Abstract

To search for submolecular protein foldon units, the spontaneous reversible unfolding and refolding of staphylococcal nuclease (SNase) under native conditions was studied by a kinetic native state hydrogen exchange (NHX) method. As for other proteins, it appears that SNase is designed as an assembly of well-integrated foldon units that may define steps in its folding pathway and may regulate some other functional properties. The HX results identify 34 amide hydrogens that exchange with solvent hydrogens under native conditions by way of large transient unfolding reactions. The HX data for each hydrogen measures the equilibrium stability (ΔGHX) and the kinetic unfolding and refolding rates (kop and kcl) of the unfolding reaction that exposes it to exchange. These parameters separate the 34 identified residues into three distinct HX groupings. Two correspond to clearly defined structural units in the native protein, termed the blue and red foldons. The remaining HX grouping contains residues, not well separated by their HX parameters alone, that represent two other distinct structural units in the native protein, termed the green and yellow foldons. Among these four sets, a last unfolding foldon (blue) unfolds with rate constant of 6x10−6 s−1 and free energy equal to the protein’s global stability (10.0 kcal/mol). It represents part of the β-barrel including mutually H-bonding residues in the β4 and β5 strands, a part of the β3 strand that H-bonds to β5, and residues at the N-terminus of theα2 helix which is capped by β5. A second foldon (green), which unfolds and refolds more rapidly and at slightly lower free energy, includes residues that define the rest of the native α2 helix and its C-terminal cap. A third foldon (yellow) defines the mutually H-bonded β1-β2-β3 meander, completing the native β-barrel, plus an adjacent part of the α1 helix. A final foldon (red) includes residues on remaining segments that are distant in sequence but nearly adjacent in the native protein. Although structure of the partially unfolded forms (PUFs) closely mimics the native organization, four residues indicate the presence of some non-native misfolding interactions. Because the unfolding parameters of many other residues are not determined it seems likely that the concerted foldon units are more extensive than is shown by the 34 residues actually observed.

Keywords: Staphylococcal nuclease, protein folding, foldons, hydrogen exchange, kinetic native state hydrogen exchange

Introduction

Studies of the protein folding process have serendipitously revealed a new dimension of protein structure.1–3 It appears that proteins are made up of a small number of cooperative structural units, called foldons, that can be seen to experience repeated unfolding and refolding reactions even under native conditions, albeit at an exceedingly low level. Submolecular foldon units have now been demonstrated in many proteins by site-resolved hydrogen exchange (HX),2,4–22 by a related thiol reactivity method,23 by NMR relaxation dispersion,24 and by theoretical analysis.25,26 These results support the generality of the foldon phenomenon. Foldon structure and interactions are interesting in respect to protein stability, cooperativity, dynamics, and design, possibly even for protein evolution, and they have clear functional implications. The stepwise formation and assembly of native-like foldon units appears to account for the steps in folding pathways that carry unfolded polypeptides to their native folded state.4 Having reached the native state, reversible foldon unfolding occurs repeatedly and can control functionally important structure change equilibria and site exposure rates.27,28

One wants to understand the determinants of these fundamental units of protein structure and folding and their behavior. The first implication for the existence of foldons and their possible functional significance came from the hydrogen exchange (HX) pulse labeling method, which was developed to study the structure of kinetic folding intermediates.13,29–31 This experiment, repeated for many proteins, has usually found intermediates that contain partial native-like structure. However, the experiment is limited to the study of well populated kinetic intermediates. Most folding intermediates occur after the rate-limiting step and are invisible to all kinetically-based observations.

Further progress came with the realization that native protein molecules repeatedly unfold and refold, in whole and in part, and continually re-explore all of the structural forms in their high free energy landscape.1,2 In principle, folding intermediates might then be studied over long time periods, whether they accumulate during kinetic folding or not. The problem is that this low level unfolding – refolding behavior is invisible to most methods which are dominated by signals from the overwhelmingly populated native state. Fortunately the opposite is true for HX measurements. HX rates measured for stably protected hydrogens receive no contribution from the predominant native state but are wholly determined by the cycling of protein molecules through their higher free energy states. The HX study of transient unfolding reactions can in favorable cases detect the major components of the high free energy landscape, determine their structure, measure their equilibrium stability and their kinetic unfolding and refolding rates, and evaluate their significance for functional properties including protein folding pathways.4

The experiment most used for these purposes, called equilibrium native state HX (NHX),1,2,32 attempts to amplify the equilibrium population of high free energy partially unfolded forms (PUFs) so that they come to dominate the HX behavior that one measures. The different PUFs may then be distinguished by their different free energy levels and identified by the sets of amide hydrogens that they protect and expose. A more discriminating separation can be provided by a related approach called kinetic NHX12 which attempts to distinguish different unfolded forms by their unfolding rates rather than their population levels. This method exploits high pH conditions that tend to drive HX that is mediated by large unfolding reactions to the so-called EX1 limit. Here the measured HX rate of individual hydrogens becomes equal to the rate of the transient structural unfolding reaction that exposes them to exchange.31,33–35 The experiment, when successful, can measure both equilibrium stability and kinetic opening rates at many sites and thus provides a two-parameter separation of different unfolding reactions.

The present work extends these investigations to the much studied folding model staphylococcal nuclease (SNase), a member of the large OB fold family of proteins.36 SNase is a 149-residue mixed α/β protein with three α-helices (α1 to α3), a major five stranded β-barrel (β1 to β5), and three minor β-strands.37 In an earlier search for foldon units, Wrabl38 studied SNase by the equilibrium NHX method and found that many amide hydrogens naturally exchange by way of large unfolding reactions that approach the global unfolding in free energy. As is often found, the various nearly global hydrogens displayed a spread of free energies that made it difficult to distinguish separate foldon units. This paper describes a search for foldon units in SNase by use of the kinetic NHX method.

Results

Equilibrium stability from denaturant melting

The search for foldon units by native state HX generally requires that protein stability should be rather high, perhaps 9 kcal/mol or more, in order to provide a large dynamic range within which subglobal unfolding reactions might be separated and characterized.2 We used a stabilized double mutant of SNase, P117G/H124L.39 Equilibrium melting experiments indicate that each mutation increases SNase stability about equally (ΔCm = 0.68 M GdmCl at pH 8, 20°C) and the double mutant adds the separate effects. Structure changes due to these mutations are very local39,40 and the protein retains full activity.39

Most biophysical studies of SNase have been done below neutral pH. However, HX experiments designed to reach limiting EX1 behavior require a high pH condition where the chemical exchange of exposed amide hydrogens becomes faster than the rate for reclosing of the structural unfolding reactions that expose the hydrogens to exchange (kch > kcl, Equation 2). We measured the equilibrium unfolding of SNase from pH 6.5 to 10 by fluorescence and far ultraviolet CD (Figure 1(a)). When analyzed by the linear extrapolation method,41 the two spectroscopic probes show that stability is constant from pH 6.5 through 9.5 and decreases at higher pH (Figure 1(b)). However this analysis underestimates the true stability because SNase melting is not 2-state (see HX analysis below)

Figure 1.

Equilibrium properties of SNase P117G/H124L measured by fluorescence (■) and CD222 (●). (a) Urea unfolding at pH 8. (b) Stability as a function of pH obtained from urea melts by the linear extrapolation method, which shows the pH-dependence but underestimates true stability because SNase melting is not 2-state. (c) SNase denaturation by high pH.

