Abstract

A cleavage-deficient variant of NotI restriction endonuclease (GCGGCCGC) was isolated by random mutagenesis of the notIR gene. The NotI variant D160N was shown to bind DNA and protect plasmid DNA from EagI (CGGCCG) and NotI digestions. The EDTA-resistant BmrI restriction endonuclease cleaves DNA sequence ACTGGG N5/N4. The N-terminal cleavage domain of BmrI (residues 1–198) with non-specific nuclease activity was fused to the NotI variant D160N with a short linker. The engineered chimeric endonuclease (CH-endonu-clease) recognizes NotI sites specifically in the presence of high salt (100–150 mM NaCl) and divalent cations Mg++ or Ca++. In contrast to wild-type NotI, which cuts within its recognition sequence, BmrI198-NotI (D160N) cleaves DNA outside of NotI sites, resulting in deletion of the NotI site and the adjacent sequences. The fusion of the BmrI cleavage domain to cleavage-deficient variants of Type II restriction enzymes to generate novel cleavage sites will provide useful tools for DNA manipulation.

Keywords: BcgI-like enzyme, BmrI, NotI, cleavage-deficient mutant, engineered endonuclease

Introduction

Type II restriction endonucleases (REases) are a class of enzymes that occur naturally in bacteria where they serve as host defense systems, functioning to prevent infection by foreign DNA molecules such as bacteriophage and plasmids. In this defense system, foreign DNA is cleaved while host DNA is protected due to modification of the recognition sites by a cognate DNA methyltransferase. Most REases discovered to date require the divalent cation Mg++ for catalysis (Pingoud et al., 2005). Only two REases, BfiI and BmrI (5′-ACTGGG N5/N4-3′), have been shown to be EDTA resistant and do not require Mg++ for catalytic activity (Sapranauskas et al., 2000; Roberts et al., 2007). The N-terminal domain of BfiI is structurally similar to Nuc, an EDTA-resistant nuclease from Salmonella typhimurium that belongs to the phospholipase D (PLD) family (Stuckey and Dixon, 1999; Grazulis et al., 2005). The enzymes in the PLD family include phosphodiesterases, bacterial nucleases, toxins and phospholipases (Ponting and Kerr, 1996).

The substrate specificity of a Type II REase usually involves recognition of a 4–8 bp DNA sequence. Many studies have been conducted to alter the DNA recognition properties of Type II REases with limited success. Directed evolution of BstYI endonuclease (5′-RGATCY-3′) resulted in genetic selection of two BstYI variants with increased substrate specificity towards 5′-AGATCT-3′ and discrimination against 5′-GGATCC-3′ (Samuelson and Xu, 2002). Another fruitful approach is to engineer enzymes where DNA recognition is unperturbed but the cleavage site is altered. One study involved the detailed mapping of the individual FokI DNA recognition and cleavage domains. The researchers discovered that inserting 4 or 7 amino acid residues between the two domains resulted in FokI variants with altered cleavage sites compared to the WT enzyme (Li and Chandrasegaran, 1993). The co-crystal structure of FokI revealed that the FokI monomer is not active in cleavage since the catalytic domain is sequestered by the DNA recognition domain (Bitinaite et al., 1998; Wah et al., 1998). FokI forms a transient dimer by two catalytic domains on cognate DNA, which activates the catalytic center and leads to double-strand (ds) break (Bitinaite et al., 1998; Vanamee et al., 2001). When the FokI catalytic domain was coupled to a zinc finger protein, the resulting zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) could be used to introduce double-strand breaks and facilitate homologous recombination in gene correction/addition (Kim et al., 1996; Urnov et al., 2005; Dhanasekaran et al., 2006; Moehle et al., 2007). The selection and availability of modular zinc fingers with recognition sequences of any GNN, CNN, ANN and TNN triplet sequences make it possible to design ZFNs that can bind and cleave any large DNA sites of 9, 12, 15 and 18 bp (Klug, 2005; Mandell and Barbas, 2006) [US patent numbers 6785,613 (2004), 6746,838 (2004)].

Successful engineering of novel specificity from homing endonucleases has been achieved, partly due to the modular architect of the pseudodimeric feature of a LAGLIDADG endonuclease. A chimeric endonuclease E-DreI was constructed by fusing domains of homing endonucleases I-DmoI and I-CreI with a computationally redesigned and optimized domain interface. E-DreI binds to the chimeric recognition sequence with nanomolar affinity and cleaves the target DNA specifically (Chevalier et al., 2002). Variants of the homing endonuclease I-MsoI have also been redesigned and isolated by computational analysis of the base contact residues and shown to possess altered DNA sequence specificity (Ashworth et al., 2006). The pseudodimeric feature of LAGLIDADG endonuclease can be engineered to homodimeric or heterodimeric structures, resulting in novel target site recognition (Silva and Belfort, 2004; Silva et al., 2006).

In this work, we employed a cleavage-deficient NotI variant as a DNA recognition domain to create a NotI neoschizomer (an enzyme with the same recognition sequence but different cleavage site). Here, we describe the construction and characterization of a chimeric/hybrid (CH) endonuclease that cleaves outside of NotI sites and on both sides of the recognition sequence.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and plasmid substrates

The T7 expression strain ER2566 (T7 Express) and the in vivo DNA damage indicator strain ER1992 with dinD::lacZ fusion were as described (Fomenkov et al., 1994) (NEB catalog, 2007/08, page 219). The plasmid pUC-NotI with a single NotI site was provided by Samuelson et al. (2006). Plasmid pBC4 was a gift from the DNA core lab of NEB. It carries the BstBI and ClaI fragment of Adenovirus-2 (nt 10 670 to 18 657) inserted in the AccI site of pUC19 (Morgan R., NEB).

