Abstract

Sialidases remove sialic acid residues from various sialo-derivatives. To gain further insights into the biological roles of sialidases in vertebrates, we exploited zebrafish (Danio rerio) as an animal model. A zebrafish transcriptome- and genome-wide search using the sequences of the human NEU polypeptides as templates revealed the presence of seven different genes related to human sialidases. neu1 and neu4 are the putative orthologues of the mammalian sialidases NEU1 and NEU4 respectively. Interestingly, the remaining genes are organized in clusters located on chromosome 21 and are all more closely related to mammalian sialidase NEU3. They were thus named neu3.1, neu3.2, neu3.3, neu3.4 and neu3.5. Using RT–PCR (reverse transcription–PCR) we detected transcripts for all genes, apart from neu3.4, and whole-mount in situ hybridization experiments show a localized expression pattern in gut and lens for neu3.1 and neu4 respectively. Transfection experiments in COS7 (monkey kidney) cells demonstrate that Neu3.1, Neu3.2, Neu3.3 and Neu4 zebrafish proteins are sialidase enzymes. Neu3.1, Neu3.3 and Neu4 are membrane-associated and show a very acidic pH optimum below 3.0, whereas Neu3.2 is a soluble sialidase with a pH optimum of 5.6. These results were further confirmed by subcellular localization studies carried out using immunofluorescence. Moreover, expression in COS7 cells of these novel zebrafish sialidases (with the exception of Neu3.2) induces a significant modification of the ganglioside pattern, consistent with the results obtained with membrane-associated mammalian sialidases. Overall, the redundancy of sialidases together with their expression profile and their activity exerted on gangliosides of living cells indicate the biological relevance of this class of enzymes in zebrafish.

Keywords: comparative genomics, evolution, neuraminidase, sialidase, zebrafish

Abbreviations: DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; dpf, days post-fertilization; EST, expressed sequence tag; FBS, fetal bovine serum; hpf, hours post-fertilization; HPTLC, high-performance TLC; IMAGE consortium, Integrated Molecular Analysis of Genomes and their Expression consortium; LAMP1, lysosome-associated membrane protein 1; 4-MU-NeuAc, 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-D-N-acetylneuraminic acid; ORF, open reading frame; PBST, PBS containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20; PDI, protein disulfide-isomerase, RT–PCR, reverse transcription–PCR; UCSC, University of California Santa Cruz

INTRODUCTION

Sialidases or neuraminidases (EC 3.2.1.18) comprise a family of glycohydrolytic enzymes that remove terminal sialic acid residues from various sialo-derivatives, such as glycoproteins, glycolipids (gangliosides) and oligosaccharides. These exoglycosidases are widely distributed in Nature, including in viruses, protozoa, bacteria, fungi, mycoplasma, other micro-organisms and vertebrates [1]. Starting in 1993, 11 mammalian sialidases from different species have been cloned [2]. Despite the significant degree of homology and the presence of highly conserved regions along the primary structure, the mammalian sialidases cloned so far differ in their subcellular localization and substrate specificities. The sialidase protein family can be divided into four main groups: the lysosomal sialidase NEU1, the soluble or cytosolic sialidase NEU2, the plasma-membrane-associated sialidase NEU3, and the intracellular-membrane-associated sialidase NEU4. The human lysosomal sialidase NEU1 is part of a multienzyme complex containing β-galactosidase and the protective protein cathepsin A and is implicated in the severe lysosomal storage disorders sialidosis and galactosialidosis [3]. The role of the cytosolic sialidase NEU2 is rather puzzling because the content of natural substrates in this subcellular compartment is expected to be very low. Nevertheless, the enzyme plays a pivotal role in the in vitro differentiation of rat L6 myogenic cells into myotubes [4] and its stable expression in the A431 human carcinoma cell line leads to a diminished GM3 ganglioside level and an enhanced EGF (endothelial growth factor) receptor tyrosine autophosphorylation [5]. The plasma membrane-associated sialidase NEU3 is the most extensively studied member of the family and is characterized by a high degree of specificity towards ganglioside substrates [2]. The overexpression of NEU3 dramatically modifies the cell ganglioside content and is also able to affect gangliosides exposed on the extracellular leaflet of the plasma membrane of adjacent cells by cell–cell interaction [6]. The enzyme has been shown to be associated with caveolin in lipid rafts [7] and plays a pivotal role in different cellular processes including neuronal differentiation [8] and tumorigenic transformation [9]. NEU4 was originally described as a particulate enzyme associated with the inner cell membranes [10,11]. More recently, a human isoform with 12 additional amino acid residues at the N-terminus has been identified and shown to be associated with the mitochondrial membranes [12]. Intriguingly, NEU4 has been demonstrated to localize in the lysosomal lumen and its over-expression in fibroblasts derived from sialidosis and galactosialidosis patients results in clearance of storage materials from lysosomes, suggesting a role for NEU4 in lysosomal function [13].

To gain further insights into the biological roles of the different sialidases in vertebrates, we decided to utilize zebrafish (Danio rerio) as animal models. The present paper describes for the first time the systematic identification and characterization of zebrafish neu genes and provides interesting clues to the possible functions of these novel sialidases in zebrafish.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In general, standard molecular biology techniques were carried out as described by Sambrook and Russell [14]. DNA restriction and modifying enzymes were from Roche. Powder and reagents were from Sigma unless otherwise indicated. Cell culture media, antibiotics and animal serum were from Gibco. Silica gel-precoated HPTLC (high-performance plates, TLC Kieselgel 60, 20 cm×10 cm) were purchased from Merck GmbH. Sphingosine was prepared from cerebroside and [1-3H]sphingosine (radiochemical purity >98%, specific radioactivity 2.08 Ci/mmol) was prepared by specific chemical oxidation of the primary hydroxy group of sphingosine followed by reduction with sodium boro-[3H]hydride as previously described [6]. Radioactive sphingolipids were extracted from cells fed with [1-3H]sphingosine, purified and used as chromatographic standards.

Bioinformatic analysis

Nucleotide sequence assembly and editing was performed using both the AutoAssembler version 2.1 (PerkinElmer Applied Biosystems) and DNA Strider 1.4 [15] programs. Zebrafish genomic sequences were analysed using the UCSC (University of California Santa Cruz) Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) [16] on the Zv6 (March 2006) zebrafish assembly. The zebafish sialidase gene sequences have been also validated on the Zv7 (July 2007) genome assembly. Fugu (Takifugu rubripes) sialidase genes have been identified by BLAST analysis on the version 4.0 release of the Japanese pufferfish genome sequence [17].

Multiple sequence alignment was performed using the ClustalW algorithm [18]. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the http://www.phylogeny.fr service. Briefly, the multiple sequence alignment was generated using Muscle (version 3.6) [19], alignment refinement was obtained using Gblocks [20] and phylogenetic reconstruction was performed using the maximum likelihood program PhyML [21]. Nucleotide and amino acid sequences were compared with the non-redundant sequence databases present at the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) using the BLAST algorithm [22]. The prediction of transmembrane domains was performed using the Kyte–Doolittle algorithm implemented in DNA Strider. Primary-structure analysis and post-translational modification prediction was performed using the ExPASy Proteomics tools listed at http://au.expasy.org/tools/. For N-glycosylation site prediction, the NetNGlyc 1.0 Server was used, at http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/; phosphorylation sites were predicted using the NetPhos 2.0 Server at http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetPhos/. Finally, potential O-β-GlcNAc attachment site prediction was performed using the YinOYang 1.2 Prediction Server at http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/YinOYang/.

Isolation of zebrafish sialidase cDNAs

IMAGE {the IMAGE consortium is the Integrated Molecular Analysis of Genomes and their Expression consortium [at St. Louis, MO, U.S.A., and at the Human Genome Mapping Project (HGMP), Hinxton Hall, Cambridge, U.K.]} cDNA clones were obtained from Geneservice. We have determined the full-insert sequence of clones 7067630, 7036960, 7257445 and 7275043. Automated sequencing (using an Applied Biosystems ABI 3100 fluorescence sequencer) was performed using both vector- and gene-specific oligonucleotide primers.

