Abstract

In many organisms, polo kinases appear to play multiple roles during M-phase progression. To provide new insights into the function of the budding yeast polo kinase Cdc5, we generated novel temperature-sensitive cdc5 mutants by mutagenizing the C-terminal noncatalytic polo box domain, a region that is critical for proper subcellular localization. One of these mutants, cdc5-11, exhibited a temperature-sensitive growth defect with an abnormal spindle morphology. Strikingly, provision of a moderate level of benomyl, a microtubule-depolymerizing drug, permitted cdc5-11 cells to grow significantly better than the isogenic CDC5 wild type in a FEAR (cdc Fourteen Early Anaphase Release)-independent manner. In addition, cdc5-11 required MAD2 for both cell growth and the benomyl-remedial phenotype. These results suggest that cdc5-11 is defective in proper spindle function. Consistent with this view, cdc5-11 exhibited abnormal spindle morphology, shorter spindle length, and delayed microtubule regrowth at the nonpermissive temperature. Overexpression of CDC5 moderately rescued the spc98-2 growth defect. Interestingly, both Cdc28 and Cdc5 were required for the proper modification of the spindle pole body components Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2 in vivo. They also phosphorylated these three proteins in vitro. Taken together, these observations suggest that concerted action of Cdc28 and Cdc5 on Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2 is important for proper spindle functions.

Found from budding yeast to mammalian cells, the polo kinases are a conserved subfamily of Ser/Thr protein kinases that play pivotal roles during the cell cycle and proliferation (2, 46). In addition to the N-terminal kinase domain, they are characterized by the presence of a highly conserved polo box domain (PBD) in the C-terminal noncatalytic region (16). In mammalian cells, multiple Plks (Plk1 to -4) with distinct regulation and functions appear to exist. However, the genomes of Drosophila melanogaster, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae each contain only one apparent Plk1 homolog (Polo [44], Plo1 [30], and Cdc5 [20], respectively). Overexpression of the mammalian polo-like kinase Plk1 complements the defect associated with the temperature-sensitive cdc5-1 mutation (24), suggesting that the critical functions of Plk1 and Cdc5 are fundamentally conserved.

It is widely appreciated that Plk1 and its homologs play multiple roles during M-phase progression, including mitotic entry, metaphase/anaphase transition, and cytokinesis. Several observations suggest that polo kinases play critical roles in regulating spindle functions. The initial findings showed that mutations in the Drosophila polo result in defects in bipolar spindle formation (26, 44). Subsequent studies in fission yeast also disclosed that loss of Plo1 function leads to a mitotic arrest as a result of a monopolar spindle (30). In vertebrates, microinjection of anti-Plk1 antibody into cultured cells or anti-Plx1 (the Xenopus Plk1 homolog) into Xenopus embryos leads to a defect in centrosome maturation and bipolar spindle formation (23, 34). Thus, the roles of the polo kinases in regulating microtubule function have been largely conserved throughout evolution.

However, the molecular mechanism through which Plk1 and its functional homologs regulate the spindle function is still elusive. It has been shown that addition of active recombinant Drosophila Polo rescues impaired microtubule nucleation activity of salt-stripped centrosomes in vitro (9), suggesting that Polo contributes to microtubule nucleation and growth through a yet-unidentified Polo substrate(s) at the centrosomes. In cultured mammalian cells, Plk1 phosphorylates and displaces a centrosomal protein, Nlp, and this event is thought to permit the establishment of a centrosomal scaffold important for microtubule nucleation (5). Plk1 also appears to regulate microtubule dynamics by either positively or negatively regulating various components associated with microtubules. It has been reported that Plk1 phosphorylates and diminishes the microtubule-stabilizing activity of TCTP (48). On the other hand, Xenopus Plx1 has been suggested to stabilize microtubules by negatively regulating a microtubule-destabilizing protein, Stathmin/Op18 (4). However, how Plk1 and its homologs regulate these seemingly dissimilar events and how these events are coordinated with other cell cycle processes have yet to be further investigated. The identification of additional Plk1 substrates and revealing of previously uncharacterized pathways are likely important to shed light on the mechanism underlying Plk1-dependent spindle regulation.

A growing body of evidence suggests that the conserved C-terminal domain of polo kinases, termed the PBD, plays a crucial role in targeting the catalytic activities of these enzymes to specific subcellular locations, such as spindle poles, kinetochores, and the midbody (25, 40). These findings suggest that the PBD is a multifunctional domain capable of interacting with diverse cellular proteins at specific subcellular structures. To aid our understanding of the function of PBD and to further investigate the role of mammalian Plk1 in regulating spindle function, we employed a genetically amenable budding yeast organism and studied the function of the Plk1 homolog Cdc5 by randomly mutagenizing its C-terminal PBD. Characterization of one of the obtained temperature-sensitive cdc5 mutants, cdc5-11, revealed that Cdc5 is required for proper spindle microtubule dynamics and growth. Intriguingly, Cdc5 phosphorylated several spindle pole body (SPB) or spindle-associated proteins, such as Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2, in vitro, raising the possibility that Cdc5 regulates spindle functions by directly phosphorylating these proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, growth conditions, and cell counts.

The yeast strains used in this study are shown in Table 1. Cells were cultured in YEP (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto peptone) supplemented with 2% glucose. Synthetic minimal medium (37) supplemented with the appropriate nutrients was employed to select for plasmid maintenance. Yeast transformation was carried out by the lithium acetate method (17). All the cells were counted after cell aggregates were separated by sonication with a Sonicator Model W-225R (Heat Systems-Ultrasonics, Inc., Plainview, NY) at 40% duty with no. 4 output for 4 seconds.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| KLY1546a | MATahis3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura-3-1 | Laboratory stock |

| KLY2470 | KLY1546 LEU2::TUB1-GFP cdc5Δ::KanMX6 TRP1::CDC5-HA3 | 31 |

| KLY2466 | KLY1546 LEU2::TUB1-GFP cdc5Δ::KanMX6 TRP1::cdc5-11-HA3 | This study |

