Abstract

The characterization of internal ribosome entry sites (IRESs) in virtually all lentiviruses prompted us to investigate the mechanism used by the feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) to produce viral proteins. Various in vitro translation assays with mono- and bicistronic constructs revealed that translation of the FIV genomic RNA occurred both by a cap-dependent mechanism and by weak internal entry of the ribosomes. This weak IRES activity was confirmed in feline cells expressing bicistronic RNAs containing the FIV 5′ untranslated region (UTR). Surprisingly, infection of feline cells with FIV, but not human immunodeficiency virus type 1, resulted in a great increase in FIV translation. Moreover, a change in the cellular physiological condition provoked by heat stress resulted in the specific stimulation of expression driven by the FIV 5′ UTR while cap-dependent initiation was severely repressed. These results reveal the presence of a “dormant” IRES that becomes activated by viral infection and cellular stress.

Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) is a lentivirus discovered in 1987 by Pedersen and colleagues (29) by isolation from peripheral blood lymphocytes of a domestic cat (Felis catus) with an immunodeficiency syndrome similar to AIDS. The FIV genomic RNA is capped and polyadenylated and contains three large open reading frames, gag, pol, and env, that code for the structural, enzymatic, and envelope proteins, respectively. The extensive similarities between FIV and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) make FIV an important model for the development of anti-HIV-1 vaccines and therapies and the starting point for the production of lentiviral vectors suitable for gene transfer (reviewed in references 3 and 7).

Translational control plays a key role in the regulation of gene expression in higher eukaryotes. For most eukaryotic mRNAs, translation commences with the binding of the 43S ribosome to the cap structure at the 5′ end of the mRNA. This preinitiation complex, which is composed of Met-tRNAi, the 40S ribosomal subunit, and associated initiation factors, is then able to move along the untranslated region (UTR) in a 5′-to-3′ direction (30). This process has been termed ribosomal scanning, as it allows progression of the translation preinitiation complex until an AUG codon is encountered (20). For efficient recognition, this AUG (underlined) should be in the context (A/G)CCAUGG, the purine at position −3 being critical, together with the G at the +4 position (19).

In the late 1980s, the study of picornavirus translation shed light on an alternative mechanism of protein synthesis. It is now well established that translation initiation on picornavirus RNAs, which are uncapped and present a long 5′ UTR, takes place by a cap-independent mechanism that is directed by an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) located within the 5′ UTR of the genomic RNA (2, 13, 14). Although considered an unconventional, marginal mechanism of translation initiation, this process has now been described in many other viruses and a growing number of cellular genes from yeast, drosophila, and mammals (for a recent review see reference 12). In a large number of studies, it has been shown that the mechanism of internal ribosome entry is mediated by the IRES structure (28, 35, 42) with the potential involvement of noncanonical translation factors named IRES trans-acting factors (ITAFs) (2, 38).

It has become clear that translational control plays an important role in the replication cycle of retroviruses (1). Indeed, IRESs have been characterized within the genomic 5′ UTRs of simple gamma retroviruses such as the Friend and Moloney murine leukemia viruses (4, 9, 40) and in lentiviruses such as the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) (24, 25), HIV-1 (5, 6), and HIV-2 (11). It should be noted that lentiviral IRESs appear to be quite peculiar, as they are located within both the 5′ UTR and the gag coding region (for HIV-1 and SIV) or exclusively within the gag coding region (HIV-2) (1). As a result, additional Gag isoforms have been characterized in the cases of HIV-1 (p40), SIV (p43), and HIV-2 (p50 and p44) that are synthesized by the exclusive use of the IRES located within the gag coding region. These isoforms appear to play a role in viral replication as deletion or mutation of their AUG initiation start site results in profound modifications of viral growth and replication kinetics (6, 24).

These results prompted us to investigate the mechanism by which the FIV genomic RNA was translated. In vitro, protein synthesis driven by the FIV 5′ UTR was very efficient in a capped monocistronic context but very weak once inserted into a bicistronic vector. Furthermore, FIV translation was inhibited by cleavage of eIF4G and/or the presence of antisense oligonucleotides that arrest ribosomal scanning from the messenger 5′ end. Expression of a bicistronic vector containing the FIV 5′ UTR was very low in Crandell feline kidney (CrFK) cells, indicating that internal initiation occurs at very low efficiency on the FIV genomic RNA. However, FIV infection resulted in specific stimulation of the FIV IRES with no effect on other picornaviral or retroviral IRESs. In addition, changing the physiological status of these cells by continuous heat shock resulted in a decrease in cap-dependent translation and stimulation of second gene expression. Taken together, these results show that the FIV genomic RNA contains a “dormant” IRES which can be activated under certain cellular conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

Standard procedures were used for plasmid DNA construction, purification, and linearization. For pMono-AUG1, the sequence of the FIV DNA from the beginning of R (transcription start site) to AUG1 (nucleotide [nt] 412) was inserted into pMLV-CB93 (4) at the NheI site. For the construction of all the bicistronic vectors used, sequences of FIV from R to AUG1 (pBi-AUG1) and from R to AUG at position 655 (pBi-AUG4) were amplified by PCR and inserted into the pBi-NL vector at the NheI site (described in reference 11). pBi-AUG1(ΔCMV) and pBi-AUG4(ΔCMV) were constructed from pBi-AUG1 and pBi-AUG4, respectively, digested with NruI and HindIII to remove the entire cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter.

The construction of pBi-EMCV (25), pBi-HIV2-AUG1, and pBi-PV has been described previously (11). For the construction of pMono-EMCV, the encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) sequence contained in pBi-EMCV was digested with NheI and cloned into the NheI site of pMLV-CB93.

Production of T7 DNA fragments.

In order to generate the constructs T7-5′UTR, T7-AUG1, T7-AUG2, T7-AUG3, and T7-AUG4, the DNA sequence corresponding to the FIV coding region was amplified by PCR by using a 3′ oligonucleotide starting at the end of the capsid region and a 5′ oligonucleotide starting with the T7 promoter sequence and complementary to the +1 region of the 5′ UTR or to the AUG at position 412, 442, 532, or 655, respectively. After purification of the PCR fragments, in vitro transcription was performed as described below.

