Abstract

The fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans regulates its polysaccharide capsule depending on environmental stimuli. To investigate whether capsule polymers change under different growth conditions, we analyzed shed capsules at physiological concentrations without physical perturbation. Our results indicate that regulation of capsule size is mediated at the level of individual polysaccharide molecules.

Cryptococcus neoformans is an encapsulated yeast that causes serious opportunistic infections. The major virulence factor of this pathogen is its polysaccharide capsule. This material is antiphagocytic and has immunomodulatory effects (15, 19, 33); it surrounds the cell and is constitutively shed into the surroundings. The major component of cryptococcal capsule is glucuronoxylomannan (GXM), a linear, high-molecular-weight polysaccharide. Imaging studies indicate that the capsule is composed of a meshwork of fibers (25, 29-31) which varies in density with distance from the cell wall (8) and with growth conditions (25). The thickness of the capsule exceeds the calculated length of individual GXM fibers (17).

C. neoformans capsule volume responds to environmental factors, including iron levels and CO2 concentrations (9, 14, 32). Although signaling pathways involved in capsule variation have been investigated (1, 5, 12, 35), how the physical changes occur is poorly understood. Factors that contribute to larger capsules are likely to be complex: they may include greater production and/or secretion of polysaccharides, more extensive polysaccharide assembly, decreased capsule shedding, and synthesis of structurally altered or larger polysaccharide molecules. To test the hypothesis that regulation of capsule size is mediated at the level of individual polysaccharide molecules, we investigated shed GXM. We detected this material using a monoclonal antibody to GXM that specifically binds both shed material (described below) and cryptococcal capsules on live cells (8).

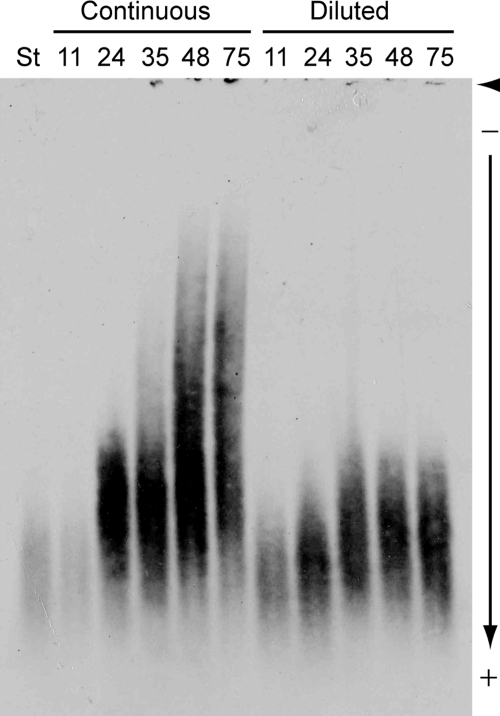

We observed that when JEC21 (wild type, serotype D) cells were grown to late stationary phase in rich medium (YPD; 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose), a subpopulation displayed larger capsules. To test whether the properties of shed GXM changed during this growth, we diluted JEC21 cells from a starter culture into duplicate flasks (50 ml YPD; 106 cells/ml) and incubated them with shaking at 30°C. At intervals we drew a 0.5-ml sample from each flask, counted cells, and diluted one culture (“diluted culture”) to the starting density, while the other was cultured continuously (“continuous culture”). To examine GXM, we subjected samples of culture supernatant fluid to electrophoresis on an agarose gel. The gel was transferred onto a Nytran SuPerCharge (Whatman) membrane using DNA blotting methods (3), and the membrane was air dried, blocked with 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline, probed with an anti-GXM monoclonal antibody followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Sigma), and developed with a chemiluminescent reagent (Perkin Elmer). The electromobility of shed GXM dramatically decreased as the continuous culture aged (Fig. 1). In contrast, there was little change in GXM migration when the culture was periodically diluted (Fig. 1), and the modest differences observed were not consistent between experiments (data not shown). We also noticed that average capsule thickness in the continuous culture doubled between 11 and 48 h, while that of the diluted culture remained nearly constant over the same interval (Table 1); this led to a marked difference in average capsule size between the two cultures (Table 1; P < 0.0001 at 48 h). For the continuous culture, no capsules with a radius above 3 μm (triple the size of capsules in the starting culture) were present at 0 or 11 h, but cells with these capsules comprised 19% of the population at 24 and 35 h and 40% of the population at 48 and 75 h. The very largest capsules (>4.5 μm) were only observed at the last two time points.