| KLY4733 | KLY2470 mad2Δ::URA3 | This study |

| KLY4731 | KLY2466 mad2Δ::URA3 | This study |

| KLY2970 | KLY2470 HIS3::CDC14TAB6-1 | 31 |

| KLY2962 | KLY2466 HIS3::CDC14TAB6-1 | This study |

| YYW37 | MATacdc5-dg::URA3 | 15 |

| KLY3928 | KLY1546 cdc5-dg::URA3 | This study |

| KLY4208 | KLY3928 LEU2::TUB1-GFP | This study |

| KLY4440 | MATaura3-52 lys2-801am ade2-101och trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 spc98-2 | M. Winey |

| KLY5426 | MATacdc28-as1 cdc5Δ::HphMX4 + YCplac33-GAL1-HA-EGFP-cdc5-1 | 1 |

| KLY5851 | KLY5426 HphMX4Δ::KanMX6 NUD1-HA::HphMX4 | This study |

| KLY5824 | KLY5426 SLK19-HA::KanMX6 | This study |

| KLY5839 | KLY5426 STU2-HA::KanMX6 | This study |

KLY1546 is in a W303-1A genetic background.

Strain and plasmid construction.

The cdc5-11 mutants (KLY2466 and KLY2962) were generated as described previously (31). Briefly, the temperature-sensitive cdc5-11 allele, which does not support cell viability at 37°C, was first integrated at the TRP1 locus of a W303-1A-derived cdc5Δ strain (KLY2372) that was kept viable by the presence of a URA3-based YCplac33-CDC5 plasmid. The YCplac33-CDC5 plasmid was shuffled out by plating onto 5-fluoro-orotic acid. To alleviate the mitotic exit defect of the cdc5 mutant, a dominant allele of CDC14 (CDC14TAB6-1) (38) was integrated at the HIS3 locus. Strain KLY5426 (cdc28-as1 cdc5Δ plus pGAL1-cdc5-1) has been described previously (1). Complete deletions of CDC5 (cdc5Δ::kanMX6) and MAD2 (mad2Δ::URA3) were generated by the one-step gene disruption method (27). To generate strains expressing NUD1-HA, SLK19-HA, or STU2-HA under the respective endogenous promoter control, the corresponding loci were C-terminally tagged with a PCR fragment containing three hemagglutinin (HA) epitopes (HA3), essentially by using the method described by Longtine et al. (27). Strain KLY3928, which expresses a heat-inducible degron mutant for Cdc5 (cdc5-dg), was generated by backcrossing strain KLY1546 (W303-1A background) with strain YYW37 (a gift of S. Elledge, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) three times. In order to inhibit the cdc28-as1 activity, the cells were treated with 0.5 μM 1NM-PP1 (a gift of K. Shokat, University of California, San Francisco, CA) at least 20 min after release from the α-factor block to allow passage through G1 phase.

To generate plasmid pKL3838 (Table 2), a MAD2 genomic clone (a gift of Dan Burke, University of Virginia Medical Center, Charlottesville, VA) was digested with PvuII and BamHI and then inserted into the pRS313 vector digested with EcoRV and BamHI. Plasmid pCJ187 was generated by inserting a SacI-XhoI fragment containing the TUB4 open reading frame into the pRS426 vector digested with the corresponding enzymes.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

Flow cytometry analyses.

To examine cell cycle progression, the strains were arrested with α-factor, released into fresh medium, and then harvested at the indicated time points. The cells were washed twice with H2O, fixed with 70% ethanol, and then treated with RNase A (1 mg/ml) in phosphate-buffered saline for 30 min at 37°C. After the cells were disrupted by sonication for 1 min, they were stained with propidium iodide (50 μg/ml) in phosphate-buffered saline. Flow cytometry analyses were performed with the Cellquest program (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

λ phosphatase treatment and immunoblotting analyses.

To dephosphorylate cellular proteins, approximately 100 μg of total cellular lysates was treated with 400 units of λ phosphatase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) at room temperature for 30 min. Immunoblotting analyses were carried out with either anti-HA antibody or anti-Cdc28 antibody as described previously (40). Proteins that interacted with the antibodies were detected by the enhanced-chemiluminescence Western detection system (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL).

Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy.

Indirect immunofluorescence was performed as described previously (25). Microtubules were stained using YOL1/34 rat anti-tubulin antibody (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corp., New York) and goat anti-rat CY3 antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). DNA was visualized with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The stained cells were viewed under a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope equipped with HeNe, argon visible-light, and argon UV lasers.

Microtubule regrowth assay and measurement of microtubule length.

To perform microtubule regrowth assays, spindles were first disrupted by incubating the cells with 15 μg/ml of nocodazole for 2 h. The cells were then released into fresh medium and fixed at the indicated time points. Confocal images were acquired at room temperature using a Zeiss LSM 510 system mounted on a Zeiss Axiovert 100 M microscope with an oil immersion Plan-Neofluar 100×/1.3 objective lens. To measure the spindle length in S phase, cells were arrested with hydroxyurea for 2 h and then fixed for confocal microscopic analyses. The spindle length (the length of the Tub1-green fluorescent protein [GFP] fluorescence signal) was measured by collecting 50 z slices with an interval of 0.1 μm and a total stack size of 4.90 μm. All confocal datasets had a frame size of 512 pixels by 512 pixels and a scan zoom of 2 and were line averaged two times. All z-stacked images were analyzed using Zeiss AIM software version 3.2 sp1 (Carl Zeiss GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). Three-dimensional measurements were acquired by using the orthogonal tool in the Zeiss AIM software. Starting at the z slice that corresponded to the beginning point of the microtubule staining, the beginning point was marked with the crosshair tool as the zero coordinate. The microtubule was measured in three dimensions by marking the microtubule point on each z slice and recording the measurement (in μm) from one point to the next throughout the entire z stack.

Time-lapse imaging.

Cells were mounted on agarose pads as described previously (47). Time-lapse imaging was carried out at 37°C on a wide-field microscope imaging system, which consisted of an inverted Nikon TE300 microscope with a 60× 1.4-numeric-aperture objective (Nikon), a Lambda 10-2 filter changer, and an I-Pentamax camera (Princeton Instruments/Roper Scientific, Trenton, NJ). Images were acquired with a GFP filter set (Chroma Technology Corp., Rockingham, VT) with excitation light attenuated to 10% of transmission with a neutral-density filter. The image system was controlled by Metamorph software (Molecular Devices, Downington, PA).