In vitro transcription and translation.

In vitro transcription was carried out as previously described (34). The resulting capped and uncapped RNAs were translated in Flexi RRL (Promega) in the presence of 75 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM each amino acid (except methionine), and 0.6 mCi/ml [35S]methionine. Translation products were then separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and the gel was dried and subjected to autoradiography for 12 h with BioMax films (Eastman Kodak Co.). The intensity of the bands was quantified with a STORM 850 PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Preparation of in vitro-translated foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) L protease was carried out as previously described (31).

Annealing of 2′-O-methyloligoribonucleotides to RNA.

Antisense 2′-O-methyloligoribonucleotides 5′AAUCUCGCCCCUGUCCAUUCCC3′ and 5′AAGUCCCUGUUCGGGCGCCAA3′ (Eurogentec), complementary to the sequence encompassing the initiator AUG at position 412 or the primer binding site (PBS; nt 141 to 161), were hybridized to the RNA in 20 mM HEPES-KCl (pH 7.6) and 100 mM KCl for 3 min at 65°C, and the temperature was decreased slowly prior to addition of the translation mixture.

Cell culture.

CrFK and human epithelial 293T cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (GIBCO, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Bio West). Stable cell lines were generated by DNA transfection of CrFK cells and selection with 1 mg/ml G418 added to the culture medium. For gene expression analysis under heat shock conditions, the cells were seeded at 1.5 × 106 into 6-cm plates and maintained for 15 h at 42°C.

Virus production, titration, and infection.

For virus production, 3 × 106 293 T cells were seeded into 10-cm plates at 24 h before transfection. Transfection was performed by the calcium phosphate method with 10 μg of FIV molecular clone pCMV/RU5 (23) (kindly provided by Tahir A. Rizvi) or of HIV-1 Δenv molecular clone pNL4.3 (27) and 4 μg of vesicular stomatitis virus Env (VSV-G) expression plasmid (21). The day after transfection, the medium was changed, and after 24 h, the supernatant was filtered (0.45-μm-pore-size filter) and either used for infection or centrifuged to concentrate the virus in order to evaluate virus production by measurement of reverse transcriptase activity (see below).

For virus titration, 1.5 × 105 CrFK cells were seeded onto a 24-well plate and infected with serial dilutions of pseudotyped FIV particles (produced as described above). Twenty-four hours after infection, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 200 μg/ml hygromycin and the selection was maintained for 3 weeks. The multiplicity of infection (MOI) was determined as the lowest dilution of the stock in which cellular clones could be detected.

For viral infection, 1.5 × 106 CrFK cells were seeded into 6-cm plates and exposed to the same amount of either FIV or HIV-1 (normalized by measurement of reverse transcriptase activity). After an additional 24 h, the medium was changed, and 24 h later, supernatants were harvested, filtered (0.45-μm-pore-size filter), and centrifuged at 4°C at 75,000 rpm in a Beckman TL-100 for 1 h. Viral pellets were resuspended in 25 μl of reverse transcription (RT) buffer in order to determine the reverse transcriptase activity.

Metabolic labeling.

CrFK cells (6 × 105) stably expressing bicistronic plasmid pBi-AUG1 were seeded into a six-well plate and infected with an amount of FIV corresponding to an MOI of 10. At 48 h postinfection, the culture medium was replaced with serum-free, l-methionine-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (GIBCO, Invitrogen). After 30 min of starvation, 10% serum and 100 μCi/ml [35S]methionine were added. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, cells were harvested, washed three times with 1× phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed. Equal amounts of proteins were resolved by SDS-15% PAGE and visualized by autoradiography.

Enzymatic activities.

Protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent. β-Galactosidase (β-gal) activity was determined by using the β-gal Reporter Gene Assay kit (chemiluminescent; Roche) as described by the manufacturer. Neomycin phosphotransferase (Neo) activity was determined by [α-32P]ATP phosphate transfer to kanamycin as described in reference 32.

RT-PCR.

Cellular RNAs were extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and treated with DNase (RQ1 DNase; Promega). After ethanol precipitation, 5 μg of these cellular RNAs was subjected to RT with the Superscript II RT system (Invitrogen) and primer annealing on LacZ. RT reactions were amplified by PCR with Go Taq DNA polymerase (Promega) and with the T7 oligonucleotide 5′ TAATACGACTCACTATAG 3′ as the 5′ primer and the −40 LacZ oligonucleotide 5′ GTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC 3′ as the 3′ primer.

Reverse transcriptase activity.

Ten microliters of concentrated virus suspension, prepared as described above, was added to 40 μl of RT cocktail [60 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 180 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 6 mM dithiothreitol, 0.6 mM EGTA, 0.12% Triton X-100, 6 μg of oligo(dT)/ml, 12 μg of poly(rA)/ml, 0.05 mM [α-32P]dTTP (800 Ci/mmol)] and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Ten microliters was spotted onto DE-81 paper and washed three times with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate). A PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) was used to quantify the radioactivity incorporated.

RESULTS

FIV translation in a monocistronic context.

A segment of the FIV genomic RNA comprising the complete FIV 5′ UTR followed by the gag coding region (positions +1 to 1487) was generated from the pSP64-FIV plasmid (22). Capped and uncapped mRNAs were transcribed in vitro and translated in the rabbit reticulocyte lysate system (RRL) at various concentrations (Fig. 1). Gag synthesis from the capped transcripts was about three- to fourfold more efficient than expression from the uncapped RNAs (compare lanes 1 to 5 to lanes 6 to 10), suggesting that translation occurs via a cap-dependent mechanism. It should be noted that downstream initiation products (a, b, and c in Fig. 1) were observed following capped and uncapped RNA translation. The relative intensity of the fast-migrating bands (a, b, and c) was stronger from the uncapped transcript than from the capped one (compare lane 3 and 8), suggesting that they are not breakdown products from Gag but rather appeared to be due to initiation at downstream sites.

