Abstract

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is a membrane-bound cell surface peptidase which is over-expressed in prostate cancer cells. The enzymatic activities of PSMA are understood but the role of the enzyme in prostate cancer remains conjectural. We previously confirmed the existence of a hydrophobic binding site remote from the enzyme's catalytic center. To explore the specificity and accommodation of this binding site, we prepared a series of six glutamate-containing phosphoramidate derivatives of various hydroxysteroids (1a–1f). The inhibitory potencies of the individual compounds of the series were comparable to a simple phenylalkyl analog (8), and in all cases IC50 values were sub-micromolar. Molecular docking was used to develop a binding model for these inhibitors and to understand their relative inhibitory potencies against PSMA.

A notable discovery in prostate cancer research has been the identification of an over-expressed membrane-bound cell surface protein on prostate cancer cells, namely, prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). PSMA, also known as folate hydrolase I (FOLH1) and glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII),1–3 is a 750-amino acid type II membrane glycoprotein4 and was discovered during the development of the LNCaP cell line; one which retains most of the known features of prostate cancer.5

Although PSMA is primarily expressed in normal human prostate epithelium, the importance of this enzyme lies with the fact that it is upregulated and strongly expressed in prostate cancer cells, including those of the metastatic disease state.6 It has also been demonstrated PSMA expression is present in the endothelium of tumor-associated neovasculature of multiple nonprostatic solid malignancies,7 including metastatic renal carcinoma.8 As such, it is not surprising that PSMA has attracted a great deal of attention as a target for immunotherapy.9–12 In addition to its immunological importance, PSMA is also reported to possess two predominant, yet poorly understood enzymatic activities: the hydrolytic cleavage and liberation of glutamate from γ-glutamyl derivatives of folic acid13, 14 and the proteolysis of the neuropeptide N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG)2. With respect to its function, recent studies suggest that PSMA plays a regulatory role in angiogenesis.15

Recently, we identified the presence of a hydrophobic binding site remote from the catalytic center of PSMA using a series of phenylalkylphosphonamidate derivatives of glutamic acid.16 Based upon ongoing substrate and inhibitor-based studies in our lab, we have determined that PSMA can accommodate a variety of structural motifs remote from the catalytic center. The focus of this work was to determine if PSMA could specifically accommodate steroidal motifs in auxiliary binding sites remote from the catalytic center. To this end, we prepared a series of putative hydroxysteroid-containing phosphoramidate inhibitors of PSMA (Figure 1) and determined their inhibitory potency against purified PSMA.

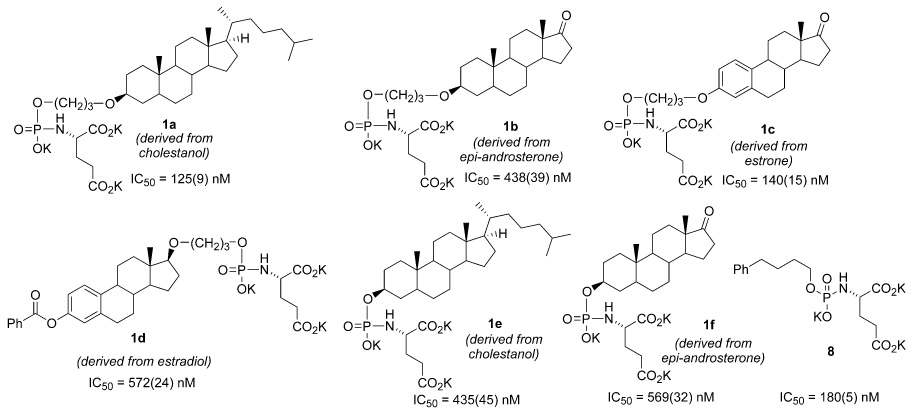

Figure 1.

Structures and inhibitory potencies of steroid-derived phosphoramidate inhibitors (1a–1f) of PSMA and non-steroidal reference compound (8). Standard deviation for IC50 values in parenthesis.