RESULTS

The cdc5-11 mutant exhibits a temperature-sensitive growth defect with abnormal spindle morphology.

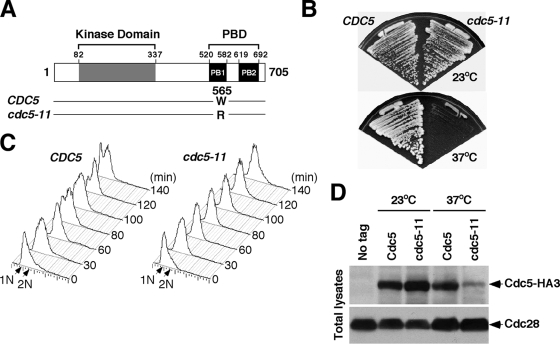

Cdc5 plays critical roles at multiple stages during M-phase progression. To generate cdc5 mutants defective in distinct stages of M phase, we previously generated various temperature-sensitive cdc5 mutants by mutagenizing the C-terminal PBD of Cdc5 (31). Here, we describe one of these mutants, cdc5-11, which is largely defective in both microtubule dynamics and regrowth (see below). Sequence analyses revealed that the cdc5-11 allele possessed a single point mutation (W565R) within the PB1 motif of the PBD (Fig. 1A). The cdc5-11 mutant grew well at 23°C but exhibited a severe temperature-sensitive growth defect at 37°C (Fig. 1B). Provision of a centromeric CDC5 plasmid fully complemented this defect (data not shown). Flow cytometry analyses of the cells being released from the α-factor block at 37°C revealed that cdc5-11 arrested at a point after DNA replication (2N DNA content), whereas wild-type CDC5 cells went through the cell cycle normally under the same conditions (Fig. 1C). The steady-state level of the cdc5-11 protein was similar to that of the wild-type Cdc5 at 23°C but was significantly diminished, yet detectable, at 37°C (Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

The cdc5-11 mutant exhibits a temperature-sensitive growth defect and arrests at a late stage of the cell cycle. (A) Sequence alignment between wild-type CDC5 and the cdc5-11 mutant. cdc5-11 possesses the W565R mutation in the C-terminal PBD. Gray box, the kinase domain of Cdc5; PB1 and PB2, the PB1 and PB2 motifs of the PBD. (B) Strains KLY2470 (CDC5) and KLY2466 (cdc5-11) were grown on YEP-glucose for 3 days at the indicated temperatures. (C) For flow cytometry analyses, strains KLY2470 (CDC5) and KLY2466 (cdc5-11) were cultured overnight, arrested in G1 by α-factor treatment at 23°C, washed, and transferred into YEP-glucose medium at 37°C. Samples were taken at the indicated time points for analyses. (D) Strains KLY2470 and KLY2466 were cultured overnight and then shifted to 37°C for 3.5 h. Total cellular proteins were prepared and then analyzed to determine the levels of Cdc5-HA3 or cdc5-11-HA3 expression (top) or the level of Cdc28 as an internal loading control (bottom).

We then closely examined the phenotype associated with the cdc5-11 mutation by shifting the cultures to 37°C for 3.5 h. In contrast to wild-type CDC5, a large fraction of the cdc5-11 mutant exhibited a large-budded morphology with divided nuclei (data not shown), a phenotype similar to that of the previously characterized cdc5-1 mutant (20). Unlike the cdc5-1 mutant, however, the spindle morphology of the cdc5-11 mutant was aberrant in a large fraction of the population. When cultured at the restrictive temperature for 3.5 h, approximately 25% of the cdc5-11 mutants exhibited a spindle morphology that was noticeably bent and often discontinuous (Fig. 2A). Under the same conditions, wild-type CDC5 cells did not exhibit any discernible spindle defect (Fig. 2A). These observations suggest that Cdc5 activity is required for proper spindle function and that an intact PBD is required for this event.

FIG. 2.

The cdc5-11 mutant exhibits a benomyl-remedial growth defect with aberrant spindle structures. (A) Strains KLY2470 (CDC5) and KLY2466 (cdc5-11) cultured at 37°C for 3.5 h were fixed and subjected to immunostaining with anti-tubulin antibody. Cells with aberrant spindle structures were quantified (right). The error bars represent standard deviations. (B) Strains KLY2470 (CDC5), KLY4733 (CDC5 mad2Δ), KLY2466 (cdc5-11), and KLY4731 (cdc5-11 mad2Δ) were cultured overnight, serially diluted, spotted onto either YEP-glucose or YEP-glucose containing 15 μg/ml of benomyl, and then incubated at 30°C. (C) Strains KLY4731 (cdc5-11 mad2Δ) and KLY4733 (CDC5 mad2Δ) transformed with either control vector or a centromeric MAD2 plasmid (pMAD2) were spotted on a minimal plate to select for pMAD2 and then incubated at either 23°C or the semipermissive 34°C. Two independent transformants of KLY4731 were tested. (D) Strains KLY2470 (CDC5), KLY2466 (cdc5-11), and KLY2962 (cdc5-11 CDC14TAB6-1) were streaked onto YEPD and incubated at the indicated temperatures. (E) Strains KLY2470, KLY2466, KLY2970 (CDC5 CDC14TAB6-1), and KLY2962 were cultured overnight and spotted on YEP-glucose or YEP-glucose plus 15 μg/ml of benomyl.

Benomyl suppresses the cdc5-11 growth defect.

If the spindle defect in the cdc5-11 mutant were in part due to the lack of microtubule dynamics, then this defect could be remedied by the provision of benomyl, a microtubule-depolymerizing agent. To examine this possibility, we tested the viability of cdc5-11 and its isogenic wild-type CDC5 by culturing the cells in the presence of various concentrations of benomyl at 30°C, a semipermissive temperature that does not seriously induce the cdc5-11 growth defect. Strikingly, provision of 15 μg/ml of benomyl caused the cdc5-11 mutant to outgrow the isogenic wild-type CDC5 cells (Fig. 2B). A similar but less dramatic effect was also observed in the presence of either 7.5 μg/ml or 30 μg/ml of benomyl (data not shown). Loss of a spindle checkpoint component, MAD2, abolished the benomyl-dependent suppression of cdc5-11 viability (Fig. 2B). As expected if the cdc5-11 mutant possesses an intrinsic spindle defect, provision of centromeric MAD2 significantly enhanced the viability of the cdc5-11 mad2Δ mutant (Fig. 2C). Notably, loss of a component of the anaphase-promoting complex, CDC23, which induces a mitotic exit delay, failed to suppress the cdc5-11 growth defect (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These observations suggest that the rescue of the cdc5-11 defect by benomyl is not due to simple provision of a longer time in mitosis. Thus, we concluded that the cdc5-11 mutant is impaired in proper microtubule dynamics and that provision of benomyl helps promote the microtubule function, and therefore cell growth, in a manner that requires a functional spindle checkpoint.