RT–PCR (reverse transcription–PCR) analyses

Total RNA was isolated from zebrafish embryos at different developmental stages using the TRIzol® protocol (Gibco). cDNA was prepared from 1 μg of total RNA, using an Access RT-PCR System kit (Promega) in the presence of random hexamer oligonucleotides, following the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was carried out using the following forward and reverse primers: neu3.1-1F (5′-GTTCCTTGCCTTTGCTGAAG-3′) and neu3.1-1R (5′-CTGTTCCTCAGCCATTGGAT-3′); NEU3.2-5′HindIII (5′-CCCAAGCTTGGACCATGGAAAAACAACTTGGAAGCA-3′) and zfB-R3 (5′-AAAGGCGTGCCTGATTCTTA-3′); neu3.3-1F (5′-GGGTGGATGCCAAGACTAAA-3′) and neu3.3-1R (5′-GGTGTGAAGCAGCAGAATGA-3′); zfD-F3 (5′-CATCAAGCCATTCAGCTCCTCC-3′) and zfD-R5 (5′-CATAGACCGGACATGGATTCATGGAT-3′); neu3.5-1F (5′-CAGCTCCTCCCGAAATATCA-3′) and neu3.5-1R (5′-CCAGGTTTCACCAGTGTCCT-3′); neu4-2F (5′-TGACGCGTCTTTGTTACGTT-3′) and neu4-2R (5′-CGAGGTCTTGCACGTCTTG-3′).

For zebrafish β-actin amplification (GenBank® accession number AF057040) the following specific primers were used: 5′-TGTTTTCCCCTCCATTGTTGG-3′ and 5′-TTCTCCTTGATGTCACGGAC-3′. Amplification was performed for 35 cycles (57 °C annealing) following the instructions for AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems).

Fish breeding and embryo collection

Adult zebrafish were bred by natural crosses. Immediately after spawning, the fertilized eggs were harvested, washed and placed in 100-mm-diameter Petri dishes (Corning Life Sciences) in fish water [23]. The developing embryos were incubated at 28.5 °C until use. Zebrafish embryos were fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde/PBS overnight at 4 °C, rinsed twice in PBS/1% Tween 20, then dehydrated in methanol and stored at −20 °C until processing. Developmental stages of zebrafish embryos were expressed as hpf or dpf (hours or days post-fertilization respectively) at 28.5 °C.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Single hybridizations and detections were carried out on wild-type embryos [24]. Antisense and sense RNA probes were prepared by in vitro transcribing linearized cDNA clones or PCR products with T7, T3 or SP6 polymerase as indicated, using digoxigenin labelling mixture (Roche). In particular, a 1376 bp neu3.1 antisense riboprobe was synthesized with T7 polymerase by transcribing the EcoRI-linearized IMAGE cDNA clone 7036960. The corresponding sense riboprobe was synthesized with SP6 RNA polymerase using the XhoI-cleaved IMAGE clone 7036960. To prepare neu4 RNA probes, a 833 bp fragment was amplified by PCR using the IMAGE clone 7275043 as template and the following primers carrying the appropriate T3 and T7 consensus promoter sequences: T3-neu4/ex3F (5′-CAGAGATGCAATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGAAGTGGGCCACTTTTGCTGTGG-3′) and T7-neu4/ex3R (5′-CCAAGCTTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAGCAGATAAAGCAGCGCTCCCAG-3′). neu4 antisense and sense probes were then synthesized by transcribing the PCR products with T7 and T3 polymerases respectively. Stained embryos were mounted in glycerol, observed on a Leica DMR compound microscope equipped with Nomarski optics and acquired with a Leica DC500 digital camera.

Expression constructs

The coding regions of neu3.1, neu3.2, neu3.3 and neu4 were amplified by PCR using cloned Pfu Turbo polymerase (Stratagene) and the corresponding IMAGE cDNA clone as template (clone 7067630, 7036960, 7257445 and 7275043 respectively). Since no EST (expressed sequence tag) clones corresponding to the neu3.4 and neu3.5 transcripts were available, the two corresponding genes were amplified from the zebrafish genomic DNA template. The PCR products were then digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes and cloned into the pcDNA3.1/myc-His (Invitrogen) (neu3.1, neu3.2 and neu3.3) or pMT21 vector [25] (neu4) to generate an ORF (open reading frame) encoding neu3.1, neu3.2, neu3.3 or neu4 with a C-terminal Myc tag.

The following forward and reverse oligonucleotides were used in PCR amplification of the gene ORFs: neu3.1, NEU3.1-5′BamHI (5′-CGGGATCCACCATGTTTTTTACTTACGTTTATG-3′) and NEU3.1-3′XhoI (5′-CCCTCGAGAGAGCACAATAAATCATTAAGT-3′); neu3.2, NEU3.2-5′HindIII (5′-CCCAAGCTTGGACCATGGAAAAACAACTTGGAAGCA-3′) and NEU3.23′-XhoI (5′-CCCTCGAGAATAACCTCTTTGTGTTCAAAC-3′); neu3.3, NEU3.3-5′BamHI (5′-CGGGATCCACCATGGGCAACAAGACACCGTCAA-3′) and NEU3.33′XhoI (5′-CCCTCGAGCAGCTTTTTCTCAGGGAGTTTG-3′); neu3.4, NEU3.4-5′BamHI (5′-CGGGATCCACCATGATGGCGTATTCATCAAGCCA-3′) and NEU3.4-3′XhoI (5′-CCCTCGAGCAGCTTTTTCTCAGGGAGTTTG-3′); neu3.5, NEU3.5-5′BamHI (5′-CGGGATCCACCATGATGGGTTGCTGTTGCCTG-3′) and NEU3.5-3′XhoI (5′-CCCTCGAGATTCTGTTTAGTAAATTTGG-3′); neu4, NEU4 5′EcoRI (5′-CGGAATTCATGGGGTCTCAATACTACCCA-3′) and NEU4 3′SalI (5′-ACGCGTCGACGGCAGATAAAGCAGCGCTCCCAGAT-3′). Amplifications were carried out according to cycling parameters indicated for Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase for 35 cycles. Annealing steps were performed at 53 °C (neu3.1), 52 °C (neu3.2 and neu3.3) and 56 °C (neu3.4 and neu3.5). Each clone sequence was confirmed by automated fluorescence sequencing.

Cell culture and transient transfections

The African green monkey kidney cell line COS7 were maintained in DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FBS (fetal bovine serum), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. For transfection, COS7 cells were seeded on 100-mm-diameter culture dishes or on sterile glass coverslips (BDH) in six-well plates (Corning Life Sciences) and grown for 24 h before transfection. Transfections were performed using 2–6 μg of plasmid DNA and FuGENE™ 6 transfection reagent (Roche), according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

For neu1 transfection experiments, we used the IMAGE cDNA clone 7218457 carrying the complete ORF in the pME18S-FL3 expression vector. For Neu3.2 co-localization experiments, HsNEU2-pIRESneo (Clontech) was co-transfected with the Neu3.2-Myc construct. Transfections with the same amount of pcDNA3.1/myc-His or pMT21 expression vector were used as negative controls (mock). Cells were collected for protein analysis, enzymatic activity assay or fixed for immunofluorescence at different times after transfection.

Immunofluorescence and confocal analysis

Transfected cells grown on coverslips were rinsed with ice-cold PBS, immediately fixed and permeabilized with pre-cooled 100% methanol at −20 °C for 10 min and washed in PBS. Cells were subsequently immunolabelled using an indirect procedure in which all incubations (primary and secondary antibodies and washes) were performed in PBS containing 1% BSA. Primary antibodies used were: rabbit anti-human NEU2 [26], rabbit anti-Myc (Sigma), mouse anti-Myc (Sigma), mouse anti-LAMP1 (lysosome-associated membrane protein 1) (BD Biosciences), rabbit anti-calnexin (Stressgen), mouse anti-PDI (protein disulfide-isomerase) (Stressgen) and mouse anti-cythocrome c (Promega). Staining was obtained after incubation with Alexa Fluor 488- and/or 555-conjugated isotype-specific antibodies (Molecular Probes). Controls included staining with each secondary antibody separately. Coverslips were then washed in PBS, mounted on a glass microscopic slide (BDH) with fluorescence mounting medium (Dako) and examined using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope equipped with the confocal laser system LSM 510 META. Image processing was performed with Adobe Photoshop software.

Protein extraction

Transfected COS7 cells were harvested by scraping, washed in PBS and resuspended in the same buffer containing 60 μg/ml chymotrypsin, 8 μg/ml pepstatin A, 32 μg/ml apoprotinin and 32 μg/ml leupeptin. Total cell extracts were prepared by sonication. The supernatant obtained after centrifugation at 800 g for 10 min represented the crude cell extract and was subsequently centrifuged at 100000 g for 60 min on an Optima T 80 ultracentrifuge (Beckman). Aliquots of the original crude cell extract, 100000 g supernatant and pellet were used for protein assay (Bio-Rad protein assay kit), Western blot analysis and enzymatic activity. All fractionation passages were carried out at 4 °C.

