Abstract

Distinct CD4+ T-cell epitopes within the same protein can be optimally processed and loaded into major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules in disparate endosomal compartments. The CD1 protein isoforms traffic to these same endosomal compartments as directed by unique cytoplasmic tail sequences, therefore we reasoned that antigen/CD1 chimeras containing the different CD1 cytoplasmic tail sequences could optimally target antigens to the MHC class II antigen presentation pathway. Evaluation of trafficking patterns revealed that all four human CD1-derived targeting sequences delivered antigen to the MHC class II antigen presentation pathway, to early/recycling, early/sorting and late endosomes/lysosomes. There was a preferential requirement for different CD1 targeting sequences for the optimal presentation of an MHC class II epitope in the following hierarchy: CD1b > CD1d = CD1c > > > CD1a or untargeted antigen. Therefore, the substitution of the CD1 ectodomain with heterologous proteins results in their traffic to distinct intracellular locations that intersect with MHC class II and this differential distribution leads to specific functional outcomes with respect to MHC class II antigen presentation. These findings may have implications in designing DNA vaccines, providing a greater variety of tools to generate T-cell responses against microbial pathogens or tumours.

Keywords: antigen presentation/processing, humans, major histocompatibility complex, T cells

Introduction

The generation of antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell responses is crucial to host immunity against infection and cancer. Historically, pathogen-specific CD4+ T-cell responses have been elicited through immunization with attenuated or otherwise inactivated pathogens or pathogen-derived proteins in the presence of adjuvant. Professional antigen-presenting cells (APC) internalize microbes or soluble antigens into endosomal/phagosomal compartments where the process of denaturation and proteolytic degradation is initiated and continues with the traffic of captured antigens through increasingly mature endosomal compartments culminating with lysosomes/major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II compartment (MIIC). Endosomal maturation from early to late endosomes/lysosomes/MIICs typically correlates with a significant decrease in pH as well as an increase in proteolytic degradative potential.1–3 Protein fragments (or epitopes) resulting from proteolytic degradation are bound by MHC class II proteins and are trafficked to the cell surface where they are sampled by the T-cell receptor (TCR) of CD4+ T cells leading to the activation of antigen-specific T cells.4–7

The human CD1 family of antigen presentation molecules is comprised of five isoforms (a–e), four of which (a–d) are unique in their ability to present non-peptide antigens to T cells.8–12 Each CD1 isoform displays a unique trafficking pattern to distinct subsets of endosomal compartments, directed by a tyrosine-based targeting motif located in the cytoplasmic tail of each protein.13,14 CD1a accumulates predominantly in early/recycling endosomes, CD1b and CD1d accumulate in late endosomes/lysosomes/MIIC, and CD1c is present mainly in sorting and recycling endosomes although it may also be detected in more mature endosomal compartments.14 Many of the compartments through which the CD1 proteins traffic also contain MHC class II and other accessory proteins of the MHC class II antigen presentation pathway.13–16 In this report, we evaluated CD1-derived endosomal targeting sequences for their ability to deliver antigen to the MHC class II antigen presentation pathway.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

Antibodies for immunofluorescence studies were as follows: anti-CD1a (OKT6, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), anti-CD1b and anti-CD1c (BCD1b3.117 and F10/21A318 kindly provided by S. A. Porcelli), anti-CD1d (CD1d 42.1, BD Pharmingen San Diego, CA), anti-FLAG (M2, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis MO), anti-CD63 (H5C6, BD Biosciences/Pharmingen), anti-CD71 (M-A712, BD Pharmingen), anti-CD107a/lysosome-associated membrane protein (LAMP)-1 (H4A3, BD Biosciences/Pharmingen), and anti-HLA-DR (DK22, DAKOCytomation California, Carpinteria CA). Alexa-565 goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used as secondary antibody in these studies.

T cells

T cells reactive with Mycobacterium leprae GroES were derived from the blood of a leprosy patient diagnosed and classified by one of us (T.H.R.) using the criteria of Ridley and Jopling19 at the Hansen's Disease Clinic of the Los Angeles County-University of Southern California Medical Center. The patient was undergoing a reversal reaction, clinically upgrading from lepromatous to tuberculoid at the time the blood was obtained. Blood samples (from the patient with leprosy and from healthy donors) were acquired after informed consent using protocols approved by the David Geffen School of Medicine's Institutional Review Board. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll–Paque (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden). The GroES-reactive T cells were derived from PBMCs stimulated with M. leprae GroES protein and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium enriched with sodium pyruvate, penicillin, streptomycin, and l-glutamine (all from Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) in the presence of human serum (10%). T cells were maintained with GroES peptide28−39 (1 μm) with heterologous human leucocyte antigen (HLA) -DR-matched healthy donor PBMCs followed by a total of three feedings of interleukin-2 (1 nm, Chiron Diagnostics, Norwood, MA) 3 days apart as described previously.20 PBMCs from healthy donors were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll–Paque (Amersham Biosciences) and irradiated (3000 rads) for use as APCs. HLA typing was performed at the UCLA Tissue Typing facility.