It has been shown that a signaling network known as the FEAR (cdc Fourteen Early Anaphase Release) network and its effector, Cdc14 phosphatase, play critical roles in spindle stability during anaphase (33, 42) and also in meiotic spindle disassembly (29). Since Cdc5 is also a component of the FEAR network (41), we tested whether the spindle defect in cdc5-11 is FEAR independent by providing the CDC14TAB6-1 allele, which is constitutively liberated from the Net1 tether at the nucleolus (38). Our results showed that provision of CDC14TAB6-1 moderately alleviated but did not completely remedy the cdc5-11 growth defect (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, the cdc5-11 CDC14TAB6-1 double mutant also grew significantly better than the corresponding CDC5 CDC14TAB6-1 cells in the presence of 15 μg/ml of benomyl (Fig. 2E). Taken together, these results suggest that cdc5-11 possesses a microtubule defect(s) that is independent of the FEAR network.

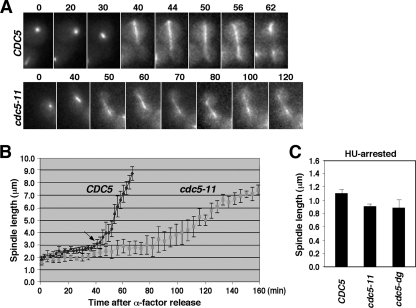

cdc5-11 is delayed in spindle growth, with a shorter spindle length.

The benomyl-remedial phenotype associated with the cdc5-11 mutation suggests that cdc5-11 is defective in proper microtubule function. Thus, we carried out time-lapse studies to closely monitor the microtubule growth as cells proceeded through the cell cycle. The results showed that wild-type CDC5 rapidly elongated spindles approximately 40 min (Fig. 3B) after release from the α-factor block (Fig. 3A and B). In contrast, cdc5-11 displayed significantly shorter spindle length from early in the cell cycle and grew at a significantly lower rate than the respective wild-type CDC5 (Fig. 3A and B). Direct measurement of the spindle length in hydroxyurea-arrested (S-phase) cells showed that the cdc5-11 mutant possessed spindles with an average length of 0.94 μm, whereas wild-type CDC5 displayed an average size of 1.14 μm (Fig. 3C). The heat-inducible degron mutant for Cdc5, cdc5-dg, also exhibited a significantly shorter spindle length (an average length of 0.88 μm) than the isogenic wild type (Fig. 3C). These observations suggest that Cdc5 is required for proper spindle elongation from early in the cell cycle.

FIG. 3.

cdc5-11 is severely retarded in spindle elongation. (A and B) Strains KLY2470 (CDC5) and KLY2466 (cdc5-11) were arrested in G1 with α-factor at 23°C and then released into fresh medium at 37°C. Under the same conditions, both CDC5 (n = 10) and cdc5-11 (n = 12) cells were monitored by time-lapse video microscopy as described in Materials and Methods. Representative cells for each strain are shown in panel A. The time is given in minutes after α-factor release (time = 0). Images acquired for wild-type CDC5 and the cdc5-11 mutant were then analyzed to determine the average spindle length at each time point (B). An arrow at the 40-min time point corresponds to a stage in which the wild-type CDC5 cells possess medium-size buds with a moderately elongated intranuclear spindle. The error bars indicate standard deviations. (C) Strains KLY2470, KLY2466, and KLY4208 (cdc5-dg) were arrested in S phase with hydroxyurea for 2 h, fixed, and then analyzed by confocal microscopy and Zeiss AIM software. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

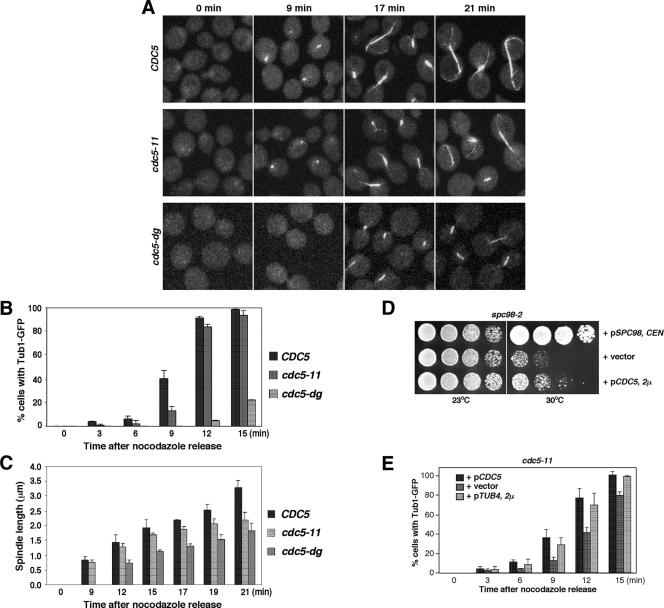

cdc5-11 is impaired in microtubule regrowth.

Next, we examined the capacity of cdc5-11 to regrow the microtubules after the spindles were depolymerized with nocodazole. As cells were released into fresh medium, samples were fixed for microscopic observation. Nine minutes after release from nocodazole, wild-type CDC5 regenerated the detectable size of spindles in 40% of the population (Fig. 4A and B). Under the same conditions, the cdc5-11 mutant regenerated discernible spindles in only 12% of the population, while the cdc5-dg mutant produced spindles at a much lower rate (Fig. 4A and B). Among the cells with detectable spindles, measurement of spindle length after nocodazole release revealed that both cdc5-11 and cdc5-dg possessed significantly shorter spindles than the isogenic wild type. At 21 min after release, wild-type CDC5 exhibited an average spindle length of 3.31 μm, whereas cdc5-11 and cdc5-dg displayed mean spindle lengths of 2.21 μm and 1.85 μm, respectively, at the same time point (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that Cdc5 is required for proper spindle nucleation or elongation, or both, and that cdc5-11 is defective in these events.