Construction of His-tagged NotI expression clone

The notIR gene with 6xHis codons was amplified in PCR from a wild-type (WT) NotI clone using two primers: 5′-GCCGGATCCGGAGGTTTAAAAATGCGTTCCGATAC-GTCTGTGGAGCCA-3′; 5′-AAGCTTGAATTCTCAGTGG-TGGTGGTGGTGGTGTGCATCGAACAGACCCCGCTGAC-CCCCTGG-3′. The PCR product flanked by BamHI and EcoRI sites was inserted into pUC19 and transferred into an M.EagI pre-modified Escherichia coli expression host. 6xHis-tagged NotI was purified from IPTG-induced cells ER2566 (pACYC-eagIM, pUC-notIR). The 6xHis-NotI encoded by pUC-notIR was used for subsequent mutagenesis studies.

Random mutagenesis of notIR and selection of cleavage-deficient variants

Hydroxylamine (HA) mutagenesis was essentially carried out as described (Xu and Schildkraut, 1991). Plasmids were treated with fresh HA for 1–2 h and the mutagenized DNA purified through Qiagen spin columns. To eliminate the methylase protection, the M.EagI plasmid was destroyed by digestion with AgeI, NaeI and SacI. The mutated plasmids were transferred into ER1992 (dinD::lacZ) competent cells and transformants plated on rich agar plates plus Amp and X-gal (80 μg/ml). White and light blue colonies were individually selected and amplified in overnight cultures. Plasmids were purified and digested with appropriate restriction enzymes to reconfirm the notIR gene insert. After DNA sequencing, variants with single amino acid (aa) substitution were selected for further catalytic and binding studies.

Construction of BmrI198 and NotI* fusion endonuclease BmrI198-NotI (D160N)

The desired notIR mutant allele encoding D160N was amplified in PCR with forward and reverse primers from a pUC clone: 5′-AAGCTTGCTAGCCATGCGTTCCGATACGTCTGTGGA-GCCA-3′; 5′-AAGCTTCGGCCGTCAGTGGTGGTGGTGGT-GGTGTGCATCGAACAGACCCCGCTGACCCC-3′. The PCR product was digested with NheI and EagI, cloned into pET21-bmrI198-[aa]14-C.BclI to replace the C gene (S.H.Chan et al., Nucl. Acids Res. (2007) doi:10.1093/nar/gkm665). A 14-aa spacer (GSGGGGSAAGASAS) lies between BmrI198 and NotI (D160N). The expression strain for the fusion endonuclease is ER2566 [pET21-bmrI198-[aa]14-notIR*-6xHis]. No protective methylase was present within the expression strain.

Protein expression, purification and refolding

One liter of E.coli ER2566 [pET21-bmrI198-[aa]14-notIR*] (the fusion protein with a C-terminal 6xHis tag) was cultured in LB supplemented with 100 μg/ml Amp at 30°C until the cell density reached OD600 0.4–0.6. IPTG-induction of BmrI198-NotI (D160N) expression was carried out at 16°C overnight. Cells expressing NotI variant D160N was induced by addition of IPTG and cultured at 37°C for 3 h. The 6xHis-tagged NotI variants D160N and BmrI198-NotI (D160N) were purified using Ni-NTA fast start kit (Qiagen) under native condition. The eluted fractions were analyzed by SDS–PAGE, collected and concentrated using an Amicon ultra-410 000 MWCO (Millipore). For short-term storage, the purified enzymes were diluted in a storage buffer (100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 0.15% Triton X-100). For long-term storage at −20°C, 50% glycerol was included in the storage buffer.

DNA protection assay

The cleavage-deficient D160N protein was pre-incubated with pUC19-NotI in NEB buffer 3 (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2) at 37°C for 20 min. The D160N-preincubated plasmid DNA was then challenged with 1 unit of EagI or NotI REase for 20 min. The digested/protected products were resolved in a 0.8% agarose gel.

Filter-binding assay

A [33P]-labeled PCR fragment (158 bp) with a single NotI site was amplified in PCR and used in the filter-binding assay. The pUC universal primers are S1233S and S1224S with the sequences: 5′-GCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGGA-3′; 5′-CGCCAGGGTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC-3′. The detailed procedure of filter binding has been described previously (Zhu et al., 2003).

DNA cleavage assay for the CH-endonuclease and run-off sequencing

The endonuclease activity of BmrI198-NotI (D160N) was determined by incubating ScaI- or EcoO109I-linearized pUC-NotI with various amount of the fusion endonuclease in a high salt buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT) supplemented with 1.2 μg non-specific duplex oligos and 0.1 mg/ml BSA unless specified otherwise. ScaI- or Eco0109I-linearized pUC-NotI plasmid was digested with BmrI198-NotI (D160N) in the high salt buffer for 1 h. The cleavage products were resolved on an agarose gel and purified using the Wizard SV gel and PCR clean-up system (Promega). DNA sequencing was conducted using the AmpliTaq dideoxy terminator kit (Applied Biosystems) and an ABI Prism™ 377 sequencer.

