Abstract

Chromatin-modifying factors regulate both transcription and DNA replication. The yFACT chromatin-reorganizing complex is involved in both processes, and the sensitivity of some yFACT mutants to the replication inhibitor hydroxyurea (HU) is one indication of a replication role. This HU sensitivity can be suppressed by disruptions of the SET2 or CHD1 genes, encoding a histone H3(K36) methyltransferase and a chromatin remodeling factor, respectively. The additive effect of set2 and chd1 mutations in suppressing the HU sensitivity of yFACT mutants suggests that these two factors function in separate pathways. The HU suppression is not an indirect effect of altered regulation of ribonucleotide reductase induced by HU. set2 and chd1 mutations also suppress the HU sensitivity of mutations in other genes involved in DNA replication, including CDC2, CTF4, ORC2, and MEC1. Additionally, a chd1 mutation can suppress the lethality normally caused by disruption of either MEC1 or RAD53 DNA damage checkpoint genes, as well as the lethality seen when a mec1 sml1 mutant is exposed to low levels of HU. The pob3 defect in S-phase progression is suppressed by set2 or chd1 mutations, suggesting that Set2 and Chd1 have specific roles in negatively regulating DNA replication.

EUKARYOTIC DNA is packaged into nucleosomes, which reduces access by DNA-binding proteins. Factors that modify chromatin structure therefore play essential roles in both transcription and DNA replication (Orphanides et al. 1999; Schlesinger and Formosa 2000; Formosa et al. 2001, 2002; Krogan et al. 2002; Biswas et al. 2005; Budd et al. 2005). These factors include enzymes that modify histones post-translationally (Berger 2007), ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling factors that reposition nucleosomes (Cairns 2005), and ATP-independent chromatin-reorganizing factors such as the facilitates chromatin transcription (FACT) complex (Formosa 2003). The mammalian FACT complex was identified as a factor that promoted in vitro RNA polymerase II transcription, using chromatin as a template (Orphanides et al. 1998). The yeast FACT (yFACT) complex consists of two subunits, Spt16 and Pob3, and an associated high-mobility group (HMG) protein Nhp6 (Brewster et al. 2001; Formosa et al. 2001). In vitro studies show that yFACT alters the accessibility of DNA within nucleosomes without hydrolyzing ATP and without repositioning the histone octamer core relative to the DNA (Formosa et al. 2001; Rhoades et al. 2004; Biswas et al. 2005).

Genetic and biochemical evidence indicates that yFACT has roles in both transcription and DNA replication. The SPT16 and POB3 genes are both essential for viability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and alleles with visible phenotypes have been isolated (Malone et al. 1991; Rowley et al. 1991; Schlesinger and Formosa 2000; Formosa et al. 2001). yFACT mutants show sensitivity to compounds that inhibit either transcriptional elongation or DNA replication, and they also display genetic interactions with both transcription and DNA replication mutants (Orphanides et al. 1999; Schlesinger and Formosa 2000; Formosa et al. 2001, 2002; Krogan et al. 2002; Biswas et al. 2005; Budd et al. 2005). Evidence for a role for FACT in promoting transcription includes stimulation of transcription through a chromatin barrier in vitro (Orphanides et al. 1998), physical association of yFACT with elongation factors (Krogan et al. 2002; Simic et al. 2003), binding of yFACT to transcribed regions of genes in vivo (Mason and Struhl 2003; Saunders et al. 2003), and reduced binding of TATA-binding protein (TBP) to promoters in yFACT mutants (Biswas et al. 2005). A role for yFACT in replication is suggested by several observations, including physical interaction of yFACT with DNA polymerase-α and replication protein A (Wittmeyer and Formosa 1997; Wittmeyer et al. 1999; VanDemark et al. 2006), delayed assembly of factors at a replication origin in a strain with mutations that cause reduced interaction between Pol-α and Spt16 (Zhou and Wang 2004), decreased replication in Xenopus oocyte extracts from which FACT has been depleted (Okuhara et al. 1999), and sensitivity of some yFACT mutants to the replication inhibitor hydroxyurea (HU) (Schlesinger and Formosa 2000; Formosa et al. 2001).

HU specifically blocks DNA synthesis by inhibiting ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) (Eklund et al. 2001), resulting in depletion of dNTP pools and stalled replication forks (Koc et al. 2004). A stalled replication fork triggers the DNA damage checkpoint pathway that requires the Mec1 and Rad53 kinases (homologous to human ATR and Chk2, respectively) (Nedelcheva-Veleva et al. 2006). Checkpoint activation results in stabilization of stalled replication forks, inhibition of late-origin firing, and blocking of mitosis, as well as increased expression of the RNR genes to compensate for decreased dNTP pools (Pasero et al. 2003). Yeast strains with mutations in DNA replication or checkpoint response genes often show sensitivity to HU in the growth medium (Parsons et al. 2004). Additionally, deletion of either the MEC1 or the RAD53 genes causes lethality, as these factors are absolutely essential to maintain the integrity of replication forks, even in the absence of any genotoxic or DNA replication stress (Kai and Wang 2003). Interestingly, the lethality caused by disruption of either MEC1 or RAD53 can be suppressed by a mutation in SML1, which encodes an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase (Zhao et al. 1998), as well as by overexpression of RNR1, encoding a subunit of ribonucleotide reductase (Desany et al. 1998).

We have shown that transcriptional defects caused by yFACT mutation can be suppressed by mutations in two chromatin-modifying factors, SET2 and CHD1 (Biswas et al. 2006, 2007). Set2 encodes a histone methyltransferase that methylates K36 of histone H3 (Strahl et al. 2002). Set2 is believed to play a role in transcriptional elongation, as Set2 associates with the elongating form of RNA polymerase II and modifies chromatin in transcribed regions (Krogan et al. 2003; Li et al. 2003; Xiao et al. 2003; Liu et al. 2005; Pokholok et al. 2005; Rao et al. 2005). Additionally, set2 shows genetic interactions with genes implicated in elongation (Krogan et al. 2003; Li et al. 2003; Biswas et al. 2006). CHD1 encodes an ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler (Tran et al. 2000) with a double chromodomain (Flanagan et al. 2007) and a Myb-related DNA-binding domain (Woodage et al. 1997). Like Set2, Chd1 associates with transcribed regions of genes (Simic et al. 2003) and shows physical and genetic interactions with elongation factors (Kelley et al. 1999; Tsukiyama et al. 1999; Krogan et al. 2002; Simic et al. 2003; Biswas et al. 2007). Mutations in either SET2 or CHD1 suppress a variety of transcriptional defects caused by a yFACT mutation, including temperature-sensitive growth, synthetic lethalities between yFACT mutations and mutations of other transcription factors, defects in GAL1 gene induction, and defects in binding of TBP to promoters (Biswas et al. 2006, 2007).