A general method (Scheme 1) was employed for the preparation of hydroxysteroid phosphoramidate inhibitors (Figure 1). Briefly, bis(diisopropylamino)-chlorophosphine (2) was conjugated with benzyl alcohol to generate benzyloxyphosphine 3, and then coupled with steroid-derived alcohols 4a–4f to generate phosphoramidites 5a–5f (see Supporting Information for the structures, synthesis, and characterization of 4a–4f), using conventional methodology.17,18 These molecules were hydrolyzed to the corresponding steroid-conjugated phosphites 6a–6f. Oxidative coupling with benzyl protected glutamate was accomplished with CH3CN-CCl4 to generate 7a–7f. Lastly, removal of benzyl protecting groups was performed under hydrogenolysis conditions to yield the phosphoramidate inhibitors 1a–1f as the tri-potassium salts.

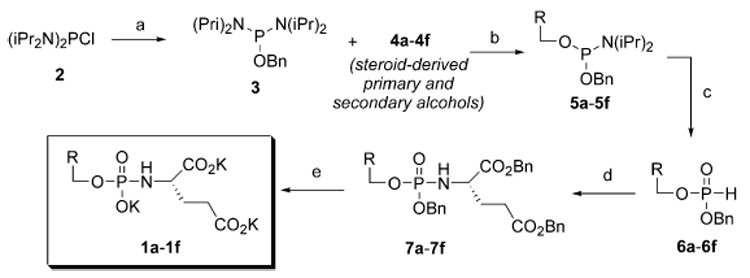

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of hydroxysteroid-derived phosphoramidate inhibitors of PSMA. Reagents and conditions: (a) benzyl alcohol (3.0 eq), Et3N (3.0 eq), CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 1h; (b) diisopropylammonium tetrazolide (1.05 eq), steroid-derived alcohols 4a–4f, CH2Cl2 (c) 5-(ethylthio)-1H-tetrazole (1.1 eq), CH3CN, H2O; (d) CH3CN, Et3N (2.0 eq), p-TsOH • H-Glu(OBn)-OBn (1.3 eq); then CCl4 (10 eq). (e) H2, cat. Pd (10% on C), K2CO3 (1.5eq), THF-H2O, 3h, RT.

Once prepared, the steroid-containing inhibitors 1a–1f were assayed for inhibitory potency against purified PSMA using methods described previously (Figure 1).16,19,20 For comparison, the IC50 value for a simple phenylalkyl phosphoramidate 8 identified in a previous study is also presented.21 All of the inhibitors maintained sub-micromolar inhibitory potency against PSMA, while two inhibitors (1a and 1c) achieved a slight improvement over 8. These results suggest that the enzyme can accommodate organic structures of considerable size and lipophilicity in proximity to the catalytic center. In at least one case, the propyl ether linker had an interesting effect on the potency of the inhibitors toward PSMA. For example, propyl ether linked inhibitor 1a was significantly more potent than the unlinked analog of the same steroid 1e. The effect was much less pronounced in linked inhibitor 1b versus its unlinked counterpart 1f. Unfortunately, the unlinked form of the relatively potent inhibitor 1c could not be readily prepared with our synthetic scheme.

Overall, the inhibitors appear to be broadly differentiated into two classifications based on their inhibitory potency against PSMA. Inhibitors 1a and 1c exhibit greater potency than 1b, 1d, 1e, and 1f and within these groups, the compounds attain fairly narrow ranges of IC50 values. The activity of the more active compounds (1a and 1c) is comparable to the simple phenylalkyl phosphoramidate inhibitor 8. That all compounds achieved sub-micromolar potency, including the less active inhibitors in the series, suggests that the general glutamyl phosphoramidate scaffold dominates the interactions with PSMA for this class of compounds. The significance of these results is that the this scaffold appears to be capable of accommodating a wide range of linked hydrophobic molecular fragments while still retaining notable potency.

To establish a tentative mode of binding and to rationalize the observed differentiation of the inhibitors by their potencies against PSMA, phosphoramidates 1a–1f were computationally docked into the active site of PSMA (Figure 2 and Supporting Information). The results were obtained employing a recently determined high-resolution X-ray crystal structure22 in which the enzyme was co-crystallized with a phosphonate inhibitor (PDB=2C6C). Docking of each inhibitor was performed with FRED2 (OpenEyes) employing a library of ligand conformations generated by OMEGA (OpenEyes). To filter docking poses non-productive for enzymatic inhibition, a SMARTS pharmacophore constraint was utilized requiring the phosphoramidate oxygen atoms to be within 3 Å of the two catalytic zinc atoms of PSMA. Subsequently, the top consensus scoring pose for each inhibitor was then minimized, without constraint, in the MMFF94 force field as implemented in SZYBKI (OpenEyes).

