Abstract

Allelic replacement in staphylococci is frequently aided by antibiotic resistance markers that replace the gene(s) of interest. In multiply modified strains, the number of mutated genes usually correlates with the number of selection markers in the strain's chromosome. Site-specific recombination systems are capable of eliminating such markers, if they are flanked by recombinase recognition sites. In this study, a Cre-lox setting was established that allowed the efficient removal of resistance genes from the genomes of Staphylococcus carnosus and S. aureus. Two cassettes conferring resistance to erythromycin or kanamycin were flanked with wild-type or mutant lox sites, respectively, and used to delete single genes and an entire operon. After transformation of the cells with a newly constructed cre expression plasmid (pRAB1), genomic eviction of the resistance genes was observed in approximately one out of ten candidates analyzed and subsequently verified by PCR. Due to its thermosensitive origin of replication, the plasmid was then easily eliminated at nonpermissive temperatures. We anticipate that the system presented here will prove useful for generating markerless deletion mutants in staphylococci.

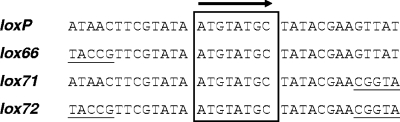

Staphylococci belong to the low-G+C gram-positive bacteria, with a spherical morphology and characteristically form grape-like clusters. To date, at least 38 species of this genus have been identified (16, 46), which, although closely linked phylogenetically, differ markedly in their physiology. Staphylococcus carnosus is an apathogenic and, from a human viewpoint, rather beneficial bacterium, which has been used in the food industry since the 1950s. Among other processes, S. carnosus reduces nitrate to nitrite and eventually to ammonia in fermented meat, whereby both the nitrate concentration and the pH are lowered for preservation purposes (summarized in reference 16). The characteristic flavor of salami sausages is also conferred by S. carnosus. In addition, this species has proven suitable for expressing heterologous proteins (15), which can be secreted or displayed on the bacterial surface (37, 43) without risking endotoxin contamination. In contrast, the most prominent representative of staphylococci is S. aureus, reputedly the causative agent of various infections, such as mastitis, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, enterocolitis, and further illnesses that can be life-threatening in immunocompromised patients. A vast amount of nosocomial infections are attributed to S. aureus, some of which are increasingly hard to combat due to the strains' acquisition of multiple-antibiotic resistance (28). In particular, S. aureus strains resistant to methicillin or vancomycin can hardly be combated by the few remaining active antibiotics left (34). Although numerous pathogenicity factors have been identified and infection-related traits of S. aureus are increasingly better understood (summarized in reference 14), deeper insight into this organism's physiology is still necessary to identify potential sites of attack for novel anti-infective compounds. To this end, useful molecular biology tools such as replicative or integrative vectors (10, 27), transposons, other mobile genetic elements, or derivatives thereof (6, 23, 35, 48) have been developed and applied to genetically manipulate staphylococci. For convenient selection of the thus-modified strains, antibiotic resistance markers are usually used that henceforth reside within the strains' chromosomes and are vertically transmitted. Consecutive deletions of further genes in the same strain may thus be limited by the number of suitable resistance genes. In fact, only a few antibiotics such as erythromycin, tetracycline, kanamycin, or spectinomycin are usually applied for the selection of genetically modified Staphylococcus mutants. However, the presence of antibiotic resistance genes in deletion mutants influences phenotypic alterations sometimes by transcriptional read-through to genes located downstream or by energy consumption of resistance gene expression, leading to a decrease in bacterial fitness. Furthermore, multiple deletion mutants accumulate an intolerably high number of resistance genes. Such hurdles are overcome if the resistance markers are eliminated after mutant selection, which can be achieved conveniently via site-specific recombination. The most frequently applied systems in bacteria are Flp-FRT, derived from the Saccharomyces cerevisiae 2μm plasmid (reviewed in reference 39), and Cre-loxP, naturally found in bacteriophage P1 (5, 41, 42). Like Flp, the 38-kDa Cre protein belongs to the tyrosine integrase family of site-specific recombinases and does not require accessory factors for recombination (reviewed in reference 18). The cognate DNA sequence of Cre is designated loxP (for locus of x-over of P1) and consists of palindromic ends (13 bp each) flanking an 8-bp asymmetric spacer region (Fig. 1). Cre-mediated recombination leads to excision of any DNA (e.g., an antibiotic resistance cassette) in between two distant intramolecular loxP sites with a collinear orientation, leaving only one loxP site behind and (in this example) reinstating the antibiotic sensitivity of the respective strain. In the past, numerous mutant lox sequences were tested for recognition by Cre (1, 3, 47). Of particular popularity are lox66 and lox71, which, compared to loxP, exhibit 5-bp exchanges at their 5′ or 3′ ends, respectively. One product of recombination between them is lox72, which is a poor substrate for Cre. By exploiting such mutant sites, further rounds of gene deletion and marker recycling can be performed in the same strain with a drastically reduced risk of undesired cross-recombinations (1).

FIG. 1.

Comparison between different lox sites. The upper strands of loxP, lox66, lox71, and lox72 are shown in a 5′-to-3′ direction. loxP constitutes the wild-type sequence with a 13-bp palindrome flanking the 8-bp asymmetric core region (boxed), which confers directionality of the sites. The 5-bp exchanges compared to loxP at the 5′ end of lox66, at the 3′ end of lox71, or on both sides (lox72) are underlined.