Western blot analysis

Protein samples were subjected to SDS/PAGE [10% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel] and subsequently transferred by electroblotting on to an Immobilon-P blotting membrane (Amersham Biosciences). The membranes were incubated for 30 min in PBST (PBS containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20) and 5% (w/v) non-fat dried skimmed milk powder (blocking buffer) and subsequently incubated with rabbit anti-Myc antibody (Zymed). After a final washing in PBST and incubation with horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (Amersham Biosciences), proteins were visualized using the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescencence substrate detection kit (Pierce).

Sialidase enzymatic assays

The enzymatic activity of the sialidase in total cell lysates and in cellular subfractions was determined using 4-MU-NeuAc [2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-D-N-acetylneuraminic acid] as substrate. Assays were performed with up to 30 μg of total proteins for Neu3.1, Neu3.2 and Neu3.3, and up to 5 μg of total proteins in the case of Neu4. Briefly, reactions were set up in triplicate in a final volume of 100 μl with 0.2 mM 4-MU-NeuAc, 600 μg BSA with 20 mM Tris/glycine buffer for assays ranging from pH 2.2 to 3.0 and with 12.5 mM sodium citrate/phosphate buffer for assays ranging from pH 2.6 to 7. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and reactions were stopped by the addition of 1.5 ml of 0.2 M glycine/NaOH, pH 10.4. Fluorescence emission was measured on a Jasco FP-770 fluorimeter with excitation at 365 nm and emission at 445 nm, using 4-methylumbelliferone to set up a calibration curve [27].

Treatment of cell cultures with [1-3H]sphingosine

A proper amount of [1-3H]sphingosine, dissolved in methanol, was transferred into a sterile glass tube and dried under a nitrogen stream. The resulting residue was then dissolved in an appropriate volume of pre-warmed (37 °C) 10% FBS/DMEM to obtain a final concentration of 3×10−8 M (corresponding to 0.4 μCi/100-mm-diameter dish). Transfected COS7 cells were incubated for a 2 h pulse followed by a 40 h chase, except for Neu4-transfected COS7 cells that were followed by a 20 h chase. Cells were harvested by scraping, washed in PBS, snap frozen, freeze-dried and subjected to lipid extraction and sphingolipid analyses.

Lipid extraction and analyses

Total cell extracts obtained after [1-3H]sphingosine labelling were freeze-dried and extracted twice with chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v). The resulting lipid extracts were dried under a nitrogen stream and dissolved in chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v). The total lipid extracts were counted for radioactivity and subjected to a two-phase partitioning in chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v), and 20% water; the aqueous and organic phases obtained were counted for radioactivity. [3H]Sphingolipids of aqueous and organic phases were analysed by HPTLC using the solvent systems chloroform/methanol/0.2% aqueous CaCl2 (60:40:9, by vol.), and chloroform/methanol/water, (110:40:6, by vol.) respectively. [3H]Sphingolipids were identified referring to radiolabelled standards and quantified by radiochromatoimaging (Beta-Imager 2000, Biospace) [6].

RESULTS

Identification and organization of sialidase genes in zebrafish

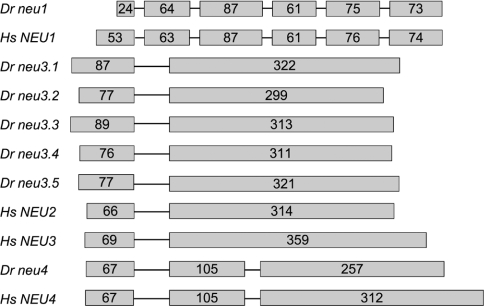

To isolate genes encoding for sialidases in zebrafish, we carried out a genome-wide search using the sequences of the human NEU1, NEU2, NEU3 and NEU4 polypeptides as a query. Our study was performed using both the TBLASTN and BLAT algorithms against the March 2006 zebrafish Zv6 assembly of genomic sequences. This analysis led to the identification of seven putative sialidase genes whose general features are summarized in Supplementary Table S1 (http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/408/bj4080395add.htm). One gene is located on chromosome 19 (Figure 1A), and several ESTs have been identified in dbEST corresponding to the gene transcript. We characterized the IMAGE clone 7218457 that contains the entire ORF. The putative encoded protein shows a high degree of amino acid sequence identity (58%) with human NEU1 (Supplementary Table S2, http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/408/bj4080395add.htm). Moreover, the gene is organized in six exons as the human counterpart and also the intron positions are conserved in the two species (Figure 2). On the basis of this evidence, this novel zebrafish gene has been named neu1.

Figure 1. Sialidase gene organization in zebrafish (Dr), fugu (Tr) and human (Hs).

Conservation of gene synteny around (A) neu1, (B) neu3 and (C) neu4 in zebrafish (Dr), fugn (Tr) and human (Hs). The arrows indicate the direction of gene transcription within each chromosome. Sialidase genes are depicted with grey arrows, while adjacent genes in syntenic regions are represented by black arrows. The size of the arrows is not proportional to that of the genes and the distances between genes are arbitrary. The white arrow indicates the human SPCS2 gene that appears to be absent from zebrafish and fugu genomes.

Figure 2. Exon–intron organization of human (Hs) and zebrafish (Dr) sialidase genes.

Introns are depicted by thin lines and their size is arbitrary. Exons are represented by grey boxes and their sizes are indicated by the number of encoded amino acids. Only coding exons have been considered. In the case of Hs NEU4, the 484-amino-acid protein isoform (GenBank® accession number CAC81904) is reported.

Interestingly, five sialidase-related sequences are clustered within 33 kb on chromosome 21 (Figure 1B). Only three of them were identified as cDNA clones in GenBank®, either as ESTs or full-insert cDNA sequences. DNA sequence analysis of the IMAGE clones 7067630, 7036960 and 7257445 indicates that they contain the entire protein-coding region. The predicted polypeptides encoded by the three genes show the highest sequence identity with human NEU3 (Supplementary Table S2). We thus adopted a numerical nomenclature (neu3.1, neu3.2 and neu3.3) for these three novel zebrafish genes, on the basis of their mapping location within the cluster (Figure 1B). In the case of the additional two genes found in the same cluster, since no cDNA clones were available in GenBank®, their putative coding sequences have been deduced in silico by (i) comparing the genomic sequences harbouring the two genes with human sialidase polypeptides, and (ii) the analysis of gene predictions available within the UCSC Genome Browser. The genomic stretches of the two genes from the putative ATG initiation codon to the stop codon, including the single intron present in both genes, were amplified by PCR from zebrafish genomic DNA and subcloned into pcDNA3.1 Myc-His expression vector. The resulting recombinant vectors were subsequently used to transfect COS7 cells, and RT-PCR carried out on the RNA extracted from these cells confirmed the in silico-predicted splicing sites. Also, in this case the encoded polypeptides show the highest sequence identity with human NEU3 (Supplementary Table S2); the two corresponding genes were thus named neu3.4 and neu3.5. The entire coding region of neu3.5 was successfully amplified by RT-PCR performed on adult zebrafish RNA (results not shown). All NEU3-like genes clustered on chromosome 21 are organized in two exons like human NEU2 and NEU3 and, in addition, the intron positions are also conserved in the two species (Figure 2).

A seventh sialidase family member was also identified. Although in the Zv6 sequence assembly its chromosomal location remains unassigned, the analysis of the Zv7 assembly allowed to locate it on chromosome 15 (Figure 1C). The nucleotide sequence analysis of the IMAGE cDNA clone 7275043 allowed us to derive its entire ORF. The encoded polypeptide shows the highest degree of amino acid sequence identity (48%) with human NEU4 (Supplementary Table S2). In addition, the putative gene coding region is the only one among zebrafish sialidases organized in three exons like human NEU4 (Figure 2). The gene was thus named neu4. Supplementary Table S3 (http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/408/bj4080395add.htm) reports the amino acid sequence identity among the seven zebrafish sialidases that we identified.

To gain further information about sialidases in ray-finned fish, we have extended the bioinformatic search to fugu, a teleost distantly related to zebrafish, whose genome has been completely sequenced [17]. This analysis led to the identification of only three sialidases that, by reciprocal BLAST comparisons with the mammalian enzymes, were shown to be the putative orthologues of human NEU1, NEU3 and NEU4. These novel fugu genes have been accordingly named neu1, neu3 and neu4. Interestingly, only these three sialidase genes have been found in the genomic sequence of another pufferfish, Tetraodon nigroviridis (results not shown).

