Abstract

Streptococcus mutans belongs to the viridans group of oral streptococci, which is the leading cause of endocarditis in humans. The LraI family of lipoproteins in viridans group streptococci and other bacteria have been shown to function as virulence factors, adhesins, or ABC-type metal transporters. We previously reported the identification of the S. mutans LraI operon, sloABCR, which encodes components of a putative metal uptake system composed of SloA, an ATP-binding protein, SloB, an integral membrane protein, and SloC, a solute-binding lipoprotein, as well as a metal-dependent regulator, SloR. We report here the functional analysis of this operon. By Western blotting, addition of Mn to the growth medium repressed SloC expression in a wild-type strain but not in a sloR mutant. Other metals tested had little effect. Cells were also tested for aerobic growth in media stripped of metals then reconstituted with Mg and either Mn or Fe. Fe at 10 μM supported growth of the wild-type strain but not of a sloA or sloC mutant. Mn at 0.1 μM supported growth of the wild-type strain and sloR mutant but not of sloA or sloC mutants. The combined results suggest that the SloABC proteins transport both metals, although the SloR protein represses this system only in response to Mn. These conclusions are supported by 55Fe uptake studies with Mn as a competitor. Finally, a sloA mutant demonstrated loss of virulence in a rat model of endocarditis, suggesting that metal transport is required for endocarditis pathogenesis.

Streptococcus mutans is a gram-positive aerotolerant anaerobe residing in the oral cavity. S. mutans uses host dietary sucrose as well as other carbon sources for cellular energy requirements. It does not possess cytochromes and generates energy via glycolysis, liberating mixed acids as fermentation products (23). This acid production contributes to smooth-surface dental caries pathogenesis by S. mutans (23). The viridans group streptococci, including S. mutans, also cause human endocarditis, accounting for 45 to 80% of all cases involving native valves (5, 65).

Infective endocarditis is a life-threatening endovascular infection believed to occur when bacteria in the bloodstream adhere to previously damaged heart valves (16). Endocarditis causes substantial morbidity and mortality despite improvements in medical and surgical treatment (16). Prevention efforts are confined to antibiotic prophylaxis for invasive dental or surgical procedures that are likely to produce bacteremia (13). Although currently recommended by the American Heart Association (13), the merit of antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures has been much debated (1, 54, 57, 60). A vaccine would be a preferable prophylactic for many reasons (4). Recent vaccine efforts have focused on the FimA protein, an LraI (lipoprotein receptor antigen I) protein from Streptococcus parasanguis (35, 66).

LraI family proteins were initially recognized in oral streptococci and have been identified in other bacteria (31, 34, 61). This family has since been extended (11). These proteins have several common features. The LraI genes are the constituents of operons encoding ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transport systems. In gram-positive bacteria, the basic components of these operons are genes for an ATP-binding protein (ATPB), an integral membrane protein (IMP), and an LraI protein (11, 18, 24). The LraI proteins have homology to the periplasmic substrate-binding proteins of gram-negative bacterial ABC transport systems and have been proposed to possess transporter functions (2, 15, 21). In addition, adhesin functions of LraI proteins have been demonstrated in Streptococcus sanguis (SsaB) (20), Streptococcus gordonii (ScaA) (37), S. parasanguis (FimA) (50), and Streptococcus agalactiae (Lmb) (59). However, in a recent reevaluation, inactivation of the sca genes has been observed to have no effect on coaggregation with Actinomyces naeslundii (28). Lmb has been shown to be required for adherence to human laminin, but a typical ABC transporter has not been found in the nucleotide sequence adjacent to the lmb locus (19, 59), and the addition of manganese did not affect the growth of an Lmb mutant (19, 59). These studies suggest that LraI proteins may possess adhesin or metal transporter functions or both.

In our previous study (34), an LraI family operon, sloABCR, was characterized in S. mutans, and it was proposed that the sloABC genes encode the ATP-binding protein, integral membrane protein, and solute-binding lipoprotein, respectively, of a high-affinity Mn transport system. This hypothesis was based on the homology of these genes to LraI operons, such as the scaBCA system in S. gordonii, which has been shown to encode an Mn transport system (36). We also proposed that SloR functions as a metal-dependent regulator based on its homology to MntR homologs in other gram-positive bacteria (25, 28, 32, 51-53). It was therefore surprising when Spatafora et al. (58) working with another S. mutans strain reported that the sloABC genes (renamed ORF1, ORF2, and fimA) encode an Fe transport system and that SloR (renamed Dlg) functions as an Fe-dependent repressor for these genes.

In this study, we report the functional characterization of the sloABC genes in S. mutans V403 and their manganese-dependent regulation by SloR. We also further define the role of the operon in endocarditis virulence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. V403 is a fructan-hyperproducing, cariogenic strain of S. mutans (33, 45, 48, 56) originally isolated from human blood. Escherichia coli DH5α (Bethesda Research Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) was used for cloning, and cultures were routinely grown at 37°C shaking in Terrific broth (TB) (62). Erythromycin was added at 300 μg/ml, and kanamycin was added at 50 μg/ml as needed for plasmid selection. S. mutans was grown in anaerobic conditions at 37°C without shaking in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco, Inc., Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 1.5% agar for growth on plates, unless otherwise indicated. Erythromycin was included at 10 μg/ml and kanamycin was included at 100 μg/ml for streptococcal transformant selection. Genetic transformation was performed as previously described by Lindler and Macrina (39).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| S. mutans strain or plasmid | Genotype or phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| V403 | Human blood isolate, fructan-hyperproducing, cariogenic strain | 33, 46, 48, 56 |

| V2613 | ΔsloC1, derived from V403 | 34 |

| V2643 | Kanr, ΔsloR1::aphA-3, derived from V403 | This study |

| JFP14 | Kanr, sloA1::aphA-3, derived from V403 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pVA2570 | Apr; 7.63 kb, sloC, sloR, and downstream flanking DNA | 34 |

| pVA2587 | Apr; 8.14 kb, sloABCR operon and flanking DNA | 34 |

| pVA2592 | Apr Kanr; This study containing 1.37-kb aphA-3 cassette ligated at BamHI site | 19 |

| pVA891 | Emr Cmr; 6.45 kb, suicide vector | 41 |

| pVA838 | Emr Cmr; 9 kb, E. coli-Streptococcus shuttle plasmid | 42 |

| pVA2642 | Kanr Emr; 5.9-kb EcoRV-SalI fragment containing ΔsloR1::aphA-3 ligated into pVA891 | This study |

| pJFP9 | Cmr Emr; 1.03-kb XmnI fragment containing sloR from pVA2587; ligated into pVA838 | This study |

| pVA2587-kan | Apr Kanr; 1.37-kb aphA-3 cassette inserted at EcoNI site in the sloA gene in pVA2587 | This study |

DNA manipulations.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from S. mutans as described previously (34). Southern blot labeling and detection were performed with the Genius digoxigenin system (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.). PCR was routinely performed in a GeneAmp 960 thermal cycler (PE Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) with Platinum PCR Supermix (BRL). Oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by BRL. Restriction enzymes were purchased from BRL or New England Biolabs, Inc., Beverly, Mass.) and used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Construction of mutant strains. (i) sloR mutant.