The aim of the present study was to exploit Cre-lox recombination to remove antibiotic resistance markers from staphylococcal chromosomes. Initial inactivation of S. carnosus and S. aureus genes was achieved by conventional allelic replacement procedures, applying the resistance markers ermB and aphAIII, which were flanked by either two wild-type loxP or by lox66 and lox71 sites, respectively. Upon transformation of the mutated strains with the easily curable vector pRAB1 carrying the cre gene, the recombinase was transiently expressed and led to chromosomal eviction of the markers. This new kind of genome manipulation further expands the molecular genetics toolbox for staphylococci and is first of all a basis for constructing markerless deletion mutants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Standard cloning procedures were applied using E. coli strains DH5α, XL1-Blue, or the restriction-deficient S. aureus RN4220 as a host. Gene deletions or disruptions were conducted in S. carnosus TM300 or S. aureus SA113. Cells were generally grown on solid medium or shaking in liquid BM (9) or TSB medium (BD, Heidelberg, Germany) at the indicated temperatures. Media were supplemented when appropriate with ampicillin (100 mg/liter for E. coli), kanamycin (Km; 30 mg/liter for E. coli or 15 mg/liter for S. aureus), chloramphenicol (Cm; 10 mg/liter for S. aureus), or erythromycin (Em; 2.5 mg/liter for S. carnosus). All strains used in the present study are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F− (φ80dlacZΔM15) Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 hsdR17(rK− mK+) recA1 endA1 relA1 (deoR)λ−phoA supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 | 20 |

| XL1-Blue | hsdR17(rK− mK+) recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 supE44 relA1 lac [F′ proAB laclqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| S. carnosus | ||

| TM300 | Wild type | 38 |

| TM300 (ΔsrtA) | srtA::loxP-ermB-loxP | This study |

| TM300 (ΔsrtA ΔermB) | srtA::loxP | This study |

| S. aureus | ||

| RN4220 | NCTC8325-4 derivative, acceptor of foreign DNA | 22 |

| SA113 (ATCC 35556) | NCTC8325 derivative, Δagr, 11-bp deletion in rbsU | 22 |

| SA113 (ΔarcA) | arcA::lox66-aphAIII-lox71 | This study |

| SA113 (ΔarcA ΔaphAIII) | arcA::lox72 | This study |

| SA113 (ΔarcABDCR) | arcABDCR::lox66-aphAIII-lox71 | This study |

| SA113 (ΔarcABDCR ΔaphAIII) | arcABDCR::lox72 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBT2 | cat bla; E. coli/staphylococcus shuttle vector, thermosensitive ori for staphylococci | 10 |

| pBT2-arcA | Allelic replacement vector for S. aureus arcA | This study |

| pBT2-arcOp | Allelic replacement vector for S. aureus arcABDCR | This study |

| pBT2-srtA | Allelic replacement vector for S. carnosus srtA | This study |

| pCrePA | PpagA-cre; expression of cre in B. anthracis | 36 |

| pDG792 | Source of aphAIII | 19 |

| pEC2 | Source of ermB | 10 |

| pRAB1 | cat bla, PpagA-cre; pBT2 derivative; expression of cre in staphylococci | This study |

Chemicals, enzymes, and oligonucleotides.

Chemicals were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), AppliChem (Darmstadt, Germany), or Sigma (Munich, Germany) at the highest purity available. Enzymes for DNA restriction, modification, and amplification, as well as molecular weight markers, were obtained from Fermentas (St. Leon-Rot, Germany), New England Biolabs (Frankfurt/Main, Germany), Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany), Peqlab (Erlangen, Germany), or GE Healthcare (Munich, Germany) and were used according to the manufacturers' recommendations. Lysostaphin was from Dr. Petry Genmedics (Reutlingen, Germany). Oligonucleotides were purchased from Biomers (Ulm, Germany) or MWG Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany), and primers containing lox sequences were from TIB-MOLBIOL (Berlin, Germany).

DNA isolation and manipulation.

Plasmid DNA was prepared from E. coli or S. aureus by using an E.Z.N.A. plasmid miniprep kit (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany) or a plasmid midikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturers' protocols, however, adding lysostaphin to a final concentration of 12.5 μg/ml, followed by 30 min of incubation at 37°C for cell lysis. Lysostaphin was applied because some staphylococcal species are resistant to lysozyme treatment (9). Chromosomal DNA of S. aureus or S. carnosus was obtained by using the InstaGene system (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. For subsequent PCR analyses, 10 to 20 μl of a total of 200 μl was used as a template in a 25-μl setup. E. coli strains for cloning were made competent and transformed by using standard techniques (20). S. aureus cells capable of taking up DNA via electroporation were treated as described previously (4). Transformation of S. carnosus was achieved using protoplast cells (17). DNA sequencing was done by using an ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany) or a LI-COR DNA Sequencer Long Reader (Lincoln Corp., Lincoln, NE), according to the protocols provided by the manufacturers or was carried out at GATC (Constance, Germany).

Cre recombinase expression vector construction.

A sequence comprising the Bacillus anthracis pagA promoter region and the cre gene was amplified by PCR from plasmid pCrePA (36) using the primers cre and erc (the primers used in the present study are listed in Table 2). The restriction sites introduced for PstI and SacI were used to insert the 1.43-kbp fragment generated into the likewise-cut E. coli/staphylococcus shuttle vector pBT2 (10). This plasmid and its derivatives have a thermosensitive origin of replication that allows for propagation in staphylococci at temperatures up to 30°C. The vector obtained was sequenced on both strands and termed pRAB1 (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| A_fw | AAATTGATATCTAAAATCATTACAAGTAGTAG |

