Summary

The HIV envelope glycoprotein (Env) is composed of surface (gp120) and transmembrane subunits (gp41), which are non-covalently associated on the viral surface. HIV Env mediates viral entry after undergoing a complex series of conformational changes induced by interaction with cellular CD4 and a chemokine coreceptor. These changes propagate from gp120 to gp41 via the gp120-gp41 interface, ultimately exposing gp41 and allowing it to form the trimer-of-hairpins structure that provides the driving force for membrane fusion. Key unresolved questions about the gp120-gp41 interface include the specific regions of gp41 and gp120 involved, the mechanism by which receptor and coreceptor binding-induced conformational changes in gp120 are communicated to gp41, how trimer-of-hairpins formation is prevented in the prefusogenic gp120-gp41 complex, and ultimately, the structure of the pre-fusion gp120-gp41 complex.

Here, we develop a biochemical model system that mimics a key portion of the gp120-gp41 interface in the prefusogenic state. We find that a gp41 fragment containing the disulfide bond loop and C-peptide region binds primarily to the gp120 C5 region and that this interaction is incompatible with trimer-of-hairpins formation. Based on this data, we propose that in prefusogenic Env, gp120 sequesters the gp41 C-peptide region away from the N-trimer region, preventing trimer-of-hairpins formation until coreceptor binding disrupts this interface. This model system is a valuable tool to study the gp120-gp41 complex, conformational changes induced by CD4 and coreceptor binding, and the mechanism of membrane fusion.

Keywords: HIV, gp120, gp41, viral entry

Introduction

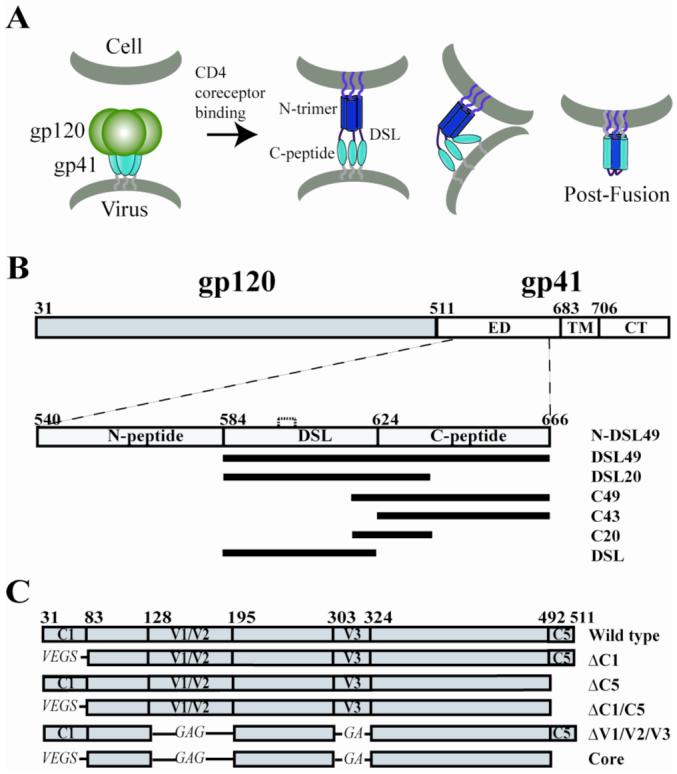

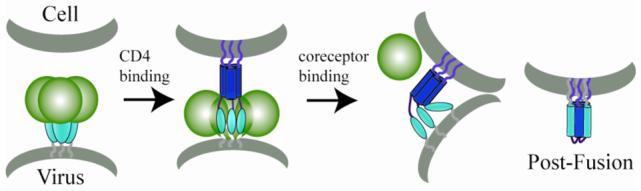

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) enters target cells by fusion of the virus and cell membranes, mediated by the viral envelope glycoprotein (Env). HIV Env is initially synthesized as gp160, which is cleaved by cellular proteases into transmembrane (gp41) and surface (gp120) subunits. After cleavage, gp41 and gp120 remain non-covalently associated and form trimeric spikes on the surface of virions (reviewed in 1,2) (Fig. 1A). gp120 recognizes appropriate target cells by interacting with CD4 and a coreceptor (typically CXCR4 or CCR5). The initial binding of CD4 induces a major conformational change in gp120 that creates and exposes the coreceptor binding site 1,3-5. Subsequent coreceptor binding induces additional poorly characterized conformational changes in the gp120-gp41 complex that are required for membrane fusion and viral entry.

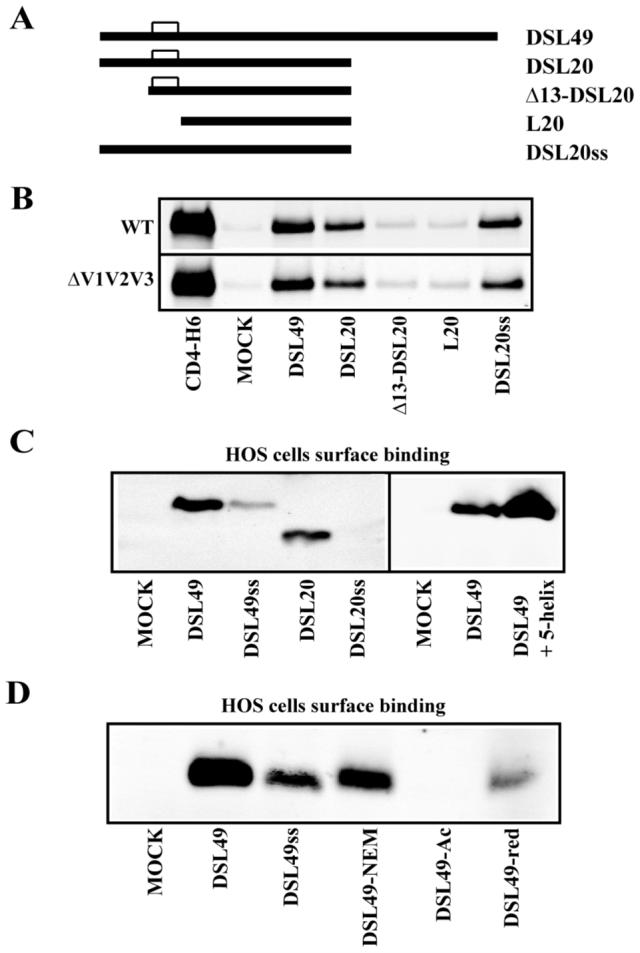

Figure. 1. HIV entry model and schematic of gp41 and gp120 fragments.

(A) Working model of HIV entry. (B) Schematic of gp41 fragments. gp41 consists of the ectodomain (ED), transmembrane domain (TM), and cytoplasmic tail domain (CT). Constructs N-DSL49 (540-666), DSL49 (584-666), DSL20 (584-637), C49 (618-666), C43 (624-666), C20 (618-637), and DSL (584-622) are shown. DSL has one intramolecular disulfide bond, indicated by the dashed line between Cys598 and 604. All gp41 fragments contain a C-terminal His-tag. (C) JRFL-gp120 deletion constructs. ΔC1 (33-82), ΔC5 (493-511), ΔV1/V2 (128-194), and ΔV3 (303-323) are indicated. For ΔC1, ΔV1/V2 and ΔV3, the deleted loops are substituted with GS, GAG and GA, respectively. Core gp120 contains all of the deletions (ΔV1/V2/V3 and ΔC1/C5). Amino acid numbering is based on the prototypic HXB2 gp160 sequence.

