Abstract

Sensitization is a critical unresolved challenge in transplantation. We show for the first time that blockade of CD154 alone or combined with T-cell depletion prevents sensitization. Allogeneic skin grafts were rejected by recipients treated with anti-αβ T-cell receptor (TCR), anti-CD154, anti-OX40L, or anti–inducible costimulatory pathway (ICOS) mAb alone with a kinetic similar to untreated recipients. However, the production of anti–donor MHC antibody was prevented in mice treated with anti-CD154 mAb only, suggesting a specific role for the CD154-CD40 pathway in B-cell activation. The impairment of T cell–dependent B-cell responses by blocking CD154 occurs through inhibiting activation of T and B cells and secretion of IFN-γ and IL-10. Combined treatment with both anti-CD154 and anti–αβ TCR abrogated antidonor antibody production and resulted in prolonged skin graft survival, suggesting the induction of both T- and B-cell tolerance with prevention of allogeneic sensitization. In addition, we show that the tolerance induced by combined treatment was nondeletional. Moreover, these sensitization-preventive strategies promote bone marrow engraftment in recipients previously exposed to donor alloantigen. These findings may be clinically relevant to prevent allosensitization with minimal toxicity and point to humoral immunity as playing a dominant role in alloreactivity in sensitized recipients.

Introduction

Sensitization of patients to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens is among the most critical challenges in clinical transplantation.1–3 Patients with preformed antibodies have higher rejection rates and inferior outcomes for bone marrow transplantation (BMT) and organ transplantation. Most patients with sickle cell disease and thalassemia who are candidates for BMT are sensitized due to chronic transfusion therapy.4 Similarly, in solid organ transplantation, allorejection mediated by preformed antibodies has recently been recognized as a major cause of graft loss in sensitized patients. Although 20% of candidates for renal transplantation are sensitized, they receive less than 3% of available organs.1 The increased use of ventricular assist devices as a bridge to cardiac transplantation also sensitizes these candidates to MHC alloantigens prior to transplantation.5 Methods to prevent sensitization would therefore have a broad therapeutic impact.3

The power of MHC-specific antibodies to destroy vascularized allografts within minutes following transplantation has been appreciated since 1969.6,7 Immunosuppressive drugs have been used to reduce the antibody response to allografts,8,9 but the toxicity associated with the chronic use of these drugs is a significant limitation. Moreover, long-term outcomes are still significantly inferior.10 Induction of mixed allogeneic chimerism has been demonstrated to confer donor-specific tolerance in the setting of allosensitization.8,11 However, to establish mixed chimerism in sensitized recipients, the immune barrier from allosensitization must be overcome.12–14

As the cellular and molecular mechanisms of allosensitization are defined, novel strategies to manipulate these effector pathways have emerged. Our recent work in developing a nonmyeloablative approach to establish chimerism in sensitized recipients found that humoral immunity poses a dominant barrier, with T-cell reactivity secondary, but still significant.12 The costimulatory molecule CD154 is expressed predominantly on activated CD4+ T cells.15 CD40, the receptor for CD154, is constitutively expressed on B cells.16 The CD154-CD40 interaction is required for effective activation of both T and B cells. CD40 engagement by its ligand, CD154, stimulates B-cell proliferation, differentiation, isotype switching, development of germinal centers, and immunologic memory.17 Therefore, we examined whether sensitization could be prevented at the time of exposure to alloantigen by targeting these costimulatory molecule interactions.

We report here for the first time a novel, mechanistically based approach to prevent sensitization to MHC alloantigens. Blockade of CD154-CD40 interactions induced B-cell but not T-cell tolerance during skin grafting, indicating that blockade of CD154 dominantly impairs activation of adaptive humoral immunity. The addition of lymphodepletion using anti-αβ T-cell receptor (TCR) mAb to anti-CD154 mAb induced long-term T- and B-cell tolerance, evidenced by absence of antidonor antibody generation and acceptance of MHC plus minor antigen-disparate skin grafts. Blockade of CD154 inhibited both T- and B-cell activation and decreased production of IFN-γ and IL-10 in T cells. In addition, we show that combined treatment induces nondeletional tolerance, as evidenced by rapid rejection of both secondary and primary prolonged skin grafts and no change in Vβ T-cell repertoire. These preventive treatments promoted the establishment of allogeneic chimerism in recipients initially exposed to donor alloantigens. These strategies may be clinically significant to prevent allosensitization with minimal toxicity, and focus attention on the previously underappreciated humoral arm of adaptive immune responses in vivo.

Methods

Animals

Male C57BL/6 (B6; H-2b) and BALB/cJ (BALB/c; H-2d) mice, B6 congenic CD154-deficient mice (Tnfsf5tm1Imx [CD154−/−, H-2b]), and αβ TCR+ T-cell–deficient mice (C57BL/6-TcrbtmlMom [TCRβ−/−, H-2b]) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were housed in the barrier facility at the Institute for Cellular Therapeutics under specific pathogen–free conditions, and cared for according to National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Sensitization and preconditioning

B6, CD154−/−, or TCRβ−/− recipient mice were sensitized by skin grafts from BALB/c donors by a modification of the method described by Billingham.18,19 Grafts were scored by daily inspection for the first month and then weekly thereafter for rejection. Rejection was defined as complete when no residual viable graft could be detected.

Recipient B6 mice were pretreated intraperitoneally with mAbs of anti–αβ TCR (H57–597: hamster anti–mouse IgG; 100 μg on day 3) and anti-CD154 (MR-1: hamster anti–mouse IgG3; Bioexpress, Lebanon, NH; 0.5 mg on days 0 and 3), anti-inducible costimulatory pathway (ICOS) (7E.17G9 rat anti–mouse IgG2b; Bioexpress; 0.5 mg on day 4, 0.25 mg on days 6, 8, and 10), or anti-OX40L (RM134L: rat anti–mouse IgG2b; Bioexpress; 0.5 mg on day 4, 0.25 mg on days 2, 4, and 6) alone or in combination around time of skin grafting (day 0) from BALB/c. A total of 100 μg per mouse was determined to be required to deplete αβ TCR+ T cells,18 and the doses of anti-CD154, anti-ICOS, or anti-OX40L were chosen based on previous publications.20–22 Relevant amounts of hamster IgG (0.5 mg, days 0 and 3; Bioexpress) were used as an isotype control for anti-CD154 mAb.

Flow cross-match assay

Flow cross-match (FCXM) assays were performed as previously described.12 Sera were taken from mice up to 12 weeks following skin grafting. A total of 0.5 × 106 splenocytes from naive BALB/c mice were incubated with 5 μL sera for 30 minutes. Cells were washed and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated polyclonal goat anti-mouse Ig (Immunology Consultants Laboratory, Newberg, OR), followed by a third incubation with PE-conjugated anti–mouse CD4 plus CD8 (PharMingen, San Diego, CA). Levels of circulating alloantibodies were determined by FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA), gating on the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell fraction, and were reported as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI).