| A_rw | TAATACTGCAGCTTTGAATTCATTTAGAGTATAG |

| arc_B_fw | ATTTACTGCAGTTATTCAATGATGTATGTG |

| arc_B_rw | TTTAAGAGCTCGTATTATTTGAATTAGAATAAT |

| B_fw | ATAATCTGCAGAGAGGACATTTAACG |

| B_rw | ATTATGTCGACACATGACACTTATATCATCAG |

| cre | TGCGTGAGAATGCTGCAGTCTATCC |

| delso-1neu | TTGGAATTCGCCCCATCCAGAGAATACATCG |

| delso-A | TGAACGGTACCACAAAGCGCTATAACATTGAC |

| delso-B | GGAATTTGTCGACAGGATTGTGGGTACTGTGG |

| erc | CGGCCAGTGAGCTCGCGTAATAC |

| Erm1 | GGCATTTAACGACGAAACGTGCTA |

| Erm2 | AGACAATACTTGCTCATAAGTAAC |

| Km_66 | GCTACTGCAGCGCTTCCCGCAATAGCGGGATACCGTTCGTATAATGTATGCTATACGAAGTTATGCGAACCATTTGAGGTGATAGGT |

| Km_71 | GCTACTGCAGCCTACCGTTCGTATAGCATACATTATACGAAGTTATGAGTATGGACAGTTGCGGATG |

| Km1 | ATGACGGACAGCCGGTATAAAGG |

| Km1.2 | AGATACGGAAGGAATGTCTCCTGC |

| Km2 | AGATGTTGCTGTCTCCCAGGTCG |

| Km2.2 | CCGCTTCTCCCAAGATCAATAAAGC |

| Komp_02969_fw | TATTAGGATCCGAAAGAATTCATAGTCATTC |

| Komp_arc_rw | ATATTGAGCTCATCACCTTAAATTTTACTG |

| Kontr_2969_fw | ACTTAGAATATAAGGACCAGTCAG |

| Kontr_2969_rw | CTTTGCAACAGTAACAATACTATTG |

| lox_erm_down | GGCAGCTGATAACTTCGTATAGCATACATTATACGAAGTTATGGTACCATGGGATCCTCTAG |

| lox_erm_up | TTCAATTGATAACTTCGTATAATGTATGCTATACGAAGTTATTGCCCATGGTTAACCCTAAAGT |

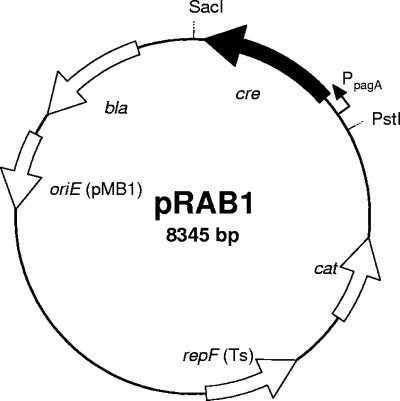

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the 8.35-kbp cre expression vector pRAB1. The singular restriction sites for SacI and PstI were used for cloning of a PpagA-cre fragment (PpagA is symbolized by a bent arrow). The features for plasmid propagation in E. coli are the β-lactamase encoding the bla gene for ampicillin selection and the pMB1 derived oriE region. The Staphylococcus specific regions are repF(Ts), which denotes a thermosensitive ori for plasmid maintenance, and the cat gene encoding Cm acetyltransferase for Cm resistance.

Cloning of an S. carnosus srtA replacement vector.

The srtA gene was amplified together with 0.85-kbp upstream and 0.88-kbp downstream regions by using the primers delso-A and delso-B from chromosomal S. carnosus TM300 DNA. The Acc65I- and SalI-restricted fragment was cloned into the equally digested vector pBT2 (10). A large part of the srtA open reading frame was deleted by partial restriction of the resulting vector with MamI (which has two restriction sites within srtA and one more in the cat gene of the plasmid backbone) and subsequent SpeI digestion of plasmids that were not cut by MamI within cat. After Klenow enzyme and alkaline phosphatase treatment, the vector was ligated with a 5′ phosphorylated loxP-ermB-loxP PCR product amplified from pEC2 (10) by using the primers lox_erm_up and lox_erm_down. In the resulting plasmid pBT2-srtA the orientation of loxP-ermB-loxP is identical to that of the disrupted srtA gene.

Construction of gene or operon deletion vectors for S. aureus.

A 0.97-kbp fragment A resembling the arcA upstream region and a 1.13-kbp fragment B identical to the region downstream of arcA were amplified by PCR from S. aureus SA113 chromosomal DNA by using the primers A_fw and A_rw and the primers B_fw and B_rw, respectively. Fragment A was cut with EcoRV and PstI, and fragment B was digested with PstI and SalI. Both were ligated with the 6.8-kbp SalI/EcoRV fragment of the vector pBT2 (10). An aphAIII cassette was amplified from plasmid pDG792 (19) with the primers Km_66 and Km_71, whereby aphAIII becomes flanked by lox66 (upstream) and lox71 (downstream). After PstI restriction, the 1.5-kbp product was ligated into the PstI-cut pBT2 derivative described above, yielding the final allelic replacement vector pBT2-arcA. The correctness of the plasmid, in which the lox66-aphAIII-lox71 cassette has the same orientation as the arcA gene, was verified by PCR and sequencing.

For the construction of an S. aureus arc operon deletion vector, the EcoRV- and PstI-restricted fragment A (see above) was used together with a 1.2-kbp sequence designated fragment R that was amplified from S. aureus SA113 chromosomal DNA by PCR using primers arc_B_fw and arc_B_rw and was restricted with SacI and PstI. Fragments A and R were both ligated with the 6.8-kbp SacI/EcoRV fragment of the vector pBT2. The resulting vector was digested with PstI, and the likewise-cut lox66-aphAIII-lox71 sequence (see above) was inserted to obtain the replacement vector pBT2-arcOp. The correctness of the plasmid, in which the lox66-aphAIII-lox71 cassette has the same orientation as the arcA gene, was verified by PCR and sequencing.