General molecular biology

Restriction endonucleases and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from Invitrogen. Unless otherwise stated, all polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifications were performed using Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). Reagents for complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis (Trizol® and Superscript II® reverse transcriptase) were purchased from Invitrogen and used following the manufacturer's directions. Oligonucleotides utilized for construct synthesis were purchased from Operon (Operon, Huntsville AL). Bacterial transformations were performed using DH5-α™ competent cells (Invitrogen). Plasmid DNA was purified using Qiagen plasmid purification systems (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) per the manufacturer's instructions.

A brief description of the design and creation of all constructs utilized in this report is given below. All constructs described below were verified by DNA sequencing. More detailed information regarding the exact nucleotide sequence of all oligonucleotides and procedures used in this manuscript will be provided upon request.

ARF6/T27N construct

Wild-type ARF6 transits between the plasma membrane and early/recycling endosomes. The mutation of threonine to asparagine at amino acid 27 of ARF6 (T27N) results in a GTP exchange mutant, causing the protein to accumulate predominantly in recycling endosomes. Thus, mutant ARF6 is a useful tool for the identification of early/recycling endosomes in immunolocalization studies.14,21 To create the mutant ARF6, wild-type ARF6 cDNA was amplified by PCR using Failsafe DNA polymerase (Epicentre, Madison WI), oligonucleotides complimentary to the 5′ start and the 3′ end of the human ARF6 gene, and HeLa cDNA as template. The 3′ oligonucleotide utilized encoded an in-frame FLAG tag sequence addition before the stop codon. The resulting product was cloned directionally into pcDNA3.1+ (Invitrogen) and used as a template for site-directed mutagenesis of threonine-27 to an asparagine codon using the Quickchange system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) utilizing a previously described 5′ oligonucleotide22 and complimentary 3′ oligonucleotide to generate pCDNA3.1 ARF6/T27N.

GFP-tCD1 constructs

The pIRES2-EGFP plasmid (BD Biosciences/Clontech, Mountain View, CA) was used as the template for the in-frame addition of DNA sequences encoding the leader peptide and transmembrane domain of CD1b followed by CD1 isoform-specific cytoplasmic tail sequences using overlapping oligonucleotides to the green fluorescence protein (GFP) cDNA. The resulting PCR products were digested with appropriate restriction endonucleases and ligated into the pSR α-NEO plasmid.13

GroES-tCD1 constructs

The GroES constructs created in this report are based on the M. leprae GroES gene, which demonstrates significant mycobacterial codon bias in its wild-type form. As a result, we utilized a strategy of overlapping oligonucleotides spanning the entire length of GroES and PCR to produce a ‘humanized’M. leprae GroES cDNA sequence encoded by codons found in highly expressed human genes (http://www.infobiogen.fr/doc/GCGdoc/Data_Files/codon_freq_tables.html and ref. 23). The resulting PCR product including a stop codon (predicted to encode a protein with identical amino acid sequence to M. leprae GroES) was cloned into the pIRES-EGFP2 vector (Clontech). This construct, pIRES-GroES, was subsequently used as a template for the in-frame addition of the 5′ CD1b leader sequence and the 3′ CD1b transmembrane domain and isotype specific cytoplasmic tail sequences utilizing overlapping oligonucleotides as described above for the GFP-tCD1 constructs and PCR. The resulting PCR products were also cloned into pIRES-EGFP vector generating the panel of pIRES-GroES/tCD1 constructs.

HLA-DRB1*1504 and HLA-DRB5*0101 constructs

The cDNAs encoding HLA-DRB1*1504 and DRB5*0101 were generated by PCR using Failsafe DNA polymerase (Epicentre) and THP-1 total cDNA. PCR products were directionally ligated into pcDNA3.1+ (Invitrogen).

DNA transfection

The cervical carcinoma HeLa cell line (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen). HeLa cells were transfected using the indicated amounts of purified plasmid DNA (Qiagen) and Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent following the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). For experiments requiring HLA-DR expression, cells were incubated in the presence of 300 U/ml of recombinant interferon-γ (IFN-γ, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis IN) following transfection for 72 hr to up-regulate the MHC class II antigen presentation machinery before harvest and analysis. To reduce the level of variability in HLA-DRB5 expression in subsequent T-cell assays, an HLA-DRB5 plasmid cocktail was prepared, thoroughly mixed, and divided into aliquots before the addition of the individual GroES-based plasmids.

The GroES-IRES-GFP constructs used in this study were created to provide a sensitive and easily quantifiable means for the monitoring of transgene expression levels following transfection. This is because of the simultaneous, internal ribsome entry site (IRES)-mediated expression of GFP encoded within bi-cistronic mRNA, which also encode the various GroES variants. Unlike the GroES-tCD1 proteins, which are predicted to possess varying half-lives because of isoform-specific traffic to different endosomal compartments with variable protein-degrading activities, the GFP produced by these constructs resides predominantly in the cytoplasm in all transfections. As a result, these constructs are well-suited for rapid and reliable transgene expression analysis using extremely small amounts of plasmid DNA (as little as 3·33 ng/transfection) with regards to both GFP mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) and transfection efficiency. Unless otherwise stated, GFP expression in the transfections utilizing the pIRES-GroES/tCD1 constructs used for subsequent T-cell assays was evaluated by flow cytometry using the BD LSR flow cytometer and was analysed using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, Rockville MD). Using GFP expression as a measure of transfection efficiency, we found that all groups expressed statistically indistinguishable amounts of GroES within an experiment (P-values 0·1–0·9), with the exception of the GroES plasmid lacking CD1 targeting sequences (P < 0·05). The number of transfected cells, although consistent within experiments, varied slightly between each experiment.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Transfectants were allowed to adhere to poly l-lysine-coated slides (Nunc, Rochester, NY) before being fixed with paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with permeabilization/block buffer [5% human serum, 5% goat serum, 1% dry milk, 1% Triton X-100, 0·01% saponin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7·2], washed extensively, and incubated with primary antibody (∼ 250 ng/ml or per the manufacturer's recommendations) in PBS/10% FBS/1% Triton X-100/0·01% saponin. Next, samples were washed with PBS and incubated with Alexa-565 labeled goat antimouse secondary antibodies, washed, fixed, and analysed as previously described.24