Because yFACT has a role in DNA replication, in this report we investigate the role of the Set2 and Chd1 chromatin-modifying factors in regulating DNA replication. yFACT mutations can cause HU sensitivity, suggesting defects in DNA replication, and this can be suppressed by disruption of either SET2 or CHD1. Our results suggest that both Set2 and Chd1 have a role opposing that of yFACT in regulating DNA replication and that Set2 and Chd1 act in two separate pathways. set2 and chd1 mutations can suppress the HU sensitivity caused by other replication mutants, and chd1 suppresses the lethality of mec1 and rad53 gene disruptions. Finally, the defect in S-phase progression caused by pob3 mutations is suppressed by set2 or chd1, suggesting that Set2 and Chd1 may directly regulate DNA replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Standard genetic methods were used for strain construction (Sherman 1991), which are listed in supplemental Table S1 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/. Cells were grown in YPD medium (Sherman 1991) at 30°, except as noted, or in synthetic complete medium (Sherman 1991) with 2% glucose and supplemented with adenine, uracil, and amino acids, as appropriate. Cell-cycle synchronization was performed by α-factor arrest and release using YM-1 medium as described (Mitra et al. 2006). RNA levels were determined with S1 nuclease protection assays as described (Bhoite and Stillman 1998; Biswas et al. 2006), using oligonucleotides listed in supplemental Table S2 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/. mRNA levels were quantitated using a Molecular Dynamics (Sunnyvale, CA) phosphorimager and ImageQuant software. Western immunoblots were performed to detect Spt16 and Pob3 (VanDemark et al. 2008) and phosphorylated Rad53 (Alcasabas et al. 2001); blots were scanned using a Li-Cor infrared scanner and quantitated using Odyssey software.

RESULTS

set2 and chd1 can suppress yFACT defects associated with DNA replication:

During DNA replication, newly deposited nucleosomes are acetylated at lysines 5 and 12 in histone H4 (Gunjan et al. 2005). While substituting these two residues for nonacetylatable arginines results in viability in an otherwise wild-type strain, the H4(K5R, K12R) mutant is lethal in yFACT mutant strains (Formosa et al. 2002; VanDemark et al. 2006), suggesting a role for yFACT in nucleosome deposition. We have previously shown that set2 and chd1 mutations can suppress transcriptional defects caused by yFACT mutants (Biswas et al. 2006, 2007), and we wondered whether deletion of SET2 or CHD1 would also suppress the DNA replication defects caused by combining a yFACT mutant and a histone H4(K5R, K12R) substitution. We constructed spt16-11 strains with the H4(K5R, K12R) mutant histone, along with either a set2 or a chd1 mutation, and analyzed growth (Figure 1A). While the spt16-11 H4(K5R, K12R) strain grows at 25°, viability is strongly decreased at 30° or higher temperatures. A chd1 mutation strongly suppresses the synthetic lethality caused by combining spt16-11 with H4(K5R, K12R), whereas set2 weakly suppresses. This suggests that these two factors act in opposition to yFACT in promoting DNA replication.

Figure 1.—

set2 and chd1 replication defects caused by yFACT mutations. (A) Tenfold dilutions of strains DY11848 (spt16-11), DY11852 (spt16-11 set2), DY11851 (spt16-11 chd1), DY11855 [spt16-11 H4(K5R, K12R)], DY11849 [spt16-11 H4(K5R, K12R) set2], and DY11853 [spt16-11 H4(K5R, K12R) chd1] were plated on complete medium for 5 days at 25° or for 3 days at either 30° or 33°. (B) Tenfold dilutions of strains DY150 (wild type), DY8690 (set2), DY6957 (chd1), DY8107 (spt16-11), DY8777 (spt16-11 set2), and DY9152 (spt16-11 chd1) were plated on complete or 50 mm HU medium for 2 days at 30°. (C) Tenfold dilutions of strains DY150 (wild type), DY8690 (set2), DY6957 (chd1), DY7379 [pob3(L78R)], DY8878 [pob3(L78R) set2], and DY9458 [pob3(L78R) chd1] were plated on complete or 50 mm HU medium for 3 days at 25°. (D) (Left) Tenfold dilutions of strains DY2860 (wild type), DY8898 (set2), DY10722 [pob3(Q308K)], and DY10723 [pob3(Q308K) set2] were plated at 30° on complete medium for 3 days or on 150 mm HU medium for 4 days. (Right) Tenfold dilutions of strains DY150 (wild type), DY9809 (chd1), DY10890 [pob3(Q308K)], and DY10897 [pob3(Q308K) chd1] were plated on complete or 50 mm HU medium for 2 days at 30°. (E) (Left) Tenfold dilutions of strains DY150 (wild type), DY8690 (set2), DY10308 [pob3(Q308K)], and DY12028 [pob3(Q308K) set2] were plated on complete medium at 30° for 2 days or at 35° for 3 days. (Right) Tenfold dilutions of strains DY150 (wild type), DY9809 (chd1), DY10890 [pob3(Q308K)], and DY10897 [pob3(Q308K) chd1] were plated on complete medium for 2 days at 30° or 35°.

HU reduces the pool of dNTPs available for DNA synthesis, resulting in reduced rates of DNA replication and increased risk of replication fork stalling and collapse. Mutations in many DNA replication genes or factors involved in the checkpoint response to DNA damage cause HU sensitivity (Parsons et al. 2004), as do some SPT16 and POB3 mutations (Schlesinger and Formosa 2000; Formosa et al. 2002; O'Donnell et al. 2004; VanDemark et al. 2006), consistent with a role for yFACT in DNA replication. On the basis of our earlier observations of suppression, we asked whether set2 or chd1 can suppress the HU sensitivity observed in spt16-11 or pob3(L78R) mutants. Deletion of either SET2 or CHD1 suppresses the HU sensitivities of both spt16-11 (Figure 1B) and pob3(L78R) (Figure 1C). We recently described pob3(Q308K), an allele that causes phenotypes suggesting defects in DNA replication (VanDemark et al. 2006). Deletion of either SET2 or CHD1 suppresses the HU sensitivity (Figure 1D), as well as the temperature sensitivity (Figure 1E), of a pob3(Q308K) mutant. Thus chd1 and set2 suppress the HU sensitivity for all three yFACT mutations tested.

It is possible that the mutations destabilized the yFACT proteins and that the chd1 or set2 mutations suppress by stabilizing the yFACT proteins. To determine protein abundance, Western immunoblots were performed and quantitated by infrared scanning (Figure 2). The Pob3(L78R) protein is inherently unstable, accumulating to only ∼20% of wild-type levels in cells grown at the permissive temperature of 25° and to somewhat lower levels at the nonpermissive temperature of 37° (Figure 2A and VanDemark et al. 2008). chd1 and set2 mutations do not result in a significant increase in Pob3(L78R) protein levels. The level of Pob3-Q308K protein is not appreciably affected by this mutation or by set2 or chd1 (Figure 2B). The spt16-11 mutation has the most severe effect, with cells grown at the nonpermissive temperature showing ∼11% of the wild-type protein level (Figure 2C). The chd1 and set2 proteins modestly suppress the instability of the Spt16-11 protein, with an approximately twofold increase in Spt16-11 protein. We conclude that chd1 and set2 mutations do not suppress the yFACT defect by stabilizing unstable proteins, particularly for the pob3(L78R) and pob3(Q308K) alleles.