We analysed the genomic regions surrounding the sialidase genes both in teleosts and in humans. A partial synteny can be observed in the region harbouring NEU1. In both zebrafish and fugu the gene is flanked by bat2 on one side and skiv2l and rdbp genes on the other. In the human genome, BAT2 is located on the distal side some 230 kb from NEU1, while RDBP and SKIV2L are on the centromeric side at approx. 90 kb (Figure 1A). Several genes are present between NEU1 and the above mentioned genes that cannot be found in the teleost genomes adjacent to neu1. This is not surprising considering that NEU1 lies within the MHC, a gene-dense region on chromosome 6p21.3 that comprises a group of genes that are functionally involved in the adaptive and innate immune system [28].

The zebrafish chromosome 21 sialidase cluster is flanked on the neu3.1 side by genes homologous with human XRRA1, CHRDL2 and POLD3. The same genes are found adjacent to the fugu neu3 sequence. Interestingly, the human NEU3 gene at chromosome locus 11q13.4 is similarly flanked on the centromeric side by XRRA1, CHRDL2 and POLD3 genes. There is no evidence of synteny conservation between human and zebrafish on the other side of the cluster (Figure 1B).

Finally, neu4 is flanked on one side, both in zebrafish and fugu, by sequences homologous with SRPRB and WD53 human genes mapping to chromosome 3q in humans. The presence of sequence gaps in the other side of the neu4 locus did not allow to study synteny in this region. Although both the exon–intron organization and amino acid sequence analysis suggest that neu4 is closely related to human NEU4, we could not detect synteny with human chromosome locus 2q37 where NEU4 and NEU2 both lie (Figure 1C).

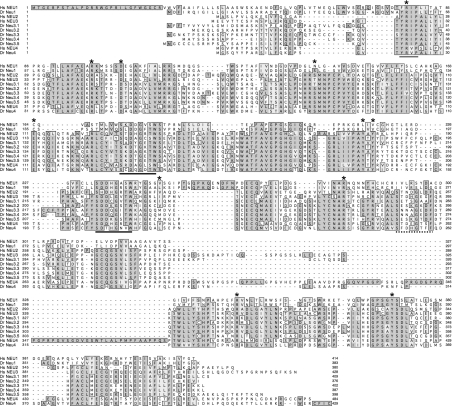

Analysis of zebrafish sialidase proteins

A multiple alignment of the amino acid sequences of the human and zebrafish sialidases further points out the high degree of amino acid sequence identity between zebrafish and human sialidases, with a large number of residue blocks highly conserved in topologically equivalent positions along the primary structure (Figure 3). As expected, the Y(F)RIP motif, typical of sialidases [29] and occurring near the N-terminus of these enzymes, is also present in all the zebrafish sialidases. In addition, zebrafish Neu polypeptides contain two well-conserved Asp blocks (consensus sequence SXDXGXTW, where X is any amino acid) [30] and, apart from NEU1 and its putative zebrafish orthologue Neu1, they also present one fewer conserved Asp box characterized by the SX(D/N/S)XGX(D)F extended consensus sequence. A remarkable conservation of the amino acids that are involved in the formation of the active-site of the human cytosolic sialidase NEU2 [31] is observed in zebrafish sialidases (Figure 3), suggesting a high conservation of the active-site architecture during vertebrate evolution. Interestingly, zebrafish Neu1 shows a shorter N-terminus compared with the human enzyme, in which the first 45 residues represent the signal peptide [32]. Similarly, zebrafish Neu4 lacks the approx. 80-amino-acid stretch located in the last third of the protein that appears to be exclusively present in NEU4 sialidases of mammalian origin [11]. Moreover, the YXXΦ motif (where Φ is a non-polar, aliphatic or aromatic residue) present at the C-terminus of mammalian NEU1 [32] as well as in several LAMPs [33], is poorly conserved in the zebrafish orthologue, where the C-terminal residue is a positively charged lysine residue.

Figure 3. Multiple sequence alignment of sialidases.

Multiple alignment of the amino acid sequences of zebrafish (Dr Neu1, Dr Neu3.1, Dr Neu3.2, Dr Neu3.3, Dr Neu3.4, Dr Neu3.5 and Dr Neu4) and human (Hs NEU1, Hs NEU2, Hs NEU3 and Hs NEU4) sialidases. The alignment was performed using the ClustalW algorithm (see the Materials and methods section). Residues that are identical are shown on a dark grey background; those on a light grey background and boxed are the conservative substitutions. The active amino acid residues derived from the crystallographic data of the human cytosolic sialidase NEU2 are indicated by asterisks (*) above the sequence. The conserved Y(F)RIP box is indicated by a grey bar under the sequences. Continuous or dotted black lines under the sequences indicate the canonical and poorly conserved Asp boxes respectively.

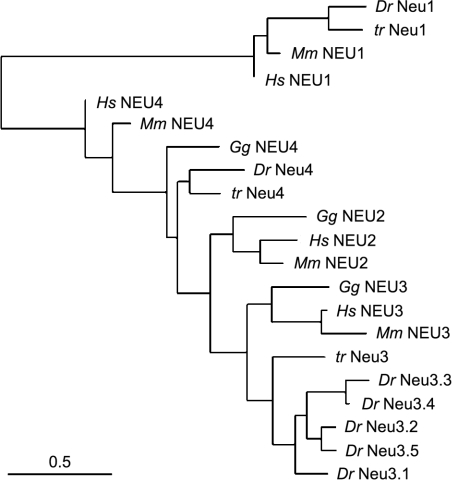

A phylogenetic tree of human, mouse, chicken, fugu and zebrafish sialidases is shown in Figure 4. This analysis further indicates that neu1 represents the zebrafish orthologue of the human NEU1 gene, while neu4 is more similar to NEU4. In contrast, Neu3.1–Neu3.5 proteins are highly similar and they all have the mammalian plasma membrane-associated sialidase NEU3 as the closest relative.

Figure 4. Unrooted phylogenetic tree depicting the evolutionary relationship of teleost, avian and mammalian sialidases.

The tree was generated as described in the Materials and methods section using the amino acid sequences of human (Hs), mouse (Mm), chicken (Gg), zebrafish (Dr) and fugu (Tr) sialidase polypeptides using GenBank® accession number NM_001044909 (zebrafish neu1 gene), NP_000425 (human NEU1), NP_005374 (human NEU2), BAA82611 (human NEU3), CAC81904 (human NEU4), NP_035023 (mouse NEU1), NP_056565 (mouse NEU2), NP_057929 (mouse NEU3), NP_776133 (mouse NEU4), XP_001231585 (chicken Neu2), XP_428099 (chicken Neu3), EF434604 (fugu Neu1), EF434605 (fugu Neu3), EF434606 (fugu Neu4) and from NW_001471743 (predicted chicken Neu4). It was not possible to identify a putative chicken orthologue of NEU1 in the 2.1 build of the Gallus gallus (chicken) genomic sequence. The horizontal bar represents a distance of 0.5 substitutions per site.

The general molecular features of zebrafish Neu polypeptides are reported in Table 1. The differences in molecular mass are modest, from 42 kDa in the case of Neu3.2 to 48.6 kDa in the case of Neu4. The pI values are below 7, with the exception of that for Neu3.2. As already reported in the case of the mammalian enzymes [2], all zebrafish sialidases except Neu3.4 show predicted N-glycosylation sites, and all but Neu4 show a number of predicted O-β-GlcNAc-attachment sites for glycosylation. Moreover, all of the polypeptides have a great number of amino acid residues that could be covalently modified by phosphorylation, suggesting that such a modification could be of relevance in the regulation of their biological behaviours. The Kyte–Doolittle hydrophobicity plots of the zebrafish Neu proteins (Supplementary Figure S1, http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/408/bj4080395add.htm) do not show typical transmembrane domains as observed previously for the mammalian counterparts [2].

Table 1. Comparison of the molecular properties of zebrafish sialidases.