The sloR mutant was constructed as follows. Two rounds of PCR were performed to generate a deletion marked by a BamHI site in sloR as described previously (26, 34). SalI and EcoRV sites were incorporated at either end of each amplicon for cloning. P1 (5′-CCATAGATATCGTTCCTGTTGGTC-3′) and P2 (5′-AGCCGGATCCATCTCGTTCACTGAG-3′) were used for one amplicon. P3 (5′-GTGATGGATCCGGCTGTCTCAGAGAT-3′) and P4 (5′-GCGTCGACCTTATTACCTTCGC-3′) were used for the other. The underlined sequences indicated the restriction sites EcoRV (P1), BamHI (P2 and P3), and SalI (P4). PCR products were purified from an agarose gel with a Freeze'n Squeeze DNA gel purification kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). The second round of PCR using P1 and P4 generated a sequence with an internal BamHI site as well as a 46-bp deletion in sloR. This 1.89-kb fragment was ligated into the EcoRV and SalI sites of pVA891. The resulting plasmid was digested with BamHI. The aphA-3 cassette from pVA2592 digested with BamHI was ligated into the BamHI-digested plasmid to disrupt sloR and to insert a selectable marker. The final suicide vector was designated pVA2642. This was linearized with ScaI and used to transform S. mutans V403. Selection with kanamycin resulted in isolation of a sloR mutant created by allelic exchange, V2643.

(ii) sloA mutant.

The plasmid pVA2587 (34) was digested with EcoNI, and the sticky ends resulting from the digestion were filled in by using deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) and the large fragment of DNA polymerase I (BRL) to create blunt ends. The aphA-3 cassette was obtained from pVA2592 by BamHI digestion, made blunt as described above, and ligated into pVA2587 to disrupt the sloA gene. The final suicide vector was designated pVA2587-kan. It was linearized with ScaI for transformation of S. mutans V403 to create strain JFP14.

(iii) sloR-complemented strains.

A plasmid expressing the sloR gene was constructed. Plasmid pVA2570 (34) was digested with XmnI, which produced four DNA bands. The 1,030-bp fragment that contained the sloR gene was gel purified and cloned into pVA891 at the NruI site. The resulting plasmid was designated pJFP9 and was used to transform V2613 (34) and V2643.

Protein analysis.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed with 12.5% Criterion precast gels (Bio-Rad), unless otherwise indicated, and visualized with Coomassie brilliant blue. Western blotting of duplicate unstained gels and immunodetection of SloC with anti-FimA antiserum were performed as described previously (66). Western blots were visualized with anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Fc)-alkaline phosphatase (AP) conjugated antibody (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and Western blue stabilized substrate for AP (Promega), unless otherwise indicated.

Growth studies.

BHI broth was treated to limit the availability of metal ions. Five grams of Chelex 100 (Bio-Rad) per 200 ml of BHI broth was prewashed in 100 ml of deionized water three times and then added to dissolved BHI, followed by stirring for 90 min at room temperature. Resin beads were removed, and the medium was filter sterilized. Magnesium sulfate was added to the Chelex-treated BHI broth at 81 or 810 μM. This basal medium was designated BCMg81 or BCMg810, respectively. Overnight cultures grown anaerobically in BHI were diluted 1,000-fold into fresh BHI broth, BCMg81, or BCMg81 supplemented with MnCl2, Fe(III)C6H5O7, or Fe(II)SO4. Duplicate cultures were aerobically incubated at 37°C for up to 48 h without shaking.

55Fe uptake study.

For 55Fe uptake experiments, FMC media (63) were treated with Chelex 100 as described above and reconstituted with 810 μM Mg (FMC-CMg810). Overnight cultures of S. mutans strains were anaerobically grown in anaerobically preincubated FMC-CMg810. Cultures were then diluted 25- to 75-fold into anaerobically preincubated FMC-CMg810 and incubated for an additional 5 to 6 h. One culture of each strain with an optical density at 660 nm (OD660) of approximately 0.7 to 0.8 was selected for the uptake study. 55FeCl3 (2 mCi; specific activity, 18.1 mCi/mg) was purchased from Perkin-Elmer/NEN (Boston, Mass.), and 0.4 μCi was used for each sample. The MultiScreen assay system (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) was used for the uptake experiments. The filtration 96-well plate was prewetted with 100 μl of 0.1 M NiSO4 to prevent nonspecific binding of Fe to the filter membranes. A metal mix solution, including 0.4 μCi of 55FeCl3, FeSO4, and, for some experiments, MnCl2, was prepared. Twenty microliters of the metal mix solution was mixed with 480 μl of cells in microcentrifuge tubes. The final concentrations of each metal in the sample were as follows: 55Fe at 0.27 μM; Fe at 0, 1, 5, 10, and 15 μM; and Mn at 1, 4, 8, and 12 μM. In addition, sodium ascorbate was added to a final concentration of 5 mM (17). Samples were incubated for periods ranging from 2 to 30 min at room temperature. Immediately thereafter, 200 μl of cells was transferred to the 96-well plate, and the liquid was filtered out by vacuum. Free 55Fe was removed by three successive washes with 200 μl of citrate buffer (100 mM Na3C6H5O7, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM CaCl2). Parallel experiments were performed with cells incubated on ice as a nonspecific binding control. The cpm values obtained for chilled cells (which remained constant over time) were subtracted from those obtained from room temperature-incubated cells. Filters were air dried in a fume hood. A MultiScreen punch (Millipore) was used to isolate each filter from the 96-well plate, which was collected in a high-density polyethylene scintillation vial (Fisherbrand; Fisher, Pittsburgh, Pa.). Four milliliters of scintillation fluid was added to the vial, and the radioactivity was measured by scintillation counting with “wide open” window setting, using a Beckman LS6500 scintillation counter (Fullerton, Calif.).

Animal models.

The previously described rat model of endocarditis was employed (47). The protocol received Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees approval (no. 0010-2865) and complied with all applicable federal guidelines and institutional policies. In brief, a catheter was inserted through the internal carotid artery past the aortic valve to impose valve damage. The catheter was sutured and remained in the artery throughout the rest of the experiment. Two days later, streptococci grown in BHI broth plus 0.5% sucrose were harvested, washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and inoculated into the tail vein of the catheterized rats. Two days later, the rats were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation. The heart was removed, and accurate catheter placement was assessed visually. The aortic valve and any apparent vegetations were removed, homogenized with PBS, and spread on tryptic soy agar plates. Rats were judged to be infected if bacteria were recovered. Rats in which correct catheter placement could not be verified at necropsy, which had no apparent vegetations, and from which no bacteria were recovered were dropped from the study. All other rats from which bacteria were not recovered were judged to be uninfected. Differences in infectivity were evaluated by using the exact Cochran-Mantel-Haenzel test and Fisher's exact test.