Membrane fusion is directly mediated by gp41, which contains an ectodomain (ED), transmembrane domain (TM), and long cytoplasmic tail domain (CT) (Fig. 1B). The ED can be further divided into several regions, listed from N- to C-terminus: the hydrophobic fusion peptide (FP), N-peptide region, disulfide bond loop (DSL), C-peptide region, and membrane proximal domain. Currently, only the post-fusion structure of gp41 is known. In this structure, three N-peptides form a central parallel trimeric coiled-coil that is surrounded by three antiparallel C-peptides, forming a very stable six-helix bundle structure (also known as trimer-of-hairpins) 6-9. Before formation of this six-helix bundle, gp41 transiently adopts an extended conformation (prehairpin intermediate), in which the N-peptide trimer (N-trimer) has formed, but the C-peptide regions have not yet associated with it. This intermediate state of fusion is vulnerable to inhibition by peptides that bind to the N- or C-peptide regions (including the HIV entry inhibitor, T20/Fuzeon) 10-14.

Formation of the six-helix bundle provides the driving force for membrane fusion by bringing the viral and cellular membranes (attached by the TM and FP, respectively) into close apposition (reviewed in 15) (Fig. 1A). gp41 stores energy for fusion by initially separating the N- and C-peptide regions and preventing them from forming the stable six-helix bundle until after CD4 and coreceptor engagement of gp120 triggers fusion at the appropriate time and place. The least understood component of the pathway is the prefusogenic gp120-gp41 complex, which has resisted high-resolution structural analysis. A key unanswered question is how the gp120-gp41 interface maintains gp41 in its metastable prefusogenic conformation (i.e., preventing formation of the very stable trimer-of-hairpins structure).

gp120 contains five conserved constant regions, C1 to C5, and five variable loop regions, V1 to V5 16. The most direct evidence implicating specific regions of Env in the gp120-gp41 interface comes from SOS-Env, which contains an engineered disulfide bond between the gp41 DSL and gp120 C5 regions. These regions are spatially close enough to form an intermolecular disulfide bond in the native prefusogenic state of Env 17. The C1 region of gp120 is also thought to be a contributor to the gp120-gp41 interface because mutations that cause gp120 “shedding” from gp41 on the viral surface are predominantly localized to this region as well as C5 of gp120 and the DSL region of gp4118-23. However, many of these Env mutants are also associated with poor proteolytic processing, expression, or trafficking, suggesting global Env misfolding in a substantial fraction of Env rather than direct disruption of the gp120-gp41 interface. In addition, since even a significant fraction of wild type Env on the viral surface is misfolded or unprocessed 24, cell/virus-based studies do not provide clear data on the nature of the gp120-gp41 interface in properly folded Env.

The main obstacle to a detailed understanding of the gp120-gp41 interface has been the lack of high-resolution structural information. Existing HIV Env structures have been extremely informative, but only reveal the gp41 post-fusion state (six-helix bundle) 6-9 or the “core” structure of gp120 (excluding most of the variable loops and the C1/C5 regions) 5,25,26. Unfortunately, all currently available gp120 structures lack the N- and C-terminal regions most likely to participate in the gp120-gp41 interface. An NMR structure of the isolated C5 region peptide has been determined using trifluoroethanol (TFE) to induce secondary structure in the otherwise disordered C5 peptide 27, but the relevance of this structure under native conditions is not known.

Initial studies on the gp120-gp41 interaction implicated CD4 binding as the trigger for gp120-gp41 dissociation, since exposure to soluble CD4 (sCD4) caused “shedding” of gp120 (e.g., 3,28). However, this conclusion has been supplanted by more recent work showing that sCD4-induced shedding is not physiologically relevant to the fusion pathway of primary isolates and may be an artifact due to the significant population of misfolded Env present on virus and cell surfaces2,24,29,30.

In order to better define the gp120-gp41 complex and study its conformational changes during the entry process, we have developed a stable biochemical model system of this interface. First, we have identified gp41 fragments that bind to gp120 and mimic a major portion of the prefusogenic gp120-gp41 interface. Second, using these fragments, we have characterized the regions of gp41 and gp120 contributing to this interface. Finally, we used these fragments to study conformational changes in gp41 affecting the gp120-gp41 interface and changes of the complex by CD4 binding. Most interestingly, this study suggests a mechanism for the separation of the gp41 N- and C-peptide regions in the prefusogenic conformation of the gp120-gp41 complex. This biochemical model system will also likely find broad utility in future mechanistic and structural studies of the gp120-gp41 interface.

Results

Identification of gp41 fragments that bind to gp120

In this study, we employ gp120 from JRFL (a standard primary HIV-1 isolate) for two main reasons. First, primary isolates of HIV-1 do not suffer from the gp120 shedding artifact seen in many lab-adapted isolates in the presence of soluble CD4 (sCD4)31. As a typical primary R5 strain, JRFL is more likely to reflect the gp120-gp41 interaction of clinical isolates. Second, a previously studied C-peptide, T20, has been reported to bind in a non-specific manner to the V3 loop of X4 strain gp120 in the presence of sCD4, but not to R5 strain gp120 32,33.

We constructed a variety of HIV-1 gp41 fragments (named as shown in Fig. 1B) to find those that bind to JRFL gp120 and potentially mimic the gp120-gp41 binding interface. Importantly, to prevent gp41 trimer-of-hairpins formation, we avoided including both N- and C-peptide regions in the same fragment. We excluded the N-peptide region from further studies based on preliminary screening that showed that gp41 fragments containing both the N-peptide and DSL regions did not interact with gp120 (data not shown). Therefore, our main series of fragments focused on the DSL and C-peptide regions.

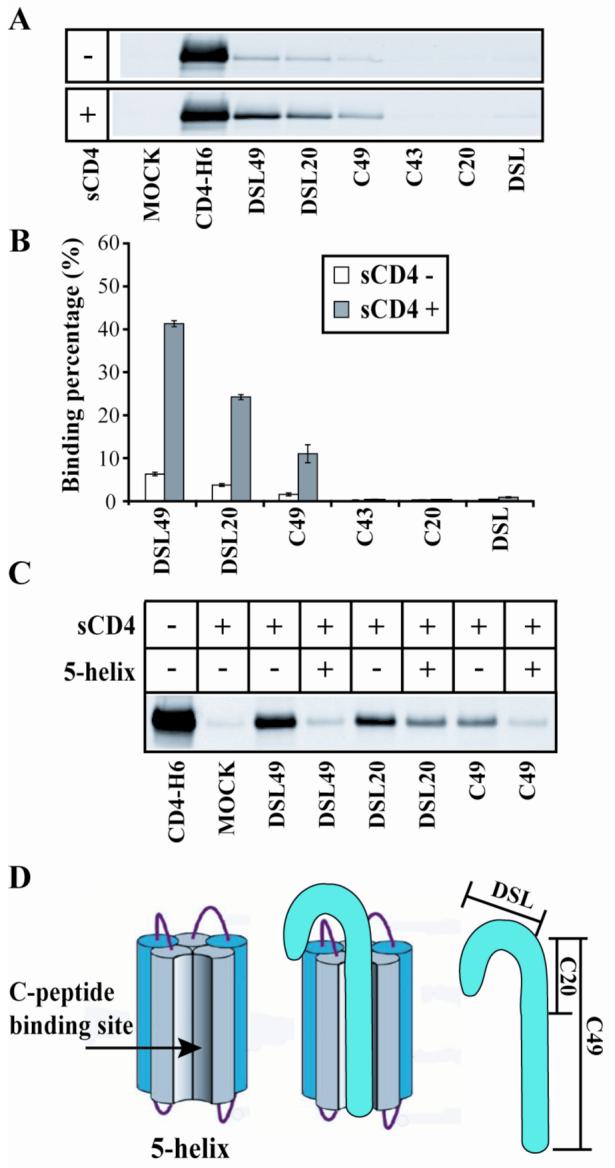

DSL49, DSL20, and C49 show weak binding to gp120, which is significantly enhanced in the presence of sCD4 (Fig. 2A and B). Both with and without sCD4, DSL49 shows the strongest binding, followed by DSL20 and C49, while DSL, C20, and C43 do not show detectable binding to gp120. Thus, the N-terminal part of the C-peptide region has a significant role in this interaction, as shown by the increased binding of DSL20 vs. DSL and C49 vs. C43. The increased binding of DSL49 compared to DSL20 also suggests a contributing role of the C-terminal part of the C-peptide region.