Construction of mutant S. carnosus and S. aureus strains.

The three constructed allelic replacement vectors described above were used to transform either S. carnosus TM300 protoplasts or electrocompetent S. aureus SA113 cells, respectively. Transformants were initially selected for Cm resistance, encoded by the vector backbone of pBT2 derivatives, at 30°C. The subsequent procedure for gene inactivation in staphylococci has been described previously (10).

Elimination of resistance markers from staphylococcal genomes.

Staphylococcus strains carrying resistance markers flanked by lox sites at the respective chromosomal loci were transformed with pRAB1 either as protoplasts (S. carnosus) or by electroporation (S. aureus) and were selected for Cm resistance at 30°C. Obtained candidates were then streaked in parallel on plates containing Cm or the antibiotic used for mutant selection, i.e., Em (S. carnosus) or Km (S. aureus) and were further incubated at 30°C. Candidates with sensitivity toward Em or Km, respectively, were freshly streaked in parallel on BMCm and BM and incubated at 42°C. Growth of candidates only on BM without antibiotic strongly indicated the loss of pRAB1.

RESULTS

Construction of a Cre recombinase expression vector for staphylococci.

The goal of the present study was to establish a site-specific recombination system allowing for in vivo excision of antibiotic resistance genes from the chromosomes of genetically modified staphylococci. To this end, we chose Cre-loxP, which is established in related gram-positive bacteria such as B. anthracis (36). There, the plasmid-encoded cre gene was expressed by the well-characterized native B. anthracis promoter PpagA (25). Visual inspection of the promoter sequence and the adjacent putative ribosomal binding site gave reason to assume that it could also be suitable for driving Cre expression in staphylococci. Hence, a PpagA-cre transcriptional fusion was cloned into the E. coli/Staphylococcus shuttle vector pBT2 (10). The resulting plasmid, pRAB1 (Fig. 2) has a pMB1 ori for amplification in E. coli and a temperature-sensitive repF ori that permits propagation in staphylococci at 30°C. At temperatures above 37°C, pBT2 derivatives are rapidly lost in S. aureus, S. carnosus, or S. xylosus (10). We reasoned that using pRAB1 should permit sufficient expression of Cre recombinase at 30°C and that raising the temperature after the floxed (flanked by lox) DNA was eliminated would eradicate the plasmid.

Insertional inactivation of S. carnosus srtA and removal of floxed ermB cassette.

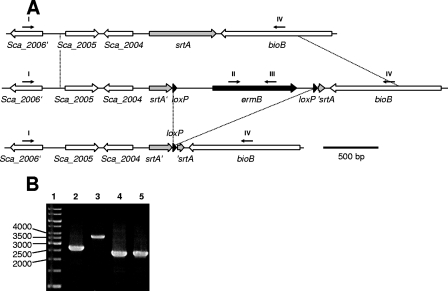

Sortase A is an enzyme that covalently anchors exoproteins to the cell wall (reviewed in reference 33). We aimed to inactivate the corresponding srtA gene of S. carnosus TM300 by insertion of a floxed ermB cassette. An srtA allelic replacement vector designated pBT2-srtA (see Materials and Methods for details) was used to transform S. carnosus protoplasts. One of the transformants was treated as outlined in Materials and Methods to obtain S. carnosus srtA mutants by double homologous recombination. Candidates showing Em resistance and Cm sensitivity were obtained at a frequency of ca. 0.5%. The srtA′-loxP-ermB-loxP-′srtA genotype was confirmed by PCR (Fig. 3). Using one of the positive candidates, the suitability of the cre expression vector for mediating eviction of the floxed ermB gene out of the genome was examined. Protoplasts of the ΔsrtA mutant were transformed with pRAB1 and initially cultured at 30°C on plates containing Cm. A total of 150 primary transformants were streaked in parallel on plates containing Cm or Em and were further incubated at 30°C. After approximately 48 h and further restreaking, 14 candidates displayed Em sensitivity, strongly indicating the loss of the chromosomal ermB cassette. This initially correlated with a Cm resistance phenotype due to the presence of pRAB1. Upon incubation of eight of these Ems/Cmr candidates freshly streaked in parallel on BMCm or BM at 42°C overnight, all clones tested showed decreased growth on Cm and, after further incubation for 24 h, none of the candidates grew on BMCm at 42°C, indicating pRAB1 loss, whereas growth on BM was normal. The genotypes of the different strains with respect to the srtA region were analyzed by PCR. Various primer combinations were applied to verify (i) changes in the size of the srtA region as judged by amplificates of different lengths using primers binding up- or downstream of srtA, (ii) the presence of the ermB gene only in the initial mutant and neither in the wild-type nor in the mutant after pRAB1 treatment (not shown), and (iii) the correct location of ermB within the disrupted srtA gene (not shown). As depicted in Fig. 3, all candidates displayed the expected bands after agarose gel electrophoresis of the obtained fragments. Thus, a strain with a srtA gene that was initially disrupted by a floxed ermB gene was rendered marker-free by the use of pRAB1.

FIG. 3.