Figure 1(c) reveals another issue. Fluorescence and CD222 amplitudes decrease above pH 8. The single fluorescence probe, Trp140, and the α3 helix are near the protein C-terminus. HSQC spectra show that crosspeaks moving in from the C-terminus (residues 149 - 143) and from the N-terminus (residues 2–7) broaden and disappear when pH is raised above 6 (data not shown). These pH-dependent effects change the amplitude of measured equilibrium melting curves but not their midpoint and slope or the extrapolated global stability until pH 10 when the onset of instability becomes apparent.

Kinetic NHX in pulse labeling mode

The kinetic NHX approach attempts to distinguish foldon units by virtue of their different unfolding rates as they repeatedly unfold and refold under native conditions. At relatively high pH, HX rates can become equal to the rate of structural unfolding reactions (EX1 mode), which occurs when the unprotected chemical exchange rate is made faster than the rate for structural refolding. For example, at pH 10 and 20°C, the average unprotected amide HX rate is about 104 s−1. Only large unfoldings that refold more slowly than 100 μsec can then produce EX1 behavior (Equation 4).

An initial search for EX1 behavior was done in the conventional pulse labeling mode12,42 by mixing deuterium-exchanged native protein into H2O at high pH for short labeling times (75 msec to 3 hours). At pH 8 and 10 the exchange of most protons was either too slow to measure or remained in the EX2 mode. At pH 11.5 SNase unfolds non-reversibly with a time constant of 30 sec. The hydrogens that would otherwise exchange more slowly than 30 sec are then seen to exchange in an apparent EX1 manner, all with the same 30 sec time constant. These results do not provide the kind of detailed structural and kinetic information necessary to identify and characterize SNase foldons.

Kinetic NHX in real time mode

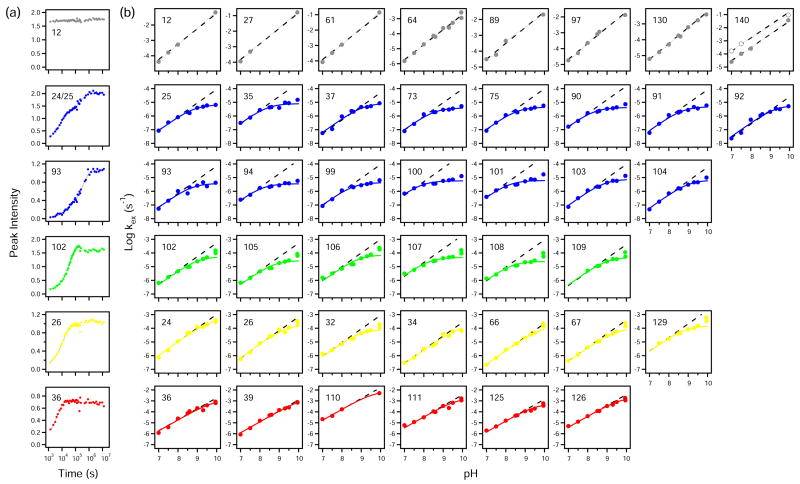

The very slowly exchanging hydrogens of SNase can be directly measured in real time, from hours to months, at pH conditions where the protein is stable. We first assigned NMR crosspeaks at pH 6.5 to 10 using 3D NMR methods. D to H exchange was then measured in H2O solutions at nine pH values from 7 to 10 by recording consecutive HSQC spectra in time. Accurate exchange rates and their dependence on pH were obtained for 75 individual amides and one tryptophan indole proton. Figure 2(a) illustrates HX data measured at pH 9.0 for some individual residues. Each HX time course is accurately fit by a monoexponential decay or by a biexponential when crosspeaks overlap (for example 24/25). When necessary, overlapping crosspeaks were identified by triple resonance NMR after the faster hydrogen was largely eliminated by H to D exchange.

Figure 2.

Kinetic NHX results. (a) Illustrative D to H exchange data measured at pH 9.0. Time-dependent crosspeak amplitudes, fit to one or two exponentials, are normalized to a reference amplitude taken as the average of ten fully protonated crosspeaks in the same HSQC spectrum, and need not equal unity. (b) HX rates vs. pH. Dashed lines show the unit slope of EX2 HX. Continuous lines are fit by Equation 2 for an EX2 to EX1 transition. Residues placed in each foldon unit (see Figure 4) are in color. The participation in foldon unfolding reactions cannot be determined for sites that remain in EX2 mode (examples shown in gray) or were not measured. The double data points at pH 10 (pulse and continuous HX modes), systematically high due to decreased stability (see Figure 1), were used to fit the red curves due to the paucity of other data points but not the blue, green and yellow data. The Trp140 panel shows both the amide (●) and indole (○) NH.

The HX rates of 41 of the 75 amide hydrogens measured remain in the EX2 mode over the pH range studied, continuing to increase by a factor of 10 per pH unit due to catalysis by OH−- ion. Examples are shown in the first line of Figure 2(b). These hydrogens exchange by way of opening reactions, probably local fluctuational events,43 that are able to reclose more rapidly than the chemical exchange rate (kcl > kch), even at pH 10 where kch~104 s−1. The same residues undoubtedly also participate in larger foldon unfolding reactions but this is obscured by their failure to adopt EX1 behavior.

In fortunate contrast, the HX behavior of the other 34 amide hydrogens in Figure 2(b) are seen to transit from EX2 to EX1 behavior (Equations 2–4). EX1 behavior (Equation 4) distinguishes large unfolding reactions because only large unfoldings are able to have such slow reclosing rates (listed in Table 1). Local fluctuational openings are able to reclose very fast, measured to be faster than microseconds,44 and so will maintain EX2 behavior even up to pH 12. Solvent penetration mechanisms would not show EX1 behavior. The other possible explanation for the rollover in rate at high pH would be that exchange remains in the EX2 mode and the slowed HX rate is due to an increase in stability. This possibility is dispelled by the observation that stability decreases above pH 9.5 (Figure 1(b)). A decrease in stability can cause HX rates to go faster but not slower. Finally, many of these same residues were measured in the equilibrium NHX experiment of Wrabl38 and seen to exchange with the high dependence on denaturant (high m values) characteristic of large unfolding reactions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Foldon Parameters

| Residue | kop (s−1)a | kcl (s−1)a | ΔGHX (kcal/mol)b | Rollover pHc | m (kcal/mol M−1)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Foldon | (10−6)e | ||||