RESULTS

SloR is an Mn-dependent repressor of SloC expression.

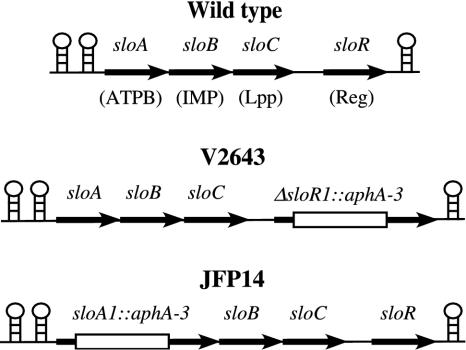

In our previous study (34), the DNA sequence of an LraI operon, sloABCR, from S. mutans was determined. The structure of this operon is shown in Fig. 1. We hypothesized that the sloR gene product functions as a metal-dependent repressor of sloABCR expression. To test this hypothesis, a sloR mutant was constructed for this study (V2643; Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

sloR and sloA mutant strains. The sloABCR operon is shown at the top with the genes depicted by arrows. DNA sequences containing inverted repeats are shown as stem-loops. (See GenBank accession no. AF232688.) Putative functions for the genes are indicated: ATPB, ATP-binding protein; IMP, integral membrane protein; Lpp, lipoprotein receptor; Reg, metal-dependent regulator. V2643 contains a 46-bp deletion and a 1.4-kb aphA-3 cassette encoding resistance to kanamycin inserted into the sloR gene in the same orientation as sloR, as shown by the open box. JFP14 contains the aphA-3 cassette inserted into the sloA gene in the same orientation.

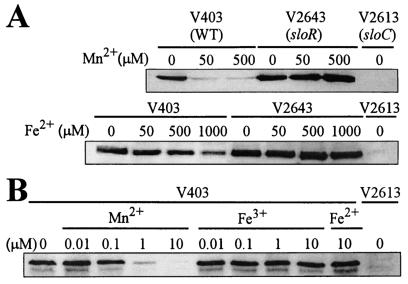

Western blot analysis was performed with the wild-type strain (V403), a sloR mutant (V2643), and a ΔsloC mutant (V2613). The effects of Mn and Fe on SloC expression were investigated. Figure 2 shows Western blots examining cultures grown with variable concentrations of Mn or Fe added to the culture medium (BHI). A band with a molecular mass of 34 kDa reacted with a rabbit polyclonal anti-FimA antiserum for both the wild type (V403) and the sloR mutant (V2643) in each Western blot. This band was not detected in the ΔsloC mutant (V2613), indicating that this protein is SloC. In the presence of 50 and 500 μM MnSO4, SloC expression in V403 (wild type) was repressed (Fig. 2A). In contrast, no significant repression was observed with V403 at 50 or 500 μM FeSO4, and only partial repression was observed at 1,000 μM FeSO4 (Fig. 2A). SloC expression in the sloR mutant (V2643) remained high regardless of the amount of added Mn2+ or Fe2+ (Fig. 2A). This suggests that Mn2+-dependent repression of SloC is mediated by the SloR protein.

FIG. 2.

Western blot analysis of the effect of Mn and Fe on SloC expression. Equal amounts of total protein isolated from cultures of S. mutans V403 (wild-type), V2643 (sloR mutant), and V2613 (ΔsloC mutant) were separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for Western blot detection with rabbit polyclonal anti-FimA antiserum. (A) Overnight cultures grown in BHI broth under anaerobic conditions were diluted 100-fold into fresh BHI broth or BHI broth supplemented with MnSO4 or FeSO4 added at the concentrations indicated. Protein preparations were made the following day after overnight growth as described previously (66). Gels were 12% Bio-Rad Ready cast, and the ECL enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.) was used for visualization of Western blots. (B) Cultures were grown anaerobically in BHI broth with MnCl2, Fe(III)C6H5O7, or Fe(II)SO4 at the concentrations indicated. Lysates were prepared as described above, except that a Fast Prep, FP120 (Bio101, Savant, Vista, Calif.) bead beater was used at level 6 for 30 s to lyse cells.

It seemed possible that the form of Fe used for the experiment could be important. Therefore, both the Fe2+ and Fe3+ forms of iron were separately tested by Western blot analysis, as shown in Fig. 2B. In addition, lower concentrations of Fe and Mn were used. Slight repression of SloC was observed at 0.1 μM Mn2+, and SloC was strongly repressed by 10 μM Mn2+. In contrast, neither form of iron changed the level of SloC detected by Western blotting (Fig. 2B). When six additional metals (ZnCl2, CuSO4, NiSO4, MgCl2, CoCl2, and CaCl2) were tested at 50 and 500 μM concentrations, none appeared to affect SloC expression in V403, although 500 μM CuSO4 appeared to slightly inhibit growth (data not shown).

Role of the sloABCR operon in growth under metal-limited conditions.

Based on the results shown in Fig. 2 and the homology of the sloABC gene products to other Mn transport systems, it seemed reasonable that the SloABC system would transport Mn. However, because Spatafora et al. (58) reported this system functions in the transport of Fe and not Mn, both metals were investigated for uptake. It was shown previously that Mg is the only metal required by S. mutans for growth under anaerobic conditions (44). Under aerobic conditions, either Fe or Mn was required in addition to Mg. Our growth studies with V403 and its derivatives indicated that they also required only Mg when grown under anaerobic conditions (data not shown). These results led us to reason that if Mn or Fe were essential for S. mutans, this requirement would be revealed under aerobic growth conditions. As one test of whether the sloABCR operon encoded an ABC-type Mn or Fe uptake system, wild-type and mutant strains were grown aerobically in metal-limited media.

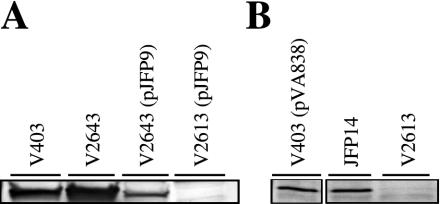

In preparation for growth studies, additional mutant strains were constructed. To confirm that the derepression of SloC in V2643 resulted from loss of sloR, a sloR-containing plasmid, pJFP9, was introduced into V2643. The pJFP9 plasmid was also introduced into V2613. In our previous study (34), it was not clear whether sloR was expressed in V2613. The expression of the sloR gene from a plasmid could separate possible effects of sloC mutation from a sloR mutation. The production of SloR by pJFP9 in the two complemented strains was assessed indirectly by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3A). The level of SloC expression in V2643(pJFP9) was reduced compared to that in V2643. This result would be expected if SloR is being produced from pJFP9 and repressing sloC transcription. Since SloC expression is even lower in V2643(pJFP9) than in V403 (Fig. 3A), it appears that SloR is produced at greater than wild-type levels from pJFP9. Although SloR expression from pJFP9 could not be assessed in V2613(pJFP9), because of the lack of SloC production in that strain (Fig. 3A), it is reasonable to assume that SloR was also expressed in that strain.

