Abstract

RGS9-2 is a striatum-enriched protein that negatively modulates dopamine and opioid receptor signaling. We examined the role of RGS9-2 in modulating complex behavior. Genetic deletion of RGS9-2 does not lead to global impairments, but results in selective abnormalities in certain behavioral domains. RGS9 knockout (KO) mice have decreased motor coordination on the accelerating rotarod and deficits in working memory as measured in the delayed-match to place version of the water maze. In contrast, RGS9 KO mice exhibit normal locomotor activity, anxiety-like behavior, cue and contextual fear conditioning, startle threshold, and pre-pulse inhibition. These studies are the first to describe a role for RGS9-2 in motor coordination and working memory and implicate RGS9-2 as a potential therapeutic target for motor and cognitive dysfunction.

Keywords: RGS9, motor coordination, working memory, delayed-match to place water maze, dopamine, striatum

2. Introduction

The regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) family of proteins negatively modulate heterotrimeric G protein signaling by stimulating the GTPase activity of G protein α subunits (Berman and Gilman, 1998) and can function as effector molecules in certain signaling networks (De Vries et al., 2000). RGS proteins also regulate cellular excitability via their indirect modulation of G-protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRK) and voltage-dependent calcium channels (Berman et al., 1996; Chuang et al., 1998; Doupnik et al., 1997; Hollinger and Hepler, 2002; Sondek and Siderovski, 2001; Zhou et al., 2000).

The greater than 25 mammalian RGS proteins identified to date are defined by their 120 amino acid RGS domain and can be organized into subfamilies based on structural features and relative specificity for different G-protein subunits (Traynor and Neubig, 2005). Numerous RGS genes are expressed in brain with highly region-specific expression patterns (Dohlman and Thorner, 1997). The biological role of specific RGS proteins is currently an area of active research.

The RGS9 gene gives rise to two splice forms RGS9-1 and RGS9-2 (Granneman et al., 1998; He et al., 1998; Rahman et al., 1999) that differ only at their C terminus, where 18 C–terminal amino acid residues of RGS9-1 are replaced by a longer sequence of 209 amino acid residues. Furthermore, the 2 splice forms display highly specific and non-overlapping tissue distributions: RGS9-1 is expressed exclusively in retina, while RGS9-2 is highly enriched in striatal regions of the brain, with very low levels of expression seen throughout the remainder of the brain or in peripheral tissues (Granneman et al., 1998; Rahman et al., 1999; Thomas et al., 1998). The striatum, together with other neural structures of the basal ganglia, acts via multiple intrinsic and extrinsic circuits to control motor and cognitive functions. Moreover, one key feature of striatal neurons is their rich innervation by dopamine and high levels of expression of dopamine receptors (Aizman et al., 2000; Graybiel et al., 2000). Given the high expression of RGS9-2 in the striatum and its localization to medium spiny projection neurons (Kovoor and Lester, 2002; Rahman et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 1998), one would predict RGS9 to play a role in striatal dopamine-mediated behavior. Indeed, RGS9-2 over-expression diminishes sensitivity to the behavioral effects of DA agonists, while loss of RGS9 has the opposite effect (Rahman et al., 2003). In addition, RGS9 has been shown to be a critical negative regulator of opiate action in vivo (Zachariou et al., 2003). For instance, RGS9 KO mice show a 10-fold increase in sensitivity to the rewarding effects of morphine, as well as increased morphine analgesia, delayed development of analgesic tolerance, and severe morphine dependence and withdrawal.

Despite the growing literature on RGS9's role in dopamine signaling as a result of G protein modulation, little has been published on the role of RGS9-2 in dopamine modulated, striatum-dependent behaviors in the absence of prior pharmacologic manipulation. Thus, we have systematically examined the function of RGS9 in striatal-specific and dopamine-mediated behaviors, as well as other additional behavioral domains. Overall, our findings suggest that loss of this regulator of G protein signaling in the striatum leads to focal abnormalities in specific behavioral domains. In particular, RGS9 KO mice display deficits in motor coordination and working memory, but show normal responses in other tasks. Deficits in motor coordination and working memory are consistent with abnormal regulation of dopamine signaling in the striatum or prefrontal cortex, respectively (Fowler et al., 2002; Glickstein et al., 2002; Kellendonk et al., 2006). This is the first demonstration of the role of RGS9 in endogenously mediated complex behavior, as opposed to effects of exogenously applied drugs of abuse. Our findings suggest that RGS9-2 is a potential therapeutic target for disorders involving motor or cognitive dysfunction.

3. Results

The creation of RGS9 KO mice is described in detail elsewhere (Chen et al., 2000). For all behavioral tests, 11 male pairs of RGS9 KO and WT littermate offspring of heterozygous matings after 4 backcrosses into the C57BL6 background were used.