Figure. 2. Binding of gp41 fragments to gp120.

(A) gp41 fragments were incubated with gp120 in the presence or absence of untagged sCD4 and precipitated with Ni++ beads. Eluents were deglycosylated and analyzed by non-reducing SDS-PAGE Western blot with anti-gp120 antibody. Mock lane contains gp120 without any gp41 fragment. (B) Quantification of monomeric gp120 binding from panel A. Binding percentage was normalized to the amount of gp120 amount precipitated by CD4-H6 in the absence of untagged sCD4. (C) DSL49, DSL20, and C49 incubated with gp120 in the presence or absence of sCD4 and 5-helix as indicated. (D) Schematic diagram of 5-helix binding to gp41 fragments.

Maintaining the metastable prefusogenic gp41 conformation

For trimer-of-hairpins formation and membrane fusion to occur at the appropriate time and place, the N- and C-peptide regions must be prevented from associating until after both CD4 and coreceptor bind to gp120. The interaction we observed between C-peptide containing fragments (DSL49, DSL20, and C49) and gp120 suggests a possible mechanism for the sequestration of the C-peptide region from the N-peptide region. To test this idea, we measured the interaction of our gp41 fragments with gp120 in the presence of 5-helix. 5-helix is an engineered protein that binds to C-peptides with high (sub-pM) affinity to reconstitute the six-helix bundle (Fig. 2D) 10. The addition of 5-helix to DSL49 or C49 dramatically decreased their interaction with gp120 (Fig. 2C). In order to show that this effect was not induced by competitive binding of 5-helix to gp120, we used glutaraldehyde crosslinking to monitor the interaction of 5-helix and gp120. While DSL49 made a crosslinked complex with gp120 and sCD4, 5-helix could not (data not shown). DSL20′s interaction with gp120 was also decreased by 5-helix, but less dramatically than for DSL49 and C49 (Fig. 2C). This smaller decrease likely results from DSL20′s partial C-peptide sequence, which reduces its binding affinity for 5-helix. These results show that the six-helix bundle conformation of gp41 is not compatible with the stable formation of the interface between our gp41 fragments and gp120, supporting the idea that this interface sequesters the C-peptide region and prevents six-helix bundle formation.

The gp120 C5 region forms the main interaction interface with gp41 fragments

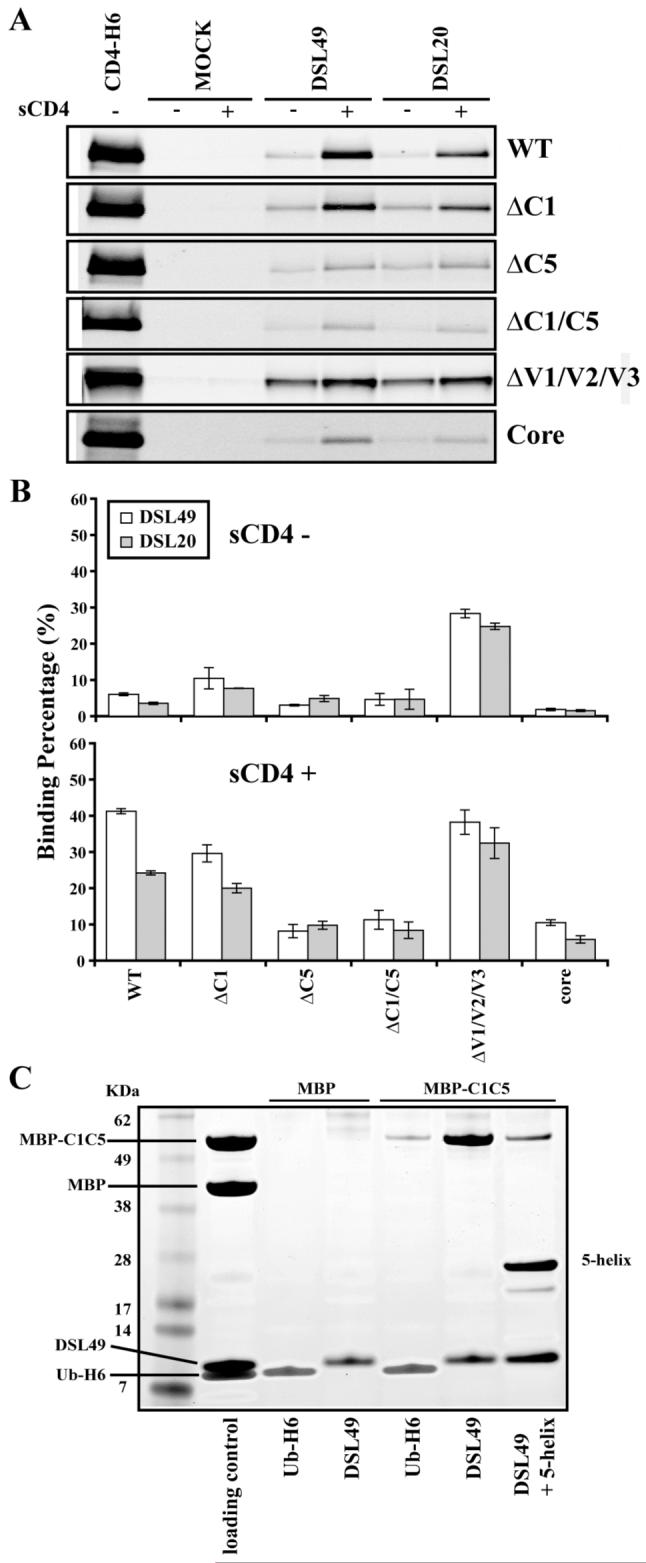

To define the binding site for our gp41 fragments in gp120, we examined a series of gp120 deletion constructs (Fig. 1C). Each deletion mutant was incubated with DSL49 and DSL20, which show the strongest interaction with wild type (wt) gp120 (Fig. 2A and B). First, ΔC1-gp120, ΔC5-gp120 and ΔC1/C5-gp120 were examined, since the C1 and C5 regions have been previously suggested to participate in the gp120-gp41 interface. In the presence of sCD4, ΔC5 and ΔC1/C5 show significantly weakened interactions, while ΔC1 is only slightly weakened compared to wt gp120 (Fig. 3A and B). These results indicate that the gp120′s C5 region is critical for DSL49 or DSL20 binding, while the C1 region is of lesser importance.

Figure. 3. Interaction between gp41 fragments and gp120 deletion mutants or MBP-C1/C5.

(A) gp120 deletion constructs were co-precipitated with DSL49 and DSL20 ± sCD4 as described in Fig. 2A. (B) Quantification of monomeric gp120 binding from panel A, normalized as in Fig. 2B. (C) Co-precipitation of 10 μM MBP or MBP-C1/C5 with 2 μM DSL49. As a negative control, His-tagged ubiquitin (Ub-H6) was used. Loading control contains 1 μM MBP and MBP-C1/C5 (corresponding to 50% of maximal binding to 2 μM DSL49) and 2 μM DSL49 and Ub-H6 (100% of maximal binding). Precipitated proteins by Ni++ beads were analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Next, the contribution of gp120′s variable loops was examined using ΔV1/V2/V3-gp120 and core-gp120 (ΔV1/V2/V3/C1/C5) (Fig. 3). In the absence of sCD4, ΔV1/V2/V3-gp120 showed stronger binding than wt gp120 to DSL49 and DSL20, but core-gp120 only showed a very weak residual interaction, similar to ΔC1/C5-gp120. In the presence of sCD4, ΔV1/V2/V3-gp120 and wt gp120 showed similar binding to DSL20 and DSL49, while core-gp120 only bound weakly. These results indicate that the main variable loops of gp120 (V1/V2/V3) are not required for the interaction with our gp41 fragments, in contrast to the previously reported nonspecific T20 binding to X4 strain gp120 32,33.