Results

Isolation of a binding-proficient and cleavage-deficient NotI variant

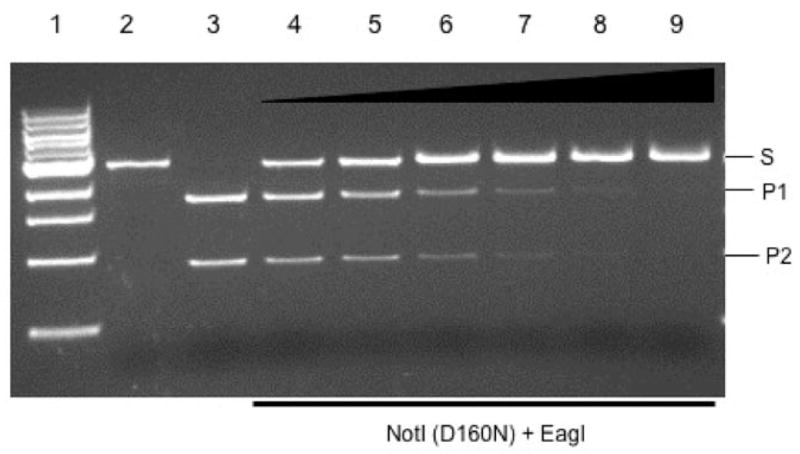

The notIR gene was randomly mutated to isolate cleavage-deficient variants. Two NotI mutants, D160N and E182K, were found to be defective in DNA cleavage as determined by activity assay using cell extracts on appropriate DNA substrates (data not shown). D160N and E182K were purified by nickel chelate chromatography and subsequently used to demonstrate protection against EagI or NotI digestion. Figure 1 displays the result of a protection assay using NotI variant D160N against EagI digestion. EagI and ScaI digestion of pUC-NotI generated two fragments (1.8 and 0.9 kb, Fig. 1, lane 3). Pre-incubation of D160N protein with ScaI-linearized pUC-NotI protected the DNA from EagI digestion (Fig. 1, lanes 4–9). D160N protein also protected linear plasmid DNA against NotI digestion (data not shown). NotI variant E182K showed weak protection of NotI sites against EagI or NotI digestion (data not shown). The purified D160N protein was used to determine DNA binding affinity in a filter-binding assay and DNA mobility shift assay. The KD of D160N was determined to be in the range of 33–40 nM (data not shown). It is concluded that D160N protein still binds DNA and protects overlapping EagI and cognate NotI site. NotI amino acid residues D160 and K182 are probably catalytic residues involved in divalent metal ion binding and catalysis. The DNA binding affinity of D160N to DNA fragments with NotI site, mis-cognate site (1 base off) or non-cognate site (>1 base off) has not been studied in detail. Preliminary binding results indicated that NotI REase and D160N have a strong binding affinity to non-specific DNA in the absence of divalent metal ions.

Fig. 1.

Protection of EagI site by D160N protein against EagI digestion. Lane 1, 1 kb DNA size marker; lane 2, ScaI-linearized DNA (2.7 kb, S); lane 3, ScaI and EagI cleavage products, 1.75 kb (P1) and 0.93 kb (P2), respectively. Lanes 4–9, 0.12 μg of ScaI-linearized plasmid DNA (pUC-NotI) pre-incubated with NotI D160N protein at 0.09, 0.18, 0.36, 0.72, 1.44 and 2.88 μM and then digested with 1 unit of EagI.