RGS9 KO Mice Exhibit Deficits in Motor Coordination but Have Normal Locomotor Activity

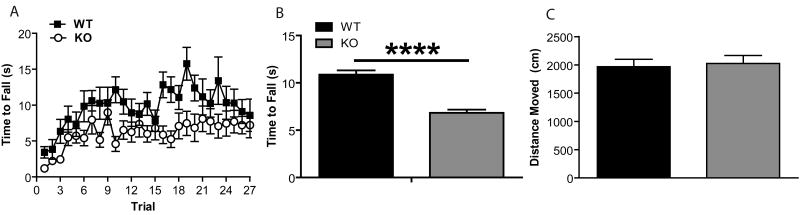

Because alterations in striatal dopamine signaling are predicted to alter striatal function and therefore affect motor output, gross motor coordination was examined in the RGS9 KO mice using the accelerating rotarod. RGS9 KO mice showed deficits in motor coordination compared to WT littermate controls (Fig. 1A; ANOVA revealed a main effect of Genotype, F1,20 = 5.64, p = 0.028, and a main effect of Trial, F26,520 = 4.82, p < 0.000001, B; t-test, p=5.05×10-12). However, there was no interaction between genotype and trial (F26,520 = 1.26, p=0.18) suggesting that RGS9 KO mice did not have a deficit in rate of acute motor learning. Consistent with Rahman et al., 2003, RGS9 KO mice exhibited horizontal locomotor activity in an open field arena that was indistinguishable from WT littermates (Fig. 1B, p = 0.76).

Figure 1. RGS9 KO Mice Exhibit Deficits in Motor Coordination but Normal Locomotor Activity.

(A) RGS9 KO mice have deficits in motor coordination as measured on the accelerating rotarod. ANOVA revealed a main effect of genotype [F1,20 = 5.64, p = 0.028], a main effect of trial, [F26,520 = 4.82, p < 0.000001 ] but no interaction between genotype and trial, [F26,520 = 1.26, p=0.18]. (B) Mean time to fall off rotarod over trails 8-27 in RGS9 KO and WT (p=5.05×10-12). (C)RGS9 KO mice show similar locomotor activity as WT in a 10 min open field test (p = 0.76).

Abnormal Episodic-like/Working Memory in RGS9 KO Mice

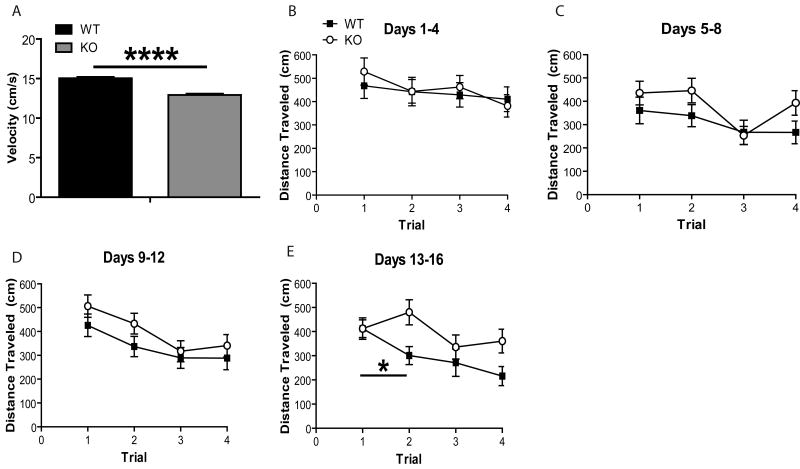

Given that dopamine action in the prefrontal cortex or striatum modulates working memory processes (Birrell and Brown, 2000; Fuster, 1997; Kellendonk et al., 2006; Markowitsch and Pritzel, 1977), we examined episodic-like/working memory using the delayed-match-to-place (DMTP) task. This task is similar to that of the standard hidden platform version of the Morris water maze (Powell et al., 2004) except that the location of the platform was altered each day. We followed the trial protocol described by (Nakazawa et al., 2003; Steele and Morris, 1999) with minor modifications. On each day, 4 trials were given with an inter-trial interval of 1-2 min. The mean latencies and distance traveled were relatively long for the first trial of a day because the mice had no prior knowledge of the platform location. However, mean latencies or distance traveled on the second trial can be potentially shortened based on the memory rapidly acquired during the first visit, and the reduced latency to reach the hidden platform or distance traveled before reaching the hidden platform in the second trial reflect the “savings” accrued from memory of the first trial (see Experimental Procedures for more details). Following Nakazawa et al., (2003), data analysis and presentation were subdivided into 4 blocks of four consecutive days (Figure 2B-E) and the data obtained during the 4 day-long testing session were combined. For all four trials conducted each day, distance traveled to reach the platform was averaged over multiple animals for each genotype.

Figure 2. RGS9 KO Mice Exhibit Impaired Working Memory in the DMP Task of the Water Maze.

(A) RGS9 KO mice exhibited slower swim speeds than WT (RGS9 KO vs. WT, p > 0.05). (B) Block 1: RGS9 KO and WT showed no savings over the first 4 days (Days 1-4) of DMP training as measured by distance traveled to reach the submerged platform (RGS9 KO: Trial 1 vs. Trial 2, p = 0.28; WT: Trial 1 vs. Trial 2, p = 0.76). RGS9 KO mice traveled the same as WT to reach the platform during both Trial 1 and Trial 2 (Trial 1, p = 0.44; Trial 2; p = 0.98). (C) Block 2: RGS9 KO and WT did not exhibit savings over the second 4 days (Days 5-8) of DMP training (RGS9 KO: Trial 1 vs. Trial 2, p = 0.89; WT: Trial 1 vs. Trial 2, p = 0.77). RGS9 KO mice traveled the same as WT to reach the platform during both Trial 1 and Trial 2 (Trial 1, p = 0.33; Trial 2, p = 0.13). (D) Block 3: Similarly, RGS9 KO and WT did not exhibit savings over the third 4 days (Days 9-12) of DMP training (RGS9 KO: Trial 1 vs. Trial 2, p = 0.25; WT: Trial 1 vs. Trial 2, p = 0.17). RGS9 KO mice traveled the same as WT to reach the platform during both Trial 1 and Trial 2 (Trial 1, p = 0.23; Trial 2, p = 0.12). (E) Block 4: Unlike RGS9 KO mice, WT showed a savings in the final 4 days of testing in the DMP as measured by distance traveled to reach the platform (RGS9 KO: Trial 1 vs. Trial 2, p = 0.29; WT: Trial 1 vs. Trial 2, p < 0.05). RGS9 KO mice traveled the same distance as WT during Trial 1 (p = 0.40), but traveled more during Trial 2 (p = 0.0060).