To confirm that the gp120 regions identified by screening with deletion mutants bind to DSL49 specifically, we produced C5 and C1/C5 fragments of gp120 fused to the C-terminus of maltose binding protein (MBP-C5 and MBP-C1/C5, respectively). MBP is commonly used as a fusion partner and aids the production, detection, and solubility of these small peptide fragments. DSL49 showed strong binding to MBP-C1/C5 (Fig. 3C), but did not bind to MBP-C5 (data not shown). This interaction was reduced by the addition of 5-helix, as observed with binding to gp120 (Fig. 2C). As an additional control, we observed that sCD4 had no effect on this interaction, as expected since MBP-C1/C5 lacks the CD4 binding site of gp120 (data not shown). Although C1 did not show a major role on the interaction with DSL49 in the context of gp120, C1 may help stabilize or solubilize the isolated C5 fragment in the context of our MBP construct.

Mapping the minimal determinants of gp41 fragment binding to gp120

We further dissected DSL20 to determine the minimal fragment capable of interacting with gp120. First, we investigated the role of the DSL N-terminal region on gp120 binding by truncating the N-terminus of DSL20 (Fig. 4A). Both 13 and 20 residue deletion mutants (Δ13-DSL20 and L20, respectively) dramatically decreased interaction with both wt and ΔV1/V2/V3-gp120 (Fig. 4B) compared to DSL20, indicating that the N-terminal 13 residues of DSL20 are required for this interaction. Next, we tested the role of the disulfide bond in DSL20 by mutating both Cys to Ser to produce DSL20ss (Fig. 4A). DSL20 and DSL20ss showed similar binding affinity for both wt and ΔV1/V2/V3-gp120 (Fig. 4B), indicating that the DSL disulfide does not play a significant role in binding gp120.

Figure. 4. Binding of DSL20 mutants to gp120 and cell surface.

(A) DSL20 mutant constructs: Δ13-DSL20 (597-637), L20 (605-637) and DSL20ss (C598S and C604S). (B) DSL49, DSL20, and DSL20 mutants were incubated with gp120 in the presence of sCD4. Mock lane contains only gp120 and sCD4. (C) Binding of DSL49, DSL49ss, DSL20, and DSL20ss to HOS cells. Right panel shows the effect of 5-helix addition on cell surface binding. Bound proteins on the cell surface were analyzed by Western blot with anti-His tag antibody. Mock lanes were prepared without addition of gp41 fragment. (D) Binding of DSL49, DSL49ss, DSL49-NEM, DSL49-Ac, and DSL49-red to HOS cells.

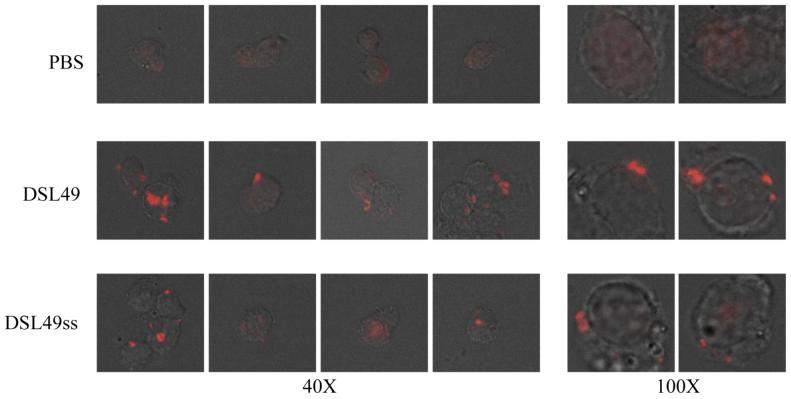

Since the DSL disulfide is highly conserved in all known HIV and SIV strains 8,34, it likely plays a critical role in Env function. Previous studies reported that peptides from the DSL region may bind directly to membranes 35,36. To address the specific role of the disulfide bond in DSL, we measured the binding of DSL20 and DSL49 to cellular membranes. DSL49 and DSL20 both showed significant cell surface binding by Western blot (Fig. 4C). This result was confirmed by cell surface immunostaining, which also revealed a punctate binding pattern (Fig. 5). In contrast, C49 shows minimal cell surface binding (data not shown).

Figure 5. Immunostaining of DSL49 and its DSL49ss on cellular membrane.

DSL49 or DSL49ss was incubated with HOS-pBABE cells and stained with rabbit anti-His6 antibody and Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit antibody. Cells were placed on the slide and photographed at 40X and 100X magnification.

To further examine the role of the DSL disulfide bond in mediating membrane binding, we disrupted the disulfide bonds using: mutagenesis (DSL49ss, DSL20ss), reduction (DSL49-red), and reduction with blocking by the hydrophobic N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) and hydrophilic iodoacetate (Ac) to produce DSL49-NEM and DSL49-Ac, respectively. DSL20ss, DSL49ss, and DSL49-red bound to the cell surface much less efficiently (Fig. 4C and 5). DSL49-Ac also bound the cell surface very weakly (Fig. 4D). In contrast, DSL49-NEM displayed more cell surface binding than DSL49ss, DSL49-Ac, and DSL49-red. These results indicate that the DSL disulfide’s hydrophobic character is likely the most important determinant for membrane binding, since the introduction of more polar groups (e.g., reduced Cys, Ser or Ac) are disruptive than hydrophobic substitutions (e.g., oxidized Cys or NEM). In addition, the cell surface binding of DSL49 and DSL20 is distinct from their binding to gp120, which is not affected by mutagenesis of the DSL disulfide bond (Fig. 4B). This conclusion is further supported by the cell surface binding of DSL49 in the presence of 5-helix (Fig. 4C), which actually enhances cell surface binding, possibly due to induced helical structure or enhanced solubility (a similar enhancement is seen with DSL49ss, data not shown).

Discussion

The gp120-gp41 interface has resisted detailed biochemical and structural characterization for several reasons including: (1) the fragility of the native gp41 conformation (due to its metastability and strong tendency to adopt the post-fusion six-helix bundle structure); (2) the flexible nature of gp120 regions participating in this interface (requiring their removal for crystallography 5,25,26); and (3) a lack of detailed understanding of the residues in gp120 and gp41 participating in this interface (due to challenges in interpreting Env mutants in vivo). The structural and mechanistic details of how the gp120-gp41 interface is affected by receptor and coreceptor binding during HIV entry are also poorly understood. In this work, we make significant progress towards overcoming these barriers by developing a stable biochemical system that partially mimics the gp120-gp41 interface. Using this system, we strengthen previous findings that the gp120 C5 and gp41 DSL regions contribute to the gp120-gp41 interface. The value of this biochemical system is demonstrated by our new findings that the C-peptide region makes a key contact with the gp120 C5 region and that this interaction may be responsible for sequestering the C-peptide region and preventing six-helix bundle formation in the prefusogenic state.

Conformational changes during fusion

HIV Env undergoes complex and extensive conformational changes upon interaction with CD4 and coreceptor. How and when conformational changes in gp120 are transmitted to gp41 via their interface are important unanswered questions. For completion of membrane fusion, the interaction between gp41 and gp120 must be weakened to allow formation of the six-helix bundle. Strong evidence for this requirement is provided by SOS-Env, which can only mediate membrane fusion when its engineered gp120-gp41 disulfide bond is broken with a weak reducing agent 37,38. Coreceptor binding is likely the most critical step in the fusion pathway since several CD4-independent Envs can fuse, but no coreceptor independent strains have yet been identified.