Chimera preparation

Mice were conditioned with 950 cGy total body irradiation (TBI; γ-cell 40; Nordion, Toronto, ON) and received transplants of 15 × 106 or 80 × 106 untreated donor bone marrow cells (BMCs) via lateral tail vein injection between 4 and 6 hours after irradiation as previously described.18 Briefly, tibias and femurs were harvested from donors. Bone marrow was expelled from the bones with medium 199 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) containing 10 μg/mL gentamicin (Life Technologies) and gently processed into a single-cell suspension. The cells were diluted to a final concentration of 15 × 106 BMC/mL or 80 × 106 BMC/mL.

Characterization of chimeras

Recipients were characterized for chimerism using flow cytometry to determine the relative percentages of donor-derived peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) monthly as previously described.18 Peripheral blood was stained with Abs specific for MHC class I Ags of donor (FITC-conjugated anti–H-2Kd) and recipient (PE-conjugated anti–H-2Kb) origin. Nonspecific background staining was controlled using isotype control Ab directed against irrelevant Ag conjugated with the same fluorochrome as the experimental Ab. All mAbs were obtained from BD Biosciences.

Flow cytometric analysis of TCR Vβ families

Peripheral blood (80-100 μL) from unmanipulated hosts (B6), unmanipulated donors (BALB/c), chimeras, or skin graft–tolerant recipients treated with anti-CD154 plus anti-αβ TCR was stained with anti-Vβ5.1/2–FITC (MR9-4), anti-Vβ6–FITC (RR4-7), anti-Vβ8.1/2–FITC (MR-5-2), or anti-Vβ11–FITC (RR3-15) versus antihost H2Kb-PE, anti-CD8–PerCP, and anti-CD4–APC (all from BD Biosciences) for 45 minutes at 4°C. A minimum of 50 000 gated events was collected within the total lymphoid gate. Background staining was determined by FITC-conjugated isotype mAbs. Samples from mixed chimeras were stained 2 months after reconstitution. The samples from skin graft–tolerant mice treated with anti-αβ TCR plus anti-CD154 mAb were also tested 5 to 7 weeks after skin grafting.

CD8 and CD4 effector and central memory T-cell enumeration

Skin grafting was performed (day 0) from BALB/c to B6 mice with or without anti-CD154 mAb treatment (days 0 and 3). Recipient peripheral blood was collected up to 30 days after skin grafting. Cells were stained with anti-CD44–FITC (IM7), anti-CD62L–PE (MEL-14), anti-CD4–PerCP, and anti-CD8–APC (all from BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry was performed using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences). CD4+ or CD8+ cells were analyzed for CD62L and CD44 expression. T effectors and T central memory cells were identified as CD44high/CD62Llow/− or CD44high/CD62Lhigh, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the average plus or minus the standard deviation (SD). The 2-tailed t test (2-sample, assuming unequal variances) was used to evaluate statistical differences. The difference between groups was considered significant at a P value less than .05.

Results

Humoral immunity is impaired in CD154−/− and TCRβ−/− mice

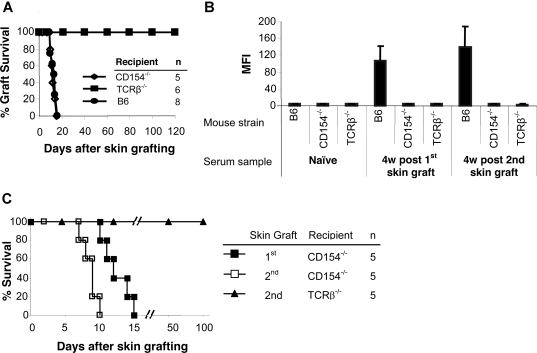

To determine the role of CD154 and αβ TCR T cells in allosensitization, MHC-disparate skin grafts were transplanted onto gene-deleted mice. CD154−/− mice rejected allogeneic skin grafts from BALB/c donors with a time course similar to wild-type B6 recipients (Figure 1A). TCRβ−/− mice accepted allogeneic skin grafts permanently (> 120 days). Donor-specific antibodies were not detected in either group after skin grafting (Figure 1B). Control B6 mice had significantly higher antibody titers after graft rejection.

Figure 1.

TCRβ−/− and CD154−/− mice do not produce antidonor Ab, but only CD154−/− reject skin graft. BALB/c (H-2d) skin grafts were transplanted onto TCRβ−/− and CD154−/− mice (H-2b). At 5 to 7 weeks after the first skin graft, a second BALB/c skin graft was transplanted onto each mouse. Wild-type B6 (H-2b) mice served as controls. (A) Life table analysis of first skin graft survival. All animals were followed up to 120 days. MST was 12.4 (± 2.0) days for CD154−/− and 12.0 (± 2.4) days for wild-type B6 recipients and more than 120 days for TCRβ−/− mice. (B) Sera were collected 4 weeks after first and second skin grafts. Sera collected before the first skin graft served as a control. Sensitization was measured by FCXM assay on sera obtained at selected time points. Levels of circulating alloantibodies were determined by FACSCalibur, gating on the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell fraction, and were reported as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Antidonor Ab titers were tested in TCRβ−/− and CD154−/− mice as well as B6 controls before placement of the donor skin graft (naive sera) or at 4 weeks after first and second skin graft. Data are presented as averages plus or minus SD. (C) Life table analysis of second BALB/c skin graft survival.

To confirm that sensitization had been prevented, a second skin graft was transplanted 5 to 7 weeks after the first. Again, no donor-specific antibody was detected in the TCRβ−/− and CD154−/− mice. In contrast, high levels of antibody were present in B6 controls after rejection of second skin grafts (Figure 1B). CD154−/− mice rejected their second skin graft significantly more rapidly (8.6 ± 1.1 days; P = .01) than their first graft (Figure 1C), while TCRβ−/− mice accepted second skin grafts indefinitely. Therefore, αβ TCR+ T cells play important roles both in allorejection and T cell–dependent B-cell activation, and the CD154-CD40 costimulatory pathway is critically important in B-cell activation for antibody generation.

Combined T-cell lymphodepletion and CD154 blockade prolong the survival of allogeneic skin grafts

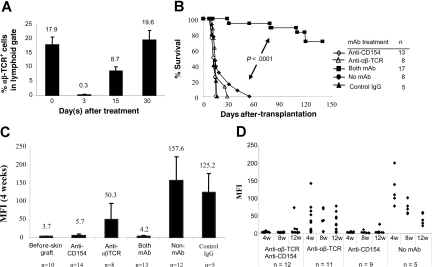

We next examined whether blocking CD154-CD40 interactions in normal recipients would tolerize adaptive B- and T-cell responses that subsequently lead to acceptance of MHC-disparate allogeneic skin grafts. Recipient B6 mice received transplants of BALB/c skin grafts and were conditioned with: (1) anti-αβ TCR mAb; (2) anti-CD154 mAb; or (3) both mAbs at the time of skin grafting. More than 98% of αβ TCR+ T cells were depleted 3 days after anti-αβ TCR treatment (0.3% ± 0.05%) compared with αβ TCR+ T cells on day 0 (17.9% ± 2.8%). One-half of the αβ TCR+ T cells recovered within 15 days, and the population had fully recovered by 30 days (Figure 2A). Similar kinetics of T-cell recovery were observed in the mice treated with anti-αβ TCR combined with anti-CD154 (data not shown).