Figure 2.—

chd1 and set2 mutations do not stabilize mutant yFACT proteins. Strains were grown to logarithmic phase at 25°, and the culture was split and then incubated for 3 hr at either 25° or 37°. Pob3 and Spt16 protein levels were determined by Western blotting. Identical gels stained with Coomassie blue verified equal protein loading. The blots were quantitated and normalized to the wild-type strain at that temperature. (A) The Pob3(L78R) protein has reduced abundance at both 25° and 37°. Strains DY150 (wild type), DY7379 [pob3(L78R)], DY9809 (chd1), DY9458 [pob3(L78R) chd1], DY8690 (set2), and DY8878 [pob3(L78R) set2] were used. The blot was probed with antibody to both Pob3 and Spt16, and the bottom band of the doublet in this experiment is a proteolytic fragment of Spt16. (B) The Pob3(Q308K) protein is at the same levels as wild type. Strains DY150 (wild type), DY10308 [pob3(Q308K)], DY10711 (chd1), DY10897 [pob3(Q308K) chd1], DY8795 (set2), and DY1228 [pob3(Q308K) set2] were used. In this experiment, only Pob3 was probed so both bands visualized are Pob3 protein. (C) The Spt16-11 protein has reduced abundance at 37°, but normal levels at 25°. Strains DY150 (wild type), DY8107 (spt16-11), DY10711 (chd1), DY12430 (spt16-11 chd1), DY8795 (set2), and DY8777 (spt16-11 set2) were used. The blot was probed with antibody to Spt16.

The HIR complex facilitates nucleosome assembly in vivo (Ray-Gallet et al. 2002; Green et al. 2005; Prochasson et al. 2005), and yFACT is proposed to facilitate reformation of the nucleosome following passage of either RNA or DNA polymerase (Formosa et al. 2002; Belotserkovskaya et al. 2003). Consistent with both yFACT and the HIR complex having a role in nucleosome assembly, combining a yFACT mutation with disruption of any of the four genes encoding subunits in the HIR complex causes synthetic lethality (Formosa et al. 2002). In the W303 strain background, an spt16-11 hir2 double mutant is viable, but has a marked growth defect and is more sensitive to HU than single mutants (supplemental Figure S1, A and B, at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). Importantly, disruption of either SET2 (supplemental Figure S1A) or CHD1 (supplemental Figure S1B) suppresses the HU sensitivity of the spt16-11 hir2 double mutant. HTZ1 encodes the yeast H2A.Z histone variant of H2A (Dryhurst et al. 2004), and we showed that a spt16-11 htz1 double mutant is synthetically lethal at 33° (Biswas et al. 2006). The spt16-11 htz1 strain grows reasonably well at 25°, but is quite sensitive to low levels of HU (supplemental Figure S1, C and D). This HU sensitivity is also suppressed by either a set2 (supplemental Figure S1C) or a chd1 (supplemental Figure S1D) mutation. Using HU sensitivity as a measure of a defect in DNA replication, we conclude that set2 and chd1 mutations suppress the replication defects caused by yFACT mutations.

Set2 and Chd1 are additive in suppressing HU sensitivity of yFACT mutants:

We showed that set2 and chd1 are additive in suppressing the temperature-sensitive growth defect caused by a pob3(L78R) mutation (Biswas et al. 2007). We now show that set2 and chd1 are also additive in suppressing the HU-sensitive phenotypes of both pob3(L78R) (Figure 3A) and spt16-11 (Figure 3B) mutants (growth of triple mutants in row 8 is stronger than that for either double mutant in rows 6 and 7). This additivity is consistent with the idea that Chd1 and Set2 act in different pathways to regulate yFACT-mediated DNA replication.

Figure 3.—

set2 and chd1 are additive in suppressing HU sensitivity of yFACT mutants. (A) Tenfold dilutions of strains DY150 (wild type), DY9809 (chd1), DY8690 (set2), DY9838 (chd1 set2), DY7379 [pob3(L78R)], DY9458 [pob3(L78R) chd1], DY8878 [pob3(L78R) set2], and DY9547 [pob3(L78R) chd1 set2] were plated at 25° on complete medium for 3 days or 150 mm HU medium for 6 days. (B) Tenfold dilutions of strains DY150 (wild type), DY9809 (chd1), DY8690 (set2), DY9838 (chd1 set2), DY8107 (spt16-11), DY12430 (spt16-11 chd1), DY8777 (spt16-11 set2), and DY9153 (spt16-11 chd1 set2) were plated at 30° on complete medium for 2 days or 120 mm HU medium for 4 days.

set2 and chd1 suppress replication mutants:

Because HU inhibits DNA replication, many strains with mutations in DNA replication factors are sensitive to HU (O'Donnell et al. 2004). If Set2 and Chd1 play a role in DNA replication, then set2 and chd1 might suppress the HU sensitivity caused by a mutation in a DNA replication factor. We constructed double-mutant strains with set2 and a variety of replication mutations, including cdc2-1, ctf4Δ, mcm2-1, mcm3-1, orc2-1, pol2-1, and pol1-17. For most of these mutants, set2 did not suppress. However, set2 shows strong suppression of the HU sensitivity in a cdc2-1 mutant (Figure 4A). CDC2 encodes the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase-δ. A set2 mutation shows weaker, but still significant, suppression of a ctf4 gene disruption (Figure 4B). CTF4 is required for efficient sister chromatid cohesion, and Ctf4 competes with yFACT for binding to DNA polymerase-α (Wittmeyer and Formosa 1997). We also tested whether a chd1 mutation could suppress the HU-sensitive phenotype of a number of replication mutations, including cdc2-1, mcm2-1, mcm3-1, orc2-1, and pol1-17, and found that chd1 suppresses orc2-1 but not the other mutations (Figure 4C). ORC2 encodes a subunit of the origin recognition complex, required for formation of the prereplication complex at origins. NHP10 encodes an HMG protein that is part of the Ino80 complex that participates in DNA repair (Morrison et al. 2004). In the S288C strain background, nhp10 rad55 double mutants are HU sensitive, while nhp10 single mutants are not (Morrison et al. 2004). In contrast, we find that nhp10 mutants in the W303 background are sensitive to HU and that this defect can be suppressed by set2 (Figure 4D). The fact that set2 and chd1 mutations can suppress the HU sensitivity of DNA replication mutants strongly suggests that these two chromatin factors play a role in DNA replication. Additionally, the distinct patterns of suppression by set2 and chd1 of the HU sensitivity of cdc2-1 and orc2-1 suggest that Set2 and Chd1 act through different mechanisms.

Figure 4.—

set2 and chd1 suppress HU sensitivity of DNA replication mutants. (A) Tenfold dilutions of strains DY5662 (wild type), DY10055 (set2), DY10058 (cdc2-1), and DY10097 (cdc2-1 set2) were plated at 25° on complete medium for 3 days or 100 mm HU medium for 6 days. (B) Tenfold dilutions of strains DY5662 (wild type), DY10055 (set2), DY10056 (ctf4), and DY10092 (ctf4 set2) were plated at 25° on complete medium for 2 days or 100 mm HU medium for 9 days. (C) Tenfold dilutions of strains DY150 (wild type), DY10711 (chd1), DY11082 (orc2-1), and DY11084 (orc2-1 chd1) were plated at 25° on complete medium for 2 days or 50 mm HU medium for 3 days. (D) Tenfold dilutions of strains DY150 (wild type), DY8825 (set2), DY12610 (nhp10), and DY12611 (nhp10 set2) were plated at 30° on complete medium for 2 days or 150 mm HU medium for 5 days. (E) Tenfold dilutions of strains DY150 (wild type), DY10675 (chd1), DY10665 (mec1 sml1), and DY10669 (mec1 sml1 chd1) were plated at 25° on complete medium for 2 days or 2 mm HU medium for 3 days.