FIG. 1.

Electromobility of shed GXM from JEC21 cells changes over time in rich medium. All samples were heated (15 min at 70°C) to denature enzymes, centrifuged (16,000 × g for 3 min) to separate supernatant and cells, and stored at 4°C. Samples (15 μl) of culture supernatants were mixed with 6× DNA loading dye (4), loaded on a 0.6% certified megabase agarose (Bio-Rad) gel, and subjected to electrophoresis (15 h at 25 V) in 0.5× TBE (44.5 mM Tris base, 44.5 mM boric acid, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.3). Samples containing more GXM (later time points) were diluted in distilled water based on a pilot gel, as sample normalization based on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay determination of GXM concentration (23) did not yield equal blot intensity. (This may reflect changes over time in GXM antibody reactivity [7, 11, 18] and/or transfer efficiency.) The gel was transferred onto a positively charged nylon membrane and immunoblotted with 1 μg/ml anti-GXM antibody 3C2 as described in the text. Initial sample heating and dilution in distilled water did not alter electrophoretic migration (data not shown). St, starter culture (at 1.6 × 107 cells/ml); arrowhead, well position; arrow, direction of migration; other numbers, sampling time (hours) after the start of the experiment.

TABLE 1.

Cell density and capsule thickness in continuous and diluted cultures

| Hour | Continuous culture

|

Diluted culture

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell densitya | Capsule thicknessb | Cell density | Capsule thickness | |

| 11 | 9.1 × 107 | 0.80 ± 0.03 | 9.1 × 107 | 0.80 ± 0.03 |

| 24 | 1.5 × 108 | 1.35 ± 0.06 | 8.6 × 107 | 0.90 ± 0.02 |

| 35 | 1.8 × 108 | 1.37 ± 0.07 | 6.4 × 107 | 0.82 ± 0.03 |

| 48 | 2.1 × 108 | 1.60 ± 0.19 | 1.0 × 108 | 1.02 ± 0.05 |

| 75 | 4.3 × 108 | 1.54 ± 0.08 | 1.7 × 108 | 0.93 ± 0.02 |

Cell density at the indicated time of growth (cells/ml), determined by counting cells on a hemocytometer.

Capsule thickness of India-ink-stained cells, measured using an Axioskop 2 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss). The averages ± standard errors of the means (μm) of 50 cells for each time point are tabulated.

We considered several explanations for the changes in GXM. First, increasing concentrations of capsule components in the medium over time could lead to self-association of capsule polysaccharides (24) and corresponding reduced mobility. Alternatively, the cells could be producing altered GXM of lower mobility, due to an increase in polymer length, a difference in substitution or structure, covalent cross-linking, and/or association with other macromolecules. Such alterations could potentially be stimulated by increased cell density and/or reduced nutrients in the continuous culture.

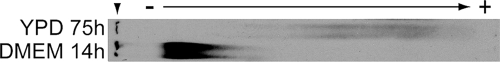

To further investigate the relationship between capsule size and the electromobility of shed GXM, we tested whether known capsule-inducing conditions (9, 32, 38, 39) affected GXM gel migration. We chose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) plus CO2 (9) for these studies, as it yielded the most-consistent capsule induction for JEC21. A starter culture of JEC21 was grown in YPD, washed in DMEM, resuspended in DMEM at 106 cells/ml, and incubated for 14 h in the presence of 5% CO2. The electromobility of the GXM shed from cells grown in this medium was significantly lower than that of GXM from any YPD-grown samples (Fig. 2). We considered the possibility that this change represented self-association of GXM, perhaps involving divalent cations (24). However, migration was not altered by dialysis of the sample against water or 10 mM EDTA (data not shown). Moreover, the GXM concentrations in supernatants from the DMEM-induced overnight cultures were <10 μg/ml by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (23), a value substantially below those of the concentrated GXM preparations reported to initiate self-aggregation (24).

FIG. 2.