BmrI198-NotI (D160N) endonuclease

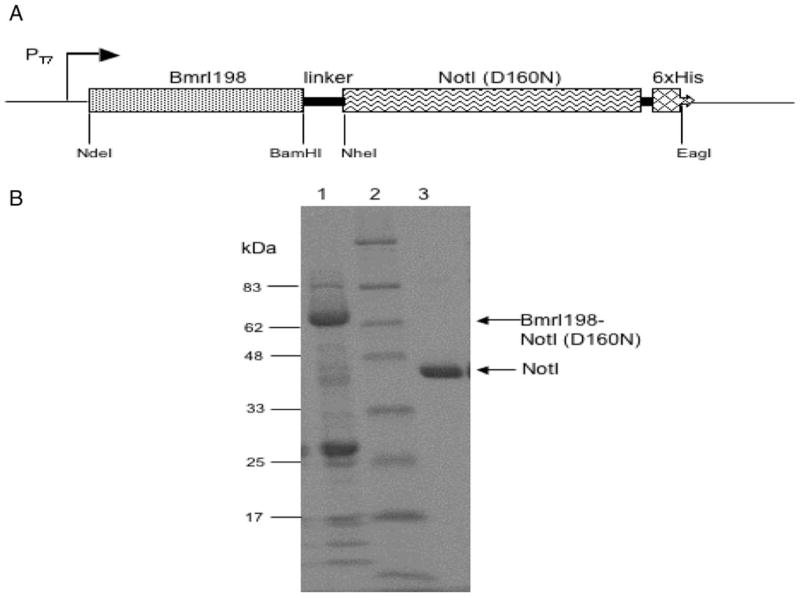

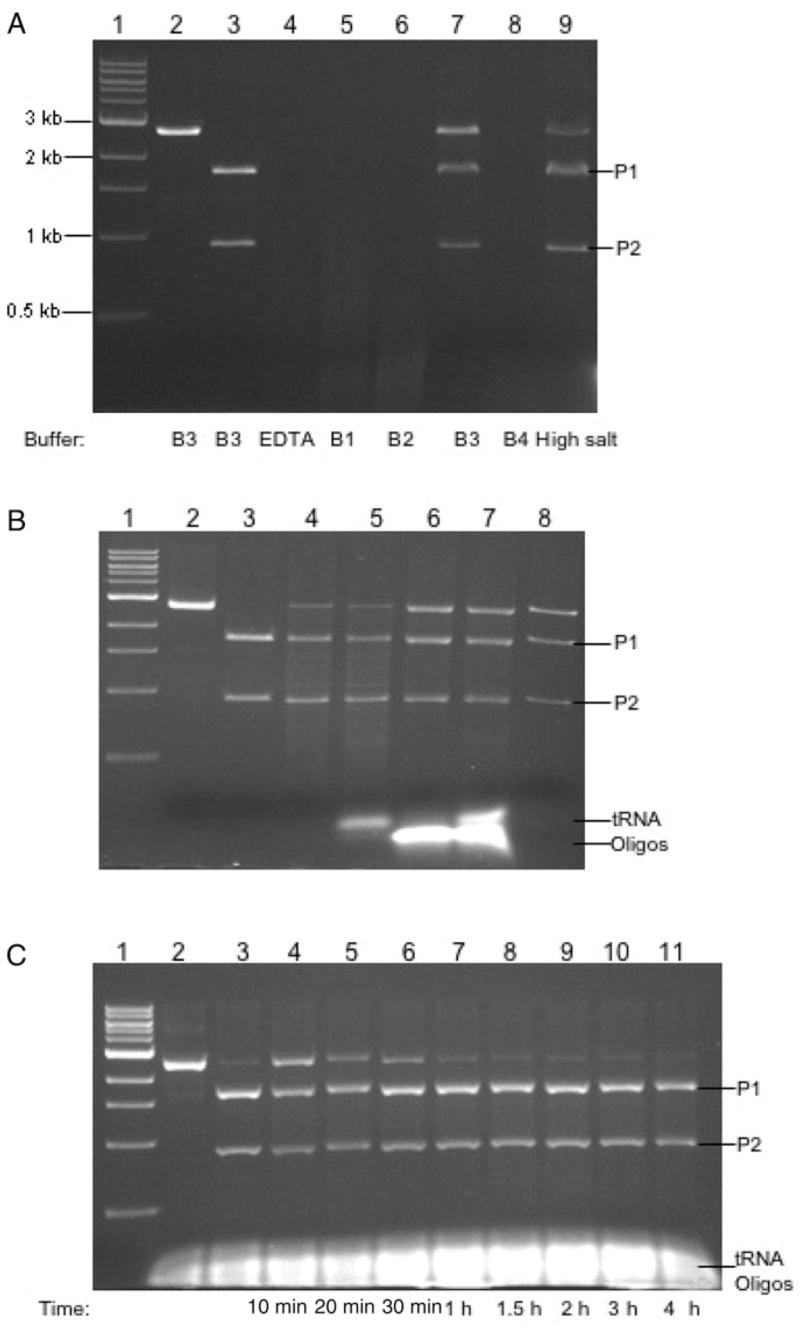

The cloning/expression of BmrI R-M system and characterization of the BmrI cleavage domain will be described elsewhere (L.Higgins et al., submitted for publication). The notIR mutant coding sequence flanked by NheI and EagI sites was cloned in pET21 to form the BmrI198-NotI (D160N) chimeric endonuclease. A linker of 14 amino acids rich in Ala, Gly and Ser was inserted between BmrI198 and NotI (D160N). Figure 2A shows the schematic diagram of the fusion construct. The linker region and the DNA-binding partner are flanked by BamHI/NheI and NheI/EagI, respectively, and can be easily replaced by other restriction fragments. The fusion protein with a 6xHis tag was purified by nickel chelate chromatography and analyzed by SDS–PAGE (Fig. 2B, lane 1). Further purification by heparin Sepharose chromatography was not successful since the fusion enzyme rapidly lost activity (data not shown). A ScaI-linearized pUC-NotI with a single NotI site was used as the substrate for endonuclease activity assay. The CH-endonuclease displays strong non-specific nuclease activity in EDTA buffer, NEB buffers 1, 2 and 4 (Fig. 3A, lanes 4, 5, 6 and 8). In buffer 3 (100 mM NaCl) and high salt buffer (150 mM NaCl), however, it generated cleavage products identical in size to that of NotI digestion (Fig. 3A, comparing lanes 7 and 9 to 3; lane 3=NotI digestion). We also attempted to reduce the non-specific cutting by addition of yeast tRNA or non-specific duplex oligos (41 bp). Figure 3B shows that addition of tRNA did not reduce the non-specific digestion (lane 5). However, adding 2 μg of duplex oligos diminished the non-specific digestion (lane 6). The combination of tRNA and duplex oligos yielded the same result as the oligos alone (lane 7). Digestion in Ca++ buffer with 150 mM NaCl also appeared to reduce the non-specific digestion (lane 8). A time course of digestion from 10 min to 4 h was carried out in a high salt buffer in the presence of excess non-specific duplex oligos (Fig. 3C). The digestion reached approximately 95% completion. Longer incubation was able to drive the digestion to completion although some non-specific fragments were also detected (data not shown). The CH-endonuclease used in Fig. 3A and B was IPTG-induced at low temperature and partially purified. Induction at the low temperature appeared to help protein folding and yield active enzyme.

Fig. 2.

(A) Schematic diagram of the fusion endonuclease construct. The BmrI nuclease coding sequence is flanked by NdeI and BamHI sites. The NotI allele is flanked by NheI and EagI sites. (B) Partially purified BmrI198-NotI (D160N) fusion endonuclease. Lane 1, partially purified fusion endonuclease (indicated by an arrow, molecular mass=~66 kDa); lane 2, protein size marker; lane 3, purified NotI endonuclease with a 6xHis tag.

Fig. 3.

(A) Digestion of linear DNA by BmrI198-NotI (D160N) in six different buffers. Lanes 1, 1 kb DNA size marker; lane 2, ScaI-linearized pUC-NotI; lane 3, NotI digestion of the linear DNA; lanes 4–9, CH-endonuclease digestion carried out in EDTA buffer, NEB buffers 1, 2, 3, 4 and high salt buffer, respectively. The enzyme to DNA molar ratio was estimated to be 12:1. (B) Digestion of linear DNA by BmrI198-NotI (D160N) in a high salt buffer supplemented with tRNA or non-specific duplex oligos. Lane 1, 1 kb DNA size marker; lane 2, ScaI-linearized pUC-NotI; lane 3, NotI digestion; lane 4, CH-endonuclease digestion; lanes 5–7, CH-endonuclease digestion in a high salt buffer supplemented with 1 μg tRNA, 2 μg duplex oligos, 1 μg tRNA/2 μg duplex oligos, respectively; lane 8, CH-endonuclease digestion in a Ca++ buffer (10 mM Ca++, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 1 mM DTT). (C) A time course of CH-endonuclease digestion in a high salt buffer supplemented with tRNA and duplex oligos. Lanes 1, ScaI-linearized plasmid DNA; lane 2, NotI digestion; lanes 3–9, a time course of 20 min to 3 h.