Consistent with a motor deficit, swim speed was lower in the RGS9 KO mice than the WT littermate pairs across all days for Trial 1 and Trial 2 (Fig. 2A, p < 0.00001). Important to note, swim speed on the final block (days 13-16) did not differ across genotype (not shown). To eliminate swim speed as a confound, we examined distance traveled to reach the platform for all four testing blocks (Fig. 2B-E). The mean distance traveled curves for all four trials of the DMTP training session (Fig 2A-D; blocks 1-3) and the testing session (Fig 2E; block 4) are shown in Figures 2B-E. There were no significant differences of distance traveled between the two genotypes in the first two trials during the initial training session (blocks 1-3). In the testing session (block 4), however, WT mice traveled significantly shorter distances on Trial 2 relative to Trial 1 suggesting a “savings” and rapid, one-trial, episodic-like/working memory (Fig. 2E, p < 0.05). In contrast, RGS9 KO mice did not show a savings on this test block (Fig. 2E, p = 0.29), suggesting an episodic-like/working memory deficit. We conclude that the reduced savings observed in the mutants relative to WT during the testing sessions is likely a consequence of the mutants' impaired capability to rapidly acquire memory for the new spatial location of the platform.

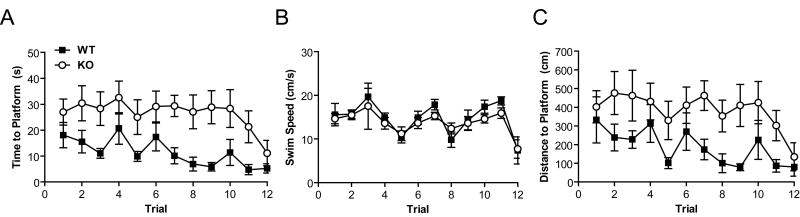

Our data suggest a deficit in episodic-like/working memory; however, visual perception data from human RGS9 mutants suggest that RGS9 mice may have visual deficits relating to luminance change accommodation (Nishiguchi et al., 2004). To assess whether visual deficits confounded the DMTP working memory results of the RGS9 KO mice, we tested the mice in the visible platform version of the water maze. Using latency to reach the platform, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed an initial difference in latency to reach the visible platform (main effect of genotype [F1,20 = 18.85, p = 0.00032]), improvement in performance over successive days (main effect of trial [F11,220 = 2.27, p = 0.012]), but no significant difference in the rate of learning the visible platform task (no interaction of genotype and trial [F11,220 = 0.55, p = 0.87]). Consistent with latency data, distance traveled to reach the platform was also initially higher in the RGS9 KO mice but without a significant difference in learning the visible platform task (Fig. 3C, ANOVA with repeated measures, main effect of genotype, F 1,20 = 14.42, p = 0.0011, main effect of trial, F11,220 = 2.07, p = 0.023, but not interaction, F11,220 = 0.53, p = 0.88). Importantly, by the final trial of the visible platform task, RGS9 KO mice were able to direct themselves to the visible platform equally well as their WT littermate controls (p > 0.05), making a visual deficit an unlikely explanation of water maze performance. Similar results were true of the final trial using distance traveled to reach the visible platform (not shown). In contrast with the DMTP test, swim speed did not differ by genotype [F1,11 = 0.82, p = 0.38] during the visible platform task.

Figure 3. RGS9 KO Mice are Impaired in the Visible Platform Task.

(A) RGS9 KO mice displayed an abnormal learning curve compared to WT during 12 trials as measured by latency to reach the visible platform in the water maze. ANOVA with repeated measures revealed a main effect of Genotype [F1,20 = 18.85, p = 0.00032], a main effect of Trial [F11,220 = 2.27, p = 0.012] but no interaction between Genotype and Trial [F11,220 = 0.55, p = 0.87]. However, there was no difference between RGS9 KO and WT in duration to the platform on trial 12 (p > 0.05). Legend in A applies to Panels A-C. (B) Swim speed was unaffected by genotype (F1,11 = 0.82, p = 0.38). (C) Similar to A, RGS9 KO mice displayed an abnormal learning curve compared to WT during 12 trials as measured by distance traveled to reach the visible platform in the water maze. ANOVA with repeated measures revealed a main effect of Genotype [F1,20 = 14.42, p = 0.0011], a main effect of Trial [F11,220 = 2.07, p = 0.023] but no interaction between Genotype and Trial [F11,220 = 0.53, p = 0.88]. However, there was no difference between RGS9 KO and WT in distance traveled during trial 12 (p>0.05).