| 25 | 7.3±0.5 | 260±30 | 10.1±0.1 | 9.0±0.1 | −3.8±0.2 |

| 35 | 8.4±0.4 | 350±30 | 10.2±0.1 | 8.5±0.1 | n/a |

| 37 | 8.3±0.5 | 220±20 | 10.0±0.1 | 9.2±0.1 | −4.0±0.2 |

| 73 | 3.9±0.1 | 60±3 | 9.6±0.1 | 8.6±0.1 | −4.6±0.3 |

| 75 | 4.6±0.1 | 81±4 | 9.7±0.1 | 8.6±0.1 | n/a |

| 90 | 4.3±0.1 | 132±6 | 10.0±0.1 | 8.4±0.1 | −4.5±0.2 |

| 91 | 4.5±0.2 | 270±20 | 10.4±0.1 | 8.8±0.1 | −4.6±0.1 |

| 92 | 6.4±0.5 | 460±40 | 10.5±0.1 | 9.4±0.1 | n/a |

| 93 | 3.3±0.2 | 140±10 | 10.2±0.1 | 8.7±0.1 | −4.0±0.9 |

| 94 | 3.6±0.1 | 160±9 | 10.2±0.1 | 8.2±0.1 | −5.2±0.1 |

| 99 | 4.4±0.2 | 101±8 | 9.9±0.1 | 8.7±0.1 | −4.1±0.2 |

| 100 | 6.4±0.2 | 190±10 | 10.0±0.1 | 8.0±0.1 | −4.7±0.3 |

| 101 | 6.2±0.2 | 100±7 | 9.7±0.1 | 8.3±0.1 | −4.7±0.3 |

| 103 | 7.7±0.3 | 190±10 | 9.9±0.1 | 8.9±0.1 | n/a |

| 104 | 6.4±0.2 | 120±6 | 9.7±0.1 | 9.1±0.1 | −4.3±0.2 |

| Avg | 5.7±1.7 | 180±120 | 10.0±0.3 | 8.7±0.4 | −4.4±0.4 |

| Green Foldon | (10−5)e | ||||

| 102 | 5.8±0.2 | 800±50 | 9.6±0.1 | 9.1±0.1 | n/a |

| 105 | 2.9±0.1 | 430±30 | 9.6±0.1 | 8.8±0.1 | n/a |

| 106 | 12.1±0.6 | 3300±200 | 10.0±0.1 | 9.3±0.1 | −4.7±0.2 |

| 107 | 5.3±0.1 | 720±30 | 9.6±0.1 | 8.5±0.1 | −5.2±0.3 |

| 108 | 2.6±0.09 | 96±6 | 8.8±0.1 | 8.5±0.1 | −4.9±0.2 |

| 109 | 4.6±0.2 | 510±60 | 9.4±0.1 | 9.0±0.5 | −4.1±0.3 |

| Avg | 5.5±3.5 | 1000±1200 | 9.5±0.4 | 8.9±0.3 | −4.7±0.5 |

| Yellow Foldon | (10−4)e | ||||

| 24 | 4.7±0.8 | 2400±500 | 9.0±0.2 | 9.6±0.1 | −4.0±0.2 |

| 26 | 2.3±0.1 | 1800±100 | 9.3±0.1 | 9.6±0.1 | −3.9±0.1 |

| 32 | 1.0±0.02 | 600±20 | 9.1±0.1 | 9.1±0.1 | n/a |

| 34 | 1.3±0.3 | 4000±1000 | 10.0±0.3 | 9.7±0.1 | −4.3±0.1 |

| 66 | 1.3±0.2 | 1200±200 | 9.3±0.2 | 9.7±0.1 | −4.1±0.3 |

| 67 | 1.0±0.1 | 510±50 | 9.0±0.1 | 9.4±0.1 | −3.9±0.2 |

| 129 | 1.9±0.1 | 610±60 | 8.7±0.1 | 9.1±0.1 | n/a |

| Avg | 1.9±1.3 | 1600±1300 | 9.2±0.4 | 9.5±0.3 | −4.0±0.2 |

| Red Foldon | (10−3)e | ||||

| 36 | 2.6±0.7 | 7000±2000 | 8.6±0.3 | 10.3±0.1 | n/a |

| 39 | 3.6±0.5 | 3400±500 | 8.0±0.2 | 10.5±0.1 | −2.6±0.2 |

| 110 | 8±3 | 4000±2000 | 7.6±0.5 | 9.7±0.2 | n/a |

| 111 | 1.6±0.2 | 940±140 | 7.7±0.2 | 9.6±0.1 | n/a |

| 125 | 0.4±0.02 | 330±20 | 8.0±0.1 | 9.4±0.1 | n/a |

| 126 | 2.8±0.3 | 4400±500 | 8.3±0.1 | 9.9±0.1 | −5.2±0.5 |

| Avg | 3.2±2.6 | 3300±2400 | 8.0±0.4 | 9.9±0.4 | −4±2 |

Obtained by fitting the kinetic NHX data in Figure 2 using Equation 2 (20°C in H2O with 50 mM buffer and 0.1 M KCl at pH 7.0 to 9.5). kop is the rate for foldon unfolding starting from the predominant native state. kcl is the rate for reprotecting the hydrogens exposed in the partially unfolded form.

ΔGHX = −RTln(Kop) = −RTln(kop/kcl)

pH at which kcl = kch.

Calculated from equilibrium NHX data for SNase PHS at 25°C in D2O with 50 mM sodium acetate and 100 mM NaCl at pHread 5.0 (personal communication and 38).

Multiplication factor for all kop values within a foldon

Data analysis

The colored curves in Figure 2(b) fit the HX data to Equation 2 which describes the transition from EX2 to EX1 exchange at high pH. EX2 exchange is seen at the lower pH values where HX rate increases in proportion to catalyst OH− concentration (unit slope shown by dashed line). EX1 behavior appears at higher pH where the HX rate limits at the opening rate for the transient unfolding reaction that exposes each hydrogen to exchange (Equation 4).

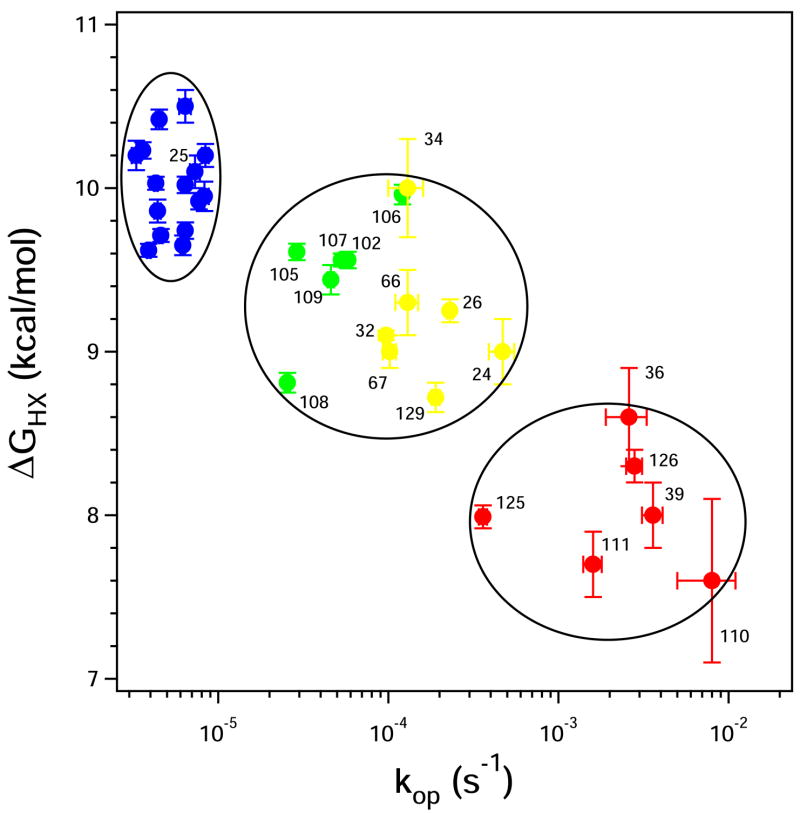

Figure 3 and Table 1 show the ΔGHX and kop values obtained in this way for each residue. The results exhibit a general correlation between stability (ΔGHX) and unfolding rate (kop), as can be expected. More specifically, one wants to know how the measured HX parameters relate to dynamic structural unfolding events in the native protein. One suggestion is that the HX data might reflect some progressive fraying of protecting structure. Comparison with the SNase structure (Figure 4) provides no reasonable basis for this scenario.