T-cell assays and cytokine ELISA

Unless otherwise indicated, T-cell assays were performed using HeLa cell transfectants. Briefly, HeLa cells were transfected with HLA-DR-encoding plasmid and indicated amounts of GroES-encoding plasmids and incubated with recombinant IFN-γ as described above before harvest. Transfectants were harvested, washed extensively, counted and incubated (5 × 104) with CD4+ GroES-reactive T cells (2 × 104) in 200 μl RPMI-1640/8% FBS/2% human serum at 37°. After 18 hr, supernatant was removed and analysed for the presence of IFN-γ by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; BD Biosciences/Pharmingen).

Endosomal acidification inhibitor assays were performed by treating HLA-DR-matched PBMCs with the stated concentrations of either concanamycin A or chloroquine (both purchased from Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 hr before the addition of antigen. The final concentration of each antigen was 0·1 μm for synthetic GroES28−39 peptide and 0·01 μg/ml for rGroES protein. Cells were incubated for an additional 2 hr, collected, washed extensively, and incubated with T cells as described above. GroES28−39 peptide was synthesized by the Peptide Peptidomics Resource Laboratory at the UCLA School of Medicine and the purification of recombinant M. leprae GroES is described elsewhere.25

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of GFP expression between groups of cells transfected with GroES-tCD1-GFP were made using Student's t-test; differences >0·05 were considered significant.

Results

CD1-derived endosomal targeting motifs direct fusion proteins to wild-type CD1-containing vesicles

The human CD1 proteins localize to distinct endosomal compartments because there are isoform-specific endosomal targeting motifs in their cytoplasmic tails.13,14 Replacement of the cytoplasmic tail sequence of MHC class I with that of CD1b resulted in a change in the steady-state distribution of MHC class I to more closely match that of CD1b.26 We reasoned that CD1-derived endosomal targeting sequences could target any protein, including immunologically relevant antigens, to the intracellular structures typically occupied by the corresponding wild-type CD1 isoforms. Because MHC class II molecules reside in many of the same endosomes through which the CD1 proteins traffic, we further reasoned that targeting of antigen to endosomes visited by distinct CD1 isoforms may facilitate their presentation by MHC class II.

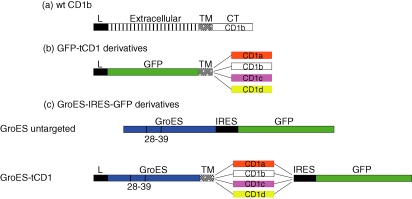

A panel of constructs encoding GFP fused to different CD1 cytoplasmic tail sequences (herein referred to as GFP-tCD1) were established to determine whether CD1-derived targeting motifs can direct the traffic of protein fusion partners into the endosomal system. The wild-type cDNA of human CD1b, shown in Fig. 1(a), is organized in a similar manner to that of MHC class I, encoding a leader peptide, an extracellular domain that functions in antigen binding and presentation, a transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic tail responsible for directing intracellular traffic.27 The GFP-tCD1 constructs assayed encode the leader peptide of CD1b followed by GFP, the transmembrane domain of human CD1b, and each of the four cytoplasmic tail sequences of CD1a–d (Fig. 1b). Based on this domain arrangement, the GFP portion of the chimeric protein would be predicted to reside within the lumen of endocytic vesicles following internalization from the cell surface.

Figure 1.

Diagram of DNA constructs created for this study. (a) Domain organization of the human CD1b cDNA including the leader peptide (black bar), the α1, α2 and α3 domains that constitute the extracellular/ectodomain (striped bar), the transmembrane (spotted bar), and the cytoplasmic tail domain (open bar). (b) Domain organization of the GFP-tCD1a–d constructs utilized in accompanying intracellular trafficking studies. These constructs differ from the parent CD1b sequence in that the CD1b ectodomain has been substituted with GFP sequence (green bar) and fused to all four CD1a–d cytoplasmic tail sequences (orange, open, pink and yellow bars). (c) Domain organization of the GroES-tCD1a–d constructs utilized in antigen presentation assays which are identical to the GFP-tCD1 constructs with the exception of the substitution of the CD1b ectodomain with GroES sequence (blue bar). (c) Domain organization of the GroES-tCD1a–d-GFP constructs utilized to quantify antigen expression and for use in T-cell assays. Constructs are organized in a manner similar to the GFP-tCD1 constructs described with two notable exceptions: (1) the M. leprae GroES cDNA replaces GFP sequence and (2) all constructs contain a vector-derived IRES-GFP sequence to facilitate quantification of gene expression.

