to holo-ACP, whose identity was confirmed by MS (SI Table 1), and this reaction occurred in a time-dependent manner, as exemplified with ACP81 (SI Fig. 8). The corresponding S974A mutation in ACP81 was prepared and, as expected, was unable to be 4′-phosphopantetheinylated by Svp, consistent with S974 as the site of 4′-PP attachment. Finally, recombinant ACPS, the E. coli PPTase involved in modification of FAS ACP (43), was prepared and unable to phosphopantetheinylate the apo-ACPs under the identical condition, suggesting that the formation of holo-SgcE during heterologous production is not due to endogenous E. coli ACPS. In total, the data are consistent with SgcE and NcsE being ACP-dependent, and this ACP domain is posttranslationally modified by a C-terminal PPTase domain.

Characterization of the PKSE Polyene Intermediate.

Because SgcE and NcsE contain a PPTase domain that phosphopantetheinylates the cognate ACP domain, both proteins should be functional, catalyzing polyketide biosynthesis from acyl CoA precursors when produced in a heterologous host without requiring an endogenous or coexpressed PPTase. Indeed, the purified SgcE or NcsE solution was a yellow color, and protein denaturation failed to remove the color from the protein suggesting that the pigment was most likely the result of a covalently bound product to the PKS (SI Fig. 6). UV/Vis spectroscopy of SgcE or NcsE revealed multiple absorption maxima between 350 and 450 nm, a profile reminiscent of a polyene (44), which would be the expected product based on the catalytic assignments of SgcE and NcsE. All SgcE mutants except S860A lacked the color and associated UV spectrum, thus supporting that the phenotype is due to a PKS-bound product and not a cofactor (SI Fig. 6).

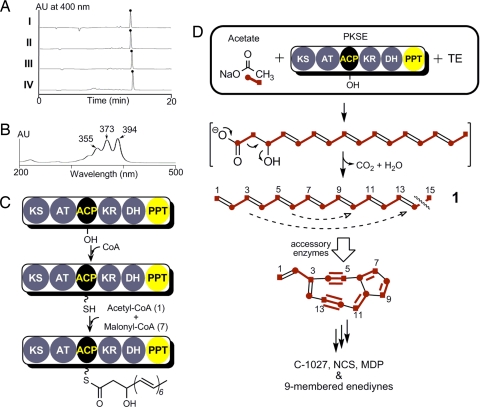

Exhaustive attempts to isolate sufficient quantity and quality of the PKS-bound product for spectroscopic analysis were met with little success, and therefore we took an alternative approach to generate an isolable SgcE and NcsE product. Found immediately downstream of all PKSE, excluding only within the C-1027 gene cluster where it is separated by six conserved ORFs, is a putative TE (SgcE10 and NcsE10, accession numbers AAL06692 and AAM78011, respectively) with sequence similarity to the family of 4-hydroxybenzoyl-CoA TE that catalyze the final step in the degradation of 4-chlorobenzoate. It was rationalized that this TE would hydrolyze the tethered polyketide intermediate from PKSE to afford an isolable product. Therefore, sgcE was coexpressed with sgcE10 in E. coli, and a bright yellow pigment was observed associated with the insoluble debris, which was readily extracted with organic solvent. HPLC analysis revealed a major peak (Fig. 3AI) with an UV/Vis profile similar to a polyene (Fig. 3B). An identical phenotype and HPLC profile were observed with coexpression of ncsE and ncsE10 (Fig. 3AII). In contrast, SgcE mutants S974A and D1827A, when coexpressed with sgcE10, failed to replicate this phenotype and produce the pigment. To ensure that the biosynthesis of this compound was not host-dependent, coexpression of ncsE and ncsE10 was also performed in Streptomyces lividans or Streptomyces albus, respectively, which afforded the identical HPLC profile as that from E. coli (Fig. 3A III and IV).

Fig. 3.

Biosynthesis of the first enediyne core intermediate by PKSE and TE. (A) Formation of the identical polyene product (●) using sgcE/E10 coexpression in E.coli (I) or ncsE/E10 in E.coli (II), S. lividans (III), or S. albus (IV). (B) UV/Vis profile of 1,3,5,7,9,11,13-pentadecaheptaene (1). (C) Final domain assignments and activity of nine-membered enediyne PKSE. (D) Tandem reactions catalyzed by PKSE/TE to produce the linear heptaene 1, the first isolable intermediate toward the biosynthesis of the enediyne core. The last intermediate bound to the ACP is a hypothetical PKS product.