The number of target amino acids for N-glycosylation, O-glycosylation and phosphorylation are indicated after the three letter amino acid code.

| Zebrafish sialidases | Amino acids | Molecular mass (kDa) | Theoretical pI | Potential N-glycosylation sites | Potential O-β-GlcNAc-attachment sites | Potential phosphorylation sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neu1 | 383 | 42.14 | 6.01 | Asn, 3 | Ser, 2 | Ser, 15; Thr, 4; Tyr, 1 |

| Neu3.1 | 409 | 46.2 | 6.63 | Asn, 2 | Thr, 1 | Ser, 13; Thr, 4; Tyr, 5 |

| Neu3.2 | 376 | 42 | 7.15 | Asn, 3 | Ser, 2; Thr, 4 | Ser, 12; Thr, 4; Tyr, 3 |

| Neu3.3 | 402 | 45.12 | 6.04 | Asn, 3 | Ser, 2; Thr, 1 | Ser, 16; Thr, 7; Tyr, 3 |

| Neu3.4 | 387 | 43.48 | 5.6 | − | Ser, 4 | Ser, 11; Thr, 4; Tyr, 4 |

| Neu3.5 | 398 | 44.42 | 6.75 | Asn, 1 | Ser, 3; Thr, 2 | Ser, 12; Thr, 5; Tyr, 2 |

| Neu4 | 429 | 48.6 | 5.96 | Asn, 2 | − | Ser, 15; Thr, 6; Tyr, 7 |

Analysis of zebrafish sialidase expression

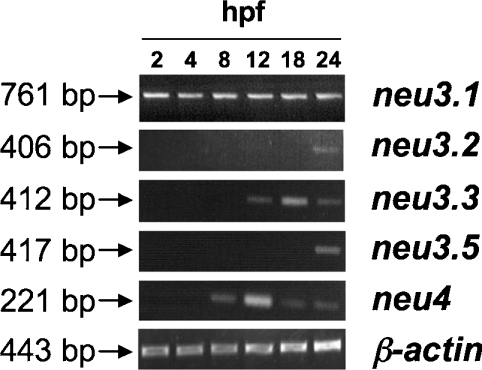

To find out at which stage of zebrafish development sialidases are transcribed, we analysed their temporal expression by RT-PCR at 2, 4, 8, 12, 18 and 24 hpf and 2, 3, 4, 5 dpf, as well as in the adult fish. As shown in Figure 5, neu3.1 is detected from early hours of development (2 hpf), neu3.3 and neu4 mRNAs are detected starting from 12 and 8 hpf respectively, while neu3.2 and neu3.5 transcripts are detected from 24 hpf. All genes mentioned above are expressed in the later stages of development we tested, as well as in the adult fish (results not shown). No RT-PCR amplification is observed for neu3.4 at any stage of development tested, even using different sets of oligonucleotide primers (results not shown). In agreement with our observations, the absence in the public databases of ESTs corresponding to neu3.4 transcripts further suggests that this gene is either expressed at a very low level or not expressed at all.

Figure 5. Temporal expression of neu3.1, neu3.2, neu3.3, neu3.4 and neu4 genes.

RT-PCR was performed on equal amounts of total RNA isolated from embryos at different developmental stages. Time points are expressed in hpf. The size (in bp) of the expected PCR products are reported on the left of the Figure. β-Actin was used as a positive RT-PCR control.

To detect mRNA in specific embryonic tissues we performed whole-mount in situ hybridizations. The high level of identity among neu3.2, neu3.3, neu3.4 and neu3.5 nucleotide sequences (results not shown) did not allow the synthesis of antisense riboprobes specific for all of these gene transcripts. Thus the whole-mount in situ hybridization studies were carried out only for neu3.1 and neu4, for which we could generate riboprobes showing approx. 70% sequence identity with the other gene transcripts.

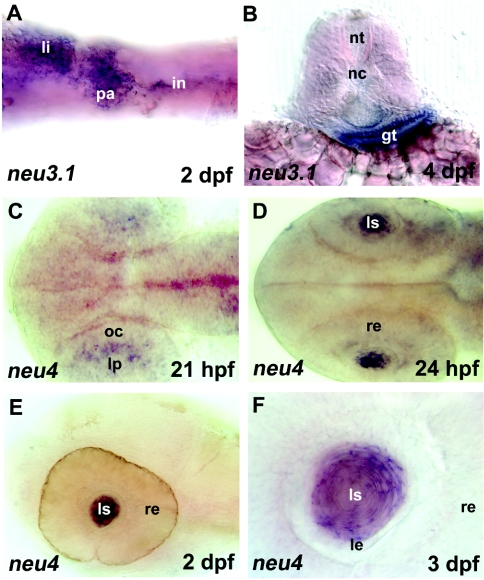

The two sialidase genes studied showed spatially localized expression in different tissues. In particular, neu3.1 transcripts were detected in the gut in embryos at 24 hpf until 6 dpf (Figures 6A and 6B). Expression of neu4 is detected in the lens of 21 and 24 hpf, and 2 and 3 dpf embryos (Figures 6C–6F). Hybridization of sense strand cRNA was performed as control and did not give hybridization signals above background (Supplementary Figure S2, http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/408/bj4080395add.htm).

Figure 6. In situ hybridization (expression pattern) of zebrafish sialidases neu3.1 and neu4.

(A) and (B), neu3.1 expression in the gut of 2 dpf and 4 dpf embryos. li, liver; pa, pancreatic area; in, intestine; nt, neural tube; nc, notochord; gt, gut tube. (C–F) neu4 expression in the eye region (lens placode) of a 25-somite (21 hpf) embryo (C) and in the lens of 24 hpf (D), 2 dpf (E) and 3 dpf (F) embryos. In the case of (F), a higher magnification is shown. lp, lens placode; oc, optic cup; re, retina; ls, lens; le, lens epithelium. Embryos are in ventral (A), dorsal (C, D) and lateral (E, F) views with anterior to the left. (B) is a 40 μm transversal vibratome section. Magnification: (A–D); 20×, (E) and (F); 100×.

Expression of zebrafish Neu1, Neu3.1, Neu3.2, Neu3.3 and Neu4 sialidases in COS7 cells

Biochemical characterization was carried out only for proteins encoded by neu genes for whom a full-coding IMAGE cDNA clone was available, thus excluding Neu3.4 and Neu3.5 from this analysis. Zebrafish neu1 was expressed in COS7 cells and sialidase activity was tested over a pH range from 2.2 to 7.0 (results not shown). Only a negligible increase of the enzymatic activity was detected at pH 2.8 compared with mock-transfected cells (Supplementary Figure S3, http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/408/bj4080395add.htm). This is not surprising considering that Neu1 is thought to represent the zebrafish orthologue of the human lysosomal sialidase NEU1. Interestingly, the zebrafish genome contains the putative orthologues of human cathepsin A (GenBank® accession number XM_001331869, chromosome 7) and β-galactosidase (GenBank® accession number NM_001017547, chromosome 1), suggesting that, in this teleost, Neu1 also forms the catalytically active supramolecular complex described in mammals [2]. Since these peculiar features set NEU1 apart from the other sialidases identified in mammals, we decided to focus our studies on the other members of the gene family.

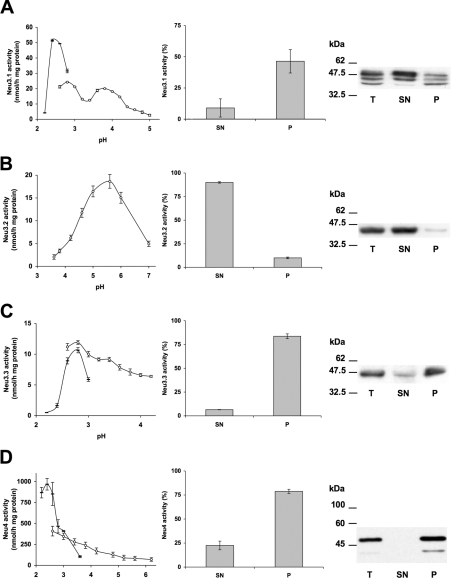

The complete ORFs of neu3.1, neu3.2, neu3.3 and neu4 genes were amplified by PCR using the corresponding IMAGE cDNA clones as template (IMAGE clones 7067630, 7036960, 7257445 and 7275043 respectively). The PCR products were subcloned into pcDNA3.1/Myc-His and pMT21 mammalian expression vectors. The resulting recombinant vectors, encoding chimaeric proteins with C-terminally-tagged Myc-His epitopes in the case of Neu3.1, Neu3.2 and Neu3.3 or the Myc epitope alone in the case of Neu4, were used to transiently transfect COS7 cells. Crude homogenates from transfected cells were tested for sialidase activity using the artificial substrate 4-MU-NeuAc. Transient transfection experiments with the different zebrafish cDNAs lead to a significant increase of the sialidase activity. Neu4 expression led to the highest rate of hydrolysis; however, in the case of Neu3.1-, Neu3.2- and Neu3.3-expressing cells, the sialidase activity detected is lower (Supplementary Figure S3). The measurement of the sialidase activity at different pH values, from 2.2 to 7.0, reveals that the enzymes have peculiar pH optima. Neu3.1, Neu3.3 and Neu4 show a very acidic optimal pH that is 2.6, 2.8 and 2.6 respectively (Figures 7A, 7C and 7D), whereas Neu3.2 shows a less acidic value, corresponding to pH 5.6 (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Biochemical characterization of zebrafish sialidases.