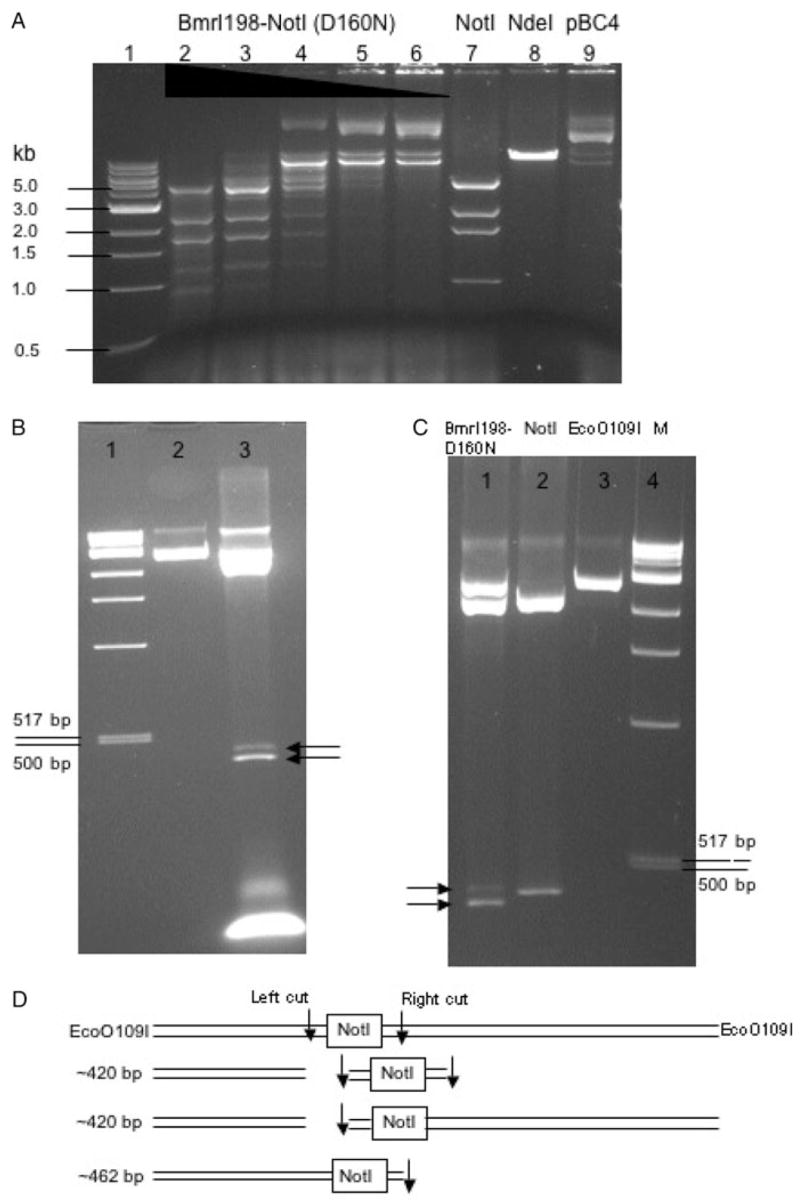

The CH-endonuclease is also active in digesting a plasmid with multiple NotI sites. Digestion of the plasmid pBC4 by the fusion endonuclease generated similar cleavage products compared to that of WT NotI digestion, although a partial fragment of 1.3 kb (954 bp + 326 bp) persisted (Fig. 4A, lanes 2–6). Although flanking sequence may play a role in cleavage efficiency, the reason for the site resistance is not clear. Digestion of λ DNA resulted in a weak cleavage product of ~4.7 kb, probably due to cleavage at a star site since NotI sites are absent in λ DNA (data not shown). The precise location of the star site has not been determined. It is known that NotI displays star activity at high enzyme or glycerol concentration (Samuelson et al., 2006). In the absence of the cognate NotI site, pUC19 was subjected to little digestion by BmrI198-NotI (D160N) under the same condition although some non-specific nicking was detected (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

(A) BmrI198-NotI (D160N) digestion of pBC4 DNA. Lane 1, 1 kb DNA size marker; lanes 2–6, DNA digested by the fusion endonuclease (expected NotI fragments: 4.9 kb, 2.6 kb, 1.9 kb, 954 bp and 326 bp); lane 7, NotI digestion; lane 8, NdeI digestion; lane 9, uncut pBC4 DNA. (B) BmrI198-NotI (D160N) digestion of pUC-NotI (prelinearized with EcoO109I). Lane 1, 1 kb DNA size marker; lane 2, EcoO109I digested pUC-NotI; lane 3, BmrI198-NotI (D160N) digestion. Arrows indicate the two closely spaced cleavage products. (C) NotI digestion of pUC-NotI (pre-linearized with EcoO109I). (D) Schematic diagram of DNA substrates and cleavage products. Down arrows indicate ds DNA breaks.

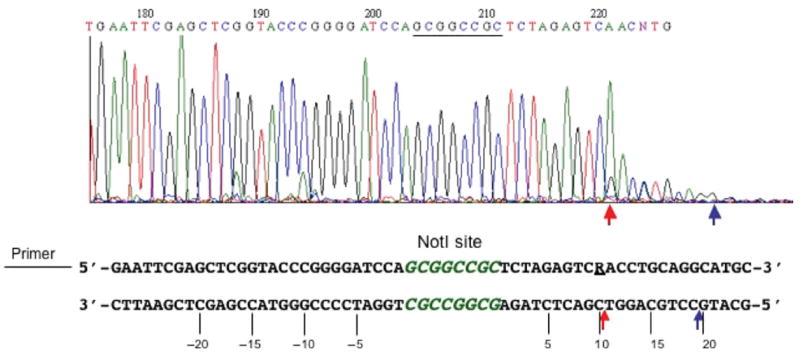

If the fusion endonuclease cleaves both sides of the NotI site, we expect that cleavage intermediates would be observed where only the left or right side is cut. Indeed, such cleavage intermediates are readily detected. Figure 4B shows that two cleavage products were generated following CH-endonuclease digestion of EcoO109I-prelinearized pUC-NotI. The smaller cleavage products correspond to DNA molecules cut on the left side, or on both sides (~420 bp). The larger cleavage product resulted from cleavage on the right side only (~462 bp). In the control experiment, NotI generated only one small fragment following EcoO109I and NotI digestion and, as expected, the size of this control fragment does not match either of the cleavage products generated by BmrI198-NotI (D160N) fusion endo-nuclease (Fig. 4C). Figure 4D shows the schematic diagram of the cleavage products after cleaving on the left side, right side or both sides by the fusion endonuclease. In order to determine the exact cut sites of the CH-endonuclease, the gel-purified large fragment (~462 bp) resulted from the right-side cut was subjected to run-off sequencing. When Taq DNA polymerase reaches the end of a DNA template, it adds an A base to the 3′ end of the extension product. Therefore, a doublet overlapping peak is indicative of a broken phosphodiester bond on the template strand. The run-off sequencing result is shown in Fig. 5. The major cuts on the bottom strand are located at nt positions 10↓11 and 19↓20 downstream of the NotI site. No cleavage was detected within the NotI site.