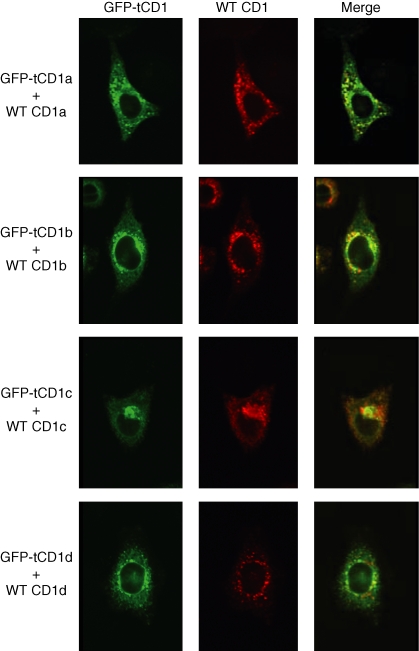

To determine whether antigen-tCD1 chimeric proteins could traffic to the various intracellular compartments visited by the wild-type CD1 proteins, HeLa cells were cotransfected with constructs encoding GFP-tCD1 chimera and their corresponding wild-type CD1. The intracellular distribution of each protein pair was assessed by immunofluorescence microscopy. All four GFP-tCD1 proteins displayed significant levels of colocalization with their respective wild-type CD1 counterparts (Fig. 2) although subtle variations in localization were observed. Although these discrepancies are probably the result of differences in sensitivity between the direct detection of GFP and the antibody-mediated detection of the wild-type CD1 proteins, it is also possible that the substitution of the extracellular domain of CD1b with GFP results in occasional but detectable levels of accumulation of the chimeric GFP-tCD1 proteins in atypical intracellular sites.

Figure 2.

Comparison of GFP-tCD1 fusion protein localization with wild-type CD1 counterpart. HeLa cells were cotransfected with the following pairs of plasmids: wild-type CD1a and GFP-tCD1a, wild-type CD1b and GFP-tCD1b, wild-type CD1c and GFP-tCD1c, and wild-type CD1d and GFP-tCD1d. The intracellular distribution of GFP (depicted in green) and the wild-type CD1 proteins (depicted in red) detected using isoform-specific antibodies and Alexa 565-labelled goat anti-mouse secondary antibody was analysed by confocal microscopy. The corresponding green and red confocal immunofluorescence images were then merged to detect compartments containing both proteins (in yellow); see right-hand column.

GFP-tCD1 fusion proteins demonstrate isoform-specific intracellular localization patterns and MHC class II colocalizaion

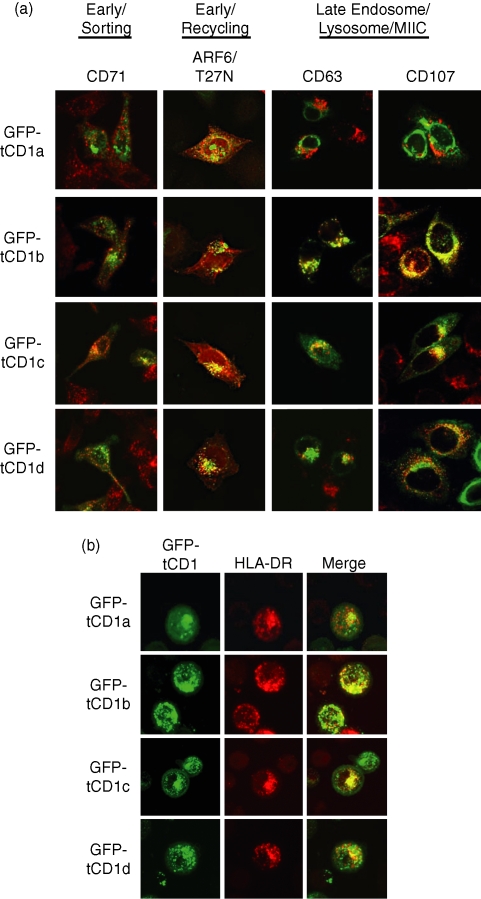

To better define the intracellular compartments through which GFP-tCD1 fusion proteins traffic, the intracellular distribution of each GFP-tCD1 fusion protein was evaluated in comparison to known endosomal markers for early/recycling endosomes (ARF-6 T27N22,28), early/sorting endosomes (CD71), and late endosomes/lysosomes (CD63/CD107a). Of the four endosomal markers used in this analysis, GFP-tCD1a colocalized to the greatest extent with the early/recycling endosome marker ARF-6 T27N, with little to no detectable colocalization with markers for more mature compartments (Fig. 3a). GFP-tCD1b colocalized most extensively with CD63 and CD107a, similar to published reports indicating that wild-type CD1b traffics to late endosomes/lysosomes/MIIC.13 The trafficking patterns of GFP-tCD1c and GFP-tCD1d were similar, in that both proteins were detected broadly in ARF-6/T27N+ (early/recycling), CD71+ (early/sorting) and CD63+ CD107a+ (late endosome/lysosomes) structures, although GFP-tCD1c demonstrated a greater ability to traffic to both ARF-6/T27N+ and CD71+ vesicles than any of the other GFP-tCD1 chimeras. Based on these results and those in Fig. 2, we concluded that the fusion of CD1 cytoplasmic tail sequences to a protein of interest results in its localization to distinct intracellular compartments in a tCD1 isoform-specific manner.