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional scatter plot separation of foldon units. ΔGHX and kop are the values measured from the fitted data in Figure 2. The groupings shown are indicated visually, by formal cluster analysis, and by the placement of the amino acid residues in the native protein.

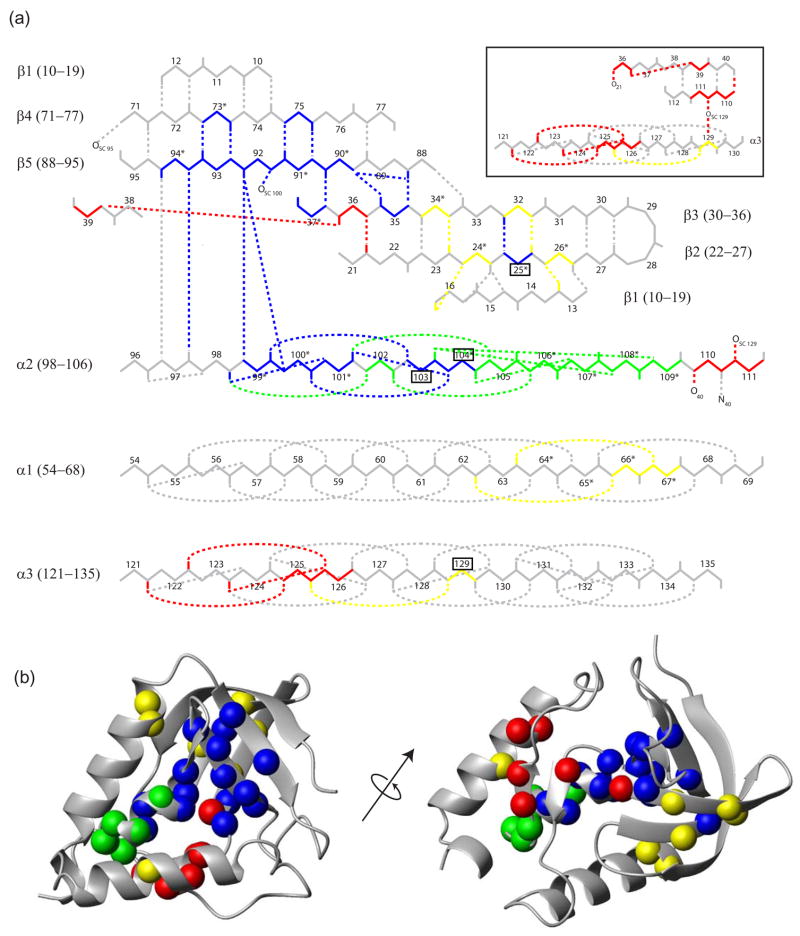

Figure 4.

Placement in the native structure of the amides measured in each color-coded foldon. (a) Foldon positions within the native SNase H-bonding pattern. Each residue carbonyl is indicated by a bar. The apparently misprotected residues (25, 129, 103, and 104) which assume non-native protection within partially unfolded forms are boxed. Asterisks mark residues observed in the equilibrium NHX experiments of Wrabl to exchange by way of large unfoldings (high m values).38 Inset: the red foldon H-bonding pattern. (b) Detected residues that indicate foldon positions in the SNase structure. Views were generated with MolMol 78 using PDB entry 1SNP.

Comparison of the results in Figure 3 with SNase structure makes obvious a quite different relationship. The HX data distribute into three distinct groupings. We applied a cluster analysis45 to the HX data. The analysis computes a metric that compares the distance between data points to the distance between possible groupings and assigns a quality score to each possible grouping. The metric peaks at the three visually apparent clusters circled in Figure 3. The different HX groupings overlap significantly in ΔGHX but much less in the kop dimension. Their separation would be less obvious along either single dimension, but it becomes obvious in the two-dimensional display provided by the kinetic NHX experiment.

Independently, the identification of the blue and red sets by their HX parameters is strikingly validated by the obvious structural grouping of these amino acids in the native protein (Figure 4), which provides a third independent dimension for foldon discrimination. Residues in the middle HX group fall into two clearly distinct structural groupings on opposite sides of the protein, indicated in green and yellow in Figures 3 and 4. The HX data in Figure 3 echo this separation in the kop dimension but do not alone make it clear. In the following we assume this distribution.

In summary, the hydrogens in Figure 3 exchange by way of large unfolding reactions (EX1, m values), they fall into HX groupings defined by common free energy and rates of unfolding, and each HX group matches a coherent structual grouping in the native protein. Unfolding parameters obtained according to Equations 2–4 are listed in Table 1.

SNase foldon units

The pH-dependence of the slowest exchanging hydrogens is coded in blue in Figure 2. They display very similar HX parameters with high equilibrium stability and slow opening rate (Figure 3, Table 1). Many were previously found to have a large m value.38 They are grouped in the native protein (Figure 4). They include the main chain amide hydrogens on both sides of the β5 strand other than the strand termini, their naturally paired H-bonded amides in the neighboring β3 and β4 strands, and α2 amides that intersect β5. We refer to the concerted unfolding/refolding unit defined in this way as the blue foldon. The actual foldon unit may be larger than is detected. For example the end residues of β continue to exchange more rapidly and in EX2 mode, as expected for fraying reactions, which obscures their possible participation in a larger unfolding.

The residues coded in green and yellow in Figure 3 are not cleanly separated by their HX properties but they do have distinct placement within the native structure (Figure 4). The green residues represent a native-like structural unit, the short doubly capped α2 helix (Figure 4). The stability (ΔGHX) of the green foldon is only modestly lower than the blue group which explains why the equilibrium NHX experiment of Wrabl38 could not definitively separate them. The average opening rate of the green foldon is ten times faster than the blue foldon and the reclosing rate is five times faster.

The HX deviation toward EX1 behavior of hydrogens in the yellow set is less impressive but seems clearly present (Figure 2). Most of the grouped yellow residues occupy segments that are in direct contact in the native protein (Figure 4). They represent the β2-β3 hairpin and the contiguous part of β1, which form a mutually H-bonded 3-stranded β-meander sequence, and also the abutting C-terminus of α1 (Figure 4(b)). Five of these residues were observed by Wrabl38 and found to exchange by way of a large unfolding reaction (large m value) as were also residues 64, 65, and maybe 69 (all in α1), suggesting a longer length of the α1 helix within the yellow foldon.

The HX results in Figure 2 marginally detect a final set, called red, that appears to adopt EX1 behavior. In apparent confirmation, the red residues are closely related in the native protein where they form a small β-sheet plus a part of α3 (Figure 4(a) inset). The ΔGHX values are well determined (EX2 region) and reasonably consistent (spread of 1 kcal/mol) as are the kop values except for one outlier. The rather fast reclosing rate places the EX1 rollover point at high pH (where kch = kcl so that kex = ½ kop; see Equation 2). This makes EX1 discrimination increasingly difficult since fewer data points could be obtained above the rollover pH due to the onset of pH-dependent destabilization (Figure 1). Therefore, in fitting the data for the red group we were forced to use also the artifactually high pH 10 data point, which tends to minimize the true EX1 deviation. This factor makes it even more likely that more residues than are directly identified may be involved.