Figure 2.

αβ TCR T-cell depletion and CD154 blockade in B6 mice prevents sensitization to BALB/c skin graft. BALB/c skin grafts were placed on B6 mice on day 0. Recipient B6 mice were pretreated with anti-αβ TCR mAb (0.1 mg/day; day −3) and/or anti-CD154 mAb (0.5 mg/day; days 0 and 3). (A) Kinetics of T-cell recovery after T-cell depletion with anti-αβ TCR. B6 mice were treated with anti-αβ TCR mAb alone or combined with anti-CD154 mAb. Peripheral blood was obtained on days 0 (before mAb treatment), 3, 15, and 30 after mAb treatment and was stained with PE-conjugated anti-αβ TCR. Data show the percentage of the αβ TCR+ T cells in peripheral lymphoid gate (n = 5-6 mice at each time point). Data are presented as averages plus or minus SD. (B) Survival of BALB/c skin graft in B6 mice treated with anti-CD154 mAb (n = 13) or anti-αβ TCR (n = 8) mAb alone, and both mAbs (n = 17). Recipients without mAb treatment (n = 8) or with control hamster IgG treatment (n = 5) served as controls. The grafts were monitored up to 140 days. (C) Antidonor antibody production after pretreatment with anti-αβ TCR mAb and/or anti-CD154 mAb. Sera were collected 4 weeks after skin graft and analyzed in FCXM assay. Antibody titers were reported as MFI. Data are presented as averages plus or minus SD. (D) Kinetics of antidonor antibody in B6 mice that received transplants of BALB/c skin graft and treated with anti-αβ TCR mAb or/and anti-CD154 mAb at weeks 4, 8, and 12 after skin graft enumerated by FCXM assay. ♦ represents an individual animal.

Donor skin grafts were rejected by untreated recipients with a median survival time (MST) of 13.2 plus or minus 1.5 days (Figure 2B). Recipients pretreated with anti-CD154 or anti-αβ TCR mAb alone rejected their skin grafts with a kinetic similar to untreated or hamster IgG–treated B6 controls (P > .05). Notably, 70.6% of allogeneic skin grafts were significantly prolonged in mice treated with both mAbs (n = 17; P < .001). Therefore, combined T-cell lymphodepletion and CD154 blockade prolonged the survival of MHC-disparate allogeneic skin grafts.

Blockade of CD154-CD40 and depletion of T cells prevents antidonor antibody production

We also measured the levels of antidonor antibody in manipulated mice. Blocking of CD154-CD40 interactions prevented the generation of antidonor antibody (Figure 2C). Antibody titers in mice treated with anti-CD154 mAb alone (MFI, 5.7 ± 3.4; P > .05) were only slightly higher than in naive mice (MFI, 3.7 ± 0.6). In contrast, mice treated with anti-αβ TCR mAb alone produced antidonor antibody at levels significantly greater (MFI, 50.3 ± 44.1; P = .03) compared with naive mice, but significantly lower (P < .001) than that in controls that received skin grafts but no mAb (MFI, 157.6 ± 65.7) or hamster IgG (MFI, 125.2 ± 53.0) treatment.

To test the long-term effect of mAb on prevention of allosensitization, the kinetics of donor-specific antibody titers was examined (Figure 2D). Sera were collected at weeks 4, 8, and 12 after skin graft placement and tested in FCXM assay. In 100% of recipients treated with anti-CD154 combined with anti-αβ TCR mAb (n = 12), antidonor antibody titers were not significantly elevated at week 8, and only 3 of 12 animals had higher antibody titers at 12 weeks. One of 9 mice treated with anti-CD154 mAb alone had slightly elevated antidonor antibody at week 8, and antibody titers increased to a MFI of 26.28 at 12 weeks after skin grafting. The remaining 8 recipients had antibody titers similar to that of naive controls. Antibody generation did not correlate with skin graft rejection, as those 3 mice treated with anti-αβ TCR plus anti-CD154 mAbs that had elevated titers exhibited skin graft prolongation. In contrast, most animals treated with anti-αβ TCR mAb alone generated higher antidonor antibody titers. These data suggest that blockade of CD154 dominantly tolerized the B-cell compartment and prevented generation of antidonor antibody at the time of sensitization.

To exclude a nonspecific effect, we also tested whether blockade of ICOS or anti-OX40L (a member of the TNF superfamily expressed on activated B cells and antigen-presenting cells) would result in a similar outcome. B6 mice pretreated with either of these antibodies alone rejected BALB/c skin grafts with a kinetic similar to B6 controls (Figure S1A, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Recipients of both groups generated significantly higher levels of donor-specific Ab (Figure S1B). Moreover, addition of T-cell depletion with anti-αβ TCR to anti-ICOS or anti-OX40L neither prolonged the survival of allogeneic skin grafts nor prevented the generation of antidonor Ab (Figure S1A,B).