Structure Elucidation of the PKSE/TE Product.

The SgcE/E10 and NcsE/E10 product (1) was isolated and purified as a yellow powder. HPLC-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI)-MS analysis yielded [M+H]+ and [M−H]− ions at m/z 199.1 and 197.1, respectively, suggesting a molecular weight of 198.1. High-resolution HPLC-APCI-MS analysis of 1 afforded a [M+H]+ ion at m/z = 199.1478, suggesting a molecular formula of C15H18 (calculated m/z = 198.1409) with seven degrees of unsaturation. The UV/Vis spectrum of 1 exhibited three-peak absorption bands at λmax 355, 373, and 394 nm, indicating the presence of a heptaene unit (Fig. 3B) (44–46).

Analysis of the 1H NMR spectrum of 1 (SI Fig. 9), with the aid of its 1H-1H COSY spectrum (SI Fig. 10), revealed the presence of a terminal methyl connected to a double bond as a doublet at δ 1.80 (J = 7.0 Hz, H15), two olefinic protons ascribed to a terminal methylene at δ 5.10 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, Ha1) and 5.23 (J = 17.0 Hz, Hb1), an olefinic proton at δ 6.39 (dt, J = 17.0, 10.0 Hz, H2), an olefinic proton at δ 6.10 (m, H13), an olefinic proton at δ 5.74 (dq, J = 15.0, 7.0 Hz, H14), and 10 overlapping olefinic protons at δ 6.18–6.34 (m, H3-H12). Thus, the structure of 1 was deduced as 1,3,5,7,9,11,13-pentadecaheptaene.

To further facilitate structure elucidation by 13C NMR and clarify the biosynthesis of 1, feeding experiments with [1-13C]-, [2-13C]-, and [1, 2-13C2]sodium acetate were performed. Each of the 13C-enriched 1 was similarly isolated and analyzed by HPLC-APCI-MS and 13C NMR and heteronuclear correlation experiments (SI Table 2). Incorporation of 13C-labeled acetate into 1 was 60–70%, as judged by the statistical isotopic distribution from MS analysis (SI Fig. 11). Feeding [1-13C]sodium acetate into the E. coli ncsE/E10 coexpression strain led to the enrichment of the C2, C4, C6, C8, C10, C12, and C14 signals in 1, whereas feeding [2-13C]sodium acetate into the coexpression strain led to the enrichment of the C1, C3, C5, C7, C9, C11, C13, and C15 signals in 1 as determined from the 13C NMR spectra (SI Fig. 12). The incorporation pattern of acetate units was readily established upon analysis of the 13C NMR spectra of [1-13C]-, [2-13C]-, and [1,2-13C2] sodium acetate enriched 1 (Fig. 3). Based on these 1H and 13C NMR experiments, we were able to assign the proton and carbon signals from C1 to C2 and C13 to C15 (SI Table 2). Although we were also able to assign the C13/C14 double bond as E on the base of the H,H-coupling constant (J = 15.0 Hz), the geometry of the other five double bonds in 1 was unclear due to the significant overlap of the 1H signal at δ 6.18–6.34 although the iterative nature of PKSE suggests all olefinic bonds are E configuration.

The structure of the SgcE/E10 or NcsE/E10 product allows us to propose the initial steps involved in the enediyne core biogenesis. First, SgcE or NcsE catalyzes seven rounds of Claisen condensation in an iterative manner with concomitant ketoreduction and dehydration to yield a ACP-tethered 3-hydroxy-4,6,8,10,12,14-hexadecahexaene product (Fig. 3C). The thioester linkage is subsequently hydrolyzed by SgcE10 or NcsE10 to generate a linear polyene that undergoes decarboxylation and dehydration to afford the fully conjugated 1. Although it is unclear whether decarboxylation and dehydration is catalyzed by E10, the isotopic labeling pattern as a result of this step is consistent with prior feeding experiments with the NCS producer (47), and it can be envisioned that further processing of the polyene product can lead to an enediyne core intermediate before structural divergence among the nine-membered enediynes (Fig. 3D).

Cross-Complementation Supporting a Common Mechanism for Initiation of Enediyne Biosynthesis.