Our biochemical results show that the C-peptide region of gp41 maintains binding to gp120 after sCD4 binding, but this interaction must ultimately be dissociated to allow formation of the trimer-of-hairpin structure that mediates membrane fusion. Coreceptor binding to gp120 is the most likely remaining stimuli that can induce this conformational change. Using the data obtained here and in previous studies, we propose a modified model for the gp120-gp41 interface and how this interface responds to CD4 and coreceptor binding. In the native (prefusogenic) state, the DSL and C-peptide regions interact with gp120 primarily via the C5 region. Interaction of the C-peptide region with gp120 can sequester it and prevent formation of the six-helix bundle until coreceptor engagement disrupts this interface and liberates the C-peptide region (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Revised model of HIV entry.

Based on the results of this study, we propose this altered model of HIV entry. CD4 binding induces formation of the pre-hairpin intermediate, in which the N-trimer region is exposed and the fusion peptide embedded in the target cell membrane. In this intermediate, the DSL and C-peptide regions of gp41 interact with gp120, preventing association with the N-trimer region. Coreceptor binding to gp120 triggers conformational changes that weaken the gp120/gp41 interface. The liberated C-peptide region can then interact with the N-trimer region to form the trimer of hairpins structure, leading to membrane fusion and viral entry.

In support of this idea, a recent report by Root and co-workers shows that the C-peptide region is accessible to inhibitors for a much shorter period of time (seconds) then the N-peptide region (minutes) during fusion 39. This observation is consistent with the sequestration of the C-peptide region by gp120 that we observe here. If coreceptor binding triggers the dissociation of the C-peptide from gp120, the short kinetic window of C-peptide accessibility to 5-helix may reflect the time needed to form the 6-helix bundle after the C-peptide is liberated from its interaction with gp120.

Role of the V1/V2 loops in the gp120-gp41 interface

Most interactions between our gp41 fragments and gp120 are strengthened by sCD4 binding. This result may seem surprising in the context of earlier studies showing sCD4-induced shedding of gp120 in lab-adapted strains 3,28. However, the impact of CD4 binding on the gp120-gp41 interaction in properly folded Env from primary strains is currently unknown. There is strong evidence that sCD4 binding alone is insufficient to release gp120 from gp41, including the ability of HIV to enter CD4(-) cells when sCD4 is provided in trans (sCD4-activated fusion) 40 and the existence of CD4-independent HIV strains 41. The sCD4-induced enhancement of binding may be explained by two possibilities. First, unliganded monomeric gp120 is known to have a flexible structure that is significantly rigidified upon CD4 or antibody binding 42, which may stabilize the monomeric gp120-gp41 interface. Second, sCD4 binding also triggers specific conformational changes in monomeric gp120 that may facilitate the gp120-gp41 interaction in this biochemical system.

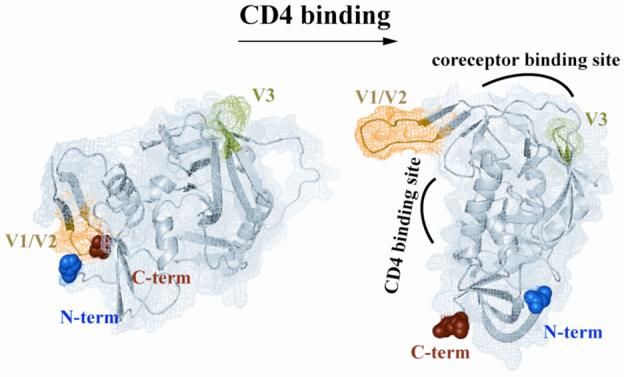

To help explain the effect of sCD4 binding on the monomeric gp120-gp41 interaction, we compared crystal structures of unliganded and sCD4-bound core gp120 (ΔC1/C5/V1/V2/V3) (Fig. 6). In the unliganded gp120 structure, the V1/V2 stem is located near the N- and C-termini (C1 and C5 stumps), which may allow the V1/V2 loop to occlude the C1/C5 region when the ∼80 deleted residues of V1/V2 are present. In the sCD4-bound gp120 structure, the V1/V2 stem undergoes a dramatic movement away from the N/C-terminal region and is now located near the V3 loop and coreceptor binding site 43. If the V1/V2 loop obstructs gp41 fragment binding in unliganded gp120, we would expect either sCD4 binding or V1/V2 loop deletion to enhance gp41 fragment binding, consistent with our data (see Fig. 3). In support of this idea, deletion of the V1/V2 loop has been shown to functionally substitute for CD4 binding in exposing the coreceptor binding site of the MAb 17b 44.

Figure 6. CD4-induced conformational changes in gp120.

Structural comparison between unliganded (left) and CD4-bound gp120 (right). Structures are rendered from PDB accession numbers 2BF1 and 1RZJ, respectively 5,26, using PyMol. Blue and red spheres indicate N-terminus and C-terminus, respectively. Yellow and green indicate V1/V2 stem and V3 stem, respectively.

In the context of trimeric gp41 interacting with three gp120 proteins, it is very likely that gp120 also makes important intersubunit contacts to stabilize the trimeric spike. One cryo-EM model of trimeric gp120 has been proposed in which the V1/V2 loop contacts the V3 loop of a neighboring gp120 within the trimer 5,45. If the V1/V2 loop is involved in such an intermolecular interaction, this alternate conformation would explain why the monomeric gp120-gp41 interaction appears relatively weak in the absence of sCD4 (in our system), but is more robust on the virion surface. In the monomer, the V1/V2 loop appears to obscure the gp41 interface region, but in the context of a trimer, the V1/V2 loop would be removed from this interface by lateral contacts with neighboring gp120s.

Roles of the DSL region disulfide bond

The intramolecular disulfide bond in the DSL region is highly conserved and thought to be important for the structure and function of HIV Env 8,34,46. Although gp41 can adopt a post-fusion six-helix bundle structure without this disulfide 8, it is currently thought to exist in the prefusogenic gp41 structure 47. The functional role of this disulfide bond in HIV entry has been difficult to assess because mutations of these cysteines or intermolecular disulfide bond formation have been shown to disrupt Env proteolytic processing and trafficking 46,48-50. Several studies have reported that the DSL region exhibits membrane binding properties 35,36. Membrane binding of the DSL region could provide additional force right before membrane fusion by bringing viral and target cell membranes more closely together 35,51. Here, we show that the DSL disulfide is not required for gp120 binding, but does play a role in cell surface binding. Interestingly, the cell surface interaction is affected by the hydrophobicity of the disulfide region rather than by formation of the disulfide itself. The cell surface binding properties of DSL49 are not disrupted by six-helix bundle formation, providing additional evidence that DSL49′s cell surface and gp120 binding interactions are distinct. This result also implies that the cell surface binding interaction can be maintained late in the fusion reaction after six-helix bundle formation. Our gp41 fragment model system will be useful for dissecting the distinct properties of gp120 and cell binding to study how they relate to Env trafficking, processing, and fusion activity.

Overcoming barriers to obtaining a high-resolution gp120-gp41 interface structure

In contrast to the intrinsically flexible variable loops of gp120, the flexibility of the gp120 C1 and C5 regions in monomeric gp120 is likely due to the absence of their natural binding partner, gp41. Binding of these regions to an appropriate gp41 fragment may stabilize these regions and allow structural characterization of the gp120-gp41 interface. Further work will be required to achieve this goal, including optimization of fragment solubility and complex stability, possibly via covalent linkage (e.g., crosslinking or flexible linker).

Limitations of our biochemical system

An important caveat for interpreting these studies is that DSL49 likely does not mimic the entire gp120-gp41 interaction interface, due to the absence of the gp41 FP and N-peptide regions. Biochemical studies of the FP’s role in the gp120-gp41 interface are hampered by its poor solubility (leading to its absence in these studies). The fusion peptide ultimately inserts into the target cell membrane, but its status during each step of the entry pathway is poorly understood. In preliminary studies, the N-peptide region did not interact with gp120. However, it remains possible that portions of the N-peptide region, when combined with the DSL and C-peptides regions, may contribute to the stability of the gp120-gp41 interface. Finally, while we find a limited role for the gp120 C1 region in this study, it may stabilize the gp120-gp41 interaction on virions via contacts with the gp41 FP or N-peptide regions.