The pob3(Q308K) mutation does not affect RNR gene expression:

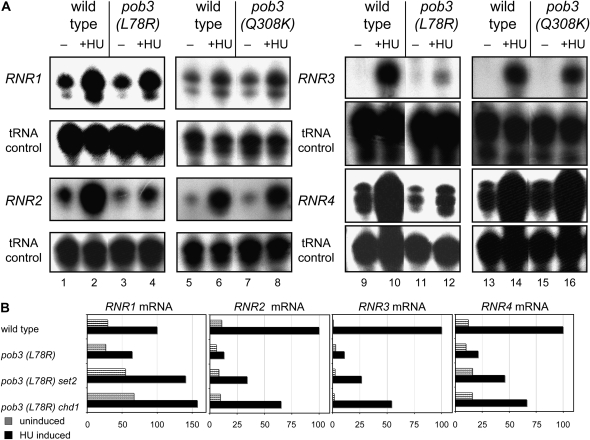

HU is an inhibitor of the ribonucleotide reductase enzyme. This inhibition results in reduced dNTP pools and collapsed replication forks (Koc et al. 2004). Cells respond by inducing expression of the DNA damage regulon, including the four RNR genes encoding ribonucleotide reductase subunits (Foiani et al. 2000). Thus, a mutant might display HU sensitivity because of a defect in RNR gene induction, instead of a direct defect in DNA replication. To test this explanation we grew wild-type, pob3(L78R), and pob3(Q308K) cells for 2 hr in the presence of 100 mm HU and compared the mRNA levels for the four RNR genes before and after induction (Figure 5A). In wild-type strains gene induction ranged from 3-fold for RNR1 to nearly 200-fold for RNR3. The pob3(L78R) mutant showed significantly reduced ability to induce expression of RNR2, RNR3, and RNR4 and a modest defect for RNR1. Interestingly this transcriptional defect was partially suppressed by mutation of either SET2 or CHD1 (supplemental Figure S2 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/, Figure 5B). In contrast, the pob3(Q308K) mutant showed normal induction of all four RNR genes (Figure 5A). This result shows that HU sensitivity can be caused by a yFACT mutation that supports normal transcriptional induction of the RNR genes. This indicates that at least this yFACT mutant is defective directly in some aspect of DNA replication, so suppression of this allele cannot be an indirect effect of a change in RNR gene transcription.

Figure 5.—

RNR gene expression in pob3(L78R) and pob3(Q308K) mutants. (A) Strains DY150 (wild type) and DY7379 [pob3(L78R)] were grown at 25° in YPAD medium to OD600 = 0.6, before a preinduction sample (“−”) was taken, and then HU was added to a concentration of 100 mm, and cultures were grown for an additional 2 hr before the postinduction sample (“+ HU”) was taken. Strains DY10641 (wild type) and DY10642 [pob3(Q308K)] were grown identically, expect at 30°. RNA was isolated from the samples and expression of RNR1, RNR2, RNR3, and RNR4 was determined by S1 nuclease protection, with tRNA serving as an internal control. (B) Graphs of RNR gene expression before and after HU induction using the quantitation from the S1 protection assay in supplemental Figure S2.

Mutations in PAF1, a component of the PAF transcriptional elongation complex, result in HU sensitivity (Betz et al. 2002). The paf1 mutants show reduced expression of RNR1, and a multicopy plasmid with RNR1 suppresses the HU sensitivity. On the basis of this result, we tested whether a multicopy plasmid with RNR1 would suppress the HU sensitivity of the spt16-11 and pob3(L78R) mutants; however, the HU sensitivity of neither mutant was suppressed by YEp-RNR1 (data not shown). SML1 encodes an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase (Zhao et al. 1998). We therefore tested whether deletion of SML1 would suppress the HU sensitivity of yFACT mutants. spt16-11 sml1, pob3(L78R) sml1, and pob3(Q308K) sml1 double-mutant strains showed the same HU sensitivity as the spt16-11, pob3(L78R), and pob3(Q308K) single mutants (data not shown), and we conclude that deletion of SML1 does not suppress the HU sensitivity of yFACT mutants.

In summary, our results show that the HU sensitivity of the pob3(Q308K) mutant does not result from a defect in transcriptional induction of RNR genes and the HU sensitivity caused by other yFACT mutants cannot be rescued by increasing RNR activity. The suppression of this HU sensitivity phenotype by set2 and chd1 therefore suggests that these two factors act directly in opposition to yFACT in a pathway specific to DNA replication.

Deletion of CHD1 bypasses the mec1 and rad53 checkpoints:

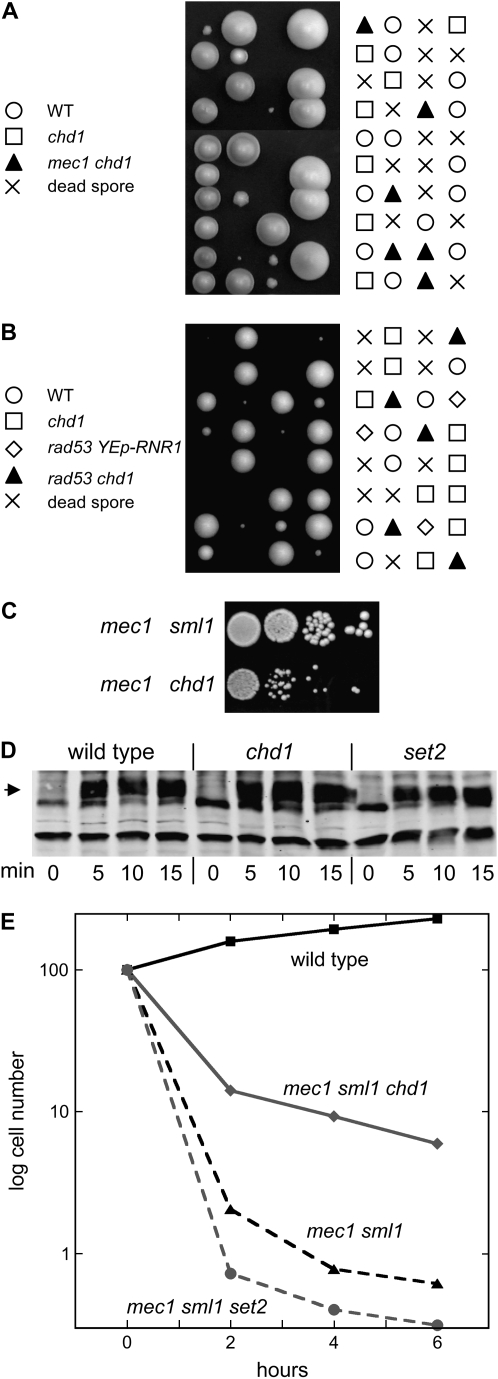

Cells exposed to DNA-damaging agents activate the Mec1 protein kinase, resulting in cell-cycle arrest and transcriptional activation of targets such as the RNR genes. MEC1 is essential for viability, but a mec1 sml1 double mutant is viable (Zhao et al. 1998) but very sensitive to HU. Importantly, this HU sensitivity is suppressed by a chd1 mutation (Figure 4E). On the basis of this result, we wondered whether set2 or chd1 mutations could suppress the lethality of a mec1 null mutant. A mec1 sml1 strain was mated to either a chd1 or a set2 strain, the diploid was sporulated, and tetrads were dissected. A set2 mutation failed to allow viability of a mec1 SML1 strain (data not shown). However, mec1 chd1 SML1 spores are viable, although slow growing (Figure 6A). The Rad53 kinase functions downstream of Mec1, and RAD53 is also essential for viability. A cross shows that a CHD1 gene disruption also suppresses the lethality of a rad53 strain (Figure 6B). A comparison of colony sizes indicates that chd1 does not suppress mec1 as strongly as sml1 does (Figure 6C). HU exposure activates the Mec1 kinase, resulting in phosphorylation of Rad53 (Alcasabas et al. 2001). We find that set2 or chd1 mutations affect neither the degree of Rad53 phosphorylation in response to HU nor the kinetics of appearance of activated Rad53 (Figure 6D). We conclude that Chd1 functions in a pathway unrelated to or downstream of Rad53.

Figure 6.—

Deletion of CHD1 bypasses the MEC1 checkpoint. (A) DY6958 (chd1∷LEU2) was crossed to DY10112 (mec1∷TRP1 sml1∷HIS3), yielding DY10671 (mec1∷TRP1 chd1∷LEU2 SML1). DY10671 was then mated to wild-type strain DY1868, and haploid progeny are shown after 7 days of growth at 25°. Symbols indicate selected genotypes. (B) Strains DY9809 (chd1∷TRP1) and DY10689 (rad53∷HIS3 YEp-LEU2-RNR1) were mated and the haploid progeny from sporulating that diploid are shown after 5 days of growth. rad53 is lethal, but lethality can be suppressed by a multicopy plasmid with RNR1 (Desany et al. 1998). Viable rad53 chd1 strains were recovered both with and without the YEp-LEU2-RNR1 plasmid, and the presence or the absence of the YEp-LEU2-RNR1 plasmid did not affect the growth rate of the rad53 chd1 strains. Symbols indicate selected genotypes. (C) Tenfold dilutions of strains DY10112 (mec1 CHD1 sml1) and DY10671 (mec1 chd1 SML1) were plated on complete medium at 25° for 3 days. (D) Strains DY150 (wild type), DY9809 (chd1), and DY8690 (set2) were grown to logarithmic phase at 30° and HU was added to a concentration of 200 mm. Samples were taken before HU addition, and at 5-min intervals after, and examined on immunoblots probed with antibody to Rad53. Identical gels stained with Coomassie blue verified equal protein loading. The arrowhead indicates the position of phosphorylated Rad53. (E) HU (10 mm final concentration) was added to cultures of strains DY150 (wild type), DY10670 (mec1 sml1 chd1), DY10148 (mec1 sml1), and DY10150 (mec1 sml1 set2) growing at 30°, and at the indicated times samples were taken. Cells were sonicated and washed with water once before plating to determine the fraction of viable cells. The experiment was also conducted with sml1, sml1 chd1, and sml1 set2 strains, and the results were similar to that seen for wild type.

Mec1 is required for maintenance of replication fork integrity (Cha and Kleckner 2002), and we wanted to investigate whether a chd1 mutation could suppress replication fork instability caused by a mec1 mutation. A brief exposure (2–4 hr) of mec1 sml1 mutants to 10 mm HU results in >100-fold loss in viability (Figure 6E), suggesting that maintenance of replication fork integrity by Mec1 is absolutely essential for cell viability. The mec1 sml1 set2 triple mutant shows greater inviability after exposure to HU, while a chd1 mutation suppresses the mec1 sml1 lethality by 10-fold. The opposite effects of the set2 and chd1 mutations in this assay support the idea that Set2 and Chd1 function in different pathways. Exposure of mec1 sml1 mutants to HU results in replication fork collapse and cell death (Lopes et al. 2001; Tercero and Diffley 2001), and suppression of this lethality by a CHD1 gene disruption supports the idea that Chd1 has a negative role in replication fork stabilization.

chd1 and set2 restore S-phase progression to a pob3 mutant:

pob3(L78R) mutants are defective for progression through S phase at the nonpermissive temperature (Schlesinger and Formosa 2000), and we wanted to determine whether chd1 or set2 mutants would suppress this defect. Cells were treated with α-factor to arrest in G1 and then released from the block into media at the permissive temperature of 25°, and at various time points after the release DNA content was determined by flow cytometry (Figure 7A). With this protocol most wild-type cells have completed replication by 30 min, and all have by 40 min. In contrast, the pob3(L78R) mutant has a severe defect in S-phase progression, with few cells having replicated their DNA by 50 min. The set2 and chd1 mutations suppress the pob3(L78R) defect in progressing through S phase, with many cells having replicated their genomes at 30–40 min following release from α-factor arrest (Figure 7A). A similar experiment was conducted with the pob3(Q308K) mutant, except that cells were released from the α-factor arrest at the semipermissive temperature of 34°. The pob3(Q308K) mutation has a much more severe effect on DNA replication than pob3(L78R), consistent with the previously described phenotypes (VanDemark et al. 2006); many of the cells are still in S phase 60 min after the release (Figure 7B). The set2 and chd1 mutations also suppress the pob3(Q308K) defect in S-phase progression, with a majority of cells having completed replication within 50 min following release. These results clearly demonstrate negative roles for Chd1 and Set2 in S-phase progression.

Figure 7.—

set2 and chd1 suppress the pob3 defect in S-phase progression. (A) Wild-type (DY150), pob3(L78R) (DY7379), pob3(L78R) chd1 (DY9458), and pob3(L78R) set2 (DY8878) cells were grown to log phase at 25°, arrested with α-factor for 2.5 hr, and released from the arrest by resuspending in fresh media containing protease at 25°. Samples were taken at 10-min intervals and DNA content was determined by flow cytometry. The 1C and 2C positions are indicated. (B) The same as in A, except cells released from the α-factor arrest at 34°. Strains DY150 (wild type), DY10308 [pob3(Q308K)], DY10897 [pob3(Q308K) chd1], and DY12028 [pob3(Q308K) set2] were used.