Fig. 5.

Run-off sequencing of gel-purified EcoO109I/CH-endonuclease digested large fragment. Arrows indicate major cut sites on the bottom strand. Nucleotides upstream of NotI site are numbered as negative (−5, −10, −15, −20 nt). Downstream sequences are numbered as 5, 10, 15 and 20 nt. R=A or G.

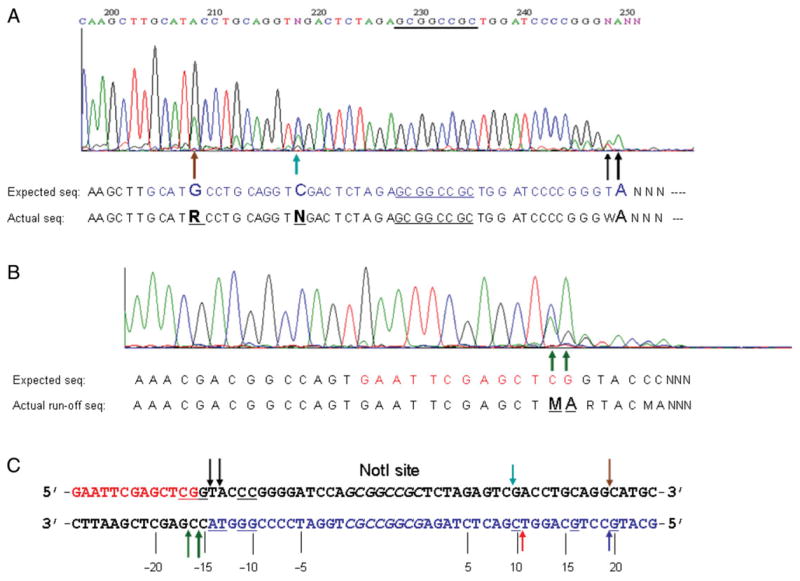

The ScaI-linearized pUC-NotI was subjected to CH-endonuclease digestion and the digested products (0.9 and 1.8 kb) were gel-purified and subjected to run-off sequencing to determine the cleavage sites on both strands. Figure 6A shows the run-off sequence from the top-strand template. The sequencing peak drops to noise level after the sequence 5′-TGGATCCCCGGGWA-3′, indicating the template strand cleavage opposite of WA (W=A or T; −15↓−14 and −14↓ −13 nt, upstream of NotI site, left-side cut). The major cuts on the top strand took place at nt positions −15↓ −14, −14↓ −13, 9↓10 and 19↓20, which spans 41-bp DNA sequence. Figure 6B shows the run-off sequence from the bottom-strand template. There are two major double peaks C/A and G/A and the sequence peaks drop significantly after the two double peaks, indicative of cleavage at −15↓ −16, or −16↓ −17 nt, upstream of the NotI site (5′-GAATTCGAGCTMA–3′, M=A or C). As expected, no DNA cleavage was detected within the NotI site on both strands. Figure 6C summarizes the cleavage pattern of the CH-endonuclease. For the top strand, the major cut is at −15↓ −14 or −14↓ −13 upstream of the NotI site (minor cuts at −12↓ −11, −11↓ −10); the cut sites on the right side of NotI site are at 9↓10 or 19↓20 nt. On the bottom strand, the major cuts at the 3′ of NotI site are at −16↓ −15 or −17↓ −16 nt. Therefore, the ds cleavage takes place outside of the NotI site, and most importantly on both sides of the NotI site, a feature that is characteristic of BcgI-like REases. The major cut on the left side generated a 1 to 3-base 3′ overhang. The major cuts on the top strand are 31 nt (14 + 8 + 9) or 41 nt apart (14 + 8 + 19), which coincides with approximately 3–4 turns of the DNA double helix.

Fig. 6.

(A) Run-off sequencing of CH-endonuclease digested DNA (template=top strand, sequencing read-out=bottom strand). Arrows indicate the double peaks (traces) with an overlapping adenine. Large and small arrows indicate major and minor cuts, respectively. Both the expected sequence and observed sequence are shown below the trace chromatogram. R=A/G double peak overlap, W=A/T double peak overlap. (B) Run-off sequencing of BmrI198-NotI (D160N) digested DNA (template=bottom strand, sequencing read-out=top strand). M=A/C double peak overlap. (C) BmrI198-NotI (D160N) cleavage site summary. Color-coded arrows are in reference to the run-off results of (A) and (B). The NotI site (GCGGCCGC) is shown in italics. Upstream sequence is numbered as negative (−5, −10, −15, −20 nt). The bases with double peaks in run-off sequencing are underlined.