Figure 3.

(a) Comparison of GFP-tCD1 fusion protein localization to endosomal markers. HeLa cells were transfected with GFP-tCD1a–d constructs (in green) and the intracellular distribution of GFP was compared to known endosomal markers (in red) for early/recycling (ARF6-T27N), early/sorting (CD71), and late endosomes/lysosomes/MIIC (CD63 and CD107a). Confocal immunofluorescence images in this figure result from the superimposition of the GFP and endosomal marker images for each transfection to detect colocalization (in yellow). (b) Intersection of GFP-tCD1 proteins and MHC class II+ vesicles. HeLa cells were transfected with GFP-tCD1a–d constructs and MHC class II expression induced by IFN-γ. The intracellular distribution of GFP is presented in green and that of HLA-DR in red. Images acquired for each GFP protein and HLA-DR were superimposed to determine the degree of colocalization between GFP-tCD1 and HLA-DR (yellow).

The processing and loading of MHC class II antigens occurs mainly in endocytic vesicles widely believed to be late endosomes/lysosomes/MIICs.29,30 More recent evidence indicates that less mature endosomes serve as an alternative site for antigen processing for the MHC class II pathway.5,6,31,32 Since CD1 proteins localize to all known endosomal vesicles, we hypothesized that the trafficking routes of GFP-tCD1 proteins and MHC class II would intersect. To examine the colocalization of MHC class II and CD1 tail fusion proteins, HeLa cells were transfected with the panel of GFP-tCD1 expression plasmids described above and treated with recombinant IFN-γ to up-regulate MHC class II expression as described previously.33,34 Immunofluorescence microscopy analysis revealed differential degrees of colocalization for MHC class II and the GFP-tCD1 proteins. Of the four constructs tested, GFP-tCD1b demonstrated the greatest degree of colocalization with MHC class II, as would be anticipated from earlier studies.13,14,26 The remaining constructs were expressed in MHC class II-containing vesicles to varying degrees in the following order: GFP-tCD1c > GFP-tCD1d > GFP-tCD1a (Fig. 3b). These results indicate that the CD1-derived targeting sequences are sufficient to target proteins for delivery to MHC class II-positive vesicles.

Targeting M. leprae GroES to the endosomal/lysosomal system enhances T-cell responses

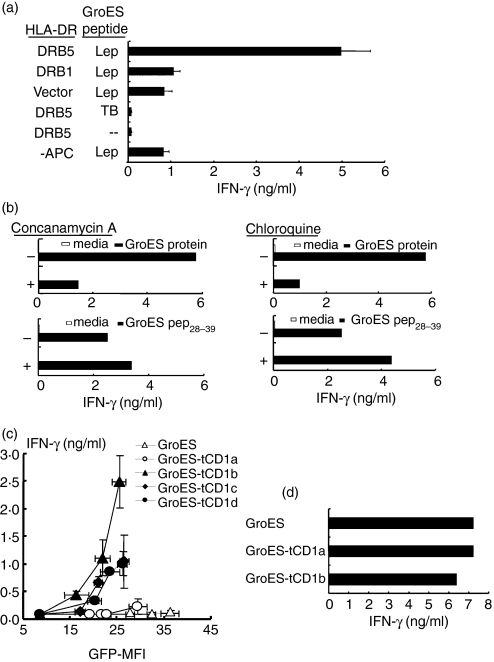

Our data provide evidence for localization of a model protein to MHC class II-positive intracellular compartments utilizing the CD1 endosomal targeting motifs. To determine whether antigens fused to CD1-based targeting sequences are capable of entering the MHC class II presentation pathway, we used the M. leprae GroES protein as a model antigen to stimulate the patient-derived TCR-αβ+ CD4+ T-cell line 914B GroES. The 914B GroES T-cell line recognizes the GroES28−39 epitope in an HLA-DRB05*0101-restricted manner (Fig. 4a) as determined by transfecting HeLa cells with an expression construct encoding HLA-DRB05*0101. In contrast, 914B GroES did not respond to similarly treated HeLa cells pulsed with M. tuberculosis-derived GroES28−39 peptide, which differs from its M. leprae orthologue in two amino acids and only weakly responded to the M. leprae GroES28−39 peptide when presented by HLA-DRB1 or plasmid lacking HLA-DR (Fig. 4a). The weak response of the T cells to GroES in the context of HeLa cells expressing HLA-DRB1 or endogenous HLA-DR was the result of presentation of antigen on the MHC of the T-cell clone because T cells alone (i.e. no APCs) with GroES peptide showed the same level of response (Fig. 4a). T-cell recognition of the M. leprae GroES28−39 epitope was dependent on endosomal acidification as determined by using full-length recombinant GroES and the endosomal acidification inhibitors chloroquine and concanamycin A (Fig. 4b). Recognition of the synthetic GroES28−39 peptide was not affected in these assays, indicating that the observed inhibition is not the result of non-specific inhibition of MHC class II antigen presentation.

Figure 4.