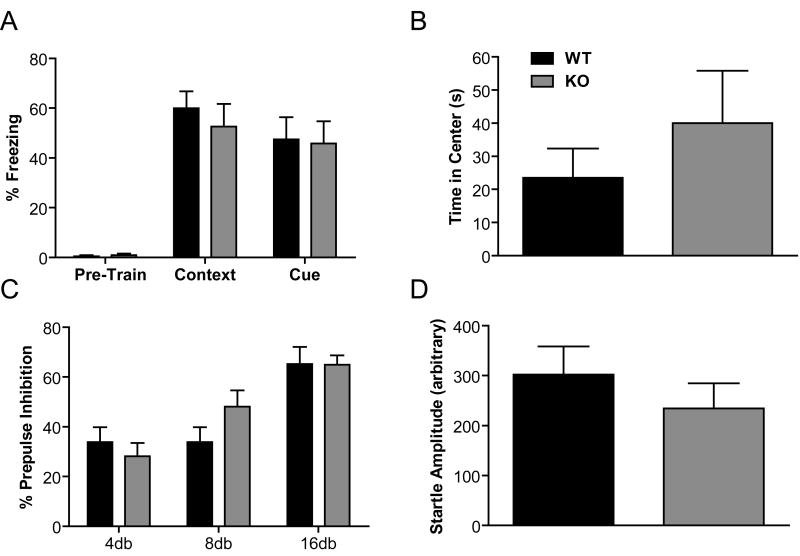

Emotional learning, Anxiety-like Behavior, Pre-pulse Inhibition, and Startle

Because we observed deficits in episodic-like/working memory, we were interested in assessing the role of RGS9-2 in emotional learning and memory. RGS9 KO mice were tested in a one-trial, context- and cue-dependent fear conditioning paradigm. In this paradigm, mice learn to associate a novel context or cue with foot shock. RGS9 KO mice exhibited normal freezing to both context and cue 24 h after training (Fig. 4A, context: RGS9 KO vs. wt, p = 0.52, cue: RGS9 KO vs. WT, p = 0.90). Furthermore, prior to training, RGS9 KO mice and their WT littermates displayed similar levels of freezing (Fig. 4A; pre-train: RGS9 KO vs. WT, p = 0.54).

Figure 4. RGS9 KO Mice Exhibit Normal Anxiety-like Behavior, Pre-Pulse Inhibition and Startle Amplitude.

(A) Both context- and cue-dependent fear learning was normal in RGS9 KO mice (context: RGS9 KO vs. WT, p = 0.52, cue: RGS9 KO vs. WT, p = 0.90). Legend in A applies to Panels A-D. (B) Anxiety-like behavior in the RGS9 KO mice does not differ from wt as measured by time spent in the center of an open field (p = 0.372). (C) In a pre-pulse inhibition test, RGS9 KO mice showed normal sensorimotor gating (4db, p = 0.49; 8db, p = 0.12; 16db, p =0.97). (D) Finally, startle amplitude did not differ across genotype (p = 0.65).

RGS9 KO mice displayed normal anxiety-like behavior as measured in an open field area. Specifically, RGS9 KO mice spent as much time in the center area of the open field as WT littermate control mice (Fig. 4B, p = 0.372). In addition, number of entries into the center was normal in RGS9 KO mice (not shown, p = 0.93). Sensory motor gating as measured by pre-pulse inhibition was normal in RGS9 KO mice (Fig. 4C, 4db, p = 0.49; 8db, p = 0.12; 16db, p =0.97). Finally, startle threshold did not differ in RGS9 KO mice and WT littermate controls (Fig. 4D, p = 0.65).

4. Discussion

Our data represent the first demonstration of RGS9 function in endogenously-mediated complex behavior. RGS9 KO knockout mice have poor motor coordination and deficits in working memory, as measured in the delayed-match-to-place version of the water maze. In contrast, RGS9 KO mice exhibit normal locomotor activity, emotional learning, anxiety-like behavior, startle threshold, and pre-pulse inhibition. Our findings suggest that RGS9-2 may be a potential therapeutic target for disorders involving motor or cognitive dysfunction.

RGS9 and Motor Coordination

RGS9 KO mice exhibited deficits in motor coordination. In particular, RGS9 KO mice performed worse than wild-type littermate controls on the accelerating rotarod and showed decreased swim speed during DMTP testing. Deficits in motor coordination in the RGS9 KO mice most likely reflect alterations in dopamine function in the striatum. RGS9-2 is enriched in the striatum and it is localized to medium spiny projection neurons (Kovoor et al., 2005; Rahman et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 1998). Indeed, RGS9-2 over-expression diminishes sensitivity to the behavioral effects of dopamine agonists, while loss of RGS9 has the opposite effect (Rahman et al., 2003). Alterations in dopamine signaling are known to result in deficits in motor coordination (Fernagut et al., 2003; Fowler et al., 2002; Kelly et al., 1998). While we feel that the motor coordination deficit seen in the RGS9 KO mice likely reflects a deficit in fine motor control, other possible explanations for the rotarod deficit are valid. For example, the rotarod deficit may be due to decreased endurance (or increased fatigue) in RGS9 KO mice, although this is less likely given the short duration of the test and their strong ability to swim in the Morris water maze for 60 seconds. Finally, RGS9 KO mice may have a deficit in attention processes which are also critical to maintain the necessary motor coordination. It is difficult to control for attention specifically, but the normal behavior in the classic version of the Morris water maze, early DMTP water maze trials, and fear conditioning tasks suggests that attention deficits are a much less likely explanation of their poor rotarod performance.