FIG. 1.

FIV translation is cap dependent in the RRL. Capped and uncapped FIV-Gag and FIV-LacZ transcripts (schematically represented on the upper part of each panel) were translated in the RRL at various RNA concentrations, as indicated. After 45 min of incubation at 30°C in the RRL, the samples were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE and the dried gel was submitted to autoradiography. The shorter Gag isoforms (a, b, and c) and the molecular weight markers are indicated. Data are representative of at least three experiments. MW, molecular mass.

The complete FIV 5′ UTR, from +1 to the AUG codon (+412), was then inserted upstream of the LacZ reporter gene, and the resulting capped and uncapped RNAs were translated in the RLL (Fig. 1, lanes 11 to 20). Once again, protein synthesis was more efficient from capped RNAs (compare lanes 11 to 15 with lanes 16 to 20), indicating that translation occurs predominantly by 5′-end-dependent ribosomal scanning.

Next, we examined the translation of both capped FIV-Gag and capped FIV-LacZ RNAs in the presence of increasing amounts of FMDV L protease (Fig. 2). This protease has the ability to cleave initiation factor eIF4G at a unique site, thus resulting in the inhibition of cap-dependent translation, whereas IRES-driven translation is either unaffected or stimulated (18, 26). In the RRL, addition of the viral protease resulted in the inhibition of translation of FIV-Gag (lanes 1 to 3) and FIV-LacZ (lanes 4 to 6) mRNAs together with a reduction in the expression of globin-lacZ mRNAs (lanes 7 to 9). As expected, translation directed by the EMCV IRES was not affected and even stimulated by the cleavage of eIF4G following the addition of the L protease (lanes 10 to 12). It is noteworthy that the level of smaller Gag proteins, namely, a, b, and c, resulting from alternative initiation (lanes 1 to 3) was not affected by the proteolytic cleavage of eIF4G, suggesting that they may use an internal initiation mechanism. Proteolytic cleavage of eIF4G was verified by Western blot analysis, which revealed that most of the endogenous eIF4G was cleaved after a 10-min incubation with the L protease (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

The FMDV L protease inhibits translation driven by the FIV 5′ UTR. (A) The RRL was preincubated for 10 min without (lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10) or with 0.4 μl (lanes 2, 5, 8, and 11) or 0.6 μl (lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12) of in vitro-expressed FMDV L protease. Different capped RNA transcripts, namely, FIV-Gag (100 ng), FIV-LacZ (100 ng), globin-lacZ (10 ng), and EMCV-LacZ (100 ng), were translated. After 45 min of incubation at 30°C in the RRL, the samples were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE and the dried gel was submitted to autoradiography. The relative intensities of the bands were quantified, and the results, expressed as percentages of the control (no protease added), are presented in the histogram at the bottom of each panel. The Gag isoforms are indicated by the arrows (a, b, and c). Data are representative of at least three experiments. (B) At the end of the 10-min preincubation period, samples (1 μl) from the experiment described above were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and incubated with antibodies specific to the C-terminal part of eIF4GI. The positions of the intact molecule and the cleavage products (Cp) are indicated on the right. MW, molecular mass.

Taken together, these data indicate the requirement of intact eIF4G for efficient initiation of FIV translation at AUG1 and confirm that translation proceeds mainly through a cap-dependent mechanism in the RRL.

Both the 5′ UTR and the gag coding region are capable of weak internal initiation in a bicistronic context.

Additional experiments were then carried out in which the FIV 5′ UTR alone or the FIV 5′ UTR followed by a segment of the gag coding region encompassing AUG1 to AUG4 (nt 412 to 655) was inserted into a bicistronic vector coding for neomycin (first gene) and LacZ (second gene). Bicistronic and monocistronic LacZ RNAs were translated in the RRL at the same molar concentration to allow direct comparison of translational efficiencies. As a control, we used mono- and bicistronic RNAs in which the EMCV IRES was driving LacZ expression (Fig. 3A contains a description of the plasmids). As expected, expression from the capped and uncapped EMCV RNAs occurred with similar efficiencies (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 1 and 2 to lanes 3 and 4) and insertion of the EMCV IRES into a bicistronic RNA resulted in substantial expression of the second gene (Fig. 3B, lanes 5 and 6).

FIG. 3.

In vitro translation driven by the FIV 5′ UTR is inefficient in a bicistronic vector. (A) Schematic diagram of the constructs used. (B) Capped and uncapped monocistronic transcripts together with uncapped bicistronic transcripts containing the EMCV IRES (left panel), the FIV 5′ UTR alone (lanes 7 to 10, 15, and 16), or the FIV 5′ UTR followed by the gag coding region (lanes 11 to 14, 17, and 18) were translated in the RRL at two different concentrations (23 and 29 nM) as indicated. After 45 min of incubation at 30°C, the samples were processed by 12% SDS-PAGE and submitted to autoradiography. Data are representative of at least three experiments. MW, molecular mass.

In contrast, translation from the monocistronic FIV constructs was stimulated by the 5′ cap structure (Fig. 3B, lanes 7 and 8 versus lanes 9 and 10 and lanes 11 and 12 versus lanes 13 and 14), as previously observed, and β-gal expression from the bicistronic FIV constructs was very weak (lanes 15 and 16). Extension of the FIV insert to the gag coding region led to the production of longer isoforms of β-gal (Fig. 3B, lanes 11 to 14, 17, and 18), which most probably resulted from initiation at one, or several, of the downstream in-frame AUG codons. However, the overall yield of β-gal produced was only moderately stimulated by insertion of the gag coding region.