(A) Neu3.1-, (B) Neu3.2- and (C) Neu3.3- and (D) Neu4-Myc fusion proteins were expressed in COS7 cells. Left column: the specific activity of different zebrafish sialidases towards 4-MU-NeuAc over the pH range 2.2–7.0. The enzymatic assay was carried out using Tris/glycine buffer from pH 2.2 to 3.0 (black bar) and sodium citrate/phosphate buffer from pH 2.6 to 7 (white circle). Variations of the values are indicated by the error bars (n=4). Middle column: sialidase activity of the supernatant (SN) and pellet (P) obtained by ultracentrifugation of the total lysates at 100000 g. The rate of hydrolysis of 4-MU-NeuAc is expressed as a percentage of the value detectable in the total lysates. Variations of the values are indicated by the error bars (n=3). Right column: Western blot analysis of protein sample (20 μg) of total cell lysate (T) and supernatant (SN) and pellet (P) obtained by ultracentrifugation. Detection of the fusion proteins was performed using anti-Myc antibody and secondary horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated isotype-specific antibody, followed by chemiluminescence developing reagents. Sizes are given in kDa.

To analyse the subcellular localization of the different zebrafish sialidase enzymes, fractionation into soluble and particulate cell materials was carried out by ultracentrifugation of the crude homogenate of COS7 cells transfected with the various recombinant vectors. As shown in Figures 7(C) and 7(D), more than 80% of the Neu3.3 and Neu4 enzymatic activity detectable in the crude homogenates was recovered in the rough particulate fraction, demonstrating the association of these enzymes with membranous material. In the case of Neu3.1, the recovery in the particulate fraction was lower (46%), but the association with the rough particulate fraction was still evident (Figure 7A). Conversely, Neu3.2 clearly appears to be a soluble enzyme, its activity being recruited in the soluble cell compartments after ultracentrifugation of the total cell lysate (Figure 7B). These results have been further confirmed by Western blot analysis using an anti-Myc monoclonal antibody. Bands of 47.5 and 49.8 kDa, corresponding to Neu3.3 and Neu4 proteins respectively, are associated with the 100000 g rough particulate fraction. In contrast, in Neu3.2-expressing cells, Western blot analysis showed a band of 44.5 kDa, corresponding to Neu3.2, that is highly enriched in the soluble fraction (Figure 7B). Finally, with Neu3.1, Western blot analysis revealed in the total cell extract a major band with the expected molecular mass of 48.6 kDa, together with two additional minor protein bands of 46 and 44 kDa. Surprisingly, after ultracentrifugation, the same bands are detectable in both the soluble and rough particulate membrane fractions, with an enrichment of the higher-molecular-mass protein band in the supernatant compared with the pelleted material, as would be expected from the enzyme activity distribution. A possible explanation of this result could be that the protein, detached from the membranes, is somehow less active and/or lacks some cofactor essential for catalysis, as suggested from the low recovery of the enzyme activity after cell fractionation.

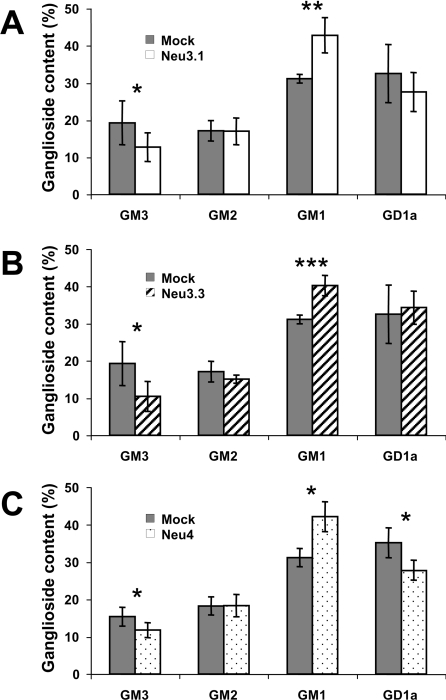

Zebrafish Neu activity in living COS7 cells

To assess the possible sialidase activity of Neu3.1, Neu3.2, Neu3.3 and Neu4 towards gangliosides, COS7 cells were pulsed with [1-3H]sphingosine and transiently transfected with recombinant plasmids carrying zebrafish cDNAs. The incorporation of the radiolabelled precursor leads to an extensive labelling of the cell sphingolipids [34] and the comparison of the lipid pattern detectable in mock and transfected cells is related to the effects that the enzyme expression exerts on the sphingolipid compartment of intact cells. After a 2 h pulse with [1-3H]sphingosine followed by a 20–40 h chase, free sphingosine was hardly detectable within the radioactive lipid mixtures, and stable radioactive lipid patterns were observed in mock-transfected cells (results not shown). In the case of COS7 cells expressing Neu3.1, Neu3.2 and Neu4, the sphingolipid patterns showed significant variations (Figure 8), whereas no differences were detectable in Neu3.2-transfected cells (results not shown). In particular, Neu3.1 and Neu3.3 expression for 40 h induced roughly a 37 and 46% decrease of the ganglioside GM3 and a 29 and 27% increase of ganglioside GM1 cell content respectively (Figures 8A and 8B). In the case of Neu4-expressing cells, the effects on ganglioside pattern are more pronounced (Figure 8C). In fact, after only 24 h of expression, roughly a 23 and 21% decrease of ganglioside GM3 and GD1a relative content respectively, and a 26% increase of ganglioside GM1 content were detectable. In addition in Neu4 expressing cells a 11% increase of lactosylceramide relative content was detectable (results not shown). No other statistically significant differences were observed between lipid patterns of the organic phase from mock-, neu3.1-, neu3.2-, neu3.3- and neu4-transfected cells (results not shown).

Figure 8. Ganglioside pattern of COS7 cells expressing zebrafish sialidases Neu3.1, Neu3.3 and Neu4.

Cells transfected with the different zebrafish sialidases were pulsed for 2 h with [1-3H]sphingosine, 30 nM final concentration. After 40 h (Neu3.1 and Neu3.3) and 20 h chase (Neu4), cells were harvested and treated for lipid analysis (see the Materials and methods section). The ganglioside relative contents are compared with the one observed in mock-transfected cells. Variations in the ganglioside relative contents are indicated by the error bars (n=6). Significance according to Student's t test: *, P<0.05; **, P<0.005; ***, P<0.0005.

Subcellular localization of Neu3.1, Neu3.2, Neu3.3 and Neu4

The subcellular distribution of Neu3.1, Neu3.2, Neu3.3 and Neu4 zebrafish enzymes has been studied by indirect immunofluorescence. Laser confocal analysis further confirms the results obtained with cellular fractionation and Western blot techniques. Neu3.1 shows a diffused intracellular labelling pattern and localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum, as shown by its restricted distribution to calnexin- (Figure 9A) and PDI-positive structures (Supplementary Figure S4, http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/408/bj4080395add.htm). Neu3.2 was detected as a cytosolic protein (Figure 9B) with a subcellular distribution roughly superimposable on the one observed in the case of cells expressing the human cytosolic sialidase NEU2 [26]. Neu3.3 showed a typical membranous distribution, with an extensive labelling at the cell surface and in a well-defined membrane network inside the cells (Figure 9C). Double labelling experiments using endoplasmic reticulum (calnexin and PDI), mitochondrial (cytochrome c) and Golgi apparatus (GM130) markers did not reveal any significant co-localization (results not shown), whereas a partial co-localization was detectable in LAMP1-positive vesicles, corresponding to the late endosomes/lysosome compartment (Figure 9C). Finally, Neu4 localization resembles Neu3.1, with a consistent, although less complete, co-localization with the calnexin-positive endocellular compartment (Figure 9D).

Figure 9. Subcellular localization of zebrafish sialidases Neu3.1, Neu3.2, Neu3.3 and Neu4.

COS7 cells were grown on glass coverslips, transfected with the recombinant vectors encoding the Myc-tagged zebrafish sialidases and processed for double indirect immunofluorescence. Left column: subcellular distribution of Neu3.1 (A), Neu3.2 (B), Neu3.3 (C) and Neu4 (D). Middle column: the labelling of endogenous intracellular markers such as calnexin (A and D) and LAMP1 (C), as well as the distribution of the human cytosolic sialidase NEU2 (B) detectable in a double transfection experiment. Right column: co-localization (merge) of the left and middle columns. The different primary antibodies were detected using isotype-specific secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor® 488 (green) and Alexa Fluor® 555 (red). Speciments were analysed using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope equipped with confocal laser system LSM 510 META.