FIG. 4.

Cdc5 is required for proper spindle microtubule regrowth. (A to C) Strains KLY2470 (CDC5), KLY2466 (cdc5-11), and KLY4208 (cdc5-dg) were cultured at 23°C overnight. The cultures were then shifted to 37°C and treated with 15 μg/ml of nocodazole for 2 h before they were released into fresh medium. At the indicated time points, samples were harvested for confocal microscopy (A). Quantification of the cells with tubulin-GFP signals (B) and measurement of spindle length (C) were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. The error bars indicate standard deviations. (D) Strain KLY4440 (spc98-2) was transformed with the indicated constructs. The resulting transformants were cultured overnight, serially diluted, spotted onto YEP-glucose, and then incubated at the indicated temperatures. (E) Strain KLY2466 (cdc5-11) was transformed with the indicated plasmids. The transformants were selected and used for spindle regrowth assays as in panel A. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

To further investigate if Cdc5 plays an important role in microtubule function, we examined whether CDC5 genetically interacts with components important for microtubule nucleation. Overexpression of CDC5 partially remedied the growth defect associated with the spc98-2 mutation (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, as expected if Tub4 promotes Cdc5 function in microtubule nucleation, overexpression of TUB4 significantly enhanced the ability of the cdc5-11 mutant to regrow the spindles after release from nocodazole block (Fig. 4E; see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Both Cdc5 and Cdc28 activities are required for proper phosphorylation of Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2.

To provide new insights into the mechanism through which Cdc5 contributes to proper spindle function, we then examined whether Cdc5 can directly regulate any of the known components important for spindle function. To this end, cdc5Δ cells kept viable by the expression of a weakly functional cdc5-1 allele under the control of the GAL1 promoter were transformed with either control vector or a centromeric plasmid expressing wild-type CDC5 from its native promoter (pCDC5). Modification of various SPB or spindle-associated proteins (Nud1, Slk19, Stu2, Ase1, Spc97, Spc98, and Tub4) was then examined in the presence or absence of pCDC5. Among the components examined, we observed that modification of Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2 was greatly diminished upon depletion of Cdc5 activity (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Similar results were also observed when the cdc5-11 or cdc5-11 CDC14TAB6-1 mutant was shifted to the nonpermissive temperature (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). These findings suggest that Cdc5 is required for proper modification of Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2. It has been reported that the PBD of Plk1 binds to a phosphorylated epitope that is frequently primed by Cdk1 (10). In line with this view, modification of Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2 proteins also required proper Cdc28 activity (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material).

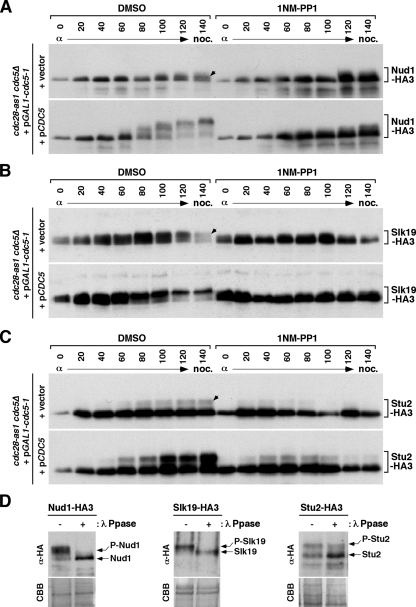

We then examined whether Cdc28 and Cdc5 activities cooperate to achieve maximal phosphorylation of Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2 in vivo. To this end, a cdc28-as1 cdc5Δ double mutant kept viable by the expression of the cdc5-1 allele under GAL1 promoter control was transformed with either a control vector or a centromeric pCDC5 to regulate Cdc5 activity. The kinase activity of cdc28-as1 was acutely inhibited by the cell-permeable inhibitor 4-amino-1-tert-butyl-3-(1-napthylmethyl) pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine) (1NM-PP1) (3). In the presence of both cdc28-as1 and Cdc5 activities, Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2 were efficiently modified to generate the slowly migrating forms as cells proceeded from G1 to M (Fig. 5A to C). Treatment of total cellular lysates with λ phosphatase eliminated or greatly reduced the slowly migrating forms (Fig. 5D), suggesting that these forms were generated through multiple phosphorylation events. In the absence of Cdc5, cdc28-as1 significantly induced the phosphorylated forms of Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2 (Fig. 5A to C). Inhibition of cdc28-as1 greatly diminished the levels of phosphorylation on these proteins (Fig. 5A to C; compare the dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]-treated samples with the 1NM-PP1-treated samples in the cells containing vector), suggesting that Cdc28 phosphorylates Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2 in vivo. Similarly, the presence of Cdc5 appeared to significantly increase the levels of phosphorylation on all of these proteins, which was further pronounced in the presence of cdc28-as1 activity (Fig. 5A to C). Taken together, these results suggest that Cdc28 and Cdc5 phosphorylate Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2, either cooperatively or independently, to achieve the maximal level of phosphorylation during mitosis.

FIG. 5.

Requirement for Cdc28 and Cdc5 for the modification of Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2. (A to C) Strains KLY5851 (NUD1-HA3) (A), KLY5824 (SLK19-HA3) (B), and KLY5839 (STU2-HA3) (C) were individually transformed with either pRS315 (control vector) or pKL743 (YCplac111-CDC5). The resulting transformants were cultured in YEP-galactose overnight and arrested in G1 by α-factor treatment. To deplete the weakly functional cdc5-1 under the control of the GAL1 promoter, the cells were then released into YEP-glucose medium containing nocodazole (noc.). Either control DMSO or 0.5 μM of 1NM-PP1 was added to the cultures 20 min after G1 release. Total cellular proteins were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for immunoblotting analysis with anti-HA antibody. The arrows indicate the Cdc28-dependent, but Cdc5-independent, slowly migrating form. (D) Strains KLY5851 (left), KLY5824 (middle), and KLY5839 (right) bearing pCDC5 (pKL743) were cultured as for panels A to C and then harvested after being released into nocodazole-containing medium for 140 min. Total cellular lysates were prepared, either treated with λ-phosphatase or left untreated, and then subjected to immunoblotting analyses. Subsequently, the same membranes were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) for loading controls.