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of SloC expression in mutant strains. Streptococcal lysates from the indicated strains grown anaerobically in BHI were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-FimA antiserum. V403, wild type; V2613, ΔsloC mutant. (A) V2643, sloR mutant; V2643(pJFP9), sloR-complemented sloR mutant; V2613(pJFP9), sloR-complemented sloC mutant. (B) Separate blot examining JFP14, sloA mutant.

A sloA mutant was constructed by inserting the aphA-3 cassette into the sloA gene, and the new strain was designated JFP14 (Fig. 1). To determine whether this mutation was polar on expression of downstream genes in the operon, SloC expression in JFP14 was investigated by Western blot analysis. The results are shown in Fig. 3B. SloC expression in this strain is equivalent to that in the wild-type strain, V403. Transcription of sloC presumably originates either from the aphA-3 promoter or from read-through transcription, which has been observed previously with this cassette (18).

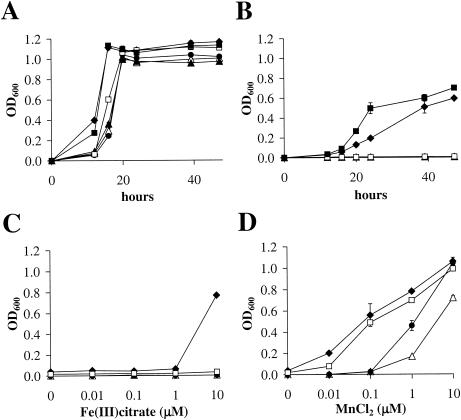

V403, V2613, V2613(pJFP9), V2643, V2643(pJFP9), and JFP14 were grown aerobically in BHI or BCMg81 medium supplemented with either Fe (Fe3+ or Fe2+) or Mn2+. Growth was not observed in any strain in BCMg81 (data not shown), whereas all strains grew equivalently in BHI (Fig. 4A). At 10 μM, Fe3+ partially restored growth of V403 and V2643(pJFP9), although it was delayed compared to growth in BHI broth (Fig. 4B). In some experiments, V2643 exhibited poor growth: up to 21% of its growth in BHI broth (data not shown). Growth of the sloA or ΔsloC strains was not detected throughout the experiment. The failure of the sloA and ΔsloC mutants to grow suggests that the SloABC proteins function in Fe uptake. The reason for the failure of the sloR mutant, V2643, to grow well was not immediately apparent. Interestingly, V2643(pJFP9) grew more quickly than V403 (Fig. 4B). One explanation for both of these findings was that Fe was required for growth in the absence of other metals, but too much Fe was toxic. The level of sloABC expression in V2643 and V403 may have led cells to take up too much iron, while overproduction of SloR in V2643(pJFP9) may have led to near-optimal Fe uptake. To test this possibility, V403, V2613, JFP14, and V2643 were grown at lower Fe3+ concentrations (Fig. 4C). V403 again grew in 10 μΜ Fe3+; however, growth was not improved by lowering the Fe concentration. With 10 μM Fe2+ (FeSO4), V403, V2643, and V2643(pJFP9) exhibited poor and inconsistent growth (0 to 20% compared to their growth in BHI), whereas the sloA and ΔsloC mutants showed no growth (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Aerobic growth of wild-type and mutant strains of S. mutans. (A and B) Growth in (A) BHI broth and BCMg81 plus 10 μM Fe(III) C6H5O7 (B). OD600 was measured at 0, 12, 16, 20, 24, 39, and 47 h of incubation. (C and D) Culture densities at a single time point in BCMg81 containing Fe(III) C6H5O7 or MnCl2 at the concentrations indicated. (C) OD600 at 38 h of incubation with Fe(III) C6H5O7. (D) OD600 at 16 h of incubation with MnCl2. ⧫, wild-type; ▵, sloC mutant; ▴, sloR-complemented sloC mutant; •, sloA mutant; □, sloR mutant; ▪, sloR-complemented sloR mutant. The two sloR-complemented strains were not included in panels C and D. Error bars indicate standard deviations from duplicate cultures.

When Mn2+ was added at 10 μM, growth of V403 and all the mutant strains was equivalent to that shown in Fig. 4A for BHI broth (data not shown). This was not unexpected, inasmuch as maximal growth of the scaA and scaC LraI operon mutants of S. gordonii was restored by the addition of ≥1 μM Mn2+ (36). The effect of addition of lower concentrations of Mn2+ was therefore investigated (Fig. 4D). At Mn2+ concentrations of 0.01 and 0.1 μM, V2613 and JFP14 showed no detectable growth (OD600 ≤ 0.01 at 16 h), whereas at Mn2+ concentrations of 0.01 and 0.1 μM, V403 and V2643 attained ODs of 0.07 to 0.20 and 0.49 to 0.56, respectively. At 1 μM Mn2+, V2613 and JFP14 grew to intermediate densities, and at 10 μM, the growth of JFP14 was restored to that of the wild type, while V2613 approached this level (Fig. 4D). When the OD600 was measured at later time points (18 and 20 h), 0.01 and 0.1 μM concentrations of Mn2+ still did not support the growth of V2613 and JFP14 (data not shown). These results suggest that the SloABC system functions as a high-affinity Mn2+ transport system that is essential for aerobic growth of S. mutans under low (0.01 and 0.1 μM) Mn2+ concentrations and that there is at least one additional, lower-affinity Mn2+ transport system in S. mutans. The combined results also suggest that Mn supports aerobic growth more efficiently than Fe in S. mutans.

The SloABC system functions in Fe and Mn acquisition.

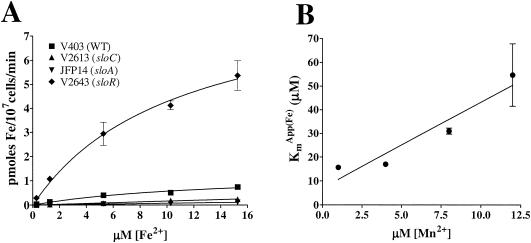

A more direct approach was employed to investigate Fe and Mn acquisition by the SloABC system. Wild-type and mutant strains were examined for acquisition of radioactive iron with or without nonradioactive Mn as a competitor. First, 55Fe acquisition by V403 (wild type) over 2 to 30 min was measured. The uptake velocity was greatest at 2 min and decreased at longer intervals, as expected (data not shown). Next, uptake velocities for V2613 (ΔsloC), JFP14 (sloA), and V2643 (sloR) were compared to that of V403 over a period of 2 min (Fig. 5A). The graphs for V403 (wild type) and V2643 (sloR) show saturation kinetics, as expected for active transport, whereas those for V2613 (ΔsloC) and JFP14 (sloA) are barely above background.

FIG. 5.