We finally wished to extend the findings for SgcE and NcsE to demonstrate that all PKSE are likely functionally equivalent, thereby solidifying a common mechanism for initiation of enediyne biosynthesis. This was accomplished by plasmid-based expression of heterologous PKSE gene cassettes within two Streptomyces hosts: SB1005 and SB5002, ΔsgcE and ΔncsE mutant strains devoid of C-1027 and NCS production, respectively (13, 14). Plasmids pBS1049, pBS5020 (14), and pBS10005 (15), which contain sgcE, ncsE, and mdpE (the PKSE gene from the MDP cluster), respectively, were prepared and introduced into SB1005 by conjugation. Using HPLC and matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization-MS to monitor production, all of the recombinant strains gave [M+H]+ ions at m/z = 844.259 and 846.272, consistent with the molecular formula for C-1027 and its aromatized product and identical to those isolated from the wild-type strain (SI Table 3) (13). Similarly, after introduction into SB5002 by protoplast transformation, all three PKSE expression plasmids were able to restore NCS production, giving a characteristic [M + H]+ ion at m/z = 660.3, consistent with the molecular formula of NCS and identical to that isolated from the wild-type strain (14). Unexpectedly, pBS1088, an expression construct containing calE, the PKSE gene from the CAL cluster (11, 15), was unable to restore C-1027 or NCS production to SB1005 or SB5002, under the identical condition. However, unlike sgcE (13), ncsE (14), and mdpE (15), the functional expression of calE has not been established and it remains to be seen whether the 10-membered enediyne PKSE such as CalE are functionally equivalent to the nine-membered enediyne PKSE.

In conclusion, we have established that (i) the initial steps of enediyne core biosynthesis are catalyzed by the enediyne PKS, PKSE, that is ACP-dependent; (ii) the C-terminal PPTase domain of PKSE functions to phosphopantetheinylate the enediyne PKS by attachment of the 4′-PP cofactor from CoA to the ACP; (iii) the nine-membered enediyne PKSE is active when expressed in a heterologous host without requiring an endogenous or coexpressed PPTase and catalyzes iterative decarboxylative condensation, ketoreduction, and dehydration to afford a polyene intermediate that is hydrolyzed by the cognate TE to yield a discrete isolable compound characterized as 1,3,5,7,9,11,13-pentadecaheptaene; and (iv) PKSE is interchangeable within the nine-membered family of enediynes, suggesting that the biosynthesis of the nine-membered enediyne core occurs through a common polyene intermediate that is subsequently decorated in each case via different post-PKS tailoring enzymes. PKSE uses a molecular logic that is distinct from all known PKS and FAS paradigms (17–25, 30–36) and should serve as an inspiration for the continued search for other fatty acid and polyketide biosynthetic machinery. The characterization of a self-phosphopantetheinylating, functional enediyne PKS will be indispensable for combinatorial biosynthesis and genetic engineering in the quest to generate new enediynes and ultimately the discovery of new enediyne drugs with improved therapeutic index (48, 49).

Methods

The domain function and organization of PKSE were predicted by using BLAST analysis and comparative protein structure modeling by using Modeller 9v1 (www.salilab.org/modeller). Active-site residues deemed critical for domain function were substituted with Ala by using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis protocol (Stratagene). In vivo complementation of the PKSE mutant strains S. globisporus SB1005 and S. carzinostaticus SB5002 and isolation of C-1027 and NCS were carried out as described (13–15). All proteins for in vitro experiments were over-produced in E. coli and purified using standard procedures. Detailed procedures are provided in online supporting information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Li (Institute of Medicinal Biotechnology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing, China) for the wild-type S. globisporus strain. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health. Fellowships CA1059845 (to S.G.V.L.) and GM073323 (to P.C.D.) and Grants GM067725 (to N.L.K.) and CA113297 (to B.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0711625105/DC1.