(A) Genetic situation of the wild-type S. carnosus TM300 srtA region (upper panel), after srtA disruption by loxP-ermB-loxP (middle panel), and after Cre-mediated eviction of ermB (lower panel). Depicted are three genes (white arrows) upstream and one gene downstream of srtA (grey arrow). loxP sites are indicated as black triangles, and the ermB cassette is symbolized by a black arrow. Dotted lines between the upper and the middle panel indicate the boundaries of homologous regions as used for the allelic replacement vector. Dotted lines between the middle and the lower panel indicate the region that was removed by Cre. Except for the primers (depicted as small black arrows), the representations are drawn to scale, with a 500-bp ruler given at the bottom. Primers: I, delso-1neu; II, Erm1; III, Erm2; IV, delso-B. (B) Gel electrophoresis result of PCR products obtained with primers I and IV using chromosomal DNA of different S. carnosus strains, as indicated. Lanes: 1, molecular weight marker (relevant sizes are given in bps); 2, wild type; 3, srtA::loxP-ermB-loxP; 4, srtA::loxP, clone 1; 5, srtA::loxP, clone 2. Analogous PCR analyses with the primers II and III or the primers I and III yielded specific products only when srtA::loxP-ermB-loxP DNA was used as a template (not shown).

Deletion of a single S. aureus gene and excision of aphAIII flanked by mutant lox sites.

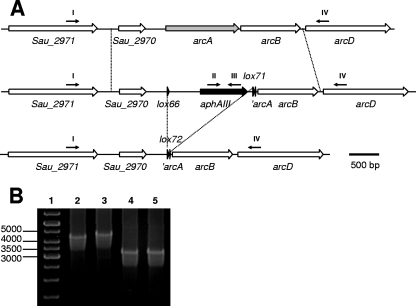

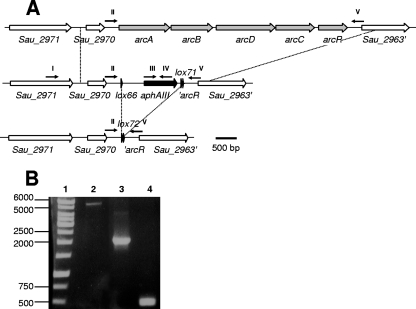

For utilization of arginine as an alternative energy source under anoxic conditions, S. aureus exhibits an arginine deiminase (ADI) pathway which is encoded by at least one operon (13). It comprises genes encoding ADI (arcA), ornithine transcarbamylase (arcB), an arginine/ornithine antiporter (arcD), carbamate kinase, and arginine regulator (arcR) (32). Under anaerobic and glucose depleted conditions, arginine serves as the sole energy source, and the ADI pathway produces ornithine, ammonia, and carbon dioxide. We assessed arcA as a suitable target for inactivation and subsequent elimination of the resistance marker to examine whether the Cre-lox system was also working in S. aureus. For selection of an arcA inactivation mutant, an aphAIII cassette in between the lox66 and lox71 sites was used. As shown in Fig. 1 compared to loxP, these variants sites exhibit 5-bp exchanges at one of their termini (1). The allelic replacement vector pBT2-arcA (see Materials and Methods for details) was introduced into S. aureus SA113 by electroporation, and ΔarcA strains were obtained by double homologous recombination (10). Transformants that exhibited Cm sensitivity and Km resistance were checked by PCR, confirming the expected genotype arcA::lox66-aphAIII-lox71 (Fig. 4). To excise aphAIII, pRAB1 was introduced by electroporation, and transformants were treated as outlined in Materials and Methods. Candidates with Km sensitivity and Cm resistance at 30°C were further screened for Cm sensitivity after incubation at 42°C. Strains that showed this phenotype were obtained at frequencies comparable to those observed for S. carnosus srtA mutants (see above). The genetic situations of the wild-type, the arcA::lox66-aphAIII-lox71, and the arcA::lox72 strains were analyzed by three different PCR setups. Figure 4 shows the results obtained with the respective strains for the region surrounding arcA.

FIG. 4.

(A) Genetic situation of the wild-type S. aureus SA113 arcA region (upper panel), after arcA deletion by lox66-aphAIII-lox71 (middle panel), and after Cre-mediated eviction of aphAIII (lower panel). Depicted are two genes (white arrows) upstream and two genes downstream of arcA (grey arrow). lox sites are indicated as black triangles, and the aphAIII cassette is symbolized by a black arrow. Dotted lines between the upper and the middle panel indicate the boundaries of homologous regions as used for the allelic replacement vector. Dotted lines between the middle and the lower panel indicate the region that was removed upon Cre treatment. Except for the primers (depicted as small black arrows), the representations are drawn to scale, with a 500-bp ruler given at the bottom. Primers: I, Kontr_2969_fw; II, Km1; III, Km2; IV, Kontr_2969_rw. (B) Gel electrophoresis result of PCR products obtained with primers I and IV using chromosomal DNA of different S. aureus strains, as indicated. Lanes: 1, molecular weight marker (relevant sizes are given in base pairs); 2, wild type; 3, arcA::lox66-aphAIII-lox71; 4, arcA::lox72, clone 1; 5, arcA::lox72, clone 2. Analogous PCR analyses with the primers II and III or the primers I and III yielded specific products only when arcA::lox66-aphAIII-lox71 DNA was used as a template (not shown).

Construction of marker-free S. aureus operon deletion mutant.

To further validate the method, we subsequently aimed to delete the entire S. aureus arcABDCR operon, followed by eviction of the resistance marker. To this end, the vector pBT2-arcOp was used, and the deletion procedure yielded a fully viable mutant strain by double homologous recombination. Its genome size at the original site of the operon was reduced by 4.05 kbp, as demonstrated by PCR (Fig. 5). One arcABDCR::lox66-aphAIII-lox71 mutant obtained was treated with pRAB1. Of 89 assayed candidates, 8 unambiguously displayed Km sensitivity afterward. In accordance with previous observations, pRAB1 was rapidly lost at 42°C. In order to verify the relevant chromosomal situations of the respective strains, three PCR setups were conducted (Fig. 5 shows the result of one of the primer combinations) that proved the expected situation around the arc operon in the respective strains.