It is interesting that sites involved in function (affected by pdTp and Ca2+ binding) tend to occur in the least stable red foldon, as has similarly been found for cytochrome c.27,28

Misfolding

Comparison of the HX data with SNase structure pinpoints two structural anomalies that suggest non-native interactions in the partially unfolded forms. Misfolding in partially unfolded forms has often been seen before.16,22,46–49

Residue 25 is exposed to HX with the rate and equilibrium parameters of the blue foldon even though it is placed across the β2-β3 hairpin in the yellow foldon. No other β2-β3 residue is protected in this way, not even residue 32 which is the paired partner of residue 25 in the native protein. Similarly residues 103 and 104 have blue foldon HX parameters although they are placed within the green helix foldon. These results suggest a partially unfolded form in which the yellow and green foldons have previously unfolded in lower free energy more probable steps but an energy-minimizing structural rearrangement reprotects these hydrogens in some non-native interactions in the still closed blue unit.

In another apparent misfolding, residue 129 exchanges with yellow foldon parameters even though it is structurally associated with the red foldon. It appears to find a protecting energy-minimizing interaction within the still folded yellow foldon when its parent red unit unfolds.

Discussion

Protein foldons

HX results for 12 proteins have now found structural elements, called foldons, that engage in large unfolding and refolding reactions under native conditions50 and resemble coherent units of the native protein. This interesting behavior might have been expected. One has long understood that secondary structural elements tend to act as cooperative folding units.51,52 When built into three-dimensional proteins, their cooperative unit behavior may well be modified but it seems unlikely that the cooperative property will be wholly lost.

Cooperativity considerations suggest that concerted foldon units may tend to involve entire native-like secondary structural elements. The cooperativity relationship captured in the Zimm-Bragg51 and Lifson-Roig52 formulations applies most obviously to helices. Some known foldons do encompass entire helical lengths1,16,19,53 but others seem not to do so.9 Not surprisingly, entire Ω-loops also act as concerted units6,12 because they are internally packed, self-contained structures.54β-structures tend to break up into smaller separately cooperative units as seen here and before.9,21

In addition to the strikingly native-like configuration of known foldons, one often finds evidence for some non-native interactions.16,21,22,46–49 This too is not surprising. In partially unfolded forms some of the interactions that delimit and stabilize native structural features are absent and normally buried regions are exposed. It can be expected that these loosely structured forms can respond by adopting new energy minimizing interactions.16

SNase foldons

The ability to distinguish different foldons in the present work was promoted by the fact that many SNase protons naturally exchange by way of large unfolding reactions and each hydrogen provides two different exposure parameters, δGHX and kop.

The many residues that define the blue SNase foldon (Figure 2) by their common HX thermodynamic and kinetic parameters (Figure 3; Table 1) specify a coherent native-like structural unit (Figure 4) that includes the β4 and β5 strands and the immediately contiguous part of β3 and α2. Previous results have shown that the slowest exchanging hydrogens of many proteins are exposed to exchange by the transient global unfolding reaction55. In this case the HX parameters of the blue foldon, measured under reversible native conditions (Table 1), represent the last step in the SNase unfolding pathway (average 6x10−6 s−1; total spread < 3x) and the first step in folding. The measured ΔGHX (average ΔGHX 10 kcal/mol; total spread 0.9 kcal/mol) is larger than the stability measured by standard methods as in Figure 1 (ΔGunf = 8 to 8.5 kcal/mol). This not uncommon circumstance is due to the fact that global unfolding measured for SNase in high denaturant is not 2-state.18 The blue foldon refolding rate is equal to the rate for the first step measured for SNase folding by stopped-flow methods (to be described elsewhere).The green foldon accounts for all or part of a short helix. The yellow foldon accounts for the sequential β1-β2-β3 meander, interconnected by multiple H-bonding interactions and short turns, and a contiguous length of α1. This separation of the β-barrel into two different foldons appears to be structurally reasonable. The yellow meander is largely orthogonal to the blue βstrands, and more surface exposed, and the connection between these two units may be tenuous. The lowest free energy red foldon includes some β-strand ends and at least a part of α3. Credibility is suggested by the fact that these residues occur together in the native protein (Figure 4 inset).

Whether or not entire secondary structural lengths participate in the several SNase foldons, as has been seen in some other proteins, cannot be determined from the present data. As often occurs, many other residues are either not measured or continue to exchange by way of local fluctuations which obscures their possible participation in foldon units. Accordingly it seems likely that the foldons entrain more complete secondary structural segments than is definitively observed. It is hard to picture how a major mid-region of well structured helices or β-strands could concertedly unfold without also entraining their end residues in the same unfolding.

Problems in foldon detection

The HX detection of foldon units is made difficult by several factors. The fact that the exchange of many hydrogens is often dominated by small local fluctuations obscures their participation in larger unfolding reactions and makes the recognition of large unfoldings difficult. Even when the presence of unfolding reactions can be demonstrated, the separation of different foldons may not be obvious because foldon hydrogens commonly exhibit a spread of ΔGHX values, on the order of 1 kcal/mol, as in Figure 3. If the spread between foldons is not greater than the spread within, their discrimination is difficult. The spread may be due to fraying mechanisms which cause end hydrogens to exchange faster than others exposed to exchange by the same unfolding.56 Independently, HX may be partially blocked in incompletely unfolded forms43 so that the kch value used in Equations 2 and 3 is incorrect, contributing to an artifactual spread in calculated ΔGHX values. Finally, foldon identification can be confused by the presence of protecting non-native interactions in unfolded forms.

Misfolding in partially unfolded states

Four SNase hydrogens exchange with parameters that identify them with HX groupings that do not match their position in the native protein, indicating the presence of some non-native “misfolding” interactions in the partially unfolded forms. Insight into the source of these interactions comes from prior studies of TIM barrel proteins. Matthews and coworkers have explored the role of large hydrophobic clusters of Ile, Leu, and Val residues in HX behavior. 57,58 They propose a significant role for ILV clusters in defining the structure of partially folded TIM barrels.59 SNase has a large contiguous cluster of 13 such residues. Three of these account for the major misfolding observed here. Leu25, Leu103, and V104 exhibit HX parameters of the blue foldon even though they are placed in other foldons in the native protein. It appears that, when their parent foldon unfolds, thee residues are drawn into the contiguous still folded blue foldon cluster by an energy minimizing rearrangement that both shields their exposed hydrophobic side chains and is able to satisfy their polar main chain amides. This would confer blue foldon HX properties on their amide hydrogens. Similar residual structure, indicated by mutational studies of the large hydrophobic side chains of SNase (m+ and m− mutants),60 may reflect analogous interactions in a compact incompletely unfolded form at equilibrium.

Implications

The present results reveal foldon units in the SNase protein, define (part of) their structure, and measure their equilibrium stability and their kinetic unfolding and refolding rates. As for other proteins,1,6,8–10,12–16,19–26,48,53,61–66 the foldons in SNase are found to resemble elements of the native protein. These results support the emerging view that protein molecules in general can be considered as an assemblage of separate but well integrated foldon units. A related implication is that partially folded - partially unfolded but decisively native-like forms dominate the high free energy space of proteins under native conditions. The intriguing possibility that the SNase foldons may illuminate the steps in its kinetic folding pathway4,67 will be considered elsewhere.