RGS9 and Working Memory

Working memory was examined in RGS9 KO mice using the DMTP version of the Morris water maze. Following 3 blocs of initial DMTP water maze training, control mice demonstrated significant rapidly learned “savings” from the first novel platform location trial to the second (bloc 4, Fig. 3E). RGS9 KO mice, on the other hand, did not demonstrate such savings even after multiple training trials using different platform locations (Fig. 3B-E). The lack of “savings” in the DMTP task strongly suggests that the mutant mice are impaired in learning the new location of the platform following a single trial. Such findings are variably interpreted in cognitive terms as a deficit in episodic-like memory, in working memory, or in one-trial “flashbulb” memory (Nakazawa et al., 2003; Seif et al., 2004; Steele and Morris, 1999). This task clearly requires an element of working memory between the first and second trials as well as a reasonable amount of long-lasting memory of the organization of peripheral/spatial cues in the room. Given normal hidden platform water maze behavior observed in a separate cohort of RGS9 KO mice (not shown); we feel that these data most likely represent a working memory problem.

Working memory is known to be subjected to dopaminergic modulation in the prefrontal cortex (Birrell and Brown, 2000; Fuster, 1997; Kellendonk et al., 2006; Markowitsch and Pritzel, 1977). Furthermore, alterations in dopamine in the striatum have resulted in impairments in working memory (Kellendonk et al., 2006). Given that the striatum participates in a cortico-striatal-pallido-thalamo-cortical associative loop and perturbing this circuit at any point may affect its function, and the fact that studies in primates and rats show that dysfunction of the striatum produces similar deficits as dysfunction of the PFC (Battig et al., 1960; Divac, 1972; Partiot et al., 1996), it is not surprising that striatal dysfunction leads to working memory impairments.

Working memory impairments are often seen in schizophrenia (Elvevag and Goldberg, 2000; Goldman-Rakic and Selemon, 1997). Dysfunction of dopamine transmission in the striatum has been suggested to be an important component in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia (Abi-Dargham et al., 2000; Breier et al., 1997; Laruelle et al., 1996; Laruelle, 1998; Seeman and Kapur, 2000; Wong et al., 1986). Interestingly, (Seeman and Guan, 2007) has shown a 22% decrease in RGS9 in the hippocampus of schizophrenia patients.

Other factors such as locomotor activity, motor coordination, or vision did not appear to account for deficits seen in the DMP task. Consistent with Rahman et al., 2003, RGS9 KO mice exhibit normal locomotor activity. Given that RGS9 KO mice exhibit motor coordination deficits on the rotarod, we examined swim speed during the DMP task. Overall, RGS9 KO mice exhibited decreased swim speed compared to wild-type littermate controls. However, on the test bloc (Days 13-16) where working memory abnormalities were observed, mutant mice showed normal swim speeds equivalent to controls. However, to eliminate swim speed as a variable, we measured distance traveled to reach the platform, not latency to reach the platform. Even using distance traveled to reach the platform, RGS9 KO mice exhibited a clear abnormality on the DMTP task in the final bloc of trials suggesting that this deficit was specific to working memory. Finally, visual perception data from human RGS9 mutants suggest that RGS9 KO mice may have visual deficits relating to luminance change accommodation (Nishiguchi et al., 2004). Our DMTP experiments were performed under uniform, constant illumination, making a similar deficit in mice an unlikely explanation for our results. Furthermore, RGS9 KO mice ultimately were able to reach the visible platform with equal latency and equally short path lengths as wild-type littermate controls in spite of a constantly varying platform location on each trial. Thus, it is unlikely that deficits seen in the DMP are due to alterations in locomotor activity, motor coordination, or vision.

Deficits in visible platform water maze task have been associated with lesions of the striatum (Devan et al., 1999; McDonald and White, 1994; Thullier et al., 1996). Given that RGS9-2 is enriched in the striatum (Rahman et al., 1999) and dopaminergic modulation is important to striatal function (Fechtali et al., 1994; Mercuri et al., 1985; Rolls et al., 1984; Tecuapetla et al., 2007; Twery et al., 1993), one might expect deficits in striatum-dependent tasks such as visible platform water maze. Unfortunately, while our visible platform data suggest an initial difference in ability in the visible platform task, no clear difference in rate of acquisition or learning of this task could be clearly demonstrated.

To determine if deficits in working memory generalized to all learning, RGS9 KO mice were tested in a one-trial, context- and cue-dependent fear conditioning paradigm. In this paradigm, mice learn to associate a novel context or cue with foot shock. In contrast to working memory deficits, RGS9 KO mice show normal contextual and cue-dependent fear memory suggesting that the deficit in the mutant mice is specific to working memory. Furthermore, a separate cohort of RGS9 KO mice exhibited normal classical Morris water maze behavior (not shown). In addition, the mutants showed normal anxiety-like behavior, pre-pulse inhibition and startle threshold. These data suggest a rather selective effect of RGS9 deletion on particular behavioral domains rather than a global dysfunction affecting multiple behaviors.

Conclusions

We have systematically examined the function of RGS9 in complex behavior. Overall, our findings suggest that loss of RGS9-2 leads to focal abnormalities in specific behavioral domains. In particular, RGS9 KO mice display deficits in motor coordination and working memory, but show normal locomotor activity, anxiety-like behavior, startle threshold, and pre-pulse inhibition. Our findings suggest that manipulation of RGS9-2 may be a useful target for disorders with motor or cognitive dysfunction.

4. Experimental Procedure

Genetic Manipulations

To reduce genetic and experimental variability, male RGS9 KO and their male wild-type littermate control mice (Chen et al., 2000) were generated from heterozygous matings following 4 backcrosses into C57BL6 background. For all data presented we used 11 male pairs of RGS9 KO and their littermate, wild-type (WT) controls. Mice were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment with a 12-hr light/12-hr dark cycle and had free access to food and water.