DISCUSSION

Replication of the genome is carefully regulated to ensure that each chromosome is duplicated once and only once. Problems at the replication fork can cause collapse of the fork, resulting in chromosome breaks, and the checkpoint machinery monitors both the replication fork and DNA integrity (Cha and Kleckner 2002). The yFACT chromatin-reorganizing complex binds to DNA polymerase-α and replication protein A, and both genetic and biochemical studies suggest that yFACT promotes DNA replication. We have shown that gene disruptions affecting either the Set2 histone methyltransferase or the Chd1 chromatin-remodeling complex can suppress replication-defective phenotypes, particularly the sensitivity to the HU-replication inhibitor, caused by mutations in yFACT, MEC1, or other replication factors. Additionally, pob3 mutants have a marked defect in progressing through S phase, and this defect is effectively suppressed by mutations in either SET2 or CHD1. These observations suggest that Set2 and Chd1 have negative roles in regulating DNA replication and that part of the function of yFACT is to overcome these barriers.

While the Set1 and Dot1 methyltransferases that modify H3(K4) and H3(K79), respectively, have been shown to have roles in DNA replication and repair (Corda et al. 1999; Schramke et al. 2001; Sollier et al. 2004; Wysocki et al. 2005; Bostelman et al. 2007), a role for the Set2 H3(K36) methyltransferase in replication has not been previously demonstrated. Similarly, the Ino80 and Swr1 ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling factors play important roles in repairing DNA breaks (Van Attikum and Gasser 2005; Bao and Shen 2007), but Chd1 has not been previously implicated in either DNA replication or repair. Our results provide the first evidence for a negative role for Set2 and Chd1 in regulating DNA replication. It is not clear how set2 and chd1 suppress the HU sensitivity of yFACT mutants. One possibility is that these factors have a negative role in regulating the yFACT-mediated recruitment of DNA replication factors that stabilize the replication fork and prevent fork collapse.

HU specifically blocks DNA synthesis by inhibiting RNR, resulting in depletion of dNTP pools and stalling of replication forks (Eklund et al. 2001; Koc et al. 2004). In reaction to the stalled replication forks the Mec1-Rad53 checkpoint kinase cascade is activated, and one response is transcriptional induction of the RNR genes. We show that Set2 and Chd1 function downstream of Rad53 phosphorylation and that that there is no defect in RNR gene transcription in a pob3(Q308K) strain in response to HU exposure. Thus, the HU sensitivity does not originate from defective transcriptional induction of RNR genes. Additionally, expression of RNR genes is not altered in chd1 or set2 mutant strains. Activity of the RNR enzymes is inhibited by the Sml1 protein, and sml1 mutations can suppress mutations in the replication checkpoint pathway (Zhao et al. 1998). We therefore considered the possibility that altered transcriptional regulation of SML1 could result in the HU sensitivity of yFACT mutants or the suppression by set2 and chd1. Two experiments argue against this possibility. First, spt16-11, pob3(L78R), and pob3(Q308K) strains showed the same HU sensitivity whether the strain was SML1+ or sml1−. Second, a chd1 mutation suppresses the sensitivity of a mec1 mutant to HU despite the absence of SML1. Additionally, overexpression of RNR1 can suppress replication defects similar to an SML1 gene disruption (Desany et al. 1998), but RNR1 overexpression does not suppress yFACT defects. We conclude that the effects of yFACT, set2, and chd1 mutations on HU sensitivity are independent of SML1.

Because of its dual role in transcription as well as replication, it is possible that the suppressive effects of set2 and chd1 mutations on yFACT replication defects are indirect, via transcriptional effects. If Set2 and Chd1 do play roles in regulating DNA replication, we would expect set2 and chd1 mutations to suppress replication defects caused by mutations in factors strictly involved in DNA replication. We find that a SET2 deletion suppresses the HU sensitivity of cdc2-1 and ctf4 mutations and a CHD1 deletion suppresses the HU sensitivity in orc2-1 and mec1 sml1 strains. CDC2 encodes the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase-δ, CTF4 is required for efficient sister chromatid cohesion (Hanna et al. 2001) and competes with yFACT for binding to DNA polymerase-α (Wittmeyer and Formosa 1997), ORC2 encodes a subunit of the origin recognition complex (Da-Silva and Duncker 2007), and MEC1 encodes the checkpoint kinase that monitors replication fork integrity (Nedelcheva-Veleva et al. 2006). Suppression of these replication-defective mutations by set2 and chd1 strongly implies that these chromatin-modifying factors have specific roles in negatively regulating DNA replication. The MEC1 and RAD53 checkpoint genes are normally essential for viability, but this can be suppressed by deletion of CHD1. Finally, pob3 mutants are defective for progression through S phase, but this defect can be suppressed by chd1 or set2 mutations. These results provide strong support for Chd1 and Set2 in negatively regulating DNA replication.

Mutations in CHD1 and SET2 can result in different phenotypes, and chd1 and set2 are additive in terms of suppressing yFACT growth defects on HU (Figure 3). yFACT mutations cause Spt− phenotypes, suppression of the histidine and lysine auxotrophies of strains with the his4-912δ and lys2-128δ alleles (Malone et al. 1991; Schlesinger and Formosa 2000). A chd1 mutation reverses the Spt− phenotypes caused by yFACT mutations, while set2 does not (supplemental Figure S3 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/), demonstrating a difference between CHD1 and SET2. The failure of a set2 mutation to affect expression of the his4-912δ and lys2-128δ alleles is surprising, as many spt mutants were shown to activate expression from “cryptic” TATA elements within open reading frames (Kaplan et al. 2003), and set2 mutants also activate these cryptic TATA elements (Carrozza et al. 2005). The Sin3/Rpd3 histone deacetylase complex functions with Set2 to prevent expression from these cryptic TATA elements (Carrozza et al. 2005; Joshi and Struhl 2005; Keogh et al. 2005), and a sin3 mutation neither causes an Spt− phenotype nor affects the Spt− phenotype of a pob3(Q308K) strain (supplemental Figure S3). We conclude that assays of RNA from cryptic promoters and the Spt− phenotype are not measuring the same phenomenon.