GXM shed from cells grown under capsule-inducing conditions displays electrophoretic mobility that is lower than that for cells grown in rich medium. Cultures of JEC21 cells were grown overnight and then washed and diluted to 106 cells/ml for continuous growth as indicated, followed by analysis of GXM as described for Fig. 1 (lanes rotated 90 degrees counterclockwise). Top lane, cells grown in YPD for 75 h, to a final concentration of 4 × 108 cells/ml; bottom lane, cells grown in DMEM (Sigma catalog no. D5796) in the presence of 5% CO2 at 30°C for 14 h, to a final concentration of 1.6 × 106 cells/ml. Note that the growth conditions for the YPD sample, 75 h of continuous growth, correspond to those that yielded the slowest-migrating material in Fig. 1.

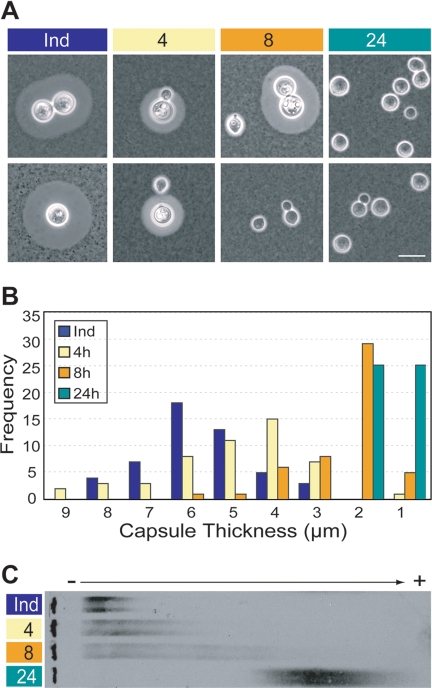

These capsule induction studies supported our observations of the correlation between capsule size and GXM electromobility and further suggested that changes in the latter were not related to high cell density, as cells grow very slowly in DMEM (see Fig. 2 legend). To further investigate the changes in GXM, we next examined capsule-induced cells that were washed and returned to YPD. By 4 h after the medium change, the induced cells were budding daughter cells with small capsules (Fig. 3A, lane 4), and by 8 h those daughter cells began to bud (Fig. 3A, lane 8). By 24 h over 98% of the cells in the culture had small capsules, although a few of the originally induced cells could be observed (Fig. 3A, lane 24; also data not shown). Capsule size distributions for each time point reflect this progression (Fig. 3B). Notably, the migration of shed GXM increased coordinately with the fraction of cells with small capsules (Fig. 3C), further demonstrating the relationship between capsule size and the electromobility of shed GXM. It is striking that in this experiment GXM mobility increased as the culture aged, the reverse of the pattern in Fig. 1. This shows that reduced GXM electromobility is not related to the effects of long-term culture, including increased GXM concentration in the medium, higher cell density, and reduced nutrient availability. All of our studies use minimally processed samples of capsule materials shed in a physiological manner, with GXM concentrations between 0.2 to 200 μg/ml (in the range of those reported in human infections [6]). The results are therefore likely to represent a biologically relevant GXM change. Together, our data suggest that less-encapsulated cells produce a polymer that is fundamentally altered compared to that made by highly encapsulated cells. The simplest hypothesis is that this polymer is of reduced length, but changes in substitution, covalent cross-linking, or other factors could also play a role. The differences we observe in GXM are independent of residence time at the cell surface, as the GXM from mutant cells which shed this polymer but cannot bind it to the cell wall (ags1 [27]) migrates like that of the wild type (data not shown). They are also unlikely to reflect noncovalent self-association.

FIG. 3.

Capsule size correlates with the electromobility of shed GXM. Capsule-induced JEC21 cells were washed and resuspended in YPD, and samples were taken at 4, 8, and 24 h after the medium change. (A) Two representative micrographs of cells at each time point, imaged as described in Table 1; scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Capsule thickness of 50 cells was measured as in Table 1, with frequency plotted as a histogram (bin width equals 1 μm with the bin maxima indicated on the abscissa, in decreasing order). (C) Electromobility of shed GXM, analyzed as described for Fig. 1. Ind, original induced sample; 4, 8, and 24 indicate hours after medium change.

Our results from JEC21 cells strongly support the hypothesis that modification of GXM molecules plays a central role in determining C. neoformans capsule size. This is a novel explanation for the observed changes in C. neoformans capsule size, although it echoes themes in studies of bacterial and mammalian polysaccharides (26, 34, 36). Further, it is consistent with all of the current models of capsule construction (8, 16, 25, 28, 37, 40). Future studies incorporating additional strains and mutants with altered capsule synthesis or binding characteristics (2, 10, 13, 20-22, 27) will further elucidate the relationship between shed and bound GXM and how C. neoformans synthesizes and regulates its polysaccharide capsule.