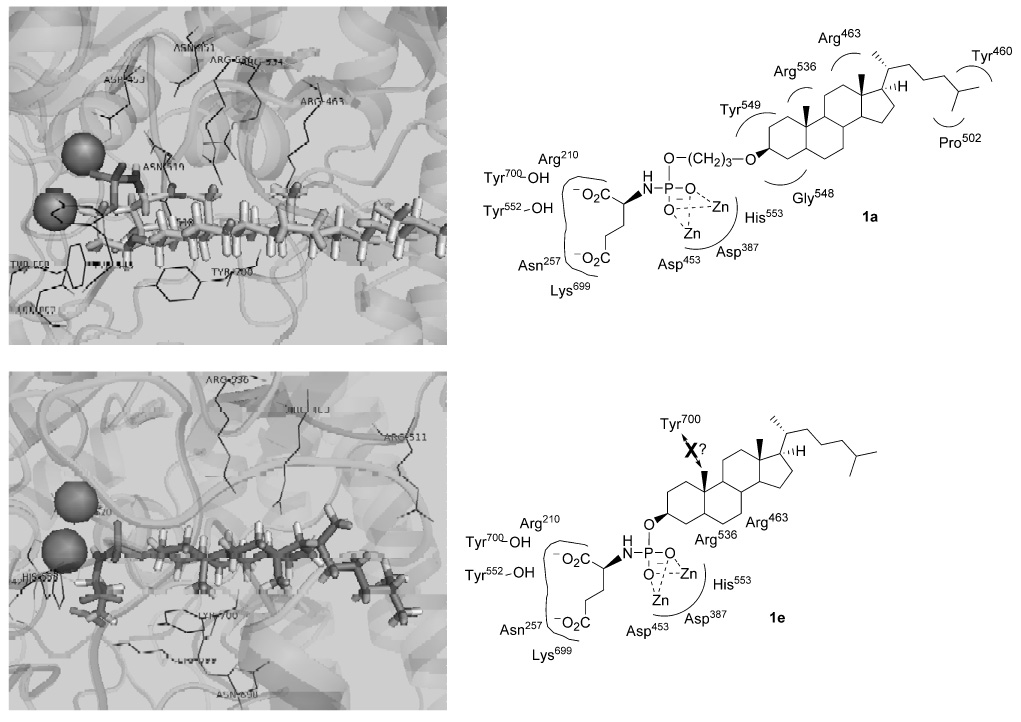

Figure 2.

Results from docking inhibitors 1a and 1e into the active site of PSMA (PDB=2C6C). Dark grey spheres represent the zinc atoms in the PSMA active site. Docking results of other inhibitors in Supporting Information. Structures were visualized with PYMOL.

Upon docking this series of inhibitors, the most notable observation was the effect of the propyl ether linker on the steroid conformation in compounds 1a (versus 1e) and 1b (versus 1f). Interestingly, the presence of the linker caused the steroid nucleus to flip its docked orientation relative to the inhibitor without a linker. A result of this phenomenon is that it dictated the positions of the steroidal angular methyl groups, which have a propensity to sterically clash with residues in the PSMA active site. Thus, the docked conformations of 1a (linked) and 1e (unlinked) show opposite orientations of the steroid systems, and in the case of 1e, the A–B ring angular methyl is oriented in a manner which potentially clashes with the Tyr700 aromatic ring. We speculate that such a steric effect could explain the significant potency difference between 1a and 1e. The propyl linker also extends 1a through the PSMA binding cavity in a manner that could allow the steroid alkyl chain to be involved in favorable hydrophobic interactions with distant residues Pro502 and Tyr460, further explaining the improved potency of this compound. A similar conformational flip was observed with 1b (linked) and 1f (unlinked), but in this case 1b exhibited potential steric clashing with Tyr700, while 1f was observed in a relatively unhindred conformation. This model could explain the relatively poor potency of 1b, but the lack of inhibitory potency in 1f is not readily explained with this model. However, the docked pose of the relatively potent inhibitor 1c (linked) displayed an orientation of the steroid framework in which little steric hindrance was observed overall. Lastly, compound 1d (linked) is unique relative to the other inhibitors due to the linker attachment at the steroid D ring. The docked conformation of this inhibitor presented the angular methyl in a manner which could potentially clash with Tyr700, which may explain its relative low potency.