Behavioral Overview

Experimenters were blind to genotype during behavioral testing. All mice ranged from 6-10 months of age during the behavioral testing, and all KO/WT pairs were born within 2-4 weeks of each other. Except where noted, mice were allowed to rest for at least 1 wk between tests with the order of testing as follows: fear conditioning, delayed match to place version of the Morris water maze, visible platform water maze, open field, accelerating rotarod, and pre-pulse inhibition (PPI), and shock threshold. Mice were moved within the animal facility to the testing room and allowed to habituate to the new location for at least 1 hr prior to behavioral testing. Significance was taken as p < 0.05 for all experiments.

Accelerating Rotarod and Locomotor Activity

An accelerating rotarod designed for mice (IITC Life Sciences) was used essentially as described (Powell et al., 2004) except 3 sets of 3 trials were performed per day over 3 days. Briefly, the rotarod was activated after placing a mouse on the motionless rod. The rod accelerated from 0 to 45 revolutions per min in 60 sec. Time to fall off the rod or to turn on full revolution was measured. Data were analyzed with a two-way repeated measures ANOVA.

Delayed Matching-to-Place (DMTP) Version of the Morris Water Maze

The DMTP protocol was similar to that previously reported (Nakazawa et al., 2003; Steele and Morris, 1999). The water maze used has been previously described (Powell et al., 2004). The experiments were conducted in two phases (1) training on the DMTP; (2) DMTP testing. Throughout testing, the single escape platform (10 cm diameter) was located ∼1.0 cm below the surface of the water. Throughout the two behavioral phases, the platform location was altered in a pseudo-random fashion to 1 of 16 predetermined locations within the pool while avoiding successive platform locations in the same quadrant (see Nakazawa et al., 2003 for details). Trials began at North, East, South, and West in a pseudo-random varying sequence with mice facing the pool wall. Mice were trained with four trials per day with an intertrial interval of 1-2 min for 16 consecutive days between 8am and 2pm (12 days of training, 4 days of testing). In each trial, mice were allowed to search for the platform for up to 60 s. Once on the platform, mice remained there for 30 sec during the first trial and 15 sec on the three subsequent trials. If they did not find the platform in 60 sec, mice were led by the experimenter to the platform and left there for the appropriate time before returning to their home cage. Latency to reach the platform, distance traveled to reach the platform, and swim speed were recorded with automated videotracking software from Noldus (Ethovision 2.3.19). The reduction in distance traveled or latency to reach the platform in the second trial was compared to that in the first trial (“savings”) within a session. This measure reflects the animal's ability to acquire memory for the platform location rapidly based on a single exposure. Analysis was completed with Student's t test.

During visible platform experiments, the platform was marked with a gray foam block on a plastic syringe attached to the platform, and spatial cues were covered with white curtains. Visible water maze was run for 2 days (6 trials per day) shortly after the delayed matching-to-place test. Analysis was completed using a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures.

Fear Conditioning

Fear conditioning was performed essentially as described (Cai et al., 2006; Powell et al., 2004; Shukla et al., 2007). Briefly, mice were placed in the shock context for two min, then a 30 sec, 90 dB tone co-terminating in a 2 sec, 0.5 mA foot shock was delivered twice with a 1 min interstimulus interval. Mice remained in the context for 2 min before returning to their home cage. Freezing behavior (motionless except respirations) was monitored at 10 sec intervals by an observer blind to the genotype. To test for contextual learning 24 hr after training, mice were placed into the same training context for 5 min and scored for freezing behavior every 10 sec. To assess cue-dependent fear conditioning, mice were placed in a novel environment 3 hr after the context test. Freezing behavior was assessed during a 3 min baseline followed by a 3 min presentation of the tone. Cue-dependent fear conditioning was determined by subtracting baseline freezing from freezing during the tone. Student's t test was used to analyze the data.