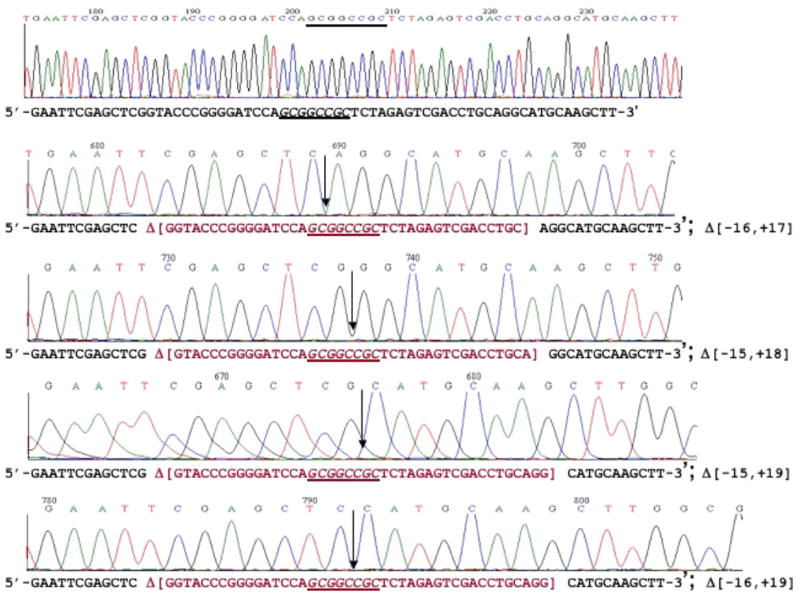

NotI site and adjacent sequence deletion following BmrI198-NotI (D160N) digestion and ligation

To further confirm the cleavage sites of BmrI198-NotI (D160N) fusion endonuclease, the circular plasmid pUC-NotI was subjected to CH-endonuclease digestion and the linear DNA was gel-purified. The ends were filled-in with Klenow fragment and the plasmid was circularized by self-ligation. Twenty-three NotI site deletion clones were identified and sequenced. Figure 7 shows the sequences of four deletion clones with 41–43 bp deletions surrounding the NotI site (the deleted sequences are shown in red). The truncation among most of the deletion clones (18 clones) on the left side occurred at nt positions −15 or −16, which is consistent with the major cut sites determined by run-off sequencing. Two deletions took place at nt position −9 and one deletion at −10, respectively. Two deletion clones suffered large sporadic deletions (data not shown). The deletion junctions on the right side of NotI site were more heterogeneous. Seven deletion clones carried DNA deletions up to nt positions 10 or 11; nine deletions clones contained DNA deletions up to nt position 19 or 20. Five deletion clones deleted DNA up to nt positions 16, 17 or 18. Two clones suffered a large deletion (data not shown). Overall, it was demonstrated that the CH-endonuclease could be used to construct deletion variants surrounding a NotI site.

Fig. 7.

DNA sequence of NotI deletion clones. Top sequence is the WT sequence with a NotI site (starting plasmid). The rest are sequences of four deletion clones. The deleted sequences are shown in red in brackets [ ]. Down arrows indicate the ligation junction after deletion. The NotI site (GCGGCCGC) is shown in italics.

Temperature optimum and sensitivity to 5mC modification

The BmrI198-NotI (D160N) endonuclease is active at 25–50°C. It is most active at 37–42°C. High temperature at 65°C inactivated the enzyme (data not shown). Like the WT NotI REase, the CH-endonuclease is sensitive to 5mC modification. Plasmid DNA (pUC-NotI) was resistant to digestion by BmrI198-NotI (D160N) endonuclease when the plasmid was pre-modified by M.EagI (data not shown). M.EagI may modify the fourth or fifth nt in the target sequence 5′-CGGCCG-3′ since hemi-methylated duplex oligos containing 5mC modification at the fourth or fifth position blocks EagI digestion (Roberts et al., 2007).

Discussion

BmrI is a Type IIS REase that cleaves N5/N4 downstream of its recognition sequence. Similarly to its extensively studied isoschizomer BfiI, BmrI is an EDTA-resistant endonuclease that contains two distinct functional domains. The N-terminal domain BmrI198 was expressed in E.coli and shown to possess non-specific nuclease activity. BmrI198 was fused to a NotI cleavage-deficient variant (D160N) in this work. The fusion created an artificial endonuclease that binds to NotI sites and cleaves on both side of the recognition sequence. Cleavage on both sides of the recognition sequence is a characteristic of BcgI-like enzymes, which include Type IIG REases AloI, BcgI, BaeI, BplI, CjeI, CspCI, HaeIV, PpiI and TstI (Roberts et al., 2007).

The catalytically important residues Asp160 and Glu182 of NotI REase are located in the amino acid sequence FD160(aa)21E182IQ184, which was predicted previously to be a potential catalytic site (Samuelson et al., 2006). The isolation of cleavage-deficient variants at Asp160 and Glu182 positions strongly supports that prediction. The NotI:DNA cocrystal structure revealed that Asp160 and Glu182 residues may be part of a catalytic site involved in divalent metal ion binding and DNA hydrolysis (B.Stoddard, personal communication). NotI forms a dimer in gel filtration studies (Sznyter and Brooks, 1988). It was expected that the BmrI198-NotI (D160N) dimer would bind to the symmetric NotI site. The formation of cleavage intermediate of closely spaced doublet bands seems to support the mechanism that the cut upstream or downstream may be introduced by separate binding events of two dimers (we cannot completely rule out the possibility that cuts on both sides are introduced by 2× dimers). The major cuts on the top strand are approximately 31 or 41 nt apart, which would lie on the same face of the DNA 3–4 helical turns adjacent to the recognition site. The staggered cuts introduced by the CH-endonuclease still lack precision. This variable nature may be further improved by the variation of the spacer between NotI (D160N) and BmrI nuclease domain. The BmrI cleavage domain BmrI198 has also been fused to a DNA-binding protein C.BclI whose recognition sequence consists of 12-bp inverted sequence (C-box). BmrI198-C.BclI cleaves DNA specifically under appropriate conditions (S.H.Chan et al., Nucl. Acids Res. (2007) doi:10.1093/nar/gkm665). The BmrI nuclease domain can also be fused to other DNA-binding proteins to probe detailed DNA and protein interactions.

The fusion of FokI catalytic domain to various zinc fingers created ZFNs with the potential to bind and cut any DNA sequence provided that multiple fingers are linked together by modular construction. Such ZFNs have been successfully used to introduce double-strand breaks in DNA and facilitate homologous recombination in gene targeting in plant and mammalian cells (Urnov et al., 2005; Wright et al., 2005). Other artificial endonucleases have also been constructed by fusing DNA-binding protein with peptides that can bind to various divalent transition metal ions or organic complexes by formation of a hydrolytic or redox active site. These artificial endonucleases are capable of nicking or creating ds breaks in DNA (US patent no. 7091,026) (Ebright et al., 1990). However, the oxidative cleavage creates 5′ and 3′ nucleotides that are not the suitable substrates for T4 or E.coli DNA ligases, which cast limitations in molecular biology applications.