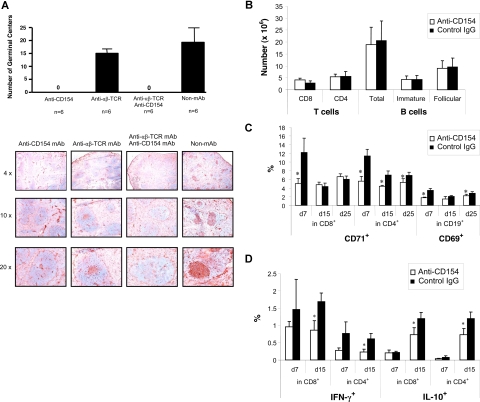

Disruption of CD154-CD40 signaling abrogates germinal center formation

The germinal center is a specialized microenvironment in which antigen-activated B cells proliferate and differentiate into plasma cells and memory B cells. Germinal center formation requires collaboration between activated T cells and B cells in this highly specialized site. Germinal center counts in spleens were performed in mice treated with anti-CD154 alone, anti-αβ TCR alone, or both mAbs 5 to 7 weeks after skin grafting. No germinal centers were generated in mice treated with anti-CD154 or anti-CD154 plus anti-αβ TCR, while those treated with anti-αβ TCR mAb alone produced germinal centers at levels similar to that of sensitized controls (Figure 3A; number/spleen: 13.7 ± 1.5 vs 20.8 ± 3.6). Although the numbers of germinal centers in anti-αβ TCR mAb treated mice were similar to that in sensitized controls, the size of the germinal center was significantly smaller. Moreover, the germinal centers in mice treated with anti-CD154 or anti-CD154 plus anti-αβ TCR mAbs appeared disrupted, as evidenced by the loss of the normal structure (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Blockade of CD154 aborts germinal center formation and inhibits T- and B-cell activation. (A) At 5 to 7 weeks after skin grafting, spleens were harvested form animals treated with anti-CD154 mAb alone, anti-αβ TCR mAb alone, and both mAbs. Untreated B6 mice served as controls. Spleens were suspended in OCT, frozen in 2-methyl-butane, sectioned, and fixed with acetone. The spleen sections were blocked using Tris-saline/3% BSA (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) and incubated with the avidin/biotin blocking kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The sections were stained with HRP-PNA (1:100; Sigma) and developed with the AEC substrate kit (Vector Laboratories). Germinal center counts were performed using a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope (Nikon Instruments, Westchester, OH). The images were captured by Nikon Act-1 for L1 software and further processed by Adobe Photoshop version 9.0.2 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Representative immunohistochemistry of germinal center analyses at 4×, 10×, and 20× for each of the treatment groups is shown. (B) B6 recipients were treated with anti-CD154 or its isotype hamster IgG around the time of skin grafting from BALB/c, and the number of T cells (CD4+ and CD8+), total B cells (CD19+), immature B cells (CD19+CD24highCD23low), and follicular B cells (CD19+CD24lowCD23high) in spleens were enumerated at days 7, 15, and 25 after skin grafting by 4-color flow cytometry. Data from a representative time point, day 15, are presented. (C) The percentages of alloreactive T cells (CD71+) in CD8+ or CD4+ gate and activated B cells (CD69+) in CD19+ gate were detected. (D) CD8 or CD4 T cells from anti-CD154 treated mice or from mice treated with control IgG were assessed with intracellular staining for their ability to express IFN-γ or IL-10. Single-cell suspension of spleen cells was prepared and cultured in complete tissue culture media (RPMI 1640 [Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA] supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum [Valley Biomedical, Winchester, VA], 1 mM sodium pyruvate [Invitrogen], 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin [Invitrogen], and 2 mM l-glutamine [Invitrogen]) for 18 hours. During the final 6 hours of culture, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (50 ng/mL), ionomycin (500 ng/mL), and brefeldin A (10 μg/mL) (Sigma Chemical) were added to the culture. Cells were stained for CD4 or CD8 for 30 minutes at 4°C and then washed and fixed in 2% formaldehyde (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) for 15 minutes at 37°C, followed by ice-cold methanol at 4°C overnight. The cells were washed and permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 (Roche Diagnostic Corp, Indianapolis, IN) in fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) buffer. PE-conjugated anti–IFN-γ, anti–IL-10, or rat-IgG1 mAbs were added to the cells for 30 minutes, followed by washing in Triton X-100–FACS buffer. Significant P values are indicated above the respective data bars (*P < .05). Data are presented as averages plus or minus SD.

CD154 blockade inhibits both T- and B-cell activation and decreases the expression of IFN-γ and IL-10 in T cells

We further evaluated the effect of anti-CD154 mAb on T- and B-cell populations and their phenotypes. There was no significant difference in absolute number of T cells (CD4+ or CD8+) and B cells (total, CD19+; immature, CD19+/CD24high/CD23low; and follicular, CD19+/CD24low/CD23high) between anti-CD154– and control IgG–treated groups at days 7, 15, or 25 after skin grafting (Figure 3B). However, anti-CD154 treatment resulted in a significant reduced activation of alloreactive T and B cells (Figure 3C): the percentage of CD8+/CD71+ was significantly lower at day 7, and the percentages of CD4+/CD71+ were significantly lower at days 7, 15, and 25 compared with control IgG–treated mice (P < .05). The percentages of CD19+/CD69+ at days 7 and 25 were significantly lower compared with control IgG–treated mice (P < .05). To determine effect of anti-CD154 treatment on T helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 cytokine production, intracellular IFN-γ and IL-10 expression was analyzed. As shown in Figure 3D, the IFN-γ expression in both CD8 and CD4 T cells was inhibited at day 7, and the inhibition reached significance (P < .01) at day 15 compared with the control IgG–treated group. The IL-10 expression was similar at day 7 between the 2 groups, but was significantly inhibited in mice treated with anti-CD154 at day 15 in both CD8 and CD4 T cells (Figure 3D). These data suggest that the generation of alloreactive T cells are inhibited by anti-CD154 treatment, which is consistent with a previous report,23,24 and that these effects are dependent on cytokine secretion.

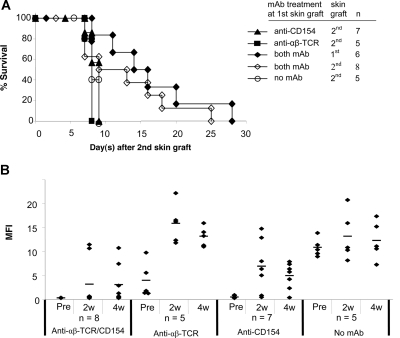

Secondary skin graft survival and donor-specific Ab generation

Acceptance of a second skin graft from the same donor has been considered an important criterion for evaluating donor-specific tolerance.25 A second skin graft was therefore transplanted onto each of the following treatment groups 5 to 7 weeks after placement of the first graft: (1) anti-CD154 alone; (2) anti-αβ TCR alone; or (3) both mAbs. Mice without mAb treatment at the primary skin graft served as controls. All second skin grafts in mice treated with anti-CD154 alone or anti-αβ TCR alone at the time of first skin graft were rejected significantly more rapidly (P < .05) than first skin grafts (Figure 4A vs Figure 2B). A total of 6 of 8 mice treated with both mAbs had the primary skin graft intact when the secondary skin graft was performed. Although survival of second skin grafts was slightly prolonged in mice treated with both mAbs, the second skin graft triggered the rejection of all first skin grafts in this group (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Second skin graft survival and donor-specific antibody generation after the second skin grafting. (A) At 5 to 7 weeks after the first skin graft, a second skin graft was transplanted onto experimental B6 mice treated with anti-CD154, anti-αβ TCR, and/or both mAbs at the time of the first skin grafting. Mice without mAb treatment at the first skin graft served as controls. In mice treated with both mAbs, 6 of 8 mice had the first skin graft intact when the second skin graft was performed. Survival reflects days after placement of second skin grafts. (B) Sera were collected at weeks 2 and 4 after second skin grafting and tested with FCXM assay. The sera collected before second skin grafting served as controls. ♦ represents an individual sample, and the short bar represents the average for each group. Pre indicates pretreatment.