Acknowledgments

We thank Morgann Reilly, Andrew Kau, Stacey Klutts, and Indrani Bose for helpful discussion, Thomas Kozel and Arturo Casadevall for anti-GXM antibodies, and Jennifer Lodge for the C. neoformans strain.

This work was supported by NIH awards GM71007 and AI073380 to T.L.D.

A.Y. was partially supported by a Berg/Morse Fellowship from the Department of Molecular Microbiology.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bahn, Y. S., K. Kojima, G. M. Cox, and J. Heitman. 2005. Specialization of the HOG pathway and its impact on differentiation and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Biol. Cell 162285-2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bar-Peled, M., C. L. Griffith, J. J. Ory, and T. L. Doering. 2004. Biosynthesis of UDP-GlcA, a key metabolite for capsular polysaccharide synthesis in the pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Biochem. J. 381131-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, T. 1999. Southern blotting, p. 2.9.9-2.9.10. In F. M. Ausubel, R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology, vol. 1. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 2007. DNA loading buffer (6X). CSH Protocols. doi: 10.1101/pdb.rec11045. [DOI]

- 5.Cramer, K. L., Q. D. Gerrald, C. B. Nichols, M. S. Price, and J. A. Alspaugh. 2006. Transcription factor Nrg1 mediates capsule formation, stress response, and pathogenesis in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell 51147-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deshaw, M., and L. A. Pirofski. 1995. Antibodies to the Cryptococcus neoformans capsular glucuronoxylomannan are ubiquitous in serum from HIV+ and HIV− individuals. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 99425-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Hermoso, D., F. Dromer, and G. Janbon. 2004. Cryptococcus neoformans capsule structure evolution in vitro and during murine infection. Infect. Immun. 723359-3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gates, M. A., P. Thorkildson, and T. R. Kozel. 2004. Molecular architecture of the Cryptococcus neoformans capsule. Mol. Microbiol. 5213-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Granger, D. L., J. R. Perfect, and D. T. Durack. 1985. Virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Regulation of capsule synthesis by carbon dioxide. J. Clin. Investig. 76508-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffith, C. L., J. S. Klutts, L. Zhang, S. B. Levery, and T. L. Doering. 2004. UDP-glucose dehydrogenase plays multiple roles in the biology of the pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Biol. Chem. 27951669-51676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerrero, A., N. Jain, D. L. Goldman, and B. C. Fries. 2006. Phenotypic switching in Cryptococcus neoformans. Microbiology 1523-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu, G., B. R. Steen, T. Lian, A. P. Sham, N. Tam, K. L. Tangen, and J. W. Kronstad. 2007. Transcriptional regulation by protein kinase A in Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Pathog. 3e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janbon, G., U. Himmelreich, F. Moyrand, L. Improvisi, and F. Dromer. 2001. Cas1p is a membrane protein necessary for the O-acetylation of the Cryptococcus neoformans capsular polysaccharide. Mol. Microbiol. 42453-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung, W. H., A. Sham, R. White, and J. W. Kronstad. 2006. Iron regulation of the major virulence factors in the AIDS-associated pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Biol. 4e410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kozel, T. R., and R. P. Mastroianni. 1976. Inhibition of phagocytosis by cryptococcal polysaccharide: dissociation of the attachment and ingestion phases of phagocytosis. Infect. Immun. 1462-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McFadden, D., O. Zaragoza, and A. Casadevall. 2006. The capsular dynamics of Cryptococcus neoformans. Trends Microbiol. 14497-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McFadden, D. C., M. De Jesus, and A. Casadevall. 2006. The physical properties of the capsular polysaccharides from Cryptococcus neoformans suggest features for capsule construction. J. Biol. Chem. 2811868-1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McFadden, D. C., B. C. Fries, F. Wang, and A. Casadevall. 2007. Capsule structural heterogeneity and antigenic variation in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell 61464-1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell, T. G., and L. Friedman. 1972. In vitro phagocytosis and intracellular fate of variously encapsulated strains of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 5491-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moyrand, F., Y. C. Chang, U. Himmelreich, K. J. Kwon-Chung, and G. Janbon. 2004. Cas3p belongs to a seven-member family of capsule structure designer proteins. Eukaryot. Cell 31513-1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moyrand, F., T. Fontaine, and G. Janbon. 