55Fe acquisition by S. mutans. (A) Acquisition of radioactive Fe over 2 min in wild-type and slo mutant strains of S. mutans at five different Fe concentrations (0.27, 1.27, 5.27, 10.27, and 15.27 μM). Points are connected by nonlinear regression lines. Experiments were performed three times. The results shown are from one representative experiment. (B) Apparent Km values for Fe acquisition in the presence of Mn as a competitor at 1, 4, 8, and 12 μM in wild-type S. mutans (V403). Samples were prepared in quadruplicate except those with 12 μM Mn (duplicate). The experiment was performed twice with similar results. One data set connected by a linear regression line is shown.

As shown in Table 2, the Vmax of V2643 (sloR) is about five times that of V403 (wild type), whereas the Km values of the two strains are similar. This is the expected result if Fe uptake occurs by the same transporter in both strains, with the transporter more abundant in the sloR mutant. The amount of Fe acquired by V2613 (ΔsloC) or JFP14 (sloA) was too low to produce reliable Km or Vmax values, as evidenced by the large standard errors for these strains. The average velocities for V2613 (ΔsloC) and JFP14 (sloA) from three experiments were 9.3 and 6.8%, respectively, of that of the wild type at 5.27 μM Fe. These findings support the conclusion that the SloABC system is involved in the acquisition of Fe in S. mutans and that, in the absence of SloR repression, increased expression of SloABC results in increased Fe acquisition.

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters for Fe uptake in wild-type and slo mutant strains

| Strain | KmFe (μM) | Vmax (pmol/107 cells/min) |

|---|---|---|

| V403 (wild type) | 9.7 ± 4.1 | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

| V2613 (sloC) | 83 ± 420 | 1.5 ± 6.9 |

| JFP14 (sloA) | 94 ± 409a | 0.8 ± 3.1a |

| V2643 (sloR) | 9.9 ± 1.7 | 8.7 ± 0.7 |

Average ± standard error of two independent experiments. All other values are from three experiments.

Next, Mn was added as a competitive inhibitor of 55Fe uptake. If Mn is transported by the same system that transports Fe, the apparent Km for Fe, KmApp (Fe), should increase with increasing Mn. By plotting KmApp (Fe) against [Mn], the concentration of Mn that causes half-maximal inhibition of Fe uptake, Ki Mn, can be determined. Kmapp values for Fe uptake were measured in the presence of Mn concentrations of 1, 4, 8, and 12 μM, as shown in Fig. 5B. The slope of the best-fit line is 3.6 ± 0.8, which represents Km/Ki. The x-intercept is −2.0, and the y-intercept is 7.0 ± 6.0, which represent −KiMn and KmFe, respectively. The y-intercept, although containing a large standard error, is close to the KmFe value of V403 shown in Table 2. The finding that KiMn (2.0 μM) is lower than KmFe and that the slope (KmFe/KiMn) is larger than 1 suggests that the SloABC system has a higher affinity for Mn than Fe.

A sloA mutant has reduced virulence in a rat endocarditis model.

V403 and the sloA mutant, JFP14, were tested for virulence in a rat model of endocarditis. The results are shown in Table 3. In experiment 1, V403 caused infection in 5 of 11 rats, whereas JFP14 infected 0 of 7 rats. The 45% infection rate obtained for V403 is similar to that seen for this strain in previous experiments (34); nevertheless, it was hoped that this infection rate could be increased by employing a more rigid catheter material. For experiment 2, which was performed at the same time as experiment 1, a monofilament catheter material was used. In this experiment, V403 caused 50% infection, and again, JFP14 infected no rats. The catheter type therefore showed no apparent effect on infection rate by either strain. The results of the two experiments were combined and tested by the Cochran-Mantel-Haenzel test. The infection rate of 7 of 15 (47%) for V403 was significantly greater than the infection rate of 0 of 11 (0%) for JFP14 (P = 0.0231; Table 3, combined).

TABLE 3.

Virulence of S. mutans V403 and sloA::aphA-3 mutants in a rat model of endocarditis

| Strain | Genotype | No. of rats infected/total (% infected)a | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1 | |||

| V403 | Wild type | 5/11 (45) | 0.0539b |

| JFP14 | sloA1::aphA-3 | 0/7 (0) | |

| Expt 2 | |||

| V403 | Wild type | 2/4 (50) | 0.4286b |

| JFP14 | sloA1::aphA-3 | 0/4 (0) | |

| Combined | |||

| V403 | Wild type | 7/15 (47) | 0.0231c |

| JFP14 | sloA1::aphA-3 | 0/11 (0) |

Surgical survivors with correct catheter placement at necropsy.

Fisher's exact probability test.

Cochran-Mantel-Haenzel test.

DISCUSSION

The contribution of SloR to SloC expression in S. mutans was examined. Figure 2 shows that SloC is repressed when cells possessing a functional sloR gene are grown in the presence of Mn. This suggests that SloR is an Mn-dependent repressor of SloC expression. No other metal tested repressed SloC expression efficiently. When Fe was added at 1 mM, SloC was slightly repressed (Fig. 2A). However, this could be due to contamination by Mn in the FeSO4 added to the media. According to the manufacturer's analysis, Mn was present at 0.03%, indicating a concentration of approximately 0.5 μM in a 1 mM solution of FeSO4. Examination of Fig. 2B suggests that this concentration of contaminating Mn could account for the degree of repression observed in Fig. 2A. It is not clear why Spatafora et al. (58) observed SloC repression with as little as 1 μM Fe, whereas greater than 500 μM Fe was required to observe even partial repression in our hands. We initially suspected that the form of Fe employed was important, since Spatafora et al. used Fe3+, whereas we used Fe2+. Figure 2B indicates that Fe3+ also failed to repress SloC. In an attempt to resolve this difference, we also grew cells in the same media used by Spatafora et al.: FMC medium treated with Chelex 100 to remove metals and then supplemented with 80 μM Mg2+ and 0.4 μM Mn2+. We observed very low levels of SloC expression whether Fe3+ was added to the medium or not (data not shown). We interpret these results as SloR-dependent repression of SloC effected by the 0.4 μM Mn in the medium. In a recent study, it was reported that residues D8 and E99 of B. subtilis MntR are responsible for the Mn selectivity of this SloR homolog (22). SloR also contains these residues (D7 and E99), in agreement with expectations if SloR is an Mn-responsive regulator.