The trimeric Env complex is thought to be stabilized primarily by gp41-gp41 interactions, since gp120 is monomeric in solution. Ultimately, trimeric gp120-gp41 must be studied for a full understanding of HIV’s entry mechanism. The nature of gp41′s trimerization in the prefusogenic state is currently unknown, though experiments with engineered disulfide bonds show that the N-peptide region is in a different conformation than in the six-helix bundle 52. Recently, Wyatt and co-workers described a trimeric gp120 construct, stabilized by an appended C-terminal coiled-coil domain 53. Constructs of this type, combined with trimeric versions of gp41 fragments like DSL49, may prove useful for structural characterization of the trimeric gp120-gp41 interface. The relatively modest (low μM) affinities observed here in the monomeric gp120-gp41 interface are also likely to be much stronger in the context of the trimeric Env complex due to avidity effects.

The biochemical system we describe here for mimicking the gp120-gp41 interaction will likely find wide utility in future structural and mechanistic studies of the gp120-gp41 interface. Future studies will focus on using this system to learn how conformational changes of the gp120-gp41 interface caused by CD4/coreceptor binding enable gp41 to convert from its inactive prefusogenic conformation to the postfusogenic six-helix bundle. This system will also allow more detailed studies of the contributions of specific residues in gp120 and gp41 in forming the interface, free of confounding in vivo issues such as folding, trafficking, and processing. A better understanding of this interface is likely to aid efforts to discover neutralizing Abs and novel entry inhibitors that inactivate HIV’s fusion machinery by promoting premature dissociation of the gp120-gp41 interface or, conversely, stabilizing this interface to prevent gp120 dissociation.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

gp41 sequences were obtained from pEBB-JRFL. All gp41-derived sequences contain a C-terminal His6 tag. C43 was produced from N-C43, constructed as previously described (10). Briefly, N-C43 was constructed by linking C43 with its corresponding N-peptide sequences (N38, residues 540-577), via a GGRGGS linker to form a stable six-helix bundle (trimer of N-linker-C). N-C43 was digested by trypsin, followed by reverse-phase (Vydac, C18) HPLC (RP-HPLC) purification. DSL49, DSL20, C49, DSL49ss, DSL20ss, Δ13-DSL20, L20, C20, and DSL were expressed as C-terminal fusions to maltose binding protein (MBP) linked by the TEV protease recognition sequence, ENLYFQG. All constructs were cloned into pET-17b (Novagen). Proteins were overexpressed in BL21-Gold(DE3) or BL21-Gold(DE3)-pLysS (Stratagene) and purified by Ni++ affinity column (His-Select HC nickel affinity gel, Sigma). Purified MBP-fused proteins were digested by TEV protease (kindly provided by C. Hill, U. of Utah) in 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT overnight at 4°C. RP-HPLC was performed using a C18 column (Vydac) for further purification of gp41 fragments.

The DSL region has an intramolecular disulfide bond. Although the two Cys residues in the DSL region are close enough to potentially form intermolecular disulfide bonds in the gp41 trimer (8,31,32), we exclusively produced the intramolecular disulfide bond. This configuration is currently thought to exist in the native gp41 structure because it is immunologically active (33), and intermolecular disulfide bonds have been shown to disrupt Env proteolytic processing (34).

For DSL-containing fragments, disulfide bond formation was carried out in 50 mM Tris, pH 8, 2% DMSO, and 3-6 M guanidine hydrochloride. DSL containing fragments with an intramolecular disulfide bond were separated and purified by RP-HPLC (Supplementary figure). All gp41 fragments were lyophilized after HPLC purification and reconstituted in 0.1% TFA to obtain high concentration stock solutions. 5-helix was expressed, purified and prepared as described previously (10). All purified gp41 fragments were confirmed by SDS-PAGE and MS (MALDI-TOF or ESI at the U. of Utah Mass Spectrometry Core Facility) and were soluble at 2 μM in PBS.

V1jns expression plasmids containing JRFL codon-optimized gp120, ΔV3-gp120, and ΔV1/V2/V3-gp120 were a gift from X. Liang, Merck Research Labs. For ΔC1 and ΔC5, nucleotides corresponding to residues K33-Q82 were replaced with a BamH1 restriction site, encoding Gly-Ser, and a stop codon was added prior to P493 using the XbaI site in V1jns-JRFL-gp120 plasmid, respectively. In each deletion construct, the following regions were removed from JRFL gp120: ΔC1, K33 to Q82; ΔC5, P493 to C-terminus; ΔV1/V2, T128 to I194; ΔV3, T303 to I323 (Fig. 1C). All gp120 proteins were expressed in 293T-EBNA cells (Invitrogen) by transient transfection with FuGENE 6 (Roche). Starting 24 h post-transfection, supernatant was harvested each day for 3 days, clarified through a 0.22 μm filter, and concentrated with a 10 kDa cutoff Centricon (Millipore), if necessary. Wild type JRFL-gp120 was purified using a Lentil Lectin column (Amersham Biosciences) as described in manufacturer’s instructions and concentrated with a 10 kDa cutoff Centricon. Approximate gp120 concentration was measured by Western blot using commercial YU2-gp120 (ImmunoDiagnostics, Inc.) as a standard.

MBP and MBP-C1/C5 were constructed into pET-17b. C1 (31-94) and C5 (482-511) sequences derived from pEBB-JRFL were linked by SGGGSGGGS. The N-terminus of C1 was fused to MBP linked by a TEV cleavage site (ENLYFQGS) and C9 tag (TETSQVAPA). For the MBP control protein, a TEV cleavage sequence was added at the C-terminus. MBP and MBP-C1/C5 were expressed in BL21-Gold(DE3)-pLysS and purified by amylose column (New England BioLabs).

The 2-domain sCD4 expression plasmid, pET-9a CD4-D1D2, was kindly provided by Raghavan Vardarajan (Indian Institute of Science). CD4-D1D2-H6 (sCD4-H6) was expressed in BL21-DE3-pLysS and purified by Ni++ affinity column in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride. Purified sCD4-H6 was refolded by dialysis into PBS, pH 7.4.

Binding assay

gp120 (∼100 nM) and gp41 fragments (2 μM) were mixed for 2 h at 23°C in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% Fetal Calf Serum (Gibco). 400 nM sCD4 (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Program, contributed by Pharmacia) was added to the mixture, as indicated. As a positive control, 2 μM sCD4-H6 was used to measure the total amount of active gp120 in this assay. Next, 15 μl Talon Dynabeads (Dynal, binding to the C-terminal His6 tag present on all gp41 fragments and sCD4-H6) were added and incubated for 15 min at RT. Beads were then magnetically precipitated and washed twice with 500 μl PBS containing 0.01% Tween-20 and 10 mM imidazole. Bound proteins were eluted with 400 mM imidazole and analyzed by non-reducing SDS-PAGE (NuPAGE, Invitrogen) and Western blot with sheep anti-gp120 serum (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Program, contributed by Michael Phelan). JRFL-gp120 showed broad smearing in western blot analysis due to variable glycosylation. To sharpen these bands for quantification, eluted gp120 was deglycosylated by PNGaseF (NEB) following manufacturer’s instructions. Western blot analysis of expressed gp120 showed the expected monomer, but also dimers and trimers linked by intermolecular disulfide bonds that can be broken under mild reducing conditions, as previously reported 56. These oligomers are easily detected by Western blot analysis, but are barely detectable using direct protein staining. Since these dimers and trimers do not have completely native conformations (due to shuffled disulfide bonds), only the binding of monomeric gp120 was measured in this study using non-reducing SDS-PAGE. Bands were quantified using the Odyssey Western Blot Imaging System (LI-COR) with the included software. 10 μM MBP and MBP-C1/C5 were mixed with 2 μM DSL49 or Ubiquitin-H6 (Ub-H6) in PBS containing 10% FBS. Ub-H6 used as a negative control was prepared as previously described 57. To see the effect of the formation of the trimer-of-hairpins, 3 μM 5-helix was preincubated with DSL49 as indicated (Fig. 3A). The mixture was precipitated and washed as described above. Bound proteins were analyzed by non-reducing SDS-PAGE and coomassie blue staining.