DISCUSSION

cdc5-11 is defective in proper spindle function.

A growing body of evidence suggests that the function of polo kinase in bipolar spindle assembly is conserved throughout evolution. However, the mechanism through which Plk1 contributes to microtubule function has been elusive. More direct evidence for the involvement of polo kinase in regulating microtubule function came from the work of de Carcer et al., which demonstrated that provision of active recombinant Drosophila Polo rescues impaired microtubule nucleation activity of the salt-stripped centrosomes in vitro (9). Other studies showed that Plk1 phosphorylates and decreases the microtubule-stabilizing activity of TCTP, an event thought to promote microtubule dynamics during anaphase (48). The Xenopus polo kinase homolog Plx1 has also been shown to phosphorylate Stathmin/Op18 and to stabilize microtubules by negatively regulating the microtubule-destabilizing activity of the latter (4). Although how these seemingly disparate events are coordinated during cell cycle progression is not clearly understood, these observations suggest that Plk1 and its homologs in various organisms regulate the microtubule dynamics by either positively or negatively regulating various components associated with microtubules.

In an effort to better understand the role of polo kinase in microtubule function, we generated and characterized a budding yeast polo kinase, cdc5-11 mutant. Our results showed that the cdc5-11 mutant exhibited a temperature-sensitive growth defect, with a substantial fraction (∼25%) of the mutants displaying improper spindle structures. Several lines of evidence suggest that the observed spindle defect is a consequence of the cdc5-11 mutation. First, provision of benomyl, which diminished the viability of the isogenic wild type, dramatically enhanced cdc5-11 viability at a semipermissive temperature. Second, as expected if the intrinsic spindle defect exists in cdc5-11, loss of MAD2 caused significant deterioration in the growth of cdc5-11, but not in that of the corresponding CDC5 wild type. Third, the cdc5-11 mutant appeared to be defective in microtubule dynamics and exhibited significantly slower microtubule nucleation and spindle growth than the isogenic wild type. Tests of other available cdc5 mutants revealed that, except for cdc5-3, which is defective in the Swe1 regulatory pathway (31), many cdc5 mutants also possess various degrees of the benomyl-remedial growth defect (see Fig. S6A in the supplemental material). Furthermore, a cdc5 mutant that displays tethered Cdc5 populations at the SPB and the bud neck (cdc5Δ bearing pCDC5ΔC-CNM67 and pCDC5ΔC-CDC12) (32) exhibited benomyl-dependent growth enhancement (see Fig. S6B in the supplemental material), suggesting that normal localization of Cdc5 to the nucleus and spindles is important for proper microtubule function. Examination of the temperature-sensitive cdc5-dg mutant exhibited a much more drastic defect in spindle nucleation and growth, although how much of this defect is directly attributable to the other Cdc5 depletion-induced mitotic defects is difficult to assess.

Regulation of Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2 by Cdc28 and Cdc5.

Although it is widely appreciated that polo kinase is required for proper bipolar spindle assembly in various organisms, the underlying mechanism through which polo kinase contributes to the spindle function is still largely elusive. In an effort to identify potential Cdc5 targets that are important for Cdc5-mediated spindle regulation, we examined whether Cdc5 activity is required for proper modification of some of the previously characterized components critical for spindle function. Among the components that we examined, we observed that proper modification of Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2 requires Cdc5 function in vivo (see Fig. S3 and S4 in the supplemental material). Cdc5 also phosphorylated these proteins in vitro (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material), raising the possibility that Cdc5 directly phosphorylates and regulates the proteins.

It has been shown that Nud1 localizes at the SPB and plays a critical role in coordinating cytoplasmic microtubule organization with mitotic exit (13). Slk19 is a component of the FEAR network (41, 49) and translocates from the kinetochores to the spindle midzone during anaphase, an event that is critical for the stability of the anaphase spindle (42). Stu2 localizes to the spindles, SPBs, and cytoplasmic microtubules (21) and appears to be required for mitotic spindle elongation and microtubule dynamics by destabilizing the plus ends in vivo (36, 45). Thus, although further studies are required to better understand the mechanism through which Cdc5 contributes to the regulation of Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2, the distinct functions of these proteins at multiple subcellular locations help explain the complexity of the spindle defect associated with the cdc5-11 mutation.

A growing body of evidence suggests that Cdk1-dependent phosphorylation onto a protein functions as a docking site for the subsequent PBD-dependent Plk1 function (28). Consistent with this model, acute inhibition of the Cdc28 activity drastically diminished the levels of Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2 modifications (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material) and appeared to lessen the Cdc5-dependent modification of these proteins in vivo (Fig. 5). Cdc28 also phosphorylated Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2 in vitro (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material), suggesting that Cdc28 directly regulates these proteins. It should be noted, however, that Cdc5 is a substrate of the anaphase-promoting complex-Cdh1 complex (7), which is negatively regulated by Cdc28 (18). In agreement with this observation, inhibition of cdc28-as1 with 1NM-PP1 significantly downregulated the Cdc5 level (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material), thus raising the possibility that the diminished levels of Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2 phosphorylation in the 1NM-PP1-treated cells were in part due to the decreased amount of Cdc5. Nevertheless, Cdc28 appeared to induce the phosphorylated forms of Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2 even in the absence of Cdc5 (Fig. 5A to C), suggesting a direct role of Cdc28 in regulating these proteins. In support of this view, both Slk19 and Stu2 possess a potential PBD-binding S-pT/pS-P motif (the S189 residue for Slk19 and the S603 residue for Stu2) and GST-fused PBD, but not the corresponding PBD H538A K540M (PBD/AM) phospho-Ser/Thr pincer mutant (10), bound to phosphorylated Stu2 (see Fig. S9A in the supplemental material). (Our attempt to detect the interaction between the PBD and the phosphorylated form of Slk19 was hampered by the unstable nature of the latter protein.) Furthermore, Cdc5 efficiently induced Stu2 modification only in the presence of Cdc28 activity (see Fig. S9B in the supplemental material). The cdc5(W517F V518A L530A) mutant, which exhibits a crippled PBD function (40), or the cdc5(N209A) mutant, which lacks the kinase activity (8), failed to induce this modification (see Fig. S9C in the supplemental material). These observations suggest that the Cdc28-dependent phosphorylation onto Stu2 promotes the Stu2-Cdc5 interaction through the PBD and that this step is critical for subsequent Cdc5-dependent Stu2 phosphorylation. However, it should be noted that vertebrate Cdc25C, whose PBD docking site is normally generated by Cdc2 prior to the G2/M transition (10), can be directly phosphorylated and activated by the Xenopus polo-like kinase homolog Plx1 in vitro (22), suggesting the existence of phosphorylation-independent interaction between the polo-like kinase and its substrates. Taken in aggregate, our results suggest that Cdc28 and Cdc5 phosphorylate and regulate the functions of Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2 either cooperatively or independently. Determination of the Cdc28- and Cdc5-dependent phosphorylation sites on these proteins and further investigation of the significance of each phosphorylation event are likely critical to better understand the underlying mechanism through which Cdc28 and Cdc5 regulate the microtubule function.