Given these data, a critical issue was to determine whether the low level of expression detected in a bicistronic context was due to readthrough, reinitiation, or leaky ribosomal scanning or rather could be considered a mechanism of weak but genuine internal initiation. Thus, antisense 2′-O-methyloligoribonucleotides complementary to different sequences of the FIV genomic RNA were used (Fig. 4). Upon hybridization, these oligoribonucleotides form a very stable oligonucleotide-RNA duplex molecule that is not unwound by scanning 40S ribosomes (15). The first antisense oligonucleotide was complementary to the gag AUG initiation site (oligonucleotide AUG1), while the second was complementary to the 20-nt region of the PBS (oligonucleotide PBS; nt 141 to 161). Complete annealing of the oligonucleotides and integrity of the resulting oligonucleotide-target mRNA duplex was verified on a nondenaturing gel (Fig. 4C). Expression of the oligonucleotide AUG1-mRNA duplex revealed that translation was inhibited by about 90% as a result of blockage of the AUG initiation site (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 to 3). However, annealing on the PBS resulted in severe but not complete inhibition of Gag production (about 60% inhibition), suggesting that a substantial amount of the ribosomes may land downstream of the PBS (Fig. 4A, lanes 4 to 6). Hybridization of oligonucleotide AUG1 to the Bi-5′UTR-AUG4 bicistronic construct resulted in total loss of the full-length protein but did not affect the yield of the shorter proteins detected (Fig. 4B, compare lane 1 to lanes 2 and 3). This confirms that they originate from independent translation initiation events and not from a posttranslation modification or degradation of Gag. Interestingly, annealing of the oligonucleotide PBS did not affect the weak translation observed in a bicistronic setting (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 4 and 5 with lane 3), indicating that the FIV genomic RNA is capable of internal initiation, although this is clearly not the predominant mechanism used to initiate protein synthesis.

FIG. 4.

The FIV 5′ UTR has genuine IRES activity. (A) Increasing concentrations (10 and 25 μM, denoted by the triangle) of 2′-O-methyloligoribonucleotides that are complementary to the region downstream of AUG1 or of the PBS region were annealed to 0.3 pmol of capped FIV-Gag RNA or (B) uncapped bicistronic transcript containing the FIV 5′ UTR followed by a segment of the gag coding region. The position of annealing of the 2′-O-methyloligoribonucleotides on the two transcripts is schematically represented at the top of each panel. After 45 min of incubation at 30°C in the RRL, the samples were processed by 12% SDS-PAGE and submitted to autoradiography. (C) The resulting oligonucleotide-mRNA duplex that is formed upon hybridization of the 2′-O-methyloligoribonucleotides in panel A was visualized on a nondenaturing agarose gel. MW, molecular mass.

Translation initiation in feline cells.

Next, we examined whether the poor FIV IRES activity detected in the RRL was due to the use of a heterologous in vitro system that may lack a specific ITAF. Therefore, the CrFK cell line was chosen because these cells support rapid replication of FIV (41). CrFK cells were transfected with the construct pBi-5′UTR-AUG1, pBi-5′UTR-AUG4, pBi-PV (containing the poliovirus [PV] IRES in an intercistronic position), or pBi-HIV-2-AUG1 (with the HIV-2 5′ UTR in an intercistronic position) and then selected for neomycin resistance. After 3 weeks of selection, the polyclonal cell population was assessed for neomycin and β-gal activities.

As a negative control, CrFK cells were transfected either with constructs in which the CMV promoter had been entirely deleted (ΔCMV) or with the CMV-containing parental plasmids. The lack of β-gal expression from the ΔCMV constructs indicated that no cryptic promoter was used to generate monocistronic RNAs (Fig. 5A). In addition, an RT-PCR analysis was carried out on stably transfected CrFK cells, and this failed to detect any shorter isoform of the pBi-5′UTR-AUG1 and pBi-5′UTR-AUG4 bicistronic RNAs, suggesting that no aberrant splicing events had taken place (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

The FIV 5′ UTR is inefficient at supporting internal initiation in CrFK cells. (A) Comparative analysis of β-gal activity expressed from the CMV and ΔCMV pBi-5′UTR-AUG1 and pBi-5′UTR-AUG4 plasmids that were transiently transfected into CrFK cells. Results are expressed as percentages of the β-gal activity from each parental plasmid (containing the CMV promoter and set at 100%). (B) Agarose nondenaturing electrophoretic analysis of 5 μg of total cytoplasmic RNA extracted from CrFK cells stably expressing Bi-AUG1 and Bi-AUG4 after RT and PCR (lanes 4 and 7) or PCR without prior RT (lanes 3 and 6) or RT-PCR without RNAs (lane 1). PCR products from the parental plasmids pBi-5′UTR-AUG1 and pBi-5′UTR-AUG4 (lanes 2 and 5) were run in parallel as size markers. The region amplified by PCR is schematically depicted at the top of the panel. (C) Translational activities of the bicistronic constructs pBi-5′UTR-AUG1, pBi-5′UTR-AUG4, pBi-PV, and pBi-HIV2 that were stably transfected into CrFK cells. The results are expressed as the ratio of β-gal (second gene) to neomycin (first gene) activities and compared to the activity of the positive control, pBi-PV, which was arbitrary set to 100%.

For each of the four bicistronic constructs that were expressed in CrFK cells, the ratio of β-gal/neomycin activities was measured (Fig. 5C). The results showed that β-gal expression driven by the construct containing the FIV 5′ UTR was very weak compared to the PV control (arbitrarily set at 100%). In fact, the β-gal/neomycin ratio from the pBi-5′UTR-AUG1 construct was similar to that obtained with the HIV-2 5′ UTR previously considered to be unable to drive internal initiation (11). Furthermore, addition of the gag coding region did not rescue protein synthesis, as the activity of the bicistronic construct pBi-5′UTR-AUG4 was even lower since the β-gal/neomycin ratio was barely above the threshold detection level. An inhibitory effect of the insertion of the gag coding region into a bicistronic construct had been previously observed for HIV-1 (5) and HIV-2 (11) by a still unknown mechanism.

Taken together, these data confirmed that, under normal conditions, FIV translation occurs almost exclusively via a cap-dependent mechanism.

FIV IRES activity is enhanced by FIV infection.