Crosslinking

gp120 purified by Lectin Lentil column (GE Healthcare) was dialyzed into PBS (Gibco). gp120 (0.9 μg) was mixed with 0.25 μg sCD4, 0.28 μg DSL49, and/or 0.5 μg 5-helix in 10 μl PBS at RT. 10 mM glutaraldehyde (Fisher) was added and incubated for 5 min at RT, followed by quenching with Tris. Crosslinked mixtures were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Krypton infrared protein staining (Pierce).

Modification of cysteines in DSL49

DSL49 was completely reduced by boiling in 100 mM DTT, PBS, pH 7.4. Reduced cysteines were blocked by reaction with 50 mM NEM (Sigma) or 50mM iodoacetate (Sigma) in PBS or TBS, pH 7.4, respectively, for 1 h at RT. Unreacted NEM or iodoacetate was removed by ultrafiltration (Centricon, Millipore).

Cell binding assay

Hos-pBABE-puro cells were obtained from the NIH AIDS reagent Program (N. Landau) and propagated in DMEM supplemented with 10% Fetal Calf Serum and 1 μg/ml puromycin. Cells were dissociated using cell dissociation buffer (Invitrogen) and were washed and resuspended with PBS containing 0.1% sodium azide and incubated for 30 minutes at RT to prevent endocytosis 58. 2.5×105 cells were incubated with 2 μM gp41 fragments for 1 hr at RT and washed three times with 500 μl PBS containing 0.01% Tween. Cells were resuspended with SDS loading buffer and completely lysed by sonication and boiling. Bound gp41 fragments were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot using anti-His tag polyclonal antibody (Abcam).

Immunostaining

2 μM DSL49 or DSL49ss was incubated with 5×106 HOS-pBABE-puro cells in the presence of 0.1% sodium azide to block endocytosis and 5% FBS as blocking solution for 2 hours at RT. Cells were washed three times with 500 μl PBS containing 0.01% Tween (PBS-T). Cells were fixed by 4% PFA (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in PBS for 15 min at RT, followed by three washes with 500 μl PBS. After blocking with 5% goat serum (Invitrogen) in PBS for 1 h at RT, cells were incubated with 250 μl rabbit anti-His6 antibody (AbCam) at 1:200 dilution in blocking solution containing 0.01% Tween overnight at 4° C. Unbound antibody was removed by three washes with PBS-T (10 minutes each at RT). Cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit antibody (Molecular Probes) at 1:500 dilution in blocking solution containing 0.01% Tween for 1 h at RT, followed by three washes with PBS-T (20 min each at RT). Cells were placed on the slide with VectaShield (Vector Labs) and photographed at 40X and 100X magnification.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health Grant P01GM066521.