Potential polo kinase substrates in vertebrates.

Studies of potential polo kinase substrates in a genetically amenable budding yeast organism may allow us to better understand the mechanism through which vertebrate polo kinases regulate various spindle functions. In this regard, it is noteworthy that Nud1 exhibits a limited homology with human Centriolin, which is important for cytoplasmic microtubule organization and the late cytokinetic events (12). This observation hints that some of the functions of Nud1 and Centriolin are conserved throughout evolution. Slk19 is the budding yeast member of the human TACC (transforming acidic coiled-coil) family of proteins, whose deregulation has been implicated in the development of certain types of human cancers (35). Like Slk19, TACC proteins participate in controlling mitotic spindle dynamics. In addition, Stu2 belongs to the XMAP215/Dis1 MAP family (19), which regulates microtubule plus-end assembly, microtubule nucleation, and anchorage to the centrosomes. The human homolog of this family, TOGp, has also been isolated and appears to stimulate bipolar spindle assembly (6), although how it is regulated is not known. Providing that Cdc28 and Cdc5 directly phosphorylate Nud1, Slk19, and Stu2, it will be interesting to further investigate whether Cdk1 and polo kinase cooperatively regulate the functions of these higher-eukaryotic homologs in their respective organisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Susan Garfield for technical support and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by NCI intramural grants (K.S.L. and J.G.M.), an NCI fund under contract N01-CO-12400 (T.D.V.), and NIH grant R01 GM040479 (T.C.H.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 January 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asano, S., J. E. Park, K. Sakchaisri, L. R. Yu, S. Song, P. Supavilai, T. D. Veenstra, and K. S. Lee. 2005. Concerted mechanism of Swe1/Wee1 regulation by multiple kinases in budding yeast. EMBO J. 242194-2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr, F. A., H. H. Sillje, and E. A. Nigg. 2004. Polo-like kinases and the orchestration of cell division. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5429-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop, A. C., K. Shah, Y. Liu, L. Witucki, C. Kung, and K. M. Shokat. 1998. Design of allele-specific inhibitors to probe protein kinase signaling. Curr. Biol. 8257-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budde, P. P., A. Kumagai, W. G. Dunphy, and R. Heald. 2001. Regulation of Op18 during spindle assembly in Xenopus egg extracts. J. Cell Biol. 153149-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casenghi, M., P. Meraldi, U. Weinhart, P. I. Duncan, R. Korner, and E. A. Nigg. 2003. Polo-like kinase 1 regulates Nlp, a centrosome protein involved in microtubule nucleation. Dev. Cell 5113-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassimeris, L., and J. Morabito. 2004. TOGp, the human homolog of XMAP215/Dis1, is required for centrosome integrity, spindle pole organization, and bipolar spindle assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 151580-1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charles, J. F., S. L. Jaspersen, R. L. Tinker-Kulberg, L. Hwang, A. Szidon, and D. O. Morgan. 1998. The Polo-related kinase Cdc5 activates and is destroyed by the mitotic cyclin destruction machinery in S. cerevisiae. Curr. Biol. 8497-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng, L., L. Hunke, and C. F. J. Hardy. 1998. Cell cycle regulation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae polo-like kinase Cdc5p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 187360-7370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Carcer, G., M. do Carmo-Avides, M. J. Lallena, D. M. Glover, and C. Gonzalez. 2001. Requirement of Hsp90 for centrosomal function reflects its regulation of polo kinase stability. EMBO J. 202878-2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elia, A. E., P. Rellos, L. F. Haire, J. W. Chao, F. J. Ivins, K. Hoepker, D. Mohammad, L. C. Cantley, S. J. Smerdon, and M. B. Yaffe. 2003. The molecular basis for phospho-dependent substrate targeting and regulation of Plks by the polo-box domain. Cell 11583-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gietz, R. D., and A. Sugnino. 1988. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene 74527-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gromley, A., A. Jurczyk, J. Sillibourne, E. Halilovic, M. Mogensen, I. Groisman, M. Blomberg, and S. Doxsey. 2003. A novel human protein of the maternal centriole is required for the final stages of cytokinesis and entry into S phase. J. Cell Biol. 161535-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gruneberg, U., K. Campbell, C. Simpson, J. Grindlay, and E. Schiebel. 2000. Nud1p links astral microtubule organization and the control of exit from mitosis. EMBO J. 196475-6488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill, J. E., A. M. Myers, T. J. Koerner, and A. Tzagoloff. 1993. Yeast/E. coli shuttle vectors with multiple unique restriction sites. Yeast 2163-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu, F., Y. Wang, D. Liu, Y. Li, J. Qin, and S. J. Elledge. 2001. Regulation of the Bub2/Bfa1 GAP complex by Cdc5 and cell cycle checkpoints. Cell 107655-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hudson, J. W., A. Kozarova, P. Cheung, J. C. Macmillan, C. J. Swallow, J. C. Cross, and J. W. Dennis. 2001. Late mitotic failure in mice lacking Sak, a polo-like kinase. Curr. Biol. 11441-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito, H., Y. Fukuda, K. Murata, and A. Kimura. 1983. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J. Bacteriol. 153163-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaspersen, S. L., J. F. Charles, and D. O. Morgan. 1999. Inhibitory phosphorylation of the APC regulator Hct1 is controlled by the kinase Cdc28 and the phosphatase Cdc14. Curr. Biol. 9227-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinoshita, K., B. Habermann, and A. A. Hyman. 2002. XMAP215: a key component of the dynamic microtubule cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 12267-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitada, K., A. L. Johnson, L. H. Johnston, and A. Sugino. 1993. A multicopy suppressor gene of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae G1 cell cycle mutant gene dbf4 encodes a protein kinase and is identified as CDC5. Mol. Cell. Biol. 134445-4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kosco, K. A., C. G. Pearson, P. S. Maddox, P. J. Wang, I. R. Adams, E. D. Salmon, K. Bloom, and T. C. Huffaker. 