DISCUSSION

In the present paper we describe the sialidase gene family in zebrafish. In mammals, four genes are known to encode sialidase enzymes with distinct subcellular localization and physiological roles [2]. In zebrafish the picture is more complex, with seven genes homologous with human sialidases. We have carried out several bioinformatic analyses to unravel the phylogenetic origin of the various members of the sialidase gene family in zebrafish. Our results indicate that a single orthologue exists for the mammalian NEU1 gene, corresponding to neu1, as also supported by the presence of partial synteny between the genomic sequences containing the orthologous genes. Similarly neu4 appears to be highly related to human NEU4, although no synteny can be detected between zebrafish and mammals. The remaining genes (neu3.1–neu3.5) are arranged in a cluster on chromosome 21 and, although with different degrees of sequence identities, they all are related to the human NEU3 gene. This finding is further supported by the conserved synteny detectable between the chromosome 21 cluster in zebrafish and the chromosome locus 11q13.4 region harbouring NEU3 in humans.

To investigate whether the redundancy of NEU3-like genes is common to other teleosts, we extended our analysis to fugu and T. nigroviridis. Interestingly, only one NEU3-like gene is present in both species, suggesting that the redundancy observed in zebrafish might be the result of an independent gene duplication event. Similar findings have been described for other duplicate genes in zebrafish [35] and other teleosts [36]. With this perspective, the gene showing the highest level of nucleotide sequence identity with fugu neu3 is zebrafish neu3.1, suggesting that it may represent the ancestor of neu3.2, neu3.3, neu3.4 and neu3.5 paralogues on the chromosome 21 cluster, and that they all originated by multiple tandem duplication events. It is intriguing to note that in fugu and T. nigroviridis only three sialidase genes exist, representing the putative orthologues of NEU1, NEU3 and NEU4, while in chicken and mammals a fourth gene, NEU2, is also present. In teleosts, a NEU2 orthologue might not be necessary or, alternatively, NEU3- and NEU4-like proteins could play the biological role of a cytosolic sialidase.

The expression of neu3.1, neu3.2, neu3.3 and neu4 genes in COS7 cells demonstrates that they encode enzymatically active sialidases. All except Neu3.2 show an extremely acidic pH optimum, with values below 3.0, which are lower than the corresponding values detectable in the higher vertebrate sialidases characterized so far [2,10–13]. On the basis of these data, Neu3.1, Neu3.3 and Neu4 behave as higher vertebrate NEU3 and NEU4 proteins, all characterized by a very low pH optimum, whereas Neu3.2, with a pH optimum of 5.6, behaves as the cytosolic sialidase NEU2. Rough cell fractionation experiments further confirm this picture, with the group of extremely acidic sialidases associated with the particulate membranous fraction whereas Neu3.2 is recovered as a soluble enzyme. Immunofluorescence localizations of the tagged zebrafish enzymes are in agreement with the subcellular fractionation data: Neu3.1 and Neu4 show a significant co-localization with the calnexin-positive cell membranes, whereas Neu3.3 localizes both at the cell surface and inner membranous structures, with only a partial co-localization with LAMP1-positive vesicles. Finally, Neu3.2 shows a distribution largely superimposable on that of the human cytosolic sialidase NEU2.

To study the possible activity of zebrafish sialidase enzymes toward ganglioside substrates inserted in the lipid bilayer of living cells, we expressed their cDNAs in [1-3H]sphingosine-labelled COS7 cells and their ganglioside content was analysed. The expression of every zebrafish Neu was studied, but Neu3.2 induces a significant decrease in GM3 and an increase in GM1 content in comparison with mock-transfected cells and, in the case of cells expressing Neu4, a significant decrease of GD1a relative content was detectable too. Similar results have been obtained in the case of the mammalian plasma membrane-associated sialidase NEU3 [6], suggesting that the overall substrate specificity, as well as the action of the enzymes in living cells, is roughly similar, despite the evolutionary distance between teleosts and mammals. These biochemical data further support the classification inferred by genomic analysis: Neu3.1 and Neu3.3 belong to the group of membrane-associated NEU3-like enzymes, whereas Neu4 belongs with NEU4-like enzymes. Rather puzzling is the biochemical behaviour of Neu3.2 that, despite its high sequence identity with mammalian NEU3 and its localization in the NEU3-like cluster on chromosome 21, it is a soluble protein with a pH optimum typical of the mammalian NEU2 cytosolic sialidases cloned so far [26,37,38]. On the other hand, as already described for mammalian membrane-associated sialidases, the hydrophobicity plot of the membrane-associated Neu3.1, Neu3.2 and Neu4 sialidases do not show any canonical hydrophobic membrane-spanning domain(s), as well as any typical amino acid motifs involved in post-translational mechanisms of anchorage to the lipid bilayer and, overall, they closely resemble Neu3.2. On the basis of these findings, Neu3.2 is more likely to be a NEU3 paralogue that has lost the ability to interact with the lipid bilayer, thus becoming a soluble enzyme.

Another intriguing aspect is the redundancy of sialidase enzymes in zebrafish compared with mammals. Interestingly, such a phenomenon appears to be confined to NEU3-like proteins only. Besides neu3.4, transcripts for NEU3-like genes are detectable, although with different time-frames during embryogenesis, as well as in adult tissues, as demonstrated by RT-PCR experiments. These results support the biological relevance of these enzymes in tissue differentiation and maintenance. In situ hybridization experiments indicate that neu3.1 and neu4 genes show temporal and spatially localized expression areas, corresponding to gut (neu3.1) and lens (neu4). The RT-PCR data on neu4 indicate that the gene transcript is present in developmental stages where no significant expression is detectable using an in situ hybridization technique. These discrepancies may be due to the limitation of the latter technique in detecting a low but ubiquitous expression pattern.

No in situ expression data are available for mammalian sialidases to date. On the basis of RT-PCR and Northern blot analysis, most members of the family, namely NEU1, NEU3 and NEU4, show quite a ubiquitous expression pattern [11–13,32,40,41] apart from NEU2, which appears to be expressed at very low levels mainly in skeletal muscle [39]. Thus, at least in the case of zebrafish neu3.1 and neu4, the expression patterns appear to be very peculiar and tissue-specific. This could be explained on the basis of the notion that duplicated or redundant genes in zebrafish are not redundant in function, but rather subdivide the function of the ancestral gene [42], or evolve new functions, particularly during development [43].

Other proteins involved in sialoglyconjugate biology have previously been described in zebrafish. Among them, the sialic acid-binding protein siglec-4 shows binding features very similar to the human orthologue [44]. In addition, putative genes encoding sialyltransfereases have been also identified in zebrafish [45]. More recently, overexpression of GM3 synthase in zebrafish embryos resulted in neuronal cell death in the central nervous system [46]. This result strongly supports the great relevance of gangliosides in the biology of fish. In addition, a glycomic survey map of zebrafish has been published, revealing unique sialylation features as well as variations during embryogenesis [47].

Overall, these studies in zebrafish suggest the presence of a complex regulation pattern for the expression of the enzymes involved in sialoglycoconjugate synthesis and degradation. In this picture, sialidases play a pivotal role in the degradation and fine regulation of these compounds [1].

The study of the different members of the sialidase gene family in this model organism represents a novel and attractive field of glycobiology. In particular, the developmental roles of sialidases can now be tested in the zebrafish using overexpression and Morpholino loss-of-function approaches. We are confident that the study of these enzymes in zebrafish will help to give a comprehensive picture of the biological roles of sialidase in vertebrates.

Online data

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by MIUR-PRIN (Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca Scientifica-Progetti di Ricerca di Interesse Nazionale) (grant 2004 and 2006) to E. M. and G. T., EUGINDAT-EC-FP-VI (EC ref: LSHM-CT-2003-502852) and FIRB “OMNIEXPRESS” (grant 2001) to G. B., Fondazione Cariplo ZEBRAGENE grant to G. B., E. M. and R. B., and EU grant ZF-Models LSH-CT-2003-503496 to F. A. and N. T. We thank Dr Melissa Haendel (University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, U.S. A.) and Dr Tina Eyre (Sanger Centre, Hinxton, Cambs., U.K.) for guidance concerning gene nomenclature assignments and Zv7 genome assembly analysis respectively.