Next, we set out to study the impact of FIV infection and replication on the translation of its cognate genomic RNA. As a control, a similar experimental procedure was used in parallel with the related virus HIV-1. Accordingly, FIV or HIV-1 virions were prepared by transfecting 293T cells with viral clone pCMV/RU5 FIV (23) or HIV-1 pNL4.3 (27). It should be noted that both viruses were pseudotyped with VSV-G in order to allow efficient entry into CrFK cells (21). CrFK stable cell lines expressing the Bi-5′UTR-AUG1, the Bi-PV, or the Bi-HIV-2 construct were infected with FIV or HIV-1 at an MOI of 10.

Surprisingly, infection of the cells with FIV resulted in strong stimulation of translation driven by the FIV 5′ UTR, as monitored by the increase in β-gal expression (Fig. 6A). In addition, the translation driven by the active PV IRES or the negative control HIV-2 5′ UTR was not enhanced, thus suggesting a very specific role for FIV infection in its cognate 5′ UTR (Fig. 6A). In agreement with this, we also failed to monitor any stimulation of translation when the cells were infected with HIV-1.

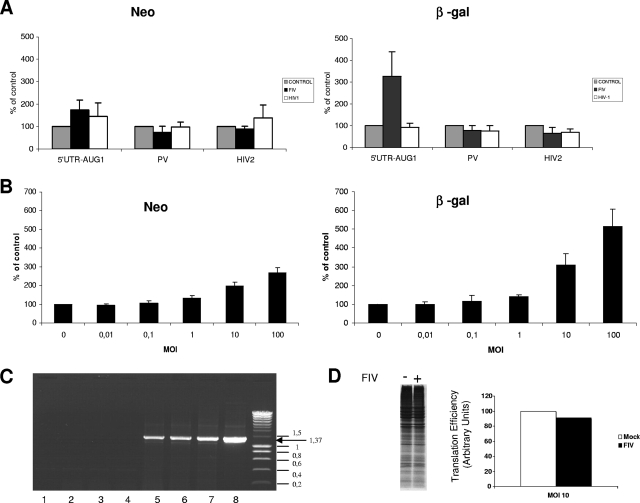

FIG. 6.

FIV, but not HIV-1, infection enhances translational activity from its cognate IRES. (A) CrFK cells expressing the bicistronic construct pBi-5′UTR-AUG1, pBi-PV, or pBi-HIV2 were infected with equal amounts of VSV-G-pseudotyped FIV and HIV-1 at an MOI of 10 (see Materials and Methods). At 48 h postinfection, neomycin (left panel) and β-gal (right panel) activities in mock-infected (gray), FIV-infected (black), or HIV-1-infected (white) cells were measured. The Neo and β-gal activities in mock-infected cells were arbitrarily set to 100%. (B) CrFK cells expressing the pBi-5′UTR-AUG1 construct were infected with VSV-G-pseudotyped FIV virions at MOIs ranging from 0.01 to 100, as indicated. At 48 h postinfection, Neo and β-gal activities were determined and plotted as percentages of the control (mock-infected cells, set at 100%). (C) Agarose nondenaturing electrophoretic analysis of 5 μg of total cytoplasmic RNA extracted from CrFK cells stably expressing Bi-AUG1 and infected with FIV at MOIs of 0 (lanes 2 and 5), 10 (lanes 3 and 6), and 100 (lanes 4 and 7). RNA were analyzed after RT and PCR (lanes 5, 6, and 7) or PCR without prior RT (lanes 2, 3, and 4) or RT-PCR without RNAs (lane 1). PCR products from the parental plasmid pBi-5′UTR-AUG1 (lane 8) were run in parallel as size markers. Molecular size markers were run at the right side of the gel, and the sizes of the bands are indicated in kilobases. (D) CrFK cells stably transfected with bicistronic plasmid pBi-5′UTR-AUG1 were infected with pseudotyped FIV particles (MOI = 10). The effect on the overall cellular translation was analyzed by incubating the cells with [35S]methionine for 1 h. Cell extracts were processed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. The intensities of the bands, corresponding to global protein synthesis, were quantified, and the results, expressed as percentages of the noninfected cells, are presented in the histogram on the right of the autoradiogram.

The next step was to investigate whether the increase in FIV IRES activity could be directly correlated with the amount of viral particles delivered to the cells. Thus, CrFK cells stably expressing the Bi-5′UTR-AUG1 construct were infected with FIV at MOIs ranging from 0.01 to 100; at 48 h postinfection, neomycin and β-gal activities were determined, and the results show that stimulation of FIV IRES activity occurs in a dose-dependent manner with a mere sixfold increase in β-gal production at the highest MOI (Fig. 6B). It should be noted that the presence of a putative cryptic promoter was ruled out by transfecting bicistronic constructs in which the CMV promoter was previously deleted as described in the legend to Fig. 5 (data not shown).

Surprisingly, translation of the first gene (neomycin) was also increased in a dose-dependent manner by FIV infection (Fig. 6B). RT-PCR analysis was carried out on stably transfected CrFK cells, and this failed to detect any shorter isoform of the pBi-5′UTR-AUG1 bicistronic RNAs, suggesting that no aberrant splicing events had taken place during the course of viral infection (Fig. 6C).

A priori, this suggests that FIV infection could stimulate both cap-dependent and IRES-driven translation. However, this does not seem to be the case since the metabolic labeling of total cellular protein synthesis remained unchanged (Fig. 6D). Thus, in view of the recent data obtained by Niepmann and colleagues (16), it is likely that the massive increase in IRES-driven gene expression (β-gal) results in the concomitant stimulation of the upstream reporter gene (neomycin).

Prolonged heat shock increased FIV IRES activity.