We next attempted to determine whether the SloABC proteins function in Mn or Fe transport. Two lines of evidence suggest that these proteins transport both metals. First, the growth studies shown in Fig. 4 indicate that the sloABC genes are required for aerobic growth in the presence of Fe and low concentrations of Mn. This is most easily explained by SloABC-mediated transport of these metals. Although the reason for the poor and inconsistent growth of V2643 (sloR) in Fe3+ and of all strains in Fe2+ was not determined (Fig. 4B and C) (data not shown), this may be due to the difficulty of maintaining Fe in a soluble and available form for extended periods in an aerobic environment. Second, the 55Fe uptake studies presented in Fig. 5A and Table 2 indicate that sloA and ΔsloC mutants acquire far less Fe than wild-type cells, and a sloR mutant acquires more. These results are consistent with SloABC-mediated uptake of Fe. Addition of Mn as a competitor increased the Kmapp for Fe in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 5B). Because the cells were exposed to Mn for only 2 min, the decrease in Fe acquisition cannot be due to Mn-dependent repression of the SloABC proteins. Instead, it is most likely that Mn competes with Fe for binding and transport and apparently does so with greater efficiency than Fe. When a substrate and an inhibitor are both acted upon by the same enzyme, the Ki of the inhibitor is equivalent to its Km (12). The Ki for Mn was 2.0 μM, which is about one-fourth the Km of Fe in wild-type S. mutans. Although the standard error for Ki was large, this suggests that Mn would be preferentially transported by the SloABC system, compared to Fe. These results can again be compared with those of Spatafora et al. (58). Using 55Fe and 54Mn uptake assays, Spatafora et al. reported that a sloC mutant was unaffected in Fe uptake, that a sloR mutant exhibited increased uptake, and that Mn uptake was not significantly affected by mutations in sloC or sloR. These results were interpreted as evidence of SloC-mediated Fe uptake. We also observed increased Fe uptake in a sloR mutant, but our results concerning a ΔsloC mutant and Mn uptake differ. One possible explanation for these differences is that our study measured uptake for 2 min, whereas Spatafora et al. grew cells overnight in the presence of radioisotopes. Longer incubations might allow for other transport systems to take up sufficient metal to reach equilibrium in both mutant and wild-type cells (58). It has been proposed that S. gordonii contains at least two Mn transporters in addition to the SloABC-homologous system: one of which is an NRAMP-like protein (27), and the other is a second ABC transport system encoded by the adc operon (40). An NRAMP-like gene also exists in the S. mutans genome (27), as does an adc operon, although adcA seems to encode a secreted protein in S. mutans (40). This could account for the aerobic growth of the sloA and ΔsloC mutants in Mn concentrations ≥1 μM. It may also account for the deviation of fit to the regression line shown in Fig. 5B, since competition for Fe uptake could be reduced by these additional Mn transport systems at the higher concentrations of Mn tested.

There is precedent for uptake of two or more metals by one ABC transport system. ScaCBA is a high-affinity Mn transport system that also transports Zn (36, 37). The mtsABC in S. pyogenes encodes an Fe/Zn transport system that also transports Mn (29, 30). The Adc Zn transporter in S. pneumoniae was proposed to transport Mn as well (14), and observations on the FimCBA system in S. parasanguis suggest that it also transports both Fe and Mn (11, 49). The regulatory mechanisms and the importance of these metal ion homeostasis systems are not yet fully elucidated. In S. mutans, the functional and regulatory properties of the sloABCR operon may provide unique benefits. As shown previously by others (44) and in our own studies (data not shown), S. mutans requires neither Fe nor Mn when grown anaerobically. In the presence of oxygen, either Fe or Mn is required, with Mn supporting growth that is faster and that reaches higher final densities (44) (Fig. 4). The growth-promoting effect of both metals likely results from their ability to serve as alternate cofactors for superoxide dismutase in S. mutans (43). Thus, the SloABC system may have evolved to take up either metal, because both have similar functions. Under aerobic conditions, however, free Fe can also generate toxic hydroxyl radicals by a Fenton-type reaction (8). Thus, Fe must be considered a “double-edged sword” for the cell, potentially affording both harm and protection. In contrast, free Mn does not induce the Fenton-type reaction (9) and has been demonstrated to act as an antioxidant in Lactobacillus plantarum (3) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (64). It is therefore not surprising that Mn is more effective than Fe for supporting aerobic growth. Our findings suggest that the SloABC system preferentially transports Mn when it is present and that accumulation of Mn results in SloR-mediated down-regulation of the system, which would then prevent Fe uptake. This system would seem to ensure that Mn is taken up preferentially if both Mn and Fe are present but would still allow Fe uptake in the absence of Mn. This ability may be physiologically relevant in the oral environment. Chicharro et al. measured concentrations of both Mn and Fe in the saliva of 40 young men (10). Variability was high, but mean concentrations of 80 to 84 μM for Fe and 25 to 36 μM for Mn were reported. Because this analysis did not assess binding of these metals to lactoferrin and other salivary constituents, it is not clear what amount of either metal is available for uptake by S. mutans.

Finally, our study further clarifies the role of the SloABC proteins in the virulence of S. mutans. Our previous study indicated that the ΔsloC mutant, V2613, was indistinguishable from its wild-type parent in a rat model of caries (34). These results were confirmed by Spatafora et al. (58), who examined a sloC mutant. This group also examined a sloR mutant in the same model and found that it likewise retained virulence. In contrast to the caries model, we found that V2613 was avirulent in a rat endocarditis model. Possible explanations for this result included a nutritional deficiency resulting from loss of SloABC-mediated metal transport and reduced adherence due to loss of SloC. An adhesin function for SloC is suggested by its homology to the FimA protein of S. parasanguis. FimA has been shown to be a virulence factor for endocarditis and to be important for binding to fibrin monolayers, which serve as an in vitro model of a damaged heart valve (7). Because SloC may possess both functions, it is impossible to determine by sloC mutation which function is required for virulence. Construction of a sloA mutant, JFP14, for this study was designed to address this question. In contrast to sloC, the sloA gene encodes the ATP-binding component of the SloABC uptake system and should have no function other than providing energy for transport (24). Furthermore, Fig. 3B indicates that JFP14 produces near-wild-type levels of SloC protein. If SloC-mediated adherence occurs, it should be intact in this mutant. Therefore, while this experiment does not address the possibility that SloC functions as an adhesin, the failure of JFP14 to cause endocarditis (Table 3) indicates that loss of metal transport is sufficient to account for loss of virulence in this model. The concentration of free Fe in the bloodstream is on the order of 10−24 M (6). It is therefore highly unlikely that Fe transport by the SloABC system is important for survival of S. mutans in the blood. In contrast, Mn levels in the bloodstream are reported to be about 1 μg or 0.02 μmol/liter, with a portion of this bound to serum proteins (38, 55). This concentration appears to be in the range that could allow growth of our wild-type strain but not the sloA or ΔsloC mutant (Fig. 4D). In support of this hypothesis, addition of 10, 20, 30, or 40% rat serum to BCMg810 medium resulted in aerobic growth of the wild-type and sloR mutant strains, but not the sloA and ΔsloC mutants (data not shown). Therefore, we conclude that loss of Mn transport is responsible for loss of endocarditis virulence in the sloA mutant.

These findings are encouraging in terms of vaccine development efforts based on the SloC homolog, FimA. Vaccination with FimA protects rats against endocarditis caused by S. parasanguis (66) S. mitis, S. salivarius, and S. mutans (35). If the LraI proteins in each of these species possess both the fibrin-binding properties of FimA and the Mn-transporting function of SloC, any mutation in the gene that results in loss of reactivity of the protein to anti-FimA antibodies may also result in loss of a function critical to pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Shelton and Sherif Elhady for assistance in the creation and verification of the sloA mutant and Erin Grap for performing the rat serum growth studies. We thank Al Best, Darrell Peterson, Nick Jakubovics, Howard Jenkinson, and the Molecular Pathogenesis group at Virginia Commonwealth University for helpful discussions.