2001. Control of microtubule dynamics by Stu2p is essential for spindle orientation and metaphase chromosome alignment in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 122870-2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumagai, A., and W. G. Dunphy. 1996. Purification and molecular cloning of Plx1, a Cdc25-regulatory kinase from Xenopus egg extracts. Science 2731377-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lane, H. A., and E. A. Nigg. 1996. Antibody microinjection reveals an essential role for human polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) in the functional maturation of mitotic centrosomes. J. Cell Biol. 1351701-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, K. S., and R. L. Erikson. 1997. Plk is a functional homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cdc5, and elevated Plk activity induces multiple septation structures. Mol. Cell. Biol. 173408-3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, K. S., T. Z. Grenfell, F. R. Yarm, and R. L. Erikson. 1998. Mutation of the polo-box disrupts localization and mitotic functions of the mammalian polo kinase Plk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 959301-9306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Llamazares, S., A. Moreira, A. Tavares, C. Girdham, B. A. Spruce, C. Gonzalez, R. E. Karess, D. M. Glover, and C. E. Sunkel. 1991. polo encodes a protein kinase homolog required for mitosis in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 52153-2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowery, D. M., D. Lim, and M. B. Yaffe. 2005. Structure and function of polo-like kinases. Oncogene 24248-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marston, A. L., B. H. Lee, and A. Amon. 2003. The Cdc14 phosphatase and the FEAR network control meiotic spindle disassembly and chromosome segregation. Dev. Cell 4711-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohkura, H., I. M. Hagan, and D. M. Glover. 1995. The conserved Schizosaccharomyces pombe kinase plo1, required to form a bipolar spindle, the actin ring, and septum, can drive septum formation in G1 and G2 cells. Genes Dev. 91059-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park, C. J., S. Song, P. R. Lee, W. Shou, R. J. Deshaies, and K. S. Lee. 2003. Loss of CDC5 function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae leads to defects in Swe1p regulation and Bfa1p/Bub2p-independent cytokinesis. Genetics 16321-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park, J.-E., C. J. Park, K. Sakchaisri, T. Karpova, S. Asano, J. McNally, Y. Sunwoo, S.-H. Leem, and K. S. Lee. 2004. Novel functional dissection of the localization-specific roles of budding yeast polo kinase Cdc5p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 249873-9886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pereira, G., and E. Schiebel. 2003. Separase regulates INCENP-Aurora B anaphase spindle function through Cdc14. Science 3022120-2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qian, Y. W., E. Erikson, C. Li, and J. L. Maller. 1998. Activated polo-like kinase Plx1 is required at multiple points during mitosis in Xenopus laevis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 184262-4271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raff, J. W. 2002. Centrosomes and cancer: lessons from a TACC. Trends Cell Biol. 12222-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Severin, F., B. Habermann, T. Huffaker, and T. Hyman. 2001. Stu2 promotes mitotic spindle elongation in anaphase. J. Cell Biol. 153435-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherman, F., G. R. Fink, and J. B. Hicks. 1986. Laboratory course manual for methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 38.Shou, W., J. H. Seol, A. Shevchenko, C. Baskerville, D. Moazed, Z. W. Chen, J. Jang, A. Shevchenko, H. Charbonneau, and R. J. Deshaies. 1999. Exit from mitosis is triggered by Tem1-dependent release of the protein phosphatase Cdc14 from nucleolar RENT complex. Cell 97233-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 12219-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song, S., T. Z. Grenfell, S. Garfield, R. L. Erikson, and K. S. Lee. 2000. Essential function of the polo box of Cdc5 in subcellular localization and induction of cytokinetic structures. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20286-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stegmeier, F., R. Visintin, and A. Amon. 2002. Separase, polo kinase, the kinetochore protein Slk19, and Spo12 function in a network that controls Cdc14 localization during early anaphase. Cell 108207-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sullivan, M., C. Lehane, and F. Uhlmann. 2001. Orchestrating anaphase and mitotic exit: separase cleavage and localization of Slk19. Nat. Cell Biol. 3771-777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sundberg, H. A., and T. N. Davis. 1997. A mutational analysis identifies three functional regions of the spindle pole component Spc110p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 82575-2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sunkel, C. L., and D. M. Glover. 1988. polo, a mitotic mutant of Drosophila displaying abnormal spindle poles. J. Cell Sci. 8925-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Breugel, M., D. Drechsel, and A. Hyman. 2003. Stu2p, the budding yeast member of the conserved Dis1/XMAP215 family of microtubule-associated proteins, is a plus end-binding microtubule destabilizer. J. Cell Biol. 161359-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van de Weerdt, B. C., and R. H. Medema. 2006. Polo-like kinases: a team in control of the division. Cell Cycle 5853-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waddle, J. A., T. S. Karpova, R. H. Waterston, and J. A. Cooper. 1996. Movement of cortical actin patches in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 132861-870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yarm, F. R. 2002. Plk phosphorylation regulates the microtubule-stabilizing protein TCTP. Mol. Cell. Biol. 226209-6221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeng, X., J. A. Kahana, P. A. Silver, M. K. Morphew, J. R. McIntosh, I. T. Fitch, J. Carbon, and W. S. Saunders. 1999. Slk19p is a centromere protein that functions to stabilize mitotic spindles. J. Cell Biol. 146415-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.