GroES-tCD1 fusion proteins activate CD4+ T cells. (a) Antigen-specificity and HLA restriction of the human GroES-reactive CD4+ T-cell line, 914B GroES. HeLa cells were transfected with constructs encoding HLA-DRB5*0101, HLA-DRB1*1504, or empty vector, as described, and used as antigen-presenting cells to stimulate GroES-reactive T cells in the presence of various antigens. IFN-γ ELISA was performed to determine the level of T-cell activation. Results are representative of two experiments. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). (b) Presentation of the GroES28−39 epitope to GroES-reactive T cells requires endosomal acidification. HLA-DR-matched PBMCs incubated with concanamycin A (left panels) or chloroquine (right panels) before the addition of rGroES protein (0·01 μg/ml, upper panels) or synthetic GroES28−39 peptide (0·1 μm, lower panels) were used as antigen-presenting cells to stimulate GroES-reactive T cells. Results in 4B are representative of two experiments. (c) HLA-DRB5*0101-expressing HeLa cells present GroES-tCD1 to T cells. HeLa cells were cotransfected with HLA-DRB5*0101-encoding plasmid and DNA and one of a panel of CD1-targeted GroES (or untargeted GroES) expression constructs. All transfectants were treated with rIFN-γ as described before use as antigen-presenting cells in culture with GroES-reactive T cells. GroES DNA concentrations utilized were 10, 33 and 100 ng with the exception of the GroES-tCD1a construct, which was also tested at 333 ng per transfection. Results shown are representative of two independent experiments, both performed with three independent preparations of plasmid DNA per construct tested. Mean fluorescence intensity values of GFP expression as a measure of antigen quantity was determined by flow cytometry and performed in triplicate tranasfections (mean ± SEM). The y-axis values shown represent IFN-γ production (mean ± SEM) from the T cells (determined in triplicate). (d) HLA transfected HeLa cells express functionally equivalent levels of HLA DRB5*0101. HeLa cells transfected with HLA DRB5*0101 and GroES plasmids were pulsed with GroES peptide (0·1 μm), then added to GroES-reactive T cells. IFN-γ was detected by ELISA. Values shown are the means of triplicates.

To examine the relative ability of the CD1 cytoplasmic tails to target GroES into the MHC class II presentation pathway, HLA DRB5-expressing HeLa cells were cotransfected with constructs encoding untargeted GroES or GroES-tCD1 chimeras followed by an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) and GFP cDNA sequence (Fig. 1c).

Consistent with the results obtained from the immunofluorescence and endosomal inhibitor studies, we found that transfectants expressing wild-type GroES or GroES-tCD1a were suboptimal compared to cells expressing GroES fused to the intracellular targeting motifs of CD1b–d (Fig. 4c). Of equal importance, GFP expression correlated directly with the quantity of input plasmid DNA in the experiments described. All groups of transfectants expressed statistically indistinguishable amounts of GroES within an experiment (P-values from 0·15 to 1·0), with the exception of the GroES plasmid lacking CD1 targeting sequences (P < 0·05), excluding the possibility that decreased expression of GroES led to the reduced antigen presentation in GroES-tCD1a and GroES untargeted transfected cells (below).

To confirm equivalent levels of HLA DRB5*0101 expression on the HeLa transfectants, exogenous GroES peptide was added. GroES-reactive T cells responded equivalently to HLA DRB5-expressing HeLa cells pulsed with GroES peptide, regardless of the GroES-tCD1 plasmid added (Fig. 4d), indicating that HeLa cells expressed functionally equivalent levels of HLA DRB5*0101. Therefore reduced antigen presentation in the GroES-tCD1a and GroES untargeted cells was not the result of reduced HLA expression. As stated above, the wild-type CD1b, CD1c and CD1d proteins all traffic to more mature endosomal compartments than CD1a, which is consistent with antigen presentation of GroES, which required endosomal acidification (Fig. 4b). Altogether, our results demonstrate that CD1-derived endosomal targeting sequences can direct the traffic of antigen into distinct intracellular destinations including the structures involved in MHC class II antigen presentation.

Discussion

CD4+ T cells play an integral role in immune homeostasis as both effector and regulatory cells in the host response to infection, cancer and autoimmunity. Traditionally, therapeutic strategies aimed at mobilizing CD4+ T cells have followed a regimen of immunization with soluble antigen preparations, which are internalized by professional APC, degraded into peptide fragments and presented on the APC surface by MHC class II proteins for sampling by CD4+ T cells. In this report, we demonstrate that the addition of CD1-derived endosomal targeting motifs to client proteins results in CD1 isoform-specific intracellular trafficking patterns in a manner similar to that observed for the corresponding wild-type CD1 isoform. More importantly, we demonstrate that the endosomal localization signals for CD1b, -c and -d promote more efficient presentation of a MHC class II-restricted, CD4+ T-cell antigen, M. leprae GroES than untargeted or CD1a-targeted antigen. Our data suggest that antigens can be directed to discrete endosomal locations by the CD1 endosomal targeting motifs, thereby providing a novel genetic strategy for targeting antigens to distinct MHC class II processing compartments for vaccine design.