Support for this project was provided by PHS grant DE04224 to F. L. Macrina.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Karaawi, Z. M., V. S. Lucas, M. Gelbier, and G. J. Roberts. 2001. Dental procedures in children with severe congenital heart disease: a theoretical analysis of prophylaxis and non-prophylaxis procedures. Heart 85:66-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alloing, G., M. C. Trombe, and J. P. Claverys. 1990. The ami locus of the gram-positive bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae is similar to binding protein-dependent transport operons of gram-negative bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 4:633-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archibald, F. S., and I. Fridovich. 1981. Manganese and defenses against oxygen toxicity in Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Bacteriol. 145:442-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baddour, L. M. 1999. Immunization for prevention of infective endocarditis. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 1:126-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayliss, R., C. Clarke, C. Oakley, W. Somerville, and A. G. Whitfield. 1983. The teeth and infective endocarditis. Br. Heart J. 50:506-512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun, V., and H. Killmann. 1999. Bacterial solutions to the iron-supply problem. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:104-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnette-Curley, D., V. Wells, H. Viscount, C. L. Munro, J. C. Fenno, P. Fives-Taylor, and F. L. Macrina. 1995. FimA, a major virulence factor associated with Streptococcus parasanguis endocarditis. Infect. Immun. 63:4669-4674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byers, B. R., and J. E. L. Arceneaux. 1998. Microbial iron transport: iron assimilation by pathogenic microorganisms. Metal Ions Biol. Syst. 35:37-65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheton, P. L., and A. F. S. 1988. Manganese complexes and the generation and scavenging of hydroxyl free radicals. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 5:325-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chicharro, J. L., V. Serrano, R. Urena, A. M. Gutierrez, A. Carvajal, P. Fernandez-Hernando, and A. Lucia. 1999. Trace elements and electrolytes in human resting mixed saliva after exercise. Br. J. Sports Med. 33:204-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Claverys, J. 2001. A new family of high-affinity ABC manganese and zinc permeases. Res. Microbiol. 152:231-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornish-Bowden, A. 1979. Fundamentals of enzyme kinetics. Butterworths, London, United Kingdom.