Materials and Methods

Protein preparation

The plasmid pTSN2cc containing the SNase P117G/H124L gene (provided by John L. Markley, U. of Wisconsin-Madison), was transformed into E. Coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS cells (for SNase from the V8 strain of Staphylococcus aureus). Cells were grown in minimal M9 media either with or without 15NH2SO4 and 13C-glucose (37ºC, with ampicillin and chloramphenicol). IPTG was added (1 mM) at optical density 0.8 (600 nm), growth was continued for three hours, and SNase was then purified according to Royer et al.68 except for the following details. Buffers contained 20 mM borate at pH 9. Cell lysate was loaded directly onto a CM column, washed, and eluted with a salt gradient. Dialysis was against water only. Yields were 60 mg/L for unlabeled SNase, 40–50 mg/L for 15N-SNase, and 20 mg/L for 15N,13C-SNase.

All experiments were done at 20ºC in 0.1 M KCl unless otherwise indicated.

Global unfolding

Equilibrium melting was measured as a function of urea and GdmCl concentration (urea shown) from pH 6.5 to 10 by fluorescence and circular dichroism using an AVIV model 202 CD spectrometer. Buffers (50 mM) were K2HPO4 for pH 6.5–7.5, Tris for pH 8.0–8.6, CHES for pH 9.0–9.5, CAPS for pH 10.0–10.5 and CABS for pH 11.0. For pH-dependent melting (no urea), the starting buffer was 10 mM glycine, pH 8.0 and the final solution was KOH at pH 13.0, both containing 5 μM SNase. For each pH increment, a small volume of the second was added to the first, pH was measured, and CD at 222 nm and fluorescence were recorded. Melting data were fit by the Santoro-Bolen equation.69

NMR assignment

For the assignment of main chain (1HN, 15N, 13Cα) and 13Cβ cross peaks, CBCA(CO)NH70,71 and HNCACB71,72 spectra of uniformly 15N and 13C -labeled protein were collected at pH 5.3, 8.0, and 10.0 in 0.1 M NaCl and buffer (with CaCl2 and excess pdTp at pH 5.3) using a 750 MHz Varian INOVA spectrometer and a 500 MHz instrument equipped with a cryoprobe. For backbone amide assignments at intermediate pH values, 15N-HSQC spectra were collected at 0.5 pH unit intervals, and mapped to known assignments to follow the movement of crosspeaks as pH was increased. Overlapping crosspeaks were separated by additional CBCA(CO)NH and HNCACB experiments coupled with H to D exchange. Assignments will be deposited in the BioMagResBank (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu).

Hydrogen exchange

Fully deuterated SNase was prepared by dissolving lyophilized protein in D2O, holding it unfolded for 10 minutes at pDr 12, refolding at pDr 5.3, and lyophilizing. The process was repeated. For HX experiments, pH was corrected to take into account the amount of D2O (pHcorr= pHr + 0.4 x (fraction D2O)).

For pulse-quench experiments, lyophilized deuterated protein was dissolved in D2O buffer (10 mM acetic acid), filtered, and titrated to pDr 5.3. D to H exchange was performed by mixing with high pH pulse buffer to obtain the desired exchange pH (1:5 ratio into H2O with 50 mM bicine (pH 8), CAPS (pH 10) or CABS (pH 11.5)). At measured times (75 ms to 3 hours), exchange was halted by mixing with quench buffer to bring the pH to 5.1 (ratio 3:1 into H2O, 50 mM sodium acetate, 20 mM CaCl2). Mixing used stopped flow for exchange times less than 3 s and manual mixing for longer times. Samples were then deep frozen pending NMR measurement.

For real time hydrogen exchange, lyophilized deuterated protein was dissolved initially in D2O (5 or 10 mM buffer), filtered, and titrated to the pDcorr of the experiment. D to H exchange was initiated by passage into H2O through a spin column (gel filtration, G25 Sephadex) pre-washed in 50 mM buffer, 10% D2O. Serial HSQC spectra were collected until exchange was complete (minutes to months). Buffers were the same as for equilibrium melting except for bicine at pH 8.0. Protein concentration was 1 to 3 mM.

For the analysis of real time D to H exchange measured by sequential 15 minute HSQC spectra, crosspeak intensities analyzed using Felix 2.3 were normalized using the average of a subset of ten crosspeaks that were already fully exchanged at zero time (each pH used a different subset). For NMR analysis of pulse-quench samples, 50 minute HSQC spectra were collected. Spectra were normalized to a common basis by collecting a 1D spectrum for each sample and calculating the average area of the same five peaks for all samples. The exponential time course for exchange of each amide proton and other data fitting used Igor Pro software (WaveMetrics, Inc).

Hydrogen exchange theory

The D to H exchange reaction proceeds in two steps (Eq. 1).33,73

| (1) |

A transient structural opening reaction (local fluctuation, subglobal unfolding, global unfolding) separates protecting H-bonds and exposes the proton to attack by solvent catalyst (OH− -ion dominates above pH 4). In a chemical step, the HX catalyst is then able to remove the proton, which is rapidly replaced by a solvent proton in a non-rate-limiting way. The steady-state HX rate constant is given by Equation 2,33,74

| (2) |

where kch = kint[OH−] and kint is the known intrinsic chemical HX rate calibrated for the equivalent residue amide at the experimental condition.75–77

In the transiently open condition, a kinetic competition between exchange and reclosing ensues. If reclosing is faster (kcl > kch), the structural opening reaction appears as a pre-equilibrium step prior to the rate-limiting chemical exchange, and the HX rate is given by Equation 3. In this so-called EX2 (bimolecular exchange) limit, the measured exchange rate reveals the fraction of time open and leads to the equilibrium constant of the opening reaction, Kop.33

| (3) |

From the Boltzmann relationship (ΔGHX = − RT ln Kop), one can then calculate the apparent free energy of the structural opening reaction that exposes the hydrogen to exchange.

If the chemical exchange rate is made faster, for example at high pH (high concentration of OH− - ion HX catalyst), the measured HX rate can deviate from EX2 behavior. As the chemical rate approaches and then supersedes the reclosing rate, the measured HX rate asymptotically approaches the pH-independent EX1 (monomolecular exchange) limit, where kcl< kch. Equation 2 then reduces to Equation 4 and the opening rate can be obtained.33

| (4) |

These equations hold under steady state conditions where protecting structure is stable (kcl > kop; Kop > 1) and there is no significant population in the opened state. Where these conditions are not met, more general equations are required.31,33 One assumes that EX1 behavior will only occur when exposure to exchange is controlled by a sizeable structural unfolding so that the reclosing rate can be moderately slow. For example, an average amide kch reaches 104 s−1at pH 10 and 20oC. The reclosing of a small structural fluctuation is likely to be much faster, precluding EX1 behavior.

The kinetic native state HX strategy attempts to measure kex over a pH range where EX2 exchange dominates and then transitions to EX1 exchange at increasing pH. When the exchange of a set of hydrogens becomes dominated by the cooperative unfolding of a protein segment, the measurement of HX at an amino-acid-resolved level can identify the unfolding segments in terms of the amino acid residues that participate. Quantitative HX data then allows the calculation of the kinetic (kop, kcl) and equilibrium (ΔGHX) parameters of the unfolding reaction, according to Equations 2 to 4.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH research grants GM031847 and GM075105 (S.W.E.), GM035940 (A. J. W.), and by scholarships from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Fonds Québécois de la Recherche sur la Nature et les Technologies (S. B.). We thank Kim Sharp for help with the cluster analysis, J. O. Wrabl for his GdmCl-dependent SNase HX data, and C. R. Matthews and S. Kathuria for pointing out the connection between their Ile/Leu/Val studies and this work and for information on the ILV clustering in SNase.