References

- 1.Wang X-W, Xie H. Drugs Future. 1999;24:847–852. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorson JS, et al. Understanding and exploiting nature's chemical arsenal: the past, present and future of calicheamicin research. Curr Pharmacol Des. 2000;6:1841–1879. doi: 10.2174/1381612003398564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith AL, Nicolaou KC. The enediyne antibiotics. J Med Chem. 1996;39:2103–2117. doi: 10.1021/jm9600398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galm U, et al. Antitumor antibiotics: bleomycin, enediynes, and mitomycin. Chem Rev. 2005;105:739–758. doi: 10.1021/cr030117g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen B, Liu W, Nonaka K. Enediyne natural products: biosynthesis and prospect towards engineering novel antitumor agents. Curr Med Chem. 2003;10:2317–2325. doi: 10.2174/0929867033456701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xi X, Goldberg IH. Comprehensive Natural Products Chemistry. New York: Elsevier; 1999. pp. 553–592. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies J, et al. Uncialamycin, a new enediyne antibiotic. Org Lett. 2005;7:5233–5236. doi: 10.1021/ol052081f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchanan GO, et al. Sporolides A and B: structurally unprecedented halogenated macrolides from the marine actinomycete Salinospora tropica. Org Lett. 2005;7:2731–2734. doi: 10.1021/ol050901i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oh D-C, Williams PG, Kauffman CA, Jensen PR, Fenical W. Cyanosporasides A and B, chloro- and cyano-cyclopentaindene glycosides from the marine actinomycete “Salinispora pacifica”. Org Lett. 2006;8:1021–1024. doi: 10.1021/ol052686b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Udwary DW, et al. Genome sequencing reveals complex secondary metabolome in the marine actinomycete Salinospora tropica. Proc Natl Acac Sci USA. 2007;104:10376–10381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700962104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zazopoulos E, et al. A genomics-guided approach for discovering and expressing cryptic metabolic pathways. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:187–190. doi: 10.1038/nbt784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu W, et al. Rapid PCR amplification of minimal enediyne polyketide synthase cassettes leads to a predictive familial classification model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11959–11963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2034291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu W, Christenson SD, Standage S, Shen B. Biosynthesis of the enediyne antitumor antibiotic C-1027. Science. 2002;297:1170–1173. doi: 10.1126/science.1072110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu W, et al. The neocarzinostatin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces carzinostaticus ATCC 15944 involving two iterative type I polyketide synthases. Chem Biol. 2005;12:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Lanen SG, Oh T, Liu W, Wendt-Pienkowski E, Shen B. Characterization of the maduropeptin biosynthetic gene cluster from Actinomadura madurae ATCC 39144 supporting a unifying paradigm for enediyne biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13082–13094. doi: 10.1021/ja073275o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahlert J, et al. The calicheamicin gene cluster and its iterative type I enediyne PKS. Science. 2002;297:1173–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.1072105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staunton J, Weissman KJ. Polyketide biosynthesis: a millennium review. Nat Prod Rep. 2001;18:380–416. doi: 10.1039/a909079g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cortes J, Haydock SF, Roberts GA, Bevitt DJ, Leadlay PF. An unusually large multifunctional polypeptide in the erythromycin-producing polyketide synthase of Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Nature. 1990;348:176–178. doi: 10.1038/348176a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen B, Hutchinson CR. Enzymatic synthesis of a bacterial polyketide from acetyl and malonyl CoA by a type II polyketide synthase. Science. 1993;262:1535–1540. doi: 10.1126/science.8248801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Funa N, et al. A new pathway for polyketide synthesis in microorganisms. Nature. 1999;400:897–899. doi: 10.1038/23748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen B. Polyketide biosynthesis beyond the type I, II, and III polyketide synthase paradigms. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:285–295. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(03)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haynes SW, Challis GL. Nonlinear enzymatic logic in natural product modular mega-synthases and -synthetases. Curr Opin Drug Discov Dev. 2007;10:203–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austin MB, et al. Biosynthesis of Dictyostelium discoideum differentiaion-inducing factor by a hybrid type I fatty-acid-type III polyketide synthase. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:494–502. doi: 10.1038/nchembio811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bode HB, Müller R. The impact of bacterial genomics on natural product research. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:6828–6846. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng YQ, Tang GL, Shen B. Type I polyketide synthase requiring a discrete acyltransferase for polyketide biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3149–3154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0537286100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaisser S, Trefzer A, Stockert S, Kirschning A, Bechthold A. Cloning of an avilamycin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tu57. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6271–6278. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6271-6278.