Throughout the endocytic pathway, exogenous antigens encounter a variety of intracellular compartments with differing pH, resident protease pools and reductive potential, experiencing extensive denaturation and proteolytic degradation to generate the antigenic peptide epitopes loaded into MHC class II proteins. The GFP-tCD1 trafficking data demonstrate that the CD1b, CD1c and CD1d cytoplasmic tails cumulatively direct proteins to early/sorting endosomes and late endosomes/lysosomes/MIIC; in contrast, CD1a-targeted GFP demonstrates a steady-state distribution pattern that intersects the early/recycling endosomal marker ARF-6/T27N with little overlap with typical late endosomal/lysosomal markers such as LAMP-1 and CD63, CD71 or MHC class II. Thus, the trafficking studies with GFP showed that endosomal localization motifs directed the model protein to sites that were consistent with the trafficking of native CD1 proteins;13,14 this encouraged us to use CD1 localization motifs to direct a microbial protein antigen to the endosomal system.

Plasmid DNA provides an alternative to more traditional protein-based vaccines because plasmid DNA is less expensive to generate, more stable and more amenable to further modifications, including the addition of targeting sequences that alter the intracellular distribution of the antigen and the inclusion of immune-modifying genes. We found that CD1 endosomal localization motifs directed M. leprae GroES for optimal presentation in the following hierarchy: CD1b > CD1d = CD1c > > > CD1a or untargeted antigen. The trafficking studies suggested a late endosome/MIIC site for CD1b, and inhibition of antigen presentation with chloroquine and concanamycin A (Fig. 4) is consistent with antigen loading of GroES in acidified endosomes. Previous genetic antigen-targeting systems have used targeting domains derived from various proteins including LAMP-1, lysosomal integral membrane protein (LIMP)-II, HLA-DR, and Ii, among others.35,36 Fusion of the LAMP-1 endosomal targeting sequence to antigen results in its traffic to lysosomes/MIIC in vitro.37In vivo, immunization of animals with LAMP-1-targeted antigen expression constructs results in significantly improved antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses and survival against lethal tumour challenge compared to untargeted constructs.38

The potential benefit of targeting microbial antigens via CD1 localization motifs would be to place an antigen in discrete endosomal sites. It is increasingly apparent that the processing of many MHC class II epitopes occurs independent of the more mature intracellular compartments, such as late endosomes/lysosomes/MIIC, and is more likely to occur in early/recycling endosomes.4,36 The CD1a tail did not result in significant T-cell activation in this study, presumably because CD1a targets antigens to early, unacidified endosomes.14 Antigens requiring early endosomal localization for loading4,36 may benefit from the CD1 endosomal localization motif, though this remains to be determined. Arruda et al.39 have recently used a varied approach to direct microbial antigens to discrete sites using alternative endosomal localization motifs. We hypothesize that the family of CD1 endosomal localization motifs would provide coverage for most if not all endosomal sites for MHC class II antigen presentation. Together, these results illustrate the need for the development and careful analysis of additional MHC class II-targeting DNA vaccination platforms. The use of CD1-derived endosomal localization motifs to target proteins to discrete endosomal vesicles, as we show here, broadens both the pools of possible antigen-loading compartments as well as available targeting motifs in genetic immunization approaches.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Matthew Schibler and the Carol Moss Spivak Cell Imaging Facility in the UCLA Brain Research Institute for the use of the confocal laser microscope, the Peptide Peptidomics Resource Laboratory at the UCLA School of Medicine for synthesis of the GroES peptide, the UCLA tissue-typing laboratory for HLA-DR typing, and Anna Hauswirth for expert technical assistance. This investigation received financial support from the National Institutes of Health (AI056489 R.L.M).

Abbreviations:

- APC

antigen-presenting cell

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GFP

green fluorescence protein

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- IRES

internal ribosome entry site

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- MIIC

MHC class II compartment

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- TCR

T-cell receptor.