We then tested the mice for production of antidonor antibodies after the second skin grafting (Figure 4B). With anti-CD154 mAb treatment alone, 6 of 7 mice generated antidonor antibody by 2 weeks after the second antigen challenge. Only 1 mouse in this treatment group maintained an unsensitized profile at 4 weeks. Mice treated with anti-αβ TCR mAb alone (n = 5) had higher antibody titers at 2 and 4 weeks after the second skin graft compared with the titers after the first graft. This humoral response was similar to mice that had received no mAb treatment at the time of the first skin graft. With combined mAb treatment, the antibody titers in 2 mice that had rejected their first skin graft increased from normal levels to more than 100 MFI at 2 weeks, and remained at high levels 4 weeks after the second graft. The other 6 mice in this group that had their first skin graft on at the time of placement of the second skin graft maintained nearly normal antibody titers (MFI of 2.5 to 5.9 at 2 weeks), and 4 mice maintained normal antibody titers 4 weeks after the second skin graft even though they had rejected both the first and second grafts. Moreover, the antibody levels were only slightly elevated in the 2 mice with first skin grafts on at the time of second skin grafting (MFIs of 12.6 and 28.3, respectively). Therefore, blockade of CD154 combined with T-cell depletion inhibited generation of allogeneic antibody, even after a second antigen challenge. These data point to a dominant and critical role for CD154 interactions in generating humoral immune responses.

Anti-CD154 mAb alone or in combination with anti-αβ TCR mAb promotes allogeneic bone marrow engraftment in mice after the first skin graft

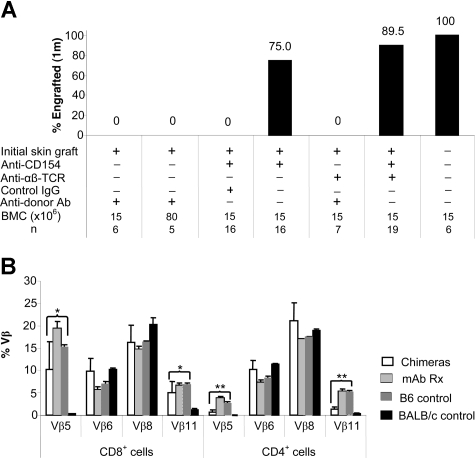

To confirm that anti-CD154 mAb treatment prevented the production of antidonor antibody after skin grafting, and that the addition of anti-αβ TCR to anti-CD154 treatment induced both T- and B-cell tolerance, we tested whether alloengraftment of bone marrow would occur in mice treated with mAb at the time of sensitization. BALB/c BMT was performed 5 to 7 weeks after B6 mice were treated with anti-CD154 mAb alone, anti-αβ TCR mAb alone, or both mAbs at the time of first skin grafting. Naive and sensitized B6 mice without mAb treatment or with hamster IgG treatment at initial skin grafting served as controls. Recipient mice were irradiated with 950 cGy and received transplants of 15 × 106 or 80 × 106 BALB/c BMCs (Figure 5A). Engraftment did not occur in mice treated with anti-αβ TCR mAb alone. As expected, sensitized controls did not engraft.8 In striking contrast, 89.5% mice treated with anti-αβ TCR plus anti-CD154 engrafted, and 75.0% of mice treated with anti-CD154 alone engrafted. Recipients pretreated with anti-ICOS or anti-OX4OL mAb alone or in combination with anti-αβ TCR mAb did not engraft (Figure S1C). These data corroborate our prior findings that the B-cell compartment is dominant in allosensitization in vivo,12 and implicate the CD154-CD40 pathway as critical to sensitization.

Figure 5.

Characterization of allogeneic BM engraftment. (A) BMT was performed 5 to 7 weeks after the treatment with anti-CD154 mAb and/or anti-αβ TCR mAb at the time of initial skin grafting. Naive, sensitized, and control IgG–treated B6 mice served as controls. Recipients were conditioned with 950 cGy TBI and received transplants of 15 × 106 or 80 × 106 untreated BALB/c donor BMCs via lateral tail vein injection 4 to 6 hours after irradiation. Animals were analyzed for engraftment using flow cytometric analysis 4 weeks after BMT by determining the relative percentages of donor-derived PBLs. The results are the summarized from 3 experiments. (B) Relative TCR-Vβ expression. Expression of Vβ5.1/2, Vβ6, Vβ8.1/2, and Vβ11 on PBLs from unmanipulated hosts (B6 [▨]; n = 4), unmanipulated donors (BALB/c [■]; n = 4), mixed chimeras (chimeras [□]; n = 9), or recipients treated with both anti-CD154 and anti-αβ TCR that had skin graft acceptance (mAb Rx ▩; n = 5), was measured by FACS analysis. The chimerism ranged from 65.6% to 93.6% donor. Relative expression in chimeras represents the percentage of Vβ+ cells within the CD8+ or CD4+ T-cell subsets of the host lymphocytes in peripheral blood. Samples from mixed chimeras were stained 2 months after reconstitution. The samples from skin graft–tolerant mice treated with anti-αβ TCR plus anti-CD154 mAb were tested 5 to 7 weeks after skin grafting. Data from 3 experiments are depicted as means plus or minus SD. TCR-Vβ expression in either the chimeric group or the mAb-treated tolerant group was compared with that in B6 mice using the 2-tailed t test (2-sample, assuming unequal variances). Significant P values are indicated above the respective data bars (*P = .02; **P < .001).

Vβ expression in mice treated with anti-αβ TCR plus anti-CD154 mAbs and in chimeric mice

To further investigate the mechanism of tolerance induction in mice treated with combined anti-αβ TCR plus anti-CD154 mAbs, we evaluated the TCR-Vβ repertoire. Animals in this treatment group were compared with the chimeras prepared as described. BALB/c mice express I-E, resulting in the deletion of Vβ5.1/2+ and Vβ11+ T cells; B6 mice do not. In chimeric mice, marginally significant deletion of Vβ5.1/2+ and Vβ11+ subfamilies of CD8+ T cells occurred compared with naive controls (P = .02). There was a significant deletion of Vβ5.1/2+ and Vβ11+ subpopulations of CD4+ T cells in mixed chimeras compared with naive B6 mice (P < .001), indicating that Vβ5.1/2+ and Vβ11+ subfamily deletion occurred completely in CD4+ T cells and only partially in CD8+ T cells. This negative selection was specific, as deletion of Vβ6+ and Vβ8.1/2 subsets was not detected. In contrast, the Vβ repertoire in B6 mice treated with both anti-αβ TCR plus anti-CD154 resembled that for naive B6 mice (Figure 5B), and no deletion of any tested Vβ subfamily was detected.