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wenzel SC, et al. Structure and biosynthesis of myxochromides S1–3 in Stigmatella aurantiaca: Evidence for an iterative bacterial type I polyketide synthase and for module skipping in nonribosomal peptide biosynthesis. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:375–385. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shao L, et al. Cloning and characterization of a bacterial iterative type I polyketide synthase gene encoding the 6-methylsalicyclic acid synthase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sthapit B, et al. Neocarzinostatin naphthoate synthase: an unique iterative type I PKS from neocarzinostatin producer Streptomyces carzinostaticus. FEBS Lett. 2004;566:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weissman KJ, Hong H, Oliynyk M, Siskos AP, Leadley PF. Identification of a phosphopantetheinyl transferase for erythromycin biosynthesis in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:116–125. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fichtlscherer F, Wellein C, Mittag M, Schweizer E. A novel function of yeast fatty acid synthase. Subunit alpha is capable of self-pantetheinylation. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:2666–2671. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lomakin IB, Xiong Y, Steitz TA. The crystal structure of yeast fatty acid synthase, a cellular machine with eight active sites working together. Cell. 2007;129:319–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Metz JM, et al. Production of polyunsaturated fatty acids by polyketide synthases in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Science. 2001;293:290–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1059593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaulmann U, Hertweck C. Biosynthesis of polyunsaturated fatty acids by polyketide synthases. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:1866–1870. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020603)41:11<1866::aid-anie1866>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okuyama H, Orikasa Y, Nishida T, Watanabe K, Morita N. Bacterial genes responsible for the biosynthesis of eicosapentaenoic and docohexaenoic acids and their heterologous expression. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:665–670. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02270-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mofid MR, Finking R, Essen LO, Marahiel MA. Structure-based mutational analysis of the 4′-phosphopantetheinyl transferase Sfp from Bacillus subtilis: carrier protein recognition and reaction mechanism. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4128–4136. doi: 10.1021/bi036013h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dorrestein PC, Kelleher NL. Dissecting nonribosomal and polyketide biosynthetic machineries using electrospray ionisation Fourier-Transform mass spectrometry. Nat Prod Rep. 2006;23:893–918. doi: 10.1039/b511400b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dorrestein PC, et al. Facile detection of acyl and peptidyl intermediates on thiotemplate carrier domains via phosphopantetheinyl elimination reactions during tandem mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1537–1546. doi: 10.1021/bi061169d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reed MAC, et al. The type I rat fatty acid synthase ACP shows structural homology and analogous biochemical properties to type II ACPs. Org Biomol Chem. 2003;1:463–471. doi: 10.1039/b208941f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walsh CT. Polyketide and nonribosomal peptide antibiotics: modularity and versatility. Science. 2004;303:1805–1810. doi: 10.1126/science.1094318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang Y, Kim C-Y, Mathews II, Cane DE, Khosla C. The 2.7-Å crystal structure of a 194-kDa homodimeric fragment of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11124–11129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601924103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sánchez C, Du L, Edwards DJ, Toney MD, Shen B. Cloning and characterization of a phosphopantetheinyl transferase from Streptomyces verticillus ATCC15003, the producer of the hybrid peptide-polyketide antitumor drug bleomycin. Chem Biol. 2001;8:725–738. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lambalot RH, Walsh CT. Cloning, overproduction, and characterization of the Escherichia coli holo-acyl carrier protein synthase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24658–24661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dinya ZM, Sztaricskai FJ. Ultraviolet and light absorption spectrometry. Drugs Pharm Sci. 1986;27:19–95. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mebane AD. 1,3,5,7,9-Decapentaene and 1,3,5,7,9,11,13-tetradecaheptaene. J Am Chem Soc. 1952;74:5227–5229. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bérdy J. CRC Handbook of Antibiotic Compounds. Ed 2. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hensens OD, Giner J, Goldberg IH. Biosynthesis of NCS Chrom A, the chromophore of the antitumor antibiotic neocarzinostatin. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:3295–3299. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kennedy DR, et al. Single chemical modifications of the enediyne core of C-1027, a radiomimetic antitumor drug, result in markedly varied cellular responses to DNA double strand breaks. Cancer Res. 2007;67:773–781. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kennedy DR, Ju J, Shen B, Beerman TA. Designer enediyne can generate DNA breaks, interstrand cross-links, or both, with concomitant changes in phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-like protein kinase-regulated damage responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:17632–17637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708274104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.