FIG. 5.

(A) Genetic situation of the wild-type S. aureus SA113 arc operon (upper panel), after operon deletion by lox66-aphAIII-lox71 (middle panel), and after Cre-mediated eviction of aphAIII (lower panel). Depicted are two genes (white arrows) upstream and one gene downstream of the arcABDCR genes (grey arrows). lox sites are indicated as black triangles, and the aphAIII cassette is symbolized by a black arrow. Dotted lines between the upper and the middle panel indicate the boundaries of homologous regions as used for the allelic replacement vector. Dotted lines between the middle and the lower panel indicate the region that was removed upon Cre treatment. Except for the primers (depicted as small black arrows), the representations are drawn to scale, with a 500-bp ruler given at the bottom. Primers: I, Kontr_2969_fw; II, Komp_02969_fw; III, Km1.2; IV, Km2.2 (for one not depicted control PCR Km2 instead of Km2.2 was used, whose binding sites within aphAIII differ by 24 bp); V, Komp_arc_rw. (B) Gel electrophoresis result of PCR products obtained with primers II and V using chromosomal DNA of different S. aureus strains, as indicated. Lanes: 1, molecular weight marker (relevant sizes are given in base pairs); 2, wild type; 3, arcABDCR::lox66-aphAIII-lox71; 4, arcABDCR::lox72. Analogous PCR analyses with the primers III and IV or the primers I and IV yielded specific products only when arcA::lox66-aphAIII-lox71 DNA was used as a template (not shown).

DISCUSSION

Site-specific recombination is a versatile and convenient tool for all kinds of genome manipulations. The bacteriophage P1 derived Cre-loxP system has been adapted to gram-positive bacteria such as Corynebacterium glutamicum (44), mycobacteria (40), Streptomyces coelicolor (24), B. anthracis (36), Lactobacillus plantarum (26), or Lactococcus lactis (11) but has, to our knowledge, thus far remained untapped for the biotechnologically and medically important genus of staphylococci. We aimed to establish this technology in these bacteria primarily for marker excision purposes.

Procedures for allelic replacement are well established in S. carnosus and S. aureus (10) and usually (but not always, see below) employ antibiotic resistance markers. In the present study, two commonly used resistance genes were flanked with 34-bp lox sites to permit Cre-mediated excision after primary mutant selection. Using the newly constructed vector pRAB1 markerless deletion strains were obtained. It should be noted that Lowe et al. (30) previously established a site-specific recombination system for S. aureus, exploiting 122-bp res sites as cognate sequences of the transposon γδ TnpR resolvase (reviewed in reference 18) to mediate DNA eviction. This system was used to assay promoter activity within the scope of an in vivo expression technology study but has, to our knowledge, not found further application for marker removal in staphylococci. A recently described strategy to obtain marker-free S. aureus mutants completely sets antibiotic resistance markers for selection aside and thus supersedes subsequent marker eviction (7). This method is based upon an allelic replacement vector whose episomal state in S. aureus can be counterselected by inducible expression of a toxic secY antisense transcript. Despite this method's appeal, it may still be advantageous to reversibly tag an inactivated gene by a selection marker. If the mutated chromosomal region is to be transduced into another strain, the recipient cells can conveniently be selected, which is not possible when a marker gene is lacking (unless a selectable phenotypic alteration occurs). It may hence be sensible to combine the advantages of this allelic replacement strategy and the Cre-lox system. After excision of floxed markers out of the strains' chromosomes, lox “scars” are expected to remain at the respective loci. In a further S. aureus strain that has also been mutated using a floxed aphAIII cassette and has subsequently been treated with pRAB1, the presence of a perfect lox site was verified by sequencing (data not shown). Obtaining nucleotide precise lox sites after Cre treatment may be critical if translational readthrough of a disrupted gene is desired, which may be crucial for the efficient expression of downstream genes in an operon (29). Next to these considerations about translation, antibiotic resistance cassettes in place of an inactivated target gene or region inevitably cause polar transcriptional effects. Particularly within operons, this influence is massively reduced when merely a short 34-bp lox site is left at the mutated locus. Numerous Cre recombinase recognition sites have been described (1, 3, 47), of which loxP, lox66, and lox71 were applied in the present study. If more than one gene is to be deleted or disrupted in the same strain, particularly the use of the lox66/lox71 pair is recommendable, since the resulting lox72 sequence in the genome is not likely to interfere with subsequent rounds of Cre mediated excision of floxed DNA, as was demonstrated in L. plantarum (26). Besides these genetic aspects, eliminating resistance markers is mandatory when antibiotic sensitivity assays with genetically modified staphylococci are to be conducted with drugs of the same substance class as used for mutant selection. Furthermore, marker elimination in staphylococcal species used for nutritional purposes offers the opportunity to generate genetically modified strains that may thus maintain food-grade classification.

As in many other settings, Cre recombinase was transiently expressed from a thermally curable vector. To this end, the E. coli/Staphylococcus shuttle vector pBT2 (10) was equipped with a PpagA-cre fusion that has been developed previously for use in B. anthracis (36). The promoter sequence displays pronounced −35 and −10 consensus sequences of σA-dependent promoters (21), as well as a probable ribosomal binding site. In B. anthracis, this promoter region is regulated by the carbon dioxide sensitive transcriptional activator AtxA (12, 25). BLAST screenings (2) conducted in 16 staphylococcal genomes revealed that only S. aureus bears a putative transcriptional regulator protein which exhibits moderate similarity to AtxA (identity of ∼20% and similarity of ∼40% [data not shown]). Although its function has not yet been elucidated, there is no evidence that it could influence PpagA transcription in staphylococci, particularly since there are no PpagA-like sequences in the staphylococcal genomes surveyed (data not shown). We thus infer that the promoter sequence used should be constitutively active in staphylococci. After treatment with pRAB1, antibiotic sensitivity was reinstated in about 1 of 10 S. carnosus or S. aureus candidates assayed, indicating an acceptable degree of efficiency in both species. In accordance with Cre-lox settings in related gram-positive bacteria, the Cre expression vector was almost completely eradicable from both Staphylococcus species tested within 2 days after incubation of the cells at 42°C.