Anxiety-like Behavioral Test, Pre-pulse Inhibition, and Startle Amplitude

Open field was performed as described (Cai et al., 2006; Powell et al., 2004). Locomotor activity was also recorded in the open field test with video tracking software (Noldus Ethovision). Startle threshold and pre-pulse inhibition protocol was performed as described (Kwon et al., 2006). Data were analyzed using Student's t test.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (K08 MH065975-04 to C.M.P.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abi-Dargham A, Rodenhiser J, Printz D, Zea-Ponce Y, Gil R, Kegeles LS, Weiss R, Cooper TB, Mann JJ, Van Heertum RL, Gorman JM, Laruelle M. Increased baseline occupancy of D2 receptors by dopamine in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8104–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizman O, Brismar H, Uhlen P, Zettergren E, Levey AI, Forssberg H, Greengard P, Aperia A. Anatomical and physiological evidence for D1 and D2 dopamine receptor colocalization in neostriatal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:226–30. doi: 10.1038/72929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battig K, Rosvold HE, Mishkin M. Comparison of the effects of frontal and caudate lesions on delayed response and alternation in monkeys. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1960;53:400–4. doi: 10.1037/h0047392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman DM, Kozasa T, Gilman AG. The GTPase-activating protein RGS4 stabilizes the transition state for nucleotide hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27209–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman DM, Gilman AG. Mammalian RGS proteins: barbarians at the gate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1269–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell JM, Brown VJ. Medial frontal cortex mediates perceptual attentional set shifting in the rat. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4320–4. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04320.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breier A, Su TP, Saunders R, Carson RE, Kolachana BS, de Bartolomeis A, Weinberger DR, Weisenfeld N, Malhotra AK, Eckelman WC, Pickar D. Schizophrenia is associated with elevated amphetamine-induced synaptic dopamine concentrations: evidence from a novel positron emission tomography method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2569–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W, Blundell J, Han J, Greene RW, Powell CM. Post-reactivation Glucocorticoids Impair Recall of Established Fear Memory. J Neuroscience. 2006;26:9560–9566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2397-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Chen KS, Knox J, Inglis J, Bernard A, Martin SJ, Justice A, McConlogue L, Games D, Freedman SB, Morris RG. A learning deficit related to age and beta-amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2000;408:975–9. doi: 10.1038/35050103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang HH, Yu M, Jan YN, Jan LY. Evidence that the nucleotide exchange and hydrolysis cycle of G proteins causes acute desensitization of G-protein gated inward rectifier K+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11727–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries L, Zheng B, Fischer T, Elenko E, Farquhar MG. The regulator of G protein signaling family. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:235–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devan BD, McDonald RJ, White NM. Effects of medial and lateral caudate-putamen lesions on place- and cue-guided behaviors in the water maze: relation to thigmotaxis. Behav Brain Res. 1999;100:5–14. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divac I. Neostriatum and functions of prefrontal cortex. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 1972;32:461–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohlman HG, Thorner J. RGS proteins and signaling by heterotrimeric G proteins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3871–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doupnik CA, Davidson N, Lester HA, Kofuji P. RGS proteins reconstitute the rapid gating kinetics of gbetagamma-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:10461–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvevag B, Goldberg TE. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is the core of the disorder. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2000;14:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fechtali T, Issoual D, Abraini JH. D1 receptors modulate striatal dopamine release induced by the stimulation of both D1 and D2 receptors: in vivo voltammetric data revisited. J Physiol Paris. 1994;88:331–3. doi: 10.1016/0928-4257(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernagut PO, Chalon S, Diguet E, Guilloteau D, Tison F, Jaber M. Motor behaviour deficits and their histopathological and functional correlates in the nigrostriatal system of dopamine transporter knockout mice. Neuroscience. 2003;116:1123–30. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00778-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler SC, Zarcone TJ, Vorontsova E, Chen R. Motor and associative deficits in D2 dopamine receptor knockout mice. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2002;20:309–21. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(02)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster JM. Network memory. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:451–9. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickstein SB, Hof PR, Schmauss C. Mice lacking dopamine D2 and D3 receptors have spatial working memory deficits. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5619–29. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05619.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS, Selemon LD. Functional and anatomical aspects of prefrontal pathology in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23:437–58. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granneman JG, Zhai Y, Zhu Z, Bannon MJ, Burchett SA, Schmidt CJ, Andrade R, Cooper J. Molecular characterization of human and rat RGS 9L a novel splice variant enriched in dopamine target regions and chromosomal localization of the RGS 9 gene. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:687–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM, Canales JJ, Capper-Loup C. Levodopa-induced dyskinesias and dopamine-dependent stereotypies: a new hypothesis. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:S71–7. doi: 10.1016/s1471-1931(00)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Cowan CW, Wensel TG. RGS9, a GTPase accelerator for phototransduction. Neuron. 1998;20:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollinger S, Hepler JR. Cellular regulation of RGS proteins: modulators and integrators of G protein signaling. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:527–59. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellendonk C, Simpson EH, Polan HJ, Malleret G, Vronskaya S, Winiger V, Moore H, Kandel ER. Transient and selective overexpression of dopamine D2 receptors in the striatum causes persistent abnormalities in prefrontal cortex functioning. Neuron. 2006;49:603–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MA, Rubinstein M, Phillips TJ, Lessov CN, Burkhart-Kasch S, Zhang G, Bunzow JR, Fang Y, Gerhardt GA, Grandy DK, Low MJ. Locomotor activity in D2 dopamine receptor-deficient mice is determined by gene dosage, genetic background, and developmental adaptations. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3470–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03470.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovoor A, Lester HA. Gi Irks GIRKs. Neuron. 2002;33:6–8. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00572-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovoor A, Seyffarth P, Ebert J, Barghshoon S, Chen CK, Schwarz S, Axelrod JD, Cheyette BN, Simon MI, Lester HA, Schwarz J. D2 dopamine receptors colocalize regulator of G-protein signaling 9-2 (RGS9-2) via the RGS9 DEP domain and RGS9 knock-out mice develop dyskinesias associated with dopamine pathways. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2157–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2840-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon CH, Luikart BW, Powell CM, Zhou J, Matheny SA, Zhang W, Li Y, Baker SJ, Parada LF. Pten regulates neuronal arborization and social interaction in mice. Neuron. 2006;50:377–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, van Dyck CH, Gil R, D'Souza CD, Erdos J, McCance E, Rosenblatt W, Fingado C, Zoghbi SS, Baldwin RM, Seibyl JP, Krystal JH, Charney DS, Innis RB. Single photon emission computerized tomography imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in drug-free schizophrenic subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9235–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M. Imaging dopamine transmission in schizophrenia. A review and meta-analysis. Q J Nucl Med. 1998;42:211–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitsch HJ, Pritzel M. Comparative analysis of prefrontal learning functions in rats, cats, and monkeys. Psychol Bull. 1977;84:817–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RJ, White NM. Parallel information processing in the water maze: evidence for independent memory systems involving dorsal striatum and hippocampus. Behav Neural Biol. 1994;61:260–70. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(05)80009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercuri N, Bernardi G, Calabresi P, Cotugno A, Levi G, Stanzione P. Dopamine decreases cell excitability in rat striatal neurons by pre- and postsynaptic mechanisms. Brain Res. 1985;358:110–21. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90954-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa K, Sun LD, Quirk MC, Rondi-Reig L, Wilson MA, Tonegawa S. Hippocampal CA3 NMDA receptors are crucial for memory acquisition of one-time experience. Neuron. 2003;38:305–15. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiguchi KM, Sandberg MA, Kooijman AC, Martemyanov KA, Pott JW, Hagstrom SA, Arshavsky VY, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Defects in RGS9 or its anchor protein R9AP in patients with slow photoreceptor deactivation. Nature. 2004;427:75–8. doi: 10.1038/nature02170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partiot A, Verin M, Pillon B, Teixeira-Ferreira C, Agid Y, Dubois B. Delayed response tasks in basal ganglia lesions in man: further evidence for a striato-frontal cooperation in behavioural adaptation. Neuropsychologia. 1996;34:709–21. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(95)00143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell CM, Schoch S, Monteggia L, Barrot M, Matos MF, Feldmann N, Sudhof TC, Nestler EJ. The presynaptic active zone protein RIM1alpha is critical for normal learning and memory. Neuron. 2004;42:143–53. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00146-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman Z, Gold SJ, Potenza MN, Cowan CW, Ni YG, He W, Wensel TG, Nestler EJ. Cloning and characterization of RGS9-2: a striatal-enriched alternatively spliced product of the RGS9 gene. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2016–26. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02016.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman Z, Schwarz J, Gold SJ, Zachariou V, Wein MN, Choi KH, Kovoor A, Chen CK, DiLeone RJ, Schwarz SC, Selley DE, Sim-Selley LJ, Barrot M, Luedtke RR, Self D, Neve RL, Lester HA, Simon MI, Nestler EJ. RGS9 modulates dopamine signaling in the basal ganglia. Neuron. 2003;38:941–52. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00321-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET, Thorpe SJ, Boytim M, Szabo I, Perrett DI. Responses of striatal neurons in the behaving monkey. 3. Effects of iontophoretically applied dopamine on normal responsiveness. Neuroscience. 1984;12:1201–12. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P, Kapur S. Schizophrenia: more dopamine, more D2 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7673–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.7673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P, Guan HC. Dopamine partial agonist action of (-)OSU6162 is consistent with dopamine hyperactivity in psychosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;557:151–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seif GI, Clements KM, Wainwright PE. Effects of distraction and stress on delayed matching-to-place performance in aged rats. Physiol Behav. 2004;82:477–87. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla K, Kim J, Blundell J, Powell CM. Learning-induced Glutamate Receptor Phosphorylation Resembles That Induced by Long Term Potentiation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18100–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702906200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondek J, Siderovski DP. Ggamma-like (GGL) domains: new frontiers in G-protein signaling and beta-propeller scaffolding. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61:1329–37. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00633-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele RJ, Morris RG. Delay-dependent impairment of a matching-to-place task with chronic and intrahippocampal infusion of the NMDA-antagonist D-AP5. Hippocampus. 1999;9:118–36. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1999)9:2<118::AID-HIPO4>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tecuapetla F, Carrillo-Reid L, Bargas J, Galarraga E. Dopaminergic modulation of short-term synaptic plasticity at striatal inhibitory synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10258–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703813104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EA, Danielson PE, Sutcliffe JG. RGS9: a regulator of G-protein signalling with specific expression in rat and mouse striatum. J Neurosci Res. 1998;52:118–24. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980401)52:1<118::AID-JNR11>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thullier F, Lalonde R, Mahler P, Joyal CC, Lestienne F. Dorsal striatal lesions in rats. 2: Effects on spatial and non-spatial learning. Arch Physiol Biochem. 1996:307–12. doi: 10.1076/apab.104.3.307.12895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynor JR, Neubig RR. Regulators of G protein signaling & drugs of abuse. Mol Interv. 2005;5:30–41. doi: 10.1124/mi.5.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twery MJ, Thompson LA, Walters JR. Electrophysiological characterization of rat striatal neurons in vitro following a unilateral lesion of dopamine cells. Synapse. 1993;13:322–32. doi: 10.1002/syn.890130405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong DF, Wagner HN, Jr, Tune LE, Dannals RF, Pearlson GD, Links JM, Tamminga CA, Broussolle EP, Ravert HT, Wilson AA, Toung JK, Malat J, Williams JA, O'Tuama LA, Snyder SH, Kuhar MJ, Gjedde A. Positron emission tomography reveals elevated D2 dopamine receptors in drug-naive schizophrenics. Science. 1986;234:1558–63. doi: 10.1126/science.2878495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariou V, Georgescu D, Sanchez N, Rahman Z, DiLeone R, Berton O, Neve RL, Sim-Selley LJ, Selley DE, Gold SJ, Nestler EJ. Essential role for RGS9 in opiate action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13656–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2232594100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou JY, Siderovski DP, Miller RJ. Selective regulation of N-type Ca channels by different combinations of G-protein beta/gamma subunits and RGS proteins. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7143–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07143.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]