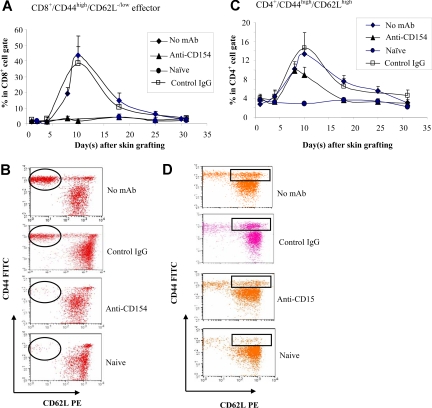

CD154 blockade selectively inhibits the generation of CD8+ effectors

The fact that CD154−/− mice and anti-CD154–treated wild-type mice did not mount antibody response to BALB/c skin graft, but rejected the graft, suggests a role of cell-mediated response. To investigate the role of CD154-CD40 interactions in generating effective T-cell response, B6 mice were treated with anti-CD154 mAb. The CD44high/CD62Llow/− effector T cells and CD44high/CD62Lhigh (central memory) T cells were enumerated in peripheral blood at various times after allo–skin grafting. CD8+ effectors were detected in controls starting at day 8 after graft placement and reached a peak at day 10, then decreased, reaching a level resembling naive mice at day 30 (Figure 6A,B). CD4+ effectors were not inhibited by blockade of CD154 (data not shown). The CD4+/CD44high/CD62Lhigh population was significantly higher in the groups that received no mAb treatment (P < .05) or anti-CD154 treatment (P < .05) compared with naive mice (Figure 6C,D), but the difference of the levels of CD4+/CD44high/CD62Lhigh between the no mAb–treated group and the anti-CD154–treated group was significant (P < .05), suggesting that anti-CD154 partially inhibits the generation of CD4+/CD44high/CD62Lhigh cells. There were no significant changes in CD8+/CD44high/CD62Lhigh in mice treated with anti-CD154 at the initial skin grafting in comparison with naive and sensitized controls (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Memory T-cell development. B6 mice treated with anti-CD154 mAb (days 0, 3) were given transplants of BALB/c skin grafts (day 0). Naive, non-Ab–treated, and control hamster IgG–treated B6 mice served as controls. Recipient peripheral blood was collected at selected time points up to 30 days after skin grafting and stained with anti-CD44–FITC, anti-CD62L–PE, anti-CD4–PerCP, and anti-CD8–APC mAbs. n = 8 mice per group. (A) The kinetics of percentage of effector CD8+ T cells was analyzed (percentage CD44high/CD62Llow/− cells in the CD8+ population). Data are presented as averages plus or minus SD. (B) A representative flow cytometry dot plot of each group for CD8+/CD44high/CD62Llow/− effector cells at day 10 after skin grafting. (C) The kinetics of percentage of CD44high/CD62Lhigh (central memory T-cell phenotype) in the CD4+ population. Data are presented as averages plus or minus SD. (D) A representative flow cytometry dot plot from each group for CD4+/CD44high/CD62Lhigh cells at day 10 after skin grafting. Results are representative of 3 experiments.

Discussion

Sensitization to MHC alloantigens is a critical unresolved challenge in transplantation.26–29 As was highlighted in a recent editorial,3 strategies to prevent sensitization need to be developed. A clear definition of the pathways involved in generating adaptive immune responses in transplantation could have a significant therapeutic impact. Interactions between costimulatory ligands and their receptors are crucial for the induction and regulation of innate and adaptive immune responses and maintenance of self-tolerance.30,31 Stimulation of T cells and B cells through the antigen-specific receptor without engagement of costimulatory molecules can lead to anergy and/or apoptosis,32 resulting in prolonged graft acceptance.33–36 In the present studies, we have found that both T- and B-cell adaptive immune responses must be controlled to prevent sensitization to alloantigen and prolong graft survival in vivo, and show for the first time that selective blockade of CD154 dominantly impairs the generation of humoral immunity.

We first characterized the mechanisms of allosensitization using CD154−/− and TCRβ−/− mice. We found that antidonor Ab was not generated in CD154−/− mice after allogeneic skin graft rejection. However, skin graft rejection occurred with a normal kinetic, suggesting that T cells play a dominant and sufficient role in rejection of allogeneic skin grafts despite the fact that skin grafts induce production of significant amounts of alloantibody in wild-type recipients. Secondary grafts placed on these same CD154−/− recipients were rejected in an accelerated manner (P < .05) compared with the primary graft, suggesting that primed T cells were generated by rejection of the first skin graft. TCRβ−/− mice did not reject their first and second skin grafts, nor did they generate antidonor Ab, demonstrating that T cells play important dual roles in allorejection and in B-cell activation. Therefore, a deficiency in the CD154-CD40 pathway is not sufficient to block T-cell activation, although blocking CD154 exclusively and dominantly impairs generation of B-cell responses.

Based on our findings in CD154−/− and TCRβ−/− mice, we examined whether sensitization could be prevented at the time of exposure to alloantigen by blocking of CD154 with anti-CD154, depletion of αβ TCR+ T cells with anti-αβ TCR, or combining both antibodies. Skin graft survival was significantly prolonged in wild-type recipients treated with anti-CD154 plus anti-αβ TCR mAbs, while grafts were rejected with kinetics similar to untreated controls if they received either mAb alone. Treatment of recipients with anti-CD154 mAb or anti-CD154 plus anti-αβ TCR mAbs prevented generation of germinal centers, suggesting interruption of B-cell activation, while those treated with anti-αβ TCR mAb alone generated germinal centers at levels similar to sensitized controls. The critical role for the CD154-CD40 pathway in mediating humoral immunity was specific to this costimulatory pathway, since blockade of CD40L or ICOS did not result in a similar effect.

There was a striking disparity in skin graft survival between TCRβ−/− and mice treated with anti-αβ TCR. Graft survival was significantly prolonged in the TCRβ−/− mice compared with the mAb-treated wild-type mice. TCRβ−/− mice lack αβ TCR+ T cells, while depletion with anti-αβ TCR may leave some residual T cells below the levels of detectability. We hypothesize that the addition of anti-CD154 mAb prevented those residual T cells from being activated. Our findings are corroborated by a previous report showing that low levels of residual effector cells were sufficient to mediate graft rejection.37 They also provide a mechanistically distinct explanation for the observation that depletion of CD8+ T cells is required to induce tolerance in CD4+ T cells with CD154 blockade.38 While this outcome was previously attributed to an effect by CD154 blockade on T cells, our present findings suggest that the dominant effect is to prevent T cell–dependent B-cell activation in vivo, and is consistent with previous reports evaluating the mechanism of antibody production by B cells.39,40 That anti-CD154 mAb treatment selectively inhibits the generation of CD8+ effectors but does not prevent skin graft rejection further supports this notion.