In addition to eliminating floxed marker genes, it is also possible to apply the Cre-lox technology for other purposes. First, it may offer the option to integrate exogenous DNA into defined loci of the staphylococcal genome, comparable to using plasmids with phage attachment sites for ectopic integration (27, 31). Although the Cre-lox system is inherently biased toward excision, integration of a plasmid vested with a single lox71 site into a lox66 locus that had previously been placed into the E. coli chromosome has been achieved (47). Second, staphylococcal genomes could be “streamlined” by carrying out large chromosome deletions, as has been conducted for C. glutamicum (45). Thereby, chromosomal regions dispensable for, or even disturbing specific applications of, industrially relevant staphylococci such as S. carnosus could be eradicated. A third possible application is to invert chromosomal regions and to study the effects of, for example, disturbed synteny on staphylococcal cell physiology. Similar studies were conducted in L. lactis (11) and P. aeruginosa (8).

In conclusion, the versatile and site-specific Cre-lox recombination system was established for use in S. carnosus and S. aureus, two prominent staphylococcal species. The functionality of the system was proven by eviction of markers flanked by either wild-type or mutant lox sites. It can be assumed that the use of the described Cre-lox setting is not confined to S. carnosus and S. aureus, since these two species are rather distantly related within the genus (46). We rather anticipate that the system could find use for numerous applications in staphylococcal genetics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen H. Leppla for kindly providing pCrePA and Michael Niederweis for providing data prior to publication and helpful discussions. Chris Berens is acknowledged for critically reading the manuscript. Günther Thumm and Sandra Frick are acknowledged for technical assistance and helpful technical advice.