2007. Systematic capsule gene disruption reveals the central role of galactose metabolism on Cryptococcus neoformans virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 64771-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moyrand, F., B. Klaproth, U. Himmelreich, F. Dromer, and G. Janbon. 2002. Isolation and characterization of capsule structure mutant strains of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 45837-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukherjee, S., and A. Casadevall. 1995. Sensitivity of sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Cryptococcus neoformans polysaccharide antigen is dependent on the isotypes of the capture and detection antibodies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33765-768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nimrichter, L., S. Frases, L. P. Cinelli, N. B. Viana, A. Nakouzi, L. R. Travassos, A. Casadevall, and M. L. Rodrigues. 2007. Self-aggregation of Cryptococcus neoformans capsular glucuronoxylomannan is dependent on divalent cations. Eukaryot. Cell 61400-1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierini, L. M., and T. L. Doering. 2001. Spatial and temporal sequence of capsule construction in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 41105-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pummill, P. E., A. M. Achyuthan, and P. L. DeAngelis. 1998. Enzymological characterization of recombinant xenopus DG42, a vertebrate hyaluronan synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 2734976-4981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reese, A. J., A. Yoneda, J. A. Breger, A. Beauvais, H. Liu, C. L. Griffith, I. Bose, M. J. Kim, C. Skau, S. Yang, J. A. Sefko, M. Osumi, J. P. Latge, E. Mylonakis, and T. L. Doering. 2007. Loss of cell wall alpha(1-3) glucan affects Cryptococcus neoformans from ultrastructure to virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 631385-1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodrigues, M. L., L. Nimrichter, D. L. Oliveira, S. Frases, K. Miranda, O. Zaragoza, M. Alvarez, A. Nakouzi, M. Feldmesser, and A. Casadevall. 2007. Vesicular polysaccharide export in Cryptococcus neoformans is a eukaryotic solution to the problem of fungal trans-cell wall transport. Eukaryot. Cell 648-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakaguchi, N., T. Baba, M. Fukuzawa, and S. Ohno. 1993. Ultrastructural study of Cryptococcus neoformans by quick-freezing and deep-etching method. Mycopathologia 121133-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeo, K., I. Uesaka, K. Uehira, and M. Nishiura. 1973. Fine structure of Cryptococcus neoformans grown in vitro as observed by freeze-etching. J. Bacteriol. 1131442-1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takeo, K., I. Uesaka, K. Uehira, and M. Nishiura. 1973. Fine structure of Cryptococcus neoformans grown in vivo as observed by freeze-etching. J. Bacteriol. 1131449-1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vartivarian, S. E., E. J. Anaissie, R. E. Cowart, H. A. Sprigg, M. J. Tingler, and E. S. Jacobson. 1993. Regulation of cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide by iron. J. Infect. Dis. 167186-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vecchiarelli, A. 2000. Immunoregulation by capsular components of Cryptococcus neoformans. Med. Mycol. 38407-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ventura, C. L., R. T. Cartee, W. T. Forsee, and J. Yother. 2006. Control of capsular polysaccharide chain length by UDP-sugar substrate concentrations in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 61723-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xue, C., Y. S. Bahn, G. M. Cox, and J. Heitman. 2006. G protein-coupled receptor Gpr4 senses amino acids and activates the cAMP-PKA pathway in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Biol. Cell 17667-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamada, S., M. Busse, M. Ueno, O. G. Kelly, W. C. Skarnes, K. Sugahara, and M. Kusche-Gullberg. 2004. Embryonic fibroblasts with a gene trap mutation in Ext1 produce short heparan sulfate chains. J. Biol. Chem. 27932134-32141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoneda, A., and T. L. Doering. 2006. A eukaryotic capsular polysaccharide is synthesized intracellularly and secreted via exocytosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 175131-5140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zaragoza, O., and A. Casadevall. 2004. Experimental modulation of capsule size in Cryptococcus neoformans. Biol. Proced. Online 610-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaragoza, O., B. C. Fries, and A. Casadevall. 2003. Induction of capsule growth in Cryptococcus neoformans by mammalian serum and CO2. Infect. Immun. 716155-6164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zaragoza, O., A. Telzak, R. A. Bryan, E. Dadachova, and A. Casadevall. 2006. The polysaccharide capsule of the pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans enlarges by distal growth and is rearranged during budding. Mol. Microbiol. 5967-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]