Interestingly, the anti-CD154 mAb therapy also led to significantly decreased IL-10 production, a cytokine which promotes B-cell activation and differentiation.41,42 Therefore, blockade of CD154 appears to interfere with both allo–T-cell and allo–B-cell activation by inhibiting T-cell and B-cell collaboration. These observations confirm recent publications that allosensitization clearly involves both allo-Ab humoral responses as well as allo–T-cell responses.12,43,44

The accelerated rejection of second skin grafts in both CD154−/− and anti-CD154–treated B6 mice suggests that memory T cells mediate this rejection. Notably, blockade of CD154 totally impaired the generation of CD8+/CD44high/CD62Llow/− effectors, but not CD4+/CD44high/CD62high central memory phenotype cells. This finding may help to explain the mechanism for rejection of skin grafts in the mice lacking or blocking CD154, as CD4+ memory T cells can mediate allograft rejection.45,46 These findings may explain why combined anti-αβ TCR plus CD154 blockade is required to prolong skin graft survival in vivo. To understand the mechanism associated with the inhibition of T- and B-cell activation by blockade of CD154-CD40 interactions, we evaluated activation status and cytokine production. We have also found that anti-CD154–treated recipients had a significant reduction not only in IL-10– but also in IFN-γ–producing cells, suggesting that Th1 responses are inhibited. Therefore, the mechanisms of action for CD154 blockade may be more complicated for first and second graft rejection and for the dissociation T-cell tolerance (skin graft rejection) and B-cell tolerance (inhibition of Ab generation).

It has been hypothesized that costimulatory blockade plus lymphodepletion in the context of exposure to alloantigen induces apoptosis or censoring of alloreactive T cells.47–49 However, the fact that a second skin graft triggered the rejection of all prolonged first skin grafts in recipients suggests that the tolerance induced by this treatment does not occur by a deletional mechanism. There was no change in TCR-Vβ repertoire in these tolerant mice, making a central mechanism less likely. In contrast, TCR-Vβ5 and -Vβ11 deletion in CD4+ T cells was observed in all chimeras prepared with mice following sensitization-preventive treatment. These data confirm that central tolerance through clonal deletion of alloreactive T cells is the mechanism for tolerance induction in chimerism, but not in the nonchimeric mice.

The sensitized barrier has posed a formidable challenge for engraftment of BMCs in patients sensitized by transfusion therapy.14,50 Patients with hemoglobinopathies experience a higher rate of graft rejection, and significantly more conditioning is required to establish chimerism nonmyeloablatively.51 In the present studies, we found that CD154 blockade promoted engraftment in recipients previously exposed to donor alloantigen. Notably, 75% of mice preconditioned with anti-CD154 mAb and 89.5% conditioned with both anti-CD154 plus anti-αβ TCR mAbs at the time of skin graft placement engrafted with a much lower BMC dose. These results confirm that CD154 blockade, with or without anti-αβ TCR mAb preconditioning prior to exposure to MHC alloantigen, abrogates the generation of a humoral response and confirm that sensitization can be prevented in vivo with costimulatory blockade. As expected, none of the sensitized recipients in the present studies prepared as controls engrafted. Similarly, the mice treated with anti-αβ TCR mAb also failed to engraft, confirming a dominant role by the humoral barrier in rejection of transplanted BMCs as antidonor Ab generated after the initial skin graft rejection. In a mouse model of sensitization, we recently reported that the humoral arm of the immune response contributed dominantly to BM graft rejection by sensitized recipients in vivo.12 Although CD154-treated mice rejected their skin grafts, they behaved like unsensitized mice for engraftment of bone marrow, which further supports the dominant and previously unappreciated role for humoral immunity in sensitized recipients. Moreover, these preventative strategies used in recipients at the time of exposure to alloantigens promote the establishment of allogeneic engraftment of BMCs. These findings may be clinically relevant to pre-emptively prevent allosensitization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Haval Shirwan, PhD, for review of the manuscript and helpful comments; Lala-Rukh Hussain for technical assistance; Carolyn DeLautre for manuscript preparation; and the staff of the animal facility for outstanding animal care.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R01 DK52294 and HL63442, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International, the Department of Defense, the Commonwealth of Kentucky Research Challenge Trust Fund, the Jewish Hospital Foundation, and the University of Louisville Hospital.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Author contributions: H.X. helped design experiments, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; J.Y. helped with experimental design, performed support experiments, and interpreted data; Y.H. performed and helped design support experiments; P.C. helped design research, analyze data, and edit the manuscript; C.D. performed and helped design support experiments; C.S. performed supporting experiments, edited the manuscript, and gave feedback in the writing phase; L.W. performed support experiments; and S.I. designed the experiments, interpreted data, and reviewed all data and the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Suzanne T. Ildstad, Director, Institute for Cellular Therapeutics, Jewish Hospital Distinguished Professor of Transplantation, Professor of Surgery, University of Louisville, 570 South Preston Street, Suite 404, Louisville, KY 40202-1760; e-mail: stilds01@louisville.edu.