Abbreviations

- SNase

staphylococcal nuclease

- N,I, and U

native, intermediate, and unfolded states

- foldon

cooperative folding/unfolding unit

- PUF

partially unfolded with some foldons formed and others not

- HX

hydrogen exchange

- NHX

native state HX

- ΔGHX

unfolding free energy measured by HX

- m value

d(GHX)/d[GdmCl]

- EX1

monomolecular exchange where HX rate is equal to the determining structural opening rate

- EX2

bimolecular exchange where HX rate is proportional to catalyst concentration and the equilibrium constant of the determining structural unfolding

- pdTp

thymidine 3’,5’-diphosphate disodium salt

- GdmCl

guanidinium chloride

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bai Y, Sosnick TR, Mayne L, Englander SW. Protein folding intermediates: Native-state hydrogen exchange. Science. 1995;269:192–7. doi: 10.1126/science.7618079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bai Y, Englander SW. Future directions in folding: The multi-state nature of protein structure. Proteins: Struct Funct Genet. 1996;24:145–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199602)24:2<145::AID-PROT1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Englander SW, Mayne L, Bai Y, Sosnick TR. Hydrogen exchange: The modern legacy of linderstrom-lang. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1101–1109. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Englander SW. Protein folding intermediates and pathways studied by hydrogen exchange. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:213–238. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishna MMG, Lin Y, Mayne L, Englander SW. Intimate view of a kinetic protein folding intermediate: Residue-resolved structure, interactions, stability, folding and unfolding rates, homogeneity. J Mol Biol. 2003;334:501–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishna MMG, Lin Y, Rumbley JN, Walter Englander S. Cooperative omega loops in cytochrome c: Role in folding and function. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:29–36. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00697-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishna MMG, Maity H, Rumbley JN, Englander SW. Branching in the folding pathway of cytochrome c. Protein Sci. 2007;16:1946–1956. doi: 10.1110/ps.072922307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cecconi C, Shank EA, Bustamante C, Marqusee S. Direct observation of the three-state folding of a single protein molecule. Science. 2005;309:2057–2060. doi: 10.1126/science.1116702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chamberlain AK, Handel TM, Marqusee S. Detection of rare partially folded molecules in equilibrium with the native conformation of rnaseh. Nature Struct Biol. 1996;3:782–787. doi: 10.1038/nsb0996-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chamberlain AK, Marqusee S. Comparison of equilibrium and kinetic approaches for determining protein folding mechanisms. Adv Protein Chem. 2000;53:283–328. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(00)53006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bai Y, Englander JJ, Mayne L, Milne JS, Englander SW. Thermodynamic parameters from hydrogen exchange measurements. Methods Enzymol. 1995;259:344–56. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)59051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoang L, Bédard S, Krishna MMG, Lin Y, Englander SW. Cytochrome c folding pathway: Kinetic native-state hydrogen exchange. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12173–12178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152439199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roder H, Elove GA, Englander SW. Structural characterization of folding intermediates in cytochrome c by hydrogen-exchange labeling and proton nmr. Nature. 1988;335:700–4. doi: 10.1038/335700a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu R, Pei W, Takei J, Bai Y. Relationship between the native-state hydrogen exchange and folding pathways of a four-helix bundle protein. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7998–8003. doi: 10.1021/bi025872n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng H, Takei J, Lipsitz R, Tjandra N, Bai Y. Specific non-native hydrophobic interactions in a hidden folding intermediate: Implications for protein folding. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12461–12465. doi: 10.1021/bi035561s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng H, Zhou Z, Bai Y. A protein folding pathway with multiple folding intermediates at atomic resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5026–5031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501372102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rojsajjakul T, Wintrode P, Vadrevu R, Matthews CR, Smith DL. Multi-state unfolding of the alpha subunit of tryptophan synthase, a tim barrel protein: Insights into the secondary structure of the stable equilibrium intermediates by hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry. J Mol Biol. 2004;341:241–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayne L, Englander SW. Two-state vs. Multistate protein unfolding studies by optical melting and hydrogen exchange. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1873–1877. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.10.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuentes EJ, Wand AJ. Local stability and dynamics of apocytochrome b562 examined by the dependence of hydrogen exchange on hydrostatic pressure. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9877–9883. doi: 10.1021/bi980894o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuentes EJ, Wand AJ. Local dynamics and stability of apocytochrome b562 examined by hydrogen exchange. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3687–3698. doi: 10.1021/bi972579s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan S, Kennedy SD, Koide S. Thermodynamic and kinetic exploration of the energy landscape of borrelia burgdorferi ospa by native-state hydrogen exchange. J Mol Biol. 2002;323:363–375. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00882-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bollen YJM, Kamphuis MB, van Mierlo CPM. The folding energy landscape of apoflavodoxin is rugged: Hydrogen exchange reveals nonproductive misfolded intermediates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4095–4100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509133103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silverman JA, Harbury PB. The equilibrium unfolding pathway of a (b/a)8 barrel. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:1031–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korzhnev DM, Salvatella X, Vendruscolo M, Nardo AAD, Davidson AR, Dobson CM, Kay LE. Low-populated folding intermediates of fyn sh3 characterized by relaxation dispersion nmr. Nature. 2004;430:586–590. doi: 10.1038/nature02655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinkam P, Zong C, Wolynes PG. A funneled energy landscape for cytochrome c directly predicts the sequential folding route inferred from hydrogen exchange experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12401–12406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505274102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pletneva EV, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Snapshots of cytochrome c folding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18397–18402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509076102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoang L, Maity H, Krishna MMG, Lin Y, Englander SW. Folding units govern the cytochrome c alkaline transition. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00698-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maity H, Rumbley JN, Englander SW. Functional role of a protein foldon -an & omega;-loop foldon controls the alkaline transition in ferricytochrome. c Proteins: Struct Funct Bioinform. 2006;63:349–355. doi: 10.1002/prot.20757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Englander SW, Mayne L. Protein folding studied using hydrogen-exchange labeling and two-dimensional nmr. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1992;21:243–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.21.060192.001331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Udgaonkar JB, Baldwin RL. Nmr evidence for an early framework intermediate on the folding pathway of ribonuclease a. Nature. 1988;335:694–699. doi: 10.1038/335694a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishna MMG, Hoang L, Lin Y, Englander SW. Hydrogen exchange methods to study protein folding. Methods. 2004;34:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Englander SW. Native-state HX. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:378. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hvidt A, Nielsen SO. Hydrogen exchange in proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 1966;21:287–386. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Englander SW, Kallenbach NR. Hydrogen exchange and structural dynamics of proteins and nucleic acids. Quart Rev Biophys. 1984;16:521–655. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500005217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arrington CB, Robertson AD. Kinetics and thermodynamics of conformational equilibria in native proteins by hydrogen exchange. Methods Enzymol. 2000;323:104–124. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)23363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Theobald D, Mitton-Fry R, Wuttke D. Nucleic acid recognition by ob-fold proteins. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2003;32:115–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.142506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hynes TR, Fox RO. The crystal structure of staphylococcal nuclease refined at 1.7 å resolution. Proteins: Struct Funct Genet. 