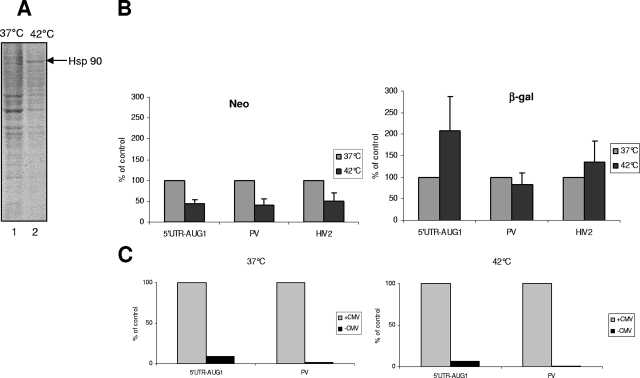

However, to definitely exclude the possibility that the β-gal activity benefits in some way from the increased expression of the first gene, we investigated the FIV IRES activity under conditions in which cellular cap-dependent translation was repressed. One way to create stress conditions and to inhibit cap-dependent translation is to submit cells to a prolonged heat shock as previously described (17). To this aim, CrFK cells constitutively expressing pBi-5′UTR-AUG1, pBi-PV, or pBi-HIV-2-AUG1 were subjected to a 15-h period of heat shock (see Materials and Methods). Metabolic labeling of the cells at 37°C and 42°C was realized (Fig. 7A), and it shows an inhibition of total protein synthesis and the induction of a protein running at 90 kDa, which is likely to be heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90). Neomycin production was decreased by 50% in cells incubated at 42°C (Fig. 7B, left panel), while the measurement of β-gal activity revealed an average twofold enhancement under heat shock conditions in the case of the FIV construct with no change for PV and only a marginal increase for the bicistronic construct bearing the HIV-2 5′ UTR (Fig. 7B, right panel). It should be noted that the presence of a heat shock-inducible promoter was ruled out by expressing promoterless bicistronic constructs and analyzing β-gal activity at both 37°C and 42°C (Fig. 7C).

FIG. 7.

Prolonged heat shock reveals FIV IRES activity. CrFK cells stably expressing bicistronic plasmids pBi-AUG1, pBi-PV, and pBi-HIV2 (see Fig. 5) were exposed to heat shock at 42°C for 15 h. (A) The effect of heat shock on cellular translation was quantified by labeling the cells with [35S]methionine for 1 h. Cell extracts were then processed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. The position of heat shock protein Hsp90 is indicated. (B) Analysis of the effects of heat shock on neomycin and β-gal activities (left and right panels, respectively) for each of the constructs described above. The results are expressed as percentages of the activity at 37°C. (C) Activity of β-gal expressed by bicistronic vectors pBi-AUG1 and pBi-PV with or without a CMV promoter at 37°C or 42°C. Results are expressed as percentages of β-gal activity.

Therefore, these data indicate that the FIV genomic RNA can use an IRES-dependent mechanism when cap-dependent translation is restricted.

DISCUSSION

The identification and characterization of IRES elements in the genomic RNA of lentiviruses such as HIV and SIV (1) prompted us to investigate whether the FIV 5′ UTR could also function as an IRES. In vitro experiments performed with the RRL revealed a pronounced cap dependence of FIV RNA (Fig. 1). This was observed when the 5′ UTR was driving the synthesis of a reporter gene or the Gag polyprotein. In the latter case, the effect was accompanied by the appearance of fast-migrating bands corresponding to weak alternative translation initiation at three AUG codons located in the matrix coding region of gag (Fig. 1 and 2). However, the synthesis and role of these Gag isoforms were not investigated further in this work as we focused instead on translational events that take place at the authentic AUG initiation site. Interestingly, the addition of the FMDV L protease and the hybridization of an antisense 2′-O-methyloligoribonucleotide complementary to the PBS (nt 141 to 161) only partially inhibited the translation of the capped monocistronic RNAs (Fig. 2 and 4), thus suggesting that an alternative mechanism of translation is also probably used. Moreover, insertion of the FIV 5′ UTR into a bicistronic vector resulted in weak (about 1/30 of the yield from the corresponding capped monocistronic construct; Fig. 3) but detectable expression of the second gene. In addition, the use of 2′-O-methyloligoribonucleotides revealed that initiation proceeded by internal entry of the ribosome and was not the result of leaky scanning or reinitiation from the 5′ gene (Fig. 4). However, with respect to translational efficiency, the use of internal initiation by the FIV 5′ UTR is clearly a secondary mechanism compared to the use of 5′-dependent ribosomal scanning (Fig. 3). Such poor efficiency in vitro could reflect the need for some ITAFs that may be absent from the RRL. Thus, we performed experiments with fibroblastic cat cells that were stably expressing bicistronic vectors (Fig. 5). This feline cell line is widely used to study FIV replication and efficiently supports FIV protein production (41). However, the low expression of β-gal (second gene) in these cells confirmed that the FIV 5′ UTR supports only weak internal initiation (Fig. 5). These results contrast with data obtained with other members of the lentiviral family such as HIV-1, HIV-2, and SIV, as they all contain one or several IRESs within their genomes (1).

Thus, we next set out to examine the effect of FIV infection on the translation of its cognate genomic RNA. Remarkably, under these experimental conditions, the production of β-gal from the bicistronic construct containing the FIV 5′ UTR was increased, whereas it remained virtually unaffected when driven by the PV IRES or the HIV-2 5′ UTR. This enhanced activity correlated nicely with the input of FIV delivered to the cells and was not observed following infection with the closely related virus HIV-1 (Fig. 6).

These results are of particular interest as they show for the first time that a lentiviral IRES can be specifically stimulated by homologous viral infection. Preliminary data indicate that this effect is the result of pleiotropic cellular and viral gene expression, as neither one of the individual viral FIV genes was able to stimulate IRES activity when transfected on its own (data not shown).