Chromodomains often bind methylated lysine residues (Daniel et al. 2005), and one might expect Chd1 and Set2 to function in the same pathway, with Chd1 binding to H3(K36) methylated by Set2. However, structural work on yeast Chd1 suggests that it does not bind methylated lysines (Flanagan et al. 2007). We believe that Set2 and Chd1 function in separate pathways, as the two mutations show additivity in suppressing the HU-sensitive phenotypes of yFACT mutants and had different or even opposite effects in assays described here. Further experimental work is needed to decipher the mechanisms by which Set2 and Chd1 regulate DNA replication.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jasper Rine and Rodney Rothstein for providing strains, John Diffley for providing Rad53 antibodies, and Craig Kaplan for discussions. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Alcasabas, A. A., A. J. Osborn, J. Bachant, F. Hu, P. J. Werler et al., 2001. Mrc1 transduces signals of DNA replication stress to activate Rad53. Nat. Cell Biol. 3 958–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Y., and X. Shen, 2007. Chromatin remodeling in DNA double-strand break repair. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 17 126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belotserkovskaya, R., S. Oh, V. A. Bondarenko, G. Orphanides, V. M. Studitsky et al., 2003. FACT facilitates transcription-dependent nucleosome alteration. Science 301 1090–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger, S. L., 2007. The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature 447 407–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz, J. L., M. Chang, T. M. Washburn, S. E. Porter, C. L. Mueller et al., 2002. Phenotypic analysis of Paf1/RNA polymerase II complex mutations reveals connections to cell cycle regulation, protein synthesis, and lipid and nucleic acid metabolism. Mol. Genet. Genomics 268 272–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhoite, L. T., and D. J. Stillman, 1998. Residues in the Swi5 zinc finger protein that mediate cooperative DNA-binding with the Pho2 homeodomain protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 6436–6446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, D., Y. Yu, M. Prall, T. Formosa and D. J. Stillman, 2005. The yeast FACT complex has a role in transcriptional initiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25 5812–5822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, D., R. Dutta-Biswas, D. Mitra, Y. Shibata, B. D. Strahl et al., 2006. Opposing roles for Set2 and yFACT in regulating TBP binding at promoters. EMBO J. 25 4479–4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, D., R. Dutta-Biswas and D. J. Stillman, 2007. Chd1 and yFACT act in opposition in regulating transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27 6279–6287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostelman, L. J., A. M. Keller, A. M. Albrecht, A. Arat and J. S. Thompson, 2007. Methylation of histone H3 lysine-79 by Dot1p plays multiple roles in the response to UV damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair 6 383–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster, N. K., G. C. Johnston and R. A. Singer, 2001. A bipartite yeast SSRP1 analog comprised of Pob3 and Nhp6 proteins modulates transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 3491–3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd, M. E., A. H. Tong, P. Polaczek, X. Peng, C. Boone et al., 2005. A network of multi-tasking proteins at the DNA replication fork preserves genome stability. PLoS Genet. 1 e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, B. R., 2005. Chromatin remodeling complexes: strength in diversity, precision through specialization. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15 185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrozza, M. J., B. Li, L. Florens, T. Suganuma, S. K. Swanson et al., 2005. Histone H3 methylation by Set2 directs deacetylation of coding regions by Rpd3S to suppress spurious intragenic transcription. Cell 123 581–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha, R. S., and N. Kleckner, 2002. ATR homolog Mec1 promotes fork progression, thus averting breaks in replication slow zones. Science 297 602–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corda, Y., V. Schramke, M. P. Longhese, T. Smokvina, V. Paciotti et al., 1999. Interaction between Set1p and checkpoint protein Mec3p in DNA repair and telomere functions. Nat. Genet. 21 204–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da-Silva, L. F., and B. P. Duncker, 2007. ORC function in late G1: maintaining the license for DNA replication. Cell Cycle 6 128–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, J. A., M. G. Pray-Grant and P. A. Grant, 2005. Effector proteins for methylated histones: an expanding family. Cell Cycle 4 919–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desany, B. A., A. A. Alcasabas, J. B. Bachant and S. J. Elledge, 1998. Recovery from DNA replicational stress is the essential function of the S-phase checkpoint pathway. Genes Dev. 12 2956–2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryhurst, D., A. A. Thambirajah and J. Ausio, 2004. New twists on H2A.Z: a histone variant with a controversial structural and functional past. Biochem. Cell Biol. 82 490–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund, H., U. Uhlin, M. Farnegardh, D. T. Logan and P. Nordlund, 2001. Structure and function of the radical enzyme ribonucleotide reductase. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 77 177–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, J. F., B. J. Blus, D. Kim, K. L. Clines, F. Rastinejad et al., 2007. Molecular implications of evolutionary differences in CHD double chromodomains. J. Mol. Biol. 369 334–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foiani, M., A. Pellicioli, M. Lopes, C. Lucca, M. Ferrari et al., 2000. DNA damage checkpoints and DNA replication controls in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. 451 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formosa, T., 2003. Changing the DNA landscape: putting a SPN on chromatin. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 274 171–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formosa, T., P. Eriksson, J. Wittmeyer, J. Ginn, Y. Yu et al., 2001. Spt16-Pob3 and the HMG protein Nhp6 combine to form the nucleosome-binding factor SPN. EMBO J. 20 3506–3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formosa, T., S. Ruone, M. D. Adams, A. E. Olsen, P. Eriksson et al., 2002. Defects in SPT16 or POB3 (yFACT) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cause dependence on the Hir/Hpc pathway: polymerase passage may degrade chromatin structure. Genetics 162 1557–1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, E. M., A. J. Antczak, A. O. Bailey, A. A. Franco, K. J. Wu et al., 2005. Replication-independent histone deposition by the HIR complex and Asf1. Curr. Biol. 15 2044–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunjan, A., J. Paik and A. Verreault, 2005. Regulation of histone synthesis and nucleosome assembly. Biochimie 87 625–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, J. S., E. S. Kroll, V. Lundblad and F. A. Spencer, 2001. Saccharomyces cerevisiae CTF18 and CTF4 are required for sister chromatid cohesion. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 3144–3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, A. A., and K. Struhl, 2005. Eaf3 chromodomain interaction with methylated H3–K36 links histone deacetylation to Pol II elongation. Mol. Cell 20 971–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai, M., and T. S. Wang, 2003. Checkpoint responses to replication stalling: inducing tolerance and preventing mutagenesis. Mutat. Res. 532 59–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, C. D., L. Laprade and F. Winston, 2003. Transcription elongation factors repress transcription initiation from cryptic sites. Science 301 1096–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, D. E., D. G. Stokes and R. P. Perry, 1999. CHD1 interacts with SSRP1 and depends on both its chromodomain and its ATPase/helicase-like domain for proper association with chromatin. Chromosoma 108 10–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keogh, M. C., S. K. Kurdistani, S. A. Morris, S. H. Ahn, V. Podolny et al., 2005. Cotranscriptional set2 methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 recruits a repressive Rpd3 complex. Cell 123 593–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koc, A., L. J. Wheeler, C. K. Mathews and G. F. Merrill, 2004. Hydroxyurea arrests DNA replication by a mechanism that preserves basal dNTP pools. J. Biol. Chem. 279 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan, N. J., M. Kim, S. H. Ahn, G. Zhong, M. S. Kobor et al., 2002. RNA polymerase II elongation factors of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a targeted proteomics approach. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 6979–6992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan, N. J., M. Kim, A. Tong, A. Golshani, G. Cagney et al., 2003. Methylation of histone H3 by Set2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is linked to transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 4207–4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, B., L. Howe, S. Anderson, J. R. Yates, 3rd and J. L. Workman, 2003. The Set2 histone methyltransferase functions through the phosphorylated carboxyl-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 278 8897–8903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. L., T. Kaplan, M. Kim, S. Buratowski, S. L. Schreiber et al., 2005. Single-nucleosome mapping of histone modifications in S. cerevisiae. PLoS Biol. 3 e328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, M., C. Cotta-Ramusino, A. Pellicioli, G. Liberi, P. Plevani et al., 2001. The DNA replication checkpoint response stabilizes stalled replication forks. Nature 412 557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone, E. A., C. D. Clark, A. Chiang and F. Winston, 1991. Mutations in SPT68/CDC68 suppress cis- and trans-acting mutations that affect promoter function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11 5710–5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, P. B., and K. Struhl, 2003. The FACT complex travels with elongating RNA polymerase II and is important for the fidelity of transcriptional initiation in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 8323–8333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, D., E. J. Parnell, J. W. Landon, Y. Yu and D. J. Stillman, 2006. SWI/SNF binding to the HO promoter requires histone acetylation and stimulates TATA-binding protein recruitment. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26 4095–4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, A. J., J. Highland, N. J. Krogan, A. Arbel-Eden, J. F. Greenblatt et al., 2004. INO80 and gamma-H2AX interaction links ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling to DNA damage repair. Cell 119 767–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedelcheva-Veleva, M. N., D. B. Krastev and S. S. Stoynov, 2006. Coordination of DNA synthesis and replicative unwinding by the S-phase checkpoint pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 34 4138–4146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell, A. F., N. K. Brewster, J. Kurniawan, L. V. Minard, G. C. Johnston et al., 2004. Domain organization of the yeast histone chaperone FACT: the conserved N-terminal domain of FACT subunit Spt16 mediates recovery from replication stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 5894–5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuhara, K., K. Ohta, H. Seo, M. Shioda, T. Yamada et al., 1999. A DNA unwinding factor involved in DNA replication in cell-free extracts of Xenopus eggs. Curr. Biol. 9 341–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orphanides, G., G. LeRoy, C. H. Chang, D. S. Luse and D. Reinberg, 1998. FACT, a factor that facilitates transcript elongation through nucleosomes. Cell 92 105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orphanides, G., W. H. Wu, W. S. Lane, M. Hampsey and D. Reinberg, 1999. The chromatin-specific transcription elongation factor FACT comprises human SPT16 and SSRP1 proteins. Nature 400 284–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, A. B., R. L. Brost, H. Ding, Z. Li, C. Zhang et al., 2004. Integration of chemical-genetic and genetic interaction data links bioactive compounds to cellular target pathways. Nat. Biotechnol. 22 62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasero, P., K. Shimada and B. P. Duncker, 2003. Multiple roles of replication forks in S phase checkpoints: sensors, effectors and targets. Cell Cycle 2 568–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokholok, D. K., C. T. Harbison, S. Levine, M. Cole, N. M. Hannett et al., 2005. Genome-wide map of nucleosome acetylation and methylation in yeast. Cell 122 517–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochasson, P., L. Florens, S. K. Swanson, M. P. Washburn and J. L. Workman, 2005. The HIR corepressor complex binds to nucleosomes generating a distinct protein/DNA complex resistant to remodeling by SWI/SNF. Genes Dev. 19 2534–2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao, B., Y. Shibata, B. D. Strahl and J. D. Lieb, 2005. Dimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 36 demarcates regulatory and nonregulatory chromatin genome-wide. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25 9447–9459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray-Gallet, D., J. P. Quivy, C. Scamps, E. M. Martini, M. Lipinski et al., 2002. HIRA is critical for a nucleosome assembly pathway independent of DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell 9 1091–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades, A. R., S. Ruone and T. Formosa, 2004. Structural features of nucleosomes reorganized by yeast FACT and its HMG box component, Nhp6. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 3907–3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, A., R. A. Singer and J. C. Johnston, 1991. CDC68, a yeast gene that affects regulation of cell proliferation and transcription, encodes a protein with a highly acidic carboxyl terminus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11 5718–5726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, A., J. Werner, E. D. Andrulis, T. Nakayama, S. Hirose et al., 2003. Tracking FACT and the RNA polymerase II elongation complex through chromatin in vivo. Science 301 1094–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger, M. B., and T. Formosa, 2000. POB3 is required for both transcription and replication in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 155 1593–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramke, V., H. Neecke, V. Brevet, Y. Corda, G. Lucchini et al., 2001. The set1Δ mutation unveils a novel signaling pathway relayed by the Rad53-dependent hyperphosphorylation of replication protein A that leads to transcriptional activation of repair genes. Genes Dev. 15 1845–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, F., 1991. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 194 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simic, R., D. L. Lindstrom, H. G. Tran, K. L. Roinick, P. J. Costa et al., 2003. Chromatin remodeling protein Chd1 interacts with transcription elongation factors and localizes to transcribed genes. EMBO J. 22 1846–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollier, J., W. Lin, C. Soustelle, K. Suhre, A. Nicolas et al., 2004. Set1 is required for meiotic S-phase onset, double-strand break formation and middle gene expression. EMBO J. 23 1957–1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl, B. D., P. A. Grant, S. D. Briggs, Z. W. Sun, J. R. Bone et al., 2002. Set2 is a nucleosomal histone H3-selective methyltransferase that mediates transcriptional repression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 1298–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tercero, J. A., and J. F. Diffley, 2001. Regulation of DNA replication fork progression through damaged DNA by the Mec1/Rad53 checkpoint. Nature 412 553–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran, H. G., D. J. Steger, V. R. Iyer and A. D. Johnson, 2000. The chromo domain protein chd1p from budding yeast is an ATP-dependent chromatin-modifying factor. EMBO J. 19 2323–2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiyama, T., J. Palmer, C. C. Landel, J. Shiloach and C. Wu, 1999. Characterization of the imitation switch subfamily of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 13 686–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Attikum, H., and S. M. Gasser, 2005. The histone code at DNA breaks: A guide to repair? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6 757–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanDemark, A. P., M. Blanksma, E. Ferris, A. Heroux, C. P. Hill et al., 2006. The structure of the yFACT Pob3-M domain, its interaction with the DNA replication factor RPA, and a potential role in nucleosome deposition. Mol. Cell 22 363–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanDemark, A. P., X. Xin, L. McCullough, R. Rawlins, S. Bentley et al., 2008. Structural and functional analysis of the Spt16p N-terminal domain reveals overlapping roles of yFACT subunits. J. Biol. Chem. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wittmeyer, J., and T. Formosa, 1997. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase alpha catalytic subunit interacts with Cdc68/Spt16 and with Pob3, a protein similar to an HMG1-like protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 4178–4190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmeyer, J., L. Joss and T. Formosa, 1999. Spt16 and Pob3 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae form an essential, abundant heterodimer that is nuclear, chromatin-associated, and copurifies with DNA polymerase alpha. Biochemistry 38 8961–8971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodage, T., M. A. Basrai, A. D. Baxevanis, P. Hieter and F. S. Collins, 1997. Characterization of the CHD family of proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94 11472–11477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki, R., A. Javaheri, S. Allard, F. Sha, J. Cote et al., 2005. Role of Dot1-dependent histone H3 methylation in G1 and S phase DNA damage checkpoint functions of Rad9. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25 8430–8443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, T., H. Hall, K. O. Kizer, Y. Shibata, M. C. Hall et al., 2003. Phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II CTD regulates H3 methylation in yeast. Genes Dev. 17 654–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X., E. G. Muller and R. Rothstein, 1998. A suppressor of two essential checkpoint genes identifies a novel protein that negatively affects dNTP pools. Mol. Cell 2 329–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y., and T. S. Wang, 2004. A coordinated temporal interplay of nucleosome reorganization factor, sister chromatin cohesion factor, and DNA polymerase alpha facilitates DNA replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 9568–9579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]