There are only a few known Type IIG REases that cut outside and on both sides of the recognition sequences. The example of fusing a cleavage-deficient NotI variant to the BmrI cleavage domain demonstrates the potential of such enzymes for generating recombinant DNA or cDNA expression profiling such as SAGE (Matsumura et al., 2003). In SAGE, the length of the ligated ditag depends on how far a Type IIS REase can reach downstream. It is now possible to construct chimeric Type IIS enzymes that reach farther than natural occurring REases. For example, the MmeI REase recognizes the 5′-TCCRAC-3′ sequence and cleaves 20/18 bases downstream. A binding-proficient and cleavage-deficient MmeI variant can be readily isolated and fused to the BmrI cleavage domain. Such chimeric enzyme may cleave DNA farther downstream than WT MmeI. We and others have also cloned BceAI (ACGGC N12/N14), BbvI (GCAGC N8/N12), BscGI (CCCGT N?/N?), FauI (CCCGC N4/N6) and many other Type IIS REases (Roberts et al., 2007; C. Nkenfou et al., unpublished results). DNA cleavage domains with desired properties can be derived from these REases. For future improvement of engineered endonucleases, a built-in triggering/activation mechanism will be a desired feature to reduce toxicity in vivo.

Cleavage site variation has also been observed with natural occurring Type IIG and Type IIS REases. For example, CspCI cut sites can be varied from N10 to N11 at the 5′ cut and from N12 to N13 at the 3′ cut depending on the adjacent sequence contexts (5′-N10–11 CAAN5GTGGN12–13) (D. Heiter and G. Wilson, unpublished results). Understanding cleavage site variations can not only provide important information on DNA and protein interactions, but also yield clues for improvement of existing REases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Roberts and Siuhong Chan for critical reading of the manuscript, Jim Samuelson, Elisabeth Raleigh, and Rick Morgan for providing strains and plasmids. We thank NEB Organic Synthesis Division for providing oligos and DNA sequencing lab for run-off sequencing. We thank Don Comb for support and encouragement. The sequence of BmrI R-M system has been deposited in Genbank with accession number EF143916.

Funding

New England Biolabs, Inc. National Institute of Health (SBIR grant 1R43 GM073345-01 to S.Y.X.).

Abbreviations

- BmrI198

N-terminus domain including amino acids 1 to 198

- CH-endonuclease

chimeric/hybrid endonuclease

- ds

double strand

- notIR

NotI restriction gene

- REase

restriction endonuclease

- R-M

restriction modification system

- ZFN

zinc finger nuclease

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/uk/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- Ashworth J, Havranek JJ, Duarte CM, Sussman D, Monnat RJ, Jr, Stoddard BL, Baker D. Nature. 2006;441:656–659. doi: 10.1038/nature04818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitinaite J, Wah DA, Aggarwal AK, Schildkraut I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10570–10575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier BS, Kortemme T, Chadsey MS, Baker D, Monnat RJ, Stoddard BL. Mol Cell. 2002;10:895–905. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00690-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanasekaran M, Negi S, Sugiura Y. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:45–52. doi: 10.1021/ar050158u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebright RH, Ebright YW, Pendergrast PS, Gunasekera A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2882–2886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.8.2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomenkov A, Dila D, Raleigh EA, Xu Y. Nucl Acids Res. 1994;22:2399–2403. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.12.2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grazulis S, Manakova E, Roessle M, Bochtler M, Tamulaitiene G, Huber R, Siksnys V. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15797–15802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507949102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YG, Cha J, Chandrasegaran S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1156–1160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klug A. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:892–894. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Chandrasegaran S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2764–2768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell JG, Barbas CF., 3rd Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W516–W523. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura H, Reich S, Ito A, Saitoh H, Kamoun S, Winter P, Kahl G, Reuter M, Kruger DH, Terauchi R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15718–15723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536670100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moehle EA, Rock JM, Lee YL, Jouvenot Y, DeKelver RC, Gregory PD, Urnov FD, Holmes MC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3055–3060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611478104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pingoud A, Fuxreiter M, Pingoud V, Wende W. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:685–707. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4513-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponting CP, Kerr ID. Protein Sci. 1996;5:914–922. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R, Vincze T, Posfai J, Macelis D. Nucl Acids Res. 2007;35:269–270. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson JC, Morgan RD, Benner JS, Claus TE, Packard SL, Xu SY. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:796–805. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson JC, Xu SY. J Mol Biol. 2002;319:673–683. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00343-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapranauskas R, Sasnauskas G, Lagunavicius A, Vilkaitis G, Lubys A, Siksnys V. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30878–30885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003350200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva GH, Belfort M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:3156–3168. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva GH, Belfort M, Wende W, Pingoud A. J Mol Biol. 2006;361:744–754. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.063. Epub 2006 Jul 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey JA, Dixon JE. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:278–284. doi: 10.1038/6716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sznyter LA, Brooks JE. Heredity. 1988;61:308. [Google Scholar]

- Urnov FD, Miller JC, Lee YL, Beausejour CM, Rock JM, Augustus S, Jamieson AC, Porteus MH, Gregory PD, Holmes MC. Nature. 2005;435:646–651. doi: 10.1038/nature03556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanamee ES, Santagata S, Aggarwal AK. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:69–78. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wah DA, Bitinaite J, Schildkraut I, Aggarwal AK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10564–10569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright DA, Townsend JA, Winfrey RJ, Jr, Irwin PA, Rajagopal J, Lonosky PM, Hall BD, Jondle MD, Voytas DF. Plant J. 2005;44:693–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu SY, Schildkraut I. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4425–4429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Zhou J, Friedman AM, Xu SY. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:359–372. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00595-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]