However, it could be argued that the enhancement of β-gal expression could be somehow influenced by the concomitant increase in the activity of the first gene. Therefore, in order to exclude this possibility, cap-dependent translation was inhibited by submitting the CrFK stable cell lines to a prolonged heat shock for 15 h. After this treatment, the activity of the first capped cistron (neomycin) was decreased by 50% for all of the constructs. Interestingly, β-gal production driven by the HIV-2 and PV 5′ UTRs remained virtually unchanged, whereas FIV expression was stimulated twofold (Fig. 7). Several reports have implied a role for heat shock in IRES-dependent translation (17, 39), although the mechanism(s) by which this occurs remains largely unknown. Another possible explanation is that the strong inhibition of cap-dependent translation creates a competitive advantage for IRES-driven translation. Whatever mechanism is at play, the result confirms that the FIV 5′ UTR has the ability to function as an IRES under stress conditions. It is noteworthy that the mechanism used by FIV is quite distinct from that of some cellular mRNAs, such as c-myc, which is capable of using either 5′ ribosomal scanning or internal initiation (8, 36). Indeed, c-myc clearly exhibits features of a classical IRES as it works well in a bicistronic setting and its translation is not disrupted by eIF4G cleavage (37). The situation for FIV is different, as it exhibits features of a cap-dependent gene by all criteria, i.e., high translational efficiency, translational enhancement by the presence of a 5′ cap moiety, inhibition by the cleavage of eIF4G, ribosomal scanning from the 5′ end, and virtually no activity in a bicistronic setting. In fact, under normal conditions the FIV IRES is somehow in a “dormancy” state and its participation in viral protein synthesis is only marginal. However, it can become active following heat shock and/or FIV infection.

In any case, the ability of the FIV genomic RNA to use two mechanisms for translation initiation is likely to provide a very strong competitive advantage to promote viral protein synthesis at all times during infection of the host cell. Thus, probably during the early step of viral infection, FIV translation proceeds almost exclusively by canonical 5′ cap-dependent ribosomal scanning, which is far more efficient than IRES-driven translation. This ensures rapid and efficient production of the structural proteins and enzymes. However, a large number of events, such as availability of the eIF4E initiation factor, progression through the cell cycle, heat shock, or hypoxia (10, 33), can selectively compromise cap-dependent initiation. Therefore, the activation of the IRES mechanism would ensure continuous protein production independently of the physiological status of the cell. In agreement with this hypothesis, it is noteworthy that the FIV protease has the ability to partially cleave initiation factor eIF4G (data not shown).

In summary, our data clearly show that the FIV genomic RNA can use two major distinct mechanisms for translation initiation and their use is conditioned by progression through viral infection or cellular stress conditions. Future work will aim at characterizing the molecular determinants involved in this mechanism.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Cécile Herbreteau for helpful discussions and comments throughout this work, Tahir A. Rizvi (Department of Medical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, United Arab Emirates University Al Ain, UAE) for kindly donating the pCMV/RU5 vector, and S. J. Morley for providing eIF4G antibodies.