1991;10:92–105. doi: 10.1002/prot.340100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wrabl JO. Investigations of denatured state structure and m-value effects in staphylococcal nuclease. The Johns Hopkins University; 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Truckses DM, Somoza JR, Prehoda KE, Miller SC, Markley JL. Coupling between trans/cis proline isomerization and protein stability in staphylococcal nuclease. Protein Sci. 1996;5:1907–1916. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hynes TR, Hodel A, Fox RO. Engineering alternative b-turn types in staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5021–30. doi: 10.1021/bi00183a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pace CN. Determination and analysis of urea and guanidine hydrochloride denaturation curves. Methods Enzymol. 1986;131:266–80. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)31045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arrington CB, Robertson AD. Microsecond to minute dynamics revealed by ex1-type hydrogen exchange at nearly every backbone hydrogen bond in a native protein. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:1307–1317. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maity H, Lim WK, Rumbley JN, Englander SW. Protein hydrogen exchange mechanism: Local fluctuations. Protein Sci. 2003;12:153–160. doi: 10.1110/ps.0225803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hernandez G, Jenney FE, Adams MWW, LeMaster DM. Millisecond time scale conformational flexibility in a hyperthermophile protein at ambient temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3166–3170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040569697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurita T. An efficient agglomerative clustering algorithm using a heap. Pattern Recognition. 1991;24:205–209. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Capaldi AP, Kleanthous C, Radford SE. Im7 folding mechanism: Misfolding on a path to the native state. Nature Struct Biol. 2002;9:209–216. doi: 10.1038/nsb757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nishimura C, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Identification of native and non-native structure in kinetic folding intermediates of apomyoglobin. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:139–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krishna MMG, Lin Y, Englander SW. Protein misfolding: Optional barriers, misfolded intermediates, and pathway heterogeneity. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:1095–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu Y, Matthews CR. Proline replacements and the simplification of the complex, parallel channel folding mechanism for the alpha subunit of trp synthase, a tim barrel protein. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:1131–1144. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00723-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Englander SW, Mayne L, Krishna MMG. Protein folding and misfolding: Mechanisms and principles from hydrogen exchange. Q Rev Biophysics. 2008 doi: 10.1017/S0033583508004654. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zimm GH, Bragg JK. Theory of the phase transition between helix and random coil in polypeptide chains. J Chem Phys. 1959;31:526–535. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lifson S, Roig A. On the theory of the helix-coil transition in polypeptides. J Chem Phys. 1961;34:1963–1974. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chi EY, Krishnan S, Randolph TW, Carpenter JF. Physical stability of proteins in aqueous solution: Mechanism and driving forces in nonnative protein aggregation. Pharm Res. 2003;20:1325–1336. doi: 10.1023/a:1025771421906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leszczynski JF, Rose GD. Loops in globular proteins: A novel category of secondary structure. Science. 1986;234:849–855. doi: 10.1126/science.3775366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huyghues-Despointes BMP, Pace CN, Englander SW, Scholtz JM. Measuring the conformational stability of a protein by hydrogen exchange. Methods Mol Biol. 2001;168:69–92. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-193-0:069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krishna MMG, Lin Y, Mayne L, Walter Englander S. Intimate view of a kinetic protein folding intermediate: Residue-resolved structure, interactions, stability, folding and unfolding rates, homogeneity. J Mol Biol. 2003;334:501–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gu Z, Zitzewitz JA, Matthews CR. Mapping the structure of folding cores in tim barrel proteins by hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry: The roles of motif and sequence for the indole-3-glycerol phosphate synthase from sulfolobus solfataricus. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:582–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gu Z, Rao MK, Forsyth WR, Finke JM, Matthews CR. Structural analysis of kinetic folding intermediates for a tim barrel protein, indole-3-glycerol phosphate synthase, by ydrogen exchange mass spectrometry and gô tymodel simulation. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:528–546. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu Y, Vadrevu R, Kathuria S, Yang XY, Matthews CR. A tightly packed hydrophobic cluster directs the formation of an off-pathway sub-millisecond folding intermediate in the alpha subunit of tryptophan synthase, a tim barrel protein. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:1624–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shortle D, Stites WE, Meeker AK. Contributions of the large hydrophobic amino acids to the stability of staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8033–41. doi: 10.1021/bi00487a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu Y, Mayne L, Englander SW. Evidence for an unfolding and refolding pathway in cytochrome c. Nature Struct Biol. 1998;5:774–778. doi: 10.1038/1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Milne JS, Xu Y, Mayne LC, Englander SW. Experimental study of the protein folding landscape: Unfolding reactions in cytochrome c. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:811–822. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maity H, Maity M, Englander SW. How cytochrome c folds, and why: Submolecular foldon units and their stepwise sequential stabilization. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Maity H, Maity M, Krishna MMG, Mayne L, Englander SW. Protein folding: The stepwise assembly of foldon units. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4741–4746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501043102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krishna MMG, Maity H, Rumbley JN, Lin Y, Englander SW. Order of steps in the cytochrome c folding pathway: Evidence for a sequential stabilization mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:1411–1420. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yan S, Gawlak G, Smith J, Silver L, Koide A, Koide S. Conformational heterogeneity of an equilibrium folding intermediate quantified and mapped by scanning mutagenesis. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:811–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krishna MMG, Englander SW. A unified mechanism for protein folding: Predetermined pathways with optional errors. Protein Sci. 2007;16:449–464. doi: 10.1110/ps.062655907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Royer CA, Hinck AP, Loh SN, Prehoda KE, Peng X, Jonas J, Markley JL. Effect of amino acid substitutions on the pressure denaturation of staphylococcal nuclease as monitored by fluorescence and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5222–5232. doi: 10.1021/bi00070a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Santoro MM, Bolen DW. Unfolding free energy changes determined by the linear extrapolation method. 1. Unfolding of phenylmethanesulfonyl α-chymotrypsin using different denaturants. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8063–8068. doi: 10.1021/bi00421a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grzesiek S, Bax A. Correlating backbone amide and side chain resonances in larger proteins by multiple relayed triple resonance nmr. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:6291–3. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Muhandiram DR, Kay LE. Gradient-enhanced triple-resonance three-dimensional nmr experiments with improved sensitivity. J Magn Reson, Ser B. 1994;103:203–16. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wittekind M, Mueller L. Hncacb, a high-sensitivity 3d nmr experiment to correlate amide-proton and nitrogen resonances with the alpha- and beta-carbon resonances in proteins. J Magn Reson, Ser B. 1993;101:201–5. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Linderstrom-Lang K. Deuterium exchange between peptides and water. Chem Soc (London), Spec Publ. 1955;(No 2):1–20. 21–4. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Linderstrøm-Lang K. Deuterium exchange and protein structure. In: Neuberger A, editor. Symposium on protein structure. Methuen; London: 1958. pp. 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Molday RS, Englander SW, Kallen RG. Primary structure effects on peptide group hydrogen exchange. Biochemistry. 1972;11:150–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00752a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Connelly GP, Bai Y, Jeng MF, Englander SW. Isotope effects in peptide group hydrogen exchange. Proteins: Struct Funct Genet. 1993;17:87–92. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bai Y, Milne JS, Mayne L, Englander SW. Primary structure effects on peptide group hydrogen exchange. Proteins: Struct Funct Genet. 1993;17:75–86. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wuethrich K. Molmol: A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J Molec Graph. 1996;14:29–32. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.