References

- 1.Trombetta ES, Mellman I. Cell biology of antigen processing in vitro and in vivo. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:975–1028. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honey K, Rudensky AY. Lysosomal cysteine proteases regulate antigen presentation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:472–82. doi: 10.1038/nri1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watts C. Capture and processing of exogenous antigens for presentation on MHC molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:821–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pathak SS, Blum JS. Endocytic recycling is required for the presentation of an exogenous peptide via MHC class II molecules. Traffic. 2000;1:561–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delvig AA, Robinson JH. Different endosomal proteolysis requirements for antigen processing of two T-cell epitopes of the M5 protein from viable Streptococcus pyogenes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3291–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinet VM, Long EO. Peptide loading onto recycling HLA-DR molecules occurs in early endosomes. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:799–804. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199803)28:03<799::AID-IMMU799>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Musson JA, Walker N, Flick-Smith H, Williamson ED, Robinson JH. Differential processing of CD4 T-cell epitopes from the protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52425–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beckman EM, Porcelli SA, Morita CT, Behar SM, Furlong ST, Brenner MB. Recognition of a lipid antigen by CD1-restricted αβ+ T cells. Nature. 1994;372:691–4. doi: 10.1038/372691a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sieling PA, Chatterjee D, Porcelli SA, et al. CD1-restricted T cell recognition of microbial lipoglycans. Science. 1995;269:227–30. doi: 10.1126/science.7542404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moody DB, Reinhold BB, Guy MR, et al. Structural requirements for glycolipid antigen recognition by CD1b-restricted T cells. Science. 1997;278:283–6. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moody DB, Ulrichs T, Muhlecker W, et al. CD1c-mediated T-cell recognition of isoprenoid glycolipids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Nature. 2000;404:884–8. doi: 10.1038/35009119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, et al. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of Valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278:1626–9. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugita M, Jackman RM, van Donselaar E, et al. Cytoplasmic tail-dependent localization of CD1b antigen-presenting molecules to MIICs. Science. 1996;273:349–52. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5273.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugita M, Grant EP, van Donselaar E, et al. Separate pathways for antigen presentation by CD1 molecules. Immunity. 1999;11:743–52. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Briken V, Jackman RM, Watts GF, Rogers RA, Porcelli SA. Human CD1b and CD1c isoforms survey different intracellular compartments for the presentation of microbial lipid antigens. J Exp Med. 2000;192:281–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prigozy TI, Sieling PA, Clemens D, et al. The mannose receptor delivers lipoglycan antigens to endosomes for presentation to T cells by CD1b molecules. Immunity. 1997;6:187–97. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80425-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behar SM, Porcelli SA, Beckman EM, Brenner MB. A pathway of costimulation that prevents anergy in CD28– T cells: B7-independent costimulation of CD1-restricted T cells. J Exp Med. 1995;182:2007–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melian A, Geng YJ, Sukhova GK, Libby P, Porcelli SA. CD1 expression in human atherosclerosis. A potential mechanism for T cell activation by foam cells. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:775–86. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65176-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ridley DS, Jopling WH. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. A five-group system. Int J Lepr. 1966;34:255–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J, Sette A, Rodda S, et al. Determinants of T cell reactivity to the Mycobacterium leprae GroES homologue. J Immunol. 1997;159:335–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugita MWN, Rogers RA, Peters PJ, Brenner MB. CD1c molecules broadly survey the endocytic system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8445–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150236797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D'Souza-Schorey C, Li G, Colombo MI, Stahl PD. A regulatory role for ARF6 in receptor-mediated endocytosis. Science. 1995;267:1175–8. doi: 10.1126/science.7855600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andre S, Seed B, Eberle J, Schraut W, Bultmann A, Haas J. Increased immune response elicited by DNA vaccination with a synthetic gp120 sequence with optimized codon usage. J Virol. 1998;72:1497–503. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1497-1503.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stenger S, Hanson DA, Teitlebaum R, et al. An antimicrobial activity of cytolytic T cells mediated by granulysin. Science. 1998;282:121–5. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rivoire B, Pessolani MC, Bozic CM, et al. Chemical definition, cloning, and expression of the major protein of the leprosy bacillus. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2417–25. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2417-2425.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackman RM, Stenger S, Lee A, et al. The tyrosine-containing cytoplasmic tail of CD1b is essential for its efficient presentation of bacterial lipid antigens. Immunity. 1998;8:341–51. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80539-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aruffo A, Seed B. Expression of cDNA clones encoding the thymocyte antigens CD1a, b, c demonstrates a hierarchy of exclusion in fibroblasts. J Immunol. 1989;143:1723–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters PJ, Hsu VW, Ooi CE, et al. Overexpression of wild-type and mutant ARF1 and ARF6: distinct perturbations of nonoverlapping membrane compartments. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:1003–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amigorena S, Drake JR, Webster P, Mellman I. Transient accumulation of new class II MHC molecules in a novel. Nature. 1994;369:113–20. doi: 10.1038/369113a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tulp A, Verwoerd D, Dobberstein B, Ploegh HL, Pieters J. Isolation and characterization of the intracellular MHC class II compartment. Nature. 1994;369:120–6. doi: 10.1038/369120a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong G, Reis e Sousa C, Germain RN. Production, specificity, and functionality of monoclonal antibodies to specific peptide–major histocompatibility complex class II complexes formed by processing of exogenous protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13856–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delvig AA, Robinson JH. Two T cell epitopes from the M5 protein of viable Streptococcus pyogenes engage different pathways of bacterial antigen processing in mouse macrophages. J Immunol. 1998;160:5267–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stimac E, Lyons S, Pious D. Transcription of HLA class II genes in the absence of B-cell-specific octamer-binding factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:3734–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.9.3734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang CH, Fontes JD, Peterlin M, Flavell RA. Class II transactivator (CIITA) is sufficient for the inducible expression of major histocompatibility complex class II genes. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1367–74. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonehill A, Heirman C, Thielemans K. Genetic approaches for the induction of a CD4+ T cell response in cancer immunotherapy. J Gene Med. 2005;7:686–95. doi: 10.1002/jgm.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriguez F, Harkins S, Redwine JM, de Pereda JM, Whitton JL. CD4(+) T cells induced by a DNA vaccine. Immunological consequences of epitope-specific lysosomal targeting. J Virol. 2001;75:10421–30. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10421-10430.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu TC, Guarnieri FG, Staveley-O'Carroll KF, et al. Engineering an intracellular pathway for major histocompatibility complex class II presentation of antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11671–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ji H, Wang TL, Chen CH, et al. Targeting human papillomavirus type 16, E7 to the endosomal/lysosomal compartment enhances the antitumor immunity of DNA vaccines against murine human papillomavirus type 16, E7-expressing tumors. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:2727–40. doi: 10.1089/10430349950016474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arruda LB, Sim D, Chikhlikar PR, et al. Dendritic cell-lysosomal-associated membrane protein (LAMP) and LAMP-1-HIV-1 gag chimeras have distinct cellular trafficking pathways and prime T and B cell responses to a diverse repertoire of epitopes. J Immunol. 2006;177:2265–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]