V.C. was funded by Pisa University, Université Franco-Italienne, and FRM grants. This work was supported by grants from the ANRS, ANR, INSERM, ACI, and TRIOH from EC 6th PCRD.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 January 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balvay, L., M. L. Lastra, B. Sargueil, J.-L. Darlix, and T. Ohlmann. 2007. Translational control of retroviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5128-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belsham, G. J., and N. Sonenberg. 2000. Picornavirus RNA translation: roles for cellular proteins. Trends Microbiol. 8330-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendinelli, M., M. Pistello, S. Lombardi, A. Poli, C. Garzelli, D. Matteucci, L. Ceccherini-Nelli, G. Malvaldi, and F. Tozzini. 1995. Feline immunodeficiency virus: an interesting model for AIDS studies and an important cat pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 887-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berlioz, C., and J.-L. Darlix. 1995. An internal ribosomal entry mechanism promotes translation of murine leukemia virus gag polyprotein precursors. J. Virol. 692214-2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brasey, A., M. Lopez-Lastra, T. Ohlmann, N. Beerens, B. Berkhout, J.-L. Darlix, and N. Sonenberg. 2003. The leader of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomic RNA harbors an internal ribosome entry segment that is active during the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. J. Virol. 773939-3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buck, C. B., X. Shen, M. A. Egan, T. C. Pierson, C. M. Walker, and R. F. Siliciano. 2001. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag gene encodes an internal ribosome entry site. J. Virol. 75181-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burkhard, M. J., and G. A. Dean. 2003. Transmission and immunopathogenesis of FIV in cats as a model for HIV. Curr. HIV Res. 115-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrd, M. P., M. Zamora, and R. E. Lloyd. 2005. Translation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4GI (eIF4GI) proceeds from multiple mRNAs containing a novel cap-dependent internal ribosome entry site (IRES) that is active during poliovirus infection. J. Biol. Chem. 28018610-18622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deffaud, C., and J.-L. Darlix. 2000. Characterization of an internal ribosomal entry segment in the 5′ leader of murine leukemia virus env RNA. J. Virol. 74846-850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gebauer, F., and M. W. Hentze. 2004. Molecular mechanisms of translational control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5827-835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herbreteau, C. H., L. Weill, D. Decimo, D. Prevot, J.-L. Darlix, B. Sargueil, and T. Ohlmann. 2005. HIV-2 genomic RNA contains a novel type of IRES located downstream of its initiation codon. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 121001-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson, R. J. 2005. Alternative mechanisms of initiating translation of mammalian mRNAs. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 331231-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson, R. J., S. L. Hunt, C. L. Gibbs, and A. Kaminski. 1994. Internal initiation of translation of picornavirus RNAs. Mol. Biol. Rep. 19147-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson, R. J., and A. Kaminski. 1995. Internal initiation of translation in eukaryotes: the picornavirus paradigm and beyond. RNA 1985-1000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansson, H. E., G. J. Belsham, B. S. Sproat, and M. W. Hentze. 1994. Target-specific arrest of mRNA translation by antisense 2′-O-alkyloligoribonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 224591-4598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jünemann, C., Y. Song, G. Bassili, D. Goergen, J. Henke, and M. Niepmann. 2007. Picornavirus internal ribosome entry site elements can stimulate translation of upstream genes. J. Biol. Chem. 282132-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim, Y. K., and S. K. Jang. 2002. Continuous heat shock enhances translational initiation directed by internal ribosomal entry site. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 297224-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirchweger, R., E. Ziegler, B. J. Lamphear, D. Waters, H.-D. Liebig, W. Sommergruber, F. Sobrino, C. Hohenadl, D. Blaas, R. E. Rhoads, and T. Skern. 1994. Foot-and-mouth disease virus leader proteinase: purification of the Lb form and determination of its cleavage site on eIF-4γ. J. Virol. 685677-5684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozak, M. 1991. Structural features in eukaryotic mRNAs that modulate the initiation of translation. J. Biol. Chem. 26619867-19870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozak, M. 1989. The scanning model for translation: an update. J. Cell Biol. 108229-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mangeot, P. E., D. Negre, B. Dubois, A. J. Winter, P. Leissner, M. Mehtali, D. Kaiserlian, F. L. Cosset, and J.-L. Darlix. 2000. Development of minimal lentivirus vectors derived from simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVmac251) and their use for gene transfer into human dendritic cells. J. Virol. 748307-8315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moscardini, M., M. Pistello, M. Bendinelli, D. Ficheux, J. T. Miller, C. Gabus, S. F. Le Grice, W. K. Surewicz, and J.-L. Darlix. 2002. Functional interactions of nucleocapsid protein of feline immunodeficiency virus and cellular prion protein with the viral RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 318149-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mustafa, F., P. Jayanth, P. S. Phillip, A. Ghazawi, R. D. Schmidt, K. A. Lew, and T. A. Rizvi. 2005. Relative activity of the feline immunodeficiency virus promoter in feline and primate cell lines. Microbes Infect. 7233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicholson, M. G., S. M. Rue, J. E. Clements, and S. A. Barber. 2006. An internal ribosome entry site promotes translation of a novel SIV Pr55Gag isoform. Virology 349325-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohlmann, T., M. Lopez-Lastra, and J.-L. Darlix. 2000. An internal ribosome entry segment promotes translation of the simian immunodeficiency virus genomic RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 27511899-11906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohlmann, T., M. Rau, S. J. Morley, and V. M. Pain. 1995. Proteolytic cleavage of initiation factor eIF-4γ in the reticulocyte lysate inhibits translation of capped mRNAs but enhances that of uncapped mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 23334-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ottmann, M., C. Gabus, and J.-L. Darlix. 1995. The central globular domain of the nucleocapsid protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is critical for virion structure and infectivity. J. Virol. 691778-1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otto, G. A., and J. D. Puglisi. 2004. The pathway of HCV IRES-mediated translation initiation. Cell 119369-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pedersen, N. C., E. W. Ho, M. L. Brown, and J. K. Yamamoto. 1987. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic virus from domestic cats with an immunodeficiency-like syndrome. Science 235790-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prévôt, D., J.-L. Darlix, and T. Ohlmann. 2003. Conducting the initiation of protein synthesis: the role of eIF4G. Biol. Cell 95141-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prévôt, D., D. Decimo, C. H. Herbreteau, F. Roux, J. Garin, J.-L. Darlix, and T. Ohlmann. 2003. Characterization of a novel RNA-binding region of eIF4GI critical for ribosomal scanning. EMBO J. 221909-1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramesh, N., and W. R. Osborne. 1991. Assay of neomycin phosphotransferase activity in cell extracts. Anal. Biochem. 193316-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richter, J. D., and N. Sonenberg. 2005. Regulation of cap-dependent translation by eIF4E inhibitory proteins. Nature 433477-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ronfort, C., S. De Breyne, V. Sandrin, J.-L. Darlix, and T. Ohlmann. 2004. Characterization of two distinct RNA domains that regulate translation of the Drosophila gypsy retroelement. RNA 10504-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spahn, C. M., E. Jan, A. Mulder, R. A. Grassucci, P. Sarnow, and J. Frank. 2004. Cryo-EM visualization of a viral internal ribosome entry site bound to human ribosomes: the IRES functions as an RNA-based translation factor. Cell 118465-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stoneley, M., T. Subkhankulova, J. P. Le Quesne, M. J. Coldwell, C. L. Jopling, G. J. Belsham, and A. E. Willis. 2000. Analysis of the c-myc IRES; a potential role for cell-type specific trans-acting factors and the nuclear compartment. Nucleic Acids Res. 28687-694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thoma, C., G. Bergamini, B. Galy, P. Hundsdoerfer, and M. W. Hentze. 2004. Enhancement of IRES-mediated translation of the c-myc and BiP mRNAs by the poly(A) tail is independent of intact eIF4G and PABP. Mol. Cell 15925-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vagner, S., B. Galy, and S. Pyronnet. 2001. Irresistible IRES. Attracting the translation machinery to internal ribosome entry sites. EMBO Rep. 2893-898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vagner, S., C. Touriol, B. Galy, S. Audigier, M. C. Gensac, F. Amalric, F. Bayard, H. Prats, and A. C. Prats. 1996. Translation of CUG- but not AUG-initiated forms of human fibroblast growth factor 2 is activated in transformed and stressed cells. J. Cell Biol. 1351391-1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vagner, S., A. Waysbort, M. Marenda, M. C. Gensac, F. Amalric, and A. C. Prats. 1995. Alternative translation initiation of the Moloney murine leukemia virus mRNA controlled by internal ribosome entry involving the p57/PTB splicing factor. J. Biol. Chem. 27020376-20383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamamoto, J. K., E. Sparger, E. W. Ho, P. R. Andersen, T. P. O'Connor, C. P. Mandell, L. Lowenstine, R. Munn, and N. C. Pedersen. 1988. Pathogenesis of experimentally induced feline immunodeficiency virus infection in cats. Am. J. Vet. Res. 491246-1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yaman, I., J. Fernandez, H. Liu, M. Caprara, A. A. Komar, A. E. Koromilas, L. Zhou, M. D. Snider, D. Scheuner, R. J. Kaufman, and M. Hatzoglou. 2003. The zipper model of translational control: a small upstream open reading frame is the switch that controls structural remodeling of an mRNA leader. Cell 113519-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]