In summary, a small library of hydroxysteroid-containing phosphoramidate PSMA inhibitors was prepared and evaluated for inhibitory potency against PSMA. The relative potencies were explained by a model generated through computational docking studies. Namely, the least potent compounds in the series docked with their steroidal angular methyl groups projected in an opposite orientation from Tyr700 avoiding a potential steric clash. In contrast, the remaining compounds presenting docked poses in which the angular methyls projected away from Tyr700 all exhibited improved potency (with the exception of 1f). The activity of the most potent inhibitor (1a) may be explained by additional hydrophobic contacts with Pro502 and Tyr460. Notably, the entire series of inhibitors exhibited sub-micromolar potency against PSMA suggesting that the binding of these analogs may be driven by the N-phosphoglutmate core. Results from the designs of subsequent generations of PSMA inhibitors will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, MBRS SCORE Program-NIGMS (Grant No. S06-GM052588) and the Department of Defense (Grant No. PC051060). The authors would also like to extend their gratitude to W. Tam and the NMR facility at SFSU for their expert assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Drugs in R&D. 2004;5(6) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter RE, Feldman AR, Coyle JT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tiffany CW, Lapidus RG, Merion A, Calvin DC, Slusher BS. Prostate. 1999;39:28. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19990401)39:1<28::aid-pros5>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes EH, Greene TG, Tino WT, Boynton AL, Aldape HC, Misrock SL, Murphy GP. Prostate Suppl. 1996;7:25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horoszewicz JS, Leong SS, Kawinski E, Karr JP, Rosenthal H, Chu TM, Mirand EA, Murphy GP. Cancer Res. 1983;43:1809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacich DJ, Pinto JT, Tong WP, Heston WD. Mamm genome. 2001;12(2):117. doi: 10.1007/s003350010240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang SS, O'Keefe DS, Bacich DJ, Reuter VE, Heston WD, Gaudin PB. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(10):2674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang SS, Reuter VE, Heston WD, Gaudin PB. Urology. 2001;57:801. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)01094-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tasch J, Gong M, Sadelain M, Heston WD. Crit Rev Immunol. 2001;21:249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salit RB, Kast WM, Velders MP. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 2002;7:e204. doi: 10.2741/salit. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu J, Celis E. Cancer Res. 2002;62(20):5807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fracasso G, Bellisola G, Cingarlini S, Castelletti D, Prayer-Galetti T, Pagano F, Tridente G, Colombatti M. The Prostate. 2002;53(1):9. doi: 10.1002/pros.10117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heston WD. Urology. 1997;49(104) doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinto JT, Suffoletto BP, Berzin TM, Qiao CH, Lin S, Tong WP, May F, Mukherjee B, Heston WD. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:1445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conway RE, Petrovic N, Li Z, Heston W, Wu D, Shapiro LH. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:5310. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00084-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maung J, Mallari JP, Girtsman TA, Wu LY, Rowley JA, Santiago NM, Brunelle AN, Berkman CE. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:4969. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whalen LJ, McEvoy KA, Halcomb RL. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:301. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen SB, Halcomb RL. J Org Chem. 2000;65:6145. doi: 10.1021/jo000646+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wone DW, Rowley JA, Garofalo AW, Berkman CE. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:67. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu T, Toriyabe Y, Berkman CE. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;49:251. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu LY, Anderson MO, Toriyabe Y, Maung J, Campbell TY, Tajon C, Kazak M, Moser J, Berkman CE. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:7434. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mesters JR, Barinka C, Li W, Tsukamoto T, Majer P, Slusher BS, Konvalinka J, Hilgenfeld R. Embo J. 2006;25:1375. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.