References

- 1.Saito M. Y., Yu R. K. Biochemistry and function of sialidases. In: Rosenberg A., editor. Biology of the Sialic Acids. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 261–313. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monti E., Preti A., Venerando B., Borsani G. Recent development in mammalian sialidase molecular biology. Neurochem. Res. 2002;27:649–663. doi: 10.1023/a:1020276000901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.d'Azzo A., Andria G., Strisciuglio P., Galjaard H. Galactosialidosis. In: Scriver C. R., Beaudet A. L., Sly W. S., Valle D., editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 3811–3826. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato K., Miyagi T. Involvement of an endogenous sialidase in skeletal muscle cell differentiation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;221:826–830. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meuillet E. J., Kroes R., Yamamoto H., Warner T. G., Ferrari J., Mania-Farnell B., George D., Rebbaa A., Moskal J. R., Bremer E. G. Sialidase gene transfection enhances epidermal growth factor receptor activity in an epidermoid carcinoma cell line, A431. Cancer Res. 1999;59:234–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papini N., Anastasia L., Tringali C., Croci G., Bresciani R., Yamaguchi K., Miyagi T., Preti A., Prinetti A., Prioni S., et al. The plasma membrane-associated sialidase MmNEU3 modifies the ganglioside pattern of adjacent cells supporting its involvement in cell-to-cell interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:16989–16995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400881200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y., Yamaguchi K., Wada T., Hata K., Zhao X., Fujimoto T., Miyagi T. A close association of the ganglioside-specific sialidase Neu3 with caveolin in membrane microdomains. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:26252–26259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Da Silva J. S., Hasegawa T., Miyagi T., Dotti C. G., Abad-Rodriguez J. Asymmetric membrane ganglioside sialidase activity specifies axonal fate. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:606–615. doi: 10.1038/nn1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kakugawa Y., Wada T., Yamaguchi K., Yamanami H., Ouchi K., Sato I., Miyagi T. Up-regulation of plasma membrane-associated ganglioside sialidase (Neu3) in human colon cancer and its involvement in apoptosis suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:10718–10723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152597199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comelli E. M., Amado M., Lustig S. R., Paulson J. C. Identification and expression of Neu4, a novel murine sialidase. Gene. 2003;321:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monti E., Bassi M. T., Bresciani R., Civini S., Croci G. L., Papini N., Riboni M., Zanchetti G., Ballabio A., Preti A., et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of NEU4, the fourth member of the human sialidase gene family. Genomics. 2004;83:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaguchi K., Hata K., Koseki K., Shiozaki K., Akita H., Wada T., Moriya S., Miyagi T. Evidence for mitochondrial localization of a novel human sialidase (NEU4) Biochem. J. 2005;390:85–93. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seyrantepe V., Landry K., Trudel S., Hassan J. A., Morales C. R., Pshezhetsky A. V. Neu4, a novel human lysosomal lumen sialidase, confers normal phenotype to sialidosis and galactosialidosis cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:37021–37029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambrook J., Russell D. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marck C. ‘DNA Strider’: a ‘C’ program for the fast analysis of DNA and protein sequences on the Apple Macintosh family of computers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1829–1836. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.5.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karolchik D., Baertsch R., Diekhans M., Furey T. S., Hinrichs A., Lu Y. T., Roskin K. M., Schwartz M., Sugnet C. W., Thomas D. J., et al. The UCSC Genome Browser Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:51–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aparicio S., Chapman J., Stupka E., Putnam N., Chia J. M., Dehal P., Christoffels A., Rash S., Hoon S., Smit A., et al. Whole-genome shotgun assembly and analysis of the genome of Fugu rubripes. Science. 2002;297:1301–1310. doi: 10.1126/science.1072104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edgar R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000;17:540–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guindon S., Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westerfield M. Eugene: University of Oregon Press; 2000. The Zebrafish Book. A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thisse C., Thisse B., Schilling T. F., Postlethwait J. H. Structure of the zebrafish snail1 gene and its expression in wild-type, spadetail and no tail mutant embryos. Development. 1993;119:1203–1215. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolodkin A. L., Levengood D. V., Rowe E. G., Tai Y. T., Giger R. J., Ginty D. D. Neuropilin is a semaphorin III receptor. Cell. 1997;90:753–762. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80535-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monti E., Preti A., Nesti C., Ballabio A., Borsani G. Expression of a novel human sialidase encoded by the NEU2 gene. Glycobiology. 1999;9:1313–1321. doi: 10.1093/glycob/9.12.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tringali C., Papini N., Fusi P., Croci G., Borsani G., Preti A., Tortora P., Tettamanti G., Venerando B., Monti E. Properties of recombinant human cytosolic sialidase HsNEU2. The enzyme hydrolyzes monomerically dispersed GM1 ganglioside molecules. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:3169–3179. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308381200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook J. G., Figueroa F., Beck S. A genome-wide survey of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes and their paralogues in zebrafish. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roggentin P., Rothe B., Kaper J. B., Galen J., Lawrisuk L., Vimr E. R., Schauer R. Conserved sequences in bacterial and viral sialidases. Glycoconjugate J. 1989;6:349–353. doi: 10.1007/BF01047853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Copley R. R., Russell R. B., Ponting C. P. Sialidase-like Asp-boxes: sequence-similar structures within different protein folds. Protein Sci. 2001;10:285–292. doi: 10.1110/ps.31901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chavas L. M., Tringali C., Fusi P., Venerando B., Tettamanti G., Kato R., Monti E., Wakatsuki S. Crystal structure of the human cytosolic sialidase Neu2. Evidence for the dynamic nature of substrate recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:469–475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411506200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonten E., van der Spoel A., Fornerod M., Grosveld G., d'Azzo A. Characterization of human lysosomal neuraminidase defines the molecular basis of the metabolic storage disorder sialidosis. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3156–3169. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.24.3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guarnieri F. G., Arterburn L. M., Penno M. B., Cha Y., August J. T. The motif Tyr-X-X-hydrophobic residue mediates lysosomal membrane targeting of lysosome-associated membrane protein 1. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:1941–1946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chigorno V., Riva C., Valsecchi M., Nicolini M., Brocca P., Sonnino S. Metabolic processing of gangliosides by human fibroblasts in culture – formation and recycling of separate pools of sphingosine. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;250:661–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor J. S., Braasch I., Frickey T., Meyer A., van de Peer Y. Genome duplication, a trait shared by 22000 species of ray-finned fish. Genome Res. 2003;13:382–390. doi: 10.1101/gr.640303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson-Rechavi M., Marchand O., Escriva H., Bardet P. L., Zelus D., Hughes S., Laudet V. Euteleost fish genomes are characterized by expansion of gene families. Genome Res. 2001;11:781–788. doi: 10.1101/gr.165601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyagi T., Konno K., Emori Y., Kawasaki H., Suzuki K., Yasui A., Tsuik S. Molecular cloning and expression of cDNA encoding rat skeletal muscle cytosolic sialidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:26435–26440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrari J., Harris R., Warner T. G. Cloning and expression of a soluble sialidase from Chinese hamster ovary cells: sequence alignment similarities to bacterial sialidases. Glycobiology. 1994;4:367–373. doi: 10.1093/glycob/4.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monti E., Preti A., Rossi E., Ballabio A., Borsani G. Cloning and characterization of NEU2, a human gene homologous to rodent soluble sialidases. Genomics. 1999;57:137–143. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hasegawa T., Feijoo Carnero C., Wada T., Itoyama Y., Miyagi T. Differential expression of three sialidase genes in rat development. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;280:726–732. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monti E., Bassi M. T., Papini N., Riboni M., Manzoni M., Venerando B., Croci G., Preti A., Ballabio A., Tettamanti G., Borsani G. Identification and expression of NEU3, a novel human sialidase associated to the plasma membrane. Biochem. J. 2000;349:343–351. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Force A., Lynch M., Pickett F. B., Amores A., Yan Y. L., Postlethwait J. Preservation of duplicate genes by complementary, degenerative mutations. Genetics. 1999;151:1531–1545. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meyer A., Schartl M. Gene and genome duplications in vertebrates: the one-to-four (-to-eight in fish) rule and the evolution of novel gene functions. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1999;11:699–704. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lehmann F., Gathje H., Kelm S., Dietz F. Evolution of sialic acid-binding proteins: molecular cloning and expression of fish siglec-4. Glycobiology. 2004;14:959–968. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harduin-Lepers A., Mollicone R., Delannoy P., Oriol R. The animal sialyltransferases and sialyltransferase-related genes: a phylogenetic approach. Glycobiology. 2005;15:805–817. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwi063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sohn H., Kim Y. S., Kim H. T., Kim C. H., Cho E. W., Kang H. Y., Kim N. S., Kim C. H., Ryu S. E., Lee J. H., Ko J. H. Ganglioside GM3 is involved in neuronal cell death. FASEB J. 2006;20:1248–1250. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4911fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guerardel Y., Chang L. Y., Maes E., Huang C. J., Khoo K. H. Glycomic survey mapping of zebrafish identifies unique sialylation pattern. Glycobiology. 2006;16:244–257. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.