References

- 1.Blondeau B. The sensitized patient. The Immunology Report. 2005;2:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baid S, Saidman SL, Tolkoff-Rubin N, et al. Managing the highly sensitized transplant recipient and B cell tolerance. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13:577–581. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowler DH. B-ware of allosensitized graft rejection. Blood. 2007;109:851–852. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumpati GS, Cook DJ, Blackstone EH, et al. HLA sensitization in ventricular assist device recipients: does type of device make a difference? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:1800–1807. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joyce DL, Southard RE, Torre-Amione G, et al. Impact of left ventricular assist device (LVAD)-mediated humoral sensitization on post-transplant outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:2054–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel R, Terasaki PI. Significance of the positive crossmatch test in kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1969;280:735–739. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196904032801401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higuchi ML, Bocchi E, Fiorelli A, et al. [Histopathologic aspects of hyperacute graft rejection in human cardiac transplantation. A case report]. Ar Qbras Cardiol. 1989;52:39–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colson YL, Schuchert MJ, Ildstad ST. The abrogation of allosensitization following the induction of mixed allogeneic chimerism. J Immunol. 2000;165:637–644. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaddy RE, Fuller TC, Anderson JB, et al. Mycophenolic mofetil reduces the HLA antibody response of children to valved allograft implantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1734–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pisani BA, Mullen GM, Malinowska K, et al. Plasmapheresis with intravenous immunoglobulin G is effective in patients with elevated panel reactive antibody prior to cardiac transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18:701–706. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(99)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartholomew A, Sher D, Sosler S, et al. Stem cell transplantation eliminates alloantibody in a highly sensitized patient. Transplantation. 2001;72:1653–1655. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200111270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu H, Chilton PM, Tanner MK, et al. Humoral immunity is the dominant barrier for allogeneic bone marrow engraftment in sensitized recipients. Blood. 2006;108:3611–3619. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottlieb M, Strober S, Kaplan HS. Allogeneic marrow transplantation after total lymphoid irradiation (TLI): effect of dose/fraction, thymic irradiation, delayed marrow infusion, and presensitization. J Immunol. 1979;123:379–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tutschka PJ, Santos GW. Bone marrow transplantation in the busulfan-treated rat, II: effect of cyclophosphamide and antithymic serum on the presensitized state. Transplantation. 1975;20:116–122. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197508000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy M, Waldschmidt T, Aruffo A, Ledbetter JA, Noelle RJ. The regulation of the expression of gp39, the CD40 ligand, on normal and cloned CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:2497–2510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van KC, Banchereau J. Functions of CD40 on B cells, dendritic cells and other cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:330–337. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bishop GA, Hostager BS. Molecular mechanisms of CD40 signaling. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 2001;49:129–137. (Warsz.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu H, Chilton PM, Huang Y, Schanie CL, Ildstad ST. Production of donor T cells is critical for induction of donor-specific tolerance and maintenance of chimerism. J Immunol. 2004;172:1463–1471. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Billingham RE. Philadephia, PA: The Wistar Institute Press; 1961. Free skin grafting in mammals. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhai Y, Meng L, Gao F, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Allograft rejection by primed/memory CD8+ T cells is CD154 blockade resistant: therapeutic implications for sensitized transplant recipients. J Immunol. 2002;169:4667–4673. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams MA, Trambley J, Ha J, et al. Genetic characterization of strain differences in the ability to mediate CD40/CD28-independent rejection of skin allografts. J Immunol. 2000;165:6849–6857. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harada H, Salama AD, Sho M, et al. The role of the ICOS-B7h T cell costimulatory pathway in transplantation immunity. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:234–243. doi: 10.1172/JCI17008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwakoshi NN, Mordes JP, Markees TG, et al. Treatment of allograft recipients with donor-specific transfusion and anti-CD154 antibody leads to deletion of alloreactive CD8+ T cells and prolonged graft survival in a CTLA4-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2000;164:512–521. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markees TG, Phillips NE, Noelle RJ, et al. Prolonged survival of mouse skin allografts in recipients treated with donor splenocytes and antibody to CD40 ligand. Transplantation. 1997;64:329–335. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199707270-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tinckam KJ, Sayegh MH. Transplantation tolerance in pediatric recipients: lessons and challenges. Pediatr Transplant. 2005;9:17–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2004.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keown PA. The highly sensitized patient: etiology, impact and management. Transplant Proc. 1987;19:74–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman DF, Lukas MB, Jawad A, et al. Alloimmunization to platelets in heavily transfused patients with sickle cell disease. Blood. 1996;88:3216–3222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warren RP, Storb R, Weiden PL, Mickelson EM, Thomas ED. Direct and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity against HLA identical sibling lymphocytes: correlation with marrow graft rejection. Transplantation. 1976;22:631–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anasetti C, Amos D, Beatty PG, et al. Effect of HLA compatibility on engraftment of bone marrow transplants in patients with leukemia or lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:197–204. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901263200401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenwald RJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. The B7 family revisited. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:515–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watts TH. Tnf/Tnfr family members in costimulation of T cell responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:23–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noel PJ, Boise LH, Thompson CB. Regulation of T cell activation by CD28 and CTLA4. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1996;406:209–217. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-0274-0_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothstein DM, Livak MF, Kishimoto K, et al. Targeting signal 1 through CD45RB synergizes with CD40 ligand blockade and promotes long term engraftment and tolerance in stringent transplant models. J Immunol. 2001;166:322–329. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wekerle T, Kurtz J, Ito H, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation with co-stimulatory blockade induces macrochimerism and tolerance without cytoreductive host treatment. Nat Med. 2000;6:464–469. doi: 10.1038/74731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markees TG, Serreze DV, Phillips NE, et al. NOD mice have a generalized defect in their response to transplantation tolerance induction. Diabetes. 1999;48:967–974. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.5.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Durham MM, Bingaman AW, Adams AB, et al. Cutting edge: administration of anti-CD40 ligand and donor bone marrow leads to hemopoietic chimerism and donor-specific tolerance without cytoreductive conditioning. J Immunol. 2000;165:1–4. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenberg AS, Munitz TI, Maniero TG, Singer A. Cellular basis of skin allograft rejection across a class I major histocompatibility barrier in mice depleted of CD8+ T cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1463–1471. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ito H, Takeuchi Y, Shaffer J, Sykes M. Local irradiation enhances congenic donor pluripotent hematopoietic stem cell engraftment similarly in irradiated and nonirradiated sites. Blood. 2004;103:1949–1954. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawabe T, Naka T, Yoshida K, et al. The immune responses in CD40-deficient mice: impaired immunoglobulin class switching and germinal center formation. Immunity. 1994;1:167–178. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gray D, Dullforce P, Jainandunsing S. Memory B cell development but not germinal center formation is impaired by in vivo blockade of CD40-CD40 ligand interaction. J Exp Med. 1994;180:141–155. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hummelshoj L, Ryder LP, Poulsen LK. The role of the interleukin-10 subfamily members in immunoglobulin production by human B cells. Scand J Immunol. 2006;64:40–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2006.01773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balabanian K, Foussat A, Bouchet-Delbos L, et al. Interleukin-10 modulates the sensitivity of peritoneal B lymphocytes to chemokines with opposite effects on stromal cell-derived factor-1 and B-lymphocyte chemoattractant. Blood. 2002;99:427–436. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor PA, Ehrhardt MJ, Roforth MM, et al. Preformed antibody, not primed T cells, is the initial and major barrier to bone marrow engraftment in allosensitized recipients. Blood. 2007;109:1307–1315. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-022772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagata S, Okano S, Yonemitsu Y, et al. Critical roles of memory T cells and antidonor immunoglobulin in rejection of allogeneic bone marrow cells in sensitized recipient mice. Transplantation. 2006;82:689–698. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000235589.66683.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Q, Chen Y, Fairchild RL, Heeger PS, Valujskikh A. Lymphoid sequestration of alloreactive memory CD4 T cells promotes cardiac allograft survival. J Immunol. 2006;176:770–777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ito T, Ueno T, Clarkson MR, et al. Analysis of the role of negative T cell costimulatory pathways in CD4 and CD8 T cell-mediated alloimmune responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;174:6648–6656. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng XX, Markees TG, Hancock WW, et al. CTLA4 signals are required to optimally induce allograft tolerance with combined donor-specific transfusion and anti-CD154 monoclonal antibody treatment. J Immunol. 1999;162:4983–4990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hancock WW, Buelow R, Sayegh MH, Turka LA. Antibody-induced transplant arteriosclerosis is prevented by graft expression of anti-oxidant and anti-apoptotic genes. Nat Med. 1998;4:1392–1396. doi: 10.1038/3982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hancock WW, Sayegh MH, Zheng XG, et al. Costimulatory function and expression of CD40 ligand, CD80 and CD86 in vascularized murine cardiac allograft rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13967–13972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weiden PL, Storb R, Slichter S, Warren RP, Sale GE. Effect of six weekly transfusions on canine marrow grafts: tests for sensitization and abrogation of sensitization by procarbazine and antithymocyte serum. J Immunol. 1976;117:143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krishnamurti L, Blazar BR, Wagner JE. Bone marrow transplantation without myeloablation for sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:68. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.