This study was supported by grant BE 4038 and the TR-SFB34 (Pathophysiology of Staphylococci in the Postgenomic Era) of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albert, H., E. C. Dale, E. Lee, and D. W. Ow. 1995. Site-specific integration of DNA into wild-type and mutant lox sites placed in the plant genome. Plant J. 7:649-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araki, K., M. Araki, and K. Yamamura. 2002. Site-directed integration of the cre gene mediated by Cre recombinase using a combination of mutant lox sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:e103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Augustin, J., and F. Götz. 1990. Transformation of Staphylococcus epidermidis and other staphylococcal species with plasmid DNA by electroporation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 54:203-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayres, E. K., V. J. Thomson, G. Merino, D. Balderes, and D. H. Figurski. 1993. Precise deletions in large bacterial genomes by vector-mediated excision (VEX): the trfA gene of promiscuous plasmid RK2 is essential for replication in several gram-negative hosts. J. Mol. Biol. 230:174-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bae, T., A. K. Banger, A. Wallace, E. M. Glass, F. Aslund, O. Schneewind, and D. M. Missiakas. 2004. Staphylococcus aureus virulence genes identified by bursa aurealis mutagenesis and nematode killing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:12312-12317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bae, T., and O. Schneewind. 2006. Allelic replacement in Staphylococcus aureus with inducible counter-selection. Plasmid 55:58-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barekzi, N., K. Beinlich, T. T. Hoang, X. Q. Pham, R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, and H. P. Schweizer. 2000. High-frequency flp recombinase-mediated inversions of the oriC-containing region of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa genome. J. Bacteriol. 182:7070-7074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bera, A., S. Herbert, A. Jakob, W. Vollmer, and F. Götz. 2005. Why are pathogenic staphylococci so lysozyme resistant? The peptidoglycan O-acetyltransferase OatA is the major determinant for lysozyme resistance of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 55:778-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brückner, R. 1997. Gene replacement in Staphylococcus carnosus and Staphylococcus xylosus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 151:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campo, N., M. L. Daveran-Mingot, K. Leenhouts, P. Ritzenthaler, and P. Le Bourgeois. 2002. Cre-loxP recombination system for large genome rearrangements in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2359-2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai, Z., J. C. Sirard, M. Mock, and T. M. Koehler. 1995. The atxA gene product activates transcription of the anthrax toxin genes and is essential for virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 16:1171-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diep, B. A., S. R. Gill, R. F. Chang, T. H. Phan, J. H. Chen, M. G. Davidson, F. Lin, J. Lin, H. A. Carleton, E. F. Mongodin, G. F. Sensabaugh, and F. Perdreau-Remington. 2006. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 367:731-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster, T. J. 2005. Immune evasion by staphylococci. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:948-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Götz, F. 1990. Staphylococcus carnosus: a new host organism for gene cloning and protein production. Soc. Appl. Bacteriol. Symp. Ser. 19:49S-53S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Götz, F., T. Bannerman, and K.-H. Schleifer. 2006. The genera Staphylococcus and Macrococcus, p. 5-75. In M. Dworkin (ed.), Prokaryotes, vol. 4. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Götz, F., and B. Schumacher. 1987. Improvements of protoplast transformation in Staphylococcus carnosus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 40:285-288. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grindley, N. D., K. L. Whiteson, and P. A. Rice. 2006. Mechanisms of site-specific recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75:567-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guérout-Fleury, A. M., K. Shazand, N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 1995. Antibiotic-resistance cassettes for Bacillus subtilis. Gene 167:335-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helmann, J. D. 1995. Compilation and analysis of Bacillus subtilis sigma A-dependent promoter sequences: evidence for extended contact between RNA polymerase and upstream promoter DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:2351-2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iordanescu, S., and M. Surdeanu. 1976. Two restriction and modification systems in Staphylococcus aureus NCTC8325. J. Gen. Microbiol. 96:277-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones, J. M., S. C. Yost, and P. A. Pattee. 1987. Transfer of the conjugal tetracycline resistance transposon Tn916 from Streptococcus faecalis to Staphylococcus aureus and identification of some insertion sites in the staphylococcal chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 169:2121-2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khodakaramian, G., S. Lissenden, B. Gust, L. Moir, P. A. Hoskisson, K. F. Chater, and M. C. Smith. 2006. Expression of Cre recombinase during transient phage infection permits efficient marker removal in Streptomyces. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koehler, T. M., Z. Dai, and M. Kaufman-Yarbray. 1994. Regulation of the Bacillus anthracis protective antigen gene: CO2 and a trans-acting element activate transcription from one of two promoters. J. Bacteriol. 176:586-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lambert, J. M., R. S. Bongers, and M. Kleerebezem. 2007. Cre-lox-based system for multiple gene deletions and selectable-marker removal in Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1126-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, C. Y., S. L. Buranen, and Z. H. Ye. 1991. Construction of single-copy integration vectors for Staphylococcus aureus. Gene 103:101-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy, S. B., and B. Marshall. 2004. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nat. Med. 10:S122-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liberati, N. T., J. M. Urbach, S. Miyata, D. G. Lee, E. Drenkard, G. Wu, J. Villanueva, T. Wei, and F. M. Ausubel. 2006. An ordered, nonredundant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 transposon insertion mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:2833-2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowe, A. M., D. T. Beattie, and R. L. Deresiewicz. 1998. Identification of novel staphylococcal virulence genes by in vivo expression technology. Mol. Microbiol. 27:967-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luong, T. T., and C. Y. Lee. 2007. Improved single-copy integration vectors for Staphylococcus aureus. J. Microbiol. Methods 70:186-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makhlin, J., T. Kofman, I. Borovok, C. Kohler, S. Engelmann, G. Cohen, and Y. Aharonowitz. 2007. Staphylococcus aureus ArcR controls expression of the arginine deiminase operon. J. Bacteriol. 189:5976-5986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marraffini, L. A., A. C. Dedent, and O. Schneewind. 2006. Sortases and the art of anchoring proteins to the envelopes of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70:192-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nordmann, P., T. Naas, N. Fortineau, and L. Poirel. 2007. Superbugs in the coming new decade; multidrug resistance and prospects for treatment of Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus spp. and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in 2010. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:436-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pajunen, M. I., A. T. Pulliainen, J. Finne, and H. Savilahti. 2005. Generation of transposon insertion mutant libraries for gram-positive bacteria by electroporation of phage Mu DNA transposition complexes. Microbiology 151:1209-1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pomerantsev, A. P., R. Sitaraman, C. R. Galloway, V. Kivovich, and S. H. Leppla. 2006. Genome engineering in Bacillus anthracis using Cre recombinase. Infect. Immun. 74:682-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Samuelson, P., M. Hansson, N. Ahlborg, C. Andreoni, F. Götz, T. Bachi, T. N. Nguyen, H. Binz, M. Uhlen, and S. Stahl. 1995. Cell surface display of recombinant proteins on Staphylococcus carnosus. J. Bacteriol. 177:1470-1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schleifer, K.-H., and U. Fischer. 1982. Description of a new species of the genus Staphylococcus: Staphylococcus carnosus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 32:153-156. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schweizer, H. P. 2003. Applications of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Flp-FRT system in bacterial genetics. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 5:67-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song, H., F. Wolschendorf, and M. Niederweis. Construction of unmarked deletion mutants in mycobacteria. In Mycobacterium protocols, 2nd ed., in press. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Sternberg, N., and D. Hamilton. 1981. Bacteriophage P1 site-specific recombination. I. Recombination between loxP sites. J. Mol. Biol. 150:467-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sternberg, N., D. Hamilton, and R. Hoess. 1981. Bacteriophage P1 site-specific recombination. II. Recombination between loxP and the bacterial chromosome. J. Mol. Biol. 150:487-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strauss, A., and F. Götz. 1996. In vivo immobilization of enzymatically active polypeptides on the cell surface of Staphylococcus carnosus. Mol. Microbiol. 21:491-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki, N., S. Okayama, H. Nonaka, Y. Tsuge, M. Inui, and H. Yukawa. 2005. Large-scale engineering of the Corynebacterium glutamicum genome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:3369-3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki, N., Y. Tsuge, M. Inui, and H. Yukawa. 2005. Cre/loxP-mediated deletion system for large genome rearrangements in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 67:225-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takahashi, T., I. Satoh, and N. Kikuchi. 1999. Phylogenetic relationships of 38 taxa of the genus Staphylococcus based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49(Pt. 2):725-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomson, J. G., E. B. Rucker III, and J. A. Piedrahita. 2003. Mutational analysis of loxP sites for efficient Cre-mediated insertion into genomic DNA. Genesis 36:162-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao, J., J. Zhong, Y. Fang, E. Geisinger, R. P. Novick, and A. M. Lambowitz. 2006. Use of targetrons to disrupt essential and nonessential genes in Staphylococcus aureus reveals temperature sensitivity of Ll.LtrB group II intron splicing. RNA 12:1271-1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]