- 13.Dajani, A. S., K. A. Taubert, W. Wilson, A. F. Bolger, A. Bayer, P. Ferrieri, M. H. Gewitz, S. T. Shulman, S. Nouri, J. W. Newburger, C. Hutto, T. J. Pallasch, T. W. Gage, M. E. Levison, G. Peter, and G. Zuccaro, Jr. 1997. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis—recommendations by the American Heart Association. JAMA 277:1794-1801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dintilhac, A., G. Alloing, C. Granadel, and J. P. Claverys. 1997. Competence and virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae: Adc and PsaA mutants exhibit a requirement for Zn and Mn resulting from inactivation of putative ABC metal permeases. Mol. Microbiol. 25:727-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dintilhac, A., and J. P. Claverys. 1997. The adc locus, which affects competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae, encodes an ABC transporter with a putative lipoprotein homologous to a family of streptococcal adhesins. Res. Microbiol. 148:119-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durack, D. T. 1995. Prevention of infective endocarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:38-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans, S. L., J. E. L. Arceneaux, B. R. Byers, M. E. Martin, and H. Aranha. 1986. Ferrous iron transport in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 168:1096-1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fenno, J. C., A. Shaikh, G. Spatafora, and P. Fives-Taylor. 1995. The fimA locus of Streptococcus parasanguis encodes an ATP-binding membrane transport system. Mol. Microbiol. 15:849-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franken, C., G. Haase, C. Brandt, J. Weber-Heynemann, S. Martin, C. Lammler, A. Podbielski, R. Lutticken, and B. Spellerberg. 2001. Horizontal gene transfer and host specificity of beta-haemolytic streptococci: the role of a putative composite transposon containing scpB and lmb. Mol. Microbiol. 41:925-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganeshkumar, N., M. Song, and B. C. McBride. 1988. Cloning of a Streptococcus sanguis adhesin which mediates binding to saliva-coated hydroxyapatite. Infect. Immun. 56:1150-1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilson, E., G. Alloing, T. Schmidt, J. P. Claverys, R. Dudler, and M. Hofnung. 1988. Evidence for high affinity binding-protein dependent transport systems in gram-positive bacteria and in Mycoplasma. EMBO J. 7:3971-3974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guedon, E., and J. D. Helmann. 2003. Origins of metal ion selectivity in the DtxR/MntR family of metalloregulators. Mol. Microbiol. 48:495-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamada, S., and H. D. Slade. 1980. Biology, immunology, and cariogenicity of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol. Rev. 44:331-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins, C. F., S. C. Hyde, M. M. Mimmack, U. Gileadi, D. R. Gill, and M. P. Gallagher. 1990. Binding protein-dependent transport systems. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 22:571-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horsburgh, M. J., S. J. Wharton, A. G. Cox, E. Ingham, S. Peacock, and S. J. Foster. 2002. MntR modulates expression of the PerR regulon and superoxide resistance in Staphylococcus aureus through control of manganese uptake. Mol Microbiol. 44:1269-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horton, R. M. 1995. PCR-mediated recombination and mutagenesis. SOEing together tailor-made genes. Mol. Biotechnol. 3:93-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jakubovics, N. S., and H. F. Jenkinson. 2001. Out of the iron age: new insights into the critical role of manganese homeostasis in bacteria. Microbiology 147:1709-1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jakubovics, N. S., A. W. Smith, and H. F. Jenkinson. 2000. Expression of the virulence-related Sca (Mn2+) permease in Streptococcus gordonii is regulated by a diphtheria toxin metallorepressor-like protein ScaR. Mol. Microbiol. 38:140-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janulczyk, R., J. Pallon, and L. Bjorck. 1999. Identification and characterization of a Streptococcus pyogenes ABC transporter with multiple specificity for metal cations. Mol. Microbiol. 34:596-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janulczyk, R., S. Ricci, and L. Björck. 2003. MtsABC is important for manganese and iron transport, oxidative stress resistance, and virulence of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 71:2656-2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenkinson, H. F. 1994. Cell surface protein receptors in oral streptococci. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 121:133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kehres, D. G., A. Janakiraman, J. M. Slauch, and M. E. Maguire. 2002. Regulation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium mntH transcription by H2O2, Fe2+, and Mn2+. J. Bacteriol. 184:3151-3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiska, D. L., and F. L. Macrina. 1994. Genetic analysis of fructan-hyperproducing strains of Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 62:2679-2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitten, T., C. L. Munro, S. M. Michalek, and F. L. Macrina. 2000. Genetic characterization of a Streptococcus mutans LraI family operon and role in virulence. Infect. Immun. 68:4441-4451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitten, T., C. L. Munro, A. Wang, and F. L. Macrina. 2002. Vaccination with FimA from Streptococcus parasanguis protects rats from endocarditis caused by other viridans streptococci. Infect. Immun. 70:422-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kolenbrander, P. E., R. N. Andersen, R. A. Baker, and H. F. Jenkinson. 1998. The adhesion-associated sca operon in Streptococcus gordonii encodes an inducible high-affinity ABC transporter for Mn2+ uptake. J. Bacteriol. 180:290-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kolenbrander, P. E., R. N. Andersen, and N. Ganeshkumar. 1994. Nucleotide sequence of the Streptococcus gordonii PK488 coaggregation adhesin gene, scaA, and ATP-binding cassette. Infect. Immun. 62:4469-4480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krachler, M., E. Rossipal, and D. Micetic-Turk. 1999. Concentrations of trace elements in sera of newborns, young infants, and adults. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 68:121-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindler, L. E., and F. L. Macrina. 1986. Characterization of genetic transformation in Streptococcus mutans by using a novel high-efficiency plasmid marker rescue system. J. Bacteriol. 166:658-665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loo, C. Y., K. Mitrakul, I. B. Voss, C. V. Hughes, and N. Ganeshkumar. 2003. Involvement of the adc operon and manganese homeostasis in Streptococcus gordonii biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 185:2887-2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Macrina, F. L., R. P. Evans, J. A. Tobian, D. L. Hartley, D. B. Clewell, and K. R. Jones. 1983. Novel shuttle plasmid vehicles for Escherichia-Streptococcus transgeneric cloning. Gene 25:145-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macrina, F. L., J. A. Tobian, K. R. Jones, R. P. Evans, and D. B. Clewell. 1982. A cloning vector able to replicate in Escherichia coli and Streptococcus sanguis. Gene 19:345-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin, M. E., B. R. Byers, M. O. Olson, M. L. Salin, J. E. Arceneaux, and C. Tolbert. 1986. A Streptococcus mutans superoxide dismutase that is active with either manganese or iron as a cofactor. J. Biol. Chem. 261:9361-9367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin, M. E., R. C. Strachan, H. Aranha, S. L. Evans, M. L. Salin, B. Welch, J. E. L. Arceneaux, and B. R. Byers. 1984. Oxygen toxicity in Streptococcus mutans: manganese, iron, and superoxide dismutase. J. Bacteriol. 159:745-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michalek, S. M., J. R. McGhee, and J. M. Navia. 1975. Virulence of Streptococcus mutans: a sensitive method for evaluating cariogenicity in young gnotobiotic rats. Infect. Immun. 12:69-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Munro, C., S. M. Michalek, and F. L. Macrina. 1991. Cariogenicity of Streptococcus mutans V403 glucosyltransferase and fructosyltransferase mutants constructed by allelic exchange. Infect. Immun. 59:2316-2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Munro, C. L. 1998. The rat model of endocarditis. Methods Cell Sci. 20:203-207. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Munro, C. L., and F. L. Macrina. 1993. Sucrose-derived exopolysaccharides of Streptococcus mutans V403 contribute to infectivity in endocarditis. Mol. Microbiol. 8:133-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oetjen, J., P. Fives-Taylor, and E. H. Froeliger. 2002. The divergently transcribed Streptococcus parasanguis virulence-associated fimA operon encoding an Mn2+-responsive metal transporter and pepO encoding a zinc metallopeptidase are not coordinately regulated. Infect. Immun. 70:5706-5714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oligino, L., and P. Fives-Taylor. 1993. Overexpression and purification of a fimbria-associated adhesin of Streptococcus parasanguis. Infect. Immun. 61:1016-1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patzer, S. I., and K. Hantke. 2001. Dual repression by Fe2+-Fur and Mn2+-MntR of the mntH gene, encoding an NRAMP-like Mn2+ transporter in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:4806-4813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Posey, J. E., J. M. Hardham, S. J. Norris, and F. C. Gherardini. 1999. Characterization of a manganese-dependent regulatory protein, TroR, from Treponema pallidum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:10887-10892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Que, Q., and J. D. Helmann. 2000. Manganese homeostasis in Bacillus subtilis is regulated by MntR, a bifunctional regulator related to the diphtheria toxin repressor family of proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1454-1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roberts, G. J. 1999. Dentists are innocent! “Everyday” bacteremia is the real culprit: a review and assessment of the evidence that dental surgical procedures are a principal cause of bacterial endocarditis in children. Pediatr. Cardiol. 20:317-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scheuhammer, A. M., and M. G. Cherian. 1985. Binding of manganese in human and rat plasma. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 840:163-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schroeder, V. A., S. M. Michalek, and F. L. Macrina. 1989. Biochemical characterization and evaluation of virulence of a fructosyltransferase-deficient mutant of Streptococcus mutans V403. Infect. Immun. 57:3560-3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seymour, R. A., R. Lowry, J. M. Whitworth, and M. V. Martin. 2000. Infective endocarditis, dentistry and antibiotic prophylaxis: time for a rethink? Br. Dent. J. 189:610-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spatafora, G., M. Moore, S. Landgren, E. Stonehouse, and S. Michalek. 2001. Expression of Streptococcus mutans fimA is iron-responsive and regulated by a DtxR homologue. Microbiology 147:1599-1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spellerberg, B., E. Rozdzinski, S. Martin, J. Weber-Heynemann, N. Schnitzler, R. Lütticken, and A. Podbielski. 1999. Lmb, a protein with similarities to the LraI adhesin family, mediates attachment of Streptococcus agalactiae to human laminin. Infect. Immun. 67:871-878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Strom, B. L., E. Abrutyn, J. A. Berlin, J. L. Kinman, R. S. Feldman, P. D. Stolley, M. E. Levison, O. M. Korzeniowski, and D. Kaye. 1998. Dental and cardiac risk factors for infective endocarditis—a population-based, case-control study. Ann. Intern. Med. 129:761-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sutcliffe, I. C., and R. R. Russell. 1995. Lipoproteins of gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 177:1123-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tartof, K. D., and C. A. Hobbs. 1987. Improved media for growing plasmid and cosmid clones. Focus 9:12. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Terleckyj, B., N. P. Willett, and G. D. Shockman. 1975. Growth of several cariogenic strains of oral streptococci in a chemically defined medium. Infect. Immun. 11:649-655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tseng, H. J., Y. Srikhanta, A. G. McEwan, and M. P. Jennings. 2001. Accumulation of manganese in Neisseria gonorrhoeae correlates with resistance to oxidative killing by superoxide anion and is independent of superoxide dismutase activity. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1175-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van der Meer, J. T., W. van Vianen, E. Hu, W. B. van Leeuwen, H. A. Valkenburg, J. Thompson, and M. F. Michel. 1991. Distribution, antibiotic susceptibility and tolerance of bacterial isolates in culture-positive cases of endocarditis in The Netherlands. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 10:728-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Viscount, H. B., C. L. Munro, D. Burnette-Curley, D. L. Peterson, and F. L. Macrina. 1997. Immunization with FimA protects against Streptococcus parasanguis endocarditis in rats. Infect. Immun. 65:994-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]