Special thanks to Debra Eckert, Brett Welch, and Michael Root for helpful discussions and critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wyatt R, Sodroski J. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science. 1998;280:1884–8. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eckert DM, Kim PS. Mechanisms of viral membrane fusion and its inhibition. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:777–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sattentau QJ, Moore JP. Conformational changes induced in the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein by soluble CD4 binding. J Exp Med. 1991;174:407–15. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu L, Gerard NP, Wyatt R, Choe H, Parolin C, Ruffing N, Borsetti A, Cardoso AA, Desjardin E, Newman W, Gerard C, Sodroski J. CD4-induced interaction of primary HIV-1 gp120 glycoproteins with the chemokine receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384:179–83. doi: 10.1038/384179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen B, Vogan EM, Gong H, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, Harrison SC. Structure of an unliganded simian immunodeficiency virus gp120 core. Nature. 2005;433:834–41. doi: 10.1038/nature03327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan K, Liu J, Wang J, Shen S, Lu M. Atomic structure of a thermostable subdomain of HIV-1 gp41. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12303–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan DC, Fass D, Berger JM, Kim PS. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell. 1997;89:263–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caffrey M, Cai M, Kaufman J, Stahl SJ, Wingfield PT, Covell DG, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. Three-dimensional solution structure of the 44 kDa ectodomain of SIV gp41. Embo J. 1998;17:4572–84. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison SC, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature. 1997;387:426–30. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Root MJ, Kay MS, Kim PS. Protein design of an HIV-1 entry inhibitor. Science. 2001;291:884–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1057453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckert DM, Kim PS. Design of potent inhibitors of HIV-1 entry from the gp41 N-peptide region. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11187–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201392898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckert DM, Malashkevich VN, Hong LH, Carr PA, Kim PS. Inhibiting HIV-1 entry: discovery of D-peptide inhibitors that target the gp41 coiled-coil pocket. Cell. 1999;99:103–15. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wild C, Greenwell T, Matthews T. A synthetic peptide from HIV-1 gp41 is a potent inhibitor of virus-mediated cell-cell fusion. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1993;9:1051–3. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bewley CA, Louis JM, Ghirlando R, Clore GM. Design of a novel peptide inhibitor of HIV fusion that disrupts the internal trimeric coiled-coil of gp41. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14238–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201453200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan DC, Kim PS. HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell. 1998;93:681–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starcich BR, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, McNeely PD, Modrow S, Wolf H, Parks ES, Parks WP, Josephs SF, Gallo RC, et al. Identification and characterization of conserved and variable regions in the envelope gene of HTLV-III/LAV, the retrovirus of AIDS. Cell. 1986;45:637–48. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Binley JM, Sanders RW, Clas B, Schuelke N, Master A, Guo Y, Kajumo F, Anselma DJ, Maddon PJ, Olson WC, Moore JP. A recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein complex stabilized by an intermolecular disulfide bond between the gp120 and gp41 subunits is an antigenic mimic of the trimeric virion-associated structure. J Virol. 2000;74:627–43. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.2.627-643.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helseth E, Olshevsky U, Furman C, Sodroski J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein regions important for association with the gp41 transmembrane glycoprotein. J Virol. 1991;65:2119–23. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.2119-2123.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.York J, Nunberg JH. Role of hydrophobic residues in the central ectodomain of gp41 in maintaining the association between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein subunits gp120 and gp41. J Virol. 2004;78:4921–6. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4921-4926.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs A, Sen J, Rong L, Caffrey M. Alanine scanning mutants of the HIV gp41 loop. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27284–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414411200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poumbourios P, Maerz AL, Drummer HE. Functional evolution of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein 120 association site of glycoprotein 41. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42149–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305223200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang S, York J, Shu W, Stoller MO, Nunberg JH, Lu M. Interhelical interactions in the gp41 core: implications for activation of HIV-1 membrane fusion. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7283–92. doi: 10.1021/bi025648y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao J, Bergeron L, Helseth E, Thali M, Repke H, Sodroski J. Effects of amino acid changes in the extracellular domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1993;67:2747–55. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2747-2755.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore PL, Crooks ET, Porter L, Zhu P, Cayanan CS, Grise H, Corcoran P, Zwick MB, Franti M, Morris L, Roux KH, Burton DR, Binley JM. Nature of nonfunctional envelope proteins on the surface of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2006;80:2515–28. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2515-2528.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang CC, Tang M, Zhang MY, Majeed S, Montabana E, Stanfield RL, Dimitrov DS, Korber B, Sodroski J, Wilson IA, Wyatt R, Kwong PD. Structure of a V3-containing HIV-1 gp120 core. Science. 2005;310:1025–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1118398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet RW, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–59. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guilhaudis L, Jacobs A, Caffrey M. Solution structure of the HIV gp120 C5 domain. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:4860–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore JP, McKeating JA, Weiss RA, Sattentau QJ. Dissociation of gp120 from HIV-1 virions induced by soluble CD4. Science. 1990;250:1139–42. doi: 10.1126/science.2251501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Si Z, Madani N, Cox JM, Chruma JJ, Klein JC, Schon A, Phan N, Wang L, Biorn AC, Cocklin S, Chaiken I, Freire E, Smith AB, 3rd, Sodroski JG. Small-molecule inhibitors of HIV-1 entry block receptor-induced conformational changes in the viral envelope glycoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5036–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307953101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chertova E, Bess Jr JW, Jr., Crise BJ, Sowder IR, Schaden TM, Hilburn JM, Hoxie JA, Benveniste RE, Lifson JD, Henderson LE, Arthur LO. Envelope glycoprotein incorporation, not shedding of surface envelope glycoprotein (gp120/SU), Is the primary determinant of SU content of purified human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2002;76:5315–25. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5315-5325.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore JP, McKeating JA, Huang YX, Ashkenazi A, Ho DD. Virions of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates resistant to soluble CD4 (sCD4) neutralization differ in sCD4 binding and glycoprotein gp120 retention from sCD4-sensitive isolates. J Virol. 1992;66:235–43. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.235-243.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alam SM, Paleos CA, Liao HX, Scearce R, Robinson J, Haynes BF. An inducible HIV type 1 gp41 HR-2 peptide-binding site on HIV type 1 envelope gp120. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20:836–45. doi: 10.1089/0889222041725181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan W, Craig S, Si Z, Farzan M, Sodroski J. CD4-induced T-20 binding to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 blocks interaction with the CXCR4 coreceptor. J Virol. 2004;78:5448–57. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5448-5457.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maerz AL, Drummer HE, Wilson KA, Poumbourios P. Functional analysis of the disulfide-bonded loop/chain reversal region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 reveals a critical role in gp120-gp41 association. J Virol. 2001;75:6635–44. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6635-6644.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pascual R, Moreno MR, Villalain J. A peptide pertaining to the loop segment of human immunodeficiency virus gp41 binds and interacts with model biomembranes: implications for the fusion mechanism. J Virol. 2005;79:5142–52. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.5142-5152.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moreno MR, Pascual R, Villalain J. Identification of membrane-active regions of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp41 using a 15-mer gp41-peptide scan. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1661:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Binley JM, Cayanan CS, Wiley C, Schulke N, Olson WC, Burton DR. Redox-triggered infection by disulfide-shackled human immunodeficiency virus type 1 pseudovirions. J Virol. 2003;77:5678–84. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.10.5678-5684.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abrahamyan LG, Markosyan RM, Moore JP, Cohen FS, Melikyan GB. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env with an intersubunit disulfide bond engages coreceptors but requires bond reduction after engagement to induce fusion. J Virol. 2003;77:5829–36. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.10.5829-5836.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steger HK, Root MJ. Kinetic dependence to HIV-1 entry inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2006 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601457200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salzwedel K, Smith ED, Dey B, Berger EA. Sequential CD4-coreceptor interactions in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env function: soluble CD4 activates Env for coreceptor-dependent fusion and reveals blocking activities of antibodies against cryptic conserved epitopes on gp120. J Virol. 2000;74:326–33. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.326-333.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kolchinsky P, Mirzabekov T, Farzan M, Kiprilov E, Cayabyab M, Mooney LJ, Choe H, Sodroski J. Adaptation of a CCR5-using, primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate for CD4-independent replication. J Virol. 1999;73:8120–6. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8120-8126.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Myszka DG, Sweet RW, Hensley P, Brigham-Burke M, Kwong PD, Hendrickson WA, Wyatt R, Sodroski J, Doyle ML. Energetics of the HIV gp120-CD4 binding reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9026–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rizzuto CD, Wyatt R, Hernandez-Ramos N, Sun Y, Kwong PD, Hendrickson WA, Sodroski J. A conserved HIV gp120 glycoprotein structure involved in chemokine receptor binding. Science. 1998;280:1949–53. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wyatt R, Moore J, Accola M, Desjardin E, Robinson J, Sodroski J. Involvement of the V1/V2 variable loop structure in the exposure of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 epitopes induced by receptor binding. J Virol. 1995;69:5723–33. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5723-5733.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Sattentau QJ, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA. Oligomeric modeling and electrostatic analysis of the gp120 envelope glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2000;74:1961–72. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1961-1972.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sen J, Jacobs A, Jiang H, Rong L, Caffrey M. The disulfide loop of gp41 is critical to the furin recognition site of HIV gp160. Protein Sci. 2007;16:1236–41. doi: 10.1110/ps.072771407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oldstone MB, Tishon A, Lewicki H, Dyson HJ, Feher VA, Assa-Munt N, Wright PE. Mapping the anatomy of the immunodominant domain of the human immunodeficiency virus gp41 transmembrane protein: peptide conformation analysis using monoclonal antibodies and proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Virol. 1991;65:1727–34. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.1727-1734.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Owens RJ, Compans RW. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein precursor acquires aberrant intermolecular disulfide bonds that may prevent normal proteolytic processing. Virology. 1990;179:827–33. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90151-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Syu WJ, Lee WR, Du B, Yu QC, Essex M, Lee TH. Role of conserved gp41 cysteine residues in the processing of human immunodeficiency virus envelope precursor and viral infectivity. J Virol. 1991;65:6349–52. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6349-6352.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dedera D, Gu RL, Ratner L. Conserved cysteine residues in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane envelope protein are essential for precursor envelope cleavage. J Virol. 1992;66:1207–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.1207-1209.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shu W, Ji H, Lu M. Interactions between HIV-1 gp41 core and detergents and their implications for membrane fusion. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1839–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mische CC, Yuan W, Strack B, Craig S, Farzan M, Sodroski J. An alternative conformation of the gp41 heptad repeat 1 region coiled coil exists in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) envelope glycoprotein precursor. Virology. 2005;338:133–43. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pancera M, Lebowitz J, Schon A, Zhu P, Freire E, Kwong PD, Roux KH, Sodroski J, Wyatt R. Soluble mimetics of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral spikes produced by replacement of the native trimerization domain with a heterologous trimerization motif: characterization and ligand binding analysis. J Virol. 2005;79:9954–69. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9954-9969.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weissenhorn W, Wharton SA, Calder LJ, Earl PL, Moss B, Aliprandis E, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. The ectodomain of HIV-1 env subunit gp41 forms a soluble, alpha-helical, rod-like oligomer in the absence of gp120 and the N-terminal fusion peptide. Embo J. 1996;15:1507–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wingfield PT, Stahl SJ, Kaufman J, Zlotnick A, Hyde CC, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. The extracellular domain of immunodeficiency virus gp41 protein: expression in Escherichia coli, purification, and crystallization. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1653–60. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Misse D, Cerutti M, Schmidt I, Jansen A, Devauchelle G, Jansen F, Veas F. Dissociation of the CD4 and CXCR4 binding properties of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 by deletion of the first putative alpha-helical conserved structure. J Virol. 1998;72:7280–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7280-7288.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hamburger AE, Kim S, Welch BD, Kay MS. Steric accessibility of the HIV-1 gp41 N-trimer region. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12567–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaljot KT, Shaw RD, Rubin DH, Greenberg HB. Infectious rotavirus enters cells by direct cell membrane penetration, not by endocytosis. J Virol. 1988;62:1136–44. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.4.1136-1144.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.